- 1Department of Chemistry, Government College of Engineering, Keonjhar, Odisha, India

- 2College of Pharmacy, Cihan University-Erbil, Erbil, Iraq

- 3Department of Medical Biochemical Analysis, College of Health Technology, Cihan University-Erbil, Erbil, Iraq

- 4Department of Microbiology, Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences, Karimnagar, Telangana, India

- 5Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, and Global Health Academy, School of Epidemiology and Public Health, DattaMeghe Institute of Higher Education, Wardha, India

- 6South Asia Infant Feeding Research Network (SAIFRN), Division of Evidence Synthesis, Global Consortium of Public Health and Research, DattaMeghe Institute of Higher Education, Wardha, India

- 7Center for Global Health Research, Saveetha Medical College and Hospital, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, India

- 8Medical Laboratories Techniques Department, AL-Mustaqbal University, Hillah, Babil, Iraq

- 9School of Biotechnology, KIIT Deemed-to-be University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Introduction

Chinese surveillance systems have recorded rising respiratory illness cases in North China since mid-October 2023, especially among children (1). Beyond the northern part of China, the Chinese National Health Commission briefed through a press conference on 13 November 2023 about a nationwide spike in the cases of respiratory diseases that predominantly affected the children there. The Chinese authorities attribute this upsurge in respiratory illness among children to the arrival of the cold season in China and the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions (1, 2). Alongside the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), it could also be associated with known active pathogens like the influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (1). M. pneumonia and RSV are known to be more prevalent in children than in adults. It was noticed in a recently reported survey of the lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) incidences among children that occurrences did not significantly vary between the pre-pandemic and pandemic era. However, the study observed a significant increase (28%) in all-cause mortality during the pandemic era, compared pre-pandemic times, and a 16% rise in hospitalisation (3).

It is argued that the COVID-19 pandemic has irreversibly altered the epidemiology of the circulating microbes that were active in lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs). A major factor behind the extensive control of COVID-19 during the pandemic was the extensive use of alcohol-based sanitisers and disinfectants (4). Additionally, an excessively prevalent novel SARS-CoV-2 and its multiple variants could have played a significant biocontrol role by interfering with and replacing the influenza virus and RSV and others that were common and prevalent in pre-pandemic times. A shift in the prevailing human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) serotypes was noticed among the acute-respiratory-tract-infected (aRTI) infants in South Africa (5). Although the pandemic witnessed an increase in the prevalence of aRTIs caused by HPIV 3, a significant decline in HPIV 1, 2, and 4 incidences was observed. Thus, it was hypothesised that numerous healthcare intervention measures during the pandemic that allegedly positively benefitted individual immunity could have factored for their reduced prevalence and altered health effects (5). However, the reason behind the prevalence of a specific serotype is not well understood.

Significant variations in the prevailing RSV before and during the COVID-19 pandemic are suspected to be attributed to dysregulated immunity brought about by SARS-CoV-2 infection and a complex interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with the circulating RSV. It could have resulted in eliminating the RSV from the respiratory tract (6). Also, a fear of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the pandemic forced the civic population to seek immediate medical assistance, which could have prevented the prevalence of common RTI pathogens. A study among children in British Columbia, Canada, revealed that there was a decrease in RSV-induced infection and hospitalisation in 2020–2021 (the peak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic era). It identified an increase in RSV-induced infection and hospitalisation in 2022–2023, suspected to be due to the reduced prevalence of RSV during the pandemic and reduced natural immunity (7).

