- Future Regions Research Centre, Federation University Australia, Ballarat, VIC, Australia

Tourism is often regarded as an opportunity to “get away” and “escape;” a time for rest and relaxation and “getting away from it all.” Traveling to new places is also thought to be an important “classroom” for children. Traveling to new places was a theme in books by the famous children's author and illustrator Theodor Seuss Geisel (who published under the name “Dr. Seuss”). Whilst Dr. Seuss had numerous hardships in his life including a prolonged illness, no children, and his first wife's suicide, he wrote books that were considered uplifting and fun to read. In the Dr. Seuss book “Oh, the places you'll go!” he wrote “you're off to great places! Today is your day! Your mountain is waiting, so….get on your way!” The idea that children should feel free to visit great places, experience life to its fullest, and feel safe seems on the surface to be axiomatic. Sadly, this is not the experience for all children. Taking a whole tourism systems approach, this paper outlines how family violence impacts each of the five elements in the tourism system. Whilst tourism studies often focus on the positive and boosterish side, to fully understand children in tourism, it is necessary to look at it in its entirety. This means acknowledging and understanding how children's tourism experiences might be limited. This paper reveals that children can be denied permission to undertake certain travel due to court orders or denial by the perpetrator of family violence. It is hoped that greater awareness of this topic may result in better and fairer family law orders to allow more tourism experiences for children who live with or have lived with family violence.

Introduction

Almost two decades ago, it was estimated that around 275 million children in the world had been exposed to family violence (UNICEF, 2009). It is believed that around 25% of children have been exposed to family violence during their life (Finkelhor et al., 2009). This paper discusses how family violence impacts “the places they'll go.” Importantly, this paper draws attention to a little-understood concept in society—that separation from family violence does not necessarily equate to freedom for victims or their children.

This paper presents a new scholarly discussion in tourism—that of the tourism experiences for children who are either living with family violence or have experienced it. Whilst there is no literature on this intersection, literature on the framework for this paper and children in tourism are presented. Researching this new area poses challenges due to the absence of existing research outlining tourism experiences for children living with family violence. Accordingly, this paper aims to present a conceptual outline based on presenting how the very nature of family violence will necessarily impact the five elements of the tourism system. The author, through lived experience, draws on knowledge of family violence to present depth to the outlining of the concepts in this new research. As this paper takes a whole tourism systems approach, this section discusses the whole tourism system framework. It then outlines the literature relating to children in tourism and the literature relating to children's experiences in family violence.

Literature review

A whole tourism system approach is used as the conceptual framework for this paper. Tourism cannot occur unless the five elements in the tourism system are met. This conceptual paper argues that family violence impacts the tourism experiences of children, and to explain this, the impacts at each element will be discussed. That is, if there are impacts at the tourism elements, then the entire tourism system for children who are victims of family violence is affected.

Most tourism textbooks have an introductory chapter that explains tourism as an open system. Discussions about tourism system models go “hand-in-hand” with the scholar Neil Leiper who developed different tourism system models in the late 1970's. Neil Leiper was “among the first Australians publishing in the Annals of Tourism Research, Tourism Management, and the Journal of Travel Research” (Pearce, 2011, p. 189). Going back 40 years to 1982, “the wider tourism research scene was either stagnant or hidden” (Pearce, 2011, p. 189). Businesses were receiving advice from consultants regarding tourism plans (Pearce, 2011), and accordingly, Leiper's conceptual work regarding tourism arrived at a time when quality tourism work was desperately needed. Leiper's first academic paper was published in Annals of Tourism Research in 1979 (Backer and Hing, 2017).

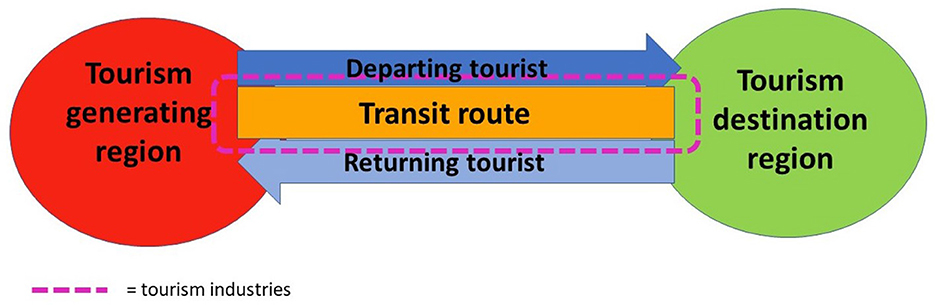

Leiper developed three tourism system models to serve as frameworks to explain tourism, and probably the best-known of these models is his Simple Whole Tourism System Model (Figure 1). Although that model was first published in 1979 (Leiper, 1979), many tourism textbooks continue to use this model to outline the framework of tourism as it continues to be a valuable and simple way to explain and understand tourism. As the framework is a simple way to explain the essential components of tourism, it is a useful framework to use in various tourism studies, including this paper.

