94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Trop. Dis. , 14 February 2025

Sec. Disease Prevention and Control Policy

Volume 6 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2025.1475955

This article is part of the Research Topic Preventing and Controlling Tropical Infectious Diseases: Lessons from the Global South View all 5 articles

Introduction: Millions globally suffer from neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and mental health conditions concurrently. Those with NTDs face heightened risks of mental health issues, and those with mental health conditions are more vulnerable to NTDs. Family caregivers of patients with both conditions often face significant burdens but are frequently overlooked as "hidden patients." Research on this issue is limited in Ethiopia.

Objective: This study explores the burdens and coping mechanisms of family caregivers for patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness in Southern Ethiopia.

Methods: This qualitative phenomenological study engaged seventeen family caregivers of individuals with comorbid NTDs and mental illness. Participants were purposively selected to ensure the inclusion of individuals with rich, relevant experiences capable of providing profound insights into the phenomenon under study. To capture the in-depth experiences and perspectives of caregivers, semi-structured interviews were conducted in participants' homes or compound rooms, ensuring privacy and the prior acquisition of informed consent for audio-recording. The interviews were designed to provide a comfortable, natural setting conducive to open discussion. Transcripts were initially transcribed in Amharic and then translated into English, with each translation cross-verified against the original audio recordings to ensure accuracy. Data analysis followed an inductive thematic approach, allowing for themes and sub-themes to emerge organically from the data through multiple coding and validation cycles.

Results: Caregivers faced significant burdens in four main areas: physical, social, psychological, and economic. Physically, they undertook demanding tasks like bathing and feeding, leading to strain and health issues. Socially, they experienced isolation and stigma, impacting family contact and community participation. Psychologically, caregivers reported high stress, anxiety, and depression, compounded by managing both chronic conditions and societal stigma. Economically, they endured financial strain, including job loss or reduced working hours. Coping mechanisms included strong social support from family, friends, and community organizations, problem-solving techniques, self-care practices, and seeking emotional support.

Conclusion: Caregivers of patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness in Southern Ethiopia experience substantial burdens across multiple dimensions. Effective coping mechanisms and robust social support are vital for alleviating these challenges and improving caregivers' well-being.

The interplay between mental health conditions and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) represents a crucial but under-researched area of global health. The prevalence of NTDs and mental health disorders is alarmingly high, with nearly one billion people affected by NTDs and 1.1 billion by mental health conditions worldwide (1, 2). These conditions are not only widespread but are also on the rise, exacerbated by factors such as poverty, which disproportionately affects those in low-resource settings like Ethiopia (2, 3).

Ethiopia is particularly impacted, with over 75 million people at risk of at least one NTD (3). The country also faces a significant burden of mental health conditions, which are among the leading causes of non-communicable disease burden (1). The coexistence of NTDs and mental health disorders complicates patient care and contributes to a cycle of disadvantage and poor health outcomes. This intersection of conditions remains underexplored, despite its profound impact on affected individuals and their families.

Neglected tropical diseases and mental health conditions are interrelated in complex ways. Individuals with NTDs often experience increased risks of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, due to the chronic pain, disability, and social stigma associated with these diseases (4, 5). Conversely, those with existing mental health conditions are more vulnerable to contracting NTDs, partly due to reduced health-seeking behaviors and poorer health management (4, 5). The stigma surrounding both NTDs and mental health conditions compounds the problem, leading to severe social exclusion, reduced quality of life, and increased health care needs (6, 7). The COVID-19 pandemic further illustrates the interplay between infectious diseases and mental health, where individuals faced heightened psychological distress and exacerbated vulnerabilities, underscoring the need for integrated care approaches (8).

Research highlights that individuals suffering from comorbid NTDs and mental health conditions experience heightened levels of depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicidal ideation compared to those with other chronic conditions (1, 7, 9). These issues are exacerbated by the stigma attached to both NTDs and mental health disorders, which can lead to discrimination and social isolation, further worsening the individuals' physical and psychological well-being (4, 10). Economic hardship is another significant factor, as individuals and families often face increased financial burdens due to the costs of managing chronic conditions and potential loss of employment (4).

Despite the critical nature of these issues, there is a notable lack of research focusing specifically on the challenges faced by caregivers of individuals with comorbid NTDs and mental health conditions, particularly in the Ethiopian context. Most existing studies address NTDs or mental health conditions in isolation, leaving a gap in understanding the unique experiences and needs of caregivers managing both (11, 12). In low-resource settings like Southern Ethiopia, where healthcare infrastructure is limited and mental health services are often inadequate, the burden on caregivers is particularly severe (13). Caregivers in these settings frequently face substantial challenges due to inadequate support systems and resources.

Family caregivers play a pivotal role in managing the health and well-being of individuals with comorbid NTDs and mental health conditions. They are often responsible for providing essential care, including administering medications, managing personal hygiene, and offering emotional and financial support (12). However, the demands placed on these caregivers can be overwhelming, and their needs and coping strategies are not well-documented (5). The lack of targeted support and understanding exacerbates their burden, potentially leading to caregiver burnout and reduced quality of care for patients (12).

Exploring caregiver burdens and coping mechanisms for patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness requires a deep understanding of the social, cultural, and emotional dimensions of caregiving (14). A qualitative approach is uniquely suited to uncovering these complexities, as it enables the exploration of caregivers' lived experiences, perceptions, and adaptive strategies in their specific contexts (15). Unlike quantitative methods, qualitative research provides rich, nuanced insights into the challenges faced by caregivers, including the stigma, emotional distress, and resource limitations they encounter (16). This approach also captures the dynamic interplay between caregiving responsibilities and the broader socio-economic and cultural factors that shape caregiving practices (4). By adopting a qualitative lens, this study aims to offer a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted burdens caregivers face and inform context-sensitive interventions to support them effectively.

