- 1Sociology of Development and Change, Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen, Netherlands

- 2Department of Anthropology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, United States

Emergent discussions on governmentality in surf tourism scholarship apply a traditional Foucauldian perspective to analyze governance models in surf tourism destinations. Understanding governmentality as an “art of governance” creating and influencing human behavior, a handful of scholarly discussions have thus far engaged with Foucault's fourfold categories of neoliberal, sovereign, disciplinary, and (to a much lesser extent) truth governmentalities to interpret surf tourism governance in select locations. Importantly, this nascent thread of surf tourism research has yet to contend with Fletcher's novel framing of multiple governmentalities, which builds on Foucault's original categories and offers communal governmentality as a fifth category. Applying an anti-essentialist approach to the analysis of existing surf tourism governmentality literature, we identify diversity in surfscape governance approaches as an avenue for visibilizing communally self-determined futures in surfing destinations. We map multiple governmentalities as discussed in the literature across the five categories of “art of governance” philosophies and their associated governance principles, policies and subjectivities. The theoretical and empirical implications of a multiple governmentalities approach to surf tourism research can support and strengthen emancipatory community-based surfscape governance models challenging neoliberalism beyond otherwise essentializing frames.

Introduction

As tourism-dependent coastal economies recover from COVID-19-inflicted “undertourism” insecurities, debates surrounding surf tourism governance have become increasingly relevant for scholars, practitioners and communities grappling with the return of “overtourism” and rising overdevelopment in Global South surf destinations (Mihalic, 2020; Fletcher et al., 2020; Blázquez-Salom et al., 2023; Amrhein, 2023). Functioning across local, national and international scales, distinct governance models and approaches affect the political ecologies of surfscapes both materially and discursively in myriad ways (Fletcher, 2019; Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2019). These governance models range from local surf associations and surf tourism management frameworks regulating commons access and behavior, to surf protected areas and government-sponsored “surf cities” leveraging tourism for development. This multi-faceted surf tourism governance milieu has spurred incipient scholarly engagement with Foucault's (2008) “governmentality” analytic to better understand, critique and debate these and other approaches in surf tourism discourse and practice (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017, 2020; Mach and Ponting, 2018). These discussions follow in the wake of earlier research on governmentality in tourism studies more broadly, including Cheong and Miller (2000), Hollinshead (1999, 2003), Tribe (2007), Burtner and Castañeda (2010), and Guerrón Montero (2014).

However limited to date, emergent discussions on governmentality in surf tourism scholarship apply a traditional Foucauldian perspective to analyze governance models in surf tourism destinations. Understanding governmentality as an “art of governance” creating and influencing human behavior, a handful of scholarly discussions have thus far engaged with Foucault's fourfold categories of neoliberal, sovereign, disciplinary, and (to a much lesser extent) truth governmentalities to interpret surf tourism governance in select locations (Foucault, 2008; Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017, 2020, 2022; Mach and Ponting, 2018; Brosius and Ruttenberg, 2025). Importantly, this nascent thread of surf tourism governance research has yet to formally contend with Fletcher's (2019) novel framing of multiple governmentalities, which builds on Foucault's (2008) original categories and offers communal governmentality as a fifth category. The multiple governmentalities framework provides a means of grappling with the overlapping nature of Foucault's (2008) governmentality categories and the complexities produced therein. The theoretical and empirical utility of Fletcher's (2019) framework has been demonstrated in other contexts related to ecotourism, climate change adaptation, forest conservation, development, resource governance, and environmental governance more broadly (see Collins, 2019; Montes, 2019; Youdelis, 2019; Chambers et al., 2019; Hommes et al., 2019; Cullen, 2019). Applied to critical surf tourism studies, Fletcher's (2019) framework offers a relevant conceptual lens for analyzing heterogeneity in surf tourism governance and opening space for recognizing existing principles, policies and forms of subjectivity related to communal governmentality with the liberatory potential to contest problematic neoliberal surf tourism models “dominated and homogenized by and for foreign surfers” common to overtourism experiences in surfing destinations (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017, p. 111). Neoliberal surf tourism models have been identified as problematically adhering to a surf tourism-for-economic growth paradigm (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017, 2020), including the “roving banditry” of surfers and surf tourism operators (Mach and Ponting, 2018, p. 11), as well as destinations “centered around the surf tourism industry” (Hough-Snee and Eastman, 2017, p. 99). The multiple governmentalities approach is useful for identifying diverse applications of surf tourism governance practices beyond existing frames that otherwise variegate, conflate, or flatten them into seemingly stuck or monolithic governmentality categories.

Applying an anti-essentialist approach to the analysis of surf tourism governmentality, we review existing theoretical and empirical studies on governmentality and surf tourism governance, including Mach and Ponting (2018), Hough-Snee and Eastman (2017), and our own previous empirical research on the surfscape commons (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2019, 2022; Brosius and Ruttenberg, 2025). Analyzing governmentality philosophies and surf tourism governance practices by “reading for difference” (Gibson-Graham, 2006, p. 54) the surf tourism governmentality literature as an anti-essentialist method of discourse analysis allows us to identify diversity in surfscape governance approaches. This, in turn, provides an avenue for visibilizing and strengthening communally self-determined futures in surfing destinations by highlighting expressions of communal governmentality and supportive governance practices across Fletcher's (2019) typology. We map multiple governmentalities as discussed in the literature across the fivefold categories of “art of governance” philosophies and their associated governance principles, policies and subjectivities, while honoring the complexities of Foucault (2008, p. 313) original assertion that governmentalities “overlap, lean on each other, challenge each other, and struggle with each other” (as cited in Fletcher, 2019, p. 9).

This approach unsettles monolithic understandings of neoliberal governmentality by attending to the diversity of coexisting surf tourism governance practices as counterhegemonic praxis “expand[ing] the political options to imagine and enact other possible worlds in the here and now” (Gibson-Graham et al., 2016, p. 19). Importantly, this framework allows for seeing specific applications of market-based governance practices as more broadly supportive of communal governmentality in certain instances, as well as communal governance practices promoting, leveraging, challenging and resisting neoliberal governmentality, perpetuating hegemonic interests in some instances and/or promoting endogenous alternatives in others. If critical surf tourism scholars share a horizon for championing communally self-determined governance approaches to contest the “surf tourism industrial complex” in Global South surf destinations (see Gilio-Whitaker, 2017; Hough-Snee and Eastman, 2017), the implications of a multiple governmentalities approach to surf tourism research can support and strengthen emancipatory community-based surfscape governance models challenging neoliberalism beyond otherwise essentializing frames. Insights from this analysis can contribute more broadly to critical surf tourism studies and regenerative or alternative surf tourism governance models in our post-pandemic world.

Governmentality and surf tourism governance

Current discussions on governmentality in surf tourism scholarship apply a traditional Foucauldian perspective to analyze governance approaches in surf tourism destinations. This literature understands governmentality as the discourse, mechanisms and relationships of power determining “the conduct of conduct” or “art of governance” creating and influencing human behavior through the complex interplay among the governing and the governed in surf tourism and culture (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017; Mach and Ponting, 2018; Foucault, 2008; Fletcher, 2010). Current scholarship has engaged with neoliberal, sovereign, disciplinary, and (to a lesser extent) truth governmentalities to interpret and analyze surf tourism governance regimes in different locations (Foucault, 2008; Fletcher, 2010; Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017, 2020; Mach and Ponting, 2018). Specifically, Mach and Ponting (2018) address governmentality categories as related to behavior and regulation at the site of the surf break, as well as the management, exploitation and preservation of surf tourism resources among destination communities, tourists, surf tourism industry operators, governments and international organizations, interpellated across local, regional, state and global scales. This effort to categorize surf tourism governmentality was forwarded partially in response to our earlier critical analysis of the surf tourism-for-sustainable development paradigm, which we discussed as problematically rooted in a pervasive neoliberal governmentality, and where we proposed a community economies approach to development alternatives in surf tourism governance (Gibson-Graham et al., 2013; Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017).

