- Department of Hospitality and Tourism, Auckland University of Technology - Te Wānanga Aronui o Tāmaki Makau Rau, Auckland, New Zealand

The sea, sand, and sun allure of the Cook Islands has seen tourism become the most significant driver of the country's economic development. However, the increasing reliance on the tourism sector since the 1980's has created a mono-economy at the expense of diversification and alternative economic models. The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the risks and consequences associated with an over- reliance on international tourism as the lockdown measures and international travel restrictions caused the sudden shutdown of international tourism, resulting in serious negative economic consequences for tourism-dependent communities. However, the pandemic also offered an opportunity for small island societies to reflect on pre-existing challenges associated with the tourism industry. Through qualitative semi-structured interviews with Indigenous Cook Islanders in Rarotonga, this study aimed to develop a deeper understanding of how the lived experiences of participants responding to the sudden collapse of tourism may have influenced how Indigenous Cook Islands peoples perceive the role of tourism in supporting the wellbeing of their small island nation. The presented study is the result of a collaborative research partnership between an Indigenous Pacific scholar and non-Indigenous European scholar. While the research adopted a western methodology, the relationships developed between the researchers and participants were guided by the cultural values of reciprocity and respect, which are key principles underpinning Indigenous research in the Pacific. The findings revealed that participants adapted to the adverse impacts of COVID-19 through the revitalization of their traditional socio-economies, the resurgence of customary practices, a strengthened connection to nature, and a renewed sense of community spirit and pride in cultural identity—all of which were perceived to positively impact their spiritual, social, cultural, environmental, physical, and mental wellbeing. By demonstrating the positive adaptive responses of participants, this article aims to emphasize the non-economic dimensions of wellbeing that are critical to supporting the cultural values, social priorities, and the Indigenous ways of life that preceded the development of tourism. These findings can be used to inform and guide international development policy makers and tourism stakeholders who seek to reduce the adverse impacts of tourism on the wellbeing of Indigenous communities in the Pacific.

Introduction

Within international development discourses, the barriers to economic growth in small island developing states (SIDS) have been extensively discussed and summarized into unique characteristics. These unique traits include their small size and populations, geographical remoteness from international markets, high transportation costs, narrow resource base and undiversified economies, large trade deficits, and extreme exposure to severe weather events linked to the adverse impacts of climate change (Pratt, 2015; Scandurra et al., 2018; Zhang and Managi, 2020). While many developing countries and small nations may face similar challenges, it is the interconnectivity and compounding factor of all these characteristics that makes SIDS disproportionally vulnerable to exogenous shocks, which threatens the reversal of socioeconomic development achieved over the past decades (Thompson, 2022). For instance, SIDS' small size and remote locations limits their connectivity to global markets, increases the costs of trade and transportation, and hinders their access to resources, services and other developmental opportunities (Briguglio, 2018). This in turn creates challenges for domestic industries to take advantage of economies of scale, resulting in a reliance on export markets, increasing dependence on imported products, vast trade deficits, and limited economic diversification (Bell et al., 2021; Briguglio, 2018; Fernandes and Pinho, 2017).

Hence, while agriculture, fisheries, and forestry have traditionally provided the main source of livelihood for many small island societies (Connell et al., 2020), the industrialization of these sectors as an export-oriented strategy presented various challenges for SIDS due to their structural and geophysical constraints. Furthermore, the industrialization of subsistence-based sectors for global trade led to significant environmental degradation impacts. For example, research has demonstrated how widespread clearance of land to make way for squash plantations in Tonga led to increased rates of soil erosion and loss of biodiversity in many small island geographies (Burlingame et al., 2019). The introduction of monoculture for the citrus industry in the Cook Islands, which was once a significant part of the economy, altered traditional land use patterns and made crops vulnerable to pests and diseases, leading to increased uses of pesticides and potential environmental contamination (Rongo and van Woesik, 2011). Unlike manufacturing or large-scale agriculture, tourism was seen as a development strategy that could capitalize on the islands' natural beauty without depleting finite resources (Naidoo and Sharpley, 2016).

Prior to the global disruption of COVID-19, the majority of all 58 SIDS recognized by the United Nations (UN) depended on tourism as the primary tool for economic development and social progress (Bak and Szczecinska, 2020). The effectiveness of tourism in promoting development has been supported by empirical studies such as Gunter et al.'s (2018) research in the Caribbean, Seetanah et al.'s (2019) global analysis of tourism in SIDS, and Cheer et al.'s (2018) research on the economic contributions of tourism in Pacific Island Countries (PICs). Similar economic studies found that tourism has a positive effect on the quality of life in island societies by providing the necessary financial means to develop medical and educational projects through the benefits of corporate social responsibility offered by hotels (Harrison and Prasad, 2013; Ridderstaat et al., 2016). While there is extensive evidence that supports the notion of tourism as an effective driver for the economic growth of SIDS, this body of knowledge tends to overlook the non-economic impacts of tourism. Furthermore, there is limited research that investigates the effectiveness of tourism in supporting the subjective wellbeing of Indigenous communities in small island nations in the Pacific (Scheyvens et al., 2023).

The sudden collapse of the tourism industry due to COVID-19 lockdowns and international travel restrictions provided a unique opportunity for small island communities to reflect on the impacts of tourism on their subjective wellbeing. Recent studies have begun to explore this phenomenon, with notable contributions from Mika et al. (2024), Movono and Scheyvens (2022), and Movono et al. (2022), who framed the COVID-19 disruption as an opportunity to reassess tourism's role in Indigenous communities. Building upon this emerging body of work, our study seeks to deepen and extend these insights by focusing specifically on the lived experiences of Indigenous Cook Islanders. While previous research has laid important groundwork, our study aims to provide a more nuanced, culturally-specific understanding of how the COVID-19 crisis influenced Indigenous Cook Islanders perceptions of tourism's role in supporting their subjective wellbeing. The following section reviews the literature on Indigenous tourism to contextualize our study's contribution to this evolving field of knowledge.

Indigenous tourism in small island developing states

Indigenous tourism as a research area has gained academic and scholarly attention since the 1950's (Carr et al., 2016). Within this burgeoning field, a wide range of topics continue to be explored, such as the benefits and challenges of Indigenous tourism businesses, Aboriginal engagement in tourism, marketing and representation of Indigenous people, visitor demand studies, Indigenous intellectual property rights, industry perspectives on Indigenous tourism, and the impacts of tourism on Indigenous people (Hinch and Butler, 1996; Buultjens and Fuller, 2007; Sharpley, 2014; Smith and Brent, 2001; Zeppel, 1998). Given this comprehensive range of studies, definitions of Indigenous tourism vary depending on the focus of the analyst (Higgins-Desbiolles and Bigby, 2022), the researchers' perspectives, and the objectives guiding the study. One definition that has gained popularity within academic literature, as evidenced in its frequent citations, defines Indigenous tourism as “tourism activities in which Indigenous people are directly involved either through control and/or by having their culture serve as the essence of the attraction” (Butler and Hinch, 2007, p. 4). Other definitions focus on the active involvement of Indigenous people within the tourism sector by emphasizing various forms of participation as employers, employees, investors, joint venture partners, and/or providers of Indigenous cultural tourism products (Peters and Higgins-Desbiolles, 2012). However, as Nielsen and Wilson (2012) point out, the role of Indigenous people themselves within this body of knowledge has received limited attention. Therefore, even though Indigenous tourism has been a topic of academic interest since the mid-twentieth century, both research and the Indigenous tourism sector are still predominately driven by the needs, curiosities, and priorities of non-Indigenous people. The former is particularly evident when exploring the roots of Indigenous tourism, which dates back to the colonial era.

