95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Tour. , 04 December 2024

Sec. Behaviors and Behavior Change in Tourism

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsut.2024.1482203

Introduction: In the context of the internet economy era, historic cities face increasing pressure to attract tourists through effective urban design strategies. Immersive districts, particularly in historic Chinese cities, have emerged as an innovative approach to enhance tourism experiences, achieving notable success. This paper explores the use of immersive design strategies in the Guitanglou (簋唐楼) district in Xi'an, China, with a focus on gamification theory.

Methods: The study employs in-depth interviews and content analysis to examine the design strategies employed in the Guitanglou immersive district. Through these methods, the research investigates how immersive experiences can be used to enhance tourist engagement in historic sites.

Results: The research introduces a “4S” design model, consisting of Scene, Socialization, Story, and Stimulus. The model suggests that by innovating design within these four key areas, tourists can engage more deeply with the immersive district, resulting in stronger cultural resonance and emotional connections.

Discussion: This study offers new insights into tourism and urban design, highlighting how immersive districts can serve as effective platforms for disseminating historical and cultural values. The findings suggest that leveraging communication strategies familiar to digital natives can create a balance between cultural preservation and economic growth, offering a fresh perspective on urban design in historic settings.

As the cultural tourism industry continues to evolve, the standardized mass tourism model that developed in the 1960s and 1970s is becoming obsolete, no longer meeting the sophisticated demands of today's consumers (Poon, 1994; Timothy and Boyd, 2006). Changes in values and lifestyles driven by new communication technologies, increased wealth, more leisure time, and heightened awareness of personal needs and social responsibilities have shaped a new generation of tourists. These tourists are not only more individualistic but are also more interactive and willing to engage in travel projects (Gretzel et al., 2005; Jenkins, 2006). Millennials, in particular, are set to dominate the travel market over the next decade. Having grown up in the internet era and starting their careers during economic downturns, their consumption behaviors are markedly different; they seek rationality and authenticity in the experiences they procure (Sofronov, 2018; Skinner et al., 2018; Benzecry and Collins, 2014).

The shift in consumer preferences changes the fundamental dynamics of the travel industry and significantly influences product and service design, including urban planning and block management. In this context, the Tourist Block generally refers to a city's important symbolic historical and cultural landscape. Many cities regard it as an essential tool for shaping urban characteristics and competitiveness (Liang et al., 2022). Although spontaneous experiences are difficult to manipulate, creating and managing a sense of genuine pleasure is achievable (Jelinčić and Senkić, 2019). Therefore, successful designers are those who not only focus on enhancing the quality of tourism products but also cater to the evolving demands of a diverse consumer base (Şchiopu et al., 2016). Nowadays, tourism products, services, and urban environments are increasingly designed to allow tourists to immerse themselves in local cultures, even becoming locals during their visits (Jelinčić, 2019). The aforementioned trend toward transformational design holds particular importance for cities rich in historic heritage resources.

Nowadays, the concept of tourism progress is changing rapidly, but the development of historical and cultural cities is often constrained by traditional concepts, resulting in many resources not being fully used for more innovative application (Fang, 2023). However, early-stage tourism development in historical and cultural cities without pre-planning has led to a bottleneck of homogenization of commercial development today (García-Hernández et al., 2017).

Some scholars, drawing on empirical cases from China's cultural and historical tourism sector, have indicated that the traditional commercial tourism development model is increasingly inadequate in addressing contemporary market demands, resulting in a decline in tourist numbers (Fan et al., 2008). Even in Xi'an, one of the earliest cities in China to explore immersive development, its most famous immersive district – “Datang City Never Sleeps”(大唐不夜城)'s operating body Xi 'an QUJIANG CULTURAL TOURISM CO., LTD., had a net profit of−187 million yuan in the first half of 2024, which not only turned from profit to loss, but the margin of loss increased by more than 15 times year-on-year.1 According to the semi-annual report released by Xi 'an TOURISM CO., LTD.,2 which represents the overall tourism operation in Xi 'an, the revenue in 2024 was 252 million yuan, a decrease of 10.03% over the same period last year. The net loss reached 63.66 million yuan, representing a 26.68% increase from the first half of 2023.3

The traditional tourism development mode and the earlier exploration of the immersive district operation mode have fallen into the disadvantage in the fierce market competition. How to change the business strategies and further enhance the attraction of tourists has become an important issue in the current development of tourist sites.

In addressing these practical problems, current studies generally tend to focus on the commercial planning of cultural tourism cities (Wang et al., 2018; Guimarães, 2021), policy management (Lak et al., 2019), sophisticated environmental design (Bonn et al., 2007; Shang and Yao, 2024; Tayhuadong and Inkarojrit, 2024) to propose solutions for these historical and cultural old cities. However, in this era of new media, the service design of tourist sites cannot simply pursue sensory stimulation but need to go deep into the demands of consumers and match the corresponding text. Factors including narratives and stories are increasingly becoming key drivers and influences of visitor perception and behavior, highlighting a further shift in the experience economy (Moscardo, 2021). This approach can enhance their perception of “existential authenticity”, so as to better enhance tourist loyalty, which is the key to the development of urban historical districts (Luo et al., 2024).

Therefore, in the construction of tourist blocks, a single design element is not sufficient. Designers must have a relatively comprehensive set of concepts in order to help realize the consumer demand of tourists for personalized deep experience. Considering the above factors, this paper is committed to building such a set of systematic theoretical models to supplement the specific dimensions worth considering in the planning of tourist blocks through qualitative research. In this regard, the questions raised in this paper include: What emotions do consumers (tourists) of immersive blocks specifically experience in different dimensions of immersion? Why do these emotions enhance the experience? What kind of learning and reference can these different dimensional feelings bring to the designers of cultural tourism blocks?

Currently, the practice cases of some tourist districts in China provide a good reference for the construction of this research model, and fully demonstrate the overall preference of tourists in the process of tourism experience. In order to revitalize historic districts, many cities have made great efforts to open up tourism and carry out various cultural activities.

To revitalize historic districts, many cities have made great efforts to open up tourism and carry out various cultural activities (Bosone et al., 2021). China's historical and cultural cities have also realized that shaping local characteristics and showing their local history and geographical image to the outside world can greatly improve their comprehensive competitiveness, so they vigorously carry out commercial development (Wang et al., 2019). In the list of the first batch of national smart tourism immersive experience new space cultivation pilot projects announced by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and other departments of the Chinese government in 2024, Xi 'an, Chengdu, Kaifeng, Wuhan, Yangzhou, Hangzhou, Beijing, Pingyao and other historical cities are on the list, reflecting the enthusiasm of historical and cultural cities for the construction of immersive experience space, and received strong support from the state. Among them, Guitang Lou belongs to “Xi 'an Datang Never Night City”, which won the 11th ITIA Award, the Best New Tourism Project Award in China, and the 6th Longque Award in the Cultural Tourism Industry in 2022, the Best Immersive Experience Complex Award. It is an important exploration in the transformation of cultural tourism in the Xi 'an Datang Never Night City. Therefore, Guitang Lou, a representative of these immersive blocks, is chosen as the study case in this paper, aiming to add a theoretical model for the development and design concept of tourist blocks that fully incorporates factors affecting consumer experience.

The tourism urban design of historic cities in the tourism sector necessitates a thorough understanding and evaluation of consumers' experiential demands, with targeted design linkages. Consumers' attitudes, interests, and opinions play a critical role in the design process of travel products (Gonzalez and Bello, 2002). In addition to this basic space creation, what other elements will affect the consumer experience in the tourist district? Many studies have also launched relevant exploration on this issue. Distinguished from general cultural entertainment, consumers in the tourism industry are ontologically situated across multiple dimensions—time, context, body, and interaction—necessitating a multidimensional approach from urban designers (Lindberg et al., 2014). Although the perception layers of tourists at historic sites can be categorized into entertainment, cultural identity-seeking, education, relationship development, and escapism (Lee and Smith, 2015), revisiting historical periods through leisure and entertainment experiences remains a core component of heritage tourism (Kempiak et al., 2017; McCain and Ray, 2003; Millar, 1989), with the motivation for recreation often surpassing that for learning (Liang, 2022).

