- Department of Sociology, Kansai University, Suita, Japan

This study analyzed a social problem-solving workation in Kamaishi, Japan, focusing on the “hitohada nugu” experience, a cross-boundary and other-oriented contribution and relationship-building experience. The results of interviews with stakeholders of the work experience, including company managers and participants, intermediaries in the host local community, and government officials, as well as a questionnaire survey of all participants, indicated that employees who participated in the program learned and grew through their inexperience in Kamaishi, which was different from their work experience. On the other hand, the local community and companies that plan and operate the program face a dilemma in explaining the effects of the workation on the company's business, the solution to local issues, and the learning and growth of employees.

1 Introduction

In Japan, the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 has led to increased attention to workation as tourism declines in the country. At the same time, workations are seen as a form of tourism and an initiative to create a related population in rural areas. The Japan Tourism Agency (JTA) has also described workations as a “new style of travel” and recommends regional development using tourism despite the increasing centralization in Tokyo and the declining birthrate and aging population (Japan Tourism Agency, 2021). One of the critical points mentioned above is the “related population”. The term “related population” does not refer to “permanent residents” who move to a region, nor does it refer to “exchange population” who visit a region as tourists but refers to “people who have diverse relationships with a region” (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, 2018).

As companies recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation rate of remote work by companies declines, workations are expected to create value in companies while creating a related population. The Japan Tourism Agency classifies workations into the following categories: welfare type, regional issue-solving type, camp type, and satellite office type.

For workations to spread, flexible work styles, especially teleworking, are needed. According to a Persol Research and Consulting survey, the telework implementation rate in July 2023 was 22.2%, the lowest since April 2020. However, according to employment type, 22.2% of full-time employees and 13.9% of part-time employees are full-time employees. By company size, 35.4% of respondents were employed by companies with 1,000 or more employees, gradually decreasing to 12.5% for companies with 10–100 employees or less. By region, 33.7% of companies were located in the Tokyo area (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba prefectures), 20.0% in the Osaka area (Osaka, Hyogo, Kyoto, and Nara prefectures), and 16.2% in the Nagoya area (Aichi, Gifu, and Mie prefectures), the next largest economy. These results indicate that most teleworkers are full-time employees of large companies in urban areas, especially in the Tokyo area (Persol Research and Consulting, 2023a). These findings indicate that the acceptance of work in large urban companies is crucial for creating a related population.

This study aims to clarify how the “Hitohada nugu” experience builds participants' attachment to the organization and region and their learning and growth. “Hitohada nugu” is a Japanese expression. “Hitohada nugu” is an expression derived from the action of rolling up the sleeves of a kimono when doing heavy lifting, and refers to enthusiastic help for others or to a friendly agreement to participate in a project. This study shows the benefits and dilemmas of a problem-solving work experience program that contributes to the community from the perspective of the “Hitohada nugu” experience and how it should be designed. Among affiliative nomads in Japan, practitioners of this local problem-solving workation will play a significant role.

2 Literature review

2.1 Digital nomadism

Workcation is more broadly positioned as one of the digital nomad studies. The concept of the digital nomad has been outlined since Makimoto and Manners (1997), and research gradually progressed from the latter half of the 2010s to refer to people working with mobile PCs in a location-independent manner (Müller, 2016; Reichenberger, 2018; Thompson, 2019; Aroles et al., 2020; Cook, 2020; Hannonen, 2020). Digital nomadism studies have been analyzed mainly from the perspectives of digital work, flexibility, mobility, identity, and community (Hensellek and Puchala, 2021).

In the context of tourism, digital nomads can also be viewed as leisure-time activities with relatively long stays (Reichenberger, 2018) or as culture-driven travelers (Bertola et al., 2022) who are attracted to the creative aspects of a city or region. In other words, digital nomads are a lifestyle that is both a work style and a tourism behavior (Cook, 2020; Hannonen, 2020).

Nomad List (2023) shows that 46% of digital nomads stay in one city for seven days or less, 33% for 7–30 days, 14% for 30–90 days, and 6% for 90 days or more, with an average stay of about 2 months (median 7 days). Most men are software and web developers and start-up founders, while most women are marketing and creative professionals. Many digital nomads stay in coliving spaces and work from their places of stay or co-working spaces. The community formed there establishes a creative lifestyle and leads to interaction with the local community (Orel, 2019).

After the expansion of COVID-19 in 2020, there is even more focus on digital nomads as a new work style and tourism target as teleworking becomes more widespread and tourism is reexamined (Thompson, 2019; Almeida and Belezas, 2022; Cook, 2022; Voll et al., 2022; Hannonen et al., 2023).

