95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Tour. , 27 September 2023

Sec. Disaster/Crisis Management and Resilience in Tourism

Volume 2 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsut.2023.1209325

This article is part of the Research Topic UN World Tourism Day 2022: Disaster/Crisis Management and Resilience in Tourism View all 5 articles

Introduction: The present work demonstrates how non-traditional tourism stakeholders' inclusion in planning and decision-making improves connectivity and helps to achieve resilience in rural tourist destinations. The geographical and temporal context for the study is the sector of El Balsamo in Manabi-Ecuador, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method: The methodology applied is a case study with data collection through interviews and applying the MERITS method to identify recurring themes when various stakeholders' opinions are included.

Results and discussion: The results of this study show the importance of inclusion and effective communication in building trust and long-term alliances in destination recovery processes. This study makes evident how the creation of networks and partnerships leveraged on effective communication and the prioritization of common objectives allows the permanence of these networks even after the crisis has been overcome.

This article examines the recovery and adaptation processes in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic as part of a comprehensive study of the intervention of critical stakeholders in the tourism sector and the inclusion of members from other sectors and disciplines in the resilience processes of the rural tourist communities. The goal is to provide a thoughtful and critical assessment of the strategies adopted by the El Balsamo- Ecuador community to deal with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research objective was to identify and understand how rural and community destinations develop and adopt adaptation strategies to increase resilience during the COVID-19 context. Three research objectives were identified for the study, namely: Identify the strategies that the El Balsamo destination employed in the recovery process in the face of the limitations imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic; examine the environmental and institutional factors that influenced the decision-making process and the implementation of tourism recovery strategies; and analyze the decision-making process and the inclusion of stakeholders in the recovery processes of the destination.

The justification behind the goal and the objectives of the research were three-fold. First, the study of El Balsamo in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and its recovery as a rural tourism destination represented a crucial empirical issue that needed to be analyzed in detail to fill the theoretical “gap” about how rural tourist communities develop resilience (Ruiz-Ballesteros, 2011; Caceres-Feria et al., 2021). Second, EL Balsamo provided the ideal context to analyze collaborative decision-making processes with the inclusion of various stakeholders. Finally, El Balsamo has been the subject of research in the biological field and tourism (Guerrero-Casado et al., 2020). However, the published material did not include the decision-making process of the stakeholders in the face of crises. The need for direct qualitative data was justified in response to the growing body of post-disaster knowledge from fieldwork (Johnson and Sieber, 2011; Gotham and Greenberg, 2014; Johnson and Olshansky, 2017). Unlike other studies on resilience in rural tourist communities, the methodology designed for this study explicitly addressed power dynamics with the decision-making process and the inclusion of stakeholders from other areas not directly related to the tourism sector. The study makes it possible to demonstrate the collaborative and interdisciplinary way of working, facing the difficulties of incorporating different points of view in decision-making, which is one of the limitations in the application of collaborative decision-making and inclusion processes. As a result, the research focused on documenting the multidisciplinary work in building the resilience of tourist destinations, adopting a case study methodology for the destination El Balsamo, Ecuador.

The term resilience has its etymological roots in the 16th and 17th centuries with the word “resilio,” which in Latin means “spring back,” in the 90s, resilience was used to describe the condition of elasticity of construction materials (Hall, 2018), and later in ecology was defined by Holling (1973) as a way to explain the characteristics of ecological systems capable of absorbing changes and returning to normality without losing their identity; thus, resilience was first perceived as an outcome framed within an engineering perspective fixated on the return of a status quo (Folke et al., 2010). The term resilience has expanded and extended to include more disciplines in the last decades, creating a proliferation of concepts that vary from both processes to outcomes; therefore, there is no universal definition of resilience across disciplines, nor in the tourism field, which is why its study continues to generate debate, and controversy (Hall et al., 2017; Amore et al., 2018). However, the lack of consensus when defining resilience has not prevented the existence of agreements regarding various characteristics of resilience. For example, resilience is widely accepted as a multidisciplinary construct and precursor of sustainable development (Basurto-Cedeño and Pennington-Gray, 2018).

In the same way, some approaches have had more acceptance among researchers; resilience can therefore be understood mainly from an engineering and socio-ecological point of view (Amore et al., 2018). Although engineering resilience has been criticized in the application of complex systems (such as tourist destinations) for the simplicity of its approach, focused on reinforcing the robustness of systems to increase the capacity to absorb changes and disturbances to return quickly to the previous status of equilibrium (bounce-back), its application in branches, like engineering and architecture, has allowed the continuity of physical and social structures after a crisis (Woods, 2015).

From the point of view of socio-ecological systems (SES), resilience is mostly conceptualized as an outcome that can be achieved through several factors that support change, and innovation at different scales, while maintaining the system identity in the face of internal and external stressors (Folke et al., 2010). Although there is a dichotomy between promoting change and maintaining the identity characteristics of the systems, resilience under this form of conceptualization recognizes that change is the only constant in the SES (Carpenter et al., 2005); and that in order to facilitate the continuity of the SES, there must be a space for change, evolution, and innovation. Thus, resilience is more than “bouncing back;” it is adapting and transforming to create new ways of functioning as a society to foster a better development path that admits change and uncertainty (Rockström et al., 2023).

Determining principles, dimensions, or factors that contribute to achieving resilience constitutes an important area in the literature (Biggs et al., 2015); the researchers argue that it is necessary to identify them to land concrete, quantifiable models that are easier to apply in destinations (Folke et al., 2010). Thus, Biggs et al. (2015) proposed seven principles to achieve the resilience of socio-ecological systems (SES). For them, these principles can be grouped into two groups; the first is aimed at managing the attributes of system governance and includes managing the inclusive participation of social actors, adopting a complex way of thinking that recognizes the various scales of systems, inclusive learning, and polycentrism of processes. On the other hand, the second group of principles focuses on the properties of the system itself. It includes the promotion of diversity and redundancies of the elements of the system, the connectivity between the elements of the system, and the monitoring of slow-changing variables and feedback.

In tourism, the concept of resilience traditionally refers to the industry's ability to bounce back from economic fluctuations (Chib, 1980; Holder, 1980). In the late 1990s and early 2000s, resilience evolved from a concept to a theory and various frameworks were developed (Basurto-Cedeño and Pennington-Gray, 2018). The literature on tourism resilience grew significantly by merging resilience theory and risk science (Pizam and Smith, 2000; Farrell and Twining-Ward, 2004). As such, researchers proposed various strategies to increase tourism resilience in destinations, such as reducing risks and enhancing the system's capacity to adapt to efficiently respond to crises and recover from them (Basurto-Cedeño and Pennington-Gray, 2018).

Specialty literature in tourism resilience has focused on understanding and promoting the resilience of destinations and businesses in the face of various agents of change, such as natural disasters, economic declines, political instability, and disease outbreaks, among others. From a tourism business point of view, resilience has been referred to as their ability to anticipate, adapt and recover from disruptions and shocks while maintaining the functionality of the business and its integrity. For the most part, tourism businesses' resilience has adopted an engineering approach, prioritizing the ability to absorb, cope, and “bounce back,” thus ensuring long-term sustainability.

In tourism, resilience has focused mainly on ensuring the continuity of tourism systems in the face of rapid variables that cause shocks or disturbances in the systems and how to ensure responses that allow recovery, adaptation, and success in the face of these sources of risk. The specialized literature has recognized the complexity of developing resilience in tourist destinations as a multivariable and context-specific concept. This has led to the development of various tourism resilience models that recognize different principles to achieve destination resilience. Under this perspective, resilience is seen as an outcome, and the proposed principles constitute the process by which resilience is built in tourist destinations. Thus, for the past decade, many studies have focused on understanding the construct and identified some principles that influence the resilience capacity of destinations.