In discussions of historical and cultural tourism, addressing consumers' demand for authenticity is crucial. Sarah Gardiner and other scholars have emphasized the need for staged authenticity in historical heritage tourism experiences (Gardiner et al., 2022). They argue that staged authenticity, which aligns with educational, entertainment, escapism, and aesthetic experiential values, has a significant positive correlation with attitudes toward recreating experiences, thus promoting staged authenticity and the reproduction of historical eras as new modes of tourism experience (Gardiner et al., 2022). Traditionally, this staged representation of reality in travel often referenced cinematic and television experiences, overlooking the potential of video games (Rainoldi et al., 2022). Yet today, with consumers deeply valuing experiential authenticity, video games also wield considerable influence and can serve as effective marketing tools for designers and a means of deeper interaction with tourists (Xu et al., 2016).

The ongoing exploration of game studies has brought gamification design to widespread attention. Some research suggests that there is a positive correlation between travel experience and memory and the willingness to visit again (Lee, 2022). In cultural tourism field, gamification mechanism can positively impact tourists by providing a memorable experience, rather than just pastime (Paixão and Cordeiro, 2021). Other studies have demonstrated that gamification in cultural heritage tourism can facilitate tourists' psychological (enjoyment, flow experience, and loyalty) and behavioral outcomes (knowledge gain) (Lee, 2019). However, in the past gamification development models for tourism of cultural heritage sites, many studies focused on the technical aspects, emphasizing the transformation of cultural attractions through the installation of specific interactive facilities (Prandi et al., 2019). Nevertheless, some scholars have sought to explore the specific aspects of gamification mechanisms affecting consumer perception. In the past gamification development models for tourism of cultural heritage sites, many studies still focused on the technical level, emphasizing the transformation of cultural attractions through the installation of specific interactive facilities (Prandi et al., 2019). Nevertheless, some scholars still tried to explore the specific aspects of gamification mechanism affecting consumer perception. Drawing on Schmitt's SEMs model (Schmitt, 1999), Michal Mochocki has proposed five key dimensions of player engagement in his pursuit of authenticity and immersion at heritage sites through gamification development:

These dimensions outline the consumer immersion knowledge in heritage tourism (Mochocki, 2021). Although this model primarily focuses on electronic games, it is informed by comprehensive research on game experience by Calleja (2011) and Bowman (2018), offering valuable references for the physical space design.

Mochocki suggests that the design of role-playing patterns in physical historic sites predates those in video games, using the term Live Action Role Playing (LARP), historically employed in educational, psychological, business, or medical fields (Harviainen et al., 2018; Song et al., 2022). Myriel Balzer delineates four dimensions to differentiate the real world from the constructed virtual game world surrounding LARP (2011):

To sum up, in the research on consumer cultural and entertainment experience, both Mochocki's and Balzer's theories emphasize the importance of space, theme/story-telling, and social interaction, forming a basic framework for consumers to achieve deep immersive experiences in gamified, interactive, and participatory contexts. When applied in the context of historic cities, these insights not only facilitate innovative design and transformative development but also enhance the realization of intangible tourism assets and more actively engaging forms of tourism consumption (Richards and Wilson, 2006). Therefore, learning from the success of electronic games to boost consumer participation in physical interactions within historic urban settings remains a pivotal topic in urban design and tourism mechanism design.

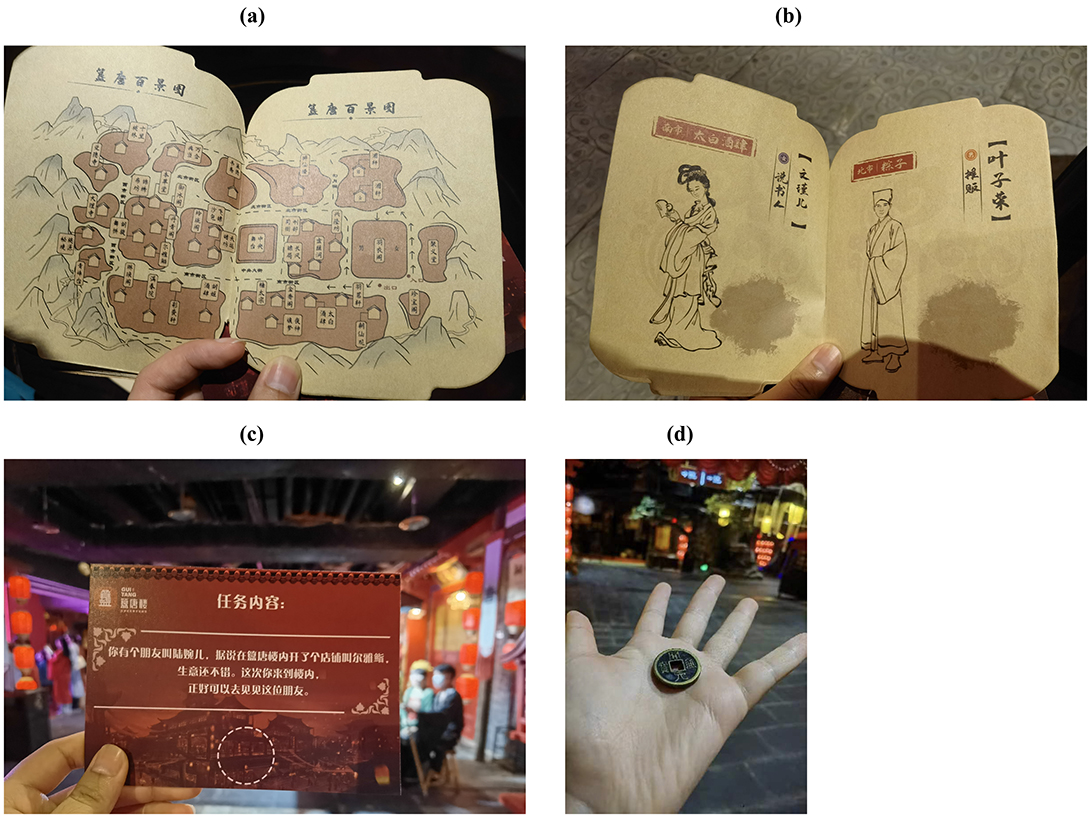

To thoroughly explore the design strategies of immersive blocks, this paper investigates Guitanglou (簋唐楼) as a case study. Located in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China, Guitanglou spans nearly 20,000 square meters. This site functions as a commercial travel destination and was officially opened in October 2021. The design approach of Guitanglou incorporates elements of Live Action Role Playing (LARP), providing participants with substantial autonomy. Visitors at Guitanglou can engage in typical activities such as sightseeing, photography, and shopping. Additionally, they have the opportunity to assume specific roles, don costumes, and immerse themselves in various narratives, thereby experiencing life from alternative perspectives (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1. Guitanglou block note: the images were captured during field research: (A) depicts the interior layout of the block; (B) illustrates the character setup; (C) outlines the task specifications; and (D) showcases the block's token.

Xi'an, known as one of the cradles of ancient Chinese culture, served as the capital city for thirteen dynasties in China. Renowned for its numerous historic sites like the Mausoleum of the First Emperor of Qin (秦始皇陵), the Terracotta Warriors (兵马俑), and the Dayan Pagoda (大雁塔), Xi'an attracts a large number of tourists annually. A vital source of cultural tourism design in Xi'an is the rich history and culture of the Tang Dynasty. Xi'an's significance stems from its long-standing status as the capital of the Tang Dynasty, an era highly revered by Chinese people. The Tang Dynasty boasted a flourishing economy, social stability, active diplomacy, diverse culture, and art, embodying a high degree of international influence. It symbolizes the illustrious history and cultural achievements of Chinese civilization on the world stage (Ng et al., 2016; Zhu and Yang, 2017; Lin et al., 2020), and the Chinese often refer to themselves as “Tang People.”

