- Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

The purpose of this study is to demonstrate that authenticity is a complicated and imprecise concept. Using autoethnography as an approach to the study and, in particular, a consideration of the meanings of aboriginal souvenirs originating in Taiwan that are in the authors' possession, it is shown that these objects do not fit snuggly into typical classifications that have been proposed to address authenticity. Authenticity is a concept that can hide issues of power and powerlessness. It is suggested that authentication, who says something is authentic and why they do so, is important as it facilitates consideration of access to power.

1 Introduction

I have a long-standing interest in tourism and its implications. My interests have concentrated particularly upon the economic, environmental and social consequences of tourism and their implications for sustainability. This can be viewed at a wide variety of scales from the global to the local: from the implications of flying people of different types, from place to place, to interact with people and environments that are very different from those to which they are accustomed; to the implications and meanings of souvenirs that have been brought back as a memento of a trip or given as a gift by someone on their return from a journey. It is the latter that I will focus upon in this communication.

I have many such souvenirs. As I am sitting at the computer, on the mantlepiece above the fireplace I can see two carved heads, one of a woman and one of a man, that I bought in Nigeria. They remind me of a visit I made in 1978, my only visit to Africa south of the Sahara. They are an example of “tourist art” (Graburn, 1977). They were mass produced, albeit by hand, to make some money and cater to the interests of foreigners like me. Also, on the mantlepiece are two shells, similar to very large snail shells, that were brought back to England from the Red Sea, along with some pieces of coral, by my deceased father, and subsequently brought by me to Canada. They remind me of him, as does a small vase from Japan, which was part of a pair that he gifted to my mother, the other one being accidentally destroyed by a family friend who knocked it off a different mantlepiece when I was very young. I can still remember the traumatic event even though I was then < 5-years old. Close to the vase are two children's toys, a horse and a palanquin, cast in bronze, that could be antique but are probably “modern” replicas that I bought in Khajuraho, India in 1981. All of these items have meanings and evoke memories.

Other rooms have other keepsakes. However, I have no intention to describe these. Rather, in order to focus upon and illustrate the complexities of authenticity, which is a widely used term in the social sciences, especially in studies of tourism, I will examine the contents of a small box that contains a cup that sits on the bookshelf in my untidy office. Then I will consider a second cup, as well as a boxed collection of small cups that was given to me as a present.

2 Concepts

The key concept in this paper is authenticity. An authentic object or experience is one that is real, genuine, original and not artificial. Since MacCannell (1976) wrote his important work “The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class,” and his earlier paper on staged authenticity (MacCannell, 1973), the literature on authenticity, both as it relates to tourism and other subjects, has proliferated, and numerous papers have been published that review the literature (e.g., Wang, 1999; Rickly-Boyd, 2013). It is sufficient to state at this point that two emphases can be recognized, those that stress the attributes of objects and events (such as their location, raw materials, creators, design, and uses), and those that place emphasis on the experiences and evaluations of observers, both lay and expert. It is difficult to reconcile these approaches so it can be argued that authenticity is a fuzzy concept. Selby (2004) suggested that researchers have produced categories of authenticity and classifications, but have been less successful in demonstrating their utility through empirical studies.

This does not mean that the concept has limited value. In particular, elsewhere I have argued that examination of authentication, the process by which something is deemed to be authentic, can have great value (Xie and Wall, 2003; Wall and Xie, 2005). Understanding who says something is authentic and why can provide insights into the exercise of power in cultural matters.

This manuscript focuses upon souvenirs which are of significance in tourism as items of economic exchange and as representations of culture and environments (Littrell et al., 1993, 1994; Cave et al., 2013). Souvenirs are items that are in a new place in that they have been removed from their place of origin, and taken to a new location. They may or may not possess many of the attributes used to evaluate the authenticity of objects but, regardless, as reminders of significant experiences, they may have great meaning for their new owners. When displayed in their new surroundings, they may become talking points and, whether gifted or purchased, they may reveal aspects of the identity of their owners. At the same time, they may reflect aspects of the identity of those in their place of origin, although the meanings that are ascribed to them likely differ markedly.

