- Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Objective: Antibiotic resistance in Salmonella represents a significant global public health concern. Among various serovars, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is prevalent in multiple countries. This study aims to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the pattern of antibiotic resistance in S. Typhimurium isolates from diverse sources in Iran.

Methods: We conducted a comprehensive and systematic search for relevant articles until December 2023 in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and SID. The collected data were analyzed using Stata software version 17.

Results: Eighteen studies examined the pattern of antibiotic resistance in S. Typhimurium for various antibiotics in Iran. Piperacillin and tetracycline exhibited the highest resistance rates, at 79 and 60% respectively, while cefixime and ceftriaxone had the lowest resistance rates at 0%.

Conclusion: Our findings indicate a high level of antibiotic resistance among the studied antibiotics. This high level of antibiotic resistance raises concerns and underscores the necessity for monitoring the use of antibiotics. Moreover, resistance to these antibiotics was more prevalent in samples isolated from animals compared to other sources. This highlights the importance of animal screening to detect the presence of drug-resistant isolates, with the ultimate goal of reducing antibiotic resistance and preventing the transmission of resistant strains to humans.

Introduction

Salmonellosis is one of the most common food-borne diseases worldwide, causing severe and occasionally deadly infections in humans (1). Based on published data, over 2,500 serotypes of Salmonella have been recognized, with 1,500 serovars linked to human and animal diseases (2).

Salmonella serovars have the ability to infect a diverse array of domestic animals such as sheep, cattle, poultry, and pigs. Infected animals may exhibit varying symptoms, varying from mild gastroenteritis to severe infections that can be fatal (3). Painter et al. ~17.9% of foodborne illnesses are linked to poultry, with 19% of these poultry-related illnesses attributed to Salmonella enterica (3).

Non-typhoidal salmonellosis is an important enteric infection in humans, particularly in neonates and young children (4). The consumption of contaminated animal-derived foods such as beef, poultry, pork, and lamb is the major route of Salmonella transmission to humans (5).

Non-typhoidal Salmonella causes ~153 million cases of gastroenteritis and 57,000 deaths annually worldwide (6). Salmonella Typhimurium has been reported as one of the most widespread foodborne pathogens in many countries (7). This serovar is the most common in Europe and can be isolated from humans, pigs, and pork. In the United States, it is one of five serovars associated with human salmonellosis (7, 8).

One of the recent global public health concerns regarding salmonellosis is the emergence and spread of resistant Salmonella strains, including multiple drug-resistant (MDR) strains in both humans and animals (9).

Antibiotics are not commonly used to treat human salmonellosis, as the illness typically resolves in 5–7 days without treatment (10). However, in some cases, antibiotic therapy may be necessary (10). In these instances, appropriate antimicrobial therapy such as ciprofloxacin in adults and ceftriaxone in children can be used (4, 10). Nonetheless, treating these patients can sometimes be challenging due to antibiotic resistance of pathogen (11).

The use of antimicrobial agents in any environment creates pressures that favor the survival of antibiotic-resistant pathogens (12). The routine practice of administering antimicrobial agents to domestic livestock for disease prevention, treatment, and growth promotion is a significant factor in the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which are subsequently transmitted to humans through the food chain (13, 14). Most infections with antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella are acquired by eating contaminated foods of animal origin (15).

Therefore, this meta-analysis was conducted to investigate the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance of S. Typhimurium isolates in Iran. Additionally, this study provides a better understanding of antibiotic resistance in this bacterium, ultimately helping to choose the most optimal and effective treatment approach.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search in the PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Scientific Information Database (SID) databases up to December 2023 to identify potentially relevant studies. The search criteria used were (“Salmonella Typhimurium” OR “S. Typhimurium”) AND (Resistan* OR suscep*) AND (Iran) with their respective Mesh terms.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All original articles that reported the prevalence of antibiotic resistance among S. Typhimurium isolates in Iran were included. Articles were excluded if they were reviews, conference presentations, case reports, studies with unclear results, or written in languages other than English and Persian.

Data extraction

After consolidating the articles in the EndNote X20 Citation Manager Software, duplicate articles were removed before the review process. The citations were then uploaded to Rayyan, a citation classification application (16). Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts and removed irrelevant articles. The full texts of potentially relevant articles were collected and reviewed independently by two authors. Data from eligible studies, including the first author, publication year, source of samples, sample size (total isolates and number of resistances of S. Typhimurium for various antibiotics), were independently extracted by two researchers. Inconsistencies between the reviewers were resolved through discussion to reach a consensus.

