94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

COMMUNITY CASE STUDY article

Front. Sustain. Tour., 09 May 2024

Sec. Social Impact of Tourism

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsut.2024.1384962

This article is part of the Research TopicTourism Development, Sustainability, and InclusionView all 7 articles

Globally, tourism is advocated as a development tool with the potential to uplift socioeconomic conditions for marginalized populations and contribute to biodiversity conservation. The expectation is that the tourism model of development can bring about positive social changes in diverse communities by broadening livelihood opportunities and concurrently preserving crucial ecosystems, which are regarded as valuable assets in the tourism sector. We investigated Wayanad in the Western Ghats of India, challenging the notion of “tourism for development.” We examined the socio-ecological features of the region, the evolution of tourism and sustainable tourism, and the implications across various sectors. The research employed an empirical approach grounded in the critical examination of socio-ecological systems for tourism governance and sustainability. The data were obtained through in-depth interviews conducted in Wayanad and a review of the relevant literature. The results reveal that despite the prevalent and persuasive arguments favoring tourism, there are extensive multi-sectoral implications in tourism development that negatively affect both the environment and people at large. These impacts include the erosion of agrobiodiversity-linked traditional Adivasi lifestyles, the displacement of local communities, the encroachment of tourism projects into forests and increased human–animal conflicts, the absence of social security measures for marginalized communities, a decline in traditional livelihood options, and an overreliance on the tourism industry and the private sector. These discernible impacts have pushed the fragile region further into a socio-ecological imbalance. Tourism development in ecologically delicate areas should take into account socio-ecological impacts because a region's culture and nature are key components of its attractiveness as a tourist destination. Large-scale landscape planning should involve the perspectives of various stakeholders, including both direct and indirect participants who could be influenced by tourism. The marginalization of Adivasi communities that maintain the region's ecological integrity is unproductive for both the economic and regional development interests of tourism.

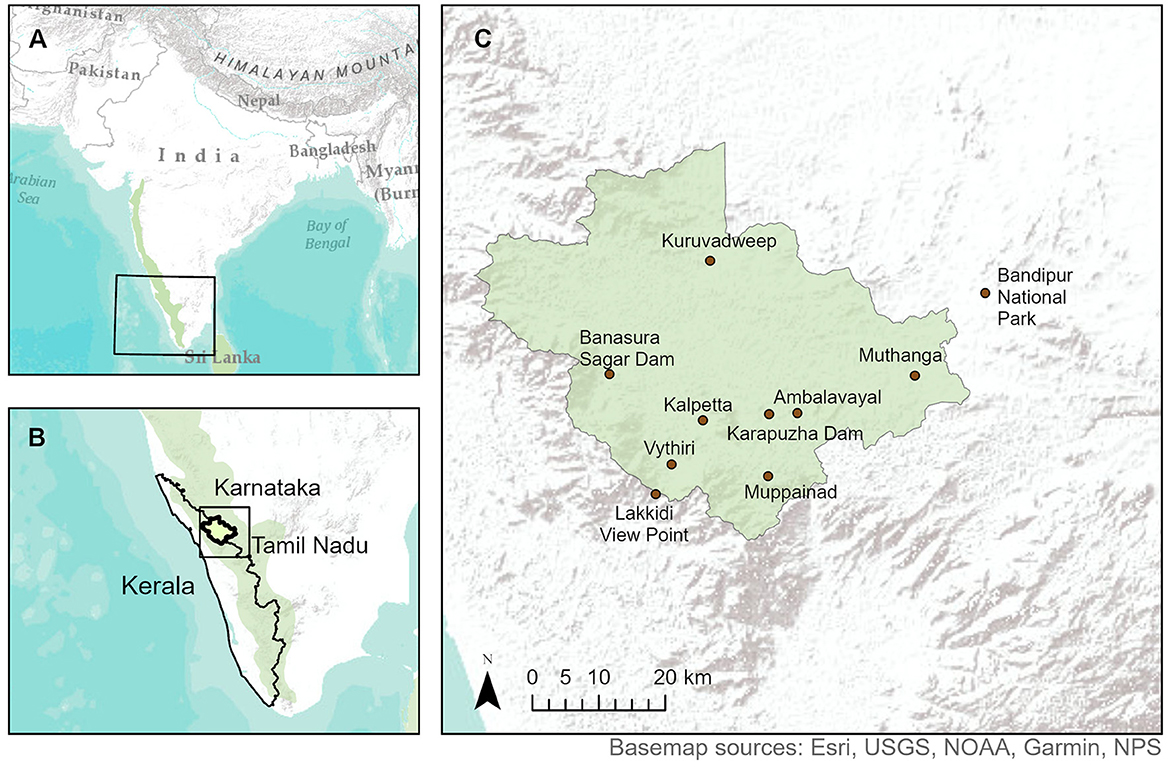

The Western Ghats are of international significance for preserving high biodiversity, being representative of a montane forest ecosystem in a tropical monsoon climate and a platform for evolutional processes; thus, they were designated a World Heritage Site in 2012 (UNESCO, 2012). This mountain range occupies an area that is 1,600 km long from north to south and 140,000 km2 in total area (Figure 1A). Currently, it is under threat from livestock grazing, coffee and tea plantations, hydroelectric power development, and tourism (IUCN, 2020).

Figure 1. Map of the study site. (A) Map of India showing the Western Ghats ecoregion; (B) specific location of Wayanad district in Kerala, surrounded bordered by Karnataka to the north and Tamil Nadu to the east; and (C) locations of the sites in and near Wayanad that are mentioned in the text (Created by the authors in ArcGIS Pro 3.2, in collaboration with Rakuno Gakuen University).

The Western Ghats are also rich in indigenous heritage. The indigenous people of India are known as the Adivasi (also referred to as “Scheduled Tribes”) and mainly occupy the hills of the Western Ghats and the low-lying regions along the boundaries with the southern states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. Based on the most recent available census data (Government of India, 2011), the Adivasi population in Kerala is between 400,000 and 500,000 (<2% of the state's total population), scattered around different districts.

