Introduction

Human intelligence (i.e., the ability to consistently solve problems successfully) has evolved through the need to adapt to changing environments. This is not only true of our past but also of our present. Our brain faculties are becoming more sophisticated by cooperating and interacting with technology, specifically digital communication technology (Asaro, 2008).

When we consider the matter of brain function augmentation, we take it for granted that the issue refers to the human brain as a distinct organ. However, as we live in a complex technological society, it is now becoming clear that the issue is much more complicated. Individual brains cannot simply be considered in isolation, and their function is no longer localized or contained within the cranium, as we now know that information may be transmitted directly from one brain to another (Deadwyler et al., 2013; Pais-Vieira et al., 2013). This issue has been discussed in detail and attempts have been made to study the matter within a wider and more global context (Nicolelis and Laporta, 2011). Recent research in the field of brain to brain interfaces has provided the basis for further research and formation of new hypotheses in this respect (Grau et al., 2014; Rao et al., 2014). This concept of rudimentary “brain nets” may be expanded in a more global fashion, and within this framework, it is possible to envisage a much bigger and abstract “meta-entity” of inclusive and distributed capabilities, called the Global Brain (Mayer-Kress and Barczys, 1995; Heylighen and Bollen, 1996; Johnson et al., 1998; Helbing, 2011; Vidal, in press).

This entity reciprocally feeds information back to its components—the individual human brains. As a result, novel and hitherto unknown consequences may materialize such as, for instance, the emergence of rudimentary global “emotion” (Garcia and Tanase, 2013; Garcia et al., 2013; Kramera et al., 2014), and the appearance of decision-making faculties (Rodriguez et al., 2007). These characteristics may have direct impact upon our biology (Kyriazis, 2014a). This has been long discussed in futuristic and sociology literature (Engelbart, 1988), but now it also becomes more relevant to systems neuroscience partly because of the very promising research in brain-to-brain interfaces. The concept is grounded on scientific principles (Last, 2014a) and mathematical modeling (Heylighen et al., 2012).

Augmenting Brain Function on a Global Scale

It can be argued that the continual enhancement of brain function in humans, i.e., the tendency to an increasing intellectual sophistication, broadly aligns well with the main direction of evolution (Steward, 2014). This tendency to an increasing intellectual sophistication also obeys Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety (Ashby, 1958) which essentially states that, for any system to be stable, the number of states of its control mechanisms must be greater than the number of states in the system being controlled. This means that, within an ever-increasing technological environment, we must continue to increase our brain function (mostly through using, or merging with, technology such as in the example of brain to brain communication mentioned above), in order to improve integration and maintain stability of the wider system. Several other authors (Maynard Smith and Szathmáry, 1997; Woolley et al., 2010; Last, 2014a) have expanded on this point, which seems to underpin our continual search for brain enrichment.

The tendency to enrich our brain is an innate characteristic of humans. We have been trying to augment our mental abilities, either intentionally or unintentionally, for millennia through the use of botanicals and custom-made medicaments, herbs and remedies, and, more recently, synthetic nootropics and improved ways to assimilate information. Many of these methods are not only useful in healthy people but are invaluable in age-related neurodegenerative disorders such as dementia and Parkinson's disease (Kumar and Khanum, 2012). Other neuroscience-based methods such as transcranial laser treatments and physical implants (such as neural dust nanoparticles) are useful in enhancing cognition and modulate other brain functions (Gonzalez-Lima and Barrett, 2014).

However, these approaches are limited to the biological human brain as a distinct agent. As shown by the increased research interest in brain to brain communication (Trimper et al., 2014), I argue that the issue of brain augmentation is now embracing a more global aspect. The reason is the continual developments in technology which are changing our society and culture (Long, 2010). Certain brain faculties that were originally evolved for solving practical physical problems have been co-opted and exapted for solving more abstract metaphors, making humans adopt a better position within a technological niche.

