- 1Department of Management, Marketing and Entrepreneurship, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand

- 2Geography Research Unit, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

- 3Department of Service Management and Service Studies, Lund University, Helsingborg, Sweden

- 4Department of Organisation and Entrepreneurship, Linneaus University, Kalmar, Sweden

- 5Centre for Research and Innovation in Tourism, Taylor's University, Subang Jaya, Malaysia

The Sustainability Of Tourism

Tourism is a major economic activity and employment generator. According to the World Travel Tourism Council (2021), prior to the COVID-19 pandemic travel and tourism was an eight trillion-dollar industry that generated about 10 percent of the global GDP in 2019. Although global tourism was greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, the loss of national and regional income as a result of the pandemic related mobility restrictions and resultant job loss, arguably have almost had a paradoxical effect in that tourism and hospitality has achieved greater public policy recognition because the impacts of COVID-19 have demonstrated just how economically important the tourism sector is.

Recognition of tourism is not just isolated to tourism destinations or to major urban tourism centers and transport hubs. The decline in international and domestic tourism has also had significant impacts for conservation because it affected the availability of funds available for a wide range of nature-based tourism and heritage conservation related activities, especially in protected areas (Spenceley et al., 2021). For example, the World Travel Tourism Council (2019) estimate that, in Africa over a third of all direct tourism GDP could be attributed to wildlife, while globally, 21.8 million jobs were directly and indirectly supported by wildlife tourism. These figures reflect the estimates of Balmford et al. (2015) that protected areas receive eight billion (8 × 109) visits per year, of which more than 80% are in Europe and North America, and generating US$600 billion a year in direct in-country expenditure and US$250 billion a year in consumer surplus. Nevertheless, as they noted, such expenditure dwarfs the investment of governments into protected area and biodiversity conservation.

As Spenceley et al. (2021, p. 113) observe, “the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how dependent some conservation areas and many local communities are on tourism, and also the physical and mental health benefits of nature for visitors. But it has also shown how vulnerable tourism is to forces beyond its control.” The vulnerability of tourism is also related to factors it has contributed too IPCC (2022a). For example, while tourism clearly benefits from protected and natural areas (Spenceley et al., 2017), it has also contributed to their loss, whether directly through tourism related development leading to habitat loss and land-use change, or more indirectly through the introduction of alien species, cumulative change, and its contribution to climate change.

Tourism is a major industrial contributor to climate change. Although international tourism bodies have long claimed a contribution of the order of approximately 5.5%, excluding radiative forcing (Scott et al., 2016), the life cycle analysis of Lenzen et al. (2018) showed that from 2008 to 2013, the global carbon footprint of tourism increased from 3.9 to 4.5 GtCO2e, representing 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions and contributed largely through transport emissions, food consumption and waste, and tourist shopping. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2021, 2022a,b) highlights the existential challenge that climate changes poses for many species, ecosystems and cultures. It is now “unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean, and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere have occurred” (IPCC, 2021).

As well as substantially contributing to climate change, tourism is also greatly affected in terms of resource loss, e.g., snow availability for winter and alpine tourism or coral bleaching for marine tourism; sea level rise for beach tourism; increased temperatures; and biodiversity loss and landscape change (IPCC, 2021). Significantly, the effects of climate change do not occur in isolation and need to be understood within the context of the interdependence of climate, ecosystems and biodiversity, and human societies, including the economy (IPCC, 2022a). For example, the fifth Global Biodiversity Outlook concluded, “Biodiversity is declining at an unprecedented rate, and the pressures driving this decline are intensifying. None of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets will be fully met, in turn threatening the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals and undermining efforts to address climate change” (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2020, p. 2). This therefore creates a major challenge for tourism with respect to how it mitigates its impacts. For example, the IPCC (2022b), observed, “mitigation of aviation to ‘net zero' levels, as required in 1.5°C emission scenarios, requires fundamental shifts in technology, fuel types, or changes of behavior or demand,” But then goes on to note, “the literature does not support the idea that there are large improvements to be made in the energy efficiency of aviation that keep pace with the projected growth in air transport.” Therefore, to what extent is the tourism industry, which has long been built on growth (Hall, 2022), willing to accept changes in behavior and/or demand to meet its emissions reduction goals?

