94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Trop. Dis. , 17 June 2024

Sec. Neglected Tropical Diseases

Volume 5 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2024.1321069

This article is part of the Research Topic Female Genital Schistosomiasis: Research Needed to Raise Awareness and Deliver Action View all 14 articles

Introduction: Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) is a manifestation of infection with schistosomes in the female genital area that affects an estimated 56 million women and girls in Africa. If untreated, FGS can result in severe sexual and reproductive health (SRH) complications. However, FGS is largely unrecognized by SRH providers, and there is no programmatic guidance for the integration of FGS and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) interventions in the way of a Minimum Service Package (MSP). Therefore, as part of a larger implementation study, an MSP was developed to guide program staff and health planners on how to integrate FGS and SRHR interventions in schistosomiasis-endemic countries.

Materials and methods: In collaboration with 35 experts from six sectors related to FGS, we conducted virtual workshops, engaging the participants within various specialties from around the world to identify a foundational framework for the MSP, as well as the integration points and activities for FGS and SRHR interventions. Several drafts of the MSP were developed, reviewed in virtual workshops, peer-reviewed, and then finalized by the participants.

Results: A participatory and consultative process led to the identification of a foundational framework for the integration of FGS and SRHR interventions, as well as the integration points and activities. This included identifying cadres of staff who would be needed to implement the MSP and the settings in which the service provision would take place.

Discussion: Defining an MSP to guide the integration of a minimum package of FGS services in SRHR interventions is a critical step toward ensuring the prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of women and girls in Africa. The MSP can now be rolled out and tested in a country context to start reducing the burden of this preventable and treatable neglected disease.

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is a disease caused by parasites (schistosomes) that live in freshwater in subtropical and tropical regions, where they depend on snail hosts (1). There are two main types of human schistosomiasis found in Sub-Saharan Africa: urogenital schistosomiasis caused by infection with Schistosoma haematobium and intestinal schistosomiasis caused by infection with Schistosoma mansoni (2). Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) is a manifestation of a chronic infection with the parasites responsible for urogenital schistosomiasis. FGS has been estimated to affect around 56 million women and girls across Sub-Saharan Africa, where S. haematobium is endemic (3, 4). Coastal and rural areas with a high prevalence of S. haematobium infection are more heavily affected by FGS due to factors such as the presence of suitable freshwater bodies and poor access to clean water and sanitation facilities (5, 6).

Schistosome cercariae are released from the snails and infect those who come into contact with contaminated water (1). Once in the human body, the parasites develop into adults and travel through the blood vessels to the pelvic area where the female worms release eggs that then migrate, with the aim of being excreted out of the body and continuing their life cycle (1). However, some of the eggs are lodged in body tissues, e.g., in the cervix, uterus, and vagina, where they cause an inflammatory reaction that can result in lesions. This reaction is known as FGS. Symptoms include abnormal vaginal discharge, bloody discharge, genital itching, and painful intercourse (1). If left untreated, FGS can result in anemia and serious sexual and reproductive health (SRH) complications such as contact bleeding, primary and secondary infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and low birth weight (2). Due to its clinical presentation, untreated FGS has the same symptoms as those of a recurring sexually transmitted infection (STI) and is commonly misdiagnosed as such, which contributes to repeat referrals and a failure to treat (7).

Untreated FGS has been associated with prevalent HIV (8–14). Studies have attributed the link between FGS and an increased risk of HIV to, among other factors, mucosal changes in the vaginal epithelium of the cervix and the vagina as a result of FGS, which render the area more vulnerable to HIV (9–11, 15). Some studies have also suggested a link between cervical cancer and FGS, with FGS altering the mucosal gene expression and reducing the human papillomavirus (HPV)- and cancer-protective immune responses in women (2). Further immunological changes may act to attract the HIV virus, thereby increasing the risk of HIV transmission (11, 16, 17). In Africa, there is a strong geographical correlation between areas with S. haematobium, HIV, and HPV, suggesting a HIV/HPV/schistosomiasis syndemic (1–3, 7, 18, 19).

FGS is clinically diagnosed through colposcopy or a visual pelvic inspection, similar to that for cervical cancer, to identify lesions that look like sandy patches, yellow patches, rubbery papules, or abnormal blood tissues on the vaginal tissue or the cervix (2, 7). FGS is treatable using a medication called praziquantel, which can also be used as routine preventive chemotherapy for schistosomiasis (7). The prevention and treatment for school-based children is largely done through mass drug administration (MDA), which does not reach all women and girls at risk of schistosomiasis and FGS (7). MDAs are largely delivered through neglected tropical diseases (NTD) programs and are therefore outside of the SRHR programs (7), with the WHO calling for a praziquantel rollout through SRH services in schistosomiasis-endemic areas (20, 21).

Despite its clinical presentation and due to its treatment, prevention, and reach, FGS has historically not been recognized as an SRH condition (3, 22). Moreover, FGS is usually not diagnosed and therefore not treated, due to a lack of awareness of this disease among health workers: it is not part of the national medical curricula in most schistosomiasis-endemic countries, and healthcare workers lack the training required to diagnose and treat FGS (7).