Quality assessment of studies

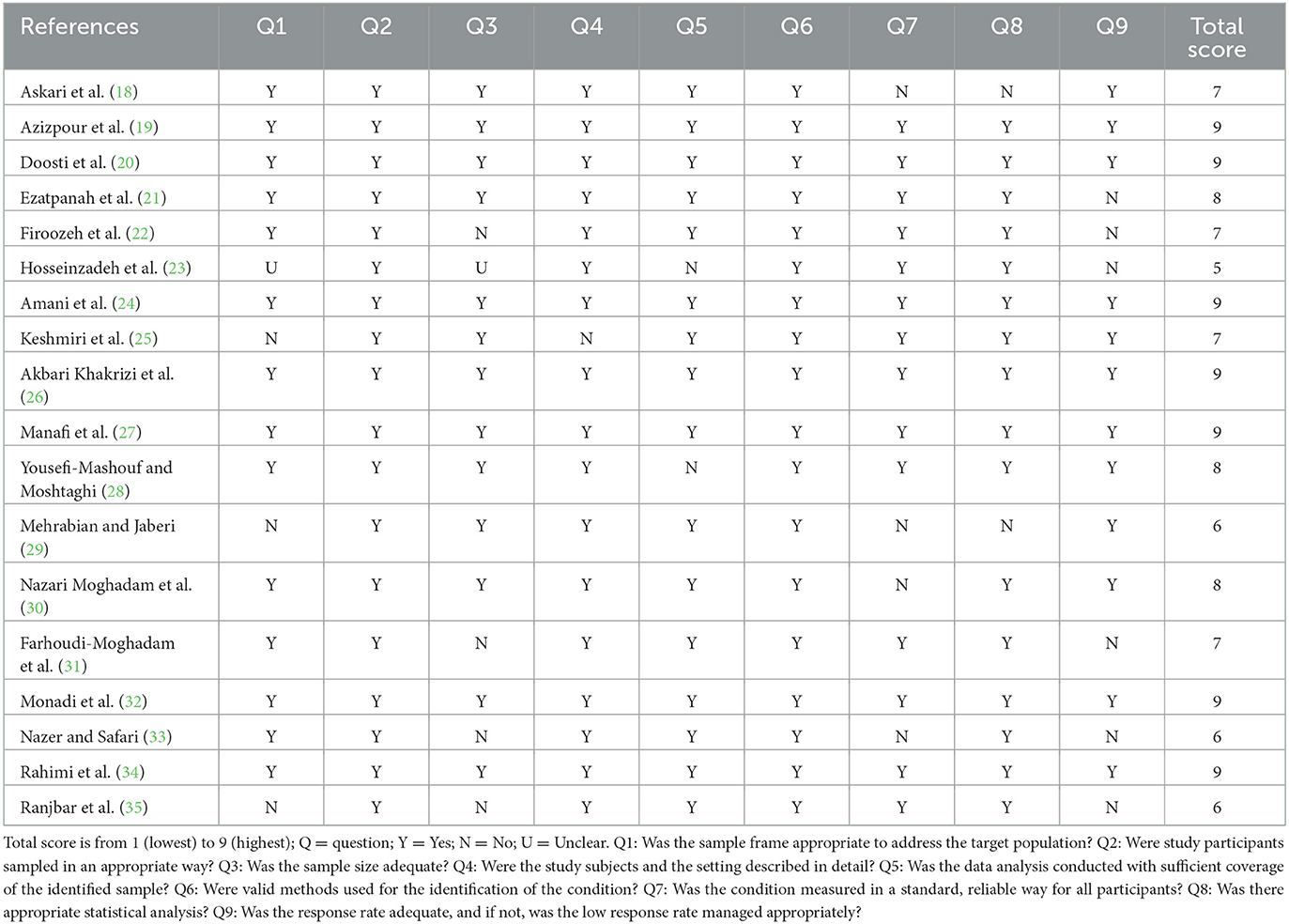

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist (17). Two reviewers independently evaluated and scored the quality of each article included in the review, resolving any disagreements through discussion.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis and generation of forest plots for this review were conducted using Stata 17 software. The I-squared index (I2) was used to assess the possibility of heterogeneity among studies, categorizing the degree of heterogeneity as low, moderate, or high based on I2-values (expressed as percentages around 25, 50, and 75, respectively). To evaluate publication bias, Egger and Begg tests were performed; a significance level of P < 0.05 indicated statistically significant publication bias. The pooled prevalence of S. Typhimurium resistance to the investigated antibiotics, along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), was calculated using forest plots in a random-effects model. Moreover, subgroup meta-analysis was conducted for the source of S. Typhimurium isolates for different antibiotics if a sufficient number of articles were available.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

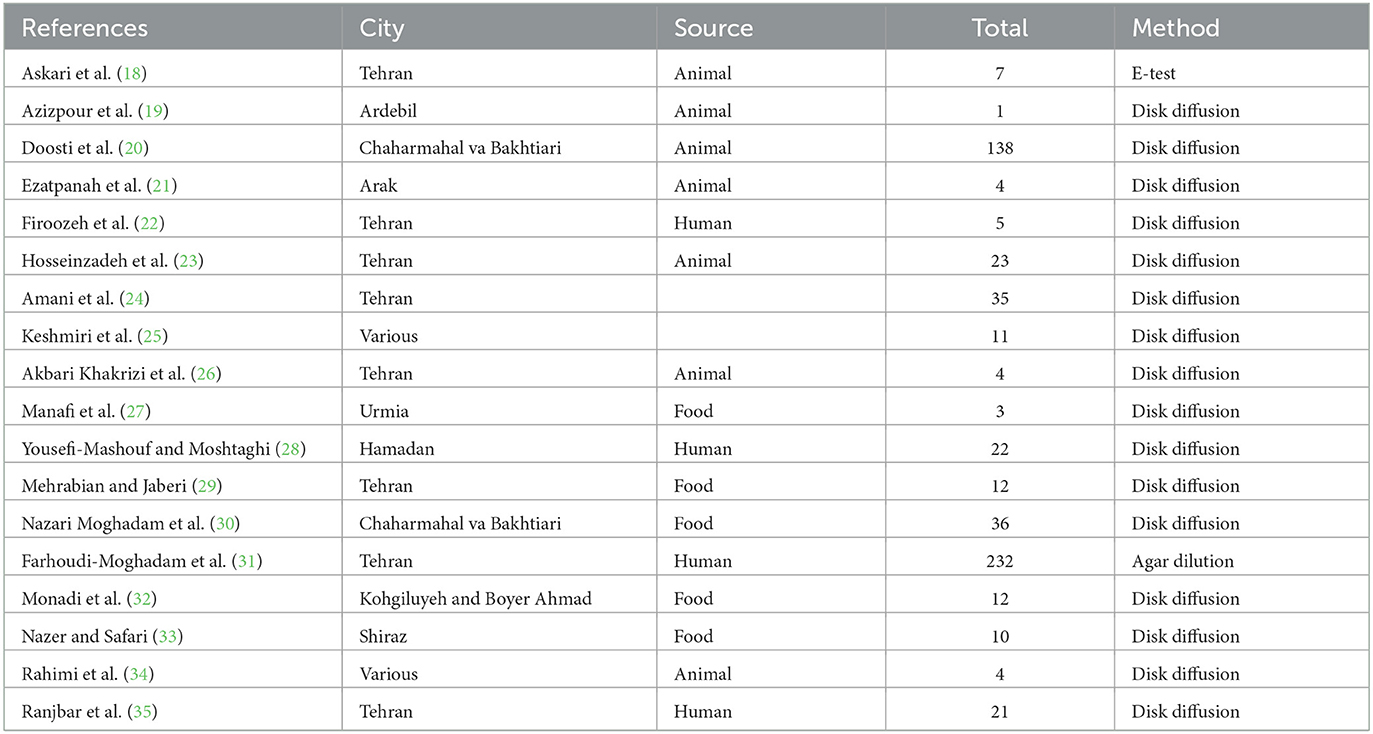

A total of 841 articles were obtained through a database search. After eliminating duplicates, 500 articles remained. Subsequently, 60 publications underwent full-text evaluation. As a result, 42 articles were excluded, and this study included 18 cross-sectional studies that examined the antibiotic resistance of S. Typhimurium (Figure 1). The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Additionally, Table 2 contains the results of the quality assessment.

