- 1School of Wildlife Conservation, African Leadership University, Kigali, Rwanda

- 2School of Tourism and Hospitality, College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 3Conservation Capital, Nairobi, Kenya

- 4Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda

- 5International Gorilla Conservation Program, Musanze, Rwanda

The success of protected areas depends to a large degree on the support of local communities living in and around these areas. Research has shown that where communities receive tangible and/or intangible benefits, from protected areas they are often more supportive of conservation. Rwanda introduced a tourism revenue sharing policy in 2005 to ensure that local communities receive tangible benefits specifically from protected area tourism and to enhance trust between the Rwanda Development Board (the then Rwanda Office of Tourism and National Parks) and local communities, and to incentivize the conservation of wildlife and protected areas. This study reviewed the tourism revenue sharing programme over the last 15 years, including primary and secondary data, which included interviewing more than 300 community members living around three national parks, as well as other relevant stakeholders. The results show that the tourism revenue sharing programme has resulted in a positive linkage between the national parks and development. Since 2005, ~80% of the funding was used for infrastructure and education projects. The funds are distributed through local community cooperatives, and most local people who are members of these cooperatives had received or were aware of tangible benefits received by the community and tended to have more positive attitudes toward tourism and the national parks. Despite a large amount of tourism revenue being disbursed over the 15-year period, there are still challenges with the programme and the overall impact could be enhanced. Recommendations as to how to address these are presented.

Introduction

Overview of benefit-sharing from protected area tourism

If structured properly, tourism can contribute to local and national socio-economic development, as well as to conservation, directly and indirectly, within and around protected areas (PAs) (Snyman and Spenceley, 2019). In Africa, particularly in eastern and southern Africa, tourism revenue is one of the major contributors to the financial sustainability of PAs and contributes to local community development, through employment, value chains and revenue-sharing programmes. For example, in Kenya 50% (US$ 30 million) of Kenya Wildlife Services' annual budget is generated from tourism, while in Zimbabwe 80% of the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority's budget is derived from tourism (Lindsey et al., 2020). Benefit-sharing programmes are often complex, involve numerous and diverse stakeholders, and have challenges in terms of equity, sustainability and good governance (Snyman and Bricker, 2019). It is important, therefore, that benefit-sharing mechanisms and policies are reviewed and adapt and evolve over time to ensure that they are reaching the people who need them the most, and who are most directly and negatively impacted by a PA, mostly in terms of human-wildlife conflict (HWC) or restricted access to natural resources.

It is broadly recognized that the meaningful involvement of communities that live in and/or adjacent to PAs is critical to the long-term sustainability of these conservation areas (Ahebwa et al., 2012; Dewu and Røskaft, 2018). Depending on their level of involvement, communities that live in, or adjacent to, PAs can be effective partners in conservation or can exacerbate threats to PAs, and sometimes it is a combination of both (Kihima and Musila, 2019; Störmer et al., 2019). Ensuring that rural communities value conservation, through the receipt of tangible and intangible benefits, is critical to the long-term viability of PAs (Dewu and Røskaft, 2018; Störmer et al., 2019). The basic premise is that if communities receive benefits, both tangible and intangible, from conservation and tourism in and around PAs, they will be more inclined to hold positive attitudes toward PAs and to conserve natural resources in PAs (Kaaya and Chapman, 2017; Spenceley et al., 2017; Dewu and Røskaft, 2018; Snyman and Bricker, 2019; Ziegler et al., 2020). In addition, if local people can earn an income, or receive benefits through community-based tourism revenue sharing programmes (TRSPs), in turn, they will value wildlife and help protect it (Wunder, 2000; Walpole and Thouless, 2005; Munanura et al., 2016).

There is no universal definition of revenue sharing. For the purposes of this study, we refer to the definition provided by Franks and Twinamatsiko (2017): “Revenue sharing is concerned with the arrangements for sharing a proportion of the protected area's income with local stakeholders to provide an incentive for them to support conservation.” In this study, stakeholders refer to indigenous and non-indigenous people that live within and/or around PAs.

Revenue is usually understood to be gross income rather than net income after the deduction of costs (Franks and Twinamatsiko, 2017). The revenue shared may be in the form of cash payments but is usually disbursed in the form of small grants for selected projects. These may be projects for individual community members (i.e., micro-enterprises, school bursaries) or group projects that benefit part or all of the community (i.e., support for school infrastructure, road repair / development, or clinics).

Despite the benefits of revenue-sharing from PA tourism, there are also numerous challenges. Spenceley (2014) identified six key challenges with benefit-sharing from PAs, several of which were identified during this study as well. These include: (1) the value of money per person is small if divided among a large number of people; (2) benefits of social infrastructure (e.g., schools, water, infrastructure) are not always associated with the conservation or tourism; (3) those who benefit are not necessarily the same as those who experience the costs of conservation, [e.g., human-wildlife conflict (HWC) and loss of access to land)]; (4) poorest residents are often not the beneficiaries; (5) community entities may not have the capacity to partner with other stakeholders or to agree on benefit-sharing processes; and (6) legislation may constrain benefit-sharing processes (adapted from Spenceley, 2014).

Uganda and Rwanda are the only countries in Africa to have formal tourism-revenue sharing (TRS) policies that prescribe a specific amount to be shared. Research has been conducted (Ahebwa et al., 2012; Tumusiime and Vedeld, 2012; Franks and Twinamatsiko, 2017; Twinamatsiko et al., 2018; Kambagira, 2019) on the tourism revenue-sharing programme (TRSP) in Uganda and has highlighted various challenges as well as benefits from the programme. The majority of the research either focused on one national park or community, rather than the TRSP as a whole. Similarly in Rwanda, research (Imanishimwe et al., 2019; Mananura and Sabuhuro, 2020) has also been conducted on various elements of the TRSP, but the last full programme assessment was done in 2017, with a focus on Volcanoes National Park, rather than an overall longitudinal analysis of the TRSP across all national parks and including all major stakeholders. This study fills this gap as it assesses the TRSP over a 15-year period and included consultations with relevant stakeholders related to the three national parks receiving benefits over this period. The goal was to provide an updated comprehensive review of the whole TRSP in Rwanda and to provide policy- and practice-relevant recommendations, many of which could be incorporated into the Uganda TRSP as well as used to inform the development of other TRSPs globally. This study was requested by the Government of Rwanda because as a result of a recently declared a recently declared new protected area, they sought this opportunity to assess the programme, to-date and from there to determine how to adapt and amend the TRS policy to incorporate the new park and to meet the overall TRSP objectives as set out in the TRS Policy.

History of tourism revenue sharing in Rwanda

Rwanda's earliest form of benefit sharing was an informal model that dates back to the 1950s when the Belgians sought to increase cooperation with local communities bordering national game reserves by providing meat from problem animals (Phiona and Jaya, 2015). Over the next five decades, benefit sharing programmes evolved across the country. In 2004, the Office Rwandais du Tourisme et des Parcs Nationaux (ORTPN) (now the Rwanda Development Board, RDB) allocated RWF 42 million (approx. US$ 75,000) from revenue generated in 2003 to the districts bordering the three NPs in the ratio of: 50% for Volcanoes National Park; 25% for Akagera National Park; and 25% for Nyungwe National Park. For this allocation, the district offices, guided by their specific district priorities, led in identifying which projects to fund [Rwanda Development Board (RDB), 2016, 2017a,b].

In October 2005, ORTPN formalized a TRSP that allocated 5% of the total revenue generated from three national parks (Akagera, Nyungwe and Volcanoes) to communities located in the areas surrounding the parks [Rwanda Wildlife Authority (RWA), 2005].

When the Government of Rwanda (GoR) created its fourth national park, the Gishwati-Mukura National Park in 2015 [Government of Rwanda (GoR), 2016], RDB expanded the TRS Policy to incorporate this new national parks in the TRSP. RDB also changed the TRS Policy in 2017 when they increased the Volcanoes National Park mountain gorilla trekking permit fee from US$ 750 to US$ 1,500. As a result of this increase, they also doubled the percentage of revenue allocated to the TRSP from 5 to 10% [Rwanda Development Board (RDB), 2017a]. The 10% of pooled revenue from the national parks is now allocated according to the following ratio: 35%, Volcanoes National Park; 25%, Akagera National Park; 25%, Nyungwe National Park; and 15%, Gishwati-Mukura National Park. The GoR allocates an additional 5% of revenue to a HWC fund, which this study did not assess. The HWC fund is allocated for compensation due to HWC and is managed separately and not by RDB. Overall, within the zone of influence, the TRSP covers 14 districts and 51 sectors around the four NPs, with a total population of 1.4 million, with the largest population around Nyungwe National Park (538,000), followed by Volcanoes National Park (330,000), Akagera National Park (324,000); and Gishwati-Mukura National Park (21,500) [Rwanda: Division in Sectors, 2017; Rwanda Development Board (RDB), 2020].