Recent official data released by the Xi'an government revealed a 64% increase in tourism orders during the Spring Festival in 2024 compared to the previous year. Xi'an emerged as the top destination for domestic inbound tourism, with the most frequented site being the “Datang City that Never Nights (大唐不夜城)” area.4 It is within this context that the Guitanglou block was launched, aligned with the Tang Dynasty theme and harmonizing closely with the city's historical and cultural heritage.

Presently, China features several blocks similar to Guitanglou, such as “Twelve Hours of Chang'an” (长安十二时辰) in Xi'an and “Xifan Li” (嘻番里) in Beijing. These blocks, set in renowned historic cities, adopt comparable designs and incorporate familiar modes of live-action game interactions found in traditional public cultural spaces like theme parks, museums, and commercial streets from earlier years. The interactions involve storytelling, open-air theatrical performances, tour guide role-playing, and task-based challenges (Fu et al., 2023; Tseng, 2022; Hansen and Mossberg, 2017; Prentice, 2001; Jafari et al., 2013), albeit with unique innovation.

Guitanglou stands out as a popular choice among such block cases, as indicated by comprehensive rankings on various social media platforms. It is, therefore, selected as the focal case for this study based on its exceptional popularity and intriguing features.

Designers should actively observe and analyze consumers' behaviors and feedback to gain insights into the concept of “immersion”. Subjective evaluation and expression are key in determining the success of a project and objectively measuring its effects, especially considering the various psychological elements involved. When consumers experience a sense of immersive presence, they often enter a state of deep concentration. A common approach to measuring this state is through subjects' self-reports (Lombard and Ditton, 1997). In this study, interviews were employed to collect firsthand data.

The selection of research participants was done through snowball sampling to ensure diverse perspectives. In this study, snowball sampling was used to reach the target participants. Snowballing is a common sampling method for qualitative research, mainly used to recruit consumer groups that are not easy to reach directly (Marcus et al., 2017; Reagan et al., 2019). Since the customers participating in Guitanglou are engaged in the experience, it is difficult for researchers to speak with them directly without disruption. Therefore, the researchers initially contacted the groups who had participated in Guitanglou outside the block, and then contacted additional relevant consumers through the groups they had already interacted with. Semi-structured interviews were conducted based on Mochocki et al.'s framework, covering aspects such as consumers' environmental perceptions, content assessment, emotional states, overall feedback on the experience, and likelihood of being repeat customers (see Appendix A). Twenty-five consumers who had engaged with the Guitanglou Block experience were randomly selected. Considering the clarity of these responses, detailed records of 13 interviews are included in the paper's Appendix B.

To protect the privacy of interviewees, coding was done using the interview date and serial number (e.g., 230403V1 for the first interviewee on April 3, 2023). Each interview lasted between 45 and 60 min and was conducted online (see Table 1). Further information is available in the attached documents.

Combined with Mochocki and Balzer's two models, which have been widely used in the field of immersion experience research in the past, this study conducted a detailed comparative analysis based on the qualitative analysis results of the interview records (see the following detailed table for keywords). It can be seen from the analysis that neither of the two models mentioned above can fully meet the needs of theoretical exploration and model construction at this stage, or some key elements are missing, or the connotation and importance of some elements have changed in the new context. Firstly, it is found that there are some elements in the two models that are not applicable to the research context. On the one hand, affective involvement in Mochocki's model is not a design element that can exist independently, but as a purpose that runs through every link of activities in tourist blocks. Therefore, it is difficult to guide designers in practice. On the other hand, the temporal level in Balzer's model is also a special dimension. Because the object of his research focuses on LARP (live-action role play) activities with specific time arrangements. However, in a space-based project such as a tourist block, the designer does not need to design the immersion experience of tourists according to the strict time constraints, but focuses on bringing better experiences to tourists, and there is no clear time limit. In addition, the business model of the subjects studied in this paper is also different from that of Balzer: the longer the immersive block can retain tourists, the higher the commercial profits it can bring, and the stronger the sense of belonging of tourists. Therefore, considering the above factors, we need to further optimize the model of consumer experience based on the theoretical model of these two theorists and the object of “tourist block”, so as to provide designers with a better reference model.

Meanwhile, according to the characteristics of the selected research topic and the key points in actual industrial application, this essay integrates the elements with strong reference significance in the model mentioned above and updates the key aspects. Since this research aims to better extract the specific feelings of different tourists in the immersive block through qualitative data, this paper adopts an inductive approach to extract the frequency of words in the interviewees' discourse and uses NVivo to analyze the interview texts to investigate the respondents' attention to the corresponding topics. In this paper, researchers combined the interview analysis and existing literature to obtain the overall category and subdivision coding of the 4S model. Since all our interviews were conducted in Chinese, when sorting out the experience of the interviewees, we first extracted the Chinese semantics and encoded the English version as accurately as possible.

The results of the qualitative analysis of the interview texts revealed four main themes related to immersion: scene, social, story and stimulation (referring to Table 2 for details).

In the context of designing tourist blocks with a focus on gamification, a critical priority is the meticulous construction of the overall environment. This aspect serves as the initial point of contact for tourists upon entering the block, shaping their first impressions significantly. Effective spatial design exerts a profound visual influence on tourists, leaving a lasting impact. For example, an interviewee suggested that the scene is very well arranged, and it often feels like a winding path leading to a secluded place. For example, when walking on a busy street, you might find a shady side path lined with bamboo that leads directly to a Taoist temple. This place is very rich in both audio and video [230411V1, female]. Other than that, according to respondents, the essence of the Guitanglou block extends beyond its stark contrast with the “real world” exterior; it is also rooted in the interior's sense of comfort and authenticity. For example, one visitor mentioned that there was a special atmosphere in the block, just like jumping into ancient times [230409V1, female]. These environmental atmospheres, which are different from those of conventional tourist blocks, have brought a strong sense of impact to many interviewees.

In developing immersive blocks within the gamification framework, the design process encompasses both the “hardware” components, such as the physical scenery and environmental setup, and the essential “software” elements that revolve around the involvement of service providers (i.e., the official block performers) and other participants (i.e., fellow visitors). While performers possess a degree of autonomy, their actions, behavioral patterns, and overall flow of interaction primarily align with the predetermined design blueprint.

One of the most frequently mentioned topics is interacting with NPCS. For example, an interviewee expressed: “What I like about it very much is that it provides a sense of immersion through the construction of real-life houses and streets, everything is real but new. I think this is a particularly interesting thing. It opens in the morning and closes at night, and all the NPCs in it seem to be living in real life” [230511V1, female]. This professional performance can make great contributions for tourists to gradually adapting to the life and social mode in the immersive block. In addition, a variety of collective rituals of different scales also bring reasonable context to these social interactions. For example, “There will be a show in the block every half hour. I remember one performance of witchcraft that was visually stunning [230410V1, female]”. The intensive activities not only build the social circle of the block, but also promote the engagement and participation of tourists.

The narrative content serves as the vital core of the creative blocks, forming the foundational basis for consumers to deeply engage with the immersive game experience during their visit. The continuous innovation and enhancement of the story text play a pivotal role in captivating consumers' attention, ensuring the block remains dynamic in breaking stereotypes. Designers adeptly intertwine fresh stories with both “software” and “hardware” elements to sustain the project's appeal. Upon entry into the immersive block, each consumer is provided with a unique storyline comprising character backgrounds and core clues integrated into the pre-established setting (refer to Figure 2). This narrative further unfolds through the consumer's active participation, engagement, and firsthand experience. In Guitanglou block, although the stories are based on certain text settings, they are not all inevitable, but with strong randomness and flexibility. For example, one interviewee told an interesting story he encountered in the block: “The NPC's dialogue in Guitanglou would not be a long reading script like the Secret of Murder Game, but would give an immersive interaction. For example, in order to earn token money, tourists may steal the token on the table while the NPC was not paying attention—but once caught, he would be taken to the court by an officer from Dali Temple—the policeman in ancient China [230414V1, female]”. In the collection of stories made up of such interesting “small events”, visitors can more fully integrate and trust the stories they experience and participate in.

