- 1Dinjii Zhuh Adventures, Whitehorse, YT, Canada

- 2School of Outdoor Recreation, Parks, and Tourism, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada

While there has been a general increase in Indigenous-owned and operated tourism companies across Turtle Island (currently known as North America), the same is not true for what is commonly referred to as “adventure tourism”, and specifically, in whitewater river canoe and raft guiding. There are still several barriers that continue to keep many prospective Indigenous guides out of the industry and off their traditional lands. This can work to perpetuate the myth that adventure tourism marketing relies on, that the rivers, lakes, and land they guide their clients on are an untouched and unpeopled “wilderness”. Peel River Watershed protector and activist Bobbi Rose Koe started an adventure tourism company, Dinjii Zhuh Adventures, to address these inequities. She aims to change the culture of guiding and tourism through introducing more Indigenous youth to their traditional watersheds, to train them as whitewater canoeing and rafting guides, and to support them in their employment and career development with the ultimate goal of land protection. This paper, co-written as a dialogue guided by the voice and perspective of Bobbi Rose, will weave together a story of the impact Indigenous presence has on the land, Indigenous youth, non-Indigenous guides and clients, other tourist operators, and the industry in general. Our conversation begins and ends with the role Indigenous presence plays in land and cultural governance and protection. We share these conversations, opportunities, challenges, and imagined futures to invite tourism researchers, operators, and guides to reflect, as well as to offer encouragement and camaraderie to other Indigenous guides and tourist operators.

Introduction

This paper, co-written as a dialogue, weaves together a story of the role of Indigenous tourism in Indigenous land governance and cultural resurgence and revitalization. Through her stories, Bobbi Rose highlights the impact Indigenous presence has on the land, Indigenous youth, non-Indigenous guides, clients, companies, and on the tourism industry as a whole. We hope the opportunities, challenges, and imagined futures shared and discussed in this dialogue will serve as valuable reflection points for tourism researchers, owners, and entrepreneurs, as well as offer encouragement and camaraderie to other interested, fledgling, and established Indigenous tourist guides, interpreters, and operators.

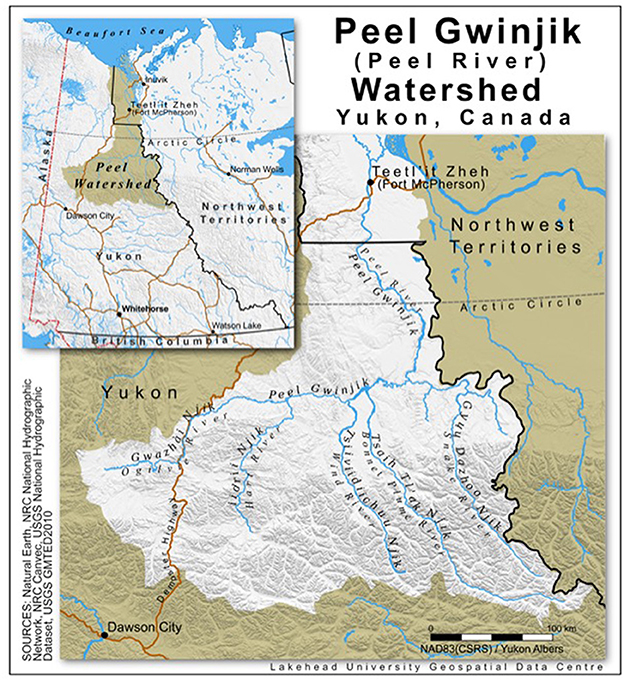

Bobbi Rose Koe spent much of her youth advocating for the protection of the Peel Watershed (see Figure 1). She was part of a delegate of Yukon First Nations who appeared at the Supreme Court, suing the Yukon Government for breaching Treaty obligations it signed in the Yukon's Umbrella Final Agreement (YUFA) with First Nations in 1990. The territory's proposed land management plan, which had 30% of the Peel Watershed marked for protection, was vastly different from the First Nations plan which had 80% protected (CBC News, 2017; Querengesser, 2017). In 2014, the year that plan was revealed, the Nacho Nyak Dun and Tr'ondek Hwech'in launched a lawsuit against the Yukon Government. The Gwich'in of Fort McPherson (see Figure 1) call themselves Teetl'it Gwich'in, or “the people of the headwaters”, referring to the headwaters of the Peel, and therefore also felt compelled and responsible to protect the watershed. Bobbi Rose joined her grandfather and other Teetl'it Gwich'in in these efforts (Ronson, 2014). She appeared alongside other First Nations delegates at the Supreme Court to defend their case. In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the First Nations (CBC News, 2017).

Figure 1. Peel Watershed and some of its associated rivers. Source: Lakehead University Geospatial Data Centre.

After years of being a youth advocate for the Peel Watershed, Bobbi Rose had her first experience of traveling down the Wind River (see Figure 1) for 17 days by canoe. This experience solidified the importance of building a relationship to the lands one is working so hard to protect and inspired her to introduce Indigenous youth to rivers in their traditional homelands. She hired various river guiding companies to help them travel safely on these journeys. Upon recognizing the harm that can be experienced by youth in these settings, she decided to become a guide herself. Experiencing the loneliness of being one of very few Indigenous guides in the adventure tourism industry while also witnessing the positive impact of Indigenous presence on the industry in general, she started to focus on training more youth to follow in her footsteps. She started her company Dinjii Zhuh Adventures (DZA) in 2020. DZA won the Arctic Inspiration award in 2022 which funded the inaugural Indigenous Youth River Guide Training Program (IYRGTP) in the Yukon, certifying and training five Indigenous youth in the industry. Since then, she has guided trips every summer with youth she trained as her co-guides. Notably, in 2023 and 2024, she guided alongside the youth she has trained.

Bobbi Rose Koe is Teetl'it and Vuntat Gwich'in First Nation, Dagoo and Dinji Zhuh, and was raised in Fort McPherson, NT. She now lives in the Yukon Territory. She works as the Community Connector for an Indigenous led organization called Western Arctic Youth Collective (WAYC), where she supports and works with youth and communities. She is also a professional facilitator and public speaker who works with organizations and businesses across Canada looking to create more opportunities for the North. She describes the work that DZA does as “Northern outdoor adventure tourism, education, and consulting.” She is an avid and talented artist, expressing her creativity through beading. I (KAL) am a food studies, systems, and food sovereignty scholar working as an assistant professor in the School of Outdoor Recreation, Parks, and Tourism at Lakehead University. I have been working for the past two decades as a lake and river canoe guide in many different places across Turtle Island. I come from German, Scottish, and Anishinaabe relatives, I am non-status, and I present in a white body. I co-own a whitewater paddling company for women+ humans called Braiding Rivers, which focuses on nourishing gentle, decolonial, and critically intimate relationships with the land while moving with the river by canoe. We directly name colonialism, white supremacy, and patriarchy as the drivers of Indigenous displacement on the land we travel through, and explicitly highlight the ways that tourist and recreational access to the river is facilitated by this displacement. We attempt to challenge these ideas and this continued displacement in our work and on our trips, and are constantly reassessing whether or not we are achieving this and how to do this better. We certainly have lots of room to grow. We are still, and likely always will be, learning.

Since we met 3 years ago, aptly on the Wind River (see Figure 1), Bobbi Rose and I have had ample time for conversations about DZA and Braiding Rivers, the guiding industry, and our mutual frustrations, successes, hopes, and goals. Like any meaningful relationship, we have had far more time discussing everything but—full of laughter, tears, sarcasm, and teasing. When informed of this special edition on Sustainable Indigenous Tourism, I forwarded it to Bobbi Rose and we both felt pulled to write something together. Bobbi Rose's experiences, voice, vision, and storytelling are the backbone of this piece. I try to situate her perspective within the literature and find meaningful connections. Literature connections, however, are not the focus of this piece—in the same way Bobbi Rose and DZA are re-presencing Indigenous bodies, knowledge and governance on the Land, we aim to join a growing resurgence of re-presencing Indigenous voices and knowledges in tourism literature.