Wayanad, located in the northeastern region of Kerala (Figure 1B), is thought to have derived its name from vayal, meaning paddy fields, and naadu, meaning land, or from vananadu, meaning land of forests (Kumar and Prajeesh, 2016). About one-third of the total Adivasi population of Kerala lives in Wayanad, where 45% of the Adivasi belong to the Paniya people (Government of India, 2011; Chandrika and Nandakumar, 2015). The generational ramifications of bonded labor and the wide prevalence of sickle cell anemia make them extremely vulnerable to poverty and health issues (Kumar, 2005; Devika and Rajasree, 2008; Colah et al., 2015). Wayanad is the poorest district of Kerala (NFHS-4, 2015-16).

The transformation of an ailing rural-agrarian region such as Wayanad into a tourism hot spot is often justified on the basis of expected economic growth. In this regard, Kerala introduced the concept of “responsible tourism” to render tourism inclusive and effective for sustainable development. The concept owes its origin to the Cape Town Declaration of 20021 and the Kerala Declaration of 20082 (Burrai et al., 2019). Unfortunately, the trade-off between tourism development and the loss of biodiversity has not been sufficiently discussed (Vitousek et al., 1997). Despite what we observe in the field, the social impact of tourism on weaker sections of society and their alienation from tourism development are seriously underrepresented in the tourism literature. Increasing tourism activities and urbanization aggravate this trend, leading to irrevocable ecological imbalances and frequent overlooking of the role of indigenous peoples in protecting biodiversity and ecosystems (Jurgens et al., 2024; Levis et al., 2024). This approach is counterproductive to sustainable development, as conservation is more effective when indigenous peoples and local communities are involved (Dawson et al., 2021).

Against this backdrop, the objective of this article is to assess the socio-ecological impact of tourism development in Wayanad and highlight the ever-increasing necessity of linking tourism with biodiversity conservation to minimize impacts and trade-offs. Tourism is being promoted in Kerala under multiple labels, such as responsible tourism and ecotourism, expressing the aim of achieving sustainable development. The present work addresses the following three questions:

1. What socio-ecological characteristics are at the root of the precarious situation of Wayanad?

2. How were tourism and sustainable tourism introduced into Wayanad?

3. What roles has tourism played in fostering multi-sectoral linkages for the development of the region, with special reference to the Adivasi population?

Our aim is to further the current understanding of sustainable tourism and its socio-ecological impacts in the Western Ghats.

The key idea suggested by Bramwell and Lane (2011) and Heslinga et al. (2017) of using sustainable tourism governance to minimize the negative effects of tourism and make practical progress for the environment and society was explored in this empirical research. This study adopted a qualitative case approach reflecting the major multi-sectoral implications of tourism development. Semistructured interviews were conducted with 20 individuals (Table 1) using predefined initial questions. We asked the participants questions regarding (1) the agrarian and migratory past and its linkage to the emergence of tourism, (2) factors influencing tourism development, (3) the implications of tourism in multiple sectors, and finally, (4) identifying the criticality of the synergy between biodiversity conservation and tourism as a way forward in policy formulations. Initial contacts were made with the support of the Bangalore-based research organization EQUATIONS, followed by data collection via the snowball sampling method. The key resource contacts included members of the Adivasi community, elected representatives, Kerala state tourism department and government officials, civil society, and social, political, and environmental activists. The fieldwork was carried out during 2016–2017 and updated during 2022–2023 in the Wayanad district in Kerala. The interviews were conducted in the local language of Malayalam, transcribed, and translated into English. Interviews lasted from 30 min to 1 h. We added participant and non-participant observations of the growing urbanization and the effects of tourism activities in Wayanad, along with an analysis of secondary and gray literature, such as governmental and Non-governmental Organization (NGO) reports, to provide a more comprehensive context for our analysis. We used pseudonyms to protect the identities of the resource contacts.

Wayand has a long history of internal migration from central Kerala. Gowders3 from Karnataka (a neighboring state) also settled here and built Jain temples all around the district. The first wave of internal migration started in the 1940s but slowed in the late 1970s (Varghese, 2009, 2016; GoK, 2011). It was the high fertility of the land that attracted immigrants (Jacob, 2006; Kjosavik and Shanmugaratnam, 2007). The migrant population, seeking to establish themselves in agriculture, immediately engaged in widespread deforestation. This was further fueled by food shortages, impoverishment of the peasantry, rising prices for essential commodities, and discord between the middle and ruling classes. Additionally, government support under the banner of the “Grow More Food” campaign of the 1940s legitimized deforestation for cultivation purposes (Jacob, 2006), leading to large-scale land struggles. As one such migrant resident, who was also a government official, posited:

We have imposed our way of life on the Adivasi through force and superiority. The interesting thing is our models of development are not at all sustainable, but their knowledge systems and practices were completely centered on ecological balance. (Krishna, interview, 2016)

However, by the late 1960s, signs began to show that policy decisions to adopt an economically viable route were having socio-ecological impacts on the Adivasi communities. Many settlers had addicted the Adivasi to alcohol and tobacco to exploit their labor for cultivation in the adverse environment with its wild animals, diseases (e.g., malaria), and rough terrain (Kumar, 2005; Veena, 2016). Thus, their equitable life in tune with nature was heavily impacted.

Nevertheless, land-grabbing continued unabated. There was a sevenfold increase in the number of landowners, from 3,549 in 1976 to 22,491 in 2010. The Adivasi were pushed toward the fringes, and landlessness severely impacted their lives and traditional livelihood options (Bijoy and Raman, 2003; Jacob, 2006). As a result, more conflicts, land struggles, and the politicization of legitimate claims of the Adivasi population continue to be frequently witnessed (Bijoy, 1999; Chemmencheri, 2013). In particular, in the last few decades, an absolute marginalization of the native tribal community has been observed, as one local resident commented:

Only one or two communities of these tribes have their own land. Most of the primitive tribal groups, like Paniya, Adiya, and Naikkan, are landless, and they have nothing but a thatched roof over their head. They don't have a system of possessing land; rather, they lived in tune with nature, engaged in farming. The fruits of their hard work are reaped by the outsiders, who pose a threat to the lives of the Adivasi. There was a lot of migration from Christian, Hindu, and Muslim communities. (Jayan, interview, 2016)

