- 1School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Lima, Peru

- 2Business and Construction Department, Melbourne Polytechnic, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Between 2015 to 2019, Peru became the second biggest host community for displaced Venezuelans, and 4 out 5 chose the capital, Lima, as their destination. While the majority of migrants found jobs in the tourism and hospitality industries, only a minority were employed in the regulated sector of tourism and hospitality, with the majority finding employment in what is considered the unregulated sector. This study presents an analysis on the role of regulated travel agencies in the process of the social and economic integration of Venezuelan migrants in the host country. A qualitative method was employed with in-depth interviews to migrants, migration experts and formal employers in the tourism sector. A total of 12 interviews took place during June to November 2020. It should be noted that the study took place during lockdowns so the sample size is relatively small due to the closure of travel agencies and the challenges on identifying participants. Findings indicate that regulated travel agencies represent a good medium for the integration of Venezuelan migrants as they create professional opportunities for skilled professionals and promote safe multicultural spaces that foster social integration. However, challenges were also recognized as migrants tend to be overqualified for the roles they performed and are also faced with gender inequality and other forms of discrimination by local society. This study proposed that given their professional qualifications Venezuelan migrants have the potential to contribute in the recovery of the tourism sector particularly after the pandemic. However, current unwieldy migration policies may deter them to reach job opportunities in the sector.

1. Introduction

The world today faces an array of challenges and pressures that cause humans to migrate in search of better life circumstances for themselves and their loved ones. To name a few, in different parts of the world, countries face conflict, war, strong effects of climate change, political instability, economic crises, which lead to surges in migration along certain corridors, and pressure on host countries may lack policies in place designed to receive and integrate this influx of migrants. These challenges, and their impact on human mobility across borders, may well continue into the next decades. In this vein, this paper's focus is on Peru as a case study, as the second largest host country for Venezuelan migrants in the world (after Colombia), and aims to understand the potential of the regulated tourism industry—one of the main economic activities in the country—to integrate Venezuelan professionals into the workforce.

Driven by the challenging economic and socio-political conditions affecting Venezuela in the last decades, by the end of 2019 approximately 4.5 million of people had left as migrants, refugees or asylum seekers (ACNUR OIM, 2020). Between 2015 and 2019, Peru became the world's second largest host country for these migrants. Within Peru, the capital city of Lima hosts 4 out of 5 displaced Venezuelans (ACNUR OIM, 2020). Within this context, 92% of Venezuelans living in Peru are the main source of economic support for their families back home and 95% of them consider Peru as the final destination in their migration trajectory (INEI, 2018). Previous studies have suggested that the majority of Venezuelans currently work in hotels, restaurants, transportation and construction, however, only 6% of them are in the regulated sector (World Bank, 2020) given 80% of Peru's economy is unregulated (MEF, 2021).

This increased and steady influx of migrants along the Venezuela-Peru corridor has been the subject of studies in Peruvian academia including its pressure on public health (Figueroa et al., 2019; Mendoza and Miranda, 2019; Carroll et al., 2020), national policies from the part of government in response migration (Koechlin et al., 2018; Acosta et al., 2019; Cárdenas et al., 2020; Freier and Castillo, 2020; Gissi et al., 2020; Costa, 2021), integration into the workforce and its challenges (Rojas and Monterroso, 2019; Condori et al., 2020; Lovón Cueva, 2021), social integration and the rise of xenophobia among locals (Freier and Castillo, 2020; Loayza, 2020; Robinson and Espinosa, 2021) and education (Rocha, 2020). Yet, no previous research has focused on the potential of the tourism sector as a platform to integrate these migrants into the workforce. This becomes particularly relevant as tourism is one of the main industries in Peru with a contribution to 3.9% of the GDP (pre COVID) and currently 2.5% of the GDP (MINCETUR, 2022) and 4.4 million visitors in 2019 (MINCETUR, 2020).

Thus, this study sought to analyse on how travel agencies could contribute to the integration of Venezuelan professionals into the regulated tourism sector. The objectives were to explore the type of jobs covered by Venezuelans working in regulated travel agencies in Lima; to define the potential limitations to those roles in terms of their economic and social integration; and, to identify opportunities and examples of best practice within travel agencies with the potential to assist migrants' integration into their host community. Although the majority of Venezuelan migrants were currently working in unregulated jobs during the period of study (World Bank, 2020), this paper seeks insights with regards to the integration of Venezuelan migrants within the 6% which did attain regulated employment in the tourism sector.

This study uses the conceptualization of integration as “a two-way process” in which migrants achieve a sense of belonging and a level of agency similar to that of the local population. In this sense, fully integrated migrants are accepted by the host community without social barriers that draw a separation between insiders—legitimate members—and outsiders—non-legitimate members (Klarenbeek, 2019). Considering that Peru is a multiethnic and multicultural country, integration is considered from the perspective of multiculturalism, namely that migrants can attain a sense of belonging while maintaining their own identities and cultural traits (Castles et al., 2014). For this study, economic integration is measured by the following criteria: possibilities to achieve professional growth, easiness to save money, and perceptions of work culture. In terms of social integration, it is measured by possibilities of personal mobilization, family ties within the country and potential for family reunification, long-term opportunities, perceptions of discrimination and xenophobia, importance of support networks and personal identity (Rudiger and Spencer, 2003).

The present study took place in 2020 to analyze the period between 2015 to 2019, when the Peruvian government enacted a series of policies in response to the surge in Venezuelan migration. Between January 2018 and June 2019, President Kuczynski implemented the temporary stay permit license (PTP, for its Spanish acronym). This policy allowed Venezuelans to regularize their migratory status, granting them access to the regulated labor market and services including health, banking and education. Moreover, it also acted as a potential pathway for permanent residency. This policy was a decisive factor in attracting a high number of Venezuelans to Peru (International Bank for Reconstruction Development, 2019). However, such policies were reverted by the next administration under President Vizcarra, who introduced stricter requirements for Venezuelans to enter Peru, specifically valid passports (not formerly required), criminal records and humanitarian visas emitted in Caracas, Venezuela (Pariahuamán et al., 2020). These requirements have resulted in many Venezuelans being unable to regularize their status, therefore pushing them to seek unregulated, low-income jobs with a higher risk of exploitative working conditions and, in consequence, hindering their economic inclusion (Guerrero et al., 2020). Furthermore, as the migrant population grew, local in the host community began to display resistance and at times rejection toward Venezuelans. This led to a series of violent incidents between locals and migrants (RPP, 2019). To exacerbate the precarious situation of Venezuelans in Peru, the Covid-19 pandemic crisis further complicated their economic and social status (Mixed Migration Centre, 2020).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Intersection between tourism and migration

Previous studies have identified tourism as an industry with low entry barriers, attracting migrants in search of jobs (Filimonau and Mika, 2019). Around the world, migration has also had a positive, direct impact on the tourism and hospitality industries through contribution to the labor markets and entrepreneurial ventures (Tillbert and Heldt, 2019) as well as indirect impacts through diaspora tourism (Reed, 2013). Migrant workers are considered an important source of labor in the tourism industry as they tend to accept lower pay rates in relation to the local labor market (ILO, 2012). In some cases, migrant workers can cover shortages in particular sectors especially among seasonal jobs (Joppe, 2012; Salazar, 2020). However, due to their vulnerable status, migrant workers can be perceived as disposable (Choe and Lugosi, 2022) and subject to unfairly lower wages, roles that the local population prefer not to perform, e.g., night shifts or certain customer service jobs (Joppe, 2012). Research on the involvement of migrant and refugee workers in the tourism sector has previously explored tourism employment as a tool for developing positive relationships that foster adaption and as a platform that allows self-representation (Janta et al., 2011; Burrai et al., 2022). Yet, most of the research has been analyzed from the perspective of low-skilled workers in developed countries, particularly countries in Europe. As Salazar (2020) noted issues pertaining to tourism and labor migration are undoubtedly context-dependant as countries have diverse social, economic and cultural conditions. In that regard, this study is situated in Peru, a developing country that in recent years has received a considerable number of migrants from another developing country, Venezuela. This influx of migrants has placed additional constraints in the economically challenged and politically unstable host country. The advent of the Covid-19 pandemic further complicated the situation of migrant workers worldwide with current research focusing on the effects of Covid-19 for migrant workers in the tourism and hospitality industries (Dempster and Zimmer, 2020; Singh and Singh, 2020).

