95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Trop. Dis. , 23 January 2023

Sec. Neglected Tropical Diseases

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2022.1059283

This article is part of the Research Topic Highlights in Vector Biology View all 8 articles

The Zika virus (ZIKV) is a vector-borne flavivirus that has been detected in 87 countries worldwide. Outbreaks of ZIKV infection have been reported from various places around the world and the disease has been declared a public health emergency of international concern. ZIKV has two modes of transmission: vector and non-vector. The ability of ZIKV to vertically transmit in its competent vectors, such as Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, helps it to cope with adverse conditions, and this could be the reason for the major outbreaks that occur from time to time. ZIKV outbreaks are a global threat and, therefore, there is a need for safe and effective drugs and vaccines to fight the virus. In more than 80% of cases, ZIKV infection is asymptomatic and leads to complications, such as microcephaly in newborns and Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) in adults. Drugs such as sofosbuvir, chloroquine, and suramin have been found to be effective against ZIKV infections, but further evaluation of their safety in pregnant women is needed. Although temoporfin can be given to pregnant women, it needs to be tested further for side effects. Many vaccine types based on protein, vector, DNA, and mRNA have been formulated. Some vaccines, such as mRNA-1325 and VRC-ZKADNA090-00-VP, have reached Phase II clinical trials. Some new techniques should be used for formulating and testing the efficacy of vaccines. Although there have been no recent outbreaks of ZIKV infection, several studies have shown continuous circulation of ZIKV in mosquito vectors, and there is a risk of re-emergence of ZIKV in the near future. Therefore, vaccines and drugs for ZIKV should be tested further, and safe and effective therapeutic techniques should be licensed for use during outbreaks.

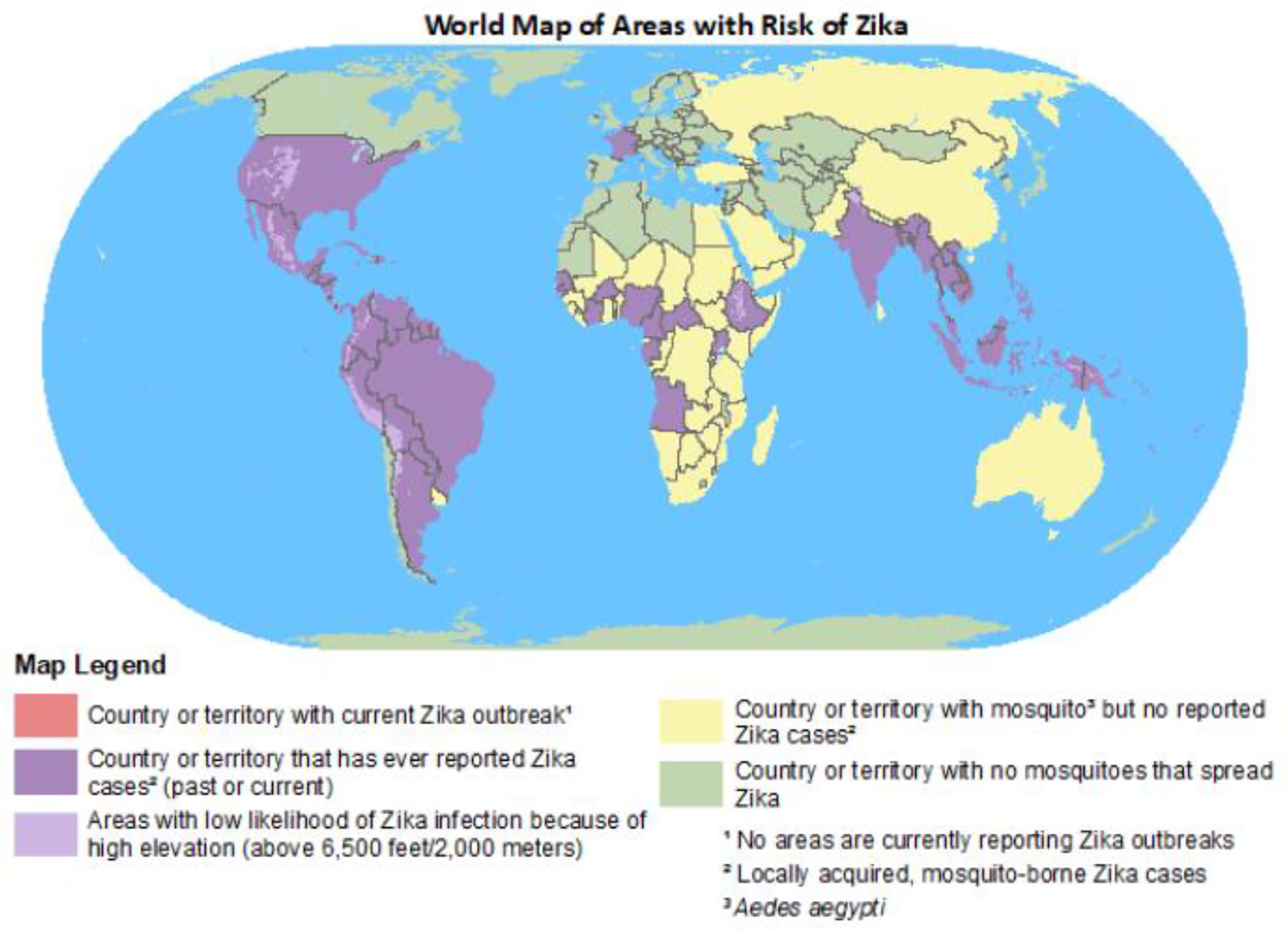

The Zika virus (ZIKA) has affected about 87 countries worldwide since 2019, especially countries in tropical and subtropical regions (1). ZIKA is a Flavivirus, having a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA encoding for three structural proteins [i.e., precursor membrane protein (prM), capsid protein (C), and envelope protein (E)] and seven non-structural proteins (i.e., NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) (2). In 1950, the first case of human infection with ZIKA was reported in Africa. In 2016, the WHO declared ZIKA infection a public health emergency of international concern (3). ZIKV is found in several WHO regions (i.e., the African Region, Region of the Americas, South-East Asia Region, and the Western Pacific Region) (4). Recently, in India in 2021, a total of 150 cases of ZIKV infection were reported. Most patients were asymptomatic or had a mild fever (5). Figure 1 shows the regions at risk of ZIKV infection.

Figure 1 World map of areas at risk of ZIKV (6).

