- 1School of Ethnology and Sociology, Yunnan University, Kunming, China

- 2School of Community Resources and Development, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, United States

- 3School of Tourism and Hospitality, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa

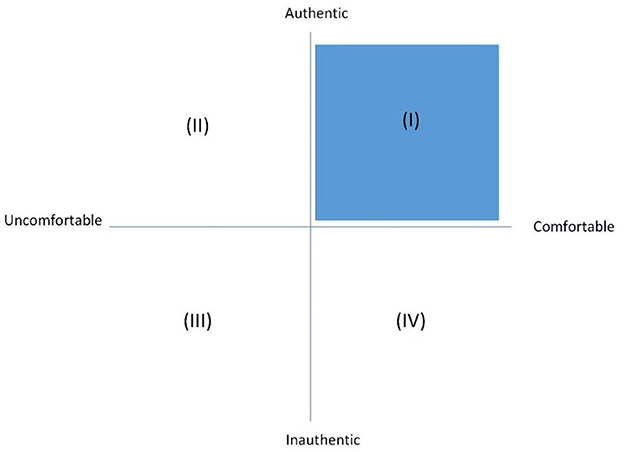

Authenticity is a popular research topic in tourism studies and is an important destination attribute that influences tourists and their decision-making. However, some studies have shown that tourists do not always seek authentic experiences and places. The purpose of this paper is to surmise why this might be the case. We employ Maslow's hierarchy of needs to articulate that pursuing authenticity represents a high-order need, and most tourists seek a balance between pursuing authenticity and lower-order needs, especially comfort. Based on level of comfort and perceived authenticity, four quadrants are presented, representing “desirable (comforting) authenticity,” “discomforting authenticity,” “discomforting-inauthenticity,” and “comforting-inauthenticity.” The paper argues that the optimal tourism product is the one associated with “desired authenticity.” Practical implications, limitations and future research suggestions are provided.

1 Introduction

Authenticity has long been a popular topic of academic debate, especial in tourism contexts (Boorstin, 1964; Chhabra, 2008, 2019; Chhabra et al., 2003; Cohen, 1979, 1988b,a; Cohen and Cohen, 2012; MacCannell, 1973; Timothy, 2021; Wang, 1999). Authenticity in various forms seems to play an important role in tourists' experiences and decision-making and is frequently associated with cultural heritage-based tourism (Asplet and Cooper, 2000; Chhabra et al., 2003; Timothy, 2021). For many tourists, authenticity manifests in activities such as consuming traditional foods, buying traditional handicrafts, spending a night in a local homestay, or otherwise immersing themselves in some perceived version of the authentic “Other”.

Yet, with the recent amassing of authenticity research, MacCannell's (1973) argument that tourists seek authenticity appears to be less certain. Several empirical studies have indicated that tourists might not desire as much authenticity as previously imagined by MacCannell and others. Wang's (2007) study shows that tourists in Lijiang, China, were satisfied with remodeled homestays that have abandoned certain elements of traditional Naxi architecture in order to accommodate the needs of tourists. Instead of being disappointed at the staged nature of some Naxi cultural elements, most tourists were satisfied with their experience. This phenomenon is also evident in Mura's (2015) Malaysia study where tourists were unwilling to replace comfort with less comfortable but more authentic environments and experiences. When facing the dregs of some traditional cultural spaces with their sometimes accompanying unhygienic environments, blatant poverty and physical dilapidation, many tourists demonstrate negative attitudes toward these situations even if these conditions are in fact part of a measurable “authentic” local environment (Zhou et al., 2018).

For many travelers, staying in a local homestay provides a higher plane of authenticity than overnighting in commercial lodging (Jamaludin et al., 2012). Thus, they may choose local homestays over standard hotels to satisfy their interests in more authentic local culture (Mura, 2015; Wang, 2007). This raises the question why tourists sometimes want authenticity, while sometimes they do not, especially in light of the fact that authenticity, especially in the Global South, is often equated with real-life conditions that non-locals might consider hard to handle: poverty, squalor, overcrowding, open sewage, non-flushing toilets, unkempt neighborhoods, and the like vs. the staged tourist spaces of the same places that tend to be tidier, better manicured, and less shabby (Timothy and Boyd, 2003; Zerva, 2015).

This conceptual paper focuses on the relationship between tourists' comfort and authenticity—a hotly contested subject within tourism studies (Brooks and Soulard, 2022; Canavan and McCamley, 2021; Chhabra, 2012). Based on Maslow's (1954) hierarchy of needs, a new model is proposed to help address this knowledge gap. Tourists are human beings with basic needs, and scholars have argued that authenticity is a tourist's high-order need and may be more easily satisfied once their lower-order needs are met (e.g., Hsu et al., 2021; Meng et al., 2021). This line of thinking about authenticity provides valuable insight for practitioners, policy makers and academic researchers. This paper explores the variability of tourists' desires for authenticity or lack thereof. It proposes a model based on Maslow's hierarchy of needs to examine how lower-order needs, including comfort, are juxtaposed with authenticity—here considered a higher-order need.

2 Current paradigms

2.1 Authenticity

Before delving into the relationship between tourists and authenticity, it is important to understand authenticity. Authenticity is a complicated concept (Golomb, 2012; Timothy, 2021), and disputes over its meaning have existed as long as people have tried to define it. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (2020), authentic means something original, true and accurate, as opposed to something copied, imaginary, or pretended. However, it is hard to define philosophically, with even the notion of “meaning” being misleading, as it suggests essentialism (Golomb, 2012). Authenticity has commonly been compared to sincerity or honesty, yet the concept is not an objective criterion that can be assessed by “the congruence between avowal and actual feeling” (Trilling, 1972, p. 2). Thus, authenticity must be something beyond sincerity and honesty.

Scholars have ideated authenticity and its manifestations. Søren Kierkegaard envisioned the possibility of recovering from a dispirited state and seeking a more authentic or genuine mode of living (Guignon, 2004). Although he did not use the word “authenticity”, Friedrich Nietzsche expressed that traditional beliefs are no longer credible, as the world undergoes constant change (Guignon, 2004). Based on phenomenological ontology, Martin Heidegger defined both authenticity and inauthenticity positively, where inauthenticity is simply “a modification of authenticity” with a positive ontological status (cited in Golomb, 2012, p. 94). Jean-Paul Satre was the first thinker to express negativity with regard to authenticity, calling for direct political action (Golomb, 2012). The underlying thematic connection between these philosophical treatises is a deeper level of self-authenticity (Golomb, 2012).

Authenticity creates paradoxes in various disciplines, including documentary film-making (Blumenberg, 1977; Bruzzi, 2006), art and performance (Michael, 2000; Peterson, 2013), consumerism (Liao and Ma, 2009) and of course, tourism (Boorstin, 1964; Chhabra, 2008, 2019; Cohen, 1988a,b, Cohen, 2010; Littrell et al., 1993; Littrell, 1990; MacCannell, 1973; Soukhathammavong and Park, 2019).

2.2 Authenticity in tourism

Scholars have provided many perspectives on authenticity within the context of tourism (e.g., Chhabra et al., 2003; Cohen, 1988b,a; Cohen and Cohen, 2012; MacCannell, 1973; Mura, 2015; Scott and Campos, 2024; Shuqair et al., 2019; Soukhathammavong and Park, 2019; Timothy and Boyd, 2003; Wang, 1999). These studies include, among other concerns, the background of authenticity, definitions and typologies of authenticity, the relationships between tourists and authenticity, empirical analyses of perceived authenticity and tourists' satisfaction, the process of authentication, and the innate characteristics of souvenirs that determine their authenticity.