During the colonial era, colonists would be seen as the tourists attracted to colonized places and colonized peoples (Higgins-Desbiolles and Bigby, 2022). In 1907, for example, colonial expositions in France known as “human zoos” entertained visitors by displaying reconstructed Indigenous villages populated by colonialists and Indigenous people (Purtschert and Fischer-Tiné, 2015). After World War II and the subsequent decolonization of many colonial territories across the world, the peak of the colonial era diminished. In this postmodern context, Indigenous tourism was re-defined and conceptualized as “ethnic tourism,” and promoted in terms of visiting “exotic peoples” and “primitive homes” (Smith, 1996). The representation of Indigenous people and communities as primitive echoed the colonial modernist development ideologies which perceived Indigenous cultural systems, such as customary land tenure and traditional crop rotation, as obstacles to economic growth and development (Murray and Overton, 2011). Subsequently, the neoliberal development discourses of the 1980's, which was built upon the postmodern and colonial modernist ideologies, argued that Indigenous people should replace their subsistence-based economies with modern techniques for the sake of economic growth (Fry, 2019).

The expansion of the international tourism industry has been critiqued by scholars as early as the 1970's and 1980's, who argued that tourism is an exploitative form of neo- colonialism that destroys pre-existing cultures, human agency, and self-determination (Britton, 1982; Burns, 2008; Kothari, 2015; Mignolo, 2011; Park, 2016; Smith, 2018; Wijesinghe et al., 2019). This narrative gained popularity and was echoed by development scholars who characterized the tourism industry as foreign-owned multinational corporations that perpetuate unequal relations of dependence and encourage inequitable socioeconomic and spatial development (Brohman, 1996; Carrigan, 2011; Tucker, 2019). For instance, Moufakkir and Burns (2012) argue that tourism is a process that perpetuates colonial legacies of injustice and maintains countries in economically and socially submissive positions. Similarly, McKercher and Decosta (2007) propose that the construction of national identity and destination continues the master-servant relationship observed during colonial periods. Research conducted in Mauritius supports the former by suggesting that distinctive characteristics of a luxury hotel, which evoke the theme of the colonial sugar plantation, are designed to reproduce colonial spaces and representations in the tourist industry (Kothari, 2015).

From an environmental perspective, extensive studies have emphasized the negative consequences associated with tourism development in small islands states. Drawing on examples from tourism development in the Maldives, Kothari and Arnall (2017) demonstrate how externally born interventions can result in environmental change, commodification of nature, food insecurities, water shortages, and pollution. Similar research over the past few decades have also cataloged the long- term effects of tourism on the natural environment, including pollution and the depletion of common- based resources such as water and land (Briguglio and Briguglio, 1996; Cohen and Cohen, 2012; Gheuens et al., 2019; Kapmeier and Gonalves, 2018; McElroy, 2003).

In the cultural domain, the adverse effects of tourism on Indigenous people have been extensively discussed, particularly in terms of cultural appropriation and commodification (Richards, 2018, 2020; Young and Markham, 2020). In this light, the globalization of tourism has been regarded as a process that spreads social structures of western modernity, including neoliberal capitalism, democracy, and industrialization (Pieterse, 2019). Critics argue that such processes threaten the socio-cultural indigeneity of traditional societies and livelihoods through the imposition of western values and beliefs and the consequent erosion of cultural authenticity (Canavan, 2016; Cole, 2007; Connell, 2013; Heller et al., 2014). For example, a recent study conducted in Fiji, Tonga, and the Cook Islands illustrates how host communities have adopted western behaviors of tourists, including dress preferences in favor of more open and casual dress, increased expenditure on imported goods, and alcohol consumption (Tolkach and Pratt, 2022). In this sense, tourism is perceived as a threat to the social and cultural indigeneity of host communities by spreading social structures of western modernity and reproducing colonial imaginaries, which in turn perpetuate unequal power relations that privilege wealthy tourists over the Indigenous host communities.

Over the last two decades, concerns have been raised by Indigenous scholars that the development goals associated with the tourism industry do not consider the world views, priorities, and aspirations of Indigenous people (Kawharu, 2015; Yap and Watene, 2019). While some studies argue that tourism is no longer a threat for Indigenous people once it is aligned with sustainable development goals and responsible approaches that seek to empower host communities (Pereiro, 2016), most of the existing empirical evidence indicates that Indigenous people are often skeptical about engaging with the tourism sector due to decades of cultural appropriation from tourism, ongoing exploitation of Indigenous people, and misalignment between Indigenous values and the foreign-led industry (Bunten and Graburn, 2009; Carr et al., 2016; Scheyvens et al., 2021). In other words, tourism as a development strategy for SIDS is founded on western values and ideologies of success and wellbeing which do not neatly translate into Indigenous cultural constructs, values, and ways of being (Hughes and Scheyvens, 2020). The next section reviews the existing literature on Indigenous Pacific conceptualizations of wellbeing to provide a more respectful and culturally responsive understanding of how tourism affects the host Indigenous communities.

Conceptualizations of wellbeing in Pacific Island Countries

Indigenous people often have culturally-specific understandings of wellbeing that may differ significantly from Western or globalized concepts. These understandings are deeply rooted in their traditions, values, and worldviews. In the Pacific, many Indigenous conceptualizations of wellbeing are holistic, encompassing not just individual health but also community harmony, spiritual fulfillment, connection to land, and preservation of cultural practices (Nelson Agee et al., 2012; Puna and Tiatia-Seath, 2017; Richards, 2018). Pacific models of wellbeing are comprised of multiple elements from many small island nations across Oceania, including the Cook Islands, Niue, Tonga, and Samoa (Pulotu-Endemann and Tu'itahi, 2009). For example, representations of Pacific wellbeing can be seen in the Pacific Identity and Wellbeing Scale (PIWBS), which is the first psychometric measure developed specifically for Pacific people in New Zealand (Manuela and Sibley, 2015). The PIWBS is a culturally appropriate measure that assesses six factors of Pacific identity and wellbeing, which include: (1) perceived familial wellbeing; (2) perceived societal wellbeing; (3) group membership evaluation; (4) Pacific connectedness and belonging; (5) religious centrality; and (6) embeddedness (Manuela and Sibley, 2014). It is a unique tool as it provides a quantitative approach to understanding the holistic conceptualization of wellbeing for Pacific people.

Other presentations of such a multidimensional understanding of wellbeing can also be seen in the fonofale model of health, which is comprised of multiple individual elements from many small island nations, including Samoa, Tonga, the Cook Islands, and Niue (Pulotu-Endemann and Tu'itahi, 2009). In this model, the fale (house) symbolizes a resilient home, in which the floor, or foundation, represents aiga (family), including immediate relatives and extended family members. The roof is your culture, your beliefs, and value systems that provide protection and shelter. The roof and foundation are then supported by four pillars, which represent the spiritual, mental, and other aspects of your wellbeing such as sexuality, socio-economic status, and gender. The fale is surrounded by a cocoon or boundary that situates the five dimensions of wellbeing within its own physical environment, time, and context (Chand, 2020). In this way, the fonofale model demonstrates the importance and influence of external factors in shaping the various elements of a holistic wellbeing. More importantly, by acknowledging that wellbeing exists within a physical, social, and temporal context, the fonofale metaphor recognizes that wellbeing is dynamic and subjective.

In the Cook Islands, Indigenous scholars have mapped out five dimensions of wellbeing, which are kopapa—physical wellbeing; tu manako—mental and emotional wellbeing; vaerua— spiritual wellbeing; kopu tangata—social wellbeing; aorangi— total environment, that is, how society influences you and the way individuals are shaped by their environment (Aldinger and Whitman, 2009; Maua-Hodges, 2000; Te Ava and Page, 2020). Understanding this conceptualization is crucial when exploring the findings presented in this article. It allows for a more comprehensive assessment of how tourism might affect each dimension of wellbeing, from physical health impacts to changes in social structures, spiritual and cultural practices, and the local environment. This nuanced understanding can also guide more culturally appropriate ways of conducting research with Indigenous participants in the Cook Islands.