This study aims to address these gaps by exploring the specific burdens faced by family caregivers of individuals with comorbid NTDs and mental health conditions in Southern Ethiopia. It seeks to identify the coping strategies employed by these caregivers and the challenges they encounter in managing their dual responsibilities. By shedding light on these issues, the study aims to inform policy and practice, leading to improved support for caregivers and better health outcomes for individuals affected by both NTDs and mental health conditions (17, 18).

Understanding the experiences and needs of caregivers is crucial for developing effective interventions and support systems. This study will contribute valuable insights into the caregiving experience in a low-resource context and provide evidence for strategies to enhance caregiver support, ultimately improving the overall health and well-being of affected individuals and their families.

This qualitative phenomenological study was conducted in the Southern Ethiopia Regional State, specifically in the Sodo Zuria, Boreda, and South Ari districts. These districts were selected due to their high prevalence of endemic NTDs. According to the 2021 academic reports from the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region (SNNPR), these districts are recognized as significant hotspots for NTDs, making them particularly relevant for exploring the experiences of family caregivers managing individuals with comorbid NTDs and mental illness (19).

The research was carried out in two distinct phases: the first phase occurred from January to February 2024, and the second phase took place from June to July 2024. This phased approach was strategically designed to capture potential seasonal variations in caregiving experiences and challenges, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of caregivers' coping strategies within the dynamic socio-cultural and healthcare contexts of Southern Ethiopia.

The study employed a qualitative phenomenological design to explore the lived experiences of family caregivers of individuals with comorbid mental illness and NTDs. Phenomenological research is well-suited to investigate and describe the essence of caregivers' experiences and the meaning they ascribe to their caregiving roles (1). This approach allowed for an in-depth exploration of the caregiving experience and the complexities involved in managing both chronic physical and mental health conditions.

The target population for this study included family caregivers of individuals with comorbid mental illness and NTDs residing in the specified study areas. These caregivers were directly involved in the day-to-day care of affected individuals.

Participants were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were 18 years or older and self-reported as family caregivers providing direct, unpaid care to individuals with both mental illness and NTDs. Additionally, participants were required to have been providing care for a minimum of six months. Exclusion criteria included individuals who were not family members or who were providing paid care to someone with both mental illness and NTDs.

The study focused on three purposively selected districts: Sodo Zuria, Boreda, and South Ari. These districts were chosen due to their high prevalence of endemic NTDs, as identified in the SNNPR 2021 academic reports. The selection aimed to ensure representation of areas heavily affected by NTDs and where caregivers' experiences could be adequately captured.

A homogeneous purposive sampling technique was employed to select participants with extensive knowledge and firsthand experience of caregiving for individuals with comorbid mental illness and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). Participants were considered "information-rich" based on their unique and in-depth understanding of the caregiving experience. The sampling process was facilitated by health extension workers and local volunteers, who assisted in identifying and recruiting eligible candidates. Selection criteria included relevant caregiving experience, willingness to participate, and demographic diversity, including factors such as gender, age, and socioeconomic status, which were recorded to explore their potential influence on caregiving experiences. This approach ensured a comprehensive representation of the caregiving context and enhanced the richness of the data collected.

The sample size for this study was determined using the principle of data saturation, a key concept in qualitative research. Data saturation is reached when no new themes, insights, or information emerge from continued data collection, signaling that the sample has sufficiently captured the full range of relevant perspectives. This approach ensures that the study provides deep, rich insights while maintaining methodological rigor.

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to select seventeen family caregivers of individuals with comorbid neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and mental illnesses. Participants were chosen from diverse socio-economic and cultural backgrounds to provide a comprehensive understanding of their caregiving experiences and coping mechanisms. Recruitment continued until saturation was achieved, which was defined as the point at which no new themes, codes, or insights emerged from the data, and redundancy was observed across multiple rounds of analysis. At this point, it was clear that the sample size was sufficient for capturing the full range of caregiving experiences. This process ensured a thorough exploration of the caregiving experience and a nuanced understanding of the coping strategies employed by the participants.

An interview guide was developed in English, reviewed against existing literature, and translated into Amharic. The guide was pretested with caregivers not involved in the study, leading to revisions to improve clarity and effectiveness. Semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted using this guide, which featured open-ended questions and space for field notes to capture detailed responses. Interviews were conducted face-to-face in Amharic at participants’ homes or private spaces to ensure privacy and comfort. Data collection was carried out by the principal investigator and two trained research assistants. Probing techniques were used to deepen understanding and clarify responses, with all interviews recorded with participants' consent.

Data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s seven-step phenomenological analysis method (20). Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim in Amharic and then translated into English, with translations verified against the original recordings. An inductive thematic analysis approach was used, allowing themes and sub-themes to emerge naturally from the data. Two researchers were involved in coding, categorizing, and theming, with verification by additional investigators. The iterative process included repeated readings and reviews of transcripts and recordings to ensure alignment with participants' statements. Themes were illustrated with direct quotations from participants, and data coding and management were facilitated using Open Code Software Version 4.03.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences at Arba Minch University on June 19, 2023 (project reference number: IRB/482/2023). Prior to fieldwork, verbal permissions were obtained from relevant authorities and local village heads or mayors. Participants were informed about the study’s purpose, risks, benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained through signatures or thumbprints. Privacy and confidentiality were ensured, with data used solely for research purposes and not disclosed outside the research team. All methods adhered to the Helsinki Declaration guidelines.