According to Cohen (1988a), the primary problem in using the concept of authenticity in research lies in introducing it uncritically. He explains that authenticity may be seen from two perspectives. First is a scientific and verifiable perspective using ethically and scientifically defined criteria. The second perspective is that authenticity can be understood or studied from the subjective viewpoint of tourists, in accordance with their own conceptions of authenticity (Pearce and Butler, 1993, p. 47). In other words, authenticity may be objective (verifiable, original, and based on generally accepted criteria) or subjective, wherein individuals determine their own values and meanings of authenticity (Wang, 1999).

In relation to objective authenticity, Trilling (1972, p. 106) suggests that places and elements of material culture, can be verified to see if they “are what they appear to be or are claimed to be, and therefore worth the price that is asked for them—or, if this has already been paid, worth the admiration they are being given”. Proponents of this perspective (e.g., curators, historians, cultural geographers, and archaeologists) argue that there may be absolute and objective criteria against which authenticity can be measured (Timothy and Tahan, 2020). Thus, the situation might exist in tourism where places, objects and events are objectively inauthentic even if they are promoted as authentic and tourists perceive them to be authentic. For example, works of art, festivals, rituals, culinary traditions, customary dress, vernacular architecture, handicrafts, and so on are usually described as being authentic or inauthentic based on whether they are created or acted out by local people, according to custom or tradition, and utilize local products (Cohen, 1988a; Littrell et al., 1993; Timothy, 2021).

“Constructive authenticity” refers to the levels of authenticity projected onto objects, places and events by tourists or tourism producers (Wang, 1999). Thus, things may be “authentic” not because they are inherently and verifiably so, but because they are constructed as such by consumers and service providers. For instance, individuals who are less interested in authenticity might be more willing to accept a tourism product as authentic if it is intentionally branded and marketed as such, whereas for tourists who are more concerned with authenticity, those products may be considered “staged” and notably inauthentic (MacCannell, 1973). Cohen (1988a) also suggests that through time, objects that used to be inauthentic might become authentic, thus manifesting an “emergent authenticity” in which authenticity is fluid; it is negotiable between stakeholders and during different periods of time.

Wang (1999) introduced the concept of “existential authenticity”, which denotes the existential state of being that is activated by participants in tourism. In the liminal experience of tourism, tourists are away from their mundane lives and often express themselves more freely, not because they find places or objects to be authentic but because of their engagement in non-ordinary activities (Bigne et al., 2020; Light and Brown, 2020; Wang, 1999). Chhabra (2004, 2008) expanded Wang's thinking by developing theoretical streams of authenticity on a continuum from pure essentialism to pure constructivism.

2.3 Relationship between tourists and authenticity

The relationship between tourists and authenticity is highly contentious and multifarious. Since the 1960s, scholars have debated whether or not tourists desire authenticity (Boorstin, 1964; MacCannell, 1973) or the degrees to which authenticity is experienced and expressed (Cohen, 1988a; Nicolaides, 2014).

2.3.1 Tourists do not care about authenticity

Boorstin (1964) was one of the first people to discuss the relationship between tourists and authenticity. Although he did not use the word “authenticity”, he did suggest that tourists do not necessarily seek authentic products or experiences; they simply want to have a good time. Thus, they are usually content with what he calls “pseudo-events”. In his words, tourists expect more “strangeness and familiarity than the world naturally offers” (Boorstin, 1964, p. 79), an adventure of a lifetime without risks, where “exotic and familiar can be made to order” (Boorstin, 1964, p. 80). According to Boorstin, tourists are passive; they expect interesting things to happen, want to be served as valued guests, and many live in a tourist bubble far from reality of the locations they visit.

This touristic desire for entertainment has attracted entrepreneurs and destination residents to produce extravagant products for consumption, “increasing the gulf between the tourist and the real life at [the] destination” (Cohen, 1988b, p. 30). Usually objectively authentic destination products are viewed as opposite of Boorstin's (1964) staged pseudo-events, which are contrived for visitors to gratify their appetite for extraordinary places and times away from home (Timothy and Boyd, 2003). Part of the job of tour operators and travel agencies in some localities is to prevent tourists from encountering true localness, insulating their clients inside a tourist bubble, away from the sociocultural and economic realities of the destinations they visit. Boorstin (1964) and Lee and Wilkins (2017) contend that modern tourists expect efficiency, comfort and modernity, and in seeking these experiential features, they may be naïve or aware of destination conditions that are opposite of comfort, cleanliness, and modernity.

2.3.2 Tourists desire authenticity

MacCannell (1973) refutes Boorstin's assertion that tourists are only satisfied by pseudo-events or contrived places. MacCannell famously contends that tourists do not want superficial, contrived experiences. Instead, they strongly desire authenticity, however that manifests in their encounters. In this pro-authenticity discourse, it is often insinuated that authenticity no longer exists where travel consumers live; it exists only in the past or preserved in other parts of the world (Culler, 2007) where, as Tucker (1997) argues, landscapes are unpolluted and authentic, and residents are part of a living museum to be photographed and gazed upon. Thus, pursuing authenticity as “Otherness” constitutes a motivating factor in people's decisions to visit a specific destination (Bruner, 1994; Park et al., 2019; Rickly-Boyd, 2012; Ramkissoon and Uysal, 2018). For many tourists, in the idyllic place they seek, “…there is a very fine line between that which is considered worthy of tourist attention, and that which is perceived to be too touristy for ‘real' experience” (Tucker, 1997, p. 115).

According to MacCannell (1973), the motive behind a tour package is similar to that behind a pilgrimage; both are quests for authentic experiences. The idea of seeing the “real” Spain or Italy, seeing something “unspoiled”, or observing whether indigenous people really live the way they are often portrayed is a major touristic topos (Boag et al., 2020; Culler, 2007; Nuttall, 1997). In MacCannell's (1973) thinking, participating in guided tours was traditionally seen as a way to access areas that may ordinarily be closed to outsiders. In this way, tourists hope to encounter the “native” and become more immersed in the world of otherness. Later work, however, has shown that guided tours offer very little by way of native encounters and are geared more toward staged content for mass consumption (Chang and Oh, 2022; Mohamad et al., 2011; Timothy and Ioannides, 2002).

As an important factor of tourists' satisfaction with their visits (Moscardo and Pearce, 1986; Park et al., 2019), authenticity as sought by tourists may be conceptualized as object-related authenticity (Beverland and Farrelly, 2009; Littrell et al., 1993; Reisinger and Steiner, 2006; Yu and Littrell, 2003), visitor experience-related authenticity (Kim and Jamal, 2007; Szmigin et al., 2017) or a combination of the two (Rickly-Boyd, 2012; Ye et al., 2018). From the objective perspective, there is a factual basis for evaluating the authenticity of artifacts, events, cuisines, practices, clothing, and culture, generally supported by a calculable reality (Chhabra et al., 2003; Littrell et al., 1993; Reisinger and Steiner, 2006). Subjective authenticity refers to tourists constructing their own authenticities along the way (Canavan and McCamley, 2021; Kim and Jamal, 2007; Park et al., 2019; Wang, 1999). Tourists' subjective authenticity may have little to do with the verifiable authenticity of the places they visit or the sights they see (Wang, 1999). In essence, their perceptions of authenticity are what matter most to them and can be conditioned through various media, such as online travel vlogs, social media, and destinations' advertising campaigns (Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2020; Rahman et al., 2020).

Yet, even though tourists may create their own sense of destination authenticity, it is not they who create the consumable pseudo-events and contrived spaces of tourism. If, as MacCannell suggests, tourists are motivated by a desire for authenticity rather than pseudo-reality, why then does pseudo-reality prevail?