Accordingly, for Berbés-Blázquez and Scott (2017), diversity, redundancy, connectivity, managing slow variables and feedback, experimentation and learning, participation, and polycentrism in governance are essential principles for constructing resilience. Diversity for Berbés-Blázquez and Scott translates into “not putting all your eggs in the same basket”; it is focused on diversifying tourism products, types of attractions, seasons of visits, or revenue streams. Although redundancy is linked to diversity, it is conceived as having components within a system with similar and overlapping functions. Connectivity is oriented toward the creation of links and networks at different levels. Managing slow change and feedback variables involves paying close attention to system changes, especially after interventions, to define positive or negative behaviors and identify slight changes. On the other hand, the principle of participation focuses on including various stakeholders in managing the destination as long as they adopt resilient and holistic thinking. Finally, polycentric governance refers to having various forms of government at different scales, avoiding the existence of a marked hierarchy and a top-down approach.

Similarly, Lew and Wu (2017) propose a resilience scale based on a matrix that contemplates two sides, on the one hand, the spatial scale of the hierarchy of systems and subsystems, and on the other, the change variables that go from slow drivers to fast drivers of change. Within this continuum, four dimensions were identified that will allow the strategic planning of resilience based on enhancing destination resources, governance strategies, system administration, and crisis planning.

Sheppard and Williams (2016) claims there are four determining factors to achieve socio-ecological resilience, derived from the factors proposed by Ruiz-Ballesteros in 2011. Thus, the determining factors in achieving resilience would be (1) learning to live with change and uncertainty, incorporating different types of learning and taking into account events that have affected systems in the past while developing adaptation strategies; (2) promoting diversity for reorganization and renewal by fostering ecological memory, the diversity of institutions in charge of responding in an emergency, creating a political space for experimentation and trust building to foster social memory in search of the innovation; (3) Combine different types of knowledge, especially the traditional one, while building capacity for environmental monitoring, inclusive participation, building institutions that provide guidelines to encourage capacity building at different scales; and (4) create opportunities for self-organization through strategies that promote the implementation of recovery strategies using the system's resources.

Lew and Wu (2017) stated that the resilience of tourist destinations is based on the management of the resources provided by the SES; thus, the strategies aimed at increasing the resilience of destinations should focus on ensuring the provision and regulation of cultural, natural and support services so that their quality is monetized. In this sense, Lew and Wu (2017) ensure that once the continuity of the resources provided by SES is prioritized, indicators of sustainability and resilience can be observed, such as economic development, community education, environmental education, proper management of resources environment, infrastructure, and health services.

Most tourism resilience studies acknowledge that change is constant, and the level of resilience determines how efficiently a system returns to a functional state after a significant impact, also known as the “new normal” (Herrera and Rodríguez, 2016). Strategies highlight three primary areas of adaptation: (1) technical adaptation strategies, (2) business management adaptation strategies, and (3) behavioral adaptation strategies. These strategies aim to increase the system's adaptation capacity and reduce the risk of future crises, ultimately improving the system's ability to respond efficiently and recover from a crisis (Basurto-Cedeño and Pennington-Gray, 2018).

Technical adaptation strategies are frequently called adopting new and traditional technologies to cope with changes that could risk the system's equilibrium. Several examples of technical adaptation are registered in the tourism resilience literature, including acquiring green technology to minimize gas emissions and water waste or implementing cooling equipment to cope with hot weather (Saarinen and Tervo, 2006).

Business management adaptation strategies in tourism include different administrative strategies applied by the managers of a destination or business owners to respond to change and avoid a decrease in visitors. Some of those tactics include marketing strategies, promotions, decreasing prices, etc., (Njoroge, 2015). Another adaptation strategy for businesses in the tourism industry is to focus on sustainability. With increasing environmental concerns, customers are becoming more conscious of the impact of tourism on the planet.

Research suggests that sustainability is an important factor in the decision-making process of tourists (Lee et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021). During the lockdown phase of the COVID pandemic, scholars met regularly and discussed the opportunity to relaunch tourism upon its reopening to include more sustainable practices and adopt capacity limits in an effort to slow the environmental and social impacts created by travel. Adapting behavior is commonly linked to tourists' actions, willingness to accept proposed strategies from destination managers and business owners and personal choices (Jopp et al., 2010).

Post-crisis behavioral adaptation is an important strategy for businesses to consider because it uses strategies focused on changing behaviors as a way to respond to the “new normal.” This involves understanding how consumer behavior has changed because of the pandemic and adapting business models and products accordingly. For example, many consumers have become more concerned about hygiene and safety, and businesses that can offer reassurance in these areas will likely be more successful. For example, the importance of keeping the infrastructure clean in places of recreation as well as communicating health and hygiene standards among tourists and staff were identified as determining factors for COVID-19 recovery, as well as the implementation of health policies and protocols (McCartney et al., 2021; Spenceley et al., 2021; Clark et al., 2022). Research has shown that businesses that are able to adapt to changes in consumer behavior are more likely to succeed in the post-pandemic landscape (Park et al., 2020).

Behavioral adaptation encompasses actions taken by stakeholders on the supply side, such as forming partnerships and alliances with diverse perspectives to enhance decision-making and recovery strategies (Njoroge, 2015; Xiao et al., 2020). However, these strategies are critical for outlining a path and vision of growth in the tourism sector. In this regard, the capacity to incorporate innovative management paradigms, particularly those with a multidisciplinary outlook, is vital for crisis planning and destination resilience. Unfortunately, post-crisis behavioral adaptation and supply-side strategies have received scant attention in the literature (Dawson et al., 2013).

Within tourism, prioritizing viewpoints from transdisciplinary sectors is critical to the destination's success in recovery as well as resilience; since tourism is a complex system, various elements that promote non-linear, interdependent relationships and represent different types of businesses and the community must be included in the planning and management of resilient tourism destinations. Hall (2018) and Hall et al. (2023); so that the intrinsic characteristics of the system elements are included, the relationship between these elements and the environment, and limits and values shared by the community are incorporated (Hall et al., 2017).

Hence, resilience planning must focus on garnering multiple perspectives and ideas, particularly in the response phase; this is important to the success of the response. Thus, using an ecological and social systems (SES) approach within the destination is one way to weave multiple views. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of human and natural systems' interdependence and the significance of managing these systems for sustainable tourism development. Effective resilience planning involves implementing strategies to reduce vulnerability, promote adaptation, and enhance the capacity of local communities and ecosystems to withstand and recover from shocks. Research suggests that a systems-based approach, such as the SES approach to crisis and resilience planning, can help ensure that tourism development is sustainable and resilient long-term (Scott and Gössling, 2021).

A systems-based approach recognizes that tourism is a complex system influenced by multiple factors, including the natural environment, social, economic, and political systems. Therefore, effective crisis management and resilience planning must consider these factors' interconnectedness and involve collaboration between multiple stakeholders from various sectors, geographies, industries, and political levels. A systems-based approach is integral to creating a crisis management plan which is comprehensive and extensive (Gössling et al., 2021; Scott and Gössling, 2021).