This paper, then, reflects upon aspects of the authenticity and meanings of souvenirs that are in the possession of the author.

3 Methods

The souvenirs that will be considered are in my possession and their meanings, as discussed in this manuscript, reflect my interests and interpretations, while referring to the likely interests of others. As such, the work can be considered to be an example of autoethnography (Buckley and Cooper, 2002; Beeton, 2022). It is an attempt to connect my own situation and personal experiences with broader issues. I am male, elderly, western, an immigrant to Canada and widely traveled, much of that travel having been conducted undertaking tourism research. I have read and contributed to tourism research, including that on authenticity, for ~50 years. Much of that work has been conducted in Asia and has emphasized the uneven and often unfair distribution of the costs and benefits of tourism development (e.g., Yang and Wall, 2023).

This autoethnography is highly selective. No attempt has been made to address all of the souvenirs that are in the author's possession. Rather, emphasis is placed on specific ceramic cups acquired in Taiwan in ~2005.

4 Souvenirs of Taiwan

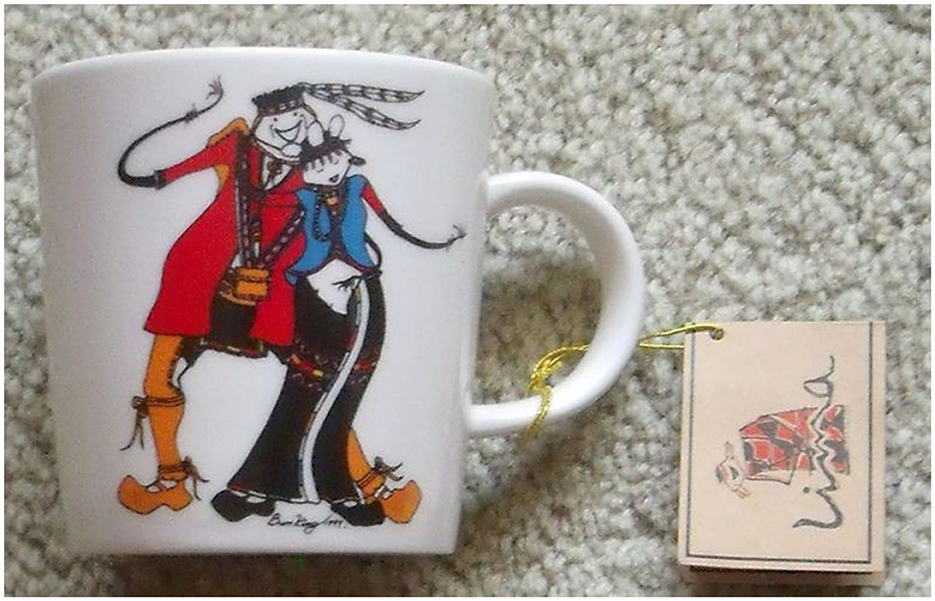

First I will consider a cup that is housed within a plain cardboard box that sits on a bookshelf in my upstairs office. I had been undertaking research on sustainable livelihoods of indigenous people in Taiwan and the roles that tourism might play in such development (e.g., Chang et al., 2008; Tao and Wall, 2009a,b) and I bought the cup in Taiwan as a souvenir (Figure 1). I brought it back to Canada, but I have never actually had a drink from it and it has remained in its box. Cups were available in a variety of designs, representing different indigenous tribes in Taiwan, and I selected one with Tsou figures because that was the tribe with which I had engaged most closely.

The cup was bought in a store that specialized in indigenous souvenirs. Having been taken there by a Taiwanese host, I felt obliged to buy something and, although there were many interesting things available for sale, I settled on the cup because I thought it was something I might use, it was reasonably priced, it would be a reminder of my research location, and it would be easy to pack and transport.