In addition, digital nomads are not limited to freelancers and entrepreneurs but are also expanding as an employee work style. The U.S. digital nomad population more than doubled from 7.3 million in 2019 to 17.3 million in 2023, accounting for 11% of all workers. This breakdown shows more employee workers (3.2% in 2019 to 10.7% in 2023) than independent workers (4.1% in 2019 to 6.6% in 2023) (MBO Partners, 2023). The Nomad List (2023) survey also shows that full-time workers are the most common type of worker (42%), followed by freelancers (17%) and startup founders (16%). Thus, after 2020, a group that can also be called “Digital Nomadic Employees (DNE)” will be the majority of digital nomads.

2.2 Workation and “Hitohada nugu”

In Japan, practices have been promoted since the late 2010s, focusing on workcations as part of efforts to attract local businesses, promote migration, or reform corporate work styles (Matsushita, 2019; Tanaka and Ishiyama, 2020). Tanaka and Ishiyama (2020) define workcations as “flexible leave systems and ways of working that embed a sense of extraordinary leisure into everyday work, which individuals value and choose to do independently.” They classify the stakeholders into four categories: (1) companies that introduce the system, (2) employees and individuals who use the system, (3) communities and governments that accept the users, and (4) private businesses related to workcation.

In response to the decline in the tourism industry due to the COVID-19 pandemic, workation as a new market for the tourism industry has been linked to hot springs (Mori et al., 2021; Moriya and Ikeji, 2021), business trips (Moriya and Ikeji, 2021), rural tourism (Ohe, 2022), and other possibilities. For individual workers, it is also an approach to improve health and productivity (Iwaasa et al., 2022; Negoro and Kobayashi, 2022). In response to this trend, each region and municipality that has developed workation projects has actively implemented facilities and equipment (Sakamoto, 2022).

On the other hand, workation has also become an approach that aims to enhance employee creativity, learning, and reflection, reflecting the desire of regions to increase the related population and companies with business and training programs (Matsushita, 2021, 2022; Yoshida, 2021).

Matsushita (2022) points out that in the Japanese region, Digital Nomadic Employees confirm their sense of self-efficacy and review their careers through cross-border experiences in multiple jobs. Persol Research and Consulting (2023b) distinguished between individual and group workations and surveyed the effects felt during workation. Compared with tourist groups, 40% of group workation participants mentioned job efficacy as a benefit, whereas 36.3% of individual workation participants and 20.6% of tourist groups did so. Regarding health recovery as a benefit, the highest was 42.9%, lower than the tourist group at 60% and individual workation participants at 50.7%. Regarding the effects after workation, ~50% felt an increase in their happiness at work, and ~40% felt an increase in their work engagement. Thus, group workation affects talent development and organizational development. In other words, workation can be viewed as an organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) performed by Digital Nomadic Employees.

OCB refers to employees' contributions that support a broader social and psychological environment within the organization beyond role requirements and contractually rewarded job outcomes (Youssef and Luthans, 2007; Organ, 1988). While these studies have mainly focused on in-organization behavior, it is conceivable that actions outside the organization or in the community could also become a subject, with the spread of remote work and workation.

Grant (2013) pointed out that among the behavioral principles of Giver, Taker, and Matcher, the highest performance is seen in Givers. However, he also noted that self-sacrificing Givers perform the worst, and the other orientation improves performance. In that sense, an other-oriented Giver can be said to be a “Hitohada nugu” person. This study focuses on the “Hitohada nugu” experience.

In experiential learning and leadership development research, significant professional growth is described in Japanese as “hitokawa mukeru” (Kanai and Furuno, 2001; McCall, 1988; McCall et al., 1988; Kanai, 2002). These experiences were important in growth and leadership development but were limited to work-related experiences. Problem-solving workation can be positioned as an out-of-office, off-the-job experience that can be applied to the company or individual careers. Cross-boundary exchanges facilitate member learning through conflict (Ferguson and Taminiau, 2014) and allow for decontextualization of self-knowledge (Bechky, 2003).

In this study, the experience of cross-boundary engagement in social issues outside the company in this way is positioned as a “hitohada nugu” experience as opposed to a “hitokawa mukeru” experience. For example, the “Ume Harvest Workation” has been taking place in Wakayama Prefecture, Japan. It has been reported that the experience of being involved as a worker rather than a tourist has increased interest in agriculture and attachment to the region. On the other hand, it has not been fully clarified whether companies and communities incorporate such “hitohada nugu” experiences into workation and what challenges they face. This paper focuses on the convivial relationship (Lehto et al., 2020) among stakeholders, including the company and its staff, participating employees, and the host local community and intermediaries. Analyzing this aspect will be necessary for the region to accept and function as affiliative nomads.