An immersive site that offers a worthwhile experience necessitates effective gamification strategies to encourage visitor engagement. By strategically implementing diverse tasks and goals, participants are provided with a clear behavioral direction within the block, fostering heightened levels of involvement. While interviewees in this study expressed both positive and negative impressions of Guitanglou, there was a notable consensus on the importance of physical and psychological encouragement in enhancing their experiences.

For example, more than one respondent [230406V1, male; 230411V1, female; 230410V2, female] mentioned that the game tasks in the block were too easy and could be appropriately increased in difficulty to enhance playability. At the same time, some respondents also mentioned: “We can earn silver tickets inside, and the motivation to do so is to buy fake flowers from NPCs to vote in the contest. We used real Chinese Yuan to buy food and souvenirs, while we used the fake silver tickets to buy flowers and vote for our friends.” [230416V1, female] Getting emotional feedback from peers and even strangers through cooperation and competition are also an effective incentive model. Therefore, through a rich variety of tasks and rewards, visitors can be further mobilized to participate in the enthusiasm.

Empirical research identifies four key dimensions that are closely related to consumer experience, consolidating crucial factors highlighted in previous research. This research is based on the theoretical achievements of immersion perception contributed by Mochocki and Balze, and considers that if their theoretical model can be applied to the block practice dimension.

This study introduces a novel model termed the “4S model,” tailored specifically for the design of cultural tourism within historic cities. The model comprises the dimensions of Scene, Story, Stimulus, and Socialization.

These four design dimensions of consumer experience are intricately intertwined, representing various layers of immersion perception that progressively deepen the overall experience. The scene design facilitates a sensory transition from two-dimensional visuals to a three-dimensional environment, providing a tangible backdrop for consumer activities that evoke a sense of reality and credibility. Interactive design, on the other hand, transitions consumers from passive observers to active participants, generating a dynamic spatial experience through the engagement of performers and fostering feelings of identity and belonging. Story design shifts narrative frameworks toward more open-ended structures, constructing a coherent inner world that resonates with consumers and fosters a sense of connection and understanding. Finally, the stimulus design leverages gamification mechanisms to captivate consumers' attention, guiding them from aimless exploration to focused engagement, ultimately leading to a sense of accomplishment and fulfillment.

By incorporating these four design dimensions, consumers are guided through a progressive immersion experience, encouraging deeper levels of engagement and participation (refer to Figure 3 for a visual representation).

Immersive blocks comprise a diverse array of tangible scenes, acting as the central focus for designers. Scenes serve as the convergence points of cultural phenomena, providing coherence (Straw, 2015) and embodying a new way of life characterized by value exchange and emotional connections. In the context of immersion construction, space, environment, and scenes form the essential foundations. This underscores the notion that objects must first be perceived before they can be truly understood, as emphasized by Mochocki (2021, p. 958–960). Additionally, the concept stresses the necessity of delineating reality from the surrounding environment, a process known as defamiliarization, as articulated by Balzer (2011, p. 82).

However, Mochocki and Balzer's previous theoretical discussion of spatiality basically focused on the description of physical space. In fact, the reason why this paper changed the name of this dimension to “scene” is that it is not only a simple spatial element, but also includes the functions of different buildings and various elements within it—these together constitute the stage for people to carry out activities. Meanwhile, the word “stage” itself also emphasizes that everyone has the opportunity to show themselves on it, and this possibility for everyone to show themselves is particularly important in today's personalized society.

The development of environmental scenes is geared toward facilitating authentic consumer experiences. A superior authentic encounter not only fosters tourists' willingness to engage but also bolsters trust levels, influencing overall satisfaction levels (Park et al., 2019; Domínguez-Quintero et al., 2020). Wang (1999) distinguished between objective, constructive, and existential authenticity, whereby tourists gravitate toward existential and postmodern authenticity during positive consumption experiences (Xu et al., 2022). Consequently, authenticity holds paramount significance in cultural tourism scene design, particularly among participants.

The comfort and artistic merit embedded within scene design are irreplaceable components. Physical space design encompasses visual elements along with multi-sensory factors like light, temperature, and odors (Spence, 2020), which, when meticulously curated, create a harmonious and inviting environment for consumers to immerse themselves. Moreover, the aesthetic dimension of urban spaces plays a pivotal role in enhancing tourist experiences, influencing their perception of existence authenticity (Carù and Cova, 2013). The aesthetic design of urban spaces has been shown to have a positive impact (Silver and Clark, 2016), and designers can leverage a good aesthetic experience to enhance tourists' perception of the authenticity of their surroundings (Genc and Gulertekin Genc, 2023). Respondents' favorable remarks on the aesthetics of Guitanglou, highlighting elements like “beautiful scenery” and a “sense of time travel,” [230414V1, female; 230409V1, female] underscore the significance of artistic sensibilities in satisfying contemporary consumers.

In the realm of scene design, it is essential to establish a clear demarcation between tourism spaces and their external surroundings, fostering a psychological transition zone. Moreover, attention to the comfort and intricacy of the spatial landscape is crucial to instill trust and appreciation among tourists. Continuous efforts to reinforce the internal world's coherence are instrumental in ensuring tourists derive authentic and fulfilling experiences. Designing with a focus on these four dimensions facilitates a deeper consumer perception of the scenes (refer to Figure 4).

In the realm of “socialization,” the concept involves the swift adaptation to new contexts and social norms through social interactions. This enables individuals to momentarily detach from real-life constraints and engage in a virtual alternative. Establishing and fostering social connections is paramount in the creation of immersive experiences. Wang (1999, p. 364–365) highlighted the importance of interpersonal authenticity, stressing the distinct status individuals assume when they embark on travels, transitioning into a unique mental state separate from their daily routines.

Social mechanisms play a pivotal role in the design of immersive blocks. The underlying principle underscores that individuals can fully embrace their roles only when they embrace and nurture new interpersonal ties within participatory community immersion (Mochocki, p. 960). This facilitates complete immersion in the roles designated by designers, enabling participants to distinguish this fabricated role from their real-world persona (Balzer, p. 82).

While Mochocki called this social interaction shared involvement, Balzer stopped at the social level. In the actual interaction process, tourists can not directly enter the shared state of experience and cognition, but need a gradual socialization process. Therefore, “socialization” becomes the name for the current theoretical model. Just as people need to gradually become familiar with the environment in the game, the social design under the gamification mechanism also includes such a gradual and in-depth process.

In order to ensure the realization of this goal, several different subject relationships should be taken into account in design procedure:

Firstly, the interaction between individual participants and performers plays a crucial role in creating immersive experiences. Rather than passively observing performances, empowering tourists with the autonomy to make decisions and take initiative in performances holds more significance (Smith, 2013). This dynamic necessitates performers, functioning as staff members, to exhibit heightened professionalism and actively involve participants in the narrative they weave (Bagnall, 2003). For instance, performers at Guitanglou, portraying ancient figures, display genuine curiosity about participants' interactions with mobile devices, fostering a more authentic engagement [230511V1, female]. This approach enables visitors to fully inhabit their roles and enhances their overall experience. As respondent 230410V1 [female] said: “The NPCs there are very involved in the play and very immersed in their roles, it will bring up the feeling of every tourist.” Therefore, during the design phase, meticulous consideration must be given to factors such as performer allocation, role guidance, and communication strategies to cater to the diverse needs of tourists effectively.