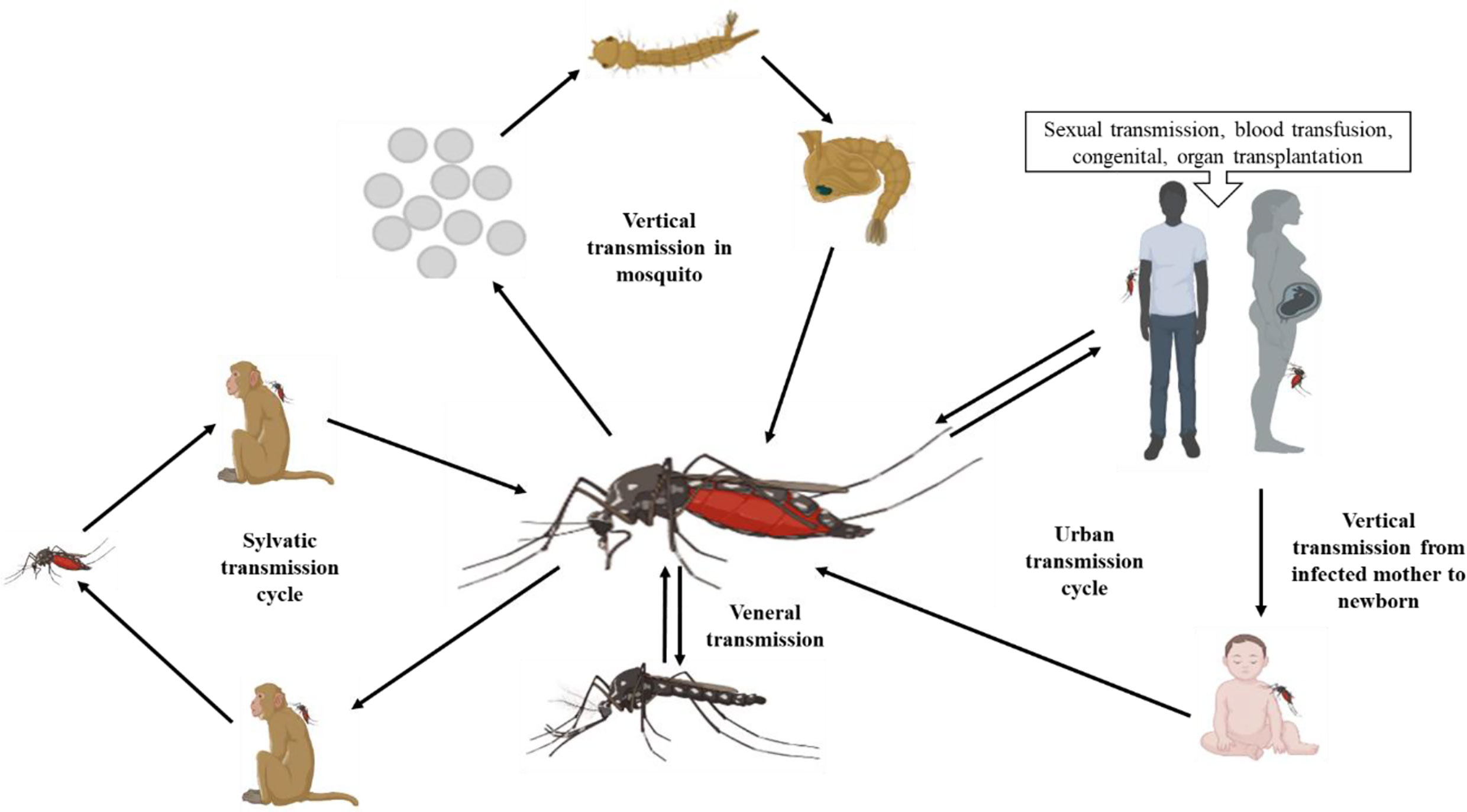

The Zika virus mainly spreads through an Aedes mosquito bite, but can also spread by non-vector transmission, for example by congenital transmission, blood transfusion, organ transplantation, sexual transmission, and vertical transmission (4). The vertical transmission capacity of ZIKV has been studied in Aedes mosquitoes, and vertical transmission has been found to help ZIKV to cope with harsh conditions (7). ZIKV is an arbovirus that is transmitted by two cycles: a sylvatic cycle involving transmission between non-human primates and arboreal insects in forests, and an urban cycle between humans and urban mosquitoes (8). The ZIKV transmission cycle is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Transmission modes of ZIKV (created with BioRender.com).

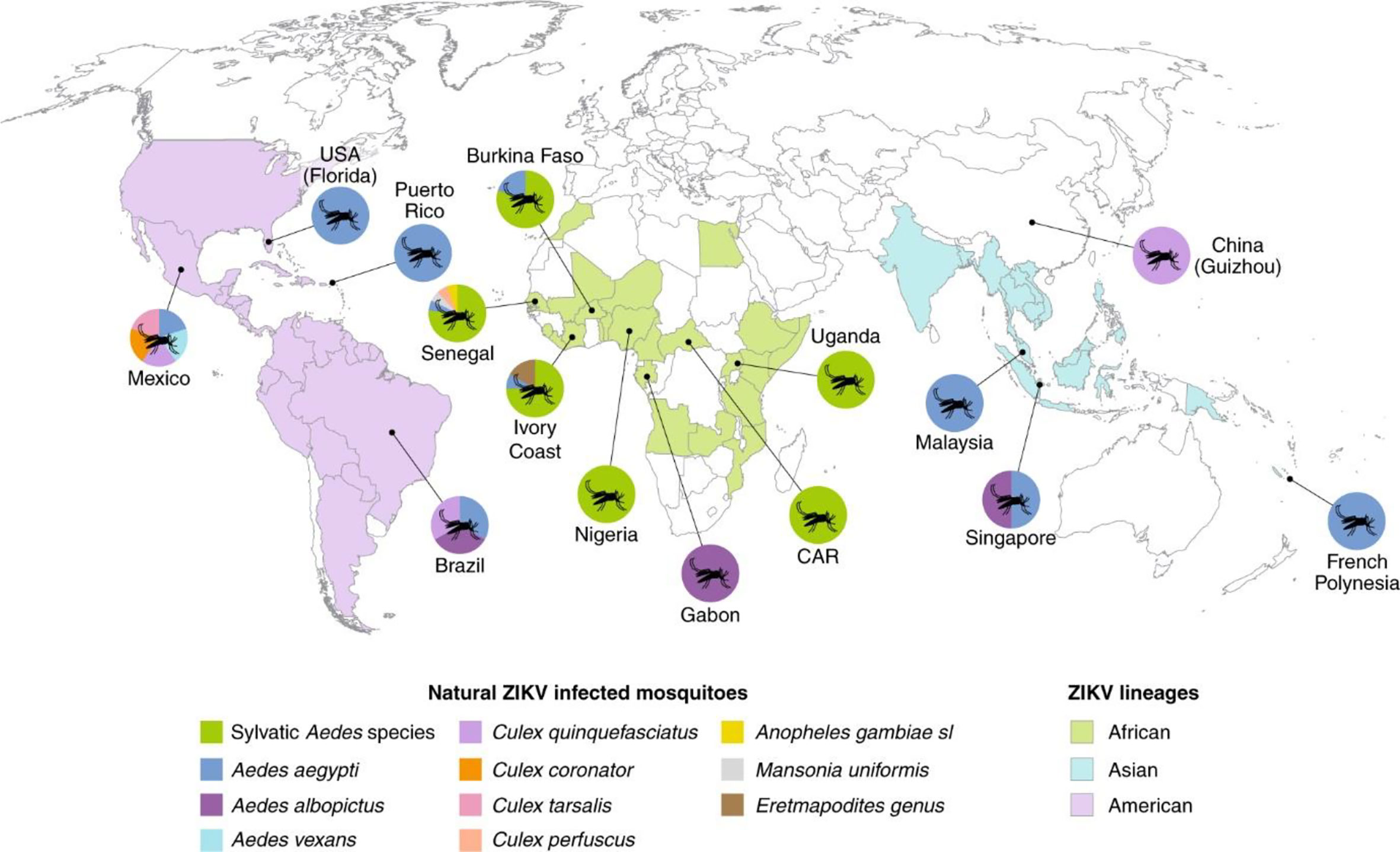

In Asian and African mosquitos, Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, Ae. vexans, Ae. (Rampamyia) notoscriptus, Ae. (Ochlerotatus) camptorhynchus, Ae. vittatus, Ae. luteocephalus, and Culex quinquefasciatus act as potential vectors (9, 10). Anopheles gambiae, A. stephensi, and Cx pipiens have also been shown to be probable vectors (11). Ae. (Stegomyia) hensilli and Ae. (Stegomyia) polynesiensis were found to be probable vectors during the ZIKV outbreak in Yap Island and French Polynesia (12). Vectorial capacity (i.e., vector-borne transmission ability) is affected by the ecological traits and abundance of vectors, and poor vectors with limited vector competence can lead to outbreaks worldwide (10, 13). Del Carpio et al. (2018) revealed that in Mexico a variety of species of Culicidae were present. In Mexico, Ae. Aegypti and Ae. albopictus, A. species such as A. albimanus and A. pseudopunctipennis, and Culex family members, such as Cx perfuscus, Cx pipens, and Cx quinquefasciatus, act as potential vectors during outbreaks. However, some mosquito species endemic to Mexico, for example, Ae. sumidero, Ae. tehuantepec, Ae. guerrero, Ae. ramirezi, Ae. laguna, Ae. cozumelensis, Cx jalisco, Cx sandrae, Cx schicki, Cx arizonensis, and A. aztecus, could act as a vector in the absence of potential vectors. In America, the Culicidae family is highly diversified and competes with Aedes species for being a potential vector to transmit ZIKV (14). A comprehensive assessment of vector competency in Brazil concluded that Aedes species can cause a pandemic in the absence of arboviral-specific vectors, such as Ae. Aegypti, while other species like Ae. albopictus or Ae. japonicus can act as potential vectors for arboviruses (15). The distribution of probable vectors is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Distribution of vector species infected with ZIKV (10).

