- 1Tourism Management Department, Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops, BC, Canada

- 2Tourism Management/Natural Resource Science Departments, Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops, BC, Canada

Rural and northern Indigenous communities across Canada are pursuing new Indigenous-led conservation partnerships with Crown governments as critical alternatives to Western conservation and extractive industries regimes. Colonial conservation policies and industrial development continue to displace Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral territories, with great consequences to land-based economies, food security, and knowledges. Indigenous-led conservation is an umbrella term used to describe a variety of initiatives that includes Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas. Indigenous communities lead the creation, management, and stewardship of these protected areas, which are guided by localized knowledge and priorities. This creates unique opportunities to build new and bolster existing tourism businesses with sustainable socio-economic, cultural, and environmental outcomes. Our research examines Indigenous-led conservation and tourism in the Dene/Métis community of Fort Providence, Northwest Territories, located adjacent to Canada's first official Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area, Edéhzhíe. Guided by Indigenous methodologies and collaborative approaches, this paper presents the analysis of 23 semi-structured interviews with Elders, knowledgeable land users, and community members. While tourism development in the community is currently limited, our results indicate that participants are hopeful about the contributions of Edéhzhíe and tourism to sustainable economies, cultural resurgence, and environmental stewardship in the surrounding communities. Participants demonstrate that Indigenous-led conservation and tourism have the potential to challenge existing colonial, capitalist land use regimes and foster Indigenous governance, reconciliatory processes, and environmental resiliency. Our findings can be used by other Indigenous communities to inform conservation and sustainable development goals related to regional tourism economies.

1 Introduction

Indigenous Peoples in Canada have experienced great disruptions and displacement with the imposition of colonial conservation regimes and tourism development in protected areas. Legacies of these impositions and exclusions continue to impact Indigenous communities' health and wellness, economies, cultural continuities, education, and food systems (Cruikshank, 2005; Snow, 2005; Sandlos, 2014). Indigenous Peoples have always refused and resisted some colonial conservation policies and continue to assert their rights and responsibilities to their territories in innovative ways. One example is through Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs), which represent a variety of structures and manifestations, but are characterized by Indigenous Peoples leading the creation, management, and stewardship of their ancestral territories (Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018). IPCAs go beyond existing Canadian protected area models by centering Indigenous Peoples' long-standing stewardship practices guided by localized knowledges, laws, and ceremony. They act as assertions of Indigenous governance and self-determination. These initiatives also create unique opportunities for Indigenous communities to build new and bolster existing economies, such as tourism, as they pursue sustainable development and environmental protection.

Pressured by Indigenous Peoples' political advocacy and resistance, and ongoing calls to action from international conservation and Indigenous rights movements, Canada's Federal Government has recently dedicated significant resources to support Indigenous communities develop IPCAs (Government of Canada, 2021b; Environment Climate Change Canada, 2023). Canada's support is grounded in their commitment to the United Nations (UN) to protect 30% of its lands and waters by 2030, and part of realizing and aligning their practices with new national reconciliation legislation created in 2021 (Government of Canada, 2021a; Environment Climate Change Canada, 2023). Many Indigenous Nations have declared IPCAs outside of Crown-recognized legal and policy systems. Others are pursuing partnerships with Crown governments to access this funding and co-designate IPCAs under Canadian designations. Since federal support was announced in 2018, only three IPCAs have been established through these partnerships. All are in remote northern regions of the country. Here, Indigenous communities widely experience challenges to access their lands and face disproportionate effects of climate change, which result in a myriad of socio-economic disparities (Council of Canadian Academies, 2014; Ford et al., 2020). The North also contains relatively unfragmented boreal and tundra ecosystems, has prevailing Indigenous land use policies and agreements, and is primarily under federal jurisdiction. These factors make for favorable conditions for IPCA development.

Protecting large tracts of land in the North through Indigenous-led conservation is vital for Canada's commitments to both conservation and reconciliation, and for Indigenous communities' self-determination and socio-economic resiliency. Northern areas hold significant ecological (e.g., habitat, carbon sequestration, biodiversity), cultural (e.g., food security, spiritual, educational), and economic importance both regionally and nationally (Coristine et al., 2018; Mason, 2018; Moola and Roth, 2019; Qikiqtani Inuit Association, 2022). Parks and protected areas also offer alternative and more environmentally and socio-economically sustainable industries to adjacent communities that can replace or augment persistent natural resource extraction industries in many rural and northern regions (Bennett et al., 2012; Lemelin et al., 2015). Tourism, such as wildlife viewing, nature-based experiences and accommodation, and fishing or hunting guiding, are economies that align with IPCAs and, where appropriate, part of many communities' IPCA development plans (Bhattacharyya et al., 2017; Youdelis et al., 2021; White-hińačačišt, 2022). Thaidene Nëné, a Łutsël K'é Dene First Nation IPCA located in the Northwest Territories (NT), is one prominent example where ecotourism development is closely aligned with IPCA goals and planning (Łutsël K'é First Nations, 2019).

Widespread federal support for Indigenous-led conservation is relatively new. The first IPCA created after Canada began endorsing this designation, Edéhzhíe, is located in the NT and was established in 2018 by the Dehcho First Nations (DFN) as an IPCA through Dehcho law and ceremony. The DFN and Government of Canada signed the Edéhzhíe Establishment Agreement to cooperatively manage the area as a National Wildlife Area, which was finalized in 2022 (Dehcho First Nations Government of Canada, 2018). Securing protections for this remote parcel of their ancestral territory has been part of the DFN's decades-long negotiations and assertion of self-governance and land rights (Watkins, 1977; Erasmus et al., 2003; Nuttall, 2010). Edéhzhíe is an important spiritual, cultural, and ecological area that sustains critical habitat and waterways that the DFN and neighboring Tłicho Nation depend on. These Nations have fought to protect the area from industrial development so it can continue to support their culture, food security, and economies [Dehcho First Nations Government of Canada, 2001; Dehcho First Nations v. Canada (Attorney General), 2012]. Tourism is one of the only permitted economic developments the DFN had originally planned for Edéhzhíe (The Dehcho Land Use Planning Committee, 2006), but tourism is not included in the more recent Edéhzhíe Establishment Agreement. Instead, this area is set aside to protect wildlife species and their habitat, to support Dehcho relationships to the land, and to contribute to reconciliation processes between the Crown and DFN (Dehcho First Nations Government of Canada, 2018).

There is very little research that examines community perspectives of how Indigenous-led conservation contributes to more environmentally and socio-economically sustainable tourism development through IPCAs. Guided by Indigenous methodologies, we examine the opportunities and challenges to tourism development in the communities surrounding Edéhzhíe. We also consider how tourism can contribute to DFN governance, Crown-DFN reconciliation, and environmental resiliency in the areas surrounding Edéhzhíe. Data for this research is based on semi-structured interviews with Elders, knowledgeable land users, and community members from the Dehcho Dene/Métis community of Fort Providence, located adjacent to Edéhzhíe. Participants share their optimism about the opportunities for Edéhzhíe to support tourism development, and how both can address current challenges in the community and contribute to long-term change. Our findings add to a body of literature that examines how Indigenous communities are navigating sustainable development through IPCAs and can be used by other communities and policymakers to inform further tourism and IPCA designations (Bhattacharyya et al., 2017; Łutsël K'é First Nations, 2019; Tran et al., 2020; Youdelis et al., 2021; Mason et al., 2022; White-hińačačišt, 2022).

1.1 Histories of early tourism development and park formation in Canada

It is important to highlight the problematic histories of tourism industries related to parks and protected areas in Canada to understand the importance of IPCAs in the country's evolving settler-colonial context. This history of park creation began in western Canada with the establishment of national parks in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, specifically in the Banff-Bow Valley, the home of the Nakoda and many other Indigenous Nations. With the arrival of Europeans to the valley in the late eighteenth century, Indigenous Peoples were forced to undergo a series of significant changes. Elite tourists were attracted to these regions as recreational experiences began to be offered (Mason, 2008). The Canadian Pacific Railway was built to facilitate this tourism industry and quickly became one of the world's largest travel companies by the turn of the twentieth century (Hart, 1983). From the 1880s until the middle of the twentieth century, the development of tourism economies in the Banff-Bow Valley initiated a dynamic period in the region's history (Mason, 2021). The 1887 formation of Rocky Mountains Park (which became Banff National Park in 1930) was a joint venture between the Canadian Federal Government and the Canadian Pacific Railway. It was Canada's first national park and was originally established as a means of generating railway tourism with few conservation objectives considered (Hart, 1983).