The Paradoxes Of Tourism

It has long been recognized that tourism is full of many paradoxes (Dann, 2017; Milano and Koens, 2022). It offers wealth and income but often relies on low paid labor to remain competitive. It promises authentic experiences but these become commoditised (Dann, 2017). It pays for conservation yet simultaneously leads to cultural and landscape change and contributes to ecosystem loss (Hall, 2010; Holden, 2015). And for the tourist it promises escape and freedom, but in the end it remains part of and contributes to what people are often wanting to escape from Hall (2022). Fundamentally, the desire for wellbeing and hedonistic joy simultaneously contributes to accelerating undesirable global environmental change, of which climate is only one dimension (Gren and Höckert, 2021). As Dann (2017) suggests, such notions of paradox are important as, although seemingly self-contradictory, they contain a possible truth or insight that needs to be carefully revealed and further explored.

Arguably, the various paradoxes provide the central focus for trying to make tourism sustainable. One of the main ways this has been done, and the dominant interpretation, promoted strongly by the UNWTO, government and industry, has been with respect to finding “balance” between the supposed three pillars of tourism (economy, society, environment) (Mbaiwa and Stronza, 2009; UNWTO, 2015; Hall, 2019). However, such an approach, while perhaps intuitively appealing, has not made tourism more sustainable in global terms, and does not adequately recognize the importance of planetary boundaries with respect to how economy and society are ultimately constrained by the Earth's natural resources (Higham and Miller, 2018). Therefore, if the sustainability and tourism relationship is to be made effective it is crucial that there are shifts not only with respect to how tourism operates but also how it is conceptualized, studied, and the results of research communicated.

Shifting Thinking

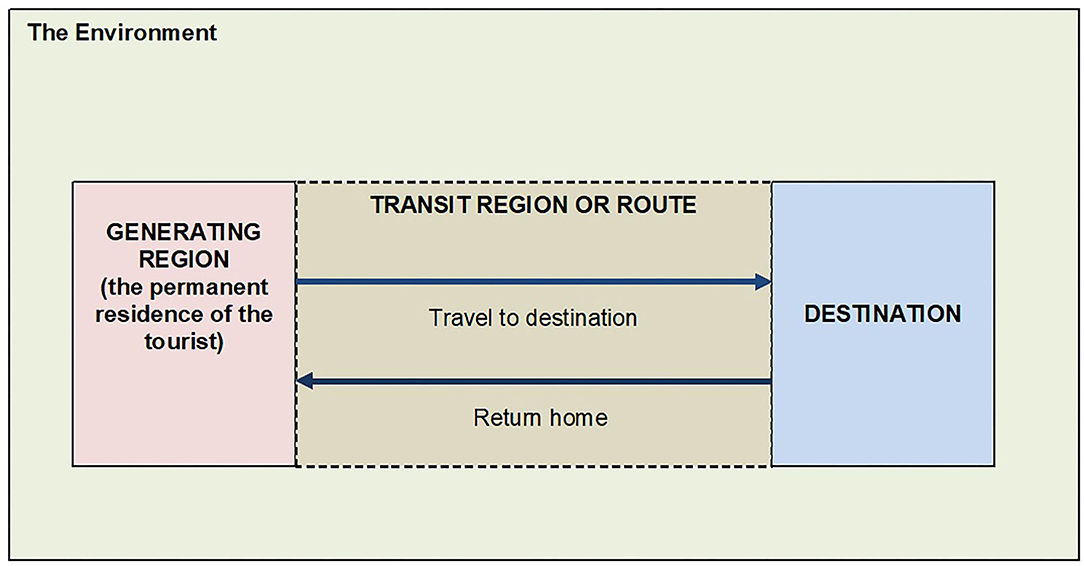

As noted above, paradoxes are useful tools to encourage exploration because of the insights they reveal. However, a key part of such paradoxes is that they emphasize the relationality between things, whether they be concepts, agency and structure, or between the different elements of the tourism system. The importance of systems thinking has long been noted in tourism but it's often descriptive use has hidden much of its explanatory and analytical potential. Moreover, even though the notion of a tourism system (Figure 1), which emphasizes the connectedness between tourism generating regions and destinations, the flow of people over space and time, and de facto the changes in psychology as a result of such connectedness and flow, the vast majority of tourism research only provides unconnected snapshots of moments in the various relations within the tourism system. As important as it is, much of the destination-based research that dominates in tourism, together with market assessments of actual or potential tourists tends to occur in relative isolation (Park et al., 2016). There is little longitudinal research over time (Sæþórsdóttir and Hall, 2020), the prevalence of one-shot studies means we do not really know how sustainable sustainable behaviors and behavioral interventions actually are. Despite the notion of a tourism system being frequently cited in research and referred to in lectures and textbooks understanding is actually highly fragmentary and relations between elements often poorly understood, with subsequent implications for shifting it to a more sustainable state. This is the grand challenge that research on tourism faces.