The lack of acknowledgement of FGS and of services to reduce its burden is a human rights issue and needs to be recognized as such (23). FGS is both a disease of inequality and a human rights issue, reflecting a lack of access to clean water, hygiene, and sanitation and access to adequate health services to prevent, diagnose, and treat it (24). The distribution of household chores across many communities in schistosomiasis-endemic areas puts women and girls at disproportionate risk to FGS; hence, FGS needs to be approached with a specific gendered lens (24). Williams et al. (24) highlighted that harmful gender norms play a critical role and that healthcare workers need to be sensitized to this when dealing with clients and FGS. The similarities between the signs and symptoms of FGS and those of some common STIs further contribute to the stigma and discrimination from the wider community (7, 25, 26). Therefore, FGS must be viewed as a human rights and gender equality issue, with its prevalence serving as an indicator of health inequality and addressed within integrated service delivery (23, 24).

FGS thus remains a neglected, misunderstood, understudied, and underreported issue (2, 3, 7, 23, 24); as such, there is currently no integrated programmatic guidance to support the integration of FGS and SRH. The objective of this study was therefore to fill this gap and develop programmatic guidance for FGS integration. The study also aimed to create a Minimum Service Package (MSP) for governments, public health practitioners, specialists, and programmers in schistosomiasis-endemic countries for the integration of FGS into SRHR interventions. The MSP was developed as part of a larger pilot project to integrate FGS into SRHR interventions in three counties across Kenya.

The development of the MSP was divided into two phases: (i) conceptualization and (ii) consultation. The assumptions for the development of the MSP are described at the end of this section.

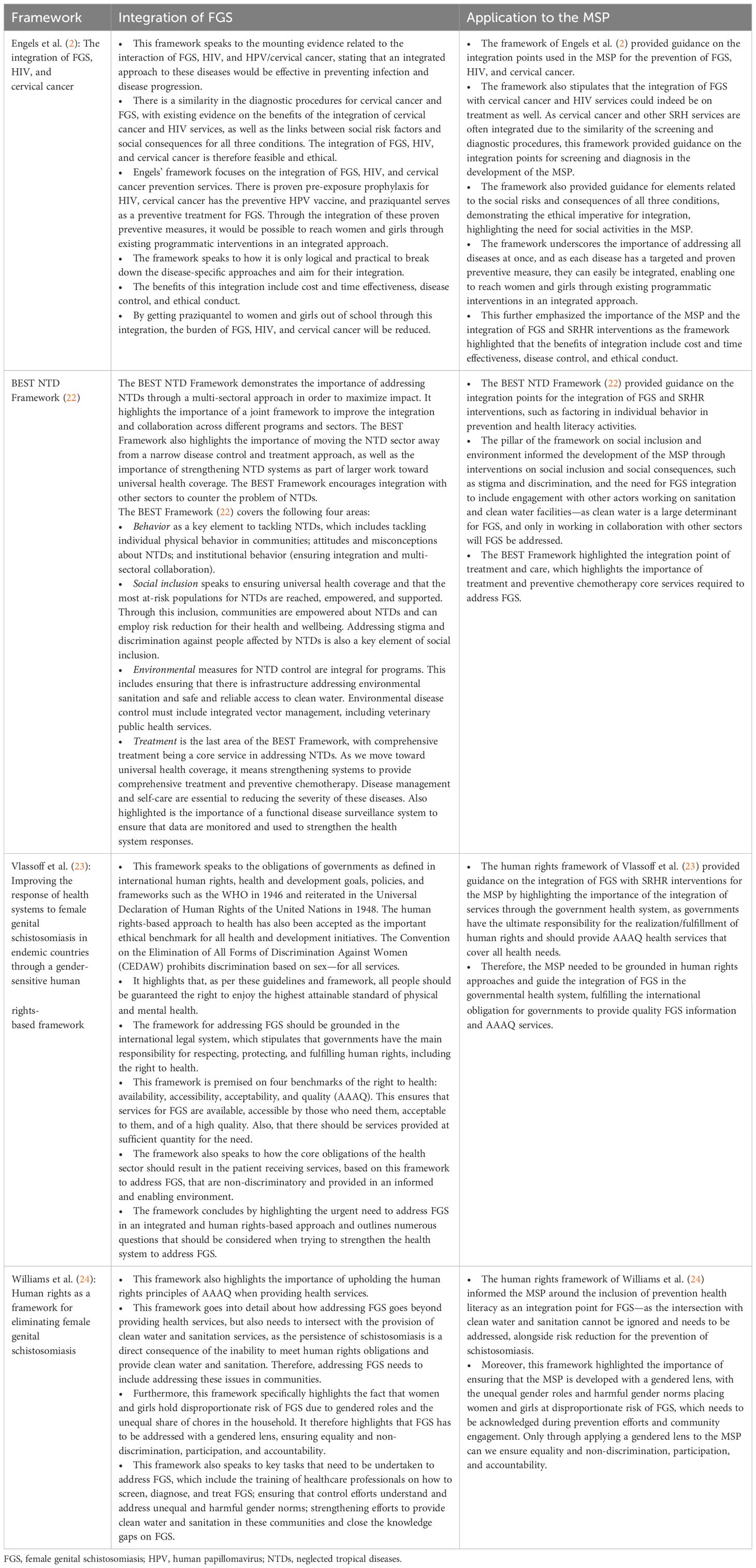

The conceptualization phase aimed to ensure the selection of the most suitable guiding frameworks and to gather feedback on the proposed framework, particularly on the FGS/SRH integration points. Four frameworks were identified as the basis for the development of the MSP through an overview review to search for key concepts and words, as well as figures and tables (27). The four frameworks reviewed were: the integration framework developed by Engels et al. (2), the BEST NTD Framework (22), the framework articulated by Vlassoff et al. (23), and the framework by Williams et al. (24). Table 1 shows an overview of the frameworks analyzed as the foundation for the MSP developed in this study. This overview supported the identification of guiding principles for the integration of FGS and SRHR interventions for the MSP, as well as the critical integration points (27).