To illustrate how these five dimensions are woven together into a multifaceted concept of wellbeing, Indigenous Cook Islander scholars have applied the metaphor of a tivaevae, which is a large and colorful handmade quilt, crafted by a group of people (typically women) who aim to create a picture that tells a story (Maua-Hodges, 2000; Te Ava and Page, 2020; Rongokea, 2001). Originally proposed by Maua-Hodges (2000) as a model for underpinning education, the tivaevae metaphor has also been adopted by other scholars to locate culturally responsive pedagogy within the Cook Islands curriculum (Te Ava and Page, 2020; Rongokea, 2001). According to Rongokea (2001) the making of tivaevae suggests learning is a form of respecting the knowledge of others. In this sense, the tivaevae metaphor is a powerful phenomenon in the Cook Islands that represents the cultural process of sharing and transferring traditional knowledge and practices in research. The five key values of the tivaevae metaphor as a theoretical model to conduct culturally responsive research are: taokotai (collaboration), tu akangateitei (respect), uriuri kite (reciprocity), tu inangaro (relationships), and akairi kite (shared vision) (Te Ava, 2011).

While the research presented in this paper did not apply the tivaevae metaphor as a theoretical model to guide the research process, the research team adopted the key principles underpinning Indigenous Pacific methodologies to conduct semi-structured interviews with participants in a culturally responsive manner. Following the cultural guidance of Dr. Rerekura Teaurere, the research team weaved Indigenous Pacific knowledge systems with Western philosophies, and placed the core Pacific cultural values of reciprocity, relationships, and respect at the center of the research.

The research setting: Rarotonga, Cook Islands amid the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic caused an unprecedented disruption to tourism as international visitor arrivals plummeted amid widespread lockdowns and travel restrictions put in place by countries all over the world in order to contain the spread of the virus. On a global level, the sudden collapse of the tourism sector resulted in significant macro-economic losses and severe social impacts. As international travel plunged by 72% in 2020 and 71% in 2021, which represents 2.1 billion fewer international tourists worldwide in both years combined, over 100 million direct tourism jobs were at risk. This drop in foreign travel resulted in a combined USD 2.1 trillion over the 2 year period, which amounts to more than 2% of global GDP (Rahman et al., 2021). These catastrophic losses are magnified in SIDS particularly where tourism is the backbone of an undiversified economy and the primary driver of development.

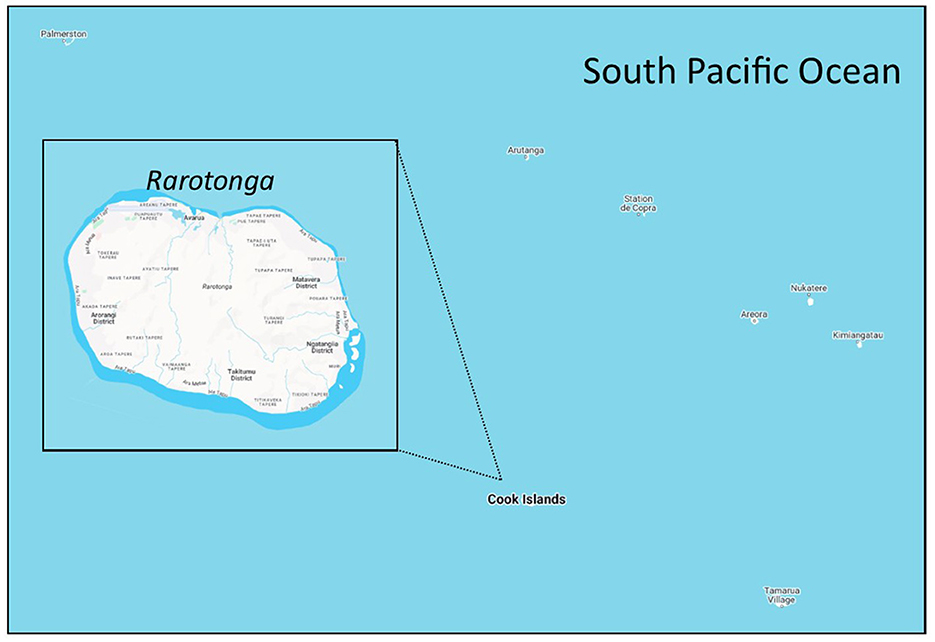

While the Cook Islands is a nation that is composed of 15 volcanic islands and coral atolls spread over about 2,200,000 km2 (Crocombe, 1973), the vast majority of international visitors (98%) spend time in Rarotonga, making it the epicenter of the tourism industry (Pacific Tourism Data Initiative, 2023). Prior to COVID-19, tourism contributed about 70% of the Cook Islands' GDP, or USD 354.8 million, and accounted for ~34% of the total local workforce (Currie, 2021). Yet, as a result of the international travel restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, Rarotonga's thriving and exponentially booming tourism sector collapsed—seemingly overnight. Research studies that documented the socio-economic impacts demonstrated a 37% increase in unemployment (Currie, 2021), and a dramatic decline in the nation's GDP of ~26% in 2021 (Webb, 2022). The tourism industries, including accommodation, transportation, travel agents, restaurants, and bars, all demonstrated negative growth (Tangimetua, 2021). Furthermore, over 93% of businesses, which are predominantly owned by local residents, reported a negative impact due to the international travel restrictions and border closures (Currie, 2021). Given that all participants interviewed reside on the main island of Rarotonga (Figure 1), their lived experiences and perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic were vastly influenced by the sudden collapse of the tourism sector, which for many of them resulted in unemployment, socio-economic pressures, and rising debt levels. Prior to presenting the results of this study, it is important for both researchers to acknowledge their positionality by considering how their personal experiences, cultural background, and identity may have influenced the research process and the interpretation of the findings.

Positionality of the research team

In this section, the two authors discuss their positionality by engaging in self-awareness. Dr. Roxane de Waegh does this through a process known as reflexivity, which is viewed as an explicit quest to limit the impact that a researcher has on the data production and analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2019; McGhee et al., 2007). On the other hand, Dr. Rerekura Teaurere presents her positionality through reflective autoethnographic vignettes, which is a method used by researchers to carefully self-monitor the impact of their biases, beliefs, and personal experiences on the body of research that can elicit perceptions, opinions, beliefs and attitudes (Pitard and Kelly, 2020). Furthermore, given that vignettes are essentially narratives that place the researcher in the center of an experience by providing insights from their own culturally constructed lens (Pitard and Kelly, 2020), this approach aligns with Indigenous methods to “(re)introduce the importance of stories into research” (Wiebe, 2019, p. 21) thereby contributing to the efforts of Indigenous scholars to decolonize research (Smith, 2019).

Positionality of Dr. Roxane de Waegh: A reflexive approach

As a Caucasian woman, raised in a tri-lingual European household, I was fortunate enough to travel the world, learn different languages, and be immersed in various cultures from a young age. By the age of 18, my family and I had lived in Senegal, Singapore, Belgium, Chile, Argentina, United States, and Japan. I then spent the majority of my 20's working with international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) focusing on marine conservation and community development projects in various remote coastal communities including Myanmar, Solomon Islands, Bahamas, Belize, and Timor-Leste. The experiences I had whilst working with INGOs fundamentally shaped the way I perceive development and conservation initiatives designed and implemented by foreigners in small island communities. It was through these experiences that I was able to understand the dichotomy in values, ideologies, and needs between host communities and international development and conservation agencies, and how these differences could lead to challenges that question the effectiveness of foreign-led strategies (including tourism)—especially in developing contexts where decisions tend to be influenced by an economically driven power imbalance.

