- 1School of Outdoor Recreation, Parks and Tourism, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Strategy, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

Introduction: The interpretation of national, provincial, territorial, and state parks and heritage sites is a powerful social force that can foster or thwart respectful relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Methods: By conducting a scoping review of relevant literature, this study aims to initiate conversations about how Indigenous interpretation is conceptualized and practiced in relation to national, provincial, territorial, and state parks and heritage sites on Turtle Island (i.e., North America).

Results: Findings indicate that while Indigenous interpretation is rarely explicitly defined, several themes are consistently used to illustrate what Indigenous interpretation entails or should entail. Themes include: (i) responsibility and respect, (ii) relationships, (iii) place-based cultural identity and empowerment, (iv) contested stories and histories, and (v) storytelling.

Discussion: While these thematic dimensions do not represent a definitive definition of Indigenous interpretation, they do suggest potential features that may enhance understandings and applications of Indigenous interpretation in parks, protected areas, and heritage sites on Turtle Island. They also reaffirm the importance of interpretive encounters as a social force encouraging relationships across cultures.

Introduction

Interpretation is a key feature of public education programs in parks and tourism settings (Hvenegaard et al., 2009). The National Association for Interpretation (2024) defines interpretation as “a purposeful approach to communication that facilitates meaningful, relevant, and inclusive experiences that deepen understanding, broaden perspectives, and inspire engagement with the world around us” (no page). Pertaining to natural and/or cultural heritage, interpretation is shaped by sequential (guided tours) and/or non-sequential (signage, visitor centers, and multi-media) approaches, and by legislation and policy (Hvenegaard et al., 2009). By providing several types of information and agency messaging, interpretation is a key component of visitor experiences in national, provincial, territorial, and state parks and heritage sites (hereafter referred to as parks and heritage sites) on Turtle Island (North America). On a broader level, interpretation represents a powerful social force for fostering or thwarting respectful relationships between park and heritage site visitors and local communities, between people and place, and—most relevant to the aims of this paper—between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Amidst formal political reconciliation initiatives—such as Canada's implementation of the United Nation's Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations, 2007) and stated desire to address the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (TRC; Truth Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015)—as well as growing public awareness of the ongoing legacies of settler colonialism [e.g., recent news of unmarked graves of Indigenous children sent to Residential schools in Canada (Mosby and Millions, 2021) or boarding schools for Native Americans in the United States of America (The National Native American Boarding School History, 2023)], and movements toward Indigenous resurgence (Chew Bigby et al., 2023; Runnels et al., 2018), interpretation serves an important role. Further, whether it through the co-construction of place-base narratives, determining what stories are told, selecting whose voices are featured or amplified, and identifying how competing or contested histories are communicated to visitors (Finegan, 2019), interpretation is an important component of collaborative management approaches in parks and heritage sites (Whitney-Squire, 2016; Whitney-Squire et al., 2018).

In this article, we aim to prompt consideration of developing a robust conceptualization of Indigenous interpretation and its role in the interpretation strategies deployed by parks and heritage sites. More specifically, we present the outcomes of a scoping review of peer-reviewed of social science literature pertaining to Indigenous interpretation in by parks and heritage sites on Turtle Island. Great Turtle Island (Newcomb, 2016), or Turtle Island (Weaver, 2014), is the name several Indigenous groups use when referring to North America; a name that is tethered to creation stories and ancestral teachings (Henderson et al., 2022). By using Turtle Island, we acknowledge the historical and ongoing legacies of colonization that shape the lands we inhabit and draw recognition to the “diversity of cultures, perspectives, languages, experiences, and protocols that bring tremendous vibrancy” (Henderson et al., 2022, p. 289) across Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

The purpose of our scoping review was to identify and synthesize dimensions of a potentially emergent area of scholarship in interpretation and more specifically Indigenous interpretation (Schwandt, 2015; Torrance, 2018). This is an area of tourism, parks, and protected area management that until quite recently has been underrepresented and is required if by parks and heritage sites agencies aspire to build and maintain respectful, reconciliatory relationships with Indigenous peoples. Following the identification and compilation of relevant literature, our scoping review incorporated a thematic content analysis to examine how Indigenous interpretation is defined, understood, and discussed in by parks and heritage sites on Turtle Island. By highlighting these scholarly contributions, many of which include Indigenous scholars, our scoping review identifies potential building blocks for defining, (re)conceptualizing, and practicing Indigenous interpretation. To be sure, the development of any definitive statement on what Indigenous interpretation is or should be, must be led by Indigenous scholars, communities, and knowledge holders such that both the product (i.e., a definition) and process (i.e., the methods used to construct a definition) support practices of Indigenous resurgence (see e.g., Chew Bigby et al., 2023). Given the colonial structures that underpin by parks and heritage sites management and research (Sandlos, 2011), and the need for non-Indigenous peoples to shoulder more of the burden of unsettling colonial regimes (Grimwood et al., 2019), we also feel that non-Indigenous scholars, managers, and practitioners can be actively involved in this conversation.

By prompting such research and dialogue on Indigenous interpretation, it is important to position ourselves as authors and acknowledge the situated, partial perspectives that we convey in this article. As Smith (2012) has explained, there is a long and troubled history of research being conducted on Indigenous peoples, which perpetuates the sort of erasures and extractions that characterize colonial power. Such violence—which we understand is recurrent and ongoing as it circulates within and through various institutions [including academia (see Smith, 2012; Lee, 2017) and protected area management (see Burnham, 2012; Mason, 2014; Sandlos, 2011)]—is something that we aspire to help undo and stop, both in our research and the broader contexts of our lives. This is not easy to achieve given the subtle ways that colonial power infiltrates our scholarship and other relations (Grimwood, 2021). In the case of this article, we present a synthesis of literature and encourage further collaborations on Indigenous interpretation, which together set the stage for more advanced work in this area. These efforts are informed by our positionality as Setter scholars committed to working with Indigenous communities (Grimwood et al., 2017; Koster et al., 2012) and to destabilizing entrenched formations of settler colonial power (Grimwood et al., 2019; Grimwood, 2021; see also Tuck and Yang, 2012). Of French-Canadian settler ancestry and a certified interpretive guide, the first author has been working with and for Indigenous communities in Canada, the United States, and in Mexico for the past three decades. The second and third authors are settler Canadians of British and European ancestry. The second author is an emerging scholar with interests in ethical and culturally sensitive nature-based tourism, while the third author, who has worked with Indigenous communities in Canada over the past two decades, orients current research toward the politics and ethics of decolonizing settler colonialism. The first and third authors are currently working on the second phase of a collaborative study with Indigenous scholars examining Indigenous interpretation.