Clusters of undiagnosed pneumonia cases in children

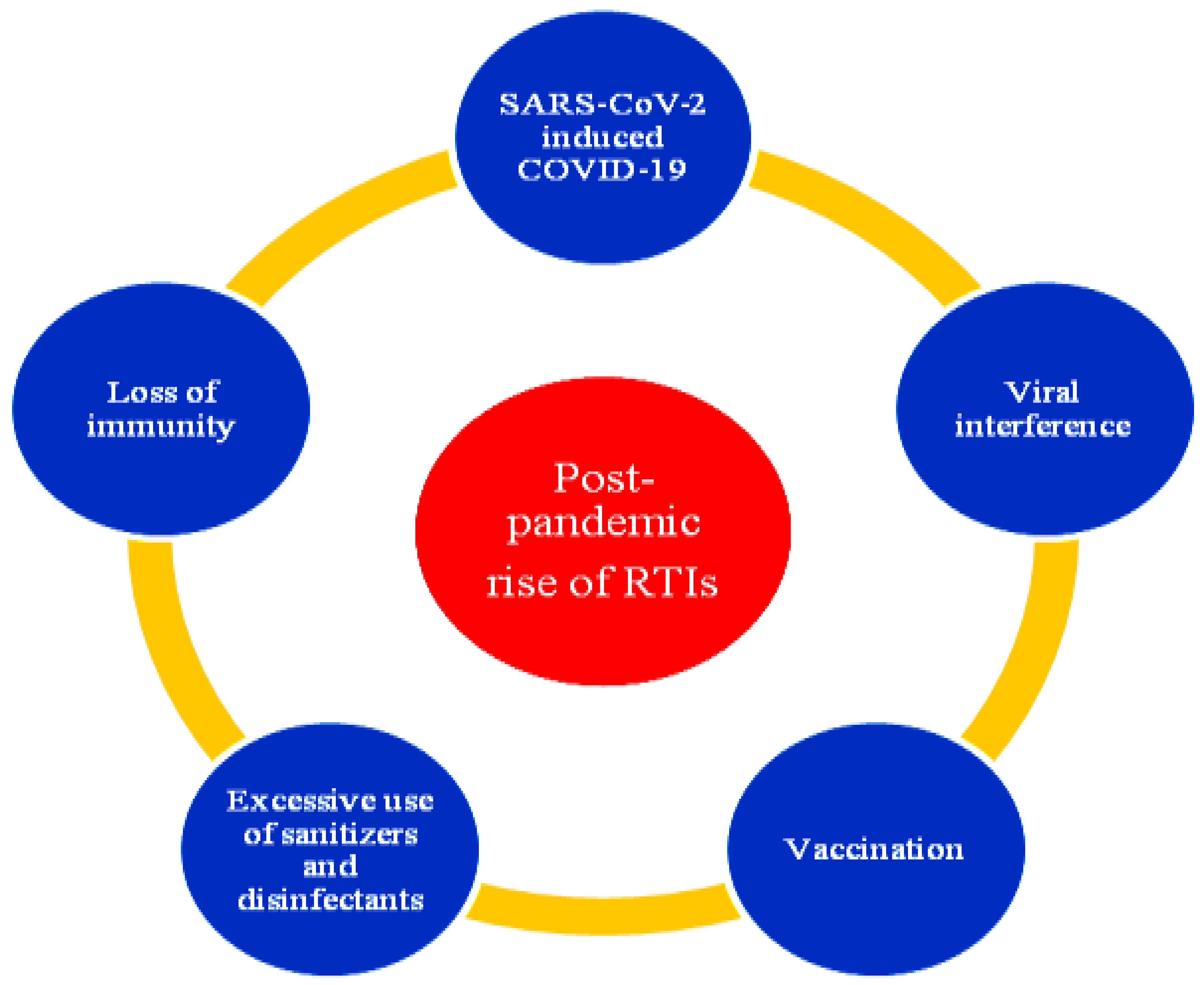

The World Health Organisation (WHO) identified clusters of undiagnosed pneumonia cases in children in several Chinese hospitals (1). It has officially requested China to provide detailed epidemiological and clinical information about these cases. Whether these ‘clusters of undiagnosed pneumonia’ cases in various Chinese regions were separate events or part of the known universal rise in respiratory illnesses within the community is yet not clear. The WHO recently engaged in teleconferencing with Chinese health agencies from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention and the Pediatric Hospital in Beijing (1). As per the data shared, the increasing outpatient consultations and hospitalisation of children was primarily attributed to Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia since May, and the adenovirus, RSV, and influenza virus since October in the reported year. M. pneumoniae, parainfluenza, and human rhinovirus predominated in September and October, and M. pneumoniae, influenza, and RSV predominated in November 2023, as per a recent surveillance (8). The factor behind the increasing respiratory illness cases in children in Northern China is allegedly the known pathogens (9), although the actual cause is uncertain. Other countries have also reported similar situations after the COVID-19 restrictions were eased there. A schema of the post-pandemic increase of RTIs and the possible associated factors is presented in Figure 1.

It is notable that no unusual or novel pathogens or unusual clinical symptoms were detected (2). The Chinese health authorities also did not report any altered disease presentation. The increase in respiratory illnesses was due to the circulating multiple known pathogens (9). It was stated that the rising cases did not overwhelm the patient load in hospitals. Considering the sudden upsurge of cases, enhanced outpatient and inpatient surveillance and monitoring for respiratory illness within the healthcare facility settings and the community was implemented covering a broad range of respiratory viruses and bacteria, including M. pneumonia (1). In addition to enhanced disease surveillance, revamping health system capacity and strengthening patient management are also recommended. Systems to capture information on the trends