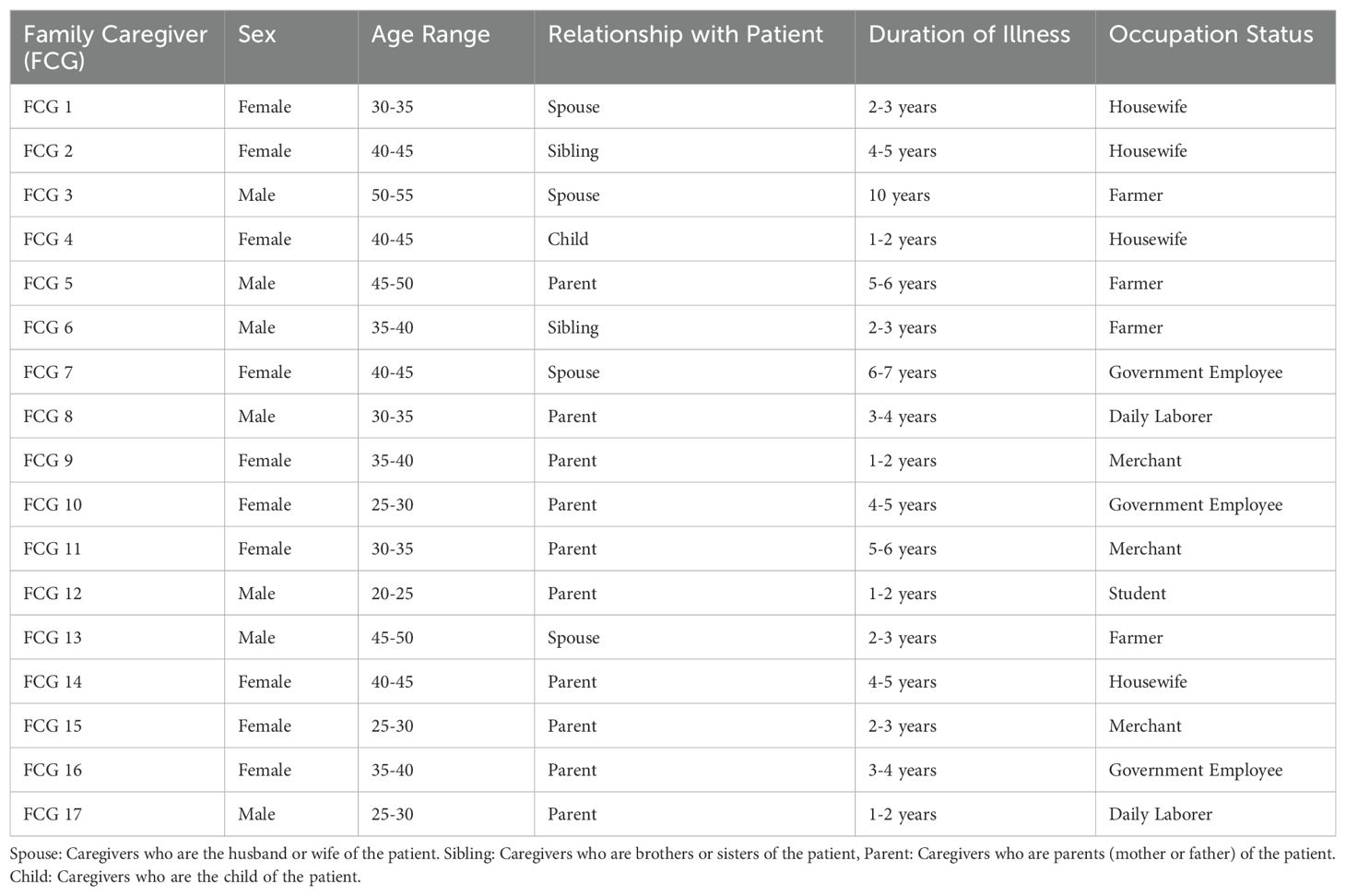

The study involved 17 family caregivers (FCGs) providing care for patients with comorbid neglected tropical diseases and mental illnesses in Southern Ethiopia. Among the participants, 10 were female (59%) and 7 were male (41%), with ages ranging from 24 to 53 years and an average age of 38.5 years. Their relationships to the patients varied: 3 were husbands (18%), 2 were brothers (12%), 2 were wives (12%), 1 was a child (6%), 6 were mothers (35%), and 3 were fathers (18%). The duration of the patients' illnesses ranged from 1 to 10 years, with an average duration of 4.2 years. The caregivers' occupations were diverse, including 5 housewives (29%), 4 farmers (24%), 3 government employees (18%), 2 daily laborers (12%), 3 merchants (18%), and 1 student (6%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of caregivers for patients with neglected tropical diseases and mental illness comorbidity in Southern Ethiopia, 2024.

