- 1Department of Agricultural and Rural Management, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Tamil Nadu, India

- 2National Institute of Agricultural Extension Management (MANAGE), Telangana, India

Introduction: Agritourism is an emerging sector with the potential to drive rural development, economic diversification, and cultural heritage preservation. In Tamil Nadu, agritourism remains underexplored from a supply-side perspective. This study investigates the motivations, operational challenges, and expectations of farmers engaged in agritourism to understand its sustainable development potential.

Methods: A mixed-methods approach, guided by grounded theory, was adopted to examine supply-side dynamics. Data were collected from 20 agritourism farm owners in the Coimbatore district of Tamil Nadu through structured questionnaires using a five-point Likert scale. Qualitative insights were also gathered through in-depth interviews to supplement quantitative findings.

Results: Findings reveal that farmers are primarily motivated by economic sustainability, additional income generation, rural heritage preservation, and farm diversification. However, key barriers include inadequate agritourism licensing, insufficient public awareness, and limited marketing efforts. Farmers also face challenges in accessing institutional support and navigating regulatory frameworks.

Discussion: To promote sustainable agritourism, the study recommends the establishment of a dedicated agritourism development committee, the formulation of specific government guidelines, and the integration of agritourism awareness into school curricula. These measures can enhance visibility, create employment opportunities, and ensure the long-term sustainability of agritourism in Tamil Nadu. This research provides valuable insights for policymakers and stakeholders, aiming to strengthen agritourism as a viable rural enterprise.

1 Introduction

Tourism as an industry typically occurs in locations with a variety of natural or artificial attractions that draw in visitors from outside the area for various activities. Traditionally, a tourism destination has been defined as a specific geographical region, with the expectation that it meets certain criteria to qualify as such. These criteria include the presence of tourist attractions, accommodations, and transportation systems for travel to, from, and within the destination (Del Chiappa and Baggio, 2015). Over time, tourism has diversified into various types, with agritourism emerging as one of them.

Agritourism is a blended concept that encompasses recreational activities centered around farming, agricultural education, and a wide array of outdoor experiences (Barbieri, 2014). From an agricultural standpoint, it is closely tied to alternative farming practices, value-added production, direct sales of farm products, and the development of rural communities. From a tourism standpoint, agritourism is associated with agricultural destinations, sections of larger non-agricultural tourist areas, or exclusively agritourism-focused locations.

Agritourism has gained traction in several countries, including the United States (Khanal and Mishra, 2014; Sotomayor et al., 2014), Italy (Ohe and Ciani, 2011), the United Kingdom (Bernardo et al., 2004), and Israel (Tchetchik et al., 2008). The global agritourism market was valued at $42.46 billion in 2019 and is projected to grow to $62.98 billion by 2027, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.4% from 2020 to 2027 (Anil, 2021).

In many regions, agritourism has been viewed as a low-risk, low-investment strategy, as farmers leverage their existing resources (Tew and Barbieri, 2012). It can rejuvenate rural economies through the multiplier effect, where various local businesses benefit from the influx of tourists (Contini et al., 2009). Farmers in developed countries have increasingly turned to tourism as a promising industry to offset declining agricultural revenues (Deville et al., 2016).

Agritourism has been extensively promoted as a potential source of income and job creation in countries like Italy and the United States, particularly in rural areas where agricultural economies have declined (Kline et al., 2016). When developed effectively, agritourism can enhance the long-term profitability of farm products and services, especially benefiting small farms in distress, while also fostering entrepreneurship (Naidoo and Sharpley, 2016).

In this scenario, agritourism has been extensively researched in developed nations like the United States, Italy, and Australia, with a predominant focus on demand-side aspects, including tourists' motivations, behaviors, and satisfaction (Nickerson et al., 2001; Barbieri, 2010). However, supply-side dynamics—particularly the motivations, challenges, and expectations of farm owners—have received limited attention, especially in developing countries such as India. In India, agritourism is experiencing revenue growth at an annual rate of 20% (Deya, 2019). Particularly, the Tamil Nadu state in India, with its rich agricultural and cultural heritage, holds significant potential for agritourism. Despite this, existing studies have not adequately explored the motivations and operational challenges faced by agritourism farm owners in the region. While some states like Kerala and Maharashtra have seen some research on their agritourism initiatives, Tamil Nadu remains underexplored in this regard, leaving a gap in research that could guide policy and practice.

Global studies have identified key motivations for agritourism, such as income diversification and cultural preservation (Cassia et al., 2015; Ollenburg and Buckley, 2007). However, there is limited evidence on how these motivations intersect with operational barriers in developing countries, where structural and regulatory challenges are more pronounced (Tew and Barbieri, 2012). Research on operational challenges, including licensing difficulties, marketing limitations, and the absence of tourism associations, is sparse. Understanding these factors is crucial for assessing the feasibility and sustainability of agritourism ventures in underdeveloped regions.

To bridge these gaps, this study applies grounded theory (GT) to explore the motivations and challenges faced by agritourism farm owners in Tamil Nadu. Grounded theory allows for the development of context-specific insights by iteratively collecting and analyzing data, enabling the identification of patterns, themes, and relationships reflective of real-world experiences (Charmaz, 2015). This approach is particularly useful for understanding the mentalities of agritourism farm owners, including motivations like income diversification, cultural preservation, and optimizing the use of farm resources, as well as operational challenges such as regulatory barriers, marketing constraints, and limited public awareness.

By centering the research on agritourism farm owners, this study provides actionable insights for policymakers, focusing on addressing barriers to growth, fostering sustainable development, and promoting economic diversification and rural revitalization. Grounded in the lived realities of agritourism farm owners, these findings contribute to the practical advancement of agritourism through tailored policy recommendations and capacity-building strategies. Ultimately, this research aims to support the long-term sustainability and success of agritourism in Tamil Nadu, ensuring relevance and applicability to the region's unique socio-economic and cultural landscape.

2 Literature review

2.1 Agritourism overview

In recent decades, farmers have increasingly recognized the broader contributions of agriculture beyond traditional food production. Faced with stagnant net income from conventional crops and livestock (Kirschenmann, 2003), many farmers have turned to diversify their economic activities. Given agriculture's multiple roles and its significant impact on the rural landscape, the economy, community development, and ecosystems, there are various diversification options available (Butler and Flora, 2024). Among these, tourism has become a prominent choice, offering economic and social benefits that create new opportunities for rural development, while also positively influencing the environment, landscape, and slowing depopulation (Lupi et al., 2017). For instance, a study conducted on farms in less favored regions of Sardinia, Italy, examined how agritourism impacts the economic performance of multifunctional farms. The findings revealed that agritourism provides effective strategies for supporting small and medium-sized farms, especially those located near popular agritourism destinations (Arru et al., 2021).

In recent years, the number of agritourism farms has surged both locally and globally, drawing greater attention to its conservation potential (Liu et al., 2017). While the primary reason for the rise of agritourism lies on the supply side, this growth would not have been possible without strong market demand (McGehee and Kim, 2004). The increase in discretionary income and the desire for more unique vacation experiences have fuelled the growth of tourism in rural farming areas (Tchetchik et al., 2008). In the United States, the USDA Economic Research Service highlighted agritourism as a key diversification strategy for farms, offering significant benefits to rural communities. Additionally, a study evaluating the readiness of agricultural farms for agritourism development emphasized the need to align farming activities with tourist expectations to enhance both visitor experiences and economic outcomes (Baipai et al., 2024). Such alignment is essential for integrating tourism into traditional farming successfully. Agritourism appeals to urban tourists seeking traditional hospitality, natural and cultural experiences, tranquility, themed holidays, authenticity, and health-related activities (Chang, 2003). These motivations, combined with improved access to rural destinations, have contributed to agritourism's rising popularity among farmers, rural communities, and the tourism industry.