Useful for our purposes, the existing literature describes sovereign governmentality as an art of governance founded on the use or threat of punishment or security measures that function to deter individuals from engaging in certain behaviors or entering certain areas out of fear of punishment (Foucault, 1977; Mach and Ponting, 2018). Mach and Ponting (2018) identify: (a) government restrictions on coastal access; and (b) surf localism, as expressions of sovereign governmentality in the surf tourism context. First, they offer the examples of government-supported surf break privatization by resorts in Fiji and the Maldives as a sovereign governance mechanism implemented to combat overcrowding and the “roving banditry” of surf boat charters (Ponting and O'Brien, 2014; Buckley et al., 2017; Mach and Ponting, 2018, p. 11). Secondly, localism in surfing regularly refers to acts of aggression, assertions of dominance, exclusivity, belonging and regulation of the surf break by surfers who consider themselves “local” to a particular surfing location (Evers, 2004, 2008; Nazer, 2004; Mixon, 2014, 2018; Usher and Kerstetter, 2014, 2015). Localism is discussed in surf studies literature, beyond the lens of governmentality, to include violent and/or verbal intimidation tactics and retribution by locals against non-locals in the water and on land, “locals only” signage at certain surf spots, local surfers taking priority on the waves of their choice, and defining wave access and use conditions in both overt and subtle ways (Scott, 2003; Evers, 2004, 2008; Nazer, 2004; Waitt, 2008; Kaffine, 2009; Anderson, 2014; Mixon, 2014, 2018; Usher and Kerstetter, 2014, 2015; Carroll, 2015; Usher and Gomez, 2016; Mixon and Caudill, 2018). Critical surf scholars expand our understanding of localism as “a ubiquitous phenomenon mired in relations of power in which experiences of place and belonging are negotiated through surfers' differentiated positioning relative to the cultural imaginaries and geographical territories we describe as ‘surfscapes”' (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022, p. 66; Comer, 2010; Anderson, 2014; Olive, 2015). This critical reframing identifies localisms of resistance as distinct from localisms of entitlement relative to the hegemonic “state of modern surfing,” as well as expressions of “girl localism” challenging heteropatriarchal norms in global surf culture (Walker, 2011; Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022; Comer, 2010; Olive, 2019; Wheaton and Olive, 2023). Hough-Snee and Eastman (2017, p. 86–87) define “modern surfing” as “the practice of riding waves on any form of surfcraft after Western appropriation [from native Hawai'ian culture] and exploitation of surfing.” Contrasting modern, Westernized surfing culture with pre-colonial and contemporary Hawai'ian surf histories, surf studies scholarship discusses the transition from traditional to modern surfing, and Hawai'ian resistance therein, as a contested cultural imaginary reproduced through capitalist modes of commodification and culturally appropriated processes of surf tourism promotion (Laderman, 2014; Lemarié, 2016; Walker, 2011; Hough-Snee and Eastman, 2017; Gilio-Whitaker, 2017; Moser, 2020).

Next, disciplinary governmentality is described as being founded on individuals' indoctrination into social ideals, knowledge, and cultural norms that prompt them toward certain behaviors and away from others through conditioned self-selection incentivized through fear of punishment and/or exclusion (Foucault, 1977; Fletcher, 2010; Mach and Ponting, 2018). Adherence to surf etiquette or “the surfer's code” as a set of informally established “rules” determining wave priority and allocation is offered as an example of disciplinary governmentality maintaining social order and conditioning behavioral conformity in the surf tourism context (Mach and Ponting, 2018; Daskalos, 2007; Nazer, 2004; Young, 2000; Towner and Lemarié, 2020). Towner and Lemarié (2020, p. 4) apply a Durkheimian perspective on social bonding and solidarity to highlight “the cooperative norms” of surfing etiquette and associated hierarchies among locals and tourists as a framework for understanding localism as a response to perceived aberrations from respecting the surfer's code. Critical discussions acknowledge disciplinary governmentality as the normalization of surfing subjects' subtle indoctrination into the meritocracy of hyper-masculinized and colonial-patriarchal norms informing the “rules” of modern surf etiquette as a “natural state of affairs” that “prioritize[s] certain surfers and ways of surfing above others” while obscuring its own mechanisms of disciplinary power through the everyday experiences and relationships forged among other surfers in the water (Mach and Ponting, 2018, p. 5; Evers, 2004; Olive et al., 2015; Wheaton, 2017; Comer, 2010). Power, through disciplinary governmentality, then, is founded on conformity to the hegemonic ideals of modern surf culture—itself rooted in gendered and racialized histories—through individuals' self-discipline to the established social order, such that “individuals enthusiastically discipline themselves” (Hargreaves, 1987, p. 141) and surfscape norms are seen as an organic progression or cooperative social construct, not a power-based allocation scheme (Towner and Lemarié, 2020; Mach and Ponting, 2018).

Finally, neoliberal governmentality is treated in the context of surf tourism as an art of governance employing external incentives through “market principles to govern human action in a multitude of expanding realms including social relations and natural resource use (Fletcher, 2010; Foucault, 2008)” (Mach and Ponting, 2018, p. 6). Rooted in the principles of marketization, liberalization, privatization and deregulation, power in neoliberal governmentality is understood as being dispersed through processes of subjectivity that nurture free, self-sufficient individuals, interweaving “aspirations of individuals with market demands” (Hofmann, 2013, as cited in Mach and Ponting, 2018, p. 6; Fletcher, 2010). Facilitating the permeation of market logic into the realms of surf break governance, resource use, surf behavior and surfer subjectivity, expressions of neoliberal governmentality in surf tourism are identified by Mach and Ponting (2018) to include: the marketization of surf breaks through surf tourism operations like surf lessons, coaches and guides, boat charters, beach access and entry fees, “surfonomics” research valorizing the financial importance of certain surf breaks as a strategy to influence government policies toward wave resource preservation, surf-related philanthropic efforts, surf voluntourism, and conservation initiatives stewarded by international surf organizations in affiliation with local surf communities purchasing land to stave off industrial development and the destruction of surf resources, as well as surfers monetizing localism through the paid practice of “blocking” for surf tourists to catch waves they otherwise would be denied (Ernst, 2014).

Critical surf tourism literature has also engaged with the discourse of neoliberalism as foundational to the state of modern surfing beyond explicit discussions of governmentality, however similarly relevant for identifying neoliberal governance practices. In this literature, neoliberalism is specifically defined as a capitalist political-economic governance structure and associated ideology founded on economic liberalization, privatization of land, public enterprise and/or commonly shared resources, and deregulation of investment, finance and ownership (Castree, 2010; Ruttenberg, 2022). Importantly, this literature also distinguishes between (rather than conflates) neoliberal governance and neoliberal governmentality, as follows:

neoliberal governance as the “organization and regulation of human behavior in the interest of exercising power and accumulating capital” (Fletcher, 2013, p. 33), and neoliberal governmentality, which Foucault (2008) describes as an “art of governance” approach to influencing human behavior whereby power seeks to create and manipulate by producing and regulating the realities in which people live and relate (Fletcher, 2013; Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2020, 2017).

This distinction is valuable for identifying specific neoliberal governance practices without assuming that these practices are always more broadly indicative of an overarching neoliberal governmentality. Recognizing neoliberal governmentality as a hegemonic discourse determining ideology, associated structures and socialized patterns of behavior aligned with the tenets of neoliberalism, surf tourism researchers contend that the normalization of neoliberal governmentality in surfing destinations contributes to its invisibility and narrative of inevitability as “just the way things are,” despite the many socioecological challenges attributed to neoliberal surf tourism governance (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017, 2020; Ruttenberg, 2022). Moreover, critical surf scholars have linked neoliberal governance to the surf-tourism-industrial complex endemic to the colonial-patriarchal, capitalist “state of modern surfing” (Hough-Snee and Eastman, 2017; Gilio-Whitaker, 2017). They identify the gendered and racialized aspects of dominant surf culture constructs entrenched through the global capitalist surf industry, and qualify the “state of modern surfing” as “‘a semi-autonomous modern world of its own' under which the right to surf… is governed by pressures exerted by those seeking to institutionalize and profit from modern surfing…., defining what surfing is, what surfing ‘should' look like, and who can surf in different contexts” (Hough-Snee and Eastman, 2017, p. 86–87). While the concept of the “state of modern surfing” has been critiqued for its theoretical conflation with the term “global surf industry” (Lemarie, 2019, p. 215), it still provides conceptual relevance for contemplating neoliberal governmentality dynamics in global surf tourism contexts.