2.3.3 Different tourists want different degrees of authenticity

If tourists want authenticity while contrived places, events and objects continue to dominate many destination tourism capes, there is probably something amiss with the simplistic views of the tourist (Cohen, 1979; Lovell and Bull, 2017). To reconcile the opposed positions of Boorstin and MacCannell concerning the nature of contemporary tourism, Cohen (1979) proposed that there is no singular type of tourist. Rather different types of tourists exist and can be distinguished by their various characteristics and behaviors.

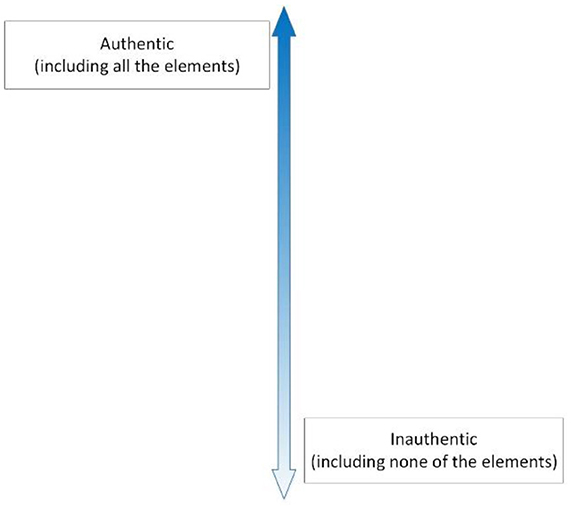

In most cases, authenticity is a socially-constructed concept that is not given but negotiated (Canavan and McCamley, 2021; Cohen, 1988a; Gardiner et al., 2022; Timothy, 2021). Cohen (1988a) outlines a continuum leading from complete fakery to complete authenticity (Figure 1). Based on five modes of touristic experience (diversionary, recreational, experiential, experimental, and existential) (Cohen, 1979), and the degree of tourist alienation from modernity and the depth of experience individuals seek during their travels, the five different types of tourists seek authenticity in varying degrees of intensity (Cohen, 1988a). “Existential tourists” tend to be willing to abandon modernity and comfort as they embrace the objectively authentic “Other”, sometimes even the extreme other. On the other end of the spectrum, “diversionary tourists” seek diversions and entertainment and are unconcerned with objective reality in their experience (Cohen, 1988a).

Figure 1. Tourists and their preferred authenticity (after Cohen, 1988a).

Of importance here is not merely establishing a typology of tourists. Instead, it presents a way of correlating the relationships between tourists and authenticity. This typology is based on two assumptions. First, tourists' diverse characteristics result in their varying expectations of, and experiences with, authenticity. Secondly, based on tourists' different characteristics, their desired level of authenticity will remain unchanged during their trip. These two assumptions raise the challenge of identifying specific tourist groups vis-à-vis differentiating diversionary tourists from experiential tourists or how to adjust the tourism product based on these differences, thus hindering the practical implications in applying these findings.

Recently, the strict binary views of tourists and authenticity seem to have abated, as observers now realize that not all tourists want pure authenticity, objective or subjective, all the time. Instead, some tourists (e.g., existential) would like to break the bonds of staged events and pseudo-places to seek the “real life” of the destination, while others find considerable levels of their own authenticity in the most obviously staged events and places (Brida et al., 2012; Chhabra et al., 2003). However, just as some empirical studies have shown, tourists want authenticity (at least what they perceive as authentic in lodging choices for example) by choosing traditional Naxi homestays in China (He and Chhabra, in press; Wang, 2007) or Parit Penghulu homestays in Malaysia (Mura, 2015). In these cases, they may be satisfied with a certain level of staging or they express contentment with obvious less-than-authentic conditions (Evrard and Leepreecha, 2009; Mura, 2015; Wang, 2007). Overall, it seems that most people are content with a mixed or blurred dose of authenticity and inauthenticity simultaneously. Wang (2007) attributes the phenomenon of tourists' satisfaction with staged Naxi homestays as evidence that they desire a homey type of authenticity, not necessarily a true native experience.

This line of thinking raises questions. For instance, how much authenticity (if it could be measured along a scale) do tourists want? And, most importantly, why do tourists sometimes want authenticity and sometimes they do not? Is it possible that the more authentic an experience or product is perceived to be, the easier it is to predict satisfaction or purchase behavior? Those questions are daunting and unanswered in the literature. This paper focuses on the fluidity of tourists' expectations of wanting authenticity and not wanting it. Considering the fact that tourists are human beings, and their pursuits of authenticity are part of their needs (other needs, for example, safety needs), we decided to embed the relationship between tourists and authenticity within Maslow's hierarchy of human needs.

3 New perspectives in understanding authenticity

3.1 The continuum of perceived authenticity

The awareness that authenticity is not absolute, but rather that it might exist on a continuum is not new. As noted previously, Cohen (1988a) argues that authenticity is negotiable and there exists a continuum leading from complete spuriousness/fakery to complete authenticity. Yet, in what kind of situation would tourists perceive a destination or tourism product to be completely fake or completely authentic? Cohen (1988a) contends that this can be attributed to the differences between individual tourists and their personal lives. However, is it possible that the differences are also related to the connection between authenticity and local (destination) elements of culture?

Swanson and Timothy (2012) argue for the value of some degree of objective authenticity in tourist souvenirs as a manifestation of local art and culture. The work by Littrell et al. (1993) found that many tourists value authenticity in the souvenir marketplace and identified characteristics, such as original patterns and colors, the use of local materials, being made by local artisans, an object having utilitarian value, and being designed based on local traditions, that ensured a higher degree of authenticity in their souvenir-buying experience (Timothy, 2005). These criteria corroborate the relationship between perceived local characteristics and values, and perceived authenticity. Similarly, from the perspective of destinations, Tasci and Knutson (2004) suggest static and dynamic manifestations of authenticity. Static components include the natural and cultural elements of the physical environment, whereas dynamic components include social (i.e., people and their characteristics, behaviors and relationships) and institutional factors (e.g., laws, policies, religions, ethics, rules, codes, and norms). According to their study, it is the unique features of these elements that determine and define the level of authenticity ascribed to a destination.

This paper provides a concept design to help forward an understanding of why tourists sometimes desire authenticity and sometimes they do not. As mentioned earlier, the evaluation of whether one is authentic to oneself (existential authenticity) is different from whether something or someplace visited is authentic.

Inspired by the work of Littrell et al. (1993) and the concept of “hard-core and soft-shell”, coined by Peterson (2013), the authenticity of objects, experiences and destinations in this paper means the perception of the organic integration of distinctive traits and characteristics associated with local symbols, materials, procedures of production, producers and other elements of local culture (Littrell et al., 1993; Soukhathammavong and Park, 2019). From this foundation, for our purposes, the degree of perceived authenticity is determined by the number and intensity of characteristics of local culture to be found in the destination. For example, a painting that depicts elements of local culture, uses local pigments and is painted by a local artist may be considered entirely authentic (Littrell, 1990; Littrell et al., 1993). However, a painting that only depicts certain cultural elements but is mass produced in a different locality still contains a modicum of authenticity (Asplet and Cooper, 2000), even if it is considered quite low and may be regarded as “better than none at all” (Smith, 2012, p. 244). In other words, as the number of the elements of authenticity (e.g., local architecture, traditional food, endemic or indigenous plants and animals, traditional clothes) increases, the degree of perceived authenticity is prone to increase and the more likely a tourist is to consider the product or experience authentic (see Figure 2).

3.2 Pursuing authenticity is a higher-level need

3.2.1 Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Abraham Maslow proposed a humanistic approach to psychology that differs from the negative implications of psycho-analysis and behaviorism for human potential (Zalenski and Raspa, 2006). He presented the “Hierarchy of Needs” in 1954, which has been used as a model for understanding human behavior and motivations in various disciplines, including business, adult learning, psychology, sociology, education and tourism (e.g., Benson and Dundis, 2003; Han, 2019).

