94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Trop. Dis., 03 February 2023

Sec. Disease Prevention and Control Policy

Volume 4 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2023.978528

This article is part of the Research TopicPublic Health Surveillance Systems and Outbreak Response: Evidence from the FieldView all 5 articles

Objectives: The main objective of this study was to assess the roles of traditional healers and the challenges they face in the of prevention and control of both local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic, with a special emphasis on the work of traditional healers and healing centers in the East Gojjam Zone in northwestern Ethiopia, between 2020 and 2021.

Methods: From 25 February 2021 to 2 May 2021, a mixed-methods study (qualitative techniques combined with a quantitative approach) was carried out. The study was conducted by traditional healers and at healing centers in the East Gojjam Zone. The quantitative sample size was calculated based on the assumption of a single population proportion formula. As part of the qualitative research, levels of data saturation were continuously monitored, and were used to determine what the maximum number of study participants should be. Traditional healers and their clients were the study units for the quantitative component, whereas traditional healthcare providers (of all types) and religious leaders were purposively selected as the study units for the qualitative part. Descriptive and inferential statistical methods of analysis, and narrative- and content-wise methods of analysis, were used for the quantitative and qualitative components of this study, respectively.

Results: The quantitative findings of this study showed that 64.27% of respondents (95% CI 59.53% to 68.74%) had a good awareness of regional disease outbreaks and of the COVID-19 pandemic. Only 9.59% of people had a positive opinion regarding local disease outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the preventive and control measures that were employed in response to these (95% CI 7.11% to 12.83%). In addition, this study revealed that a small percentage of participants (i.e., 2.16%) used traditional control and preventive measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and local disease outbreaks.

Conclusion: Less than one-tenth of respondents had a favorable attitude toward local disease outbreaks, the current COVID-19 pandemic, and the preventive and control measures that were employed in response to these. In addition, only a small number of study participants had actually used conventional control and preventive measures in response to local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly two-thirds of respondents had a good understanding of the preventive and control measures that were employed in response to local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Traditional healers have a crucial yet underappreciated role in the prevention and control of health issues, as well as in addressing many community healthcare needs. The World Health Organization (WHO)’s “Traditional Medicine Strategy (2014–2023)” publication reflects this need to recognize the contributions of traditional healers, and to involve them in national healthcare systems. In addition, 88% of the population in over 170 WHO member states have acknowledged using traditional medicine (1) and, in general, traditional medical entities and providers treat a larger number of patients than biomedical healthcare facilities.

Furthermore, over 80% of people worldwide receive their health treatment from traditional (non-biomedical) health facilities, and in some WHO regions this proportion is substantially higher. To illustrate this point, almost 90% of the population in the Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asian, and Western Pacific areas of the world report using traditional and complementary medical services, whereas, in Ethiopia, approximately 79% of the population accesses this type of healthcare (1). Furthermore, in some settings, such as Ethiopia, traditional healing centers have historically been the primary choice of patients seeking medical attention (2), although, in recent cholera outbreaks in Ethiopia, certain traditional healing centers were among the sources of disease transmission (3).

Given this context, consideration of the roles of traditional practitioners and healing centers in response to disease outbreaks (including epidemics), and pandemics, is critical. This need has become more evident in light of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted public health on both the local and global scales. The trajectory and legacy of this pandemic have changed the way that healthcare is provided and how all parts of life are currently viewed (4). Throughout the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO suggested preventive actions to combat or mitigate the epidemic, but the ability of individual nations to establish such measures was dependent on a number of factors, including the nation in question’s economic standing and culture, and the effectiveness of its health systems (5).