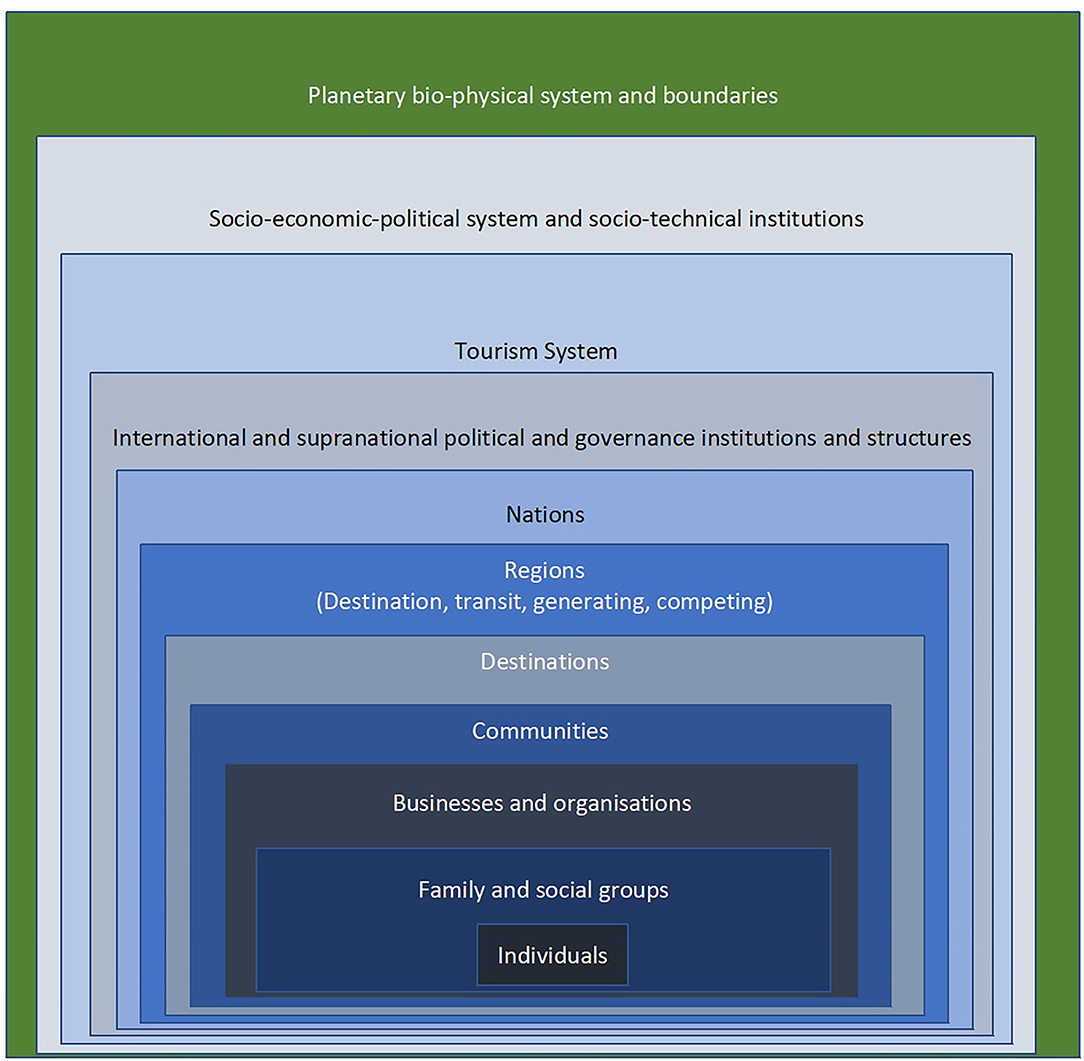

A key element in working toward sustainable tourism is not only understanding the tourism system as the relationship between tourist generating areas and destinations and the consequent implications, but also realizing that the tourism system also occurs at multiple embedded scales. The emergence of resilience as a key issue in tourism highlights the importance of panarchical structures and the capacity for emergence and change and the potential consequences of a shift in the state of one scale to have implications both up and down the tourism panarchy (Hall et al., 2017; Lew and Cheer, 2017; Figure 2). From a relational perspective such understandings are incredibly important as they highlight the connectedness of the various elements of the tourism system, the relationship between structure and agency, as well as the multilayered and complex nature of destinations (Paasi and Zimmerbauer, 2016).