Based on these lived experiences, I believe that the aspirations and needs of the local community must take precedence in any initiatives targeted at changing that community. As a researcher and a foreigner, I consider that I must seek to enrich meaning and understanding by representing the lived experiences and perspectives of the communities I am studying in the context of the research objectives, and to carefully consider my interpretation of the views during data analysis. I also recognize that I may never fully comprehend how research participants perceive reality, given that I believe in multiple realities that are each dynamic in concept and constantly evolving in response to changes in the social and natural environments. However, by reflecting on my own lived experiences and ideologies, I can begin to understand how my worldviews may influence the research outcomes.

Positionality of Dr. Rerekura Teaurere: A vignette approach

As an Indigenous scholar, I chose to write two vignettes to tell my own story in my own way through my Indigenous lens. The first vignette discusses my connection to Tongareva, the most isolated island of the Cook Islands which has no tourism. Tongareva is where my father, my grandparents, and their parents were all born and raised, right back to the three primordial lines of Tongareva. The second vignette shares my experiences living in Rarotonga, the most populated and most frequently visited island of the Cook Islands. To illustrate a snippet of what life is like on both Tongareva and Rarotonga, the following vignettes provide an imagery of my lived experiences of a Saturday market day. Although not all the impacts of tourism development are highlighted, the significant themes illustrated in these vignettes provide insights on how I perceive the role of tourism and the ways it has impacted the social, cultural, environmental, and economic aspects of my island nation. By reflecting on my lived experiences, I also consider how the continued growth and perceived success of island tourism may further impact our Indigenous people.

Tongareva

It's market day in Tongareva. It is a fundraiser for the girl guides new uniforms. We have to get there early to make sure we don't miss out. At 8 am we start walking the short walk to the market stalls. The sun is beating down hot already. The men had been out early spearfishing to catch the fish for the BBQ. The tatapaka (breadfruit pudding), takarari (sweet coconut flesh pudding), and poke (banana pudding) have been in the umu (traditional earth oven) overnight and everything is now ready to purchase. It smells delicious! We purchase a little of everything and wash it down with nimata (young coconut) drink. We know everyone at the markets. We see them during the week, every Sunday at Church, and while socializing after Church. There is always something new to talk about, so we eat while we talk and laugh. The music starts and at first the children start dancing, then the mamas, followed by the men. Everyone roars with laughter as the music and dancing continues.

After the markets, drunk on good feelings and happiness, we walk home and prepare to go swimming. At the beach, there is only our family group there and we relax in the shade of the pandanus trees. The men go and spearfish for tomorrows lunch. They wanted different fish to eat with the nato (small orange fish) they caught the night before when the moon was at 2 o'clock. When we get home, we will be preparing the umu for Sunday's lunch with our freshly caught fish, the rukau (large edible leaves of a shrub) from the garden, and freshly squeezed coconut cream. There will be plenty of food for us and any visitors to eat when we get home from Church.

Rarotonga

It's Saturday, market day, where the locals take their food, fresh produce and crafts to sell. We pile into my little Toyota Corolla, rusted and hardly roadworthy, but still going strong. It's 25 minutes to get into town. We drive to town past the tourists waiting for the bus outside their luxury resorts. In town, the roads are clogged. There are cars, motorcycles, and people everywhere. Most are tourists. When we finally get to the parking area and find a park we head in. First hurdle passed. There are so many people it's hard to get through the crowds. We see our family selling their rito (leaf membranes of the young coconut tree fronds) crafts and stop for a drink and talk before heading back into the stream of never-ending people to find fresh produce to purchase and something appetizing for brunch. There is a mix of locals, but most are tourists lured to the markets for the local culture, food, and to gaze upon the dance group that entertains during market time seeking monetary donations. We see a big bunch of bananas and my mind thinks back to two days prior when our banana trees were raided and bunches stolen. We pass on those and head to the breadfruit, the one tree we don't have growing. One breadfruit for $4 can make four meals. We find something appetizing for lunch, its $20 for one plate of food, but it's a treat so we go ahead and purchase it.

Finding somewhere to sit is the next mission. At last, we come across space on the bench for the three of us and we sit and enjoy our food. It's chicken, mushroom sauce with chips and salad and a cola to wash it down. Hardly locally grown food, but appetizing none the less and although we prefer fish, fish has gone up from $10 to $40/kg over the last 10 years so is unaffordable for us locals. After the markets we head to the beach. There are lots of tourists from the surrounding hotels snorkeling and splashing. I hide our valuables amongst our belongings. There have been instances of beach thefts occurring lately. After we swim, there is no shaded places left to sit on the beach, so we go home. We have not been to Church for a while as we have been rostered to work. The tourists keep coming, and so we need to cater to them. Tomorrow is Sunday and we are rostered to work again. So, for the rest of the day we do the household chores that have been neglected during the week.

As these vignettes demonstrate, the success of Cook Islands tourism through my experience felt intrusive, not only through crowding in certain areas as illustrated in the vignette above, but also in my daily experiences. I would have liked to have been in Rarotonga during the COVID-19 pandemic to experience a void of the domination of the tourist dollar in my everyday experiences, replaced by the focus on heightening the cultural, social, environmental, and spiritual wellbeing domains that have for years been shadowed by the economics of tourism development.

In summary, while the two authors stem from different cultural backgrounds, and have vastly different lived experiences, they have a shared passion and interest that motivated them to conduct this research. Both researchers believe that foreign-led development strategies often do not align with the needs, values, and priorities of the communities they are trying to change. Furthermore, they both consider that in order for international tourism to effectively meet the needs and desires of Indigenous people, there is a need to understand the impacts of the industry through the perspectives and lived experiences of Indigenous people, and the meanings they attributed to these experiences. Finally, Dr. Rerekura Teaurere and Dr. Roxane de Waegh believe that such an understanding can be achieved by listening to and respecting the ways in which Indigenous people perceive the role of tourism in supporting their subjective wellbeing. The next section provides a detailed summary of the methodology and methods used which enabled the research team to remotely collect qualitative data despite the international travel restrictions and lockdown measures ensued by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

From a western perspective, the qualitative research design follows an inductive approach “directed at providing an in-depth and interpreted understanding of the social world of study participants by learning about their social and material circumstances, their experiences, perspectives and histories” (Snape and Spencer, 2003, p. 3). Since Dr. Rerekura Teaurere and Dr. Roxane de Waegh believe there are multiple realities and that there is no singular verifiable truth (Feig and Stokes, 2011), both authors consider they must seek the truth from various perspectives by valuing subjectivity and getting involved with the participants to try and understand the phenomena in their contexts, rather than being an observer (Mills et al., 2006). In Western philosophical terms, this way of viewing the world and of conducting research is known as a constructivist research paradigm (Guba and Lincoln, 1994). The aim of a constructivist research paradigm is to understand the subjective world of human experience by acknowledging that multiple realities exist, and that knowledge is socially constructed.

This way of perceiving the world fits with Pacific worldviews, for which the core values are about relationality and relationships, communities, and the collective rather than an individual representation (Ihara and Vakalahi, 2011). Indigenous Pacific research methodologies are about finding connections, including relationships between communities and researchers, which are often disconnected in Western research (Goodyear-Smith and 'Ofanoa, 2022). By placing the core principles of tu inangaro (relationships) and taokotai (collaboration), the role of the research team is to work together to represent the views and perceptions of the participants and to collectively consider their interpretations of those views in the analysis and evaluation of the data. The result of integrating and weaving together different perspectives can lead to an overall understanding of the research objectives from a holistic standpoint (Mullane et al., 2022).