Agritourism encompasses organized recreational and educational activities on active farms or other agricultural operations (Ollenburg and Buckley, 2007). In recent years, the growing demand from tourists for local food and farm experiences has driven a significant global increase in agritourism (Matyakubov et al., 2022). Researchers across various perspectives agree that agritourism offers a promising solution to meet the needs of both tourists and rural populations, while also creating real opportunities for rural community development (Ammirato et al., 2020). This growing interest in agritourism has also captured the attention of academics.

To successfully develop agritourism, it is crucial to examine the attitudes and expectations of two key stakeholder groups: tourists and agritourism farm owners. The active participation of farm owners is one of the most critical factors for successful agritourism development. A review of quantitative research in agritourism found that although the use of quantitative methods has grown in recent years, there remains a significant gap in studies focusing on developing countries. The review emphasized the critical role of agritourism in supporting rural development and poverty alleviation in these regions (Bhatta and Ohe, 2020). Furthermore, the influence of policy and regulatory frameworks on agritourism development has been explored. A study on India highlighted the importance of supportive policies, noting that well-defined guidelines and incentives could encourage farmers to diversify into tourism-related ventures (Dsouza et al., 2024). As Peira et al. (2021) note, rural areas can become tourist destinations when local actors, particularly farmers, engage in tourism development efforts. Therefore, understanding farmers' attitudes toward agritourism, as well as their resources and capacity to participate in its development, is essential.

2.2 Supply side motivations

Phelan and Sharpley (2011) observed a growing body of research on agritourism, particularly regarding the motivations for integrating it into farm operations. Previous studies have explored various factors driving farmers to adopt agritourism (Barbieri, 2010; Nickerson et al., 2001; Ollenburg and Buckley, 2007). One of the main motivations for farmers to adopt agritourism is the opportunity for income diversification. By engaging in tourism activities, farmers can generate additional income, offering financial stability against market volatility and unpredictable weather conditions. For example, a study on the agritourism sector in Missouri highlighted the need to understand visitor motivations and satisfaction to improve service quality, thereby boosting farm profitability (Baby and Kim, 2024). Similarly, research by Chang et al. (2019) found that agritourism participation not only increases farm income but also supports family farm succession. Nickerson et al. (2001) examined the motivations of farmers and ranchers in Montana, USA, for diversifying into agritourism. The top five reasons identified were generating additional income, maximizing resource use, coping with fluctuations in agricultural income, providing employment for family members, and pursuing a personal interest or hobby. In England, Sharpley and Vass (2006) conducted an attitudinal study, which revealed that farmers held positive views on the importance of diversification for long-term financial security, the potential for generating extra income, and the necessity of diversification. Ollenburg and Buckley (2007) studied Australian farmers and categorized their motivations into five groups: economic needs, such as earning extra income; family considerations, including opportunities for children to work on the farm; social aspects, such as educating tourists and meeting new people; the desire for independence, like having one's own career; and retirement provisions, such as securing retirement income or filling spare time. Barbieri (2010) explored agritourism in Canada and identified four key entrepreneurial goals: profitability, market-related goals, family-related objectives, and personal aspirations. The top motivations were to increase income, sustain farming operations, improve personal and family quality of life, diversify markets, and generate revenue from existing resources. In Italy, Santucci (2013) found that farmers diversified their activities into tourism to fully utilize their assets, engage family members in agritourism, and create employment opportunities.

Cassia et al. (2015) conducted a follow-up study in Italy and identified five motivations: economic, personal and family reasons, preserving and enhancing rural heritage, agri-food heritage, and the rural way of life. The study highlighted that personal and family motives were the most significant drivers for farmers, followed by the preservation and enhancement of the rural way of life and tangible rural heritage. Interestingly, the economic motive was considered the least important. Schilling et al. (2012), in their research on agritourism in New Jersey, USA, identified three key motivations for farmers: aside from the usual goal of generating additional revenue, they emphasized entrepreneurism, employing family members on the farm, and a desire for an agrarian lifestyle.

LaPan and Barbieri (2014) also explored the motivations for implementing agritourism, concluding that it is driven by a complex combination of goals. These include economic reasons (increased income), market motives (providing better service to current clients), and personal or family goals (enjoying a rural lifestyle). More recently, Chase et al. (2018) studied agritourism in Vermont, USA, and found that building goodwill within the community was a major factor for farmers to engage in agritourism. Other motivations included increasing revenue, educating the public about agriculture, and enjoying social interactions with visitors.

Drawing from these various studies, this literature review has identified common motives for farmers incorporating agritourism, like the findings of Van Zyl and Van der Merwe (2021) on South African farmers. Particularly, the economic, cultural, and social impacts of agritourism in rural areas remain underexplored, especially in developing countries (Lak and Khairabadi, 2022). In the context of a developing country like India, it is still uncertain whether farmers in Tamil Nadu share common motivations for adopting agritourism or if they have unique reasons shaped by their local environment. Gaining insight into these motivations will help policymakers in Tamil Nadu craft supportive measures to promote agritourism, fostering rural development, economic diversification, and cultural preservation.

3 Methodology

3.1 Study area and design

Grounded theory is particularly well-suited for this study, as it facilitates the creation of a theoretical framework that reflects the specific experiences of agritourism farm owners in Tamil Nadu. This approach is ideal for addressing the exploratory nature of the research, especially given that existing agritourism studies have largely concentrated on the demand side in developed countries. It provides a structured method to investigate the unique supply-side aspects in Tamil Nadu, such as farmers' motivations, operational challenges, and resource utilization.

Using methods like semi-structured interviews, field observations, and questionnaires, this theory enables for covering of key themes such as income diversification, cultural preservation, and operational barriers among agritourism owners. Its value lies in building a localized theory by examining the processes and interactions specific to the region, as noted by Thornberg and Charmaz (2014). This makes grounded theory especially valuable for under-researched areas like Tamil Nadu.

Additionally, this theory's adaptability allows the incorporation of qualitative insights with quantitative tools, such as Garrett ranking and Likert scale analysis, enhancing the research's comprehensiveness. Previous studies by Lak and Khairabadi (2022), Ollenburg and Buckley (2007), and Schilling et al. (2012) have demonstrated grounded theory effectiveness in producing practical frameworks for policy development and sustainable practices. By grounding the analysis in Tamil Nadu's socio-economic context, grounded theory not only contributes to academic understanding but also provides actionable policy recommendations to promote sustainable agritourism growth in the region.

In this study, agritourism farm owners were consulted to gain insight into the challenges and expectations related to agritourism. This study also employs a mixed-methods research design within a comparison-based case study framework to explore the supply-side dynamics of agritourism in Tamil Nadu. Incorporating the comparison-based case study approach, as described by Cihangir and Seremet (2022), strengthens the methodological rigor of this research by facilitating a systematic examination of various agritourism farms in Tamil Nadu. This approach enables the selection of diverse cases, encompassing farms of different sizes, and operational models, thereby offering a more practical discussion. The focus on qualitative methods allows for an in-depth understanding of farm owner's motivations, challenges, and expectations, contextualized within their lived experiences and operational realities.