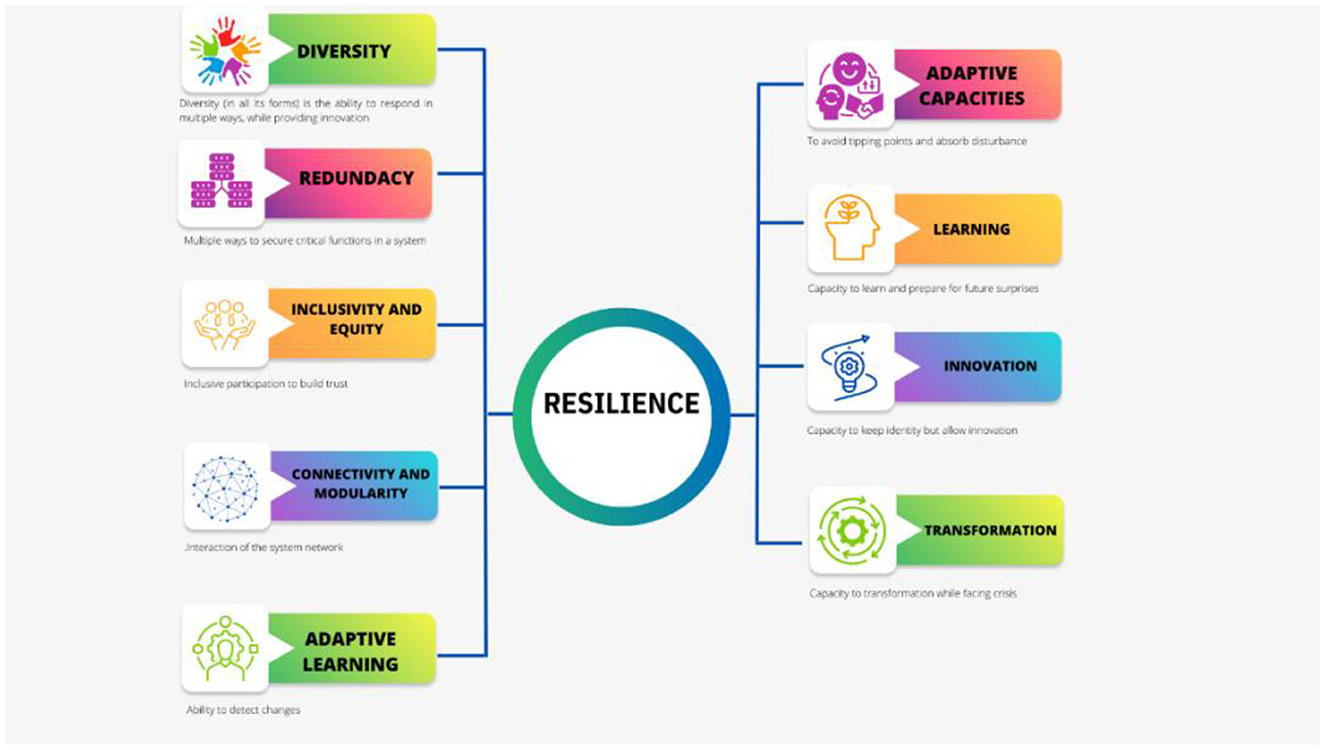

For Rockström et al. (2023), destination resilience needs to be studied from a systemic point of view, which incorporates integrating different stakeholders in managing the SES dimensions. Thus, resilience goes beyond the “bounced back” action and is recognized as the ability to live and develop by incorporating change and uncertainty and recognizing human hyperconnections. Human groups' interventions in managing the dimensions of the SES allow the construction of resilience and sustainability in a post-pandemic world with a changing landscape of risk, which increases due to the pressures of human activities on the planet. Under Rockström et al. (2023) framework, there are five resilience dimensions that need to be managed in destinations: diversity, redundancy, equity and inclusion, connectivity and modularity, and adaptive learning (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Resilience model based on Rockström et al. (2023) framework.

The management of these dimensions would lead to an increase in the levels of resilience of the SES, which in turn could be verified through (1) the development of adaptation capacities, (2) an increase in the capacity to learn from past events to prepare for future events, (3) innovation without losing identity, and (4) the capacity for transformation. Although the framework proposed by Rockström et al. (2023) is interdisciplinary, it adjusts very well to the realities of tourism systems, providing a framework with measurable variables. Thus, for Rockström et al. (2023), the dimension of diversity is measured with economic diversification, the use of renewable forms of energy, the systemic transformation of biomes to produce their resources, and the increase in forms of local food production. On the other hand, redundancy is measured through the creation of support networks that involve various stakeholders, especially those in a state of vulnerability, support for these networks to promote quality of life and better access to essential services, conservation, and sustainability of natural resources, the expansion of networks for access to economic credits, and maintaining resource reserves to be used in case of crisis. The dimension of inclusivity and equity is measured through the participation of minorities and various stakeholder groups, recognizing their contribution to the preservation of systemic services that contribute to the fight against climate change, ensuring that vulnerable groups and minorities are included in the processes of economic development, the fair distribution of wealth and taxes, and the creation of inclusive response and support networks. For its part, the dimension of connectivity and modularity is measured by promoting the use of local resources, such as local agricultural production, investment in technology and data analysis, decentralization of regional dependencies, and support for the solidification of networks of support and response with the inclusion of stakeholders from various disciplines. Finally, the adaptive learning dimension is measured by how agile are the decision-making processes in the face of change or crisis, the transformation of various institutions (public and private) and their predisposition to change and the adoption of non-traditional learning, and investment in research with continuous monitoring of the dimensions that allow quick actions to enhance the resilience of the system in the face of unpredictable changes and crises.

Community cohesion is formed through the creation of social capital to foster the establishment of networks, the adoption of collective norms, and the development of trust to promote the cooperation of social groups in the search for shared benefits, and whose typology includes the creation of ties (bonding), the inclusion of various groups including minorities and vulnerable populations (bridging) and participation in decision-making (linking) (Jewett et al., 2021). During crises, the strength of the community cohesion of destinations is tested since it constitutes the foundation of community resilience that does not depend on government aid (Tuckey et al., 2023). While different types of crises trigger different types of community response, studies show that resilience stemming from tighter community ties enables faster recovery processes (Berkes and Ross, 2013). In the case of natural disasters, community resilience provides conditions for risk management and accelerates response processes during crises. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, social relationships were severely affected due to the imposition of social distancing measures, which in many destinations made the recovery and resilience processes of communities even more challenging (Jewett et al., 2021).

Increasing community resilience is complex due to the intricate nature of people, communities, and their environments. Communities with stronger bonds tend to have more resilient industries after a disaster (Sydnor-Bousso, 2009). However, not all community organizations must prevail after a crisis for a destination to be considered resilient (Hall, 2016). According to Becken and Hughey (2013), resilience in tourist destinations involves strengthening solidity, assessing vulnerability, and improving the community's ability to adapt to adverse events, leveraging the construction of social capital.

In the framework of community resilience, Lew (2014) identifies four primary indicators: (1) improve the community's capacity to facilitate change when necessary, (2) integrate diverse perspectives to generate new environmental knowledge, (3) improve the living conditions of community members and employees of the tourism sector, and (4) encourage social collaboration. In a similar approach, Gabriel-Campos et al. (2021) evidence how the community resilience of small communities in Peru, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and natural disasters, is strengthened in the processes of creating social capital and collective identity rooted in customs, traditions, integration of ancestral knowledge and the search for the quality of life of the community.

For Sharifi (2016), the resilience of communities is achieved through the development of four skills: crisis planning, the ability to absorb shock, the efficiency of post-crisis recovery processes, and the ability to adapt while facing changes. Similarly, Cutter et al. (2008) mention that resilient communities can absorb the impact of disasters and crises, respond to threats by demonstrating flexibility and adaptation, reorganizing if necessary, and recovering from fast disasters. For their part, Hall (2018), mention that in order to be resilient, communities must be aware of their vulnerable points, prioritize development based on the benefit of all stakeholders, have long-term strategies in the face of crises, combat the fragmentation of traditional governance models, and operate at different scales. What is more for Carter (2022), community resilience is achieved when communities desire to help their members, act as a collective, and care about the wellbeing of their neighbors. In the recovery processes in the face of different crises, the support of the members of the community, as well as the construction of social capital, improves the response times and recovery processes of tourist destinations (Basurto-Cedeño, 2019), and the need of implementing frameworks that allow the development of social capital is paramount in the face of a landscape of risks that are increased by climate change, deforestation, increased human density, inequalities, among others (Rockström et al., 2023).