Table 1 Overview of the frameworks serving as the foundation for the development of the Minimum Service Package (MSP).

The framework review supported the identification of the integration points for the MSP, which included health literacy, screening and diagnosis, treatment and care, and social inclusion and equity. The next stage was the consultation of experts on the development of the MSP.

The aim of this phase was to secure agreement on the selected FGS/SRH integration points. This was accomplished through two rounds of virtual consultations: i) workshop 1 held on April 26, 2023, and ii) workshop 2 conducted on May 5, 2023.

The workshops aimed to reach a cross-sectoral group of experts, with both workshops conducted online by LP and CK using Microsoft Teams as the geographical diversity among the experts necessitated virtual consultations. The recruitment process was initiated via e-mail, adhering to the principles of purposeful sampling to ensure representation from all six essential sectors for effective FGS service integration: NTDs, FGS, SRH, HIV, WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene), and cervical cancer. Our recruitment efforts specifically targeted members of the FGS Integration Group and scholars and policymakers with experience or publications related to FGS. A small planning group within the cross-sectoral research team formulated the objectives, the approach, and the proposed outputs for each virtual workshop. These workshops were conducted in English and were facilitated by LP and CK. Following the workshop discussions, the participants actively contributed to and engaged in a peer review of the outcomes produced during each workshop.

The objective of workshop 1 was to consult a group of experts from six sectors on the framework review for FGS integration and the selected integration points for FGS and SRHR interventions.

The first virtual workshop was held on April 26, 2023, with a duration of 2.5 h. A total of 20 experts from the NTD (n = 7), HIV (n = 5), SRH (n = 2), WASH (n = 1), cervical cancer (n = 2), and FGS (n = 3) sectors attended the first virtual workshop. These experts were geographically spread across West, East, and Southern Africa, Europe, and Northern America. The workshop was divided into seven sessions: 1) an introductory session; 2) introduction of the project; 3) a review of the draft integration frameworks; 4) integration points for FGS and SRH services; 5) task for group work; 6) group work; and 7) feedback from group work and way forward. To focus the workshop and to obtain more detailed feedback, group work was designed to go through two integration points per group. Each group had to address the following discussion points: what is missing, key concerns/challenges, and additions. A final discussion session was held to agree on what was discussed around the integration points and to decide on a way forward. The draft was then modified according to the expert comments gathered from workshop 1.

As part of the workshop 1 process, LP and CK convened a workshop with three SRH and HIV partners in Africa that work on FGS, which included four experts from Nigeria (n = 2), Malawi (n = 1), and Uganda (n = 1). The experts’ comments and revisions were discussed and factored into the new draft. If a comment or a suggested revision was not clear, a time was set for the experts to discuss and understand the points further.

The new draft was then shared with the group of experts who were part of both consultative workshops and with an additional 14 experts from the six sectors across the world. Comments were received and the draft was again reviewed accordingly.

The objective of workshop 2 was to review the final draft of the MSP, including the revised framework and the integration points for FGS and SRH, with the goal of finalizing the MSP as an expert group. This final virtual interactive workshop was held on May 5, 2023, for a period of 2 h. A total of 12 experts from the NTD (n = 4), HIV (n = 4), SRH (n = 1), WASH (n = 1), cervical cancer (n = 1), and FGS (n = 1) sectors spread across West, East, and Southern Africa, North America, and Europe attended the final virtual workshop. The workshop was split into four sections: introduction and the process followed thus far; presentation of the proposed final framework and MSP; specific comments/concerns flagged in the expert peer review; and discussion. The experts were given the opportunity to highlight assumptions and elements to note for the implementation of the MSP, which are outlined in this paper. The comments collected in the final workshop were then factored into the drafts of the MSP before its finalization. The draft was concluded and is ready to be tested in a country context; however, during development, various assumptions were discussed as essential for the successful implementation of the MSP, which are outlined below.

The development of the MSP was done using a patient-centered perspective for programmatic services, which used patient/user experiences and perspectives (28) to ensure that the user’s journey is clear. Developing the MSP based on a patient-centered perspective also ensures that it is principle-driven, putting the needs and rights of the patients at the core of service delivery (28).

As the MSP was developed with a patient-centered perspective, no elements related to the training of staff were included. It was assumed that staff implementing the MSP would be trained regarding FGS, applicable to their cadre, as per the training competencies to ensure successful implementation (7, 25, 26). Another requirement is that staff implementing the MSP must be sensitized and trained in providing youth-friendly, gender-sensitive, and non-judgmental services to ensure social inclusion and equity. All healthcare workers must also understand the association between FGS and gender-based violence. The need to include gender-based violence and social inclusion and equity activities in the implementation of FGS services was well laid out in the frameworks of Vlassoff et al. (23) and Williams et al. (24), as well as in the BEST NTD Framework (22). It was also assumed that all healthcare workers practice the patient feedback protocol, whereby the patient is provided with feedback on the diagnosis, treatment, and referrals for FGS, with a mechanism for the patient to provide feedback in return. Moreover, it is integral that a culture of quality improvement in the provision of integrated FGS services is embedded.