Indigenous communities, such as the Nakoda, were displaced from, and denied access to, their lands through the establishment of Banff and later Jasper (1907) National Parks. This was primarily because their subsistence practices (hunting, fishing, gathering) were in direct conflict with Euro-Canadian perspectives of “conservation” and the objectives of the emerging tourism industry (Mason, 2014). At this time, it was imperative to ensure that Indigenous subsistence practices did not interfere with the growing sport hunting and fishing tourism economies that initially attracted urban elite tourists to the region (Mason, 2021). The displacement of Indigenous Peoples from Banff caused considerable impacts in Nakoda communities, such as consequences for Nakoda-centered approaches to education, health, and cultural continuities, but also regional food security and land-based economies. Similar to many Indigenous communities across the country, Nakoda Peoples are still healing from the separation from their sacred territories and the cultural repression they endured (Mason, 2014).

Banff National Park was used as a model in the development of other parks throughout the twentieth century (McNamee, 1993). The histories of displacement, exclusion, and cultural repression that Banff facilitated in Indigenous communities were unfortunately replicated in many locations throughout the country (Cruikshank, 2005; Sandlos, 2007; Johnston and Mason, 2020). However, colonial frameworks are consistently being rethought by park managers across Canada and challenged by Indigenous Peoples.

1.2 The rise of Indigenous-led conservation in Canada: biodiversity protection and reconciliation

In direct response to these colonial histories, Indigenous Peoples continue to access their territories and pursue legal action in Canadian courts to uphold and better define their rights,1 challenge colonial conservation regimes, and assert their sovereignty and presence in protected areas (Goetze, 2005; Carroll, 2014; Sandlos, 2014; von der Porten, 2014; Johnston and Mason, 2020). From these and other interrelated Indigenous-led pressures, Crown conservation agencies have been forced to shift their structures and policies to better respect Indigenous rights (Devin and Doberstein, 2004; Armitage et al., 2011; Turner and Bitonti, 2011; Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018). This includes roles created for Indigenous Peoples, cooperative management agreements, and provisions in conservation legislation that protect aboriginal or treaty rights. These efforts have been important avenues for Indigenous Nations to secure more access and decision-making authority but are criticized for not going far enough to support Indigenous self-determination, and for remaining entrenched in capitalist economic systems which are inherently limiting (Nadasdy, 2007; Ruru, 2012; Bernauer and Roth, 2021; McGregor, 2021). IPCAs represent a move from these existing cooperative protected area management frameworks that tend to simply incorporate Indigenous knowledges, toward ones that center them and are led by Indigenous Peoples.

In addition to Indigenous leadership and actions, Canada's support for IPCAs has also been influenced by international calls to action to better respect and include Indigenous knowledges, practices, and rights in biodiversity protections (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2010, 2022). Despite enthusiastic commitments and action from signatory countries, global biodiversity rates continue to decline (Coristine et al., 2018; Visconti et al., 2019). In response to these failures, the UN's 2022 Conference of the Parties meeting finalized a new framework that built on their 2010 Aichi Targets and proposed steps to both sustainable development and conservation goals, while respecting and protecting Indigenous rights (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022). Importantly, this biodiversity framework emphasizes sustainable socio-economic development of communities alongside biodiversity protection. Canada's renewed commitments include lofty goals to protect 30% of the lands and waters by 2030 (Government of Canada, 2021c). This amounts to almost 10 million square kilometers.

Integral to Canada's commitment to area-based goals has been working with Indigenous leaders to develop strategies to move forward with both reconciliation and conservation. The Federal Government supported a group, named the Indigenous Circle of Experts, in the creation of a guiding report which introduced a framework for IPCAs and contains recommendations (aimed primarily at Crown governments) on how to proceed with Indigenous-led conservation (2018). The report includes a background and description of the various types of IPCAs and other area-based Indigenous-led conservation initiatives that have existed for millennia but have grown in recognition over the past four decades with diverse land use conflicts. Since 2017, the Federal Government has pledged to work collaboratively and in partnership with Indigenous Peoples and has dedicated billions of dollars to support their goals and Indigenous communities in IPCA development (Government of Canada, 2021a,b, 2023).

Current Western approaches to conservation and economic development practices in rural regions differ significantly from those inherent in IPCAs. IPCAs reflect Indigenous Peoples' more holistic socio-economic and ecologic relationships with the land which considers humans, including their economies, as part of a healthy environment (Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018). Crown conservation agencies often experience great barriers to enact conservation strategies in vast and rural protected areas throughout the country, but especially in northern and remote regions (Lemieux et al., 2018). Indigenous communities are often uniquely positioned in rural areas and have cultivated extensive, localized land-based experience, which allows them to facilitate and inform more efficient conservation practices (Artelle et al., 2019; Coastal First Nations Great Bear Initiative, 2022a; Reed et al., 2022a; Vogel et al., 2022). Examples from across the globe affirm that Indigenous-managed areas, including those in Canada, match or exceed conservation objectives compared to state-managed areas, specifically regarding biodiversity protection (Nepstad et al., 2006; Schleicher et al., 2017; Schuster et al., 2019). Furthermore, many Indigenous-managed protected areas involve economic developments that are complementary to traditional economies, provide long-term local employment opportunities, and support cultural and environmental resiliency (Plotkin, 2018; Qikiqtani Inuit Association, 2019; Coastal First Nations Great Bear Initiative, 2022b; Barkley Project Group, 2023).

Concurrent with Canada's biodiversity plan, a truth-telling and reconciliatory movement has been growing across the country, led by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), and supported by the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).2 Both the TRC and National Inquiry into MMIWG released final documents that call on Crown governments and Canadian institutions to implement the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Truth Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015b; National Inquiry into Missing Murdered Indigenous Women Girls, 2019b). Notably, Canada was one of only four UN member states to initially refuse to sign the original Declaration in 2007, due in large part to its ongoing Indigenous rights violations that would undermine Canada's sovereignty. In 2021, the Federal Government enacted new legislation, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act SC (2021), as a direct result of these Calls to Action. UNDRIPA (2021) requires the Government of Canada to work with Indigenous Peoples to create a reconciliatory plan, which includes, for example, contributions to economic growth with “jobs and opportunities that benefit all, while protecting the land, air and water” (Government of Canada, 2021a, para. 37). IPCAs have the potential to play an important role in the Federal Government's commitments to reconciliation and enactment of UNDRIPA, specifically regarding free, prior, and informed consent and the right to self-determination.

2 Methodology and methods

2.1 Indigenous methodologies

All aspects of this research were informed by Indigenous methodologies (IM). This approach centers Indigenous ways of knowing, voices, and philosophies that include place-based language, protocols, stories, and ceremonies throughout research processes (Absolon, 2011; Kovach, 2021). Collaboration and relationship-building are foundational to IM, as are trust, reciprocity, and respect (Kenny, 2004). IM challenges Eurocentric research paradigms that have been, and continue to be, extractive and harmful to Indigenous communities, instead calling for research practices that are collaborative, relevant to the partner community, respectful, and reciprocal (Smith, 2021). It also pushes researchers to reflexively examine their positionality and actively disrupt the systemic colonial power dynamics they benefit from within Western academia (Ignace et al., 2023).

This project is part of a long-term relationship between Courtney W. Mason (CWM) and the community of Fort Providence, primarily working with Lois Philipp, a Dene woman, former educator, tourism business owner, and community champion. CWM and Philipp have collaborated on several community-identified local food security, health, and tourism development projects. This has included numerous extended trips to the community for CWM for over a decade, and the involvement of several graduate students, including author, Emalee A. Vandermale (EAV) (O'Hare-Gordon, 2016; Wesche et al., 2016; Ross, 2019). EAV was invited to Fort Providence in the spring of 2021 to volunteer with the community garden. Later that fall, EAV was invited back to continue volunteering in the garden and to conduct research interviews. During these combined 9 weeks, EAV attended public events, volunteered in the community garden and youth center, and learnt from community members about local concerns and perspectives. The researchers' time spent in community was invaluable in building relationships and to understand local cultural contexts. Philipp was instrumental in our trips and this research, acting as gatekeeper and guide throughout the process. Philipp directed the research toward community priorities, co-developed research questions, and ensured we followed local protocols.

As outsiders to the Fort Providence community and the Dene and Métis cultures, we recognize our restricted understanding of the experiences and worldviews informed by place-based ancestry and language that are presented in this paper. We approached this work with respect, humility, and a willingness to learn from and share with the Fort Providence community. By following local protocol, aligning our processes with IM, and working closely with Philipp, we address our positionality and research limitations by grounding our results in community voices and perspectives.

