- 1Department of Population Medicine, The University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Psychology, The University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

- 3Centre for Research in Occupational Safety and Health, Laurentian University, Sudbury, ON, Canada

- 4Department of Clinical Studies, The University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

- 5Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, The University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Higher psychosocial work demands in veterinary and academic professions are associated with decreased occupational, physical, and mental well-being. COVID-19 introduced far-reaching challenges that may have increased the psychosocial work demands for these populations, thereby impacting individual- and institutional-level well-being. Our objective was to investigate the psychosocial work demands, health and well-being, and perceived needs of faculty, staff, residents and interns at the Ontario Veterinary College, in Ontario, Canada, during COVID-19. A total of 157 respondents completed a questionnaire between November 2020 and January 2021, that included the Third Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ-III) and open-text questions on perceived needs for well-being. Results showed that COPSOQ-III dimensions of quantitative demands, recognition, sense of community, burnout, stress, and depressive symptoms, were significantly worse in our study population than the Canadian norm. Quantitative and emotional demands, health and well-being (including depressive symptoms, stress, cognitive stress, somatic stress, and burnout), and work-life conflict were also reported to have worsened since the COVID-19 restrictions for most respondents. Females and caregivers had higher odds of experiencing increased work demands, and decreased health and well-being, compared to males and non-caregivers. However, male caregivers experienced worsened supervisor relations, compared to female caregivers. Social capital also worsened for clinical and part-time employees, compared to full-time and non-clinical employees. Respondents identified increased workload support, community-building, recognition of employees' capacities and personal needs, flexible work schedules, and consistent communication, as strategies to increase well-being during COVID-19 and generally. Overall, our findings suggest that COVID-19 has increased occupational demands, work-life conflicts, and decreased well-being in veterinary academia. Institutional-level interventions are discussed and recommended to aid individual and institutional well-being.

Introduction

Mental health is an area of concern in both the veterinary profession and in veterinary academia. Literature from the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), and Australia report that veterinarians experience higher levels of anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts, burnout, and lower levels of positive mental well-being, than the general population (1–5). Recent studies have contributed to a limited body of knowledge on the mental well-being of veterinarians in Canada (6) and Ontario (7). These studies yielded similar findings to their international counterparts, reporting poorer mental health and lower resilience in veterinarians than reference populations (6, 7). Comparably, mental health concerns exist in University academic institutions. Clinical and non-clinical staff, faculty, and employees in academic medical institutions also report high levels of burnout, stress, and general psychological morbidity (8–13). Studies of the mental health of veterinarians in academia are limited. However, a study of 785 Finnish veterinarians observed that those involved in education and research reported the highest levels of stress (14), and another study of 2,004 Australian veterinarians reported that those in salaried positions (i.e., research, teaching, industry and government) experienced the highest levels of depression (2).

A presumed mechanism underlying psychological morbidity in veterinarians was first proposed by Bartram et al. (1, 15), who then linked psychosocial work demands to the higher risk of suicide observed in veterinarians in the UK (5). Psychosocial work demands can be defined as interactions between work environment (i.e., social interactions), job content, organizational conditions (i.e., workplace culture), and an employee's capacity to manage these occupational factors, which can influence health, work performance, and job satisfaction (16). The occupational demands most associated with elevated stress in the Canadian veterinary population are reported to include workload and client-related issues, such as client complaints (17). Occupational stressors such as relationships with clients, euthanasia, working hours, and excessive workload, have been reported elsewhere (2, 5–7, 14, 15, 18–20).

The prevalence of work-related stressors in academia is also elevated. Increased pressure to secure external funding, diminishing resources, excessive administrative work and teaching loads, and unsatisfactory recognition and reward from administration are reported as prevalent concerns amongst non-medical academic employees (21, 22). Karasek (23) theorizes that the combination of low decision latitude (defined as an individual's control over their occupational tasks and/or work day), low social support, and high job demands is associated with greater mental and physical illnesses, including depression (24, 25), sleep disturbances (26), and cardiovascular disease (27). Given that this combination of workplace factors is observed in veterinary (1) and academic workplaces (21), gaining deeper insight into how psychosocial demands differ across clinical and non-clinical veterinarians, and research and teaching-based faculty in veterinary academia, is important to mitigate similar downstream effects.

The impact of the novel Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the veterinary profession is also important to consider as it has been sudden and far-reaching. Veterinarians in clinical practice have been challenged to make great modifications to help ensure patient and client safety while providing veterinary care (20). Clinical veterinary practices initially faced revenue declines associated with forced cancellation of appointments (20), followed by significant increases in work hours and weekend appointments, unpredictable schedule changes, and longer work-days to accommodate higher client-loads (28). Organizationally, economic shutdowns and new workplace policies may have accelerated infrastructure changes in academia that impact working hours, work-life balance, access to professional and personal support, and work settings, as observed with work-from-home measures (29, 30). Professionals in medical academia have also needed to adjust quickly, including canceling or restructuring research, pivoting to online teaching, and modifying clinical practice to adhere to public health guidelines while still fulfilling clinical teaching commitments and students' learning needs (31, 32). To our knowledge, no published research to date has assessed the psychosocial work demands placed on veterinary academics in both clinical and non-clinical work settings during the COVID-19 restrictions. Moreover, research on psychosocial workplace demands in the veterinarian profession has been mainly conducted outside of Canada (1, 2, 14, 19). As such, the unknown and likely widespread impacts of COVID-19 challenges in veterinary academia underscore the need for this research.

The objective of this study was to conduct a comprehensive investigation of the psychosocial work demands of employees at the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) during COVID-19, including: workload and work pace; social relations with supervisors and colleagues; job contents including trust, recognition, and work-life conflict; and general health and well-being. Additionally, our goal was to explore the perceived needs of this population during COVID-19 to inform well-being programming at the OVC, and potentially, similar medical institutions.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study using an online questionnaire was administered via Qualtrics (33) from November 10, 2020, to January 10, 2021. Survey email invitations were sent to the approximately 620 staff, faculty, interns, and residents at the OVC via OVC listservs. A reminder email was sent ~1 month after the initial distribution of the survey. A short description of the study and a link to access the consent letter and online questionnaire was included in all electronic distributions. An announcement of the study was also posted on the OVC electronic Bulletin.

The OVC consists of four academic units (Departments of Biomedical Sciences, Clinical Studies, Pathobiology, and Population Medicine), one academic veterinary Health Sciences Centre that provides specialty care for large and small animals as well as primary care to the community, and a central administrative services department. Across these units, the OVC employs both clinical roles (i.e., veterinarians, interns, residents, faculty, registered veterinary technicians, animal care attendants, veterinary staff, agricultural assistants), and non-clinical roles (i.e., faculty, technical staff, professional staff, administrative staff). Overall, there are ~120 faculty, 200 staff in the academic and administrative departments, and 300 staff in the Health Sciences Centre.

Eligible participants were faculty members (including adjunct faculty and sessional lecturers), staff (including administrative, professional, clinical, technical, and post-doctoral fellows), and clinical residents and interns at the OVC at the time of survey. Other inclusion criteria included being 18 years of age or older and able to read and write in English. Those who had not worked during the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., due to leave of absence, parental leave), were not eligible for inclusion. The study methodology was approved by the University of Guelph Research Ethics Board (20-08-016). Data were collected anonymously, and informed written consent was obtained before starting the questionnaire.

