- 1Arizona State University Joint International Tourism College, Hainan University, Haikou, Hainan, China

- 2Borneo Tourism Research Centre, Faculty of Business, Economics and Accountancy, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia

This study aims to uncover what it means to be a tourist with an invisible impairment. We highlight this important yet neglected area within inclusive and accessible tourism by examining how eating disorders impact travel. The subject of eating disorders in the context of travel is not well-articulated, and academic attention toward eating disorders is scant. To explore the lived experiences of an eating disorder and travel, we adopted qualitative research methods. Our phenomenological study followed the purposeful sampling technique and conducted in-depth interviews to collect data. Since research on this neglected traveler population is at an early stage, this research contributes to a fruitful future for this research area by exploring eating disorders and their impact on travel under the key themes of lacking public social awareness, change of routine and structure, responsibility, and access to support and barriers of the skin. The findings expand scant research into traveling with an eating disorder. Importantly, this study reveals the imbalance between what is visible externally vs. the real lived experience and advocates for diversity and inclusion in the context of travel. This research calls for closer dialogue between researchers, society, and people with eating disorders, such as our participants with an eating disorder, to ensure that the value of their voices is highlighted and heard by the stakeholders of the tourism industry. The findings of this research will be helpful in fostering tourism stakeholders' ability to provide service and care for people with eating disorders and other invisible disabilities.

Introduction

Despite a growing interest in accessible tourism, scant research has been done on traveling with hidden disabilities (e.g., diabetes, epilepsy, autism spectrum disorders) or invisible impairments (McIntosh, 2020). Traveling is described as a pleasurable experience that improves the quality of life and wellbeing of the socially marginalized (McCabe and Johnson, 2013). However, contemporary society disregards the diversity and complexity of disability (Schmidt, 2016), and the existing barriers discourage people with disabilities and invisible impairments from traveling (Connell and Page, 2019). Social stigma around disability and attitudes of service providers should be improved to allow those from the neglected traveler population to participate more in travel (McKercher and Darcy, 2018). Some hurdles are distinctive to each disability dimension and individualized impairment consequences, and there are barriers that are shared by all persons with disabilities (McKercher and Darcy, 2018). Significantly, disability or impairment-related tourism research has not explored the experiences of travelers diagnosed with an eating disorder.

Eating disorders have a profound and highly specific impact on psychosocial and physical functioning (Peláez-Fernández et al., 2022). According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), the most common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. However, pica, rumination disorder, other specified- and unspecified feeding and eating disorders and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) have gained less attention. ARFID is characterized by avoidance, restrictive eating, and food phobia unrelated to weight loss, dieting, and body image issues seen in anorexia or bulimia (Rebernik et al., 2021). In the context of accessible tourism research, eating disorders have received limited attention, and related studies have yet to explore the experiences of travelers diagnosed with conditions like ARFID.

Brennan and Kulkarni (2014) contend that disruptions to daily routines, adjustments to medication schedules, spending a considerable amount of time confined to an airline cabin seat, and other variations can all have an impact on eating disorders when traveling; however, each individual may perceive these risks differently. Mostefa-Kara (2021) examined how individuals with eating disorders experienced travel and proposed that for some people, travel can help them step outside of their comfort zone and change their surroundings, which can help them focus less on their condition. Our study argues that examining eating disorders from a tourism standpoint will provide new perspectives for the travel and tourism sector. Academics studying tourism should investigate more on how eating disorders can be expressed and comprehended in relation to their effects on travel. As a result, this study explores what it means to have an eating disorder and advances the body of theoretical knowledge that inadequately addresses the requirements of individuals with ARFID in the context of travel.

Methodology

As there is little known about individuals' travel experiences with ARFID, more inductive insider understanding was first required before analyzing patterns in broader society, and due to phenomenology's distinct strengths in interpreting the nature of lived experiences, this approach was identified as the most suitable for this research (Schmidt, 2016). Further, we sought the meaning of traveling with an eating disorder rather than how many people experienced eating disorders (Giorgi, 2009). We employed purposeful sampling strategies such as key informants and snowball sampling methods to recruit potential participants for this project. Prospective participants were identified through several avenues: Facebook groups, acquaintances, contacting people within local organizations, and not-for-profit organizations. These channels were used to circulate research invitations and information and to invite interested individuals to contact us for more details about the study. The snowball technique was then used to find similar information-rich respondents. The main questions that we asked participants when selecting them for the research were:

• Are you a person with ARFID or a carer of a person with ARFID?

