- 1Department of Social Science, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Ted Rogers School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON, Canada

The COVID-19 pandemic had transformative effects on the tourism sector at an unparalleled scale. With the rapid onset of unprecedented travel restrictions, tourists were abruptly confined to experiences in their regional surroundings that led to new and refreshed relationships with local destinations. This paper draws on qualitative interviews with small tourism businesses in two distinct but proximate nature-based destinations in Ontario, Canada and considers how they responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings are positioned within Holling's Adaptive Cycle to consider implications for ongoing resiliency planning for disturbances relating to climate change. Over a 2-year period (2020–2022), SMEs revealed that after an initially turbulent period they quickly adapted to the absence of international long-haul visitors by embracing a surge in domestic demand for nature-based, outdoor experiences. The paper contributes to the literature on tourism SMEs by connecting experiences of COVID-19 to resiliency planning for future predictable disturbances. Two critical lessons for enhancing destination resiliency are identified: engagement of regional tourism demand, and destination level leadership, through investment in infrastructure and partnerships, can both be harnessed to support SMEs and their communities in transitioning toward a more sustainable, resilient and climate-friendly tourism future. Given the growing demand for tourism businesses to transition away from environmentally harmful practices and a longstanding dependency on economic growth, these resources can help destinations enhance preparedness for future changes to tourism flows driven by decarbonization scenarios and increased climatic impacts.

1 Introduction

The concept of resiliency concerns the ability to cope with and adapt to challenging conditions, which became increasingly relevant for tourism through the COVID-19 pandemic (Iborra et al., 2020; Saad et al., 2021; Gianiodis et al., 2022). As the virus spread in early 2020, governments imposed unprecedented travel restrictions and tourism was drastically limited (UNWTO, 2021). In subsequent seasons, as restrictions were partially lifted, travelers sought safety and familiarity (Kock et al., 2020; Rogerson and Rogerson, 2021; Zamanzadeh et al., 2022) with demand returning in altered volumes and forms (UNWTO, 2020). Destinations broadly experienced a decline in international and long-haul visitors and an increase in domestic demand, with nature-based destinations faring better than urban areas (Falk et al., 2022). Tourism is largely made up of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Mair et al., 2016) who face many challenges that were exacerbated through the pandemic (Kukanja et al., 2022; Pongtanalert and Assarut, 2022). These challenges warrant special attention given the prevalence and unique attributes of SMEs that distinguish them from larger businesses (Hall et al., 2023).

The tourism system is vulnerable to many disturbances, such as the increasing frequency of climate-related events which are inspiring urgent calls to decarbonize (e.g., Dogru et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2019; Scott, 2021) and could bring substantial changes to tourism demand flows (Lenzen et al., 2018; Peeters and Papp, 2023). Climate change is already affecting the environmental conditions within which tourism experiences are offered, and demand may shift as consumer awareness and government action evolves. Part of the resiliency building process involves learning from the past (Cochrane, 2010; Hall et al., 2023; Prayag, 2023), and the pandemic provides a critical opportunity to review and identify transformative changes to prepare for the future (Prayag, 2020; Fan et al., 2023; Pröbstl-Haider et al., 2023).

Tourism scholars and practitioners have been debating the necessity and policy changes required to move an industry fixated on economic growth toward greener, sustainable, equitable, and resilient economic practices since the 1970s (Hall, 2015). The tourism industry has, however, largely remained on a growth-oriented, business-as-usual trajectory (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). In prioritizing this model of economic growth, the industry has failed to account for the role tourist activities play in driving biodiversity losses that exacerbate environmental and climate extremes that are pushing the earth system into a far less predictable state (Steffen et al., 2007). The COVID-19 pandemic evidently disrupted this sector-wide trajectory, forcing the industry to pursue a (temporary) realignment that involved less carbon-intensive practices. Many operators were forced to rapidly pivot away from international and long-haul demand toward local and regional visitors and, by extension, less carbon-intensive tourism alternatives (Prayag, 2020; Arbulú et al., 2021; Seyfi et al., 2023). This situation helped to refresh or establish relationships between local visitors and regional destinations, providing some optimism for acceptance of a necessary shift toward a more decarbonized tourism industry. This qualitative study therefore positions the pandemic as a poignant example of a system scale crisis for tourism; and one that forebodes of challenges the industry will confront as it faces intensifying climatic and environmental impacts, vulnerabilities, and risks (e.g., Hall, 2015; Scott et al., 2019; Scott, 2021; Gössling et al., 2023, 2024).

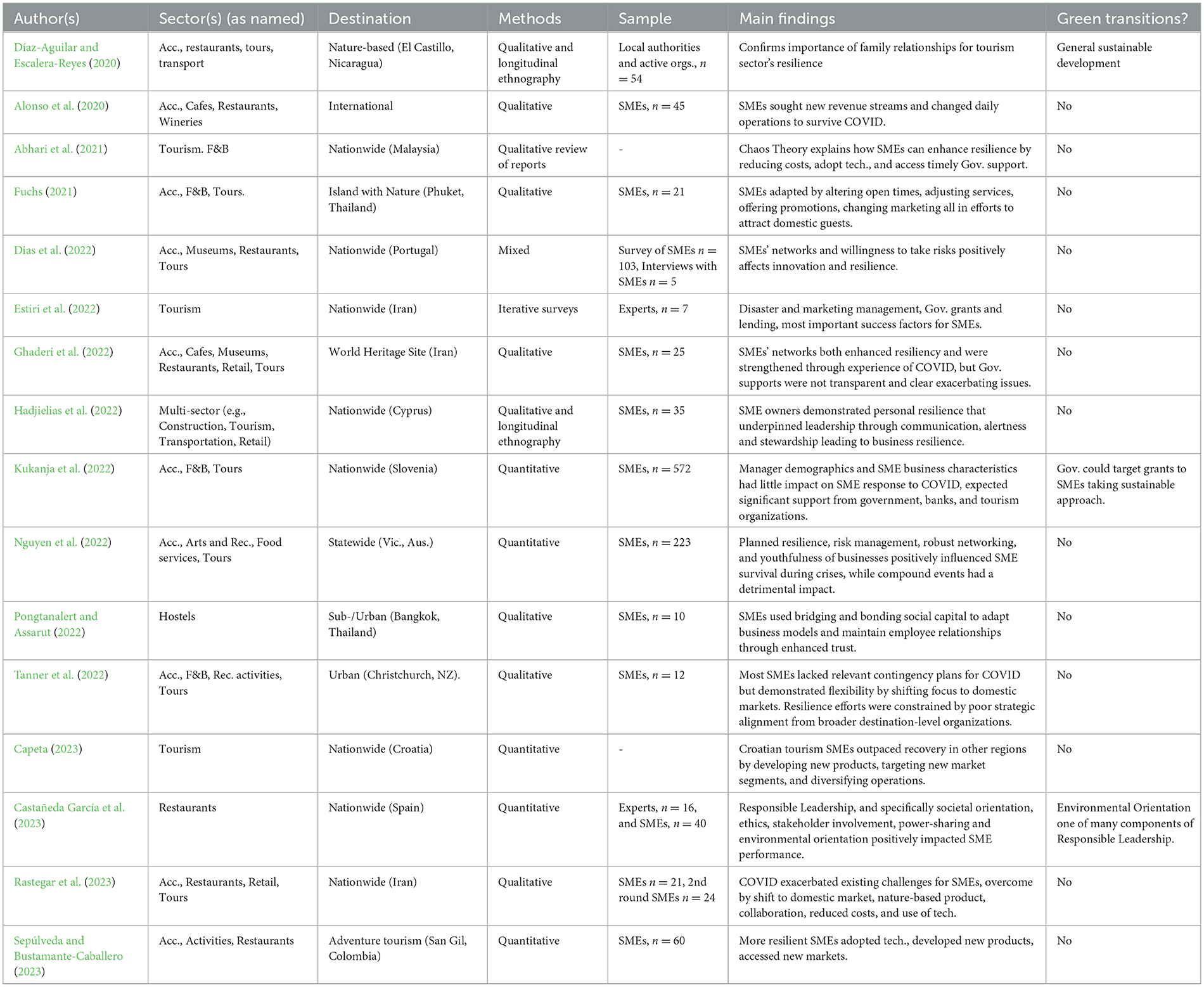

In spring and summer of 2022, semi-structured interviews were held with 20 participants representing tourism SMEs from two distinct yet connected nature-based destinations in Ontario, Canada. This study positions their experiences of COVID-19 within Holling's (2001) Adaptive Cycle and identifies a move toward decarbonization as a predictable future disturbance. Renewed relationships with local tourism markets, recognized as resilient sources of demand during the pandemic are thus considered as resources for destinations and SMEs to maintain and develop so as to be more easily remembered in preparation for future disturbances, including the multiscale impacts of climate change and the transition to a greener, decarbonized tourism system. While existing research has shed light on the experiences of tourism SMEs through the COVID-19 pandemic, it has predominantly focused on immediate survival tactics and resiliency in a broad sense (see Table 1). This paper responds to this literature gap by identifying critical resources and knowledge nature-based tourism SMEs developed during the pandemic that are more widely applicable to supporting pathways toward decarbonization, green transitions, and a more resilient local tourism economy.