of influenza, influenza-like illness (ILI), pneumonia, RSV, SARS-CoV-2, and other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) is already in place in China, the report of which it could directly share with the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). Led by the WHO, GISRS is used for the virological and epidemiological surveillance of human influenza internationally. Close monitoring of the situation to identify and report unusual patterns is also highly recommended.

Discussion

It has been observed that the seasonal cycle of certain respiratory diseases and the prevalence of the responsible viruses were disturbed due to lockdown and restricted movements (10–13). It was evident from the negligible occurrence of RSV, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, and rhinovirus infections, which often peak during the winter. In contrast, an alarming increase in these infections during off season was attributable to the easing of restrictions and increased public movement. The COVID-19 trend greatly influenced the prevalence of non-SARS-CoV-2 respiratory viruses. Potentially, the COVID-19 virus eliminated the non-SARS-CoV-2 viruses or the cases went unreported, especially during the initial pandemic phases. These viruses supposedly reestablished, causing non-seasonal emergency situations and outbreaks as the pandemic receded.

The Chinese mainland recorded acute respiratory microbial infection outbreaks by RSV, influenza, and M. pneumoniae among children. It was attributed to the low immunity among the general population due to the strict lengthy lockdowns implemented by the Chinese government (14). Easing the restrictions suddenly exposed the public to the infections, causing outbreaks and necessitating hospitalisation. A similar trend was also noticed in the USA and the UK despite the milder COVID-19 restrictions there. This scenario of increasing cases in acute respiratory infections cases among children after the pandemic was attributed to the compromised functioning of the pulmonary system (15). A study confirmed significant (62 ± 19%; p=0.006) pulmonary dysfunction among COVID-19 recovered children who developed post-COVID-19 symptoms (60 ± 20%; p=0.003) compared with healthy and uninfected children (81 ± 6.1%). It is speculated that some exposed children did not develop the clinical manifestations and remained asymptomatic.