Questionnaire

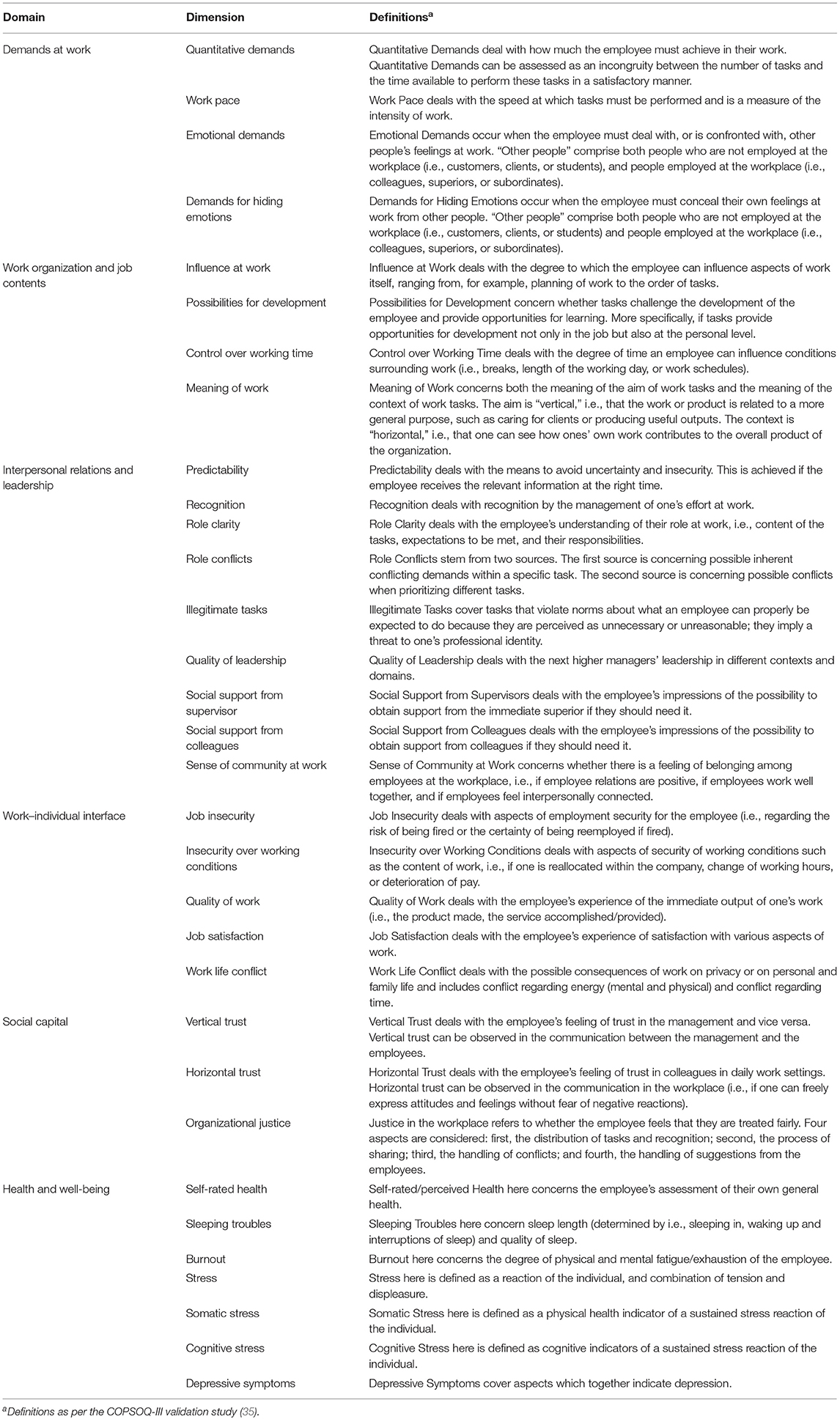

The questionnaire included items from the Third Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ-III) (34) to assess workplace psychosocial dimensions and six domains of: Demands at Work, Work Organization and Job Contents, Interpersonal Relations and Leadership, Work–Individual Interface, Social Capital, and Health and Well-being (35). Additional questions pertaining to respondent demographics, perceived changes in workplace stressors since COVID-19, and open-text questions on respondents' workplace experiences and perceived needs for well-being programming were also included.

The COPSOQ-III is an internationally validated and reliable instrument to measure psychosocial workplace factors across employee populations, workplaces, and industries (35). The COPSOQ-III facilitates a complex analysis of how work demands and psychosocial factors jointly present and impact well-being (36). The present study included 85 questions from the international middle and selected long versions of the COPSOQ-III, previously validated in the Canadian population and workforce (36). Through validated COPSOQ-III scales, 32 psychosocial dimensions were assessed across six broader psychosocial domains to assess psychosocial workplace factors, as well as health and well-being (Table 1).

For each of the COPSOQ-III dimensions, excluding self-rated health, respondents were asked whether there was a change in their answer since COVID-19 restrictions [i.e., the same since COVID-19, better now compared to before COVID-19 restrictions (i.e., the situation improved favorably), worse now compared to before COVID-19 restrictions (i.e., the situation worsened/became more unfavorable)]. For each COPSOQ-III dimension, Likert Scale–type items were measured and scaled to the interval of 0–100, as per scale instructions (35).

Demographic questions included respondent characteristics of age and gender (asked in open-text format), as well as questions on the following: current employment position at the OVC [i.e., faculty (veterinarian), faculty (non-veterinarian), registered veterinary technician (RVT), etc.]; clinical (i.e., >50% of the time is spent on clinical tasks) or non-clinical veterinary position (yes/no); employment status (full-time or part-time); weekly working hours (ranging across 10-h subscales from <24 h per week to >60 h per week); and the presence of dependents at home (yes/no; and where yes, the number of dependents per age category).

Open-text questions pertained to: the most stressful aspects of a respondent's work during the COVID-19 restrictions; what was/is helpful in the workplace during the COVID-19 restrictions; and what would help increase well-being at the OVC in general and during the COVID-19 restrictions.

Qualitative Analysis

Common themes were identified from open-text questions based on a thematic analysis (37) of respondents' written responses. An iterative coding process was performed, as recommended for rich and reliable data (38). The six phases of thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (37) were applied as a structured approach to developing codes and themes. In the first phase, the primary researcher (herein referred to as the “coder”) read the dataset twice for familiarization with the data. Next, the coder employed a systematic approach to construct and label codes in an inductive manner for the entirety of the data set. Here, meaningful aspects of the data and repeating patterns were identified with codes. The coder then analyzed all codes for horizontal and vertical relationships, and clustered related codes together into developing themes and subthemes, when applicable. Codes with similar or analogous content were grouped together to form the broader themes identified, and iteratively reviewed to ensure their applicability to the broader theme. To ensure reliable interpretation of the original data, the coder revised the themes and codes in relation to the entirety of the data set and coded data. Any related or overlapping themes and sub-themes were combined, and any themes, subthemes, or codes that were of low relevance to the study objectives were not retained. Through this method, key and actionable areas for well-being were identified within the entirety of the data set.

Statistical Analyses

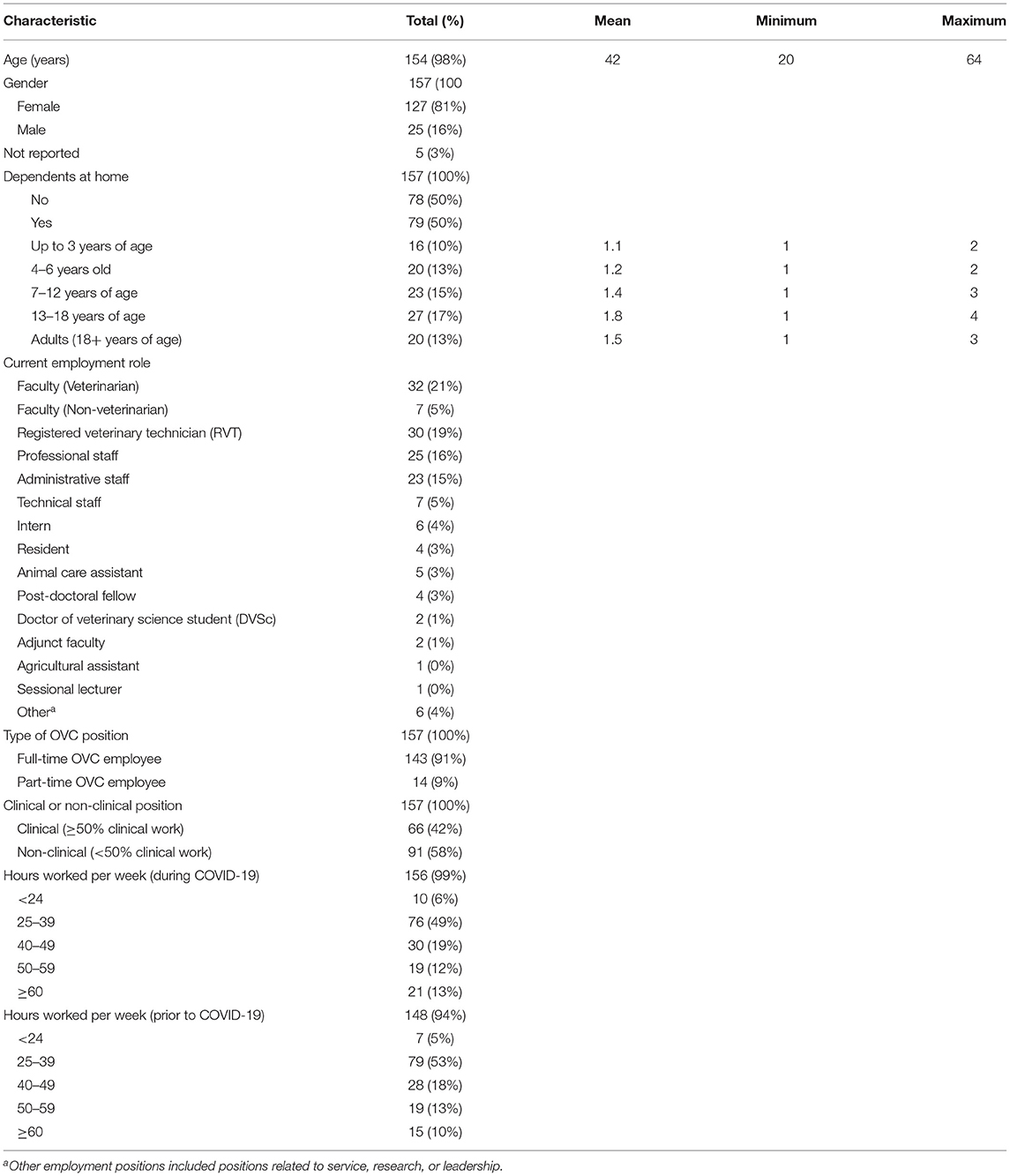

Descriptive statistics (i.e., means, maximums, minimums, and proportions) of demographic characteristics were summarized for all respondents.