Data analysis

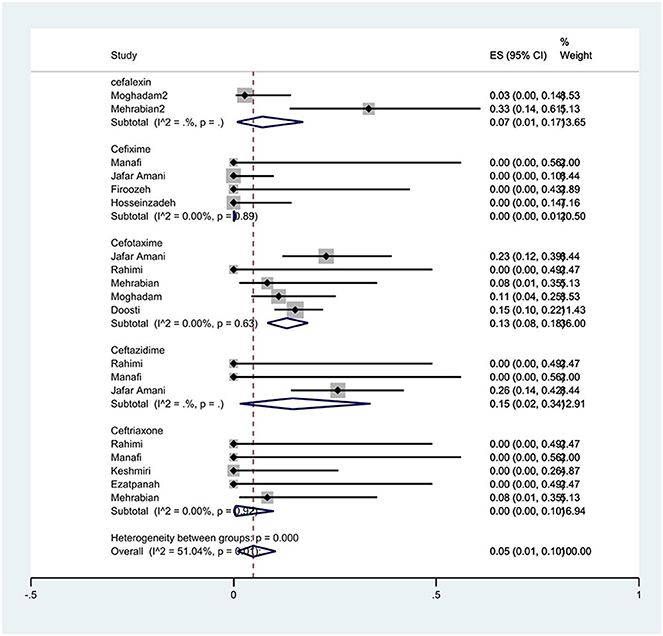

Prevalence of cephalosporin resistance

The susceptibility to cefalexin was determined in two studies. The prevalence of cefalexin resistance was 7% (95% CI: 1–17%). The susceptibility to cefixime was determined in four studies. The prevalence of cefixime resistance was 0% (95% CI: 0–1%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.89). The susceptibility to cefotaxime was determined in five studies. The prevalence of cefotaxime resistance was 13% (95% CI: 8–18%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.63). The susceptibility to ceftazidime was determined in three studies. The prevalence of ceftazidime resistance was 15% (95% CI: 2–34%). The susceptibility to ceftriaxone was determined in five studies. The prevalence of ceftriaxone resistance was 0% (95% CI: 0–10%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.93; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the prevalence of cephalosporin family resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran.

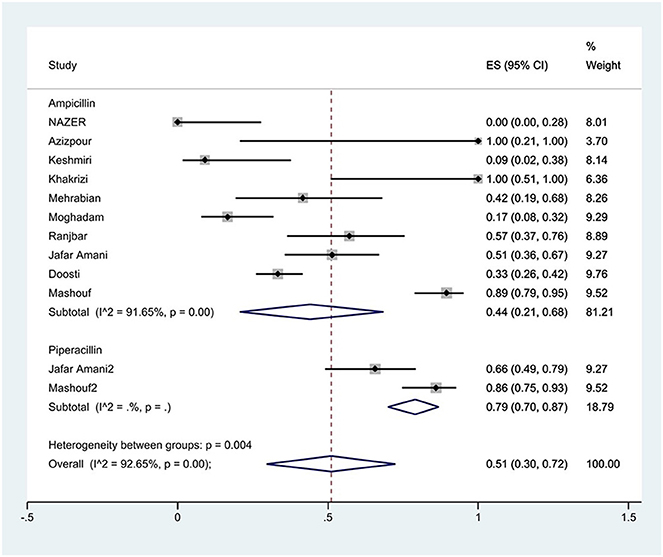

Prevalence of penicillin resistance

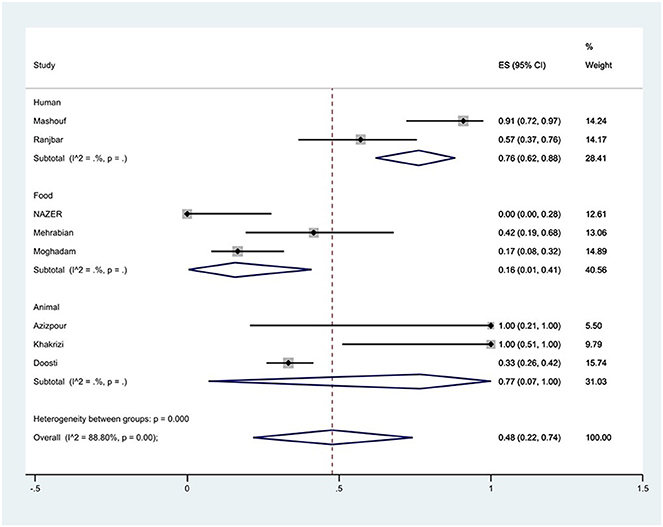

The susceptibility to piperacillin was determined in two studies. The prevalence of piperacillin resistance was 79% (95% CI: 70–87%). The susceptibility to ampicillin was determined in 10 studies. The prevalence of ampicillin resistance was 44% (95% CI: 21–68%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 91.65%, P < 0.01; Figure 3). Furthermore, subgroup meta-analysis of ampicillin resistance based on the source of S. Typhimurium isolation showed that the rate of ampicillin resistance in animal samples was 77% (95% CI: 7–100%), which was higher than in food and human sources (P < 0.01; Figure 4).

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the prevalence of penicillin family resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the prevalence of ampicillin resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran from different sources.