2 Literature review

2.1 Resiliency and tourism

Resiliency is the ability of a system to recover from challenging conditions and external shocks (Holling, 2001; Becken, 2013; Amore et al., 2018; Iborra et al., 2020). Being resilient is not just bouncing back but adapting to the new environment by strategically adjusting and efficiently utilizing capabilities to maintain and improve functioning before, during, and after adversity (Prayag, 2023). Resiliency is relevant for tourism, which is vulnerable to disturbances in increasing frequency and magnitude (Amore et al., 2018; Hall et al., 2023; Prayag, 2023). Disturbances can be fast or slow, from an immediate crisis to incremental change (Becken, 2013; Amore et al., 2018), and can damage infrastructure, reduce visitation, affect available experiences, and harm the destination's reputation (Jiang et al., 2019; Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020). Further, with many connected components, the tourism system is subject to supply chain resiliency, as the collapse of one element affects another's ability to function successfully (Jiang et al., 2019).

Holling's (1973; 2001) seminal work informs much of the resiliency literature and his Adaptive Cycle is a “theoretical framework and process for understanding complex systems” (Holling, 2001, p. 391). The Adaptive Cycle explains how two separate functions happen: “[t]he first maximizes production and accumulation; the second maximizes invention and reassortment… [which] cannot be maximized simultaneously” (Holling, 2001, p. 395). The cycle has four stages: a system experiences a disturbance (release), reorganizes (reorganization), establishes new norms (exploitation), and settles into a new set of relationships and customs (conservation) that ultimately becomes too rigid and thus susceptible to a new disturbance. The Adaptive Cycle has been applied to tourism before. For example, Cochrane (2010) framed the 2004 Tsunami in Sri Lanka, as well as economic instability, bomb attacks, and changes to tourist visas in Indonesia as disturbances that led to new forms of development and tourism demand.

The Panarchy, as conceptualized by Holling (2001), describes the “hierarchical structure in which systems of nature… humans… and social ecological systems… are interlinked in never ending adaptive cycles of growth, accumulations, restructuring, and renewal” (p. 392). Prayag (2020) identifies three levels of the tourism system Panarchy: the microlevel, including employees, tourists, and residents; the mesolevel, including tourism organizations, businesses, and institutions; and the macrolevel that concerns the overall system and relationships among actors and communities. Within each level are sub-systems of formal and informal relationships and between different groups and stakeholders that influence policy and implementation (Amore et al., 2018).

By count, tourism businesses are almost entirely SMEs whose collective success affects community resiliency (Gianiodis et al., 2022), and thus deserve specific attention (Mair et al., 2016; Badoc-Gonzales et al., 2022). SMEs had already been experiencing challenges that were exacerbated by the pandemic, including limited financial capacity, reliance on suppliers, staffing pools, limited access to resources, and varied capacities (Mair et al., 2016; Prayag et al., 2019; Prayag, 2020, 2023; Saad et al., 2021; Gianiodis et al., 2022; Hadjielias et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2022; Hall et al., 2023). Resilient SMEs require ambidexterity (Iborra et al., 2020), the ability to be both efficient internally and adapt to the external environment. Additionally, SMEs need strategic consistency which refers to their capacity to make strategic choices when confronting stressful external events and can be informed and facilitated through networks and macro level support and guidance (Iborra et al., 2020). Supply chain resilience is also important for SMEs, as they are more reliant on partners for components of their product or service (Prayag, 2023). Although SMEs are flexible (Tanner et al., 2022), and can improve their own resiliency, they are more vulnerable to disturbances that larger organizations might absorb (Holling, 2001; Orchiston et al., 2016), such as economic and political crises (Becken, 2013).

Destination Management Organizations (DMOs), at the mesolevel of the Panarchy, can help SMEs by proactively predicting disturbances, and identifying, developing, and consolidating resources in preparation (Holling, 2001; Orchiston et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2019; Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020). DMOs can lead community efforts (Amore et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2019; Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020), guide strategic consistency (Iborra et al., 2020), and facilitate collaborative and trusting networks that efficiently share resources (Cochrane, 2010; Amore et al., 2018; Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020; Pham et al., 2021; Ghaderi et al., 2022; Gianiodis et al., 2022; Prayag, 2023). Resiliency planning must, however, consider and conceptualize the ideal state, which can mean diverging from a business-as-usual path that brings negative consequences for other parts of the community system, and develops resources and relationships that may become irrelevant in a changing macrolevel environment (Amore et al., 2018). Calls for the tourism system to transition from a business-as-usual trajectory of economic growth bring attention to the need for the industry to acknowledge and adapt to these inevitable new realities for its own survival while cultivating greater awareness of the role tourism plays as a significant driver of environmental degradation (e.g., Fontanari and Traskevich, 2021; Wendt et al., 2022) and climatic change (Lenzen et al., 2018; Peeters and Papp, 2023).

2.2 Climate change, resilience and green tourism transitions

While the tourism system faces numerous potential disturbances, “resilience building should be grounded in the response to the specific adversity” (Prayag, 2023, p. 515). Climate change is a particularly notable challenge (Scott and Gössling, 2022), fundamental to sustainable development more broadly (Becken and Loehr, 2022). The tourism system is often critiqued for its lack of awareness and preparedness relating to climate change (Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020; Badoc-Gonzales et al., 2022), despite many identified current and future impacts. For example, SMEs and destinations are facing increasingly extreme weather events that impact their capacity to survive (Skouloudis et al., 2020), as well as more gradual climatic shifts that affect experiences on offer and infrastructure required (Ma et al., 2021). Further, a changing climate holds the potential to affect mobility flows and demand as society moves away from the carbon intensive business-as-usual trajectory that is exacerbating climate-related impacts (Scott et al., 2019; Hall et al., 2023).

Despite a growing number of governments acknowledging the prominence of tourism's role in climate change (Scott et al., 2019), substantial action is required to meet greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) reduction targets consistent with the 2015 Paris Agreement (Becken, 2019; Scott et al., 2019). Tourism accounted for at least 8% of global GHG emissions in 2013, driven by long-haul aviation (Lenzen et al., 2018; Gössling et al., 2023). Tourism stakeholders that presume long-haul travel can progress unabated with new technology arriving to reduce emissions risk being too optimistic (Holden, 2013), with real change in mobility patterns needed (Gössling et al., 2024). Consequently, there are growing calls and actions to dissociate tourism growth from air travel. For example, short-haul flights have been banned in France where rail alternatives are available, and airport capacity growth in Amsterdam is now capped (Peeters and Papp, 2023). Peeters and Papp's (2023) pathway for tourism to decarbonise and meet emissions requirements calls for the proportion of trips taken globally by airplane to decline from 23% in 2019 to 13% in 2050, and air-ticket prices to rise by 200%. Further, short-haul trips should account for 82% of all trips in 2050 (up from 68% in 2019), and trips taken by cars should constitute 62% of all trips in 2050 (up from 49%) (Peeters and Papp, 2023). As climate change becomes increasingly apparent, and the cost of oil and sustainable fuel rises, social pressure will shift (Mkono and Hughes, 2020) leading to government actions and changes making tourism flows more local (Peeters and Papp, 2023).

The post-COVID-19 moment presents an opportunity to consider how implications of the (recent) past can help to confront these current and future challenges. Strategies that simply revert to pre-COVID systems may not only be inequitable (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020; Hall et al., 2023), but also increase the likelihood and negative consequences of climate-related disturbances (Jiang et al., 2019; Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020). Many have called for degrowth (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020; Fan et al., 2023) and a greening of the tourism economy (Reddy and Wilkes, 2015). Others have identified tourist practices that (re)emerged during COVID-19 that can support such green transitions, such as the continued engagement of regional tourists seeking nature-based experiences following their renewed appreciation and prioritization of such outdoor recreation (Wu et al., 2022; Espiner et al., 2023; Power et al., 2023). Domestic markets are less volatile, generate fewer carbon emissions, and can foster local cultural and social connections (Lück and Seeler, 2021; Woyo, 2021), making them a possible foundation for a more sustainable and resilient tourism system (Arbulú et al., 2021). Ultimately, the resources and relationships nature-based destinations and SMEs developed through COVID-19 could be easily remembered to prepare for the next release phase that potentially restricts long-haul travel.