3 Method and data collection

3.1 Method

A “natural experiment” (Dunning, 2012) approach was adopted to analyze community impacts in tourism research (Manwa et al., 2017; Dong and Nguyen, 2023) to empirically analyze situations shaped by power relations in which the researcher cannot intervene. There are growing case studies on digital nomads and workations (Almeida and Belezas, 2022; Hannonen et al., 2023). This paper considers workation practitioners as affiliative nomads and chooses to conduct a qualitative study focusing on interviews and observations since their cross-border and other-oriented contributions to foster attachment to the community are also situations in which researchers cannot intervene. Dyer and Wilkins (1991) emphasize the importance of using single case studies to create quality knowledge, even more accurately than multiple case study methodologies. The workation project in Kamaishi, which has a rich historical and regional context, is representative of similar cases and the high interest of the case itself, which is why a single-case study is employed (Stake, 2013; Komppula, 2014).

In addition to collecting secondary data on the workation project in Kamaishi through the Kamaiishi DMC website and various public documents, this paper will collect primary data through interviews with workation participants and organizers, local hosting businesses, and intermediaries, as well as through a questionnaire to participants in consideration of the power structure of the workation project. Data triangulation was conducted by collecting primary data through questionnaires to participants (Denzin, 2009; Stake, 2013; Merriam and Tisdell, 2016).

3.2 Research site: Kamaishi, Japan, and workation

This study uses Kamaishi City in Iwate Prefecture as a case study to demonstrate how workation as a “Hitohada nugu” experience can lead to an attachment to the region.

Kamaishi City is located on the coast of Iwate Prefecture in the Tohoku region of Japan. Known as “the city of iron and fish”, Kamaishi has developed around the steel and fishing industries. Although the city was severely affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, it has been steadily recovering. The population was ~37,000 in 2012 but has decreased to ~30,000 by 2023. With ~40% of the population being over 65 years old, the city faces challenges such as a declining regional industry, deteriorating transportation and various services, and an aging population.

Since 2021, Kamaishi has initiated workation programs targeted at companies in the Tokyo metropolitan area, thereby creating an exchange population. Workation, enabling comparatively longer stays than typical tourism, brings not only economic benefits to the area through local consumption but also fosters a sense of attachment to Kamaishi and creates long-term engagement with the region. For Kamaishi, which lacks prominent tourist resources, corporate workation is anticipated as a content for long-term stays.

At the heart of these workation initiatives is Kamaishi Destination Management Company (DMC), established in 2018. Kamaishi DMC is dedicated to realizing the vision of “Kamaishi Open Field Museum” proposed by the city since 2016. “Kamaishi Open Field Museum” is a tourism concept that views the entire town as a “museum without a roof”, offering experiential programs that introduce the daily life and work of local farmers, fishermen, forestry workers, business owners, and city officials, as well as sharing their stories of recovery from the disaster. Since being selected in 2018 as the first Japanese location for the Green Destinations' “Top 100 Sustainable Destinations,” Kamaishi has been chosen for four consecutive years, leading Japan's efforts in sustainable tourism.

Kamaishi DMC targets “corporations in the Tokyo metropolitan area” and offers programs themed around disaster prevention education and the city's reconstruction process. As part of the vacation element, and due to the lack of facilities such as hot springs, the DMC provides programs that allow participants to experience local industries such as fishing and forestry.

The program content includes learning from the “Kamaishi incident” during the Great East Japan Earthquake, organizational development training (examining how the management of schools ensured 100% survival of children and students during the tsunami), reconstruction and town development training (learning about town development from disaster to recovery), and a microplastics program (observing microplastics from seawater collected during a fishing boat experience, in collaboration with fishermen and Iwate University).

According to an interview with a representative of Kamaishi DMC, the corporate workation intake for fiscal year 2021 included 12 instances, 75 participants, 195 overnight stays, and a total local consumption of approximately 4.4 million yen. For fiscal year 2022, there were 12 instances, 100 participants, 198 overnight stays, and a total local consumption of ~4.2 million yen. The satisfaction level of corporate workation participants exceeded 90%, providing a high value workation experience. Despite the pandemic, these programs have achieved certain results. In implementing corporate workations, the DMC always considers the economic benefits to the region, such as guiding participants to local accommodations and restaurants, and the interest from local stakeholders is increasing.

Kamaishi DMC is now working to transition from workations that approach businesses from the region to those that are mindful of mutual interaction between the region and businesses. The corporate version of workcations that Kamaishi has been offering provides learning opportunities for participants from urban areas to understand Kamaishi, a region characterized by earthquake reconstruction, disaster prevention, and other aspects of community development, and social issues such as mobility, agriculture, forestry and fisheries industry due to the aging population and low birthrate. In addition, as companies are becoming more interested in regional revitalization and business opportunities in rural areas, Kamaishi DMC is working on creating programs that combine visiting companies' solutions with regional characteristics, providing workations that are beneficial for both companies and the region.