The line between human brain function and digital information technologies is progressively becoming indistinct and less well-defined. This blurring is possible through the development of new technologies which enable more efficient brain-computer interfaces (Pfurtscheller and Neuper, 2002), and recently, brain-to-brain interfaces (Grau et al., 2014).

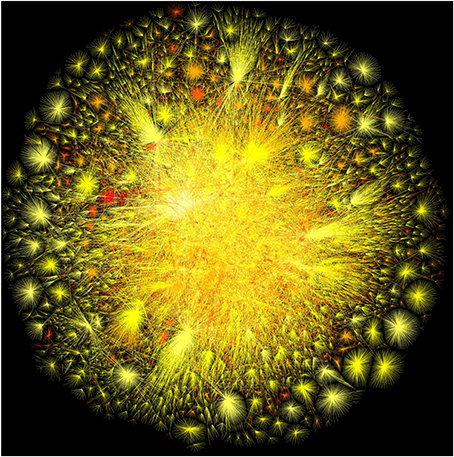

We are now in a position expand on this emergent worldview and examine what trends of systems neuroscience are likely in the near-term future. Technology has been the main drive which brought us to the position we are in today (Henry, 2014). This position is the merging of the physical human brain abilities with virtual domains and automated web services (Kurzweil, 2009). Modern humans cannot purely be defined by their biological brain function. Instead, we are now becoming an amalgam of biological and virtual/digital characteristics, a discrete unit, or autonomous agent, forming part of a wider and more global entity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Computer-generated image of internet connections world-wide (Global Brain). The conceptual similarities with the human brain are remarkable. Both networks exhibit a scale-free, fractal distribution, with some weakly-connected units, and some strongly-connected ones which are arranged in hubs of increasing functional complexity. This helps protect the constituents of the network against stresses. Both networks are “small worlds” which means that information can reach any given unit within the network by passing through only a small number of other units. This assists in the global propagation of information within the network, and gives each and every unit the functional potential to be directly connected to all others. Source: The Opte Project/Barrett Lyon. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International License.

Large Scale Networks and the Global Brain

The Global Brain (Heylighen, 2007; Iandoli et al., 2009; Bernstein et al., 2012) is a self-organizing system which encompasses all those humans who are connected with communication technologies, as well as the emergent properties of these connections. Its intelligence and information-processing characteristics are distributed, in contrast to that of individuals whose intelligence is localized. Its characteristics emerge from the dynamic networks and global interactions between its individual agents. These individual agents are not merely the biological humans but are something more complex. In order to describe this relationship further, I have introduced the notion of the noeme, an emergent agent, which helps formalize the relationships involved (Kyriazis, 2014a). The noeme is a combination of a distinct physical brain function and that of an “outsourced” virtual one. It is the intellectual “networked presence” of an individual within the GB, a meaningful synergy between each individual human, their social interactions and artificial agents, globally connected to other noemes through digital communications technology (and, perhaps soon, through direct brain to brain interfaces). A comparison can be made with neurons which, as individual discrete agents, form part of the human brain. In this comparison, the noemes act as the individual, information-sharing discrete agents which form the GB (Gershenson, 2011). The modeling of noemes helps us define ourselves in a way that strengthens our rational presence in the digital world. By trying to enhance our information-sharing capabilities we become better integrated within the GB and so become a valuable component of it, encouraging mechanisms active in all complex adaptive systems to operate in a way that prolongs our retention within this system (Gershenson and Fernández, 2012), i.e., prolongs our biological lifespan (Kyriazis, 2014b; Last, 2014b).

Discussion

This concept is a helpful way of interpreting the developing cognitive relationship between humans and artificial agents as we evolve and adapt to our changing technological environment. The concept of the noeme provides insights with regards to future problems and opportunities. For instance, the study of the function of the noeme may provide answers useful to biomedicine, by coopting laws applicable to any artificial intelligence medium and using these to enhance human health (Kyriazis, 2014a). Just as certain physical or pharmacological therapies for brain augmentation are useful in neurodegeneration in individuals, so global ways of brain enhancement are useful in a global sense, improving the function and adaptive capabilities of humanity as a whole. One way to augment global brain function is to increase the information content of our environment by constructing smart cities (Caragliu et al., 2009), expanding the notion of the Web of Things (Kamilaris et al., 2011), and by developing new concepts in educational domains (Veletsianos, 2010). This improves the information exchange between us and our surroundings and helps augment brain function, not just physically in individuals, but also virtually in society.