Labor migration has also been explored from the perspective of sustainability but its implications have received little attention in academia (Baum and Nguyen, 2019; Salazar, 2020; Choe and Lugosi, 2022). The UNs Millennium Development Goals (2001–2105) and later the Sustainable Development Goals (2016–2030) have placed emphasis on the social aspect of sustainability yet challenges arise due to the lack of consensus regarding how social sustainability goals are to be outlined particularly within the urban context (Dempsey et al., 2011). The guide for policy makers published by the United Nations World Tourism Organization in 2005 contributed with the definition of social sustainability as “respecting human rights and equal opportunities for all in society” (UNEP/UNWTO, 2005, p. 9). In tourism research, social sustainability relates to issues such as governance, migrant worker's security, legal protection and social welfare (Choe and Lugosi, 2022). Nonetheless, tourism employment practices within the workplace can be also a challenge for human rights (Baum and Nguyen, 2019) including poor working conditions, discriminatory treatment of women or minorities and employment of people whose social status makes them vulnerable to exploitation, among others. In effect, while migration and tourism are forms of mobilities, migration tends to be politicized due to the challenges it brings to the social and cultural system of the host country (Choe and Lugosi, 2022). Furthermore, Adams (2020) argued that migration and tourism have been studied from a Western-centered lens raising the need for exploring other cultural and societal contexts. This study examines the Venezuelan migration to Peru from the perspective of potential opportunities in the tourism industry for migrants seeking to integrate into local society.

2.2. Venezuelan migration to Peru

Previous researchers have analyzed the Venezuela-Peru migration corridor using the dualist approach based on push and pull factors. In this view, push factors include hyperinflation, insecurity, political crisis and scarcity of food and medicine. Meanwhile, pull factors include geographical proximity, political stability, migration policies, possibility to save money in a foreign currency and send remittances back home (Biderbost and Núñez, 2018; Facal and Casal, 2018). However, while the push and pull factors approach is useful in explaining the reasons for migrants to leave their country, they do not provide further information regarding the motivations why they selected a particular final destination, Peru, instead of other nearby country. Hence, the particularities of the migratory flow along the Venezuela-Peru corridor can be analyzed from a holistic perspective by applying diaspora theory and transnationalism as a lens of analysis (Cohen, 1997). Under these theories, one can identify that the motivations for Venezuelans to migrate specifically to Peru include the existence of support networks and communities, as well as family ties that provide a softer landing for newly arrived migrants (Massey, 1990; OIM, 2018); possibilities to formalize their migratory situation and obtain employment in regulated sectors; and, perceptions of low discrimination. However, the matter of discrimination has drastically changed over the period of study: 60% of Venezuelans living in Peru have now been subject to discrimination from locals (International Bank for Reconstruction Development, 2019).

As previously mentioned, migration policies implemented by the Peruvian government, particularly the PTP policy, contributed to attract a high number of Venezuelan migrants (Koechlin et al., 2018; Cárdenas et al., 2020; Blouin, 2021). This study took place over the period where Peru changed from the open PTP policy to a stricter approach intended to curb the number of Venezuelans arriving to Peru. Such restrictions were driven by the accelerated increase in Venezuelans in Peru, changes in public opinion, changes in other countries in the region, the length of the crisis in Venezuela and a need to control migration into Peru (Blouin, 2021; Costa, 2021). The transition from policies that supported migration to those that restricted its numbers was evident among at least other 14 countries in the same period (Acosta et al., 2019). Evidence suggest that this transition was aligned to political trends such as Latin America presidentialism prioritizing its citizens rather than providing avenues for migrants' integration (Freier and Castillo, 2020). Whereas, initial policies supported migration, the transition to more restrictive policies did not contemplate structural factors that added vulnerability to the migrant population and their integration. In the literature, these structural factors are known as migrant premium (Basaran and Guild, 2019) and stem from power asymmetries comprising financial pressures, information gaps, mental health pressures, discrimination, among others. In order to address these factors, previous studies have suggested the need to develop educational programs targeted to the local population in order to promote the acceptance of migrant groups (Barajas et al., 2021).

2.3. Economic and social integration of Venezuelan migrants

The literature noted that Venezuelan migrants in Peru tend to be highly qualified professionals which could present great opportunities for the country's economic development (Rojas and Monterroso, 2019). Although in the short term, the inclusion of migrants to the workforce could bring negative impacts such as low wages for the local population, longer-term they could be key for the economic development of the host country by improving productivity and the quality of life of the population (Valdiglesias, 2018). Specifically, in Peru, however, Venezuelans have been vulnerable to exploitation practices given that a great proportion of them are overqualified, working in unregulated sectors, receiving below the minimum legal wage and suffering discrimination at their workplace (Condori et al., 2020). Migrants are perceived as cheap labor and since they are in a vulnerable position, they tend to accept jobs with low wages and minimum legal protection. Furthermore, Venezuelans have been subject to discrimination and xenophobia not only in their workplace but also in everyday life leading to difficulties for their social and cultural integration. Often, discrimination results from a perception from the local community that is based on stereotypes relating to Venezuelans: a dangerous group and threat to Peruvian society (Robinson and Espinosa, 2021). This subjective perception has led to public discourses that promote negative attitudes toward Venezuelan migrants, particularly visible on social media (Freier and Castillo, 2021). This form of segregation based on nationalist discourses and spread in the media is known as “securitization of migration”, a practice whereby populist governments seek to use migrants as scapegoats for deeper problems, including those relating to public security (Bigo, 2002, p.64).