Developing research partnerships based on reciprocity, relationships, and respect

The research team strived to place the cultural values of reciprocity, relationships, and respect at the center of the study by developing meaningful and respectful relationships between each other, and with participants. Dr. Rerekura Teaurere and Dr. Roxane de Waegh started developing their relationship nearly 3 years ago, on 18 January 2021, when they first met during a cultural consultation meeting in Auckland, New Zealand. During the next few cultural consultations, Dr. Rerekura Teaurere shared valuable insights from both a professional academic's perspective and a cultural perspective. She taught Dr. Roxane de Waegh how to conduct research in a respectful and meaningful manner so that her doctoral research study could benefit the local research capacity and priorities of Indigenous Cook Islanders. Together, they discussed the importance of akairi kite (shared vision) and how they could continue to build connections between researchers and participants by creating a shared vision of the research process not only between themselves, but also with the participants.

Creating a shared vision and co-designing open-ended interview questions

From January 2021 to April 2021, the research team in Auckland conducted a series of consultation meetings with potential participants in Rarotonga via Zoom to identity the concerns, needs, and research interests of Indigenous Cook Islanders. By gaining cultural familiarity and listening to the perceived needs of local Rarotongans during the reconnaissance phase and consultation meetings, they were able to align the research goals with locally identified needs and challenges. During the months that followed, the research team applied the iterative constructivist grounded theory process to collect and analyze the data from each cultural consultation meeting. After analyzing the data from consultation meetings, an approach known as the “trade-off analysis” was applied (Brown et al., 2001) to develop open-ended interview questions that were culturally appropriate and reflected the interests of the local community.

The trade-off analysis approach uses envisioning techniques to engage diverse stakeholders in a discussion on what their visions of a sustainable future looks like, while considering the trade-offs between ecological, social, and economic impacts across various sectors and scales (Brown et al., 2001). According to Bandura (2006), the process of visualizing the future is a key component of human agency by allowing participants to self-regulate actions based on personal values, and to develop an approach based on a desired vision or goal. This in turn links the concept of human agency with notions of subjective wellbeing and social capital (Barnett and Waters, 2016). As such, by linking notions of human agency with wellbeing through a process of visualization, the trade-off analysis approach was considered appropriate in relation to the study's research objectives, which aimed to develop an understanding of how participants perceived the role of tourism in supporting their desired state of wellbeing, and their efforts for self-determination.

Furthermore, the trade-off analysis was also perceived to be an appropriate research approach because it allows scholars to explore how different variables influence an individual's and/or a community's ability to make decisions regarding a particular development, conservation, and/or adaptation goal (Narayanan et al., 2021; Galafassi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2022). Hence, by applying the trade-off analysis technique, this research was able to explore how the disruption of COVID-19 and the subsequent collapse of the tourism sector may have influenced participants' perceptions on the role of tourism supporting their subjective wellbeing. Finally, since the trade-off analysis strategy recognizes the need to include multiple stakeholders' perceptions and interests, it does not assume a unified community. Rather, it acknowledges the heterogeneity of small island communities, which is often overlooked in development studies that tend to idealize Indigenous island societies as homogenous, pristine, and free of problems (Cote and Nightingale, 2012).

Reciprocity and respect

By following the cultural guidance of Dr. Rerekura Teaurere, and upholding the cultural values of reciprocity and respect, this study aimed to ensure that benefits accrue to research participants in ways that are most meaningful and effective for them (Teaiwa, 2004). This involved providing participants with transcripts of their interviews and visiting the communities in Rarotonga to report orally the findings of the research. Other gestures of reciprocity include: (1) co- presenting some of the key findings with Indigenous youth participants at the 5th Pacific Islands Universities Network (PIURN) Conference, hosted at the University of South Pacific (USP) in Rarotonga, Cook Islands; (2) the contribution of a young artist in Rarotonga who designed an illustrative book that summarized the main findings; (3) the gifting of 40 copies of the illustrative book to participants, their families and friends, and various other sectors of the local community in Rarotonga including schools, libraries and environmental NGOs; (4) and co-presenting at an international research conference with Dr. Rerekura Teaurere, in addition to publishing two journal articles together in top tier journals. However, the most powerful outcome was the emergence of an invaluable friendship between Dr. Roxane de Waegh and Dr. Rerekura Teaurere. The following excerpt highlights Dr. Rerekura Teaurere's reflections regarding her experience as a research partner in this study:

COVID has reset the scene for how research is done. It restricted travel and created many barriers to research. Most significantly, regarding the border closures, is that it stopped the fly in and fly out approach to research. I have worked in the Cook Islands and have observed, and been involved, in research done by outsiders. There may be good intentions with aims of local capacity building, and involving local stakeholders, but this often falls short of a ‘tick the box requirement' for the local research permit. Participants' contribution to the investigation was not respected, reciprocated, and relationships were not developed or maintained. What stood out the most for me in this presented research is how the values of respect and reciprocity were at the forefront of the research.

Hence, the relationships that developed between the two researchers, and between the researchers and participants, were an invaluable contribution to this study. Without the cultural guidance and support from Dr. Rerekura Teaurere, Dr. Roxane de Waegh would not have been able to undertake the complex task of conducting remote data collection from New Zealand in Rarotonga, Cook Islands amidst a pandemic.

Selecting the participants

The research team relied on Dr. Rerekura Teaurere's extensive socio-cultural knowledge and understanding of the local context for the purposive selection of participants. Initially, discussions were conducted with various stakeholders during the reconnaissance phase to establish an understanding of potential participants, sectors, and/or organizations that can contribute insights and further develop a level of understanding of the questions being explored (Weller et al., 2018). A total of 25 participants from Rarotonga were recruited, which included individuals from various government ministries, environmental NGOs, the tourism sector, traditional leaders, the religious sector, high school teachers, Indigenous youth, fisherfolk, farmers, and the private sector. The diversity in participants was perceived as an advantage rather than a challenge, since the aim of this study was to explore diverse knowledge and voices by allowing different perspectives and interests to be articulated. In addition to facilitating contact with potential participants, Dr. Rerekura Teaurere also became an advocate for the research project and negotiated access to certain organizations, NGOs, and government ministries of interest. For example, Dr. Rerekura Teaurere was instrumental in introducing the research team to a local environmental NGO in Rarotonga, which enabled us to engage with Indigenous youth participants.

Semi-structured interviews on Zoom

The perspectives and lived experiences of participants were explored by conducting in-depth, semi- structured interviews rather than formal interviews. Semi-structured interviews seek to explore the subjective responses and meanings that participants attribute to their lived experiences by using open- ended questions that define the area to be explored (Bartholomew et al., 2000). The open-ended nature of the interview questions offers a highly flexible approach to the interview process by allowing the researcher and participants to diverge from or pursue an idea in more detail (Rakic and Chambers, 2012). This flexibility further increases the responsiveness of the interview by allowing space for participants to decide which questions they wish to elaborate on based on their interest and willingness, and permitting researchers to ask probing questions based on the participant's responses (Longhurst, 2003). According to Rabionet (2011), the flexible and informal process which guide semi-structured interviews has been found to foster reciprocity between researchers and participants. In this way, while Indigenous methodologies such as talanoa were not used per se, the research was conducted in a culturally responsive way by sharing ideas and stories (Movono et al., 2022), listening and allowing space and silence (Vaioleti, 2006), upholding the Indigenous values of reciprocity, relationships, and respect (Te Ava, 2011).

Due to the international travel restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, all 25 interviews were conducted verbally on Zoom, which is a collaborative, cloud-based video conferencing service (Zoom Video Communications Inc., 2019). While all interviews were audio-recorded, no video recordings were taken to ensure the privacy of participants. The interviews lasted between 45 minutes and 2 hours, and were all conducted in English. While the Cook Islands have three official languages, including Cook Island Maori (also referred to as Te reo Ipukarea), Pukapukan, and English, Dr. Rerekura Teaurere assured the research team during the reconnaissance phase that nearly everyone in Rarotonga speaks proficient English. Indeed, every participant interviewed in Rarotonga was fluent in English, and thus there was no need for a translator.