Figure 1. A simple whole tourism system model. Source: adapted from Leiper (2004).

Tourism is an open system and requires five elements for tourism to occur. Leiper's whole tourism system model has become a common organizing framework for the study of tourism and has also been used as a conceptual framework for tourism PhDs [for example Backer (2009) and Lamont (2009)].

Whole tourism systems comprise five elements—tourists, tourist generating regions, transit routes, tourist destination regions, and tourism industries. The tourism system is open and influenced by externalities. It is all five elements and the relationships between them that make up a whole tourism system (Leiper, 2004). The Simple Whole Tourism System Model is considered a basic whole tourism systems model, useful for explaining the tourism system for a trip involving one tourist destination and a returning trip back to the usual place of residence. The model recognizes that tourism involves three geographic elements, the generating region, destination, and transit route. It also shows tourism as an open system, acknowledging externalities in the environment that influence touristic trips. In addition, it recognizes two other tourism elements—the tourist, as well as tourism industries. Tourism industries are represented by the pink dotted rectangle, as tourism industries can serve the needs of tourists at any of the three geographic points (i.e., the generating region, destination, and transit route).

The transit route represents the path that takes the tourist from their generating region (where they usually reside) to the destination they are going to; and the return journey. The transit route may be a different pathway, or could be traveled using a different mode of transport for each departing and returning trip. Tourism industries supply services and products to the tourist to consume for their trip, and those services and products might be consumed in their usual residence (i.e., tourism generating region) such as booking a trip through a travel agent, buying a plane ticket, buying items for the trip, and consuming food at the airport or bus station. Services and products can be consumed along the journey to and from the destination. Services and products are also consumed at the destination itself.

Those services and products consumed at the destination can be heavily influenced by children, even though the children may not be paying for those products and services. Tourism literature is increasingly highlighting the importance of improving our understanding of the perceptions and interests of children within the family tourism research area. Although, such research can be difficult to undertake.

Children in tourism

Younger children in particular may be difficult to research and may have more difficulty in communicating their feelings about holidays away from home and what they enjoy and do not enjoy. Gathering research can also be especially challenging in some countries due to ethics constraints. For example, in Australian universities, committees must be established called “Human Research Ethics Committees” (HRECs) to consider applications from researchers who wish to undertake any research that involves humans as participants in the study. Ethical standards are scrutinized and responsibility sits within the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Certain types of research are considered to be of a higher risk and ethics approval can be challenging to obtain. For example, studies involving grief, sexuality, trauma, depression, and minors are some of the higher-risk studies that are scrutinized more heavily and may not obtain ethics approval. The very nature of research involving children contains the dilemma of a power imbalance which can be problematic and flag risk (Canosa and Graham, 2016). Children are recognized as being vulnerable and they may feel intimidated when interviewed by a researcher (Yang et al., 2023). As ethics committees may be disinclined to approve the risk, ethics approval may be difficult. This can serve as a deterrent for researchers to undertake the application paperwork (which can take a great number of hours) and possibly be unsuccessful or receive so many required changes, that it dilutes the purpose of the study. For example, a study to interview children about their tourism experiences might only be cleared at some institutions if a parent or guardian is present. However, the child's perspective of the holiday away from home in the presence of a parent/guardian may be altered (i.e., the child might say what they think the parent wants them to say). This could be especially the case if things went wrong on the holiday. Researchers also need to consider whether the research does actually need children involved in it, or can it be undertaken in a different way to consider potential psychological harm to the children (ERIC, 2022). For some research projects, there might be other ways to consider obtaining information that represents children's views. For example, for particular projects, it might be possible to have peers of children interview the children respondents to reduce the power imbalance (Canosa et al., 2018). Of course, more difficult topics (such as family violence) are unsuited to such options.

In any type of research project, it is critical to ensure that research does not risk harm to anybody; especially so for vulnerable people such as children. Although, it is also important to balance that with the rights that children have “in relation to their protection from harm, provision of care and resources, but also to their participation in matters that affect them, such as research about their lives” (Canosa and Graham, 2016, p. 219). It is with this view that family courts do not allow children to be present on matters that impact them and their lives; but yet those children might rightly argue that they should be entitled to a voice on matters so incredibly important to their life. Ironically, the fact that children have no voice in family court because the court is concerned with harm to their child, may result in greater harm because harmful orders are made in the child's absence. The frustration of children without a voice in court can be heard through various stories told by Hill (2019).