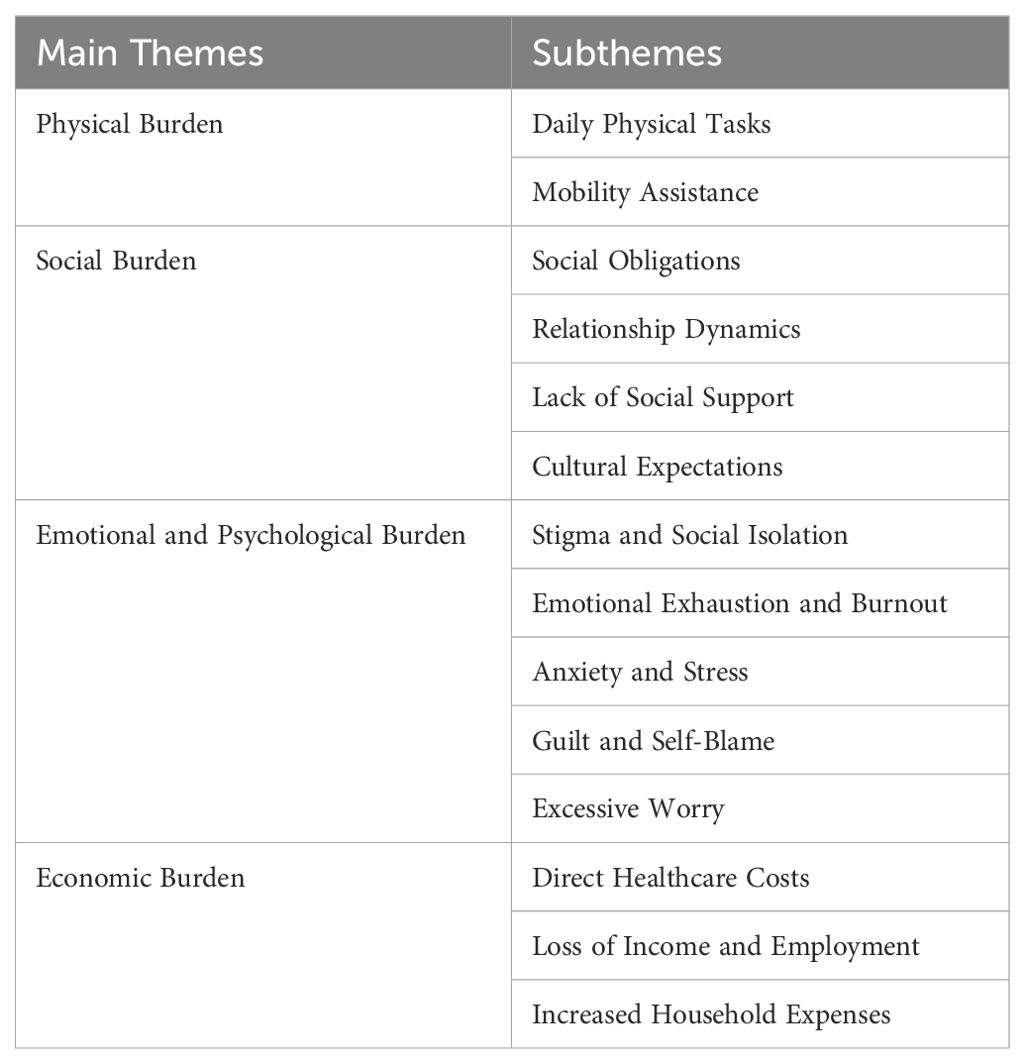

The burdens encountered by family caregivers of individuals with comorbid NTDs and mental illness were categorized into four main themes and fourteen subthemes, as outlined in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Burdens encountered by family caregivers for patients with neglected tropical diseases and mental illness comorbidity in Southern Ethiopia, 2024.

Caregivers often experience significant physical burdens as they manage the daily needs of their mentally ill relatives. The physical demands of caregiving can lead to chronic fatigue, physical exhaustion, and various health issues. These physical challenges are compounded by the lack of respite and support, making it difficult for caregivers to maintain their own health and well-being. Under this theme, we explore the substantial and multifaceted physical challenges faced by caregivers of individuals with NTDs and mental illness comorbidity. The findings highlight that caregivers often undertake diverse physical tasks to meet their loved ones' daily needs and medical care, which can have serious impacts on their own health and well-being. Caregivers of patients with NTDs and mental illness are responsible for assisting with essential activities, including bathing, dressing, feeding, and toileting. They also provide physical support, such as helping patients move around the house, using mobility aids, or accompanying them to medical appointments. These tasks can be particularly physically demanding, especially if the patient has mobility issues or requires lifting and transferring. These burdens, experienced by caregivers while caring for their relatives, are summarized in two subthemes:

The daily physical tasks involved in caregiving are extensive and demanding, often consuming significant portions of caregivers' time and energy. As illustrated by the caregivers' experiences, these responsibilities include assisting with essential activities such as bathing, dressing, meal preparation, and feeding. For instance, one caregiver shared, “Every day, I bathe him, dress him, prepare his meals, feed him, and assist him with everything he needs. This daily caregiving routine has become a significant part of my life; I know he depends on me for these basic needs.” [FCG 15]. Another caregiver emphasized the physical toll of these tasks: “I am constantly lifting and moving my mother, helping her with daily activities like bathing and dressing. This physical strain has affected my body, causing chronic back pain and fatigue.” [FCG 17].

Providing mobility assistance is a critical aspect of caregiving that involves constant physical effort and vigilance. Caregivers often find themselves assisting their loved ones with every step, ensuring their safety and comfort. One participant shared, “She cannot move around on her own, so I am constantly by her side to assist with every step. From helping her get out of bed in the morning to aiding her as she moves around the house throughout the day, I ensure she is safe and comfortable at all times. My presence provides her with the stability and support she needs, enabling her to maintain as much independence as possible despite her mobility challenges.” [FCG 9]. Another caregiver noted, “The physical demands of caring for my mother are overwhelming. I am always on my feet, with little time for rest. This has led to severe fatigue and health problems.” [FCG 5]. The lack of rest and continuous alertness further exacerbates these challenges, as illustrated by a caregiver who said, “I hardly get any sleep because I have to be awake all night in case my father needs help. The lack of rest is affecting my physical health and my ability to care for him effectively.” [FCG 11].