• Have you traveled domestically or internationally at least once in the last 5 years?

• Are you interested in discussing the experiences you have had while traveling?

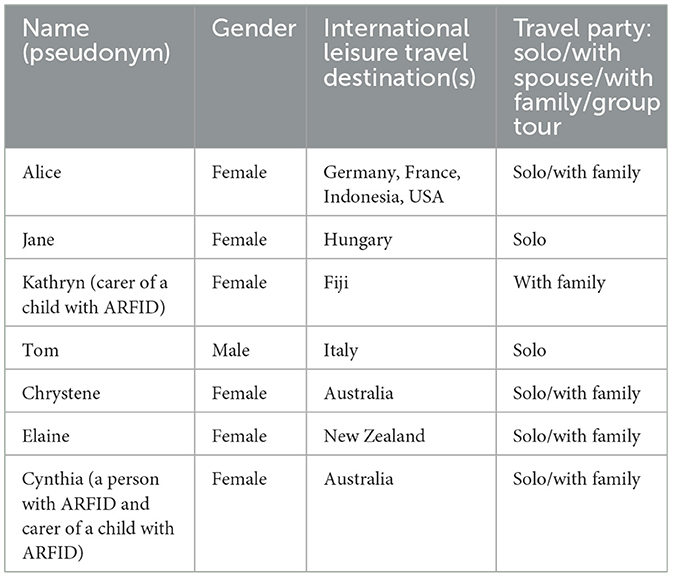

Six individuals with ARFID and one carer of a person with ARFID were involved in this study, and one of the co-authors brings inside knowledge as a carer for a child with ARFID.

We conducted fourteen phenomenological interviews (two with each participant). Each interview took approximately 45–60 min. Interviews were conducted over 1 year. Conducting two interviews was vital, as the second interview allowed for the opening up of new areas to be explored more deeply (Yoo, 2014). We were also able to contextualize further points made by participants.

Moreover, the second interview helped to increase the trustworthiness of this research and to reaffirm our understanding of the ideas the participants had expressed in the first interview (Ramanayake et al., 2022). As we wanted to understand the in-depth experiences of people with eating disorders, it was appropriate to have a small sample because having a small sample allowed us to give voice to every participant and helped us understand the depth of the phenomenon (Jennings, 2001). Then, our study used thematic analysis to analyse data.

Results

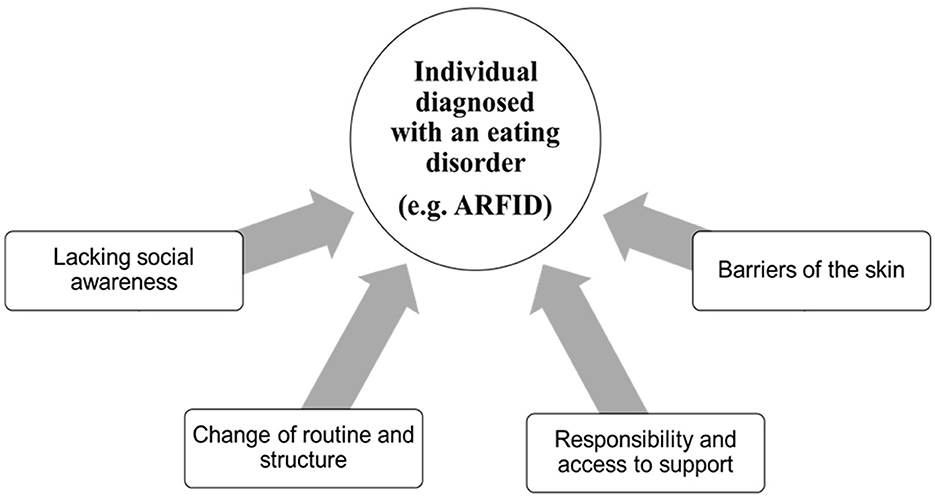

The main conclusions of this study emphasize the significance of unique experiences and subjective meanings supplied by the research participants following phenomenological principles rather than attempting to portray a single universal truth (Giorgi, 2009). The key themes of the data analysis ascertain how ARFID can be understood in relation to its impact on travel (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The thematic map that represents our research participants with an eating disorder (e.g., ARFID) in relation to its impact on travel.