In terms of what we do know about the child's lens in tourism research, a number of studies have provided some foundational aspects. In discussing children's holidays, it has been recognized for some time that “children are now tourism consumers in their own right” (Swarbrooke and Horner, 2007, p. 203). Although, whilst children are known to influence purchasing decisions, they are still assessed in a passive way because “while the young person is the consumer, the parent is usually the customer, making the final purchase decision and paying the bill” (Carr, 2011, p. 203).

There may also be a sense of children being homogenous across countries. However, as was indicated through a study by Seaton and Tagg, there were differences observed where French and Italian children were consulted more about family holiday choices compared with children from Belgium and the UK (Seaton and Tagg, 1995). Nearly half (48%) of the Italian children interviewed for Seaton and Tagg's study reported that they had played a “big part” in the choice of tourism destination; a figure that was more than four times the rate reported by UK children (11%) and more than double the figure for Belgian children (22%) (Seaton and Tagg, 1995).

Although regardless of country of residence, for parents in general, there can be a type of pressure, or at least perceived pressure, that a family holiday is a happy holiday and that they can be “identified as the socially defined ‘good parent”' (Carr, 2011, p. 56). According to Seaton and Tagg (1995) the notion that families holidaying away from home must be happy times is a persistent marketing image that is “part of the mythology of tourism and an established fact in tourism data” (Seaton and Tagg, 1995, p. 1). The pressure to have the type of family holiday that marketers suggest everyone else seems to have may result in some people inaccurately reporting on their holidays and reinforcing this impression through “happy holiday snaps” on social media. In addition, Backer and Schanzel believe “a dominant ideology of parenting has emerged that increasingly perceives holidays as opportunities for ‘quality family time' or ‘purposive leisure time' away from everyday distractions” (Backer and Schänzel, 2012, p. 105).

Various studies have highlighted the positive relationship between tourism and quality of life and that taking a holiday away from home has positive effects. Further, whilst stress is known to negatively impact a person's wellbeing, tourism is known to reduce stress (Kawakubo and Oguchi, 2022), and it improves both mental health as well as physical health (Chen et al., 2016). The concept of being away from the daily routine, mundane tasks, pressure, and sources of stress and discomfort would naturally give someone time to recuperate and temporarily relax and reduce stress. At least, that is the generalized assumption for all those who take holidays away from home—the assumption is that the person is getting away from the source of stress and able to rest and relax.

Children in family violence

Family violence is much broader than physical violence and is defined by Australia's Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) as “violent, threatening or other behaviour by a person that coerces or controls a member of the person's family (the family member), or causes the family member to be fearful” (Commonwealth of Australia, 1975; Sect 4AB). Living with family violence is very traumatic, and this trauma includes children, even if they are not the subject of the abuse themselves. Various behavioral disorders may arise for those children who live or have lived with family violence. Some of those trauma displays can be:- anxiety and depression, self-harm, difficulty managing stress, insomnia, reduced empathy, difficulty to develop positive relationships, and difficulty going to school and doing school work (Barnardos Australia, 2021). Whilst separation is often thought of as freedom from family violence, many women report that child contact arrangements present them with a risk of post-separation violence (Humphreys and Thiara, 2003). As outlined by one respondent in a study:

It has been a nightmare. I had no idea what a hell-hole I was living in until I left. Only I thought when I left it was a fresh start, but I didn't realize that my difficulties were just beginning (Humphreys and Thiara, 2003, p. 195).

As such, family violence can follow victims and their children even if they have separated. In fact, the court orders may be so shocking, that abusive perpetrators of family violence have significant unsupervised time with their children, and the protective parent is not present, which can make things worse for the children. Whilst the number of children exposed to family violence remains unclear, there are some studies that provide some type of indication.

Obtaining data about family violence is very difficult, and additionally difficult when it comes to children. However, Table 1 provides an estimated number of children who had been exposed to family violence in 2006, which presents an overview of the global nature of family violence impacts on children. Some of the ranges are broad, and of course, the numbers are not provided with context as a percentage of population. As such, the estimated numbers only provide readers with a small window of information. Whilst the estimates are imprecise, they can be regarded as some indication of the diversity of impacted countries—family violence is everywhere.