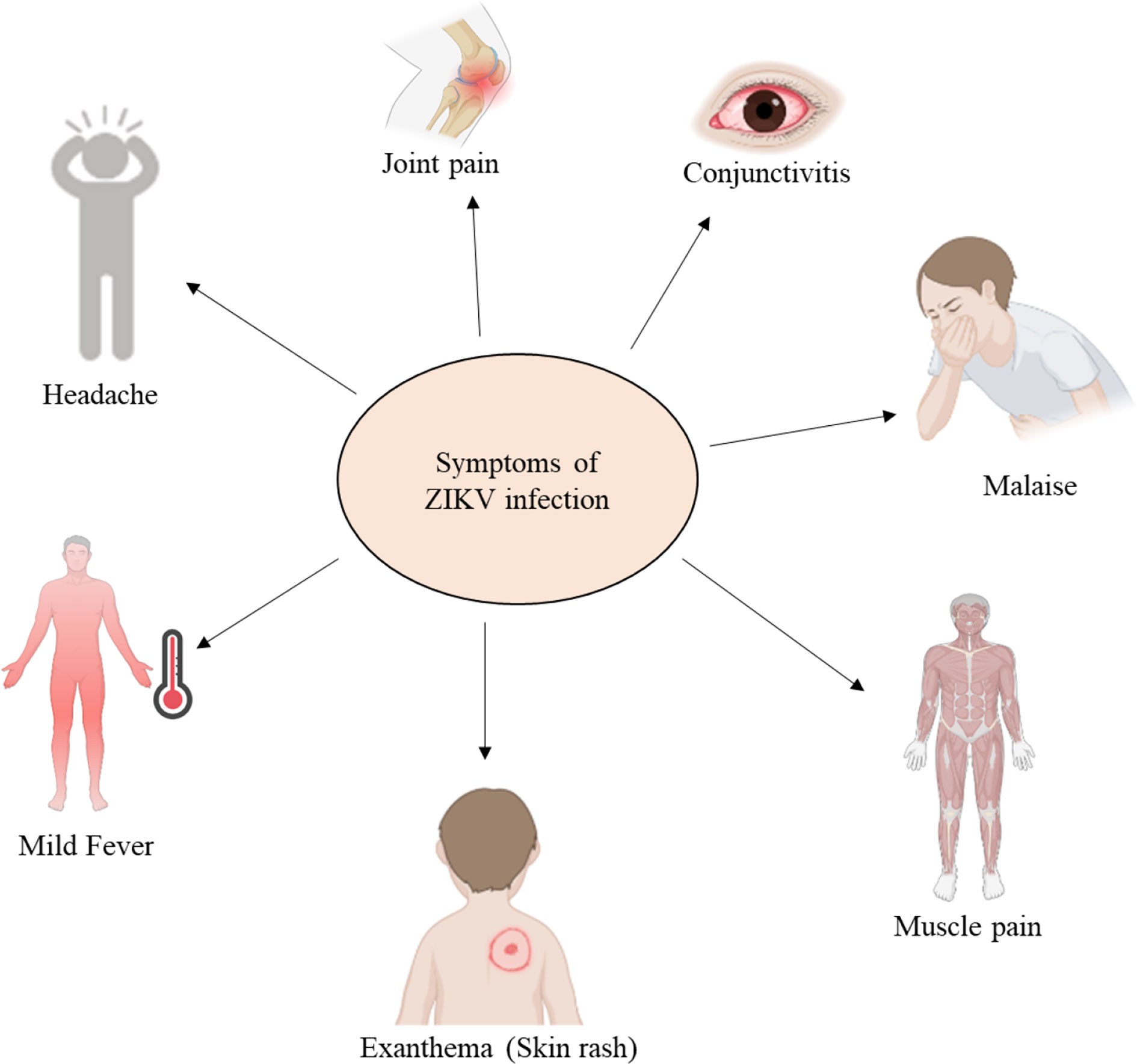

The incubation period of ZIKV is approximately 3–14 days. The majority of people, ≈80%, do not show any symptoms of infection. Symptoms that are observed in 20%–25% of ZIKV patients with an acute infection include joint pain, conjunctivitis, malaise, muscle pain, headache, fever, and rash, as shown in Figure 4. These symptoms generally last for 2–7 days (1).

Figure 4 Common symptoms of an acute ZIKV infection (created with BioRender.com).

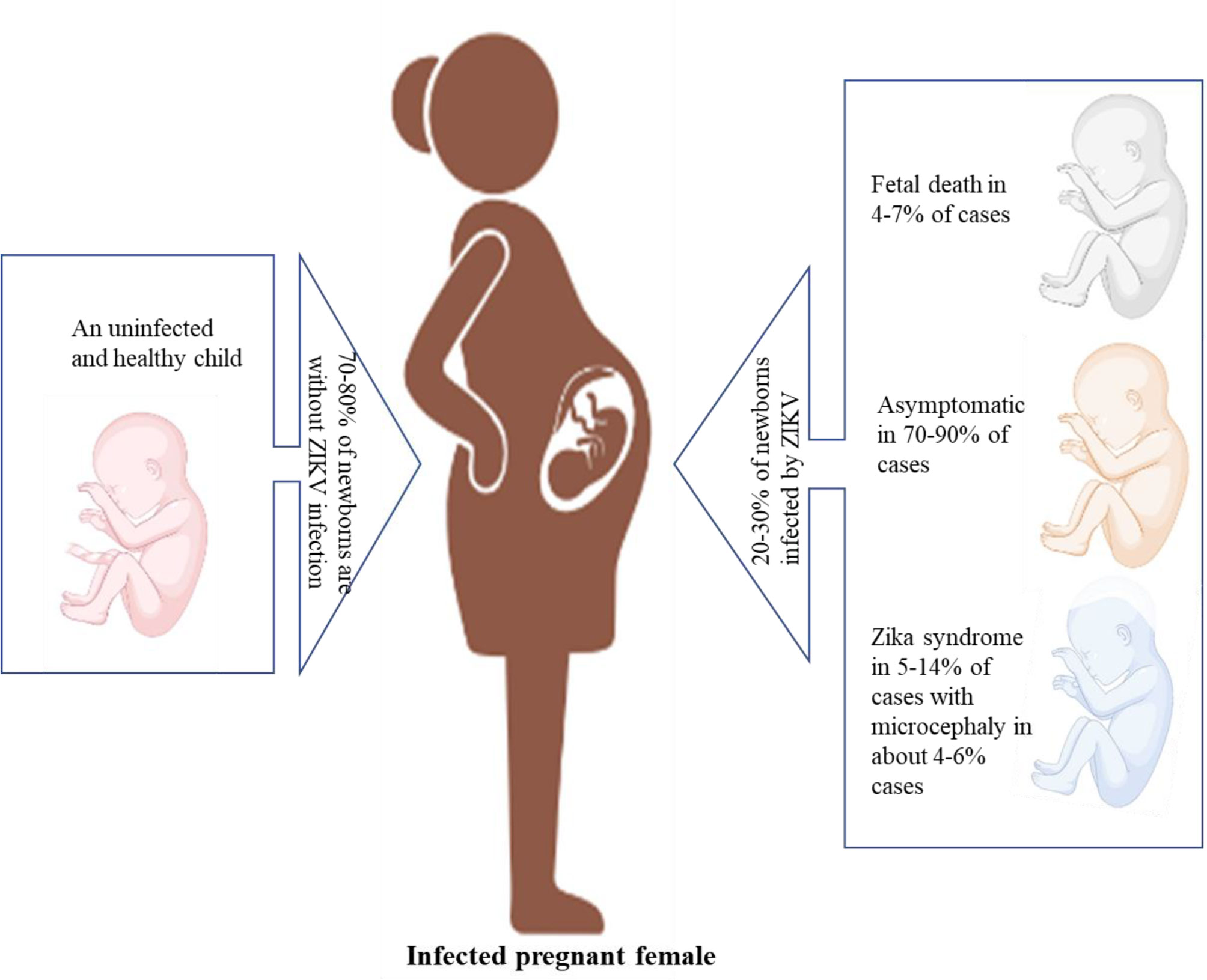

ZIKV infection during pregnancy can result in fetal loss, stillbirth, and preterm birth. In newborns, ZIKV can cause congenital abnormalities such as microcephaly (16). ZIKV infection also triggers myelitis, Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), and neuropathy in adults and older children (1). The complications, such as microcephaly, are shown in Figures 5, 6.

Figure 5 Different complications observed during pregnancy due to ZIKV infection (created with BioRender.com).

Figure 6 Microcephaly observed in newborns (www.cdc.gov.in).

Acute ZIKV infection is self-limiting, and patients recover, but the matter of serious concern is neonatal complications, which are associated with chronic ZIKV infection. In 2015, during a ZIKV outbreak in Brazil, the number of cases of newborns with microcephaly increased (17). Complications such as optic neuropathy, glaucoma, lissencephaly, microcephaly, and ventriculomegaly are also associated with ZIKV infection, as ZIKV mRNA was observed in the amniotic fluid of pregnant women (18). ZIKV infection in pregnant women has been shown to be harmful to fetuses. In the first and second trimesters of pregnancy, ZIKV infection can have severe effects, such as spontaneous abortion, congenital abnormalities, and fetal death, or necessitate therapeutic abortion due to congenital malformation. Congenital abnormalities such as microcephaly, hydrocephalus, hypoplasia, hypertonicity, cerebellar calcification, and seizures related to the neurological system, osteoskeletal system abnormalities, such as arthrogryposis and clubfoot, and optic system abnormalities, such as ophthalmic changes in the posterior and anterior segments, and abnormal visual functions, were observed in neonates with the help of image tests (19). An acute infection of ZIKV may lead to GBS. GBS is an autoimmune condition in which gradual muscle weakness, reduced nerve function, and paralysis are observed as myelinated neural cells are attacked by cell-mediated immunity (20, 21). In French Polynesia, during a ZIKV outbreak in 2013–14, cases of GBS increased 20-fold, and a close relationship was seen between the manifestation of ZIKV and GBS (20). In other studies, it has been reported that the prevalence of GBS with ZIKV is 42% and 24% in Brazil and America, respectively. The variations in prevalence, which have been reported, may be due to the reduced incidence as a result of the low virulence and pathogenicity of the virus. Other GBS-causing agents include a species of Campylobacter and various arboviruses related to ZIKV (22, 23).