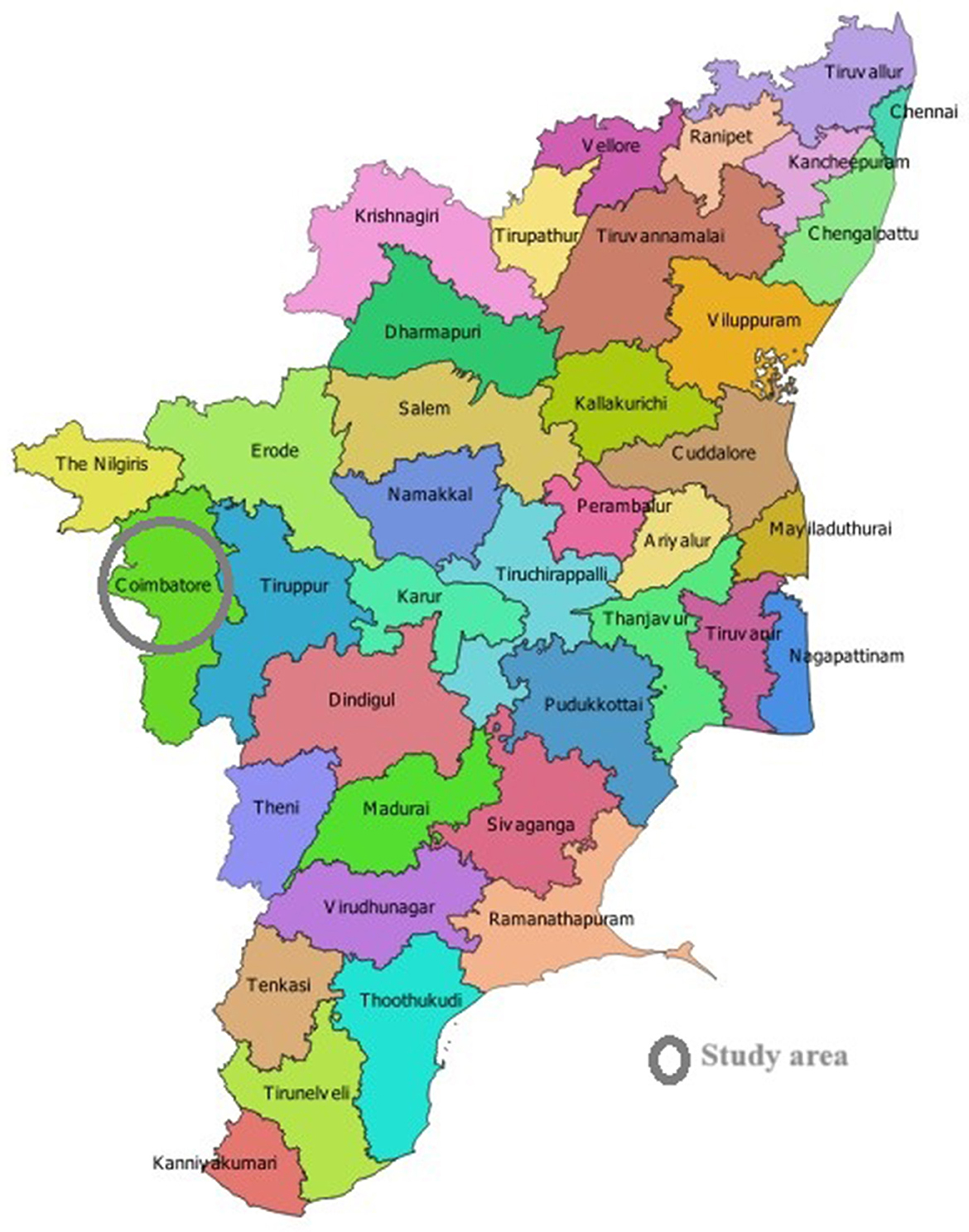

Coimbatore district was chosen as the study area because, in Tamil Nadu, Coimbatore has a greater number of agritourism farms. Apart from that Coimbatore is known for its rich cultural heritage and traditional farming. Using the purposive sampling design, a total of 20 agritourism farms (which were licensed under bed and breakfast) were selected based on the number of customer footfalls respectively to these farms, and the owners were contacted to gather information on the challenges they face, their expectations, motivations, and suggestions for promoting agritourism in the region. The relatively small sample size was chosen because it is appropriate for a case study design, where the goal is depth rather than breadth. The homogeneity of the sample (similar geographic location) supports this choice. Achieving data saturation (no new themes emerged) validates the adequacy of the sample size for qualitative analysis. The study area map is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Tamil Nadu map showing study area Coimbatore District (which has been rounded in the map) where the agritourism farms have been selected for exploring the supply side dynamics.

3.2 Data collection and analysis

A pilot study was conducted in the selected study area with five agritourism farm owners to test the clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness of the questionnaire. Participants from the pilot study were included in the main study due to the exploratory nature of the research and the limited number of agritourism farm owners in the study area, which necessitated maximizing data collection from this unique and small population. The pilot study primarily tested the clarity and cultural relevance of the questionnaire, and since only minor revisions were made, the data remained consistent and valid for inclusion. Furthermore, the detailed insights provided by pilot participants enriched the overall findings and contributed to a more comprehensive understanding of the topic. To mitigate potential bias from prior exposure to the questionnaire, these participants were treated uniformly with others during data collection, ensuring reliability and consistency across responses. Including them strengthened the research by providing valuable and representative data critical for achieving the study's objectives.

Questionnaires were then administered to selected agritourism farm owners to gather details on various aspects such as agritourism farm owner's operations, guest demographics, employee information, pricing, activities and services offered, environmental management practices, loan facilities, and their expectations from the government regarding agritourism. In the meantime, ethical considerations are paramount in research involving human participants to ensure their rights, dignity, and wellbeing are protected. In this study, ethical guidelines were strictly followed throughout the research process. Key ethical measures included obtaining informed consent from all participants, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity of the data collected, and providing the right to withdraw from the study at any stage without any repercussions. These steps ensured that the research was conducted responsibly, with respect for the participants' autonomy and privacy.

The collected data were analyzed using descriptive and percentage analysis. Percentage analysis was employed to examine general customer characteristics, including gender, age, education, agritourism farm owners' classification, and ownership. Meaningful conclusions were drawn from these basic statistical measures.

Garrett's ranking technique is a statistical method used to convert qualitative data (ranked preferences) into quantitative measures, making it easier to interpret and analyze. This technique assigns scores to each rank based on a formula that considers the number of items and the total number of respondents (Garrett and Woodworth, 1969). In this study, Garrett ranking was employed to assess the types of customers visiting agritourism farms, providing a systematic method to prioritize different customer categories based on farmer preferences or visitor feedback. This approach is instrumental in developing targeted strategies for agritourism by converting subjective rankings into easily interpretable scores. It helps identify the most significant customer segments, enabling agritourism farm owners to make informed decisions about their services and marketing efforts.

To understand the motivations of farmers engaging in agritourism, a Likert scale was used. Motivational statements were adapted from previous studies (Cassia et al., 2015; Chase et al., 2018; LaPan and Barbieri, 2014; Schilling et al., 2012; Van Zyl and Van der Merwe, 2021). The questionnaire utilized a five-point Likert scale, with respondents rating 12 motivational statements selected from above past studies, where five indicated strong agreement and one indicated strong disagreement. Triangulation was achieved by supplementing the questionnaire data with field observations and follow-up interviews, which enhanced the overall reliability and validity of the findings.

4 Results

The results section is organized into three parts: the demographic profile of the sample agritourism farmers, the types of activities they prefer to offer, and the reasons behind their decision to engage in agritourism on their farms.