The goal of the TRSP is to ensure sustainable conservation of the national parks by engaging the neighboring communities and contributing to the improvement of their lives. The TRSP outlines three impact objectives [Rwanda Wildlife Authority (RWA), 2005], (i) Conservation impact objectives, which include to reduce illegal activities; ensure sustainable conservation; and increase community responsibility for conservation; (ii) livelihood impact objectives, to improve livelihoods by contributing to poverty reduction; to compensate for loss of access and/or crop damage; to provide alternatives to park resources; and encourage community-based tourism and (iii) relationship impact objectives (between national parks and the local population), to build trust; increase ownership reduce conflicts increase participation in conservation; and to empower communities.

Given the creation of the fourth NP in Rwanda and the increase in revenue-sharing from 5 to 10%, RDB is updating the TRS Policy to reflect the current situation and to enhance its impact. To adequately assess how best to revise the TRS Policy and related TRSP to create positive impact, RDB commissioned this study to review the impact of the TRSP over the last 15 years, including relevant stakeholder inputs, and to provide recommendations for improving impact.

Methods used in the research

The study utilized three data collection methods: desk research; field surveys in the three focal areas; and electronic and telephonic interviews of key stakeholders (physical meetings were not feasible due to COVID-19 restrictions). These methods were selected as the most comprehensive to ensure that relevant stakeholders were consulted to provide inputs into the review and to incorporate pertinent literature and prior assessments. The identification of key stakeholders was done in collaboration with RDB and the International Gorilla Conservation Programme (IGCP), who funded this research, to ensure that, to the extent possible, relevant stakeholders were included. A broader in-person stakeholder validation workshop was held on 18 May 2022 in Kigali, Rwanda where the results were presented and validated by 46 stakeholders, representing different districts, sectors, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and national government. A presentation of the results was done virtually by the lead author at the workshop and discussions were held regarding the recommendations, which were then revised and validated by the stakeholders.

For the desk-based research, the three main objectives were (i) to inform the data collection process as the desk research provided insights on prior TRSP assessments and identified the information gaps to be addressed during the data collection process; (ii) to understand key lessons learned, which was done through reviewing existing papers, reviews and assessments to help inform the team on challenges and opportunities of the TRSP, areas of impact, and barriers to success; and (iii) to provide examples of best practices of TRSPs from around the world, which was based on the desktop analysis, which assessed global models that RDB may want to consider with specific examples of positive impacts, challenges, and best practices in terms of the effectiveness and impact of the TRSP.

Non-exhaustive sources of information for the desk review included the following: publicly available publications, reports, and audits of the TRSP; key word searches in academic databases; documents provided by the RDB and IGCP; and relevant studies conducted and reports on TRSP developed by Conservation Capital (CC) and the African Leadership University (ALU).

Questionnaires where used to gather data in the communities surrounding the three focal NPs. The questionnaire was developed to determine level of awareness, views and perceptions of the TRSP benefits, challenges and opportunities for the future and data was specifically collected on the TRSP impacts; TRSP project selection; and TRSP project implementation.

The survey was designed to collect data from various stakeholder groups. These included: (i) the TRSP beneficiaries, which included individual cooperative and non-cooperative members; (ii) TRSP management and implementation stakeholders; and (iii) TRSP partners, including government, donors, NGOs.

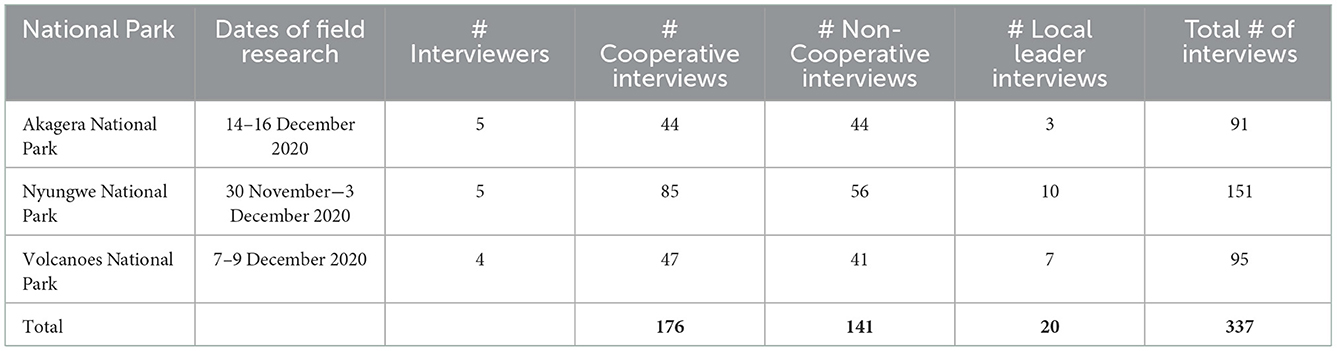

For the field interviews, administrative and logistical support was received from the IGCP and RDB and was conducted by the ALU from 30 November to 16 December 2020, with separate field trips to each of the three NPs. Gishwati-Mukura National Park was not included in the field research due to its recent inclusion in the TRSP: therefore, no disbursements having been done at the time of the research. Four ALU students, trained by the ALU School of Wildlife Conservation (SOWC), conducted the interviews, with support from the SOWC Director of Research at Nyungwe and an ALU SOWC faculty member at Akagera National Park. A distinction was made between cooperative [“cooperatives are farms, businesses or other organizations, owned and run jointly by its members, who share the profits or benefits” (Republic of Rwanda, 2018)] and non-cooperative members as the TRSP only gives programme funds through cooperatives (local community members pay a small fee to be a member of a cooperative), as we wanted to determine if there were any differences in awareness and/or attitudes toward the TRSP and related conservation between those benefitting and those not directly benefitting. Local leaders around each of the NPs were also interviewed to provide an understanding of local leader attitudes to, and awareness of, the TRSP. See Table 1 for the interview schedule details.

For the electronic questionnaire, the team used a similar questionnaire as the field interviews, which was uploaded onto a google platform. Participants from NGOs, private sector and government were invited to complete the survey. In addition, the team held telephonic interviews with key stakeholders. The online survey was shared with a total of 15 stakeholders of which 11 responded (73% response rate).

For the telephonic interviews, 12 were conducted (57% response rate) with a variety of stakeholders, including local and national government, conservation NGOs and private sector tourism operators.

The field research data, as well as the online survey and telephonic interview data was collated and analyzed in Excel, using descriptive statistics to calculate, describe, and summarize the collected data in the most efficient way.

Results

The results are presented according to the different data collection methods used: (i) the desk review of how the TRSP funds have been allocated to-date and a review of past TRSP studies; (ii) the community interview results (including the local leader interview results); (iii) the online questionnaire results; and (iv) the telephonic interviews results. The online questionanarie and telephonic interview results were aggregated as they used the same questionnaire. The themes in the results section were selected to align with previous TRSP assessments done in Rwanda to allow for comparison if required.

Overview of the tourism revenue sharing programme funds to-date

Since its inception in 2005, the TRSP has invested RWF 5.8 billion (US$ 5.6 million)1 in projects surrounding the four national parks. Volcanoes National Park, the largest contributor to the TRSP, saw the largest share of benefits with 41% of total project investment, with Akagera National Park, Nyungwe National Park, and Gishwati-Mukura National Park receiving 28, 26, and 5%2, respectively [Rwanda Development Board (RDB), 2020].