Table 1 summarizes journal articles that have focused on tourism and/or hospitality SMEs, COVID-19 and resilience. The summary of main findings reveals a limited focus on nature-based destinations (Díaz-Aguilar and Escalera-Reyes, 2020; Fuchs, 2021; Sepúlveda and Bustamante-Caballero, 2023), as well as a paucity of studies that consider how tourism SMEs' experienced COVID-19 with implications for transitions beyond the pandemic toward a greener economy and the decarbonization of tourism. For example, Díaz-Aguilar and Escalera-Reyes (2020) discuss the importance of tourism in supporting the sustainability of the natural environment, Kukanja et al. (2022) recommend that government supports for tourism SMEs require or incentivize sustainable practices, and Castañeda García et al. (2023) identify “Environmental Orientation” as one of several attributes that distinguished resilient restaurant owners from others. By connecting the experiences of nature-based SMEs during COVID-19 to the decarbonization and greening of tourism, this study responds to this knowledge gap. Further, it underscores the importance of learning from past disturbances and predicting future challenges for resiliency planning.

3 Background and methods

Before the sample and methods are explained, the background of the regions is first sketched out, positioning the era leading up to COVID-19 as the conservation phase of Holling's Adaptive Cycle (Holling, 2001).

3.1 Ontario's “near north” and the pre-COVID conservation phase

During the conservation period of the Adaptive Cycle, connections and relationships are established, stabilize, and resources such as information and partnerships develop through trust and routine, becoming increasingly entrenched (Holling, 2001). Holling (2001) suggests that eventually a system's adaptability plateaus to a point of rigidity, and it “becomes an accident waiting to happen” (p. 394).

Leading up to the pandemic, the tourism system globally experienced decades-long growth. In Ontario, 2019 overnight visitation (including domestic and international visitors) was 2.0% higher than 2004 (after the 2003 SARS virus caused significant declines). International demand (excluding the U.S.) however increased by 94.3% over the same period, and although representing only 7.6% of visitors accounted for 27.0% of visitor spending in 2019 (Ontario Government, 2023a). The tourism system had become progressively reliant on long-haul demand and growth, with relationships between SMEs, destinations, tourists, and other suppliers well established.

The sample for this study is taken from two neighboring regions situated in Ontario's near North (Grimwood et al., 2019): Muskoka and Almaguin Highlands. Muskoka, with a population of around 67,000 (Statistics Canada, 2021a), is 150km north of Toronto, and has been an iconic wilderness destination since colonialism in the late nineteenth century (Jasen, 1995). As Jasen (1995) writes:

no part of Ontario was more thoroughly and widely affected by the growth of wilderness tourism and the therapeutic holiday during this period than the region of Muskoka… Tourists enjoyed believing that here was a true primeval wilderness, not far from civilization but very real nonetheless (p. 115).

The region's wilderness, conveniently accessible by rail (Jasen, 1995; Watson, 2022), positioned Muskoka as an instant-north destination for urban Torontonians seeking “back-to-nature” holidays to recover from the health impacts of industrialization (Jasen, 1995; Watson, 2022), and eventually became established as an iconic destination for other Canadian and international travelers (Jasen, 1995; Watson, 2022).

Almaguin Highlands, directly north of Muskoka, developed in its current form after settlers, who arrived in the late nineteenth century, erected campsites and homesteads along the Magnetawan River where they worked in the logging industry (Taim, 1998). A legacy of these early settlement patterns is a scattering of small, amalgamated municipalities that make up Almaguin Highlands today. With an estimated population of 13,000 (Frangione, 2021), this area has been less economically dependent on tourism than Muskoka, and primarily attracts domestic visitors traveling for cottages, camping, fishing, snowmobiling, all-terrain vehicles, and water recreation (Taim, 1998; Almaguin Community Economic Development, 2023). As the Almaguin Highlands Chamber of Commerce's (2023) website states:

While the Almaguin Highlands does not have the developed tourism infrastructure of some other popular areas, it is precisely this sense of discovering new things that is part of the region's unique charm. Almaguin is a place to seek adventure and new experience, and hide from the crowds and fast pace found elsewhere.

This contrast between an iconic destination in Muskoka, and the lesser known Almaguin Highlands, offers a useful departure point for analysis of responses to the pandemic (Lück and Seeler, 2021).

These two regions are part of a broader destination represented by a Regional Tourism Organization (RTO) (Explorers' Edge., 2023). This RTO covers a much larger area that includes an estimated 870 tourism-related businesses of whom 88% employ <20 people (Ontario Government, 2023b). In 2019, this RTO area received ~3 million overnight visitors, dropping to 2.7 million in 2021 (Ontario Government, 2023b). Hotel occupancy returned to 2019 levels (53.8%) in 2022 (54.2%) after dropping to a low of 40.5% in 2020, however, media reports suggested that Muskoka fared well during the pandemic in comparison to other provincial destinations (e.g., Krause, 2022). While the majority (96%) of visitors to the RTO in 2019 were from Ontario, and specifically the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) – with a population of 6.2 million (Statistics Canada, 2021b) – out-of-province visitors contributed 15% of total spending (Ontario Government, 2023b). In summary, these two sub-regions offer distinct but connected contexts making them informative cases for considering the experiences of tourism SMEs in nature-based destinations and their experiences through COVID-19.

3.2 Sample and data collection

First, a guide from the RTO's consumer website (Explorers' Edge., 2023) was scanned for operators in the Muskoka and Almaguin Highlands regions listed under the Stay (i.e., accommodations) and Do (i.e., activities) categories. The list was narrowed to only operators promoting experiences deemed natural and outdoors. For example, operators listed as Stays offering cottages, cabins and yurts were included, while large hotels and resorts were excluded. Similarly, under Dos, operators promoting outdoor experiences including treetop trekking, cycling, ATV and self-guided tours were included. This resulted in a list of 58 operators who were emailed an invitation to participate.

Between April and June 2022, 17 interviews were conducted with 20 participants, a sample size comparable to other relevant studies (e.g., Becken, 2013; Dahles and Susilowati, 2015; Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020; Fuchs, 2021; Lück and Seeler, 2021; Ghaderi et al., 2022; Pongtanalert and Assarut, 2022; Tanner et al., 2022). The study received ethics approval from the authors' respective institutions, and the interviews were conducted on Zoom due to COVID-19 protocols. Most participants were tourism operators in Muskoka (n = 9) and Almaguin Highlands (n = 9), predominantly owner-operated or micro businesses (Gianiodis et al., 2022), with two interviewees representing regional organizations relating to tourism. Both authors attended all meetings which lasted ~1 h. Bryman's (2016) semi-structured approach to interviewing was followed, where thematic questions informed by the Adaptive Cycle (Holling, 2001) were asked in an open-ended, conversational format. Participants were first asked to reflect on the immediate impacts of COVID-19 and how these responses evolved over time. Participants were then asked to respond to a set of broader questions about tourism, sustainability, climate change and the future of local tourism in their region. Audio recordings were transcribed, and the material organized into thematic clusters to identify broad patterns and differences in the experiences of tourism stakeholders from the two regions in relation to Holling's (2001) Adaptive Cycle by repeatedly and iteratively discussing the themes informed by literature.