During local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional healers are integral to sector-wide disease prevention and containment efforts (6). Admittedly, the roles of traditional healers and the challenges traditional healers and healing centers face in the prevention and control of local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic are vague and variable across countries. For example, in China (7) and India (8), traditional healers and traditional healing centers collaborating with modern (biomedical) healthcare facilities can be highly influential and effective. Conversely, in African nations, traditional healers are seen as a barrier to the prevention and management of disease outbreaks and pandemics (9). Some traditional healers in Africa play a significant role in the provision of healthcare and the generation of new health-related knowledge, but the majority have divergent perspectives on the causes of, and optimal treatments for, diseases such as malaria (10). In Nigeria, for example, a minority of traditional healers attribute the cause of malaria to evil spirits. This belief precludes their referral of afflicted individuals to biomedical healthcare facilities, because they believe such facilities to be incapable of treating the disease, and, furthermore, that treatment at these facilities will compromise the efficacy of any herbal treatments that they may have administered.

While on the one hand, traditional healers may be criticized for delaying medical treatment in this manner, a study conducted in Tanzania found that traditional healers played a key role in supporting malaria outbreak containment (11).

In general, the evidence suggests that, despite unfavorable potential attitude and knowledge gaps, traditional healers and traditional healing centers have a high capacity to effectively address local disease outbreaks and epidemics. On the other hand, they have limited infrastructure, which may limit their ability to do so (12).

Within Ethiopia, traditional healers are viewed as important in both urban and rural communities. For example, a recent study conducted in Addis Ababa revealed that more than half of the population preferred traditional healers to modern public health facilities, regardless of the lack of collaboration between the two sets of practitioners (13). Despite a long history of traditional medicine and a wealth of indigenous knowledge in Ethiopia, in general, and in the East Gojjam Zone, specifically, the roles and difficulties faced by these traditional healers and healing centers have not yet been thoroughly explored.

Therefore, the primary goal of this research was to evaluate the contributions that healers with indigenous knowledge have made, as well as the difficulties of applying indigenous knowledge in the prevention and containment of local disease outbreaks and pandemics (such as COVID-19), with a particular emphasis on traditional healers and healing centers in the East Gojjam Zone of northwestern Ethiopia.

From 25 February 2021 to 2 May 2021, a cross-sectional, mixed-methods investigation was carried out. The study was conducted in the East Gojjam Zone of Ethiopia, one of 13 administrative zones in the Amhara area. All registered traditional healers and healing centers in the East Gojjam Zone were surveyed for the source population and the study population. According to data obtained from the East Gojjam Zonal Health Department and East Gojjam Zone dioceses, there are 40 registered traditional healing practitioners and 70 “major” religious healing sites in East Gojjam. “Major” religious healing sites are religious sites with holy water sites, and with onsite residential rooms that individuals can rent on a semi-permanent, or short-term, basis.

The Debre Markos University’s Haddis Alemayehu Institute of Cultural Studies granted ethics approval for this study. In addition, written approval was sought from each respondent, as well as the district offices of the Ethiopian Orthodox churches in the East Gojjam Zone, and the appropriate health offices.

A respondent was deemed to have good knowledge if they were able to correctly respond to more than 75% of the knowledge-related items in the questionnaire. In this study, the authors use the terms awareness and knowledge interchangeably (14).

A respondent was deemed to have poor knowledge/awareness if they were unable to correctly respond to at least 75% of the knowledge-related items in the questionnaire. In this study, the authors use the terms awareness and knowledge interchangeably (14).

A responder was deemed to have a favorable attitude if they were able to correctly respond to at least 60% (but no more than 75%) of the attitude-related questions.

A respondent was deemed to have an unfavorable attitude if they were unable to correctly respond to at least 60% of the attitude-related questions (14).

A respondent was deemed to have good practice if they were able to execute at least 60% of the recommended measures for disease prevention and control.

A respondent was deemed to have poor practice if they were unable to execute at least 60% of the recommended behaviors for disease prevention and control (14).

For the quantitative component of this study, traditional healers and patients at traditional healing centers constituted the study units.