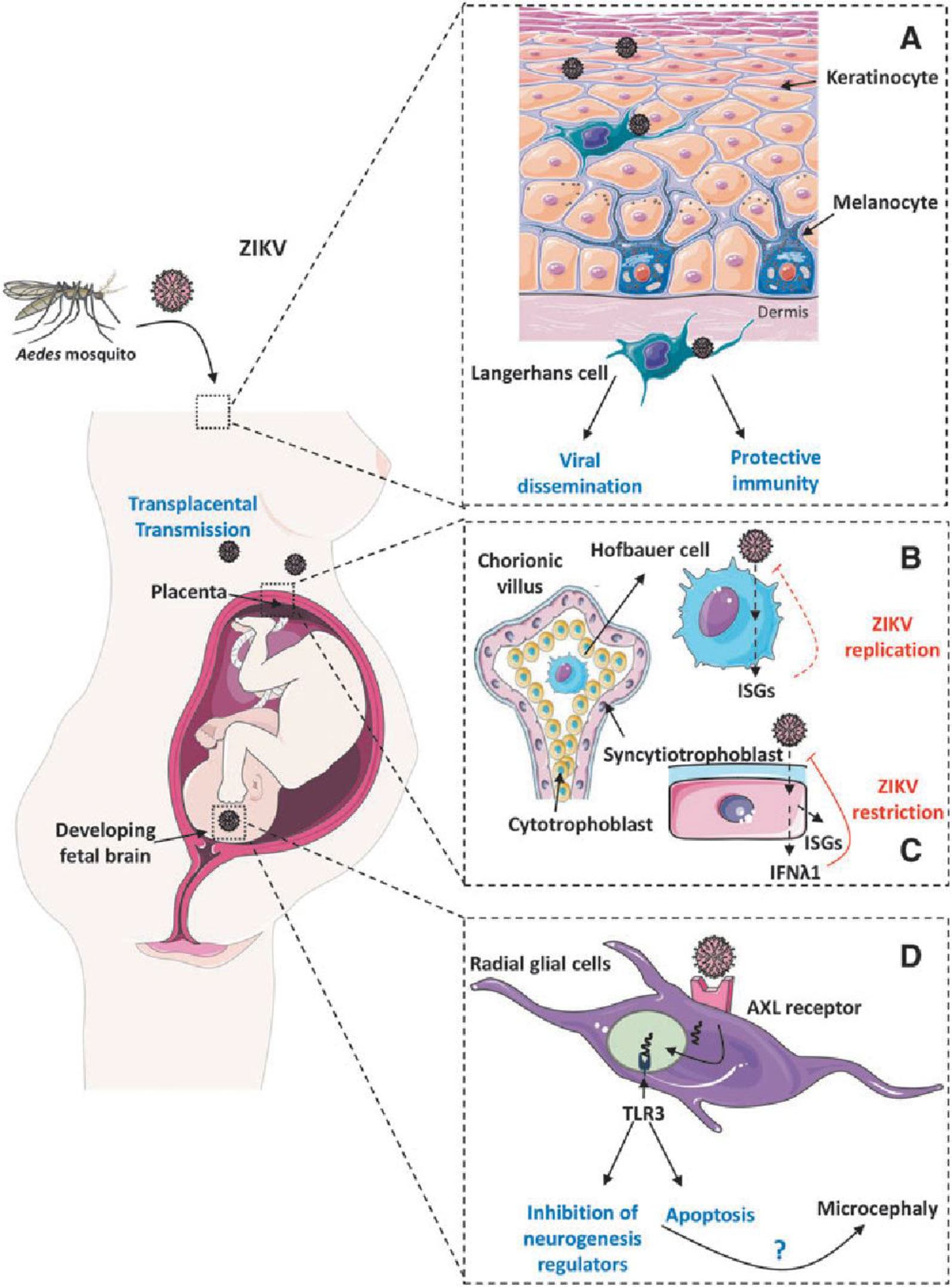

ZIKV infection leads to neuropathogenesis through various mechanisms, neuronal apoptosis of the immune response, an inflammatory response, and cell-cycle dysregulation (24). In many studies, it has been found that, during vertical transfer from an infected mother to a developing fetus, ZIKV can successfully infect human neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) (25). During the first trimester of pregnancy, hNPCs generate brain organoids and neurospheres for fetal brain development, but either hNPCs infected with ZIKV show a cytopathic effect and die, or the cytopathic effect is reduced by virus replication, leading to brain abnormalities such as microcephaly and restriction of fetal brain development (24, 26). It has been observed previously that cells with highly expressed Axl receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL) receptors are more susceptible to ZIKV infection (27). The AXL receptor mediates the ZIKV infection to keratinocytes and fibroblasts. The various cellular receptors known to be involved in ZIKV neuropathogenesis are dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN), phosphatidylserine receptor proteins, such as T-cell immunoglobulin mucin-1 (TIM-1), TIM-4, AXL, and tyrosine–protein kinase receptor 3 (TYRO3), and heat shock proteins (HSPs), glucose-regulating protein 78 (GRP78/BiP), and a cluster of differentiation (CD) 14-associated molecules (28–30). In addition, ZIKV interacts with toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and induces an interferon response. ZIKV has to overcome the innate immune barrier by degrading the signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 (STAT2) (2). It has been found that silencing of the AXL gene up-regulates type I interferon signaling, indicating that AXL helps in increasing ZIKV infection by down-regulating type I interferon signaling (31). Recent studies have revealed that ZIKV infection is not solely dependent on AXL, limiting the possibility of developing any therapeutics (32). The vertical transmission and neuropathogenesis mechanism of ZIKV infection in humans is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7 ZIKV infection mechanisms and neuropathogenesis (ISGs, interferon-stimulated genes; ZIKV, Zika virus) (33). (A) Infection of ZIKV in dermatocytes, (B) Infection of ZIKV in hofbauer cells, (C) Protective immune response of syncytiotrophoblast, (D) ZIKV targeting neural progenitor cells.

Aedes mosquitoes are the probable vector for ZIKV transmission. Figure 7A shows how ZIKV can infect dermal fibroblasts and epidermal keratinocytes, which might then spread the virus to dermal dendritic cells (also known as Langerhans cells) and aid the spread of ZIKV. Figure 7B shows how infection of cytotrophoblasts or transmigration of infected primary human placental macrophages (Hofbauer cells) may result in the transplacental transfer of ZIKV to the fetus, indicating a unique pathway for intrauterine transmission. Hofbauer placental macrophages release type I IFN and increase interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in response to ZIKV infection, but the cells still allow ZIKV replication. Figure 7C shows how the placental syncytiotrophoblasts’ production of IFN-λ1 and ISGs during the later stages of pregnancy may have protective effects that prevent ZIKV infection. Figure 7D shows how ZIKV specifically targets neural progenitor cells during the embryonic brain’s development in first trimester. The entry of ZIKV into brain cells may be significantly influenced by the TAM receptor AXL. Deregulation of genes involved in neuronal development and apoptosis brought on by ZIKV-dependent activation of TLR3-mediated immune responses leads to significant damage to the embryonic brain, including microcephaly (33).

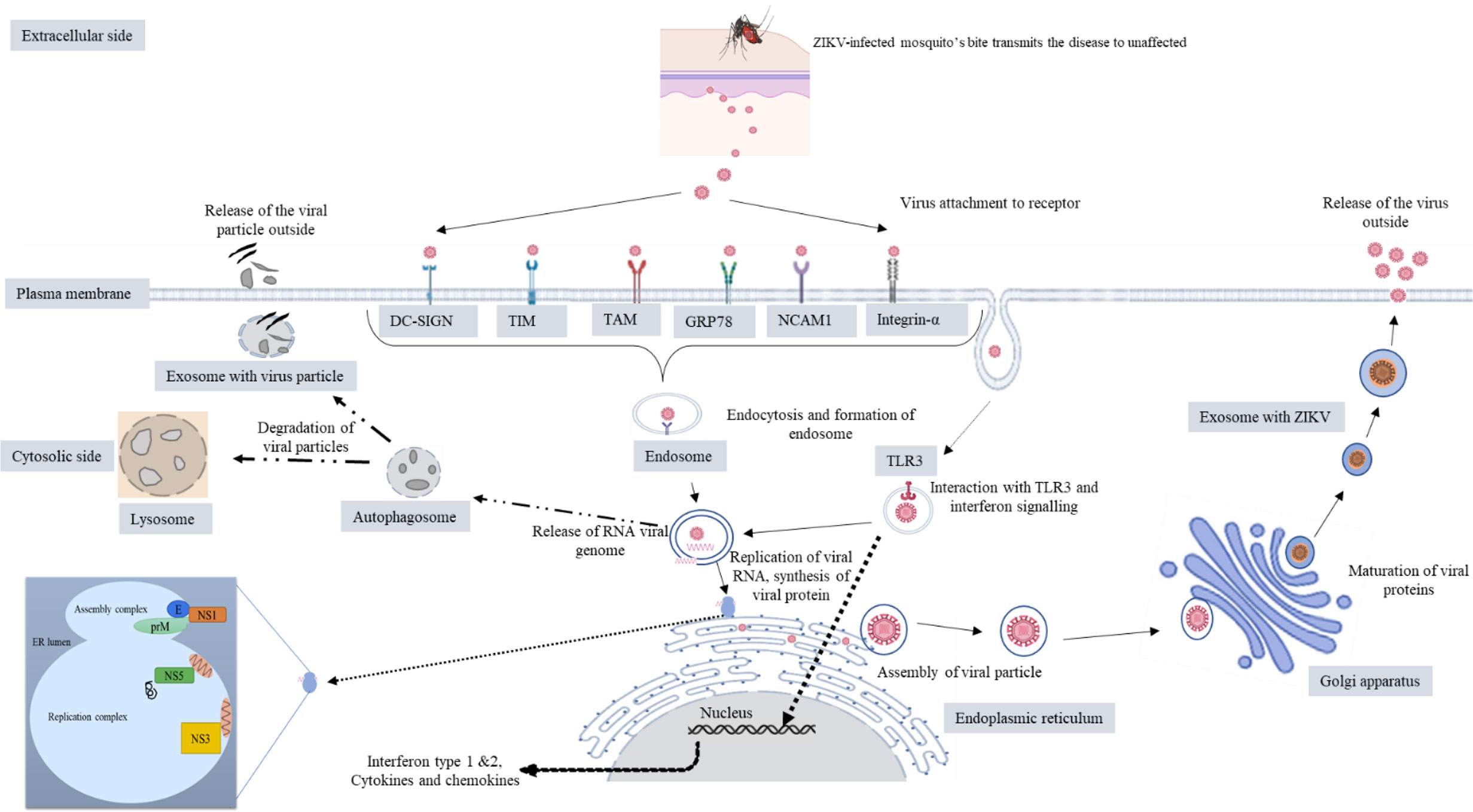

ZIKV presumably enters the cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis (28). The endocytosis is either clathrin or receptor mediated. A fusion between the virus and the host cell occurs because of the acidic environment and genomic RNA released inside the host cell. After its release, viral RNA is translated to the polyprotein in the vicinity of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with the help of viral-encoded proteins and the host. Later, viral replication and packaging occur on the surface of ER of the host cell. Furin-mediated cleavage occurs at the Golgi complex, resulting in the formation of a mature virus. Virus particles are released with the help of exocytosis, and ZIKV activates a TLR3-mediated immune response and autophagy pathway (34, 35). This may mediate viral survival and replication inside the cell, and then exosomes containing the ZIKV proteins are released by the infected cells (36). ZIKV may activate the unfolded protein response pathway, which may lead to cell death, DNA repair, or homeostasis (37, 38). The cellular mechanism of ZIKV is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8 Cellular mechanism of ZIKV (created with BioRender.com).