We have argued elsewhere that neoliberal governmentality can be challenged through strengthening and supporting diverse economic, community-based alternatives to development in surf tourism (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017; Ruttenberg, 2022). Others claim, however, that even communally managed surf tourism models “coopt neoliberal governmentality” rather than challenging it fundamentally, while also calling on critical scholars to move beyond monolithic notions of governmentality in our analyses of surf tourism destination governance (Mach and Ponting, 2018). Finally, the decolonizing approach to surf tourism governance calls for a shift from neoliberal governmentality in Global South surf destinations toward self-determined community-based alternatives to development that recognize economic diversity beyond capitalocentric frames common to neoliberal growth-for-development surf tourism models (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2017). This approach to economic diversity beyond neoliberal frames connects critical surf tourism research to tourism scholarship more broadly, particularly related to governmentality in tourism studies (Cheong and Miller, 2000; Hollinshead, 1999, 2003; Tribe, 2007; Burtner and Castañeda, 2010; Guerrón Montero, 2014); diverse economies in tourism research (see Mosedale, 2017; Cave and Dredge, 2020, 2018); and calls for decolonial and diverse economic approaches to regenerative tourism (Cave and Dredge, 2020; Bellato et al., 2023; Bellato and Pollock, 2023; Bellato et al., 2024).

Co-author Ruttenberg's (2022) recent empirical research engaged more rigorously with Gibson-Graham's influential diverse economies framework to highlight the potential for economic diversity (mapped across the categories of labor, enterprise, transactions, property and finance; and divided into capitalist, alternative capitalist, and non-capitalist practices) to de-center the hegemony of neoliberal governance and tourism dependence in Global South surf communities. Finally, we engaged elsewhere with the diverse economies approach to “commoning” as a process of reclaiming enclosed or occupied space, both material and imaginary, and thereby functioning within both physical surfscape territories and discursive cultural imaginaries (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2019). This discussion highlights surfscape “commoning” as a process of mitigating against capitalism, neoliberalism, and coloniality-patriarchy by renegotiating and “establishing rules or protocols for access and use, taking care of and accepting responsibility for a resource, and distributing the benefits in ways that take into account the wellbeing of others” (Gibson-Graham et al., 2016, p. 195) and integrating “economic production, social cooperation, [and] personal participation” into “working, evolving models of self-provisioning and stewardship” of “things that no one owns and are shared by everyone” (Bollier, 2014, p. 2–5). Surfscape commoning thus emphasizes how “Global South locals opening up access to privatized surf breaks, regulating surfscapes through enacting modes of hierarchy or local rules, women surfers blocking for each other to help one another catch more waves, as well as certain community-based surf tourism area management projects like those in Papua New Guinea (O'Brien and Ponting, 2013) and Oaxaca, Mexico (Hough-Snee and Eastman, 2017)” challenge neoliberal surfscape governmentality in communally self-determined ways (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022).

As this literature review demonstrates, emerging discussions on governmentality in surf tourism governance, however limited to date, offer up interesting tensions and critical confusions when describing, defining and categorizing certain surfscape governance approaches, warranting deeper attention and nuance toward a shared language of analysis. Importantly, this nascent body of research on governmentality in surf tourism governance has yet to contend with Fletcher's (2019) novel framing of multiple governmentalities in environmental governance as a means of grappling with the overlapping nature of Foucault's (2008) fourfold categories and the complexities produced therein, as well as the introduction of a fifth category: communal governmentality. Adapted to the diverse ecologies frame, Fletcher (2019, p. 9) defines communal environmentality as building on Foucault's (2008) groundwork for an “alternative art of government, which he called ‘a strictly, intrinsically, and autonomously socialist governmentality'…. emphasizing democratic self-governance and egalitarian distribution of resources” through bottom-up approaches to self-governance. This more nuanced framing, and the addition of communal governmentality/environmentality, offers a relevant lens for analyzing diversity in surf tourism governance and opening space for recognizing existing principles, policies and forms of subjectivity that would fall within the category of communal governmentality with the potential to contest neoliberal surf tourism models, rectify confusion in existing surf tourism governance literature, and support further research into community-based alternatives to neoliberal governance in surf destinations.

Highlighting the utility of this lens, important tensions in the literature on governmentality in surf tourism center around the governance framework of Barra de la Cruz in Oaxaca, Mexico. Barra de la Cruz is an autonomous indigenous community where local residents have developed a surf tourism governance framework prohibiting foreign ownership of land or enterprise, and organized community-run cooperative businesses to generate and distribute surf tourism revenue for local benefit. While Hough-Snee and Eastman (2017, p. 99) refer to Barra as a “neoliberal town centered around the surf tourism industry,” Mach and Ponting (2017, p. 10) describe their community-organized governance practices as “an appropriation of neoliberal governmentality to control surf-break access” and support local community initiatives. Our analysis, however, contends that, under the auspices of the autonomous local assembly, commons governance in Barra de la Cruz actually prevents much of the neoliberal encroachment seen in other Global South surf destinations (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022). Our research describes how many neoliberal practices are resisted through modes of “commoning the surfscape” including localism, cooperative local enterprise, and terms of access, care and responsibility… decided communally (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022). While certain market mechanisms are employed to generate revenue from surf tourists as part of the community's local governance model, our research suggests that the Barra example is indicative of a broader communal governmentality aligned with Fletcher's (2019) multiple governmentalities framework discussed in greater detail below. We return to the Barra de la Cruz example in our analysis as a meaningful case study that highlights the diverse ecologies approach to multiple governmentalities discussed below.

Multiple environmentalities: toward mapping complexity in surf tourism governance

Building on Gibson-Graham's diverse economies perspective as described above, the conceptual frame for our analysis centers Fletcher's (2019) “diverse ecologies” framework to map multiple governmentalities in Global South surf tourism governance. This framework establishes important links between political ecology and diverse economies approaches to contend with both structural and discursive power dynamics relevant to debates in environmental governance across multiple scales. It also expands Fletcher's (2010) earlier “environmentalities” work, which applies Foucault's (2008) fourfold governmentality analytic to the field of environmental governance, by allowing for deeper engagement with the hybridized and overlapping nature of governmentalities when understood through their distinct philosophies and governance practices. As a way of mediating between the diverse economies approach to noncapitalocentrism and the material dominance of the global capitalist system, the interconnections and tensions that emerge through this framework offer insight into the real power dynamics that exist between structure and agency in governance discourse and practice. Importantly, this framework provides a common conceptual language for addressing complexity in governance dynamics to resolve confusion over how certain policies and practices are being categorized, toward the ultimate goal of identifying more sustainable or even emancipatory forms of governance, both material and conceptual. Fletcher's (2019) environmentalities analytic has been applied in research on ecotourism and environmental governance in Bhutan, for example, to demonstrate the relevance of this approach in identifying overlapping and contrasting governance rationalities beyond the otherwise flattening lens of “variegated neoliberalization” (Montes, 2019). Applied to critical surf tourism studies, then, this framework can allow for a more nuanced understanding of the power dynamics observed in the socio-ecological governance of surf tourism destinations and provide a useful analytical tool for mapping diversity in governance philosophies, principles, practices and subjectivities beyond conflated, variegated or monolithic interpretations of surfscape governmentality. Highlighting the utility of this lens, we discuss how the application of Fletcher's (2019) framework can support alternative theoretical approaches in critical surf tourism research aligned with communal governmentality and associated communal governance practices that may work to challenge neoliberal growth-for-development models in potentially liberatory ways.