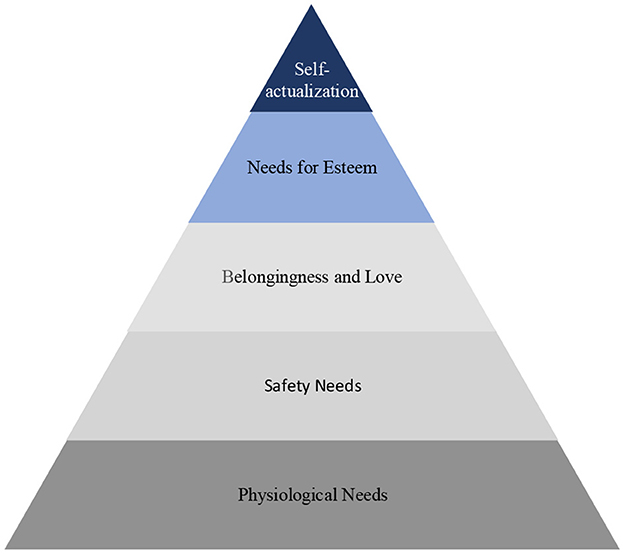

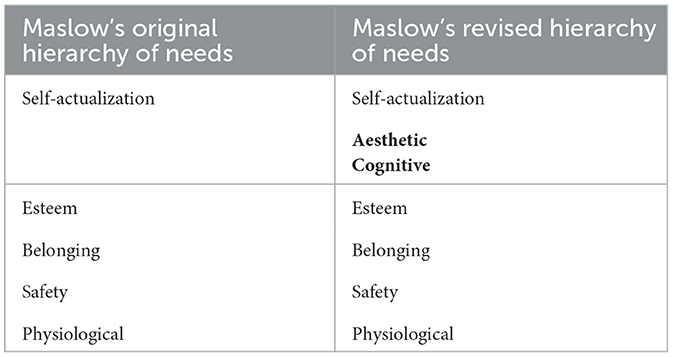

Maslow's hierarchical is divided into five levels (Figure 3). At the bottom of the pyramid are physiological needs, including food, water, air and other elements required for basic human survival. These are low-order needs, which everyone requires to live. The second level encompasses safety essentials, including security, stability, and the need for structure and order. The third level includes belongingness and love, suggesting that humans need social connections and emotional attachments to others. The fourth level includes the need for esteem, which embraces stable and firmly-based self-evaluation, self-respect, and the respect of others (Maslow, 1954). The fifth level and highest order is the need for self-actualization or the maximization of personal potential. Being in this level may lead to peak experiences or even transcendence (van Iwaarden and Nawijn, 2024) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of Maslow's original and revised levels of needs (source: Maslow, 1954, 1970).

Maslow's model was later expanded to include cognitive and aesthetic needs (Maslow, 1970; Zavei and Jusan, 2012), which are higher order needs above esteem but below self-actualization (Table 1). Cognitive needs focus on how we understand the world around us (Han, 2019; Pfeifer, 1998; Saeednia, 2009). Humans seek knowledge and have curious minds. We have a genuine interest in the world, in action, and in experimentation. We are attracted to the mysterious, to the unknown. Aesthetic needs reflect humans' desire for order, symmetry, design, harmony, and beauty (Maslow, 1970). If people cannot express a satisfactory aesthetic statement themselves, they will try to satisfy this need through the work of others, whether it be art, music, poetry, film, or other mediums (Brown and Cullen, 2006; Pfeifer, 1998; Wikström, 2002).

This hierarchy led to the development of a prepotency process (Kanfer, 1990), which suggests that individuals move upward through the hierarchy, pursuing the next high-order once their lower order needs have been satisfied. The hierarchy is not in a fixed temporal order, as one need does not have to be satisfied entirely before the next need emerges (Maslow, 1954). These needs are not mutually exclusive but are interdependent. Though this theory is widely accepted and has become one of the most popular conceptualization of motivation in various research fields (Han, 2019; Noltemeyer et al., 2012; Saeednia and Nor, 2013; Wahba and Bridwell, 1976), it has also been challenged for lacking empirical evidence to support its predictive power (Frame, 1996; Noltemeyer et al., 2021; Rouse, 2004; Wahba and Bridwell, 1976).

Just as Miner and Dachler (1973) indicate, Maslow's theory has proven to be useful in generating ideas and a valuable framework for explaining diverse research findings (Han, 2019; Lee et al., 2014; Noltemeyer et al., 2012; Wahba and Bridwell, 1976). In the context of understanding tourists' needs for authenticity, the framework provides a theoretical background for further analysis.

3.2.2 Pursing authenticity as a high-order need

Higher-order needs, when compared to lower-level needs, may produce peak experiences, happiness and greater life satisfaction (Maslow, 1954). These needs are closer to self-actualization, and lead to greater, stronger, and truer individual identity. They are more generalized, more intangible, and unlimited rather than more localized, tangible or limited.

As defined earlier, authenticity in this paper refers to the organic integration of traits associated with ethnic groups, local cuisine, landscapes and other elements of destination culture. Tourism products and destinations with higher perceived authenticity may be regarded as an asset to integrated tourism development for its ability to symbolize place and culture, enable tourists to experience a sense of connectedness to the destination (Sims, 2009), and provide distinctiveness or differentness in tourists' lives (Littrell et al., 1993). Authenticity can influence tourists' satisfaction with an attraction or destination and its heritage value, thereby influencing their intentions to revisit (Park et al., 2019; Timothy, 2021). As a central attribute (or perceived central attribute) of tourism, authenticity is important to tourists and tourism (Chhabra, 2005, 2019; Rickly and Vidon, 2018; Timothy, 2021; Timothy and Ron, 2013; Xie et al., 2012).

Experiencing authenticity may be a cognitive need. The process of pursuing authenticity is the process of seeking more elements of local culture in specific tourism products. This is connected to the process of “attaining new insights or information, something [tourists] did not know before” (Timothy and Boyd, 2003, p. 250) and they thereby gain a better understanding of local cultures. Just as (Kreuzbauer and Keller, 2017, p. 420) illustrate, “cultural products are critical tools of cultural learning, as they convey knowledge of both instrumental action and cultural convention”. Thus, from the perspective of authenticity, tourists might understand the tangible and intangible assets (knowledge) of local society via dance, songs, art, audio-visual presentations and other cultural manifestations (García-Almeida, 2019).

Pursuing authenticity may also be regarded as an aesthetic need. Tourists might try to experience a make-believe medieval historic environment linked to a fairytale (Lovell, 2019), appreciate the grandeur of the Taj Mahal (Edensor, 2008), or satisfy some need to be immersed in traditional culture by listening to local music (Szmigin et al., 2017), dressing in traditional costumes, enjoying local food (Prentice, 2001), buying souvenirs containing elements of local culture (He and Timothy, 2024a,b; Littrell, 1990) or staying in local homestays (Chitrakar et al., 2022; He and Chhabra, in press; Mura, 2015). When cognitive and aesthetic needs are gradually satisfied after more basic needs are met, tourists can better achieve self-realization through efforts to seek whatever authenticity means to them.