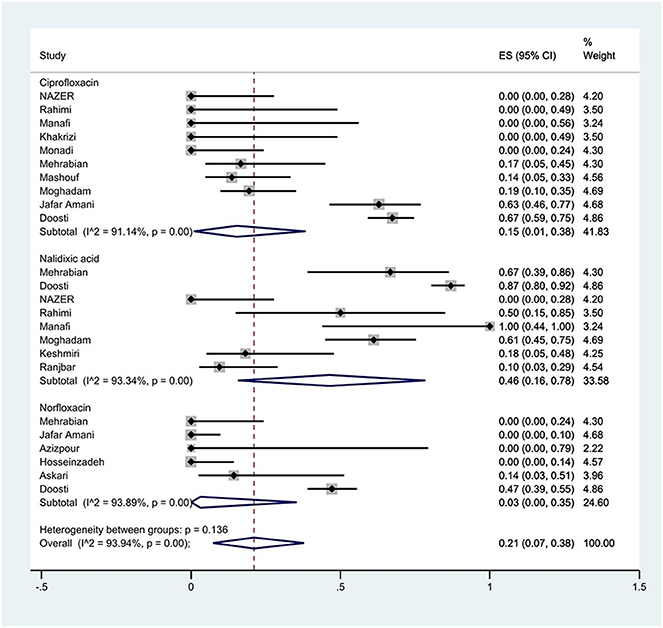

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones resistance

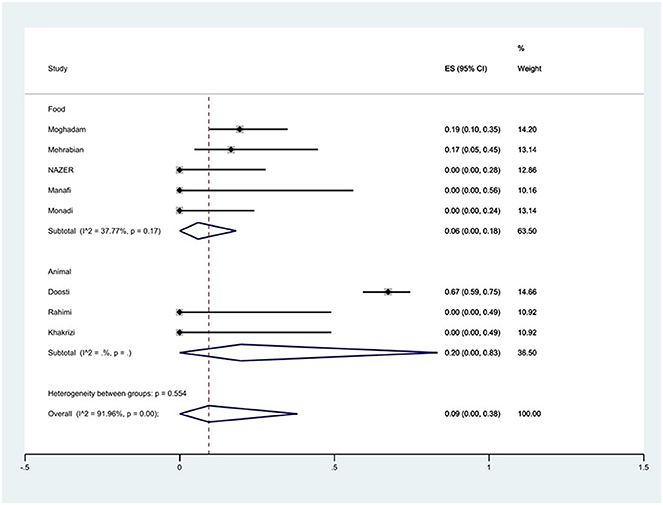

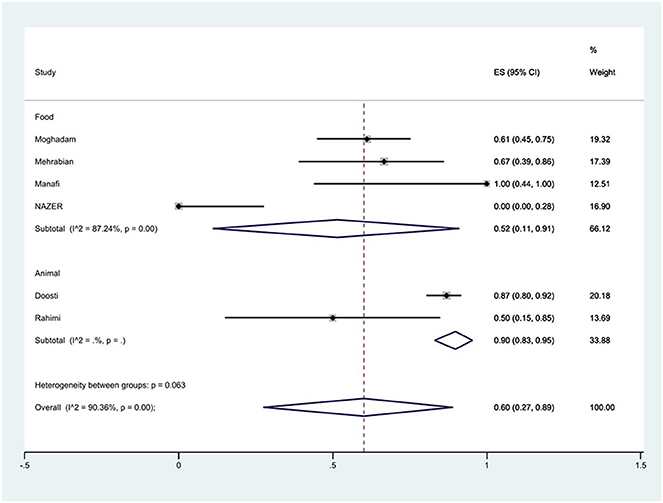

The susceptibility to norfloxacin was determined in six studies. The prevalence of norfloxacin resistance was 3% (95% CI: 0–35%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 93.89%, P < 0.01; Figure 5). The susceptibility to ciprofloxacin was determined in ten studies. The prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistance was 15% (95% CI: 1–38%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 91.14%, P < 0.01). Additionally, subgroup meta-analysis of ciprofloxacin resistance based on the source of S. Typhimurium isolation showed that the rate of ciprofloxacin resistance in animal samples was 20% (95% CI: 0–83%), which was higher than in food sources (P = 0.554; Figure 6). The susceptibility to nalidixic acid was determined in eight studies. The prevalence of nalidixic acid resistance was 46% (95% CI: 16–78%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 93.89%, P < 0.01). In addition, subgroup meta-analysis of nalidixic acid resistance based on the source of S. Typhimurium isolation showed that the rate of nalidixic acid resistance in animal samples was 90% (95% CI: 83–96%), which was higher than in food sources (P = 0.063; Figure 7).

Figure 5. Forest plot showing the prevalence of fluoroquinolones family resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran.

Figure 6. Forest plot showing the prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran from different sources.

Figure 7. Forest plot showing the prevalence of nalidixic acid resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran from different sources.

Prevalence of tetracycline resistance

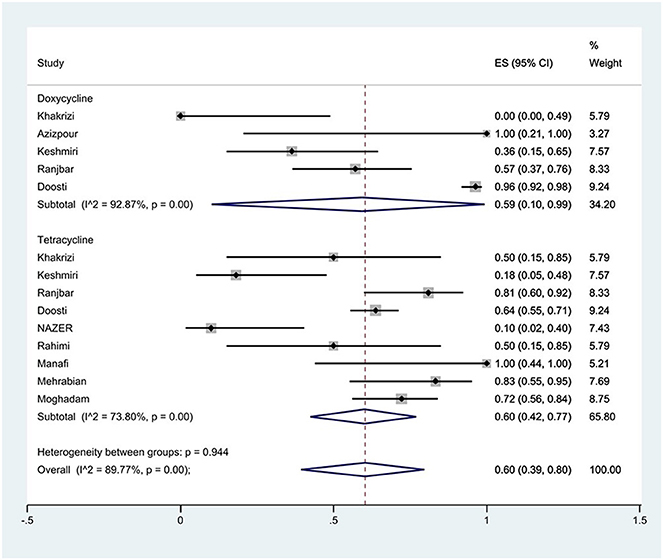

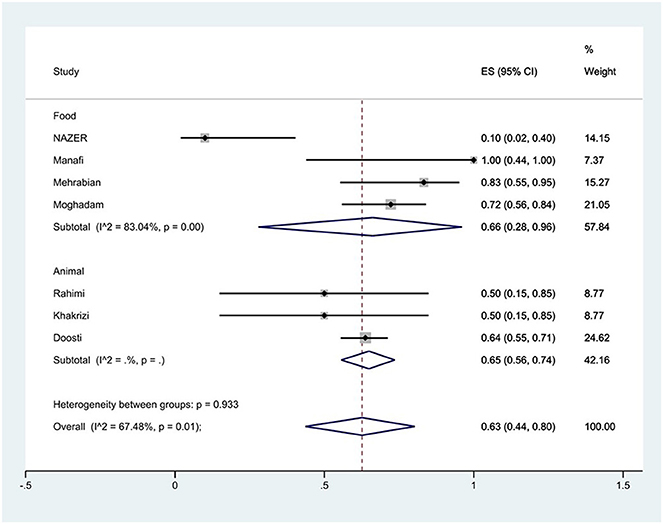

The susceptibility to doxycycline was determined in five studies. The prevalence of doxycycline resistance was 59% (95% CI: 10–99%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 92.87%, P < 0.01; Figure 8). The susceptibility to tetracycline was determined in nine studies. The prevalence of tetracycline resistance was 60% (95% CI: 42–77%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 73.80%, P < 0.01). Moreover, subgroup meta-analysis of tetracycline resistance based on the source of S. Typhimurium isolation showed that the rate of tetracycline resistance was similar in animal samples at 65% (95% CI: 56–74%) and food samples at 66% (95% CI: 28–96%; P = 0.933; Figure 9).