Literature review

Indigenous entrepreneurship

While there has been a general increase in Indigenous-owned and operated tourism companies across Turtle Island (Graci et al., 2021), the same is not true specifically for what is commonly known as “adventure tourism.” While not categorically defined, “adventure tourism” can mean many things in many different contexts. It has been defined as “guided commercial tours, where the principal attraction is an outdoor activity that relies on features of the natural terrain, generally requires specialized equipment, and is exciting for the tour clients” (Buckley, 2007 as cited in Rantala et al., 2016, p. 2). The Adventure Travel Trade Association (ATTA), a global network of adventure travel leaders, defines adventure travel as “a trip that includes at least two of the following three elements: physical activity, natural environment, and cultural immersion” (Rantala et al., 2016, p. 2). Others use the idea of the “journey”, as something different from every day life, as a defining characteristic of adventure tourism. While Bobbi Rose's company operates within the broadly defined category of “adventure tourism”, this article centres Indigenous presence in tourism activities with adventure tourism as a context. However, our arguments for the importance of Indigenous presence in adventure tourism can apply more broadly to other tourism categories such as eco-tourism and nature-based tourism. Specifically, this paper is focused on river travel (via canoe or raft).

Adventure tourism is still predominantly owned, operated and guided by middle-to-upper-class, white, cis, hetero men, and increasingly women (Novotná et al., 2024). Even the terms “adventure tourism,” “outdoor recreation,” “outdoor adventure,” and “expedition” have colonial roots. Facilitating expedition-style tourist experiences requires high financial capital, for example, often relies on expensive equipment and travel, and is thus prohibitively expensive to start up for the owners and operators, a cost which trickles down to the fees for potential clients. This results in a participant demographic of high socioeconomic status, which often runs alongside other intersections of privilege, such as race and gender identity. This leaves many Indigenous youth, whose home territories are in the watersheds upon which many of these companies rely, without the industry-specific experience nor financial access to guide or travel down these rivers.

Obtaining certification to be a guide in the adventure tourism industry is largely inaccessible to those without a financial safety net. Many people in the industry make their way there from attending expensive youth summer camps and working low-paying summer guiding jobs, affording them the time and space to develop necessary skills and experience. Certification and renewal is expensive in time and money. To enter and stay in the industry, many young guides rely financially on their spouses, parents, or wider social network. It is a riskier industry to devote to without those safety nets, as the work is seasonal, jobs are insecure, and pay is generally low. This results in a very specific culture, which acts as another barrier for aspiring young Indigenous guides to enter the industry.

Lacking Indigenous presence impacts the tourism industry and also the academic literature. For example, in de la Barre's (2013) analysis of place-based tourism in the Yukon, she stated that there was a challenge in receiving first-person oral accounts of First Nations guiding and tourism. Therefore, the narratives about tourism in the Yukon are generally from a white-male perspective. She states that the long colonial narratives of “the North” lend itself to the creation of a fantasy of the Yukon's “remoteness” and “wilderness” as a site to test one's masculine capacities and capabilities, which she calls “Masculine Narratives” (de la Barre, 2013, p. 832). She states: “Masculinist Narratives and Narratives of the New Sublime are iconographic narratives associated with still romanticized accounts of the Yukon…They are narratives linked to a colonial and nation-building history, and in the light of this past, they rely on notions of an empty wilderness” (p. 835). The empty wilderness, a common trope in adventure tourism, requires the erasure of Indigenous peoples from the landscape, a trend long viewed as a perpetuation of colonial violence (Cronon, 1996; Newbery, 2012).

Canoeing and canoe trips are popularly viewed by tourists, tourism operators and outdoor educators alike as a neutral and uncomplicatedly “positive” experience, tending to ignore its theft, perversion, and ongoing role in the colonial project (Erickson and Krotz, 2021; Newbery, 2012; Strong, 2016; Simpson, 2017). Indigenous presence challenges the romanticism of the empty frontier, which can lead to racist comments and microaggressions from clients that are traumatic for Indigenous guides. These barriers effectively continue to keep many prospective Indigenous guides out of the industry and off their traditional lands. This perpetuates the land dispossession of Indigenous peoples and continues the myth that adventure tourism marketing relies on, that these rivers, lakes, and places are an untouched “wilderness” (Cronon, 1996; de la Barre, 2013), which effectively erases the socio-cultural, economic, and political context which enabled settlers the skills, time, and money to guide or be guided down these rivers. This allows tourists, guides, and tourism operations to sidestep the fact that settlers have access to these places because of Indigenous dispossession. Fortin et al.'s (2021) participant research with settler student-tourists reveals that they tend to view the land in ways that purposely obscure settler-colonialism, effectively re-writing the narrative of what their place on the land is. Everingham et al. (2021) describe the tourist entitlement evident following a climbing ban at Uluru. They unveil the coloniality that adventure tourism is steeped in, from the marketing to the experience itself. The myth of terra nullius and settler complicity in Indigenous erasure is avoided. However, the presence of Indigenous guides, companies, and tourists challenge this avoidance.

Indigenous presence on traditional lands allows Indigenous monitoring of these lands. A lack of presence can result in further dispossession, as resource extraction industries and land management systems such as parks can make more decisions with less opposition. The idea of presence for monitoring is prevalent in Indigenous guardianship and Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas literature and research (Murray and Burrows, 2017; The Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018; Mason et al., 2022). While these organized positions are important, casual, unplanned, and ungoverned monitoring through time being on and deepening relationships with the land that one loves and is connected to is equally important. As Bobbi Rose says, “you can't protect what you don't love”. Her work and company aim to remove the barriers that Indigenous guides, clients, and communities face to establish greater Indigenous presence on rivers across Turtle Island. This works toward sustainability of the land as well as of Indigenous guides, tourist operators, and the industry itself.

What is sustainable Indigenous tourism?

The UN's eighth sustainable development goal, to “promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all” includes sustainable tourism (United Nations, 2024). The World Tourism Organization defines sustainable tourism as tourism “that takes full account of its current and future economic, social, and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities” (UN Tourism, 2024).

Taking full account of the environment and host communities requires critical attention and focus. For example, while many adventure tourism clients consider themselves sustainable based on the mode of travel (often self-propelled) and the proximity to “nature”, there are many inconsistencies in this assertion (i.e., carbon emissions, gas, and oil used for travel to these locations, microplastics in the clothing and gear, etc.) which require a more critical and nuanced understanding of what “sustainable” means (Novotná et al., 2024).

Indigenous tourism can come in many forms including Indigenous interpreters and guides working for non-Indigenous companies, Indigenous-owned companies, community-driven efforts steeped in culture, stories, and spirituality, and Indigenous peoples as tourists. Peters and Higgins-Desbiolles (2012) describe Indigenous tourism as either a cultural product associated with Indigenous peoples, a cultural product desired by tourists who want Indigenous experiences, a marketing tool to “brand” a destination, and/or a tourism product owned and/or controlled by Indigenous peoples. These vastly different definitions can allow many different operations and activities to be considered Indigenous tourism.