3. Methods

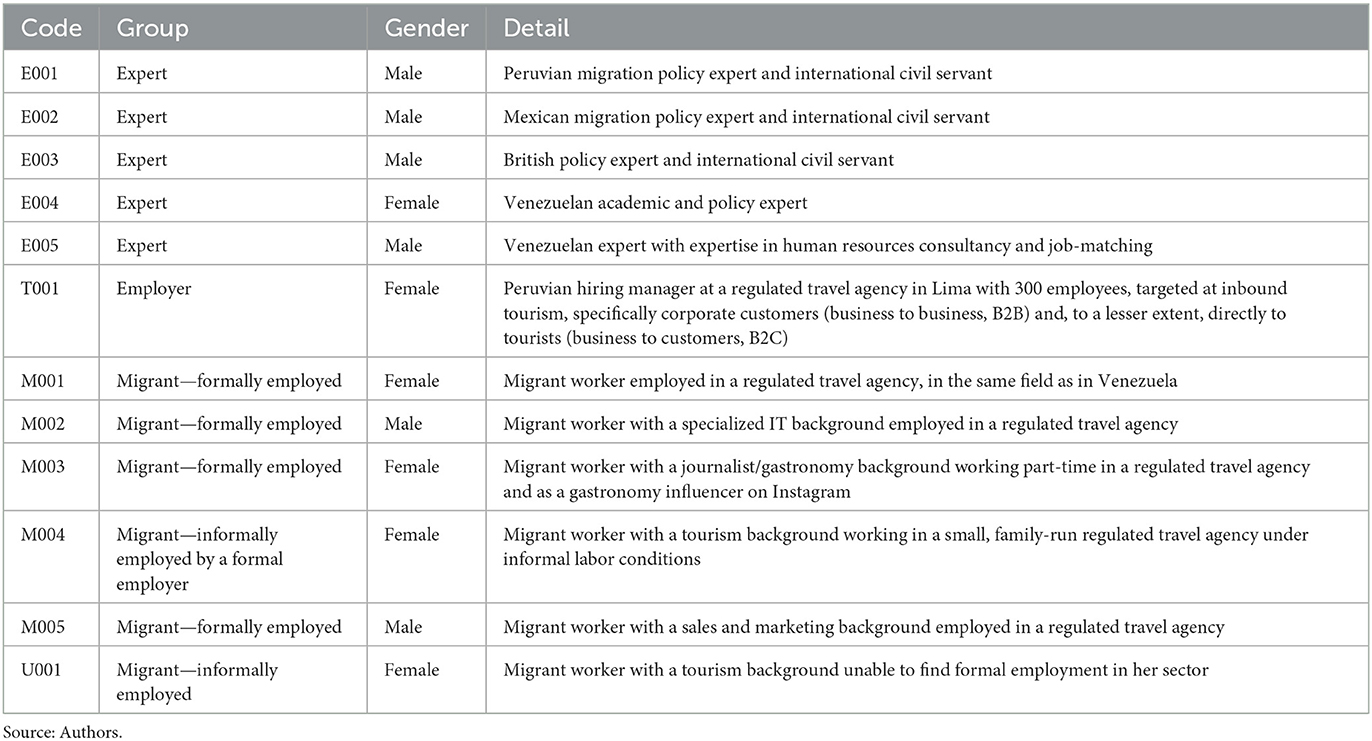

This research is based on primary qualitative exploratory research given the small size of the regulated tourism sector in Peru. 12 semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted in Spanish to allow for in-depth analysis. Interviews were conducted through video-conferencing software Zoom and Google Meet due to Covid-19 and restrictions on social distancing. Conducting interviews using video-conferencing technology facilitated access a varied group of participants while protecting their and our health and upholding travel restrictions imposed at the time. It targeted four distinct groups to allow for data triangulation: (1) Venezuelan migrants (M) employed in regulated travel agencies in Lima between 2015 and 2019; (2) migrants with tourism expertise but who were unable to work in the sector (U); (3) experts (E) working on supporting the Peruvian government's response to the influx of Venezuelans and their integration process, such as international civil servants and academics; and (4) hiring managers (T) in regulated travel agencies in Lima. The triangulation of data through the contribution of different types of participants allows for the crossing of information from two or more sources and its articulation on the same phenomenon under study. Triangulation is a method and tool of cross-checking across multiple sources to look for regularities in research data (O'Donoghue and Punch, 2003). All participants were asked to provide acknowledgment of informed consent, which was read at the start of the interviews. Conversations were recorded so participants were informed about anonymity and confidentiality before the start of the interviews. The conditions for the free and voluntary participation of the participants at the time of consent were ensured, having full knowledge of the objectives of the research, their role, ensuring their rights to consent or not whether to participate, that is, free of coercion. The environment or setting favored communication between the researcher and the interviewee, which guaranteed the confidentiality of what was being recorded.

To find participants, the researchers first looked to consolidate the group of experts. This was achieved by identifying thirty key institutions in government, academia, civil society and the international community, and sending out formal letters setting out the objectives of this study and asking for volunteers. The same process was followed for participants in the employer group. Then, the experts and employers referred the researchers to Venezuelan migrants who fit the profile of study and were keen to participate. After that, additional participants were reached through snowball sampling. This allows for the identification of cases connected directly or indirectly within a network (Creswell, 2013). The conversations were carried out with participants in a relaxed manner. The schedules were guided by the following four questions: (1) how did Venezuelans arrive to Lima and how well did they integrate into this host community from an economic and sociocultural perspective? (2) What roles do they fill in the tourism sector? (3) what opportunities are there for migrants in tourism? and (4) what best practices by employers help with the integration process? The semi-structured questionnaires were prepared for each group and checked by two senior colleagues and two tourism researchers. All questions were applied to all the participants to collect their opinions and contributions and, collectively, build a description of the phenomena.

More specifically for Venezuelan migrants, each interview sought to explore their reasons for choosing Peru as a destination, as well as how they found the incumbent jobs and their motivations to apply for it, and the benefits and/or challenges they perceived in the process. The conversation sought to unpack what roles and jobs they were hired to do in travel agencies, what professional opportunities (if any) were offered to migrants through these jobs, and lastly, whether there were any specific conducts from their employers which helped with their socioeconomic integration. This study also explored sociocultural and economic aspects in the life of migrants such as community life, financial self-sufficiency, prospects for social mobility, working conditions and acceptance of Venezuelan identity by locals. For experts, interviews sought to explore the way migrants had chosen Peru, arrived and settled in Lima, including vis-à-vis opportunities and challenges in the regulated tourism sector. For employers, the goal was to understand recruitment and hiring practices as well as the motivations to hire Venezuelans, and the induction process for migrants and workplace culture toward them. Moreover, emphasis was placed on exploring the kind of roles migrants were hired for and why. Although COVID-19 created challenges with the recruitment of participants, the small sample size of participants was determined by data saturation; this was reached after a total of 12 interviews, where no more new information was discovered. The detail of the participants is on Table 1 below.

For the data coding, each of the interviews was used as a unit of analysis. Themes and patterns were established by transcribing and analyzing the responses (Flick, 2014). First, researchers became familiar with the data by reading all interviews. Each interview was then transcribed and coded according to the topics that were created from each interview conducted and processed. After analyzing the data from the interviews, when no new topics or patterns were identified, researchers established that theoretical saturation had been achieved.

4. Results

The results presented in this section were organized according to the study's four objectives and the themes and patterns that was identified and created consistently from data analysis.

4.1. Arrival of migrant professionals in Lima-Peru in the period 2015–2019

Participants all identified necessity as the main reason for leaving Venezuela. For the experts (E), Venezuelans left their country of origin as a result of an increasingly deteriorating political, economic and human rights scenario, namely “a severe economic crisis”, “a scenario of hyperinflation” and “an oppressive political regime” (E003, E004). In short, “they could no longer subsist” (E001). They explained that the migratory flow in the Venezuela-Peru corridor occurred in “waves” surges correlating to specific migrant profiles at specific points in time (E001, E004). The period of study coincided with the influx of qualified middle-class professionals, whose arrival in Peru was by plane after crossing the Venezuela-Colombia border by foot. Participant migrants in this study fit this profile.

For the experts, Peru and Venezuela shared “solid cultural and historic links” (E002). Spanish is an official language in both countries and family and friendship are central to everyday life. Peruvian migrants settled in Venezuela in the 80s and 90s. Through this lens, experts observed that Lima currently hosts a well-established community of Venezuelan migrants. Not only is Lima considered an obligatory stop for migrants who arrive by air, it also offered them a unique degree of agency and empowerment. Unlike other cities in Peru, the capital centralizes bureaucracy and administrative processes for migrants who wish to regularize their status and obtain a residence permit. Recently arrived migrants will also “find in Lima the firmest social fabric and feel welcomed by their compatriots” (E004).

For the experts, one key element is that Lima was an easy place for migrants to earn a living when they first arrived as it “is where the labor market is concentrated and therefore hosts the greatest number of job opportunities for migrants” (E004). The irony is that this is mainly due to Lima's unregulated industries, as “an attractive aspect of the Peruvian economy for migrants is that 80% is formed by the unregulated market” (E002). Thus, from the moment of their arrival, migrants can work (albeit informally) while looking for permanent jobs in the regulated market. This is essential for their short-term survival in Lima, and to “immediately start to send remittances back home” (E001).

The experts also highlighted that Peruvian migratory policy in the study period directly influenced the number of Venezuelans arriving in Peru during this period. During the government of President Kuczynski, Peru applied a unique response in Latin America to the Venezuelan migratory flow: Temporary Residence Permits, PTP. Experts claim “Peru was on the friendliest side of the spectrum” (E003) as “the Peruvian authorities asked for few formal requirements from the Venezuelan migrant—neither passport nor visa, unlike other countries in the region (E004)”. They described this as “not so much that Peru was opening the door, but holding the door open” (E003).