It is difficult to diagnose ZIKV infections because in more than 80% of cases ZIKV is asymptomatic. The symptoms of ZIKV infection overlap with those of infection with other flaviviruses. To date, five serological assays and 14 molecular diagnostics tests (Table 1), based on serum, saliva, and urine samples collected from patients, have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (39). In the case of individuals whose symptoms started within the previous 7 days, ZIKV infection can be diagnosed by subjecting whole blood or serum to an RT-PCR (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) test known as nucleic acid testing (NAT). Enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), immunofluorescence assays (IFAs), and neutralization assays, such as plaque-reduction neutralization tests (PRNTs), are crucial serological diagnostic tools, nonetheless, and should be used in individuals with symptoms that have persisted for more than 7 days (40). Serological assays should be interpreted carefully, as cross-reactivity between dengue and ZIKV antibodies may lead to misidentification of the causative agent, and prior exposure may also give false-positive results. Thus, serological assays alone cannot confirm ZIKV infection (41). Quantitative reverse transcription is used in in vitro diagnostics (IVDs). The most accurate molecular diagnostic method for ZIKV is PCR (i.e., qRT-PCR); however, due to its high cost and mobility issues, its use as a point-of-care (POC) test during monitoring programs is constrained (42). Instead, because of their low cost and simple logistical handling, reverse transcription loop-mediated amplification (RT-LAMP) and microfluidic cassettes are more popular (40, 43). Pregnant women with ZIKV infection living in endemic areas and with a history of clinical illness should undergo routine ultrasound scans in early pregnancy to check for abnormalities or fetal malformation (44). In pregnant women, ZIKV infection should be diagnosed based on laboratory evidence. Detection of RNA in blood and urine confirms ZIKV infection, whereas detection by IgM testing may give a false-positive result because of prior infection (41).

As yet, no specific vaccine against ZIKV infection is available, and treatment includes symptomatic care, for example, plenty of water intake, rest, antipyretics, and analgesics (45). ZIKV vaccine development is the subject of extensive study and includes several vaccine types, e.g., DNA-based vaccines, subunit vaccines, inactivated vaccines, and live-attenuated vaccines (46). Some antiviral drugs are also prescribed against ZIKV. GBS can be treated by intravenous injection of immunoglobins (0.4 g/kg body weight daily for 5 days) and by plasma exchange (200–250 ml plasma/kg body weight in five sessions) (47).

A variety of methods have been used to find medications that can fight ZIKV infection. Despite the serious consequences for public health, there is presently no cure or medicine to prevent ZIKV infections. On the basis of mode of action, ZIKV antivirals can be classified into host-directing antivirals and direct-acting antivirals. Efforts to develop effective antiviral drugs have focused on drug repositioning, as this minimizes the number of clinical trial steps. The search for drugs suitable for repositioning has helped pregnant women and newborns to withstand the outbreaks of ZIKV (48, 49). Of the repositioning drugs listed in Table 2, only temoporfin can be given to pregnant women (49). The anti-ZIKV medications sofosbuvir, chloroquine, and suramin produced better outcomes because more experimental data were available for evaluation (48). To facilitate the search for and increase the chances of finding a suitable anti-ZIKV medicine, other medications’ effectiveness against ZIKV should also be assessed.

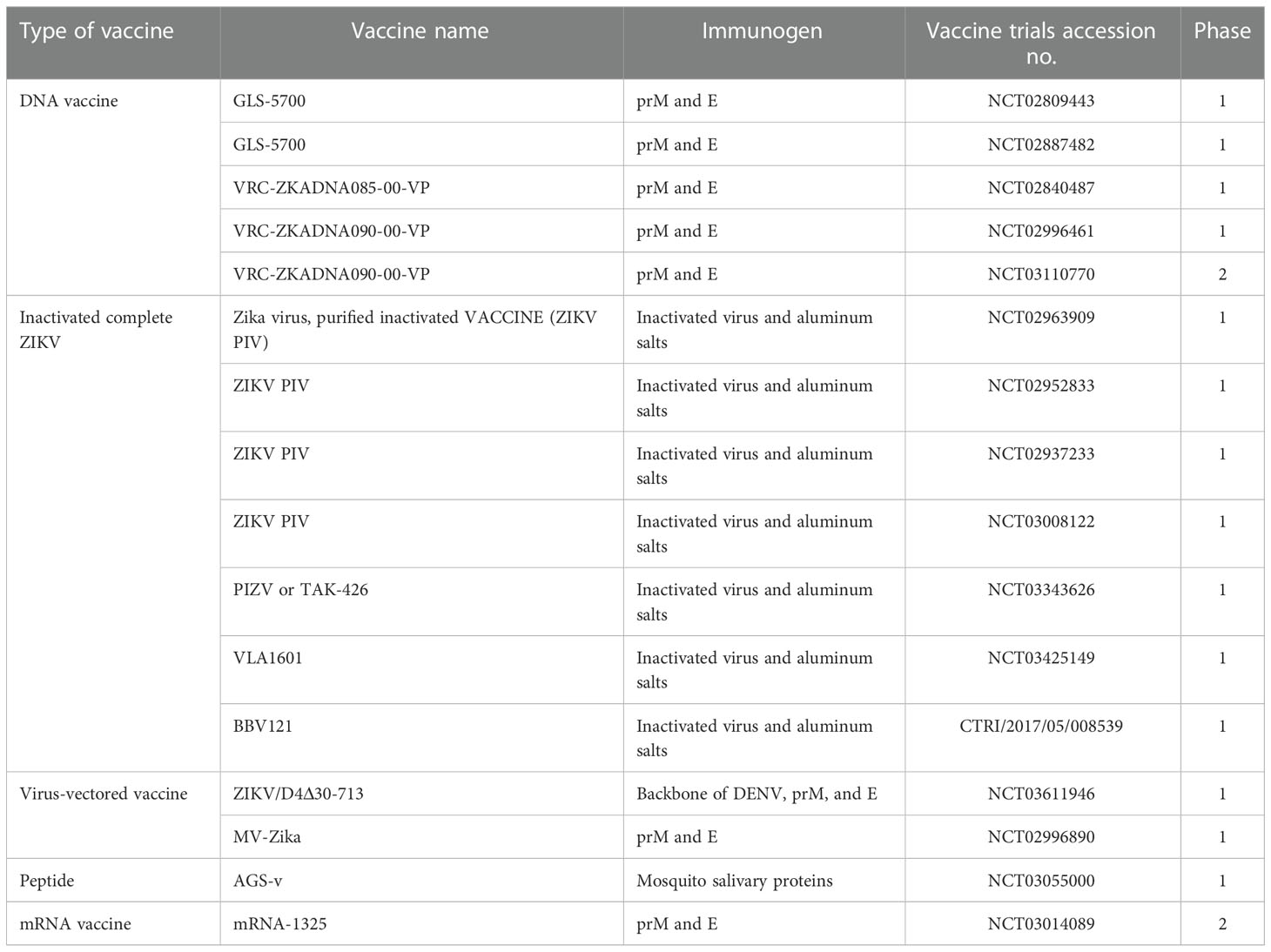

ZIKV infection induces both innate and adaptive immune responses. The innate immune response is the first line of defense against ZIKV. ZIKV infection triggers type I interferons and signaling, which may inhibit ZIKV, but ZIKV exhibits different mechanisms to interfere with IFN induction. Non-structural proteins play an important role in IFN inhibition. The humoral immune response is protective against ZIKV, and specific neutralizing antibodies are produced against the E protein. Vertical transmission is inhibited by recognizing a quaternary epitope on the E protein dimer–dimer, by recognizing the lateral ridge epitope of domain III of the E protein, and by recognizing a quaternary epitope spanning all three domains of the E protein. However, this may lead to the enhancement of dengue virus replication and a phenomenon known as ADE (i.e., antibody-dependent enhancement) (72). Therefore, the vaccine must be designed by taking into consideration the phenomenon of ADE. In addition, understanding the correlation between immunity and infection is difficult, as different levels of adaptive immune response also differ from individual to individual, depending on age, sex, and health conditions, and correlation also differs in animal models, making it difficult to understand the effect on human beings, especially neonates, as ethical issues will be faced. Despite these shortcomings and limitations, many vaccine candidates have been developed to fight against ZIKV. Developing a safe and effective vaccine against ZIKV will help in preventing the spread of ZIKV, and save people from its adverse effects. Various kinds of vaccines against ZIKV infection, for example, DNA vaccines, mRNA vaccines, live-attenuated vaccines, virus-like protein vaccines, subunit vaccines, virus-vectored vaccines, and purified inactivated vaccines, have been tested in preclinical studies in non-human primates and in clinical trials in humans (Tables 3, 4).