Indigenous tourism is widely believed to be one way for Indigenous communities and entrepreneurs to create economic opportunities that depend on the preservation and ecological integrity of the land, reducing reliance on extractive and exploitative industries. Indigenous tourism, therefore, is a potentially more environmentally sustainable source of income and employment. However, it is not without costs—Indigenous tourism can also lead to further commodification of “Indigenous tourism products”, exposure to racism, as well as exploitation and inequity in company and project planning (Whitford and Ruhanen, 2016, p. 16). It is important to ask: what is Indigenous tourism sustaining, and for whom? Whitford and Ruhanen (2016) state:

Too often, tourism has done little to reverse the socio-economic disadvantage faced by Indigenous people who are still hindered by (among other things) the legacies of colonial history, ineffective and misguided government policies, and a lack of access to education, health services and employment. (p. 16)

This is why research that centers Indigenous voices and perspectives, an Indigenist approach, is imperative in tourism research (Calvin et al., 2024).

While there is a rise in Indigenous tourism and tourist operators (Cassel and Maureira, 2017; Graci et al., 2021; Graci and Rasmussen, 2023), it is not a new practice—it has long appealed to non-Indigenous, European adventurers who wish to seek, document, and experience “authentic” Indigenous cultures (Whitford and Ruhanen, 2016). This can sometimes encourage operators to shift and alter elements of Indigenous culture “to suit the visitor and the demand of the [tourist] gaze,” highlighting the power imbalances in host-guest relationships (Peters and Higgins-Desbiolles, 2012, p. 4). This can lead to tensions around what “authentic” Indigenous tourism is, and who gets to decide. Generally, it has been the tourist's (or academic's) gaze who assesses, based on their own preconceived notions of what authentic Indigeneity is without input from the hosts (Hsu and Nilep, 2015). The obsession with experiencing the “exotic” features prominently in literature and cultures beyond Indigenous North America, as post-colonial writers have long pointed to (Said, 1978). Some examples from North America include the writings of Farley Mowat, the film Nanook of the North (see Lepage, 2008), and the displacement of Indigenous culture to Germany as seen in Hayden-Taylor's (2017) Searching for Winnetou.

Combined with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), sustainable tourism is imbedded within larger political rights. Amongst others, the UNDRIP states that Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determine their own economic, social, and cultural development (Article 3), to improve their economic and social conditions (Article 21), to maintain and strengthen relationships with traditional lands and to pass these knowledges on to youth (Article 25), to own, use, develop and control these lands (Article 26), and to maintain and protect traditional and cultural heritage and knowledges (Article 31) (United Nations, 2007). These rights make it obvious that Indigenous peoples and communities have the right to govern tourism businesses and the cultural elements shared, as well as the land that these operations rely on. Carr et al. (2016) explains that:

tourism is only one tool to realize sustainable Indigenous (and also community) development, including Indigenous control over resources. The importance of governance, collaboration, and embedding Indigenous values and world-views in tourism development is unequivocally necessary to affect positive outcomes with any tourism venture. (p. 1075)

Bobbi Rose's journey in tourism encompasses all of these elements, from her beginnings as an advocate for traditional waterways, to deep collaboration with Peel Watershed communities and mentoring Indigenous youth culturally, economically, and socially.

In this paper, we take directions from Whitford and Ruhanen (2016) to produce research that is reciprocal, exploratory, and involves two way conversations and knowledge exchange. Further, we aim to follow their vision that:

the critical trend ought to be Indigenous people's involvement in research and the primary consideration at all times should be how and what do [Indigenous peoples] want from Indigenous tourism. (p. 24)

This paper joins other Indigenous tourism literature (see Johnston and Mason, 2021; Mason et al., 2022) which address Carr et al.'s (2016) call for more research by and in collaboration with Indigenous researchers and practitioners. Through showcasing a relatively nascent company, DZA, from the perspective of the founder and owner, Bobbi Rose, this paper aims to contribute to this growing conversation.

Methodologies, methods, analysis

This paper is guided by relationality (Wilson, 2008) and authentic, reciprocal relationships (Kovach, 2009, 2005, 2019) as emphasized by Indigenous and decolonial methodologies (Smith, 1999). Archibald et al. (2019) lay out seven key principles of Indigenous theoretical, methodological, and pedagogical framework: “respect, responsibility, reverence, reciprocity, holism, interrelatedness, and synergy” (p. 1). We hope that this paper brings the candidness of a conversation between two dear friends to the density of academic writing. In that levity, Bobbi Rose raises profound critiques of and insights into the past, present, and future of Indigenous tourism in the North. We want to present our paper this way in order to ground literature into the embodied emotional, spiritual, and material experiences of people working in the field. While in some ways, I feel like we have no right to be in this edition (neither of us are tourism scholars), in another way, it is important that we are.

Conversation is an important methodological approach (Bessarab and Ng'andu, 2010; Walker et al., 2014). This paper is written as a critical dialogue and personal narrative, which follows collaborative and evocative autoethnography as a methodological approach (Shepherd et al., 2020). As Shepherd et al. (2020) do, the analysis in this paper happens through the story and within the creation of the story through the conversation. Instead of breaking it apart into pieces, we have left the conversation as close to the original verbatim as possible, while also emphasizing important themes and maintaining the flow of a stream of narrative, similar to Swain et al. (2024). In this conversation, we are two guides working in “contested” tourist spaces. While vastly different from Shepherd et al.'s (2020) context in Israel-Palestine, in settler-colonial countries, arguably every adventure tourism company operates in a contested space. This conversation revolves around how that space is navigated by the guide—specifically centering the experience of Bobbi Rose, in line with Calvin et al.'s (2024) Indigenist approach to tourism research.

This paper captures the essence of three conversations Bobbi Rose and I had over Zoom. The conversations were recorded on Zoom, transcribed initially using Otter.ai, and revised by myself (KAL) afterwards. After our first conversation (59 min), I immersed myself joyfully in the transcripts, reliving our insights and laughter. From there, I conducted a thematic analysis, organizing conversation topics and quotes by key themes. I shared transcripts, notes, comments, themes, and further questions with Bobbi Rose over our shared Google Drive. After going through the questions and transcripts, we decided we needed to meet again. One conversation was a 15-min check in, and one was 2 h and 45 min, meandering through a catch up of our lives and the topics of this paper. The conversations were beautiful, joyful, and insightful to read and listen to again—full of laughter, tears, teasing, distractions, ideas, and realizations. I categorized sections of these conversations as well and quilted them together to form one long conversation. The resulting piece is a mix of three conversations, organized thematically for the reader—however, all elements overlap and there will be crossover between sections.

Our relationships with each other and within the industry is what allowed us to have this conversation and to reach the insights we do. We both work intimately in the industry and share multiple connections, friends, and business partnerships in this space. While there is much to critique, and we attempt to do so, we aim to do so while honoring those relationships. This is a challenging but necessary approach when using a relational framework.

In the same way, we decided not to critically analyze our conversation—we did not want to sever the words from the whole of the discussion. While this may dissatisfy many scholars, our hope is that this critical dialogue of Indigenous tourism from the perspectives of a Gwich'in owner and operator, land advocate, interpreter, and guide in conversation with her friend and colleague is valued as it is. We invite and welcome other scholars to dissect and critique what is written here—find inconsistencies, tropes, and other scholarly pieces of interest—but this is not our goal. We are friends, first and foremost. Following Indigenous methodologies, our relationship is paramount to the research.

By doing so, we are actively practicing a key theme that emerged from our conversation—presencing. This is Simpson's (2011) concept, and we intend to use it in the way that she does, as one element of Indigenous resurgence movements which ultimately move to “create more life, propel life, nurture life, motion, presence, and emergence” (p. 143). There is much power in the presence of Indigenous guides on their own lands. It is the starting point to move forward toward land, governance, language, body, and knowledge sovereignty. In writing this paper as a dialogue, we aim to presence embodied Indigenous thought and voice in tourism literature.