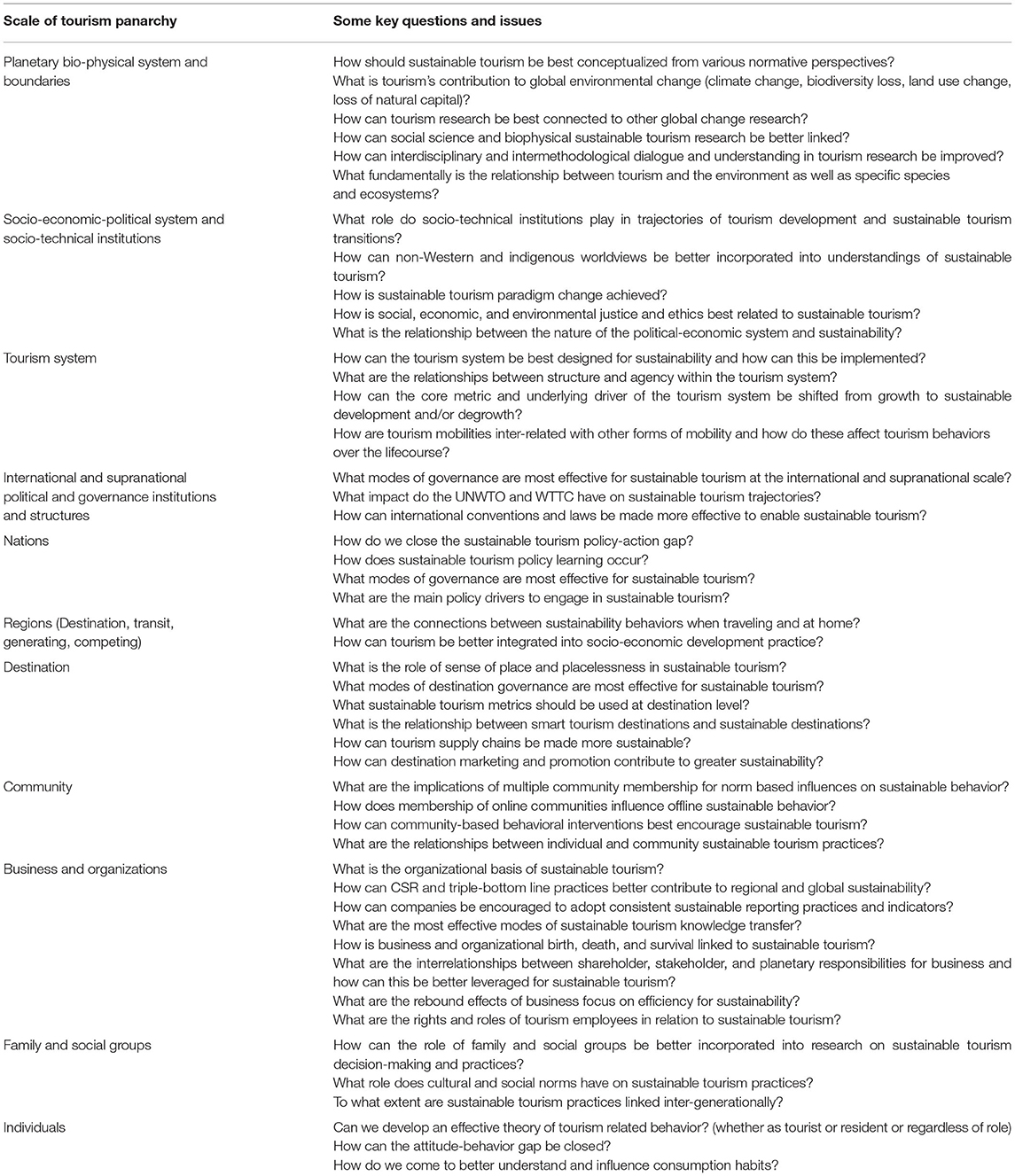

Within the panarchy of tourism key issues and questions arise at each scale (Table 1), with the results of research at each scale having potentially profound issues up and down the various scales. Importantly, it needs to be recognized that the sustainability of a regions may lie outside of tourism, with much depending on how sustainable tourism is actually understood, i.e., is it tourism for sustainability or the sustainability of tourism? At the macro scale research is needed on the adequacy of existing paradigms and models of sustainability and sustainable tourism. Sustainable tourism along with sustainable development is a highly contested concept (Saarinen, 2006, 2015; Bramwell et al., 2017) and raises the adequacy of existing definitions and approaches, including the oft-quoted standard Brundtland definition of sustainability: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, p. 43). Or is there a need to move beyond BAU: “Brundtland as usual” (Hall et al., 2021), in considering sustainable tourism? This may also include developing a greater understanding of and connection with non-Western worldviews and especially those of indigenous peoples.