Effective crisis management planning is crucial for a destination's resilience in the tourism industry. Planning for crises is essential for Destination Management Organizations due to the vulnerability of destinations to various crises, such as natural disasters, pandemics, and terrorism (Pennington-Gray, 2018). Such plans require areas focusing on risk assessment, crisis response planning, communication strategies, and stakeholder engagement (Basurto-Cedeño and Pennington-Gray, 2018; Li et al., 2021).

To minimize the impact of crises, reduce recovery time, and maintain tourists' trust and confidence, it is crucial for destinations to develop and implement a crisis management plan. The involvement of relevant stakeholders, such as government agencies, tourism operators, and local communities, in the planning process is vital to ensure the plan's effective execution. Therefore, crisis management planning is integral to tourism planning and development.

According to a study by Chen (2016), destinations with a crisis management plan are better equipped to handle crises and recover quickly. The study suggests that involving multiple stakeholders in planning can lead to a more comprehensive and effective plan. Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of regular training and testing of the plan to ensure readiness in case of a crisis.

Stakeholder engagement is crucial for effective tourism crisis management. As Ackermann and Eden (2011) note, crises in the tourism industry can be complex and multifaceted and involves a range of stakeholders with diverse interests and perspectives. By involving these stakeholders in the crisis management process, it is possible to tap into their knowledge, expertise, and resources to develop effective solutions. Stakeholder engagement can help to build trust and strengthen relationships between stakeholders, which can be crucial for successful crisis management (Huang et al., 2019). In addition, involving stakeholders in crisis planning and response makes it possible to develop more comprehensive and effective strategies that consider the needs and concerns of all parties involved (Buda, 2020).

Effective stakeholder engagement in tourism crisis management requires a collaborative and inclusive approach. According to Gössling et al. (2013), this approach should involve engaging stakeholders at all stages of the crisis management process, from planning and preparation to response and recovery. This may involve establishing formal stakeholder committees, holding regular meetings and workshops, and engaging in open and transparent communication with stakeholders. By involving stakeholders in this way, it is possible to build a sense of ownership and shared responsibility for crisis management, which can help to ensure that solutions are effective and sustainable over the long term. Moreover, a study by Smith et al. (2020); found that effective stakeholder engagement can help organizations build trust with their stakeholders, positively impacting their reputation and mitigating the negative effects of a crisis. Additionally, by involving stakeholders in the crisis management process, organizations can develop more robust and inclusive solutions that address the concerns of all parties involved.

In addition, stakeholder engagement can facilitate effective communication during a crisis. According to a report by the Institute for Public Relations. (2021), clear and consistent communication is essential during a crisis to keep stakeholders informed and to prevent rumors and misinformation from spreading. By engaging stakeholders in the crisis management process, organizations can ensure that they have accurate and up-to-date information, which can help to prevent confusion and alleviate anxiety. Furthermore, stakeholders can advocate for the organization during a crisis, disseminating accurate information and dispelling rumors within their communities.

Although stakeholder engagement is crucial for effective crisis management in tourism destinations, several challenges can arise when engaging all relevant stakeholders. One significant challenge is identifying and involving all stakeholders, as there may be a vast number of stakeholders with varying interests and concerns. Consequently, it can be difficult to determine who needs to be involved in the planning process, leading to gaps in communication and coordination that can undermine the effectiveness of the crisis management plan.

Also, when striving for stakeholder engagement in crisis management planning in tourism destinations, challenges may arise from power imbalances among stakeholders, making it difficult to ensure two-way communication. In some cases, certain stakeholders may have more influence or resources than others, leading to their domination in the planning process while marginalizing or excluding others. This may result in a lack of cooperation and buy-in from some stakeholders, thus undermining the effectiveness of the crisis management plan. Additionally, stakeholders may have varying priorities and goals, which can make it challenging to reach a consensus on the crisis management plan. This can lead to delays in decision-making and coordination during the crisis. Identifying and addressing these challenges is crucial for successful stakeholder engagement and effective crisis management planning in tourism destinations.

Making sure that the voices of the main stakeholders of the destination are heard and not manipulated is not an easy task (Amore and Hall, 2022), especially in destinations where there are power struggles and practices of manipulation and exclusion (Hall and Jenkins, 2004; Calgaro et al., 2014). According to Marzano and Scott (2009), the lack of unity and collaboration between stakeholders, as well as unbalanced power dynamics and the use of authority to persuade, create conflicts in the decision-making of stakeholders in destination planning in Western societies, where there is an emphasis on the notions of individualism in terms of self-interest. It is complex, at best, to achieve inclusion processes and decision-making around community benefit. However, Presenza and Cipollina (2010) highlight the importance of developing support networks in creating partnerships between public and private actors and understanding the governance structures of tourism systems. They also stress the importance of seeking collaborative planning to avoid political conflicts, legitimize collective actions, promote the establishment of policies, and build trust. Undoubtedly, the inclusion of diverse stakeholders in the recovery processes is essential and should be aimed at providing heterogeneous points of view that allow taking into account the role of ecological systems and the impact of tourism actors in the modification of the tourism system (Calgaro et al., 2014); However, the predisposition of the stakeholders in the search for unity and collaboration should not be romanticized either (Hall and Jenkins, 2004).

Regardless of the challenges, stakeholder engagement is crucial to the crisis management planning process. As stated by Gössling et al. (2013), stakeholder engagement should involve engaging stakeholders at all stages of the crisis management process, from planning and preparation to response and recovery. Unfortunately, most models do not actively achieve this goal.

The stakeholder engagement continuum is a framework that describes the various levels of engagement that organizations can have with their stakeholders, from minimal involvement to high levels of collaboration. At one end of the continuum, organizations may simply inform their stakeholders about their decisions and actions, while at the other end, they may engage in collaborative decision-making with their stakeholders. According to Gray and Purdy (2018), the stakeholder engagement continuum provides a useful tool for organizations to evaluate their level of engagement with their stakeholders and identify opportunities for improvement.

The stakeholder engagement continuum has become an increasingly important concept in sustainability reporting and corporate social responsibility. Organizations that are committed to sustainable business practices recognize that they must engage with their stakeholders to understand their concerns and perspectives on environmental, social, and governance issues. According to Singh et al. (2022), stakeholder engagement can help organizations build trust, manage risk, and enhance their reputation. The stakeholder engagement continuum provides a useful framework for organizations to assess their stakeholder engagement practices and identify areas for improvement.

However, it is important to note that the stakeholder engagement continuum is not a one-size-fits-all approach. The appropriate level of engagement will depend on the nature of the organization, the issues at stake, and the stakeholders involved. According to Freeman (2010), stakeholder engagement should be tailored to each stakeholder group's specific needs and concerns. Organizations should also be prepared to adjust their engagement strategies as circumstances change. The stakeholder engagement continuum provides a useful starting point for organizations to evaluate their stakeholder engagement practices, but it should be used in conjunction with other tools and frameworks to ensure that engagement is effective and meaningful.