In examining these data for one country, Australia, Table 1 indicates that the number of children exposed to family violence in 2006 was estimated to be between a very broad range of 75,000–640,000. However, it is estimated that around 25% of children in Australia have been exposed to family violence (Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse, 2011; Barnardos Australia, 2021), which would put the estimate in 2006 for Australia to be around 1.1 million (based on 25% of the number of children in Australia in 2006). This suggests that the estimates in Table 1 may be under-representing the situation.

Regardless of the actual level of exposure, a key point from this discussion about family violence and children is that the numbers are very much there and that children from countries across the globe are exposed to family violence. Many millions of children around the world are impacted. As previously mentioned, even when the victim manages to leave the abusive relationship, that victim and those children, are not free. The abuse may continue and may even escalate. Women reported that “separation was an extremely difficult state to achieve” (Humphreys and Thiara, 2003, p. 200) but even if it was achieved it did not represent freedom from abuse. A disturbing 76% of the 161 separated women in the study by Humpreys and Thiara reported suffering from further abuse as well as harassment from the abusive partner who they had separated from Humphreys and Thiara (2003).

Whilst various studies have highlighted that the child's voice is negligible in tourism literature, similarly, the child's voice is negligible in family violence. Overwhelmingly, family violence is perpetrated against women and children by males, and courts often fail these victims with the court orders, despite claiming to operate in the best interest of the child. As was argued by Zentveld (2023), court orders can negatively impact children such as her discussion of a victim mother who had separated from a proven perpetrator of family violence but was denied the opportunity to take her children on an international holiday to see the maternal grandparents. The reason for this was that the proven male perpetrator was only allowed 7 days of holidays away from home and the judge did not want to be unfair to the (abusive) father (Zentveld, 2023). These situations will make it difficult for children to have the types of tourism experiences they might otherwise have. And therefore, the places those children will go, might be short domestic trips and restricted ability to connect with family who live far away.

Discussion

The previous section, the literature review, discussed whole tourism systems and then outlined the literature with respect to children in tourism literature and children living with family violence. This discussion section will now conceptualize these matters through the whole tourism systems framework, outlining the issues impacting children in each of the five tourism system elements.

Tourism generating region

As was previously outlined, the tourism generating region is the “home” region for the tourist. This is where the travel from home begins and since tourism is a tour (i.e., a circuit), it is also where the tourist returns to. It is within this element of the tourism system, that the needs and motivations for travel are generated. A primary motivation amongst adults is to “escape from the pressures of life in the everyday” and that “children may also seek a holiday experience in the form of escape” (Carr, 2011, p. 42). Although it should be noted that children are not homogenous and that their desired holiday experiences may vary considerably during different ages and stages of development. Potentially, the needs of babies and very young children might be the same for holidays away from home as they are when they are home (Carr, 2011).

A problem for children who live with family violence is that the thing that they probably most want to escape is violence. The schoolwork, the mundane, the usual routines of school days are what is thought to be what children may desire escaping from and having freedom from. However, for those children living with family violence, it is likely that the thing that those children would most want to escape from is family violence. But sadly, “family violence doesn't take a holiday” (Zentveld, 2023, p. 2). Therefore, the whole notion of motivation, wanting to escape, rest, and relaxation, simply does not apply. As was outlined in Table 1, children exposed to family violence are everywhere. It is not limited to certain countries. Accurate information does not exist in part because of under-reporting; but children will be impacted by family violence even if they are not directly the targets. The statistics on family violence are largely based on estimates or reporting through certain departments (for example police or health) and of course not all family violence is reported. However, based on a global review of available data, family violence impacts 161 countries and areas with the data showing:

“unequivocally that violence against women is pervasive globally. It is not a small problem that only occurs in some pockets of society; rather, it is a global public health problem of pandemic proportions, affecting hundreds of millions of women and requiring urgent action” (World Health Organization, 2021, p. XII).

So, wherever the tourism generating region is located, family violence can occur. After all, “family violence happens to everybody, no matter how nice your house is, no matter how intelligent you are” (Tuohy, 2022). Tourism motivational theories are built on the assumption of families being perfectly imperfect; but not abusive and violent. Yet with 25% of children exposed to family violence, then our tourism theories do not apply to around one-quarter of the global population of children.

Tourism destination

The choice of tourism destination may be made by all members of the family or dominated by one member. Children may have no say, a little influence, or a huge influential role. As Seaton and Tagg (1995) discovered, the level of influence by children over the tourism destination varied between countries, and whether children perceived the dominant member in destination selection was the mother or father also varied between countries as well as between social classes. What role each member of a family may have with tourism destination choices when the family lives with family violence is unknown. Possibly in many of those cases, the perpetrator of family violence may hold the dominant role. Although, how power and control are wielded by perpetrators of family violence varies, and what is withheld and controlled is not the same in all family violence households (Bancroft, 2002).