Caregivers of patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness in Southern Ethiopia face profound and multifaceted social burdens. These burdens, experienced by caregivers while caring for their relatives, can be categorized into four subthemes: social obligations, relationship dynamics, lack of social support, and cultural expectations.

Social obligations refer to the duties that caregivers feel compelled to fulfill due to societal, cultural, or family expectations. These obligations can significantly increase their stress and workload. Caregivers often face challenges in balancing family responsibilities with these obligations. Caring for a sick family member can limit their time with other relatives, leading to feelings of neglect and emotional stress among children and other family members. Additionally, the demands of caregiving can prevent them from participating in community events or attending to other familial duties, further compounding their burden. A mother caring for her child shared, “Due to the burden of being a caregiver, I lost my social life. Caring for individuals with mental health problems is especially challenging because of the behaviors they exhibit.” [FCG 4]. A woman who is caring for her mother explained, “The demands of caregiving have significantly reduced the time I can spend with my family, leading to feelings of neglect among my children. It also challenges my ability to fulfill other family responsibilities, compounding my overall burden.” [FCG 11]. A man caring for his mother remarked, “Balancing family responsibilities and social obligations as a caregiver is incredibly challenging. The demands of caregiving often mean I have little time for other family members, leading to feelings of neglect and emotional stress among my children and relatives.” [FCG 5]. A woman caring for her father stated, “Due to the demands of caregiving, I find it difficult to participate in community events or attend to other familial duties, which further increases my workload and stress.” [FCG 16].

Findings from the qualitative interviews revealed that caregiving for patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness significantly impacts family dynamics and relationships. The caregiving role often alters the caregiver's interactions with other family members, affecting both the quality of relationships and the overall family functioning. Some caregivers reported strained relationships with their spouses, children, and other relatives as a result of their caregiving responsibilities. One caregiver described the impact on her relationship with her spouse: “My husband and I are constantly arguing because he feels I am neglecting him and our children. The time and energy I spend on caregiving have caused a rift between us, and this conflict adds to my stress.” [FCG 7]. Another caregiver expressed concerns about her children: “My children feel neglected because I am so focused on taking care of their father. They complain that I don't have time for them anymore, and this creates tension and emotional strain within our family.” [FCG 11]. The caregiving role also affects caregivers' relationships with extended family and friends. A caregiver shared, “I have lost touch with many of my friends because I can no longer participate in social activities. My family also feels isolated because I can't visit them as often as I used to.” [FCG 9].

The lack of social support is a significant burden for caregivers. Many reported feeling isolated and unsupported, both emotionally and practically. The absence of a strong support network exacerbates their stress and feelings of burnout. One caregiver mentioned, “I feel like I am alone in this. There is no one to help me with the caregiving tasks or provide emotional support. This isolation is overwhelming and adds to my stress.” [FCG 15]. Another caregiver shared, “The lack of support from extended family and community makes it even harder. I have no one to turn to for help or advice, and this makes the caregiving experience even more difficult.” [FCG 5].

Cultural expectations also play a role in shaping caregivers' experiences. In many cases, cultural norms dictate that caregiving is primarily the responsibility of family members, often placing additional pressure on caregivers. One participant explained, “In our culture, it is expected that family members take care of their sick relatives, and there is little external support. This cultural expectation adds to my burden because I feel obligated to handle everything on my own.” [FCG 6]. Another caregiver noted, “Cultural beliefs about mental illness and NTDs often lead to stigma and social isolation. I feel judged by others, which makes it even harder to cope with the caregiving demands.” [FCG 12].

Caregivers of patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness experience substantial emotional and psychological burdens. These burdens can include stigma, social isolation, emotional exhaustion, anxiety, stress, guilt, and excessive worry. The emotional and psychological challenges faced by caregivers are significant, affecting their overall well-being and ability to provide care effectively. These burdens are categorized into five subthemes:

Stigma and social isolation are significant issues for caregivers, who often face negative societal attitudes and feelings of being marginalized. Caregivers frequently report feeling judged and isolated due to the mental illness or NTD of their loved one. One caregiver shared, “The stigma surrounding mental illness makes it hard for me to seek help or talk about my struggles. I feel like people judge me and my family, which only adds to my isolation and stress.” [FCG 8]. Another participant noted, “I am often left alone in my struggles because others do not understand the challenges of caregiving for someone with both an NTD and mental illness. This isolation is emotionally draining.” [FCG 13].

Emotional exhaustion and burnout are common among caregivers, resulting from the continuous demands of caregiving and the lack of respite. Many caregivers experience feelings of being overwhelmed, drained, and unable to cope with the ongoing stress. A caregiver expressed, “I feel emotionally exhausted from the constant demands of caregiving. It seems like there is no end to the stress and responsibilities, and this burnout is affecting my health and well-being.” [FCG 17]. Another caregiver described the toll on her mental health: “The emotional burden of caring for a loved one with both an NTD and mental illness has left me feeling drained and hopeless. I often feel overwhelmed by the relentless stress and responsibilities.” [FCG 15].