Data analysis

In a qualitative study guided by a constructivist grounded theory, the approach known as the constant comparison method is frequently used to analyze data (Charmaz, 2006). A constant comparison method is where the analysis of qualitative data proceeds alongside and informs future data collection in an iterative process (Tie et al., 2019). The process of constant comparison requires the researcher to go forwards and backwards between transcripts and the literature, revising open codes and making connections, and reading and re-reading data to identify patterns, similarities, or differences to understand the meaning of the data (Charmaz, 2006). Through this continuous cyclical process, open codes will develop into focus codes, and it is the grouping of these focus codes that creates the categories (Burns, 2008). In the final stage of analysis, categories are refined and merged to form theoretical codes, which provide a framework for a potential theory (Mills et al., 2022).

Prior to conducting the constant comparison method, all interviews were first transcribed by the second author. Following transcription, transcripts were emailed back to any research participant who requested to review the information and be informed of the findings (which all participants did by ticking a circle in the consent form). This allowed participants to check for authenticity, give feedback, validate or challenge the data, and provide opportunity for re-analysis. By returning the transcripts to the participants, this research adheres to the recognized principles of grounded theory, which require the description of data to reflect the participants' experience (Glaser and Strauss, 1999). After all participants had a chance to look over their transcripts and confirm the validity of the data, the transcripts were uploaded on the qualitative data software NVivo, and a process known as “light analysis and memoing” was conducted by both authors (Lester et al., 2020).

During this initial analysis phase, the authors took notes of the ideas or experiences described by participants that appeared in the transcripts. These initial understandings can often inform a researcher's later, more detailed analysis, and help them become familiar with the body of data, so that a researcher is aware of the limitations or gaps in the data (Lester et al., 2020). In this initial phase, it is helpful to generate memos that describe initial reactions about the data, as well as any emergent interpretations (Saldaña, 2021). The aim of these memos is to capture emergent understandings, as well as to identify potential biases that may influence the interpretation of the data, thereby contributing to the academic rigor of the study's findings (Vanover et al., 2021). Once the light analysis process was complete, the data was then coded by using the three stages of coding found in the analysis process of constructive grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006). During the initial coding stage, descriptive codes with a low level of inference (Lester et al., 2020) were created by inductively generating as many ideas as possible from the data. In the second focused stage of coding, connections and patterns were identified between statements, experiences, and reflections offered by participants to create codes at a higher level of inference (Cunningham and Carmichael, 2017).

As focused codes inter-related and contrasted with one another, categories began to emerge, which is an important intermediate step in the final coding process known as theoretical coding. Theoretical coding is the process of creating themes that are inclusive of all the underlying categories by recognizing similarities, differences, and relationships across categories, as well as being descriptive of their content and the relationships between them (Birks et al., 2019). Since themes are generally aligned with the conceptual or analytic goals of the study, themes were grouped together by questioning how the categories (inter) relate with each other in response to the study's primary question. The themes that emerged from the data were discussed between the two authors. Dr. Rerekura Teaurere had a leading role in these cultural discussions, given her socio-cultural knowledge of the context and her invaluable contribution throughout the project.

Ethical considerations

Formal ethics approval to conduct this research was granted by the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (AUTEC) on 9 February 2021. Ethics approval in New Zealand is underpinned by Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi), which covers the principles of partnership, participation, and protection. To obtain ethics approval, a researcher must submit an ethics application (EA1) in accordance with university policy. The ethics application submitted outlined the design and practices of the research, explained the methods and processes to be utilized, and clarified the intended benefits for the research participants, the researcher, and the wider community. To comply with ethics requirements, all participants were informed that participation in this study was voluntary, and that they had the right to stop participation and withdraw from the study at any moment. All participants received a participant information sheet and signed a consent form before contributing to the study.

Results and discussion

The aim of this article is to develop a deeper understanding of how participants, who identify as Indigenous Cook Islanders, perceive the role of tourism in supporting their wellbeing by exploring their lived experiences, and the meanings attributed to these experiences, during the sudden collapse of the tourism sector and the absence of the international visitors. While 25 semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants in Rarotonga, Cook Islands, not all participants identified as Indigenous Cook Islanders. Furthermore, due to the various cascading and inter-sectoral impacts ensued by the COVID-19 disruption, not all participants discussed their experiences in relation to tourism. As such, selected findings from seven interviews with Indigenous Cook Islanders are used to illustrate the key findings pertaining to this article's main objectives. To enhance the cohesion between the presentation of results and the analysis of the data, this section combines the data with an interpretive discussion of the findings.

The section is separated into five sub-sections. The first sub-section provides insights on the main categories that emerged from participants' responses to the question: what is your vision of wellbeing for your community and how would you describe that vision? The subsequent four-sub sections reveal findings on the four key themes that emerged from participants' responses to the question: how did you perceive the impacts from the COVID-19 disruption on your visions of wellbeing? This question was carefully designed to ensure that participants were not led or encouraged to only consider how their wellbeing may have been impacted by the sudden collapse of the tourism industry. Furthermore, the question does not imply that the impacts from the COVID-19 disruption were negative. This in turn allowed participants to reflect on both positive and negative impacts ensued by the global disruption. The findings revealed that despite experiencing severe negative economic impacts, participants considered that an increased sense of awareness of pre-existing issues linked to the tourism industry was the most beneficial impact that resulted from the COVID-19 disruption. The four key pre-existing issues discussed by participants are: (1) decreased local access to local produce and fisheries; (2) commodification of culture; (3) loss of traditional practices, ways of life, and cultural identity; and (4) environmental degradation. In the absence of international visitors, participants explained how each of these four challenges were temporarily remedied as evidenced in the resurgence of traditional practices, increased access to affordable produce, decrease in pollution and waste from tourists, and a revival of cultural identity and a sense of pride in place.

Participants' visions of wellbeing

The data revealed that participants considered having a strong relationship with their natural environment is essential for the holistic wellbeing of their community and surrounding ecosystems. For example, a participant described wellbeing as a reciprocal relationship between humans and the environment by referring to the concept of tiaki. According to Te Ava (2011), relationships that are reciprocal in nature pave a pathway for open dialogue, mutual respect, and the distribution of power. In this light, reciprocity enables empowerment and engagement within relationships, which strengthens the bond between individuals, within a community, and with the environment (Solomon and Tarai, 2022).

When I explain to people what wellbeing means for our natural environment, I always bring up that notion of Tiaki, that you are a guardian for today, and for tomorrow… Nature is intertwined with my genealogy and my being… We have a connection, which is our piri anga, to the land, to the sea, and to the air. And so our piri anga is cemented to our papa‘anga, which is our genealogy. So this connection helps me to maintain that view point in terms of protecting it today and for the future, because we are Tiaki. We are the guardians of the future. It's all interlinked, we are all interlinked. What we do effects nature and what happens, and whatever nature does it affects us as well, so we need to look after each other. (NGO sector)

The multidimensional concept of wellbeing was also described by participants in relation to the concept of pito'enua (umbilical cord) which consists of the five components of wellbeing previously discussed (p. 4): Notably, the pito'enua model does not include the financial or economic dimensions of wellbeing.

Pito is your belly button, and enua is your land, and there is a saying by a chief that when you plant your pito, your afterbirth, in your land, you are anchored to that land and you will always know who you are, and you can go forth and thrive… so for me, to be anchored by my pito or for a Cook Islander to think about their health and wellbeing, they have to be anchored to the land. So that concept of social wellbeing is intrinsically linked to the environment through our social health, and our mental and emotional health, and our physical health obviously. (Education sector)

The data revealed that participants considered basic needs (food, shelter, education, reliable minimum income, health, and employment) are essential components for the wellbeing of their community. The following quote by a participant from the government sector emphasizes the importance of basic needs to achieve wellbeing in their community.