One thing common to all residents of Wayanad is the role of rice in their sacred customs and traditions, which is especially true for the Adivasi. As the name “land of paddy fields” suggests, the importance given to rice cultivation is undeniable. There are roughly 1,000 varieties of rice native to this region, and its history of land development dates back thousands of years (Gopi and Manjula, 2018; Ratheesh, 2023). They consider seeds to be a gift of the gods and hence consider them sacred. More than 70 varieties of rice can be cultivated under any of the region's agro-climatic and soil conditions. This agrobiodiversity provides an immense capacity to cope with droughts and floods (Gopi and Manjula, 2018). “Valicha” is a special technique of rice cultivation, especially for the summer season. The Adivasi believe that rice keeps the body and soul together and that it is therefore the sole reason for their existence. They pray, evoke, respect, and acknowledge their gods and ancestors at all stages of paddy cultivation. In this way, they believe they are protecting, preserving, and developing the varieties of rice while fulfilling the role of guardians of the rich biodiversity of this region. An agrobiodiversity researcher at M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation noted the following:

Cheruvayil Raman, an Adivasi farmer who still passionately grows and preserves forty-five-plus types of endemic seeds, is a living testament to their attachment to rice and agriculture. (Seema, interview, 2016)

Non-Adivasi interviewees also attested to the Adivasi's ecological knowledge (e.g., interviewees Krishna and Jayan, cited earlier). With its land being so fertile, Wayanad has the potential to supply the demand for vegetables for all of Kerala. Moreover, it can be cultivated without pesticides or agricultural chemicals. The conditions are also conducive to growing spices, such as cardamom, pepper, and turmeric. As an environmental activist and a thematic expert noted:

Spices can be cultivated organically and sold as “animal-friendly,” which will, in turn, open up a great market. However, the gross marginalization of the environment-friendly culture of Adivasi, unplanned overconsumption, mono-crop cultivation, and overuse of chemicals and pesticides have rendered Wayanad vulnerable to chronic indebtedness, imbalance of prices, declining fertility, and contamination of water resources, which has manifested in a series of suicide cases among the medium- and small-scale farmers. (Basheer, interview, 2016)

The effects of the depletion of the soil resulting from the prevalence of monoculture plantations and the widespread use of pesticides and insecticides have become apparent. This degradation is reflected in the reduced output of cash crops despite recent favorable market conditions (Varghese, 2024). The emergence of diseases is also a factor that affects plantations.

These factors have led to a contradictory situation and a threatening state of an agrarian crisis from which tourism has emerged as a viable development option. However, expanding the hospitality and tourism industry into ecologically fragile regions has never been considered thoroughly, as tourism has never been seen as a significant polluter of the environment (Gössling, 2000). A member of Vythiri Panchayat (local self-government) in Wayanad said:

Deforestation continues even today in an aggressive manner for a combination of reasons, but the tourism industry does not play a crucial role in that. (Veena, interview, 2016)

Tourism development has been further legitimized and earned wide consensus due to the belief that revenue generated will trickle down to all sectors of society and that the tourism industry will create jobs for the local population. The tourism industry's expansion is not commonly viewed as a direct reason for deforestation and ecological imbalance (Khan et al., 2020; Baloch et al., 2023). Thus, the failing agrarian economy, the resultant impoverishment, and biodiversity loss are leading to a further marginalization of Adivasi communities. This is the context in which tourism development in Wayanad and its implications must be assessed.

The Wayanad Tourism Organization (WTO) has played a vital role in fostering the growth of the tourism sector. Its establishment was centered on planning and initiating measures to develop the tourism industry. The WTO serves as a platform for local tourism entrepreneurs to address shared concerns collectively and find solutions through collaborative efforts. Additionally, it acts as a bridge, connecting the local tourism industry with government tourism agencies and facilitating the promotion and management of tourism in the region (Chandran, interview, 2016). The WTO claims to foster a culture of sustainable tourism, addressing local ecological and social issues while setting up quality standards and practices. However, it is evident from interactions with the members and its pamphlets and website that the WTO is actively engaged in promoting Wayanad as a tourist destination to increase visitors to small- and medium-scale tourist resorts and homestays.

To promote Wayanad and its undiscovered wilderness, the WTO organizes key events such as Splash—a monsoon tourism carnival, and the MTB (Mountain Bike Rally). Splash, a collaborative effort among the Wayanad District Tourism Promotion Council (DTPC), the district administration, and the Kerala tourism department, occurs annually to highlight tourism opportunities during the monsoon, including rainy-season football tournaments. Another event, Splash B2B, serves as a platform for buyers and sellers in the tourism industry to engage in exhibitions and meetings. While we see efforts to attract people, businesses, and governments to maximize the positive economic, social, and environmental impacts of tourism, initiatives to minimize the negative impacts are nowhere to be found. As one former WTO secretary and tourism industry representative mentioned:

In this entire tourism process, the WTO's central aim is to maximize profit, and it does not find tourism to be a polluting industry, seeing no harm in the commodification of the environment. The government supports their initiatives wholeheartedly with the conviction that tourism is the only development option left for Wayanad. (Chandran, interview, 2016)

The emergence of tourism coincided with the decline of traditional livelihoods in Wayanad, exacerbating environmental degradation. Overcrowding in national parks and wildlife sanctuaries disturbs wildlife, while uncontrolled construction for tourism exacerbates residents' concerns. In this underdeveloped district, tourism projects neglect employment opportunities for Adivasi communities and exploit the environment for marketable products in the tourism industry. The agrarian economy is rapidly shifting toward tourism development, which converts agricultural land into hotels and resorts (Jacob, 2006). Besides the official development plans and proposals for this ecologically fragile zone, we observed the illegal construction of skyscraper flats and apartments near Vythiri and Kalpetta (Figure 1C), which threatens ecological integrity and increases disaster risks.

In response to the increasing public concern about tourism, organizations such as Uravu,4 EQUATIONS, and Pazhassi Raja College initiated seminars and conferences with the backing of the Kerala Tourism Department in 2001. These events focused on exploring the impacts of tourism, including discussions on traditional livelihoods, community revival, and emerging concerns about the tourism sector. These deliberations still continue to emphasize the need for thoughtful consideration of the effects of tourism. One of the conference conveners remarked:

Wayanad Prakriti Samrakshana Samiti5 (WPSS) was completely against the idea of development through tourism and opposed vehemently. Uravu did not want to negate tourism but wanted to use it in a better way for the people of Wayanad. We wanted panchayats/local bodies to get more power. Traditional farmers and handicraft workers should have a say in the kind of tourism development that the local bodies put forth. Our main demand was to decentralize tourism. (Bhaskar, interview, 2023)

Eventually, in 2007, the Kerala government implemented the Responsible Tourism (RT) initiative in the belief that it would address various challenges in the tourism sector, alleviate public discontent, and foster a positive environment for tourism development. Therefore, today, the government of Kerala runs tourism under two modes in Wayanad: mass tourism spearheaded by the DTPC and the RT. Both are heavily dependent on destination points, the tourism industry, and the private sector.