The study’s clients (exit interviewees) and all randomly chosen traditional healers were eligible for inclusion in the quantitative component of the study. Clients of conventional healing facilities who were mentally unfit for interviewing were disqualified from the quantitative portion of the study. A single-population proportion formula was used to calculate the required number of exit interviewees (clients of traditional healing centers) for the study’s quantitative phase. We took into account the aforementioned criteria:

Considering that there have been no prior studies conducted in the study environment, we assumed that 50% of patients seek medical care from traditional healing sites and healers, with a 5% margin of error and a 95% CI of certainty (alpha = 0.05).

where:

Z = Za1/2 value (1.96 for 95% CI)

p = prevalence (0.5 taking as decimal)

d = margin of error (0.05)

By including a 10% non-response rate, the result is: 10% × 384.16 = 38.416; 38.416 + 384.16 = ≈ 423.

First, using a straightforward random sample approach and lottery procedures, traditional healers and healing centers in the East Gojjam Zone were chosen. Seven districts—Hult Eju Enese, Awabel, Enarji Enawuga, Gozamin, Baso Liben, Dejen, and Debre Markos Town—were chosen in this step. Finally, for each traditional healing center that was randomly chosen, the study participants (traditional healers and their patients) were methodically chosen.

The following variables were considered within the quantitative component of the study: the knowledge and attitudes of healers and their patients toward local disease outbreaks and COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control; level of experience (in the prevention and control of local disease outbreaks and pandemics); sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., healer sex, client sex, client age, client family size, client household wealth index, and residential setting (urban/rural); facility/site (indigenous/traditional healing sites)-related factors; geographical location (Kola Diba/Dega); and distance and shelter.

A semistructured questionnaire was used to collect data from traditional healers and their patients for the quantitative part of the study. The context and preceding articles were used to design the questionnaire. Using a semistructured questionnaire for face-to-face interview, and an in-depth interview guide for the sessions, data from specifically selected traditional healthcare professionals (of all types), local public health facility leaders, religious leaders, and clients of traditional healing centers were gathered for the qualitative portion of the study.

Prior to our interviewing participants, we conducted pre-tests on non-study, control participants (who comprised 5% of the participants recruited) from the Enemay district to ensure the tool’s suitability. Throughout the data collection period, the questionnaire responses were continually reviewed for completeness.

Data were cleaned, entered into the software EpiData™ version 6.0, and then exported to Stata™, version 14, analysis software. Frequency tables and graphs are used to display the descriptive statistics.

The term “traditional healer” refers to those practitioners (other than religious healers—described below) who provide any health and health-related healing services using their indigenous knowledge, and who are registered with an appropriate body. In this study, the term “religious healers” refers to religious leaders who provide healing services either at or near to religious institutions, such as those who provide healing services at holy water sites.

For the qualitative component of the study, clients of traditional healing centers, local public health facility leaders, religious leaders, and trained healthcare personnel (of all types) were purposefully chosen as research participants in the focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews (IDIs). A total of 18 IDI interviewees and one FGD interviewee, together with eight group discussants, made up the sample. The technique of purposive sampling was used for the qualitative portion.

Using a semistructured questionnaire and an in-depth interview guide, data from methodically selected trained healthcare professionals (of all types), local public health facility leaders, religious leaders, and clients of traditional healing centers were gathered for the qualitative portion of the study.

An amalgam of story and content analysis was used for the qualitative portion of the study.