This paper will outline the ways that Bobbi Rose's company and ambitions work to increase Indigenous presence. We have separated the conversation into the ways in which presencing impacts the land; Indigenous youth and guides; non-Indigenous clients and guides; tourism companies, and the tourism industry as a whole. We end with reflecting on how this presence will impact the future of tourism.

Results and discussion through dialogue: the impacts of Indigenous presence

As stated in our earlier sections, each of our three conversations started with informal checking in and catching up. In the first, after our laughter subsided (she is very funny), Bobbi Rose (BRK) focused our conversation clearly with a direction that guides the themes of this dialogue:

BRK: Okay, before we start this, let's think about how we want people to feel when they're done reading this article. For me—I want people at the end of the day to feel good about reaching out to Indigenous tourism businesses, or businesses that are doing good, meaningful work, and working with them. What is Indigenous tourism? And what did it look like? And what could it look like? What does that mean for Canada? Or even the world? When we are thinking about Indigenous businesses, there is so much that can be done. But at the same time, it's looking at—how do we do business in a different way? How do we build relationships and give back?

Impacts on the land: “The land wants us here” (BRK)

KAL: I guess it makes sense that you want to focus on relationships and giving back, as the seed for DZA started with your advocacy for the Peel Watershed, which inspired a river trip and your advocacy organization Youth of the Peel.

BRK: Yah, exactly. We started Youth of the Peel after a 17-day CPAWS (Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society) river trip in 2015 on the Wind River (see Figure 1). There were five youths paddling together with a couple of guides from their organization. Prior to that river trip, for a really big part of my life, I was doing a lot of work around advocacy and protection of the Peel Watershed (see Figure 1). I remember one of the youth on that trip didn't grow up in the North but was trying to get back to their land and ancestral connections. We would stay up all hours of the night by the river talking about our dreams and our goals, and then one day, we were all on top of this mountain and I raised the question—why does my grandfather think that this is a once in a lifetime trip? It shouldn't be.

Now, we went with just the bare minimum—it was a pretty low budget trip. I started growing close to one of the guides who had been guiding for 20 years in Ontario. I really liked what she was doing and how she was doing it out there because I was really nervous to be traveling without my own people. I knew that learning from her would be a good idea and I spent a lot of time with her on the river. By the time we were done the trip, a few youth who were on that trip created Youth of the Peel.

Youth of the Peel was a non-profit organization that we established in the fall of that year following that trip. When we gathered and were thinking about what we want to see in the future—we just kept coming back to river trips. By that next summer, we hosted our first river trip. Our main goal was to get more youth out on the land and remove the barriers that hold them back from going to these areas. I was just looking at our old documents the other day and—oh my god we were so young! On the trip, we gave the youth space to form their own thoughts and have their own questions at the beginning. In the middle of the trip, we talked about what the future could look like, and at the end, we were setting goals for each of us to think about what we were going to do in our own futures and for the land.

One thing we were clear about though—we didn't ever want to influence young minds to think that they had to protect areas if they don't have that interest. We didn't want them to feel that just because they're coming on river trips with us they had to become environmental monitors or become spokespeople—because we all got pushed into that. We just wanted them to share their experiences and stories from their time on the river.

Not too long after that, I moved to the Yukon and started attending tourism events as a speaker. I found tourism in the Yukon to be so different than other places in Canada—and I just fell in love with it. I've been involved in tourism for as long as I can remember—my grandfather ran tourism operations on our campground outside of Fort McPherson (see Figure 1) since I was a kid. So I already knew the history and some parts of tourism here in the north. But I didn't know anything about river guiding. I decided to learn more about guiding because on our trips, I felt like some of our non-Indigenous guides weren't being appropriate toward Indigenous people, or they were stereotyping us. Once I got into the river guiding world, I came to realize lots of things, like—why aren't there more women here? Or why are we not being held up the same way the men are?

After those experiences in the tourism industry and on the river, I felt I didn't want to just go on river trips, I wanted to be a river guide. I just set my heart out to become a river guide, and I did. Now here I am.

KAL: It's so interesting that this all starts with an advocacy group to protect the Peel Watershed, which eventually moves into getting on the river that everyone is working so hard to protect. Then you recognize that Indigenous guides and mentors are key to connecting Indigenous youth to the land, and work on building that capacity. By getting the youth on the land, you build those relationships and you actually get to the root of land protection and advocacy.

BRK: Yes, and it's not really advocacy but at the end of the day I could say that it is. It is because if I'm able to bring people to those places down river, whether they're Indigenous or not, it is important. Youth of the Peel just taught us what we needed to do and where we needed to go.

KAL: It's so meaningful, to be protecting an area for so long, and then to actually be on and traveling with it.

BRK: Yes—it's so beautiful to be talking about a river your whole life and learning about all these stories, places, adventures or just life on the land. Then to be able to go on the river—you're like, damn, this is what we are talking about! I was talking earlier about me and my grandfather standing on top of a mountain, and we were talking about these different places that he traveled, like Viniidinlaii (a place where water meets), which is a place where people would gather. He's been up on the Ogilvie River (see Figure 1) and so many different places on the Peel, and I learned all that. It was all in my mind, and I remembered and visualized that while we were traveling around. Still, though, it was just all stories.

But when I saw it, I saw it through his eyes, and I felt that love. I always wondered why he spoke about these places as if they were family members. I now understood and feel what he means or what he felt. I understand how he felt when he was speaking about it, because the place just feels like home. You feel comfortable—it's just beautiful. It was so powerful, being able to connect those pieces, the stories, and my grandfather and me and the land all together. As I was traveling down the river, I thought—damn—this place really needs to be protected. It brings people closer together too. Three or four different times, I had youth who traveled with me whose grandparents had shared stories with me of their travels in those areas. So it's really cool to be able to say, this place reminds me of your grandma.

And now that I know these places, it's a connection and relationship. One thing that I encourage the youth that I work with is that you don't have to be going to school or taking a program to learn about who you are, or where you come from, or how research is done. The people—our people—who used to do this live life out on the land. And there was a gap where we lost that connection because of all the shit that happened to us. And now, our people are going back. It's pretty amazing to be a part of that. The land wants us home too.

KAL: Yah, and I think you are highlighting here the importance of having a guide that not only knows how to safely navigate the river, who knows the land and the stories, but also the people. Imagine how different it would be for that youth if you weren't the guide. You have those deep connections, not only to the place, but also to all the people who live in or have traveled through there, so you can pull those connections out for the youth. What a massive difference to have you vs. the typical guides who do not have those deep familial connections to the rivers they lead. For example, myself—I've also flown up from Southern Ontario to guide rivers I had no relationship with. We're asked to read books by white male “explorers” and complete interpretation certifications about flora and fauna—but not information about the politics of that land, the dispossession of the land, the fact that the white explorer had access to that land because of Indigenous dispossession, and the fact that Indigenous people continue to live, travel, and protect the land. Things are shifting, obviously, but some of those ideas are still deeply embedded. I think your influence has made a big difference. But when people aren't connected to the area, these all becomes a series of someone's disconnected stories. There is so much that we're missing. And in missing that, we perpetuate this romantic idea of the “wilderness” and the land as a backdrop to a human experience as opposed to an agent in that experience. When someone who has those deep connections like you guides the river, it's so different for everyone there.

BRK: It's more about having an understanding of the connections between who you are and where you come from with different places and the stories and history they share.

KAL: So in a way the Peel Watershed benefits from you being on the Peel, right? You know, you do say: “You can't protect what you don't love” right on your website, Bobbi Rose.

BRK: [laughter] Ya! Damn. Just gonna be a deadly Elder [laughter]!