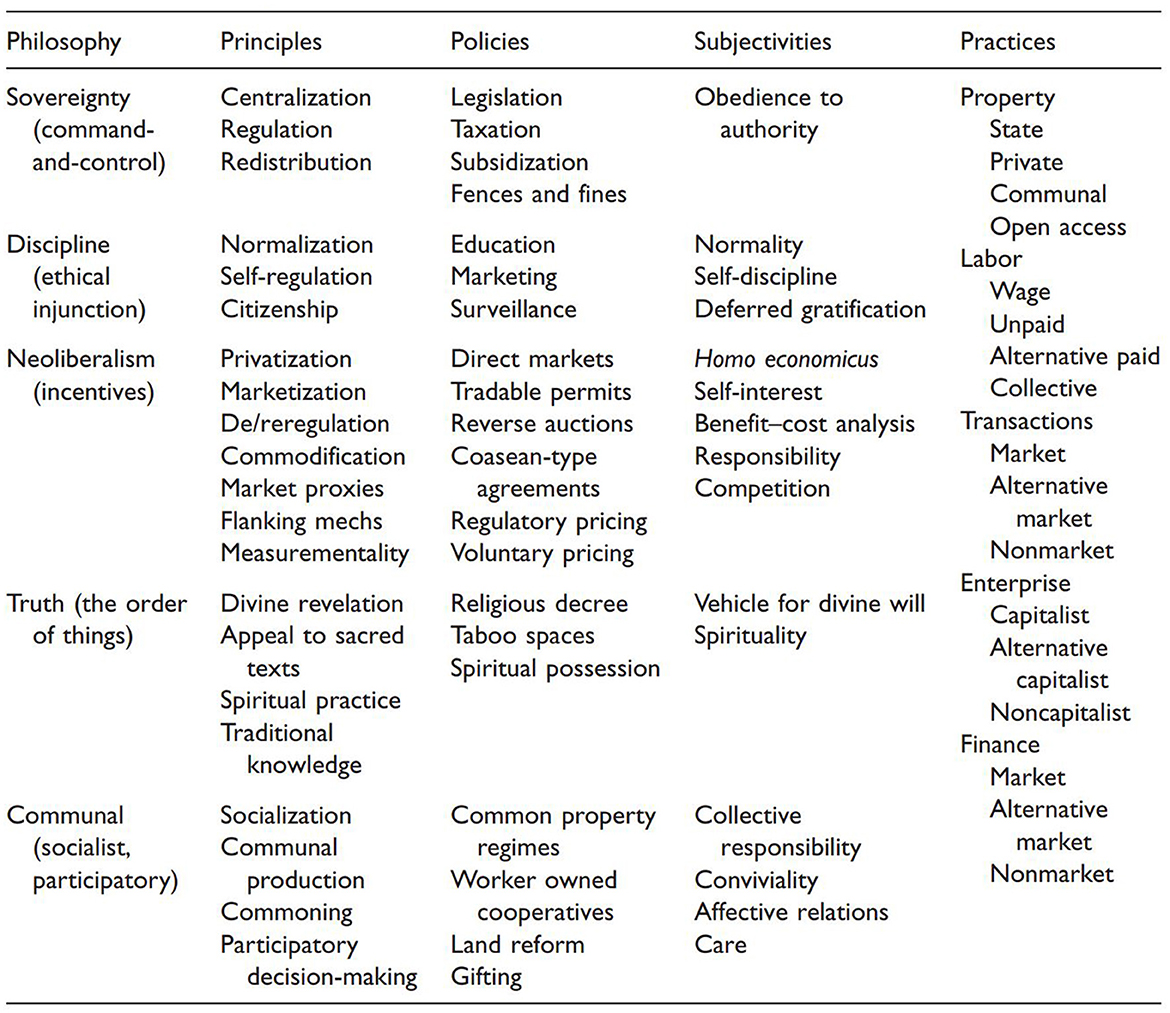

Figure 1 provides Fletcher's (2019) diverse ecologies framework in full, categorizing governance principles, policies, and subjectivities across the five governmentality philosophies, as follows:

1. Sovereignty, representing a philosophy of command-and-control styles of governance, through principles of centralization, regulation and distribution; policies of legislation, taxation, subsidization, and fences and fines; and subjectivities characterized by an obedience to authority.

2. Discipline, reflecting a philosophy of ethical injunction, based on principles of normalization, self-regulation and citizenship; policies of education, marketing and surveillance; and subjectivities of normality, self-discipline and deferred gratification.

3. Neoliberalism, founded on a philosophy of incentives, principles of privatization, marketization, de/reregulation, commodification, market proxies, flanking mechanisms, and measurementality; policies including direct markets, tradable permits, reverse auctions, Coasean-type agreements, regulatory and voluntary pricing, and homo economicus subjectivities based on self-interest, benefit-cost analysis, responsibility and competition.

4. Truth, a philosophy rooted in the order of things, based on principles of divine revelation, appeal to sacred texts, spiritual practice, and traditional knowledge, policies including religious decree, taboo spaces, and spiritual possession, and subjectivities defined by being a vehicle for divine will and spirituality.

5. Communal, a socialist/participatory philosophy based on principles of socialization, communal production, commoning, and participatory decision-making; policies including common property regimes, worker-owned cooperatives, land reform, and gifting; and subjectivities nurtured through collective responsibility, conviviality, affective relations, and care.

Figure 1. Diverse ecologies. From Fletcher (2019 p. 495).

These definitions of each governmentality philosophy are categorized into their corresponding principles, policies and subjectivities in the diverse ecologies framework (see Figure 1), with examples given of each to differentiate among them and support the analysis of diverse, often overlapping governance approaches. The final column lists diverse economic practices across the categories of (a) property, divided into state, private, communal and open access; (b) labor: wage, unpaid, alternative paid and collective; (c) transactions: market, alternative market, and non-market; (d) enterprise: capitalist, alternative capitalist and non-capitalist; and (e) finance: market, alternative market, and non-market. These are adopted from Gibson-Graham et al. (2013) and can be analyzed in relation to the different governance categories listed to highlight the interconnections among governance approaches and economic practices, or be analyzed on their own as a separate diverse economies inquiry (see Ruttenberg, 2022). Together, the governmentality philosophies, principles, policies, subjectivities and diverse economic practices in the diverse ecologies framework offer a conceptual map for categorizing complex dynamics in socio-ecological governance. As an analytical tool, researchers have applied Fletcher's (2019) multiple governmentalities/environmentalities framework in a range of contexts, including climate change adaptation and forest conservation in Guyana and Suriname (Collins, 2019); ecotourism and environmental governance in Bhutan (Montes, 2019); conservation governance in Jasper National Park, Canada (Youdelis, 2019); conservation and development strategies in the Peruvian Amazon (Chambers et al., 2019); water governance and rural-urban subjectivities in Latin America (Hommes et al., 2019); resource management in post-conflict Timor Leste (Cullen, 2019), among others.

Applied here to the field of surf tourism governance as a novel intervention, the multiple governmentalities framework provides the basis for our subsequent analysis of surfscape governmentality, following a brief discussion of our discursive and empirical methods employed.

Methodology: discourse analysis and review of empirical research

In effort to make use of Fletcher's (2019) framework to map surfscape governmentality, we draw from discursive methods to highlight a rich diversity of surf tourism governance practices. We engage with discourse analysis of selected texts and a specific review of our previous empirical research on surf tourism governance (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2019, 2022; Brosius and Ruttenberg, 2025). These methods provide a means of analyzing diversity in surfscape governance, while broadening theoretical and empirical discussions on governmentality in critical surf tourism research.

First, we engage with deconstruction as a method of discourse analysis that “reads for difference” the literature on surf tourism governmentality. This approach to reading for difference, rather than dominance, serves as a counterhegemonic practice illuminating heterogeneity and multiplicity in governance approaches where monolithic or conflated conceptions of neoliberal governmentality currently dominate (Derrida, 1978; Gibson-Graham, 2006; Ruccio, 2000). Specifically, we analyze the surf tourism governance practices discussed in Mach and Ponting's (2018) “Governmentality and Surf Tourism Destination Governance”; Hough-Snee and Eastman's (2017) “Consolidation, Creativity, and (de)Colonization in the State of Modern Surfing”; and our own recent work on the surfscape commons: “Surfscapes of Entitlement, Localisms of Resistance: Toward a Critical Typology of Localisms in Occupied Surfing Territories” (Brosius and Ruttenberg, 2025) and “Critical Localisms in Occupied Surfscapes: Commons Governance, Entitlement and Resistance in Global Surf Tourism” (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022). We pay particular attention in these texts to the example of Barra de la Cruz in Oaxaca, Mexico to highlight the diversity of practices discussed and tensions among the ways they are described and defined in relation to the multiple governmentalities framework. This deconstructionist method of analysis seeks to “highlight moments of contradiction and undecidability in what appears to be a neatly conceived structure or text” (Ruccio, 2000) and destabilizes existing discursive formations as a post-structuralist project of knowledge-making that participates “in the constitution of power, subjectivity and social possibility” (Gibson-Graham, 2000). Through distinguishing and deconstructing the governance practices and governmentalities discussed in the existing literature through these anti-essentialist methods of analysis, we are able to subsequently categorize them across Fletcher's (2019) diverse ecologies framework. This allows for the articulated identification of potentially liberatory communal and other governmentality philosophies, principles, policies, practices and subjectivities in surf tourism governance that may have been obscured, ignored or defined as “neoliberal” through otherwise variegated, conflated or monolithic perspectives on surfscape governmentality.