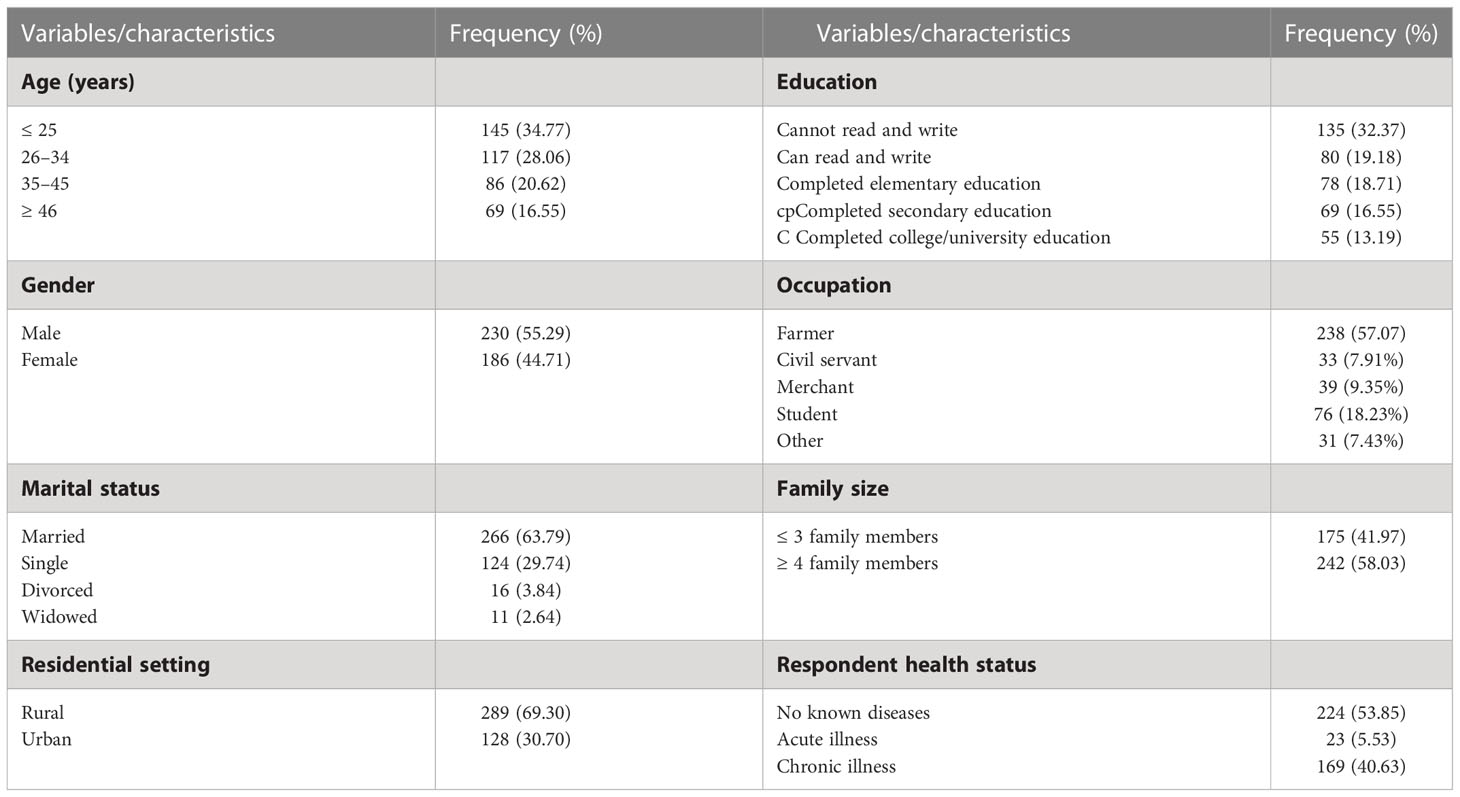

A total of 417 study participants were included in the quantitative portion of this study, with a response rate of 98.58%. The majority (55.29%) of study participants were men. The majority of respondents (69.30%) called rural areas home. The majority (266; 63.79%) of study participants were married. Only 13.19% of respondents had a college or university degree, whereas 32.37% lacked any kind of formal education (Table 1).

Table 1 Descriptive results of sociodemographic characteristics of respondents in the East Gojjam Zone, 2021.

Only 64.27% (95% CI 59.53% to 68.74%) of respondents exhibited good awareness of the preventive and control strategies employed in response to local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic. Recognizing transmission routes, taking preventive action, and being aware of the symptoms of each disease and the COVID-19 pandemic are among these.

Only 9.59% of respondents had a favorable attitude toward local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic (95% CI 7.11% to 12.83%). By contrast, roughly 47.72% of respondents held the belief that regional disease outbreaks, and the COVID-19 pandemic, were punishments from God. In addition, 26.38% of respondents believed that local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic are part of a secret plot.