Wellbeing for my community would be an equitable pay rate, and where the minimum wage can meet your basic needs for housing, feeding yourself, sending the children to school, and where the gap between the lowest earner and the highest earner isn't too large so that everyone has adequate access to sanitation, water, electricity, food, and a healthy home. (Government sector)

Finally, the importance of culture, traditional values, practices and knowledge, language, religion, spirituality, and respect for the elders and ancestors were also considered to be key aspects of participants' wellbeing. A vision of wellbeing that emphasizes a strong cultural identity is elucidated in the following quote from a participant in the education sector.

Wellbeing is where people feel happy about what they have and are proud of where they are from, so I guess a sense of culture, a sense of who you are, and respect for each other, tolerance for individual identity. (Education sector)

The next four sub-sections present an interpretive discussion on participants' increased awareness of the four main pre-existing issues linked to the tourism industry, which are (1) loss of traditional practices, ways of life, and cultural identity; (2) commodification of culture; (3) environmental degradation, and (4) limited access to local produce and fisheries.

Loss of traditional practices, ways of life and cultural identity

Indigenous scholars have argued that the shift from subsistence living to a cash-based economy with tourism development has transformed the very foundations of Indigenous wellbeing (Matatolu, 2020). The transformation of agricultural land to meet the development needs of a booming tourism industry has been responsible for the loss of traditional land use and management which has been acknowledged in Te Kaveinga Nui Cook Islands National Sustainable Development Plan (NSDP) 2016–2020 (Cook Islands Central Policy and Planning, 2016). According to the NSDP the growth of the tourism industry and consumeristic behaviors have coincided with the decline of agriculture as an industry. As a result, land that was once used for agricultural production has been converted to residential or commercial use, mostly for tourism. In the absence of tourism, participants became acutely aware of how tourism “created a need for more,” as evidenced in the following quote from a participant in the tourism sector:

Tourism created a need for more… even amongst our local people. For example, it's like—okay—we've got this holiday home, we've got another section there, we are gonna go and develop over there as well, another holiday home so we can make more money… kind of like a capitalist [laughter]. You know, that sort of thing… it's a bit sad. I guess it comes down to the individual and their values. (Tourism sector)

Furthermore, as these patterns of consumption and development continue, less land is available for agriculture, which decreases the ability of Cook Islanders to produce their own food and may pose threats in terms of food security. However, in the absence of visitors, participants described a resurgence of traditional practices as many people went back to planting and farming. Participants also discussed being able to spend more time with their extended family, going to church, and providing support for one another, which all contributed to a renewed sense of community spirit.

The community spirit has returned, I would say it has come back. Pre COVID, people were busy with work. You had to do this, you had to run after that, run after this. But during COVID, people have had more time to spend with our family! People have renewed their community spirit, they started working together, they set up working groups in the villages to go out and help the elderly and people with disabilities, to clean up their yard, assist them in getting things done like fixing roofs. (Private sector)

I really do see a lot of families going back into planting taro as their food security, and they realized that with COVID and everything we might not get the chance to have a lot of supply of food. And so, we do realize that and we have shifted back into our agricultural practices. That was basically the positive impact that I have seen from COVID. (Agriculture sector)

In a recent study, Scheyvens et al. (2023) observed similar patterns and noted that in times of need, Pacific people draw on their traditional knowledge and practices and utilize their social structures and environmental systems which contributes to improving overall wellbeing.

Cultural commodification

Cultural authenticity and identity were also perceived to be strengthened through the resurgence of traditional cultural practices. As one Indigenous youth participant described, in the absence of international visitors, dancing was not commodified, rehearsed, or performed for the tourist gaze, but rather it was performed for the satisfaction and enhanced wellbeing of Cook Islanders.

People now—they don't do the cultural dances in a group for the fun of it, you know, just dancing to enjoy the entertainment for themselves—they would rather get paid and learn the cultural dances to show the tourists and people that come to the Cook Islands—like they don't practice it for themselves or for entertainment for themselves or in their groups—they would rather learn it just to make money and for the people that come to the Cook Islands. (Youth)

Within the existing literature, some studies claim that tourism can revitalize, revive, and preserve culture and traditions (McKercher and Ho, 2011). However, the findings from this study contradict the former. As evidenced in the following quote, participants perceived that their culture can be appropriated and commodified by tourism, causing scholars to question the agency of Indigenous people in cultural representation (Kannan, 2023):

I think the biggest threat [to our wellbeing] is the loss of cultural identity by being really influenced by tourism as we become more reliant on their [tourists] needs. That causes us to not focus on the things that we already have and it kind of shifts the focus to what we want, which is a push for tourism and the economy and being more advanced. And so that would probably cause a loss to our identity. (Government sector)

The findings are supported by an Indigenous Pacific scholar who demonstrates how Polynesian cultures continue to be represented by imageries of “dusky maiden,” “happy, welcoming native,” “noble savages,” and sexualized images of vahine (women) with a backdrop of sea, sand, and sun allure (Tamaira, 2010). On the other hand, Kannan (2023) suggests that cultural tourism for Indigenous Pacific Islanders is a unique asset that can provide a pathway for greater independence and economic development, but it can also be critiqued as a neo-colonial pathway for the commodification of culture and nature (Taylor, 2001). By exploring how participants perceived the impacts of tourism in terms of cultural commodification, the data revealed how tourism negatively influences Indigenous Cook Islanders' wellbeing by depleting their sense of cultural pride and identity.

Environmental degradation

In terms of environmental wellbeing, the data further indicated that participants became more aware of the pre-existing environmental issues linked to the uncontrolled development of the tourism industry.

Over the last 30 years, I would say there has been rapid development in tourism. However, alongside that development, there has been the slow degradation of our environment. So, you can see that although it brought massive economic opportunities, and it increased our national income and GDP tremendously, with that wealth there is also the negative side of it. Waste, plastics, bottles, you name it. So, there is that fine balance between extracting the benefits of tourism and trying to maximize tourism at the expense of your own natural environment. (Elder)

These perceptions are supported within the existing literature and recent empirical evidence found by the New Zealand Tourism Research Institute (2019). In 2019, NZTRI found that approximately half of all Cook Islanders considered that tourism has negatively impacted their natural environment. According to Everett et al. (2018), since the tourism industry in the Cook Islands is unregulated, the lack of zoning plans has enabled the construction of hotels and resorts along environmentally sensitive areas, including the foreshore, wetlands, and along the shoreline of Muri lagoon, a significant tourist attraction and the largest tourism revenue earner in the Cook Islands. A recent study indicated more than 90% of businesses along Muri's sensitive shoreline had non-compliant and substandard septic systems, which have begun to leach nutrients in the lagoon, causing toxic algal blooms and damaging the marine life (Evans, 2019).

Moreover, solid waste was brought up as a concern from tourism development. A waste audit report for the Cook Islands carried out in 2021 illustrates the substantial contribution of solid waste from tourism. Although there was no data provided for Rarotonga, Aitutaki accommodation providers reported that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when the tourism industry was at its peak, waste was 280 kg/month. Research demonstrated that in the months following the international border closures and subsequent collapse of the tourism industry, these figures drastically dropped to 20–41 kg/month from April 2020 to June 2020, and 0 kg in July 2020 and August 2020 (Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility, 2021). As such, there is a clear correlation between tourism development and environmental degradation, which was also perceived and experienced by the participants of this study.