Literature review

Examinations of interpretation, especially as it pertains to the interpretation of Indigenous People's places and knowledges in by parks and heritage sites on Turtle Island include Finegan's (2019) comprehensive study of heritage interpretation in Canadian national parks. Studies have also been conducted in American national parks like Wind Cave National Park (Smaldone and Rossi, 2019), Canadian national parks, national park reserves, and provincial parks, including: Banff National Park (Mason, 2014) and Jasper National Park (Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020) in Alberta, Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site in Nova Scotia (Lynch et al., 2010), Haida Gwaii National Park Reserve in British Columbia (Whitney-Squire, 2016; Whitney-Squire et al., 2018), Kluane National Park Reserve in the Yukon Territory (Cruikshank, 2005), and Lake Superior Provincial Park in Ontario (Twance, 2019). Certain historic sites, like the Battle of Little Bighorn in Montana and the Batoche National Historic Site in Saskatchewan, have compelled Indigenous activists and others to address and rectify historical inaccuracies within interpretation contexts and provide opportunities for Indigenous perspectives to be told (Hvenegaard et al., 2016; Lemelin et al., 2013).

As both Finegan (2019) and Couts (2021) argue, by parks and heritage sites are places where the presence of Indigenous Peoples and histories are often erased, settler-colonial power is operationalized, and nation-building is legitimized. According to Johnston and Mason (2021), the Indigenous content provided in interpretive strategies in by parks and heritage sites are often framed within Eurocentric perspectives that “trivialize many aspects of Indigenous histories and continue to perpetuate damaging stereotypes of Indigenous people” (p. 21). Further, Eurocentric perspectives tend to temporalize Indigenous cultures and histories as part of the distant past (Twance, 2019). This temporalization renders colonial oppression as historical and thus apolitical, while simultaneously ignoring the agency of contemporary Indigenous lives (Braun, 2002; Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020). According to Twance (2019), management agencies leverage policy and legislation to marshal and maintain control over what information and narratives are conveyed, how, and by whom. Such state-authorized control is, however, not impermeable. For instance, as Lynch et al. (2010) observe, the Mi'kmaw Peoples in Kejimkkujik Nation Park control and decide what they are willing to share with visitors (e.g., certain stories or legends) and what they are not willing to share (e.g., medicines, ceremonies, and sacred areas).

Several years ago, Runnels et al. (2018) produced an Indigenous interpretive strategy titled “Giving voice to our First Nations: Creating a framework for Indigenous interpretation through education and collaboration.” The themes of the interpretive strategy included: respect for local peoples, places, and protocols; control over which narratives are shared and when; connections for local people and visitors to places, cultures, and other beings; capacity-building for youth and locals to tell their own stories; and governance and empowerment. The framework reported by Runnels et al. (2018) is consistent with Johnston and Mason's (2020) assertion that Indigenous Peoples “want increased representation and greater control over how their histories and cultures are presented” (p. 1), a vision that can only be realized if interpretive strategies support more respectful, accurate, and self-determined depictions of Indigenous Peoples as interpreted by Indigenous peoples themselves.

Around the same time that the Runnels et al. (2018) strategy was released, the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC) published a comprehensive set of guidelines pertaining to Indigenous tourism (Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada, 2018). Indigenous tourism, as it is conventionally defined in the literature, refers to a “tourism activity in which Indigenous People are directly involved either through control and/or by having their culture serve as the essence of the attraction” (Hinch and Butler, 1996, p. 9). Rather “than Indigenous people being merely the passive producers of tourism experiences” (Nielsen and Wilson, 2012, p. 2), Indigenous ownership of tourism enterprises promotes agency and ensures the control of the product and delivery of what knowledges are shared and not shared (Nielsen and Wilson, 2012). According to ITAC, authentic Indigenous tourism operations are those that demonstrate connections to local Indigenous territories and cultures and that are majority owned, operated, and/or controlled by First Nations, Métis, or Inuit peoples. These operations should also be developed and reviewed under the direction of Indigenous Peoples and approved by the cultural keepers (such as Elders or hereditary Chiefs; Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada, 2018). These broader contexts of Indigenous tourism suggest the importance of Indigenous control over interpretation strategies as means for supporting sovereignty, cultural connections, and visitor experience. Indeed, positive interpretive encounters, according to Lynch et al. (2010), can become a social force encouraging more ethical, hopeful, and respectful relationships across cultures by fostering greater intergenerational and intercultural awareness of Indigenous territory and livelihoods; improving protections of traditional lands; and generating socio-cultural-economic opportunities for Indigenous communities.

Scoping review

Munn et al. (2018), Peters et al. (2015), and Peterson et al. (2017) suggest that scoping reviews are commonly used as a literary reconnaissance of emerging fields and practices such as community protection (Beans et al., 2019), the role of storytelling in Indigenous health (Rieger et al., 2020), the resilience in Indigenous youth (Toombs et al., 2016), and Indigenous mental health in a changing climate (Middleton et al., 2020). Scoping reviews, suggest Peters et al. (2015), are “particularly useful when a body of literature has not yet been comprehensively reviewed [or when clarification of] working definitions and conceptual boundaries of a topic or field” are needed (p. 141).

This study used a scoping review which consisted of thematically analyzing English language social science journal articles pertaining to interpretation and associated with parks and protected areas management, heritage site management, and tourism. While no date boundary was established for this scoping review, the review ended in 2023, when the article was first submitted for publication. Articles were retrieved from searching four journal databases: Scopus, ERIC, ProQuest, and Scholars Portal. These search databases were selected for this study as they contain extensive collections of peer-reviewed titles and citations from journals, books, and government reports. Additionally, holdings within these databases provide access to full-text versions of articles. We focused specifically on English sources given our team's language capabilities and the dominance of English publications in the field of parks and protected areas. Although several published works associated with museum studies (see Bench, 2014; Peers, 2007), protected natural areas not specific to Indigenous Peoples (see Hughes et al., 2023; Moscardo and Hughes, 2023), and protected areas outside of North America (see Howard et al., 2001; Moscardo, 1998; Staiff and Bushell, 2002) have been conducted, we excluded these from our review because they fell outside of the geographical region of interest and analytical focus.

In this article, we engage with several concepts that warrant brief explication. Turtle Island, as previously noted, is often associated to Canada, the United States, and Mexico. The focus of our review, however, is placed on articles relating to Canada and the United States given the history and scope of management and scholarship on parks, protected areas, and heritage sites in these countries (Finegan, 2019; Hvenegaard et al., 2009). When referring to Indigenous Peoples, we have followed the definition of the United Nation's State of the World's Indigenous Peoples (SOWIP) which states:

Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them (United Nations, 2009, p. 4).

Additionally, and aligned with norms established by Indigenous Peoples living in Canada, we understand the term Indigenous to refer to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (Vowel, 2016). We take up the terms national, provincial, territorial, and state parks as those areas managed for ecological and/or recreational purposes by federal or provincial, territorial, or state agencies on Turtle Island. Heritage sites denote cultural and historic areas managed similarly by several types of government agencies. While we adopt commonly accepted (and in most case, officially sanctioned) definitions, we also recognize that the terms referred to above are neither universal nor stable. Relatedly, these terms are situated within, and informed by, legacies of settler colonialism and moves toward reconciliation and Indigenous resurgence (Finegan, 2019).