2.2 Methods

We used primarily semi-structured and unstructured interviews with open-ended questions. This method aligns with IM and follows local protocol based on past experiences of research in the community. Semi-structured interviews encourage a more conversational approach to data collection, which challenges the power dynamics between interviewer and interviewee (Kovach, 2010). The use of this dynamic and fluid method also allowed us to adapt each interview to the relationships we shared with participants. Open-ended questions encouraged interviewees to share more in-depth and personalized information, but also that they retain control over what information is shared. Given the open-ended and conversational nature of our interviews, some participants did not speak to some of the key themes of this research. It is also important to note that Fort Providence is a dynamic and diverse community, and we worked to include perspectives from a variety of community members but do not represent a homogenous experience.

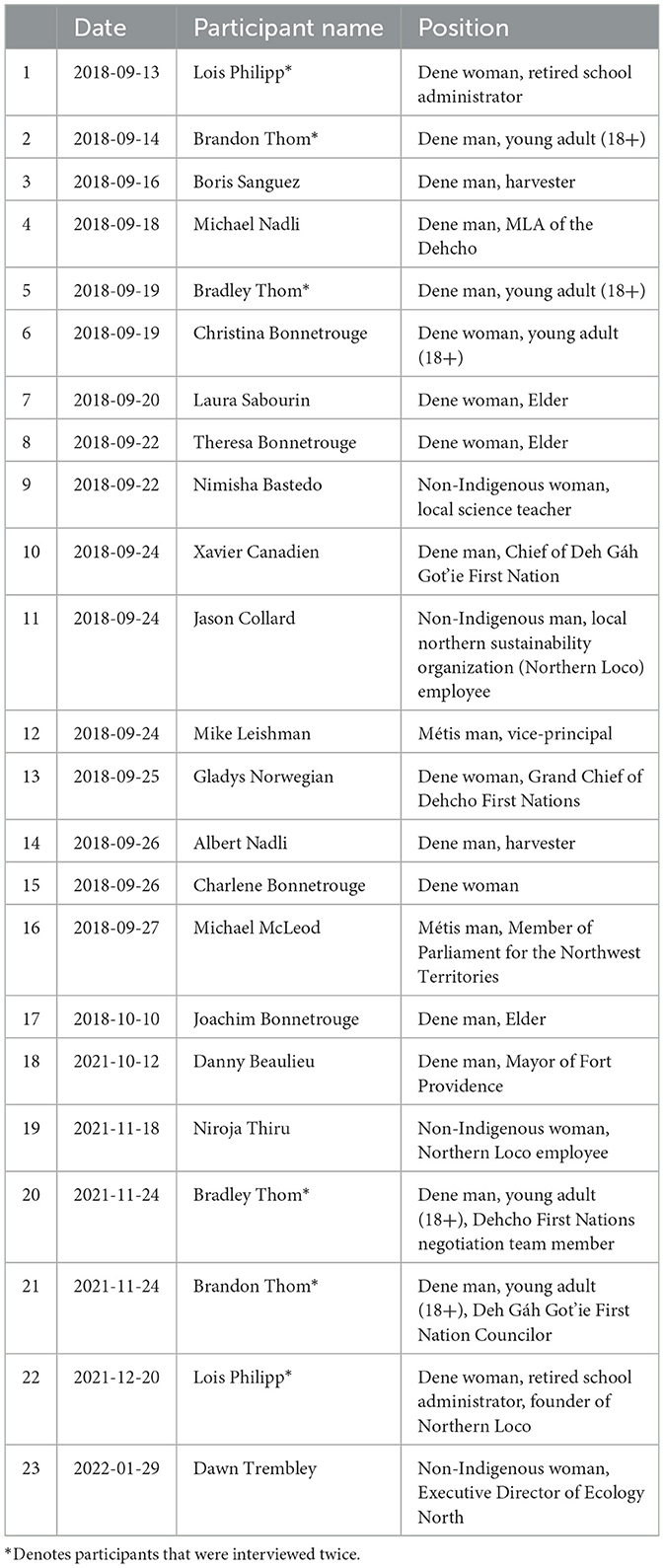

Four non-Indigenous and 16 Indigenous participants who lived in Fort Providence or other DFN communities were interviewed (see Table 1). These included harvesters, Elders, politicians, community leaders, and those involved in local food programming. Three Indigenous participants were interviewed twice with follow-up questions. Interviewees were recruited at the recommendation of Philipp and from the relationships built between authors and community members.

Table 1. List of interview participants, their roles at time of interviewing, and dates of interviews.

Each interviewee was given remuneration for their time and knowledge shared that reflected community research protocol. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. We then sent all transcripts back to each interviewee for review and correction. Participants were offered anonymity throughout the research process, but all chose to have their names associated with their interviews. These processes allow participants to protect sensitive information or provide additional context and maintain ownership of their data and words (Battiste and Henderson, 2000). These processes also foster respect and trust between interviewers and participants throughout the research process (Kovach, 2021). Each author read through all transcripts using open coding to find central themes, commonalities, and differences regarding protected areas, tourism, and community resiliency. This process was collaborative between authors. We use direct quotes extensively to ground this research in the lived experiences of participants.

2.3 Research site and community context

2.3.1 Fort Providence community profile and tourism development

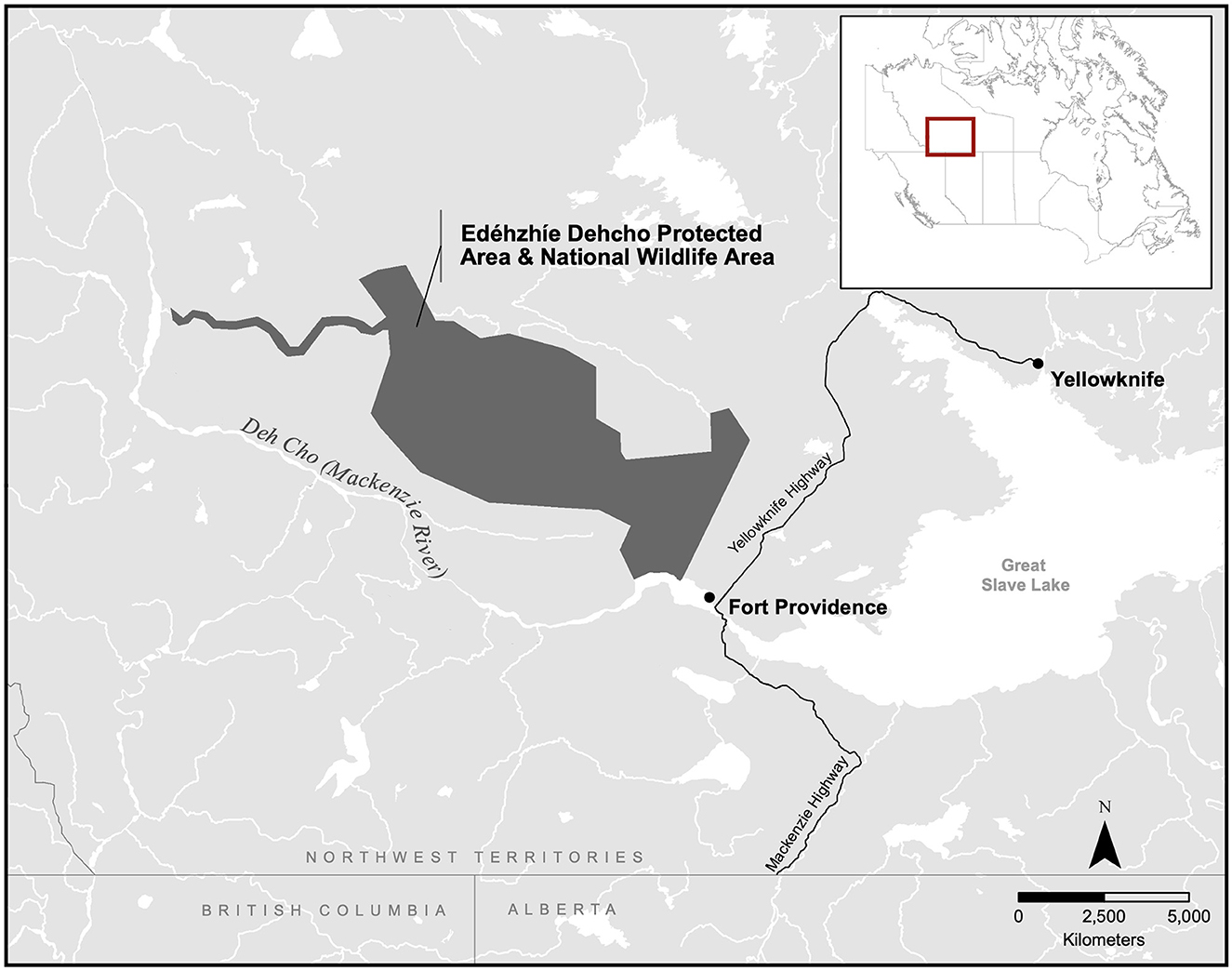

This research was done in collaboration with the Dene/Métis community of Fort Providence, located in the southwest region of the NT (see Figure 1). Fort Providence is a small, sub-Arctic hamlet, set along the banks of the Deh Cho (Mackenzie River), with a population of about 700 people, 87% of those identifying as Indigenous (Government of Northwest Territories, 2023). There are three local governments: (1) the territorial Government of Northwest Territories (GNWT), represented by the Hamlet of Fort Providence; (2) the Deh Gáh Got'ie First Nation; and (3) the Fort Providence Métis Council. The Deh Gáh Got'ie First Nation and Fort Providence Métis Council are part of the regional DFN Government with seven other Dene and one other Métis Nation (Dehcho First Nations, 2022a). The DFN is currently engaged in negotiations with the Federal and Territorial governments on the terms for agreements on lands, resources, and public governance of their ancestral territory (Dehcho First Nations, 2022b). All Nations in the DFN are involved in managing and benefiting from Edéhzhíe (Dehcho First Nations Government of Canada, 2018). Fort Providence is one of many DFN communities in Edéhzhíe's proximity that continue to access the area. This paper centers on Fort Providence because of our pre-existing relationships with the community, but our research also included participants from other DFN communities.