Figure 8. Forest plot showing the prevalence of tetracycline family resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran.

Figure 9. Forest plot showing the prevalence of tetracycline resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran from different sources.

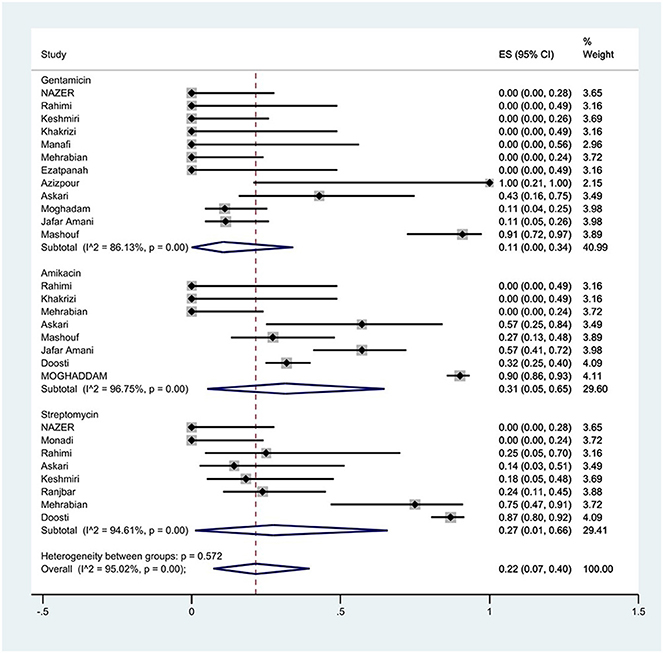

Prevalence of aminoglycoside resistance

The susceptibility to amikacin was determined in eight studies. The prevalence of amikacin resistance was 31% (95% CI: 5–65%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 96.75%, P < 0.01; Figure 10).

Figure 10. Forest plot showing the prevalence of aminoglycoside family resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran.

The susceptibility to gentamicin was determined in 12 studies. The prevalence of gentamicin resistance was 11% (95% CI: 0–34%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 86.13%, P < 0.01).

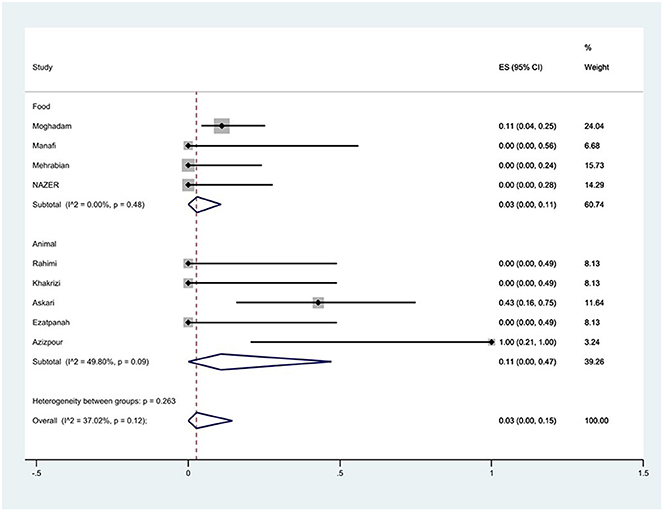

Furthermore, a subgroup meta-analysis of gentamicin resistance based on the source of S. Typhimurium isolation indicated that the rate of gentamicin resistance in animal samples was 11% (95% CI: 0–47%), which was higher than that in food sources (P = 0.263; Figure 11).

Figure 11. Forest plot showing the prevalence of gentamicin resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran from different sources.

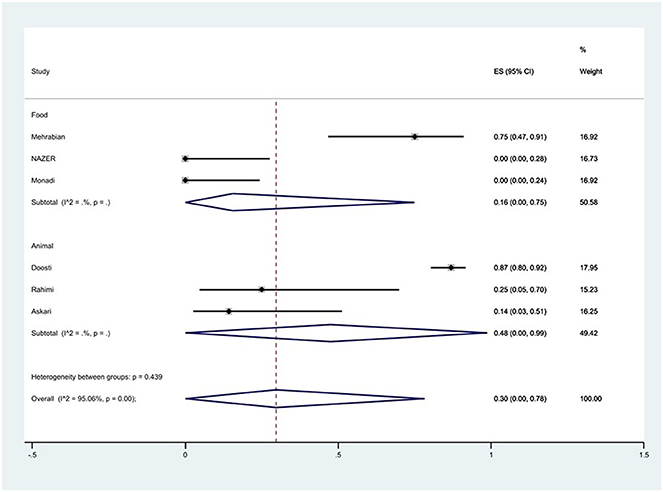

The susceptibility to streptomycin was determined in eight studies. The prevalence of streptomycin resistance was 27% (95% CI: 1–66%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 94.61%, P < 0.01).

Additionally, a subgroup meta-analysis of streptomycin resistance based on the source of S. Typhimurium isolation demonstrated that the rate of streptomycin resistance in animal samples was 48% (95% CI: 0–99%), which was higher than in food sources (P = 0.439; Figure 12).

Figure 12. Forest plot showing the prevalence of streptomycin resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran from different sources.