Secondly, it is the interaction among participants that forms a community of shared interests. Within the context of burgeoning social media platforms, tourists are increasingly building connections based on ideas, resources, and mutual interests (Dickinson et al., 2017). Many core connections among consumers at Guitanglou revolve around shared fandom interests like “Hanfu” (traditional Chinese costume) and “murder role-play games,” fostering a sense of camaraderie [230407V1, female; 230416V1, female; 230511V1, female]. These shared interest relationships present an ideal community model that transcends social hierarchies, enabling open communication and immersive enjoyment (Wang, 1999). In designing these interactions, it is imperative to create spaces and opportunities that facilitate communal communication among consumers.

Thirdly, the ritual of collective interaction between performers and participants serves as a crucial design element. By consolidating dispersed groups during collective ceremonies, like the talent competition at Guitanglou, a distinct cultural facet is unveiled, fostering a robust sense of identity and community among participants (Turner et al., 2017). In addition to individual interaction design, designers should also prioritize aspects like frequency, objectives, and thematic alignment of collective rituals within the block. This holistic approach aims to bolster participant connection and enrich the overall immersive experience.

In the realm of interaction design, special consideration should be given to diverse and transient forms of relationships and network connections across several dimensions: firstly, elevating the professionalism of non-player characters (NPCs) is crucial to facilitate tourists' immersion in the context; secondly, tourists engaging with the block should be encouraged to engage in interactive and communicative activities to overcome feelings of isolation; and lastly, as a temporary “community,” designers ought to enhance consumers' overall sense of belonging to the block through meticulously planned cultural celebration ceremonies (refer to Figure 5).

The narrative presentation and portrayal are collaborative processes, where compelling stories and themes can effectively engage consumers, instill belief, enhance emotional resonance, and elevate their overall travel experience (Doyle and Kelliher, 2023; Moscardo, 2010; Jolliffe and Piboonrungroj, 2020).

Story design encompasses the crafting of character backstories and the development of a player avatar's new biography (Mochocki, p. 960). This involves exploring event-specific or mundane topics that deviate from real-life scenarios within the immersive setting (Balzer, 2011).

In this dimension, Mochocki and Balzer's models name narrative model and topical model respectively. The former focuses on narrative techniques, while the latter lacks discussion on the integrity of the story. However, the actual analysis of this research found that only emphasizing narrative skills or showing fragmented content could not improve tourists' attention and recognition. Only complete, systematic and content-rich stories could arouse people's interest and stand out in the competition of similar tourism projects. Therefore, the third S proposed in this article is the Story, which contains a more complete plot and persuasive cultural content, and will be used for the purpose of evoking emotions, rather than just as a technique to promote immersion.

In Guitanglou, participants are assigned unique identities upon entering the block, each entailing distinct storyline requirements, such as the obligation for a successor from a wealthy family to rejuvenate their lineage. Participant actions are met with corresponding consequences based on their worldview within the immersive narrative framework. For instance, as mentioned by the 230414V1 [female] interviewer, participants engaged in activities like “stealing” in the streets are subjected to “ruling” and “punishment” in adherence to the story's regulations. The “Dali Temple,” serving as an ancient Chinese legal entity, oversees the execution of such measures within the narrative.

In the story design of the block, there is a strong relationship between the quality of the story and its theme as well as structure. Moscardo (2020) divides the story features in the tourism system model into three sections: pre-experience, emerging experience and post-experience stories. In the design of the immersive block, the three aspects are slightly different:

In the pre-experience story design phase, visitors' attention revolves around the depth and coherence of the narrative background within the block. This pre-established storyline serves as a crucial information source influencing their planning and decision-making processes (Moscardo, 2017). As the experience unfolds, the story design stage becomes pivotal, with consumers seeking twists and originality in the plot. Unlike the conventional linear storylines, modern tourists are inclined toward co-creating their narratives during on-site tourism experiences, leading to dynamic content influenced by various factors (Moscardo, 2021). Post-experience storytelling shifts focus toward constructing lasting impressions and evaluations. Travel memories merge into personal narratives shared with others, shaping visitors' perceived destination memories and intentions for future visits (McCabe and Foster, 2006; Kim and Youn, 2017).

Overall, consumers' perception of the immersive block's story experience hinges on its richness, novelty, openness, and freedom. As respondent 230511V2 [female] put it, “Guitanglou's story is more comprehensive, and I am willing to experience different roles again.” Good stories help to promote tourists' secondary consumption of the tourist block. In today's tech-driven landscape, narrative possibilities continually evolve, embracing characteristics like analog, user-generated, participatory, and synchronous elements (Ryan, 2006). This innovation in narrative potential also impacts the design trends of story modules within physical scenic locations. Therefore, successful story design within blocks should prioritize coherent background narratives, foster novelty and diversity in narrative progression, and seamlessly integrate initial settings with mid-stage developments to ensure a logically structured and engaging narrative journey for consumers (refer to Figure 6).

Visitor engagement in tasks and challenges represents the most gamified aspect of immersive block design, offering a pathway to spur innovative travel experiences. Such engagements have the power to evoke strong emotional responses, foster positive intrinsic motivation, and ignite a desire for sustained participation (la Cuadra et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2013; Cupchik, 2001). As the respondent 230508V1 [male] said, “I think it will be more fun once it has the design of solving problems.” Appropriate challenges in tourist blocks can make tourists feel more significance of traveling. While Mochocki and Balzer's research primarily focuses on the gaming realm, transitioning to non-game domains necessitates leveraging game awards to imbue motivational stimuli.

In Mochocki's theoretical model, activity-immersion is an effective way to enhance immersion experience. Nevertheless, the activity is just a pure external behavior, in order for visitors to participate in a truly immersive experience, it is still necessary to add feedback and personalized content to the block. As found in the empirical research in this paper, ordinary group activities tend to make people lack the willingness to participate. On the contrary, people prefer those special activities with enough freedom, strong customization and autonomy, which enables them to master the rhythm and have higher leadership, and therefore they are more willing to enhance communication with the environment and enhance immersion. Therefore, this model innovatively proposes a dimension of Stimulus to enhance tourist experience in tourist neighborhoods.

Currently, gamification serves as a vital tool for cultivating engagement across diverse industries. Games effectively capture participants' attention through elements such as control and physical movement (kinesthetic engagement), collaboration and competition with peers (co-engagement), emotional responses during gameplay (emotional engagement), and pursuit of objectives (fun engagement) (Calleja, 2011). Implementing game components in non-game contexts involves weaving together compelling narratives, establishing clear rules and objectives, presenting well-balanced challenges with prompt feedback, facilitating social interactions and relationships, among other elements (Stadler and Bilgram, 2016, p. 363–364).

Instant feedback and challenging mechanics play a pivotal role in transitioning into non-game activities (Berger et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2016). This motivational mechanism is characterized by the persistence and accumulation of tasks, often manifested through systems such as token rewards, upgrades, badge achievements, and more (Manzano-León et al., 2021). External rewards typically yield positive psychological effects on game participants, with their influence extending to tourist attractions (Kim et al., 2021; Kawanaka et al., 2020; Jang and Kim, 2022); self-earned rewards notably enhance participants' willingness to engage (Nofal et al., 2020). Within immersive blocks, the intrinsic value of rewards transcends mere commodity significance, often embodying emotional benefits that resonate deeply with consumers. Moreover, in the realm of group activities, fostering cooperation and competition effectively heightens individual emotional investment in the gamification process, fostering robust value co-creation (Leclercq et al., 2017). The collaborative spirit within the block serves as an additional motivational force, propelling participants to actively pursue task goals, thus showcasing their value effectively.