Figure 1. Map of study site. Fort Providence is situated on the banks of the Deh Cho (Mackenzie River), along the Yellowknife Highway, and adjacent to the Edéhzhíe Dehcho Protected Area and National Wildlife Area. Map created by Olea Vandermale, 2023.

Extensive tourism industries already exist in the NT and have played a key part in the GNWT's economic growth strategy over the last decade (Government of Northwest Territories, 2016; Government of Northwest Territories., 2021). The GNWT has specifically invested in Indigenous tourism to build capacity within Indigenous communities across the NT and meet the market demand for authentic Indigenous tourism experiences (NorthWays Consulting., 2010). Fort Providence's current tourism infrastructure includes the locally owned Snowshoe Inn, a territorial campground that provides seasonal employment, and two restaurants. The Hamlet is situated along a major highway, the Deh Cho (Mackenzie River), and other protected areas, which make it a favorable place to develop land-based tourism businesses (Deh Cho Environmental, 2003). Located just east of Fort Providence is the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary. This houses a large herd of wood bison that attracts many visitors to the area. Fort Providence also hosts an array of events and an active traditional craft market, which could support cultural tourism experiences (Snowshoe Inn, 2023). Participants noted that the Deh Gáh Got'ie First Nation had planned to dedicate some of its infrastructure (i.e., a lodge and canoes) to build local tourism businesses. However, they had not developed these opportunities at the time of interviewing.

Employment opportunities are generally limited in the community. A 2019 GNWT survey reported that only 16% of residents are satisfied with employment opportunities in Fort Providence (Northwest Territories Bureau of Statistics, 2019). This survey lists paraprofessionals, heavy equipment operators, and cleaners as the hamlet's three main occupations (2019). Local, land-based employment was a concern for many community members who have seen a decline in these industries over the last few decades (Ross and Mason, 2020b). Funded by the Federal Government, the K'éhodi Guardians offer one employment opportunity to fill this gap in Fort Providence and other DFN communities (Dehcho First Nations Government of Canada, 2018). In total, the program provides 14.5 full-time positions and contributes to job-related capacity building by fostering ecological monitoring and cultural skills (Government of Canada, 2022b). They also have specific positions for youth that facilitate intergenerational knowledge transfer and youth mentoring (Heidi R. Wiebe Consulting Ltd., 2017). These positions provide culturally and socio-economically meaningful opportunities (Social Ventures Australia, 2016). While tourism infrastructure might currently be limited, tourism has been part of community and regional planning for decades and can provide another local, land-based economy (Deh Cho Environmental, 2003; The Dehcho Land Use Planning Committee, 2006).

2.3.2 Conservation histories of the Northwest Territories and the creation of Edéhzhíe

Colonial conservation policies differed in the NT compared to southern regions. In the NT, early twentieth-century conservation regimes were intimately tied to the Federal Government's attempts to assert political and economic power over the northern hinterland region. Compared to southern Canada, the harsher climate, prevailing Indigenous subsistence activities, and presence of great wildlife herds (caribou, bison, and muskox) in the North limited the widespread establishment of the same colonial conservation practices used in the South (Sandlos, 2014). In the North, colonial conservation policies focused on wildlife protection and hunting regulations (Sandlos, 2007). These policies were largely premised on racist understandings of Indigenous subsistence practices and economies as wasteful and inferior to Western systems and facilitated Western conservation and economic agendas: controlled, scientific management of wildlife for leisure and commercial use, such as agriculture. Combined with other colonial land use and economic pressures, wildlife officials and police began establishing protected areas and strict harvest policies in attempts to control Dene, Inuit, and Cree Peoples' access to their territories, subsistence practices, and economies (Sandlos, 2007). Other attempts included coercive education programs and relocation of Indigenous communities to reduce pressure on specific big game wildlife species. These actions undermined Indigenous Peoples' sovereignty and knowledges and greatly impacted their food, cultural, and economic systems (Kulchyski and Tester, 2008; Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018).

In the NT, Indigenous Peoples' resistance to these colonial impositions included Treaty boycotts and direct refusal of hunting restrictions, which were sometimes supported by missionaries and Crown officials living in the North (Sandlos, 2007). Part of this resistance also included playing a greater role in the decision-making of conservation policies and broader land use management increasingly throughout the twentieth century. However, tensions over the extent to which Indigenous Peoples have had their rights and perspectives respected and consulted in this involvement vary greatly (Nadasdy, 2005; Armitage et al., 2011; Sandlos, 2014; Clark and Joe-Strack, 2017).

Ongoing conflicts over Crown and Indigenous land rights, specifically regarding conservation, natural resource development, and Treaty rights, culminated in the 1970s with the announcement of a proposed pipeline along the Deh Cho (Mackenzie River) (Watkins, 1977; Nuttall, 2010). The Dene and Métis throughout the Mackenzie Valley have continually sought to affirm land, resource, and self-governance rights with the Federal and emerging Territorial Governments. This included the negotiation and signing of Treaty 11, which was intended as a peace and friendship agreement with no intent of ceding their lands (Asch, 2013). With the announcement of a pipeline through their territory, Elders, and leaders from the DFN and other Dene Nations began to politically organize to clarify land rights outlined in Treaty 11, including legal action [i.e., the Paulette et al. v The Queen (1977) case and Berger (1977) Inquiry]. The Berger Inquiry halted pipeline development and recommended new land claim agreements to move through these legal tensions (Erasmus et al., 2003). Most Nations of Treaty 11 have concluded these agreements; the DFN, however, have been in formal negotiations with the Territorial and Federal Governments since the 1990s (Dehcho First Nations, 2022b). For the DFN, part of this negotiation includes working with the Tłįchǫ Government (a neighboring Dene Nation) to protect a vital cultural, spiritual, and ecological portion of their shared territory, Edéhzhíe, under various territorial and federal protections.

After decades of planning and negotiations, and with the Federal Government's endorsement of IPCAs in 2018, the DFN finally established Edéhzhíe as a Dehcho Protected Area under Dehcho law and ceremony in October 2018; the Tłicho Government is not currently involved in Edéhzhíe's management. At this time, they signed the Edéhzhíe Establishment Agreement (2018), which outlines the DFN and Canadian Governments' cooperative agreement to protect and steward the area. It received its additional designation as a National Wildlife Area under the Canada Wildlife Act (1985) in 2022. Many adjacent Dehcho and Tłicho community members maintain cabins in the area and continue to access it for cultural and subsistence reasons. It is a remote location and only accessible by boat, traditional trails, or air, but many visitors have frequently traveled to its extensive lakes and rivers to fish. Protecting Edéhzhíe through DFN and federal law ensures this area can continue to support broader environmental resiliency and the surrounding communities' land-based practices and economies.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Opportunities and challenges of tourism development around Edéhzhíe

Tourism businesses are currently limited in Fort Providence compared to others in the NT and DFN territory. Participants attributed cultural capacity, land access, and complex land use dynamics as some of the main barriers to tourism development. Despite the challenges, participants recognized the rise in popularity of Indigenous tourism across the NT and expressed their interest in developing land-based cultural and ecotourism experiences to grow this industry. For example, Boris Sanguez (2018), Dene harvester, hopes to establish a business that would “get people out with cameras in dog teams, take people out for fall hunting, set up a base camp out there (on the land).” Other community members suggested guided hunting or fishing experiences, campground hosting along the river, or boat and equipment rentals for access from Fort Providence (Bradley Thom, 2021; Brandon Thom, 2021; Philipp, 2021). Interviewees outlined various actions taken at the local level to develop tourism economies, such as a lodge owned by the Deh Gáh Got'ie First Nation. Philipp (2021) highlighted that this lodge was a project that community leaders had “built up with the idea of renting it out to tourism. But then the pandemic hit.”