4 Findings

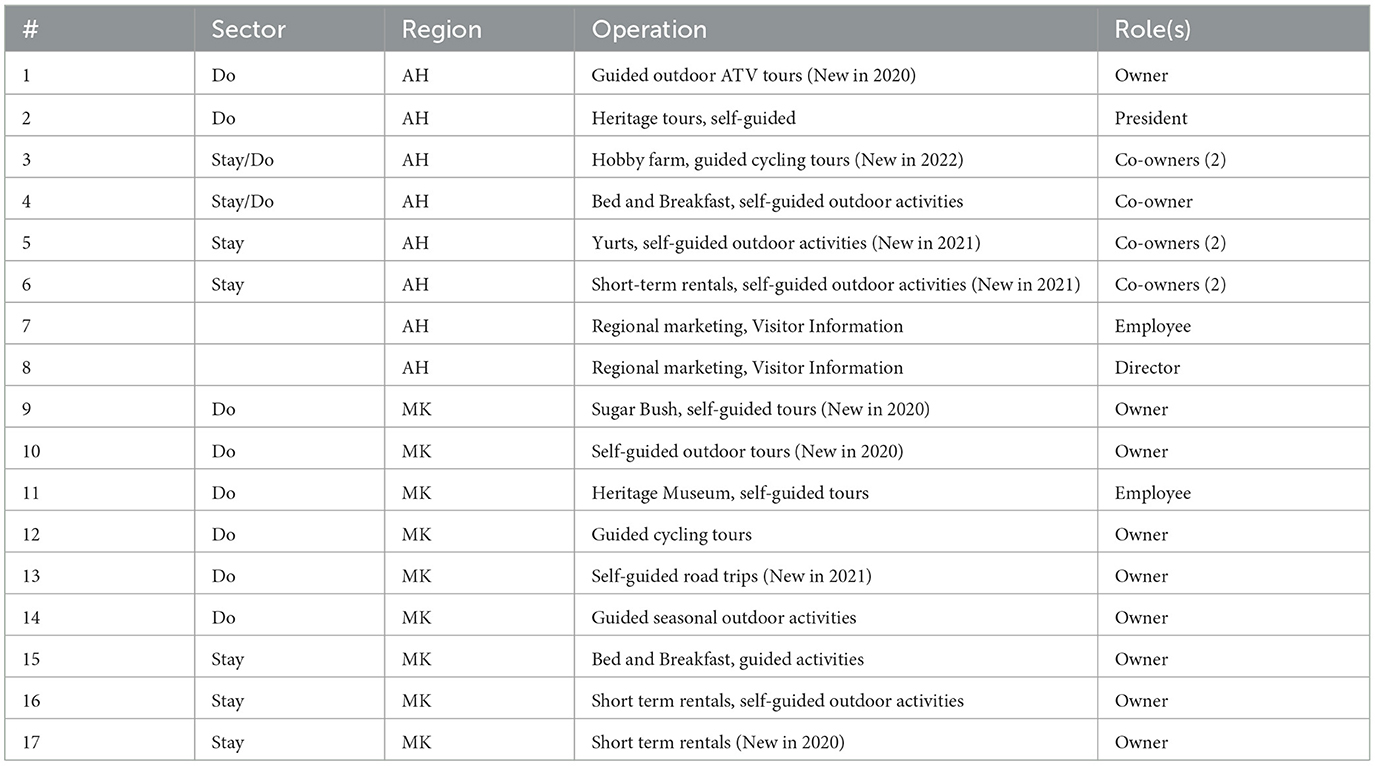

Table 2 lists participants along with their sector (Do or Stay), region (Almaguin or Muskoka), type of operation (e.g., cycling tours), and role (e.g., Owner). Findings are presented in a structure mirroring the four phases of Holling's (2001) Adaptive Cycle, first with a synthesis of literature that reflects tourism SMEs' experiences during that period, followed by themes drawn from participant interviews. Those who shared similar viewpoints in relation to specific themes are highlighted by numbers in brackets.

4.1 Release: COVID-19 and system collapse

The release phase of the cycle is “triggered by agents of disturbance” (p. 394), creating an “inherently unpredictable” (Holling, 2001, p. 395) environment. Accrued capitals in terms of resources, practices, opportunities, and knowledge shared through networks and relationships, collapse and move into a state of flux. COVID-19 was a substantial disturbance, causing travel restrictions and changes in tourist motivations, an event and immediacy that most tourism businesses were unprepared for (Tanner et al., 2022), with existing relationships in the supply chain collapsing causing distress and uncertainty (Prayag, 2020).

Participants consistently described the arrival of the pandemic in spring 2020, and the collapse of the tourism system, as a very difficult period. Widespread uncertainty defined this moment, with many concerned for their businesses. For example, one new business owner described this time as a “major setback” (3), delaying their launch date, leading to revenue losses. After learning all international bookings they relied upon had been canceled, another interviewee described “being in limbo and not knowing when we would be back open, [and] not knowing what being back open would look like” (4). This same participant noted revenues for 2020 were down “nearly 30% compared to 2019” (4), with another recalling being “35% down” (11).

4.2 Reorganization: making sense of the new reality

The ensuing reorganization phase begins quickly thereafter. Actors experiment and innovate within this new reality, with resiliency demonstrated by those who identify opportunities from the new situation (Dahles and Susilowati, 2015; Castañeda García et al., 2023). As mobility and social gathering restrictions started to lift, destinations and SMEs reorganized (Fontanari and Traskevich, 2021; Badoc-Gonzales et al., 2022; Seyfi et al., 2023), with demand surging for outdoor experiences in natural areas that offered well-being (Rogerson and Rogerson, 2021; Zamanzadeh et al., 2022) and accessibility by personal vehicle within the tourists' own jurisdiction (Craig, 2021; Jeon and Yang, 2021; Fan et al., 2023; Pröbstl-Haider et al., 2023). Successful SMEs were willing to take risks (Dias et al., 2022), pivoted their focus toward local visitors (Fuchs, 2021; Tanner et al., 2022; Capeta, 2023; Rastegar et al., 2023), sought new revenue streams (Alonso et al., 2020), invested in employee relationships, and networked with other SMEs and related organizations (e.g., Badoc-Gonzales et al., 2022; Dias et al., 2022; Ghaderi et al., 2022; Kukanja et al., 2022; Pongtanalert and Assarut, 2022). Timely, flexible, and easy to access government supports were helpful for those who received them (Abhari et al., 2021; Kukanja et al., 2022), and sorely missed by those who did not (Ghaderi et al., 2022; Rastegar et al., 2023).

After the initial shock, participants shared their experiences of adjusting, or reorganizing, to the new and changing reality. Initially, dealing with trip cancellations, modifying rebooking policies, and pivoting from large to small groups were common experiences (1, 12, 14). The required changes to daily operations and unpredictability became increasingly “mentally taxing” (4), making larger concerns difficult to manage. One participant explained how they would usually sell their accommodation packaged with provincial park tickets, but new policies meant visitors had to pre-book themselves, reducing the operator's control of their visitors' experience (4). Accessing government resources created to ease the economic shock was described as a difficult and frustrating process, as the seasonality of operations created obstacles in securing support, and many lacked the capacity to navigate the process (2, 6, 7, 8, 11). Several operators described new or rising costs including PPE and cleaning products (4, 6, 8), and building and contracting services (3, 17) that for some meant delaying major investments and upgrading (3, 4, 6). Others mentioned challenges finding and accommodating staff (6, 16, 17), with some adapting or continuing without external labor (9, 17). In summary, the pandemic brought uncertainty, an increase in processes and costs, and a stress on mental and financial wellbeing.

4.3 Exploitation: (re)discovering the “near north”

The next phase is exploitation, where “connectedness and stability increase and capital is accumulated” (Holling, 2001, p. 394). Domestic travelers who pre-pandemic had often been sidelined by increased long-haul demand, were encouraged to appreciate local landscapes and culture, substituting for lost international visitation (Abhari et al., 2021; Lück and Seeler, 2021; Dias et al., 2022; Ghaderi et al., 2022; Pongtanalert and Assarut, 2022; Wendt et al., 2022; Rastegar et al., 2023; Sepúlveda and Bustamante-Caballero, 2023).

As restrictions eased in the spring and summer of 2021, participants received an influx of visitors from within Ontario. Interviewees described adaptations to meet and capitalize on this new demand. As one explained, “what the pandemic caused was a great rediscovery of Northern Ontario and the wilderness that is out there” (8) by GTA visitors (1, 6). One owner opened their ATV operation earlier than planned after they “realized how crucial it was… to give people in the community and people in Ontario somewhere to go” (1). Another new operator felt that increased demand for outdoor glamping accommodations reflected a desire to escape and rehabilitate from the demands of living and working through the pandemic (5). Some had repeat visits from people who “hadn't stayed with us for 10 years” (4) and were reconnecting with the region, while others attracted new visitors unfamiliar with this part of the province (9, 14). Visitors with limited or non-existent experience wanted to participate in recreational activities (1, 12, 14, 16), and positive reference was made to “New Canadians” or immigrants (10, 14, 15, 16). These new visitors, despite living in relative proximity, were discovering the region and even nature experiences for the first time, needing guidance and instruction (4, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16). For example, one accommodation owner recounted:

The uncle put two little kids in the canoe and jumped in and figured he could just do it... [But] we taught them how to canoe and how to sit in a canoe and everything... We have families and they've never sat around a campfire at night, right? But they want to do it so much because they know it's this Canadian thing (16).