Preliminary search of terms

Our scoping review process consisted of four steps. The first involved a preliminary search of terms using the Scopus database. Advanced filters were applied to ensure that all entries retrieved were from park management, tourism, and social science journals, and that all results would be peer-reviewed journal articles. Combinations of the following search terms were used to facilitate this search: North America, Canada, USA, Indigenous interpretation, Indigenous, park interpretation, national, provincial, territorial, and state parks, and heritage sites. This initial search yielded only six results. Accordingly, we expanded the preliminary search to include three other journal databases—ERIC, ProQuest, and Scholars Portal—with the expectation that additional articles would be retrieved. Search terms were also expanded at this point to include cultural tourism and Indigenous guides. Expanding the search to include four databases yielded a total of 40 articles. Based on previous studies (authorship withheld for reviewing purposes) and discussions pertaining to scoping reviews (Beans et al., 2019), we deemed this number of articles sufficient to proceed onto the next stage of the review process.

Primary scan of abstracts

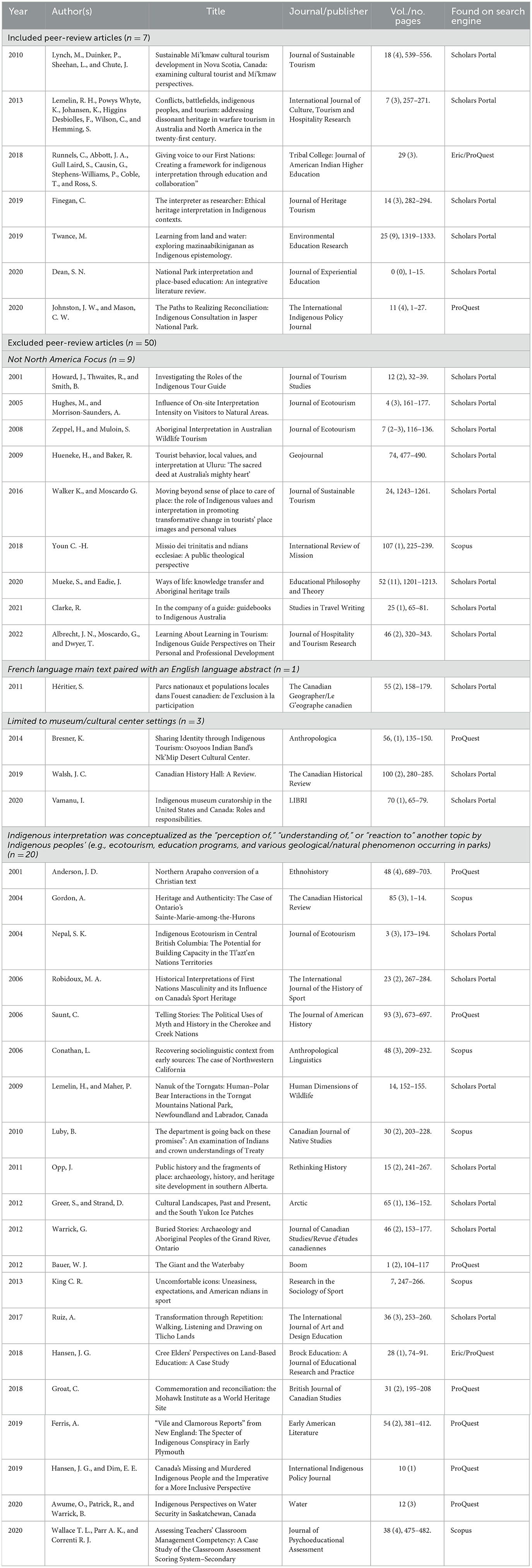

Following the preliminary search, the abstracts of all identified articles were read. Based on the abstracts, several articles clearly fell outside of the aims and scope of our scoping review and were excluded. This included articles that were not based in North American (n = 9), had French language main text paired with an English language abstract (n = 1), and were focused on museum or cultural center settings (n = 3). Significantly, 20 additional articles were excluded from analysis on the basis that Indigenous interpretation was conceptualized as the “perception of,” “understanding of,” or “reaction to” another topic by Indigenous Peoples (e.g., ecotourism, education programs, and various geological/natural phenomenon occurring in parks). In other words, Indigenous interpretation was referred to fleetingly in these articles. Following the preliminary scan of abstracts, seven articles remained (see Table 1).

Expanded search

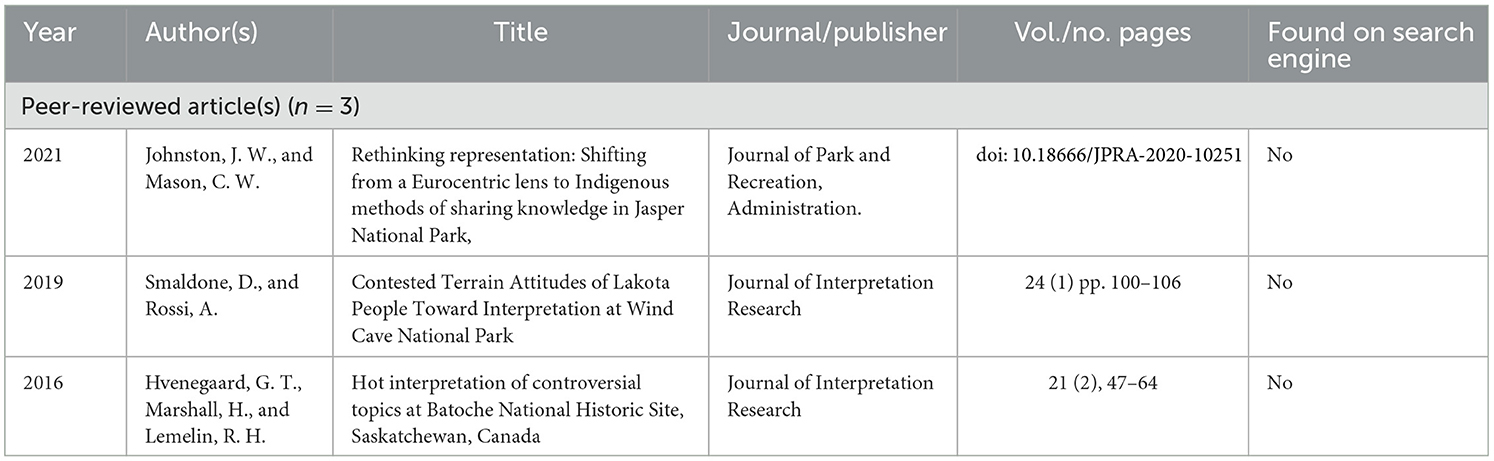

Of concern to the first author who has been teaching and documenting references regarding how Indigenous interpretation is applied (or not) in national parks on Turtle Island, was the absence of certain peer-reviewed articles from the preliminary scoping review (see Table 2). Beyond noting that most systematic and scoping reviews “do not check for, nor account for, missing data” (Abou-Setta et al., 2016, n.d.o page), the research team was provided with little guidance on this issue. After much deliberation, the research team concluded that these exclusions may be more indicative of challenges with certain search engines or scoping reviews. Further, considering that all three articles were peer-reviewed and meet our original search preliminary search of terms, we decided to include the three articles in the analysis, thereby bringing the list up to 10 articles.