COVID-19 greatly restricted access to the NT in 2020 and 2021 (Government of Northwest Territories, 2020a,b). As Philipp describes above, this had a direct impact on tourism economies in the hamlet. In addition to COVID-19 access restrictions, tourism in Fort Providence faces many interrelated barriers. Like other rural Indigenous communities, capacity and funding are often stretched, which greatly impact the ability of community members to start and maintain new tourism ventures. Despite Fort Providence's proximity to a key transportation highway and waterways, the community's relative remoteness and lack of infrastructure may affect tourists' ability to reach the community and participate in land-based tourism. Brandon Thom (2021), Dene youth and Deh Gáh Got'ie First Nation Councilor, explains: “we still need infrastructure. We still need access to the land. There's not much development here. … We have some beautiful views here, it's just not at all accessible.” Remoteness, while a desirable trait in some ecotourism industries, also impacts the environmental sustainability of these economies that rely on expensive and carbon-intensive transportation networks to bring visitors to the area.

Cultural and ecotourism development in Fort Providence face various other challenges rooted in colonial histories of disruption and marginalization, and policies designed to undermine the DFN's sovereignty over their lands. These were compounded by widespread illnesses, failed treaty promises from the Federal Government, forced attendance of Indigenous children at residential schools, and the assertion of extractive economies across the NT (Watkins, 1977; Fumoleau, 2004; Abel, 2005). Over the last 50 years, lifestyle changes, gaps in traditional skills and knowledge, and rising costs associated with land-based travel have created many barriers for community members to access the land (Ross and Mason, 2020a). These challenges are exacerbated by environmental changes that affect regional hydrologic cycles and animal movement patterns. Community members are increasingly concerned about their safety while traveling on the river and ice, as well as the quality and availability of traditional foods (Ross and Mason, 2020b).

Cultural capacity and land access not only pose immediate challenges to the community's cultural continuities, food security, and wellness but also impact tourism development. Philipp (2021) suggests that because many residents still actively participate in traditional subsistence activities, this cultural capacity makes Fort Providence “situated in the perfect position in terms of offering a real good cultural experience.” However, cultural practices are increasingly affected by colonial legacies that have disrupted land-based lifestyles and the transfer of traditional knowledge and skills in youth today. Michael McLeod (2018), Dene man and Member of Parliament for the NT explains: “we have generations now where if you put a rabbit in front of someone without skinning it, cutting it up, gutting it and cooking it for them, they wouldn't know what to do with it.” This can greatly impact youth's ability to participate in land-based tourism and the long-term survival of these businesses.

These barriers are grounded in colonial-capitalist industries and land use systems that constrain community members' sovereignty over, and access to, their ancestral lands. Bradley Thom (2021), Dene youth and DFN negotiation team member, suggests that tourism is “part of the vision and just something that we can start implementing once we finished the AIP (the DFN's self-governance and land claim agreement).” The interrelated barriers, COVID-19 delays, and ongoing governance and land use negotiations add layers of uncertainty to the realities of tourism industries in Fort Providence and the broader DFN region. Balancing tourism development with access to land for food, cultural, spiritual, and economic reasons and with complex land use decisions may present tensions moving forward.

Participants are cautiously optimistic about tourism development surrounding Edéhzhíe and the impact the protected area can play in this growth. Brandon Thom (2021) suggests that Edéhzhíe “is the perfect place for tourism” and emphasizes, “how else are we going to make money on a protected area? … Tourism should be a big part of the economic growth.” Protected areas can have many benefits to tourism development in adjacent communities, including localized environmental protections that support land-based economies, food security, and cultural continuities (Bennett et al., 2012). As a co-designated National Wildlife Area, public access to Edéhzhíe is controlled through a permitting process, apart from Treaty and s. 35 of Canada's The Constitution Act (1982) rights holders acting in accordance with DFN law (Government of Canada, 2022a). National Wildlife Areas are primarily set aside for wildlife conservation and research. Unlike other protected area designations, like National Parks and National Park Reserves, the potential for extensive tourism development in Edéhzhíe may now be limited by this co-designation. However, it does align with the DFN's long-standing desires to protect wildlife in Edéhzhíe and keep it free of natural resource extraction (Watkins, 1977; The Dehcho Land Use Planning Committee, 2006).

Tourism was the only industry initially proposed in early land use plans for Edéhzhíe but is not mentioned in the Edéhzhíe Establishment Agreement (2018). The DFN and Crown legal protections of an IPCA and National Wildlife Area, respectively, ensure the area can continue to support the surrounding waterways, habitats, and communities, and sustain land-based activities and potential tourism business both within and outside of Edéhzhíe's boundaries. Furthermore, a permitting process may not fully hinder tourism activities in Edéhzhíe. Other protected areas, such as Gwaii Haanas, operate extensive tourism industries and require permits and attendance of an orientation session prior to traveling to the area (Parks Canada, 2023).

Many decisions are still being determined by DFN and community leaders regarding the role that Edéhzhíe can play in tourism development and Fort Providence's ability to support this industry. Despite the barriers and uncertainty, interviewees were hopeful that Edéhzhíe would contribute to tourism development and provide opportunities to address some community concerns in ways that support DFN governance and environmental resiliency. The following examines participants' perspectives of how Edéhzhíe and tourism development can support socio-economic sustainability, land access and cultural continuities, and environmental stewardship in more detail. We then discuss how these contribute to DFN governance, Crown-DFN reconciliation processes, and environmental resiliency.

3.1.1 Socio-economic sustainability

Community members suggested that tourism could create more sustainable economies that support land-based livelihoods. Currently, there are very few employment opportunities in Fort Providence, especially those that support land-based livelihoods. Community members have increasingly moved away from land-based livelihoods for a myriad of socio-economic reasons, including but not limited to the collapse of the fur trade, entering the wage-based economy, and pursuing higher education away from the community. Residents are often stuck between having enough time away from work to dedicate to land-based activities and earning enough money to afford to access the land. Philipp (2021), who is a driver of numerous sustainable development programs throughout the community, expands on these tensions:

We're not going to get anywhere in our communities in terms of viability, that sustainability piece, we need to create opportunities that create an economic base. You know, I've often wondered, struggled with the viability of Indigenous communities in this [Western] model. So how do we empower our communities to become the best versions of who we are, in a way that is a hybrid between what is traditional and what is Western?

The land-based tourism examples that community members propose reflect this “hybrid” economy. Nimisha Bastedo (2018), a non-Indigenous teacher in Fort Providence, expands on how a camping host tourism venture can be a “sustainable form of business” and financially support land-based livelihoods: “have it so that people have jobs out there and they can permanently stay out there and maintain the camps.”

While traditional and Western economies may conflict at times regarding their time commitments and requirements, rural Indigenous communities across the country are increasingly adapting tourism to fit their traditional economies and support land-based activities (Hinch, 1995; Notzke, 1999; Colton, 2005; Lynch et al., 2010). One example of how a different northern Indigenous community is using tourism to overcome these tensions is in the Moose Cree First Nation and MoCreebec Council of the Cree Nation of Moose Factory, Ontario. Some community members work in established tourism industries as fishing or hunting guides, and use this industry to facilitate the time and financial support to practice traditional activities, as well as to provide income between seasonal subsistence practices (Lemelin et al., 2015). This is an important departure from many current employment opportunities in Fort Providence that limit community members' abilities to access the land and participate in subsistence activities or traditional economies. Joachim Bonnetrouge (2018), former Chief of the Deh Gáh Got'ie First Nation, describes his own experience balancing work and harvest commitments:

If you really wanted a moose, you would pick your boat, and try to travel light, but you still need, because it's fall time, you still need a canvas tent and to get some food and you pretty well have to go about 100 miles down the river… and even for me that's a big commitment. I was committed to meetings in town, so I had to work around meeting dates, and I still had to do a little bit of work with a few different groups. You still need income, eh.

Other work has suggested that diversifying local economies to include more integrated, creative, and self-determined options challenge these intertwined temporal and financial tensions and offer Indigenous community members more options to pursue wage-based income and subsistence practices (Kuokkanen, 2011; Boulé et al., 2021; Loukes et al., 2021).