Table 4 ZIKV vaccines that are currently undergoing clinical trials (103).

As there is no treatment, prevention is the best method of protecting against ZIKV, either by protection from mosquito bites or by controlling the vector population (105). In ZIKV-prone areas, populations should be controlled by using mosquito repellents, such as DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide), bed nets, window screens, and applying permethrin cream on skin and clothes (106). At the moment, the best method for preventing and controlling arboviral infections such as Zika is comprehensive vector management. Vector management includes environment management practices such as destroying breeding sites (e.g., stagnant water, dumping grounds, landfill sites) by spraying larvicides and insecticides (105). Prevention of the sexual transmission of ZIKV requires the use of reliable contraceptives or abstinence at the time of ZIKV infection (107). All of these are temporary methods, as mosquitoes are becoming insecticide resistant. A safe and effective vaccination or antiviral medication is, thus, required to treat ZIKV infection permanently.

The re-emergence of ZIKV has frightened the world. Although there are now fewer cases, there remains the risk of outbreaks in the future. There is uncertainty about the occurrence of ZIKV. Scientists, governments, public health officials, and pharmaceutical companies should come together and prepare to fight strongly the next ZIKV outbreak. There is a need for a safe and effective vaccine to fight against ZIKV, as there are some unknown mechanisms that help the virus to escape. It is possible that the ability of the virus to vertically transmit in mosquitoes, and its increasing vector competency, helps it to cope with harsh conditions and re-emerge as an outbreak. More studies should be carried out in this context. Understanding the interaction between the host and ZIKV will also help in developing different therapeutics against ZIKV infection. There is a need for more effort to prevent and treat ZIKV. Vaccine development and the use of vaccines against any pandemic depends on factors such as animal models for preclinical studies, validation of vaccines by assuring their safety (including safety for pregnant women and neonates), production at massive levels, and clinical trials. More studies should be conducted to determine the effects of vaccines on pregnant women, fetal development, infants, and elderly individuals. As some vaccines are under clinical trial, they should be tested further for any side effects. Work/tests must also be carried out to bring a ZIKV vaccine to licensure and public use. As cases of ZIKV have significantly reduced, a controlled human infection model should be developed to test the efficacy and correlation in humans; however, due to a lack of support, it has become difficult to develop such models. This will adversely affect ZIKV vaccine development projects and can threaten the public in the event of a sudden outbreak, as was seen in the case of COVID-19. Therefore, there is a need for a scientific society that can predict outbreaks and prepare to fight against such outbreaks.

ND: manuscript drafting, writing, and reviewing. MY: information collection, reviewing the manuscript, and editing. HS and RJ helped in reviewing and editing. NS: manuscript conceptualization, reviewing, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors are grateful to Maharshi Dayanand University for providing University Research Scholarship to ND and MY.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. World Health Organization. “Zika epidemiology update.” World health organization. (2019) https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/zika-epidemiology-update.

2. Grant A, Ponia SS, Tripathi S, Balasubramaniam V, Miorin L, Sourisseau M, et al. Zika virus targets human STAT2 to inhibit type I interferon signaling. Cell Host Microbe (2016) 19:882–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.009

3. World Health Organization. Zika situation report: Zika virus, microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome.”(2016). Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250633.

4. Pergolizzi J, LeQuang JA, Umeda-Raffa S, Fleischer C, Pergolizzi IIIJ, Pergolizzi C, et al. The zika virus: Lurking behind the COVID-19 pandemic? J Clin Pharm Ther (2021) 46:267–76. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13310

5. Khan E, Jindal H, Mishra P, Suvvari TK, Jonna S. The 2021 zika outbreak in uttar pradesh state of India: Tackling the emerging public health threat. Trop Doctor. (2022) 52:474–8. doi: 10.1177/00494755221113285

6. Sáfadi MA, Almeida FJ, de Ávila Kfouri R. Zika virus outbreak in Brazil–lessons learned and perspectives for a safe and effective vaccine. Anatomical Rec (2021) 304:1194–201. doi: 10.1002/ar.24622

7. Dahiya N, Yadav M, Yadav A, Sehrawat N. Zika virus vertical transmission in mosquitoes: A less understood mechanism. J Vector Borne Diseases. (2022) 59:37–44. doi: 10.4103/0972-9062.331411

8. Rather IA, Lone JB, Bajpai VK, Paek WK, Lim J. Zika virus: An emerging worldwide threat. Front Microbiol (2017) 8:1417. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01417

9. Song BH, Yun SI, Woolley M, Lee YM. Zika virus: History, epidemiology, transmission, and clinical presentation. J neuroimmunology. (2017) 308:50–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.03.001

10. Gutiérrez-Bugallo G, Piedra LA, Rodriguez M, Bisset JA, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Weaver SC, et al. Vector-borne transmission and evolution of zika virus. Nat Ecol evolution. (2019) 3:561–9. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0836-z

11. Tham HW, Balasubramaniam V, Ooi MK, Chew MF. Viral determinants and vector competence of zika virus transmission. Front Microbiol (2018) 9:1040. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01040

12. Musso D, Nilles EJ, Cao-Lormeau VM. Rapid spread of emerging zika virus in the pacific area. Clin Microbiol Infection. (2014) 20(10):O595–6. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12707

13. Miller BR, Monath TP, Tabachnick WJ, Ezike VI. Epidemic yellow fever caused by an incompetent mosquito vector. Trop Med Parasitol (1989) 40(4):396–9.

14. Del Carpio-Orantes L, del Carmen González-Clemente M, Lamothe-Aguilar T. Zika and its vector mosquitoes in Mexico. J Asia-Pacific Biodiversity. (2018) 11(2):317–9. doi: 10.1016/j.japb.2018.01.002

15. Obadia T, Gutierrez-Bugallo G, Duong V, Nunez A, Fernandes R, Kamgang B, et al. Zika vector competence data reveals risks of outbreaks: the contribution of the European ZIKAlliance project. Nat Commun (2022) 13(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32234-y

16. Musso D, Ko AI, Baud D. Zika virus infection–after the pandemic. New Engl J Med (2019) 381(15):1444–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1808246

17. de Oliveira WK, Cortez-Escalante J, De Oliveira WT, Carmo GM, Henriques CM, Coelho GE, et al. Increase in reported prevalence of microcephaly in infants born to women living in areas with confirmed zika virus transmission during the first trimester of pregnancy–Brazil, 2015. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep (2016) 65(9):242–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6509e2

18. Baud D, Gubler DJ, Schaub B, Lanteri MC, Musso D. An update on zika virus infection. Lancet (2017) 390(10107):2099–109. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31450-2

19. Freitas DA, Souza-Santos R, Carvalho LM, Barros WB, Neves LM, Brasil P, et al. Congenital zika syndrome: A systematic review. PloS One (2020) 15(12):e0242367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242367

20. Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastère S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak associated with zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet (2016) 387(10027):1531–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6

21. Shahrizaila N, Lehmann HC, Kuwabara S. Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Lancet (2021) 397(10280):1214–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00517-1

22. Del Carpio Orantes L. Guillain-Barré Syndrome associated with zika virus infection in the americas: A bibliometric study. Neurologia (Barcelona Spain). (2018) 35(6):426–9.

23. Del Carpio Orantes L, Méndez CI, García RJ, García AN, Cabrera YL, Salguero LS, et al. Síndrome de Guillain Barré asociado a los brotes de zika, de brasil a méxico. Neurología Argentina. (2020) 12(3):147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuarg.2020.06.002

24. Tang H, Hammack C, Ogden SC, Wen Z, Qian X, Li Y, et al. Zika virus infects human cortical neural progenitors and attenuates their growth. Cell Stem Cell (2016) 18(5):587–90. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.016

25. Bhagat R, Prajapati B, Narwal S, Agnihotri N, Adlakha YK, Sen J, et al. Zika virus e protein alters the properties of human fetal neural stem cells by modulating microRNA circuitry. Cell Death Differentiation. (2018) 25(10):1837–54. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0163-y

26. Garcez PP, Loiola EC, Madeiro da Costa R, Higa LM, Trindade P, Delvecchio R, et al. Zika virus impairs growth in human neurospheres and brain organoids. Science (2016) 352(6287):816–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6116

27. Nowakowski TJ, Pollen AA, Di Lullo E, Sandoval-Espinosa C, Bershteyn M, Kriegstein AR. Expression analysis highlights AXL as a candidate zika virus entry receptor in neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell (2016) 18(5):591–6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.012

28. Smit JM, Moesker B, Rodenhuis-Zybert I, Wilschut J. Flavivirus cell entry and membrane fusion. Viruses (2011) 3(2):160–71. doi: 10.3390/v3020160

29. Hamel R, Dejarnac O, Wichit S, Ekchariyawat P, Neyret A, Luplertlop N, et al. Biology of zika virus infection in human skin cells. J virology. (2015) 89(17):8880–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00354-15

30. Komarasamy TV, Adnan NA, James W, Balasubramaniam VR. Zika virus neuropathogenesis: The different brain cells, host factors and mechanisms involved. Front Immunol (2022) 13:773191–. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.773191