Thematic content analysis

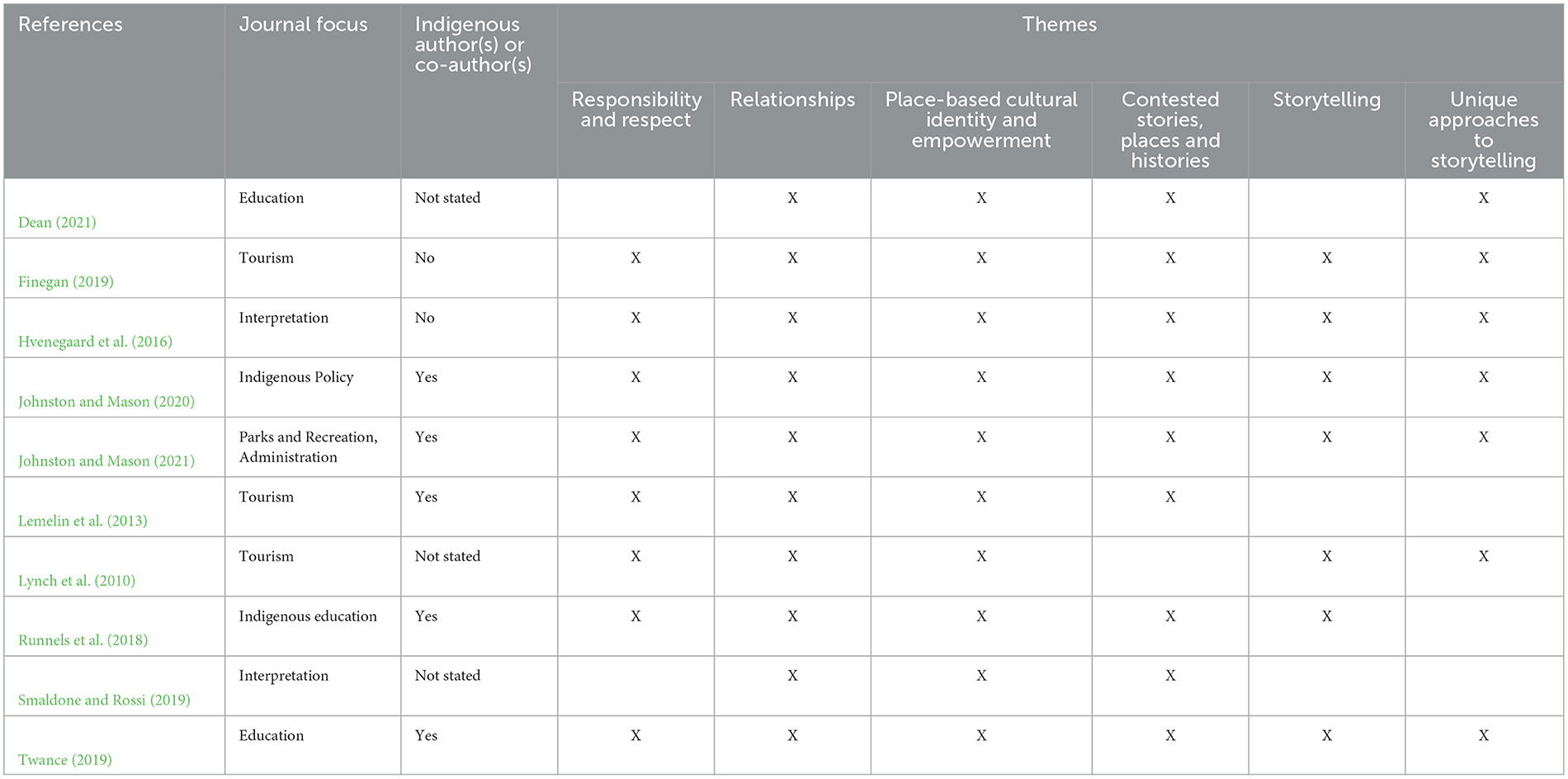

In all, 10 articles were identified in the scoping review and deemed suitable for inclusion in the review. Five of the 10 articles were authored or co-authored by scholars identifying as Indigenous citizens of Turtle Island (Lemelin et al., 2013; Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020; Runnels et al., 2018; Twance, 2019). After reading all 10 articles in detail, we used an in-depth, inductive approach to content analysis to identify central and cross-cutting themes. Themes were identified based on descriptive contents (i.e., how a word, concept, or idea was mobilized in the research), as well as the frequency of occurrence and emphasis within the literature (i.e., the relative importance that a word, concept, or idea seemed to Indigenous interpretation).

More specifically, the first and second authors led the analysis by following Braun and Clarke's (2006) multi-phased, flexible, and reflexive thematic analysis approach “for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (p. 79). First, as the articles were reviewed, initial impressions and insights were noted. Next, we conducted a coding process to assign meaningful units of text with a code (or multiple codes). These codes were then organized in a spreadsheet for further examination and thematic refinement. Thematic mapping was the next step and was used to visualize relationships between potential themes and sub-themes. Themes were then defined and named according to our theoretically informed interpretations of “what each theme is about (as well as the themes overall) and determining what aspects of the data each theme capture” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 92). Ultimately, Braun and Clarke's (2006) flexible approach proved congruent with identifying, synthesizing, and interpreting recurring themes. Table 3 illustrates the emergent themes in relation to the articles included in the scoping review. Our analysis approach generated themes that usefully convey what Indigenous interpretation does and/or should entail. In the following section, we explain these five themes (themes five and six storytelling and unique approaches to storytelling outlined in Table 3 were combined in-order to facilitate this discussion) and describe how they are presented in these articles.

Results

The 10 articles included in the scoping review mobilized several concepts to illustrate what Indigenous interpretation does and/or should entail in parks and protected areas and heritage sites in North America. The review identified five themes: (i) responsibility and respect, (ii) relationships, (iii) place-based cultural identity and empowerment, (iv) contested stories and histories, and (v) storytelling and unique approaches to storytelling. The five themes should be interpreted as interrelated, and not mutually exclusive—each theme is underpinned by and responds to the historical and ongoing impacts of settler colonialism on cultural and land-based Indigenous identities. We explain and discuss each central theme in the subsequent sections.

Responsibility and respect

The theme emphasized most in the literature reviewed related to topics of responsibility and respect. Responsibility and respect are seen to be foundational to remembering and acknowledging the complex and ongoing legacies of colonialism presented in interpretative contents—broadly and within situated context of specific lands and Indigenous Peoples (Finegan, 2019; Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020). Responsibility emphasizes ethical obligations of (settler) interpreters in their role as critical researchers and stewards of the stories that they tell on and of park lands and histories (Finegan, 2019). Responsibility recognizes the power of interpretation to privilege certain knowledges or understandings of place, subjecting others to erasure and/or selective inclusion or distortion (Finegan, 2019; Lemelin et al., 2013). According to Finegan (2019):

“Interpreters are gatekeepers, adjudicating knowledge and privileging some of it over other knowledge. Interpreters are much more than communicators and interpretation itself is more than an art. It is a powerful exercise of power that can erase or advance particular understandings” (p. 291).