Many participants also expressed a desire to move away from natural resource extraction industries and viewed Edéhzhíe as a step toward supporting more socio-economic and environmentally sustainable opportunities through tourism development. Brandon Thom (2021) believes that tourism is an “untapped resource” in Fort Providence and “where most of our economies are going to come from in the future, [instead of] … mining or logging.” The diversification and development of sustainable economies are important in northern and rural Indigenous communities. Across the North, Crown governments have imposed extractive economies on Indigenous territories in ways that have intricately tied these economies to both national and northern development (Nuttall, 2010; Keeling and Sandlos, 2015b). As a result, northern Indigenous communities are continually forced to navigate complex land use decisions. While extractive economies provide certain benefits to Indigenous communities, they have also been sources of significant conflict and harm. Environmental contamination, habitat destruction, and socio-economic and political disparities are common impacts of natural resource development in northern Indigenous communities (Paci and Villebrun, 2005; Kulchyski and Bernauer, 2014; Keeling and Sandlos, 2015a; Koutouki et al., 2018). Tourism, especially when connected to protected areas, is widely viewed as a more socio-economically sustainable alternative to boom-bust extractive industries that fail to provide long-term benefits to Indigenous economies, food security, or environments (Butler and Hinch, 2007; Bennett et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2023).

3.1.2 Access to land and cultural continuities

As participants describe above, the types of tourism business they hope to develop all involve increasing access to the land for community members and strengthening cultural continuities. Tourism that supports land-based livelihoods can greatly reduce the financial burdens that community members experience to access the land and facilitate intergenerational knowledge transfer and skill development. Bastedo (2018) elaborates on the campsite business described above and suggests that this could “train people to be young guides on the land so that those traditional skills can have a monetary value.” Similarly, Laura Sabourin (2018), Dene Elder, describes how tourism can financially support a multifunctional community building that offers a holistic and layered approach to local economies and reflects traditional lifeways:

What I would really like to see is a cultural building, where they would offer trapping training, moose hide tanning programs. … Have these programs ongoing and make them year-round, for people to come there, to eat and be welcome. It's almost like a food bank I guess, but like a traditional one, where with the food comes working on hides outside and sew inside. … people could do lots of demonstrations, and it would be open for tourists. Tourists could come there and see how we live, and share ideas, and sample some of the traditional foods!

The tourism examples Bastedo and Sabourin describe here fill much-needed gaps in the community. Youth and families are often missed in existing land-based programming and there are few spaces open to all ages in the community and that focus on teaching traditional practices.

Indigenous communities across the North experience the highest rates of food insecurity in the country (Council of Canadian Academies, 2014). While traditional foods alone cannot solve this problem, they do provide vital nutritional and cultural value to Indigenous communities (Robidoux and Mason, 2017). Fort Providence employs various land-based food programming initiatives designed to facilitate intergenerational knowledge transfer and skill development, as well as to provide some improved access to traditional foods (Wesche et al., 2016; Ross and Mason, 2020a). Philipp (2021) is of the opinion that community-led fishing or hunting tourism would have a positive impact on food security and “might secure it a little more.” She explains that “when you're taking clients out onto the land to harvest, you're not going to eat it all, so it'll go to the community members” (2021). In other rural and northern Indigenous communities, conservation hunting tourism programs bring high-value tourists to communities, which can be coupled with food sovereignty initiatives that increase access to considerable amounts of local, land-based foods (Foote and Wenzel, 2007; Islam and Berkes, 2016; Boulé and Mason, 2019).

3.1.3 Environmental stewardship

Any type of tourism to rural areas is imbued with inherent challenges regarding environmental sustainability. Travel almost always necessitates some form of fossil fuel dependent transportation. While this type of barrier is difficult to circumnavigate completely, community members described various ways Indigenous-led tourism experiences could contribute to broader conservation values. For example, in recent years, some visitors have caused localized environmental damage and have been caught overfishing in the Fort Providence area. Bradley Thom (2018) suggests that Dehcho fishing guides could educate tourists about local culture and stewardship practices:

If you are in a party of four or more you have to hire a local guide from one of the local communities so that they can go out with you, show you what to do regarding cultural procedures, but also to make sure that you are not taking more than you're legally supposed to.

Research that examined Indigenous tourism businesses and sustainable development in Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Fiji, found that a common link between each business was “respect for the environment, local culture and ‘doing good for everyone's sake”' (Scheyvens et al., 2021, 8). Other examples of Indigenous guiding businesses in rural regions across Canada suggest that they bring broader awareness to cultural and conservation issues with visitors, which supports cross-cultural learning and contributes to broader conservation in these areas (Bennett et al., 2012; Holmes et al., 2016; Coastal First Nations Great Bear Initiative, 2022a).

In addition to active stewardship and educating guests, Bradley Thom (2021) is optimistic about the layered protection that Edéhzhíe provides:

Once we finish up this management planning process, then we can turn it into a National Wildlife Area on top of an Indigenous Protected Area. So, there's just different layers, like there's the Dehcho conservation laws for protections, and then there's the GNWT subsurface, and then after that, you're going to slap the National Wildlife Area on top as well. So, it's going to be super protected and always be there to just be, in terms of doing its job that nature does for free.

Sabourin (2018) adds that a local presence on the water provides an important regulatory function and it has already had an influence at the local level on non-resident fishing activities: “we had to monitor the river and I think they did a pretty good job because I haven't seen [visitors] down there once… it's just our people down there.” To achieve this level of monitoring requires great resources and available personnel. The Federal Government's provisioning of the K'éhodi Guardians can support local food security, climate change and other regional monitoring and response objectives throughout Edéhzhíe and the surrounding areas (Morritt-Jacobs, 2020; Price et al., 2022).

Not all interviewees were as convinced of the long-term ramifications of Crown conservation policies. Danny Beaulieu (2021), Dene man and Mayor of Fort Providence, explains: “you could a make protected area, you could make policies, and then… of course (Crown governments) make regulations that can be changed.” Beaulieu's lack of confidence is shared by some scholars who question Crown governments' long-term support of some IPCAs as they continue to allocate industry tenures and permits that conflict with the values that inspire IPCA creation and stewardship (Artelle et al., 2019; Zurba et al., 2019; Youdelis et al., 2021; Lamb et al., 2022). They suggest the Crown's fragmented conservation systems and split jurisdictions, the natural resource development pressures, and a lack of specific IPCA legislation and support for Indigenous governance collectively limit the long-term effectiveness of Indigenous-led conservation.

3.2 The contributions of Indigenous-led conservation and tourism to governance, reconciliation, and environmental resiliency

Through the establishment of Edéhzhíe, the DFN has increased its decision-making authority and stewardship over a small part of their territory. Provisions in the Edéhzhíe Establishment Agreement to increase Dehcho community members' access to the land can also help overcome some of the cultural capacity barriers discussed above (Dehcho First Nations Government of Canada, 2018). Furthermore, through Edéhzhíe, the DFN has secured governance over a small parcel of their land, albeit in a cooperative partnership with the Federal Government. Part of Edéhzhíe's establishment includes the Federal Government's provisioning of the K'éhodi Guardians who carry out the stewardship of Edéhzhíe. A 2016 study examining the Dehcho and Łutsël K'é First Nations (2019) guardian programs found that, on top of the various community and environmental benefits these guardians hold, they also “represent a shift from simply asserting their rights to actively taking charge of the responsibilities that come with those rights” (Social Ventures Australia, 2016, p. 18). Edéhzhíe is one way the DFN is bolstering their broader governance and stewardship of their ancestral territories based on their own priorities, knowledge, and law.

The ways participants envision sustainable tourism development in their community, whether within or supported by Edéhzhíe, represent an extension of this stewardship and sovereignty. Interviewees highlight how Indigenous-led conservation and tourism offer opportunities to transform colonial economic and conservation systems that continue to perpetuate unequal power dynamics, socio-economic disparities, and climate change (Bernauer and Roth, 2021). IPCAs embed socio-economic and cultural values alongside environmental ones, reflecting Indigenous Peoples' long-standing practices, relationships, and knowledges (Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018). This approach to conservation is inherently more holistic than current Western paradigms. Furthermore, extensive research demonstrates the ways Indigenous Peoples across the globe have adapted tourism economies to fit their values and lifeways, in ways that provide critical alternatives to prevailing Western economic systems (Colton, 2005; Carr, 2007; Lemelin et al., 2015; Scheyvens et al., 2021).

Crown support for Indigenous-led conservation and tourism alone cannot reconcile ongoing colonial harms. The governance and environmental protections established through Edéhzhíe require long-term commitments from Indigenous and Crown governments to nation-to-nation relationships, among other processes of reconciliation. While not everyone holds such optimistic perspectives, community members, such as Bradley Thom (2021), see Edéhzhíe as contributing toward positive change:

We [the Government of Canada and DFN] have a very unique management board, where we both have senior representatives, and it's like negotiating every time, but they're usually pretty reasonable. Like if the Dehcho is saying, “I think we should do things this way,” [the Government of Canada responds], “okay, for sure.” And then the Canadian Wildlife Service just makes sure that they have the power to do it within their limitations, and just try to find a way that works for both parties, because I guess the [Federal] Government's a bit more structured. But they've never had to deal with Indigenous Protected Areas before. This is all very new to them as well. So, they are a little bit worried to set new precedence. … but no matter what they're doing, they're setting precedents.