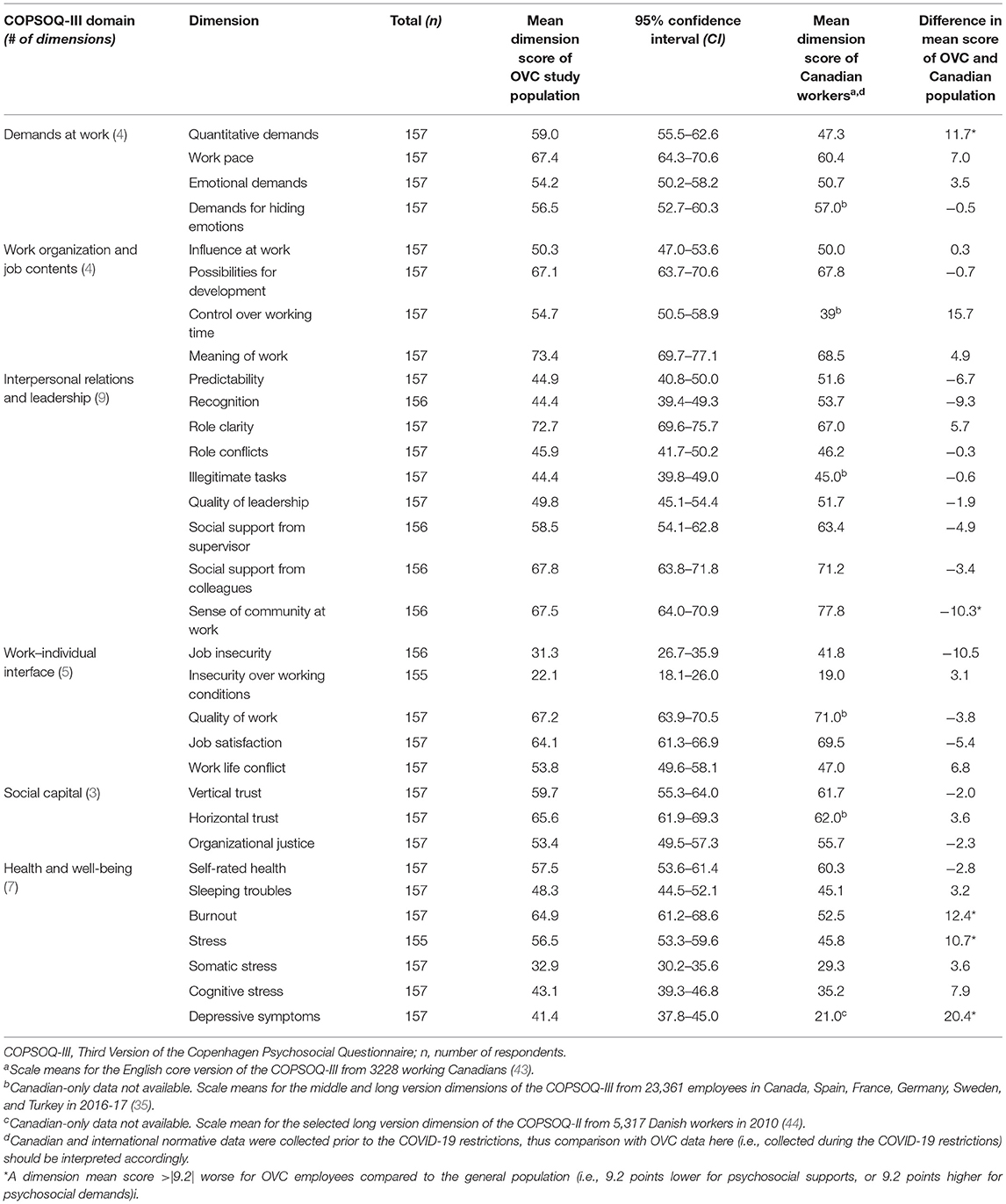

The COPSOQ-III scales were reported as mean scores from Likert Scale–type items for each dimension. A >|9.2| difference between the mean scores of COPSOQ-III dimensions of OVC respondents and normative populations was determined as an estimate of a “minimally important difference” (39), meaning that this difference is of a magnitude that is likely to have practical consequences for workplace- and individual-level well-being.

A COPSOQ-III domain was coded as worsened if >50% of informing dimensions were reported as having worsened since COVID-19 restrictions. That is, if a participant reported that half or more of the dimensions that inform a particular domain had worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic, this domain was coded as having worsened for this participant. Alternatively, if a participant reported that more than half of the dimensions in a domain had improved or remained the same since the COVID-19 pandemic, the domain was coded as having improved/remained the same for this participant, based on suggestive data that each dimension contributes to each Domain equally (35).

Multivariable logistic regression models were separately created for each of the six psychosocial work domains of the COPSOQ-III: Demands at Work, Work Organization and Job Contents, Interpersonal Relations and Leadership, Work–Individual Interface, Social Capital, and Health and Well-being (35). Guided by previous research and a causal diagram, independent variables of interest were identified a priori and included: gender, hours worked during COVID-19, age, employment position (full-time vs. part-time), the presence of dependents at home, and clinical vs. non-clinical role. All independent variables were examined for collinearity using Pearson's rank correlation coefficient (40); a correlation of >|0.80| was determined as highly collinear. When two variables were highly collinear, the one with most complete data and biological plausibility was retained. Biological plausibility refers to existing biological, or in this case social models, that may explain an association, such as the number of hours worked during COVID-19 and burnout symptoms, for example (41).

To build the main effects multivariable models, univariable logistic regressions were first created to identify independent variables to be included in the main effect models with a liberal p-value (p < 0.20). Continuous independent variables were assessed for linearity with a logit transformed Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (i.e., Lowess) curve (40). If a variable was not found to be linear, it was transformed quadratically, or categorized, as needed. Each multivariable model was then built using manual backwards selection, comparing full and reduced models with Likelihood Ratio tests (40). All independent variables were assessed for confounding (defined as a 30% change in coefficients on removal of the variable) (40). If confounding was present, the variable was retained in the main effects models regardless of statistical significance. Pair-wise interactions for all the independent variables were created and tested for significance. Statistical significance was determined as p < 0.05. Odds ratios (OR) were reported for all independent variables maintained in the final models, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Goodness-of-fit for the final models was assessed with Pearson chi-squared tests for binary data, and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests for binomial data. The influence of individual observations and covariate patterns was assessed with scatterplots of Delta-beta, Delta-deviance, and Delta-Chi-squared (40). No data were removed unless an error was clearly identified. STATA v.16 software (42) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Study Respondents

The final sample size was 157 respondents, which represents a response percentage of ~25% (157/620). No questionnaire questions were mandatory beyond the consent question, so sample sizes vary as noted. The characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 2.

The COPSOQ-III: Descriptive Statistics of Dimensions

The results from the COPSOQ-III are presented in Table 3 with means and 95% CIs for all dimensions, as well as normative data for international and Canadian populations for comparison (35, 43, 44).

Table 3. A comparison of psychosocial work demands of the OVC respondents and that of Canadian and International Workers based on COPSOQ-III dimensions.

Respondents responded to nearly all items, with the percentages of missing values being under 3% for all dimensions. Mean scores of psychosocial dimensions that were reported as >|9.2| worse (i.e., higher demands and/or lower supports) than the normative population, and thus potential areas of concern for workplace and personal well-being, included: quantitative demands, recognition, sense of community at work, burnout, stress, and depressive symptoms (Table 3).