3.3 Desired authenticity model

Although pursuing authenticity is a high-order need, with only a few exceptions (e.g., Bruner, 1994; Cohen, 1995; Rickly-Boyd, 2012), there has been a tendency to overlook it in a tourism destination because people first have basic needs to satisfy (e.g., food, water and shelter). They need a clean, safe place free of waste and debris. They need benches for resting, paved sidewalks to keep from walking in the mud, and non-squatting toilets that flush (Bruner, 1994; Park, 2014; Timothy and Boyd, 2003). This reflects Rickly-Boyd's (2012) acknowledgment that tourists will accept staged authenticity as a protective substitute for more genuine alternatives. Many want to gain knowledge and appreciate the beauty of the destination, even being immersed in local culture to an extent, while simultaneously enjoying the comforts and conveniences of modern life (Boorstin, 1964; Cetin and Bilgihan, 2016). Thus, when confronted with lower-order needs and authenticity (a high-order need), tourists may try to find a balance between authenticity and their more basic needs, a balance between otherness and familiarity, comfort and reality (Boorstin, 1964; Lin et al., 2023; Tasci and Knutson, 2004; Wang, 2007).

To present the relationship better, here, lower-order needs are called “comforts”, and include physiological and safety requirements. One's level of comfort may exist on a continuum, with the least comfortable meaning that the lower-level needs remain completely unsatisfied, while high comfort means that lower-level needs are entirely satisfied. As described above, authenticity in this paper is also placed on a continuum that represents symbolic value, where authenticity means every tourism product or experience includes all elements that constitute perceived authenticity, while inauthentic means the situation lacks all elements of authenticity (see Figure 4).

In Figure 4, the crossover between level of comfort and level of authenticity creates four quadrants. The first quadrant (I) is “desired authenticity” (comforting authenticity). The second quadrant (II) is “discomforting authenticity”; the third quadrant (III) is “discomforting-inauthenticity”, and the fourth quadrant (IV) is “comforting-inauthenticity”.

3.3.1 Desired authenticity (comforting authenticity) (I)

Desired authenticity refers to the situation where tourists seek comfort and authenticity simultaneously. This is the optimal condition for visitor satisfaction in cultural contexts. What tourists appear to want is not necessarily pure authenticity but a “customized” authenticity (Wang, 2007), somewhere between authenticity and comfort. Tourists may only want authenticity (including the rawness or grunge associated with it) only for “relatively short periods of time, as guests do not want to replace their comfortable lives with less comfortable ‘authentic' experiences” (Mura, 2015, p. 230) (Bruner, 1994, p. 411) argues that tourists “yearn for a simpler life. But they are not alienated beings; they want modern…conveniences, and they would not be willing to give up their…[current] lives in exchange for the 1830s”. Thus, tourists welcome modern conveniences, even if these violate historical integrity or cultural accuracy (Barthel, 1990; Rickly-Boyd, 2012; Timothy and Boyd, 2003).

3.3.2 Discomforting authenticity (II)

Discomforting authenticity refers to “the phenomena and elements of a tourist destination's origin and past that are not accepted by tourists, although these elements and phenomena either currently exist or existed in the destination's past” (Zhou et al., 2018, p. 60). Thus, the reality of the past and present (authenticity) can negate the comfort levels of visitors, which Zhou et al refer to as negative authenticity. Although a place may be authentic in terms of what is “real” or “traditional”, this authenticity is not always accepted or valued by tourists—an assertion that refutes the assumption that authenticity is always a positive trait and always sought by tourists (Martin, 2010). For example, extremely disturbing facets of certain attractions (e.g., genocide memorials in Rwanda, killing fields localities in Cambodia, or Holocaust sites in Europe) may not be desirable or appropriate for all tourists (Cohen, 2010). Likewise, the destination reality of excess pollution, open sewage, and signs of social oppression, death or poverty might be abhorrent to some tourists (McKercher and du Cros, 2002; Timothy, 2021; Timothy and Boyd, 2003). Likewise, according to Zhou et al. (2018) and Timothy (2018), not all authentic folk culture is a good tourism fit. Tourism resources should be “selected, refined, processed, assembled and packaged according to the aesthetic taste and value judgement of both tourists and residents” (Zhou et al., 2018, p. 68).

3.3.3 Discomforting-inauthentic (III)

This is a theoretical possibility that might not currently exist. Here, the tourism product would be objectively or perceptually inauthentic and the experience uncomfortable. This means the degree to which this situation would satisfy low-order or high-order needs would be low. It is unlikely that many tourists would seek an experience that is both inauthentic and uncomfortable. It stands to reason that tourists would avoid such experiences, although certain contrived experiences might fit this mode and appeal to certain adrenaline-seekers. One such example is a fake US-Mexico border established at an amusement park deep in Mexico's interior. There, tourists can pay for a three-hour simulated illegal border crossing from Mexico into the US, trafficked by fake smugglers, chased by fake armed border guards, face intimidating guard dogs, climb over or under fences, and try to evade border patrol spotlights (Baskas, 2013)—an experience that is both fake and uncomfortable but apparently riveting.

3.3.4 Comforting-inauthenticity (IV)

Tourism products and experiences in this category tend to be more comfortable, which means that low-order needs are satisfied, while the degree of destination authenticity is low. Just as Boorstin (1964) describes, tourists choose to stay in familiar styles of hotels and resorts that insulate them from the “otherness” of the host environment, within an “environmental bubble”, which protects them from the harsh reality of destination conditions (Boorstin, 1964). Tourist bubbles and resorts around the world are common manifestations of this type of comfortable, albeit inauthentic, experience (Souza et al., 2020).

4 Conclusion

The main objective of this paper is to provide a conceptual tool for understanding why some tourists sometimes desire authenticity and sometimes they do not. Maslow's hierarchy of needs was employed to articulate that the pursuit of authenticity is a high-order need, meaning that it is less important than satisfying basic needs. Instead of rejecting authenticity entirely or, conversely, being stuck in a desperate quest for authenticity, most tourists seek a balance between comfort and authenticity. With different levels of comfort and authenticity, four quadrants represent desired authenticity (comforting authenticity), discomforting authenticity, discomforting-inauthenticity, and comforting-inauthenticity. The most pervasive tourism product and idealized experience most likely fits in the classification of desired authenticity.

Authenticity in this paper is viewed as the organic integration of the distinctive traits of an ethnic group, a place, a landscapes or other manifestation of culture. The number and intensity of characteristics of local culture may determine the degree of perceived authenticity in any given cultural situation. Thus, based on the manifestation of cultural characteristics, the degree of perceived authenticity varies along a continuum ranging from inauthentic to authentic.

Tourism products that emit a higher degree of perceived authenticity can symbolize place and culture and help tourists gain a sense of connection to the destination. The process of pursuing authenticity is the same as pursuing elements of local culture in specific tourism settings. This process reflects a desire to gain a greater understanding of local cultures and appreciate their intricacies, which today we see more clearly in the concepts of immersive tourism, experiential tourism, transformational tourism and the like. Thus, seeking authenticity is a cognitive or aesthetic need that is of a high-order nature in Maslow's hierarchy.

There are both desired (comforting) authenticity and discomforting authenticity in most tourism settings and experiences. Tourists may be able to balance comfort and authenticity and, based on their own preferences, they may consume various combinations of the two. In situations of discomforting authenticity, high levels of authenticity are sought at the expense of comfort. Consumers might be able to tolerate discomfort only for a short period of time or refuse it entirely, which might not bode well for local tourism development. For example, extremely disturbing attractions (e.g., certain war memorials with bones of the dead exposed) may not be appropriate for all visitors despite its high level of authenticity.

Several implications derive from this conceptualization. First, tourism products may be more popular through desired authenticity. Local providers can increase the popularity of their tourism offerings by increasing comfort levels while maintaining authenticity levels. The two concepts are not mutually exclusive. For example, if the comfort level remains unchanged, creatively ensuring more local and traditional elements are ensconced in architecture, souvenirs, crafts and food, or certifying souvenirs and crafts as hand-made or made by indigenous people can help the balance. Likewise, under present authenticity, service providers can try to maximize comfort, such as making food more palatable or making homestays more comfortable, increasing the functional value of the tourism product, perhaps at only a slight expense of traditionality or authenticity.