Practical ways for enhancing our noeme (i.e., our digital presence) include:

• Cultivate a robust social media base, in different forums.

• Aim for respect, esteem and value within your virtual environment.

• Increase the number of your connections both in virtual and in real terms.

• Stay consistently visible online.

• Share meaningful information that requires action.

• Avoid the use of meaningless, trivial or outdated platforms.

• Increase the unity of your connections by using only one (user)name for all online and physical platforms.

These methods can help increase information sharing and facilitate our integration within the GB (Kyriazis, 2014a). In a practical sense, these actions are easy to perform and can encompass a wide section of modern communities. Although the benefits of these actions are not well studied, nevertheless some initial findings appear promising (Griffiths, 2002; Granic et al., 2014).

Concluding Remarks

With regards to improving brain function, we are gradually moving away from the realms of science fiction and into the realms of reality (Kurzweil, 2005). It is now possible to suggest ways to enhance our brain function, based on novel concepts dependent not only on neuroscience but also on digital and other technology. The result of such augmentation does not only benefit the individual brain but can also improve all humanity in a more abstract sense. It improves human evolution and adaptation to new technological environments, and this, in turn, may have positive impact upon our health and thus longevity (Solman, 2012; Kyriazis, 2014c).

In a more philosophical sense, our progressive and distributed brain function amplification has begun to lead us toward attaining “god-like” characteristics (Heylighen, in press) particularly “omniscience” (through Google, Wikipedia, the semantic web, Massively Online Open Courses MOOCs—which dramatically enhance our knowledge base), and “omnipresence” (cloud and fog computing, Twitter, YouTube, Internet of Things, Internet of Everything). These are the result of the outsourcing of our brain capabilities to the cloud in a distributed and universal manner, which is an ideal global neural augmentation. The first steps have already been taken through brain to brain communication research. The concept of systems neuroscience is thus expanded to encompass not only the human nervous network but also a global network with societal and cultural elements.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

I thank the help and input of the reviewers, particularly the first one who has dedicated a lot of time into improving the paper.

References

Asaro, P. (2008). “From mechanisms of adaptation to intelligence amplifiers: the philosophy of W. Ross Ashby,” in The Mechanical Mind in History, eds M. Wheeler, P. Husbands, and O. Holland (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 149–184.

Ashby, W. R. (1958). Requisite Variety and its implications for the control of complex systems. Cybernetica (Namur) 1, 2.

Bernstein, A., Klein, M., and Malone, T. W. (2012). Programming the Global Brain. Commun. ACM 55, 1. doi: 10.1145/2160718.2160731

Caragliu, A., Del Bo, C., and Nijkamp, P. (2009). Smart Cities in Europe. Serie Research Memoranda 0048, VU University Amsterdam, Faculty of Economics, Business Administration and Econometrics.

Deadwyler, S. A., Berger, T. W., Sweatt, A. J., Song, D., Chan, R. H., Opris, I., et al. (2013). Donor/recipient enhancement of memory in rat hippocampus. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 7:120. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00120

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Engelbart, D. C. (1988). A Conceptual Framework for the Augmentation of Man's Intellect. Computer-Supported Cooperative Work. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc. ISBN: 0-93461-57-5

Garcia, D., Mavrodiev, P., and Schweitzer, F. (2013). Social Resilience in Online Communities: The Autopsy of Friendster. Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1302.6109 (Accessed October 8, 2014).

Garcia, D., and Tanase, D. (2013). Measuring Cultural Dynamics Through the Eurovision Song Contest. Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1301.2995 (Accessed October 8, 2014).