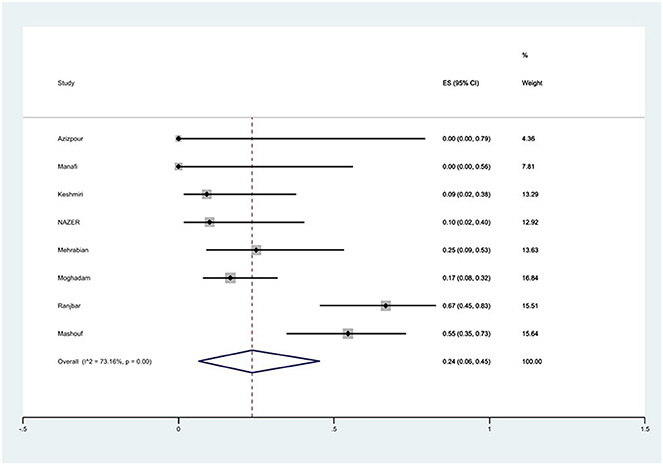

Prevalence of chloramphenicol resistance

The susceptibility to chloramphenicol was determined in eight studies. The prevalence of chloramphenicol resistance was 24% (95% CI: 6–45%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 73.16%, P < 0.01; Figure 13).

Figure 13. Forest plot showing the prevalence of chloramphenicol resistance of S. Typhimurium in Iran.

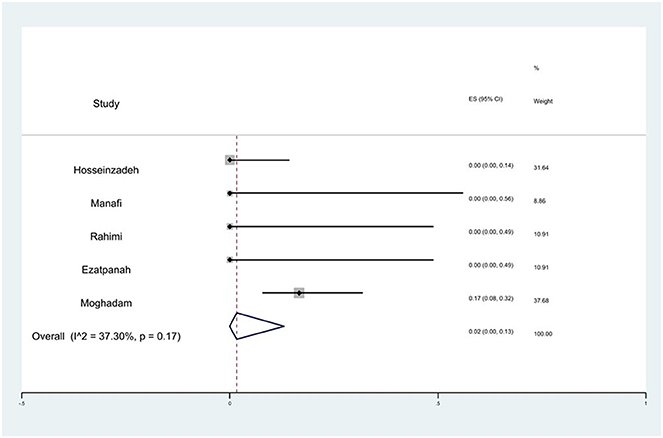

Prevalence of imipenem resistance

The susceptibility to imipenem was determined in five studies. The prevalence of imipenem resistance was 2% (95% CI: 0–13%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 37.30%, P = 0.17; Figure 14).

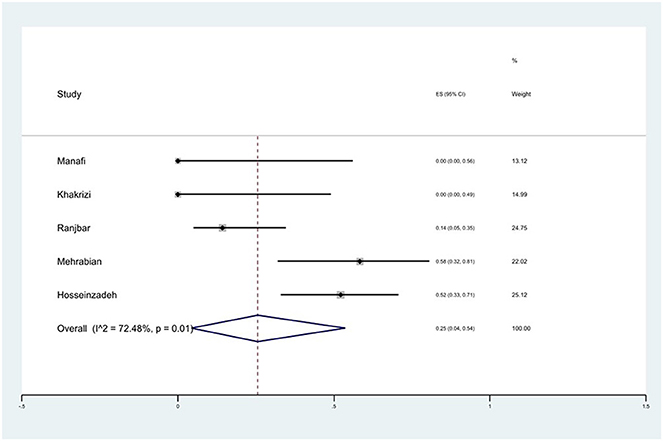

Prevalence of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT) resistance

The susceptibility to SXT was determined in five studies. The prevalence of SXT resistance was 25% (95% CI: 4–54%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 72.48%, P = 0.01; Figure 15).

Discussion

Recently, there have been reports of an increase in the prevalence of Salmonella strains that are resistant to antimicrobial agents (36). This surge in prevalence poses a significant public health concern (27). Therefore, acquiring epidemiological information on drug resistance can assist physicians and healthcare professionals in selecting appropriate antimicrobials and averting treatment failure. Given that serovar Typhimurium is among the prevalent Salmonella serovars in numerous countries, we utilized a meta-analysis approach to gather pertinent published data on the antibiotic resistance patterns of S. Typhimurium isolates in Iran.

Our results showed that piperacillin, tetracycline, doxycycline, nalidixic acid, and ampicillin had the highest resistance rates in S. Typhimurium isolates in Iran, with 79, 60, 59, 46, and 44%, respectively. The high rate of antibiotic resistance for these antibiotics may be the result of improper use or misuse of these antibiotics in human clinical treatment and animal food production (37). Improper use of antibiotics may lead to exposure of bacteria to antibiotics, which increases the possibility of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (12). In general, the increase in the antibiotic resistance levels of S. Typhimurium isolates may contribute to the further spread of the serovar (38), which highlights the importance of establishing targeted surveillance throughout the country to obtain more information about the antibiotic resistance of this bacterium in order to take appropriate measures to reduce its prevalence in different sources.

While cefixime, ceftriaxone, imipenem, and norfloxacin antibiotics were the most effective against S. Typhimurium with 0, 0, 2, and 3% resistance, respectively. Therefore, these drugs could be applied as treatment options against illness caused by this microorganism.

In a study conducted by Tai et al. on Salmonella samples isolated from raw meat in Vietnam, the highest antibiotic resistance observed in S. Typhimurium was against tetracycline (86.4%), followed by streptomycin (81.8%) and nalidixic acid (77.3%) (39). In a study by Zeng et al., S. Typhimurium isolated from human clinical samples in China showed the highest resistance to ampicillin (81.6%), ciprofloxacin (81.6%), and tetracycline (82.4%) (40). These findings demonstrate the variation in S. Typhimurium resistance across different countries, highlighting the importance of resistance screening in each nation.

In the meta-analysis, Tadesse et al. indicated that certain strains of Salmonella found in farm animals in Ethiopia exhibit resistance to drugs commonly used for treating human salmonellosis, posing a potential risk of human exposure to drug-resistant Salmonella (41). Thung et al. conducted a study in Malaysia to investigate the presence of Salmonella, specifically S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium, in uncooked chicken meat (42). Their analysis of 120 chicken meat samples revealed that the prevalence of Salmonella and S. Typhimurium was 20.80 and 2.50%, respectively. Notably, all isolates exhibited resistance to erythromycin, penicillin, and vancomycin, with relatively lower resistance rates observed for nalidixic acid (9.09%) and streptomycin (9.09%). The study findings underscore the potential for chicken meat to serve as a reservoir of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella. Meanwhile, Talukder et al. conducted a meta-analysis focusing on the prevalence and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Salmonella strains isolated from human, animal, and environmental samples in South Asia (43). Their analysis revealed a lower prevalence of salmonella in humans (5.81%) compared to animals (22.66%) and the environment (27.81%). Salmonella strains displayed high resistance levels to nalidixic acid (74.25%) and tetracycline (37.64%), whereas lower resistance rates were observed for ceftriaxone (1.07%) and cefixime (1.24%). We categorized the origins of isolates into human, animal (such as poultry, livestock, and dogs), and food samples (including processed foods, meat, and eggs) for ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, tetracycline, gentamicin, and streptomycin. In all these antibiotics, the level of resistance in the samples isolated from animals was higher than in other sources. This emphasizes the importance of animal screening to check for the presence of drug-resistant isolates and the significance of controlling antibiotic consumption in animals to reduce antibiotic resistance and prevent the transmission of resistant strains to humans.