To be responsible, interpretation needs to engage with multiple meanings of place by meaningfully engaging with uncomfortable histories of Indigenous erasure and dispossession in the national park systems of North America (Finegan, 2019; Twance, 2019).

Interpretation also carries with it an onus of responsibility for story stewardship—that is, caring for and respecting, not only, the stories themselves but the peoples and knowledges, as well as lands to which they belong (Finegan, 2019). This responsibility for story stewardship involves a recognition that “Indigenous knowledge is part and parcel of the community in which it originates; it is not something to be learned quickly and extracted from its context” (Finegan, 2019, p. 288). Responsible stewardship in interpretation requires building strong relationships with local Indigenous peoples by park managers and interpretative staff founded on trust and respect. That is, a trust that stories will be shared with care and in a culturally appropriate way and with respect for the community, as well as Indigenous cultures, traditions, interests, and worldview (Lynch et al., 2010). The theme of responsibility and respect—by interpreters and in relationships—demands that decisions by a community not to share certain stories and cultural/sacred sites with outsiders are observed (Lynch et al., 2010), and that Indigenous peoples are actively involved in decisions with interpretive staff and park management around how they are represented (Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020). In their research with the Jasper (National Park) Indigenous Forum (JIF), Johnston and Mason (2020) assert, “JIF members want their histories told, their cultures respected, and cultural sites protected, their youth to find pride in the connection to their traditional lands, and to have control over how they are represented within the park” (p. 8). Within the literature, this theme highlights an onus of responsibility in Indigenous interpretation for respectfully engaging and empowering Indigenous peoples to tell their own stories, from their own perspective, in their own voice, and on their lands (Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020; Runnels et al., 2018).

Relationships

The second most prominent theme emerging from our review is relationships. The theme of relationships emerges in the literature in several ways, the first of which (featured above) relates to the need for building strong relationships based in trust and respect among interpreters, park managers and Indigenous peoples. Relationships also emerge as a theme with respect to Indigenous worldviews and epistemologies. Indigenous knowledge is relational and holistic—that is, knowledge, peoples, lands, nature, and the spiritual world are connected to one another and knowledge, itself, is an ongoing relation with all of creation (Finegan, 2019; Runnels et al., 2018). Knowledge as relationships confers an embodied responsibility within relationships with more-than-human existence. Knowledge is a “process of participating fully and responsibly in such relationships, rather than specifically the knowledge gained from such experiences” (Finegan, 2019, p. 289). Knowledge as relationships is situated within the very relationships that shape this world and within the relational places that shape knowledges, and thus, are place-based. Indigenous worldviews offer a stark contrast to scientized Western ways of knowing that separate knowledge and knowers from the things that they know about, divorcing knowledge from place and specific experiences in the interest of generalizability (Finegan, 2019).

The place-based nature of relationships is also an important for consideration for Indigenous interests pertaining to national Park and protected area lands. In acknowledging the violence of colonial histories which impaired Indigenous access to traditional territories or cultural sites—now occupied by national parks like Jasper, in the Canadian Rockies, Kejimkujik in the Canadian Maritimes or the Batoche National Historic Sites in Saskatchewan—the theme of relationships is also tied to dialogues and activities related to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples -including stated objectives of improving Indigenous/non-Indigenous relations in Canada, rebuilding relationships premised on co-operation and partnership, and recognizing rights (Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020; Hvenegaard et al., 2016; Lynch et al., 2010). Dialogues and actions need to demonstrate that park agencies are willing to address and rectify the erasure of Indigenous peoples from these areas (Johnston and Mason, 2020). The theme of relationships, then, enters how rights to lands and other interests related to cultural sites, traditional territories, and practicing traditional ways of life by Indigenous nations with traditional claims to park and protected area lands are advocated for, integrated, recognized, and addressed in management practices and within park interpretation (Johnston and Mason, 2020; Lynch et al., 2010). For many by parks and heritage sites, this means developing relationships with Inuit, First Nation, and Métis peoples, sometimes as a group (in the case of collaborative management approaches in the Torngat Mountains National Park, or the Jasper National Park Indigenous Forum) or as individual nations, each of which represents a different stakeholder interest in the management of by parks and heritage sites (Lemelin and Baikie, 2012; Lemelin et al., 2013; Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020). In many ways, the relationship theme of interpretation traverses all intersections of Western/non-Indigenous and Indigenous relationships. Relationships involve everything from differing worldviews to the recognition of rights and uncomfortable histories (and ongoing impacts of settler colonialism). Further, relationships involve the cultivation of new relationships with tourists who learn of Indigenous peoples ongoing presence and their cultural and historical connection to national park and heritage sites.

According to Runnels et al. (2018), fostering intergenerational relationships between Indigenous youth and elders is key to Indigenous interpretation strategies. As such, Indigenous communities should ensure the inclusion of Indigenous youth when developing interpretive contents as it exposes youth to Elders' cultural knowledge and promotes a sense of connection with place (Lynch et al., 2010; Runnels et al., 2018). Further, involving Indigenous youth in interpretation is seen to contribute toward “preserv[ing] culture and instill[ing] a sense of pride among younger generations” (Lynch et al., 2010, p. 550).

Place-based cultural identity and empowerment

The third theme identified in the interpretation literature is that of place-based cultural identity and empowerment. Indigenous knowledges and cultural identities are often community-specific and place-based, which is why park and protected area lands may hold multiple meanings and cultural significance among different Indigenous communities with ties to National Park and protected area lands (Johnston and Mason, 2020). Within the interpretation literature, the idea that cultural identities are place-based calls for interpretative contents that are locally informed and culturally appropriate to the peoples, lands, nature, and relationships to whom the stories and practices belong. Place-based cultural identity recognizes that not all cultural stories or practices can be shared with the public and this is decided on a case-by-case basis (Runnels et al., 2018). Fundamentally, the theme of place-based cultural identity and empowerment is underpinned by an orientation to interpretation premised on each local community's right to self-determination (Johnston and Mason, 2020; Lemelin et al., 2013).

Achieving goals of locally-informed and culturally appropriate interpretation requires working with local Indigenous communities on interpretive contents (founded on themes of relationships, responsibility and respect), and to do so in such a way that local Indigenous peoples are able to reconnect with their traditional territories in parks and empowered to determine the “representations of their histories and cultures—stories told by their own people with their own voices” (Johnston and Mason, 2020, p. 22). In the literature, interpretation should maintain Indigenous ownership over the dissemination of cultural practices and knowledge, and where possible, stories should be told by the Peoples themselves and not on their behalf (Lynch et al., 2010). Empowering local communities to tell their own stories is also seen to contribute to strengthening place-based cultural identity and social wellbeing by encouraging “personal and community growth” (Lynch et al., 2010, p. 549). Further, by incorporating Indigenous place names and language in interpretative contents, it is thought that the competing stories of place can be brought to the forefront by illuminating the ways in which the “English replacements [of Indigenous place names] obscure original meanings” (Twance, 2019, p. 1,325), and subject the cultural significance of lands and its Indigenous peoples to erasure (Twance, 2019). Taken together, the Indigenous interpretation literature for North American park and protected areas suggests that cultural tourism can help preserve and protect Indigenous culture and cultural identity (Lynch et al., 2010), when interpretative contents are locally informed, culturally appropriate, and self-determined, and local communities are empowered to tell their own stories in their own voice.