The themes highlighted by the experts were confirmed by the testimonies of migrants (M) and (U) participants in this study, who were all forced to leave Venezuela out of necessity. For instance, M004 and U001 faced job instability and constant interruptions in education (their own and their dependents). M001's testimony brings in another angle, as he was forced to flee due to unsustainable political persecution. Furthermore, migrant testimonies coincided with the experts' insights regarding decisive factors for them to choose Lima: familiarity with the city, the well-established Venezuelan community, a shared language and pre-existing cultural ties. M005's testimony is illustrative: although she sought to migrate to Canada, she preferred to go to a country where she could communicate in Spanish, her mother language. Similarly, M004 is a dual Venezuelan-Italian national, non-etheless chose to migrate to Lima following in the steps of her brother. For some migrants, like M003 and M005, familiarity with Lima came thanks to previous visits to Peru. M003 had even created a network of professional and personal contacts, so much so that when she arrived they hosted a welcome party for her. Meanwhile, M004 never forgot the sense of security he felt when walking through Lima's most affluent districts. Moreover, migrants explained how they were able to familiarize themselves with Lima prior to travel, accessing readily available information via social media, Whatsapp groups, and “family and friends who have already migrated to Peru” (M005). These informal forums further shaped expectations ahead of travel.

Building on this, migrants consistently corroborate that Peru's policy of migratory openness during the period of this study had a positive influence on their arrival to Lima. For example, M001, who arrived in 2017, confirms that at the time, “the process to obtain a PTP was quick and simple,” and presented a unique opportunity that outweighed any other option. As a result, M001 said that he was able to get a formal job in his professional field in just 3 months.

Finally, migrant participants also coincided with experts regarding the ease of generating income in Lima, either through the regulated or unregulated market. For example, M005 says that before working at a regulated travel agency, he had a series of temporary jobs, namely “laundry driver, waiter and motorcycle mechanic.” M001 indicated that, immediately upon arrival, “it was very easy to get a position as an assistant at a jewelry store” before settling into his current job at a travel agency. U001's experience also added to these statements: a young Venezuelan woman, she is currently working in the unregulated sector but temporarily “as a nanny for a family in Lima while looking for a more stable job” in her field.

In sum, experts (E) and migrants (M) and (U) agree that this was a case of forced migration: departure from Venezuela occurred as the basic needs of the population were not met, hence they had no other choice but to leave in search of better opportunities. Likewise, their choice of Peru and, more specifically Lima, is motivated by three reasons: familiarity, immigration policy, and ease of earning money. This study identified that the combination of these three factors not only directly influenced their decision but, more crucially, allowed for a smoother landing upon arrival. It reduced information gaps which may have increased vulnerability. Having friends and family already established in Lima also provided the newly arrived with strong support networks and greater autonomy, as they shared experiences and information that helped migrants learn faster how to navigate life in Lima. In addition, regularizing their immigration status granted them immediate access to the regulated labor market, financial services, health and education. Perhaps more importantly, Lima offered options for migrants to generate income immediately upon arrival and also in the medium and long-term.

4.2. Jobs held by Venezuelan professionals in regulated travel agencies in Lima and how they come to join these companies

The study identified a partial discrepancy between the participants' perspectives regarding jobs held by Venezuelan professionals in the tourism sector between Experts and Migrants. In one side, Experts (E) interviewed observed general patterns applying to migrant workers in the hospitality sector. There was consensus that most migrant workers take on operational jobs in the sector, such as waiters, receptionists or drivers. The sector was perceived as an area where “operational roles have very low barriers of entry,” and migrants often tend “to accept lower wages and less popular working hours” (E001). In contrast, migrants interviewed (M) offered a different perspective on this matter, given five of the six participants had held jobs at regulated travel agency in Lima. Within this group, three held previous professional experience in the field, and the other two came from other career paths but held transferable skills that meant they could cover specialized roles within the tourism sector.

For migrants who had professional experience working in the tourism sector (M001, M003, and M004), they were employed in Lima, albeit overqualified, namely occupying junior roles compared to the positions they had back in Venezuela. For example, both M001 and M004 used to be senior sales managers back in Caracas, overseeing corporate accounts and multinational operations. However, in Lima, both M001 and M004 worked in entry-level jobs, specifically customer service positions. For M003, the experience was somewhat different. Although M003 had previous experience in the tourism sector, she was already positioned internationally as a professional communicator and Instagram influencer. Her personal profile and reputation allowed her to negotiate working conditions with her employer, resulting in a part-time, flexible position as social media manager in a regulated agency. This provided her with leeway to pursue independent projects in parallel, writing for other virtual platforms and publications on gastronomy and tourism.

Migrants who came from another professional field (M002 and M005) were able to obtain highly specialized roles within the sector based on their technical expertise. For instance, as an IT engineer, M002 had extensive experience in IT systems. As a result, he was hired full-time to develop and launch his employer's online shopping portal. Likewise, M005 was highly qualified as a graphic designer, with more than 10 years of experience in advertising. His extensive experience allowed him to obtain a full-time position in marketing in a regulated travel agency. M002 and M005's lack of previous experience in the tourism sector was not an obstacle when pursuing a role in the sector as they were given a chance to learn once hired. As M005 indicated “I had the tools and knew how to use them, but I didn't know the essence of the tourism sector… It was like you were thrown into the jungle… But over time, I learned.” As such, this study noted that the perspective of Experts (E) was correct in terms of the acceptance of lower wages and more junior roles by migrants (M). However, Experts (E) had not observed that migrant workers with particular professional profiles were well equipped to perform highly specialized roles within travel agencies, such as the ones in the testimonies described by M002 and M005.

This study further identified the way Venezuelan migrants found employment in regulated travel agencies. Firstly, professional networks were essential to learn about job opportunities. Four of the five migrants working in regulated travel agencies in Lima found their jobs through a personal referral or professional social media platform. Both M001 and M005 were sent job advertisements through Peruvian friends who thought they would be good candidates for the position. Similarly, M003 also found the role through a friend's friend in her network of professional contacts. M002 used his professional networks on LinkedIn. Secondly, it was essential for migrants to have regularized their migratory status in order to access these job opportunities. It should be noted that these four migrants had already processed their PTP, which means that they could work legally in Peru. T001, a hiring manager at one such agency, indicated that the human resources departments were often familiar with PTP and other documents for hiring migrants.

These migrants were also guaranteed fair working conditions. Migrants M001, M002, M003 and M005 went through a recruitment and selection process handled by the human resources area within the travel agencies. Once hired, they were granted the same benefits as Peruvian staff: entitlement to annual leave, bonuses, health insurance, pension benefits, among others. E005, an expert in human resources and recruitment in the private sector, explained that having the PTP should allow the insertion of Venezuelans in the labor market “as if they were just another Peruvian.”

These experiences were different to that of U001, who, at the time of the interview, had arrived in Peru only a few months ago and had not yet found a formal job. She admitted not having processed a PTP, visa or any other document to reside and work legally in Peru. Nor had enough time passed to build the professional and personal networks that had helped the other Venezuelan professionals.

Thirdly, the study identified that migrants also accessed job opportunities in regulated travel agencies in the absence of reference networks. This is evidenced in the case of M004, who printed paper copies of her resume and went job-searching in her neighborhood. She got a job in a regulated travel agency, but unlike her compatriots and despite having a PTP, she did not get a formal contract. M004 was not paid on a banked basis, a tactic used by her employer to cut costs and get around the law without being detected by authorities; thus, the employer could get away with never paying M004 health insurance and giving her half the paid vacation compared to Peruvian staff—all of which are employer obligations under Peruvian law. Nevertheless, M004 never raised this as a major issue for fear of losing this job. Thus, the absence of reference networks appears to make it more challenging for migrant workers to access jobs and fair working conditions, even within the formal labor market. Moreover, it shows that having the legal right to work in Peru does not automatically equate to fair and regulated working conditions. When the Covid-19 pandemic hit Peru in 2019, the travel agency where M004 worked closed, and she was made redundant without receiving any compensation. In contrast, M001, M003, and M005, who were also working in travel agencies when the pandemic began, kept their jobs and were even retained by their employers as key workers during the multiple lockdowns, albeit with reduced wages.