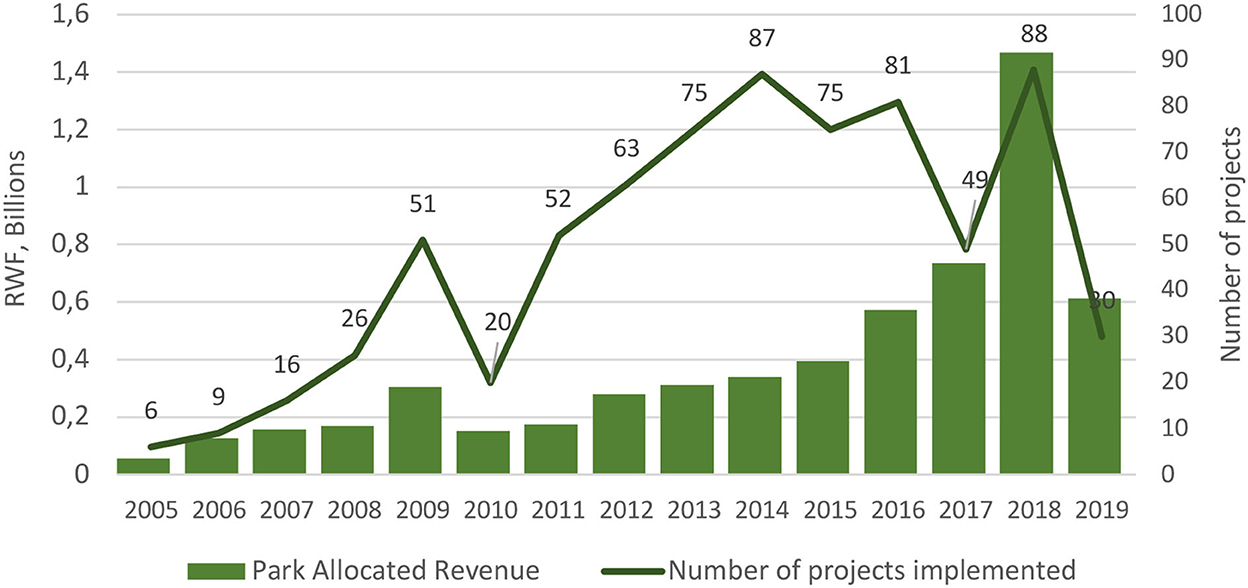

The number of projects supported by the TRSP has increased over the years, starting from five projects in 2005, and reaching an average of 65 projects per year between 2015 and 2019 (see Figure 1). The spike in project funding from 2017 to 2018 is related to the doubling of TRSP allocation from 5 to 10%, which corresponded with the increase in gorilla trekking fees from US$ 750 to US$ 1,500. This increase resulted in an increase in the average number of projects as well as in the budget made available per project. For example, the average project budget in 2015 was RWF 5.2 million (~US$ 5,000) (with 75 projects implemented); while in 2018, this number reached RWF 16.7 million (~US$ 16,100) (with 88 projects implemented). The 2019–2020 disbursement was impacted by COVID-19 and part of the allocation was used to purchase face masks for the community members around Volcanoes and Nyungwe NPs.

Figure 1. Number of projects implemented through the TRSP per year from 2005 to 2019. RDB data, 2005–2019.

Projects funded by the TRSP fell into four major categories: infrastructure projects (80%); agriculture (15%); equipment purchase (2%); HWC (2%) and enterprise (1%).

Among the infrastructure projects, the largest allocation of funds went toward education projects (38% of all infrastructure projects), followed by housing (13%) and water supply (9%). The funded agricultural projects focused mostly on crop production and livestock (72% of all agricultural projects).

HWC support included mainly infrastructure support to prevent wildlife encroachment, such as a buffalo fence or a trench. The equipment purchase included items to support community development and livelihoods, such as milk and cassava processing plant equipment, sewing machines for local businesses, tannery equipment, carpentry equipment and transportation.

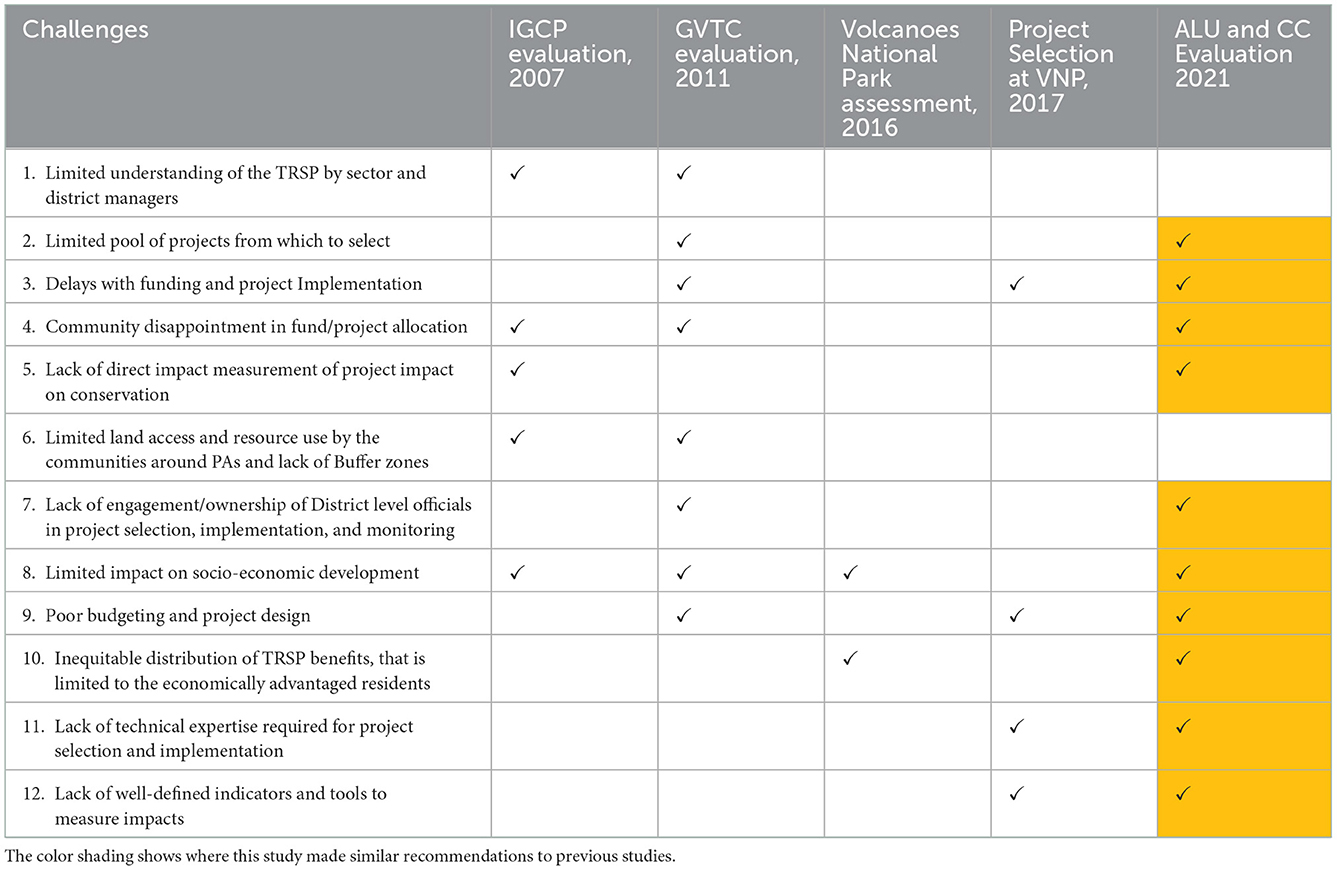

Desk review of prior studies

This study reviewed three prior assessments of Rwanda's TRSP [International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP), 2007; Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration (GVTC), 2011; Volcanoes National Park et al., 2015] and notes from a TRSP project selection meeting held at Volcanoes National Park. The challenges highlighted in the prior studies were reviewed and compared to the findings in this study (see Table 2).

RDB has implemented several measures to meet some of the challenges (e.g., development of a new TRS Policy in 2020), however the results of the current assessment showed that a number of the challenges identified in prior studies remain.

Community interview results

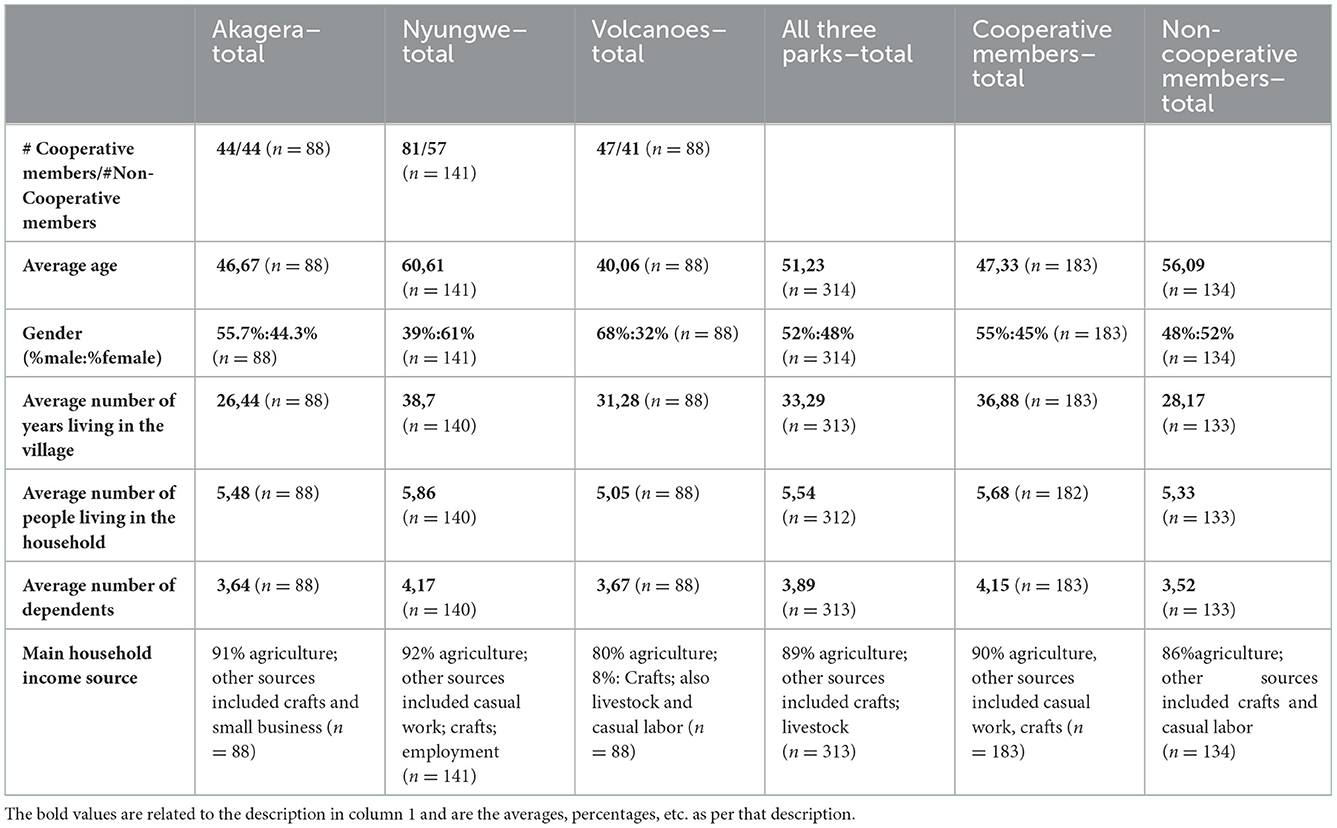

The community interview results are presented per NP, aggregated for all three NPs together, and then broken down between cooperative and non-cooperative members to provide a complete analysis of the different groups interviewed.