3.3 Data collection

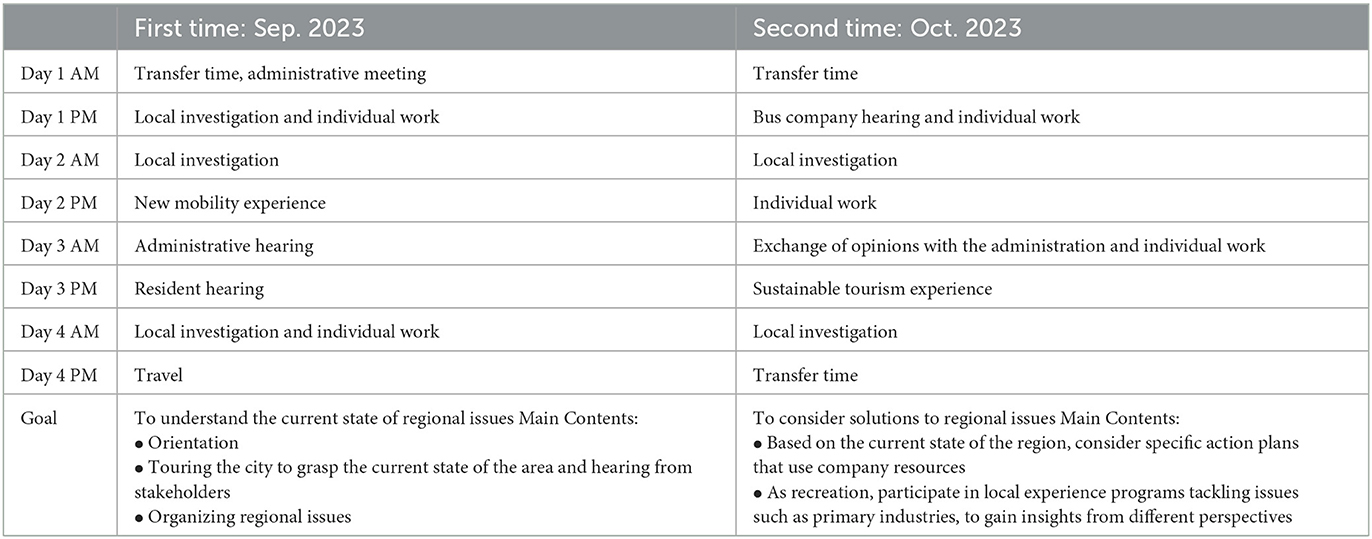

The target of this research is the workation initiative conducted in Kamaishi City by Kamaishi DMC starting from 2023. This workation initiative offers a 4-day workation program to corporations, conducted three times with the following objectives and contents (Table 1).

Human Resource Management (HR) personnel recruited workation participants within the company, and four employees participated in each session. In addition, participants received several pre-visit lectures about Kamaishi from HR and online sessions with local coordinators before visiting the site. Subsequently, in the third session, they are scheduled to propose solutions to the administration or local businesses and action plans.

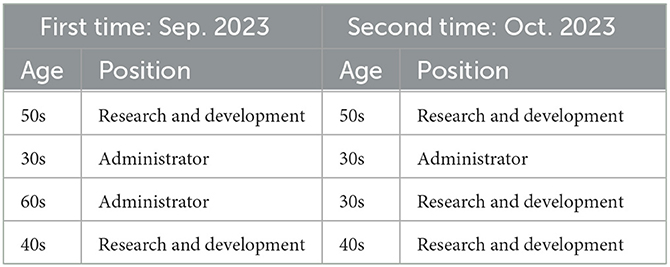

This study focused on the first and second field surveys in which participants conducted field surveys that included interviews with local businesses, local residents, and government officials. The data used in this study was collected from a workation project conducted in September 2023 and October 2023 by Company A, an automobile-related company in the Tokai region. The regional problem addressed in this case study is mobility in rural areas. In rural areas of Japan, aging populations and declining birthrates make it increasingly difficult to maintain public transportation services. This has caused problems for local residents regarding shopping, schooling, medical care, and other aspects of their daily lives. Therefore, new technologies and services such as mobility and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) are expected to be utilized. Although the participants belong to a department that develops small cars and is not directly involved in developing mobility services, the community and companies expect the participants to think about their business at a higher level and contribute to society through the theme. The demographics of each participant are shown in Table 2.

Initially, a questionnaire about (1) workation experience, (2) attachment to the region and their own company, and (3) expectations and anxieties about whether their skills and experiences can adapt to social issues in the region were conducted for a total of eight participants, four from the first and second times, before and after the workation program. The questionnaire used a four-point scale: “strongly agree,” “somewhat agree,” “do not agree much,” and “do not agree at all.” Before implementation, responses were obtained from all eight participants in the first and second sessions. After implementation, responses were obtained from seven participants, four in the first session and three in the second session.