To strengthen and complement this discursive analysis, we review our own previous fieldwork in Barra de la Cruz, conducted in August 2019 and published as empirical research on the surfscape commons (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022; Brosius and Ruttenberg, 2025). The ethnographic approach employed for that study centered methods of self-reflective, critical ethnography, reminiscent of Stranger's (2011) “unorthodox ethnography,” which honors a long-term “participant-as-observer” role for critical surfer-researchers in embedded cultural research (Canniford, 2005; Stranger, 2011; Koot, 2016; Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2019, 2022). In awareness of our researcher positionality as insider-outsiders among the governance dynamics in different surfscapes, ethnography provided a multi-sited and multi-method “bricolage” approach (Lévi-Strauss, 1962; Derrida, 1978; Denzin and Lincoln, 2003) to “take account of the relationship between the observer and the observed, but also the relationship between the… worlds they belong to” (Stranger, 2011, p. 11). Ethnographic research in other surf-related scholarship (see Olive, 2016; Olive et al., 2016; Wheaton and Olive, 2023) speaks similarly to the insider/outsider experience of “going surfing as a research method” that “situates [us] in the physical and cultural worlds… that [our] research focuses upon…. keep[ing] the context, the research and the theory explicitly connected, and the analysis relevant to and reflective of participants' lives” (Olive, 2020, p. 122–126). Aligned with existing ethnographic work in the field, this multi-sited/multi-method approach connected our lived experiences as surfers, surfing tourists and surfer-researchers, across innumerable surfscapes over the course of decades, with the critical empirical research conducted in situ in the specific surfscape territory of Barra de la Cruz, as well as the availability of existing secondary sources as additional reference, including documents defining local community governance practices and customs.

Ethnographic research was conducted in Barra de la Cruz in August 2019, including participant observation at the sites of the main surf break, three locally-run hostels and hotels, the community-run cooperative restaurant on the beach, and locally owned businesses in town including a restaurant, pharmacy and grocery store; as well as eight semi-structured interviews with local and visiting surfers, local surf guides, community residents and leaders of the community assembly. Through both convenience sampling and snowball sampling, interview informants were selected based on existing relationships developed from past visits to this specific surfscape in 2017 and 2018, as well as supportive suggestions from other interviewees (see Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022; Brosius and Ruttenberg, 2025 for extended analysis and conclusions from this research). Through revisiting this critical ethnography in Barra de la Cruz, in conjunction with the anti-essentialist reading of the surfscape governmentality texts as described above, we identify specific governance philosophies, principles, policies, practices and subjectivities based on Fletcher's (2019) multiple governmentalities framework to offer a broad analysis of surfscape governmentality. This effort serves to link the material and discursive implications of surf tourism governance diversity with broader critical discussions on liberatory politics and ecologies in surfscape territories and surf culture imaginaries.

Discussion: multiple governmentalities in surf tourism governance

As discussed in the literature review above, Mach and Ponting (2018) identify and categorize a number of surf tourism governance approaches across Foucault's sovereign, disciplinary and neoliberal governmentalities. We begin here by revisiting that discussion and engaging with our own published empirical research on surf localism and the surfscape commons to gain a broader, more articulated understanding of surf tourism governmentalities and their associated power dynamics as analyzed through Fletcher's (2019) diverse ecologies framework. Reading for difference the existing literature on surf tourism governance and drawing from our own critical surfscape ethnographies in Barra de la Cruz, Mexico, we discuss the multiple governmentality philosophies, principles, policies, subjectivities and practices we are able to identify in the context of surfscape governance. We complete our analysis by highlighting the diverse governance approaches aligned with communal governmentality and/or identified as potentially supportive of an existing/emerging liberatory politics in Global South surfscape territories and imaginaries.

First, Mach and Ponting (2018, p. 5) categorize government restrictions on coastal access (including military zones and government-supported wave privatization by surf resorts in places like Fiji and the Maldives) and surf localism, defined as “powerful local actors who control and organize wave use behavior through the direct threat of punishment” as representing sovereign governmentality. Second, they categorize “the surfer's code,” or the informal “rules” of surfing based on adherence to established norms of hierarchical meritocracy and conformity to the hegemonic ideals of modern surf culture, as an example of disciplinary governmentality. Finally, neoliberal governmentality is discussed as including a range of practices: surf lessons, coaches, guides, boat charters, beach access fees, surfonomics, surf philanthropy and international surf organizations focused on purchasing land and/or lobbying governments and communities to conserve wave resources, surf voluntourism, and monetized practices like locals “blocking” for surf tourists. Specifically, the governance practices employed by the community of Barra de la Cruz, Mexico—including beach restrictions and associated access fees, the cooperative-run restaurant, and tourism revenue distribution policies determined through the autonomous local assembly—are identified as “coopting” or “appropriating neoliberal governmentality to limit surf break access” (Mach and Ponting, 2018, p. 10). Writing prior to Fletcher's (2019) multiple governmentalities framework, Mach and Ponting (2018, p. 4) acknowledge the dynamics of surf tourism governmentalities “coexist[ing] in any given context, alternately conflicting or acting in concert (Fletcher, 2010, p. 176),” but they do not include discussion of truth or communal governmentalities. Incorporating Fletcher's (2019) framework as a theoretical advancement in critical surf tourism research thus allows us to build on and extend earlier understandings of governance dynamics in surf tourism scenarios.

Our recent critical interventions on the topics of surf localism(s) and the surfscape commons complicate Mach and Ponting (2018) categorizations while offering a new set of conclusions regarding governmentality in surf tourism governance. For example, while localism is treated in Mach and Ponting (2018) as monolithically representative of sovereign governmentality, our typological differentiation of diverse localisms of entitlement/resistance in occupied surfscapes serves to address important power dynamics otherwise conflated, flattened or obscured as “sovereign” (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2019; Brosius and Ruttenberg, 2025). Here, we distinguish among expressions of localism that perpetuate racialized, neocolonial, neoliberal and gendered constructs in modern surfing culture from those that potentially challenge or subvert them. This is significant to the discussion on governmentality because our research identifies certain enactments of Global South localisms of resistance, along with girl localism(s), as potentially emancipatory practices of surfscape “commoning,” which Fletcher identifies as a principle of communal governmentality. On the other hand, Global North localisms of entitlement are determined through our analysis to uphold the colonial-patriarchal norms of modern surf culture in ways reminiscent of disciplinary governance, while also perpetuating neoliberal practices of surf resource privatization by individual surfers who consider themselves “local” to places as a result of processes of dispossession and erasure characteristic of colonization and gentrification in places like California (Brosius and Ruttenberg, 2025).

Again, the example of Barra de la Cruz is perhaps most illustrative of diverse governmentalities that “overlap, lean on each other, challenge each other, and struggle with each other” (Foucault, 2008, as cited in Fletcher, 2019, p. 9). Whereas both Mach and Ponting (2018) and Hough-Snee and Eastman (2017) emphasize the town's neoliberal character, and Mach and Ponting (2018) conflate certain market-oriented economic practices with “appropriating neoliberal governmentality,” our research highlights both the communal and sovereign nature of Barra de la Cruz's surf tourism governance model. Our ethnographic research (Ruttenberg and Brosius, 2022, p. 81–82) discusses the relationships among surf localism, surfscape commoning, and surf tourism governance in Barra de la Cruz as follows:

The [predominantly male] local surfers who display dominance through aggressive forms of regulation in the water [also participate in] the community's citizen assembly established in 2017, comprised of around 600 voting members, including nearly fifty percent women. The assembly includes an annually rotating leadership and labor model aligned with protocols formally dictated by the “Uses and Customs” of the indigenous communities of Oaxaca, and functions autonomously from the Mexican federal government, unless the community requests formal support from federal security forces (see IEEPCO, 2003). The two main enterprise mechanisms of the community assembly are both cooperatives—the community-run restaurant on the beach frequented by surfers and the guarded entrance gate to the beach access road, where visiting surfers pay approximately $1.30 USD per visit. Funds from these cooperative enterprises are invested in local community celebrations, services and organizations including a health center, preschool, kindergarten, primary and secondary schools, freshwater committee, and community police. Community assembly members are obligated to contribute monetarily to community celebrations and participate in organized tekios, unpaid community work projects, such as road or building construction. Benefits include community-run social services and health insurance for the sick and elderly. Failure to comply results in punishment including imprisonment and fines. Assembly membership is open to all community locals 18 years of age and older.