The applicable recording and documentation of FGS cases is also a requirement after FGS diagnosis, which adds scientific evidence on the burden of FGS. Therefore, the implementation of the MSP should be done in partnership with government and public health facilities, and discussions on the documentation of FGS diagnosis and burden need to take place with the relevant government organizations. This is because, without documentation of FGS, the government would not procure praziquantel, which is required for prevention and treatment, nor would it see the need for resourcing for FGS service provision. As such, the MSP does not include guidance on how implementation is monitored and evaluated or how data on FGS cases are collected and communicated as part of national and sub-national health management information systems.

A critical element for the ethical implementation of the MSP is the availability of praziquantel in all facilities implementing the MSP and in schools where MDAs are implemented. Engels et al. (2) and Jacobson et al. (7) highlighted the need for access to praziquantel when providing FGS services. Should praziquantel not be available from the government in programs implementing the MSP, it should be procured and reported to the NTD department of the Ministry of Health for the required reporting of praziquantel distribution to the WHO.

Although women and girls have a higher disproportionate risk of FGS, the MSP was purposefully developed to be gender-neutral in order to include individuals who identify as transgender, intersex, and gender non-binary, as well as gender-nonconforming individuals, ensuring that any person with a female reproductive organ that can be affected by FGS is able to receive services (24). The MSP is specifically worded in a gender-neutral way to ensure that no one is left behind; however, FGS should also be viewed with a gendered lens due to the disproportionate risk that women and girls face, as highlighted by Vlassoff et al. (23) and Williams et al. (24). To ensure social inclusion and equity, there needs to be ongoing advocacy for resources so that equipment, medication, and the training of healthcare workers are prioritized and that the integration of FGS is sustainable (2, 22–24). The MSP does not highlight a specific role for women and girls; rather, it is assumed that women can be agents of change through delivering different elements of the MSP, depending on their position in the community and health facility. Adolescent girls and young women could implement the health literacy component, as peer educators or community healthcare workers. It is, however, acknowledged that this will be contextual.

As clinical guidance already exists in the WHO FGS Pocket Atlas (29), the MSP does not provide any guidance for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of FGS, but signposts to relevant materials on this topic. Moreover, the MSP does not assume that praziquantel cures FGS. It is acknowledged that praziquantel kills the worms, decreases the inflammation caused by schistosomiasis, and allows the body to heal uncalcified lesions, but it is not a curative medication for FGS and the complications that may have ensued due to FGS (15, 29). The MSP also acknowledges and references that community- and school-based MDAs remain an important prevention point for FGS among young women and girls (7).

Most importantly, for the MSP to be successfully implemented, program managers will need to ensure that stakeholders understand that a quality and comprehensive package of SRH services needs to include FGS in schistosomiasis-endemic areas, thereby recognizing FGS as an SRH condition (30).