In general, third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones are considered the most effective and commonly used antibiotics for treating S. Typhimurium infections (44). The study findings revealed that among third-generation cephalosporins, cefixime, and ceftriaxone exhibited the lowest levels of resistance, making them favorable treatment options for infections caused by this bacterium. Additionally, within the fluoroquinolone class, norfloxacin demonstrated the least resistance compared to other antibiotics in this category, suggesting its potential as a treatment of choice for this bacterium in Iran. Furthermore, the resistance rate to imipenem in this bacterium was found to be 2%, indicating the potential usefulness of this antibiotic in managing MDR bacteria.

One limitation of the present study was the relatively high heterogeneity between studies. We employed subgroup analysis to identify sources of heterogeneity and mitigate its impact on the results.

Conclusion

A high level of resistance to most of the studied antibiotics was observed. The highest antibiotic resistance was observed against piperacillin, tetracycline, doxycycline, nalidixic acid, and ampicillin, while cefixime, ceftriaxone, imipenem, and norfloxacin were the most effective treatment options for S. Typhimurium. Management and monitoring of antibiotic use, as well as screening to check the presence of drug-resistant isolates in animals, are recommended.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SR: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. FM: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was financially supported by a research grant (No. 28078) in Iran University of Medical Sciences (Tehran, Iran).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Pal M, Merera O, Abera F, Rahman M, Hazarika R. Salmonellosis: a major foodborne disease of global significance. Beverage Food World. (2015) 42:21–4.

2. Branchu P, Bawn M, Kingsley RA. Genome variation and molecular epidemiology of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium pathovariants. Infect Immun. (2018) 86:10–128. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00079-18

3. Painter JA, Hoekstra RM, Ayers T, Tauxe RV, Braden CR, Angulo FJ, et al. Attribution of foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths to food commodities by using outbreak data, United States, 1998-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. (2013) 19:407. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.111866

4. Wen SC, Best E, Nourse C. Non-typhoidal salmonella infections in children: review of literature and recommendations for management. J Paediatr Child Health. (2017) 53:936–41. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13585

5. Dawoud TM, Shi Z, Kwon YM, Ricke SC. Overview of salmonellosis and food-borne salmonella: historical and current perspectives. Producing Safe Eggs. (2017) 7:113–38. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802582-6.00007-0

6. Fazza O, Hmyene A, Ennassiri H, Essalhi A, Ennachachibi MF. Non typhoidal salmonella in food products. Moroccan J Agri Sci. (2021) 2:154–9.

7. Ferrari RG, Rosario DK, Cunha-Neto A, Mano SB, Figueiredo EE, Conte-Junior CA. Worldwide epidemiology of salmonella serovars in animal-based foods: a meta-analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2019) 85:e00591–19. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00591-19

8. Sun H, Wan Y, Du P, Bai L. The epidemiology of monophasic Salmonella typhimurium. Foodborne Pathog Dis. (2020) 17:87–97. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2019.2676

9. Eng SK, Pusparajah P, Ab Mutalib NS, Ser HL, Chan KG, Lee LH. Salmonella: a review on pathogenesis, epidemiology and antibiotic resistance. Front Life Sci. (2015) 8:284–93. doi: 10.1080/21553769.2015.1051243

10. Asperilla MO, Smego RA, Scott LK. Quinolone antibiotics in the treatment of salmonella infections. Rev Infect Dis. (1990) 12:873–89. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.5.873

11. Chang YJ, Chen MC, Feng Y, Su LH, Li HC, Yang HP, et al. Highly antimicrobial-resistant nontyphoidal salmonella from retail meats and clinical impact in children, Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. (2020) 61:432–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2020.03.017

12. Serwecińska L. Antimicrobials and antibiotic-resistant bacteria: a risk to the environment and to public health. Water. (2020) 12:3313. doi: 10.3390/w12123313

13. Aarestrup FM. The livestock reservoir for antimicrobial resistance: a personal view on changing patterns of risks, effects of interventions and the way forward. Philos Trans Royal Soc B. (2015) 370:20140085. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0085

14. Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DJ. Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. (2018) 42:fux053. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux053

15. Hald T, Lo Fo Wong DM, Aarestrup FM. The attribution of human infections with antimicrobial resistant salmonella bacteria in Denmark to sources of animal origin. Foodborne Pathog Dis. (2007) 4:313–26. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2007.0002

16. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

17. Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool. JBI Evid Synth. (2020) 18:2127–33. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099

18. نادر ع, سیامک مشهدی ر, کیومرث ا. شناسایی، سروتایپینگ و تعیین مقاومت آنتی بیوتیکی جدایه های سالمونلا به دست آمده از سگ های بدون صاحب در تهران. نشریه میکروبیولوژی دامپزشکی (1400) 16:43–52.

19. Azizpour A. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of salmonella serotypes in chicken meat of Ardabil, Northwestern Iran. Iran J Med Microbiol. (2021) 15:232–46. doi: 10.30699/ijmm.15.2.232

20. Doosti A, Mahmoudi E, Jami M-S, Mokhtari-Farsani A. Prevalence of Aada1, Aada2, Aadb, Stra and Strb genes and their associations with multidrug resistance phenotype in Salmonella typhimurium isolated from poultry carcasses. Thai J Vet Med. (2016) 46:691–7. doi: 10.56808/2985-1130.2790

21. Ezatpanah E, Bidhendi SM, Khaki P, Ghaderi R, Jasbi ES, Far SM. Isolation, serotyping and antibiotic-resistance pattern of isolated salmonella from chicken of arak. Iran Vet J. (2013) 9:88–96.