Land rights to property and business ownership are limited to native community residents (determined by birthright), and foreigners are explicitly prohibited from owning land or businesses. Construction is prohibited on the beach, which has been designated as a turtle conservation area since 1984, when community residents who lived on the beach were relocated to the town center and surrounding areas. Private businesses run by local community members include restaurants, small supermarkets, pharmacy, internet café, mechanic and cabina-style guest accommodations along the road to the beach. Surf tourism is the third cooperatively run and community managed framework in Barra de la Cruz, following the turtle conservation initiative and the lagoon where the community works together to harvest tilapia and mojarra for consumption and sale…. Seen through the lenses of “commoning” and “defending a commons,” we might understand the Barra de la Cruz efforts as an example of commoning the surfscape, whereby terms of access, care and responsibility are decided communally, with taxation benefits accruing to the community cooperative and the townspeople, and surfers regulating the surfbreak through localism as a territorial extension of defending their surfscape commons against threats of occupation. As such, we propose that through localism in the surf and on land, the Barra de la Cruz community is establishing commons governance to prevent the types of neocolonial and foreign neoliberal encroachment we see in other Global South surf tourism destinations the world over.

As this excerpt details, while some local businesses are privately owned and specific income generating mechanisms are employed to leverage surf tourism revenue for both individual/family and communal benefit, Barra's surf tourism management framework actually integrates an array of communal and sovereign governmentality philosophies, principles, policies, practices and subjectivities to resist surfscape neoliberalization. Significantly, their surf tourism management model is determined by a local indigenous community governance assembly that functions autonomously from the Mexican state, such that policies dictating surfscape commons access and resource ownership, as well as taxation and income redistribution, are democratically governed by the community assembly as sovereign, with membership rights and obligations open, but not compulsory, for all adult community members. Cooperative community enterprises fuel redistributive efforts for local projects, and regulations restrict coastal development while preventing non-locals from owning land or businesses.

Within this broader governance milieu, acknowledging local surfers' participation in the citizen assembly and related community practices described above, we suggest that localism at the site of the surf break in Barra, conducted through common tactics of local, predominantly male surfers asserting priority on waves, regulating access to the lineup, and policing visitors' behavior in the water, might be seen as not only a sovereign governance practice but also potentially representative of a wider communal governmentality philosophy. As participants and beneficiaries of the broader community governance dynamics in Barra, locals in the water might thus be seen as establishing priority for themselves as Barra natives and other local surfers vis-à-vis visiting tourists, in much the same way that the Barra community preserves local ownership and community autonomy through the communal governance practices described above. Finally, while we were not privy to the internal dynamics of community assembly proceedings, which may have shed further light on instances of disagreement or contestation, we did learn of community members rumored to have faced sovereign repercussions for disobeying community governance norms by attempting to develop coastal lands. This attempt might be interpreted as an enactment of neoliberal subjectivity within a communal governance philosophy regulated through sovereign practices policing obedience to local community authority. We recognize our short formal ethnographic research period, and our positionality as outsider researchers as limitations of this study, as we may have learned more about internal community affairs and existing contestations if we had sat in on an assembly meeting, or been privy to more sensitive information regarding instances of conflict, which informants understandably may not have been comfortable sharing with outside researchers. It is also important to note that while communal governmentality is described by Fletcher (2019) as representing a socialist governance philosophy (see Figure 1), research informants did not refer to the community assembly or governance practices as specifically “socialist” in any of our interviews, though socialized ethics and practices were observed empirically in the community-run surf tourism governance model, as discussed here.

Integrating these ethnographic details into the diverse ecologies framework, we can identify sovereign principles of regulation and redistribution, sovereign policies of taxation, subsidization and fences and fines; neoliberal principles of privatization, marketization, and commodification, neoliberal policies of regulatory pricing; communal principles of socialization, communal production, commoning, and participatory decision-making; communal policies of common property regimes, worker-owned cooperatives, and land reform; communal subjectivities of collective responsibility; as well as a diverse array of economic practices including private and communal property, wage, alternative paid and collective labor, market, alternative market and nonmarket transactions, capitalist, alternative capitalist and noncapitalist enterprise, as well as market and alternative market finance. We can also identify elements of sovereign, neoliberal, and communal governmentality philosophies, whereby socialist and participatory ethics, as well as economic incentives and command-and-control modes of governance intersect in complex and meaningful ways. Understood through the diverse ecologies lens, the governmentality landscape in Barra de la Cruz can be recognized for its socio-ecological complexity and multiplicity of governance approaches comprising their unique community-run surf tourism governance model. Flattening this diverse landscape into the category of neoliberal governmentality as monolith tells an inaccurate story and does a disservice to the self-determined and liberatory essence of this autonomous governance model and its attendant communal governance practices that challenge and resist surfscape neoliberalization in powerful ways.

Conclusion: toward recognizing complexity in surf tourism governance

In this article, we sought to revisit the topic of governmentality in surf tourism governance by “reading for difference” the existing surfscape governmentality literature through the novel conceptual approach of Fletcher's (2019) multiple governmentalities framework. As a “diverse ecologies” application of Gibson-Graham's well-known diverse economies model, this framework provides the basis for identifying diverse governance philosophies, principles, policies, subjectivities, and practices across Foucault's (2008) categories of sovereign, discipline, neoliberal, truth, and communal governmentalities. Reviewing these categories as presented in the existing surfscape governmentality literature, including in our own previous empirical research, our analysis suggests that there is greater nuance and deeper complexity inherent in local community-based approaches to surf tourism governance than currently discussed in the related scholarship. This analysis serves to highlight: (a) the distinct communal, disciplinary and neoliberal governmentality expressions of diverse Global North and Global South surfscape localisms; and (b) the overlapping mosaic of communal, sovereign and neoliberal surf tourism governance approaches that have been problematically flattened into the category of neoliberal governmentality in existing literature, as in the unique case of Barra de la Cruz, Mexico. Identifying multiple surfscape governmentalities in this way is useful for recognizing local community self-determination and potentially liberatory expressions of communal surfscape governmentality resisting neoliberalism in surf tourism destinations in the here and now.

Potential limitations of this study include the brief duration of the empirical field work analyzed and the limited available corpus of existing research specific to governmentality in surf tourism. Future investigation might explore a broader comparative analysis of multiple surfscapes, or alternative theoretical frameworks on surf tourism governance. While deeper analysis into other community-based surfscape governance models are beyond the scope of this article, we offer this application of Fletcher's diverse governmentalities framework toward further related research into communal governmentality approaches in support of emancipatory socioecological futures in post-pandemic surf tourism governance and research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TR: Writing – original draft. JB: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amrhein, S. (2023). “Overtourism, dependencies and protests: challenging the ‘support narrative,”' in Coping with Overtourism in Post-Pandemic Europe: Approaches, Experiences and Challenges, eds. G. Hospers, and S. Amrhein (Berlin: LIT), 153–167.

Anderson, J. (2014). Surfing between the local and the global: identifying spatial divisions in surfing practice. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 39, 237–249. doi: 10.1111/tran.12018

Bellato, L., Frantzeskaki, N., Emma, L., Cheer, J. M., and Peters, A. (2024). Transformative epistemologies for regenerative tourism: towards a decolonial paradigm in science and practice? J. Sustain. Tour. 32, 1161–1181. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2023.2208310

Bellato, L., Frantzeskaki, N., and Nygaard, C. A. (2023). Regenerative tourism: a conceptual framework leveraging theory and practice. Tour. Geogr. 25, 1026–1046. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2022.2044376

Bellato, L., and Pollock, A. (2023). Regenerative tourism: a state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1–10. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2023.2294366

Blázquez-Salom, M., Cladera, M., and Sard, M. (2023). Identifying the sustainability indicators of overtourism and undertourism in Majorca. J. Sustain. Tour. 31, 1694–1718. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2021.1942478

Bollier, D. (2014). Think like a commoner: A Short Introduction to the Life of the Commons. Gabriola, BC: New Society Publishers.