In addition, this study revealed that only a small percentage of study participants (i.e., 2.16%) actually followed the recommended control and preventive guidelines for the COVID-19 pandemic and local disease outbreaks. In traditional healing centers, 10.79% of participants reported wearing masks, and about one in eight (13.91%) still maintained physical distancing. Nearly three-quarters (70.02%) of those surveyed said that they were washing their hands after toileting to prevent contracting cholera.

Fifteen individuals, with a mean age of 46 years, ranging from 31 to 67 years, participated in IDIs.

Based on the objectives of this study, six themes were identified, which are detailed below.

In this theme, a higher proportion of the in-depth interviewees and focused group discussants had an awareness of indigenous knowledge (FGD discussant 2; IDI interviewee 8). They also said that “ሀገር በቀል እውቀት ማለት ከትውልድ ትውልድ ሲተላለፍ የኖረ ትኩረት ሊሰጠው የሚገባ ጥበብ ነው፤የኢትዮጵያ ኦርቶዶክስ ተዋህዶ ቤተክርስቲያን ደግሞ ይህንን ጥበብ ጠብቃ የቀየች ነች:: sic]”

Regarding the level of knowledge toward local disease outbreaks, and the COVID-19 pandemic and its conventional prevention and controls measures, a few of the IDI interviewees and FGD discussants recognized that local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic have their own biomedical causes (FGD discussant 3, health professional; IDI interviewee 4, traditional healer). Conversely, a majority of participants believed that local disease outbreaks, and the COVID-19 pandemic, were punishments from God (e.g., FGD discussant 5, religious healer; IDI interviewee 14, religious healer).

In-depth interviewees had variable understanding of local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic, and of the conventional preventive and control measures employed in response to these; however, most of these measures were not being accessed significantly at healing sites. This avoidance may be related to their beliefs on the cause of local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The majority of IDI participants felt that prayer to God was the best way to stop the spread of local diseases and the virus causing COVID-19. As well as religious healers, traditional healers who participated in IDIs reported carrying out their regular tasks at their healing centers because they had strong spiritual convictions and senses of good and evil. However, several people who participated in IDIs attempted to stop the spread of local diseases and the virus causing COVID-19 using their native knowledge and the healing abilities of their native species as reflected in the following quotation: “ለሚመለከተው የመንግስት አካል ለኮቪድ መድሃኒት ይሆናሉ ያልናቸውን ሰርተን አቅርበን ነበር ግን አበረታች መልስ አልተሰጠንም [sic]” (IDI interviewee 8, traditional healer; IDI interviewee 4, traditional healer). They said, “We also adhere to outbreaks and COVID-19 pandemic, and we provide health education regarding personal cleanliness.”

Some respondents expressed that there were significant efforts to apply indigenous and modern knowledge to tackle COVID-19 and other disease outbreaks at traditional healing centers. However, much work is required from both traditional healers and the government to further these efforts.

One IDI interviewee, interviewee 5, who is a religious healer, elaborated that at religious healing sites and within the church for routine religious deeds where rituals or activities are commonly practiced, “The Church possesses a great deal of wisdom; according to the Bible, it would burn incense during an epidemic, which would ward off evil spirits and prevent epidemics.” He added that “ቤተ ክርስቲያን ለፀበል የሚመጡ ምመናን ንህናቸውን እንዲጠብቁ ታስተምራለች. [sic]”

The obstacles to the prevention and containment of COVID-19 and other diseases that were brought up most frequently by traditional and religious healers were the lack of assistance from local healthcare institutions and the health administration; an inadequate licensing system, particularly for traditional healers; and a lack of suitable healing and childcare facilities. Other issues raised by respondents included traditional healers’ low commitment to utilizing their native knowledge for the benefit of the public’s health, misconduct on the part of some traditional healers, mistrust of traditional healers by health professionals, and mistrust between traditional healers and clients. One respondent stated that “despite some attempts to work in integration and harmony, still there is low emphasis on traditional healers.”