It is important to note that Edéhzhíe is only a small parcel of the DFN's broader ancestral territory. As Bradley Thom highlights above, the DFN is still engaged in negotiations on a self-governance and land claims agreement with the GNWT and the Government of Canada to rectify unfulfilled treaty agreements and other injustices imposed on the Dehcho by Crown governments (Dehcho First Nations, 2022b). These negotiations pertain to the larger extent of the DFN's territory, rather than the relatively small area of Edéhzhíe. How this process unfolds will greatly influence DFN governance, Crown-DFN reconciliation, and broader environmental resiliency. It will also play a significant role in tourism development in the communities surrounding Edéhzhíe.

Partnerships through Indigenous-led conservation are one of many strategies Indigenous communities and the Federal Government are working together toward to address continued colonial legacies. Many scholars add important critiques of the ways government recognition and support of IPCAs complicate Indigenous Peoples' governance, stewardship, and processes of reconciliation (Zurba et al., 2019; Youdelis et al., 2021; Townsend and Roth, 2023). As IPCAs grow in number and application, these tensions continue to play out in diverse ways. Early observations from current IPCA examples and literature describe the ways IPCAs represent and are facilitating important changes to Crown-Indigenous relations, land uses, economies, and conservation (Artelle et al., 2019; Moola and Roth, 2019; Tran et al., 2020; Vogel et al., 2022; White-hińačačišt, 2022; Mansuy et al., 2023). The long-term impacts of these initial contributions of Indigenous-led conservation to sustainable economic development, Crown-Indigenous relationships, and climate change adaptation must continue to be examined and critically assessed.

4 Conclusion

Canada's conservation regimes have greatly disrupted Indigenous Peoples' lives. Indigenous communities continue to push Crown policies to better reflect, protect, and uphold Indigenous rights and responsibilities to their lands, with IPCAs acting as one of these actions. The Federal Government's current UNDRIP legislation and endorsement of Indigenous-led conservation represent significant steps toward redressing historic harms and forging new partnerships with Indigenous communities. While reconciliation processes and effective conservation depend on long-term commitments, and thus, are difficult to assess in the early stages of IPCA developments, the most immediate benefits of IPCAs are to Indigenous communities.

As this research demonstrates, the Dene/Métis community of Fort Providence envisions IPCAs and tourism development as ways to address current socio-economic and environmental challenges and improve access to, and decision-making power over, their lands. With Edéhzhíe's designation and cooperative management structure, the DFN and Dehcho communities have greater access to, stewardship of, and decision-making authority over their territories. At the same time, tourism economies that align with community values can build on Edéhzhíe's benefits and offer critical alternatives to natural resource extraction that combine local food sovereignty, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and environmental stewardship with economic development. The COVID-19 pandemic greatly influenced the tourism industry in the NT and Fort Providence, including participants' perceptions of Edéhzhíe's influence on tourism. Our results reflect this limitation and the early stages of both tourism and Edéhzhíe. Future work is needed to better understand how northern and rural Indigenous communities are adapting tourism and IPCAs to fit their own socio-economic, cultural, and environmental objectives.

Travel to rural areas and carbon-intensive experiences inherently contradict the extent to which tourism development in Fort Providence can contribute to environmental sustainability. Furthermore, protected areas, including IPCAs, still represent patchwork conservation that can justify industrial development outside of their boundaries (Bernauer and Roth, 2021). It is unfair to expect Indigenous-led tourism businesses or conservation to operate in ways removed from the bounds of colonial, capitalist systems. These colonial legacies still greatly impact DFN governance, and the Fort Providence community's socio-economic and cultural capacity to build tourism industries. Despite constraints, participants hope that tourism development alongside Edéhzhíe will offer opportunities to challenge these systems in ways that support DFN governance and self-determination.

Canada risks focusing too heavily on area-based targets through IPCA creation, which could reify colonial protected area frameworks and legacies of exclusion (Zurba et al., 2019). Crown governments and industry must enact the appropriate relationship-building processes and policy changes to enhance conservation while also adhering to Indigenous Peoples' inherent, constitutional, and internationally protected rights and responsibilities to their ancestral territories. Natural resource tenures and development, ongoing land claims and self-governance agreements, and the mounting effects of climate change greatly threaten the viability of these partnerships. These barriers to respectful relations also constrain Indigenous tourism economies in northern regions. Indigenous-led conservation and tourism must be supported alongside other structural changes from the Federal Government for these benefits to be realized (Corntassel, 2012; Ruru, 2012; Zurba et al., 2019; Whyte, 2020; McGregor, 2021; M'sit No'kmaq et al., 2021; Reed et al., 2022b; Townsend and Roth, 2023). This includes but is not limited to (1) wide-scale land repatriation; (2) support of Indigenous knowledges, worldviews, and practices in existing conservation structures; and (3) acknowledgment and respect for Indigenous governance, rights, and responsibilities to their territories outside of protected areas.

The immediate need for transformation is evident in northern Indigenous communities that are disproportionately affected by climate change and experience significant socio-economic disparities, due in large part to limited access to ancestral lands (Ford et al., 2010; Romero-Lankao et al., 2014; Ross and Mason, 2020a). Particular attention must be paid to how colonial conservation histories influence the contemporary experiences of northern Indigenous Peoples as they pursue increasingly complex land use management decisions. As the effects of climate change spread south from polar regions, the ways northern Indigenous communities are adapting IPCAs and tourism economies to align with and support community and environmental resiliency must also be examined.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the nature of the ethical constraints of this research. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ZXZhbmRlcm1hbGVAdHJ1LmNh.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Thompson Rivers University Research Ethics for Human Subjects Board and Northwest Territories' Aurora Research Institute. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants because verbal consent was preferred to written consent in the community, as determined by our community co-investigator and from previous initial research.

Author contributions

EAV: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CWM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Canada Insight Grant # 435-2018-1090; Canadian Mountain Network (Grant #: 1141832).

Acknowledgments

First, we thank the participants of this research for sharing their time and knowledge with us. We would also like to thank the community of Fort Providence for warmly welcoming us at their events and into their homes. This research would not haves been possible without the guidance, commitment, and generosity of Lois Philipp.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For some specific examples, see Calder et al. v. Attorney-General of British Columbia (1973); Berger (1977), R. v. Sparrow (1990), Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997), Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia (2014), and the most recent Haida Nation title case (Council of the Haida Nation British Columbia, 2024), to name a few.

2. ^The TRC led an inquiry from 2008-2015 that details the experiences and intergenerational trauma of Canada's Residential Schools. The final report describes these testimonies as well as 94 Calls to Action (Truth Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a,b). The National Inquiry into MMIWG lasted from 2016-2019 and examined community testimonies and legal documents surrounding the disproportionate violence directed to Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA peoples. Similar to the TRC, the inquiry's final reports presents the truths of these investigations and Calls for Justice to address the colonial and patriarchal policies that have caused vulnerability and inflicted violence (National Inquiry into Missing Murdered Indigenous Women Girls, 2019a,b).

References

Abel, K. M. (2005). Drum Songs: Glimpses of Dene History. Montreal, OC: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Armitage, D., Berkes, F., Dale, A., Kocho-Schellenberg, E., and Patton, E. (2011). Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada's Arctic. Global Environ. Change 21, 995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.04.006

Artelle, K. A., Zurba, M., Bhattacharyya, J., Chan, D. E., Brown, K., Housty, J., et al. (2019). Supporting resurgent indigenous-led governance: a nascent mechanism for just and effective conservation. Biol. Conserv. 240, 108–284. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108284

Asch, M. (2013). On the land cession provisions in treaty II. Ethnohistory 60, 451–467. doi: 10.1215/00141801-2140713

Battiste, M., and Henderson, J. S. Y. (2000). Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: A Global Challenge. Saskatoon: Purich Publishers.

Bennett, N., Lemelin, R. H., Koster, R., and Budke, I. (2012). A capital assets framework for appraising and building capacity for tourism development in aboriginal protected area gateway communities. Tour. Manage. 33, 752–766. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.08.009

Berger, T. R. (1977). Northern Frontier, Northern Homeland: The Report of the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry, Vol. 1. Québec, QC: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Bernauer, W., and Roth, R. (2021). protected areas and extractive hegemony: a case study of marine protected areas in the Qikiqtani (Baffin Island) region of Nunavut, Canada. Geoforum 120, 208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.01.011

Bhattacharyya, J., Murray, M., and Whittaker, C. (2017). Nexwagweẑ?an: Community Vision and Management Goals for Dasiqox Tribal Park (Summary) [pdf]. Available online at: https://dasiqox.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/DTP_VisionSummary-April-2018-web.pdf (accessed October 20, 2021).