Brosius, J. P., and Ruttenberg, T. (2025). “Surfscapes of entitlement, localisms of resistance: toward a critical typology of localisms in occupied surfing territories,” in Waves of Belonging: Indigeneity, Race, and Gender in the Surfing Lineup, eds. J Ponting., L. Heberling, and D. Kamper (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press). In press.

Buckley, R. C., Guitart, D., and Shakeela, A. (2017). Contested surf tourism resources in the Maldives. Ann. Tour. Res. 64, 185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2017.03.005

Burtner, J., and Castañeda, Q. (2010). Tourism as a force for world peace: the politics of tourism, tourism as governmentality, and the tourism Boycott of Guatemala. J. Tour. Peace Res. 1, 1−21.

Canniford, R. (2005). Moving shadows: suggestions for ethnography in globalised cultures. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 8, 204–218. doi: 10.1108/13522750510592463

Carroll, R. (2015). California's surf wars: wave ‘warlords' go to extreme lengths to defend their turf. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2015/may/18/california-surf-wars-lunada-bay-localism-surfing

Castree, N. (2010). (2010). Neoliberalism and the biophysical environment: a synthesis and evaluation of the research. Environ. Soc. Adv. Res. 1, 5–45. doi: 10.3167/ares.2010.010102

Cave, J., and Dredge, D. (2018). Reworking tourism: diverse economies in a changing world. Tour. Plann. Dev. 15, 473–477. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2018.1510659

Cave, J., and Dredge, D. (2020). Regenerative tourism needs diverse economic practices. Tour. Geogr. 22, 503–513. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1768434

Chambers, J., Del Aguila Mejia, M., Ramirez Reategui, R., and Sandbrook, C. (2019). Why joint conservation and development projects often fail: an in-depth examination in the Peruvian Amazon. Environ. Plan. E: Nat. Space 3, 365–398. doi: 10.1177/2514848619873910

Cheong, S., and Miller, M. (2000). Power and tourism: a foucauldian observation. Ann. Tour. Res. 27, 371–390. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00065-1

Collins, Y. (2019). How REDD+ governs: multiple forest environmentalities in Guyana and Suriname. Environ. Plan. E: Nat. Space 3, 323–345. doi: 10.1177/2514848619860748

Comer, K. (2010). Surfer girls in the New World Order. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780822393153

Cullen, A. (2019). Transitional environmentality – understanding uncertainty at the junctures of eco-logical production in Timor-Leste. Environ. Plan. E: Nat. Space 3, 423–441. doi: 10.1177/2514848620908201

Daskalos, C. (2007). Locals Only! The impact of modernity on a local surfing context. Sociol. Perspect. 50, 155–173. doi: 10.1525/sop.2007.50.1.155

Denzin, N., and Lincoln, Y., (eds.). (2003). Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. London: Sage.

Derrida, J. (1978). Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences. Writing and Difference (Transl. by A. Bass). London: Routledge, 278–294.

Ernst, M. (2014). Crowdfunded: Surfing is one of the biggest businesses on Bali and blocking for a client is good business. The Surfer's Journal. Available at: https://www.surfersjournal.com/feature/crowdfunded/ (accessed March 15, 2016).

Evers, C. (2008). The cronulla race riots: safety maps on an Australian beach. South Atl. Q. 107, 411–429. doi: 10.1215/00382876-2007-074

Fletcher, R. (2010). Neoliberal environmentality: towards a poststructuralist political ecology of the conservation debate. Conserv. Soc. 8, 171–181. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.73806

Fletcher, R. (2013). Bodies do matter: the peculiar persistence of neoliberalism in environmental governance. Hum. Geogr. 6, 29–45. doi: 10.1177/194277861300600103

Fletcher, R. (2019). Diverse ecologies: mapping complexity in environmental governance. ENE: Nat. Space 3, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/2514848619865880

Fletcher, R., Murray Mas, I., Blázquez-Salom, M., and Blanco-Romero, A. (2020). Tourism, Degrowth, and the COVID-19 Crisis. Center for Space, Place and Society. Available at: https://centreforspaceplacesociety.com/2020/03/27/degrowth/ (accessed March 27, 2020).

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2000). “Poststructural interventions,” in A Companion to Economic Geography, eds. E. Sheppard, and T. Barnes (Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishers), 95–110. doi: 10.1002/9780470693445.ch7

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Gibson-Graham, J. K., Cameron, J., and Healy, S. (2013). Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide For Transforming Our Communities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. doi: 10.5749/minnesota/9780816676064.001.0001

Gibson-Graham, J. K., Cameron, J., and Healy, S. (2016). “Commoning as postcapitalist politics,” in Releasing the Commons: Rethinking the Futures of the Commons, eds. A. Amin, and P. Howell (New York, NY: Taylor and Francis), 192–212. doi: 10.4324/9781315673172-12

Gilio-Whitaker, D. (2017). “Appropriating surfing and the politics of Indigenous authenticity,” in The Critical Surf Studies Reader, eds. D. Zavalza Hough-Snee, and A. Sotelo Eastman (Durham: Duke University Press), 214–234. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv111jh9f.15

Guerrón Montero, C. (2014). Multicultural tourism, demilitarization, and the process of peace building in Panama. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anth. 19, 418–440. doi: 10.1111/jlca.12103

Hargreaves, J. (1987). “The body, sport, leisure and social relations,” in Sport, Leisure and Social Relations, Sociological Review Monograph, eds. J. Horne, D. Jary, and A. Tomlinson (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul).

Hofmann, S. (2013). Tracing contradictions of neoliberal governmentality in Tijuana's sex industry. Anthropol. Matters J. 15, 62–89.

Hollinshead, K. (1999). Surveillance of the worlds of tourism: foucault and the eye-of power. Tour. Manag. 20, 7–23. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00090-9

Hollinshead, K. (2003). Symbolism in tourism: lessons from ‘Bali 2002'—lessons from Australia's dead heart. Tour. Anal. 8, 267–296. doi: 10.3727/108354203774077129

Hommes, L., Boelens, R., Bleeker, S., Duarte-Abadia, B., Stoltenborg, D., Vos, J., et al. (2019). Water governmentalities: the shaping of hydrosocial territories, water transfers and rural–urban subjects in Latin America. Environ. Plan. E: Nat. Space 3, 399–422. doi: 10.1177/2514848619886255

Hough-Snee, D., and Eastman, A. (2017). “Consolidation, creativity, and (de)colonization in the state of modern surfing,” in The Critical Surf Studies Reader, eds. D. Hough-Snee, and A. Eastman (Durham: Duke University Press), 84–108. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv111jh9f.9

IEEPCO (2003). Catalogo Municipal de Usos y Costumbres [Online]. Instituto Estatal Electoral de Oaxaca. Available at: http://www.ieepco.org.mx/biblioteca_digital/Cat_UyC_2003/PRESENTACION/PRESENTACION.pdf

Kaffine, D. (2009). Quality and the commons: the Surf Gangs of California. J. Law Econ. 52, 727–743. doi: 10.1086/605293

Koot, S. (2016). Perpetuating power through autoethnography: my research unawareness and memories of paternalism among the indigenous Hai//om in Namibia. Crit. Arts 30, 840–854. doi: 10.1080/02560046.2016.1263217

Laderman, S. (2014). Empire in Waves: A Political History of Surfing. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/california/9780520279100.001.0001

Lemarié, J. (2016). Debating on cultural performances of hawaiian surfing in the 19th century. J. Soc. Océan. 142–143, 159–173. doi: 10.4000/jso.7625

Lemarie, J. (2019). The critical surf studies reader, edited by Dexter Zavalza Hough-Snee and Alexander Sotelo Eastman. Tour. Geogr. 22, 214–217. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2019.1583275

Mach, L., and Ponting, J. (2017). “A nested socio-ecological systems approach to understanding the implications of changing surf-reef governance regimes,” in Lifestyle Sports and Public Policy, eds. D. Turner and S. Carnicelli (New York, NY: Routledge).