In conclusion, the gamification incentive design significantly influences consumers' immersive experiences within immersive blocks. Therefore, emphasizing the design of tasks and activities in which tourists partake is essential. Designers should firstly prioritize appropriate task difficulty adjustments; secondly, provide rich sub-level variations, bolster diverse material and intangible incentives; thirdly, promote team-based competitive and cooperative dynamics, and finally elevate participant attention, emotional engagement, and sense of accomplishment throughout the process (refer to Figure 7).

Based on the above discussion, it can be found that in the design of immersive blocks, the external environment (the first S) is only a basic condition in attracting tourists. In fact, this is also the most important link in the current research on the development of tourist blocks. However, there are many other factors that are still overlooked—namely the other three “S”—which also play an important role in the development of tourist blocks at this stage. Among them, through the establishment of interpersonal connection, social interaction enables participants to better meet the needs of belonging and increase playability; The quality of the story text is easy to be ignored, but it is the key to retaining people and giving the deep cultural value; Motivation can help people increase their attention, while strengthening the memory of the play with positive feedback.

In the context of declining consumer attraction to historical tourist blocks, many current studies tend to solve the problem by focusing on external space construction to strengthen the superficial sensory stimulation for consumers and other commercial means (Mansilla and Milano, 2022). However, through empirical research, this paper finds that for many consumers, in addition to the environmental factors of the neighborhood, there are many other factors that can deepen tourists' travel experience, especially focusing on the improvement of virtual text stories, interactivity and incentives. This study combines relevant theories of gamification mechanism to build this 4S model.

Although scholars represented by Mochocki and Balzer had already discovered the impact of gamification factors on experience and authenticity in tourism/heritage research and proposed specific independent variable dimensions respectively, their researches were still limited to a single “game” or “project” model, which does not take into account the overall development needs of the current historical city tourist block—the latter needs to consider the freedom of consumers in the play process, as well as the significance of these historical and cultural cities themselves.

This paper introduces the 4S framework crucial in cultural tourism block development, comprising scene, social, story, and stimulus elements. In addition, the paper also tries to extend the consumer experience framework developed by Mochocki and Balzer from gamification projects to immersive tourist district design from the theoretical level. Scene design entails considerations such as segregation, comfort, artistic value, and authenticity. Social design encompasses diverse interaction modes among participants, between participants and performers, inter-block group dynamics, and external group interactions. Story design progresses through stages involving world-building richness in the early phase, multiple narrative directions in the middle phase, and diverse ending options in the latter phase. Stimulus design encompasses features like task complexity, level intricacy, reward diversity, and team collaborations. In addition, according to the analysis of the in-depth interview of Guitanglou consumers, it can be concluded that while Guitanglou has some advantages in aforementioned aspects, there is still room for further improvement. For example, in terms of environment, comfort issues such as light and temperature need to be further considered. In terms of actor interactions, it is necessary to avoid the sense of fragmentation caused by occasional “play” details (such as shift changes, etc.). The story can further be enriched by incorporating more diverse character scripts. In terms of motivation, the relationship between material and spiritual motivation should be balanced.

The practical significance of this research lies in offering specific insights for the development and design of cultural tourism projects at historical sites to enrich consumer experiences. It also provides transformation strategies for cities abundant in historical and cultural resources, aiming to strike a balance that ensures heritage preservation while meeting visitors' satisfaction. The theoretical innovation significance of this study extends beyond by enhancing the existing consumer perception model in gamification development of historic sites. This research broadens its scope to present a more holistic design concept for immersive tourist block projects, enhancing logical coherence among the four levels and providing detailed enhancements in the subdivided design elements. This study introduces a new theoretical model, refines existing theories applied in virtual gaming, and introduces a theoretical framework adaptable to the evolving consumer landscape, thereby fostering interdisciplinary cross-innovations.

While the study boasts commendable attributes, it is not devoid of limitations. The restricted sample size and scope of objects present constraints in this study. Given the evolving nature of Guitanglou, consumers visiting during different periods may exhibit varying experiences and perceptions. Moreover, being rooted in a contemporary Chinese context, the research bears potential regional biases. Therefore, a recommendation is made to conduct cross-cultural studies to discern perception disparities between local and international visitors, assessing the universality of consumer psychology. Furthermore, this research primarily delves into tourists' immersion perceptions, neglecting the significant realm of digital technology within immersion theory. The exploration of VR, AR technology, and the nuances between virtual and reality stands as a pertinent issue warranting future exploration within immersive project design.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by School of Arts, Peking University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft. JL: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsut.2024.1482203/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Data resources: https://www.qjtourism.com//storage/posts/August2024/jgTW8LSIJvdbKUYTyRJT.pdf

2. ^Tourism state-owned holding listed company, there are more than 30 subsidiaries, including hotels, catering, tourism, scenic spots, property, ecological industry and so on.

3. ^Data resources: https://www.xatourism.com/upload/files/2024/8/ebdf95ca0bb3d74e.PDF

4. ^Business Xi 'an Evening News (2024, February 18). “西安年” 出圈報告 [Report on “Year of Xi 'an”]. mp.weixin.qq.com/s?_biz=MzA4MTYzNzA1MA==&mid=2655679465&idx=2&sn=f6d32cdd34a542466803fc4144749a3e&chksm=842f283cb358a12a19291d789d5c1e64f53d86a51cbb3942473956d82297219fd245d2e710c2&scene=27

Bagnall, G. (2003). Performance and performativity at heritage sites. Museum Soc. 1, 87–103. doi: 10.29311/mas.v1i2.17

Balzer, M. (2011). “The creation of immersion in live role-playing,” in Larp Frescos, Volume II: Affreschi moderni, 79–90. Available at: http://www.neliepixel.com/LarpFrescos_vol2.pdf#page=79

Benzecry, C., and Collins, R. (2014). The high of cultural experience: toward a microsociology of cultural consumption. Sociol. Theory 32, 307–326. doi: 10.1177/0735275114558944

Berger, A., Schlager, T., Sprott, D. E., and Herrmann, A. (2018). Gamified interactions: Whether, when, and how games facilitate self–brand connections. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 46, 652–673. doi: 10.1007/s11747-017-0530-0

Bonn, M. A., Joseph Mathews, S. M., Dai, M., Hayes, S., and Cave, J. (2007). Heritage/cultural attraction atmospherics: creating the right environment for the heritage/cultural visitor. J. Travel Res. 45, 345–354. doi: 10.1177/0047287506295947

Bosone, M., Nocca, F., and Fusco, G. L. (2021). “The circular city implementation: cultural heritage and digital technology”, in Culture and Computing. Interactive Cultural Heritage and Arts. HCII 2021, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, ed. Rauterberg M. (Cham: Springer), 40–62.

Bowman, S. L. (2018). “Immersion and shared imagination in role-playing games,” in Role-playing game studies: Transmedia foundations, eds. J. P. Zagal, and S. Deterding (New York: Routledge), 379–394.

Carù, A., and Cova, B. (2013). “Consumer immersion in an experiential context,” in Consuming experience, eds. A. Carù, and B. Cova (London: Routledge), 48–61.