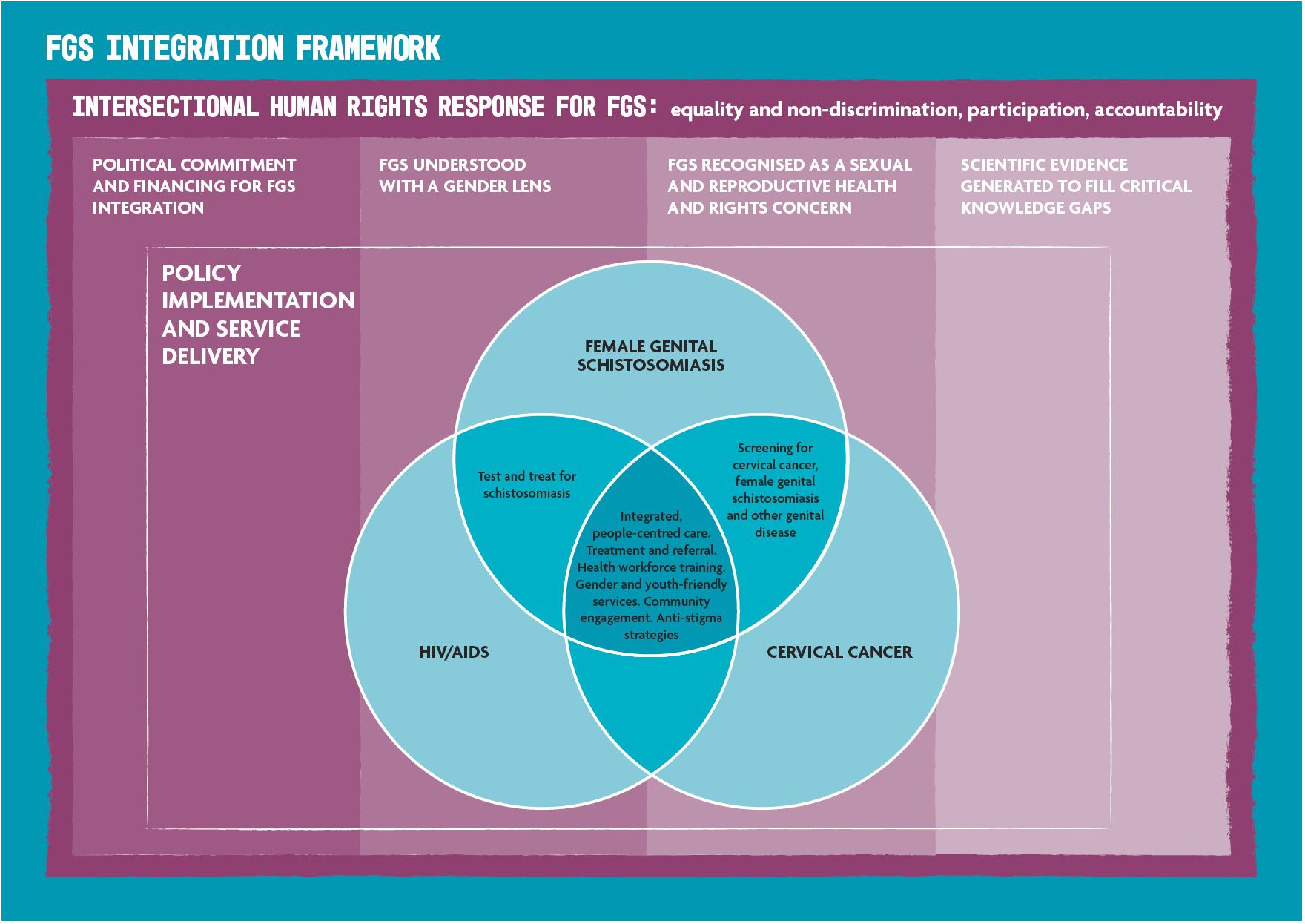

Following the overview review of the frameworks, an adapted framework was selected for the integration of FGS and SRHR interventions, which was based on an existing framework detailing the integration of FGS, HIV, and cervical cancer (2). The selected adapted version of this framework (Figure 1) emphasizes human rights principles for addressing FGS: equality and non-discrimination, participation, and accountability (31). In addition, the adapted framework (Figure 1) included assumptions for the successful implementation of FGS and SRHR interventions, such as political commitment and financing for FGS integration, viewing FGS with a gendered lens, recognizing FGS as an SRH issue, and generating scientific evidence to fill knowledge gaps (31).

Figure 1 Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) integration framework adapted from Engels et al. (2) and Williams et al. (24).

Through a participatory process, the project team identified four service points for the integration of FGS and SRH services: health literacy, screening and diagnosis, treatment and care, and social inclusion and equity (cross-cutting). The MSP indicates possible venues for service delivery, but this is not a strict requirement as the setting for the provision of services will be contextual.

The first service integration point identified in the MSP is health literacy on FGS integrated into health literacy activities that take place in SRHR interventions, as shown in Table 2. Health literacy largely takes place in the community setting through the work of peer educators, community healthcare workers, or volunteers to mobilize patients for SRHR interventions. Integrated FGS health literacy activities could also take place in healthcare facilities at all levels—primary, secondary, and tertiary facilities—should the patient not have been reached in the community. The integration of FGS health literacy into SRHR interventions includes health education and social behavior change communication (SBCC)/information, education, and communication (IEC) on the following topics outlined below.

The second integration point for FGS identified in the MSP is screening and diagnosis, outlined in Table 3. The screening and diagnosis of FGS, as with other screening and diagnosis services in an SRH program, takes place in primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare facilities and performed by a healthcare worker (nurse or doctor). The MSP outlines how FGS screening and diagnosis services can be integrated into SRH services as follows.

It is important to note that the MSP outlines that, for girls who are pre-sexual debut, a pelvic examination is not appropriate; therefore, a risk assessment and verbal screening are instead performed, with praziquantel provided presumptively as part of the treatment and care services. No colposcopy or pelvic examination can be completed, thereby not allowing diagnosis.

The third integration point concerns FGS treatment and care, as outlined in Table 4. The treatment and care services for FGS can be incorporated into the delivery of SRH services for the treatment of SRH conditions. These can be provided by a healthcare worker (doctor and nurse) at all levels of healthcare facilities and in the community, such as during MDA. The MSP outlines how the following FGS treatment and care services can be integrated into SRH services.

Girls who are pre-sexual debut and for whom no diagnosis could be completed should be provided with praziquantel as treatment, should the screening identify the possibility of FGS, or as prevention.

The final integration point relates to advocacy and to addressing the structural barriers that exacerbate the burden of FGS, as displayed in Table 5. These include barriers to the access of FGS services, risk reduction of exposure to contaminated water, barriers to the access of praziquantel, and activities to reduce the risk of and address gender-based violence. They sit under a cross-cutting component called social inclusion and equity. This integration point cuts across all SRHR interventions and would take place in community settings and at all levels of healthcare. This integration point includes all cadres of staff in an SRH program. The following activities are included.

FGS is a debilitating SRH condition that affects millions of women and girls across Africa and is associated with SRH issues, including infertility and subfertility. Current interventions focus on MDAs for the distribution of praziquantel, the drug used to prevent and treat schistosomiasis and, therefore, prevent FGS (7). In order to rapidly scale-up the reach and effectiveness, it is important that FGS services are integrated into health services (7). Preston et al. (32) have reiterated the importance of the early prevention and availability of praziquantel in schistosomiasis-endemic countries, such as Cote d’Ivoire. For this to happen, program staff, health planners, and government officials need to be able to address FGS through SRHR interventions and to recognize it as an SRH condition (30). The MSP addresses this problem by providing guidance to health managers, programmers and planners, and SRH service providers on the minimum package of FGS services that can be integrated into ongoing SRHR interventions at the community and health facility levels.