KAL: Oh, I know it. In another way—you can't protect an area if you're not there. I think about this for you in the Peel Watershed—you are training a whole bunch of youth to have the skills to travel down these rivers and monitor what is happening on them—this way, they'll be able to ask questions and watch changes as they happen. Are there new developments? Who else is traveling there and why? Long term, in the tourism industry in particular, it means that you and your guides are framing the narrative of the place for the guests. You can decide what to share about the place. You can decide and frame how people see the place, themselves, and their relationship to it. This is really different than being an Indigenous guide for another organization where you have to follow their narrative. In some cases, tourists and visitors have been sold a completely different messaging of the place, which makes it harder to come in and guide and share the perspective you have. When it's your own company, you get to frame it the way you want from the beginning—that this is first and foremost Indigenous land and that the people are still here. That it is not a “wilderness” but is a home where people lived and continue to live. And that you are actively working to represence those spaces.

Impacts on Indigenous guides: camaraderie, care, support

BRK: Yah, it's true. One of the other reasons why I wanted to start training guides is because I know when I started guiding, it was really hard. I felt really alone in the industry as an Indigenous person. It's amazing how mistreated I was as a new guide in the tourism industry when I started compared to now. I also know other Indigenous people who worked for other companies, and they just weren't treated respectfully. I felt like a lot of companies wanted you to work for little to nothing. And then if you're Indigenous, you feel kind of tokenized because these companies don't really get to know who you are. Like, one trip I was on, I brought some non-Indigenous guides to a couple of sacred places and halfway through the trip, I overheard them talking and saying that it'd be cool if they could run leadership trips for business owners, or whatever, and take them there too. It made me feel really sad because I'm showing them these places and there's a story behind it. I'm talking about our families. After that, I told them I don't feel safe having you in our circles because you're taking information from us. Anyway—I don't think I took you there, did I? I don't take anyone to that spot anymore.

KAL: No, you didn't. It makes so much sense. There is something really important here. Indigenous guides present on the land challenges the colonial myth of terra nullius and the open frontier as devoid of humans. Indigenous presence is a constant reminder that the settler-colonial state's efforts at Indigenous erasure failed. At the same time, there is also a risk of harm in these situations. And actually if a company's efforts toward increasing Indigenous presence does more harm to the guides by having one isolated Indigenous guide who is likely experiencing micro or overt aggressions of racism as you shared, they aren't actually helping at all. Companies need to shift the entire culture of their team lest their efforts cause further harm. If they do not, it is the Indigenous guide that is bearing the emotional and spiritual brunt of that.

BRK: Right. And all that happened before I was a guide. It really motivated me to become a guide. I think DZA came from many different places. But ultimately, I just wanted a place for our people in the north or in Canada to be able to know a company or a guide who they could go out on the land with in a safe way. To get into their own backyards and get to know it on a deeper level.

KAL: Right, and that makes me wonder—what actually is a “guide”? Who gets to be one? Who doesn't? And why?

BRK: Yah—I realized that I grew up out on the land with my family and community. We traveled in all seasons, traveled for multiple days, all over Gwich'in Country. We learned from the best people who have an understanding of and connection to the land. I knew if I could put my trust into myself, I could become a river guide. I just needed the skills and knowledge to get into the industry. After so many trips on the river as a participant and youth leader, watching those guides I thought—man—if they can do this, I can do this. And—here I am.

When I launched my business, it was a big thing for everybody here in the north. A lot of people were excited. Everybody—even across Canada. Now, I'm traveling all over speaking because people are interested in hearing me talk more about my journey, adventures, and what it took to get where I am now. So funny, because half the time, I was just going with the flow—the land made me do it.

I wouldn't have started my business at all though, without the guidance of Elders from communities like Mayo, Dawson, Old Crow, and McPherson. The Peel Watershed community really helped support me to move forward. Some non-Indigenous people who've been in the industry for a long time really did not like it. However, just being a fairly new guide in the industry and being new to starting and running a business, it's still nonsense when you hear people say shit. They would say things like— “you can't run a business”or “do you know how hard it is?” and— “you can't run that river”. Even last year, I shared that I might paddle this one river with an all-female guide team, and the person said, “those women can't run that river”. So, a lot of people say we can't do this because we haven't been in the industry for as long as them.

KAL: Yah. I can see how that is so lonely and frustrating.

BRK: Yah, I just think that being able to know that there are other Indigenous guides in Canada is super beautiful and that we need to come together and talk about what we have learned, how we can be better, and how we can be stronger. I think as Indigenous guides we should come together and travel each other's areas and rivers. I think of the next person we are able to help support and empower to help their dreams come true. I think in this world we're in, if we stick together and lift each other up, encouraging everyone's own wisdom and knowledge, I think it'll change the tourism industry. The way that some companies still run—I don't think that's the way anymore. Working and partnering together is so important. Now I'm going on a shit load of years since I've been guiding, I always ask myself, how can I Indigenize these trips?

Impacts on Indigenous youth: community, belonging, confidence, and connections to land and water

KAL: What does that mean, to “Indigenize” a trip? Who is it for, and what are the impacts of it? Is that inherent to Indigenous tourism, or do you have to think consciously or plan consciously for it? What impact does this have on the youth? Who can do Indigenous tourism, and who is it for?

BRK: I think about a lot of different things when I think about Indigenous tourism. What does it mean for Indigenous operators? What does it mean to have an authentic Indigenous tourism business when sometimes it doesn't align with our values or isn't involved in community?

KAL: Sometimes I wonder if non-Indigenous companies focus on Indigenous youth and guides with intentions toward resurgence, or if it's because there are more grant dollars and public interest, so a greater opportunity to make money. Perhaps that's too cynical—but I do really question those intentions. But maybe it doesn't really matter because the result in the end is more Indigenous youth and guides on the river.

BRK: Yah, I think a lot of companies are trying to get more Indigenous youth on the land which is great. Because, you know, more youth out on the water or out on the land is key. When I think about Indigenous trips or Indigenous led trips, it is to have someone there who understands the land, the people, the language, the stories, history, traditional and cultural knowledge, and understands how to meet youth or people where they are at.

Indigenous youth want to do trips, but half the Indigenous youth that sign up on trips have never been on trips or community expeditions with their people. It's different today whereas I grew up with that. But, compared to when I first started doing river trips and now—they're so different. I do try to bring on Indigenous guides and make sure some of our food, gear or services are provided by local or Indigenous businesses or organizations items. We always want to support other Indigenous or local businesses, community members, and friends.

I think when people think of Indigenous led trips, especially when it's for our own people, it can mean a lot of things, depending on the First Nations and peoples. I never really heard of Indigenous trips until a few years ago, when I signed up and I got there. There were no Indigenous instructors or support for the program, but there were Indigenous youth. It was still great—I was just excited to meet more people in that area.

Sometime Indigenous trips can look like gathering and living in a special area for a period of time, either working with fish or caribou, moose, trapping, picking medicine, beading, learning, or hauling wood etc. Those trips were always so fun for me, because we could be 20 miles up or 50 miles down the Peel, or into the mountains or lakes. We get to work with Elders who sometimes have mobility issues. On other trips, we would be with a bunch of people always moving, on the go, traveling long days by snowmobile, setting up wall tents, keeping a look out for future meals, trapping and always learning quickly. Usually on these trips, the majority of the people are Indigenous peoples and are usually on a flexible schedule. One example I always think about is when it would rain, my grandparents would ask us what we would want to do inside that day.

Somewhere over the years, I fell in love with the expedition style river trips. Maybe because I miss traveling around like how we used too. My mentors or Elders are all older or gone now. They made me work hard. They never treated me any differently. I still had to get up early, learn how to do things quickly, and use what we had around us. It was like school but not school. So, sometimes, I think Indigenous youth or Indigenous people want to chill and get to know the land for a period of time, which we can't do on expedition style river trips too much because we have to move every day to be on schedule for our flight. I understand why they want to stay because I felt like that when I did my first river trip. I felt like—oh my god, I could stay here forever.