Anxiety and stress are prevalent among caregivers, driven by the challenges of managing complex health needs and coping with the uncertainty of their loved one’s condition. One caregiver noted, “I am constantly anxious about my husband's health and the future. The stress of managing his care and the fear of what might happen next keeps me awake at night.” [FCG 9]. Another participant remarked, “The uncertainty and constant worry about my mother's condition contribute to my high levels of stress and anxiety. It feels like there is no relief from these overwhelming emotions.” [FCG 11].

Guilt and self-blame are common emotional responses among caregivers, who often feel they are not doing enough or are failing in their caregiving roles. This guilt can be exacerbated by societal expectations and personal standards. A caregiver shared, “I constantly feel guilty for not being able to do more for my brother. I blame myself for not being able to provide the care he needs or for not being able to balance my responsibilities better.” [FCG 14]. Another participant expressed, “I often feel like I am not doing enough for my wife and that I am failing in my caregiving role. This guilt and self-blame weigh heavily on me.” [FCG 10].

Excessive worry about the well-being of the patient and the impact of their condition on the caregiver's life is another significant emotional burden. Caregivers frequently express concern about their loved one's health and the future. One caregiver noted, “I am always worried about my father's condition and how it will affect our lives. This constant worry is exhausting and adds to my stress.” [FCG 16]. Another participant shared, “The constant fear of something going wrong with my mother's health is overwhelming. My excessive worry makes it difficult for me to focus on anything else and contributes to my overall stress.” [FCG 17].

The economic burden of caregiving for patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness is significant, encompassing direct healthcare costs, loss of income, and increased household expenses. These financial challenges further compound the overall burden experienced by caregivers. The economic impacts are categorized into three subthemes:

Caregivers often face substantial direct healthcare costs related to the treatment and management of their loved one's conditions. These costs can include medical appointments, medications, and other health-related expenses. One caregiver shared, “The costs of my husband's medication and frequent doctor visits are overwhelming. We are struggling to manage these expenses, and it adds a lot of financial stress to our situation.” [FCG 7]. Another caregiver noted, “We have had to spend a significant amount of money on healthcare, which has strained our family's finances and caused additional stress.” [FCG 12].

The need for full-time caregiving often leads to a loss of income and employment opportunities for caregivers. Many report having to reduce work hours or leave their jobs entirely to provide care. A caregiver explained, “I had to quit my job to take care of my wife, which has resulted in a significant loss of income. This financial strain makes it even harder to manage our household expenses.” [FCG 6]. Another participant shared, “The time I spend caregiving has affected my ability to work, leading to a loss of income and financial instability for our family.” [FCG 11].

Increased household expenses related to caregiving also contribute to the economic burden. Caregivers often face additional costs for items such as special equipment, home modifications, or extra caregiving support. One caregiver shared, “The additional costs for home modifications and special equipment to accommodate my father's needs have put a strain on our budget. We are struggling to cover these extra expenses.” [FCG 14]. Another participant noted, “The increased costs of caregiving have added to our financial difficulties, making it challenging to manage both daily living expenses and the additional expenses related to my mother's care.” [FCG 13].

This study provides a comprehensive examination of the diverse burdens and coping strategies experienced by family caregivers of patients with comorbid neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and mental illness in Southern Ethiopia. The findings reveal that caregivers face multifaceted challenges spanning physical, social, psychological, and economic domains. Despite these significant burdens, caregivers utilize various coping mechanisms, notably strong social support networks and self-care practices.

Our study highlights the substantial physical demands of caregiving, which include tasks such as bathing, dressing, feeding, and assisting with mobility. These responsibilities often lead to considerable physical strain and health issues for caregivers themselves. This observation aligns with existing literature that underscores the physical toll of caregiving (17, 18). It is imperative to develop targeted interventions to alleviate this burden, such as training programs on proper caregiving techniques, access to respite care, and the provision of assistive devices like hoists or transfer boards (21). Regular health check-ups and support services from healthcare systems are also essential to maintain caregivers' health and effectiveness (22).

Socially, caregivers encounter reduced family contact and societal stigma, which contribute to social isolation and difficulties in participating in community activities. This isolation can exacerbate feelings of loneliness and stress, consistent with findings from other studies on caregiver burden (23). To combat social isolation, targeted interventions are necessary to reduce stigma and enhance social inclusion. Community-based programs that promote social interaction and support networks are vital in alleviating loneliness and stress (24). Public awareness campaigns can educate communities about the caregiving role and its challenges, thereby reducing stigma and fostering a supportive environment (25). Additionally, healthcare providers should facilitate connections between caregivers and local support groups to strengthen their social networks and resilience (26).

Psychologically, caregivers in our study reported high levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and emotional exhaustion. These findings are consistent with the literature, which highlights the profound impact of caregiving on mental health, particularly when managing chronic conditions (2, 18). The dual burden of NTDs and mental health conditions, coupled with societal stigma, intensifies these psychological challenges. This dual burden increases emotional strain and amplifies feelings of inadequacy and helplessness. Therefore, targeted mental health support and efforts to reduce stigma are crucial to mitigating the psychological toll on caregivers and enhancing their overall well-being (3, 27).

Economically, caregivers face significant financial hardships due to reduced working hours or job loss and additional costs associated with managing chronic conditions. These findings are consistent with previous research highlighting the financial difficulties of caregiving (28, 29). To address these economic challenges, policymakers and healthcare providers should consider implementing financial assistance programs, such as subsidies or tax relief, to help offset caregiving and medical expenses. Reviewing workplace policies to offer flexible working hours or job protection for caregivers could also alleviate financial strain (30). Additionally, providing resources for financial planning tailored to caregivers would be beneficial. Addressing these economic challenges is critical for reducing caregivers' financial burden and enhancing their ability to provide high-quality care.