Demographic data

Table 3 shows the demographic information of participants in the field research, showing an average age of all those surveyed as 51.23 years, with 52% of respondents being male and 48% female. The main household income source for all participants was agriculture.

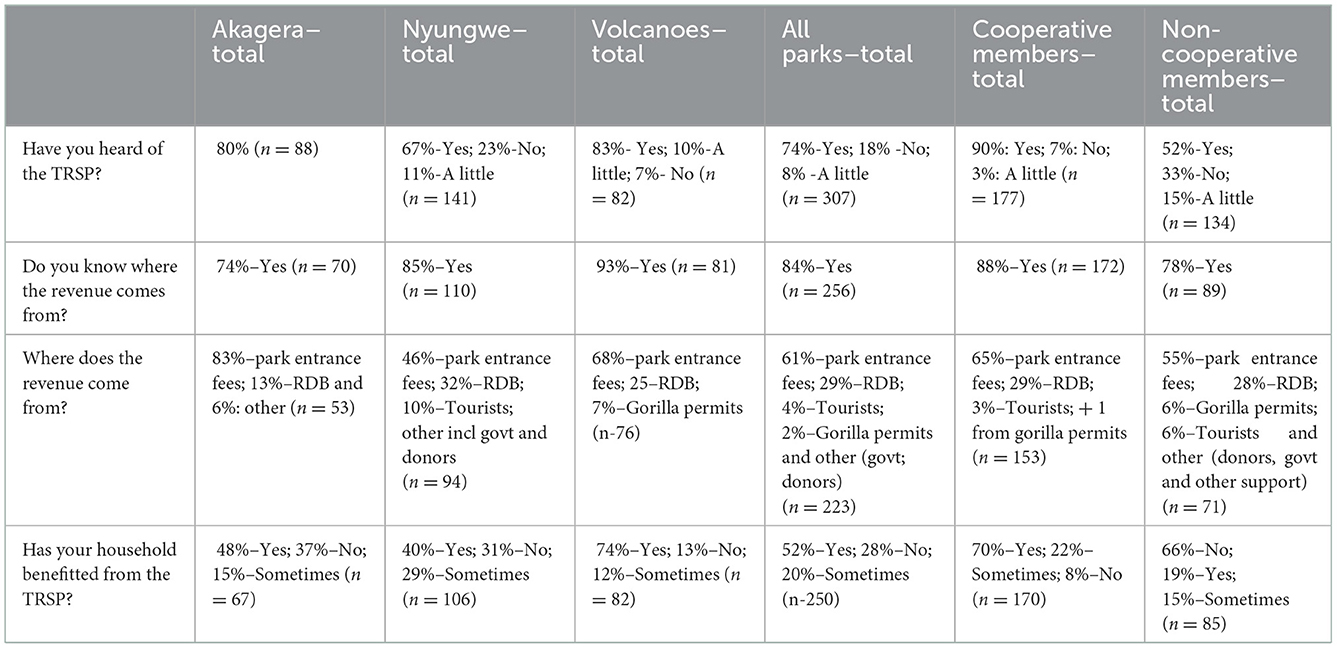

Awareness of TRSP

Table 4 presents results related to the awareness of the TRSP. As shown, an average of 74% of all respondents across the three NPs were aware of the TRSP, with Volcanoes National Park respondents having the highest awareness (83% of respondents had heard of the TRSP). This is likely because Volcanoes National Park, home to the mountain gorilla, has the largest number of international tourists with the highest revenues from gorilla permits and several visible TRSP projects conducted in the local community. The majority of participants (84%) said that they know where the revenue for the TRSP comes from, with cooperative members, in general, having greater awareness than non-cooperative members. When asked where the revenue comes from, some respondents said that it was from RDB rather than from tourism specifically, though the majority were aware of the connection to the NP and related tourism. Fifty-two percent of respondents said that their household had benefitted at some stage from the TRSP, with 74% of cooperative members saying they have benefitted while only 19% of non-cooperatives said so they had.

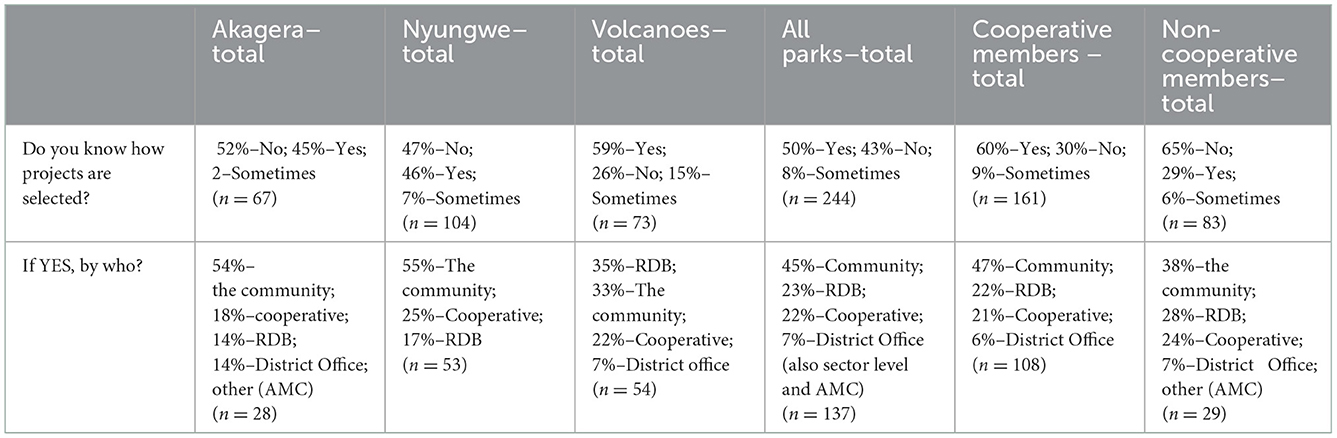

Awareness of the project selection process

Fifty percent (50%) of the total respondents knew how TRSP projects were selected for funding, with Volcanoes National Park having the highest percentage (59%) (Table 5). Forty five percent (45%) of community respondents said that the community were involved in the selection process, even among the cooperative respondents the percentage was less than half (47%).

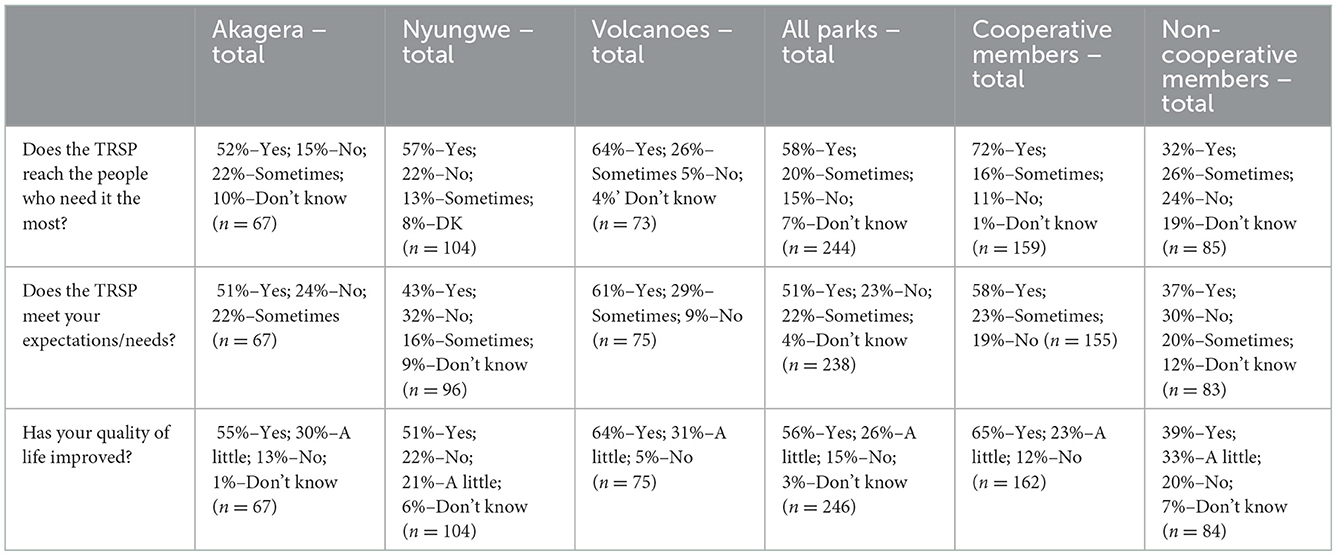

TRSP project assessment

Table 6 presents an overview of respondents' assessment of the projects implemented with the TRSP funds. Fifty eight percent of all respondents felt that the TRSP funds reach the people who need it the most, though only 32% of the non-cooperative respondents felt so, compared to 72% of cooperative members. In terms of expectations, 51% of all respondents felt that the TRSP meets their needs/expectations: 58% for cooperative members and 37% for non-cooperative members. Fifty six percent of all respondents felt that their quality of life had improved as a result of the TRSP, whereas 65% of cooperative members felt that their quality of life had improved and 39% for non-cooperative members.