Cupchik, G. C. (2001). Theoretical integration essay: Aesthetics and emotion in entertainment media. Media Psychol. 3, 69–89. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0301_04

Dickinson, J. E., Filimonau, V., Hibbert, J. F., Cherrett, T., Davies, N., Norgate, S., et al. (2017). Tourism communities and social ties: the role of online and offline tourist social networks in building social capital and sustainable practice. J. Sustain. Tour. 25, 163–180. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1182538

Domínguez-Quintero, A. M., González-Rodríguez, M. R., and Paddison, B. (2020). The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 23, 248–260. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2018.1502261

Doyle, J., and Kelliher, F. (2023). Bringing the past to life: Co-creating tourism experiences in historic house tourist attractions. Tour. Managem. 94:104656. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104656

Fan, C. N., Wall, G., and Mitchell, C. J. (2008). Creative destruction and the water town of Luzhi, China. Tour. Managem. 29, 648–660. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.07.008

Fang, L. (2023). Research on the integrated development of China's cultural and creative industry and tourism industry. Modern Econ. Managem. Forum 4:44. doi: 10.32629/memf.v4i3.1370

Fu, X., Baker, C., Zhang, W., and Zhang, R. (2023). Theme park storytelling: deconstructing immersion in Chinese theme parks. J. Travel Res. 62, 893–906. doi: 10.1177/00472875221098933

García-Hernández, M., De la Calle-Vaquero, M., and Yubero, C. (2017). Cultural heritage and urban tourism: historic city centres under pressure. Sustainability 9:1346. doi: 10.3390/su9081346

Gardiner, S., Vada, S., Yang, E. C. L., Khoo, C., and Le, T. H. (2022). Recreating history: the evolving negotiation of staged authenticity in tourism experiences. Tour. Managem. 91:104515. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104515

Genc, V., and Gulertekin Genc, S. (2023). The effect of perceived authenticity in cultural heritage sites on tourist satisfaction: the moderating role of aesthetic experience. J. Hospitality Tour. Insights 6, 530–548. doi: 10.1108/JHTI-08-2021-0218

Gonzalez, A. M., and Bello, L. (2002). The construct “lifestyle” in market segmentation: The behaviour of tourist consumers. Eur. J. Mark. 36, 51–85. doi: 10.1108/03090560210412700

Gretzel, U., Fesenmaier, D. R., and O'Leary, J. T. (2005). “The transformation of consumer behaviour,” in Tourism business frontiers: Consumers, products and industry, eds. D. Buhalis, C. Costa, and F. Ford (London: Routledge), 9–18.

Guimarães, P. (2021). Retail change in a context of an overtourism city. The case of Lisbon. Int. J. Tour. Cities 7, 547–564. doi: 10.1108/IJTC-11-2020-0258

Hansen, A. H., and Mossberg, L. (2017). Tour guides' performance and tourists' immersion: Facilitating consumer immersion by performing a guide plus role. Scand. J. Hospit. Tour. 17, 259–278. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2016.1162347

Harviainen, J. T., Bienia, R., Brind, S., Hitchens, M., Kot, Y. I., MacCallum-Stewart, E., et al. (2018). “Live-action role-playing games,” in Role-Playing Game Studies, eds. S. Deterding, and J. Zagal (New York: Routledge), 87–106. doi: 10.4324/9781315637532-5

Jafari, A., Taheri, B., and Vom Lehn, D. (2013). Cultural consumption, interactive sociality, and the museum. J. Market. Managem.29, 1729–1752. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2013.811095

Jang, S., and Kim, J. (2022). Enhancing exercise visitors' behavioral engagement through gamified experiences: a spatial approach. Tour. Managem. 93:104576. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104576

Jelinčić, D. A. (2019). “Creating experiences in cultural tourism: from sightseeing to engaged emotional action,” in Creating and Managing Experiences in Cultural Tourism, eds. D. A. Jelinčić, and Y. Mansfeld (New Jersey: World Scientific), 3–16. doi: 10.1142/10809

Jelinčić, D. A., and Senkić, M. (2019). “The value of experience in culture and tourism: the power of emotions,” in A Research Agenda for Creative Tourism, eds. N. Duxbury and G. Richards (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 41–54. doi: 10.4337/9781788110723.00012

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: University Press.

Jolliffe, L., and Piboonrungroj, P. (2020). “The role of themes and stories in tourism experiences,” in The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Experience Management and Marketing (London: Routledge), 218–228.

Kawanaka, S., Matsuda, Y., Suwa, H., Fujimoto, M., Arakawa, Y., and Yasumoto, K. (2020). Gamified participatory sensing in tourism: an experimental study of the effects on tourist behavior and satisfaction. Smart Cities (Basel) 3, 736–757. doi: 10.3390/smartcities3030037

Kempiak, J., Hollywood, L., Bolan, P., and McMahon-Beattie, U. (2017). The heritage tourist: An understanding of the visitor experience at heritage attractions. Int. J. Heritage Stud.: IJHS 23, 375–392. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2016.1277776

Kim, J. H., and Youn, H. (2017). How to design and deliver stories about tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 56, 808–820. doi: 10.1177/0047287516666720

Kim, Y. N., Lee, Y., Suh, Y. K., and Kim, D. Y. (2021). The effects of gamification on tourist psychological outcomes: an application of letterboxing and external rewards to maze park. J. Travel Tour. Market. 38, 341–355. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2021.1921095

la Cuadra, M. T. D., Vila-Lopez, N., and Hernandez-Fernández, A. (2020). Could gamification improve visitors' engagement? Int. J. Tour. Cities 6, 317–334. doi: 10.1108/IJTC-07-2019-0100

Lak, A., Gheitasi, M., and Timothy, D. J. (2019). Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: cultural policies and strategic management. J. Tour. Cultural Change 18, 386–403. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2019.1668002

Leclercq, T., Poncin, I., and Hammedi, W. (2017). The engagement process during value co-creation: Gamification in new product-development platforms. Int. J. Electr. Commerce 21, 454–488. doi: 10.1080/10864415.2016.1355638

Lee, B. C. (2019). The effect of gamification on psychological and behavioral outcomes: Implications for cruise tourism destinations. Sustainability 11:3002. doi: 10.3390/su11113002

Lee, H. M., and Smith, S. L. J. (2015). A visitor experience scale: historic sites and museums. J. China Tourism Res. 11, 255–277. doi: 10.1080/19388160.2015.1083499

Lee, Y. J. (2022). Gamification and the festival experience: the case of Taiwan. Current Issues Tour. 26, 1311–1326. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2022.2053074

Liang, A. R. D. (2022). Consumers as co-creators in community-based tourism experience: Impacts on their motivation and satisfaction. Cogent Busin. Managem. 9:2034389. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2022.2034389

Liang, F., Pan, Y., Gu, M., Liu, Y., and Lei, L. (2022). Research on the paths and strategies of the integrated development of culture and tourism industry in urban historical blocks. Front. Public Health 10:1016801. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1016801

Lin, M., Gao, C., Lin, Y., and Wang, M. (2020). Place-branding of tourist destinations: The construction of the “third space” tourism experience and place imagination from Tang poetry. Tourism Tribune 35, 98–107. doi: 10.19765/j.cnki.1002-5006.2020.05.014-en

Lindberg, F., Hansen, A. H., and Eide, D. (2014). A multirelational approach for understanding consumer experiences within tourism. J. Hospit. Market. Managem. 23, 487–512. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2013.827609

Lombard, M., and Ditton, T. (1997). At the heart of it all: The concept of presence. J. Comp.-Mediat. Commun. 3:JCMC321. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00072.x

Luo, L., Chen, J., Cheng, Y., and Cai, K. (2024). Empirical analysis on influence of authenticity perception on tourist loyalty in historical blocks in China. Sustainability 16:2799. doi: 10.3390/su16072799

Mansilla, J. A., and Milano, C. (2022). Becoming centre: tourism placemaking and space production in two neighborhoods in Barcelona. Tour. Geograph. 24, 599–620. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2019.1571097

Manzano-León, A., Camacho-Lazarraga, P., Guerrero, M. A., Guerrero-Puerta, L., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Trigueros, R., et al. (2021). Between level up and game over: A systematic literature review of gamification in education. Sustainability 13, 1–14. doi: 10.3390/su13042247

Marcus, B., Weigelt, O., Hergert, J., Gurt, J., and Gelléri, P. (2017). The use of snowball sampling for multi source organizational research: some cause for concern. Pers. Psychol. 70, 635–673. doi: 10.1111/peps.12169

McCabe, S., and Foster, C. (2006). The role and function of narrative in tourist interaction. J. Tour. Cultural Change 4, 194–215. doi: 10.2167/jtcc071.0

McCain, G., and Ray, N. M. (2003). Legacy tourism: The search for personal meaning in heritage travel. Tour. Managem. 24, 713–717. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00048-7