The MSP was developed based on the assumption that the integration of FGS into SRHR interventions is possible, feasible, and realistic. The reasons for this assumption are as follows: the populations affected, the similarities in the signs and symptoms of FGS and STIs, as well as the screening and diagnosis for FGS and other SRH conditions, and the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV and FGS due to a poor understanding of FGS and its link to infertility (2, 30). Existing frameworks (2, 22–24) were reviewed, gaps were identified, and a new adapted framework was developed (31), which informed the MSP. A participatory and multidisciplinary approach was used for both the adapted framework and the MSP. The adapted model extends beyond a clinical service delivery framework, recognizing person-centered and human rights approaches and the need for a gendered response (23, 24). This rationale and paradigm shift aligned with the findings of studies calling for FGS integration. Scholars have urged policy makers i) to view the issue of FGS neglect with a human rights lens and ii) to include FGS as a critical SRH condition in SRHR normative guidance for policy making, budgetary processes, and service delivery at the country level (3, 21, 24, 30, 33–36).

The MSP is therefore informed by human rights principles encompassing equality, non-discrimination, participation, and accountability (23, 24). It speaks to the importance of addressing structural barriers such as access to water and sanitation; the empowerment and involvement of communities and stigma (22); and the need for advocacy efforts for resourcing, strategies, medication, and training to alleviate the burden of FGS (23, 24). It also emphasizes an ethical imperative for comprehensive integrated SRH services (2, 22, 30, 32).

The four integration points identified in the MSP (i.e., health literacy, screening and diagnosis, treatment and care, and social inclusion and equity) provide concrete guidance to program staff on the incorporation of FGS into routine SRHR programs, ensuring that a patient’s journey and needs were central to its development. The MSP enables program staff, health planners, and government officials to address FGS through SRHR interventions and to recognize it as an SRH condition (30).

There are a number of limitations to the MSP. In terms of the participatory process used for its development, it was developed over a short time period due to the project in which it is placed. The consultation process could have been more comprehensive, with more consultations held to ensure maximum participation over a longer time period and with greater representation of experts from schistosomiasis-endemic countries. With more time, additional sectors could also have been identified for consultation.

The prerequisites for the implementation of the MSP constitute another limitation, as noted in Essential assumptions for the successful implementation of the MSP. The absence of these factors would limit the successful implementation of the MSP or may even hinder its implementation. Firstly, the MSP purposefully excludes clinical guidelines or training materials on FGS. Rather, the MSP references existing resources, including the FGS training competencies (7) and the WHO FGS World Pocket Atlas (29). Despite the lack of clinical guidelines in the MSP, we also acknowledge that there are existing questions regarding the diagnosis of FGS without relying on colposcopy. Although the easiest route of integration is through cervical cancer screening, as pelvic examination will already be taking place, the MSP outlines that, in schistosomiasis-endemic areas, it is ethical to use additional entry points for the integration of FGS (2). In addition, integrated FGS services need to be client-centered, with the applicable quality assurance processes in place, as is expected in the provision of any healthcare service (7), however, the MSP does not provide guidance on these quality assurance processes. An extremely important prerequisite is that praziquantel must be available in health facilities for prevention and treatment (32). This is due to the fact that, in most countries, praziquantel is largely only available through MDAs (2, 7). This is, in itself, partly dependent on the effective ownership and rollout of the MSP, which is designed to generate demand for praziquantel through increasing awareness, screening, and referrals and through capturing FGS data.

The FGS and SRHR integration and the uptake of the MSP also require that FGS is recognized as a neglected SRH issue, that research is undertaken to address evidence gaps, and that political commitment is secured not least to release financial and other resources (2, 3, 7, 23–25). Advocacy is necessary to support this broader environment for the uptake and rollout of the MSP. A demonstration project will assess the MSP through examining the feasibility, acceptability and the cost of using this model for the integration of FGS into the SRHR interventions in the Homa Bay, Kilifi, and Kwale counties of Kenya. This pilot will support the adoption and implementation of the MSP in other countries. Multi-context implementation is recommended to support learning and further adaptation in order to provide a tested and costed model for the integration of FGS and SRHR for health planners, programmers, and service providers.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

LP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. IU-W: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. DS: Writing – review & editing. CK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RK: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Financial support was received from the Children's Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) for the this research and publication, through a grant made by CIFF to Frontline AIDS for the FGS integration project - under grant agreement number 2210-08013.

The authors would like to acknowledge the funder of this project, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF). The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the FGS Integration Group as well as all of the experts that contributed to the MSP process. This list is not exhaustive but includes all experts that provided consent to be named as having contributed to the MSP development: Patriciah Jeckonia, LVCT Health, Kenya; Millicent Ouma, LVCT Health, Kenya; Felicia Wong, FGS Integration Group, United Kingdom; Dr. Julie Jacobson, Bridges to Development, United States; Dr. Victoria Gamba, FGS Integration Group, Kenya; Dr. Anouk Gouvras, Global Schistosomiasis Alliance, United Kingdom; Yael Vellleman, Unlimit Health, United Kingdom; Dr. Alison Krentel, University of Ottawa/Bruyere Research Institute, Canada; Susan D’Souza, Sightsavers, United Kingdom; Sarah Hand, Avert, United Kingdom; Ashley Preston, Unlimit Health, United Kingdom; Dr. Akinola Oluwole, Sightsavers, Nigeria; Manjit Kaur, Mabadiliko Changemakers, Uganda; Simon Sikwese, Pakachere IDHC, Malawi; Dr. Pasquine Ogunsanya, Alive Medical Services, Uganda; Judith Gbagidi, Education as a Vaccine (EVA), Nigeria; Solomon Ogwuche, EVA, Nigeria; Dr. Amaya L. Bustinduy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), United Kingdom; Dr. Bodo Ransdriansolo, Madagascar; Dr. Clara Rasoamanamihaja, Madagascar; Dr. Dirk Engels, Uniting to Combat NTDs, Switzerland; Dr. Pamela Sabina Mbabazi, WHO, Switzerland; Dr. Marc Steben, Chair of the Canadian Network for HPV Prevention/Co-president HPV Global Action, Canada; Prof. Margaret Gyapong, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ghana; Geoffrey Muchiri Njuhi, Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), Kenya; Dr. Kebede Kassaye, CIFF, Ethiopia; Dr. Helen Kelly, LSHTM, United Kingdom; Sally Theobald, Liverpool School of Tropical Medical, United Kingdom; Dr. William Evan Secor, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States; Kreeneshni Govender, UNAIDS, Switzerland.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AAAQ, availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality; ART, anti-retroviral treatment; FGS, female genital schistosomiasis; GBV, gender-based violence; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; IEC, information, education, and communication; MDA, mass drug administration; MSP, Minimum Service Package; NTD, neglected tropical diseases; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SBCC, social and behavior change communication; SRHR, sexual and reproductive health and rights; SRH, sexual and reproductive health; STI, sexually transmitted infection; VIA, visual inspection with acetic acid; VILI, visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine; WASH, water, sanitation, and hygiene; WHO, World Health Organization.