At the other end of the tourism panarchy there is an immense need to better understand sustainability behaviors and the attitude-behavior gap (Juvan and Dolnicar, 2014; Han, 2021), especially with respect to the undertaking of different practices by the same people in different parts of the system (Barr et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2020), as well as differences by gender, culture and other socio-demographic factors. Such understandings may clearly contribute to the development of more effective behavioral interventions. However, also of importance is to realize that the research conducted at the microscale is also connected to macro level of questions of how sustainability and sustainable tourism is understood, as the macro level conceptualisations frame how questions of sustainability are conceptualized and potentially even asked, i.e., the GIGO principle (Garbage In, Garbage Out) (Conlon, 1999; Saltelli, 2002). As Émile August Chartier stated, “Nothing is so dangerous than an idea, when you only have one idea” (quoted in Conlon, 1999, p. 117).

Communicating Sustainable Tourism

The early twenty-first century has undoubtedly witnessed a revolution in the way that information and knowledge is conveyed, and its implications of academic research and knowledge transfer. Frontiers in Sustainable Tourism is an example of such a shift that is geared toward open access (OA) publishing. Undoubtedly, there is opposition to such publishing modes, not least because of issues of where the costs of publishing are located and the capacity to cover such costs. However, OA publishing and greater emphases on knowledge transfer is clearly favored by many governments as they seek to generate improved economic and practical returns from academic research. Potentially there are also other advantages as OA publishing provides opportunities for other voices and places to become part of the global discussion of ideas surrounding sustainability. It is therefore in this space that Frontiers in Sustainable Tourism will operate, complementing existing more traditional journals and publishing outlets, with an explicitly integrated OA framework that connects sustainable tourism research to a range of other disciplines and to the different elements and scales of the tourism system. Research in sustainable tourism needs a range of ideas, openness, and transparency, as it seeks to influence and transfer knowledge to stakeholders and provide a new trajectory for tourism development, behaviors and practices. Sustainable tourism is both a destination and a process and we need a full range of contributions as we seek to make tourism more sustainable in what is probably the most important journey that any of us will face in our lifetimes.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Balmford, A., Green, J. M. H., Anderson, M., Beresford, J., Huang, C., Naidoo, R., et al. (2015). Walk on the wild side: estimating the global magnitude of visits to protected areas. PLoS Biol. 13, e1002074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002074

Barr, S., Shaw, G., Coles, T., Prillwitz, J. (2010). ‘A holiday is a holiday': practicing sustainability, home and away. J. Transp. Geogr. 18, 474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.08.007

Bramwell, B., Higham, J., Lane, B., Miller, G. (2017). Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the journal of sustainable tourism: looking back and moving forward. J. Sustain. Tour. 25, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1251689

Conlon, T. (1999). Critical thinking required or seven deadly sins of information technology. Scott. Aff. 28, 117–146. doi: 10.3366/scot.1999.0041

Dann, G. M. (2017). Unearthing the paradoxes and oxymora of tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 42, 2–10. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2016.1222651

Gren, M., Höckert, E. (2021). “Hotel anthropocene,” in Science Fiction, Disruption and Tourism, eds I. Yeoman, U. McMahon-Beattie, and M. Sigala (Bristol: Channel View), 234–254. doi: 10.21832/9781845418687-021

Hall, C. M. (2010). Tourism and biodiversity: more significant than climate change? J. Herit. Tour. 5, 253–266. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2010.517843

Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: the 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 1044–1060. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

Hall, C. M. (2022). Tourism and the capitalocene: from green growth to ecocide. Tour. Plan. Dev. 19, 61–74. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2021.2021474

Hall, C. M., Lundmark, L., Zhang, J. J. (2021). “Conclusions—degrowing tourism: can tourism move beyond BAU (Brundtland-as-Usual)?,” in Tourism and Degrowth: New Perspectives on Tourism Entrepreneurship, Destinations and Policy, eds C. M. Hall, L. Lundmark, and J. J. Zhang (Abingdon: Routledge), 239–248. doi: 10.4324/9780429320590-18