However, what is more likely to be a common theme for families living with family violence, is that when things go wrong at that destination, the perpetrator will likely want to yield their abuse in the same way on holidays as they do when at home. Holidays may present an elevated risk of family violence. Crime statistics indicate significant increases in family violence incidents during sporting events, and family events (e.g., Christmas) (Zentveld, 2023). Therefore, the experience for the child who lives with family violence when at the tourism destination may be very different to what is assumed by tourism motivation theories. Not only could things be worse than living at home due to things going wrong resulting in added stresses, but the outlets and escapes that may exist at home (e.g., school, friendships, and family) are not at the tourism destination. This might result in feelings of loneliness and withdrawal. The marketing image of families happily spending quality time together and having a “happy holiday” may be far from the reality for children who live with family violence.

Transit route

Following on from the discussions about tourism generating regions and tourism destinations, the transit route connects the two geographic regions. As previously mentioned, the transit route to the destination may differ from the transit route for the return journey back home to the tourism generating region. Transit routes may involve different transport modes but are most commonly by airplane or self-drive.

Many travel plans are soured by things that go wrong. Roads blocked by accidents or heavy traffic congestion resulting in lengthy periods in the car. Weather, strikes, staffing issues, or mechanical issues can result in lengthy delays at airports. Flights can be canceled. Baggage can go missing. Travel is not always “smooth sailing.” Anyone who has experienced unfortunate travel incidents will immediately recognize how stressful and unpleasant travel can be.

Travel even at the best of times can be perceived as boring for children. Driving is often undertaken by the “male” parent, the children sit in the back seat, which is considered less comfortable, with less leg room, less width space, less view, a lower hierarchical position, and more prone to feeling car sickness. Thus, even when things are going as well as they can be, transit routes by car can be mundane and unpleasant for children. When there are two, or worse—three children in the backseat, there is more crowding, more tension, and likely none of them want the lowest hierarchical position of all—the middle seat. Tensions rise. The child's experience can often be lowest, most particularly when self-drive is selected. Similar scenarios can be imagined for flying.

Putting these tensions into a situation of children living with family violence is worse. Controlling and abusive behavior can escalate when things go wrong. Things can go wrong during the travel to and from the destination. This can have an alarmingly disturbing impact on the child, and then the child returns to their home destination after what may have been a heightened experience of family violence. This is not in the tourism motivational models. This is not the marketing image of family holidays.

Tourism industries

Tourism is partially industrialized. This means that some businesses that serve tourists have strategies that target tourists' distinct attributes (e.g., theme parks). Other businesses can be partially in tourism and partially in other industries (e.g., cafes and restaurants) and may have no strategies that are aimed directly at tourists, and accordingly, tourists for those businesses may be a fringe market. Contrary to many statements in the media and tourism journals, there is no one giant “tourist industry” and such a statement demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of what are industries and how they are defined. Many businesses across numerous different types of industries may serve tourists but those businesses are not competing with each other for the same seller as they are across different industries. For example, the Hilton Hotels in Sydney are not competing with the cafes in London. They are not in some nebulous industry called “tourism” but positioned across unique and separate industries that may serve tourists as part of their market.

Experiences from tourists in the various industries they have contact with during their tourism experience can be vast depending on the level of industrialization of the trip. Those who travel independently and select experiences such as camping or caravanning may have dealings with fewer industries than those who travel by airplane, stay in commercial accommodation, dine out every day, and engage in a wide range of commercialized man-made activities. The child may or may not have a major role in these choices. These experiences form part of the tourism system and overall experience. However, if a child is living with family violence, and if they feel unsafe, their level of experience for any activity (including the ones they choose) may be diminished.

If the perpetrator of family violence is making many of the decisions relating to the trip, the types of experiences (i.e., industries engaged with) may not be attractive to the child. For example, experiences may have low-level industrialized tourism, such as driving by a private motor vehicle, going to the beach, and staying with a relative. As outlined in the previous section about transit routes, self-drive experiences may involve things going wrong and the perpetrator may take that out on the partner and/or the child. Either way, it negatively impacts the tourism experience of the child. Staying with family can also be stressful (Backer and Schänzel, 2013), and accordingly, the lower industrialized tourism experiences might create stresses that result in problematic behavior and not be the type of tourism experience desired.