There is also a possibility that the intentions and experiences of the participants and the company's HRM do not align. Therefore, semi-structured interviews of 30 min to an hour were conducted with two HR personnel who planned and accompanied the workation about the company's HR challenges and their intentions for participating in the workation initiative.

In parallel, semi-structured interviews of 30 min to 1 h were conducted until no more new information was available (Coffey and Atkinson, 1996). One could also be that the intentions and experiences of the participants and those of the company's HRM did not match. Therefore, interviews were conducted with the two HR managers who planned and accompanied the project about their company's HR issues and intentions for participating in the workcation project. The second is about the design process of the workation program that is the subject of this study, based on the workation program design process to date with the two project managers and coordinators of the DMC. The third was with two government officials receiving the program about the value and challenges of accepting workation in the community.

4 Results

4.1 Attachment to company and local

Regarding workation experience, seven out of the eight participants had experience with 2–4 workations, while one employee was participating in a workation for the first time. Regarding job satisfaction, two respondents answered, “very satisfied,” five were “somewhat satisfied,” and one was “not very satisfied.” Regarding the need for learning and growth, five indicated “a great need,” and three felt “some needs.” This shows that while job satisfaction is not low, it is not extremely high either; hence, many employees feel a need for learning and growth.

Moreover, the employees did not have a particularly strong attachment to their own company: one responded with “very attached,” six with “somewhat attached,” and one with “not very attached.” On the other hand, due to the lectures they had attended prior to the workation, seven participants (87.5%) expressed a “solid” interest in Kamaishi, and all were “very willing” to solve the region's problems through the workation.

4.2 Learning and growth through the tackling of unfamiliar challenges

When asked about engaging in activities that were new to them for resolving regional issues, 6 (75%) were “very willing” to try, while responses were mixed regarding the desire to utilize their existing job experience, skills, and tasks. Five participants mentioned interacting and collaborating with local people because of the workation program, two cited solving local problems, and one associated it with personal health and refreshment, indicating a greater emphasis on interaction with local people than solving the problems themselves.

This shows that participants are more interested in using workations to engage in new activities through interaction with locals, rather than applying their existing skills and experience to solve social issues. Post-program surveys showed a balanced number of “somewhat agree” and “not very agree” regarding contributions to solving regional issues, indicating a lack of strong feeling that progress was made.

However, when asked if they were able to engage in activities they had not experienced before, five answered “very much so,” and two “somewhat.” Likewise, when asked if the activity led to their learning and growth, five said “very much so,” and two “somewhat,” shows that they were indeed connecting new experiences to their personal development.

4.3 Positioning of workation within the corporation

Interviews with HR personnel revealed a significant issue: there was a sense of distance between the products they developed in the small car division and society.

“We're always in Aichi Prefecture, thinking about various things based on what we can find on the internet, but it doesn't materialize, or we're not sure if that's really the cause. We started as volunteers, but from this fiscal year, we've been given a budget, and it has taken shape as part of our business... (omitted)... As a technical department, we rarely talk to customers or users, so I hope this activity will allow us to hear what they think and what they want from mobility.”

Therefore, during workations, the goal is to combine solving regional issues with their own business rather than improving work productivity or teamwork. By interacting with local residents, businesses, and the administration, employees aim to understand how their business is perceived in society and how it can contribute, regardless of the department to which they belong. This understanding is seen as a key objective, with the hope that it will lead to increased attachment to the company and a desire for learning and growth.

“The department and the projects they are involved in vary, but overall we've been focused on gasoline cars, and as electrification advances, relying solely on that makes it difficult to maintain profits... (omitted)... There's also anxiety that we must adopt new things such as hybrids and electric vehicles, so there's a part of us that participates to challenge ourselves to new things.”

The interviews also highlighted a dilemma concerning the effectiveness of workation programs centered on social problem-solving within the company. To allocate a budget for workation, the company expects returns such as new business development. It is challenging to launch a new business within a few days of conducting workation on mobility in rural areas.

“Whether it has shown its usefulness to the organization is not yet clear. Different departments have different expectations; some want visible results, while others believe that it's educational just to find out if there's something that can be done.”

Thus, some managers seek short-term benefits from workation, whereas others focus on the long-term benefits it may trigger. Some even consider the realization that certain issues cannot be immediately resolved as a benefit. From the HR perspective, employee growth through interactions with locals and crossing borders is of utmost importance, and direct returns such as new business ventures are not the primary focus. However, for HR personnel to deploy it within the company, they face the dilemma of having to explain the aforementioned returns and elements such as creating shared value (CSV) when initiating projects and reporting outcomes.