Hall, C. M., Prayag, G., Amore, A. (2017). Tourism and Resilience: Individual, Organisational and Destination Perspectives. Bristol: Channel View. doi: 10.21832/9781845416317

Han, H. (2021). Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: a review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 29, 1021–1042. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2021.1903019

Higham, J., Miller, G. (2018). Transforming societies and transforming tourism: sustainable tourism in times of change. J. Sustain. Tour. 26, 1–8, doi: 10.1080/09669582.2018.1407519

Holden, A. (2015). Evolving perspectives on tourism's interaction with nature during the last 40 years. Tour. Recreat. Res. 40, 133–143. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2015.1039332

IPCC (2021). “Summary for policymakers,” in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

IPCC (2022a). “Summary for policymakers,” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

IPCC (2022b). “Transport,” in Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Juvan, E., Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 48, 76–95. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2014.05.012

Lenzen, M., Sun, Y.-Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y.-P., Geschke, A., Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 522–528. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

Lew, A. A., Cheer, J. M (Eds.). (2017). Tourism Resilience and Adaptation to Environmental Change: Definitions and Frameworks. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315463971

Mbaiwa, J. E., Stronza, A. L. (2009). “The challenges and prospects for sustainable tourism and ecotourism in developing countries,” in The SAGE Handbook of Tourism Studies, eds T. Jamal, and M. Robinson (London: Sage), 333–351. doi: 10.4135/9780857021076.n19

Milano, C., Koens, K. (2022). The paradox of tourism extremes. Excesses and restraints in times of COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 25, 219–231. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2021.1908967

Paasi, A., Zimmerbauer, K. (2016). Penumbral borders and planning paradoxes: relational thinking and the question of borders in spatial planning. Environ. Plan. A 48, 75–93. doi: 10.1177/0308518X15594805

Park, J., Wu, B., Morrison, A. M., Shen, Y., Cong, L., Li, M. (2016). The tourism system research categorization framework. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 21, 968–1000. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2015.1085885

Sæþórsdóttir, A. D., Hall, C. M. (2020). Visitor satisfaction in wilderness in times of overtourism: a longitudinal study. J. Sust. Tour. 29, 123–141. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1817050

Saarinen, J. (2006). Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 33, 1121–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.007

Saarinen, J. (2015). Conflicting limits to growth in sustainable tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 18, 903–907. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.972344

Saltelli, A. (2002). Sensitivity analysis for importance assessment. Risk Anal. 22, 579–590. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.00040

Scott, D., Hall, C. M., Gössling, S. (2016). A review of the IPCC fifth assessment and implications for tourism sector climate resilience and decarbonization. J. Sustain. Tour. 24, 8–30, doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1062021

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2020). Global Biodiversity Outlook 5—Summary for Policy Makers. Montreal, QC: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Spenceley, A., McCool, S., Newsome, D., Báez, A., Barborak, J. R., Blye, C.-J., et al. (2021). Tourism in protected and conserved areas amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Parks 27, 103–118. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2021.PARKS-27-SIAS.en

Spenceley, A., Snyman, S., Eagles, P. (2017). Guidelines for Tourism Partnerships and Concessions for Protected Areas: Generating Sustainable Revenues for Conservation and Development. Report to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity and IUCN. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/tourism/doc/tourism-partnerships-protected-areas-web.pdf

UNWTO (2015). United Nations declares 2017 as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development. UNWTO. Available online at: https://www.unwto.org/archive/global/press-release/2015-12-07/united-nations-declares-2017-international-year-sustainable-tourism-develop

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

World Travel Tourism Council (2019). Economic Impact of Global Wildlife Tourism. Available online at: https://www.atta.travel/news/2019/08/the-economic-impact-of-global-%20wildlife-tourism-wttc/

World Travel Tourism Council (2021). Economic Impact Report. Available online at: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

Keywords: sustainable tourism, global change, tourist behavior, urban tourism, nature-based tourism, tourism system, tourism impacts, crisis

Citation: Hall CM (2022) Sustainable Tourism Beyond BAU (Brundtlund as Usual): Shifting From Paradoxical to Relational Thinking? Front. Sustain. Tour. 1:927946. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2022.927946

Received: 25 April 2022; Accepted: 13 May 2022;

Published: 03 June 2022.

Edited and reviewed by: Jarkko Saarinen, University of Oulu, Finland

Copyright © 2022 Hall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: C. Michael Hall, bWljaGFlbC5oYWxsQGNhbnRlcmJ1cnkuYWMubno=

C. Michael Hall

C. Michael Hall