The RT initiative started in Vythiri as a pilot project involving the procurement of locally grown products from nearby farmers and artisans, which were then distributed to hotels and resorts. This initiative was hailed as a successful example of RT, and similar activities are being replicated in Ambalavayal in Wayanad. The remarks of the district coordinator of the RT attest to how the RT is still at the mercy of giants in the tourism industry:

RT has two souvenir shops, Samrudhi groups,6 one eco-shop (not operational now), village visits, and we run other campaigns aimed at the removal of plastic from the destination points and initiatives to protect against landslide dangers. For these activities, we work closely with the industry for overall support and get sponsorships from them. (Sagar, interview, 2016)

The involvement of the local community7 has been minimal, given that most resorts and hotel chains are owned by persons and companies outside Wayanad. Adivasi communities, in particular, have been excluded from the tourism business because they lack the knowledge and resources to benefit economically from these activities. As one Adivasi farmer noted:

In Wayanad, you will not see even a single homestay operated or owned by an Adivasi. The hotels and resorts never purchase our products, citing hygiene and durability issues. Then how can we benefit from tourism? (Radha, interview, 2023)

Wayanad is an attractive tourist spot for both domestic and foreign tourists. However, the Adivasis have not benefited from the growing tourism. If the Adivasi community actively engaged in and managed the entire tourism value chain within indigenous ecotourism, they could potentially gain an advantageous position in the future (Thimm and Karlaganis, 2020). However, the social empowerment of the Adivasis, which would lead to a fair distribution of benefits from tourism, is a challenge in need of an immediate, effective solution.

Notwithstanding the Adivasi community's exclusion from tourism development, environmental concerns, such as solid waste—particularly waste plastic—are significant issues affecting both the environment and local communities (Gadgil, 2014). Uncontrolled tourism leads to the loss of natural habitat, increased pollution, pressure on endangered species, overconsumption, and waste production, which exacerbate the vulnerabilities of the region, as evidenced by the devastating Kerala floods in 2018. This event affected 5.4 million people, displaced 1.4 million, and resulted in 449 casualties, with Wayanad being one of the most severely affected districts (Walia and Nusrat, 2020). However, recently, there has been collaboration between local self-governments and NGOs to analyze the connection between tourism and local livelihoods. This involves mapping the industry's supply chains, understanding demographics and labor practices, and assessing ownership and usage of existing resources in the area (Prejith, interview, 2023). The overarching goal is to identify opportunities for the inclusion of local communities in tourism and propose strategies for generating cross-sectoral benefits from the tourism sector.

The tourism sector's central claim is that it can contribute to the local economy, and this has given the industry and governments an overriding power to disregard other impacts. For example, in “Tourism and Livelihood: Selected Experiences from Kerala”—a government study (Vijayakumar and Roy, 2013)—the success parameters of tourism initiatives are tourist arrivals, income from transport services, and income from homestays. Despite the increasing visibility of tourism's destructive impact on ecology and society (Gössling, 2002; Wheeller, 2007; Gössling et al., 2011; Lenzen et al., 2018), it is not explicitly recognized and addressed. Furthermore, the potential for sustainable tourism governance is never explored or assessed.

Wayanad, once primarily an agricultural region, now struggles with food scarcity due to variations in topography and climate. The ecological imbalance is well illustrated by the diminished rainfall in Lakkidi (Figure 1C) and the erratic rainfall patterns throughout the district (Shaji, 2019; Varma, 2019; Viju, 2019; Onmanorama, 2023).

The system of monoculture plantation, with its use of pesticides, insecticides, and other practices, exploited the soil of Wayanad for commercial value. These came along with quarrying and deforestation practices for tourism expansion and monoculture plantations, which further disturbed the ecological balance. These atrocities aggravated the existing environmental imbalance. This imbalance was reflected in the reduced harvest in terms of cash crops and gradually affected the plantation despite high market prices. This is marked by the advent of the tourism industry in its full vigor. (Basheer, interview, 2016)

Once a lush and verdant location tucked away from popular tourism destinations in Kerala, it is currently grappling with water scarcity, a consequence of severe environmental degradation that has compelled people to relocate. The Kerala Biodiversity Board's report findings show that the Wayanad agro-ecosystem had lost 160 varieties of rice, 12 varieties of pepper, 13 types of bananas, and numerous vegetables and tubers (GoK, 2019). Furthermore, the practice of free, prior, and informed consent (Buppert and McKeehan, 2013), acknowledged as a crucial aspect of stakeholder engagement and essential for successful development initiatives, was never undertaken. An elected representative asserted the following:

The tourism industry is in constant search of more and more destinations, thus resulting in the growth of hotels and resorts in the adjacent regions, as seen in Vythiri village, where the households have decreased due to the mushrooming of resorts. (Nisha, interview, 2016)

The effects of tourism expansion on the environment and livelihoods of the local people are often considered too dismal and are thus neglected. This neglect has led to an acute agrarian crisis (Mohanakumar and Sharma, 2006). The current market, research, and policies are attuned in favor of modern varieties of crops, which undermines the rich genetic diversity of traditional cropping systems (e.g., the diversity of rice varieties) and offers resilience to climate change. This also has both culinary and cultural importance for the people (Gopi and Manjula, 2018). However, the destruction of the unique environment (a combination of terrain, grasslands, rain, springs, and altitude) in Wayanad has made agriculture unsustainable. In this regard, a spice trader stated:

The agrarian crisis in Wayanad points to the disturbed ecology in terms of its local topography and climate, along with a fall in the price of crops. This contrasts with the case [elsewhere in India] where the collapse of the price of crops solely affected agriculture. The recovery of the price of crops will not resolve the agrarian crisis in Wayanad, as the ecosystems that provide services to agriculture there have been weakened. (Navin, interview, 2016)