Stakeholder models within tourism management recognize that crisis management often does not include the appropriate level and range of stakeholders over the crises. A range of stakeholders, such as local communities, tourists, and government agencies, should be involved in the crisis management processes. Very few models exist which incorporate stakeholder collaboration into the tourism crisis management model. One model, however, is the Destination Disaster Management Network (DDMN), which was established in Australia to facilitate a coordinated response to crises in the tourism industry. The network involves collaboration among stakeholders, such as tourism businesses, government agencies, and emergency services, to ensure effective crisis management. It does not, however, include an outline of the level of engagement throughout the crisis phases.

Another framework, the Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction, and Management (CBDRRM) approach, emphasizes the importance of engaging local communities in disaster risk reduction and management processes. The approach involves working with communities to develop disaster risk reduction plans and build community resilience. Similarly, the Multi-Stakeholder Platform for Tourism Resilience (MSPTR) in Europe involves collaboration among stakeholders, such as tourism businesses, local communities, and government agencies, to develop and implement strategies for building tourism resilience.

Overall, the collaboration of stakeholders in the crisis management processes offers promising frameworks for managing crises in the tourism industry; however, to date, these models fail to reflect how they should coincide with the stages of the crisis and how strategies over these phases can be implemented to enhance and make the process more effective.

To enhance stakeholder engagement throughout the crisis management stages, several strategies can be employed. These strategies include (1) developing communication plans, (2) establishing collaborative networks, and (3) conducting ongoing engagement activities. Communication plans should be developed alongside stakeholders to ensure that all are informed about the crisis and involved in crisis management efforts. Effective communication is critical in managing crises and engaging stakeholders. Communication plans should be designed to be accessible to a range of stakeholders and provide information on the crisis, response efforts, and recovery processes (Kim and Lee, 2018).

Moreover, collaborative networks can facilitate the sharing of information and resources, which is crucial in managing crises. Networks can be established among tourism businesses, government agencies, and community organizations to ensure a coordinated response to crises. Collaborative networks can also facilitate the development of comprehensive crisis management plans and ensure that stakeholders are involved in the planning process (Faulkner et al., 2015).

In addition, conducting stakeholder engagement activities is another effective strategy to enhance stakeholder engagement. Stakeholder engagement activities can involve a range of stakeholders, including local communities, tourism businesses, and government agencies. Engagement activities can include public meetings, workshops, and consultation processes to ensure that stakeholders are involved in decision-making processes and that their perspectives are considered in crisis management efforts.

One example of the inclusion of stakeholder collaboration throughout the crisis phases is the Stakeholder Management Model (SMM), which recognizes the importance of stakeholder engagement throughout the tourism crisis management process. It emphasizes that all stakeholders should be involved in the crisis management process from the initial stages of planning to the post-crisis recovery phase. However, the Stakeholder Management Model (SMM) has some limitations with regard to the scope and depth of integration of stakeholders. One limitation is that the model may not fully capture the diversity and complexity of stakeholder interests and concerns during the planning stage. In practice, stakeholders may have competing or conflicting interests, and it can be challenging to identify and prioritize these interests in a way that is equitable and transparent. Another limitation of the SMM in crisis management planning is that it may not fully account for the changing nature of stakeholder relationships over time. As Ritchie and Jiang (2019) note, stakeholder relationships can be dynamic and may shift in response to changing circumstances or stakeholder actions. The SMM does not provide sufficient guidance for adapting to these changing relationships during the planning stage and makes assumptions that stakeholder interests and concerns remain static over time.

Furthermore, the SMM may not fully capture the importance of proactive communication and relationship-building with stakeholders during the planning stage. Effective crisis management requires building trust and credibility with stakeholders before a crisis occurs, which may involve engaging in ongoing communication and relationship-building activities (Huang et al., 2019). The SMM may not provide sufficient guidance for these proactive activities and may assume that stakeholder engagement is primarily reactive, occurring only after a crisis has occurred.

In addition to the SMM another modeled entitled, The Tourism Emergency Management Model (TEMM), emphasizes the need for collaboration and communication between stakeholders to effectively manage a crisis. The model highlights the importance of establishing a central emergency response team that includes representatives from all relevant stakeholders, including tourism operators, government agencies, and the local community. This group works together to coordinate the response to the crisis, including information sharing, resource allocation, and decision-making. However, the Tourism Emergency Management Model (TEMM) has some limitations. One limitation is that the model may not fully account for the diversity of stakeholder perspectives and interests during the planning stage. As Faulkner and Vikulov (2001) note, tourism stakeholders may have different priorities and expectations in relation to crisis management, and it can be challenging to identify and prioritize these interests in a way that is equitable and transparent. The TEMM may not fully account for the importance of community involvement and participation in crisis management planning. As Huh and Kim (2017) note, community involvement is critical for effective crisis management, particularly in the planning stage, as it can help to build trust and facilitate communication between stakeholders.

Finally, the TEMM may not provide sufficient guidance for engaging with local communities and other stakeholders during the planning stage, and may assume that crisis management planning can be carried out solely by tourism industry professionals. Thus, this model tends to emphasis community involvement not a robust view of stakeholder groups.

A third crisis management model that incorporates stakeholders is the Crisis Management Life Cycle Model (CMLCM). The model outlines five stages of the crisis management process: pre-crisis, crisis recognition, crisis response, post-crisis, and recovery. At each stage, the model suggests involving different stakeholders, including destination managers, tourism operators, visitors, and the media. The CMLCM recognizes that the involvement of all relevant stakeholders is critical to the success of the crisis management process and the speedy recovery of the destination. The Crisis Management Life Cycle Model (CMLCM) is a commonly used framework for understanding the stages of a crisis and the actions that can be taken to manage it effectively. While this model can be useful in guiding crisis response efforts, it does have some limitations. Mainly, while stakeholder engagement is recognized as an important aspect of crisis management in the CMLCM, it is not always clear how this is done in practice. The model does not provide detailed guidance on how to engage stakeholders effectively or how to prioritize their needs and concerns.

Despite this attention to the involvement of stakeholders in the crisis planning models (Ritchie, 2004), it is perplexing that studies have not fully integrated the management and engagement of stakeholders from a variety of backgrounds into all phases of the crisis. Specifically, crisis management planning models have not called out stakeholder management as a specific, explicit, unique area within the tourism crisis management plan.

Previous works from Pennington-Gray et al. (2014), which have highlighted the Tourism Area Response Network (TARN), provide a launching pad for how stakeholder groups can be incorporated, financed, managed and maintained at various phases of the crisis. Thus, similar to “crisis communications,” it argued that “tourism collaborations and stakeholder management” should be its own sub-category within the crisis management plan which occurs at within all phases of the crisis (see Figure 2).

As an extension of the Tourism Area Response Network, a more robust model which highlights stakeholder engagement from a wider variety of sectors is proposed. There is a lack of research in non-traditional collaborations in tourism crisis management. One of the reasons for this gap in the literature is that traditionally the study of stakeholders in the tourism field has focused excessively on analyzing ways of involving critical stakeholders within the tourism sector (Clark et al., 2022); however, due to the characteristics of the tourism system, which equilibrium is affected by changes that come from outside the sector, it is necessary to broaden the range of research giving importance to the integration of non-traditional stakeholders in the planning and decision-making processes, especially when seeking to improve the resilience of destinations. Furthermore, this lack of research is a hindrance to understanding the scope and depth of the effectiveness of responses during a crisis. Non-traditional collaborations involve civil society groups, academic institutions, and community-based organizations outside the tourism industry. Research has shown that non-traditional collaborations can enhance crisis management through their expertise, tangential knowledge, and community networks (Buckley, 2012; Kim and Lee, 2018). In the context of tourism, non-traditional collaborations could involve collaborations with environmental scientists, emergency management, and health care providers, scientists, and others who bring unique perspectives and resources to tourism crisis management. Therefore, fostering non-traditional collaborations in tourism crisis management is important for building resilience and ensuring effective responses to crises.