4.1 General characteristics of sample agritourism farm owners

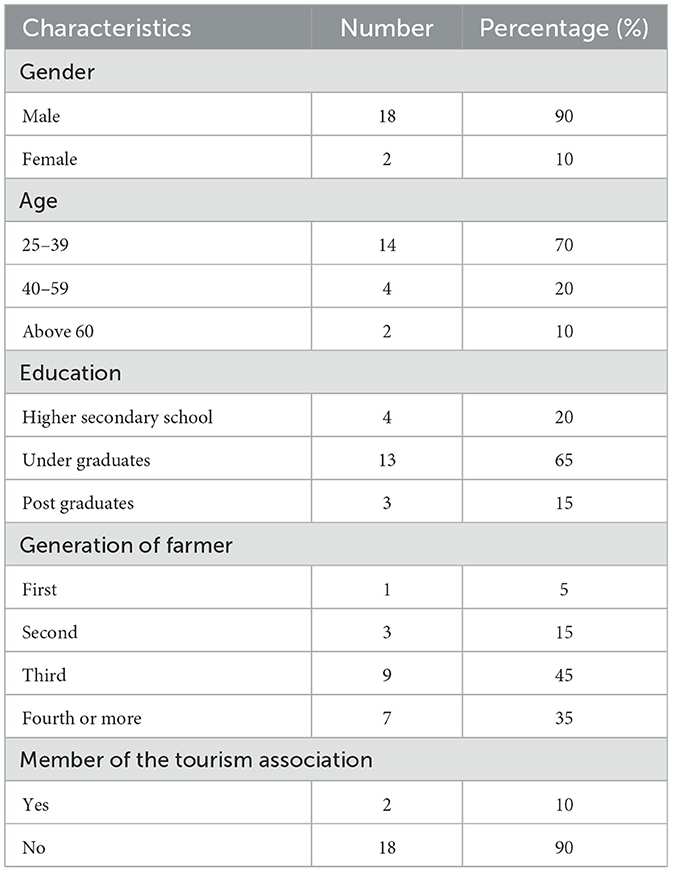

The general characteristics of sample agritourism farm owners including gender, age, education and farmer's generation are given in Table 1.

The survey of 20 agritourism farm owners in Tamil Nadu reveals that 90% are male, with 70% aged between 25 and 39 years, indicating that the sector is dominated by younger men. A notable 65% are undergraduates, while 15% are postgraduates, suggesting that agritourism is pursued by individuals with higher education.

Most respondents belong to multigenerational farming families, with 45% being third-generation farmers and 35% from the fourth or more generations, showing a strong tradition of farming among agritourism farm owners. However, only 10% of the respondents are members of a tourism association, reflecting limited formal collaboration within the sector. This data highlights a male-dominated, well-educated, and generationally experienced group, with significant potential for increased association involvement and networking.

4.2 Categories of agritourism farms and ownership

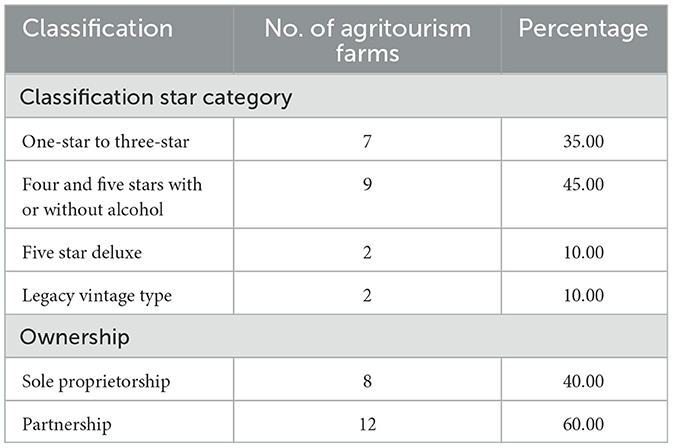

The Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, has classified hotels and agritourism farms into the following categories: one to three-star, four and five-star (with or without alcohol), five-star deluxe, heritage, and legacy vintage types. Agritourism farm ownership is primarily categorized into three types: sole proprietorship, partnership, and limited liability company. The results detailing the classification of agritourism farms by star rating and ownership type are provided in Table 2.

The data reveals that the majority of agritourism farms are classified in the four- and five-star category (45%), followed by those in the one- to three-star range (35%). There were no agritourism farm owners classified under the heritage category, as eligibility for this designation requires the property to have been built before 1950 with distinctive architectural features. Regarding ownership, it was observed that most agritourism farms operate under partnerships (60%), while the remaining 40% are owned by sole proprietors.

4.3 Types of customer visit

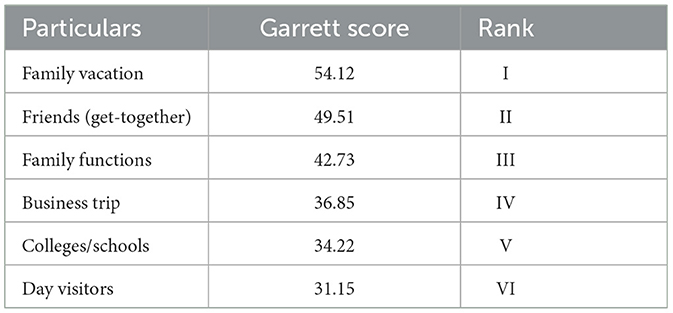

Customers visit agritourism farms for various purposes, including business trips, family vacations, family functions, gatherings with friends, visits from colleges or schools, and day trips. The agritourism farm owners ranked these different types of customer visits, with the results shown in Table 3.

From the table, it could be observed that family vacation was ranked first by agritourism farm owners with a mean score of 54.12 followed by friends (get-togethers), family functions and business trips. So, family vacation-type customers mostly visit agritourism farms for their leisure, and relaxation.

4.4 Agritourism activities and attractions

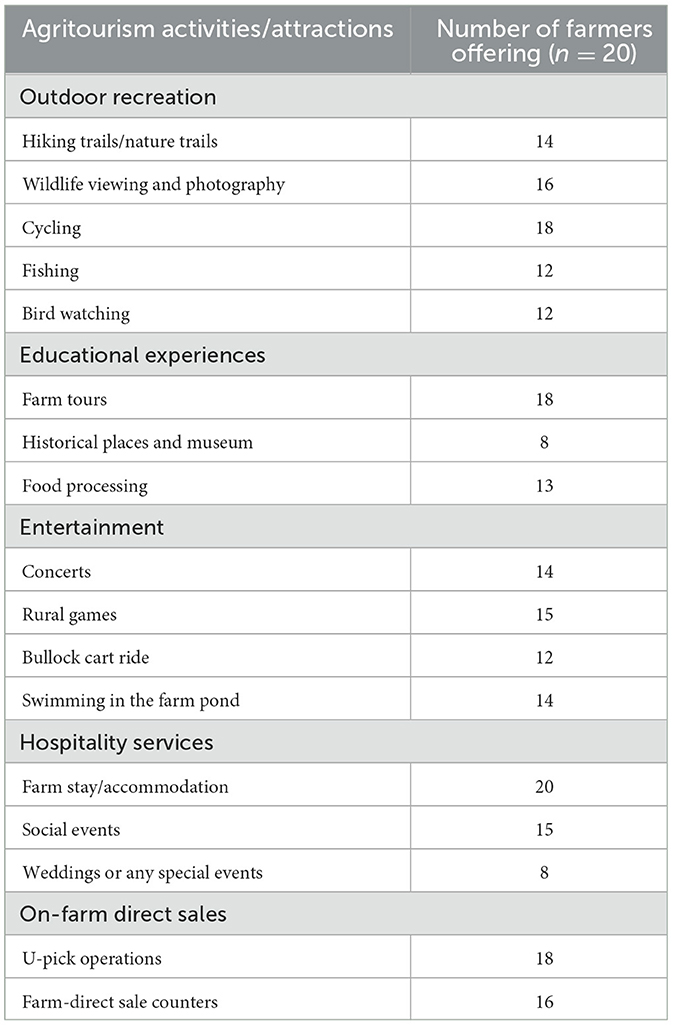

The agritourism activities and attractions have been classified under different categories such as outdoor recreation, educational experiences, entertainment, hospitality services and on-farm direct sales. The results are presented in Table 4.