KL: What do you think that is? What is that feeling? What is that pull?

BRK: Community, good time, space, feeling of comfort, no worries. They feel safe and they can just be themselves. It's that feeling of community. After a couple of days on a river trip, it can feel like we've known each other for a long time. I think back to some youth on Indigenous led trips and how meaningful it is for them. Every day, they were so thankful to be learning, growing stronger, and knowing everything will be okay.

Really, as long as people are traveling the land in a safe way, I think that's what matters. And I think that youth and community need more education around these river trips and what people actually do on them. Some of my friends don't really know what we do on river trips as guides. This is something that came up from my family and a community I work with. They wanted to book a trip. They told me—let us know when so we can get our bear monitor. And I'm like—oh, that's us [laughter]. Then they ask what about cooking? I say—oh that's us. Then they ask, okay what about guiding then? I say—oh that's us too! We do everything! It's kind of crazy when you think about it. But that's our job as guides, we take care of people, and I love it. So, maybe people need more preparation about how we travel on these river trips, and how we prepare ourselves. Also, how those skills we learn on the river can help us beyond the river.

I don't like saying it out like this, but some young people get everything done for them. On some river trips, youth learn that from the beginning and their body and mind is not used to being outdoors all the time. Halfway through the trips, I see more youth become well-aware of the strength, power, knowledge, and wisdom that they have. They follow their hearts and do what they feel is right. They look after themselves and others. And at the same time, they're getting to know the river and the place.

Connections to land and water

BRK: At the end of the day, we're creating a beautiful space for people to gather, travel and feel safe. And for me as a Teetl'it guide, to have fun, get paid, and get to know my own home—it's a gift and honor. My Jijuu (my grandmother), my Jijii (my grandfather) and my Elders grew up out there. It was a part of their life. When my grandfather used to talk about it, it just sounded like it was a dream, like it happened so long ago. But actually, that wasn't even 60 years ago. My Jijii, when he used to talk about the Peel Watershed, he made it feel so far away, yet it's just right there. We just didn't have the right people to help guide us like we used to. Now I have a business doing river or land-based trips. It's crazy.

KAL: Why river trips? What led you to that?

BRK: There was something about my first white water river trip that made me really love the way that water moved, the way that it changes and how we can work with it, how powerful yet beautiful it is. When I'm on the water, I like being able to read it and see how it's talking. As well, just knowing that my grandparents went down these rivers before is something else. Back in 2015, I knew that if I wanted to keep going into the Peel watershed for the rest of my life, I would have to get used to water because I was low-key scared of it. It's important to remember that some youth and people have trauma around water, and rebuilding a relationship to it is important. I love seeing how river trips can change people. I also love how water is a teaching tool. Some river expeditions are hard and can challenge a lot of people. I think that's what people need in today's world. I feel like when I grew up, we had to go out on the land. It was challenging and it helped me be who I am.

KAL: So it's like you said before—it's not just about getting youth on the river, but ensuring they have a mentor out there. They need community with each other on the river. It's actually so strange to run Indigenous youth trips without Indigenous mentors.

BRK: Yeah, I think that's kind of weird. Some companies have that Indigenous guide training and it pisses me off. Some have been running this training for years—but if your training is working, then where the heck are your Indigenous guides and mentors? But that flows back to why I wanted to do river trips in the North because I wanted our people to be taken care of on the river and to be understood and feel safe and comfortable and feel like they belong.

KAL: Yah, that's a really good point and reflection: If your company keeps running Indigenous programming or Indigenous guide training programming and none of the people you are leading or guiding become the mentors or guides themselves—then something in that structure isn't working. There needs to be some accountability, especially for groups and organizations that continue to be funded to do that, in the name of “Indigenization”, “decolonization”, and “reconciliation”. These places need to take a deep look and assess whether or not what they are doing is actually working toward what they say it is. I see what you're doing as telling youth: “Hey, you're capable of taking care of yourself here. You have a right to be here, this is your land. Your grandparents traveled these rivers. This is your birthright. This is your land. And here is how you can travel and take care of people out here. Here's how you can take care of yourself. Here's how you can manage, avoid, and respond to racist comments and people. Here's how you communicate with and take care of the land.” I wonder if other companies professing to bring on more Indigenous guides are saying that too, or whether they're thinking: “Here is how you cook our menu, here is how you cater to our clients”. It's nowhere near the same kind of presencing, or “Indigenizing”—it's not resurgent at all.

BRK: Yeah, I don't really know. I know when I first started guiding, I wasn't supported like that. As time goes on, things are changing though, thank goodness. A couple of the guides I trained last year who are young and started working trips without me this year really got to practice connecting to the land on their own with all the things they've learned through me and mentors who have worked with them. When I think about the future goals of DZA—we're training and lifting up other Indigenous youth from around the North to learn what it means to travel the land, and for our guests to feel at home. River guiding is—I know you know—but it's so different from anything else that we do in our communities or outside of our communities. But it creates a community in and of itself that is full of love, bravery, unknown-ness, and known-ness. I'm just hoping I can build a community of young people who have these places in common that they can talk about it. I hope that when they talk about it, they fill up with life and stories and they're able to share that with other people. On top of that, they'll have the skills and confidence to take people down the river. I don't care if they work with me or if they work with other people, as long as they're out there and they're following their heart, that will make me happy. I hope that they're able to feel good about speaking up and making decisions for themselves and others. That they're able to share stories using their strong voice because they understand, because they heard it from their mentors and teachers.

KAL: Right—and when they see you in that role, they see themselves in that. They can see a different pathway than the typical expensive summer camp to low paying guide job to owning a company. You've paved a different pathway there and your presence in the industry proves it is possible. It makes me think of what we mean when say “sustainable tourism”. Because I think—sustaining what? Actually, we don't really want the status quo of the tourism industry to be sustained. We're trying to say it needs to be Indigenous led. Tourism needs to stop benefiting from Indigenous land without centering Indigenous peoples. At the same time, we can think of “sustainable tourism” as meaning it can keep going or growing. In a way, your company and your vision for the protection of rivers and land is sustainable through youth. Training youth is central to that. It's a perfect example last summer that you got to see some youth carry on and share their knowledge without you.

BRK: Yah. It was crazy. I was so proud.

Impacts on non-Indigenous guides and tourists: deep learning and self-reflection

BRK: Another thing too, non-Indigenous people want these kinds of trips as well because they want the stories and everything else in between. They want to feel welcomed on the land they live and travel on. They want to hear your relationship with and to the land and how it helped you.

People have been really excited. I've been really lucky to be able to be in canoes with some people who are really great and ask really good questions. It was really cool last year when, I was on a trip with one of my non-Indigenous friends and got to bring them to a special place on the Wind River. They sat there and just started crying. I knew them for a long time, but I've never been on a river trip with them. I was just telling them about this mountain and they started crying.

It's not just non-Indigenous clients, it's non-Indigenous guides too. They leave these trips they've guided with Indigenous youth learning about our lives up here in the North and feeling like they've never learnt so much in their lives. I've been getting some emails from some non-Indigenous people applying to work with DZA because they want to do meaningful trips. It makes me question—why do they want to apply with my company compared to the maybe 30 other companies that are in the North? I think it's because people want to be a part of something bigger than just trips. I mean, going down beautiful rivers is fricken amazing. And they are beautiful journeys, for sure. But when you're traveling with Indigenous people, it's so different because we're showcasing our home, and what it means to us.