Tourism development in Wayanad is causing a rise in human–animal conflicts (Münster, 2012). Since 2014, 149 deaths and over 1,000 injuries have been recorded in Wayanad due to human–animal conflicts. However, in the fiscal year 2022–2023 alone, this figure skyrocketed to 98 deaths, occurring amid 8,873 attack instances, with 27 of these fatalities attributed to elephants (Varghese, 2024). Aside from the immediate threat to human lives, animal-related incidents have also inflicted substantial harm on the agricultural sector. Between 2017 and 2023, there were 20,957 reported incidents of crop damage due to wildlife intrusion, resulting in the loss of 1,559 domestic animals, predominantly cattle (Sumitha and Shahaarban, 2022; Kannan, 2023; Varghese, 2024). As a political activist poignantly noted:

Vythiri Panchayat and Mupainad Panchayat are the two areas that are prone to the dangerous geographical phenomenon known as landslides due to mountain and hill destruction and land filling there. This has affected the sustainability and weather conditions in Wayanad, and today, there are various resorts and homestays coming up in these forest areas. They use generators at night; light and sound from these resorts travel up to a range of kilometers inside the forest areas. This sound and light produced along with the smoke generated by the kitchen factories pull out the wild animals from the interiors of the forest, and, as expected, this causes an unpleasant atmosphere inside the forest. (Thomas, interview, 2016)

Consequently, there is an adversarial environment within the interior forest due to tourism activities and related pressures, leading to negative impacts on surrounding areas. The government's forestry program has exacerbated the problem by converting natural stands of forest into plantations of tree species, such as eucalyptus, acacia, and mahogany. These exotic species have deprived wild animals of their natural food sources, forcing them to leave the forest (Varkey et al., 2018; Saha et al., 2022). The combination of these factors, along with the impact of tourism development activities, contribute to the alarming increase in wild animal attacks today.

Land clearing and transformation, along with evictions, play pivotal roles in facilitating tourism growth. Land marked for tourism eventually ends up being used for trails, retail zones, parking lots, camping sites, holiday residences, golf courses, and waste disposal sites (Gössling and Peeters, 2015), which, if not adequately controlled, can significantly impact the environment.

In Kuruvadweep (or Kurava Islands; Figure 1C), a famous tourism destination in the northern part of the district, the entry to seven islands was reduced to two in response to concerns about environmental degradation raised by the local people (Rajeev, 2017). In some areas, people evicted from their houses in the name of tourism have not yet been completely rehabilitated or compensated. Furthermore, as many Adivasi groups never had the practice of possessing land, it was a relatively easy task for tourism establishments to expand by displacing them (e.g., Jayan above). An Adivasi leader opined:

Kuruva Islands and Muthanga have now become a business zone. Wild animals are hunted down, thousands of rupees are looted under various social forestry projects, and illegal trafficking of ivory and sandalwoods from Sathyamangalam and Bandipur [Figure 1C] are carried out. These are carried out under the garb of tourism projects. Projects like the walking path for elephants are being agreed on now despite the known fact that elephants don't normally take to roads for their search for food and water. This circuit is designed to attract tourists. Muthanga offers big hopes for ecotourism advocates; hence, the current aim is to evacuate the local residents to extract maximum advantage from the resources there. Illegal brewing is another rampant problem that is conducted on a large scale inside the deep forest, with the help of officials of the forest department. These are the activities carried out under the larger banner of eco-tourism. (Rani, interview, 2016)

Similarly, the Karapuzha tourism project, another tourism site in the district, and the Banasura Sagar Dam Project have evacuated many tribal families without providing proper rehabilitation facilities (Shruthi, 2020). Most of the tourism centers are turning into business zones without much involvement of the marginalized groups.

Most of the employment vacancies that are offered to the tribal people seldom reach them; however, since the swearing in of P. K. Jayalakshmi as the Minister for Welfare of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Backward Classes, people of the Kurichya tribe have started getting jobs at Kuruva Islands tourism projects. The local tribes of the Vettakuruma and Adiya communities, who have better knowledge of the local environment, were ignored in favor of the Kurichya community for the posting of staff. Tribal Vana Samrakshana Samiti (VSS) has given jobs to Adivasis here, and there are people who do jeep safaris at Muthanga and Tholpetty wildlife sanctuaries. They get income from taking tourists around, but apart from these, marginalized populations like the Adivasi have gotten no regular permanent jobs. (Seema, interview, 2016)

Hence, tourism projects have put many livelihoods at stake at various sites. Offers regarding employment and the reallocation of land remain unfulfilled even after years. Struggles for the inclusion of tribal people often lack public support within the locality because excluding tribal people makes way for including non-tribal natives. Moreover, the energy requirements for tourism and the overall greenhouse gas emissions from it, including food and beverages, infrastructure construction and maintenance, retail, and financial services, further exacerbate the impact (Richardson, 2021).

Job irregularities and a lack of social protection measures are more pronounced in development led by tourism. Despite the reservation policy guaranteed under the Indian Constitution, no actual benefits reach the intended sections. The Pookode Dairy Project is a true reflection of this, with non-Adivasi people being given jobs under the Scheduled Tribe reservation category. Eventually, neither jobs in the Diary Project nor land were given to a large number of Adivasis. This project is yet another example of a gross violation of the Forest Rights Act, which sought to enable land ownership for the Adivasis (Sathyapalan, 2010; Münster and Vishnudas, 2012).

Much of the tourism projects in and around Wayanad aim to snatch land from tribal people and end up in a land struggle. Projects offer tall claims, like better employment opportunities and development, which remain as mere offers for local people. (Basheer, interview, 2016)

Unfortunately, the tourism industry is hardly seen as having a direct causal association with quarrying, deforestation, biodiversity loss, displacement of people, a lack of jobs for local people, or their non-inclusion in stakeholder engagements (Gössling, 2000). This is because the projections for foreign exchange earnings, income generation, high-rises and plush resorts, the number of staff employed, the number of rooms and types of amenities, and so on, are normally considered indicators of tourism development. A thematic expert in tourism noted the following:

The extent of land destruction in tourism is much less compared to the mining industry because, from the environmental point of view, insinuations emerging about the tourism industry are perceived as far better than the coal mine industry, and this is the argument of the tourism industry, which is hence promoted as a clean industry without actual studies. (Shweta, interview, 2016)

Relying exclusively on tourism for development proves inadequate, given its adverse impact on exclusion and socioeconomic stratification (Sanchez and Adams, 2008). Control, participation in the co-management of destinations, and self-empowerment through tourism remain long-distant dreams for the Adivasi community (Ryan and Huyton, 2000; Whyte, 2010; Jamal and Camargo, 2014). The current form of tourism disrupts the sustainable resource collection methods employed by tribal communities and impedes traditional cultivation practices, such as rice farming. Due to limited job opportunities in Wayanad, many locals seek employment in Coorg, where they face exploitation by landowners who offer alcohol to extend working hours and compensate for low wages (as witnessed by interviewees Krishna, Basheer, Bhaskar, Rani, Nisha, and Seema [2016], as well as Radha [2023]). The development of Wayanad is thus intricately tied to its environment, and negligent tourism projects not only harm the immediate surroundings but also disturb the broader ecological balance. The field findings and observations mentioned earlier raise concerns about the symbiotic relationship between tourism and the environment.