Despite the low impact of COVID-19 on children, research comparing the pre-pandemic (186; 41%) and post-pandemic (268; 59%) events suggested a significant increase in the occurrence of life-threatening events (ALTEs) or brief resolved unexplained events (BRUEs) (16). A Chinese study analysed the monthly trends of respiratory infections among children before and during the pandemic and noticed interesting trends in viral, bacterial, rare microbial, and viral-bacterial coinfections (17). It revealed that human rhinovirus (HRV) was consistently responsible for acute respiratory infections before and during the pandemic. Moraxellacatarrhalis and other bacterial pathogens like Streptococcus pneumoniae were evident before and during the pandemic. It was also observed that there was a significant increase in HRV, HPIV (type 1, and 3), human bocavirus (HboV), human coronavirus OC43 (HcoV-OC43), and human coronavirus HKU1 (HcoV-HKU1) infections during the pandemic compared with the pre-pandemic time. Conversely, a decreasing trend was noticed in bacterial (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, M. pneumoniae, group A streptococci and Haemophilus influenzae) and viral (human adenovirus and influenza A virus) infections during the COVID-19 pandemic, without any observed change in infection rates with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

In the current outbreak, the reported symptoms are typical of other respiratory diseases. Clinical manifestations as reported by the Chinese surveillance systems hint at known circulating pathogens. Paediatric pneumonia is primarily caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae, which is readily treated with antibiotics. However, full characterisation of the overall risk of the reported respiratory illness cases in children is challenging as the available data are limited. The respiratory infections and microbe prevalence that cause RTIs are season-influenced (18). Highly prevalent RSV, influenza virus, and common coronaviruses are expected during the winter. Temperature is a critical factor in the prevalence of HPIVs, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, and other viruses. Climatic conditions in the tropics favour influenza viruses so that they prevail throughout the year. There is a possibility of the prevalence of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the geographic regions where winter sets in, as suggested by reports submitted to the WHO’s FluNet (1). China may potentially see a significant increase in ILI caused by A(H3N2) and B/Victoria lineage viruses this winter, as opined by the National Influenza Centre, China.

The rate of detected respiratory pathogen cases was substantially high across all ages from September to November 2023, including in children, as compared with the number of cases in the same period during the 3 years before the COVID-19 pandemic (8). This may be due to the subsequent decline in immunity among the susceptible population that occurred due to relatively low infection rates in the period during the epidemic. Theoretically, the implemented COVID-19-appropriate measures during the pandemic might have amplified the effect. The mode of transmission is critical, and droplet and direct contact during the present situation has been reported, although airborne transmission is also suspected (file:///C:/Users/USER/Desktop/Children_china_1.pdf). Global M. pneumoniae surveillance suggested that the delayed M. pneumoniae epidemic re-emergence could be attributed to the introduction of better hygiene and sanitation practices (non-pharmaceutical intervention measures) against the COVID-19 virus (19). An increase in M. pneumoniae infections across all age groups was observed in several European countries during the winter of 2023, with increased cases being reported among adolescents and children (20). The study highlighted that some well-known common pathogens along with the novel respiratory pathogens could significantly strain the healthcare system, especially in megacities that are densely populated (21).

A German study assessed the prevalence of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic (22). It revealed a 58% increase in the occurrence of URTIs after the pandemic compared with the rates before the pandemic (732 vs. 464, p<0.001). The increase was more evident among 18–30 year olds (22%, p<0.001) and paediatrics under 5 years of age (89%). Interestingly, a previous study had noticed a significant decrease in common respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections (GIIs) compared with the pre- and post-pandemic era (275,033 vs. 165,127) (23). It reported a significant decrease in common respiratory infections like influenza (−71%, p<0.001) and an increase in pneumonia caused by rare microbes (229%, p<0.001) after the pandemic. Another German study reported a significant decline in the occurrence of URTIs (683 vs. 439, −36%, p<0.001) and GIIs (213 vs. 120, −44%, p<0.001) before and after the pandemic (24).