Although the store was in Taiwan, it was in the western lowlands and not in the central highlands where most indigenous people now live. Successive colonial powers had forced the indigenous people to retreat to the mountains, relinquishing the more accessible areas in which they had previously lived. Furthermore, although the shop was managed by an indigenous person, he was not Tsou.

The cup was made in Miali, in western Taiwan, a center for chinaware, by Lima Life workshop which has been in operation since 1983. According to its brochure (in box with cup), the company was founded by Ding-ko Nan, a Taiwan aborigine of the Payuma tribe, uses Japanese techniques and its products are popular and sold in European and American markets. It is stated in English: “Lima Life workshop is the presentment (sic) of aboriginal and hakka life cultures, integration between ethnic groups, and mutual appreciation of culture… and integrates local lives.”

LIMA is also the name of a Taiwan Indigenous Youth Working Group that was initially organized in 2006 by Tuhi Martekaw, then a student in the Department of Diplomacy, National Chenchi University, and formalized in 2013. He went with the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy to a United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues to make connections for further activism on international issues concerning aboriginal people (Tang, 2021).

I am uncertain if such a cup was used by Tsou people. In traditional settings I had previously been offered tea from cups made from bamboo and coffee from mugs. I had not seen cups quite like this before and, on reflection, I doubt that such cups were designed for the local market. The cup is marked TSOU, TAIWAN ABORIGINAL and LIMA. Lima means “hand” and is common to many Austronesian languages, the languages of many of Taiwan's aboriginal people (and here I am using the words aboriginal and indigenous interchangeably).

The tag, which is still attached to the cup, reads as follows:

TSOU TRIBE:

POPULATION: 6,000

LOCATION: ALISHAN (which is located in the central mountains)

TOWNSHIP OF CHIAYI (which, perhaps coincidentally, is where my host was then based)

GIOMI VILLAGE IN THE HSINYI TOWNSHIP OF NANTOU (also located in the central mountains)

Such brief descriptions of the tribe(s) that is (are) represented in the products are provided. It is helpful and appropriate to provide such information but this does not mean that it was made in their territory for the company is located in Miali.

Somewhat curiously, the design of the male and female Tsou people on the cup is cartoonish. Some might regard this as disrespectful. A co-authored book, that may be the most significant thing I have written, has a cartoon figure on the cover (Mathieson and Wall, 1982). We were not consulted on this. However, I know that my co-author was appalled, feeling that our attempt to encourage readers to take tourism seriously was undermined by the cover design. It seems, however, that the design of the cup was acceptable to at least some Tsou people. While writing this manuscript, I found another cup, a gift, made by the same company with a geometric design representing the Puyuma tribe and of slightly different shape from the Tsou cup (Figure 2), although I have had no contact with the Puyuma people, I prefer this cup finding it both more attractive and more respectful than the one I bought. I am unsure exactly how I got this cup and it does not evoke the same memories

However, this is not the end of the story. Subsequently, I was given a set of small cups, of somewhat similar design to the larger cup that I have described (Figure 3). Does it make a difference that one was purchased and the others were a gift? Certainly, the process of acquisition was different and the associated meanings also differ.

Each of the set of twelve cups has a design that represents a different Taiwanese aboriginal tribe. The cups are very small and do not have handles. Indeed, they are less suitable for serving tea than serving strong liquor, such as saki. However, I rarely drink such liquor so the larger cup, although I have yet to drink out of it, was expected to receive more use than the smaller cups.

I understand that the most prominent market for the sets is Japanese visitors and that the sets are also marketed directly to Japan. From 1895 to 1945 Japan ruled Taiwan as a colonial power. During this time, many aspects of indigenous culture were suppressed, including tattoos, hunting, traditional weaving, and aboriginal languages (Yoshimura and Wall, 2010). In our research we found that some older aboriginal people could speak Japanese but were unable to speak their aboriginal tongue. Also, we found that traditional weaving designs that had been extirpated were being painstakingly recreated using microscopes and photographs of the originals that are now housed in museums in Japan (Yoshimura and Wall, 2014). The boxed sets of cups, therefore, are potentially reminders of a colonial past. As the status of Taiwan is currently contested and the future is uncertain, Taiwan's aboriginal people, although making some political and socio-economic gains under the present political system, face an unknown future as great powers position themselves over the right to rule their territory.