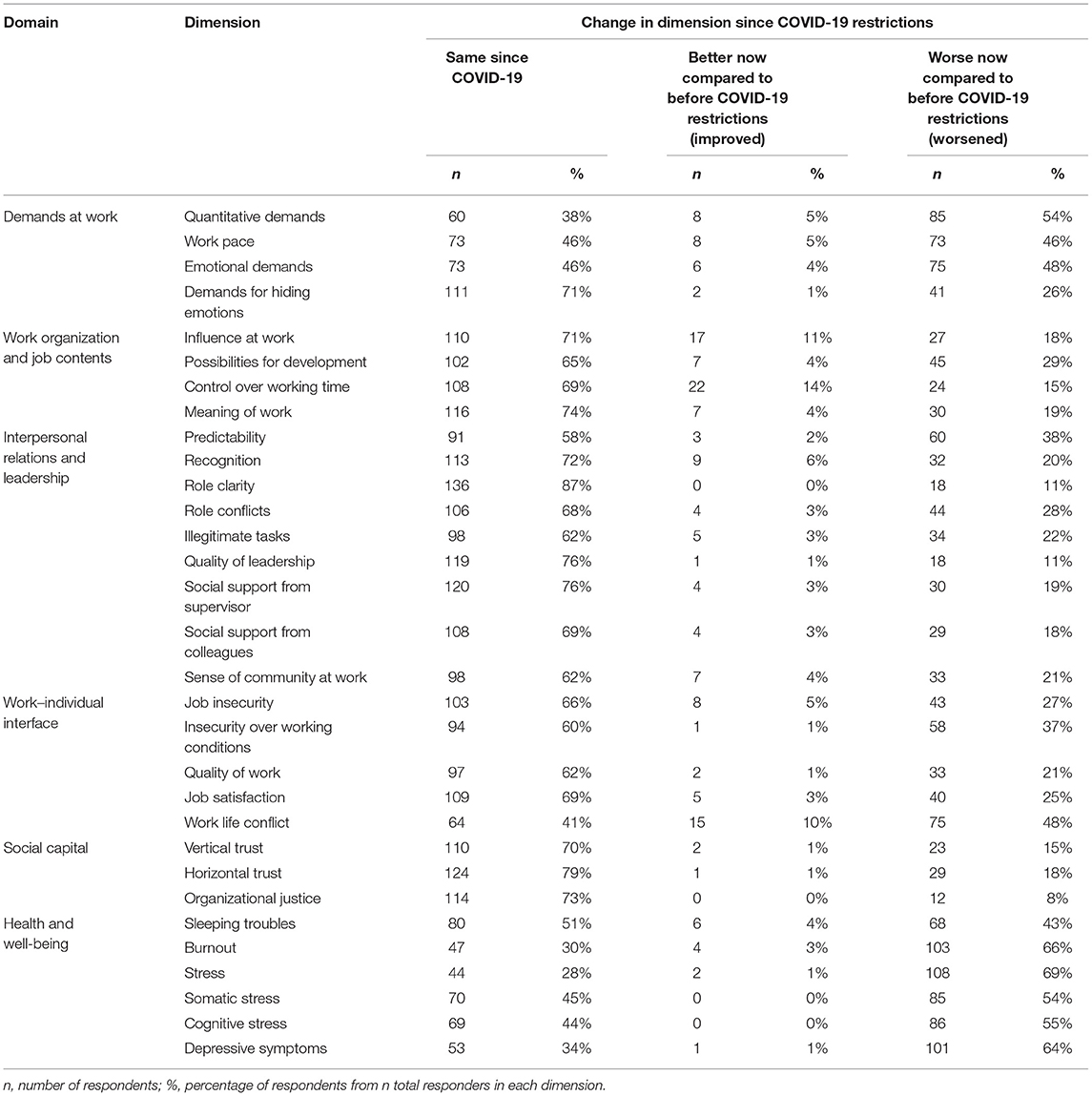

Change in COPSOQ-III Dimensions Since COVID-19

Table 4 presents respondents' perceived changes in the COPSOQ-III dimensions, including the health and well-being dimensions, since the onset of COVID-19 restrictions. The majority of respondents reported eight psychosocial dimensions as having worsened since COVID-19. These included quantitative demands, emotional demands, work life conflict, burnout, stress, somatic stress, cognitive stress, and depressive symptoms. The dimensions of burnout (% of respondents = 66%, n = 103), stress (69%, n = 108), and depressive symptoms (64%, n = 101) had the greatest proportion of respondents reporting that these conditions had worsened. Marginally lower proportions were reported for the dimensions of quantitative demands (% of respondents = 54%, n = 85), emotional demands (48%, n = 75), work-life conflict (48%, n = 75), somatic stress (54%, n = 85) and cognitive stress (55%, n = 86), as having worsened since the onset of COVID-19 restrictions. The dimension of work pace had the same proportion of respondents reporting that this dimension had either remained the same or worsened, since the onset of COVID-19 restrictions (48%, n = 73). The majority of respondents reported the remaining 22 psychosocial dimensions as having remained the same since the onset of COVID-19 restrictions. Role clarity (% of respondents = 87%, n = 136), quality of leadership (76%, n = 119), social support from supervisor (76%, n = 120), and horizontal trust (79%, n = 124), had the greatest proportion of respondents reporting that these dimensions remained the same since the COVID-19 restrictions. There were no psychosocial dimensions for which a majority of respondents reported an improvement since the COVID-19 restrictions.

Table 4. Number and proportion of respondents reporting the COPSOQ-III dimensions had improved, remained the same, or worsened, since COVID-19 restrictions.

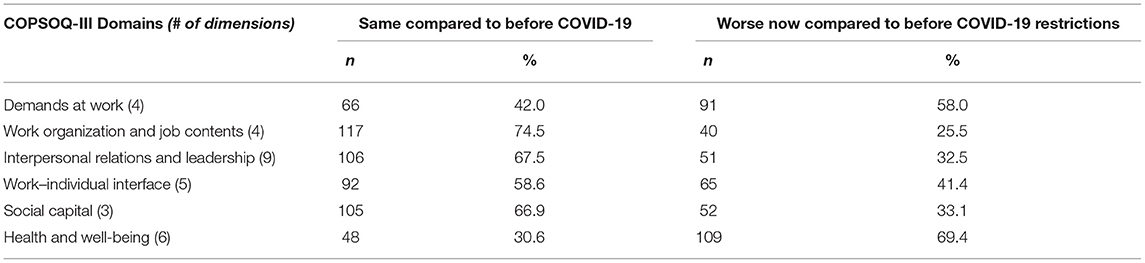

Change in COPSOQ-III Domains Since COVID-19

Table 5 presents the proportion of respondents that reported that a COPSOQ-III domain had worsened since the onset of COVID-19 restrictions. Nearly 60% (n = 91) of respondents reported that Demands at Work had worsened, and nearly 70% (n = 109) reported worsened Health and Well-being. All other domains were reported by the majority of respondents as having remained the same since the COVID-19 restrictions.

Table 5. Number and proportion of respondents reporting the COPSOQ-III domains had remained the same vs. worsened, since COVID-19 restrictions.

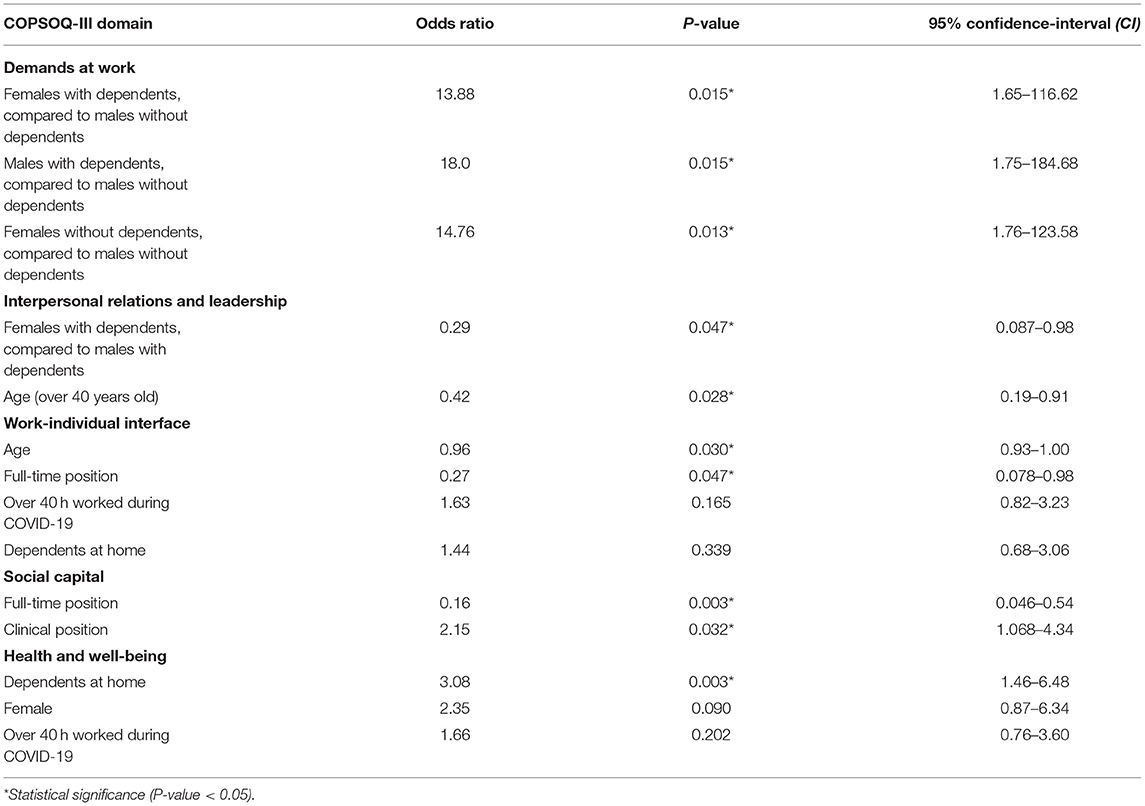

Predictors for Reporting Worsened COPSOQ-III Domain Since COVID-19

Table 6 presents the final logistic regression models assessing independent variables associated with reporting worsened COPSOQ-III domains since COVID-19 restrictions.

Table 6. Logistic regressions for reporting worsened COPSOQ-III domains with explanatory variables of full-time position, dependents at home, gender, clinical position, age, and hours worked per week during the COVID-19 restrictions.

Demands at Work

In the logistic regression model for the Demands at Work domain, the effects of gender and the presence of dependents at home were conditional on each other, and thus had a significant interaction. Respondents identifying as female with dependents at home had significantly greater odds of reporting worsened Demands at Work than males without dependents at home (OR: 13.88, p = 0.015; 95% CI: 1.65–116.62). Similarly, males with dependents at home were found to have significantly greater odds of reporting worsened Demands at Work, compared to males without dependents at home (OR: 18.0, p = 0.015; 95% CI: 1.75–184.68). Amongst those without dependents, female respondents had a significantly greater odds of reporting worsened Demands at Work, compared to males (OR: 14.76, p = 0.013; 95% CI: 1.76–123.58).

Interpersonal Relations and Leadership

In the model for the Interpersonal Relations and Leadership domain, a similar gender-dependent interaction was observed; however, females with dependents at home had a significantly lower odds of reporting worsened Interpersonal Relations and Leadership than males with dependents at home (OR: 0.29, p = 0.047; 95% CI: 0.087–0.98). Age was a protective factor, with respondents older than 40 years of age being significantly less likely to report worsened Interpersonal Relations and Leadership than respondents under the age of 40 (OR: 0.42, p = 0.028; 95% CI: 0.19–0.91).

Work-Individual Interface

A protective effect of age was similarly observed in the model for the Work-Individual Interface domain. Specifically, each yearly increase in age correlated to a significantly lower odds of reporting worsened Work-Individual Interface (OR: 0.96, p = 0.030; 95% CI: 0.93–1.00). Respondents in a full-time position were significantly less likely to report worsened Work-Individual Interface than those in part-time positions (OR: 0.27, p = 0.047; 95% CI: 0.078–0.98).

Social Capital

In the model for the Social Capital domain, respondents in full-time positions had significantly lower odds of reporting that this domain worsened with COVID-19 restrictions (OR: 0.16, p = 0.003; 95% CI: 0.046–0.54); that is, part-time employees had increased odds of reporting worsened Social Capital. In contrast, those working in a clinical position had approximately two times greater odds of reporting significantly worsened Social Capital, compared to those in non-clinical positions (OR: 2.15, p = 0.032; 95% CI: 1.07–4.34).

Health and Well-Being

Lastly, in the model for the Health and Well-being domain, respondents with dependents at home had three times greater odds of reporting significantly worsened Health and Well-being, compared to those without dependents at home (OR: 3.08, p = 0.003; 95% CI: 1.46–6.48). There was also a tendency for females to have a higher odds of reporting worsened Health and Well-being, compared to males, but this difference was not statistically significant (OR: 2.35, p = 0.090; 95%CI: 0.87–6.34).