The initial pandemic phase witnessed a decline (54.7% in 2010–19 to 39.1% in 2020) in common RTIs causing viruses, like adenovirus, human coronavirus (HCoV), human bocavirus (HBoV), human rhinovirus (HRV), human metapneumovirus (hMPV), HPIV, influenza virus, and RSV in Korea (25). Korea saw an increasing trend in infections by human rhinovirus (HRV) during the pandemic (26). Cases of enveloped viruses like HCoV, HMPV, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, and RSV decreased by 100% during the pandemic (27). The trend remained unaltered in non-enveloped viruses like adenovirus, HRV, and HBoV before and during the pandemic. This was attributed to the effectiveness of chemical sterilisants and antiseptic sanitisation (predominantly used during the pandemic) against enveloped virus compared with non-enveloped virus. Some physical interventions were also proposed to reduce the incidences of influenza and COVID-19-like illnesses after the pandemic, such as social distancing and the use of face masks (28). However, it was observed that the available studies do not completely approve such observations in decreasing the cases.

A study in New Zealand revealed that hospitalisation due to LRTIs by RSV, influenza A and B viruses, HRV, and adenovirus significantly decreased (<200 cases) during the initial phase of the pandemic compared with the figures of 2019 (approximately 1,000 cases) or before (2015–2018). It is attributable to strict restrictions (including lockdowns) on public movement (29). Human metapneumovirus (HMPV) infections increased among the neonates (30). Improved diagnostic capability, effective vaccines, and anti-viral agents could essentially control and prevent the disease and other similar ailments. The COVID-19 pandemic saw an increase in the infection rates of S. pneumoniae and group A streptococci in Italy (4), which could be attributed to reduced virus spread due to non-pharma interventions like face masks. With similar hospitalisation rates among infants during (46%) and after (40%) the COVID-19 pandemic, the pathophysiology of RSV remained unaltered (31). However, the COVID-19 pandemic saw variable trends during the period.

A vast majority (80–90%) of respiratory illnesses among children are attributed to viruses. Although most of these infections are self-limiting and require no medication and hospitalisation, the cause for concern is the potential for developing secondary bacterial infections like sinusitis, middle ear infections (otitis media), laryngitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia. Children are predisposed to frequent RTIs due to being in close proximity with other infected children including siblings, environmental factors, and a weak immune system.

Some preventive measures of RTIs include parent education about the self-limiting nature of most RTIs and avoiding unnecessary medication including antibiotics. Immunising children with the available vaccines (pneumococcal and influenza vaccines) and identifying family predisposition and birth defects in the respiratory system helps the implementation of preventive measures. Antibacterial chemoprophylaxis and surgical intervention (tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, and other ear and nose surgeries) is suggested based on the clinical implications of RTIs, especially among children with predisposing factors. The utility of oligosaccharides and bacterial immunostimulants (glycoproteins, ribosomes, proteoglycans, and lysates among others) in controlling and preventing complications associated with RTIs in children are being cautiously explored. Bacterial immunostimulants activate local immunological responses (32).

The supplementation of vitamins, minerals, prebiotics, probiotics, symbiotic, and postbiotics in the management and prevention of recurrent RTIs has been recently suggested. Furthermore, the role of complementary and alternative medicine in preventing RTIs in children is being augmented (33). Vitamin D and A supplementation, lactoferrin therapy, adjuvant treatment with yupingfeng granules, and dietary antioxidant supplementation are being explored for their utility in the prevention, treatment, and management of recurrent RTIs (34–38).

There has been a rebound of respiratory viral infections caused by RSV post COVID-19. Children under 5 years of age are increasingly predisposed to RSV infection. Expert consensuses recommend effective screening through clinical diagnosis followed by confirmation with laboratory diagnostic methods like nucleic acid amplification methods (PCR), rapid antigen detection methods, and viral isolation and identification to ensure physicians take appropriate patient treatment management decisions (39). The efficacy of long-acting high-potency monoclonal antibodies like nirsevimab (Beyfortus™-AstraZeneca/Sanofi) and palivizumab (Synagis™-AstraZeneca) in the treatment and prevention of RTIs caused by RSV among children and pregnant women has recently been explored (40). An improvement in indoor air quality to reduce the viral load along with the maintenance of temperature and humidity in living rooms to ensure the effective functioning of airways are some non-pharmaceutical preventive measures that have been suggested to minimise RTIs among children (41).