When the set of cups was given to me as a gift, Taiwan had 12 officially recognized aboriginal tribes. The criteria used for their designation were essentially inherited from the Japanese colonial rulers (Yoshimura and Wall, 2010). Official recognition is a political act. According to the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (2023), the officially recognized Indigenous population of Taiwan numbers 571,816 people (2019), or 2.42% of the total population and now sixteen distinct Indigenous Peoples are officially recognized. In addition, there are at least 10 Pingpu Indigenous Peoples who are denied official recognition. The main challenges facing indigenous peoples in Taiwan continue to be rapidly disappearing cultures and languages, low social status and very little political or economic influence. The same site (International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, 2023) states that the Council of Indigenous Peoples (CIP) is the state agency responsible for indigenous peoples. A number of national laws protect their rights, including the Constitutional Amendments (2000) on indigenous representation in the Legislative Assembly, protection of language and culture and political participation; the Indigenous Peoples' Basic Act (2005), the Education Act for Indigenous Peoples (2004), the Status Act for Indigenous Peoples (2001), the Regulations regarding Recognition of Indigenous Peoples (2002) and the Name Act (2003), which allows indigenous peoples to register their original names in Chinese characters and to annotate them in Romanized script. Serious discrepancies and contradictions in the legislation, coupled with only partial implementation of laws guaranteeing the rights of indigenous peoples, have stymied progress toward self-governance. Since Taiwan is not a member of the United Nations it has not been able to vote on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, nor to consider ratifying ILO Convention 169 (the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989).

Being aboriginal in Taiwan is to live in a fluid situation. Twelve small cups fit nicely in a box; 13 do not. Sixteen may be too many to make a desirable present that is competitively priced. The official addition of tribes would seem to necessitate an increase in the range of offerings, require the addition of more cups to the set, unless incomplete sets are to be sold or formerly unrecognized tribes ignored, in spite of their newly won political status.

5 Conclusion

Through the examination of souvenirs in the author's possession and their meanings, it has been shown that authenticity is a slippery term. Classifications, such as objective, constructive and existential authenticity, as proposed by Wang (1999), are useful in that they draw attention to different attributes of objects and different emphases in the literature. However, many objects, including many souvenirs, do not fit snuggly into classifications, for meanings may be personal, vary and may even change over time. Authenticity is a word that should be used with care and that can both draw attention to and hide issues of power and powerlessness. For this reason, it may be useful to give more attention to authentication, the process by which something is deemed to be authentic, rather than authenticity per se (Xie, 2010). Who says something is or is not authentic and why? The search for answers to such questions will require that the multiple dimensions of authenticity are addressed, and will require exploration of the variations in power that underpin them. Ultimately, then, reflections on meaning of objects and their authenticity, may reveal insights into identities and the relationships between their creators and those who have come to possess them.

Being based primarily on personal reflection, which is a limitation of autoethnography, this article has not evaluated the perspectives of the various stakeholders and their reasons for regarding items as authentic or inauthentic. This requires more rigorous research, as suggested by Xie et al. (2012), who also studied similar cups in Taiwan. They found that tourists perceive modern design combined with indigenous markers to be more authentic than traditional design, and their willingness to purchase was associated with their perceptions of authenticity in design. However, the perspectives of manufacturers and those whose cultures have been represented have yet to be determined, and present opportunities for further research.

As I think about my souvenirs, I am also note that I am a European settler living in Canada in a place that was once the territory of indigenous people. What should one make of the “authentic heritage homes” that are currently being built on land that may or may not have been ceded by aboriginal/indigenous people a century or two ago?