31. Meertens L, Labeau A, Dejarnac O, Cipriani S, Sinigaglia L, Bonnet-Madin L, et al. Axl mediates ZIKA virus entry in human glial cells and modulates innate immune responses. Cell Rep (2017) 18(2):324–33. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.045

32. Wang ZY, Wang Z, Zhen ZD, Feng KH, Guo J, Gao N, et al. Axl is not an indispensable factor for zika virus infection in mice. J Gen virology. (2017) 98(8):2061. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000886

33. Olagnier D, Muscolini M, Coyne CB, Diamond MS, Hiscott J. Mechanisms of zika virus infection and neuropathogenesis. DNA Cell Biol (2016) 35(8):367–72. doi: 10.1089/dna.2016.3404

34. Dang J, Tiwari SK, Lichinchi G, Qin Y, Patil VS, Eroshkin AM, et al. Zika virus depletes neural progenitors in human cerebral organoids through activation of the innate immune receptor TLR3. Cell Stem Cell (2016) 19(2):258–65. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.014

35. Liang Q, Luo Z, Zeng J, Chen W, Foo SS, Lee SA, et al. Zika virus NS4A and NS4B proteins deregulate akt-mTOR signaling in human fetal neural stem cells to inhibit neurogenesis and induce autophagy. Cell Stem Cell (2016) 19(5):663–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.019

36. Zhang ZW, Li ZL, Yuan S. The role of secretory autophagy in zika virus transfer through the placental barrier. Front Cell infection Microbiol (2017) 6:206. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00206

37. Blázquez AB, Escribano-Romero E, Merino-Ramos T, Saiz JC, Martín-Acebes MA. Stress responses in flavivirus-infected cells: activation of unfolded protein response and autophagy. Front Microbiol (2014) 5:266. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00266

38. Ojha CR, Rodriguez M, Lapierre J, Muthu Karuppan MK, Branscome H, Kashanchi F, et al. Complementary mechanisms potentially involved in the pathology of zika virus. Front Immunol (2018) 9:2340. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02340

39. Theel ES, Hata DJ. Diagnostic testing for zika virus: a postoutbreak update. J Clin Microbiol (2018) 56(4):e01972-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01972-17

40. Bhardwaj U, Pandey N, Rastogi M, Singh SK. Gist of zika virus pathogenesis. Virology (2021) 560:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2021.04.008

41. World Health Organization. Laboratory testing for zika virus and dengue virus infections: interim guidance(2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-ZIKV_DENV-LAB-2022.1.

42. Silva SJ, MH P, DR G, Krokovsky L, FL M, MA S, et al. Development and validation of reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) for rapid detection of ZIKV in mosquito samples from Brazil. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40960-5

43. Mauk MG, Song J, Bau HH, Liu C. Point-of-care molecular test for zika infection. Clin Lab Int (2017) 41:25.

44. World Health Organization. Pregnancy management in the context of zika virus: interim guidance (No. WHO/ZIKV/MOC/16.2 rev. 1). World Health Organization (2016). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-ZIKV-MOC-16.2-Rev.1.

45. Chan JF, Choi GK, Yip CC, Cheng VC, Yuen KY. Zika fever and congenital zika syndrome: an unexpected emerging arboviral disease. J Infection. (2016) 72(5):507–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.02.011

46. Poland GA, Kennedy RB, Ovsyannikova IG, Palacios R, Ho PL, Kalil J. Development of vaccines against zika virus. Lancet Infect diseases. (2018) 18(7):e211–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30063-X

47. Leonhard SE, Mandarakas MR, Gondim FA, Bateman K, Ferreira ML, Cornblath DR, et al. Diagnosis and management of Guillain–Barré syndrome in ten steps. Nat Rev Neurology. (2019) 15(11):671–83. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0250-9

48. Rampini D, Prieto DC, Colzi AL, de Araújo RV, Giarolla J. Future and perspectives of the zika virus: Drug repurposing as a powerful tool for treatment insights. Mini Rev Medicinal Chem (2020) 20(18):1917–28. doi: 10.2174/1389557520666200711174007

49. Tan LY, Komarasamy TV, James W, Balasubramaniam VR. Host molecules regulating neural invasion of zika virus and drug repurposing strategy. Front Microbiol (2022) 13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.743147

50. Sacramento CQ, de Melo GR, de Freitas CS, Rocha N, Hoelz LV, Miranda M, et al. The clinically approved antiviral drug sofosbuvir inhibits zika virus replication. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):1–2. doi: 10.1038/srep40920

51. Shiryaev SA, Mesci P, Pinto A, Fernandes I, Sheets N, Shresta S, et al. Repurposing of the anti-malaria drug chloroquine for zika virus treatment and prophylaxis. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15467-6

52. Albulescu IC, Kovacikova K, Tas A, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ. Suramin inhibits zika virus replication by interfering with virus attachment and release of infectious particles. Antiviral Res (2017) 143:230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.04.016

53. Li Z, Brecher M, Deng YQ, Zhang J, Sakamuru S, Liu B, et al. Existing drugs as broad-spectrum and potent inhibitors for zika virus by targeting NS2B-NS3 interaction. Cell Res (2017) 27(8):1046–64. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.88

54. Barbosa-Lima G, Moraes AM, Araújo AD, da Silva ET, de Freitas CS, Vieira YR, et al. 2, 8-bis (trifluoromethyl) quinoline analogs show improved anti-zika virus activity, compared to mefloquine. Eur J medicinal Chem (2017) 127:334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.12.058

55. Pan T, Peng Z, Tan L, Zou F, Zhou N, Liu B, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs potently inhibit the replication of zika viruses by inducing the degradation of AXL. J virology. (2018) 92(20):e01018-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01018-18

56. Españo E, Nam JH, Song EJ, Song D, Lee CK, Kim JK. Lipophilic statins inhibit zika virus production in vero cells. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):1–1.

57. Kim JA, Seong RK, Kumar M, Shin OS. Favipiravir and ribavirin inhibit replication of Asian and African strains of zika virus in different cell models. Viruses (2018) 10(2):72. doi: 10.3390/v10020072

58. Yang S, Xu M, Lee EM, Gorshkov K, Shiryaev SA, He S, et al. Emetine inhibits zika and Ebola virus infections through two molecular mechanisms: inhibiting viral replication and decreasing viral entry. Cell discovery. (2018) 4(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0034-1

59. Rosen BD, inventor, US PHYTOTHERAPY Inc, assignee. Alternative ACT with natural botanical active GRAS ingredients for treatment and prevention of the ZIKA virus. United States patent US (2017) 9:675,582.

60. Batista MN, Braga AC, Campos GR, Souza MM, Matos RP, Lopes TZ, et al. Natural products isolated from oriental medicinal herbs inactivate zika virus. Viruses (2019) 11(1):49. doi: 10.3390/v11010049

61. Lai ZZ, Ho YJ, Lu JW. Cephalotaxine inhibits zika infection by impeding viral replication and stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2020) 522(4):1052–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.12.012

62. Roy A, Lim L, Srivastava S, Lu Y, Song J. Solution conformations of zika NS2B-NS3pro and its inhibition by natural products from edible plants. PloS One (2017) 12(7):e0180632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180632

63. Rausch K, Hackett BA, Weinbren NL, Reeder SM, Sadovsky Y, Hunter CA, et al. Screening bioactives reveals nanchangmycin as a broad spectrum antiviral active against zika virus. Cell Rep (2017) 18(3):804–15. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.068

64. Xu M, Lee EM, Wen Z, Cheng Y, Huang WK, Qian X, et al. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of zika virus infection and induced neural cell death via a drug repurposing screen. Nat Med (2016) 22(10):1101–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.4184

65. Leonardi W, Zilbermintz L, Cheng LW, Zozaya J, Tran SH, Elliott JH, et al. Bithionol blocks pathogenicity of bacterial toxins, ricin and zika virus. Sci Rep (2016) 6(1):1–2. doi: 10.1038/srep34475

66. Puschnik AS, Marceau CD, Ooi YS, Majzoub K, Rinis N, Contessa JN, et al. A small-molecule oligosaccharyltransferase inhibitor with pan-flaviviral activity. Cell Rep (2017) 21(11):3032–9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.054

67. de Carvalho OV, Félix DM, de Mendonça LR, de Araújo CM, de Oliveira Franca RF, Cordeiro MT, et al. The thiopurine nucleoside analogue 6-methylmercaptopurine riboside (6MMPr) effectively blocks zika virus replication. Int J antimicrobial agents. (2017) 50(6):718–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.08.016

68. Ghezzi S, Cooper L, Rubio A, Pagani I, Capobianchi MR, Ippolito G, et al. Heparin prevents zika virus induced-cytopathic effects in human neural progenitor cells. Antiviral Res (2017) 140:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.12.023

69. Costa VV, Del Sarto JL, Rocha RF, Silva FR, Doria JG, Olmo IG, et al. N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockade prevents neuronal death induced by zika virus infection. MBio (2017) 8(2):e00350-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00350-17

70. Retallack H, Di Lullo E, Arias C, Knopp KA, Laurie MT, Sandoval-Espinosa C, et al. Zika virus cell tropism in the developing human brain and inhibition by azithromycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2016) 113(50):14408–13.