As described by Zentveld (2023), Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs outlines that if the foundation needs are not met (e.g., safety, which is the second foundation need), then it can be difficult to obtain the higher-order needs. As Zentveld said, “a person preoccupied with safety cannot possibly appreciate the views and the activities at the destination” (Zentveld, 2023, p. 120). This is because if the fear “is extreme enough and chronic enough (the person), may be characterized as living almost for safety alone” (Maslow, 1943, p. 376). As such, a child who feels their safety is threatened and feels on edge, may literally prefer to be home. Home has family violence, but away from home with added tensions and financial pressures from costs that arise from industrialized activities, could result in additional conflict and fewer avenues for escape and support.

Tourist

The final element in the tourism system is the tourist. As was outlined earlier in this paper, the role of the child as tourist varies across ages and stages of development as well as the country of residence and socio-economic class. Regardless of the choices selected for the destination, transit route, and what tourist industries are utilized during the tour, the child who lives with family violence potentially has a diminished voice than other children. Patriarchy can be a driver of family violence where male perpetrators of family violence see that they are entitled to make the decisions on behalf of the family. They do not see that they are in an equal relationship with any other member of the family. They are in charge. While it is acknowledged that perpetrators of family violence may not necessarily be male and that family violence can also exist in same-sex couples, overwhelmingly the vast majority of perpetrators of family violence are males against women and children. Also, often when women are abusive toward the male, it can be as a result of self-defense and forms a different type of abuse (Bancroft, 2002).

Whilst tourism research has highlighted that the child's voice is not present in the literature to the degree in which it deserves, the tourism experience of those children who live with family violence is entirely absent. Their experiences, contributions to choices and decisions, and what holidays away from home mean for them are unclear. What is also unclear is what those touristic experiences might be like for them if their victim parent does manage to separate from the perpetrator parent. What sort of holiday might be experience by the child who is holidaying away with the perpetrator?

Conclusion

Family violence impacts every one of the five elements of the tourism system. Perpetrators of family violence can prevent children from traveling outside of the region, including visiting extended family such as maternal grandparents. In almost all cases, perpetrators of family violence have equal legal rights to make decisions that affect the major aspects of their child's life such as where they live, their religion, education, health, name, and includes things such as approving a passport. The perpetrator almost always has rights with time, even with proven family violence due to the legal frameworks (Zentveld, 2023). These rights mean that the perpetrator can take their children on holidays and can equally prevent those holidays for their child/ren to have with their victim parent. Courts may be called upon to make decisions regarding whether children can be permitted to have holidays that their perpetrator parent denies; and even so, the court may not rule in the favor of the victim.

It is thought that “for families, tourism has become a necessity rather than a luxury” (Qiao et al., 2022, p. 1). Tourism experiences can be associated with improved quality of life (Moscardo, 2009; Dolnicar et al., 2012, 2013; Uysal et al., 2016; Backer and Weiler, 2018; Backer, 2019) but children who live with family violence may not benefit at all from those tourism experiences. Further, if separation does occur, children may find themselves unable to experience many types of tourism experiences (e.g., international trips to visit extended family on the victim's side) due to restrictions placed on the victim by court orders trying to place equity on both the perpetrator and victim through controlled time away with the child/ren.

The lack of voices from children in the tourism literature has been considered a marked gap (Poria and Timothy, 2014; Khoo-Lattimore, 2015). Notably, “Children's voices are largely omitted from policy agendas and research narratives and this includes much tourism research” (Bott, 2021, p. 4). An important Research Note drawing attention to that gap in 2014 (Poria and Timothy, 2014) also observed that “children are frequently obliged to travel as part of a family unit, possibly even against their own will” (p. 94). This point is highly pertinent, especially for children living with family violence.

The structure of family and the experiences of families on holidays away from home has become a growing area of research interest. It is recognized that “the family unit is the center of social activities. The most intimate and most important emotional bonds are formed with individuals' children and families” (Qiao et al., 2022, p. 8). The differences within family structures are also recognized since “family tourism research is affected by different cultural contests, social conditions, and economic development. Therefore, family tourism research scenarios need to be diversified to enrich their knowledge systems” (Qiao et al., 2022, p. 8–9).

In tourism, there is an increasing argument that the child's voice needs to be stronger. However, in family law courts, the child's voice is not present. Children under the age of 18 cannot set foot even as silent attendees in courts and yet, decisions are made in court on behalf of those children without courts having directly heard the child's voice (Go To Court Pty Ltd, 2022). Decisions made by courts can impact the child in many ways, including the child's tourism experiences.