Contested stories and histories

The fourth theme highlights historical conflicts between colonial and Indigenous forces like the Battle of Little Bighorn in the U.S. (Lemelin et al., 2013) and Batoche in Canada (Hvenegaard et al., 2016). This theme also outlines how some of these areas which would later become parks and heritage sites, would perpetuate the ongoing legacies of settler colonialism (Finegan, 2019; Smaldone and Rossi, 2019). The theme of contested stories and histories specifies that “landscapes and resources have multiple, culturally specific meanings associated with them” (Finegan, 2019, p. 283), and that Indigenous voices have been, and may continue to be “muted or lost at complex and controversial heritage sites” (Runnels et al., 2018, n.p.). The particular emphasis of this theme is how Eurocentric perspectives, Western science, and “colonial narratives of progress” (Johnston and Mason, 2020, p. 11), conflict with Indigenous histories of place and the cultural significance and meanings associated with traditional territories in parks and sometimes heritage sites (Lemelin et al., 2013). Further, that the re-naming of places and use of the English language in interpretation programs has served to obscure, bias, or erase Indigenous relationships to place (present and past; Lemelin and Baikie, 2012; Twance, 2019).

The literature rebuffs the notion that interpretation in by parks and heritage sites and specifically Indigenous interpretation, can be captured in tidy cohesive narratives of place (Couts, 2021; Johnston and Mason, 2020). Rather, all interpretation should recognize and attempt to meaningfully engage with places for their competing and conflicting histories and cultural significance (Finegan, 2019; Johnston and Mason, 2020). Indigenous interpretation in parks and heritage sites must recognize multiple-perspectives including those of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, across different Indigenous communities, and even within specific-communities (Finegan, 2019; Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020; Twance, 2019). More importantly, the theme of contested stories and histories also recognizes that contextual histories, including forced removal from park lands has had material and cultural consequences for Indigenous peoples (Johnston and Mason, 2020). Contextual histories may also impact on individual understandings of places or cultural sites. For example, the mazinaabikiniganan or pictographs found on rock formations along Agawa Bay, Lake Superior, are subject to many meanings and understandings by local Indigenous peoples—the “meanings [of the images] are derived from a very specific context that is not universal” (Twance, 2019, p. 1,327). The theme of contested stories and histories emphasizes the importance of Indigenous interpretation in parks and heritage sites to present these places for their multiple and contested significance and understandings and not, despite them.

Storytelling and unique approaches to storytelling

Storytelling is a theme that features prominently in the literature reviewed because it is seen as integral to the oral histories and traditions of Indigenous knowledge-sharing (Lynch et al., 2010; Runnels et al., 2018). According to Twance (2019), “stories make a home out of the world” (p. 1,328). Storytelling is a way of sharing knowledge that is culturally appropriate and representative of many truths—whether they be traditional stories or those of individual community member's lived experiences (Twance, 2019). Locally informed meanings of place are shared through storytelling and contribute to intergenerational knowledge connecting Elders to youth (Runnels et al., 2018; Twance, 2019). Within Indigenous interpretation, storytelling offers a way of conveying the cultural significance and meaning of places or sites, cultural teachings around roles and responsibilities toward a more-than-human world, knowledges of natural systems/nature, and the traditions and history of communities in national park or heritage sites (Finegan, 2019; Runnels et al., 2018; Twance, 2019).

In Indigenous interpretation, storytelling offers a way to resist representations of Indigenous histories and cultures that are temporally isolated, relegated to the past tense, and/or disconnected from contemporary Indigenous peoples and their ongoing relationships to park and protected area lands (Finegan, 2019; Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020; Twance, 2019). In the literature reviewed, storytelling by Indigenous peoples—specifically, their own stories in their own voice –is seen to possess powerful abilities to educate non-Indigenous tourists, enhance intercultural connection, and validate place-based Indigenous histories and culture (Lemelin et al., 2013; Lynch et al., 2010). Storytelling recognizes the importance of stories for culturally appropriate knowledge-sharing by Indigenous communities, and further, that “histories are embedded in the places and the stories that have been passed down from generation to generation within our [Indigenous] communities” (Twance, 2019, p. 1,329). The theme of storytelling is underpinned by relationships of respect and trust for the communities whose stories are being shared and for the contents being shared.

Overview

Dean (2021) suggested that Indigenous interpretation, like storytelling and the four other themes outlined above, should be perceived as a respectful dialogue between two parties (interpreter and tourist) and should not be approached as a one-way, didactic presentation (oral or written). From this perspective, Indigenous citizens are defined as equal partners and co-creators in the development and delivery of all interpretive components relating to their histories, culture, traditions, etc., whether those contents are to be delivered orally by interpreters (ideally a local community member) or in a cultural center, visitor center, exhibits, or on park signage (Finegan, 2019; Johnston and Mason, 2020; Runnels et al., 2018). Whether it is guided walks and formal talks, to exhibits and self-guided or interactive tours, or even through written accounts that are circulated in brochures and signage (Finegan, 2019), the use of Indigenous languages and places names can be centered to help ensure that oral traditions complement, or expand upon, written and archaeological accounts of places, traditions, culture, and histories (Finegan, 2019; Twance, 2019).

Conclusion

The purpose of this article has been to present thematic outcomes derived from a scoping review of literature on Indigenous interpretation in by parks and heritage sites on Turtle Island. Our aim has not been to identify, develop, or otherwise put forward a definitive definition of Indigenous interpretation, but rather to compile and synthesize relevant literature that may prompt more concerted attention to how Indigenous interpretation is conceptualized and practiced. Like any research, our scoping review should be read as “coming from somewhere”—meaning that the research is situated, context-specific, and partial (see Haraway, 1988). Given that the research team members all identify as settlers, we have been cautious throughout the article to avoid prescribing what Indigenous interpretation is or ought to be. Our aims have been more suggestive and, we hope, to be useful in sparking conversation in park and protected area research and practice and initiating future collaborative research with Indigenous partners. Indeed, this scoping review—which, to our knowledge, is the first (but hopefully not the last) to showcase how various scholars, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike, have conceptualized or applied Indigenous interpretation—sets the stage for broader, more concentrated discussion about Indigenous interpretation within and beyond the contexts of by parks and heritage sites.

Overall, the outcomes of this scoping review shed light on at least three general features associated with the scholarly literature on parks and protected areas on Turtle Island. First, search engines appear to be limited in their capability of finding peer-reviewed and published works on Indigenous interpretation. From history, education, to parks management, the multi-disciplinary aspects (or diversity) of the field of interpretation, hindered the search, and made finding these few works, even more challenging. For example, two of the articles not located in the initial search were published in the Journal of Interpretation Research (Sage Journals). The other was located in the Journal of Park and Recreation, Administration (Sagamore-Venture Publishing). The limited searchability of interpretation-based scholarship within the fields of history, education, and parks management, and among well-known journal databases (i.e., Scopus, ERIC, ProQuest, and Scholars Portal) poses a particular problem for scholars contributing to and interested in engaging with these topics and the dialogues shaping Indigenous interpretation now and into the future.