Many participants mentioned already receiving repeat visits from customers who visited for the first time during the pandemic, people who without the pandemic may not have visited, but had established a positive relationship worth maintaining into the future (1, 6, 11, 16). This new demand caused “an explosion of development and economic activity in the [Almaguin Highlands] area” (8) with a “new influx of people in the area” (2) that generated social and economic demands, including busier shops and more traffic on roads and waterways. Despite mostly positive experiences, several interviewees spoke of new challenges relating to people visiting for hedonic reasons who behaved inappropriately in the natural environment (1, 4, 10, 14, 15, 16). Others expressed concerns about the impacts of this rapid growth in tourism from new domestic visitors who appeared not to appreciate or were naïve on how to act in this environment. For example, they described increased boat traffic from visitors with limited experience, knowledge or etiquette, more traffic on roads, overflowing landfills, and litter on trails and in waterways (2, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). For some, these concerns had direct impacts on their business while others expressed general concern about the impacts on the whole region.

4.4 Envisioning the conservation phase: continued domestic demand?

Participants in this study spoke about their medium and longer-term outlook, and many revealed transformations to their business models that may endure. New and refreshed relationships with local demand during the pandemic was common, consistent with literature from other destinations (e.g., Fuchs, 2021; Capeta, 2023; Rastegar et al., 2023), but several participants also expressed hope and optimism that domestic visitors would remain important beyond COVID-19 as a more stable and easily accessible market.

Participants spoke of maintaining changes to their services, promotions, and infrastructure developed through the pandemic in order to continue engaging this domestic market. New visitor groups brought new expectations which led some to upgrade infrastructure such as Wi-Fi (4) or room capacity (16, 17). Some suggested that guidance, interpretation, and services that developed organically for new visitors would be integrated into their ongoing practices (1, 8, 14, 15, 16). For example, one participant explained how pre-COVID-19 their business targeted avid international cyclists who brought their own equipment. With demand from a more localized, less experienced market they acquired rental bikes and created itineraries for families to take shorter rides, which was anticipated to remain due to the investment and relationships established (12). Another participant who ran a sugar bush (maple syrup producer) developed self-guided activities to engage the increasing number of visitors seeking experiences which would be kept as permanent fixtures (9). An accommodation owner, who bought as the pandemic started, explained that they were transitioning from accommodating shorter week-long stays as initially planned to seasonal stays:

We're slowly phasing out the transient traffic because we're just trying to build a community of people who all know each other… We do have help [staff], but no one kind of full-time here… and we found with the seasonal program, with the cottages and the RV sites, it's a lot…. [In our] first year [2020], we were just thrown into it… So we're getting last-minute calls every single weekend where we are fully booked… and we're running, running, running. (17)

The combined pressure of changing demand patterns from regional visitors looking for short breaks, and labor shortages, transformed their original business model. The unavailability of labor was a substantial issue noted by other interviewees (5, 6, 16), and participant 17's challenge exemplifies how many services offered were informed by the fact that having staff was “just too complicated” (9). Several explained changes to promotional messaging that targeted these new local markets in an effort to sustain these relationships into the future (1, 5, 12). Another pointed to increased expenditures on outdoor recreational equipment, such as RVs and camping gear made by Ontarians during COVID-19 (Farooqui, 2021), which should maintain domestic visitation as people seek a return on these investments (8). Although local demand was expected to wane as international travel re-opened, many anticipated that the relationships they had established would remain (1, 3, 8, 9, 14).

Participants shared some concerns with continued high demand. In Almaguin Highlands, some who appreciated the increased business noted their region lacked adequate infrastructure to provide visitors a full and diverse experience, nor to deal with the consequences of more tourism (5, 6, 7, 8). The dilemma of increased visitation, viewed as beneficial toward the goal of economic development, concurrently brought challenges and consequences to affordability and the environment. As one participant explained:

[Almaguin] is underdeveloped compared to Muskoka, and Muskoka is really getting priced out of range for a lot of recreation... For sure, more people are heading further north… The challenge I think with more people coming up here is having enough infrastructure for them… restaurants open and close like a whiplash. There are [only] a few eateries, I could send people to that are reliably open (4).

4.5 Preparing for the next disturbance: a changing climate

As a new variance of the adaptive cycle begins it is crucial for the tourism system to remember the “potential that has been accumulated and stored” (Holling, 2001, p. 398) through COVID-19 in preparation for the next disturbance. When asked about future challenges climate change was often referenced. Changing and unpredictable weather patterns were a major concern (1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 17) including disruptive climate impacts such as hotter summers (4), declining snow (5, 8), heavy winds and frequent power outages (3), shoreline erosion (10), unprecedented water levels (17), and an unpredictable maple syrup season (9) that were already affecting the ability of these operators to deliver visitor experiences. One interviewee captured these wider concerns, stating that:

climate change is definitely going to be a problem going forward… Ten years ago… maybe once or twice in a summer, we'd have warm nights. We are now seeing heat waves where it doesn't cool off at night… That is an issue… so now I have to look at putting in air conditioning in the next couple years (4).

Diminishing snow was another concern (5, 8), with one participant explaining that in winter “there are 3 months of boom and 2 months of very quiet, so when those boom periods are taken away [through limited snowfall], it is extremely detrimental... If the snow goes away, yes it kills our business” (5). New domestic demand was being contemplated as a substitution to visitors seeking winter conditions (5). Another mentioned new procedures for extreme weather events, including “safety protocols for guides to keep guests safe while they are out on excursion… GPS tracking and cell service on the trail… [and] rent[ing] outfits to prepare them [tourists] for the weather” (1). Many shared actual and anticipated costs to deal with climate change (3, 4, 8, 17). For example, making a new building “as energy efficient as possible” to respond to frequent power outages caused by high winds (3), and spending “$30,000 on a new dock system” because of “the unpredictable water levels affecting boaters” (17). A lack of government support for climate resiliency was identified (4, 8, 17), placing an “undue burden on tourism businesses” (8) to shoulder these costs on their own.

Many spoke proudly of practices they identified as environmentally and climate-friendly (3, 4, 5, 10, 12, 14). One operator described promoting “self-powered activities” in a region saturated with “motor sports or motor vehicle recreation, snowmobilers and ATVs…. That's not at all our market... We've always promoted snowshoeing, hiking, self-powered stuff, and that's partly for the environment” (4). Another operator maintained that “everything we do is human powered,” including backcountry tours that focus on land, environmental stewardship and the changing climate (14). One business owner stated that “our goal is to be able, if we walk away from this, we can take it away and we haven't had an impact on the land” (5). Others articulated a more complicated vision of environmental stewardship and, while viewing their own business practices as sustainable, pointed to external factors such as overtourism, lack of provincial infrastructure and resources, or a dependency on other environmentally harmful local businesses and services, that were limiting their own ambitions to maintain climate-friendly operations (3, 12, 14).

5 Discussion

Although the two regions shared some experiences, there were differences. In Muskoka, operators seemed more familiar with the benefits and pitfalls associated with a booming tourism sector. With established wilderness narratives (Jasen, 1995) and tourism infrastructure (Watson, 2022), Muskoka was more connected to and reliant upon international visitors. While Almaguin may have registered with some Ontarians for specific outdoor recreation (Taim, 1998), it took pandemic travel restrictions to elevate domestic awareness and generate unprecedented visitor demand.

The self-selective nature of participation in this study is also worth noting. While COVID-19 was devastating for many tourism businesses (Prayag, 2023), it revealed opportunities to those who could see opportunities in the collapse of previous systems (Dias et al., 2022; Hadjielias et al., 2022). Eight participants had opened businesses just prior to or during the pandemic (see Table 2), demonstrating ambidexterity and flexibility, perhaps due to the lack of pre-existing established relationships that saw other young businesses fare better (Iborra et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2022), and adapting within their capacities to show strong resilience (Gianiodis et al., 2022); SMEs who did not adapt are therefore likely under-represented. For example, despite labor challenges, most participants expressed optimism about adapting to be less reliant on external labor (Badoc-Gonzales et al., 2022; Dias et al., 2022), which can increase costs and responsibilities that create rigidities (Becken, 2013). This has implications for the types and scope of experiences on offer to visitors, and to the community in terms of employment and economic opportunities that requires further consideration. Future research might consider how characteristics and mindsets of SMEs can make them more adaptive and resilient (Gianiodis et al., 2022; Hadjielias et al., 2022; Tanner et al., 2022; Prayag, 2023).

Findings reveal that COVID-19 was an immediate and fast-moving disturbance (Becken, 2013; Amore et al., 2018) that caused a collapse of the existing tourism system Panarchy (Prayag, 2020). This, in turn, released structures and resources into a new phase of reorganization that provided participants with opportunities to exploit the new reality. As the cycle arguably enters a new conservation phase, it is vital that resiliency planning learns from the past and develops resources from this last disturbance that can be more easily remembered in the next release phase (Holling, 2001; Cochrane, 2010; Hall et al., 2023; Prayag, 2023). Further, the experiences of these SMEs during the pandemic carry lessons for resiliency planning that align with increasingly urgent demands for decarbonization and a greening of the tourism system. Destinations need to engage an important yet difficult discourse of how to balance neo-liberal desires for economic growth with future concerns (Amore et al., 2018; Prayag, 2023). Given the high likelihood of continued climate-related disturbances, including incremental and extreme weather patterns (e.g., Ma et al., 2021), as well as changing flows of demand due to decarbonization (e.g., Becken, 2019), this paper now develops two main themes for further discussion: (i) the need for collaboration between nature-based tourism actors across the Panarchy, and (ii) the continued engagement of a diverse domestic demand.