71. Lei J, Vermillion MS, Jia B, Xie H, Xie L, McLane MW, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist therapy mitigates placental dysfunction and perinatal injury following zika virus infection. JCI Insight (2019) 4(7):1–15. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.122678

72. Pattnaik A, Sahoo BR, Pattnaik AK. Current status of zika virus vaccines: successes and challenges. Vaccines (2020) 8(2):266. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020266

73. Griffin BD, Muthumani K, Warner BM, Majer A, Hagan M, Audet J, et al. DNA Vaccination protects mice against zika virus-induced damage to the testes. Nat Commun (2017) 8(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15743

74. Wang R, Liao X, Fan D, Wang L, Song J, Feng K, et al. Maternal immunization with a DNA vaccine candidate elicits specific passive protection against post-natal zika virus infection in immunocompetent BALB/c mice. Vaccine (2018) 36(24):3522–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.051

75. de La Vega MA, Piret J, Griffin BD, Rhéaume C, Venable MC, Carbonneau J, et al. Zika-induced male infertility in mice is potentially reversible and preventable by deoxyribonucleic acid immunization. J Infect diseases. (2019) 219(3):365–74. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy336

76. Hraber P, Bradfute S, Clarke E, Ye C, Pitard B. Amphiphilic block copolymer delivery of a DNA vaccine against zika virus. Vaccine (2018) 36(46):6911–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.022

77. Grubor-Bauk B, Wijesundara DK, Masavuli M, Abbink P, Peterson RL, Prow NA, et al. NS1 DNA vaccination protects against zika infection through T cell–mediated immunity in immunocompetent mice. Sci advances. (2019) 5(12):eaax2388. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax2388

78. To A, Medina LO, Mfuh KO, Lieberman MM, Wong TA, Namekar M, et al. Recombinant zika virus subunits are immunogenic and efficacious in mice. MSphere (2018) 3(1):e00576-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00576-17

79. Medina LO, To A, Lieberman MM, Wong TA, Namekar M, Nakano E, et al. A recombinant subunit based zika virus vaccine is efficacious in non-human primates. Front Immunol (2018) 9:2464. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02464

80. Yang M, Dent M, Lai H, Sun H, Chen Q. Immunization of zika virus envelope protein domain III induces specific and neutralizing immune responses against zika virus. Vaccine (2017) 35(33):4287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.052

81. Tai W, He L, Wang Y, Sun S, Zhao G, Luo C, et al. Critical neutralizing fragment of zika virus EDIII elicits cross-neutralization and protection against divergent zika viruses. Emerging Microbes infections. (2018) 7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41426-017-0007-8

82. Zhu X, Li C, Afridi SK, Zu S, Xu JW, Quanquin N, et al. E90 subunit vaccine protects mice from zika virus infection and microcephaly. Acta neuropathologica Commun (2018) 6(1):1–2. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0572-7

83. Shan C, Muruato AE, Jagger BW, Richner J, Nunes BT, Medeiros D, et al. A single-dose live-attenuated vaccine prevents zika virus pregnancy transmission and testis damage. Nat Commun (2017) 8(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00737-8

84. Richner JM, Jagger BW, Shan C, Fontes CR, Dowd KA, Cao B, et al. Vaccine mediated protection against zika virus-induced congenital disease. Cell (2017) 170(2):273–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.040

85. Xie X, Kum DB, Xia H, Luo H, Shan C, Zou J, et al. A single-dose live-attenuated zika virus vaccine with controlled infection rounds that protects against vertical transmission. Cell Host Microbe (2018) 24(4):487–99. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.09.008

86. Bullard BL, Corder BN, Gorman MJ, Diamond MS, Weaver EA. Efficacy of a T cell-biased adenovirus vector as a zika virus vaccine. Sci Rep (2018) 8(1):1–0. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35755-z

87. Steffen T, Hassert M, Hoft SG, Stone ET, Zhang J, Geerling E, et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy of a recombinant human adenovirus type 5 vaccine against zika virus. Vaccines (2020) 8(2):170. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020170

88. Guo Q, Chan JF, Poon VK, Wu S, Chan CC, Hou L, et al. Immunization with a novel human type 5 adenovirus-vectored vaccine expressing the premembrane and envelope proteins of zika virus provides consistent and sterilizing protection in multiple immunocompetent and immunocompromised animal models. J Infect diseases. (2018) 218(3):365–77. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy187

89. López-Camacho C, Abbink P, Larocca RA, Dejnirattisai W, Boyd M, Badamchi-Zadeh A, et al. Rational zika vaccine design via the modulation of antigen membrane anchors in chimpanzee adenoviral vectors. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1–1.

90. Abbink P, Larocca RA, de la Barrera RA, Bricault CA, Moseley ET, Boyd M, et al. Protective efficacy of multiple vaccine platforms against zika virus challenge in rhesus monkeys. Science (2016) 353(6304):1129–32. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6157

91. Li A, Yu J, Lu M, Ma Y, Attia Z, Shan C, et al. A zika virus vaccine expressing premembrane-envelope-NS1 polyprotein. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05276-4

92. Shi X, Hu J, Guo J, Wu C, Xiong S, Dong C. A vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine carrying zika virus capsid protein protects mice from viral infection. Virologica Sinica. (2019) 34(1):106–10. doi: 10.1007/s12250-019-00083-7

93. Baldwin WR, Livengood JA, Giebler HA, Stovall JL, Boroughs KL, Sonnberg S, et al. Purified inactivated zika vaccine candidates afford protection against lethal challenge in mice. Sci Rep (2018) 8(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34735-7

94. Lecouturier V, Pavot V, Berry C, Donadieu A, de Montfort A, Boudet F, et al. An optimized purified inactivated zika vaccine provides sustained immunogenicity and protection in cynomolgus macaques. NPJ Vaccines (2020) 5(1):1–0. doi: 10.1038/s41541-020-0167-8

95. Young G, Bohning KJ, Zahralban-Steele M, Hather G, Tadepalli S, Mickey K, et al. Complete protection in macaques conferred by purified inactivated zika vaccine: defining a correlate of protection. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60415-6

96. Abbink P, Larocca RA, Visitsunthorn K, Boyd M, de la Barrera RA, Gromowski GD, et al. Durability and correlates of vaccine protection against zika virus in rhesus monkeys. Sci Trans Med (2017) 9(420):eaao4163. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao4163

97. Espinosa D, Mendy J, Manayani D, Vang L, Wang C, Richard T, et al. Passive transfer of immune sera induced by a zika virus-like particle vaccine protects AG129 mice against lethal zika virus challenge. EBioMedicine (2018) 27:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.12.010

98. Dai S, Zhang T, Zhang Y, Wang H, Deng F. Zika virus baculovirus-expressed virus-like particles induce neutralizing antibodies in mice. Virologica Sinica. (2018) 33(3):213–26. doi: 10.1007/s12250-018-0030-5

99. Yang M, Lai H, Sun H, Chen Q. Virus-like particles that display zika virus envelope protein domain III induce potent neutralizing immune responses in mice. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08247-9

100. Zhong Z, Portela Catani JP, Mc Cafferty S, Couck L, Van Den Broeck W, Gorlé N, et al. Immunogenicity and protection efficacy of a naked self-replicating mRNA-based zika virus vaccine. Vaccines (2019) 7(3):96 1–17. doi: 10.3390/vaccines7030096

101. Richner JM, Himansu S, Dowd KA, Butler SL, Salazar V, Fox JM, et al. Modified mRNA vaccines protect against zika virus infection. Cell (2017) 168(6):1114–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.017

102. Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Pelc RS, Muramatsu H, Andersen H, DeMaso CR, et al. Zika virus protection by a single low-dose nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination. Nature (2017) 543(7644):248–51. doi: 10.1038/nature21428

103. Mwaliko C, Nyaruaba R, Zhao L, Atoni E, Karungu S, Mwau M, et al. Zika virus pathogenesis and current therapeutic advances. Pathog Global Health (2021) 115(1):21–39. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2020.1845005

104. Zhou K, Li C, Shi W, HU X, Nandakumar KS, Jiang S, Zhang N. Current progress in the development of Zika virus vaccines. Vaccines (2021) 1004:1–17.

105. Sharma V, Sharma M, Dhull D, Sharma Y, Kaushik S, Kaushik S. Zika virus: an emerging challenge to public health worldwide. Can J Microbiol (2020) 66(2):87–98. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2019-0331

106. Petersen LR, Jamieson DJ, Powers AM, Honein MA. Zika virus. New Engl J Med (2016) 374(16):1552–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1602113

107. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for the prevention of sexual transmission of zika virus: Executive summary (No. WHO/RHR/19.4). (2019). World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311026.

Keywords: transmission, vaccines, therapeutics, Zika (ZIKV), epidemiology

Citation: Dahiya N, Yadav M, Singh H, Jakhar R and Sehrawat N (2023) ZIKV: Epidemiology, infection mechanism and current therapeutics. Front. Trop. Dis 3:1059283. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2022.1059283

Received: 01 October 2022; Accepted: 07 December 2022;

Published: 23 January 2023.

Edited by:

Bapi Pahar, Integrated Research Facility (NIH), United StatesReviewed by:

Luis Del Carpio-Orantes, Delegación Veracruz Norte, MexicoCopyright © 2023 Dahiya, Yadav, Singh, Jakhar and Sehrawat. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Neelam Sehrawat, bmVlbGFtc2VocmF3YXRAbWR1cm9odGFrLmFjLmlu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.