KAL: Yah, I'm not surprised at all. I teach a whole bunch of aspiring guides at Lakehead University right now. And in our classes, they're learning all sorts of things—they're learning about the role of Parks in the colonial project and the colonial roots of tourism and outdoor recreation and education. They're learning about how this is ongoing. We're looking at websites and marketing material of guiding companies, environmental protection organizations, and outdoor education and adventure tourism programs (including our own) to critically analyze where they perpetuate this colonial myth of “wilderness”, the “frontier”, “discovery”, and narratives of untouched, unpeopled, pristine virgin land. We also learn about all the communities, organizations, partnerships, and individuals who are challenging these narratives. Many come away from these classes questioning where they want to put their energy and which companies they want to work for. Many want to work for organizations, companies, and individuals who are challenging these colonial ideas and moving toward a more just world for humans, more-than-humans, and the world we all share. That's what I see young guides, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, are looking for as they enter the workforce. So actually, if the tourism industry wants to keep attracting batches of critically minded guides, they also need to think critically about their role in the colonial project and how they can challenge that.

Another thing, these youth aren't going to work for pennies anymore like I remember doing when I started because I loved it. The young people are refusing to do that. They want to be paid what they're worth based on the labor they pour in, they want to do work they believe in, and they're asking questions. And so I think if companies don't figure out how to partner with companies like yours, I don't think they'll find many guides to work for them. I don't think organizations that have no idea where they are or the history or politics of that land are going to last much longer, to be honest.

BRK: Yeah, there are lots of companies who have little to no information about the North. Sometimes they just send guides up here and put them on trips without an understanding of the land they are on. Remember last year, we did that talk for my business partner's guides? After doing the talk, a few of the guides reached out and asked, “Hey, I travel this river a lot, it is like a family member. I want to learn more about it. I want to learn how to say its name in the language. I want to learn the history of the area and the people.” So beautiful, and I just really appreciate people going out of their way like that.

KAL: I see what you're saying for sure—but I don't think that is people “going out of their way.” I know it's rare but it is also basic and bare minimum critical engagement—or it should be seen that way. At the same time, so many businesses don't engage at all. You have a good relationship with your business partner though.

Impacts on other tourist operators: authentic partnership and growth

BRK: Yes, partnering is so important. Partnering up with other like-minded peoples and building a relationship where you have a combined goal and vision is key. As well, giving each other the freedom to lead the way they want to. At the beginning, we said we don't see too many Indigenous-owned river guiding companies because things are too expensive and especially in the North, which is like 10 times more expensive. Most river guiding businesses start trips on Indigenous land, so there's always room for partnerships—work needs to be done on both ends.

There are many ways we can all learn together and grow together. I work and am business partners with my friend who owns a canoe and raft guiding company in the North. Before officially working with him, I interviewed other companies and decided his was the one that I felt best in. I felt I was really going to learn and grow from him and be able to be who I am by being me and not worrying about stepping on somebody's toes or doing something wrong and feeling bad about it. We really created that space and relationship. Last year, we ran a fully funded trip for Indigenous youth, which was a partnership between DZA, his business, and a local youth organization. My business partner put money toward it, and I found lots of other companies to help sponsor it too.

When we work together like this, everyone is learning—I'm not the only one learning, my business partner is too—both in business and what it means to live in the North and how to do things in the North. It's really helping to change what tourism looks like here.

KAL: Right, and partnerships like this are so important and obviously so meaningful. At the same time, in many ways, they are long overdue.

BRK: Yeah, and that's another subject. It reminds me of when people do land acknowledgments, but don't give back to the people whose land they're on—they could help support or offer training or trips for locals. There are many things you could do, you could hire someone to shuttle people from A to B or include community members in local tours or give back to organizations in one way or another. I just think that there's room to give back in the tourism industry. And if not, then I'll make room. Some people in this industry have been here for a really long time. They made a name for themselves. They made their money off Indigenous land, but they're not giving back.

KAL: Right—and if they do partner—is this an authentic reciprocal relationship, or is this just good PR for companies?

BRK: Oh yah, that's there too. After starting to work for my friend here, I was up on their website and started getting so many emails of people wanting me to guide for them, wanting to hire me, but just for a fraction of the price. I set my standard high, early and that was really smart. So there are still things to work out with tourism in the North, but in the end we do need tourism because it helps our economy. We just need to do it better as an industry.

Impacts on the tourism industry: from taking to sharing

BRK: I think what needs to get out of the way is people's egos. I don't think that tourism operators here in the North should be fighting against each other or competing for guests. I think that there's always room to share, and always room to teach and learn. I also think hiring locals is the key. I hate when companies are based out of somewhere else—last year I was in Yellowknife and ran into this company that is based out of Calgary and they're coming up here in the winter, charging people thousands and thousands of dollars to come tour Yellowknife and then taking their money back to Calgary again. It's not staying within the communities. It's not going back into our northern economy like it should.

KAL: It's taking. It's taking again.

BRK: Right, so how do we shift that? We have to think about what tourism is. More specifically, what is Indigenous tourism? It's not only guided trips or tours. It's storytelling and art. I just want to see change. I think the reason we don't have more tourism businesses in the North is because people don't know where or how to start sometimes. I want people to feel empowered about the way that Indigenous people are stepping into tourism and making it meaningful by bringing in community and helping to train other people to be in these spaces. It's more than tourism. When I go out on the land and when I'm guiding, I feel more connected to my ancestors and my people and to the land than ever. It helps heal me in a different way. I think it also awakens us and reminds us that we're the ancestors when we're out on the land, and that's where all the stories come from and can be shared. That's how we share that with others to make better choices for our world. I want to make more of a change. I feel the land is changing so rapidly—and it's hard to see that. I feel like tourism is one way of sharing information with other people to be more aware.

Impacts on the future

BRK: Last year, after the IYRGTP, it was the first time in all the years that I traveled to Peel Watershed that I didn't cry. I didn't cry because I knew that we trained five youth to know the river and understand it and get to know each other. Those five grew so much and their confidence was built—it was pretty beautiful. And you know, if I'm able to do that, maybe like 10 more times, 15 more times, 25 more times until somebody else takes over, I'll be super thankful.

My Jijii always told me when I was younger, you know, whether it was through hauling wood or going fishing or anything that he was trying to teach me (while I was probably being a little shithead): “We're getting you ready. We're getting you ready.” I never knew what that meant until I trained some youth. He was trying to get me ready for the future and help build me up to be able to make the best decisions I could for myself. That's what I want to do for the youth on our trips too.

As an Indigenous person, we are the land, the water and everything in between. You know—we are thinking about our next generations. If we are not taking care of the land today or tomorrow, what are we leaving for our next generations? The tourism industry has been getting away with a lot over the last 150 years, but I think it's Indigenous tourism that is going to lead tourism, and it's going to be the way. Other tourism companies better learn and get on board or else they're going to be left behind. I don't mean to say that like that—it may seem like I'm saying it in a bad way, but [sigh]—

KAL: I think you're right.

BRK: Yeah. We're going back home and we're going to take it back over and our people are getting stronger. Our people are getting healthier. Our people are getting back into these areas or these positions that our people once had. My great-great-great-grandfather was a river guide too. And you know, a lot of Indigenous people all over North America or Turtle Island have been guides because people who came here as visitors didn't know the land, so we guided them. We were hired to do that. We were the first guides of this area because we knew it. And we're going to be the last guides because we still know it.

Conclusions: Indigenous presencing through tourism

“It's tourism, but it's more than tourism, it's also spiritual. I'm more connected to my ancestors out there. I feel my ancestors out there.”