Exclusions of these and other works in the scoping review demonstrates how the prevalence of English peer-reviewed articles and knowledge hierarchies continue to shape the scholarship relating to Indigenous peoples and thereby further contributes to cultural erasure. Nevertheless, with further critical analysis (see Finegan, 2019; Mason, 2014; Twance, 2019) and engagement with Indigenous authors/co-authors (Lemelin et al., 2013; Johnston and Mason, 2021, 2020; Runnels et al., 2018; Twance, 2019), Indigenous interpretation may productively contribute to processes of decolonization, reconciliation, and regeneration where Indigenous citizens determine what can and cannot be said, when it can be shared, and by whom, and who controls the narrative. To improve searchability and accessibility, we recommend that these works be centralized, that keyword searches be enhanced, and that interpretation resources are made accessible to researchers or managers searching the topic.

Second, by presenting selected interpretive themes, the scoping review suggests that Indigenous interpretation challenges certain aspects of traditional interpretation strategies in by parks and heritage sites. Although Indigenous interpretation is rarely explicitly defined, several themes are consistently used to illustrate what Indigenous interpretation should entail. More akin to storytelling, Indigenous interpretation is conveyed in the extant literature as fostering connections among people and places, encouraging respectful and meaningful dialogue between local guides and visitors, and fostering a deeper understanding of the sacredness of Indigenous landscapes/seascapes. Fundamental to this approach is that it must be developed under the direction of or (at a minimum in the case of by parks and heritage sites) in collaboration with Indigenous citizens. This form of interpretation is expressed as being deeply rooted in local languages and protocols, which help determine what narratives should be shared (e.g., certain stories or legends) and what should not be shared (e.g., medicines, ceremonies, and sacred areas). These interpretive strategies should be approved and reviewed by the keepers of the culture (such as Elders or hereditary Chiefs) or appointment members of the community.

Finally, our scoping review illuminates recent discussions pertaining to Indigenous interpretation that point toward the idea that a specific definition is still emerging. By identifying and conveying key themes that we see in the literature relating to Indigenous interpretation, our goal has been to illustrate how varied Indigenous interpretation is, and the opportunities and challenges associated to integrating key Indigenous concepts in interpretation. With the additional work and critical reflexivity of future collaborative projects, we hope to illustrate characteristic qualities of Indigenous interpretation and highlight how it could be further developed, defined, and implemented.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

RL: Writing – review & editing. CH: Writing – review & editing. BG: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by a 2018-19 SSHRC Insight Grant (435-2018-0616) entitled “Unsettling Tourism: Settler Stories, Indigenous Lands, and Awakening an Ethics of Reconciliation.”

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abou-Setta, A. M., Jeyaraman, M. M., Attia, A., Hesham G. Al-Inany, A. H., Ferri, M., Ansari, M. T., et al. (2016). Correction: methods for developing evidence reviews in short periods of time: a scoping review. PLoS ONE 12:165903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165903

Beans, J. A., Saunkeah, B., Woodbury, R. B., Ketchum, T. S., Spicer, P. G., and Hiratsuka, V. Y. (2019). Community protections in American Indian and Alaska Native participatory research—a scoping review. Soc. Sci. 8:127. doi: 10.3390/socsci8040127

Bench, R. (2014). Interpreting Native American History and Culture At Museums and Historic Sites. Lanham, ML: Rowman & Littlefield.

Braun, B. (2002). The Intemperate Rainforest: Nature, Culture, and Power on Canada's West Coast. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burnham, P. (2012). Indian Country, God's Country: Native Americans and the National Parks. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse Inc.

Chew Bigby, B., Hatley, E., and Jim, R. (2023). The potential of toxic tours: indigenous perspectives on crises, relationships, justice and resurgence in Oklahoma Indian Country. J. Sustain. Tour. 31, 2645–2666. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2022.2116642

Couts, R. (2021). Authorized Heritage: Place, Memory, and Historic Sites in Prairie Canada. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press.

Cruikshank, J. (2005). Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

Dean, S. N. (2021). National park interpretation and place-based education: an integrative literature review. J. Exp. Educ. 44, 363–377. doi: 10.1177/1053825920979626

Finegan, C. (2019). The interpreter as researcher: ethical heritage interpretation in Indigenous contexts. J. Herit. Tour. 14, 282–294. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2018.1474883

Grimwood, B. S. R. (2021). On not knowing: COVID-19 and decolonizing leisure research. Leisure Sci. 43, 17–23. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2020.1773977

Grimwood, B. S. R., King, L., Holmes, A., and the Lutsel K'e Dene First Nation. (2017). “Decolonizing tourism mobilities? Planning research within a First Nations community in northern Canada,” in Tourism and Leisure Mobilities: Politics, Work, and Play, eds. J. Rickly, K. Hannam, and M. Mostafanezhad (New York, NY: Routledge), 232–247.

Grimwood, B. S. R., Stinson, M. J., and King, L. (2019). A decolonizing settler story. Ann. Tour. Res. 79:102763. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.102763

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Femin. Stud. 14, 575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066

Henderson, P., Lee, J. P., Soto, C., O′Leary, R., Rutan, E., D′Silva, J., et al. (2022). Decolonization of tobacco in Indigenous communities of Turtle Island (North America). Nicotine Tobacco Res. 24, 289–291. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab180

Hinch, T., and Butler, R. (1996). Tourism and Indigenous Peoples. London: International Thomson Business Press.

Howard, J., Smith, B., and Thwaites, R. (2001). Investigating the role of the indigenous tour guide. J. Tour. Stud. 12, 32–39.

Hughes, K., Moscardo, G., and Taff, B. D. (2023). JIR special issue editorial. J. Interpret. Res. 28, 3–6. doi: 10.1177/10925872231163999

Hvenegaard, G. T., Marshall, H., and Lemelin, R. H. (2016). Hot interpretation of controversial topics at Batoche National Historic Site, Saskatchewan, Canada. J. Interpret. Res. 21, 47–64. doi: 10.1177/109258721602100204

Hvenegaard, G. T., Shultis, J., and Butler, J. R. (2009). “The role of interpretation,” in Parks and Protected Areas in Canada: Planning and Management, eds. P. Dearden, R. Rollins, and M. Needham (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 202–234.

Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (2018). National Guidelines: Developing Authentic Indigenous Experiences in Canada (ITAC Guide). Available at: https://indigenoustourism.ca/corporate/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/18-12-NationalGuidelines-Book-EN-DOC-W-FORMS-v11.pdf (accessed January 12, 2023).