Respondents offered potential strategies for enhancing the responsibilities of traditional healers, healing centers, and employing indigenous knowledge to ultimately prevent and control disease outbreaks/pandemics and improve community health. Focus group participants and IDI interviewees draw the following conclusion: “First, there shall be an appropriate licensing procedure for traditional healers, on the other hand, the healer must be devoted to the advancement of his or her healing practices, and finally, there shall be cooperation between traditional healers and health professionals for the well-being of the community; furthermore, there should be unreserved support for traditional healers and healing sites to maximize their role in outbreaks and pandemics” (FGD discussants 1, 2, 4, and 15; IDI interviewees 10 and 15).

With a focus on traditional healers and healing sites in the East Gojjam Zone, this mixed-methods study was carried out to evaluate the roles and difficulties of applying indigenous knowledge to prevent and control local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly two-thirds (64.27%, 95% CI 59.53% to 68.74%) of quantitative survey participants had a decent understanding of local disease outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the prevention and containment of both.

The respondents’ attitudes to local disease outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the preventive efforts employed in response to these were another significant finding of this study. The findings of this study revealed that traditional healers and their patients in the East Gojjam Zone of the Amhara regional state of northwestern Ethiopia have very poor attitudes overall concerning local disease outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the preventive measures employed in response to both. Only 9.59% (95% CI 7.11% to 12.83%) of survey respondents had a favorable view toward local disease outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the preventive measures employed in response to both. This result is lower than the findings of a study conducted in Gondar, which found that approximately 15.6% (n = 29) of traditional healers and religious authorities had a favorable attitude toward preventative and containment measures employed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (14). The disparity in the findings might be due to the geographical difference of the study areas.

In addition, this study found little awareness about local disease outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the preventive measures employed in response to both among patients of traditional healers in the East Gojjam Zone. Only a small percentage of research participants (i.e., 2.16%), according to the results, used the standard controls and preventive measures for the COVID-19 pandemic and local disease outbreaks.

Despite many difficulties and limitations, traditional healers and healing sites have played a dual role in preventing and controlling local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the thematic analysis of the study’s qualitative data. In addition to offering their clients health education about conventional preventive and control methods for local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic, they provide traditional healing services using their indigenous knowledge for people suffering from acute and chronic sicknesses.

Despite efforts, there remain many obstacles to optimization of the contributions of conventional healers and healing centers to the prevention and control of local disease outbreaks and the COVID-19 pandemic. Barriers cited frequently in religious healing sites include structural-related issues, mistrust among stakeholders, misconduct among traditional healers, minimal support from local government entities, improper licensing, a lack of suitable working spaces, and inadequate housing and other facilities.

Close to two-thirds of respondents had a greater awareness or good knowledge of regional outbreaks and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Less than 10% agreed with the current COVID-19 pandemic’s preventive and control measures and retained positive attitudes regarding outbreaks/pandemics. More specifically, approximately 5% of participants thought that the COVID-19 pandemic and local outbreaks of disease were punishments from God. Only a small percentage of research participants employed effective preventive strategies in response to these, the study also revealed.

Low levels of involvement of traditional healers and healing sites in the prevention and control of local disease outbreaks and the current COVID-19 pandemic, despite their contributions to community health education and healing using their indigenous knowledge, could explain the unfavorable attitudes toward conventional disease preventative and control measures, and low practice of these measures, by traditional healers and their patients.

Structural issues, mistrust between parties, unethical behavior on the part of some traditional healers, a lack of local government support, improper licensing, inadequate shelter, and a lack of suitable working spaces and other facilities in religious healing sites were among the frequently cited explanations for the low, or lack of, contributions of traditional healers and healing centers and sites in the prevention and control of local disease outbreaks and the current COVID-19 pandemic in the study areas.

Based on the study’s findings, it is advised that:

A. To prevent the misuse and abuse of indigenous knowledge, local and regional governments should strengthen licensing requirements for traditional healers.