First, according to the interviewees, a lack of public social awareness about ARFID is a significant barrier for them. This ignorance impedes research participant's ability to experience tourism in the pleasurable way they anticipate. All of the interviewees complained that no one understands their relationship with food. ARFID is a new and not well-known eating disorder; consequently, public social awareness is significantly low. For instance, one of our participants commented: “I don't believe they think it's a real thing” and “There's no awareness about it at all; not even my partner understands”. Many people diagnosed with this condition have suffered from it for some time without even knowing they have ARFID. For instance, one participant said,

“I've struggled with it for a long time, but there was never, like, any words or anything for it, and it was a relief to find out that I had something, and it wasn't just me being weird”. Another admitted, “I don't like labels, but it was a relief. Having that label”.

The lack of awareness also relates to how society defines a person with ARFID. Research participants complained that society stigmatizes their health condition and calls them fuzzy or picky eaters whose food choices are labeled “unhealthy”. For example, “They [wider society] just see it as being fussy or lazy”. According to some of our participants, society generally expects that eating whatever is put in front of you is polite. However, this expectation is a significant barrier to getting help for them because there is much anxiety around food and shame for picky eating behavior. For instance, one of our participants stated, “I think perceptions of picky eating are like probably the hardest thing to overcome”. Our research participants hope to see a change in society's perception that they are fussy eaters and to be understood to be those with ARFID.

Our research participants also explained that they are reluctant to explain their condition to fellow travelers as they often feel humiliated when explaining themselves, and they also do not want to be judged. For example, one said, “I was having a panic attack, like, at least once a day, mostly at every meal. And, like, then I'm thinking, or what are they thinking of me”. Notably, increasing public awareness can lead restaurants to adjust specifically to people who suffer from eating disorders. For example, one of our participants commented on how she wanted to see a change and envisioned that change. She explained, “Those menus will cater toward those who suffer and that society as a whole stops looking down on those who don't have vegetables or fruit on their plates”.

Second, according to the interviewees, sustaining daily routine and structure supports them. Research participants explained that they experience anxiety when traveling to new/foreign destinations as they rely on so-called “safe food” and may struggle to accept new cuisine. The participants in this study prefer to travel to destinations where the food is similar to their home country. For instance, one participant who is a carer of a person with ARFID shared:

“It's just a shame that we'd love to go to places like Japan, Sri Lanka or India, but we can't because the food is so different. So, we have to stick to the Western countries with food that is very similar”.

Furthermore, compared to everyday routine life, travel can involve physical activity. Such an experience can sometimes be draining for our research participants with an eating disorder if they cannot find their “safe food” and refill their energy after it. Our participants suggested that, compared to everyday life, during travel, they have to research if their “safe foods” are available at hotels and restaurants. For instance, one of our participants stated, “I always search up and try and find the menu first”. Furthermore, traveling to a country where a different language is spoken could be incredibly challenging for them. For instance, one of our participants shared her travel experience in France. Many French people speak some English, which helped her; nevertheless, communication was sometimes challenging, such as during dinner in a restaurant. In her words, “So, we're relying on my dad's high school friends to sort of translate. And I don't think I ate it”.

Third, according to the interviewees, they will likely have less of the family and professional support they need when traveling. Travel increases responsibility for themselves and brings challenges in accessing support. Our study findings suggest that family and loved ones are the best supporters for our research participants during travel. For instance, one of our participants referred to her family as her “safety net”. Family members understand the person's condition well, the diagnosis implications, and first-hand carer experience. For example, one said, “I'm pretty comfortable with my friends, but I wouldn't put the responsibility onto them. Whereas, with my family, I feel like I can”.