Johnston, J. W., and Mason, C. W. (2020). The paths to realizing reconciliation: indigenous consultation in Jasper National Park. Int. Indig. Pol. J. 11, 1–27. doi: 10.18584/iipj.2020.11.4.9348

Johnston, J. W., and Mason, C. W. (2021). Rethinking representation: shifting from a Eurocentric lens to indigenous methods of sharing knowledge in Jasper National Park, Canada. J. Park Recreat. Admin. 39:10251. doi: 10.18666/JPRA-2020-10251

Koster, R., Baccar, K., and Lemelin, R. H. (2012). Working ON, WITH & FOR Aboriginal communities: a critical reflection on CBPR. Can. Geogr. 56, 195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00428.x

Lee, E. (2017). Performing colonisation: the manufacture of Black female bodies in tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 66, 95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2017.06.001

Lemelin, R. H., and Baikie, G. (2012). “Bringing the gaze to the masses, taking the gaze to the people: the socio-cultural dimensions of last chance tourism,” in Last Chance Tourism. Adapting Tourism Opportunities in A Changing World, eds. R. H. Lemelin, J. Dawson, and E. Stewart (New York, NY: Routledge), 168–181.

Lemelin, R. H., Whyte, K. P., Johansen, K., Higgins Desbiolles, F., Wilson, C., and Hemming, S. (2013). Conflicts, battlefields, Indigenous peoples and tourism: addressing dissonant heritage in warfare tourism in Australia and North America in the 21st century. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hospital. Res. 7, 257–271. doi: 10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2012-0038

Lynch, M. F., Duinker, P., Sheehan, L., and Chute, J. (2010). Sustainable Mi'kmaw cultural tourism development in Nova Scotia, Canada: examining cultural tourist and Mi'kmaw perspectives. J. Sustain. Tour. 18, 539–556. doi: 10.1080/09669580903406605

Mason, C. W. (2014). Spirits of the Rockies: Reasserting an Indigenous Presence in Banff National Park. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Middleton, J., Cunsolo, A., Jones-Bitton, A., Wright, C. J., and Harper, S. L. (2020). Indigenous mental health in a changing climate: a systematic scoping review of the global literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 15:e053001. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab68a9

Mosby, I., and Millions, E. (2021). Canada's Residential Schools Were a Horror Founded to Carry Out the Genocide of Indigenous People, They Created Conditions That Killed Thousands of Children. Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/canadas-residential-schools-were-a-horror/ (accessed January 23, 2024).

Moscardo, G. (1998). Interpretation and sustainable tourism: functions, examples and principles. J. Tour. Stud. 9, 2–13. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_114-1

Moscardo, G., and Hughes, K. (2023). Rethinking interpretation to support sustainable tourist experiences in protected natural areas. J. Interpret. Res. 28, 76–94. doi: 10.1177/10925872231158988

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., and Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

National Association for Interpretation (2024). What Is Interpretation? Available online at: https://nai-us.org/#:~:text=is%20a%20purposeful%20approach%20to,with%20the%20world%20around%20us (accessed January 23, 2024).

Newcomb, T. S. (2016). “Original nations of ‘Great Turtle Island' and the genesis of the United States,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Religion and Politics in The U.S., ed. B. A McGraw (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), 5–17.

Nielsen, N., and Wilson, E. (2012). From invisible to Indigenous driven: a critical typology of research in Indigenous tourism. J. Hospital. Tour. Manag. 19, 67–75. doi: 10.1017/jht.2012.6

Peers, L. (2007). Playing Ourselves: Interpreting Native Histories at Historic Reconstructions. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., Kahlil, H., McInerney, P., Baldini Soares, C., and Parker, D. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 13, 141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Peterson, J., Pearce, P. F., Ferguson, L. A., and Langford, C. A. (2017). Understanding scoping reviews: definition, purpose, and process. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Practition. 29, 12–16. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12380

Rieger, K. L., Gazan, S., Bennett, M., Buss, M., Chudyk, A. M., Cook, L., et al. (2020). Elevating the uses of storytelling approaches within Indigenous health research: a critical and participatory scoping review protocol involving Indigenous people and settlers. Systemat. Rev. 9:6. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01503-6

Runnels, C., Abbott, J. A., Laird, S. G., Causin, G. F. G., Williams, P. S., Coble, T., et al. (2018). Giving Voice to Our First Nations: Creating a Framework for Indigenous Interpretation Through Education and Collaboration (Faculty Publications), 14.

Sandlos, J. (2011). Hunters at the Margin: Native People and Wildlife Conservation in the Northwest Territories. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

Schwandt, T. A. (2015). The Sage Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Smaldone, D., and Rossi, A. (2019). Contested terrain attitudes of Lakota people towards interpretation at Wind Cave National Park. J. Interpret. Res. 24, 100–106. doi: 10.1177/109258721902400108

Smith, L.T. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd Edn. London: Zed Books.

Staiff, R., Bushell, R., and Kennedy, P. (2002). Interpretation in National Parks: some critical questions. J. Sustain. Tour. 10, 97–113. doi: 10.1080/09669580208667156

The National Native American Boarding School History (2023). US Indian Boarding School History. Available at: https://boardingschoolhealing.org/education/us-indian-boarding-school-history/#:~:text=There%20were%20more%20than%20350they%20spoke%20their%20native%20languages (accessed January 20, 2024).

Toombs, E., Kowatch, K. R., and Mushquash, C. J. (2016). Resilience in Canadian Indigenous youth: a scoping review. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resil. 4, 4–32.

Torrance, H. (2018). “Evidence, criteria, policy, and politics: the debate about quality and utility in educational and social research,” in The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th Edn, eds. N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.), 766–795.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Available at: http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf (accessed January 20, 2024).

Tuck, E., and Yang, W. K. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization 1, 1–40. doi: 10.25058/20112742.n38.04

Twance, M. (2019). Learning from land and water: exploring mazinaabikiniganan as indigenous epistemology. Environ. Educ. Res. 25, 1319–1333. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2019.1630802

United Nations (2007). United Nation's Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed January 20, 2024).

United Nations (2009). Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Social Policy and Development Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. State of the World's Indigenous Peoples, First Volume. Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/SOWIP/en/SOWIP_web.pdf (accessed January 20, 2024).

Vowel, C. (2016). Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Issues in Canada. Winnipeg, MB: HighWater Press.

Weaver, H. N. (2014). Social Issues in Contemporary Native America: Reflections from Turtle Island. New York, NY: Routledge.

Whitney-Squire, K. (2016). Sustaining local language relationships through Indigenous community-based tourism initiatives. J. Sustain. Tour. 24, 1156–1176. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1091466

Keywords: Indigenous interpretation, parks and protected areas, storytelling, scoping review, North America

Citation: Lemelin RH, Hurst CE and Grimwood BSR (2024) Indigenous interpretation in parks and protected areas on Turtle Island: a scoping review. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1344288. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1344288

Received: 25 November 2023; Accepted: 13 August 2024;

Published: 18 September 2024.

Edited by:

Courtney Mason, Thompson Rivers University, CanadaReviewed by:

Dallen J. Timothy, Arizona State University, United StatesGeorgette Leah Burns, Griffith University, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Lemelin, Hurst and Grimwood. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Raynald Harvey Lemelin, aGFydmV5LmxlbWVsaW5AbGFrZWhlYWR1LmNh

Raynald Harvey Lemelin

Raynald Harvey Lemelin Chris E. Hurst

Chris E. Hurst Bryan S. R. Grimwood

Bryan S. R. Grimwood