The second implication is for tourism destinations that desire to pursue discomforting authenticity. The best strategy to develop tourism in this context might be for service providers and agencies to concentrate on increasing comfort levels rather than focus on increasing authenticity. Authorities might try to present discomforting authenticity in a museum, an exhibition or a book, detailing the historical backgrounds of the discomforting authenticity phenomenon, instead of presenting it directly, or simply ignoring it.

The third implication is suggestions for creating a sustainable tourism community. If perceived authenticity is determined by elements of the local culture tourists encounter, then two big questions arise for the destination community: what are the local cultural characteristics and how should these be portrayed? Thus, with more people appreciating the importance of destination culture, language, music, traditional skills and livelihoods, architecture, festivals and celebrations, and other cultural elements might receive a higher priority in preservation efforts. Destination inhabitants, the most important stakeholders and purveyors of local culture, will not and should not be crowded out because of tourism development (Huibin et al., 2012; Stone and Nyaupane, 2020; Timothy, 1999).

The fourth implication is future research directions. Most previous authenticity studies assume that some tourists want authenticity, while other tourists do not. Most scholars conclude that personal differences result in people's pursuit of authenticity. This paper assumes that tourists sometimes want authenticity, sometimes they do not, and sometimes they want a mediated level of authenticity and comfort. Thus, rather than grouping tourists into types and claiming that certain types want authenticity while others do not, we argue that every tourist needs a certain level of authenticity and comfort, though in varying doses and different combinations. Likewise, the same person may desire differing levels of authenticity and comfort at different life stages or in different destinations. This additional perspective might provide new insights for future studies.

We acknowledge several limitations to this concept paper. The relationships between perceived authenticity and tourists' final decision-making (i.e., do higher levels of perceived authenticity lead to a higher probability of tourists' final travel choices?), the relationships between elements of local culture and perceived authenticity (i.e., does perceived authenticity increase as the number of local cultural features increase?), and the factors affecting perceived authenticity and tourists' perceptions of displaced authenticity are not addressed in this paper. This leaves opportunities for future conceptual and empirical research.

Despite these limitations, this paper provides a new way of thinking about authenticity and why tourists sometimes want it while sometimes they do not. We addressed this research question with Maslow's hierarchy of needs, and proposed a framework based on levels of authenticity and comfort. We propose that pursuing authenticity is a high-order need and that tourists probably want desired authenticity rather than discomforting authenticity.

Desired authenticity appears to oppose MacCannell's (1973) staged authenticity, as both concepts include certain elements of artificiality (Cohen, 1995). These two authenticities appear to function as two sides of the same coin, though one from the perspective of producers, the other from the perspective of consumers. This somehow helps explain the question we raised earlier: If as MacCannell suggests, tourists are motivated by a desire for authenticity, why then does the pseudo-authentic prevail? This paper provides one possible hint: tourists might not desire as much authenticity as scholars have assumed in the past. This perspective derives from the tourists themselves rather than from tourism producers, scholars or destination residents (Barthel, 1990; Buck, 1977; Zhou et al., 2018).

By suggesting that tourists might not always want pure authenticity, instead of portraying them as victims trapped in touristified spaces, this somehow relieves the pressure on the producers of staged touristic experiences. With the concept of authenticity being researched largely in a positive light, the denial of its fulfillment may be seen as a negative outcome (Cohen, 1995, p. 13). This raises the question again, “is authenticity intuitively a positive destination characteristic” (Cohen, 1995; Martin, 2010; Zhou et al., 2018)?

Author contributions

LH: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. DT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Asplet, M., and Cooper, M. (2000). Cultural designs in New Zealand souvenir clothing: the question of authenticity. Tour. Manag. 21, 307–312. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00061-8

Barthel, D. (1990). Nostalgia for America's village past: Staged symbolic communities. Int. J. Polit. Cult. Soc. 4, 79–93. doi: 10.1007/BF01384771

Baskas, H. (2013). Fake Illegal Border Crossing Is Real Mexican Them Park Attraction. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/business/travel/fake-illegal-border-crossing-real-mexican-theme-park-attraction-flna6c10476514 (accessed August 22, 2024).

Benson, S. G., and Dundis, S. (2003). Understanding and motivating health care employees: integrating Maslow's hierarchy of needs, training and technology. J. Nurs. Manag. 11, 315–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2003.00409.x

Beverland, M. B., and Farrelly, F. J. (2009). The quest for authenticity in consumption: consumers' purposive choice of authentic cues to shape experienced outcomes. J. Consum. Res. 36, 838–856. doi: 10.1086/615047

Bigne, E., Fuentes-Medina, M. L., and Morini-Marrero, S. (2020). Memorable tourist experiences versus ordinary tourist experiences analysed through user-generated content. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 45, 309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.08.019

Blumenberg, R. M. (1977). Documentary films and the problem of “truth”. J. Univ. Film Assoc. 29, 19–22.

Boag, C. J., Martin, R. J., and Bell, D. (2020). An ‘authentic' Aboriginal product: State marketing and the self-fashioning of Indigenous experiences to Chinese tourists. Aust. J. Anthropol. 31, 51–65. doi: 10.1111/taja.12345

Brida, J. G., Disegna, M., and Osti, L. (2012). Perceptions of authenticity of cultural events: a host–tourist analysis. Tour. Cult. Commun. 12, 85–96. doi: 10.3727/109830413X13575858951121

Brooks, C., and Soulard, J. (2022). Contested authentication: the impact of event cancellation on transformative experiences, existential authenticity at burning man. Ann. Tour. Res. 95:103412. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2022.103412

Brown, K., and Cullen, C. (2006). Maslow's hierarchy of needs used to measure motivation for religious behaviour. Mental Health Relig. Cult. 9, 99–108. doi: 10.1080/13694670500071695

Bruner, E. M. (1994). Abraham Lincoln as authentic reproduction: A Critique of postmodernism. Am. Anthropol. 96, 397–415. doi: 10.1525/aa.1994.96.2.02a00070

Buck, R. C. (1977). The ubiquitous tourist brochure explorations in its intended and unintended use. Ann. Tour. Res. 4, 195–207. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(77)90038-X

Canavan, B., and McCamley, C. (2021). Negotiating authenticity: three modernities. Ann. Tour. Res. 88, 103185. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103185

Cetin, G., and Bilgihan, A. (2016). Components of cultural tourists' experiences in destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 19, 137–154. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.994595

Chang, T. C., and Oh, F. (2022). Discovering the ‘heart' in heartland tourism. Geografiska Ann. 104, 75–92. doi: 10.1080/04353684.2021.1929383

Chhabra, D. (2004). Redefining a festival visitor: a case study of vendors attending Scottish Highland Games in the United States. Event Manag. 9, 91–94. doi: 10.3727/1525995042781057

Chhabra, D. (2005). Defining authenticity and its determinants: toward an authenticity flow model. J. Travel Res. 44, 64–73. doi: 10.1177/0047287505276592

Chhabra, D. (2008). Positioning museums on an authenticity continuum. Ann. Tour. Res. 35, 427–447. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.12.001

Chhabra, D. (2012). A present-centered dissonant heritage management model. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 1701–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.03.001

Chhabra, D. (2019). Authenticity and the authentication of heritage: dialogical perceptiveness. J. Herit. Tour. 14, 389–395. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2019.1644340

Chhabra, D., Healy, R., and Sills, E. (2003). Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 30, 702–719. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00044-6

Chitrakar, K., Carr, N., and Albrecht, J. N. (2022). “Expanding the boundaries of local cuisine: the context of Himalayan community-based homestays,” in Tourism and Development in the Himalaya: Social, Environmental, and Economic Forces, eds. G. P. Nyaupane, and D. J. Timothy (London: Routledge), 208–224.