Limited access to local nutritious food and fisheries

Finally, the findings demonstrated that participants became acutely aware of how tourism impacts their access to nutritious local produce and freshly caught fish. As a result of the dwindling numbers of international tourists, participants enjoyed cheaper prices for local fish and agricultural produce, which were previously too expensive for locals to afford due to the higher price margins set for tourists.

So when the borders closed, tuna and other tuna like fish, were amazingly cheap and people could afford to buy tuna regularly, we were getting tuna maybe twice a week as opposed to before COVID where it would be perhaps once a fortnight or once a month—so tuna, when the borders closed, it was around 10 dollars a kilo—almost immediately after the borders opened, tuna went up to 25–28 dollars a kilo. (Private sector)

These findings are supported within the existing literature where scholars have argued that tourism development in SIDS creates shortages of scarce resources like water and energy, in addition to decreasing locals' access to local agriculture produce, fisheries, and affordable housing (Bianchi, 2009; Dodds et al., 2018; Rutty et al., 2015; Sinclair-Maragh and Gursoy, 2015). Furthermore, studies found that parallel to tourism development in small island nations is the decrease in local food production, and the subsequent increased dependence on non-nutritious imported products (Guell et al., 2022). The findings support the former as participants discussed the positive impacts they experienced in relation to their nutritional health as a result of having more access to their own nutritious local produce.

People are eating a bit healthier now because there is a lot more agriculture produce—there is a huge agriculture push, so we are eating more vegetables because normally the vegetables and fruits are not available for us, it goes into the tourism industry so locals would rely on imported stuff so now we are eating fresh vegetables, fresh fruits, a lot more people are using or selling local produce, coconuts are on the side of the road, mangos, we never had this much fruits available to us in the past. Because it always goes to care for tourists. And that's one of our biggest issues here, is NCD, I mean it's a short time but I'm sure its helping in that area. (NGO sector)

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (2021), the average value of food production in the Cook Islands has declined from USD 231 per person in 2002 to USD 43 per person in 2018. Tu'akoi et al. (2018) found that the diminishing production of local food in the Cook Islands has contributed to a growing dependence on imported goods, and an increasing consumption of non-nutritious imported foods, such as canned meats, instant noodles, cereals, rice, and sugar-sweetened beverages (Charlton et al., 2016). Studies have recognized that the consumption of non-nutritious imported foods is the main contributor of Non Communicable Diseases (NCDs) (Snowdon et al., 2013), which accounts for nearly 75% of all deaths in the Pacific region (Hou et al., 2022). Today, 26.8% of the Cook Islands population is diagnosed with diabetes, which is significantly high when compared to 7.3% in Australia and 8.5% in New Zealand (Tu'akoi et al., 2018).

However, the act of reclaiming local foods, as evidenced in participants' lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, provides an adaptive alternative to dependence on processed and energy-dense imported goods (Bell et al., 2021). From this position, Davila et al. (2021) point out that the revitalization of small-scale agriculture and subsistence fisheries offers a systemic approach to improve diet quality, which in turn has the potential to improve the health of Pacific people. The findings from the presented study strongly confirm Davila et al.'s (2021) research as evidenced in participants' comments which described an increase in nutritional health and physical wellbeing as a result of the increased production of local food and a decreased consumption of imported goods.

Conclusion

Given the significance of tourism for the Cook Islands economy, the risks associated with tourism- dependent economies, and the already exponentially rising numbers of tourism arrivals in the Cook Islands since the re-opening of the borders in 2022, there is a pressing need to identify how the international tourism industry is impacting the multidimensional wellbeing of Indigenous Cook Islanders. Recent studies have shown that after achieving 100 per cent vaccination rate, the Cook Islands fully reopened their borders in 2022, and visitor arrivals jumped from 26,330 in 2021 to 113,551 visitors in 2022 (Cook Islands News, 2024). In 2023, the country welcomed 143,506 visitors, which is a massive increase of 29,955 in just one year, marking the fifth highest recorded arrival figures in the Cook Islands (Cook Islands News, 2024). According to the Cook Islands tourism migration statistics, 10,368 international visitors have already been welcomed in January 2024, which surpasses the pre-COVID-19 peak that saw 10,128 visitors in January 2019. These figures are alarming for a multitude of reasons, including the well-documented risks associated with tourism-dependent economies in the context of SIDS, and the limited knowledge on the impacts of tourism on Indigenous people.

The research presented in this article sought to develop a deeper understanding of how Indigenous Cook Islanders perceive the role of tourism in supporting their wellbeing by exploring participants' lived experiences during the global disruption of COVID-19. The findings revealed that despite enduring the negative economic and financial impacts from the collapse of the tourism sector, participants also enjoyed several positive experiences in the absence of tourists. For example, participants adapted to the adverse impacts of COVID-19 through the revitalization of their traditional socio-economies, resurgence of customary practices, strengthened connection to nature, and a renewed sense of community and pride in cultural identity—all of which were perceived to positively impact their spiritual, social, cultural, environmental, physical and mental wellbeing. By demonstrating the positive adaptive responses of participants, this article aims to emphasize the non- economic dimensions of wellbeing that are critical to supporting the cultural values, social priorities, and Indigenous ways of life that existed in the Cook Islands prior to the development of tourism. These findings can be used to inform and guide international development policy makers and tourism stakeholders who seek to reduce the adverse impacts of tourism development on the wellbeing of Indigenous communities in the Pacific.

In conclusion, the authors would like to emphasize the value of conducting research in a culturally responsive manner. The presented study is the result of a collaborative research partnership between an Indigenous Pacific scholar and non-Indigenous European scholar. While the research adopted a western methodology, the relationships developed between the researchers and participants were guided by the cultural values of reciprocity and respect, which are key principles underpinning Indigenous research in the Pacific. By modifying the use of western methods through the inclusion and respectful application of Indigenous values, this study aimed to avoid the adverse impacts of cultural appropriation which often result when non-Indigenous scholars use Indigenous methodologies without the consent of Indigenous scholars, and/or in the absence of Indigenous research partners. Moreover, the relationship that emerged between the two authors of the presented study enhanced the value of the findings by increasing access to Indigenous participants and local organizations which in turn offered unique insights that are often absent from the relevant body of knowledge. To conclude, in addition to contributing valuable insights to the growing field of Indigenous tourism by giving a voice to Indigenous participants, the implications of this study extend to include methodological contributions by exemplifying a culturally responsive way to conduct meaningful research in the Pacific region.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of privacy and ethical restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Roxane De Waegh, cm94YW5lLmRlLndhZWdoQGF1dC5hYy5ueg==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

RT: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. RD: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aldinger, C., and Whitman, C. V. (2009). Case Studies in Global School Health Promotion. Berlin: Springer.

Bak, I., and Szczecinska, B. (2020). Global demographic trends and effects on tourism. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 23, 571–585. doi: 10.35808/ersj/1701

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

Barnett, J., and Waters, E. (2016). “Rethinking the vulnerability of small island states: climate change and development in the Pacific Islands,” in The Palgrave Handbook of International Development, eds. J. Grugel and D. Hammett (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 731–748.

Bartholomew, K., Henderson, A. J., and Marcia, J. E. (2000). Coded Semistructured Interviews in Social Psychological Research.

Bell, C., Latu, C., Na'ati, E., Snowdon, W., Moodie, M., and Waqa, G. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to the introduction of import duties designed to prevent noncommunicable disease in Tonga: a case study. Global. Health 17:788. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00788-z

Bianchi, R. (2009). The ‘critical turn' in tourism studies: a radical critique. Tour. Geogr. 11, 484–504. doi: 10.1080/14616680903262653

Birks, M., Hoare, K., and Mills, J. (2019). Grounded theory: the FAQs. Int. J. Qualit. Methods 18, 1–7. doi: 10.1177/1609406919882535

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676x.2019.1628806