Satisfaction with the TRSP

Overall, 57% of respondents across all the NPs were satisfied with the TRSP; with 23% being very satisfied and 19% dissatisfied. Cooperative members (89%), who received the funds for projects, were generally more satisfied with the TRSP than non-cooperative members (63%). Overall, Nyungwe National Park had the highest number of participants who were satisfied (65%), followed by Volcanoes National Park (53%), then Akagera National Park (49%).

Eighty four percent of all community respondents felt that the TRSP has increased community support for conservation, while 95% of the respondents at Volcanoes National Park reported that it does.

Local leader interview results

The field research team also interviewed local leaders involved in the implementation of the TRSP to gain insights into their perspectives of the programme in terms of implementation and impacts on the livelihoods and attitudes of the local community.

Ninety five percent of the respondents were male (20 respondents in total, one female) and their roles in the TRSP were broken down as below, with the average number of years per respondent working in the TRSP being 7.16 years:

55%—Administration.

15%—Reviewer of proposals.

10%—Implementation of projects.

10%—Monitoring.

10%—Selection.

Respondents said that the main TRSP projects implemented were crop damage compensation and prevention measures and that the projects were developed by the cooperatives (68%), RDB (16%) and the community (11%). Given that the TRSP is different to the HWC fund, which supports crop damage compensation, it is clear that respondents were not aware of the difference, illustrating a lack of awareness of the objectives of the TRSP.

In terms of whether the TRSP projects have been developed on time, 32% said that they always were; 32% said sometimes; 21% frequently and 16% said that they were not developed on time. Forty seven percent of respondents said that the TRSP projects were developed as per the proposals/plans submitted, with 32% saying that they sometimes were and 16% saying that they frequently were. The main reasons indicated by respondents for projects not been developed according to the plan were a lack of financing and delayed financing.

Sixty one percent of respondents said that the community were always involved in the project selection process, while 22% and 11% reported being frequently or sometimes involved, respectively. Respondents who said that the community are involved said that they are involved mostly through choosing the project to submit and writing the proposal for the project, not in the decision-making in terms of project selection.

Sixty eight percent of respondents felt that the TRSP always reached the people who needed it the most, with 16% saying it frequently does, 16% saying it sometimes does and 11% saying that it does not. Seventy four percent of respondents said that information on the implementation process is communicated with the community. In terms of the TRSP projects corresponding to community needs/expectations: 55% of respondents said they do; 25% said that they sometimes do and 20% said that they do not. Eighty nine percent of respondents said that they think that the TRSP projects increase community support for conservation.

In terms of TRSP projects leveraging additional funding, 37% said that they sometimes do, 32% said that they do, 16% said that they do not and 16% said that they do not know. Respondents said that leveraged funding usually came from national (sometimes local) government and that it was mostly education projects, which leveraged additional funding, as well as conservation and HWC mitigation projects.

Fifty nine percent of respondents felt that the TRSP funding does not replace government funding, but 29% felt that it does and 12% did not know.

Respondents said the main successes of the TRSP are related to employment and infrastructure and the main challenges of the TRSP were that the proposals were not good enough; there were issues with implementation; there was a lack of connection to conservation; and the process for selecting projects wasn't always clear.

Overall, 53% of respondents were satisfied with the TRSP; 37% very satisfied and 11% dissatisfied.

Interview and online survey results

This section presents the results from the telephonic interviews and the online survey summarizing respondents' impressions of the TRSP in terms of conservation, their awareness of the TRSP and its achievements. In this section the term ‘respondents' collectively refers to to NGOs, private sector partners and government representatives unless otherwise specified.

TRSP impact on conservation

While it is difficult to attribute the direct impact of the TRSP on conservation, the survey results reveal that interviewed stakeholders recognized the role of the TRSP in conservation efforts. Eight out of 11 (73%) respondents indicated that the TRSP always, frequently or sometimes played a role in decreasing illegal activities, and nine out of 11 (82%) indicated that always, frequently or sometimes TRSP-supported projects increased community support for conservation.

TRSP awareness

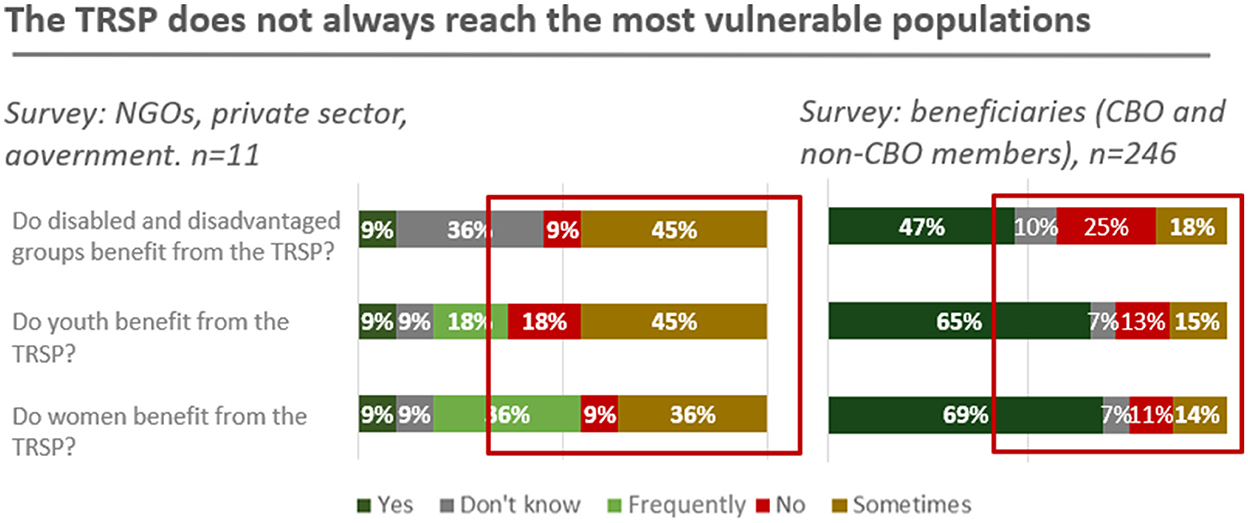

Half of the respondents indicated that disadvantaged, women, and youth either did not benefit at all or occasionally benefited from the TRSP (Figure 2).

TRSP achievements

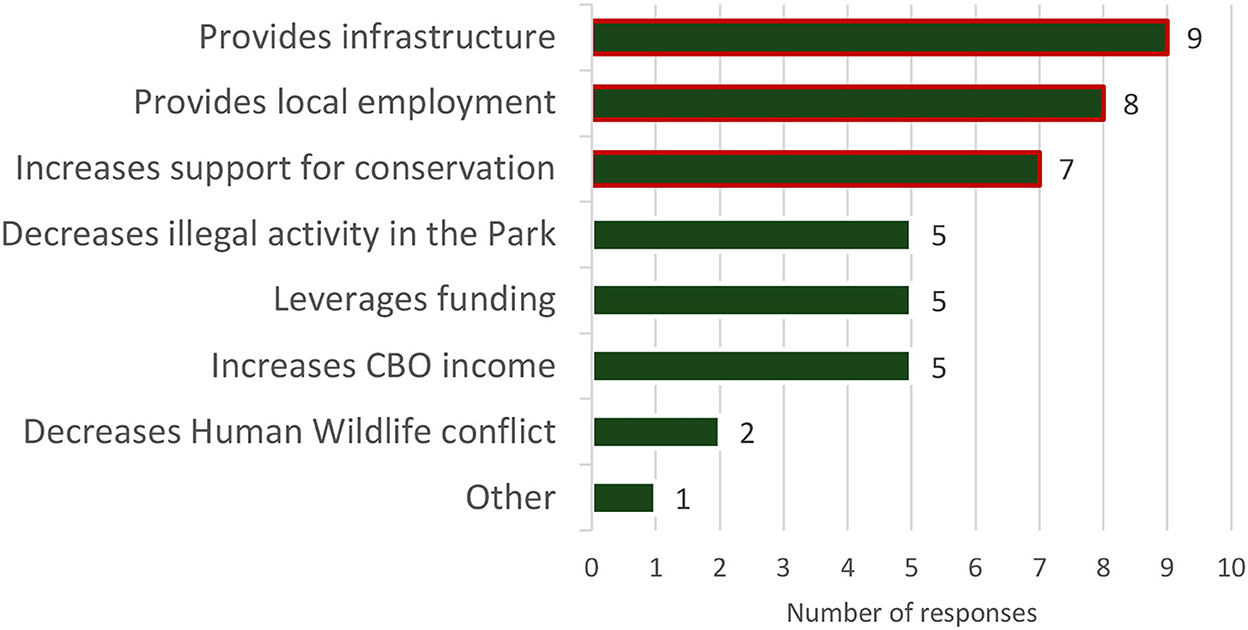

Partner organizations viewed the main achievements of the TRSP to be infrastructure development, employment creation, and conservation support (Figure 3).