Ongoing collaboration between the tourism industry and non-traditional partners can build trust and facilitate a more coordinated response to crises. Joint research initiatives are one way to achieve this. Collaborative research projects, funding for graduate students or post-doctoral fellows, and sharing data and expertise are all examples of how joint research can facilitate collaboration. Collaboration in research can be observed in the development of early warning systems for potential health risks. By collaborating, tourism organizations and healthcare organizations can create and execute monitoring systems to identify possible health risks promptly, decreasing the spread of diseases and avoiding potential crises. According to a study conducted by Wen et al. (2021), such collaborations have proven to be effective in managing the outbreak of diseases in various settings. These initiatives can help identify new approaches and strategies for managing potential crises. Research conducted by Weaver and Pforr (2014) on crisis management in the tourism industry emphasizes the importance of such collaborations in improving crisis management practices.

Developing formal agreements or protocols between tourism organizations and non-traditional stakeholders is a key strategy for establishing collaboration in the tourism industry. These agreements can outline roles and responsibilities, establish communication channels, and promote information sharing, which can help manage risks and mitigate crises. The tourism industry faces a wide range of risks, and by working together, stakeholders can better understand these risks and develop more effective crisis management plans.

The purpose of this study is to examine the collaboration techniques used in the case of El Balsamo, Ecuador and provide examples of how a new more comprehensive model of integrated collaboration can be developed which centers on both traditional and non-traditional stakeholders.

The bio corridor of the Cordillera del Balsamo is located in the province of Manabí, Ecuador (Figures 3, 4) in the village of Sucre. It is bordered to the south by the estuary “La Boca of the Portoviejo,” the Rocafuerte wetlands, and the Portoviejo Valley. To the north are the city of Bahía de Caráquez and the estuary of the Chone River.

El Balsamo comprises twelve private properties and a publicly owned buffer zone. The owners of private properties or “property owners” are also called “reservists.” Due to their own free will, they decided to create a foundation called the Cerro Seco ONG. The goal was to work together to preserve the native vegetation and fauna of their properties, leaving aside unsustainable economic activities such as monoculture agriculture.

The reservists started the “El Balsamo” project in 1991, researched the area's natural and cultural resources, and argued the dry forest's importance before the Corporation of National Forests and Private Reserves of Ecuador, becoming members of this institution on 26 September 1994. Since then, the reservists have worked on the ecological value and properties of the area and received the AICAs declaration (Areas of Importance for the Conservation of Birds by its acronym in Spanish) by Birdlife International in 2003 and the category of Bio-corridors by the World Environmental Fund of the United Nations in 2018.

After being recognized as a Biocorridor, the reservists requested the support of the Provincial Government for the declaration of the set of private properties and the surrounding areas as a Conservation Area Provincial in 2018. Currently, each private property within the El Balsamo nature reserve receives the name “reserve” (Table 1) and is managed at the will of its owners following the sustainability parameters of the Cerro Seco Association and the Provincial Government.

Cordillera El Balsamo is one of the last remnants of equatorial dry forest in the area, protected by the owners of the reserves that are part of the Cerro Seco ONG. Up to the request of the reservists, the public sector has intervened on the land, they have has created and implemented policies for the preservation of local fauna and flora, as well as established sanctions for activities that are not allowed, such as using toxic pesticides; ensuring this way the sustainability of the natural resources, the quality of life of the communities, and the regulation of economic activities in the area and its surroundings.

El Balsamo includes 8,879.85 hectares of dry forest and a buffer zone of 2,566.93 hectares connected to the Santa Teresa rice paddies, the mangroves of the Portoviejo River, and the salt mines. Its location between the estuaries and the geographical proximity to the ocean has turned it into a sanctuary for migratory birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. However, the last decade of urban development, the expansion of dragon fruit monoculture, the pollution of the ocean, natural disasters, the erosion of the land, the climate change, among others, have put the destination's resources, and the quality of the tourists' experience at risk.

Hospitality and tourism are part of the allowed activities as long as they are carried out sustainably and do not endanger the delicate ecosystem of the reserves. Tourism planning and promotion is in charge of the Cerro Seco NGO, and the decision-making process regarding the tourist development of El Balsamo is done by consensus among all the reservists, prioritizing the sustainability of natural resources. In general, the primary constraint faced is raising funds to promote, preserve, and improve the infrastructure to attract more tourists. In the past, the association has resorted to international funds and self-financing for tourism promotion.

Due to its geographical characteristics, the Cordillera El Balsamo conservation area has a great biodiversity of flora and fauna, making it an ideal place for studying native and migratory species. The areas surrounding the reserve, specifically the mangroves of La Boca and the salt mines, allow observation of more than one hundred species of birds in a 1-hour visit. According to the Prefecture of Manabí (2021), 99 different species of plants were found in the reserves, including four endemics to the region; 101 species of birds were recorded, 29 species of amphibians, 29 species of mammals, and 35 species of insects.

The state of conservation of the natural resource is strong because the owners of the reserves have allowed the forest to recover from previous agricultural activities. Tourism and hospitality activities have been carried out in El Balsamo since 1996 (Figure 4), especially in the Cerro Seco Reserve; these activities were considered as a secondary income for a long time, and non-abrasive polyculture agriculture was prioritized (Prefectura de Manabí, 2021), with only seven reserves prioritizing tourism activities as their primary source of income.

Since 2010, the improvement of road access has resulted in the income of owners of the reserves' quadrupling from 14,000 USD to 55,000 USD per year in a length of 5 years, from 2010 to 2014 (Prefectura de Manabi., 2021). This aroused the interest of other reservists, making tourism an important activity for Cerro Seco NGO. The possibility of expanding the tourist offer, improving infrastructure, incorporating traditional polyculture agriculture as a crucial part of tourism promotion, training, and the inclusion of the community and other reservists was prioritized by Cerro Seco NGO in 2018; however, the COVID-19 pandemic became detrimental to the implementation of tourism development strategies initially proposed.

According to the Prefecture of Manabi (Prefectura de Manabi., 2021), El Balsamo was in a stage of initial tourism growth, attracting tourists considered as explorers when the pandemic commenced. Most of the tourists visiting the region were primarily people between the ages of 26 and 45 years (66.63%), without mobility or health problems (66.67%), from the United States (16.67%), Europe (45.84%), and the Ecuadorian Andes region (25%). Additionally, 44.4% were undergrad and grad university students conducting research, 29.63% traveling with friends or family without kids under 12, 7.41% travel with kids under 12, 3.7% travel alone, and 14.86% part of an organized tour group. The main reasons for visitation were (1) to conduct research 44.4%, (2) for bird watching 28.21%, and (3) for beach leisure activities 27.39%.

Since El Balsamo is visited mainly by foreign tourists, the mobility restrictions imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic significantly decreased tourism revenue. The reservists reported no visitors from March to September 2020 (Prefectura de Manabi., 2021), and 62% of the businesses associated with tourism in the Sucre canton were lost.

Of the seven reservists engaged in tourist activities, only two reported income from tourism, totaling USD 5,000 in 2020. The lack of visitors also affected the trails, allowing overgrowth in these spaces and increasing maintenance costs for reserve owners. Similarly, increased criminal acts were reported in unoccupied accommodation properties during lockdown periods (Prefectura de Manabi., 2021).

While the impact of COVID-19 on El Balsamo tourism was devastating, similar effects were seen throughout the Manabi province. For example, Manta, the biggest city in the province, reported monthly losses of 1.6 million dollars from March to August 2020 (Felix-Mendoza and Reinoso, 2020), and more than 30% of the registered tourism businesses were declared bankrupt (Basurto and Basurto, 2021). It is also important to acknowledge that many of the challenges experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic in the destination under study are areas of growing interest in the tourism field and the resilience literature.