Cohen, E. (1979). Rethinking the sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 6, 18–35. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(79)90092-6

Cohen, E. (1988a). Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 15, 371–386. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X

Cohen, E. (1988b). Traditions in the qualitative sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 15, 29–46. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(88)90069-2

Cohen, E. (1995). “Contemporary tourism-trends and challenges: sustainable authenticity or contrived post-modernity?” in Change in Tourism: People, Places, Processes, eds. R. Butler and D. Pearce (London: Routledge), 12–29.

Cohen, E., and Cohen, S. A. (2012). Authentication: hot and cool. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 1295–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.03.004

Cohen, E. H. (2010). Educational dark tourism at an in populo site. Ann. Tour. Res. 38, 193–209. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.08.003

Edensor, T. (2008). Tourists at the Taj: Performance and Meaning at a Symbolic Site. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Evrard, O., and Leepreecha, P. (2009). Monks, monarchs and mountain folks. Crit. Anthropol. 29, 300–323. doi: 10.1177/0308275X09104657

Frame, D. (1996). Maslow's hierarchy of needs revisited. Interchange 27, 13–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01807482

García-Almeida, D. J. (2019). Knowledge transfer processes in the authenticity of the intangible cultural heritage in tourism destination competitiveness. J. Herit. Tour. 14, 409–421. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2018.1541179

Gardiner, S., Vada, S., Yang, E. C. L., Khoo, C., and Le, T. H. (2022). Recreating history: the evolving negotiation of staged authenticity in tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 91:104515. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104515

Golomb, J. (2012). In Search of Authenticity: Existentialism from Kierkegaard to Camus. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Guignon, C. B. (2004). The Existentialists: Critical Essays on Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Sartre. Lanham; Boulder; New York, NY; Toronto; Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Han, J. (2019). Vacationers in the countryside: traveling for tranquility? Tour. Manag. 70, 299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.001

He, L., and Chhabra, D. (in press). “Traditional-style houses: more authenticity or comfort?,” in Sustainable Marketing of Transformative Heritage Tourism, ed. D. Chhabra (London: Routledge).

He, L., and Timothy, D. J. (2024a). Tourists' perceptions of ‘cultural and creative souvenir' products and their relationship with place. J. Tour. Cult. Change 22, 143–163. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2023.2293287

He, L., and Timothy, D. J. (2024b). Understanding souvenirs from a place-product perspective: Territorialization, deterritorialization and reterritorialization. Tour. Rev. Int. 28, 25–48. doi: 10.3727/154427223X16819417821868

Hsu, F. C., Agyeiwaah, E., Lynn, I., and Chen, L. (2021). Examining food festival attendees' existential authenticity and experiential value on affective factors and loyalty: an application of stimulus-organism-response paradigm. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 48, 264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.06.014

Huibin, X., Marzuki, A., and Razak, A. A. (2012). Protective development of cultural heritage tourism: the case of Lijiang, China. Theoret. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 7, 39–54. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24873309

Jamaludin, M., Othman, N., and Awang, A. R. (2012). Community based homestay programme: a personal experience. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 42, 451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.210

Jiménez-Barreto, J., Rubio, N., and Campo, S. (2020). Destination brand authenticity: what an experiential simulacrum! A multigroup analysis of its antecedents and outcomes through official online platforms. Tour. Manag. 77:104022. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104022

Kanfer, R. (1990). “Motivation theory and industrial and organizational psychology,” in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 1. Theory in Industrial and Organizational Psychology, eds. M. D. Dunnette and L. Hough (Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press), 75–170.

Kim, H., and Jamal, T. (2007). Touristic quest for existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 34, 181–201. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.07.009

Kreuzbauer, R., and Keller, J. (2017). The authenticity of cultural products: a psychological perspective. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 417–421. doi: 10.1177/0963721417702104

Lee, D.-J., Kruger, S., Whang, M.-J., Uysal, M., and Sirgy, M. J. (2014). Validating a customer well-being index related to natural wildlife tourism. Tour. Manag. 45, 171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.04.002

Lee, H. J., and Wilkins, H. (2017). Mass tourists and destination interaction avoidance. J. Vacat. Market. 23, 3–19. doi: 10.1177/1356766715617218

Liao, S., and Ma, Y. (2009). Conceptualizing consumer need for product authenticity. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 4, 89–114.

Light, D., and Brown, L. (2020). Dwelling-mobility: a theory of the existential pull between home and away. Ann. Tour. Res. 81:102880. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102880

Lin, J., Cui, Q., and Xu, H. (2023). Beyond novelty–familiarity dualism: the food consumption spectrum of Chinese outbound tourists. J. China Tour. Res. 19, 155–175. doi: 10.1080/19388160.2022.2049942

Littrell, M. A. (1990). Symbolic significance of textile crafts for tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 17, 228–245. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(90)90085-6

Littrell, M. A., Anderson, L. F., and Brown, P. J. (1993). What makes a craft souvenir authentic? Ann. Tour. Res. 20, 197–215. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(93)90118-M

Lovell, J. (2019). Fairytale authenticity: historic city tourism, Harry Potter, medievalism and the magical gaze. J. Herit. Tour. 14, 448–465. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2019.1588282

Lovell, J., and Bull, C. (2017). Authentic and Inauthentic Places in Tourism: From Heritage Sites to Theme Parks. London: Routledge.

MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity : arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 79, 589–603. doi: 10.1086/225585

Martin, K. (2010). Living pasts: contested tourism authenticities. Ann. Tour. Res. 37, 537–554. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2009.11.005

McKercher, B., and du Cros, H. (2002). Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management. New York, NY; London: Routledge.

Meng, Z. M., Cai, L. A., Day, J., Tang, C. H. H., Lu, Y. T., and Zhang, H. (2021). “Authenticity and nostalgia–subjective well-being of Chinese rural-urban migrants,” in Authenticity and Authentication of Heritage, ed. D. Chhabra (London: Routledge), 118–136.

Michael, H. (2000). Country music as impression management: a meditation on fabricating authenticity. Poetics 28, 185–205. doi: 10.1016/S0304-422X(00)00021-8

Miner, J. B., and Dachler, H. P. (1973). Personnel attitudes and motivation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 24, 379–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.24.020173.002115

Mohamad, N. H., Razzaq, A. R. A., Khalifah, Z., and Hamzah, A. (2011). Staged authenticity: lessons from Saung Anklung Udjo, Bandung, Indonesia. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 24, 43–51.

Moscardo, G. M., and Pearce, P. L. (1986). Historic theme parks: an Australian experience in authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 13, 467–479. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(86)90031-9

Mura, P. (2015). Perceptions of authenticity in a Malaysian homestay - a narrative analysis. Tour. Manag. 51, 225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.05.023

Nicolaides, A. (2014). Authenticity and the tourist's search for being. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 3, 1–11.

Noltemeyer, A., Bush, K., Patton, J., and Bergen, D. (2012). The relationship among deficiency needs and growth needs: an empirical investigation of Maslow's theory. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 34, 1862–1867. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.05.021

Noltemeyer, A., James, A. G., Bush, K., Bergen, D., Barrios, V., and Patton, J. (2021). The relationship between deficiency needs and growth needs: the continuing investigation of Maslow's theory. Child Youth Serv. 42, 24–42. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2020.1818558

Nuttall, M. (1997). “Packaging the wild: Tourism development in Alaska,” in Tourists and Tourism: Identifying with People and Places, eds. S. Abram, J. Waldren, and D. MacLeod (Oxford: Routledge), 223–238.

Oxford English Dictionary (2020). Authentic. Available at: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/authentic?q=authentic (accessed April 15, 2020).