Funding alignment with community needs

A majority (64%) of the respondents indicated that the TRSP sometimes meets community expectations and needs and 36% indicated that the programme frequently or always meets their needs.

TRSP challenges

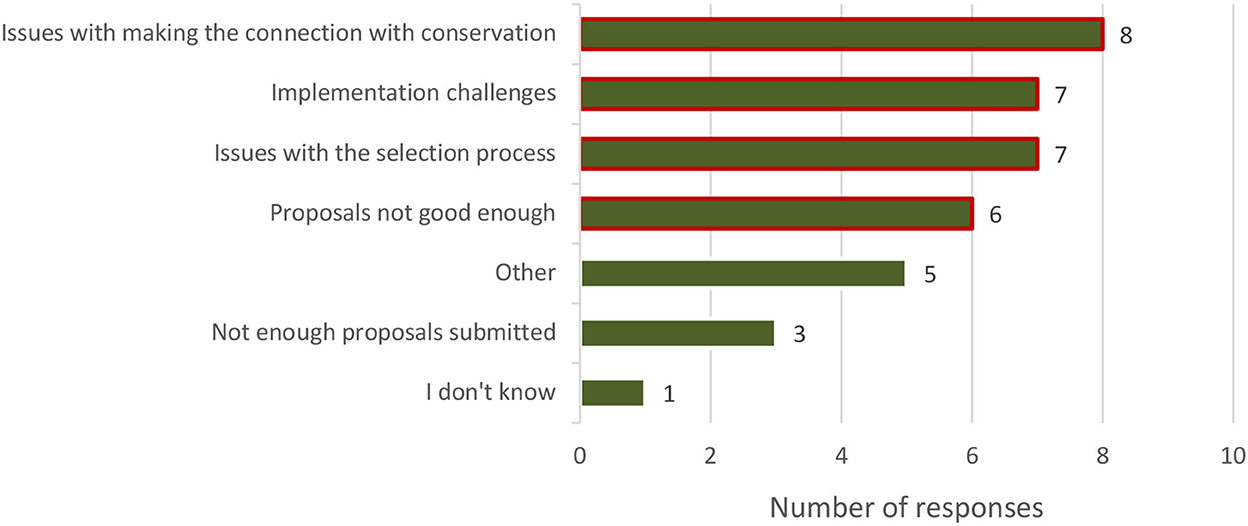

A majority (73%) of the respondents indicated the top four challenges of the TRSP are: making the connection between the TRSP and conservation; implementation challenges; issues with the selection process; and proposals not being good enough (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The main challenges of the TRSP highlighted by partner organizations. Survey NGOs, private sector and government representatives, n = 11.

Community involvement

When asked about community involvement in the TRSP, 45% of respondents think that communities are either not involved at all or involved on an irregular basis in project selection, with many feeling that project selection is determined by the district office.

Project selection transparency

Respondents indicated that there is a lack of overall clarity on the project selection process. Nine percent of the respondents said there is sometimes clarity and 27% said there is no clarity on the process for selecting projects. This is markedly different to the response from the communities, where 65% of non-cooperative members indicated that the process is not clear; whereas 60% of cooperative members indicated that the process is clear.

Monitoring of the TRSP projects

When asked whether the TRSP-selected project implementation progress is regularly monitored, 27% of the respondents indicated no and 27% indicated they did not know.

Stakeholders surveyed and interviewed attributed community support for conservation to the TRSP and its related benefits and stated that the TRSP has developed infrastructure and created jobs. However, they indicate that overall, the TRSP is not meeting the needs of the community and in particular those of the marginalized community members and non-cooperative members, and that there are challenges with implementation and proposal development. In addition, they indicate that the communities are not fully involved in the whole TRSP process.

Discussion

Only small differences existed between the community respondents and other stakeholders in their awareness of and satisfaction with the TRSP. Overall, the results highlight a general lack of awareness of how projects are selected and a perception that the community is not fully involved in the TRSP and that it is largely driven by the distrcit offices. This was similarly found by Tumusiime and Vedeld (2012) in their study on Uganda's TRSP where they found that there was no real local community participation. Interestingly, in our study partner organizations were less positive about the TRSP meeting community needs/expectations than the community members or the local leaders. More of the local leaders felt that the community were more involved in the selection process (61%) than the partner organization respondents (55%) and only 45% of the community respondents felt so. This indicates that the majority of the main target group—local communities—did not feel part of the selection process.

All groups, including 89% of the local leaders, 84% of community respondents, and 82% of the partner organizations, felt strongly that the TRSP has increased the community support for conservation. The overall percentage of local leader respondents who were satisfied with the TRSP (53%) is aligned with that of the community respondents (57%).

Many of the overall weaknesses identified by the various respondent groups have been previously identified in other studies [International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP), 2007; Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration (GVTC), 2011], particularly in terms of challenges in implementation and the impact on socio-economic development. The recommendations below are based on the results of the primary and secondary research conducted for this study, which were further confirmed by prior assessments. There are several recommendations put forward to improve the overall impact of the TRSP in Rwanda and to ensure a greater understanding of the impacts through better monitoring and evaluation of projects and where and how funds are being spent.

Over the past 15 years, the results of this and previous studies (Phiona and Jaya, 2015; Munanura et al., 2016) show that Rwanda's TRSP has met many of the programme's objectives, including creating support for conservation from local communities, generating awareness of conservation and the value of wildlife and PAs, building relationships between RDB and the communities, enhancing the lives of community members and developing infrastructure throughout the NP regions. Rwanda now has developed high quality infrastructure in the focal areas with strong support from local residents for conservation through the TRSP.

The main challenges identified in this study are effective community engagement, reaching the most vulnerable, and ensuring that the TRSP meets community needs. Having requested this study, the GoR is interested in adapting the TRS Policy to more effectively engage the communities living around the PAs in the TRSP and to allocate more funding to directly enhance the lives of Rwandan citizens living around PAs. We recommend that this can be done by involving communities more in the entire TRSP process, making the TRSP more accessible to all community members and allocating more funds to community development programmes proposed and selected by the communities themselves.

Based on the study's results, the following recommendations are made to enhance the TRSP and simultaneously support RDB's role as a leader in innovative community conservation. These recommendations can also be taken into consideration by other countries interested in developing and/or improving community engagement in, and benefits, from TRSPs.

i. Revise the revenue allocation model and eligibility to create resilience.

A majority of the TRSP revenue over the past 15 years has supported infrastructure development. A majority of the respondents consulted urged the GoR to rather allocate a majority of the TRSP revenue to livelihood development programmes. These programmes have the potential to enhance the resiliency of communities, create jobs, diversify revenue (reducing reliance directly on tourism, which is particularly important given the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic) and to garner further conservation support from the communities.

It is recommended that the following percentages be used for the revenue allocation going forward: 70% for livelihood projects; 25% for infrastructure support; and 5% in an emergency fund. Equipment would fall under either livelihood projects or infrastructure support, depending on the project. HWC compensation is already covered by the HWC fund. The emergency fund would be used during times of crisis, such as COVID-19, when tourism revenue is severely impacted. The use of the funds would be guided by the updated TRS Policy and the funds should go into an interest-bearing account managed by RDB. Once the funds reach US$ 150,000 (RWF 1.5 million), the 5% should be allocated to livelihood projects. This amount was calculated by doubling the average annual spend of the TRSP, to ensure that the TRSP would have enough funds for 2 years in a time of crisis. Should there not be a suitable number of livelihood projects proposed by the community, the balance of the funds could be allocated to infrastructure projects. If community members propose a livelihood project that includes infrastructure, such as a shop, this should be included under livelihood projects and not infrastructure.