Boulé, K., Vayro, J., and Mason, C. W. (2021). Conservation, hunting policy, and rural livelihoods in British Columbia. J. Rural Commun. Dev. 16, 108–132. Available online at: https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/1943 (accessed June 18, 2024).

Boulé, K. L., and Mason, C. W. (2019). Local perspectives on sport hunting and tourism economies: stereotypes, sustainability, and inclusion in British Columbia's hunting industries. Sport History Rev. 50, 93–115. doi: 10.1123/shr.2018-0023

Butler, R., and Hinch, T. (2007). Tourism and Indigenous Peoples: Issues and Implications. London: Routledge.

Carr, A. (2007). “Māori nature tourism businesses: connecting with the land,” in Tourism and Indigenous Peoples: Issues and Implications, eds. R. Butler and T. Hinch (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann), 113–127.

Carroll, C. (2014). Native enclosures: tribal national parks and the progressive politics of environmental stewardship in indian country. Geoforum 53, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.02.003

Clark, D., and Joe-Strack, J. (2017). Keeping the Co in the co-management of northern resources. Northern Pub. Affairs 5, 71–74. Available online at: https://research-groups.usask.ca/human-wildlife-interaction/documents/clark–joe-strack-2017-keeping-the-co-in-the-co-management-of-northern-resources.pdf (accessed June 18, 2024).

Coastal First Nations Great Bear Initiative (2022a). Coastal Guardian Watchmen: Stewarding the Coast For All, A Case for Investment. Vancouver, BC.

Coastal First Nations Great Bear Initiative (2022b). Sustainable Forests. Available online at: https://coastalfirstnations.ca/our-economy/sustainable-forests/ (accessed December 4, 2022).

Colton, J. W. (2005). Indigenous tourism development in northern Canada: beyond economic incentives. The Can. J. Nat. Stu. 1, 185–206. Available online at: https://iportal.usask.ca/docs/ind_art_cjns_v25/cjnsv25no1_pg185-206.pdf (accessed June 18, 2024).

Convention on Biological Diversity (2010). Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020, Including Aichi Biodiversity Targets.

Coristine, L. E., Jacob, A. L., Schuster, R., Otto, S. P., Baron, N. E., Bennett, N. J., et al. (2018). Informing Canada's commitment to biodiversity conservation: a science-based framework to help guide protected areas designation through target 1 and beyond. FACETS 3, 531–562. doi: 10.1139/facets-2017-0102

Corntassel, J. (2012). Re-envisioning resurgence: indigenous pathways to decolonization and sustainable self-determination. Decoloniz. Indig. Educ. Soc. 1, 86–101. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18627/15550 (accessed June 18, 2024).

Council of Canadian Academies (2014). Aboriginal Food Security in Northern Canada: An Assessment of the State of Knowledge. Available online at: https://cca-reports.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/foodsecurity_fullreporten.pdf (accessed October 12, 2021).

Council of the Haida Nation and British Columbia (2024). Gaayhllxid • Gíihlagalgang ‘Rising Tide' Haida Title Lands Agreement. Available online at: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/natural-resource-stewardship/consulting-with-first-nations/agreements/draft_haida_title_lands_agreement_27march2024_bilateral.pdf (accessed June 18, 2024)

Cruikshank, J. (2005). Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

Deh Cho Environmental (2003). Tourism Potential in the Deh Cho, NWT: A Literature Review and Spatial Analysis. Available online at: https://dehcholands.org/resources/final-research-reports/final-report-tourism-potential-dehcho-nwt-literature-review-and (accessed February 8, 2024).

Dehcho First Nations and Government of Canada (2001). The Deh Cho First Nations Interim Measures Agreement. Fort Simpson.

Dehcho First Nations and Government of Canada (2018). Edéhzhíe Establishment Agreement. Available online at: https://dehcho.org/docs/Edehzhie-Establishment-Agreement.pdf

Devin, S., and Doberstein, B. (2004). Traditional ecological knowledge in parks management: a canadian perspective. Environments 32, 47–70. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Brent-Doberstein/publication/287716078_Traditional_ecological_knowledge_in_parks_management_A_Canadian_perspective/links/5899f3104585158bf6f8a582/Traditional-ecological-knowledge-in-parks-management-A-Canadian-perspective.pdf?_sg%5B0%5D=started_experiment_milestone&origin=journalDetail (accessed June 18, 2024).

Environment and Climate Change Canada (2023). Toward a 2030 Biodiversity Strategy for Canada: Halting and Reversing Nature Loss. Government of Canada. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/wildlife-plants-species/biodiversity/2030-biodiversity-strategy-canada.html (accessed November 27, 2023).

Erasmus, B., Paci, J. C. D., and Fox, S. I. (2003). A study in institution building for dene governance in the Canadian north: a history of the development of the dene national office. Indig. Nat. Stu. J. 4, 25–51. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25606239 (accessed June 18, 2024).

Foote, L., and Wenzel, G. (2007). “Conservation hunting concepts, Canada's Inuit and polar bear hunting,” in Tourism and the Consumption of Wildlife: Hunting, Shooting and Sport Fishing, ed. B. Lovelock (New York: Routledge), 188–212.

Ford, J. D., King, N., Galappaththi, E. K., Pearce, T., McDowell, G., Harper, S. L., et al. (2020). The resilience of indigenous peoples to environmental change. One Earth 2, 532–543. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.05.014

Ford, J. D., Pearce, T., Duerden, F., Furgal, C., and Smit, B. (2010). Climate change policy responses for Canada's inuit population: the importance of and opportunities for adaptation. Glob. Environ. Change 20, 177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.10.008

Fumoleau, R. (2004). As Long as This Land Shall Last: A History of Treaty 8 and Treaty 11, 1870-1939. Calgary, AB: McClelland and Stewart. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26404820 (accessed June 18, 2024).

Goetze, T. C. (2005). Empowered co-management: towards power-sharing and indigenous rights in clayoquot sound, BC. Anthropologica 1, 247−65.

Government of Canada (2021a). Backgrounder: United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. Available online at: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/declaration/about-apropos.html#:~:text=a%20daily%20basis.-,This%20Act%20requires%20the%20Government%20of%20Canada%2C%20in%20consultation%20and,and%20discrimination%20against%20Indigenous%20people (accessed August 27, 2022).

Government of Canada (2021b). Indigenous Leadership and Initiatives. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/nature-legacy/indigenous-leadership-funding.html (accessed May 22, 2022).

Government of Canada (2021c). The Government of Canada Increases Nature Protection Ambition to Address Dual Crises of Biodiversity Loss and Climate Change. Ottawa, CA. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2021/11/the-government-of-canada-increases-nature-protection-ambition-to-address-dual-crises-of-biodiversity-loss-and-climate-change.html

Government of Canada (2022a). Edéhzhíe Protected Area. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/national-wildlife-areas/locations/edehzhie.html#shr-pg0 (accessed June 18, 2024).

Government of Canada (2022b). Evaluation of the Canada Nature Fund. Gatineau, QB: Environment and Climate Change Canada, Audit and Evaluation Branch 2022.

Government of Northwest Territories (2020a). Public Health Order – COVID-19 RELAXING PHASE 2 (Effective June 12, 2020).

Government of Northwest Territories (2020b). Public Health Order – COVID-19 Travel Restrictions and Self-Isolation Protocol – as Amended July 16, 2020.

Government of Northwest Territories (2023). Population Estimates by Community: Northwest Territories, July 1, 2001 - July 1, 2022. Available online at: https://www.statsnwt.ca/population/population-estimates/bycommunity.php (accessed July 1, 2022).

Government of Northwest Territories. (2021). Tourism 2025: Roadmap to Recovery. Industry, Tourism and Investment. Available online at: https://www.ntassembly.ca/sites/assembly/files/td_368-192.pdf

Government of Canada (2023). Canada's Nature Legacy: Protecting Our Nature. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/conservation/nature-legacy.html

Government of Northwest Territories (2016). Tourism 2020: Opening Our Spectacular Home to the World. Industry, Tourism and Investment. Available online at: https://www.iti.gov.nt.ca/sites/iti/files/tourism_2020.pdf

Hart, E. J. (1983). The Selling of Canada: The CPR and the Beginnings of Canadian Tourism. Calgary, AB: Altitude Publishing.

Heidi R. Wiebe Consulting Ltd. (2017). Dehcho K'ehodi Workshop Final Workshop Report. No. 867. England: Wiebe Consulting, Ltd.