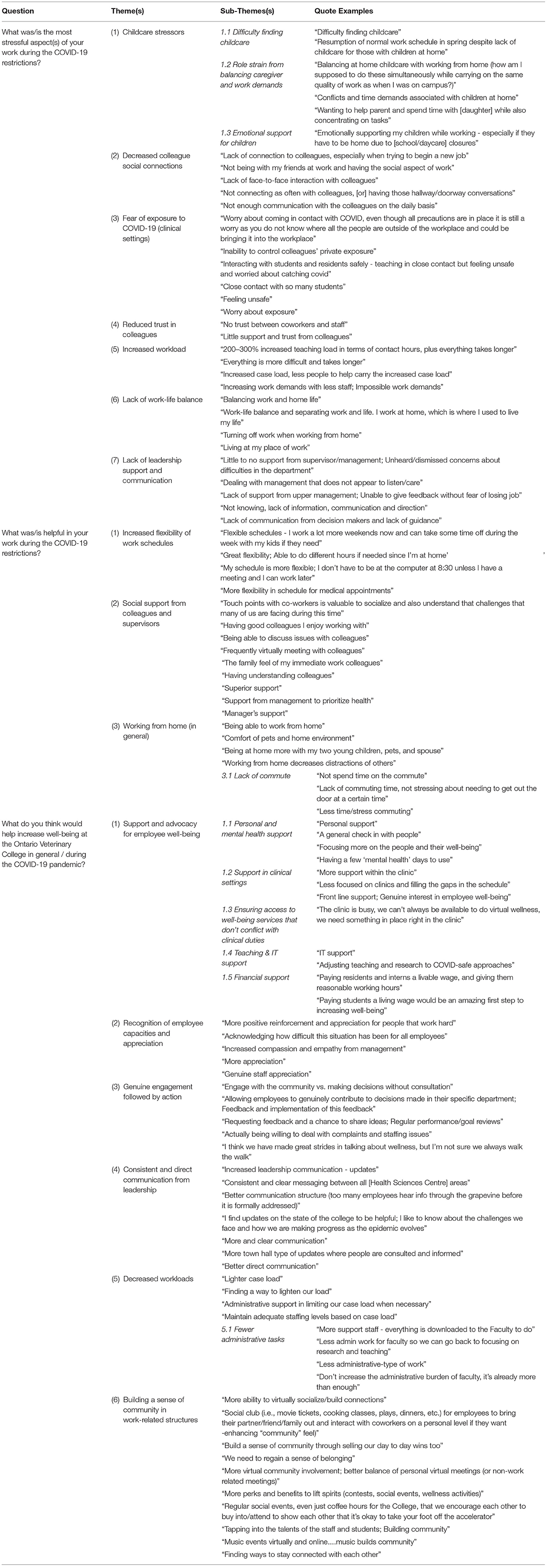

Qualitative Themes of Open-Text Questions

Respondents answered open-text questions regarding the most stressful aspects of their work during the COVID-19 restrictions (n = 110), what was helpful during the COVID-19 restrictions (n = 94), and what would help increase well-being at the OVC in general (n = 95) and during the current COVID-19 restrictions specifically (n = 87). Table 7 presents the themes and sub-themes derived from these data and direct exemplar quotations from respondents.

Table 7. Qualitative themes of respondent's open-text answers regarding workplace stressors, supports, and perceived needs to improve well-being at the OVC, during COVID-19.

Stressors Faced by Employees During COVID-19

The most common themes reported by respondents as work stressors during COVID-19 included: childcare (with sub-themes of difficulty finding childcare when resuming normal work schedules, role strain from balancing caregiver and work demands, and the need to emotionally support children while working); decreased opportunities to socially connect with colleagues due to working-from-home; the fear of COVID-19 exposure in clinics (i.e., physical proximity of staff, feeling unsafe when teaching residents, the inability to control other's private exposures, etc.); and reduced trust in co-workers and staff (Table 7). Increased workload (i.e., higher teaching and clinical workloads, more time required to perform similar tasks as pre-pandemic, etc.), lack of work-life balance due to work-from-home restrictions, and perceived lack of support and communication from leadership, were also themes identified as stressful aspects of respondents' work during COVID-19.

What Was Most Helpful for Employees During COVID-19

Complementary themes were cited as being most helpful during the COVID-19 restrictions and included: the increased flexibility of work schedules and hours; the opportunity to receive social support from both colleagues and supervisors; and the ability to work from home in general. The theme of working from home in general included the sub-theme of a lack of commute to work, which respondents reported helped to decrease stress and increase free time.

What Would Help to Increase Well-Being at Work, in General and During COVID-19 Specifically

When speaking directly to increasing well-being in general and during the COVID-19 restrictions, common themes included: more support and advocacy for employee well-being (with sub-themes of more personal and mental health support, lower workloads in clinics, greater access to well-being services that do not conflict with clinical duties, more teaching and technology support for faculty, and greater financial support for students, interns, and residents); more recognition of employee capacities and appreciation from leadership (i.e., more recognition of the high work demands caused by COVID-19, acknowledging the difficulties of COVID-19 for all employees, etc.); more genuine engagement with employees followed by action; more consistent and direct communication from leadership; and lower clinical and teaching workloads (with a sub-theme of minimizing administrative tasks for faculty). The theme of building a sense of community (i.e., through virtual socializing opportunities to build connections, creating social clubs, sharing personal stories and day-today wins of colleagues, cultivating a sense of belonging online, etc.), was also frequently reported by respondents as a positive step forward (Table 7).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess a broad range of psychosocial work demands of employees within a veterinary academic institution during the COVID-19 pandemic with validated psychometric scales. Unquestionably, demands in veterinary academia are high. We observed that the COVID-19 pandemic made worse several psychosocial demands, including home-based work challenges, increased workload and pace, reduced health and well-being, worsened interpersonal relations, and higher work demands. Below, we discuss the factors that were associated with worsened psychosocial work demands and health and well-being (including the COVID-19 pandemic, gender, caregiving, and employment characteristics), and conclude with recommendations for institutional-level interventions to aid individual- and institution-level well-being.

COVID-19 and Work Demands

Amongst participating employees, work demands, and work pace were consistently reported as having intensified with the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings align with other recent occupational studies. For example, in May and October of 2020, two international studies with >3,000 participants in academia from 103 countries reported that the biggest change since COVID-19 was working more hours per day to accomplish the same tasks as before the pandemic (45). An increase in workload may come from the transition to digital learning, with academics reporting roughly triple the preparation time for a 1-h online lecture compared to the same lecture taught in-person (46). Increased work demands and work pace have also been reported for clinical veterinary professionals. Specifically, since the onset of COVID-19 restrictions, there has been a worldwide increase in pet ownership, increasing the demand for veterinary services such that 18% of North American practices added additional appointment slots, and 77% have needed to introduce new curbside appointments to accommodate COVID-19 social distancing policies (28). Amongst Canadian veterinary practices, 78% of have increased their client load since the onset of COVID-19, representing the greatest increase out of 18 participating countries in the international survey, including the US, UK, and Australia (28). It is expected then that 27% of participating veterinarians in the aforementioned study also reported a desire to decrease their work hours or move into a part-time veterinary position post-COVID-19 (28). A second contributing factor to the increased work demands observed here may stem from augmented employee absences, the provision of reduced or flexible work hours, or employees leaving workplaces altogether. Prior to the COVID-19 restrictions, 71% of veterinary employers in a Canadian sample said it was difficult to recruit qualified veterinary candidates, and two-thirds said they would hire additional veterinarians immediately, if candidates were available (47). As such, high workplace demands reported by veterinarians and veterinary team members were also likely affected in part by COVID-19 impacts on the availability and retention of veterinary employees.

Female Caregivers and Work Demands

The implementation of home-based work policies with COVID-19 can particularly increase the permeability between work and family for females (48, 49). Thus, it is not surprising that we observed a gender disparity between male and female caregivers when reporting worsened work demands during the pandemic. Specifically, females with and without dependents at home had much greater odds of reporting worsened demands at work, compared to males with and without dependents. These gendered impacts are supported by international studies which report that more females than males have experienced difficulty managing their time (53 vs. 39%), balancing family, household and work responsibilities (56 vs. 44%), and managing childcare or homeschooling children (65 vs. 55%), due to COVID-19 (50). In a 2021 Statistics Canada report, 64% of females in the general population likewise stated that they were the parent that mostly performed homeschooling or helped children with homework during COVID-19, compared to only 19% of males, and 46% of males said that childcare duties at home were mostly their partner's responsibility (51). Importantly however, we cannot differentiate whether the 46% of males had female or male partners. Corroborated with this literature, our findings suggest that caregivers, and especially females, have experienced higher work demands due to pre-established gender roles becoming worsened by the pandemic and home-based work restrictions (52). This may have long-term career consequences. For example, female faculty members in non-medical and medical institutions (53), and especially those with children (54), were reported to be less likely to submit grant proposals and journal articles (55) or register new projects (56), since the onset of COVID-19 restrictions.

Females, Caregivers, and Well-Being

Higher work demands, coupled with the need to balance childcare duties, may have also contributed to females and caregivers experiencing worsened health and well-being during the pandemic, as observed in the present study. Current COVID-19 research supports this, citing significantly higher levels of psychological distress in mothers of elementary school-age and younger children since the onset of the pandemic (57). Given that female representation in the veterinary and academic professions is rising in the US and Canada (58, 59), the pandemic may have increased the risk of mental health and well-being challenges for a significant portion of these professional populations. Longitudinal cohort studies assessing the long-term impacts of COVID-19-related mental health outcomes, and potential impacts on career progression and retention, would provide important insight.

Male Caregivers and Interpersonal Relations

In contrast to our aforementioned findings of females having higher odds of negative psychosocial outcomes than males, we observed that males with dependents at home experienced significantly worsened interpersonal relations with colleagues and supervisors than females with dependents. Interpersonal support has been reported to have a more protective effect against stress and burnout for females compared to males during COVID-19 (60, 61). Herein, females may have found interprofessional supports to be more constructive when coping with childcare stressors, compared to males (61). Additionally, sense of recognition, quality of leadership, and supervisor support also inform the Interpersonal Relations and Leadership domain. While we were unable to investigate further, it may be that males faced greater adversity from supervisors, or greater personal stress to approach supervisors, when managing their new childcare roles, particularly if they had not traditionally held this role in their families. For example, requesting accommodations for childcare needs such as homeschooling, or alternative work hours to manage home duties, may have placed strain on their relations with supervisors, and downstream, their sense of recognition and support. In fact, a US study reported that although females spent more time overall on childcare, males significantly increased their childcare role during the pandemic (62), and another study in Italy reported that 40% of males spent more time on housework and 51% spent more time on childcare during COVID-19, than before pandemic restrictions (63). We presume that females faced these work-life conflicts and professional tensions prior to the COVID-19 restrictions since they already faced higher childcare duties than males pre-pandemic (57). Given that professional relations for females were not observed to decrease with the pandemic, this may indicate that females face a lower baseline of supervisor support and recognition, compared to males (64), but we do not have the data to test this hypothesis. Further research into this area would be informative.