The TRSP is currently limited to providing funding to cooperatives. Stakeholders indicated that this excludes the most vulnerable community members, as most cooperatives require a membership fee. It is, therefore, recommended that the selection criteria should include individual groups, if projects benefit more than 10 households, as well as NGOs working with and selected by the communities. Inclusion of the most vulnerable community members is a target in the existing TRS Policy and is likely to remain a focus for the GoR in the revised policy.

It is also recommended that proposals for community capacity building (which are not currently permissible) should also be permissible (see recommendation five).

ii. Clarify and create awareness around the TRSP process.

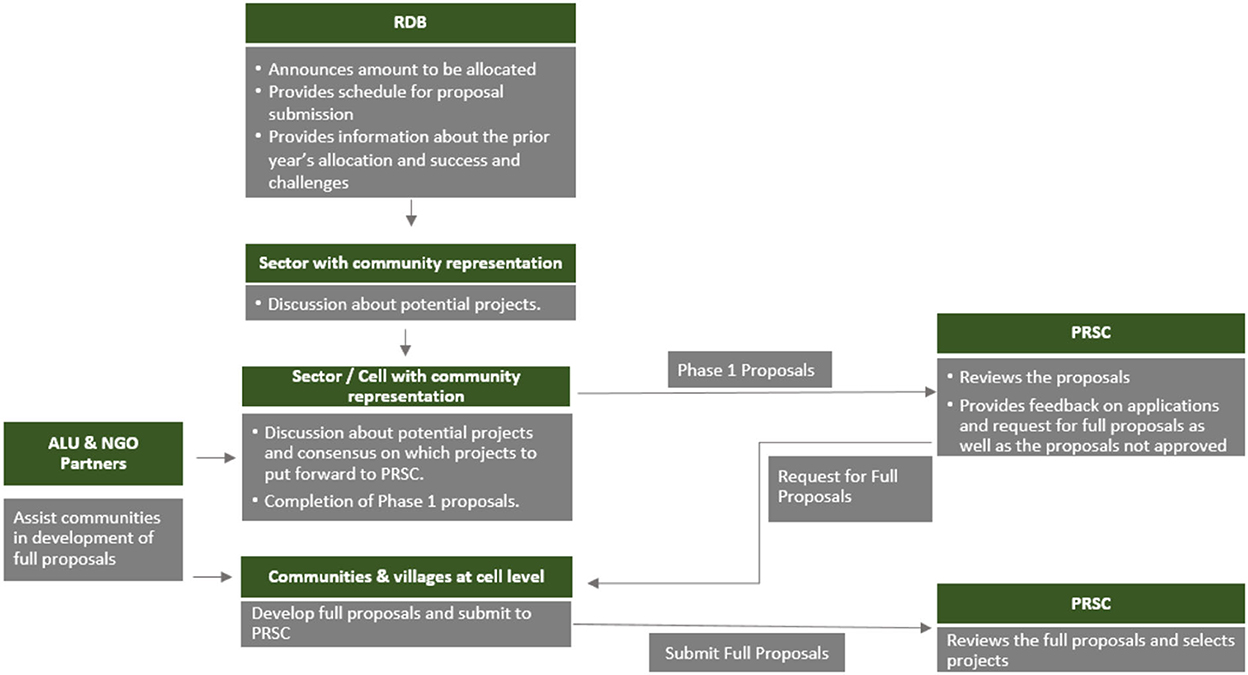

There was a general lack of clarity about the TRSP cycle and process, from identification and selection of potential projects to monitoring and evaluation. Stakeholders indicated that the District Offices ultimately decide which projects are selected, not the communities. The current selection process includes three key steps: (1) communities develop project proposals; (2) the District Technical Committee screens and short lists the proposals; and (3) Park Revenue Sharing Committee (PRSC) selects the projects [Rwanda Wildlife Authority (RWA), 2005]. The following are recommended:

a. Clarify the selection criteria used to select projects and make this public (and available in the local language) with clear definitions to avoid ambiguity and misinterpretation and to be accessible to to the entire population.

b. Develop and make accessible a programme schedule that makes it clear when proposals are due and when selection will take place. This should be the same every year to ensure consistency.

c. Publicize the list of the Park Revenue Sharing Committee members to create full transparency, accountability, and awareness.

d. Simplify the proposal submission procedure and adopt a two-step proposal process, which will make the application process more accessible and save time for the applicants as well as the reviewers:

• Step 1. Submission of a simple standard application form that is accessible to communities, which includes an option to request support for the full proposal if selected and if needed by the applicant; and

• Step 2. For those selected, a full proposal with standard template available, including a list of the required supporting documents.

e. A project awards ceremony would help launch projects and provide more visibility to the communities and relevant stakeholders on selected projects. This would also help create accountability for the project implementer.

iii. Enhance community involvement throughout the TRSP process.

It is recommended that the project selection process should be more inclusive of and engaging for local communities, who currently feel excluded from the process. The process should be initiated at the sector or cell level were projects would be deliberated by the community to determine collectively which proposals to submit; thus, ensuring community ownership for the decision. Communities should also be represented on the Park Revenue Sharing Committee; thus, part of the final vetting and selection process (see Figure 5). Decentralizing decision making and effectively engaging local communities in the process will build capacity as well as support for conservation.

iv. Enhance project execution.

Programme delays resulting from the flow of funding were reported as an issue for effectively and timeously implementing projects. The TRSP funding currently goes through the local government. To enhance efficiency, funding should be transferred directly to the implementing organizations and when needed, NGOs selected by the community, can serve as fiscal agents until capacity is developed.

Implementation can be done, if needed, by an NGO or the private sector (selected by the community) that has the required skills and expertise, and part of the process can be to build the capacity of the community organization.

v. Support capacity for communities, local government and RDB.

Lack of capacity and skills were identified in the qualitative comments as one of the major barriers for community participation, programme management and project implementation. Capacity building should be embedded into the entire TRSP process from supporting communities in the application process to project implementation and monitoring. NGOs and private sector partners operating in all the NP landscapes can help provide capacity support and help with implementation, which will help leverage other programmes in the area. In some cases, capacity building is needed for local government and staff working on the TRSP as well. The TRSP could be used to finance these capacity support programmes.

vi. Enhance monitoring and evaluation.

The capturing of data and information to better inform the TRSP, support adaptive management, and guide other PA revenue-sharing programmes in Africa and around the world is critical. While project verification procedures are stipulated in the TRS Policy, this is rarely followed due to a lack of capacity, and there is an overall lack of clarity on, and understanding of, the monitoring process among partner organizations and a lack of capacity for monitoring and evaluation (M&E). As a result, the following are recommended:

• At a minimum, there should be recruitment of one monitoring and evaluation senior officer fully dedicated to reviewing, monitoring, and reporting on the TRSP. This position could be financed through the TRSP.

• While ultimate responsibility and accountability rests with the monitoring and evaluation senior officer, he/she should develop a system for monitoring as well as relevant tools and should train and engage stakeholders in monitoring and evaluation. Monitoring smart phone platforms that community members can use for project planning, execution and monitoring could also be considered.

The aim of these recommendations is to ensure greater direct community involvement and overall stakeholder awareness and understanding of the TRSP as well as a greater connection between local communities to conservation resulting in greater support for conservation, pride in Rwanda's natural areas and improved livelihoods. In addition, with greater coordination with communities, private sector and NGOs, the TRSP can be used to leverage other funding and to use existing resources more efficiently.

Conclusion

Rwanda has one of the highest revenue sharing programmes, in terms of percentage revenue allocated to the programme, in Africa. Over the past 15 years, the TRSP has financed infrastructure, supported community livelihoods, and established a positive linkage to, and support for, conservation. Despite the TRSP having achieved positive results, various reviews have highlighted challenges with the programme. It was found in the secondary research for this study that many of the past recommendations to improve the TRSP have not been implemented and several of the same challenges exist. It is likely that this is due to the complexity of implementing many of the recommendations due to the diversity of stakeholders involved, lack of capacity within the government to implement recommendations, and the size of the beneficiary population. Although this study attempted to engage with as many relevant stakeholders as possible, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some limitations with access and in-person meetings.

Ultimately, given the vision of the TRSP (community support, conservation linkages, and relationship building with RDB), changes are recommended to ensure that the community are directly engaged in the TRSP, benefitting from it and seeing the linkages between it and the related conservation. A number of the challenges faced by the Rwanda TRSP are similarly faced by other country TRSPs, highlighting that tourism-revenue sharing is complex, with a diversity of stakeholders and dependent on an industry that has also been shown to be volatile and vulnerable to shocks. The recommendations in this study have, therefore, also sought to build greater resilience in the TRSP and to reduce long-term risks. The commissioning of this study by the GoR demonstrates a keen interest in understanding the challenges and how to improve the TRSP, which is a critical first step. Incorporating communities into the entire TRSP process, allocating more revenue to community livelihoods than infrastructure projects, embedding capacity building into the programme and supporting monitoring and evaluation will further enhance the TRSP and help achieve its goals, which will support Rwanda's ambitious conservation and community goals.