Conclusion

The WHO recommends effective measures to prevent RTIs, especially among the children and other susceptible (like the geriatrics) population. Resuming vaccination drives among such populations against influenza, SARS-CoV-2, etc., is also advised. COVID-19-appropriate preventive measures like social distancing, regular hand sanitising, face-masking (especially in crowded places), appropriate and rapid diagnosis, and seeking timely medical intervention are also suggested to prevent and control the spread of infections. Special advisories like avoiding travel during a reported ILI and seeking medical attention in case of an illness during travel or immediately after may be released for frequent international travellers. Travellers may be encouraged to share their previous illness-related encounters (like an inadvertent exposure) with the treating physician to facilitate appropriate diagnosis, initiate timely and effective treatment, and adopt foolproof management strategies.

Author contributions

RM: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. SI: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – original draft. VK: Validation, Writing – original draft. AG: Writing – original draft. QZ: Writing – original draft. PS: Validation, Writing – original draft. SM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the authorities of their respective affiliations for the cooperation and support that was extended.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. WHO. Upsurge of respiratory illnesses among children-Northern China 23 November 2023 (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON494 (Accessed November 26, 2023).

2. Conroy G. What’s behind China’s mysterious wave of childhood pneumonia? Nature. (2023). doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-03732-w

3. Izu A, Nunes MC, Solomon F, Baillie V, Serafin N, Verwey C, et al. All-cause and pathogen-specific lower respiratory tract infection hospital admissions in children younger than 5 years during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-22) compared with the pre-pandemic period (2015-19) in South Africa: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2023) 23:1031–41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00200-1

4. Principi N, Autore G, Ramundo G, Esposito S. Epidemiology of respiratory infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Viruses. (2023) 15:1160. doi: 10.3390/v15051160

5. Parsons J, Korsman S, Smuts H, Hsiao NY, Valley-Omar Z, Gelderbloem T, et al. Human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) detection in hospitalized children with acute respiratory tract infection in the western cape, South Africa during 2014-2022 reveals a shift in dominance of HPIV 3 and 4 infections. Diagnostics (Basel). (2023) 13:2576. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13152576

6. Abu-Raya B, ViñetaParamo M, Reicherz F, Lavoie PM. Why has the epidemiology of RSV changed during the COVID-19 pandemic? EClinicalMedicine. (2023) 61:102089. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102089

7. ViñetaParamo M, Ngo LPL, Abu-Raya B, Reicherz F, Xu RY, Bone JN, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus epidemiology and clinical severity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in British Columbia, Canada: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Reg Health Am. (2023) 25:100582. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2023.100582

8. Gong C, Huang F, Suo L, Guan X, Kang L, Xie H, et al. Increase of respiratory illnesses among children in Beijing, China, during the autumn and winter of 2023. Euro Surveill. (2024) 29:2300704. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.2.2300704

9. Harris E. WHO: surge in respiratory infections in China not due to new pathogens. JAMA. (2024) 331:15. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.24681

10. Almeida T, Guimarães JT, Rebelo S. Epidemiological changes in respiratory viral infections in children: the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Viruses. (2023) 15:1880. doi: 10.3390/v15091880

11. Abushahin A, Toma H, Alnaimi A, Abu-Hasan M, Alneirab A, Alzoubi H, et al. Impact of COVID−19 pandemic restrictions and subsequent relaxation on the prevalence of respiratory virus hospitalizations in children. BMC Pediatr. (2024) 24:91. doi: 10.1186/s12887-024-04566-9

12. Lai SY, Liu YL, Jiang YM, Liu T. Precautions against COVID-19 reduce respiratory virus infections among children in Southwest China. Med (Baltimore). (2022) 101:e30604. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000030604