Clinical Professionals and Social Capital

Recent studies on Canadian veterinarians report that COVID-19 has limited job resources (i.e., co-worker or staff support, access to sufficient or high quality equipment, and readily available knowledge resources such as mentors, journals, books, etc.) (65). In the present study, lower Social Capital was reported by clinical and part-time OVC employees (of which 57% are also clinically based), compared to respondents in non-clinical and full-time roles, respectively. A lack of job resources in clinical settings may have contributed to feelings of unjust workload distribution, decreased interprofessional support, and unmet professional needs from leadership, which negatively impact the Social Capital domain. Concerns over personal health and fear of becoming infected with the COVID-19 virus were also reported as the most prevalent stressors for front-line healthcare providers caring for people during the pandemic (66). For clinical OVC employees, increased stress over teaching students and residents safely in clinics, decreased trust in colleagues, and feeling unsafe in clinical settings, were also cited as work-related stressors during COVID-19. Given that the Social Capital domain is informed by trust between colleagues and supervisors, clinical professionals may have felt increasingly concerned over whether colleagues and students were appropriately abiding by social-distancing protocols and health measures, possibly contributing to feelings of decreased interprofessional trust. With increased workplace absences since the onset of COVID-19, workload distributions may have fallen more heavily on employees continuing to work during the COVID-19 restrictions, further contributing to feelings of unfairness or distrust in the workplace. This is concerning, as social cohesion and inter-professional trust are reported as mediating factors in the prevalence of emotional exhaustion and burnout in the medical profession (67).

Recommendations

The combination of increased workplace demands and decreased well-being observed in the present study is concerning in that it not only negatively impacts employees as individuals, but may also decrease job engagement (68), increase turnover rate and burnout (69, 70), reduce student retention (71), and challenge the ability to respond to students' needs at staff and institutional levels in academia (70). Amongst medical professionals caring for human patients, increased work demands can impact patient safety, quality of care, client satisfaction, and patient mortality rates (72, 73); it is reasonable to assume similar negative outcomes for veterinary professionals, although specific research is lacking. We recommend that academic and medical institutions focus on shaping a workplace culture that addresses occupational and psychosocial stressors to prevent similar downstream outcomes. Kumar (74) appropriately notes that too much focus on individual-level strategies does not effectively improve occupational well-being, despite them being recommended commonly by organizations. In fact, well-being interventions at the organizational-level are reported to have greater impacts on reducing burnout and promoting wellness amongst physicians, than individual-initiated interventions (75). To this end, we investigated the perceived needs of respondents for improving well-being at the OVC to help inform meaningful and institutional-level recommendations.

Respondents proposed a number of strategies to help to increase well-being during the COVID-19 restrictions and in-general (i.e., irrespective of the pandemic), including: more recognition and acknowledgment of the increased workloads faced by employees; more support for employees' personal, occupational, and financial needs; more direct communication from leadership on decisions that could help planning around COVID-19 and general College updates; more genuine employee engagement and follow-up action; and a stronger sense of community within work-related structures. Specific examples provided by respondents included more support staff to reduce workloads associated with administrative duties, providing technology assistance to improve online working conditions and support faculty with online teaching delivery, offering more mental health days, increasing wages for residents and interns, providing flexible schedules and work hours when working from home, increasing virtual social opportunities to connect with colleagues (i.e., social nights, cooking classes, music events, etc.), allowing employees to contribute to decisions made in their specific department, giving clear updates on institutional decisions that shape the domains of teaching and learning, and facilitating direct pathways for employees to voice personal needs with leadership followed by genuine recognition and action.

Systems-wide approaches such as these have been implemented in hospital-based academic centers to address similar occupational needs in medicine. Such strategies include increasing staff in administrative and well-being departments to facilitate employee recognition and manage workloads, revising institutional policies to accommodate employee support systems, increasing counseling opportunities, building inter-professional community through interdisciplinary events, and establishing frequent collaborative meetings between management and employees regarding employee needs (76). In evaluating such strategies, employees were significantly more likely to engage in wellness supports and resources, thereby contributing to employee empowerment and well-being at individual- and institutional-levels (76, 77). Difficulty accessing well-being services and scheduled times conflicting with work obligations are commonly cited barriers to employee engagement in the medical profession (78). Employees in the present study similarly indicated difficulty attending institutionally offered well-being programming due to conflicts with their clinical duties or other work responsibilities. We recommend institutions prioritize access to support services that are feasible for employees in all roles.

Often overlooked in institutional-level interventions is the importance of collaboration between leadership and employees (11), which was repeatedly indicated as desired by respondents in this study. Facilitating structural empowerment in the workplace by leadership (i.e., opportunity, information, support, resources) has been shown to contribute to improved psychological empowerment for employees (i.e., meaning, confidence, autonomy, recognition), as observed in interdisciplinary healthcare teams prior to, and during the COVID-19 pandemic (79–82). Given that aspects of structural and psychological empowerment were cited as lacking and desired by respondents here, implementing these ideals into institutional programming would be a productive starting point. Specifically, leadership training programs focused on facilitating direct communication pathways between supervisors and employees, aligning leadership and employee organizational values, empowering employees by redesigning work shifts to reflect expressed needs (i.e., flexible hours, part-time work, etc.), and developing as well as implementing targeted interventions that modify local work factors contributing to employee ill-being in organizational subunits (i.e., reducing administrative duties for faculty, decreasing clinical loads for clinicians, increasing financial support for students and residents, etc.), would be beneficial (83). In fact, focusing on specific issues raised by organizational subunits has been shown to aid in engaging and empowering employees as collaborators in shaping their occupational environment (83). More consistent communication was also reported as a common desire amongst respondents, suggesting that more frequent and consistent check-ins and updates, followed by immediate de-briefs on the concerns raised, be focused upon.

With COVID-19 disproportionately impacting females and caregivers in the present study, special consideration should also be given to increasing accessibility to policies that support caregiver needs, such as flexible work hours, sick leave, time off, and personal accommodations, as needed. Additional research funding supports (i.e., top-up funds, post-doctoral, graduate student, and/or research assistant stipends) could be made available to females and caregivers to help off-set some of the challenges they have disproportionately faced, as well as paid faculty leaves and reduced teaching loads. This said, in medical academia, the absence of clear information about eligibility, the influence of supervisor opinions, and concerns about how participation might burden coworkers or adversely impact workflow and grant funding, are cited barriers to employees engaging in work-family programs or leaves, when provided (84). Gender-neutral interventions have also been implemented by academic institutions to reduce COVID-19 impacts, such as providing tenure-track faculty with a 1-year extension, increasing research and teaching support (i.e., hiring research assistants from faculty funds, increasing support staff), establishing “COVID-19 committees” to address the impacts of COVID-19 on faculty and staff across the institution, and reducing non-essential administrative-type work (i.e., curriculum reviews, peer teaching evaluations) (85). Although such strategies may lessen work demands, gender-neutral tenure-track extensions and faculty leaves have been shown to reduce female tenure probability by 22%, while increasing male tenure probability by 19% (86), thus contributing to the already widening gender-gap caused by COVID-19. It would seem then that a cultural shift surrounding gender, caregiving, and work-family balance is needed within organizations to meaningfully implement policies and solutions that attend to female and caregiver needs.

Occupational well-being strategies would ideally also focus on fostering social cohesion and organizational resilience. For example, some medical institutions and veterinary medicine colleges offer interprofessional mentorship programs, institutionally-driven professional development opportunities, and even the ability to join faculty “teams” that engage in social events (87, 88). Formalized interventions such as these can promote community-building, increase job satisfaction, reduce occupational stress, and prevent burnout, as observed in interdisciplinary healthcare teams and academic medicine (77, 87, 89). Importantly, these strategies also help to build organizational resilience, which better equips institutions to manage adversity during times of crisis, such as COVID-19 (90). We suggest younger and part-time employees be especially involved in these programs, given that they were at greater odds of experiencing worsened sense of community during COVID-19. The current COVID-19 restrictions may present barriers to the benefits of such programs by increasing screen time and the possible risk of “Zoom fatigue” (91). However, offering regular and on-going socialization opportunities post-COVID-19 can act as a preventative measure to equip institutions with a stronger foundation of social cohesion, and in turn, organizational resilience, in the face of future workplace-altering events.

The COVID-19 pandemic did provide several benefits for employees, including increased flexibility of work schedules and hours, the ability to work from home, and decreased commuting time. Continuing to provide some flexible work conditions for employees post-COVID-19 would help to maintain these positive outcomes. This may include the development of work-life balance programs that allow broad participation and tailoring to accommodate various career tracks, as well flexible work hours and opportunities to work-from-home occasionally, if desired (84). The transition to a virtual workplace has also offered employees the opportunity to frequently connect with colleagues online, which many respondents mentioned helped to foster collegial support during COVID-19 challenges. We recommend maintaining these beneficial aspects of online workspaces to continue supporting access to rapid communication, social support, and even professional development opportunities for employees post-COVID-19. To this end, hybrid workplace models are becoming increasingly implemented into organizational structures where work is split between remote and in-office settings. This innovative change may pose potential risks to informal communication, inter-professional information seeking and collaboration (i.e., employees seeking information from online sources more than professional colleagues), and increase “Zoom fatigue” (91, 92). However, shifting from in-person to online work environments can equally improve an individual's role in a professional network. Specifically, individuals previously in peripheral positions of an in-person professional social network are more likely to occupy a more central position in an online setting (93). This suggests that hybrid models may offer improved organizational inclusion through strengthened involvement and positive workplace culture (91, 92). More research into the psychosocial outcomes of hybrid structures in academic institutions specifically would be informative.