Gershenson, C. (2011). The sigma profile: a formal tool to study organization and its evolution at multiple scales. Complexity 16, 37–44. doi: 10.1002/cplx.20350

Gershenson, C., and Fernández, N. (2012). Complexity and information: measuring emergence, self-organization, and homeostasis at multiple scales. Complexity 18, 29–44. doi: 10.1002/cplx.21424

Gonzalez-Lima, F., and Barrett, D. W. (2014). Augmentation of cognitive brain function with transcranial lasers. Front. Syst. Neurosc. 8:36. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00036

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Granic, I., Lobel, A., and Engels, R. C. M. E. (2014). The Benefits of Playing Video Games. American Psychologist. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/amp-a0034857.pdf (Accessed October 5, 2014).

Grau, C., Ginhoux, R., Riera, A., Nguyen, T. L., Chauvat, H., Berg, M., et al. (2014). Conscious brain-to-brain communication in humans using non-invasive technologies. PLoS ONE 9:e105225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105225

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Helbing, D. (2011). FuturICT-New Science and Technology to Manage Our Complex, Strongly Connected World. Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1108.6131 (Accessed November 6, 2014).

Henry, C. (2014). IT and the Legacy of Our Cultural Heritage EDUCAUSE Review, Vol. 49 (Louisville, CO: D. Teddy Diggs).

Heylighen, F., and Bollen, J. (1996). “The World-Wide Web as a Super-Brain: from metaphor to model,” in Cybernetics and Systems' 96, ed R. Trappl (Vienna: Austrian Society For Cybernetics), 917–922.

Heylighen, F. (2007). The Global Superorganism: an evolutionary-cybernetic model of the emerging network society. Soc. Evol. Hist. 6, 58–119

Heylighen, F., Busseniers, E., Veitas, V., Vidal, C., and Weinbaum, D. R. (2012). Foundations for a Mathematical Model of the Global Brain: architecture, components, and specifications (No. 2012-05). GBI Working Papers. Available online at: http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/Papers/TowardsGB-model.pdf (Accessed November 6, 2014).

Heylighen, F. (in press). “Return to Eden? promises and perils on the road to a global superintelligence,” in The End of the Beginning: Life, Society and Economy on the Brink of the Singularity, eds B. Goertzel and T. Goertzel.

Johnson, N. L., Rasmussen, S., Joslyn, C., Rocha, L., Smith, S., and Kantor, M. (1998). “Symbiotic Intelligence: self-organizing knowledge on distributed networks driven by human interaction,” in Artificial Life VI, Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Artificial Life (Los Angeles, CA), 403–407.

Iandoli, L., Klein, M., and Zollo, G. (2009). Enabling on-line deliberation and collective decision-making through large-scale argumentation: a new approach to the design of an Internet-based mass collaboration platform. Int. J. Decis. Supp. Syst. Technol. 1, 69–92 doi: 10.4018/jdsst.2009010105

Kamilaris, A., Pitsillides, A., and Trifa, A. (2011). The Smart Home meets the Web of Things. Int. J. Ad Hoc Ubiquit. Comput. 7, 145–154. doi: 10.1504/IJAHUC.2011.040115

Kramera, A. D., Guillory, J. E., and Hancock, J. T. (2014). Experimental Evidence of Massive-Scale Emotional Contagion Through Social Networks. Available online at: http://www.pnas.org/content/111/24/8788.full (Accessed October 10, 2014).

Kumar, G. P., and Khanum, F. (2012). Neuroprotective potential of phytochemicals. Pharmacogn Rev. 6, 81–90. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.99898

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kurzweil, R. (2005). The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York, NY: Penguin books-Viking Publisher. ISBN: 978-0-670-03384-3.

Kurzweil, R. (2009). “The coming merging of mind and machine,” in Scientific American. Available online at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/merging-of-mind-and-machine/ (Accessed November 5, 2014).