When children go away during school holidays to travel away and then return, it is assumed that those experiences have been happy times and that the children would come back refreshed and ready to start the new school term feeling energized and enthused. Yet, none of the tourism motivational theories takes account of the experiences of children living with family violence whose holiday away from home may have been as bad as being at home or possibly even worse. It has been thought that out of all the fields of buying behavior, there are few “where all members of the family so equally share in the consumption of a product as tourism and holidays” (Seaton and Tagg, 1995, p. 3). Although, this suggests that all members of the family are equal and that the holiday is “happy.”

Children who are, or have been, exposed to family violence might suffer in various ways. Family violence does not come along for only certain touristic experiences and is unpredictable. When living with family violence as a family, the perpetrator may take out their frustrations during trips away when things go wrong (e.g., accommodation was not what was expected, flights were delayed, traffic build-up on self-drive trips). If the victim does manage to separate from the perpetrator, family violence does not leave because almost always, the perpetrator has time with the child/ren and that includes holidays. Therefore, the child will have tourism experiences with the perpetrator parent without the safety of the victim parent being present. Tourism experiences with the victim parent can be impacted because the perpetrator may deny trips and seeking of court orders to have extended travel may be unsuccessful. Accordingly, the child is limited from certain trips (e.g., international trips to visit maternal family). Thus, family violence can impact children's tourism experiences while ever they are children, and even after separation (perhaps even more so). This prevents children living with family violence to be “off to great places.”

Understanding the role of children in tourism is important. Holidays away from home can be far from enjoyable for children who may continue to see the abuse but simply away from home rather than within it (Zentveld, 2023). Given that one-quarter of children have been exposed to family violence, this field is far from insignificant in volume and importance.

It is hoped that this paper has shed some light on a little-understood aspect of society, which may result in changes to ensure more children experience tourism in the manner in which they should. This paper is the first to intersect children in tourism with family violence. Further work in this area is needed given that around 25% of children have been exposed to family violence. It seems important to understand what the tourism experience for children who have experienced family violence is like, and what role do those children have with making tourism decisions. It seems important to also understand what the tourism experiences are like for children forced to holiday with a parent who is a perpetrator of family violence after the parents have separated. Such information may assist with improving future court orders.

Assumptions in society that holidays away from home are necessarily positive and happy are not accurate for all family types. It is acknowledged that gathering data in this complex field is very difficult, which makes it more complicated for furthering knowledge. Insights about children in tourism through the non-perpetrator parent would add important insights. Risks exist for victims of family violence, not only children, and as such gathering information from the parent after separation could be an option. It seems important to understand more about how risks can occur in the tourism system in order to then look for strategies to mitigate and educate. Such information may also result in better and fairer family law orders. Perhaps even children might have a voice in court about decisions which impact them, which includes but is not limited to tourism experiences with each parent. In time, it is hoped that more children will be “off to great places!” in the manner in which Dr. Seuss wrote.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Australian Domestic Family Violence Clearinghouse (2011). The Impact of Domestic Violence on Children: A Literature Review. Available online at: https://earlytraumagrief.anu.edu.au/files/ImpactofDVonChildren.pdf

Backer, E. (2009). VFR Travel: An Assessment of VFR vs. Non-VFR Travellers (Ph.D. thesis). Lismore: Southern Cross University.

Backer, E. (2019). VFR travel: Do visits improve or reduce our quality of life? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 38, 161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.04.004

Backer, E., Hing, N. (2017). Whole tourism systems: An academic portrait of neil leiper. Anatolia 28, 320–325. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2016.1212300

Backer, E., Schänzel, H. (2012). “The stress of the family holiday,” in Family Tourism: Multi Disciplinary Perspectives, eds H. Schanzel, I. Yeoman, and E. Backer (Bristol: Channel View Publications).

Backer, E., Schänzel, H. (2013). Family holidays-vacation or obli-cation? Tour. Recreat. Res. 38, 11081742. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2013.11081742

Backer, E., Weiler, B. (2018). Travel and quality of life: where do socio-economically disadvantaged individuals fit in? J. Vacat. Mark. 24, 159–171. doi: 10.1177/1356766717690575

Bancroft, L. (2002). Why Does He Do That? Inside the Minds of Angry and Controlling Men. New York, NY: Penguin Books Ltd.