Park, C. H. (2014). Nongjiale tourism and contested space in rural China. Mod. China 40, 519–548. doi: 10.1177/0097700414534160

Park, E., Choi, B.-K., and Lee, T. J. (2019). The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 74, 99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.03.001

Pearce, D. G., and Butler, R. W. (1993). Tourism Research: Critiques and Challenges. London: Taylor and Francis.

Peterson, R. A. (2013). Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pfeifer, A. A. (1998). Abraham Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs: A Christian Perspective. The 22'integration Faith and Learning Seminar. Seminar Schloss Bogenhofen, Austria. Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=ef5929eb75040cd828bc072a8655ad8393274d6c

Prentice, R. (2001). Experiential cultural tourism: museums and the marketing of the new romanticism of evoked authenticity. Museum Manag. Curator. 19, 5–26. doi: 10.1080/09647770100201901

Rahman, A., Ahmed, T., Sharmin, N., and Akhter, M. (2020). Online destination image development: the role of authenticity, source credibility, and Involvement. J. Tour. Q. 3, 1–20. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43178176.pdf

Ramkissoon, H., and Uysal, M. S. (2018). “Authenticity as a value co-creator of tourism experiences,” in Creating Experience Value in Tourism, 2nd Edn, eds. N. K. Prebensen, J. S. Chen, and M. S Uysal (Wallingford: CABI), 98–109.

Reisinger, Y., and Steiner, C. J. (2006). Reconceptualizing object authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 33, 65–86. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2005.04.003

Rickly, J. M., and Vidon, E, . (eds.) (2018). Authenticity and Tourism: Materialities, Perceptions, Experiences. Bingley: Emerald.

Rickly-Boyd, J. M. (2012). ‘Through the magic of authentic reproduction': tourists' perceptions of authenticity in a pioneer village. J. Herit. Tour. 7, 127–144. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2011.636448

Rouse, K. A. G. (2004). Beyond Maslow's hierarchy of needs what do people strive for? Perform. Improv. 43, 27–31. doi: 10.1002/pfi.4140431008

Saeednia, Y. (2009). The need to know and to understand in Maslow's basic needs hierarchy. US China Educ. Rev. 6, 52–57.

Saeednia, Y., and Nor, M. M. D. (2013). Measuring hierarchy of basic needs among adults. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 82, 417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.285

Scott, N., and Campos, A. C. (2024). A critique of authenticity: how psychology can help. Tour. Critiq. 5, 44–64. doi: 10.1108/TRC-10-2023-0027

Shuqair, S., Pinto, D. C., and Mattila, A. S. (2019). Benefits of authenticity: post-failure loyalty in the sharing economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 78:102741. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.06.008

Sims, R. (2009). Food, place and authenticity: local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 17, 321–336. doi: 10.1080/09669580802359293

Smith, V. L. (2012). Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Soukhathammavong, B., and Park, E. (2019). The authentic souvenir: what does it mean to souvenir suppliers in the heritage destination? Tour. Manag. 72, 105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.11.015

Souza, L. H., Kastenholz, E., Barbosa, M. D. L. A., and Carvalho, M. S. E. S. C. (2020). Tourist experience, perceived authenticity, place attachment and loyalty when staying in a peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Tour. Cities 6, 27–52. doi: 10.1108/IJTC-03-2019-0042

Stone, L. S., and Nyaupane, G. P. (2020). Local residents' pride, tourists' playground: the misrepresentation and exclusion of local residents in tourism. Curr. Iss. Tour. 23, 1426–1442. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2019.1615870

Swanson, K. K., and Timothy, D. J. (2012). Souvenirs: icons of meaning, commercialization and commoditization. Tour. Manag. 33, 489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.10.007

Szmigin, I., Bengry-Howell, A., Morey, Y., Griffin, C., and Riley, S. (2017). Socio-spatial authenticity at co-created music festivals. Ann. Tour. Res. 63, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.12.007

Tasci, A. D. A., and Knutson, B. J. (2004). An argument for providing authenticity and familiarity in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Leis. Market. 11, 85–109. doi: 10.1300/J150v11n01_06

Timothy, D. J. (1999). Participatory planning: a view of tourism in Indonesia. Ann. Tour. Res. 26, 371–391. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00104-2

Timothy, D. J. (2018). Making sense of heritage tourism: research trends in a maturing field of study. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 25, 177–180. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.018

Timothy, D. J. (2021). Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction, 2nd. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Timothy, D. J., and Ioannides, D. (2002). “Tour operator hegemony: dependency, oligopoly, and sustainability in insular destinations,” in Island Tourism and Sustainable Development: Caribbean, Pacific, and Mediterranean Experiences, eds. Y. Apostolopoulos, and D. J. Gayle (Westport, CT: Praeger), 181–198.

Timothy, D. J., and Ron, A. S. (2013). Understanding heritage cuisines and tourism: identity, image, authenticity and change. J. Herit. Tour. 8, 99–104. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2013.767818

Timothy, D. J., and Tahan, L. G. (2020). “Archaeology and tourism: consuming, managing and protecting the human past,” in Archaeology and Tourism: Touring the Past, eds. D. J. Timothy and L. G. Tahan (Bristol: Channel View Publications), 1–25.

Tucker, H. (1997). “The ideal village: interactions through tourism in central Anatolia,” in Tourists and Tourism: Identifying With People and Places, eds. S. Abram, J. Waldren, and D. V. L. Mcleod (London: Berg), 107–128.

van Iwaarden, M., and Nawijn, J. (2024). Eudaimonic benefits of tourism: the pilgrimageexperience. Tour. Recreat. Res. 49, 37–47. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2021.1986777

Wahba, M. A., and Bridwell, L. G. (1976). Maslow reconsidered: a review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 15, 212–240. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6

Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 26, 349–370. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

Wang, Y. (2007). Customized authenticity begins at home. Ann. Tour. Res. 34, 789–804. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.03.008

Wikström, B.-M. (2002). Nurses' strategies when providing for patients' aesthetic needs: personal experiences of aesthetic means of expression. Clin. Nurs. Res. 11, 22–33. doi: 10.1177/105477380201100103

Xie, P. F., Wu, T.-C., and Hsieh, H.-W. (2012). Tourists' perception of authenticity in indigenous souvenirs in Taiwan. J. Travel Tour. Market. 29, 485–500. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2012.691400

Ye, S., Xiao, H., and Zhou, L. (2018). Commodification and perceived authenticity in commercial homes. Ann. Tour. Res. 71, 39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.05.003

Yu, H., and Littrell, M. A. (2003). Product and process orientations to tourism shopping. J. Travel Res. 42, 140–150. doi: 10.1177/0047287503257493

Zalenski, R. J., and Raspa, R. (2006). Maslow's hierarchy of needs: a framework for achieving human potential in hospice. J. Palliat. Med. 9, 1120–1127. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1120

Zavei, S. J. A. P., and Jusan, M. M. (2012). Exploring housing attributes selection based on Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 42, 311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.195

Zerva, K. (2015). Visiting authenticity on Los Angeles gang tours: tourists backstage. Tour. Manag. 46, 514–527. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.004

Keywords: perceived authenticity, desired authenticity, Maslow's hierarchy of needs, higher-order needs, lower-order needs

Citation: He L and Timothy DJ (2024) Authentic or comfortable? What tourists want in the destination. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1437014. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1437014

Received: 23 May 2024; Accepted: 13 August 2024;

Published: 02 September 2024.

Edited by:

Bailey Ashton Adie, University of Oulu, FinlandReviewed by:

Alexander Trupp, Sunway University, MalaysiaAna Cláudia Campos, University of Algarve, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 He and Timothy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linsi He, bGluc2loZUBhc3UuZWR1

Linsi He

Linsi He Dallen J. Timothy

Dallen J. Timothy