As Gishwati-Mukura National Park was only added to the TRSP in 2019, it was not included in the field research as it will take time for the impacts of the TRSP to be felt. It is, therefore, recommended that baseline field research be conducted around Gishwati-Mukura National Park as soon as possible to measure the impacts of the TRSP more accurately over time. This will provide an opportunity to directly assess the impact of the TRSP before and after funds have been distributed. More detailed research on poverty level indicators should also be included in annual monitoring of the TRSP in order to have updated, robust data on impacts, rather than focusing on outputs and outcomes of the TRSP.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data was collected for the government of Rwanda, so we would need to get their permission to share if requested. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to SS, c3NueW1hbkBhbHVlZHVjYXRpb24uY29t.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SS and KF conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data, contributed data or analysis tools, performed the analysis, and wrote the paper. AB collected the data, contributed data or analysis tools, and performed the analysis. BM and TN conceived and designed the analysis and provided logistical support. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding for this research was received from the International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP) for funding this research and to the Rwanda Development Board for their support with collating documents and identifying stakeholders. Thank you to all the public, private, NGO and community participants who engaged in the surveys and consultations and also to the ALU SOWC students who conducted the community interviews around the three national parks.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^As of 27 April 2022 exchange rate. https://www1.oanda.com/.

2. ^Gishwati-Mukura was integrated into the TRSP in 2019.

References

Ahebwa, W. M., van der Duim, R., Sandbrook, C. (2012). Tourism revenue sharing policy at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda: A policy arrangements approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 20, 377–394. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.622768

Dewu, S., Røskaft, E. (2018). Community attitudes towards protected areas: Insights from Ghana. Oryx 52, 489–496. doi: 10.1017/S0030605316001101

Franks, P., Twinamatsiko, M. (2017). Lessons Learnt from 20 Years of Revenue Sharing at Bwindi Impenetrable. IIED report. Available online at: http://pubs.iied.org/17612IIED

Government of Rwanda (GoR). (2016). ‘Law No45/2015 OF 15/10/2015 Establishing the Gishwati-Mukura national park', Official Gazette n° 05 of 01/02/2016, 104-108. Government of Rwanda (GoR) 2016 - Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda.

Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration (GVTC). (2011). Assessment of the Performance of the Revenue Sharing Programme During 2005-2010. Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration (GVTC), Kigali, Rwanda.

Imanishimwe, A., Niyonzima, T., Nsabimana, D. (2019). Comparing the community dependence on natural resources in Nyungwe National Park and the contribution of revenue sharing through integrated conservation and development projects. Afr. J. Online 2. doi: 10.4314/rjeste.v2i1.9

International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP). (2007). Evaluation des projets financés par les revenus issus du tourisme. International Gorilla Conservation Programme, Kigali, Rwanda

Kaaya, E., Chapman, M. (2017). Micro-credit and community wildlife management: complementary strategies to improve conservation outcomes in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Environ. Manage. 60, 464–475. doi: 10.1007/s00267-017-0856-x

Kambagira, A. (2019). Tourism resource distribution and development in Uganda. A case of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (Ph. D. dissertation). Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda.

Kihima, B. O., Musila, P. M. (2019). Extent of community participation in tourism development in conservation areas: A case study of Mwaluganje Conservancy. Parks 25, 47–56. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2019.PARKS-25-2BOK.en

Lindsey, P., Allan, J., Brehony, P., Dickman, A., Robson, A., Begg, C., et al. (2020). Conserving Africa's wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1300–1310. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6

Mananura, I. E., Sabuhuro, E. (2020). “The potential of tourism revenue sharing policy to benefit conservation in Rwanda,” in Routledge Handbook of Tourism in Africa. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Munanura, I. E., Backman, K. F., Hallo, J. C., Powell, R. B. (2016). Perceptions of tourism revenue sharing impacts on volcanoes national park, rwanda: a sustainable livelihoods framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 24, 1709–1726. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1145228

Phiona, K., Jaya, N. E. (2015). The effectiveness of rwanda development board tourism revenue sharing program towards local community socioeconomic development: a case study of Nyungwe National Park. Eur. J. Hospital. Tour. Res. 3, 47–63. Available online at: http://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/The-effectiveness-of-Rwanda-Development-Board-tourism-revenue-sharing-program-towards-local-community-socio-economic-development.pdf

Republic of Rwanda (2018). Ministry of Trade and Industry, National Policy on Cooperatives in Rwanda: “Toward Private Cooperative Enterprises and Business Entities for Socio-Economic Transformation”. Available online at: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/rwa193693.pdf (accessed on September 2, 2021).

Rwanda Development Board (RDB). (2017a). Increase of Gorilla Permit Tariffs | Official Rwanda Development Board (RDB) Website. Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda. Available online at: https://rdb.rw/increase-of-gorilla-permit-tariffs/ (accessed on December 2, 2020).

Rwanda Development Board (RDB). (2020). Tourism Revenue Sharing in Rwanda: Policy and Guidelines. Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda.

Rwanda Development Board (RDB). (2016). Revenue Sharing 2016–2017: Projects' Selection Report. Musanze.

Rwanda Development Board (RDB). (2017b). Revenue Sharing 2017–2018: Projects' Selection Report. Musanze.

Rwanda Wildlife Authority (RWA). (2005). Tourism Revenue Sharing in Rwanda-Provisional Policy and Guidelines. Office Rwandais du Tourisme et des Parcs Nationaux, Kigali, Rwanda.

Rwanda: Division in Sectors (2017). Available at https://www.citypopulation.de/en/rwanda/sector/admin/ (accessed on January 14, 2021).

Snyman, S., Bricker, K. S. (2019). Living on the edge: benefit sharing from protected area tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 705–719. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2019.1615496

Snyman, S., Spenceley, A. (2019). Private Sector Tourism in Conservation Areas in Africa. Wallingford, Oxfordshire: CABI, Oxford.

Spenceley, A. (2014). Tourism Concession Guidelines for Transfrontier Conservation Areas in SADC. Report to GIZ/SADC. Retrieved from https://tfcaportal.org/sites/default/files/public-docs/tourism_concession_guidelines_sadc_tfcas_final.pdf (accessed on May 12, 2020).

Spenceley, A., Snyman, S., Rylance, A. (2017). Revenue sharing from tourism in terrestrial African protected areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1401632

Störmer, N., Weaver, L. C., Stuart-Hill, G., Diggle, R. W., Naidoo, R. (2019). Investigating the effects of community-based conservation on attitudes towards wildlife in Namibia. Biol. Conserv. 233, 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.02.033

Tumusiime, D. M., Vedeld, P. (2012). False Promise or false premise? Using tourism revenue sharing to promote conservation and poverty reduction in Uganda. Conserv. Soc. 10, 15–28. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.92189

Twinamatsiko, M., Baker, J., Franks, P., Infield, M., Olsthoorn, F., Roe, D. (2018). An Overview of Integrated Conservation and Development in Uganda. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. Available online at: https://www.google.com/search?q=London&stick=H4sIAAAAAAAAAOPgE-LUz9U3ME4xzStW4gAxTbIKcrRUs5Ot9POL0hPzMqsSSzLz81A4Vmn5pXkpqSmLWNl88vNS8vN2sDLuYmfiYAAALM0efE8AAAA&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiQ6O_0por8AhWVnnIEHYSyAxEQmxMoAHoECGEQAg

Volcanoes National Park Rwanda Development Board, and Janvier, K. (2015). Revenue Sharing Projects-Selection, Exercise 2015: The Minutes of the Workshop. Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda.

Walpole, M. J., Thouless, C. R. (2005). “Increasing the value of wildlife through non-consumptive use? Deconstructing the myths of ecotourism and community-based tourism in the tropics” in People and Wildlife: Conflict or Coexistence?, eds. R. Woodroffe, S. Thirgood, A. Rabinowitz (2005). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 122–139.

Wunder, S. (2000). Ecotourism and economic incentives—an empirical approach. Ecol. Econ. 32, 465–479. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00119-6

Keywords: tourism, protected areas, revenue-sharing, conservation, development, Rwanda, local communities

Citation: Snyman S, Fitzgerald K, Bakteeva A, Ngoga T and Mugabukomeye B (2023) Benefit-sharing from protected area tourism: A 15-year review of the Rwanda tourism revenue sharing programme. Front. Sustain. Tour. 1:1052052. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2022.1052052

Received: 23 September 2022; Accepted: 19 December 2022;

Published: 03 February 2023.

Edited by:

Jinyang Deng, West Virginia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kevin Mearns, University of South Africa, South AfricaMoren Tibabo Stone, University of Botswana, Botswana

Copyright © 2023 Snyman, Fitzgerald, Bakteeva, Ngoga and Mugabukomeye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susan (Sue) Snyman,  c3NueW1hbkBhbHVlZHVjYXRpb24uY29t

c3NueW1hbkBhbHVlZHVjYXRpb24uY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Susan (Sue) Snyman

Susan (Sue) Snyman Kathleen Fitzgerald

Kathleen Fitzgerald Anastasiya Bakteeva3†

Anastasiya Bakteeva3† Benjamin Mugabukomeye

Benjamin Mugabukomeye