5.1 Destination led collaboration

As mesolevel agencies in the tourism system (Prayag, 2020), DMOs and other government and community institutions can help scaffold a backbone for strategic consistency (Iborra et al., 2020; Tanner et al., 2022), upon which SMEs can build their own resiliency planning activities (Amore et al., 2018; Kukanja et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2022). The availability of other interdependent tourism services, such as provincial park permits and lack of restaurants, impacts the visitor experience (Dias et al., 2022), highlighting the importance of supply chain resiliency to support organizational resiliency (Prayag, 2023). The ability of SMEs to function are affected by institutional collaboration too. One participant provided a more specific example of how cycling infrastructure differed drastically across municipal jurisdictions within the same region (12), affecting the quality of visitor experience for a high-yield market. The challenge of bringing stakeholders and policymakers together to make cohesive investments was well beyond this individual operator's scope. This is exemplary of the difficulties SMEs confront when relying upon other services and infrastructure to make their own business work; challenges that are very difficult to overcome without structural support (Li et al., 2022). Creating an environment where the influence, engagement and shared social capital of varied stakeholders can be integrated and leveraged is crucial to the metagovernance of a destination, including opportunities to critically engage policy makers (Amore and Hall, 2016; Becken and Loehr, 2022). Many study participants complained about the bureaucratic nature and ineffectiveness of government supports that were intended to provide relief during the pandemic. However, government supports and grants can be delivered effectively to shift destinations to more resilient pathways (Estiri et al., 2022), and crafted to require, incentivize, or reward SMEs that develop in certain sustainable directions (Kukanja et al., 2022), including engagement of local tourism demand in the pursuit of resiliency. Efforts and frameworks that identify gaps in the visitor experience, and foster collaboration and networking between stakeholders to provide enhanced visitor experiences should improve resiliency (Amore et al., 2018).

5.2 Engagement of diverse domestic demand to support green transitions

Tactically, DMOs can provide strategic direction through the continued engagement of diverse domestic demand to build resiliency. All participants experienced increased domestic demand, consistent with the literature on SMEs during COVID-19 (Arbulú et al., 2021; Craig, 2021; Jeon and Yang, 2021; Lück and Seeler, 2021; Tanner et al., 2022; Pröbstl-Haider et al., 2023), specifically visitors seeking escape and recovery from pandemic urban life (Jeon and Yang, 2021; Rogerson and Rogerson, 2021). Operators, in turn, shifted marketing and services to meet this demand from new domestic groups (Fontanari and Traskevich, 2021; Badoc-Gonzales et al., 2022; Ghaderi et al., 2022; Sepúlveda and Bustamante-Caballero, 2023), often consistent with a long-established wilderness idyll narrative of Ontario's “near North” (Jasen, 1995). Additionally, for SMEs who offered activities affected by a precious natural system exacerbated by climate change (e.g., snow-based operations), a local market with varied interests could become a reasonable substitute (Becken, 2013). Building upon these new and refreshed relationships with diverse domestic markets established through the pandemic thus offers a mechanism for developing resiliency against future challenges.

Although domestic visitors may spend less per visitor, destinations must decide what resiliency should entail given the predictability of future disturbances (Gianiodis et al., 2022; Seyfi et al., 2023). Domestic demand is more resilient in times of crisis (Woyo, 2021), and brings other benefits including higher lifetime spending, less economic leakage, participation in more varied activities, and less seasonal demand, which can result in subtle but important community benefits (Arbulú et al., 2021). An added effect of SMEs turning toward domestic visitors are carbon emissions reductions that can align with growing calls for decarbonization across the tourist system (e.g., Becken, 2019; Peeters and Papp, 2023).

DMOs and governments can “provide orientation and coordination” (Amore et al., 2018, p. 243), and strategic consistency (Filimonau and De Coteau, 2020; Iborra et al., 2020; Gianiodis et al., 2022), by investing in marketing and product development that helps meet diverse domestic visitor expectations. SMEs can then leverage these efforts in their own planning. DMOs can identify varied domestic visitor groups based on motivations, demographics, travel parties, and budget. They can then work with SMEs to develop and promote experiences that appeal to these domestic visitor groups. Another possibility is to consider what experiences these groups seek internationally, and on long-haul trips, and then find ways to offer local substitutions (Volgger et al., 2021). Developing different packaging of experiences can offer repeat visitors new activities and options. The provision of information and equipment (e.g., bike rentals, self-guided tours, boating instruction/etiquette) can help to attract and maintain relationships with new local visitor groups.

6 Conclusion

This study has explored the experiences of SMEs in a nature-based destination during COVID-19 and considered implications for future resiliency planning. Findings show that after an immediate collapse of the system, caused by mobility restrictions and traveler motivations, SMEs reorganized; exploiting the new reality by shifting their communications, processes, and services to new and varied domestic demand. By applying Holling's (2001) Adaptive Cycle, remembering experiences of the past can be used to support and enhance future preparedness. This study is not a criticism of specific organizations relating to this region, and there are indeed many initiatives in progress that relate to these findings (e.g., Explorers' Edge., 2024). Rather, this research supports the idea that tourism is meaningful for community development (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). This requires challenging conversations to predict difficult future scenarios relating to climate change and the decarbonization of travel, as well as planning for the likelihood of such events. This must be steered by destination level institutions through collaboration with lower level actors in the Panarchy, including nature-based tourism SMEs.

There are certainly limitations to this study, particularly the nature of the sample which is not truly representative due to the self-selection process. However, by situating the experiences and perspectives of these nature-based tourism operators within the Adaptive Cycle (Holling, 2001) framework, the study sheds light on lessons from the transformative impacts of COVID-19 that can be remembered and carried forward by communities in similar contexts in order to better prepare for future crises and transformations. Another limitation of this research is scope, which centers on nature-based outdoor tourism in the North American context, and thereby ignores other regions of the world (Li et al., 2022).

This research has responded to calls for tourism research to seize the post-COVID-19 opportunity to reflect, reposition, and reprioritise what tourism means for communities (Lew et al., 2020), and offer critical analyses and theoretical reflections beyond descriptive summaries of immediate impacts and prescriptions to return to normal (Yang et al., 2021). There is theoretical and practical value not just in describing immediate reactions to COVID-19, but in positioning them in a broader evolutionary context to learn, predict, and develop best practices for responding to future challenges (Kock et al., 2020). This study has responded to this call by offering a snapshot in time, that looks back on 2-years of turbulence, before shifting toward insights this moment provides for future resiliency planning. The research has practical implications for tourism SMEs offering nature-based experiences, but also for the communities where they are located, in particular those destinations in proximity to large urban areas. Future research should further consider the metagovernance of destinations, and the opportunities for varied stakeholders to influence the direction and implementation of formal policy and informal collaborations toward resiliency against decarbonization (Amore and Hall, 2016; Becken and Loehr, 2022). Further, in scenarios where decarbonization and climate change affect travel patterns and experiences, resources must be provided for destinations of diverse typologies to consider what that future will look like, and to make advanced preparations through enhanced resiliency. As Lück and Seeler (2021) argue, “[d]omestic tourists need to be given a piece of their homeland back for re-exploration beyond the post-COVID-19 recovery stages” (p.17) as part of resiliency building strategies. This paper echoes such calls for further investment and research into the potential of domestic tourism to improve SME and community resiliency (Fuchs, 2021).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Office of Research Ethics, at York University and Toronto Metropolitan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abhari, S., Jalali, A., Jaafar, M., and Tajaddini, R. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on small businesses in tourism and hospitality industry in Malaysia. J. Res. Market. Entrepr.. 24, 75–91. doi: 10.1108/JRME-07-2020-0091

Almaguin Community Economic Development (2023). Tourism FAQ. Available online at: https://explorealmaguin.ca/community-and-events/tourism-faq (accessed January 15, 2024).