Mach, L., and Ponting, J. (2018). Governmentality and surf tourism destination governance. J. Sustain. Tour. 26, 1845–1862. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2018.1513008

Mihalic, T. (2020). Conceptualising overtourism: a sustainability approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 84, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103025

Mixon, F. (2014). Bad vibrations: new evidence on commons quality and localism at California's surf breaks. Int. Rev. Econ. 61, 379–397. doi: 10.1007/s12232-014-0205-9

Mixon, F. (2018). Camaraderie, common pool congestion, and the optimal size of surf gangs. Econ. Gov. 19, 381–396. doi: 10.1007/s10101-018-0211-6

Mixon, F., and Caudill, S. (2018). Guarding giants: resource commons quality and informal property rights in big-wave surfing. Empir. Econ. 54, 1697–1715. doi: 10.1007/s00181-017-1273-y

Montes, J. (2019). Neoliberal environmentality in the land of Gross National Happiness. Environ. Plan. E: Nat. Space 3, 300–322. doi: 10.1177/2514848619834885

Mosedale, J. (2017). “Diverse economies and alternative economic practices in tourism,” in The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies: Creating an Academy of Hope, eds. N. Morgan, I. Ateljevic, and A. Pritchard (London and New York: Routledge).

Moser, P. (2020). The Hawaii Promotion Committee and the appropriation of surfing. Pac. Hist. Rev. 89, 500–527. doi: 10.1525/phr.2020.89.4.500

Nazer, D. (2004). The tragicomedy of the surfers' commons. Deakin Law Rev. 9, 655–713. doi: 10.21153/dlr2004vol9no2art259

O'Brien, D., and Ponting, J. (2013). Sustainable surf tourism: a community centered approach in Papua New Guinea. J. Sports Manag. 27, 158–172. doi: 10.1123/jsm.27.2.158

Olive, R. (2015). “Surfing, localism, place-based pedagogies and ecological sensibilities in Australia,” in Routledge International Handbook of Outdoor Studies, eds. B. Humberstone, H. Prince, and K. Henderson (London: Routledge), 501–510. doi: 10.4324/9781315768465-56

Olive, R. (2016). Going surfing/doing research: learning how to negotiate cultural politics from women who surf. Continuum 30, 171–182. doi: 10.1080/10304312.2016.1143199

Olive, R. (2019). The Trouble with newcomers: women, localism and the politics of surfing. J. Aust. Stud. 43, 39–54. doi: 10.1080/14443058.2019.1574861

Olive, R. (2020). “Thinking the social through myself: reflexivity in research practice,” in Research Methods in Outdoor Studies, eds. B. Humberstone and H. Prince (121–129).

Olive, R., McCuaig, L., and Phillips, M. (2015). Women's recreational surfing: a patronising experience. Sport Educ. Soc. 20, 258–276. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2012.754752

Olive, R., Thorpe, H., Roy, G., Nemani, M., lisahunter, Wheaton, B., and Humberstone, B. (2016). “Surfing together: exploring the potential of a collaborative ethnographic moment,” in Women in Action Sport Cultures: Identity, Politics and Experience, eds. H. Thorpe, and R. Olive (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 45–68. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-45797-4_3

Ponting, J., and O'Brien, D. (2014). Liberalizing Nirvana: an analysis of the consequences of common pool resource deregulation for the sustainability of Fiji's surf tourism industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 22, 384–402. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.819879

Ruccio, D. (2000). “Deconstruction,” in Handbook of Economic Methodology, eds. J. Davis, D. W. Hands, and U. Maki (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar).

Ruttenberg, T. (2022). Alternatives to development in surfing tourism: a diverse economies approach. Tour. Plan. Dev. 20, 1082–1103. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2022.2077420

Ruttenberg, T., and Brosius, J. (2017). “Decolonizing sustainable surf tourism,” in The Critical Surf Studies Reader, eds. D. Hough-Snee, and A. Sotelo Eastman (Durham: Duke University Press), 109–134. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv111jh9f.10

Ruttenberg, T., and Brosius, J. (2019). “Surfscapes of entitlement, localisms of resistance: toward a typology of diverse localisms in occupied surfing territories,” in Paper presented at Impact Zones and Liminal Spaces: The Culture and History of Surfing (San Diego, CA: San Diego State University.

Ruttenberg, T., and Brosius, J. (2020). “Waves of development: surf tourism on trial in Costa Rica,” in The Ecolaboratory: Environmental Governance and Economic Development in Costa Rica, eds. R. Fletcher, G. Aistara, and B. Dowd-Uribe (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press), 204–216. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvxw3pvp.15

Ruttenberg, T., and Brosius, J. P. (2022). “Chapter III: Critical localisms in occupied surfscapes: commons governance, entitlement and resistance in global surf tourism,” in Decolonizing Surf Tourism: Alternatives to Development, Surfer Subjectivity and Surfscape Commons Governance, Doctoral Thesis, ed. T. Ruttenberg (Wageningen: Wageningen University and Research), 66–83.

Scott, P. (2003). We shall fight on the seas and the oceans… We shall: Commodification, Localism and Violence. M/C: J Media Cult. 6:2138. doi: 10.5204/mcj.2138

Stranger, M. (2011). Surfing Life: Surface, Substructure and the Commodification of the Sublime. Farnham: Ashgate.

Towner, N., and Lemarié, J. (2020). Localism at New Zealand surfing destinations: Durkheim and the social structure of communities. J. Sport Tour. 24, 93–110. doi: 10.1080/14775085.2020.1777186

Tribe, J. (2007). “Critical tourism: rules and resistance,” in The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies: Innovative Research Methods, eds. I. Ateljevic, A. Pritchard, and N. Morgan (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 29–39. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-045098-8.50007-6

Usher, L., and Gomez, E. (2016). Surf localism in Costa Rica: exploring territoriality among Costa Rican and foreign resident surfers. J. Sport Tour. 20, 195–216. doi: 10.1080/14775085.2016.1164068

Usher, L., and Kerstetter, D. (2014). Re-defining localism: an ethnography of human territoriality in the surf. Int. J. Tour. Anthropol. 4, 286–302. doi: 10.1504/IJTA.2015.071930

Usher, L., and Kerstetter, D. (2015). Surfistas locales: transnationalism and the construction of surfer identity in Nicaragua. J. Sport. Soc. Issues 39, 455–479. doi: 10.1177/0193723515570674

Waitt, G. (2008). Killing waves: surfing, space, and gender. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 9, 75–94. doi: 10.1080/14649360701789600

Walker, I. (2011). Waves of Resistance: Surfing and History in Twentieth-Century Hawai'i. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. doi: 10.21313/hawaii/9780824834623.001.0001

Wheaton, B. (2017). “Space invaders in surfing's white tribe: exploring surfing, race, and identity,” in The Critical Surf Studies Reader, eds. D. Hough-Snee, and A. Eastman (Durham: Duke University Press), 177–195. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv111jh9f.13

Wheaton, B., and Olive, R. (2023). The challenges of ‘researching with responsibility': developing intersectional reflexivity for understanding surfing, place and community in Aotearoa New Zealand. Qual. Res. 24:14687941231216643. doi: 10.1177/14687941231216643

Youdelis, M. (2019). Multiple environmentalities and post-politicization in a Canadian Mountain Park. Environ. Plan. E: Nat. Space 3, 346–364. doi: 10.1177/2514848619879447

Keywords: surf tourism, surf tourism governance, governmentality, multiple governmentalities, critical surf tourism studies, communal governmentality, diverse ecologies, diverse economies

Citation: Ruttenberg T and Brosius JP (2025) Revisiting governmentality in surf tourism governance: a diverse ecologies approach. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1306582. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1306582

Received: 04 October 2023; Accepted: 17 December 2024;

Published: 09 January 2025.

Edited by:

Jeremy Lemarie, Reims University, FranceReviewed by:

Belinda Wheaton, University of Waikato, New ZealandLilia Khelifi, Université d'Angers, France

Copyright © 2025 Ruttenberg and Brosius. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tara Ruttenberg, dGFyYWNyMDdAZ21haWwuY29t

Tara Ruttenberg

Tara Ruttenberg J. Peter Brosius2

J. Peter Brosius2