1. Kjetland EF, Leutscher PDC, Ndhlovu PD. A review of female genital schistosomiasis. In Trends Parasitol. (2012) 28:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.10.008

2. Engels D, Hotez PJ, Ducker C, Gyapong M, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, et al. Integration of prevention and control measures for female genital schistosomiasis, hiv and cervical cancer. Bull World Health Organ. (2020) 98:615–24. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.252270

3. UNAIDS. No More Neglect - Female Genital Schistosomiasis and HIV (2019). Available online at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/female_genital_schistosomiasis_and_hiv.

4. UNAIDS (n.d). Global AIDS Strategy 2021–2026. Available online at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-strategy-2021–2026_en.pdf.

5. Lai YS, Biedermann P, Ekpo UF, Garba A, Mathieu E, Midzi N, et al. Spatial distribution of schistosomiasis and treatment needs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and geostatistical analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. (2015) 15:927–40. doi: 10.1016/S1473–3099(15)00066–3

6. Ursini T, Scarso S, Mugassa S, Othman JB, Yussuph AJ, Ndaboine E, et al. Assessing the prevalence of Female Genital Schistosomiasis and comparing the acceptability and performance of health worker-collected and self-collected cervical-vaginal swabs using PCR testing among women in North-Western Tanzania: The ShWAB study. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2023) 17:2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011465

7. Jacobson J, Pantelias A, Williamson M, Kjetland EF, Krentel A, Gyapong M, et al. Addressing a silent and neglected scourge in sexual and reproductive health in Sub-Saharan Africa by development of training competencies to improve prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) for health workers. Reprod Health. (2022) 19:2, 5, 9, 10. doi: 10.1186/s12978–021-01252–2

8. Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Gomo E, Mduluza T, Midzi N, Gwanzura L, et al. Association between genital schistosomiasis and HIV in rural Zimbabwean women. AIDS. (2006) 20:2. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000210614.45212.0a

9. Zirimenya L, Mahmud-Ajeigbe F, McQuillan R, Li Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the association between urogenital schistosomiasis and HIV/AIDS infection. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2020) 14:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008383

10. Bullington BW, Klemperer K, Mages K, Chalem A, Mazigo HD, Changalucha J, et al. Effects of schistosomes on host anti-viral immune response and the acquisition, virulence, and prevention of viral infections: A systematic review. PloS Pathog. (2021) 17:2. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009555

11. Patel P, Rose CE, Kjetland EF, Downs JA, Mbabazi PS, Sabin K, et al. Association of schistosomiasis and HIV infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 102:544–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.088

12. Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Mduluza T, Deschoolmeester V, Midzi N, Gomo E, et al. The effects of genital schistosoma haematobium on human papillomavirus and the development of cervical neoplasia after five years in a Zimbabwean population. Eur J gynaecological Oncol. (2010) 31:169–73.

13. Kutz JM, Rausche P, Rasamoelina T, Ratefiarisoa S, Razafindrakoto R, Klein P, et al. Female genital schistosomiasis, human papilloma virus infection, and cervical cancer in rural Madagascar: a cross sectional study. Infect Dis Poverty. (2023) 12:89. doi: 10.1186/s40249-023-01139-3

14. Rafferty H, Sturt AS, Phiri CR, Webb EL, Mudenda M, Mapani J, et al. Association between cervical dysplasia and female genital schistosomiasis diagnosed by genital PCR in Zambian women. BMC Infect Dis. (2021) 21:2. doi: 10.1186/s12879–021-06380–5

15. Norseth HM, Ndhlovu PD, Kleppa E, Randrianasolo BS, Jourdan PM, Roald B, et al. The colposcopic atlas of schistosomiasis in the lower female genital tract based on studies in Malawi, Zimbabwe, Madagascar and South Africa. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2014) 8:2, 6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003229

16. Fairfax K, Nascimento M, Huang SC, Everts B, Pearce EJ. Th2 responses in schistosomiasis. Semin Immunopathol. (2012) 34(6):863–71. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0354-4

17. Turner JD, Jenkins GR, Hogg KG, Aynsley SA, Paveley RA, Cook PC, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells contribute to the regulation of colonic Th2 granulomatous pathology caused by schistosome infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2011) 5(8):e1269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001269

18. Kjetland EF, Hegertun IE, Baay MF, Onsrud M, Ndhlovu PD, Taylor M. Genital schistosomiasis and its unacknowledged role on HIV transmission in the STD intervention studies. Int J STD AIDS. (2014) 25:705–15. doi: 10.1177/0956462414523743

19. Christinet V, Lazdins-Helds JK, Stothard JR, Reinhard-Rupp J. Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS): From case reports to a call for concerted action against this neglected gynaecological disease. In Int J Parasitol. (2016) 46:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.02.006

20. World Health Organization. Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals - A Road Map for neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030 (2020). Available online at: http://apps.who.int/bookorders.