Limitations

This cross-sectional study assesses the psychosocial work demands and perceived needs of participating OVC employees at one moment in time. A relatively small sample size contributed to wide confidence intervals. A conservative response estimate of 25% also introduces the potential for non-response bias and under- or over-estimation of COPSOQ-III outcomes. The self-reported nature of our survey data may be subject to recall or social desirability bias when assessing pre- and post-pandemic demands. A recognized limitation of our study also arises from comparing our COPSOQ-III means to pre-COVID norms of Canadian and international working populations. Given that no COVID-19 data were available with the COPSOQ, direct comparison to other Canadian populations during the pandemic could not be made. Still, the COPSOQ-III is an internationally validated questionnaire with strong reliability and validity across diverse worker settings and workplace populations (34). Lastly, approximately one third of the sample are classified as professional or administrative staff and as such, the findings from these respondents may not be encompassing of all veterinary academia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides novel insight into the psychosocial work demands faced by employees in a veterinary academic institution as we continue to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings indicate that COVID-19 has increased the occupational demands and work-life conflicts, and decreased the health and well-being, of employees in our veterinary academic organization. We also noted particularly vulnerable groups, such as females, caregivers, part-time workers, and clinical employees, to be at greatest risk for experiencing worsened occupational stressors since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. From these findings, we suggest that evidence-based resources be implemented at the organizational-level in the OVC, and similar healthcare institutions, both during and after the COVID-19 restrictions, and offer examples. Continued research into the long-term mental health and career impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic is also critical to provide tailored well-being interventions for OVC employees, and similar professional populations. Exploring these outcomes would allow for more novel insights into how similar institutions nationally, and potentially internationally, can support clinical and academic professionals through the global transition to more online work settings.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of ethical restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to aGF5bGV5bWNrZWVlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Guelph Research Ethics Board (20-08-016). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Material preparation and data collection were performed by HM, AJ-B, RA, BN-K, and BG. Analysis was performed by HM and BH. The first draft of the manuscript was written by HM. All authors edited subsequent versions of the manuscript, contributed to the study's conception and design, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by the Ontario Veterinary College Dean's Office.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bartram DJ, Yadegarfar G, Baldwin DS. Psychosocial working conditions and work-related stressors among UK veterinary surgeons. Occup Med. (2009) 59:334–41. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp072

2. Hatch P, Winefield H, Christie B, Lievaart J. Workplace stress, mental health, and burnout of veterinarians in Australia. Aust Vet J. (2011) 89:460–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00833.x

3. Nett RJ, Witte TK, Holzbauer SM, Elchos BL, Campagnolo ER, Musgrave KJ, et al. Risk factors for suicide, attitudes toward mental illness, and practice-related stressors among US veterinarians. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2015) 247:945–55. doi: 10.2460/javma.247.8.945

4. Volk JO, Schimmack U, Strand EB, Vasconcelos J, Siren CW. Executive summary of the merck animal health veterinarian wellbeing study II. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2020) 256:1237–44. doi: 10.2460/javma.256.11.1237

5. Bartram DJ, Baldwin DS. Veterinary surgeons and suicide: a structured review of possible influences on increased risk. Vet Rec. (2010) 166:388–97. doi: 10.1136/vr.b4794

6. Perret JL, Best CO, Coe JB, Greer AL, Khosa DK, Jones-Bitton A. Prevalence of mental health outcomes among Canadian veterinarians. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2020) 256:365–75. doi: 10.2460/javma.256.3.365

7. Best CO, Perret JL, Hewson J, Khosa DK, Conlon PD, Jones-Bitton A. A survey of veterinarian mental health and resilience in Ontario, Canada. La Rev Vet Can. (2020) 61:166–72.

8. Nassar AK, Waheed A, Tuma F. Academic clinicians' workload challenges and burnout analysis. Cureus. (2019) 11:e6108. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6108

9. Popa-Velea O, Diaconescu LV, Gheorghe IR, Olariu O, Panaitiu I, Cernitanu M, et al. Factors associated with burnout in medical academia: an exploratory analysis of Romanian and Moldavian physicians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2382. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132382

10. Vukmirovic M, Rajovic N, Pavlovic V, Masic S, Mirkovic M, Tasic R, et al. The burnout syndrome in medical academia: psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the maslach burnout inventory—educators survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165658

11. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Civian JT, Gibbs BK, Coplit LD, Gillum LH, et al. Faculty vitality-surviving the challenges facing academic health centers: a national survey of medical faculty. Acad Med. (2015) 90:930–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000674

12. Shah DT, Williams VN, Thorndyke LE, Marsh EE, Sonnino RE, Block SM, et al. Restoring faculty vitality in academic medicine when burnout threatens. Acad Med. (2018) 93:979–84. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002013

13. Wright JG, Khetani N, Stephens D. Burnout among faculty physicians in an academic health science centre. Paediatr Child Health. (2011) 16:409–13. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.7.409

14. Reijula K, Räsänen K, Hämäläinen M, Juntunen K, Lindbohm ML, Taskinen H, et al. Work environment and occupational health of Finnish veterinarians. Am J Ind Med. (2003) 44:46–57. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10228

15. Bartram DJ, Yadegarfar G, Baldwin DS. A cross-sectional study of mental health and well-being and their associations in the UK veterinary profession. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2009) 44:1075–85. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0030-8

16. Joint ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health. Psychosocial Factors at Work; Occupational Safety and Health Series. Geneva (1984).

17. Epp T, Waldner C. Occupational health hazards in veterinary medicine: physical, psychological, and chemical hazards. La Rev Vet Can. (2012) 53:151–7.

18. Moore IC, Coe JB, Adams CL, Conlon PD, Sargeant JM. The role of veterinary team effectiveness in job satisfaction and burnout in companion animal veterinary clinics. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2014) 245:513–24. doi: 10.2460/javma.245.5.513

19. Fritschi L, Morrison D, Shirangi A, Day L. Psychological well-being of Australian veterinarians. Aust Vet J. (2009) 87:76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2009.00391.x

20. American Veterinary Medical Association. COVID-19 Impact on Veterinary Practices. Schaumburg, IL: American Veterinary Medical Association (2020).

21. Kinman G. Pressure points: a review of research on stressors and strains in UK academics. Educ Psychol. (2001) 21:473–92. doi: 10.1080/01443410120090849

22. Winefield AH, Jarrett R. Occupational stress in University staff. Int J Stress Manag. (2001) 8:285–98. doi: 10.1023/A:1017513615819

23. Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The job content questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. (1998) 3:322–55. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.3.4.322

24. Stansfeld S, Shipley M, Head J, Fuhrer R. Repeated job strain and the risk of depression: longitudinal analyses from the whitehall ii study. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:2360–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300589

25. Mausner-Dorsch H, Eaton WW. Psychosocial work environment and depression: epidemiologic assessment of the demand-control model. Am J Public Health. (2000) 90:1765–70. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.11.1765

26. Ganster DC, Rosen CC. Work stress and employee health. J Manage. (2013) 39:1085–122. doi: 10.1177/0149206313475815

27. Aboa-Éboulé C, Brisson C, Maunsell E, Mâsse B, Bourbonnais R, Vézina M, et al. Job strain and risk of acute recurrent coronary heart disease events. J Am Med Assoc. (2007) 298:1652–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1652

28. CM Research LTD. COVID-19 Global Pandemic Impact on the Veterinary Market. (2021). Available online at: https://www.canadianveterinarians.net/documents/vet-survey-2020-part-1-covid-19-global-pandemic-impact-on-vet-market (accessed April 15, 2021).

29. Malisch JL, Harris BN, Sherrer SM, Lewis KA, Shepherd SL, McCarthy PC, et al. Opinion: in the wake of COVID-19, academia needs new solutions to ensure gender equity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:15378–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010636117

30. Daumiller M, Rinas R, Hein J, Janke S, Dickhäuser O, Dresel M. Shifting from face-to-face to online teaching during COVID-19: the role of University faculty achievement goals for attitudes towards this sudden change, and their relevance for burnout/engagement and student evaluations of teaching quality. Comput Human Behav. (2021) 118:106677. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106677

31. Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Franchi T, Kerwan A, Griffin M, Soleil C, Del Mundo J, et al. Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on scientific research and implications for clinical academic training – a review. Int J Surg. (2021) 86:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.12.008

32. Sethi BA, Sethi A, Ali S, Aamir HS. Impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on health professionals. Pakistan J Med Sci. (2020) 36:S6. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2779

34. International COPSOQ Network. COPSOQ III. Guidelines and Questionnaire. International COPSOQ Network. (2019)

35. Burr H, Berthelsen H, Moncada S, Nübling M, Dupret E, Demiral Y, et al. The third version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Saf Health Work. (2019) 10:482–503. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2019.10.002

36. Ramkissoon A, Smith P, Oudyk J. Dissecting the effect of workplace exposures on workers' rating of psychological health and safety. Am J Ind Med. (2019) 62:412–21. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22964

37. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf D, Sher KJ, editors. APA Handbook of Research Methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. American Psychological Association (2012). p. 57–71. doi: 10.1037/13620-004

38. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

39. Pejtersen J, Bue Bjorner J, Hasle P. Determining minimally important score differences in scales of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Scand J Public Health. (2010) 38:33–41. doi: 10.1177/1403494809347024

40. Dohoo I, Martin W, Stryn H. Methods in Epidemiological Research. First. Charlottetown, PEI, Canada: VER, Inc. (2012).