One of our participants shared her experiences of spending time in a foreign country. It was pretty isolating as she felt there was no one to tell and no one would understand her situation. In her words: “So that was probably, like, the biggest challenge, like, trying to cope with it all of my own”. Furthermore, when family members travel with our research participants, their responsibility increases compared to other families since carrying and supporting a person with ARFID is often a complex task. Therefore, ARFID penetrates all facets of life, and traveling is a psychologically challenging experience as it increases responsibility and makes it challenging to access support if needed.

Fourth, according to the interviewees, when traveling with a hidden disability or invisible impairment, skin becomes a boundary between what is internally experienced and what is externally seen (Gibbons, 2013). For instance, “Definitely trying to look like a normal eating person when in situations [where] we can't access our safe foods” was stressful. This complexity adds extra challenges for service providers in tourism when catering to this segment, and the following extracts from our participants further emphasize the imbalance between what is visible externally and the actual lived experience of ARFID. For example, as one of our participants suggested, “I ordered the baby food meal in Disneyland, but the cashier said you don't have a baby with you” and according to another participant who is a carer of a person with ARFID “It's not like a normal family. Just go to an order”.

Discussion and conclusion

All human beings have the equal right to direct and personal access to the exploration and enjoyment of its resources, and barriers should not be put in the way of this (Small and Harris, 2012). Tourism researchers have expressed interest in its broader societal benefits and have tried to figure out how to get the most out of it (Biddulph and Scheyvens, 2018). This brief report highlights the preliminary findings of the study of individuals with ARFID and their travel experiences. The study gives voices to tourists with hidden disabilities, including eating disorders, and advances tourism scholarship by uncovering what it means to be a tourist with ARFID. According to our participants, it would not be easy for them to participate in tourism until there is greater public social awareness of eating disorders, such as ARFID and ARFID is highly individualized, meaning that everyone is seen as different. Routine and structure are seen as important and essential to reduce feelings of uncertainty and anxiety for our research participants. Travel also changes one's routine and structure in life; consequently, our research participants face many unfamiliar encounters, such as being around new food, people, and environments.

In contrast, traveling alone increases personal responsibility and makes it difficult to access support other than by phone. Therefore, traveling alone can be challenging for people with ARFID. During travel, the appearance of having a healthy body means that outsiders cannot see that this person has an eating disorder. For example, our research participants suggest that they experience anxiety during overseas travel; outsiders cannot understand what they are going through because their condition is hidden.

Numerous research has looked at the idea of safety concerning travel (Angelin et al., 2014; Balaban et al., 2014; Seeman, 2016); nevertheless, there is still a sizable disparity in relation to ARFID sufferers. Our research participants highlighted that travel can exacerbate anxiety, which presents a challenge for tourism enterprises seeking to reduce their view of travel as hazardous by offering various travel products and services. Additionally, as there is a dearth of data in this area, more investigation is required to determine how individuals with eating disorders, including ARFID, assess travel hazards, make decisions about travel, and how these decisions affect their anxiety levels.

Accessibility is essentially about including persons with disabilities in tourism and society at large; it is a significant factor in the field of studies pertaining to inclusive tourist development (Gillovic and McIntosh, 2020). Findings also highlight that altering tourism language and symbols are essential for servicing travelers seeking inclusion in various hospitality environments. Future studies on understanding the lived experiences during travel can focus on the connection between disability advocacy and mental health activism to give voices to people with eating disorders. This study extends the existing knowledge that ineffectively captures the needs of people diagnosed with ARFID in the context of travel under the key themes of lacking social awareness, change of routine and structure, responsibility, and access to support and barriers to the skin. Based on the people we spoke to, these barriers could be lessened through better partnerships between clinicians, academics and tourism stakeholders in embedding “science and kindness” to decrease the stigma often associated with ARFID. For instance, research findings brought to our attention the importance of public awareness, consciousness and empathy toward people with ARFID and how important it is to create ARFID-friendly hotels and restaurants and perhaps include training on eating disorders in chefs' education and employees who are employed in the tourism and hospitality sector. This again relates to the broader issue of industry education for inclusivity and accessibility.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data includes sensitive information which may identify participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to dWRpdGhhQGhhaW5hbnUuZWR1LmNu.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Graduate and Research Affairs Office. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

UR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the research participants for their contribution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5, Vol. 10. American Psychiatric Association.