The table highlights agritourism activities and attractions provided by 20 farmers, categorized into outdoor recreation, educational experiences, entertainment, hospitality services, and on-farm direct sales. Outdoor activities like cycling (offered by 18 farmers), wildlife viewing (16 farmers), and hiking trails (14 farmers) are popular, alongside fishing and bird watching (12 farmers each). Educational experiences are strong, with farm tours provided by 18 farmers, followed by food processing (13 farmers), though historical sites are less common (8 farmers). Entertainment offerings such as rural games (15 farmers), concerts (14 farmers), swimming in farm ponds (14 farmers), and bullock cart rides (12 farmers) indicate a focus on engaging visitors. In hospitality, all 20 farmers offer farm stay accommodations, and 15 provide social events, with eight hosting weddings or special events. On-farm direct sales are notable, with 18 farmers offering U-pick operations and 16 operating farm sale counters. The data suggests a strong emphasis on outdoor recreation, educational experiences, and hospitality services, with farmers focusing on activities that allow visitors to connect with nature, learn about farming, and immerse themselves in rural life. Additionally, the provision of accommodation and direct sales underlines agritourism's role in economic diversification, as farmers offer not just experiences but also products and services that enhance the visitor's stay. Popular activities like cycling, farm tours, and U-pick operations reflect the diversity of agritourism, catering to both recreational and educational interests.

4.5 Other facilities and management practices on the farm

The total area of the premises is crucial for any agritourism farm. Larger agritourism farm owners often offer ample parking, a variety of specialty crops, and other features. Among the 20 selected agritourism farms, the average area was ~20 acres, with the largest being 45 acres and the smallest three acres. Maharashtra's agritourism policy advises a minimum of 2.5 acres, with distinctive farm features, for agritourism operations.

The average number of customers visiting these agritourism farms was highest in 2019, with 1,027 visitors, followed by 961 visitors in 2018. However, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant negative impact on tourism, leading to a sharp decline in visitors between 2020 and 2021. This trend was also reflected in the occupancy rate, which dropped due to the pandemic. In hotels across India, the occupancy rate fell from 64.8% in 2017 to 33.8% in 2021 (Ministry of Tourism Report, 2022).

Staffing in agritourism farms was highest in departments like sanitation and farm guides, followed by room service and food and beverage divisions. Food and accommodation were the most charged services, followed by off-farm and on-farm activities. Additional activities, such as campfires, were charged up to Rs. 200. All selected agritourism farm owners offered food, accommodation, and campfire options. However, agritourism farm owners confirmed that there were no special packages for school students or seasonal festival discounts available.

All agritourism farm owners reported that first-aid facilities were available for customers, and on average, the nearest primary health center was located 6.2 kilometers from the agritourism farm owners. They also noted that no insurance coverage was provided for customers.

Nearly 40% of the energy used by agritourism farm owners came from renewable sources, while around 25% of the rainwater harvested and 20% of treated wastewater was utilized for gardening and cleaning purposes.

4.6 Agritourism farm owners motivations behind offering agritourism

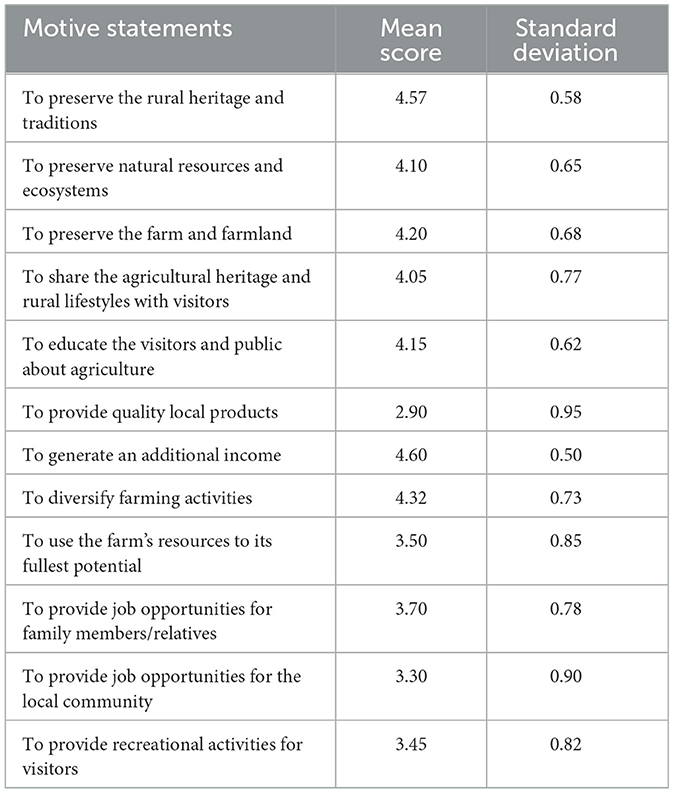

Agritourism farm owners motivations behind offering agritourism are influenced by various factors. To assess these, different statements from previous studies were identified and measured using a five-point Likert scale. The mean scores and standard deviations for these factors are presented in Table 5.

The analysis of farm owners motivations behind offering agritourism reveals a strong inclination toward preserving rural heritage, generating additional income, and diversifying farming activities. The highest mean score (4.60) reflects that agritourism is seen as a critical means of supplementing income, which is likely driven by the financial challenges faced by small and medium-sized farms. Closely following this, the preservation of rural traditions (4.57) and the desire to diversify farming activities (4.32) demonstrate farm owners commitment to safeguarding their cultural and agricultural heritage while seeking sustainability through diversified income streams. Additionally, they express significant motivation to educate the public about agriculture (4.15) and conserve natural resources (4.10), emphasizing their role as custodians of both the environment and rural knowledge. However, aspects like providing local products (2.90), recreational activities (3.45), and job opportunities for the community (3.30) rank lower, suggesting these are secondary objectives. Overall, the motivations are deeply rooted in preserving rural identity, ensuring farm viability, and using agritourism as a strategic tool for economic sustainability and education. This analysis suggests that while income generation and heritage preservation are the primary drivers for agritourism farm owners, there is potential to strengthen areas such as job creation and local product promotion, which could inform future development strategies for agritourism in the region.

5 Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Discussion

India's diverse landscape, rich in topography, culture, and traditions, offers world-class tourism services ranging from medical and adventure to agricultural and coastal experiences. Stakeholders in the travel and tourism industry are actively enhancing the sector's global appeal to boost tourist footfall, employment and revenue (Sanjeev and Birdie, 2019). This study results also show that the most significant motivation for farmers to engage in agritourism is the potential for economic gain (mean value: 4.60). Farmers need to maximize the use of their resources (farms) to generate income, as they face numerous challenges such as low education and skill levels among workers, limited access to credit, the pressures of globalization, the effects of climate change, water-related issues (both drought and flooding), and the inherent risks and vulnerabilities associated with farming. This finding aligns with research by Nickerson et al. (2001), who identified similar economic motivations for farmers offering agritourism in Montana, USA. Comparable motives were also observed by Ollenburg and Buckley (2007) in Australia and Van Zyl and Van der Merwe (2021) in South Africa, where additional income was deemed necessary, particularly considering family needs. However, this contrasts with findings from developed countries like Italy, where cultural preservation is often prioritized more highly. This discrepancy highlights the economic vulnerability in developing regions, where financial sustainability tends to be a more pressing motivation for agritourism adoption (Cassia et al., 2015).

In this condition, the government must encourage farmers to adopt agritourism by offering subsidies and incentives at the state level to benefit agritourism initiatives—positioning it as a key component of the broader tourism industry. Policymakers play a crucial role in transforming rural tourism to promote resilience (Augustyn, 1998; Brune et al., 2023). The goal should be to encourage tourists to engage deeply with rural life, not only through agricultural activities but also by experiencing local culture, traditions, cuisine, arts, and sports (Dsouza et al., 2022; Shah et al., 2023). Such an approach will enhance the destination's image (Alderighi et al., 2016; Choe and Kim, 2018), provide farmers with supplementary income beyond traditional agriculture, and offer tourists an authentic experience of the region (Choo and Park, 2020; Sims, 2009; Zhang et al., 2019).