21. World Health Organization, UINICEF, World Food Programme. Expanding the reach and coverage of deworming programmes for soil-transmitted helminthiases and schistosomiasis, leveraging opportunities and building capacities POLICY BRIEF DEWORMING FOR ADOLESCENT GIRLS AND WOMEN OF REPRODUCTIVE AGE. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO publication (2021).

22. NTD NGO Network. The BEST Framework: A comprehensive approach towards Neglected Tropical Diseases. (2017). Available at: https://www.ntd-ngonetwork.org/the-best-framework.

23. Vlassoff C, Arogundade K, Patel K, Jacobson J, Gyapong M, Krentel A. Improving the response of health systems to female genital schistosomiasis in endemic countries through a gender-sensitive human rights-based framework. Diseases. (2022) 10:125. doi: 10.3390/diseases10040125

24. Williams CR, Seunik M, Meier BM. Human rights as a framework for eliminating female genital schistosomiasis. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2022) 16:2, 3, 5, 6, 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010165

25. Kukula VA, MacPherson EE, Tsey IH, Stothard JR, Theobald S, Gyapong M. A major hurdle in the elimination of urogenital schistosomiasis revealed: Identifying key gaps in knowledge and understanding of female genital schistosomiasis within communities and local health workers. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2018) 13:2, 5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007207

26. Mutsaka-Makuvaza MJ, Matsena-Zingoni Z, Tshuma C, Katsidzira A, Webster B, Zhou XN, et al. Knowledge, perceptions and practices regarding schistosomiasis among women living in a highly endemic rural district in Zimbabwe: Implications on infections among preschool-Aged children. Parasites Vectors. (2019) 12:2, 5. doi: 10.1186/s13071–019-3668–4

27. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. In Health Inf Libraries J. (2009) 26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

28. Nabulsi D, Abou Saad M, Ismail H, Doumit MAA, El-Jamil F, Kobeissi L, et al. Minimum initial service package (MISP) for sexual and reproductive health for women in a displacement setting: a narrative review on the Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon. Reprod Health. (2021) 18:5. doi: 10.1186/s12978–021-01108–9

29. World Health Organization. Female genital schistosomiasis: A pocket atlas for clinical health-care professionals (2015). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509299.

30. Umbelino-Walker I, Wong F, Cassolato M, Pantelias A, Jacobson J, Kalume C. Integration of female genital schistosomiasis into HIV/sexual reproductive health and rights and neglected tropical disease programmes and services: a scoping review. Sexual Reprod Health Matters. (2023) 31:6, 9. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2023.2262882

31. Frontline AIDS and Unlimit Health. Unlocking Health and Opportunity for women and girls in Africa - Tackling a neglected reproductive health crisis (2023). Available online at: https://frontlineaids.org/resources/fgs-policy-brief/.

32. Preston A, Vitolas CT, Kouamin AC, Nadri J, Lavry SL, Dhanani N, et al. Improved prevention of female genital schistosomiasis: piloting integration of services into the national health system in Cote d’Ivoire. Front Trop Dis. (2023) 4:1308660. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2023.1308660

33. Krentel A, Steben M. A call to action: ending the neglect of female genital schistosomiasis. J Obstetrics Gynaecology Canada. (2021) 43:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2020.11.008

34. Mazigo HD, Samson A, Lambert VJ, Kosia AL, Ngoma DD, Murphy R, et al. “We know about schistosomiasis but we know nothing about FGS”: A qualitative assessment of knowledge gaps about female genital schistosomiasis among communities living in schistosoma haematobium endemic districts of Zanzibar and Northwestern Tanzania. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2021) 15:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009789

35. Bustinduy AL, Randriansolo B, Sturt AS, Kayuni SA, Leustcher PDC, Webster BL, et al. An update on female and male genital schistosomiasis and a call to integrate efforts to escalate diagnosis, treatment and awareness in endemic and non-endemic settings: The time is now. In Adv Parasitol. (2022) 115:1–44. doi: 10.1016/bs.apar.2021.12.003

36. SCI Foundation. Policy Brief: Female Genital Schistosomiasis - A neglected reproductive health disease (2023). Available online at: https://unlimithealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/SCIF_FGS_Position_Paper.pdf.

Keywords: female genital schistosomiasis, sexual and reproductive health and rights, sexual and reproductive health, HIV, cervical cancer, integration

Citation: Pillay LN, Umbelino-Walker I, Schlosser D, Kalume C and Karuga R (2024) Minimum Service Package for the integration of female genital schistosomiasis into sexual and reproductive health and rights interventions. Front. Trop. Dis 5:1321069. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2024.1321069

Received: 13 October 2023; Accepted: 06 May 2024;

Published: 17 June 2024.

Edited by:

Amy S. Sturt, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Hong You, The University of Queensland, AustraliaCopyright © 2024 Pillay, Umbelino-Walker, Schlosser, Kalume and Karuga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leora N. Pillay, bHBpbGxheUBmcm9udGxpbmVhaWRzLm9yZw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.