Angelin, M., Evengård, B., and Palmgren, H. (2014). Travel health advice: benefits, compliance, and outcome. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 46, 447–453. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2014.896030

Balaban, V., Warnock, E., Ramana Dhara, V., Jean-Louis, L. A., Sotir, M. J., and Kozarsky, P. (2014). Health risks, travel preparation, and illness among public health professionals during international travel. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 12, 349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.01.007

Biddulph, R., and Scheyvens, R. (2018). Introducing inclusive tourism. Tour. Geogr. 20, 583–588. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2018.1486880

Brennan, E., and Kulkarni, J. (2014). Travel advice for patients with psychotic disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 48, 687–687. doi: 10.1177/0004867413520051

Connell, J., and Page, S. J. (2019). Case study: Destination readiness for dementia-friendly visitor experiences: a scoping study. Tour. Manag. 70, 29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.05.013

Gibbons, R. (2013). Hypertextual self-scapes: crossing the barriers of the skin. 40th Anniv. Stud. Symb. Interact. 40, 15–42. doi: 10.1108/S0163-2396(2013)0000040005

Gillovic, B., and McIntosh, A. (2020). Accessibility and inclusive tourism development: current state and future agenda. Sustainability 12:9722. doi: 10.3390/su12229722

Giorgi, A. (2009). The Descriptive Phenomenological Method in Psychology: A Modified Husserlian Approach. Duquesne University Press.

McCabe, S., and Johnson, S. (2013). The happiness factor in tourism: subjective well-being and social tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 41, 42–65. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.001

McIntosh, A. J. (2020). The hidden side of travel: epilepsy and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 81:102856. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.102856

McKercher, B., and Darcy, S. (2018). Re-conceptualising barriers to travel by people with disabilities. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 26, 59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.01.003

Mostefa-Kara, L. (2021). The role of travel for people with an eating disorder is an optimal leisure experience. Eur. Psychiatry 64, 699–699. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.1851

Peláez-Fernández, M. A., Romero-Mesa, J., Franco-Paredes, K., and Extremera, N. (2022). The moderating role of emotional intelligence in the link between self-esteem and symptoms of eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 56, 778–782. doi: 10.1002/eat.23778

Ramanayake, U., Cockburn-Wootten, C., and McIntosh, A. J. (2022). The ‘MeBox' method and the emotional effects of chronic illness on travel. Tour. Geogr. 24, 412–434. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2019.1665094

Rebernik, N., Favero, P., and Bahillo, A. (2021). Using digital tools and ethnography for rethinking disability inclusive city design - Exploring material and immaterial dialogues. Disabil. Soc. 36, 952–977. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2020.1779035

Schmidt, C. (2016). Phenomenology: an experience of letting go and letting be. Waikato J. Educ. 11. doi: 10.15663/wje.v11i1.323

Seeman, M. V. (2016). Travel risks for those with serious mental illness. Int. J. Travel Med. Global Health 4, 76–81. doi: 10.21859/ijtmgh-040302

Small, J., and Harris, C. (2012). Obesity and tourism: rights and responsibilities. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 686–707. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.09.002

Keywords: eating disorders, travel, invisible disabilities, phenomenology, lived experiences, accessible tourism

Citation: Ramanayake U and Wengel Y (2024) Traveling with an eating disorder. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1395295. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1395295

Received: 03 March 2024; Accepted: 22 August 2024;

Published: 09 September 2024.

Edited by:

Anne Hardy, University of Tasmania, AustraliaReviewed by:

Rodney Caldicott, Hue University, VietnamTamara Young, The University of Newcastle, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Ramanayake and Wengel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yana Wengel, eWFuYS53ZW5nZWxAb3V0bG9vay5jb20=

Uditha Ramanayake

Uditha Ramanayake Yana Wengel

Yana Wengel