A case study approach was adopted. A case study is a research strategy that includes an empirical collection of data regarding a specific phenomenon, having a real-life example as a context, using different sources of evidence (Flyvbjerg, 2011), allowing to explore the particularities of the specific case, but also export generalization for other context and generating theoretical and practical contributions (Feagin et al., 2016). Using a qualitative case study acknowledges the participants' voices and describes the nature of the case, recognizing other aspects of the social context through narratives (Thomas, 2021).

The case study methodology is based on its ability to provide rich and in-depth information on a complex phenomenon while providing a real context without neglecting a holistic understanding (Flyvbjerg, 2011). Thus, case studies emphasize the importance of the uniqueness of the contexts while allowing the identification of conditions that can be applied to other destinations (Feagin et al., 2016). Additionally, they include multiple intrinsic issues, characteristics of the context, unique circumstances, and the social, cultural, and environmental dynamics that shape destinations that cannot be covered in quantitative studies (Hartley, 2004). Case studies acknowledge the analysis of a phenomenon's intricate relationships, processes, and results. In the same way, they provide a starting point to incorporate new perspectives in developing new models or updating frameworks that, due to external factors, might not be longer adequate (Gerring, 2004). Many of the models used to understand the recovery processes and crisis management do not fit rural community tourist destinations, even less in the face of economic, sociological, and cultural change that the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it. The case study methodology incorporates empirical evidence to generate new theoretical perspectives based on destination recovery processes. Although the limitation of the case studies revolves around the impossibility of generalizing the results due to the possibility of subjectivity, it does allow the identification of situations that may apply to destinations with similar characteristics.

Primary data for this study were generated through interviews from January to August 2021 (Figure 5). The population of interest was the owners of private properties (or reservists) located within El Balsamo and the government authorities of Sucre DMO and the Prefecture of Manabí. The population of interest was chosen because they were the competent stakeholders in decision-making regarding tourism development in El Balsamo. A total of 23 interviews were conducted at the destination and included the 12 reserve owners, one Sucre DMO member, four Prefecture members, and six union representatives of the communities in the buffer zone.

Interviews were conducted over seven months (from January to August 2021) and accommodated the interviewees' availability. When the interviews were conducted, the National Government of Ecuador imposed mandatory curfews on three occasions due to the increase in COVID-19 cases in the region; therefore, the places and dates of data collection were postponed by a few months, contributing to a lengthened time for data collection.

In-person interviews lasted an average of 1 hour and were usually conducted at their place of work. The saturation point was reached in interview 15; however, the researchers decided to continue with the other eight scheduled interviews to ensure the involvement of all the actors and avoid omissions. During the interviews, participants brainstormed opportunities arising from unexpected change, shared past experiences when dealing with crises, and explored new adaptive and recovery strategies like creating new partnerships. The information collected was recorded through note logs, photo albums, and audio recordings.

To analyze the narrative and with the aim to reduce the interpretation bias, the researchers used the MERITS Plus Model as a conceptual framework for systematic analysis of narrative data through sequential analysis (Gregory, 2020). The MERITS Plus Model revealed the thematic and linguistic trends in the data providing structure but also flexibility to identify the what, the how, and the why of the adoption of different strategies for recovery in the destination (Gregory, 2020). The MERITS Plus Model helped to “capture voices of participants through their narratives, finding a balance between the fidelity of the words while examining the significance of the narratives within the wider context” (Gregory, 2020, p. 137). The MERITS Plus Model provided a multilayered approach, with two linguistic analyses to go beyond coding, allowing the possibility of analyzing the language choices to display cultural or social affiliation and supporting the findings. The MERITS model employs six phases and three themes to guide the analysis. These themes were converted to three questions:

1. Is there a link between collaborators and goals/objectives of the outcome of the partnership?

2. What was learned to aid in recovery with future crisis?

3. How can this collaboration transition to the future? How is it enduring?

The results revealed three themes that supported the development of the new model, SCTCMM. Furthermore, the MERITS model consisted of six phases incorporating the intentions and motivations of stakeholder participation in the decision-making process. The first phase analyzed the motivation of the participants. For this study, the reasons why the stakeholders decided to participate in the Balsamo tourism sector's recovery process were considered. The second phase focused on knowing the participants' expectations and their preconceived ideas regarding the phenomenon of analysis. The Realty phase focused on analyzing how participation in the decision-making processes fulfilled the expectations and preconceived ideas prior to participation.

On the other hand, the Identity process covered how the stakeholders perceived themselves as actors who contributed to the destiny recovery processes. The transition phase was oriented on how participation and sharing with actors from various sectors prepared them to transition to position themselves as priority actors in the tourism recovery processes. Finally, the stories and synthesis phase focused on carrying out the narrative processes of the experience in the interviews conducted.

El Balsamo is a community that has geographically benefited from natural resources of high biological value. However, this reality is only generalizable to some rural tourist destinations; some commonalities can be identified by analyzing the information collected. Like many rural tourist destinations in developing countries, El Balsamo needs more economic resources to recover after a crisis rapidly and leverages social resources to implement adaptation strategies. The importance of support networks and the inclusion of stakeholders in different areas and disciplines was evidenced in the interviews and is aligned with the findings of Presenza and Cipollina (2010) regarding the importance of creating networks and partnerships in recovery and resilience.

The strategies applied in the Balsamo in the face of the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic were linked to the characteristics of the destination, as well as its limitations in terms of the availability of economic resources:

“Although our community does not have money, as in other destinations, we care about of each other, and we look after the wellbeing of our people and the environment that we love, so when no one came here, due to all the restrictions of mobility that they gave us, we had to see how we convinced the health sector that our tourism businesses were not going to worsen the situation, we had to ally ourselves and open the eyes of the people who make the decisions (Cerro Seco ONG member).”

In the same way, the enhancement of the natural resources of the sector prioritized strategies that did not go against the environmental and social values that have been developed among the reservists in the last decades:

“It is difficult to tell someone not to do so, do not plant monocultures when you do not have a way to eat if the basic needs of the community are not ensured, you cannot expect the preservation of resources, people will do whatever it takes to recover even if those decisions are not the best in the long term, that is why we united, created these networks, made ourselves heard and allied with the “big shots” to ensure the wellbeing of all and develop strategies of adaptation in favor of all, including the environment (Cerro Seco ONG member).”

It is important to point out that although the valuation of natural resources is a factor that supports the resilience processes of destinations (Calgaro et al., 2014), not all rural tourist communities are aware of their importance in the development of diversity as a contributing element in the development of resilience; however, in the case of the Balsamo, the reservists were aware of the role that the environment plays:

“We are part of this nature, and this is how it teaches us how to recover; in this pandemic, these forests have helped us to continue receiving people without putting ourselves in danger because the forest heals us (Cerro Seco ONG member).”

“We have allowed the forest to recover, and now when there are earthquakes, the roots of the trees prevent landslides and loss of infrastructure… these open trails full of oxygen have allowed people to come and realize the healing power of the forest, this biodiversity of plants allowed to change the point of view of health professionals (Cerro Seco ONG member).”

Furthermore, within the data analyzed based on the use of the MERITS model combined with key strategies for successful collaborations, three main themes emerged. The themes were: (1) communication plans; (2) collaborative networks; and (3) stakeholder engagement activities over time.