22. Firoozeh F, Shahcheraghi F, Zahraei Salehi T, Karimi V, Aslani MM. Antimicrobial resistance profile and presence of class I integrongs among Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from human clinical specimens in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Microbiol. (2011) 3:112–7.

23. Hosseinzadeh S, Saei HD, Ahmadi M, Salehi TZ. Antimicrobial effect of licochalcone a and epigallocatechin-3-gallate against Salmonella typhimurium isolated from poultry flocks. Iran J Microbiol. (2018) 10:51–8.

24. Amani JA, Barjini KM, Moghaddam M, Asadi A. In vitro synergistic effect of the Cm11 antimicrobial peptide in combination with common antibiotics against clinical isolates of six species of multidrug-resistant pathogenic bacteria. Protein Peptide Lett. (2015) 22:940–51. doi: 10.2174/0929866522666150728115439

25. Keshmiri MA, Nemati A, Askari Badouei M, Ashrafi Tamai I, Zahraei Salehi T. Clonal relatedness and antimicrobial susceptibility of salmonella serovars isolated from humans and domestic animals in Iran: a one health perspective. Iran J Vet Res. (2022) 23:104–10. doi: 10.22099/IJVR.2022.40594.5881

26. Akbari Khakrizi A, Yahyaraeyat R, Ashrafi Tamai I, Beikzadeh B, Zahraei Salehi T. Prevalence assessment of salmonella serovars in apparently healthy pet dogs in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Vet Sci Technol. (2022) 14:11–8.

27. Manafi L, Aliakbarlu J, Dastmalchi Saei H. Antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation ability of salmonella serotypes isolated from beef, mutton, and meat contact surfaces at retail. J Food Sci. (2020) 85:2516–22. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15335

28. Yousefi-Mashouf R, Moshtaghi A. Frequency of typhoidal and non-typhoidal salmonella species and detection of their drugs resistance patterns. J Res Health Sci. (2007) 7:49–56.

29. Mehrabian S, Jaberi E. Isolasion, identification and antimicrobial resistance patterns of salmonella from meat products in Tehran. Pak J Biol Sci. (2007) 10:122–6. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.122.126

30. Nazari Moghadam M, Rahimi E, Shakerian A, Momtaz H. Prevalence of Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella enteritidis isolated from poultry meat: virulence and antimicrobial-resistant genes. BMC Microbiol. (2023) 23:168. doi: 10.1186/s12866-023-02908-8

31. Farhoudi-Moghaddam AA, Katouli M, Jafari A, Bahavar MA, Parsi M, Malekzadeh F. Antimicrobial drug resistance and resistance factor transfer among clinical isolates of salmonellae in Iran. Scand J Infect Dis. (1990) 22:197–203. doi: 10.3109/00365549009037902

32. Monadi M, Kargar M, Naghiha A, Najafi A, Mohammadi R. Molecular detection of salmonella serovar isolated from eggs. Med Lab J. (2015) 9:17–24.

33. Nazer A, Safari G. Bacterial flora from dead-in-shell chicken embryos and their drug resistance in Fars Province of Iran. Ind J Anim Sci. (1994) 1994:64.

34. Rahimi E, Shakerian A, Falavarjani AG. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of salmonella isolated from fish, shrimp, lobster, and crab in Iran. Comp Clin Path. (2013) 22:59–62. doi: 10.1007/s00580-011-1368-3

35. Ranjbar R, Elhaghi P, Shokoohizadeh L. Multilocus sequence typing of the clinical isolates of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in Tehran Hospitals. Iran J Med Sci. (2017) 42:443.

36. Medalla F, Gu W, Friedman CR, Judd M, Folster J, Griffin PM, et al. Increased incidence of antimicrobial-resistant nontyphoidal salmonella infections, United States, 2004-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:1662. doi: 10.3201/eid2706.204486

37. Singer RS, Finch R, Wegener HC, Bywater R, Walters J, Lipsitch M. Antibiotic resistance-the interplay between antibiotic use in animals and human beings. Lancet Infect Dis. (2003) 3:47–51. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00490-0

38. Wang J, Li Y, Xu X, Liang B, Wu F, Yang X, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in Shanghai, China. Front Microbiol. (2017) 8:510. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00510

39. Thai TH, Hirai T, Lan NT, Yamaguchi R. Antibiotic resistance profiles of salmonella serovars isolated from retail pork and chicken meat in North Vietnam. Int J Food Microbiol. (2012) 156:147–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.03.016

40. Zeng X, Lv S, Qu C, Lan L, Tan D, Li X, et al. Serotypes, antibiotic resistance, and molecular characterization of non-typhoidal salmonella isolated from diarrheic patients in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China, 2014-2017. Food Control. (2021) 120:107478. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107478

41. Tadesse G. A meta-analysis of the proportion of animal salmonella isolates resistant to drugs used against human salmonellosis in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. (2015) 15:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0835-x

42. Thung T, Mahyudin NA, Basri DF, Radzi CWM, Nakaguchi Y, Nishibuchi M, et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella enteritidis and Salmonella typhimurium in raw chicken meat at retail markets in Malaysia. Poult Sci. (2016) 95:1888–93. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew144

43. Talukder H, Roky SA, Debnath K, Sharma B, Ahmed J, Roy S. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profile of salmonella isolated from human, animal and environment samples in South Asia: a 10-year meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Glob Health. (2023) 13:637–52. doi: 10.1007/s44197-023-00160-x

Keywords: Salmonella Typhimurium, antibiotic resistance, tetracycline, cefixime, meta-analysis

Citation: Narimisa N, Razavi S and Masjedian Jazi F (2024) Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium isolates originating from Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 11:1388790. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1388790

Received: 22 February 2024; Accepted: 13 May 2024;

Published: 27 May 2024.

Edited by:

Albert Van Geelen, USDA-APHIS Center for Veterinary Biologics, United StatesReviewed by:

Mehmet Cemal Adiguzel, Atatürk University, TürkiyeDalia Hamza, Cairo University, Egypt

Copyright © 2024 Narimisa, Razavi and Masjedian Jazi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Faramarz Masjedian Jazi, bWFzamVkaWFuLmZAaXVtcy5hYy5pcg==

Negar Narimisa

Negar Narimisa Shabnam Razavi

Shabnam Razavi