Almaguin Highlands Chamber of Commerce (2023). About Almaguin. Available online at: https://ahchamber.ca/about-almaguin/

Alonso, A. D., Kok, S. K., Bressan, A., O'Shea, M., Sakellarios, N., Koresis, A., Solis, M. A. B., and Santoni, L. J. (2020). COVID-19, aftermath, impacts, and hospitality firms: an international perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 91:102654. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102654

Amore, A., and Hall, C. M. (2016). From governance to meta-governance in tourism? Re-incorporating politics, interests and values in the analysis of tourism governance. Tour. Recr. Res. 41, 109–122. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2016.1151162

Amore, A., Prayag, G., and Hall, C. M. (2018). Conceptualizing destination resilience from a multilevel perspective. Tour. Rev. Int. 22, 235–250. doi: 10.3727/154427218X15369305779010

Arbulú, I., Razumova, M., Rey-Maquieira, J., and Sastre, F. (2021). Can domestic tourism relieve the COVID-19 tourist industry crisis? The case of Spain. J. Dest. Market. Manage. 20:100568. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100568

Badoc-Gonzales, B. P., Mandigma, M. B. S., and Tan, J. J. (2022). SME resilience as a catalyst for tourism destinations: a literature review. J. Glob. Entr. Res. 12, 23–44. doi: 10.1007/s40497-022-00309-1

Becken, S. (2013). Developing a framework for assessing resilience of tourism sub-systems to climatic factors. Annal. Tour. Res. 43, 506–528. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.002

Becken, S. (2019). Decarbonising tourism: Mission impossible? Tour. Recr. Res. 44, 419–433. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2019.1598042

Becken, S., and Loehr, J. (2022). Tourism governance and enabling drivers for intensifying climate action. J. Sust. Tour. 11, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2022.2032099

Capeta, I. (2023). Resistance of small entrepreneurship in croatia tourism to global health crisis. UTMS J. Econ. 14, 122–133.

Castañeda García, J. A., Rey Pino, J. M., Elkhwesky, Z., and Salem, I. E. (2023). Identifying core “responsible leadership” practices for SME restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 35, 419–450. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2021-1194

Cochrane, J. (2010). The sphere of tourism resilience. Tour. Recr. Res. 35, 173–185. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2010.11081632

Craig, C. A. (2021). Camping, glamping, and coronavirus in the United States. Annal. Tour. Res. 89:103071. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103071

Dahles, H., and Susilowati, T. P. (2015). Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annal. Tour. Res. 51, 34–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.01.002

Dias, Á. L., Cunha, I., Pereira, L., Costa, R. L., and Gonçalves, R. (2022). Revisiting small-and medium-sized enterprises' innovation and resilience during COVID-19. J. Open Innov. Technol. Market Compl. 8:11. doi: 10.3390/joitmc8010011

Díaz-Aguilar, A. L., and Escalera-Reyes, J. (2020). Family relations and socio-ecological resilience within locally-based tourism: the case of El Castillo (Nicaragua). Sustainability 12:5886. doi: 10.3390/su12155886

Dogru, T., Marchio, E. A., Bulut, U., and Suess, C. (2019). Climate change: vulnerability and resilience of tourism and the entire economy. Tour. Manage. 72, 292–305. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.12.010

Espiner, N., Degarege, G., Stewart, E. J., and Espiner, S. (2023). From backyards to the backcountry: exploring outdoor recreation coping strategies and experiences during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand. J. Outdoor Recr. Tour. 41, 100497–100497. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2022.100497

Estiri, M., Dahooie, J. H., and Skare, M. (2022). COVID-19 crisis and resilience of tourism SMEs: a focus on policy responses. Econ. Res. Ekonomska IstraŽivanja 35, 5556–5580. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2022.2032245

Explorers' Edge. (2023). Regions. Available online at: https://thegreatcanadianwilderness.com/regions/ (accessed January 15, 2024).

Explorers' Edge. (2024). Regenerative Strategy and BOPs. Available online at: https://explorersedge.ca/strategy-bops/ (accessed February 5, 2024).

Falk, M., Hagsten, E., and Lin, X. (2022). Uneven domestic tourism demand in times of pandemic. Tour. Econ. 29, 596–611. doi: 10.1177/13548166211059409

Fan, X., Lu, J., Qiu, M., and Xiao, X. (2023). Changes in travel behaviors and intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery period: a case study of China. J. Outdoor Recr. Tour. 41, 100522–100522. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2022.100522

Farooqui, S. (2021). Outdoor Retailers Struggle to Keep Up With Demand for Camping Equipment Ahead of Second COVID-19 Summer. Globe and Mail. Available online at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-outdoor-retailers-struggle-to-keep-up-with-demand-for-camping/ (accessed January 15, 2024).

Filimonau, V., and De Coteau, D. (2020). Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM2). Int. J. Tour. Res. 22, 202–222. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2329

Fontanari, M., and Traskevich, A. (2021). Consensus and diversity regarding overtourism: the Delphi-study and derived assumptions for the post-COVID-19 time. Int. J. Tour. Policy 11, 161–187. doi: 10.1504/IJTP.2021.117375

Frangione, R. (2021). Almaguin Communities Inch Closer to Belonging to an Ontario Health Team. The Toronto Star. Available online at: https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2021/03/11/almaguin-communities-inch-closer-to-belonging-to-an-ontario-health-team.html (accessed March 11, 2021).

Fuchs, K. (2021). How are small businesses adapting to the new normal? Examining tourism development amid COVID-19 in Phuket. Curr. Issues Tour. 24, 3420–3424. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2021.1942439

Ghaderi, Z., Aslani, E., Beal, L., Farashah, M. D. P., and Ghasemi, M. (2022). Crisis-resilience of small-scale tourism businesses in the pandemic era: the case of Yazd World Heritage Site, Iran. Tour. Recr. Res. 17, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2022.2119519

Gianiodis, P., Lee, S. H., Zhao, H., Foo, M. D., and Audretsch, D. (2022). Lessons on small business resilience. J. Small Bus. Manage. 60, 1029–1040. doi: 10.1080/00472778.2022.2084099

Gössling, S., Balas, M., Mayer, M., and Sun, Y. Y. (2023). A review of tourism and climate change mitigation: The scales, scopes, stakeholders and strategies of carbon management. Tour. Manage. 95:104681. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104681

Gössling, S., Vogler, R., and Humpe, A. Chen, N. (2024). National tourism organizations and climate change. Tour. Geograph. 22, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2024.2332368

Grimwood, B., Muldoon, M., and Stevens, Z. (2019). Settler colonialism, Indigenous cultures, and the promotional landscapes of tourism in Ontario, Canada's ‘near North'. J. Herit. Tour. 14, 233–248. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2018.1527845

Hadjielias, E., Christofi, M., and Tarba, S. (2022). Contextualizing small business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from small business owner-managers. Small Bus. Econ. 59, 1351–1380. doi: 10.1007/s11187-021-00588-0

Hall, C. M. (2015). “Economic greenwash: On the absurdity of tourism and green growth,” in Tourism in the Green Economy, eds. M. V. Reddy, and K. Wilkes (London: Routledge), 361–380.

Hall, C. M., Safonov, A., and Naderi Koupaei, S. (2023). Resilience in hospitality and tourism: Issues, synthesis and agenda. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 35, 347–368. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2021-1428

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geograph. 22, 610–623. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

Holden, A. (2013). Tourism and the green economy: A place for an environmental ethic? Tour. Recr. Res. 38, 3–13. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2013.11081725

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4, 1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

Holling, C. S. (2001). Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems 4, 390–405. doi: 10.1007/s10021-001-0101-5

Iborra, M., Safón, V., and Dolz, C. (2020). What explains the resilience of SMEs? Ambidexterity capability and strategic consistency. Long Range Plann. 53:101947. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2019.101947

Jasen, P. (1995). Wild Things: Nature, Culture and Tourism in Ontario, 1790-1914. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Jeon, C. Y., and Yang, H. W. (2021). The structural changes of a local tourism network: Comparison of before and after COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 24, 3324–3338. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2021.1874890

Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B. W., and Verreynne, M. L. (2019). Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: a dynamic capabilities view. Int. J. Tour. Res. 21, 882–900. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2312

Kock, F., Nørfelt, A., Josiassen, A., Assaf, A., and Tsionas, M. (2020). Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: the evolutionary tourism paradigm. Annal. Tour. Res. 85:103053. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103053

Krause, K. (2022). Muskoka Sees Boost in Tourism Amid Provincial Timeline Report. CTV News. Available online at: https://barrie.ctvnews.ca/muskoka-sees-boost-in-tourism-amid-provincial-timeline-report-1.6191935 (accessed January 15, 2024).