13. Li ZJ, Yu LJ, Zhang HY, Shan CX, Lu QB, Zhang XA, et al. Broad impacts of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on acute respiratory infections in China: an observational study. Clin Infect Dis. (2022) 75:e1054–62. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab942

14. Editorial, The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Patterns of respiratory infections after COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. (2024) 12:1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00472-1

15. Heiss R, Tan L, Schmidt S, Regensburger AP, Ewert F, Mammadova D, et al. Pulmonary dysfunction after pediatric COVID-19. Radiology. (2023) 306:e221250. doi: 10.1148/radiol.221250

16. Nosetti L, Zaffanello M, Piacentini G, De Bernardi F, Cappelluti C, Sangiorgio C, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on brief resolved unexplained events (BRUEs) in children: A comparative analysis of pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. Life (Basel). (2024) 14:392. doi: 10.3390/life14030392

17. Song W, Yang Y, Huang Y, Chen L, Shen Z, Yuan Z, et al. Acute respiratory infections in children, before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, a sentinel study. J Infect. (2022) 85:90–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.04.006

18. Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Seasonality of influenza and other respiratory viruses. EMBO Mol Med. (2022) 14:e15352. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202115352

19. Meyer Sauteur PM, Beeton ML. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: delayed re-emergence after COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Lancet Microbe. (2023) 5(2):e100-1. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00344-0

20. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Communicable disease threats report, 3-9 December 2023, week 49. Stockholm: ECDC (2023). Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/communicabledisease-threats-report-3-9-december-2023-week-49.

21. Looi M-K. China: Rising cases of respiratory disease and pneumonia spark WHO concern. BMJ. (2023) 383:2770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.p2770

22. Loosen SH, Plendl W, Konrad M, Tanislav C, Luedde T, Roderburg C, et al. Prevalence of upper respiratory tract infections before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: A cross-sectional study of 2 167 453 outpatients. J Prim Care Community Health. (2023) 14:21501319231204436. doi: 10.1177/21501319231204436

23. Tanislav C, Kostev K. Fewer non-COVID-19 respiratory tract infections and gastrointestinal infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Virol. (2022) 94:298–302. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27321

24. Tanislav C, Kostev K. Investigation of the prevalence of non-COVID-19 infectious diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health. (2022) 203:53–7. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.12.006

25. Yum S, Hong K, Sohn S, Kim J, Chun BC. Trends in viral respiratory infections during COVID-19 pandemic, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:1685–8. doi: 10.3201/eid2706.210135

26. Kim HM, Lee EJ, Lee NJ, Woo SH, Kim JM, Rhee JE, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on respiratory surveillance and explanation of high detection rate of human rhinovirus during the pandemic in the Republic of Korea. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. (2021) 15:721–31. doi: 10.1111/irv.12894

27. Park S, Michelow IC, Choe YJ. Shifting patterns of respiratory virus activity following social distancing measures for coronavirus disease 2019 in South Korea. J Infect Dis. (2021) 224:1900–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab231

28. Jefferson T, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Al-Ansary LA, van Driel ML, Bawazeer GA, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2023) 1:CD006207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub6

29. Trenholme A, Webb R, Lawrence S, Arrol S, Taylor S, Ameratunga S, et al. COVID-19 and infant hospitalizations for seasonal respiratory virus infections, New Zealand, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:641–3. doi: 10.3201/eid2702.204041

30. Feng Y, He T, Zhang B, Yuan H, Zhou Y. Epidemiology and diagnosis technologies of human metapneumovirus in China: a mini review. Virol J. (2024) 21:59. doi: 10.1186/s12985-024-02327-9

31. Treggiari D, Pomari C, Zavarise G, Piubelli C, Formenti F, Perandin F. Characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus infections in children in the post-COVID seasons: A northern Italy hospital experience. Viruses. (2024) 16:126. doi: 10.3390/v16010126