Barnardos Australia (2021). The Effect of Domestic Violence on Children in Australia Women Men the Effect of Domestic Violence on Children in Australia. Available online at: https://www.barnardos.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/BA_22_DomesticViolence_FactSheet.pdf

Bott, E. (2021). “My dark heaven”: Hidden voices in orphanage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 87, 103110. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103110

Canosa, A., Graham, A. (2016). Ethical tourism research involving children. Ann. Tour. Res. 61, 219–221. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.07.006

Canosa, A., Graham, A., Wilson, E. (2018). Reflexivity and ethical mindfulness in participatory research with children: What does it really look like? Childhood 25, 400–415. doi: 10.1177/0907568218769342

Chen, C.-C., Petrick, J., Shahvali, M. (2016). Tourism experiences as a stress reliever: Examining the effects of tourism recovery experiences on life satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 55, 150–160. doi: 10.1177/0047287514546223

Commonwealth of Australia (1975). Family Law Act 1975. Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2019C00101

Dolnicar, S., Lazarevski, K., Yanamandram, V. (2013). Quality of life and tourism: A conceptual framework and novel segmentation base. J. Bus. Res. 66, 724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.09.010

Dolnicar, S., Yanamandram, V., Cliff, K. (2012). The contribution of vacations to quality of life. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 59–83. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.04.015

ERIC (2022). Ethical Research Involving Children. Available online at: https://childethics.com/ (accessed December 13, 2022).

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., Hamby, S. (2009). Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Paediatrics 125, 1–13. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42

Go To Court Pty Ltd (2022). Heard But Not Seen: The Views of Children in Parenting Matters. Available online at: https://www.gotocourt.com.au/family-law/views-children-parenting-matters/ (accessed December 12, 2022).

Humphreys, C., Thiara, R. K. (2003). Neither justice nor protection: Women's experiences of post-separation violence. J. Soc. Welf. Fam. Law 25, 195–214. doi: 10.1080/0964906032000145948

Kawakubo, A., Oguchi, T. (2022). What promotes the happiness of vacationers? A focus on vacation experiences for Japanese people during winter vacation. Front. Sport. Act. Living 4, 1–11. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2022.872084

Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2015). Kids on board: Methodological challenges, concerns and clarifications when including young children's voices in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 18, 845–858. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1049129

Lamont, M. (2009). Independent Bicycle Tourism in Australia: A Whole Tourism Systems Analysis. (Ph.D. thesis). Lismore: Southern Cross University.

Leiper, N. (1979). The framework of tourism: Towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 3, 390–407. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(79)90003-3

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 50, 370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346

Moscardo, G. (2009). Tourism and quality of life: Towards a more critical approach. Tour. Hosp. Res. 9, 159–170. doi: 10.1057/thr.2009.6

Pearce, P. (2011). Respecting the past, preparing for the future: The rise of Australian Academic Tourism Research. Folia Tur. 25, 187–205.

Poria, Y., Timothy, D. J. (2014). Where are the children in tourism research? Ann. Tour. Res. 47, 93–95. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2014.03.002

Qiao, G., Cao, Y., Chen, Q., Jia, Q. (2022). Understanding family tourism: A perspective of bibliometric review. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.937312

Seaton, A. V., Tagg, S. (1995). The family vacation in Europe: Paedonomic aspects of choices and satisfactions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 4, 1–21. doi: 10.1300/J073v04n01_01

Tuohy, W. (2022). “You Still Battle”: Rosie Batty on Five Years of Family Violence Action. Available online at: https://www.theage.com.au/national/you-still-battle-rosie-batty-on-five-years-of-family-violence-action-20210320-p57cic.html (accessed February 13, 2022).

UNICEF (2009). Behind Closed Doors: The Impact of Domestic Violence on Children. New York, NY: UNICEF.

Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., Kim, H. (2016). Quality of Life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 53, 244–261. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

World Health Organization (2021). Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018 – Executive Summary. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yang, M. J. H., Yang, E. C. L., Khoo, C. (2023). Ethical but amoral: Moral considerations for researching cambodian host-children. Tour. Manag. 94, 104646. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104646

Keywords: family violence, children, tourism, abuse, control, whole tourism system

Citation: Zentveld E (2023) “Oh, the places you'll go!”—But not for those children trapped by family violence. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2:1089107. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2023.1089107

Received: 03 November 2022; Accepted: 23 February 2023;

Published: 17 March 2023.

Edited by:

Elaine Chiao Ling Yang, Griffith University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Antonia Canosa, Southern Cross University, AustraliaEliza Raymond, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Copyright © 2023 Zentveld. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elisa Zentveld, ZS56ZW50dmVsZEBmZWRlcmF0aW9uLmVkdS5hdQ==

Elisa Zentveld

Elisa Zentveld