Kukanja, M., Planinc, T., and Sikošek, M. (2022). Crisis management practices in tourism SMEs during COVID-19-an integrated model based on SMEs and managers' characteristics. Tour. Int. Interdis. J. 70, 113–126. doi: 10.37741/t.70.1.8

Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., and Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 522–528. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

Lew, A., Cheer, J., Haywood, M., Brouder, P., and Salazar, N. (2020). Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020. Tour. Geograph. 22, 455–466. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1770326

Li, L., Tao, Z., and Lu, L. (2022). Understanding differences in rural tourism recovery: a critical study from the mobility perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 26, 2452–2466. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2022.2088337

Lück, M., and Seeler, S. (2021). Understanding domestic tourists to support COVID-19 recovery strategies: the case of Aotearoa New Zealand. J. Resp. Tour. Manage. 1, 10–20. doi: 10.47263/JRTM.01-02-02

Ma, S., Craig, C., Scott, D., and Feng, S. (2021). Global climate resources for camping and nature-based tourism. Tour. Hosp. 2, 365–379. doi: 10.3390/tourhosp2040024

Mair, J., Ritchie, B., and Walters, G. (2016). Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: a narrative review. Curr. Issues Tour. 19, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.932758

Mkono, M., and Hughes, K. (2020). Eco-guilt and eco-shame in tourism consumption contexts: understanding the triggers and responses. J. Sust. Tour. 28, 1223–1244. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1730388

Nguyen, V. K., Pyke, J., Gamage, A., and de Lacy, T. Lindsay-Smith, G. (2022). Factors influencing business recovery from compound disasters: evidence from Australian micro and small tourism businesses. J. Hosp. Tour. Manage. 53, 1–9.

Ontario Government (2023a). Historical Statistics. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/page/tourism-research-statistics#section-4 (accessed February 5, 2024).

Ontario Government (2023b). Region 12: Muskoka, Parry Sound and Algonquin Park: Regional Tourism Profile. Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/document/tourism-regions/region-12-muskoka-parry-sound-and-algonquin-park (accessed February 5, 2024).

Orchiston, C., Prayag, G., and Brown, C. (2016). Organizational resilience in the tourism sector. Annal. Tour. Res. 56, 145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.002

Peeters, P., and Papp, B. (2023). Envisioning Tourism in 2030 and Beyond. The Changing Shape of Tourism in a Decarbonising World. Bristol: The Travel Foundation.

Pham, L. D., Coles, T., Ritchie, B., and Wang, J. (2021). Building business resilience to external shocks: conceptualising the role of social networks to small tourism and hospitality businesses. J. Hosp. Tour. Manage. 48, 210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.06.012

Pongtanalert, K., and Assarut, N. (2022). Entrepreneur mindset, social capital and adaptive capacity for tourism SME resilience and transformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 14:12675. doi: 10.3390/su141912675

Power, D., Lambe, B., and Murphy, N. (2023). Trends in recreational walking trail usage in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for practice. J. Outdoor Recr. Tour. 41, 100477. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2021.100477

Prayag, G. (2020). Time for reset? COVID-19 and tourism resilience. Tour. Rev. Int. 24, 179–184. doi: 10.3727/154427220X15926147793595

Prayag, G. (2023). Tourism resilience in the ‘new normal': Beyond jingle and jangle fallacies? J. Hosp. Tour. Manage. 54, 513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.02.006

Prayag, G., Spector, S., Orchiston, C., and Chowdhury, M. (2019). Psychological resilience, organizational resilience and life satisfaction in tourism firms: insights from the Canterbury earthquakes. Curr. Issues Tour. 23, 1216–1233. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2019.1607832

Pröbstl-Haider, U., Gugerell, K., and Maruthaveeran, S. (2023). COVID-19 and outdoor recreation – Lessons learned? Introduction to the special issue on Outdoor recreation and COVID-19: Its effects on people, parks and landscapes. J. Outdoor Recr. Tour. 41:100583. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2022.100583

Rastegar, R., Seyfi, S., and Shahi, T. (2023). Tourism SMEs' resilience strategies amidst the COVID-19 crisis: the story of survival. Tour. Recr. Res. 22, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2023.2233073

Rogerson, C., and Rogerson, J. M. (2021). COVID-19 and changing tourism demand: research review and policy implications for South Africa. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leisure 10, 1–21. doi: 10.46222/ajhtl.19770720-83

Saad, M. H., Hagelaar, G., van der Velde, G., and Omta, S. W. F. (2021). Conceptualization of SMEs' business resilience: a systematic literature review. Cogent Bus. Manage. 8:347. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2021.1938347

Scott, D. (2021). Sustainable tourism and the grand challenge of climate change. Sustainability 13:1966. doi: 10.3390/su13041966

Scott, D., and Gössling, S. (2022). A review of research into tourism and climate change. Annal. Tour. Res. 95:103409. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2022.103409

Scott, D., Hall, C. M., and Gössling, S. (2019). Global tourism vulnerability to climate change. Annal. Tour. Res. 77, 49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.05.007

Sepúlveda, W. S., and Bustamante-Caballero, S. P. (2023). Segmentation and factors associated with the resilience of touristic SMEs: results from Colombia. Tour. Hosp. Res. 27:146735842311659. doi: 10.1177/146735842311659

Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., and Saarinen, J. (2023). Rethinking sustainable substitution between domestic and international tourism: a policy thought experiment. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leisure Events 11, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2022.2100410

Skouloudis, A., Tsalis, T., Nikolaou, I., Evangelinos, K., and Leal Filho, W. (2020). Small and medium-sized enterprises, organizational resilience capacity and flash floods: insights from a literature review. Sustainability 12:7437. doi: 10.3390/su12187437

Statistics Canada (2021a). Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population: Muskoka Census Division. Available online at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=EandSearchText=muskokaandDGUIDlist=2021A00033544andGENDERlist=1,2,3andSTATISTIClist=1andHEADERlist=0 (accessed January 15, 2024).

Statistics Canada (2021b). Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population: Toronto Census Metropolitan Area. Available online at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=EandSearchText=torontoandDGUIDlist=2021S0503535andGENDERlist=1,2,3andSTATISTIClist=1andHEADERlist=0 (accessed January 15, 2024).

Steffen, W., Crutzen, P., and McNeill, J. (2007). The anthropocene: Are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature? Ambio J. Hum. Environ. 36, 614–621. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[614:TAAHNO]2.0.CO;2

Tanner, S., Prayag, G., and Kuntz, J. C. (2022). Psychological capital, social capital and organizational resilience: a Herringbone Model perspective. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 78:103149. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103149

UNWTO (2020). More Than 50% of Global Destinations are Easing Travel Restrictions- but Caution Remains. Available online at: https://www.unwto.org/more-than-50-of-global-destinations-are-easing-travel-restrictions-but-caution-remains (accessed February 14, 2024).

UNWTO (2021). COVID-19 and Tourism 2020: A Year in Review. Available online at: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-12/2020_Year_in_Review_0.pdf (accessed February 14, 2024).

Volgger, M., Taplin, R., and Aebli, A. (2021). Recovery of domestic tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: an experimental comparison of interventions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manage. 48, 428–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.07.015

Watson, A. (2022). Making Muskoka: Tourism, Rural Identity and Sustainability, 1870-1920. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Wendt, M., Sæþórsdóttir, A. D., and Waage, E. R. (2022). A break from overtourism: domestic tourists reclaiming nature during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Hosp. 3, 788–802. doi: 10.3390/tourhosp3030048

Woyo, E. (2021). “The sustainability of using domestic tourism as a post-COVID-19 recovery strategy in a distressed destination,” in Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021, eds. W. Wörndl, C. Koo, and J. L. Stienmetz (Cham: Springer), 476–489.

Wu, D. C., Cao, C., Liu, W., and Chen, J. L. (2022). Impact of domestic tourism on economy under COVID-19: the perspective of tourism satellite accounts. Annal. Tour. Res. Emp. Insights 3:100055. doi: 10.1016/j.annale.2022.100055

Yang, Y., Zhang, C. X., and Rickly, J. M. (2021). A review of early COVID-19 research in tourism: launching the annals of tourism research's curated collection on coronavirus and tourism. Annal. Tour. Res. 91:103313. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103313

Keywords: nature-based tourism, SMEs, resilience, COVID-19, climate change, local tourism

Citation: Tegelberg M and Griffin T (2024) Remembering for resilience: nature-based tourism, COVID-19, and green transitions. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1392566. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1392566

Received: 27 February 2024; Accepted: 22 April 2024;

Published: 13 May 2024.

Edited by:

Nikos Ntounis, Manchester Metropolitan University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Kyriaki Glyptou, Leeds Beckett University, United KingdomMesbahuddin Chowdhury, University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Copyright © 2024 Tegelberg and Griffin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew Tegelberg, bXRlZ2VsQHlvcmt1LmNh

Matthew Tegelberg

Matthew Tegelberg Tom Griffin

Tom Griffin