In light of the preceding discussion, we can characterize the socio-ecological state of Wayanad by deforestation, ecological imbalance, agrarian deprivation, excessive numbers of tourists, illegal construction of resorts, human-caused disasters, tribal displacement, unemployment, land destruction, and human–animal conflict. For tourism to be constructive and deliver a sustainable and clean environment and economic benefits for the Adivasis, local community members, and local governing bodies, the indisputable key is to link it with biodiversity conservation (Gössling and Hall, 2006; Bramwell and Lane, 2011; Brandt et al., 2019). Wayanad should strive to be a successful model for the efficient management of the natural environment. In the context of tourism, biodiversity conservation is crucial, as it is linked to protecting the assets that attract visitors (Pett et al., 2016; Brandt et al., 2019). The Adivasi communities, with their ecological knowledge and time-tested sustainable practices, are guardians of such assets. Even though most tourists are interested in pristine views, a comfortable stay, and privacy, sustainable and inclusive development is not possible without focusing on the rights and livelihoods of the Adivasi communities. Rather, it is these rights and livelihoods based on traditional activities that are critical in supporting and delivering the major attractions of tourism in Wayanad (i.e., rich biodiversity and indigenous heritage).

Hence, Wayanad assuming a leadership role in advocating for biodiversity conservation and implementing initiatives to achieve this goal is imperative. Instead of demanding expansion of the road network in Wayanad, which threatens biodiversity, the tourism industry should instead engage in biodiversity tourism and inclusive development by bringing Adivasi communities into the fold with their consent. Moreover, tourism programs should focus on maximizing local community participation by reviving traditional houses/materials, traditional knowledge systems, and local ways of life. Furthermore, programs should strive to increase biodiversity awareness among tourists by linking up with local farmers to provide organic food from their farmlands, managing waste using environmentally sound methods, and financially supporting locals associated with tourism programs by building deep community networks (Gössling, 1999; Rasoolimanesh and Mastura, 2016; Bello et al., 2018; Rajashree and Dash, 2023). In short, for the sake of sustenance and positive interconnections, tourism must be in harmony with nature.

This multi-sectoral issue can only be resolved in multistakeholder discussions. A platform that necessitates such discussions to happen in an effective manner needs to be established. Wayanad, as a biodiverse region, particularly in agrobiodiversity (Kumar and Prajeesh, 2016), can explore the application of new conservation schemes—“other effective area-based conservation measures” (OECMs)—which, in brief, fall outside formal protected areas that function as one with well-defined boundaries and a governance structure (CBD, 2018). The recognition of a measure as an OECM would be expected to increase social visibility and branding. The preparation for obtaining this recognition will require the institutionalization of biodiversity-sound management protocols, which will result in bringing stakeholders together to discuss their interests and concerns and clarify their roles, responsibilities, and opportunities. A multistakeholder platform should be formed to ensure the effective operationalization of governance by various stakeholders who are already present in various functions and interests. Such an arrangement would benefit not only the conservation of biodiversity but also responsible tourism and result in the sustainable development of Wayanad.

Our findings illustrate that despite promises of the sustainable utilization of natural resources and social progress, tourism development has brought about additional challenges for both biodiversity and society. The migration history coinciding with land-grabbing and a dwindling ecological balance has resulted in the loss or undermining of traditional livelihood activities. The situation of Adivasi communities is precarious, as they are already vulnerable to many factors caused by environmental degradation and the agrarian crisis. Tourism development has further accentuated these existing deficiencies, as leveraging tourism is not an equitable process. No forms of sustainable tourism have been able to reverse the environmental degradation, displacement of people, or alienation of indigenous communities from their own environments. This has been exacerbated by the lack of consensus building with local communities and overreliance on the tourism industry. While the positive impacts of tourism development are highlighted in most work, future research should also assess and reiterate its negative impacts to minimize the trade-offs. The multi-sectoral linkages illustrate tourism's adversarial socio-ecological impacts: the eviction of people to make way for the expansion of tourism projects, human–wildlife conflicts following habitat disturbance and fragmentation, and a lack of social security measures or employment guarantees to compensate for the disadvantages emerging from development based on tourism. These linkages highlight impacts that have further intensified the fragility of the region, with an increasing socio-ecological imbalance. Finally, the role of indigenous communities and their time-tested traditional practices and knowledge of biodiversity conservation must be further recognized and revived for sustainable and inclusive tourism to succeed in Wayanad.

This manuscript is part of a publicly defended PhD thesis by PV. The data was updated with repeated visits to the field by both PV and YN during 2022–2023.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because all individuals involved in this research gave verbal consent to be part of this research as research partners/experts and they consented on behalf of their organization, though views and comments were of their own. All voice recordings are available and safely maintained by PV. We are unable to share our data at present because several more publications are yet to emerge from the study.

PV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research update during 2022-2023 was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP22F22783 and JP22KF0321. PV was supported by the Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research in Japan of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and the research was supported by JSPS-Kakenhi grant. We are grateful for their support.

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to Dr. Hannah Johns for her critical input and proofreading of an initial version of this manuscript. We express our sincere gratitude to Akita International University (AIU), Japan.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^For more, https://resource.capetown.gov.za/documentcentre/Documents/Agreements%20and%20contracts/Toruism_RT_2002_Cape_Town_Declaration.pdf (capetown.gov.za).

2. ^For more, Kerala Declaration - Harold Goodwin.

3. ^A small Jain community.

4. ^Founded in 1996, Uravu is a non-profit organization situated in Wayanad, Kerala, India, dedicated to empowering rural communities through sustainable solutions. Central to its efforts is the utilization of bamboo, as the organization delves into and advocates for diverse applications ranging from construction to crafts.

5. ^WPSS – Wayanad Forest Protection Committee (a volunteer organization).