To further promote this vision, the Government of India has undertaken bold initiatives to position India as a global leader in tourism by 2047. For example, the state of Maharashtra launched the Agritourism Development Corporation (ATDC) to encourage agritourism adoption by providing training and skill development programs to farmers (Maharashtra Agritourism Policy, 2020). In Kerala, the tourism department established the Kerala Agritourism Network as part of its responsible tourism initiative. This network aims to link farming activities with tourism to ensure financial benefits for the farming community. Inspired by these successful models, many other states are now incorporating similar initiatives to support agritourism and boost tourist activity in rural India.

However, agritourism farms in Tamil Nadu, which are licensed under the bed and breakfast (homestay) category by the tourism department, face several challenges. Farm owners who have taken loans from nationalized banks and other financial institutions are struggling due to the absence of a proper agritourism license. This lack of specific government guidelines and support is further complicated by limited public awareness, partly caused by insufficient marketing efforts. Additionally, while family visitors tend to avoid alcohol, individual guests often request it, presenting a unique challenge for farm owners.

To address these concerns, agritourism farm owners advocate for the government to establish a dedicated agritourism development committee to develop comprehensive policy guidelines. While targeted policies for agritourism are essential, they must be complemented by regional development policies. Regional policies are crucial for increasing agritourism revenue, as they focus on better utilization of local resources and endogenous potential, developing appropriate infrastructure networks, and providing the necessary services for tourists in a particular region (Kachniewska, 2015). Tourism policies impact various stakeholders, including government bodies, tourists, local communities, service providers, promoters, and employees. These policies influence community perceptions, employee-employer relationships, tourist footfall, and attitudes toward different facets of the tourism industry. Among these stakeholders, the government plays a pivotal role in shaping the sector and setting the direction for its future growth through well-crafted policies. In this context, government institutions can be viewed as complex and strategic assemblages composed of diverse and unique elements (Dean and Hindess, 1998).

The process of developing sustainable tourism policies requires up-to-date knowledge collected using advanced analytical tools (Agarwal and Somanathan, 2005; Wu et al., 2021), a component that is often lacking in current approaches. Moreover, the interconnected nature of tourism with industries such as logistics, food and beverage, real estate, and banking underscores the need to recognize agritourism's impact on these sectors—an aspect often overlooked in policy frameworks.

Generally, tourism policies in many states and Union Territories of India are typically designed based on industry needs, exogenous changes, and available information. However, these policies are frequently outdated, reflecting a need for more agile and responsive policy updates—something that is not always feasible for governments. Agritourism, still in its nascent stages in India, holds tremendous potential as a unique blend of agriculture and tourism (Dsouza et al., 2024). Despite this promise, setbacks from service providers and policymakers hinder its progress as a significant segment of India's tourism industry. Deep-rooted cultural values, such as farmers' attachment to their land, often discourage diversification into agritourism due to limited awareness and information. Moreover, some existing policies generally lack specific provisions for the advancement of agritourism, with most failing to provide clear support in the form of subsidies, loans, or state-funded investment plans.

Travelers seeking agritourism experiences are primarily motivated by the desire to connect with the authenticity of rural life. To meet this growing demand, agritourism service providers—including farmers and promoters—need strong foundational support through tourism policies. The current lack of clarity and direction on financial schemes, resource assistance, and incentives remains a significant barrier to the development of agritourism. With agriculture in India gradually progressing toward success, integrating tourism can provide farmers with additional income opportunities and reduce their financial vulnerability.

To address these challenges, agritourism policies need to be strengthened with clear definitions, transparency, and well-articulated goals. Robust and transparent policy-making could help establish agritourism as a major contributor to India's tourism sector. Agritourism is growing at a notable pace, but it requires policies that maintain a proper separation between formulation and implementation, as suggested by Dsouza et al. (2024).

Farm owners also call for a separate licensing category for agritourism, which would facilitate easier access to loans and tax benefits. They recommend organizing training programs for agritourism development and maintenance, with cooperative societies playing a role in offering loan facilities. Additionally, integrating agritourism into school curricula and emphasizing unique regional tourist attractions could help increase its visibility. Connecting the increasingly urban population with agricultural issues is vital for improving agricultural literacy among current and future generations, enabling the public to make informed decisions about food consumption and purchasing, and promoting food and fiber sustainability, production, safety, and security (Knollenberg et al., 2018; Mars and Ball, 2016; Tew and Barbieri, 2012). Within the context of agritourism, these learning experiences provide the public with opportunities to learn about agriculture and related environmental, economic, and health issues.

To better promote agritourism, farm owners suggest organizing seasonal or harvest festivals to increase outreach, and listing agritourism farm owners on the Tamil Nadu Tourism Department's website. They also recommend involving Self Help Groups (SHGs) in food preparation and training local youth as farm guides, which would not only boost employment but also foster local engagement. Strengthening agritourism has far-reaching effects on the local economy, contributing not only directly to agricultural revenue but also indirectly by enhancing public investment and attracting external capital to rural areas (Ammirato et al., 2020). Agritourism experiences can positively influence consumer behavior toward local food by emphasizing its value to the community, providing enjoyable and memorable experiences, and highlighting the cultural and territorial connections of local products (Brune et al., 2023).

The success of agritourism relies on a holistic approach that prioritizes all stakeholders, including communities, artisans, policymakers, local authorities, service providers, self-help groups (SHGs), and tourists. Effective agritourism policies should establish clear channels for information dissemination, consistent follow-up, and regular reviews. Recognizing the complementary roles of state and central governments in policy development and implementation, it is essential to refine existing provisions and grant states and Union Territories greater flexibility to create responsive and effective agritourism frameworks.

To address current challenges and promote the growth of agritourism, a few key policy recommendations have been developed based on the expectations and suggestions of agritourism farm owners. A comprehensive agritourism policy has the potential to strengthen the ecological resilience of rural India, preserve cultural heritage, and enhance farmers' economic stability. By fostering an inclusive policy framework, agritourism can drive rural development, ensuring that the benefits are equitably shared among all participants in the rural economy, ultimately contributing to a thriving and resilient rural India. These recommendations include the establishment of a dedicated agritourism development committee by the State Government to create specific guidelines, such as the prohibition of restricted substances and ensuring customer safety. The state tourism department should issue distinct licenses for agritourism, enabling operators to access loans and tax benefits, with co-operative societies potentially providing loan facilities. Local administrations like village panchayats should assist in coordinating agritourism initiatives due to their influential role in local communities.

Additionally, the state tourism department should organize seasonal festivals with agritourism farms to boost visibility, while promoting the adoption of digital technologies and internet infrastructure in rural areas. Training programs offering diplomas or certifications in agritourism should be provided to rural youth to enhance their skills. Increasing awareness through online and social media platforms, such as Incredible India and Enchanting Tamil Nadu, is essential, alongside developing digital booking platforms and including agritourism in state promotional campaigns. Marketing efforts should involve partnerships with travel trade networks and online platforms to leverage their expertise. Finally, to improve hospitality services, professional training for agritourism farms should be mandated, with state-organized workshops to enhance the hospitality skills of farm owners and local communities, ensuring a better customer experience.

From a managerial perspective, these policies offer several implications for agritourism farm owners and policymakers. Farmers should diversify their revenue streams by offering varied activities such as educational tours, outdoor recreation, and cultural experiences to attract wider audiences and boost profitability. Highlighting cultural and environmental preservation can serve as a unique marketing tool, appealing to eco-conscious and cultural tourists. Agritourism farm owners should enhance visitor experiences through interactive and educational activities like farm tours and hands-on workshops while prioritizing sustainable practices to protect the rural environment and attract responsible travelers. Although job creation may not be the primary focus, agritourism farm owners can increase local employment and community involvement, enriching visitor experiences and fostering local support. Membership in tourism associations can also help agritourism farm owners access resources, training, and promotional opportunities.