Millar, S. (1989). Heritage management for heritage tourism. Tour. Managem. 10, 9–14. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(89)90030-7

Mochocki, M. (2021). Heritage sites and video games: Questions of authenticity and immersion. Games Culture. 16, 951–977. doi: 10.1177/15554120211005369

Moscardo, G. (2010). The shaping of tourist experience: the importance of stories and themes. Tour. Leisure Exp. 44, 43–58. doi: 10.21832/9781845411503-006

Moscardo, G. (2017). Stories as a tourist experience design tool. Design science in tourism. 97–124. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42773-7_7

Moscardo, G. (2020). Stories and design in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 83:102950. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102950

Moscardo, G. (2021). The story turn in tourism: forces and futures. J. Tour. Futures. 7, 168–173. doi: 10.1108/JTF-11-2019-0131

Ng, M. K., Zhai, B., Zhao, Y., and Li, J. (2016). Valuing xi'an: a Chinese capital city for 13 dynasties. DisP-The Plann. Rev. 52, 8–15. doi: 10.1080/02513625.2016.1235867

Nofal, E., Panagiotidou, G., Reffat, R. M., Hameeuw, H., Boschloos, V., and Vande Moere, A. (2020). Situated tangible gamification of heritage for supporting collaborative learning of young museum visitors. J. Comp. Cultural Heritage (JOCCH). 13, 1–24. doi: 10.1145/3350427

Paixão, W. B., and Cordeiro, I. J. (2021). Gamication practices in tourism: an analysis starting from the Werbach and Hunter 2012. Revista Brasileira De Pesquisa Em Turismo. 15:2067. doi: 10.7784/rbtur.v15i3.2067

Park, E., Choi, B. K., and Lee, T. J. (2019). The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Managem. 74, 99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.03.001

Poon, A. (1994). The ‘new tourism'revolution. Tour. Managem. 15, 91–92. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(94)90001-9

Prandi, C., Melis, A., Prandini, M., Delnevo, G., Monti, L., Mirri, S., et al. (2019). Gamifying cultural experiences across the urban environment. Multimedia Tools Appl. 78, 3341–3364. doi: 10.1007/s11042-018-6513-4

Prentice, R. (2001). Experiential cultural tourism: museums and the marketing of the new romanticism of evoked authenticity. Museum Managem. Curatorship. 19, 5–26. doi: 10.1080/09647770100201901

Rainoldi, M., Van den Winckel, A., Yu, J., and Neuhofer, B. (2022). “Video game experiential marketing in tourism: designing for experiences,” in Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2022: Proceedings of the ENTER 2022 eTourism Conference (Springer Nature Switzerland AG), 3–15. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-94751-4_1

Reagan, L., Nowlin, S. Y., Birdsall, S. B., Gabbay, J., Vorderstrasse, A., Johnson, C., et al. (2019). Integrative review of recruitment of research participants through Facebook. Nurs. Res. 68, 423–432. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000385

Richards, G., and Wilson, J. (2006). Developing creativity in tourist experiences: a solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tour. Managem. 27, 1209–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.06.002

Şchiopu, A. F., Pǎdurean, A. M., Ţalǎ, M. L., and Nica, A. M. (2016). The influence of new technologies on tourism consumption behavior of the millennials. Amfiteatru Economic J. 18, 829–846. Available at: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/169039

Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential Marketing: How to get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, Act, and Relate to Your Company and Brands. New York: Free Press.

Shang, G., and Yao, X. (2024). Stylization of history and heritage commodification: the linguistic landscape of refabricated historical streets in Chinese cities. Lang. Commun. 98, 60–73. doi: 10.1016/j.langcom.2024.06.001

Silver, D. A., and Clark, T. N. (2016). Scenescapes: How Qualities of Place Shape Social Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Skinner, H., Sarpong, D., and White, G. R. T. (2018). Meeting the needs of the millennials and generation Z: gamification in tourism through geocaching. J. Tour. Futures. 4, 93–104. doi: 10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0060

Smith, P. (2013). Turning tourists into performers: revaluing agency, action and space in sites of heritage tourism. Perf. Res. 18, 102–113. doi: 10.1080/13528165.2013.807174

Sofronov, B. (2018). Millennials: A new trend for the tourism industry. Econ. Series. 18, 109–122. doi: 10.26458/1838

Song, Y., Su, H., and Liu, Y. (2022). The applied study of reverse engineering: learning through games based on role-play. Int. Conf. Human-Comp. Interact. 1582, 120–127. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-06391-6_16

Spence, C. (2020). Senses of place: architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cognitive Res. 5:46. doi: 10.1186/s41235-020-00243-4

Stadler, D., and Bilgram, V. (2016). “Gamification: best practices in research and tourism,” in Open Tourism: Open Innovation, Crowdsourcing and co-Creation Challenging the Tourism Industrym, ed. Egger, R., Gula, I., Walcher, D. (Heidelberg: Springer Berlin). 363–370. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-54089-9_28

Straw, W. (2015). Some things a scene might be: Postface. Cultural Stud. 29, 476–485. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2014.937947

Tayhuadong, L., and Inkarojrit, V. (2024). Lighting design for Lanna Buddhist architecture: a case study of Suan Dok Temple, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Sustainability. 16:7494. doi: 10.3390/su16177494

Timothy, D. J., and Boyd, S. W. (2006). Heritage tourism in the 21st century: valued traditions and new perspectives. J. Heritage Tour. 1, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/17438730608668462

Tseng, C. P. (2022). Historical environmental theater as a catalyst for recalling citizens' collective memories: the performance revealing the old city as an example. Int. J. Architect. Spatial, Environm. Design. 17, 115–131. doi: 10.18848/2325-1662/CGP/v17i01/115-131

Turner, V., Abrahams, R., and Harris, A. (2017). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New York: Routledge, 232. doi: 10.4324/9781315134666

Wang, F., Li, J., Yu, F., He, H., and Zhen, F. (2018). Space, function, and vitality in historic areas: The tourismification process and spatial order of Shichahai in Beijing. Int. J. Tour. Res. 20, 335–344. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2185

Wang, F., Liu, Z., Shang, S., Qin, Y., and Wu, B. (2019). Vitality continuation or over-commercialization? Spatial structure characteristics of commercial services and population agglomeration in historic and cultural areas. Tourism Economics. 25, 1302–1326. doi: 10.1177/1354816619837129

Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tour. Res. 26, 349–370. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

Xi 'an Evening News (2024, February 18). 《2024龙年春节旅行报告》显示—-西安旅游订单同比增长64%. Available at: https://xafbapp.xiancn.com/newxawb/pc/html/202402/18/content_182155.html

Xu, F., Tian, F., Buhalis, D., Weber, J., and Zhang, H. (2016). Tourists as mobile gamers: gamification for tourism marketing. J. Travel Tour. Market. 33, 1124–1142. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2015.1093999

Xu, F., Weber, J., and Buhalis, D. (2013). “Gamification in tourism,” in Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014 (Cham; Heidelberg; New York, NY; Dordrecht; London: Springer), 525–537. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-03973-2_38

Xu, X., Le, T. H., Kwek, A., and Wang, Y. (2022). Exploring cultural tourist towns: Does authenticity matter? Tour. Managem. Perspectives. 41:100935. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100935

Keywords: consumer experience, gamification, immersive blocks, live action role play, urban design

Citation: Zheng Y, Zhang J and Li J (2024) Gamified experience design: a case study on China's immersive tourist blocks in historic cities. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1482203. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1482203

Received: 17 August 2024; Accepted: 12 November 2024;

Published: 04 December 2024.

Edited by:

Tan Vo-Thanh, Excelia Business School, FranceReviewed by:

Daria Plotkina, Université de Strasbourg, FranceCopyright © 2024 Zheng, Zhang and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinsha Li, bGlqaW5zaGFAY3VjLmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.