The findings of this study underscore the urgent need for increased awareness and the development of targeted interventions to support caregivers facing these multifaceted challenges. Effective coping mechanisms, including robust social support networks, problem-solving strategies, self-care practices, and emotional support from peers and professionals, are crucial in mitigating the identified burdens. Strengthening these coping mechanisms through tailored interventions could significantly enhance caregivers' overall well-being. Practically, healthcare providers should recognize the pivotal role of family caregivers and integrate support services designed to address their needs. This includes offering resources and training to bolster caregivers' coping skills and connecting them with relevant support networks. From a policy perspective, comprehensive policies that provide financial assistance and access to mental health services for caregivers are essential. Implementing such policies can address the economic and psychological challenges highlighted in this study, ultimately improving the support available to those managing the care of individuals with chronic conditions.

This study presents several strengths, offering a nuanced understanding of the burdens and coping mechanisms experienced by family caregivers of patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness in Southern Ethiopia. A key strength is the qualitative approach, which provides rich, detailed insights into the specific challenges faced by caregivers and the strategies they employ. By exploring the physical, social, psychological, and economic aspects of caregiving, the study captures the multifaceted nature of the caregiving experience, providing a holistic perspective essential for developing targeted support interventions. The context-specific nature of the research also offers valuable local insights that can guide the development of tailored interventions for caregivers in this region. Identifying effective coping strategies, such as strong social support networks and self-care practices, further enhances our understanding of how caregivers manage their responsibilities and highlights areas where support can be improved.

However, the study also has limitations. The qualitative nature of the research, while offering in-depth perspectives, limits the generalizability of the findings. The experiences of the participants may not fully represent those of the broader caregiver population in Ethiopia or other contexts. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, as participants might underreport or overreport their experiences, which could affect the accuracy of the findings. The sample size and selection process further constrain the representativeness of the results, potentially influencing their applicability to all caregivers in the region. Moreover, the cross-sectional design provides only a snapshot of caregiver experiences at a specific point in time. Longitudinal studies would offer a more comprehensive understanding of how caregiver burdens and coping strategies evolve over time.

Based on the findings of this study, several key recommendations are proposed to enhance support for family caregivers of patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illnesses in Southern Ethiopia. First, healthcare providers and policymakers should develop targeted support programs that address the multifaceted burdens faced by family caregivers. These programs should include practical assistance, such as caregiver training on effective caregiving techniques, access to caregiver relief services, and the provision of tools and resources to facilitate caregiving tasks.

Strengthening social support networks is also crucial. Community-based initiatives should be established to reduce the social isolation experienced by caregivers. Public awareness campaigns can play a significant role in decreasing stigma and promoting social inclusion, while healthcare systems should actively connect caregivers with local support groups to enhance their social connections.

Additionally, there is an urgent need to strengthen mental health support for caregivers dealing with stress, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion. This can be achieved by offering counseling services, support groups, and mental health resources specifically designed to meet the unique needs of family caregivers. Equally important is addressing the economic challenges they face by introducing financial assistance initiatives and implementing flexible workplace policies, such as adjusted working hours and job protection, to ease their burden.

Finally, further research is essential to deepen understanding of caregiver burdens and coping mechanisms. Future studies should adopt longitudinal approaches to track the evolving challenges and strategies of caregivers over time. Additionally, research should evaluate the effectiveness of intervention strategies and support programs in improving both caregiver well-being and patient outcomes. These recommendations aim to provide holistic and sustainable support for family caregivers, ultimately enhancing the quality of care for patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illnesses.

Family caregivers of patients with comorbid NTDs and mental illness in Southern Ethiopia face significant multidimensional challenges, encompassing physical, psychological, social, and economic burdens. These include physical strain leading to health issues, social isolation, heightened stress, and financial hardship exacerbated by caregiving responsibilities. Despite these challenges, the study highlights the positive impact of coping mechanisms and social support in mitigating caregiver burdens and improving well-being.

To address these issues, there is a critical need for targeted interventions tailored to caregivers' unique circumstances. Such interventions should include financial support, accessible mental health services, and community-based programs to reduce stigma and foster social inclusion. By implementing these measures, the caregiving environment can be strengthened to better support caregivers, ensuring sustainable care for both caregivers and patients.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences at Arba Minch University (project reference number: IRB/482/2023). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the [individual(s) AND/OR minor(s)\' legal guardian/next of kin] for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (RSTMH) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the RSTMH 2022 Early Career Grant program. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, or publication decisions.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (RSTMH) and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) for their essential financial support. We also thank Arba Minch University for granting ethical approval and the Zonal Health Department for their logistical assistance throughout the study. Our deepest appreciation goes to the study participants, data collectors, and caregivers for their invaluable contributions to this research. Additionally, we acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) for refining the language and enhancing the clarity of this manuscript. It is important to note that no AI-generated content was involved in the data analysis, interpretation, or critical scientific reasoning.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) for refining the language and enhancing the clarity of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Bartlett J, Deribe K, Tamiru A, Amberbir T, Medhin G, Malik M, et al. Depression and disability in people with podoconiosis: a comparative cross-sectional study in rural northern Ethiopia. Int Health. (2016) 8:124–31. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv037

2. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. (2003) 18:250. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250

3. Sharma N, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. Gender differences in caregiving among family caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J Psychiatry. (2016) 6:7. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.7

4. World Health Organization. Mental health of people with neglected tropical diseases: towards a person-centred approach. Geneva, Switzerland. (2020).