4.4 Positioning of workation in the local community

The interviews with the hosts in the region indicated a shared sense of working together to address local issues, which cannot be achieved through one-shot visits or tourism.

I am currently the only one in charge of public transportation in the government. The number of buses has decreased, so the administration is providing buses, and there are challenges in public transportation due to a declining birthrate and aging population... I just became in charge in December 2021... Company A, who has specific knowledge about mobility, has been very helpful, and we are working together. (government transportation official).

This is important for administrations in relatively small regions where departments may change over the years, or one person may be in charge of several areas. It also leads to concerns about excessive expectations for the host community, especially for the residents who receive hearings from workation participants.

(In Kamaishi) earthquake reconstruction is a story so far, but mobility is a more immediate and pressing issue. However, as a resident and a local government official, there is a concern that directly interviewing residents may lead to excessive expectations that something will be solved immediately. (government official in charge of the local community).

As indicated in 3-3, the participants belong to the development department of a small car and need to gain specialized knowledge or experience in local mobility. The workation project's purpose is to tackle issues that they are not usually involved in their work, although they share the common theme of mobility. Close communication with local residents through interviews and exchanges is essential for the participants' cross-boundary learning and experience in this problem-solving workation. On the other hand, it is suggested that it is crucial for the host community to explain and control the issues so that short-term, concrete solutions are not overly expected.

5 Discussion and conclusion

The pandemic that started in 2020 led to a decline in tourism, which spurred the expansion of workation. In Japan, where an aging population and various social challenges persist, there is a high expectation for workations focused on generating related populations and solving social issues.

5.1 Theoretical contribution and practical implications

Since 2020, with the broader adoption of telework and the reassessment of tourism practices, there has been increased attention to digital nomads and co-working spaces (Hannonen et al., 2023; Vogl and Micek, 2023). Matsushita (2022) explored the potential of workations as Digital Nomadic Employees, not tourists but as part-time local talents. This study has provided insights into the program design of value-creation workations based on cooperation between regions and companies, rather than individuals. Workation programs that blend solutions from visiting companies with local characteristics can benefit companies and the region, attracting “affiliative nomads” who may contribute to the area but are neither tourists nor residents. The post-program realization of self-learning and growth demonstrated in this study comes not from leveraging one's skills or enduring challenging field experiences but from interactions with locals and engaging in new, unfamiliar activities. These can be described not as “quantum leap experiences” but as commitments to regional issues or “Hitohada nugu' experiences. Thus, this study shows that “Hitohada nugu” experiences in workations can function for personnel development in management, focusing on solving regional issues.

Moreover, this study suggests that for “affiliative nomads” to function effectively, pre-participation content within the participating companies and a link between the region and the outside world, such as Kamaishi DMC, are crucial. Firstly, by providing prior information about Kamaishi and interactions with Kamaishi DMC as a receiver, participants' interest in Kamaishi and motivation to solve regional issues can be increased. Secondly, as a DMC, connecting deeply into the region through business layers and managing the influx to some extent as a response to over-tourism can contribute to the proper scaling and area allocation of “affiliative nomads” and the cultivation of regional branding.

Thus, this study has shown that “Hitohada nugu” experiences are a critical concept that can attract and function for “affiliative nomads”. In this sense, this study contributes to advanced concepts such as New Locals (Hannonen et al., 2023) and Half Tourist (Almeida and Belezas, 2022), which analyze the impact on tourism and local economies of digital nomads who stay for relatively long periods, to local social design. The project has contributed to advancing these concepts to the social design of the local community.

5.2 Limitations and future study directions

Finally, two limitations of this study should be noted. The first is the effectiveness of workation programs for international digital nomads. This research focused on companies and employees already associated with Tohoku and Kamaishi. However, it needs to sufficiently demonstrate the effectiveness of workation programs for digital nomads from overseas with no previous connection to Japan or Kamaishi. As the number of digital nomads and visits to Japan increases, how they can function as “affiliative nomads” in the region is an important discussion point. Therefore, future research will investigate the global mobility research discourse and how such mobility is accepted locally, targeting digital nomads coming to Japan.

Second, this study could not thoroughly examine how “Hitohada nugu” experiences impact regional social issues and company personnel development. While the study showed that challenging oneself with new experiences and interactions with local residents is effective for individual learning and growth, the impact of “Hitohada nugu” experiences on regional social issues, the influence on other employees within the company, and the impact on HR strategies, including recruitment, should be examined in more detail. For this, a more thorough analysis of “Hitohada nugu” experiences is required.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the (patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin) was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

KM: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This is a product of research that the Kansai University Fund financially supported for Supporting Young Scholars, 2023 “Research on Team Unity and Attachment in Hybrid Work,” and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP 23K11662.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Almeida, J., and Belezas, F. (2022). “The rise of half-tourists and their impact on the tourism strategies of peripheral territories,” in Tourism Entrepreneurship in Portugal and Spain. Tourism, Hospitality and Event Management, eds J. Leitão, V. Ratten, and V. Braga (Cham: Springer).