The testimonies of the participants reflect that Venezuelan migrants hold two types of positions in regulated travel agencies in Lima: either entry-level or specialized jobs. In the former, the migrant is often underemployed. As for the latter, they occur when the migrant's professional background and skills gave the company a competitive advantage. Likewise, it was found that migrant professionals learn about these positions through professional networks or by sharing their curriculum with potential employers. Networking was particularly important for achieving stable roles that offer fair working conditions. Finally, the right to work legally in Peru was essential to access formal roles but did not guarantee a formal job: in practice, the documentation was not always respected or known by formal employers.

4.3. Limitations regarding the economic and sociocultural integration of Venezuelan migrant professionals in the tourism sector

In the interviews, all participants highlighted a series of structural barriers that limited the process of integration of migrant professionals in the tourism sector. This section focuses on findings around constraints, while the next focuses on opportunities within the tourism sector with the potential to mitigate them.

The experts who participated in this research understood integration as an ideal scenario where migrants feel free to be themselves, and their host communities accept them as they are. Evidence was found in various interviews, in phrases such as “it is a matter of destroying all prejudices, in both directions” (E001), or “there are two dimensions: economic and sociocultural… integration cannot be reduced to having a job, but is also about sharing with the local community” (E002). Integration was also about being able to “access the same services as the local population, especially in terms of education and health” (E002). E003's testimony highlighted two approaches to integration: “the chocolate mix vs. the salad bowl”. The former created a uniform population whereas the latter promoted a cohesive society where individual ingredients maintain their identity.

However, experts unanimously identified a number of structural barriers limiting the integration of migrants. First, experts felt the implementation and bureaucracy of Peruvian government's migration policies in the study period may have created some obstacles for migrants. For example, migrants seeking to regularize their immigration status “must renew their PTP every year… present supporting documents… which costs time and money… The process cannot be done online, but in person in multiple institutions, where staff are often unaware of the process... thus, duplicity is generated and they ask for the same documents without talking to one another” (E005). The migrants further corroborated the experts' insights. For them, migration policies limit their ability to save money and achieve financial stability. Financial pressures force them to perceive their jobs in travel agencies as a short-term fix rather than a long-term solution. For instance, they felt renewing the PTP yearly generates stress in “terms of cost of procedures and waste of time” (M004) and a constraint on independence due to the “information gaps about bureaucratic processes” (M002).

On top of this, for the most part, migrants were overqualified for their roles in comparison to their professional experience in Venezuela; this means their salaries “are not enough to meet the costs of living in Lima, sending remittances, and saving up for the long-term” (M002). Hence, migrant workers did not achieve full economic integration as they perceived their current jobs in travel agencies as a stepping stone to higher-paid jobs in the near future. This was highlighted in the testimony of migrants who expressed “I would quickly accept a better professional opportunity if it were to present itself” (M005). To compensate for the lack of income, another migrant took up “a second job covering overnight shifts, while trying to negotiate a pay rise in the travel agency” (M002) but ended up resigning in search of better opportunities. Balancing several jobs also meant for some migrants was “virtually impossible to socialize because they spent almost 3 h a day moving from one place to another and worked 16 h in two different jobs” (M002), further limiting sociocultural integration.

In addition, participants in the groups of experts and migrants also discussed a series of social barriers creating power asymmetries for migrant professionals: discrimination, xenophobia, machismo and gender stereotypes. For one expert, migrants “hide their cultural markers as Venezuelans by adjusting the topics of conversation, their clothes and even their way of speaking and vocabulary to mimic Peruvian variations” (E004). Similarly, migrants described that they are in “survival mode” outside their workplace (M002). Themes such as self-preservation, camouflage and survival were raised consistently by all migrants interviewed in this study. To avoid harassment or discrimination, they must hide their Venezuelan identity. One migrant remembers that “I had taken a taxi home, in Lima. The driver was listening to a radio show which announced that it was time for the anti-Veneco moment of the day” where the word “veneco” has a discriminating connotation toward Venezuelans (M003). M003 kept quiet and feared for her safety. Other migrants shared work experiences where, when working in customer service positions, they had encountered clients who tried to “scare and intimidate” them (M001) and “demanded to be addressed by personnel who did not have a Venezuelan accent, but are Peruvian” (M001).

Furthermore, the experts highlighted “instances where migrant women had reported sexual harassment on the streets of Lima” (E003) and cited that “Peru is one of the countries with the highest rates of gender-based violence worldwide, due to cultural norms and structural factors... (MIMP, 2016) and gender inequality is highly normalized” (E003). Migrants also identified machismo and discrimination against women as a barrier to sociocultural integration. The migrants in this study expressed suffering “from anxiety when thinking about femicides and rates of gender violence in Peru” (M001). In the workplace, Venezuelan migrants perceived that their Peruvian colleagues have accepted gender inequality as culturally normalized, and “see women as guilty when crimes of gender violence occur, blaming their way of dress or speak, a culture of victim-blaming” (M001).

Thus, these barriers to social integration and culture shocks (xenophobia, discrimination and gender inequality) increased migrants' desire to seek better opportunities for their personal and professional future, regardless of how happy they might have been with their jobs. This is evidenced in phrases like “although the travel agency is the best thing that has happened to me in Peru, I do not see myself there permanently; life opens other doors for you” (M001). In other words, economic integration alone is not sufficient for long-term integration into Lima as the host community.

All participants in both groups of experts (E) and migrants (M) emphasized that migrants feel an acute sense of isolation and loneliness, particularly in their first months in Lima. This is a result of structural economic and social barriers combined with cultural shocks. Migrants not only missed their families and friends in Venezuela, they also had a hard time making friends in Peru and feeling like they truly fit in. To some extent, they are always in survival mode, both financially, socially, psychologically and culturally, and resign themselves to accept asymmetrical relations in relation to the members of the host community. For some, accepting a position of equates to “being humble and learning” (M002), as they feel that “this is not their home and they have no right to change it” (M005), but want to “find ways to contribute” to it (M002). It is worth mentioning that, toward the end of each interview, migrants expressed gratitude for having “had the opportunity to share their experience and be heard”, since it was “an opportunity to counter the discourses of xenophobia toward Venezuelans” that they perceived in the local media in recent years (M001).

This section showed that integration of Venezuelan migrants has been possible but to a limited extend as they still face a number of barriers notably those related to the regularization of their migratory status in the country and continuous incidents of discrimination by local society. Without being able to gain access to a pathway toward residency and the validation of previous qualifications, migrants may continue to struggle to obtain jobs that align to their work experience. Perhaps a more important issue to be addressed is the lack of social integration and mechanisms to protect and assist migrants facing discrimination.

4.4. The role of employers: opportunities and examples of best practice for the economic integration of Venezuelan migrants in the tourism sector

This section focuses on the opportunities and examples of best practice within the regulated travel industry to support the economic and sociocultural integration of migrant professionals. Despite the limitations outlined in the previous section, Venezuelan migrants expressed their hopes of 1 day being able to settle permanently in Peru. For example, there are testimonies that share a desire to “apply for Peruvian nationality” (M004), “stay if I get a good job” (M002), and a “dream of staying in Peru permanently and bringing the family to my new home if I find a formal job in my professional field” (U001). However, a key step in facilitating integration was to find supporting networks that help them counteract the isolation and loneliness described in the previous section. According to participant experts in this study, networks are considered essential for migrants to reduce knowledge gaps and thus vulnerability. One expert interviewed in this study highlighted that “migrants, no matter where they are, need support networks to integrate into their host communities—so-called safety nets” (E002). Some participants have supporting networks that acted as a haven from social barriers and cultural shocks. One migrant found it in religion: “after having gone through a very difficult emotional period in isolation, and despite having a very wide network of professional contacts, I only felt welcomed and protected when I joined the Buddhist community in Lima. They treated me with openness, peace and kindness” (M003). As a result, M003 has decided to stay permanently in Peru and “plans to apply for Peruvian citizenship.”