32. Schaad UB. Prevention of paediatric respiratory tract infections: emphasis on the role of OM-85 European Respiratory Review. Eur Respir Rev. (2005) 14(95):74–7. doi: 10.1183/09059180.05.00009506

33. Chiappini E, Santamaria F, Marseglia GL, Marchisio P, Galli L, Cutrera R, et al. Prevention of recurrent respiratory infections: Inter-society Consensus. Ital J Pediatr. (2021) 47:211. doi: 10.1186/s13052-021-01150-0

34. Buendía JA, Patiño DG. Cost-utility of vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections in children. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. (2023) 21:23. doi: 10.1186/s12962-023-00433-z

35. Cheng X, Li D, Yang C, Chen B, Xu P, Zhang L. Oral vitamin A supplements to prevent acute upper respiratory tract infections in children up to seven years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2024) 5:CD015306. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD015306.pub2

36. Pasinato A, Fama M, Tripepi G, Egan CG, Baraldi E, LIRAR Study Group. Lactoferrin in the prevention of recurrent respiratory infections in preschool children: A prospective randomized study. Children (Basel). (2024) 11:249. doi: 10.3390/children11020249

37. Zhang L, Wang X, Wang D, Guo Y, Zhou X, Yu H. Adjuvant treatment with yupingfeng granules for recurrent respiratory tract infections in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:1005745. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.1005745

38. Notarbartolo V, Montante C, Ferrante G, Giuffrè M. Antioxidant effects of dietary supplements on adult COVID-19 patients: why do we not also use them in children? Antioxid (Basel). (2022) 11:1638. doi: 10.3390/antiox11091638

39. Zhang XL, Zhang X, Hua W, Xie ZD, Liu HM, Zhang HL, et al. Expert consensus on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections in children. World J Pediatr. (2024) 20:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s12519-023-00777-9

40. Verwey C, Dangor Z, Madhi SA. Approaches to the prevention and treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children: rationale and progress to date. Paediatr Drugs. (2024) 26:101–12. doi: 10.1007/s40272-023-00606-6

Keywords: children, respiratory illness, respiratory illness surveillance, China, COVID-19 pandemic era

Citation: Mohapatra RK, Ibrahim SH, Mahal A, Kandi V, Gaidhane AM, Zahiruddin QS, Satapathy P and Mishra S (2024) Rising respiratory illnesses among Chinese children in 2023 amidst the emerging novel SARS-CoV-2 variants—is there a link to the easing of COVID-19 restrictions? Front. Trop. Dis 5:1391195. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2024.1391195

Received: 25 February 2024; Accepted: 16 September 2024;

Published: 11 November 2024.

Edited by:

Alfonso J. Rodriguez-Morales, Fundacion Universitaria Autónoma de las Américas, ColombiaReviewed by:

Narges Neyazi, World Health Organization Afghanistan, AfghanistanCopyright © 2024 Mohapatra, Ibrahim, Mahal, Kandi, Gaidhane, Zahiruddin, Satapathy and Mishra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ranjan K. Mohapatra, cmFuamFua19tb2hhcGF0cmFAeWFob28uY29t; Venkataramana Kandi, cmFtYW5hMjAwMjFAZ21haWwuY29t; Snehasish Mishra, c25laGFzaXNoLm1pc2hyYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†ORCID: Ranjan K. Mohapatra, orcid.org/0000-0001-7623-3343

Snehasish Mishra, orcid.org/0000-0002-3896-5831

Ranjan K. Mohapatra

Ranjan K. Mohapatra Sarah Hameed Ibrahim2

Sarah Hameed Ibrahim2 Ahmed Mahal

Ahmed Mahal Venkataramana Kandi

Venkataramana Kandi Abhay M. Gaidhane

Abhay M. Gaidhane Quazi Syed Zahiruddin

Quazi Syed Zahiruddin Prakasini Satapathy

Prakasini Satapathy Snehasish Mishra

Snehasish Mishra