Bobbi Rose Koe

Indigenous presence is imperative for sustainable tourism to call itself so. Bobbi Rose's experiences as participant, guide, and tourist operator in the industry points to the significance and impact of Indigenous presencing on: the land, Indigenous guides, Indigenous youth, non-Indigenous guides and guests, other tourist operations, and the industry in general. We are also able to see a vision for the future, pointing to ways that this kind of tourism, which is “more than tourism” (BRK), can have impacts that go far beyond socio-economic and ecological sustainability. This conversation highlights how this presence challenges the myth of terra nullius, which the concept of “wilderness” and “adventure tourism” is marketed on and intimately tied to. By challenging this myth, she exposes the colonial, capitalist, heteropatriarchal roots of the tourism industry, and in this way, demonstrates how profoundly Indigenous tourism can, if nurtured, challenge and build narratives and relationships that reach the root of the wellbeing of waters and lands. It can be transformative on so many levels.

As this paper showed, the potential benefits of this presence cascade to all elements and participants in the tourism industry. It creates safe and nurturing spaces for Indigenous youth and guides to build relationships with themselves, each other, and the land, which in turn can inspire more Indigenous guides and potentially tourism operators in the future. It has the potential to influence non-Indigenous owners and operators, guides, and clients to rethink their own relationships to the land. DZA's business partnerships demonstrate an example of how mutual learning and benefit can be shared in the industry—instead of competing, Bobbi Rose urges companies to work together toward common goals and collaborative growth and learning. She also points to the direction forward for the tourism industry in general by recognizing the important role it plays in the north, as well as pointing to problematic elements, such as the way that economic benefits are distributed.

Bobbi Rose highlights the potential connection between land defense, protection, and advocacy with adventure tourism and guiding. Indeed, it was her motivation for starting a tourism business in the first place. Yet, she cautions guides, tourist operators, and the industry in general that shallow attempts at “Indigenizing” can cause more harm. In other conversations reflecting on these discussions, we have talked about the potential for Bobbi Rose and DZA to develop mandatory certification for operators and guides to learn about the historical and current politics and cultures of the land they travel through and with—the land their companies directly profit from access to.

Lastly, this conversation pointed us to the necessity for multiple perspectives in the conversation. For example, hearing from the youth involved in the Indigenous Youth Guide Training Program, youth who have been clients on trips, non-Indigenous guides and clients, non-Indigenous partners and tourist operators, as well as other Indigenous-owned tourism operators. We also excitedly discussed the idea of bringing multiple Indigenous guides together to talk about experiences in this industry across Turtle Island. While this paper highlighted key success, challenges, and opportunities from the perspective of Bobbi Rose, it is just one perspective and experience amongst many across the industry. More perspectives are needed to get a full picture on Indigenous tourism and its impacts to multiple actors (Calvin et al., 2024). We hope that this conversation serves as another piece of literature centring Indigenous voices in tourism research and that many more follow. Through this conversation about Indigenous presencing in the industry, we have presenced Indigenous voices in tourism literature. We hope that this encourages more Indigenous tourist operators, entrepreneurs, and guides to voice their experiences so the field is less about Indigenous tourism and more from Indigenous tourism.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

BRK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. KAL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors thank Lakehead University's SRC Open Access Publication Fund for financially supporting the publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

BRK is founder and owner of Dinjii Zhuh Adventures.

KAL declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Archibald, J., Xiiem, Q. Q., Lee-Morgan, J. B. J., and De Santolo, J. (eds.). (2019). Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology. Zed Books Ltd.

Bessarab, D., and Ng'andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in indigenous research. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 3, 37–50. doi: 10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

Buckley, R. (2007). Adventure tourism products: price, duration, size, skill, remoteness. Tour. Manage. 28, 1428–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.12.003

Calvin, S., Young, T., Hook, M., Nielsen, N., and Wilson, E. (2024). Are our voices now heard? Reflections on indigenous tourism research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 59, 81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2024.03.010

Carr, A., Ruhanen, L., and Whitford, M. (2016). Indigenous peoples and tourism: the challenges and opportunities for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 24, 1067–1079. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1206112

Cassel, H. S., and Maureira, T. M. (2017). Performing identity and culture in indigenous tourism – a study of indigenous communities in Québec, Canada. J. Tour. Cult. Change 15, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2015.1125910

CBC News (2017). Supreme Court Rules in Favour of Yukon First Nations in Peel Watershed Dispute. CBC. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/peel-watershed-supreme-court-canada-decision-1.4426845#:~:text=The%20Supreme%20Court%20of%20Canada,proposed%20by%20an%20independent%20commission (accessed September 22, 2024).

Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness: or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environ. Hist. 1, 7–28.

de la Barre, S. (2013). Wilderness and cultural tour guides, place identity and sustainable tourism in remote areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 21, 825–844. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2012.737798

Erickson, B., and Krotz, S. W. (2021). The Politics of the Canoe. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press.

Everingham, P., Peters, A., and Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2021). The (im)possibilities of doing tourism otherwise: the case of settler colonial australia and the closure of the climb at Uluru. Ann. Tour. Res. 88:103178. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103178

Fortin, K. E., Hurst, C. E., and Grimwoodm, B. S. R. (2021). Land, settler identity, and tourism memories. Ann. Tour. Res. 91:103299. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103299

Graci, S., Maher, P. T., Peterson, B., Hardy, A., and Vaugeois, N. (2021). Thoughts from the think tank: lessons learned from the sustainable indigenous tourism symposium. J. Ecotour. 20, 189–197. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2019.1583754

Graci, S., and Rasmussen, Y. (2023). Indigenous Women in Northern Canada Creating Sustainable Livelihoods through Tourism. The Conversation. Available at: http://theconversation.com/indigenous-women-in-northern-canada-creating-sustainable-livelihoods-through-tourism-204451 (accessed March 29, 2024).

Hayden-Taylor, D. (2017). Searching for Winnetou. CBC Docs POV. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1.4493479 (accessed April 9, 2024).

Hsu, P.-H., and Nilep, C. (2015). Authenticity in indigenous tourism: the provider's perspective. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 8, 16–28. doi: 10.5204/ijcis.v8i2.124

Johnston, J. W., and Mason, C. W. (2021). Rethinking representation: shifting from a eurocentric lens to indigenous methods of sharing knowledge in Jasper National Park, Canada. J. Park Recreat. Admin. 39, 2–19. doi: 10.18666/JPRA-2020-10251

Kovach, M. (2005). “Emerging from the margins: indigenous methodologies,” in Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous and Anti-Oppressive Approaches, eds. L. A. Brown, and S. Strega (Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars' Press), 19–36.

Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Kovach, M. (2019). Indigenous Research Methodology through the Lens of Decolonization and Reconciliation. Edmonton, AB: Lecture, Grant McEwan College.

Lepage, M. (2008). Martha of the North. Available at: https://www.nfb.ca/film/martha_of_the_north/ (accessed April 1, 2024).

Mason, C. W., Carr, A., Vandermale, E., Snow, B., and Philipp, L. (2022). Rethinking the role of indigenous knowledge in sustainable mountain development and protected area management in Canada and Aotearoa/New Zealand. Mt. Res. Dev. 42, A1–9. doi: 10.1659/mrd.2022.00016

Murray, G., and Burrows, D. (2017). Understanding power in indigenous protected areas: the case of the Tla-o-Qui-Aht Tribal Parks. Hum. Ecol. Interdiscip. J. 45, 763–772. doi: 10.1007/s10745-017-9948-8

Newbery, L. (2012). Canoe pedagogy and colonial history: exploring contested space of outdoor environmental education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 17, 30–45.

Novotná, M., Kubíčková, H., and Kunc, J. (2024). Beyond the buzzwords: rethinking sustainability in adventure tourism through real travellers practices. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 46:100744. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2024.100744

Peters, A., and Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2012). De-marginalising tourism research: indigenous Australians As Tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 19, 76–84. doi: 10.1017/jht.2012.7