The research gathered positive evidence to suggest that formal travel agencies perform the same function of support and protection to other migrants. They are perceived as spaces of cultural openness, where migrants are treated with patience, respect and kindness. Migrants themselves emphasized positive experiences of feeling supported and heard. For example, one recalled a moment when she was being harassed by a client for being Venezuelan, but her colleagues and supervisors stood up for her. She says, “they stood by my side at all times; I felt that I would not be left unprotected in the face of the abusive client” (M001). Another participant shared how he felt valued by his colleagues, who “were looking to learn from me, and I really enjoyed sharing my knowledge about technology” because he felt “appreciated and useful” (M002). M002 also commented that they called him “chamo,” which is a Venezuelan-friendly nickname (as opposed to “Veneco” which is pejorative). Although M002 had to leave the travel agency in search of a better-paying job, he said that he missed his colleagues and kept in touch with them frequently. Another migrant cherished her workplace as a place to “share their culture” and recalls how they used to “celebrate birthdays and other festivities together, such as Christmas, by sharing traditional Venezuelan and Peruvian home-cooked food” (M004). The testimonies of the participating migrants coincided with the perspectives offered by one of the employers (T). She referred to the workplace as “the home of a very particular workplace culture where migrants not only fit in well, but are welcomed and thanked for being there” (T001). For her, “the Peruvian team are immensely curious to know more about Venezuelans, their culture and their professional experience”; “the atmosphere is always friendly and this may be because tourism professionals are naturally curious to learn more about other cultures and share elements of their own” (T001).

In all interviews, recurring examples of best practice by employers that helped the integration of Venezuelan migrants were evident. These included:

(i) Familiarization trips (famtrips) as part of the induction process. T001 explained that, in her travel agency, “Venezuelan migrants in marketing and communications positions were invited to participate in famtrips to get a first-hand experience of the products and destinations they will then offer to customers.” M003, who worked as a blogger and communicator for a different agency, also had the benefit of “having a famtrip to Cusco and other major destinations in Peru as part of induction.” T001 and M003 were familiar with the stories of other migrants in tourism who found it very difficult to perform in marketing roles when they had never visited the destinations they promoted regardless of their previous marketing experience back in Venezuela. Therefore, tourism companies would do well to include famtrips as part of the induction for staff in certain key roles as “this would help generate better results and stronger employee performance” (T001).

(ii) Training the human resources department to familiarize itself with the various documents that allow the Venezuelan migrant to be formally employed. Several documents provide migrants the right to access formal jobs and financial services in Peru include PTP, humanitarian visa and asylum seeker status. In cases where “the human resources area was familiar with this documentation, they can hire Venezuelan professionals who are highly qualified to perform in essential positions within the travel agency” (T001). This is evidenced by the fact that three of the migrants interviewed had been asked to remain as essential workers in the agency during the Covid-19 pandemic, while other colleagues lost their jobs (M001, M003, M005). Hence, if a company is not familiar with the documentation of migrants, it could lose on valuable opportunities to hire highly trained and motivated staff.

(iii) Inclusive workplace cultures that thrive on diversity. Travel agencies in this study promoted spaces for cultural exchange and teamwork allowing Venezuelan migrants “opportunities to maintain their cultural and personal identity in the workplace” (T001), unlike the broader society, where migrants can find themselves in a submissive position and constant survival mode (Basaran and Guild, 2019), such as the ones participating in this study. Migrants who worked at a travel agency with an inclusive culture “demonstrate higher levels of job satisfaction and a much stronger sense of belonging” (T001). These migrants also stayed longer in their roles, which not only benefits Venezuelan staff, but also “Peruvian staff also perform better when the work culture is friendly and inclusive” (T001).

4.5. Opportunities for the tourism sector in a post-pandemic context

An additional finding, not originally contemplated in the objectives of this research, related to opportunities for the tourism sector vis-à-vis the integration of Venezuelan migrants in a post-pandemic context. The tourism sector in Peru has been greatly affected by the pandemic and Covid-19 restrictions (Lopez Marina, 2022). The experts and migrants who participated in this research expressed the numerous benefits that Venezuelan professionals could bring to the tourism sector, many of which can be especially relevant to emerge from a crisis: innovation, specialized skills, transferable expertise and creativity. Experts considered that Venezuelan professionals “have the potential to be part of Peru's economically active population” (E003). They further added that “one cannot underestimate the scale of the economic challenges that lie ahead… it is essential for Peru to find a way to use all available human capital in a strategic way” (E003). Venezuelan professionals are part of this human capital that could benefit Peru's recovery if the country prioritizes policies to integrate Venezuelans workers into the regulated labor market. Experts added that migrants could carry valuable knowledge and expertise since “Venezuela was one of the most important tourist destinations in South America… attracting foreign and domestic investment, and the construction of world-class resorts” (E004). Experts also argued that migrants could bring new perspectives to the sector as explained “new people—specifically the migrant professional—can bring with them a dose of naivety, modernity and creativity that cannot necessarily be obtained from the local population, and this is even more important to get out of a crisis” (E003).

More broadly, experts considered that for the Peruvian government, it was essential to “look for ways to be more flexible in the legal requirements so that Venezuelan professionals can work formally” (E004), gradually reducing “structural barriers such as disproportionate taxes” (E003) or “rigidity in the recognition of professional titles” (E003), as well as “changing the narrative of discrimination and xenophobia” (E001). The implementation of these changes would foster better opportunities for Venezuelan professionals to join the regulated workforce. Migrants in this study reinforced the experts' observations in that they were confident on the value they can bring to the sector as highly trained professionals with extensive work experience. For example, one of the participants said “not only do I have 20 years of experience and was a senior executive in Venezuela, but I also grew up on Margarita Island, watching my mother work in a world-class resort” (M004). Similarly, others hold important language skills, such as “Spanish, English, Italian and Russian” (M003). Migrant professionals further agreed that tourism companies should embrace the diversity they can bring, especially if they aim to foster a culture of innovation. For one participant, being a foreigner and new to the tourism sector, makes it “very easy to identify areas for improvement with potential for innovation… but many times Peruvian tourism companies can get stuck in old patterns, showing significant risk aversion, and therefore missing out on opportunities” (M005). To conclude, both experts and migrants provided valuable perspectives on the benefits that the economic and sociocultural integration of the Venezuelan migrant population can bring to the Peruvian regulated tourism sector, specifically in a context of economic recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic.

5. Discussion

This study establishes that the integration of Venezuelan migrants employed in the regulated tourism sector in the city of Lima was partial due to the existence of structural barriers including financial costs, significant time investment and considerable information gaps. These barriers were related to migration policies, local bureaucracy and socio-cultural norms which force migrants to live in continuous “survival mode”. The vulnerability of migrant populations has been previously identified in Basaran and Guild (2019), noting the existence of asymmetric power relationships between migrants and the host community, often unintentionally exacerbated by the host government's policies. Similarly, this study provides further evidence on the politisation of migration when perceived as challenging to local social systems and cultural values (Choe and Lugosi, 2022).

In spite of this, the integration of migrants within workplaces, namely regulated travel agencies, presents evidence for the benefits and potential of full integration of Venezuelan professionals into the workforce. At their workplaces, participant migrants were treated as equals by colleagues and respected by their professional skills and expertise beyond any prejudices. As such, Venezuelans were able to be themselves and felt valued for their contributions. This form of integration allowed migrants to be seen as legitimate members of the receiving group since they were able to retain their personal and cultural identity (Castles et al., 2014; Burrai et al., 2022). Although this integration was mainly focused at the workplace, this could open potential opportunities within the tourism industry to attract professional migrants to its workforce. In effect, the local tourism sector could benefit from the positive contribution of migrants including experience, know-how, training and creativity. As noted in previous research, migrant labor integration will not only contribute to economic development but more importantly enhance cultural diversity and promote avenues for innovation and potential entrepreneurship spaces (Rojas and Monterroso, 2019; Tillbert and Heldt, 2019). Consequently, this study illustrates the need to counter discourses of migration as a security problem (Bigo, 2002; Freier and Castillo, 2020) and instead focused on structural changes in policy and education amongst the local population in order to achieve social sustainability in migrant-resident relationships (Barajas et al., 2021; Choe and Lugosi, 2022).