5. Bailey F, Eaton J, Jidda M, van Brakel WH, Addiss DG, Molyneux DH. Neglected tropical diseases and mental health: progress, partnerships, and integration. Trends Parasitol. (2019) 35:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.11.001

6. Mousley E, Deribe K, Tamiru A, Tomczyk S, Hanlon C, Davey G. Mental distress and podoconiosis in Northern Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Int Health. (2015) 7:16–25. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihu043

7. Tora A, Mengiste A, Davey G, Semrau M. Community involvement in the care of persons affected by podoconiosis—a lesson for other skin NTDs. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2018) 3:87. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed3030087

8. Hamdan A, Eastaugh J, Snygg J, Naidu J, Alhaj I. Coping strategies used by healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic in Dubai: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Narra X. (2023) 1. doi: 10.52225/narrax.v1i1.71

9. Obindo J, Abdulmalik J, Nwefoh E, Agbir M, Nwoga C, Armiya’u A, et al. Prevalence of depression and associated clinical and socio-demographic factors in people living with lymphatic filariasis in Plateau State, Nigeria. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2017) 11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005567

10. Semrau M, Ali O, Deribe K, Mengiste A, Tesfaye A, Kinfe M, et al. EnDPoINT: protocol for an implementation research study to integrate a holistic package of physical health, mental health and psychosocial care for podoconiosis, lymphatic filariasis and leprosy into routine health services in Ethiopia. BMJ Open. (2020) 10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037675

11. Yitbarek K, Birhanu Z, Tucho GT, Anand S, Agenagnew L, Ahmed G. Barriers and facilitators for implementing mental health services into the Ethiopian Health Extension Program: a qualitative study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. (2021) 14:1199. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S298190

12. Ayalew M, Workicho A, Tesfaye E, Hailesilasie H, Abera M. Burden among caregivers of people with mental illness at Jimma University Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2019) 18:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12991-019-0233-7

13. Sharif L, Basri S, Alsahafi F, Altaylouni M, Albugumi S, Banakhar M, et al. An exploration of family caregiver experiences of burden and coping while caring for people with mental disorders in Saudi Arabia—a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6405. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176405

14. Daliri DB, Afaya A, Laari TT, Abagye N, Aninanya GA. Exploring the burden on family caregivers in providing care for their mentally ill relatives in the Upper East Region of Ghana. PloS Global Public Health. (2024) 4:e0003075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0003075

15. Picado A, Nogaro S, Cruz I, Biéler S, Ruckstuhl L, Bastow J, et al. Access to prompt diagnosis: the missing link in preventing mental health disorders associated with neglected tropical diseases. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2019) 13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007679

16. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

17. Hartley J, Bluebond-Langner M, Candy B, Downie J, Henderson EM. The physical health of caregivers of children with life-limiting conditions: a systematic review. Pediatrics. (2021) 148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-014423

18. Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2009) 11:217–28. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/hbrodaty

19. Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region (SNNPR). Acdamic years report. Hawassa, Ethiopia (2021).

20. Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med teacher. (2020) 42:846–54. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

21. Johnson K, Swinton P, Pavlova A, Cooper K. Manual patient handling in the healthcare setting: a scoping review. Physiotherapy. (2023) 120:60–77. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2023.06.003

22. Gitlin LN, Hauck WW, Dennis MP, Winter L. Maintenance of effects of the home environmental skill-building program for family caregivers and individuals with Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2005) 60:368–74. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.368

23. Xu L, Liu Y, He H, Fields NL, Ivey DL, Kan C. Caregiving intensity and caregiver burden among caregivers of people with dementia: the moderating roles of social support. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2021) 94:104334. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104334

24. Chappell NL, Funk LM. Social support, caregiving, and aging. Can J Aging. (2011) 30:355–70. doi: 10.1017/S0714980811000316

25. Nemcikova M, Katreniakova Z, Nagyova I. Social support, positive caregiving experience, and caregiver burden in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1104250. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1104250

26. Tough H, Brinkhof MW, Fekete C. Untangling the role of social relationships in the association between caregiver burden and caregiver health: an observational study exploring three coping models of the stress process paradigm. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1737. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14127-3

27. Altieri M, Santangelo G. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on caregivers of people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) 29:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.009

28. Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. (2014) 311:1052–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304

29. Gérain P, Zech E. Informal caregiver burnout? Development of a theoretical framework to understand the impact of caregiving. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:466359. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01748

Keywords: family caregivers, caregiver burden, coping mechanisms, neglected tropical diseases, mental iillness, comorbid conditions, qualitative study, Southern Ethiopia

Citation: Sidamo NB, Hebo SH, Kassahun AB and Endris BO (2025) Exploring family caregiver burdens and coping mechanisms for patients with comorbid neglected tropical diseases and mental illness in Southern Ethiopia: insights from qualitative findings. Front. Trop. Dis. 6:1475955. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2025.1475955

Received: 09 September 2024; Accepted: 27 January 2025;

Published: 14 February 2025.

Edited by:

Harapan Harapan, Syiah Kuala University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Sara Nooraeen, University of Pittsburgh, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Sidamo, Hebo, Kassahun and Endris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Negussie Boti Sidamo, SGFuZWhhbGlkQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; TmVndXNzaWUuYm90aUBhbXUuZWR1LmV0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.