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

GW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Beeton, S. (2022). Unravelling Travelling: Uncovering Tourist Emotions through Autoethnography. Leeds: Emerald Publishing.

Buckley, R., and Cooper, M. (2002). Analytical autoethnography in tourism research: when, why, how, and how reliable? Tour. Rec. Res. 24, 2155784. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2022.2155784

Cave, J., Jolliffe, L., and Baum, T. (2013). Tourism and Souvenirs: Glocal Perspectives from the Margins. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Chang, J., Chang, C. L., and Wall, G. (2008). Perception of the authenticity of Atayal woven handicrafts in Wulai, Taiwan. J. Hosp. Leisure Market. 16, 385–409. doi: 10.1080/10507050801951700

Graburn, N. H. H. (1977). Ethnic and Tourist Arts: Cultural Expressions from the Fourth World. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (2023). Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan. Available online at: Wgia.org/en/Taiwan.html (accessed November 17, 2023).

Littrell, M., Anderson, L., and Brown, P. (1993). What makes a craft souvenir authentic? Annal. Tour. Res. 20, 197–215. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(93)90118-M

Littrell, M. A., Baizerman, S., Kean, R., Gahring, S., Niemeyer, S., Reilly, R., et al. (1994). Souvenirs and tourism styles. J. Trav. Res. 33, 3–11. doi: 10.1177/004728759403300101

MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: arrangements of social space tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 79, 589–603. doi: 10.1086/225585

MacCannell, D. (1976). The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. New York, NY: Schocken Books.

Mathieson, A., and Wall, G. (1982). Tourism: Economic, Physical and Social Impacts. London: Longman.

Rickly-Boyd, J. M. (2013). Existential authenticity: Place matters. Tour. Geograph. 15, 680–686. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2012.762691

Tang, Z. X. (2021). Bringing the Voice of Taiwan Indigenous Peoples to the World. Indigenous Sight. Available online at: https://insight.ipcf.org.tw/en-US/article/436 (accessed June 24, 2021).

Tao, T., and Wall, G. (2009a). Tourism as a sustainable livelihood strategy. Tour. Manage. 30, 90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.03.009

Tao, T., and Wall, G. (2009b). A livelihood approach to sustainability. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 14, 137–152. doi: 10.1080/10941660902847187

Wall, G., and Xie, P. (2005). Authenticating ethnic tourism: Li dancers' perspectives. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 10, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/1094166042000330191

Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annal. Tour. Res. 26, 349–370. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

Xie, P., and Wall, G. (2003). “Authenticating visitor attractions based upon ethnicity,” in Managing Visitor Attractions: New Directions, eds A. Fyall, A. Leask and B. Garrod (Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann), 107–123.

Xie, P., Wu, T., and Hsieh, H. (2012). Tourists' perception of authenticity in aboriginal souvenirs. J. Travel Tour. Market. 29, 485–500. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2012.691400

Yang, L., and Wall, G. (2023). Ethic Tourism: Impacts, Challenges and Opportunities. London: Routledge.

Yoshimura, M., and Wall, G. (2010). “The reconstruction of Atayal Identity in Wulai, Taiwan,” in Heritage Tourism in Southeast Asia, eds M. Hitchcock, V. King and M. Parnwell (Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, NIAS Press),49–71.

Keywords: authenticity, ceramics, ethnic tourism, souvenirs, Taiwan

Citation: Wall G (2024) The authenticity of souvenirs: examples from Taiwan. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1346641. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1346641

Received: 29 November 2023; Accepted: 22 January 2024;

Published: 09 February 2024.

Edited by:

Deepak Chhabra, Arizona State University Downtown Phoenix Campus, United StatesReviewed by:

Philip Xie, Bowling Green State University, United StatesNgoni Courage Shereni, Lupane State University, Zimbabwe

Copyright © 2024 Wall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geoffrey Wall, Z3dhbGxAdXdhdGVybG9vLmNh

Geoffrey Wall

Geoffrey Wall