Kyriazis, M. (2014a). Technological integration and hyper-connectivity: tools for promoting extreme human lifespans. Complexity. doi: 10.1002/cplx.21626

Kyriazis, M. (2014b). Reversal of informational entropy and the acquisition of germ-like immortality by somatic cells. Curr. Aging Sci. 7, 9–16. doi: 10.2174/1874609807666140521101102

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kyriazis, M. (2014c). Information-Sharing, Adaptive Epigenetics and Human Longevity. Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1407.6030 (Accessed October 8, 2014).

Last, C. (2014a). Global Brain and the future of human society. World Fut. Rev. 6, 143–150. doi: 10.1177/1946756714533207

Last, C. (2014b). Human evolution, life history theory and the end of biological reproduction. Curr. Aging Sci. 7, 17–24. doi: 10.2174/1874609807666140521101610

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Long, S. M. (2010). Exploring Web 2.0: The Impact of Digital Communications Technologies on Youth Relationships and Sociability. Available online at: http://scholar.oxy.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=sociology_student (Accessed November 5, 2014).

Mayer-Kress, G., and Barczys, C. (1995). The global brain as an emergent structure from the Worldwide Computing Network, and its implications for modeling. Inform. Soc. 11, 1–27 doi: 10.1080/01972243.1995.9960177

Maynard Smith, J., and Szathmáry, E. (1997). The Major Transitions in Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nicolelis, M., and Laporta, A. (2011). Beyond Boundaries: The New Neuroscience of Connecting Brains with Machines—and How It Will Change Our Lives. Times Books, Henry Hold, New York. ISBN: 0-80509052-5.

Pais-Vieira, M., Lebedev, M., Kunicki, C., Wang, J., and Nicolelis, M. (2013). A brain-to-brain interface for real-time sharing of sensorimotor information. Sci. Rep. 3:1319. doi: 10.1038/srep01319

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pfurtscheller, G., and Neuper, C. (2002). Motor imagery and direct brain-computer communication. Proc. IEEE 89, 1123–1134. doi: 10.1109/5.939829

Rao, R. P. N., Stocco, A., Bryan, M., Sarma, D., and Youngquist, T. M. (2014). A direct brain-to-brain interface in humans. PLoS ONE 9:e111332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111332

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rodriguez, M. A., Steinbock, D. J., Watkins, J. H., Gershenson, C., Bollen, J., Grey, V., et al. (2007). Smartocracy: Social Networks for Collective Decision Making (p. 90b). Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society.

Solman, P. (2012). As Humans and Computers Merge… Immortality? Interview with Ray Kurzweil. PBS. 2012-07-03. Available online at: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/business-july-dec12-immortal_07-10/ (Retrieved November 5, 2014).

Steward, J. E. (2014). The direction of evolution: the rise of cooperative organization. Biosystems 123, 27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2014.05.006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Trimper, J. B., Wolpe, P. R., and Rommelfanger, K. S. (2014). When “I” becomes “We”: ethical implications of emerging brain-to-brain interfacing technologies. Front. Neuroeng. 7:4 doi: 10.3389/fneng.2014.00004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Veletsianos, G. (Ed.). (2010). Emerging Technologies in Distance Education. Edmonton, AB: AU Publisher.

Vidal, C. (in press). “Distributing cognition: from local brains to the global brain,” in The End of the Beginning: Life, Society and Economy on the Brink of the Singularity, eds B. Goertzel and T. Goertzel.

Woolley, A. W., Chabris, C. F., Pentland, A., Hashmi, N., and Malone, T. W. (2010). Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science 330, 686–688. doi: 10.1126/science.1193147

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: global brain, complex adaptive systems, human longevity, techno-cultural society, noeme, systems neuroscience

Citation: Kyriazis M (2015) Systems neuroscience in focus: from the human brain to the global brain? Front. Syst. Neurosci. 9:7. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00007

Received: 14 October 2014; Accepted: 14 January 2015;

Published online: 06 February 2015.

Edited by:

Manuel Fernando Casanova, University of Louisville, USACopyright © 2015 Kyriazis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence:ZHJtYXJpb3NAbGl2ZS5pdA==

Marios Kyriazis

Marios Kyriazis