Developing communication plans with stakeholders during crisis planning, establishing collaborative networks, and engaging with all stakeholders over time are three critical components of effective crisis management (Presenza and Cipollina, 2010). Collaborative networks include key stakeholders from a variety of sectors, such as government agencies, private sector organizations, and community groups. These networks can help to identify potential risks and develop effective solutions to address them. Developing communication plans that are tailored to the needs and concerns of different stakeholders can enhance trust and build support for crisis management efforts. Engaging with stakeholders over time through ongoing communication and collaboration can also help to build relationships and foster long-term solutions to prevent future crises (Jewett et al., 2021). Ultimately, creating effective networks and communication plans can help organizations to manage crises effectively, minimize harm to individuals and communities, and build resilience.

The response phase of the crisis was characterized by imposed control measures, limiting mobility within the province of Manabí and closing the borders for commercial flights. From January to March 2021, although signs of tourism reactivation began to be evidenced, measures that affected the tourism sector in the area continued. The use of masks in closed public spaces and outdoors was declared mandatory, and 75% of the capacity of tourism, hospitality, and restaurant establishments was restricted while also imposing the complete closure of places that sell alcoholic beverages. The congregation of more than 25 people in closed spaces was not allowed, and pedestrian and vehicle mobility was only allowed from 5 am to 10 pm. During April, due to the surge in cases of COVID-19 and the health system's collapse, the restrictions were increased, closing the beaches during the weekends and restricting access after 5 pm on Mondays to Fridays. The capacity in restaurants, hotels, and places of recreation was limited to 25% of the maximum capacity, and pedestrian and vehicular circulation was prohibited from 9 at night to 5 in the morning.

Due to the harsh measures imposed by the COE and given the affectation of income from tourists, the Cerro Seco NGO reservists decided to coordinate with the DMO of Sucre and the Prefecture of the Provincial Government of Manabí in developing recovery strategies for El Balsamo tourist sector.

Cerro Seco NGO and the tourism stakeholders of the Bahia de Caraquez area in the Sucre Canton of the Manabí province traditionally centralized communication during and after the crisis through official announcements of the tourism department Decentralized Administrative Government (GAD) of Sucre or the Provincial Governments. In general, crisis communication was reactive rather than proactive. Although this form of communication provided a certain sense of tranquility among tourists and visitors, its effectiveness for crisis control, although it has not been quantified in previous studies, was perceived among the members of Cerro Seco ONG as ineffective and biased even before the COVID-19 pandemic “In my reserve we carry out different accommodation activities and social events, since my family is from the mountains, many of my clients come from this area and from abroad; having a property facing the sea, there are times when due to ignorance or to create alarm, the news maximizes normal situations, and that impacts the perception of safety in my cabins and reduces the number of tourists that come to stay with us... for example, aguajes are very normal occurrences that happen periodically due to the sea currents, leading bigger waves, for which reason some caution is required among bathers, but under no circumstances it is comparable to a tsunami as the press wants to sell it, and just before a holiday. But what do we do to counteract this? most of the time, the GAD of Sucre sends an official statement after the holiday clarifying that there is no great danger, but we have already lost the holiday (Cerro Seco ONG member).”

Moreover, reservists perceived that the inefficiency of the communication in response to the crisis was due to the lack of partnerships with a depth of both traditional and non-traditional stakeholders “When the 2016 earthquake happened, everyone was scared, and it was understandable it was a terrible event, but here at Balsamo we were ready to continue operating within a couple of weeks after the earthquake, but nobody knew. We did not have links with the media to communicate this (Cerro Seco ONG member).”

Based on previous experiences and as a response to COVID-19, as soon as mobility restrictions were lifted, the reservists prioritized the creation of alliances that would enable collaborative communication to be established, integrating various sectors to be able to convey the message that visiting El Balsamo was safe was a first step. Thus, they worked with multiple sectors, prioritizing the health sector, cantonal COE, and Provincial Government members, and organized field trips on the routes and other tourist attractions. The improvement of the communication aimed to build networks and trust aligns with previous research on the resilience field and the importance of connectivity and modularity to foster resilience (Rockström et al., 2023; Tuckey et al., 2023).

The form of internal communication (among the stakeholders) was handled informally by creating a WhatsApp group, which allowed rapid communication between the group members. However, for external communications, formal channels such as the local press were ranked first priority (Figure 6).

The integration of various stakeholders permitted a holistic message construction process since various stakeholders had different priorities that needed to be included in one message (Tuckey et al., 2023). For example, the members of Cerro Seco NGO prioritized the reactivation of tourism and the increase in the number of visitors, while the stakeholders of the health sector had as a priority the reduction of the number of hospitalized by COVID-19, and the increase of tourists perceived as a trigger for the increase of COVID-19 cases. The integration of the stakeholders allowed for a unified message. “It has been interesting to see how, despite our differences, we have learned to find an intermediate point that benefits us all (Member of the prefecture).”

Although collaborative communication made it possible to address the impact of COVID-19, the partnerships have continued into Post COVID-19 times. Based on the latest interviews, the collaborative work between the Prefecture, Cerro Seco NGO, and health professionals has been maintained and has allowed a continued response to crises in the areas of infectious diseases, such as Dengue. The reservists created a new messaging strategy which included using natural repellents, based on palo santo, as part of the Dengue prevention processes. This messaging strategy was based on the recommendations of professionals in the health sector and included science-based information based on content created by the experts.

Based on one of the first collaborative activities, links were created with different traditional and non-traditional sectors of Sucre to communicate the effects of the impacts of COVID on the tourism sector and, subsequently the economy of the community. This informal linkage led to a more formal agreement. The new partnership was called Cerro Seco NGO (Figure 7). The objective of this partnership was to create a long-term agreement based on science in the health sector to mitigate risk and respond to health crises. The long-term goal was to drive information to mitigate risk in such a ways for the visitor to engage in protective behaviors so as to decrease risk and maintain the sustainability of EL Balsamo. This type of alliances created from COVID-19 and that continue in a post-pandemic reality to strengthen the processes of building trust and developing empowerment are consistent with the findings of Tuckey et al. (2023) about the importance of the development of networks and long-term partnerships in the processes of the resilience of destinations.

Figure 7. Meeting with Stakeholder Manabi. Manabí controla casos de covid y reactiva el turismo - El Comercio.

Early in the lockdown, the particularities of the contagion by COVID-19 were unknown. The new partnership, Cerro Seco NGO, addressed concerns with participation in activities in the park. First, a carrying capacity based on risk was determined. The partnership agreed to decrease the number of people per group on the trails but increase the number of times a participant could use the trail. In addition, participants were encouraged to use masks (even outdoors), social distance themselves and use sanitation stations. Cerro Seco NGO agreed to work together toward early warning systems that provided early notification of signs of early outbreaks of diseases which were used to aid in the immediate planning of El Balsamo. They also agreed to work collaboratively to manage future outbreaks of a wider range of diseases, such as Chikungunya and Dengue.

Moreover, Cerro Seco NGO prioritized implementing risk management plans. They requested the Government of the Provincial Prefecture of Manabí to prioritize training and the development of planning tools as a priority rather than invest in infrastructure implementation. The El Balsamo managers argued that being located on a geological fault, the destination was not only susceptible to the effects of COVID-19 but also to earthquakes, landslides, floods due to El Niño phenomena, forest fires resulting from droughts due to the La Niña phenomenon, etc., therefore, continuous monitoring of internal and external factors that could lead to a crisis was critical, including the experts from different fields, such as soil study engineers, and integration of ancestral knowledge.

The need to develop collaborative strategies stemmed from the awareness of the impact that health professionals had on decision-making in El Balsamo. “They understood the importance of tourist activity for the conservation of this beauty of nature, and how it contributes to our economy and without causing harm to anyone (Cerro Seco ONG member).”