41. Fedak KM, Bernal A, Capshaw ZA, Gross S. Applying the Bradford Hill criteria in the 21st century: how data integration has changed causal inference in molecular epidemiology. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. (2015) 12:14. doi: 10.1186/s12982-015-0037-4

43. Oudyk J, Smith P, Aversa T, Haines T MIT Working Group. Psychometric properties of the Canadian English and French COPSOQ-III (Core) Survey. Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers and the Mental Injuries Tool (MIT) Group (2019).

44. Pejtersen J, Søndergå T, Kristensen RD, Borg V, Bue Bjorner J. The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scand J Public Health. (2010) 38:8–24. doi: 10.1177/1403494809349858

45. De Gruyter. Locked Down, Burned Out: Publishing in a Pandemic: The Impact of Covid on Academic Authors. (2020). Available online at: https://blog.degruyter.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Locked-Down-Burned-Out-Publishing-in-a-pandemic_Dec-2020.pdf (accessed April 16, 2021).

46. Gewin V. Pandemic burnout is rampant in academia. Nature. (2021) 591:489–91. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00663-2

48. Çoban S. Gender and telework: work and family experiences of teleworking professional, middle-class, married women with children during the Covid-19 pandemic in Turkey. Gender Work Organ. (2021). doi: 10.1111/gwao.12684

49. Hilbrecht M, Shaw SM, Johnson LC, Andrey J. “I'm home for the kids”: contradictory implications for work-life balance of teleworking mothers. Gender Work Organ. (2008) 15:454–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00413.x

50. Skinner M, Betancourt N, Wolff-Eisenberg C. The disproportionate impact of the pandemic on women and caregivers in academia. Anal Policy Obs. (2021). doi: 10.18665/sr.315147

51. Statistics Canada. Caring for Their Children: Impacts of COVID-19 on Parents (2021). Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00091-eng.htm (accessed April 28, 2021).

52. Chung H, van der Lippe T. Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender equality: introduction. Soc Indic Res. (2020) 151:365–81. doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x

53. Myers KR, Tham WY, Yin Y, Cohodes N, Thursby JG, Thursby MC, et al. Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat Hum Behav. (2020) 4:880–3. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0921-y

54. Krukowski RA, Jagsi R, Cardel MI. Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Womens Heal. (2021) 30:341–7. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8710

55. Cui R, Ding H, Zhu F. Gender inequality in research productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Manuf Serv Oper Manag. (2020) doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3623492

56. Viglione G. Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here's what the data say. Nature. (2020) 581:365–6. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01294-9

57. Zamarro G, Prados MJ. Gender differences in couples' division of childcare, work and mental health during COVID-19. Rev Econ Househ. (2021) 19:11–40. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09534-7

58. Chieffo C, Kelly AM, Ferguson J. Trends in gender, employment, salary, and debt of graduates of US veterinary medical schools and colleges. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2008) 233:910–7. doi: 10.2460/javma.233.6.910

59. Statistics Canada. Number and Salaries of Full-Time Teaching Staff at Canadian Universities (Final), 2018/2019. (2019). Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/191125/dq191125b-eng.htm (accessed May 15, 2021).

60. Statistics Canada. Gender Differences in Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Canada (2021). Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00047-eng.htm (accessed April 15, 2021).

61. Jacques-Avinõ C, López-Jiménez T, Medina-Perucha L, De Bont J, Goncalves AQ, Duarte-Salles T, et al. Gender-based approach on the social impact and mental health in Spain during COVID-19 lockdown: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e044617. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044617

62. Sevilla A, Smith S. Baby Steps: THE Gender Division of Childcare During the COVID19 Pandemic. Oxford Rev Econ Policy. 36:S169–86 (2020).

63. Del Boca D, Oggero N, Profeta P, Rossi M. Women's and men's work, housework and childcare, before and during COVID-19. Rev Econ Househ. (2020) 18:1001–17. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09502-1

64. Radey M, Schelbe L. Gender support disparities in a majority-female profession. Soc Work Res. (2020) 44:123–35. doi: 10.1093/swr/svaa004

65. Lee R, Son Hing L. Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. A Report of Veterinarian Well-Being and Ill-Being During COVID-19. Guelph, ON (2020).

66. Cabarkapa S, Nadjidai SE, Murgier J, Ng CH. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: a rapid systematic review. Brain Behav Immun Heal. (2020) 8:100144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100144

67. Welp A, Meier LL, Manser T. The interplay between teamwork, clinicians' emotional exhaustion, and clinician-rated patient safety: a longitudinal study. Crit Care. (2016) 20:110. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1282-9

68. Fiabane E, Giorgi I, Sguazzin C, Argentero P. Work engagement and occupational stress in nurses and other healthcare workers: the role of organisational and personal factors. J Clin Nurs. (2013) 22:2614–24. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12084

69. Zhang Y, Feng X. The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2011) 11:235. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-235

70. Watts J, Robertson N. Burnout in University teaching staff: a systematic literature review. Educ Res. (2011) 53:33–50. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2011.552235

71. Miller L. The Level of Decision Making, Perceived Influence and Perceived Satisfaction of Faculty and Their Impact on Student Retention in Community Colleges. Erie, PA: Gannon Univ ProQuest Diss Publ. (2017).

72. Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, White DA, Adams EL, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a Meta-Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. (2017) 32:475–82. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9

73. Welp A, Meier LL, Manser T. Emotional exhaustion and workload predict clinician-rated and objective patient safety. Front Psychol. (2015) 5:1573. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01573

74. Kumar S. Burnout and doctors: prevalence, prevention and intervention. Healthcare. (2016) 4:37. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030037

75. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, Lewith G, Kontopantelis E, Chew-Graham C, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. (2017) 177:195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674

76. Kawanishi C. Designing and operating a comprehensive mental health management system to support faculty at a university that contains a medical school and university hospital. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. (2016) 118:28–33.

77. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, Call TG, Davidson JH, Multari A, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. (2014) 174:527–33. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387

78. Quirk H, Crank H, Carter A, Leahy H, Copeland RJ. Barriers and facilitators to implementing workplace health and wellbeing services in the NHS from the perspective of senior leaders and wellbeing practitioners: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6283-y

79. Johnson JV, Hall EM, Ford DE, Mead LA, Levine DM, Wang NY, et al. The psychosocial work environment of physicians: the impact of demands and resources on job dissatisfaction and psychiatric distress in a longitudinal study of Johns Hopkins Medical School graduates. J Occup Environ Med. (1995) 37:1151–9. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199509000-00018

80. Zhang X, Jiang Y, Yu H, Jiang Y, Guan Q, Zhao W, et al. Psychological and occupational impact on healthcare workers and its associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. (2021) 94:1441–53. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01657-3

81. Laschinger HKS, Finegan J, Shamian J, Almost J. Testing Karasek's demands-control model in restructured healthcare settings: effects of job strain on staff nurses' quality of work life. J Nurs Adm. (2001) 31:233–43. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200105000-00003

82. Laschinger HKS, Finegan J, Shamian J, Wilk P. Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings: Expanding Kanter's model. J Nurs Adm. (2001) 31:260–72. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200105000-00006

83. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. (2017) 92:129–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

84. Shauman K, Howell LP, Paterniti DA, Beckett LA, Villablanca AC. Barriers to career flexibility in academic medicine: a qualitative analysis of reasons for the underutilization of family-friendly policies, and implications for institutional change and department chair leadership. Acad Med. (2018) 93:246–55. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001877

85. Oleschuk M. Gender equity considerations for tenure and promotion during COVID-19. Can Rev Sociol. (2020) 57:502–15. doi: 10.1111/cars.12295

86. Antecol H, Bedard K, Stearns J, Benyammi S, Lee C, Dominguez Rodriguez J, et al. Equal but inequitable: who benefits from gender-neutral tenure clock stopping policies? Am Econ Rev. (2018) 108:2420–41. doi: 10.1257/aer.20160613

87. Drolet BC, Rodgers S. A comprehensive medical student wellness program-design and implementation at Vanderbilt School of Medicine. Acad Med. (2010) 85:103–10. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c46963

88. Royal K, Flammer K, Borst L, Huckle J, Barter H, Neel J. A comprehensive wellness program for veterinary medical education: design and implementation at North Carolina State University. Int J High Educ. (2016) 6:74–83. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v6n1p74

89. Hamric AB, Epstein EG. A health system-wide moral distress consultation service: development and evaluation. HEC Forum. (2017) 29:127–43. doi: 10.1007/s10730-016-9315-y

90. Duchek S. Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Bus Res. (2020) 13:215–46. doi: 10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

91. Will P. Hybrid Working May Change Our Workplace Social Networks. What Does It Mean for Inclusion? (2021). Available online at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/ (accesssed April 21, 2021).

92. Huang LV, Liu PL. Ties that work: investigating the relationships among coworker connections, work-related Facebook utility, online social capital, and employee outcomes. Comput Hum Behav. (2017) 72:512–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.054

Keywords: psychosocial work demands, veterinary well-being, COVID-19, academia well-being, mental health, stress

Citation: McKee H, Gohar B, Appleby R, Nowrouzi-Kia B, Hagen BNM and Jones-Bitton A (2021) High Psychosocial Work Demands, Decreased Well-Being, and Perceived Well-Being Needs Within Veterinary Academia During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Vet. Sci. 8:746716. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.746716

Received: 24 July 2021; Accepted: 17 September 2021;

Published: 18 October 2021.

Edited by:

Marta Hernandez-Jover, Charles Sturt University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Jennifer Manyweathers, Charles Sturt University, AustraliaKimberly Ann Carney, Lincoln Memorial University, United States

Copyright © 2021 McKee, Gohar, Appleby, Nowrouzi-Kia, Hagen and Jones-Bitton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hayley McKee, aGF5bGV5bWNrZWVlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Hayley McKee

Hayley McKee Basem Gohar

Basem Gohar Ryan Appleby4

Ryan Appleby4 Behdin Nowrouzi-Kia

Behdin Nowrouzi-Kia Andria Jones-Bitton

Andria Jones-Bitton