B. Traditional healers should develop their relationships within the community’s medical centers and governing bodies and collaborate with them, if they are to play an integral role in the prevention and containment of local disease outbreaks and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

C. Local healthcare providers and facilities must place adequate emphasis on these locations and offer health education about local disease outbreaks and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

D. In addition to following the advice of traditional healers, patients at healing centers should follow established preventive and control measures for local disease outbreaks and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Haddis Alemayehu Institute of Cultural Studies. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This research was funded by the Haddis Alemayehu Institute of Cultural Studies at Debre Markos University. Hence, the authors would like to thank the Haddis Alemayehu Institute of Cultural Studies at Debre Markos University for fully funding this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer MM declared a shared affiliation with the authors to the handling editor at the time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. World Health. WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. World Health Organization (2019).

2. Jacobsson L. Traditional treatment of mental and psychosomatic disorders in Ethiopia. In: International congress series. Elsevier (2002).

3. Mengel MA, Delrieu I, Heyerdahl L, Gessner BD. Cholera outbreaks in africa. cholera outbreaks. Springer (2014) p. 117–44.

4. Lin Q, Zhao S, Gao D, Lou Y, Yang S, Musa SS, et al. A conceptual model for the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in wuhan, China with individual reaction and governmental action. Int J Infect Dis (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.058

5. World Health Organization. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on non-communicable disease resources and services: results of a rapid assessment. World Health Organization (2020).

6. Estifanos AS, Alemu G, Negussie S, Ero D, Mengistu Y, Addissie A, et al. I Exist because of we’: shielding as a communal ethic of maintaining social bonds during the COVID-19 response in Ethiopia. BMJ Global Health (2020) 5(7):e003204. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003204

7. Burke A, Wong Y-Y, Clayson Z. Traditional medicine in China today: implications for indigenous health systems in a modern world. Am J Public Health (2003) 93(7):1082–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1082

8. Srinivasan P. National health policy for traditional medicine in India. World Health Forum (1995) 16(2):190–3.

9. Jones J. Ebola, Emerging: the limitations of culturalist discourses in epidemiology. J Global Health Columbia Univ (2011) 1(1):1–6. doi: 10.7916/thejgh.v1i1.4924

10. Okeke T, Okafor H, Uzochukwu B. Traditional healers in Nigeria: perception of cause, treatment and referral practices for severe malaria. J Biosocial Sci (2006) 38(4):491. doi: 10.1017/S002193200502660X

11. Makundi EA, Malebo HM, Mhame P, Kitua AY, Warsame M. Role of traditional healers in the management of severe malaria among children below five years of age: the case of kilosa and handeni districts, Tanzania. Malaria J (2006) 5(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-58

12. Abdela SG, Berhanu AB, Ferede LM, Griensven Jv. Essential healthcare services in the face of COVID-19 prevention: Experiences from a referral hospital in Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hygiene (2020) 103(3):1198–200. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0464

13. Birhan W, Giday M, Teklehaymanot T. The contribution of traditional healers' clinics to public health care system in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed (2011) 7(1):39. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-7-39

14. Asmelash D, Fasil A, Tegegne Y, Akalu TY, Ferede HA, Aynalem GL. Knowledge, attitudes and practices toward prevention and early detection of COVID-19 and associated factors among religious clerics and traditional healers in gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A community based study. Risk Manage Healthcare Policy (2020) 13:2239. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S277846

Keywords: roles, challenges, traditional healers, outbreaks, Amhara, Ethiopia

Citation: Gietaneh W, Simieneh MM, Endalew B, Tarekegn S, Petrucka P and Eyayu D (2023) Traditional healers’ roles, and the challenges they face in the prevention and control of local disease outbreaks and pandemics: The case of the East Gojjam Zone in northwestern Ethiopia. Front. Trop. Dis. 4:978528. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2023.978528

Received: 26 June 2022; Accepted: 03 January 2023;

Published: 03 February 2023.

Edited by:

Delia Bandoh, Ghana Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme, GhanaReviewed by:

Ritu Amatya, Family Health International, NepalCopyright © 2023 Gietaneh, Simieneh, Endalew, Tarekegn, Petrucka and Eyayu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wodaje Gietaneh, d29kYWplX2dpZXRhbmVoQGRtdS5lZHUuZXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.