Policymakers should provide tailored support through financial incentives, training programs, and infrastructure development to strengthen the sector. These actions will create a dynamic, sustainable, and culturally enriching agritourism experience that benefits both visitors and rural communities.

5.2 Conclusion

Agritourism encompasses a wide range of activities and experiences provided by farm owners, offering unique opportunities in developing countries compared to developed ones (Bhatta and Ohe, 2020). Given the limited experience in implementing agritourism in developing regions, it is logical to attract tourists through public learning based on socioeconomic contexts (Varmazyari et al., 2018). This study focuses on the supply-side dynamics of agritourism, examining farmers' general characteristics, the variety of activities they offer, and their motivations for participating in agritourism.

Bhatta and Ohe (2020) and Savage et al. (2023) highlighted the importance of promoting women's roles in agritourism, maintaining farm quality standards, providing subsidies, and carefully planning tourism development. Encouraging stakeholder involvement and minimizing societal impacts through innovation can foster sustainable growth. However, challenges such as inadequate infrastructure, lack of education and training, insufficient funding, and the need for improved waste management and environmental protection persist, as noted by Malkanthi and Routry (2011). The role of small-scale businesses is crucial in advancing agritourism within the rural economy, but further research is needed, especially in developing countries, to understand how to address issues like cross-sectoral coordination in policymaking and funding (Lak and Khairabadi, 2022).

The analysis of farmers' general characteristics shows that agritourism is predominantly led by younger men, mostly from third-generation farming families, indicating a strong familial connection to agriculture. Agritourism serves as a modern extension of their traditional practices, with nearly all farm owners offering food services, entertainment, educational experiences, and outdoor recreational activities, highlighting the sector's multifaceted nature.

Farmers' primary motivations for engaging in agritourism are to generate additional income and preserve rural heritage and traditions. This reflects a balance between financial stability and cultural preservation, making agritourism appealing as it offers an alternative revenue stream while showcasing rural traditions.

The study's policy recommendations emphasize promoting sustainable agritourism development. Strategies should enhance economic viability while ensuring the preservation of rural ecosystems, cultural heritage, and farming communities. By fostering sustainability, agritourism can continue providing economic opportunities for farmers and maintaining the rural landscapes and traditions that attract visitors. These recommendations aim to guide future initiatives to support the sector's growth and sustainability, benefiting both providers and visitors.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SDS: Conceptualization, Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agarwal, O., and Somanathan, T. (2005). Public policy making in India: issues and remedies. Indian J. Public Policy 4, 56–72.

Alderighi, M., Bianchi, C., and Lorenzini, E. (2016). The impact of local food specialities on the decision to (re)visit a tourist destination: market-expanding or business-stealing? Tour. Manag. 57, 323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.016

Ammirato, S., Felicetti, A. M., Raso, C., Pansera, B. A., and Violi, A. (2020). Agritourism and sustainability: what we can learn from a systematic literature review. Sustainability 12, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/su12229575

Anil and Roshan.. (2021). Agri-tourism Market by Activity, Sales Channel: Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast 2021–2027. Allied Market Research, Maharashtra.

Arru, B., Lupi, C., Giaccio, V., Mastronardi, L., and Scardera, A. (2021). Agritourism as a strategy for supporting small and medium-sized farms: a case study of Sardinia, Italy. Land Use Policy 64, 383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.104104

Augustyn, M. (1998). National strategies for rural tourism development and sustainability: the polish experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 6, 191–209. doi: 10.1080/09669589808667311

Baby, J., and Kim, D.-Y. (2024). Comprehensive evaluation of agritourism visitors' intrinsic motivation, environmental behavior, and satisfaction. Land 13:1466. doi: 10.3390/land13091466

Baipai, R., Chikuta, O., Gandiwa, E., and Mutanga, C. N. (2024). An assessment of the extent to which agricultural farms meet the requirements for sustainable agritourism in Zimbabwe. Cogent Soc. Sci. 10:2347015. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2024.2347015

Barbieri, C. (2010). An importance-performance analysis of the motivations behind agritourism and other farm enterprise developments in Canada. J. Rural Community Dev. 5, 1–20.

Barbieri, C. (2014). Assessing the sustainability of agritourism in the US: a comparison between agritourism and other farm entrepreneurial ventures. J. Sustain. Tour. 21, 252–270. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2012.685174

Bernardo, D., Valentin, L., and Leatherman, J. (2004). Agritourism: if we build it, will they come? Risk Profit Conference: Manhattan, KS, 19–20.

Bhatta, K., and Ohe, Y. (2020). A review of quantitative studies in agritourism: the implications for developing countries. Tour. Hosp. 1, 23–40. doi: 10.3390/tourhosp1010003

Brune, S., Knollenberg, W., and Vilá, O. (2023). Agritourism resilience during the COVID-19 crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 99:99. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2023.103538

Butler, L. M., and Flora, C. B. (2024). “Expanding visions of sustainable agriculture.” in Developing and Extending Sustainable Agriculture, eds. C. A. Francis, R. P. Poincelot, and G. W. Bird (London: CRC Press), 203–224.

Cassia, F., Bruni, A., and Magno, F. (2015). “Heritage preservation: Is it a motivation for agritourism entrepreneurship?” in Proceedings of the 27th Annual Sinergie Conference (Campobasso, Italy), 565–574.

Chang, H.-H., Mishra, A. K., and Lee, T.-H. (2019). A supply-side analysis of agritourism: evidence from farm-level agriculture census data in Taiwan. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 63, 521–548. doi: 10.1111/1467-8489.12304

Chang, T.-C. (2003). Development of leisure farms in Taiwan and perceptions of visitors thereto. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 15, 19–41. doi: 10.1300/J073v15n01_02

Chase, L. C., Stewart, M., Schilling, B., Smith, B., and Walk, M. (2018). Agritourism: Toward a conceptual framework for industry analysis. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 8, 13–19. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2018.081.016

Choe, J. Y., and Kim, S. (2018). Effects of tourists' local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 71, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.11.007

Choo, H., and Park, D.-B. (2020). The role of agritourism farms' characteristics on the performance: a case study of agritourism farms in South Korea. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 23, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/15256480.2020.1769520

Cihangir, E., and Seremet, M. (2022). “The comparison-based case study approach in hospitality and tourism research,” in Contemporary Research Methods in Hospitality and Tourism (Routledge), 221–236. doi: 10.1108/978-1-80117-546-320221015

Contini, C., Scarpellini, P., and Polidori, R. (2009). Agri-tourism and rural development: the Low-Valdelsa case, Italy. Tour. Rev. 64, 27–36. doi: 10.1108/16605370911004557

Dean, M., and Hindess, B. (1998). Governing Australia: Studies in contemporary rationalities of government. Cambridge: University Press.

Del Chiappa, G., and Baggio, R. (2015). Knowledge transfer in smart tourism destinations: analyzing the effects of a network structure. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 4, 145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.02.001

Deville, A., Wearing, S., and McDonald, M. (2016). Tourism and willing workers on organic farms: a collision of two spaces in sustainable agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 111, 421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.071

Deya, B. (2019). Growth of agricultural tourism in India. Bus. Eco. Available online at: https://businesseconomics.in/growth-agricultural-tourism-india (accessed February 14, 2025).

Dsouza, K. J., Shetty, A., Damodar, P., Dogra, J., and Gudi, N. (2024). Policy and regulatory frameworks for agritourism development in India: a scoping review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 10:2283922. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2023.2283922

Dsouza, K. J., Shetty, A., Damodar, P., Shetty, A. D., and Dinesh, T. K. (2022). The assessment of locavorism through the lens of agritourism: the pursuit of tourist's ethereal experience. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 35, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2022.2147566

Garrett, H. E., and Woodworth, R. S. (1969). Statistics in psychology and education. Vakils, Feffer and Simons Pvt. Ltd. 1, 1–329.