Regarding the roles that Venezuelan migrants had in regulated travel agencies in Lima and the way these were accessed, this study provides a different perspective to the current literature. In the regulated tourism industry, research has shown that migrant professionals may fulfill entry-level jobs (ILO, 2012; Joppe, 2012); this study shows they can also perform highly specialized roles at regulated travel agencies. This study further identified two key mechanisms that assisted migrants in finding jobs in the tourism sector: formal documentation resulting from regular migratory status, and networks. Having proof of their regularized migratory status allowed migrants to attain the same working conditions as they local counterparts. This showed that public policies design and implementation must incorporate migrant populations (Baum and Nguyen, 2019; Salazar, 2020). Personal connections in the form of networking could serve migrants to attain better job opportunities (Janta et al., 2011). As illustrated in this study, spatial arrangements of friendship and kinship networks could further support migrants in creating meaningful connections that would benefit their integration (Choe and Lugosi, 2021).

In terms of the economic and social integration of migrant professionals, this study identified that Venezuelans working in regulated travel agencies perceive their jobs as a stepping stone toward something bigger and more permanent. Although jobs in regulated travel agencies provided them with financial stability, a good working environment and decent working conditions, Venezuelan professionals were not fully satisfied as they aim to further achieve professional development but potentially in other industries. This showed that the regulated tourism sector promotes the integration of skilled migrants but only in the short-term so it would benefit from addressing factors that would improve job satisfaction to reduce future staff turnover including regulation of work practices and policies to avoid discriminatory treatment of women and minorities. This resonated with previous studies in similar sectors where salaries were not high enough and professional progress is limited (Baum and Nguyen, 2019; Condori et al., 2020).

Outside their workplace's Venezuelan professionals, however, encountered other forms of limitations namely discrimination and xenophobia. Such findings are consistent with previous studies about the negative public standpoint of locals against Venezuelan migrants that face harmful stereotypes, stigma and prejudice (Freier and Castillo, 2021; Robinson and Espinosa, 2021). This research then further supported previous studies that identified limitations to the socio-cultural integration of Venezuelans not only in the tourism sector but in the wider regulated labor market in Peru (Koechlin et al., 2018; ACNUR OIM, 2020). Machismo and gender inequality ingrained in local culture certainly provided an additional layer of vulnerability to the already challenging situation of Venezuelan migrants in Peru.

This study also notes a series of good practices that support a more cohesive integration of migrants within their workplaces. Unlike previous literature that referred to labor stigmatization (Loayza, 2020), the present study identified that migrants were welcomed and valued within their workplaces encouraging the display of their identities and knowledge that became their main asset and a way to contribute to their jobs. Some of the best practices performed by regulated travel agencies include opportunities for professional development, training of their human resources area regarding immigration documentation and promotion of an inclusive and diverse workplace culture. These employment practices could potentially influence migrant workers to remain at their jobs but they must be supported by the country's economic and social environment.

Lastly, this study identifies an unexpected consensus regarding the opportunities that the integration of Venezuelan migrants could offer to the tourism sector in a context of post-pandemic reactivation, namely through contributions of knowledge, experiences, innovation and creativity. Whereas difficulties for a complete integration in the host country were highlighted, this study also determined factors specifically related to the tourism sector that may assist to counteract some of the most adverse aspects that Venezuelan migrants encounter outside their workplaces. As Peru struggles to attract tourists to a pre-pandemic level, the introduction of mechanisms to measure and improve work conditions of migrant workers could favor a more resilient tourism industry (Singh and Singh, 2020) but will require involvement and participation of diverse actors including national bodies (government and tourism minister), non-governmental associations and the private sector (Dempster and Zimmer, 2020). More importantly, if Peru expects to be perceived as a sustainable destination in order to remain competitive in the global tourism market, the issue of social sustainability must be addressed by focusing on the improvement of systematic and structural concerns, for instance, regularization of the status of migrant workers or penalties for companies infringing employment standards to name a few.

6. Conclusion

This study contributes to the literature on migration and sustainable tourism by illustrating the notion of social sustainability through the case of Venezuelan migrants working in the Peruvian regulated tourism sector. It also identifies positive evidence that could support government policies directed at integrating migrant professionals, with the caveat that such policies should be supported by simpler and straightforward bureaucratic processes.

This study presents insights on the potential of tourism as a sector that can enhance social sustainability in a destination. The tourism industry has natural conditions that favor the integration of minority groups such as migrant populations into their host communities, that could result in greater community cohesion and identity. Such natural conditions included open and international-minded professionals and multiculturalism within regulated tourism businesses. Moreover, it favored a positive environment regarding integration experiences for migrants, welcoming their ideas, expertise and culture. Ultimately, by allowing migrant professionals to thrive, the tourism sector contributed to a fairer regulated labor market, diversity and inclusion in a destination, and a destination's commitment to human rights.

By integrating the Venezuelan migrants into their workforce, the travel agencies in this study have benefitted from highly qualified professionals and talent. This sheds light on the potential for replication in the wider Peruvian tourism sector with the support of strong integration policies at government and private levels. This becomes even more important as the local tourism sector has been badly affected by Covid-19 and will need further support to emerge from this crisis and looks to start anew. The study evidenced that migrant professionals can be an untapped source of unique skills, experience, innovation and creativity in a context of economic reactivation for their host communities.

Finally, in spite of the small sample in this study, our findings regarding the Peru experience can be generalized to other tourist destinations impacted by steady surges in human mobility—destinations, like Lima, which quickly become host communities for important population groups of migrants and refugees. The evidence here suggests that host governments may benefit from seeking to understand the professional profiles within migrant and refugee populations, and articulating efforts with the private sector, international cooperation and civil society to match them against the host country's long-term economic needs. In any case, adopting a holistic approach with supporting public policies to facilitate the integration of migrant groups poses many long-term economic, cultural and social benefits, both for the host country and displaced populations.

While this study contributes to the tourism academia by presenting a different perspective on the integration of forced migrants through regulated travel agencies, it also acknowledges some limitations concerning the characteristics of the sample size, the sole location of the study; and, challenges faced in data collection due to restrictions imposed during the pandemic. The sample selection included migrant workers and experts but it could have solely focused on migrants. This study covered only workers in the capital of Lima but Venezuelan migrants have also moved to other cities in other regions, the inclusion of migrants in other locations could contribute with a different insight on whether regulated travel agencies can support (or not) the integration of migrants into the workforce. Data collection during the pandemic presented a considerable challenge for identifying and reaching participants but this study needed to take place during that timeframe.

Recommendations for further research include an extension of the sample size to include other tourism, hospitality or events regulated businesses employing Venezuelan migrants, a comparison of migrants working in the regulated and unregulated tourism businesses, the inclusion of cases from other nearby South American countries that have also received a high influx of Venezuelan migrants and a comparative study now that Peru is currently undergoing the recovery phase of tourism.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MD and CR contributed to conception and design of the study. SC supported MD and CR in the transition of the article from Spanish to English. SC further included additional references to support findings. MD, CR, and SC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

SC declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ACNUR and OIM (2020). R4V. Platform for Coordination of Refugees and Migrants From Venezuela. Available online at: https://r4v.info/es/situations/platform (accessed July 5, 2020).

Acosta, D., Blouin, C., Freier, L. (2019). Venezuelan migration: Latin American responses. Working Documents Number 3. 2nd ed. New Bern, NC: Carolina Foundation.

Adams, K. M. (2020). What western tourism concepts obscure: intersections of migration and tourism in Indonesia. Tour. Geograph. 23, 4; 68–703. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1765010

Barajas, M., Espino, D., Rischmoller, V. (2021). Venezuelan population in Peru during Covid-19: the fight against adversity to achieve social inclusión. Precendente, Revista Juridica, 19, 9–42. doi: 10.18046/prec.v19.4654

Basaran, T., and Guild, E. (2019). Global Labour and the Migrant Premium: The Cost of Working Abroad. New York, NY: Routledge.