6. ^The activity group constituted for the procurement and supply of locally produced goods by Kudumbasree, which is the largest self-help group in India.

7. ^“Local community” in this article is inclusive of the indigenous population.

Baloch, Q. B., Shah, S. N., Iqbal, N., Sheeraz, M., Asadullah, M., Mahar, S., et al. (2023). Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: a suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 30, 5917–5930. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-22496-w

Bello, F. G., Lovelock, B., and Carr, N. (2018). Enhancing community participation in tourism planning associated with protected areas in developing countries: lessons from Malawi. Tour. Hospit. Res. 18, 309–320. doi: 10.1177/1467358416647763

Bijoy, C. R. (1999). Adivasis betrayed: Adivasi land rights in Kerala. Econ. Polit. Weekly 34, 1329–1335.

Bramwell, B., and Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 19, 411–421. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.580586

Brandt, J. S., Radeloff, V., Allendorf, T., Butsic, V., and Roopsind, A. (2019). Effects of ecotourism on forest loss in the Himalayan biodiversity hotspot based on counterfactual analyses. Conserv. Biol. 33, 1318–1328. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13341

Buppert, T., and McKeehan, A. (2013). Guidelines for Applying Free, Prior and Informed Consent: A Manual for Conservation International. Arlington, VA: Conservation International.

Burrai, E., Buda, D. M., and Stanford, D. (2019). Rethinking the ideology of responsible tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 992–1007. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2019.1578365

CBD (2018). Decision 14/8. Protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-14/cop-14-dec-08-en.pdf (accessed March 13, 2024).

Chandrika, C. S., and Nandakumar, P. M. (2015). Paniya Adivasi women innovative livelihood development endeavours in farming. Working Papers id:7064, eSocialSciences. Available online at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ess/wpaper/id7064.html (accessed March 13, 2024).

Chemmencheri, S. R. (2013). Decentralisation, participation, and boundaries of transformation: Forest Rights Act, Wayanad, India. Commonwealth J. Local Gover. 12, 51–68. doi: 10.5130/cjlg.v12i0.3264

Colah, R. B., Mukherjee, M. B., Martin, S., and Ghosh, K. (2015). Sickle cell disease in tribal populations in India. Indian J. Med. Res. 141, 509–515. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.159492

Dawson, N. M., Coolsaet, B., Sterling, E. J., Loveridge, R., Gross-Camp, N. D., Wongbusarakum, S., et al. (2021). The role of indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecol. Soc. 26:319. doi: 10.5751/ES-12625-260319

Devika, J., and Rajasree, A. K. (2008). Health, democracy and sickle-cell anaemia in Kerala. Econ. Polit. Weekly 43, 25–29.

Gadgil, M. (2014). Western Ghats ecology an expert panel: a play in five acts. Econ. Polit. Weekly 49, 38–50.

GoK (2011). District Urbanisation Report Wayanad. Government of Kerala, Department of Country and Town Planning. Available online at: https://townplanning.kerala.gov.in/town/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/dur_wayanad.pdf, Available online at: https://townplanning.kerala.gov.in/town/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/dur_wayanad.pdf (accessed July 03, 2018).

Gopi, G., and Manjula, M. (2018). Speciality rice biodiversity of Kerala: need for incentivising conservation in the era of changing climate. Curr. Sci. 114, 997–1006. doi: 10.18520/cs/v114/i05/997-1006

Gössling, S. (1999). Ecotourism: a means to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystem functions? Ecol. Econ. 29, 303–320. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00012-9

Gössling, S. (2000). Tourism–sustainable development option? Environ. Conserv. 27, 223–224. doi: 10.1017/S0376892900000242

Gössling, S. (2002). Global environmental consequences of tourism. Global Environ. Change 12, 283–302. doi: 10.1016/S0959-3780(02)00044-4

Gössling, S., and Hall, M. C. (2006). Tourism and Global Environmental Change. Ecological, Economic, Social and Political Interrelationships. London and New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203011911-1

Gössling, S., and Peeters, P. (2015). Assessing tourism's global environmental impact 1900–2050. J. Sustain. Tour. 23, 639–659. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1008500

Gössling, S., Peeters, P., Hall, C. M., Ceron, J.-P., Dubois, G., Lehman, L. V., et al. (2011). Tourism and water use: supply, demand and security, and international review. Tour. Manage. 33, 16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.015

Government of India (2011). Census of 2011. Available online at: https://censusindia.gov.in/ (accessed February 22, 2024).

Heslinga, J., Peter, G., and Frank, V. (2017). Strengthening governance processes to improve benefit-sharing from tourism in protected areas by using stakeholder analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 773–787. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1408635

IUCN (2020). Western Ghats - 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment. IUCN World Heritage Outlook. Available online at: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ (accessed October 17, 2023).

Jacob, T. G. (2006). Misery in an Emerald Bowl – Essays on the Ongoing Crisis in the Cash Crop Economy – Kerala. Mumbai: Vikas Adhyayam Kendra.

Jamal, T., and Camargo, B. A. (2014). Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: toward the just destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 22, 11–30. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.786084

Jurgens, S. S., Mijts, E., and Van Rompaey, A. (2024). Are there limits to growth of tourism on the Caribbean islands? Case-study Aruba. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1292383. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1292383

Kannan, A. (2023). Rs 100-crore plan to mitigate man-animal conflicts in Wayanad. The New Indian Express. National Daily. Available online at: https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/2023/Jul/24/rs-100-croreplan-to-mitigateman-animal-conflicts-in-wayanad-2597913.html (accessed February 11, 2024).

Khan, A., Bibi, S., Ardito, L., Lyu, J., Hayat, H., and Arif, A. M. (2020). Revisiting the dynamics of tourism, economic growth, and environmental pollutants in the emerging economies—sustainable tourism policy implications. Sustainability 12:2533. doi: 10.3390/su12062533

Kjosavik, D. J., and Shanmugaratnam, N. (2007). property rights dynamics and indigenous communities in Highland Kerala, South India: AN institutional-historical perspective. Mod. Asian Stud. 41, 1183–1260. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X06002617

Kumar, A. N., and Prajeesh, P. (2016). “Community agrobiodiversity management: an effective tool for sustainable food and agricultural production from SEPLS,” in Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review Volume 2, eds. UNU-IAS and IGES (Tokyo: United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability).