Kachniewska, M. A. (2015). Tourism development as a determinant of quality of life in rural areas. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes. 7, 500–515. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-06-2015-0028

Khanal, A., and Mishra, A. (2014). Agritourism and off-farm work: survival strategies for small farms. Agric. Econ. 45, 65–76. doi: 10.1111/agec.12130

Kirschenmann, F. (2003). New Seeds and Breeds for a New Revolution in Agriculture. Seeds Breeds Conf.: Washington, D.C.

Kline, C., Barbieri, C., and LaPan, C. (2016). The influence of agritourism on niche meats loyalty and purchasing. J. Travel Res. 55, 643–658. doi: 10.1177/0047287514563336

Knollenberg, W., Stevenson, K., Grether, E., and Barbieri, C. (2018). “Introducing a framework to assess agritourism's impact on agricultural literacy and consumer behavior towards local foods,” in Proceedings from the 2018 Travel and Tourism Research Association International Conference: Advancing Tourism Research Globally (Miami, FL, United States).

Lak, A., and Khairabadi, O. (2022). Leveraging agritourism in rural areas in developing countries: the case of Iran. Front. Sustain. Cities 4:863385. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.863385

LaPan, C., and Barbieri, C. (2014). The role of agritourism in heritage preservation. Curr. Issues Tour. 17, 666–673. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.849667

Liu, S.-Y., Yen, C.-Y., Tsai, K.-N., and Lo, W.-S. (2017). A conceptual framework for agri-food tourism as an eco-innovation strategy in small farms. Sustainability 9:1683. doi: 10.3390/su9101683

Lupi, C., Giaccio, V., Mastronardi, L., Giannelli, A., and Scardera, A. (2017). Exploring the features of agritourism and its contribution to rural development in Italy. Land Use Policy 64, 383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.03.002

Malkanthi, S. P., and Routry, J. K. (2011). Potential for agritourism development: evidence from Sri Lanka. J. Agric. Sci. 6, 45–58. doi: 10.4038/jas.v6i1.3812

Mars, M., and Ball, A. (2016). Ways of knowing, sharing, and translating agricultural knowledge and perspectives: alternative epistemologies across non-formal and informal settings. J. Agric. Educ. 57, 56–72. doi: 10.5032/jae.2016.01056

Matyakubov, M., Rakhimbaev, A., Rocchi, B., and Turaev, O. (2022). An evolutionary framework of Italy agritourism development: actual experience for the acceleration of the agritourism growth in Uzbekistan. Theor. Appl. Sci. 6, 406–414. doi: 10.15863/TAS.2022.06.110.72

McGehee, N. G., and Kim, K. (2004). Motivation for agri-tourism entrepreneurship. J. Travel Res. 43, 161–170. doi: 10.1177/0047287504268245

Ministry of Tourism Report (2022). Annual Report 2021–2022. New Delhi: Ministry of Tourism, Government of India.

Naidoo, P., and Sharpley, R. (2016). Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community well-being: the case of Mauritius. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 5, 16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.11.002

Nickerson, N. P., Black, R. J., and McCool, S. F. (2001). Agritourism: motivations behind farm/ranch business diversification. J. Travel Res. 40, 19–26. doi: 10.1177/004728750104000104

Ohe, Y., and Ciani, A. (2011). Evaluation of agritourism activity: facility based or local culture based? Tour. Econ. 17, 581–601. doi: 10.5367/te.2011.0048

Ollenburg, C., and Buckley, R. (2007). Stated economic and social motivations of farm tourism operators. J. Travel Res. 45, 444–452. doi: 10.1177/0047287507299574

Peira, G., Longo, D., and Pucciarelli, F. (2021). Rural tourism destination: the Ligurian farmers' perspective. Sustainability 13, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/su132413684

Phelan, C., and Sharpley, R. (2011). Exploring agritourism entrepreneurship in the U.K. Tour. Plan. Dev. 8, 121–136. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2011.573912

Sanjeev, G. M., and Birdie, A. K. (2019). The tourism and hospitality industry in India: emerging issues for the next decade. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 11, 355–361. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-05-2019-0030

Santucci, F. M. (2013). Agritourism for rural development in Italy: evolution, situation, and perspectives. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 3, 186–200. doi: 10.9734/BJEMT/2013/3558

Savage, A. E., Barbieri, C., and Jakes, S. (2023). “Cultivating success: personal, family and societal attributes affecting women in agritourism,” in Gender and Tourism Sustainability (Routledge), 248–268. doi: 10.4324/9781003329541-16

Schilling, B. J., Sullivan, K. P., and Komar, S. J. (2012). Examining the economic benefits of agritourism: the case of New Jersey. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 3, 199–214. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2012.031.011

Shah, G. D., Gumaste, R., and Shende, K. (2023). Allied farming-agro tourism is the tool of revenue generation for rural economic and social development analyzed with the help of a case study in the region of Maharashtra. Sustain. Agri Food Environ. Res. 11, 1–15. doi: 10.7770/safer-V11N1-art362

Sharpley, R., and Vass, A. (2006). Tourism farming and diversification: an attitudinal study. Tour. Manag. 27, 1040–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.10.025

Sims, R. (2009). Food, place and authenticity: local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 17, 321–336. doi: 10.1080/09669580802359293

Sotomayor, S., Barbieri, C., Wilhelm-Stanis, S., Aguilar, F., and Smith, J. (2014). Motivations for recreating on farmlands, private forests, and state or national parks. Environ. Manag. 54, 138–150. doi: 10.1007/s00267-014-0280-4

Tchetchik, A., Fleischer, A., and Finkelshtain, I. (2008). Differentiation and synergies in rural tourism: estimation and simulation on the Israeli market. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 90, 553–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8276.2007.01112.x

Tew, C., and Barbieri, C. (2012). The perceived benefits of agritourism: the provider's perspective. Tour. Manag. 33, 215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.005

Thornberg, R., and Charmaz, K. (2014). “Grounded theory and theoretical coding,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, 153–169. doi: 10.4135/9781446282243.n11

Van Zyl, C. C., and Van der Merwe, P. (2021). The motives of South African farmers for offering agri-tourism. Open Agric. 6, 537–548. doi: 10.1515/opag-2021-0036

Varmazyari, H., Asadi, A., Kalantari, K., Joppe, M., and Rezvani, M. R. (2018). Predicting potential agritourism segments on the basis of combined approach: the case of Qazvin, Iran. Int. J. Tour. Res. 20, 442–457. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2195

Wu, J. S., Barbrook-Johnson, P., and Font, X. (2021). Participatory complexity in tourism policy: understanding sustainability programmes with participatory systems mapping. Ann. Tour. Res. 90:90. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103269

Keywords: agritourism, supply side, farm owners, motivations, expectations

Citation: Sennimalai S, Rao BV and Sivakumar SD (2025) Exploring the supply side dynamics of agritourism in Tamil Nadu. Front. Sustain. Tour. 4:1498749. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2025.1498749

Received: 19 September 2024; Accepted: 27 January 2025;

Published: 18 February 2025.

Edited by:

Chiedza Ngonidzashe Mutanga, University of Botswana, BotswanaReviewed by:

Mehmet Seremet, Yüzüncü Yil University, TürkiyeRudorwashe Baipai, Zimbabwe Open University, Zimbabwe

Copyright © 2025 Sennimalai, Rao and Sivakumar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarath Sennimalai, c2FyYXRoczE5OTVAZ21haWwuY29t

†Present address: Sarath Sennimalai, KCT Business School, Kumaraguru College of Technology, Tamil Nadu, India

Sarath Sennimalai

Sarath Sennimalai Badiya Venkata Rao2

Badiya Venkata Rao2