Baum, T., and Nguyen, T. T. H. (2019). Applying sustainable employment principles in the tourism industry: righting human rights wrongs? Tour. Recreat. Res. 44, 371–381, doi: 10.1080/02508281.2019.1624407

Biderbost, P., and Núñez, M.E. (2018). From the Rio de la Plata to Orinoco and viceversa: patterns and migratory flows. In: Koechlin, J., and Eguren, J., editors. The Venezuelan Exodus: Between the Exile and Migration. Lima: Tarea Asociación Gráfica Educativa. p. 135-166.

Bigo, D. (2002). Security and immigration: toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alt. Glob. Loc. Pol. 27, 63–92. doi: 10.1177/03043754020270S105

Blouin, C. (2021). Complexities and Contradictions of the Peruvian Migration Policy Regarding Venezuelans. Brazil: Colombia International. p. 141–164.

Burrai, E., Buda, D., Stevenson, E. (2022). Tourism and refugee-crisis intersections: co-creating tour guide experiences in Leeds, England. J. Sustain. Tour. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2022.2072851

Cárdenas, P., Moreno, O., Hinojosa, A. (2020). Venezuelan migrants in Arequipa: motivation and migration trajectory. Illustro, 11, 67–80. doi: 10.36901/illustro.v11i.1308

Carroll, H., Luzes, M., Freier, L.F., Bird, M.D. (2020). The migration journey and mental health: evidence from Venezuelan forced migration. SSM—Popul. Health. 10, 100551; 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100551

Castles, S., De Haas, H., Miller, M. (2014). The Age of Migration. International Population Movements in the Modern World. 5th ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Choe, J., and Lugosi, P. (2022). Migration, tourism and social sustainability. Tour. Geo. 24, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2021.1965203

Condori, M., Reyna, G., Villavicencio, A., Párraga, C., Vilcapoma, D. (2020). Venezuelan Exodus, Labor Insertion and Social Discrimination in the City of Huancayo. Sausalito, CA: Spaces Magazine. p. 1015.

Costa, M. (2021). From Opening to Restriction: Changes in the Peruvian Migration Policy Between 2016 to 2019 Regarding Venezuelans. Dissertation thesis. Peru: The Pontificial Catholic University of Peru.

Creswell, J.W. (2013). Qualitative Enquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S., Brown, C. (2011). The social dimension of sustainable development: defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 19, 289–300. doi: 10.1002/sd.417

Dempster, H., and Zimmer, C. (2020). Migrant Workers in the Tourism Industry: How Has Covid-19 Affected Them, and What Does the Future Hold? Center for Global Development. Available online at: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/migrant-workers-tourism-industry-how-has-covid-19-affected-them-and-what-does-future.pdf (accessed June 7, 2023).

Facal, S., and Casal, B. (2018). A study about migration of Venezuelans to Uruguay. In: Koechlin, J., and Eguren, J., editors. The Venezuelan Exodus: Between the Exile and Migration. Lima: Tarea Asociación Gráfica Educativa. p. 189–250.

Figueroa, J., Cjuno, J., Ipanaqué, J., Ipanaqué, M., Taype, A. (2019). Quality of life of Venezuelan migrants in two cities in the north of Peru. Peru. Magaz. Exp. Med. Public Health. 3, 383–391. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2019.363.4517

Filimonau, V., and Mika, M. (2019). Return labour migration: an exploratory study of Polish migrant workers from the UK hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 3, 357–378. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2017.1280778

Freier, L., and Castillo, S. (2020). Presidentialism and ‘Securitization' of the Migration Policy in Latin America: An Análisis of the Political Responses of the Displacement of Venezuelan Citizens. Internacia: Magazine of International Relationships. p. 1–28.

Freier, L., and Castillo, S. (2021) The Presidentialism ‘Securitization' of the migratory policy in Latin America: An analysis of the political reactions about displaced Venezuelan citizens. Internacia: Revista de Relaciones Internacionales. 1, 1–28.

Gissi, N., Ramírez, J., Ospina, M., Pincowsca, B., and Polo, S. (2020). Responses From SOUTH American Countries Regarding Venezuelan Migration: Comparative Study of Migration Policies in Colombia. Ecuador and Peru: Andean Dialogue. p. 219–233.

Guerrero, M., Leghtas, I., and Graham, J. (2020). From Displacement to Development, How Peru Can Transform Venezuelan Displacement Into Shared Growth. Center of Global Development. Available online at: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/from-displacement-to-development-peru.pdf (accessed February 9, 2023).

ILO (2012). Migrant Workers are Essential to the Hotel Industry. Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_185870/lang–en/index.htm (accessed July 8, 2020).

INEI (2018). Lifestyle of the Venezuelan Population Living in Peru. Available online at: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/boletines/enpove-2018.pdf (accessed June 10, 2021).

International Bank for Reconstruction Development (2019). An opportunity for all: Venezuelan migrants and refugees and the development of Peru. Available online at: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/107621574372585665/text/Una-Oportunidad-para-Todos-Los-Migrantes-y-Refugiados-Venezolanos-y-el-Desarrollo-del-Per%c3%ba.txt (accessed July 6, 2020).

Janta, H., Brown, L., Lugosi, P., Ladkin, L. (2011). Migrant relationships and tourism employment. Ann. Tour. Res. 38, 1322–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.004

Joppe, M. (2012). Migrant workers: challenges and opportunities in addressing tourism labour shortages, Tour. Manag. 33, 431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.05.004

Klarenbeek, L. (2019). Reconceptualising ‘integration as a two-way process'. Migrat. Stud. 9, 902–921. doi: 10.1093/migration/mnz033

Koechlin, J., Vega, E., and Solórzano, X. (2018). Venezuelan migration to Peru: migratory projects and responses from the government. In: Koechlin, J., and Eguren, J., editors. The Venezuelan Exodus: Between Exile and Migration. El Éxodo Venezolano: Entre el Exilio y la Emigración. Collection OBIMID. p. 47–96.

Loayza, J. (2020). Venezuelan migration and job stigmatisation in Peru. Soc. Res. 23, 179–192 doi: 10.15381/is.v23i43.18492

Lopez Marina, D. (2022). Peru Takes “Emergency” Steps to Recover Tourism After the Pandemic. Peru Reports. Available online at: https://perureports.com/peru-takes-emergency-steps-to-recover-tourism-after-the-pandemic/9512/ (accessed January 5, 2023).

Lovón Cueva, M. A., García Liza, A. M., Yogui Gushiken, D. A., Moreno Zegarra, D., and Reyna, B. (2021). Venezuelan migration to Peru: the discourse of labor exploitation. Lang. Soc. 20, 189–202. doi: 10.15381/lengsoc.v20i1.22275

Massey, D. (1990). Social structure, household strategies and the cumulative causation of Migration. Popul. Index 56, 3–26. doi: 10.2307/3644186

MEF (2021). MEF: Between 75 – 80% of Peruvians Work in Informality. Available online at: https://rpp.pe/economia/economia/mef-entre-75-y-80-de-peruanos-trabajan-en-la-informalidad-empleo-trabajadores-noticia-1324222 (accessed April 4, 2023).

Mendoza, W., and Miranda, J. (2019). Venezuela migration to Peru: challenges and opportunities for the health sector. Peru: Peruvian Magazine of Experimental Medicine and Public Health. 497–503.

MIMP (2016). Gender Violence, Framework for Public Policies and State Actions. Available online at: https://www.mimp.gob.pe/files/direcciones/dgcvg/MIMP-violencia-basada_en_genero.pdf (accessed June 1. 2021).

MINCETUR (2020). Flow of International Tourists and Foreign Exchange Earnings From Inbound Tourism. Available online at: http://datosturismo.mincetur.gob.pe/appdatosTurismo/Content1.html (accessed July 6, 2020).