Aroles, J., Granter, E., and de Vaujany, F.-X. (2020). ‘Becoming mainstream': the professionalisation and corporatisation of digital nomadism. New Technol. Work Empl. 35, 114–129. doi: 10.1111/ntwe.12158

Bechky, B. A. (2003). Sharing meaning across occupational communities: the transformation of understanding on a production floor. Organ. Sci. 14, 312–330. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.3.312.15162

Bertola, P., Iannilli, V., Spagnoli, A., and Vandi, A. (2022). “Cultural and creative industries as activators and attractors for contemporary culture-driven nomadism,” in Cultural Leadership in Transition Tourism: Developing Innovative and Sustainable Models (New York, NY: Springer International Publishing), 51–74. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-14121-8_4

Coffey, A., and Atkinson, P. (1996). Making Sense of Qualitative Data. Complementary Research Strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cook, D. (2020). The freedom trap: digital nomads and the use of disciplining practices to manage work/leisure boundaries. Inf. Technol. Tour. 22, 355–390. doi: 10.1007/s40558-020-00172-4

Cook, D. (2022). Breaking the contract: digital nomads and the state. Crit. Anthropol. 42, 304–323. doi: 10.1177/0308275X221120172

Denzin, N. K. (2009). The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 1st Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315134543

Dong, X. D., and Nguyen, T. Q. T. (2023). Power, community involvement, and sustainability of tourism destinations. Tour. Stud. 23, 62–79. doi: 10.1177/14687976221144335

Dunning, T. (2012). Natural Experiments in the Social Sciences: A Design-Based Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dyer, W. G., and Wilkins, A. L. (1991). Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: a rejoinder to eisenhardt. Acad. Manage. Rev. 16, 613–619. doi: 10.2307/258920

Ferguson, J., and Taminiau, Y. (2014). Conflict and learning ininter-organizational online communities: Negotiating knowledge claims. J. Knowl. Manage. 18, 886–904.

Grant, A. M. (2013). Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success; [Why Helping Others Drives Our Success]. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Hannonen, O. (2020). In search of a digital nomad: defining the phenomenon. Inf. Technol. Tour. 22, 335–353. doi: 10.1007/s40558-020-00177-z

Hannonen, O., Quintana, T. A., and Lehto, X. Y. (2023). A supplier side view of digital nomadism: the case of destination Gran Canaria. Tour. Manag. 97:104744. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104744

Hensellek, S., and Puchala, N. (2021). “The emergence of the digital nomad: a review and analysis of the opportunities and risks of digital nomadism,” in The Flexible Workplace: Coworking and Other Modern Workplace Transformations (New York, NY: Springer), 195–214. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-62167-4_11

Iwaasa, T., Ebata, T., Mizuno, M., and Yoshikawa, T. (2022). Effects of sports workcation on workers' health and psychosocial outcomes. Jpn. J. Ergon. 58, 174–185. doi: 10.5100/jje.58.174

Japan Tourism Agency (2021). Workation and Bleisure as New Travel Style. Available online at: https://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/workation-bleisure/

Kanai, T., and Furuno, Y. (2001). “Quantum leap experience” and leadership development: cultivating the middle as a source of intellectual competitiveness. Hitotsubashi Bus. Rev. 49, 48–67.

Komppula, R. (2014). The role of individual entrepreneurs in the development of competitiveness for a rural tourism destination–A case study. Tour. Manag. 40, 361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.007

Lehto, X., Davari, D., and Park, S. (2020). Transforming the guest–host relationship: a convivial tourism approach. Int. J. Tour. Cities 6, 1069–1088. doi: 10.1108/IJTC-06-2020-0121

Makimoto, T., and Manners, D. (1997). Digital Nomad. New York, NY: Wiley. Available online at: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/wiley022/97020247.html

Manwa, H., Saarinen, J., Atlhopheng, J. R., and Hambira, W. L. (2017). Sustainability management and tourism impacts on communities: residents' attitudes in Maun and Tshabong, Botswana. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 6, 1–15.

Matsushita, K. (2021). “Workations and their impact on the local area in Japan,” in The Flexible Workplace, eds. M. Orel, O. Dvouleý, and V. Ratten (New York, NY: Springer), 215–229. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-62167-4_12

Matsushita, K. (2022). How the Japanese workcation embraces digital nomadic work style employees. World Leis. J. 65, 218–235. doi: 10.1080/16078055.2022.2156594

MBO Partners (2023). Digital Nomads. Available online at: https://info.mbopartners.com/rs/mbo/images/2022_Digital_Nomads_Report.pdf (accessed January 5, 2024).