Kumar, B. V. (2005). Participatory tourism development in tribal areas – a study of Wayanad' under the research project ‘Development of Malabar'. Report submitted to Kannur University, Kerala.

Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., and Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 522–528. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

Levis, C., Flores, B. M., Campos-Silva, J. V., Peroni, N., Staal, A., Padgurschi, M. C., et al. (2024). Contributions of human cultures to biodiversity and ecosystem conservation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41559-024-02356-1

Mohanakumar, S., and Sharma, R. K. (2006). Analysis of farmer suicides in Kerala. Econ. Polit. Weekly 41, 1553–1558. doi: 10.2307/4418114

Münster, D. (2012). Farmers' suicides and the State in India: conceptual and ethnographic notes from Wayanad, Kerala. Contrib. Indian Soc. 46, 181–208. doi: 10.1177/006996671104600208

Münster, U., and Vishnudas, S. (2012). In the Jungle of Law Adivasi Rights and implementation of Forest Rights Act in Kerala. Econ. Polit. Weekly 47, 38–45.

Onmanorama (2023). Wayanad records 60% deficient rainfall in June, agrarian activities hit. Available online at: https://www.onmanorama.com/news/kerala/2023/06/27/wayanad-rain-deficit-june-agrarian-activities-hit.html (accessed March 13, 2024).

Pett, T. J., Shwartz, A., Irvine, K. N., Dallimer, M., and Davies, Z. G. (2016). Unpacking the people?biodiversity paradox: a conceptual framework. BioSci. 66, 576–583. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biw036

Rajashree, S., and Dash, M. (2023). Ecotourism, biodiversity conservation and livelihoods: understanding the convergence and divergence. Int. J. Geoher. Parks 11, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgeop.2022.11.001

Rajeev, K. R. (2017). Fissures in LDF in Wayanad over Kuruva island tourism, Times of India. Available online at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kozhikode/fissures-in-ldf-in-wayanad-over-kuruva-islandtourism/articleshow/62198519.cms?utm_source=contentofinterestandutm_medium=textandutm_campaign=cppst (accessed March 13, 2024).

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., and Mastura, J. (2016). “Community participation toward tourism development and conservation program in rural world heritage sites,” in Tourism-from Empirical Research Towards Practical Application (IntechOpen). doi: 10.5772/62293

Richardson, R. B. (2021). “The role of tourism in sustainable development,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.387

Ryan, C., and Huyton, J. (2000). Who is interested in Aboriginal tourism in the Northern Territory, Australia? A cluster analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 8, 53–88. doi: 10.1080/09669580008667349

Saha, K., Ghatak, D., and Muralee, NS. (2022). Impact of plantation induced forest degradation on the outbreak of emerging infectious diseases-Wayanad District, Kerala, India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:7036. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127036

Sanchez, P. M., and Adams, K. M. (2008). The Janus-faced character of tourism in Cuba. Ann. Tour. Res. 35, 27–46. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.06.004

Sathyapalan, J. (2010). Implementation of the Forest Rights Act in the Western Ghats Region of Kerala. Econ. Polit. Weekly 45, 65–72.

Shaji, K. A. (2019). An environmental catastrophe is lurking in Wayanad. Available online at: https://india.mongabay.com/2019/04/an-environmental-catastrophe-is-lurking-in-wayanad/ (accessed March 9, 2024).

Shruthi, T. V. (2020). Impact of Banasura Sagar Dam on the Wayanad Kadar Tribes of Kerala. J. Hum. Ecol. 70, 51–57. doi: 10.31901/24566608.2020/70.1-3.3184

Sumitha, P. S., and Shahaarban, V. (2022). Economic impact of wild animal conflict on agriculture sector – a study in Wayanad District, Kerala, India. Asian J. Res. Rev. Agric. 4, 17–25.

Thimm, T., and Karlaganis, C. (2020). A conceptual framework for indigenous ecotourism projects–a case study in Wayanad, Kerala, India. J. Herit. Tour. 15, 294–311. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2020.1746793

UNESCO (2012). World heritage convention - Western Ghats. Available online at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1342, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1342 (accessed March 20, 2024).

Varghese, P. (2024). The collapse of the ecological balance and an undeclared war with nature. The Hindu.

Varghese, V. J. (2009). Land, labour and migrations: Understanding Kerala's economic modernity. Working paper 402. Centre for Development Studies.

Varghese, V. J. (2016). Yielding to the divine will? Agricultural migrations and its religious moralities in modern Kerala. Proc. Indian Hist. Congr. 77, 1112–1128.

Varkey, J. K., Gopakumar, S., Vidyasagaran, K., Mathew, J., and Kumar, A. V. S. (2018). Forest laws, for whom, by whom? A concept mapping study of the Ecologically Fragile Lands Act, 2003 in Wayanad, Kerala, India. Curr. Sci. 115, 1459–1469. doi: 10.18520/cs/v115/i8/1459-1469

Varma, V. (2019). Wayanad remains at the centre of Kerala's rainfall devastation story. The Indian Express E-paper. (accessed March 13, 2024).

Vijayakumar, B., and Roy, S. (2013). Tourism and Livelihood: selected experiences from Kerala. Technical report, Kerala Institute of Tourism and Travel Studies.

Viju, B. (2019). Is Wayanad facing the brunt of climate change? The News Minute. Available online at: thenewsminute.com (accessed March 13, 2024).

Vitousek, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Lubchenco, J., and Melillo, J. M. (1997). Human domination of Earth's ecosystems. Science 277, 494–499. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.494

Walia, A., and Nusrat, N. (2020). Kerala Floods 2018. National Institute of Disaster Management, New Delhi, 106.

Wheeller, B. (2007). Sustainable mass tourism: more smudge than nudge the canard continues. Tour. Recreat. Res. 32, 73–75. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2007.11081543

Keywords: ecotourism, livelihood, Adivasi, Kerala, inclusive development, sustainable development, biodiversity conservation

Citation: Varghese P and Natori Y (2024) The socio-ecological impacts of tourism development in the Western Ghats: the case of Wayanad, India. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1384962. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1384962

Received: 11 February 2024; Accepted: 24 April 2024;

Published: 09 May 2024.

Edited by:

Michal Apollo, University of Silesia in Katowice, PolandReviewed by:

Wendy Hillman, Central Queensland University, AustraliaCopyright © 2024 Varghese and Natori. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Philip Varghese, cG9zdDJwaGlsaXBAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.