McCall, M. W. (1988). Developing executives through work experiences. Hum. Resour. Plann. 11, 39–49.

McCall, M. W., Lombardo, M. M., and Morrison, A. M. (1988). The Lessons of Experience: How Successful Executives Develop on the Job. San Francisco, CA: New Lexington Press.

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ministry of Land Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. (2018). The Portal Site of Related Populations. Available online at: https://www.soumu.go.jp/kankeijinkou/ (accessed January 5, 2024).

Mori, Y., Saito, M., and Hayasaka, S. (2021). Staying in hot spring areas for business purposes before COVID-19 pandemic and the application to “workation”: based on the results of the national survey project to measure the effects of an “ONSEN stay.” Jpn. J. Health Res. 42, 49–56. doi: 10.32279/jjhr.202142G05

Moriya, K., and Ikeji, T. (2021). A study on characteristics of Japanese bleisure travelers and initiat- ives in destinations. Tour. Stud. 33, 37–45. doi: 10.18979/jitr.33.3_37

Müller, A. (2016). The digital nomad: Buzzword or research category? Transnat. Soc. Rev. 6, 344–348. doi: 10.1080/21931674.2016.1229930

Negoro, H., and Kobayashi, R. (2022). A workcation improves cardiac parasympathetic function during sleep to decrease arterial stiffness in workers. Healthcare 10, 1–11. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10102037

Nomad List (2023). The 2024 State of Digital Nomads. Available online at: https://nomadlist.com/digital-nomad-statistics (accessed January 5, 2024).

Ohe, Y. (2022). Exploring new directions of rural tourism under the new normal: micro tourism and workcation. Jpn. J. Tour. Stud. 20, 1–9. doi: 10.50839/sogokanko.20.0_1

Orel, M. (2019). Coworking environments and digital nomadism: balancing work and leisure whilst on the move. World Leis. J. 61, 215–227. doi: 10.1080/16078055.2019.1639275

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com.

Persol Research and Consulting (2023a). Seventh Survey on the Impact of the New Coronavirus Countermeasures on Telework. Available online at: https://rc.persol-group.co.jp/thinktank/data/telework-survey7.html (accessed January 5, 2024).

Persol Research and Consulting (2023b). Quantitative Survey on Workation. Available online at: https://rc.persol-group.co.jp/thinktank/data/workcation.html (accessed January 5, 2024).

Reichenberger, I. (2018). Digital nomads –a quest for holistic freedom in work and leisure. Ann. Leis. Res. 21, 364–380. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2017.1358098

Sakamoto, J. (2022). Progress of telework and workcation efforts by local municipalities under COVID-19 pandemic. J. City Plann. Inst. Jpn. 57, 1401–1408. doi: 10.11361/journalcpij.57.1401

Tanaka, A., and Ishiyama, N. (2020). Effectiveness and challenges of japanese workation: definition, classification, and impact on stakeholders. J. Jpn. Found. Int. Tour. 27, 113–122. doi: 10.24526/jafit.27.0_113

Thompson, B. Y. (2019). The digital nomad lifestyle: (remote) work/leisure balance, privilege, and constructed community. Int. J. Sociol. Leis. 2, 27–42. doi: 10.1007/s41978-018-00030-y

Vogl, T., and Micek, G. (2023). Work-leisure concepts and tourism: studying the relationship between hybrid coworking spaces and the accommodation industry in peripheral areas of Germany. World Leis. J. 65, 276–298. doi: 10.1080/16078055.2023.2208081

Voll, K., Gauger, F., and Pfnür, A. (2022). Work from anywhere: traditional workation, coworkation and workation retreats: a conceptual review. World Leis. J. 65, 150–174. doi: 10.1080/16078055.2022.2134199

Yoshida, T. (2021). How has workcation evolved in Japan?. Ann. Bus. Administr. Sci. 20, 19–32. doi: 10.7880/abas.0210112a

Keywords: digital nomad, workation, related population, Japan, tourism

Citation: Matsushita K (2024) Social problem-solving workation through collaboration between local regions and urban companies: the case of Kamaishi in Japan. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1337097. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1337097

Received: 12 November 2023; Accepted: 09 February 2024;

Published: 01 March 2024.

Edited by:

Shiro Horiuchi, Hannan University, JapanReviewed by:

Ugljesa Stankov, University of Novi Sad, SerbiaGareth Butler, Flinders University, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Matsushita. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Keita Matsushita, a2VpdGEtbUBrYW5zYWktdS5hYy5qcA==

Keita Matsushita

Keita Matsushita