94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Resour. Manag. , 31 March 2025

Sec. Safe and Just Resource Management

Volume 4 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsrma.2025.1543829

Introduction: Compulsory land acquisitions are commonly employed by many countries to serve broader public interests. Despite this, such acquisitions frequently lead to conflicts relating to compensation, transparency, and legitimacy of the public purpose. An understanding of stakeholder perspectives and framing strategies surrounding these acquisitions is essential to effectively address the resulting conflicts. This study investigates stakeholder perceptions and framing strategies underpinning the prolonged conflict resulting from Ghana's compulsory acquisition of land in 1965 for the construction of the Barekese dam.

Methods: The research employed a qualitative methodology involving key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and field observations. Data were analyzed through thematic analysis using NVivo software.

Results: Four primary conflict frames were identified: delayed crop compensation, unmet government promises, property destruction, and inaccurate documentation. Local communities emphasized themes of injustice, neglect, and betrayal, while government officials highlighted administrative and legal complexities. These incompatible frames have intensified mistrust and hindered effective conflict resolution.

Discussion: The findings indicate that divergent stakeholder perceptions and frames significantly impede constructive dialogue. Policymakers and practitioners should facilitate inclusive dialogue processes capable of reconciling these conflicting frames, thereby promoting more equitable and sustainable conflict resolutions.

In many economies around the world, the state has the authority to compulsorily acquire private property for purposes deemed to be in the public interest or for the common good, provided that just compensation is rendered to affected owners (Tran, 2024). This legal mechanism, known as compulsory acquisition or eminent domain, underscores the supremacy of state interests over individual property rights (Tran, 2024; Ewusie et al., 2024). Such powers enable governments to access, control and manage land in various tenure systems, facilitating the development of infrastructure, public utilities, and other projects considered necessary for national development (Okoth-Ogendo, 2000). Although this is intended to serve the broader public interest, the process often ignites conflicts and disputes. Common grievances include perceived injustices in compensation, lack of transparency in the acquisition process, inadequate consultation with affected communities, and skepticism about the legitimacy of the purported public purpose (Akrofi and Whittal, 2013; Tran, 2024). These conflicts are particularly pronounced in contexts where land has a significant cultural, economic, and social value, and where traditional land tenure systems coexist with formal statutory laws (Tran, 2024). For example, in Ghana, a state-led compulsory land acquisition in 1965 for the construction of the Barekese dam to supply water to Kumasi and its environs has led to a conflict lasting more than four decades. Worsening socioeconomic conditions, evolving national land governance frameworks, and growing advocacy for equitable resource use have prompted renewed attention to this conflict, with local communities contesting historical compensation arrangements (Forkuo et al., 2021; Cobbinah et al., 2020; Ayesu et al., 2024). In countries such as Tanzania, Mozambique, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Brazil, similar contentious land acquisitions have likewise triggered disputes over the public interest, adequacy of compensation, and recognition of customary land rights (ADHOC, 2014; Sauer and Pereira Leite, 2012; Wolford, 2010; Uisso and Tanrıvermiş, 2025; Duong et al., 2025). These shared challenges highlight the complexities involved in balancing national development objectives with the rights and interests of local populations.

In this context, conflict is defined as the experienced or perceived impairments arising from the actions of the parties involved, leading to reactions that can escalate the situation (Glasl, 1997; Marfo, 2006). Impairment refers to the interference with an individual or group's interests, needs, or values due to the actions of others (Marfo, 2006), often resulting in long-term grievances, loss of livelihoods, erosion of cultural heritage, and social unrest (Smyth and Vanclay, 2024; Ewusie et al., 2024). Understanding the mechanisms underlying these conflicts is, therefore, crucial for developing effective strategies to manage and resolve them.

The issues surrounding compulsory land acquisition and associated conflicts have been the focus of numerous academic studies. For example, Ubink (2008) explored the role of customary land tenure systems and their interaction with state policies in Ghana, highlighting the complexities and potential conflicts arising from overlapping legal frameworks. Amanor (2008) and Tran (2024) examined the impact of land acquisition on local communities, emphasizing displacement issues and erosion of traditional land rights. Similarly, Mabe (2019) and Smyth and Vanclay (2024) investigated the socio-economic impacts of land acquisition, noting the long-term consequences on affected populations, including poverty, loss of access to resources, and social disintegration. Despite this extensive body of research, limited studies have focused on how different stakeholders present their views and arguments in prolonged land acquisition disputes. Understanding these framing strategies is important for addressing the underlying issues and effectively managing conflicts, as frames influence perceptions, define the boundaries of disputes, and shape potential paths toward resolution (Entman, 1993).

Conflict framing provides a valuable theoretical lens for exploring this gap. Conflict frames are interpretive structures that individuals or groups use to make sense of a conflict situation, influencing their attitudes, behaviors, and interactions (Dewulf et al., 2009; Gray, 2003). According to Zimmermann et al. (2021), framing affects not only how parties define the issues at stake, but also how they assign blame, assess risks, and consider possible solutions. In the context of land acquisition conflicts, different stakeholders, such as government agencies, local communities, traditional authorities, civil society organizations, and private sector entities, can frame the conflict in various ways based on their interests, values, experiences, and power dynamics (Leach et al., 1999). For example, government agencies may frame acquisition as a necessary step for national development and public welfare, emphasizing legal rights and statutory mandates. In contrast, affected communities can frame the conflict around themes of injustice, rights violations, loss of livelihoods, and cultural dislocation. These different frames can lead to miscommunication, mistrust, and entrenched positions, complicating efforts to resolve the conflict.

Despite the importance of framing in conflict analysis, research that examines its role in long-term land acquisition disputes, particularly within the Ghanaian context, is scarce. This study, therefore, investigates the conflict frames employed by various actors involved in the Barekese conflict in Ghana. We answer the following research questions: (1) What are the major conflict frames associated with the compulsory acquisition of the Barekese lands in Ghana? (2) Which identifiable groups are associated with each conflict frame? (3) How do these conflict frames contribute to the dynamics and escalation of the conflict? (4) What implications do these conflict frames have for managing and resolving the conflict? By exploring these questions, our aim is to provide information on the underlying mechanisms that sustain such prolonged disputes. This understanding is crucial in formulating effective conflict management strategies and policies that consider the perspectives of all stakeholders.

Conflict framing theory posits that the way individuals and groups perceive, interpret, and communicate about a conflict significantly influences its development and resolution (Scartozzi, 2021). Frames are cognitive structures that help stakeholders make sense of complex situations by highlighting certain aspects while downplaying others (Goffman, 1974). According to Dewulf et al. (2009), conflict frames can be categorized into several types, including issue frames, identity frames, characterization frames, and process frames. Issue frames pertain to what the conflict is about, defining the key problems and concerns. Identity frames relate to how stakeholders see themselves and their core values, while characterization frames involve perceptions of others involved in the conflict. Process frames focus on how stakeholders believe the conflict should be managed or resolved.

In land acquisition conflicts, these frames can profoundly affect interactions between stakeholders. For example, if a community frames acquisition as a violation of ancestral rights (identity frame) and characterizes the government as exploitative (characterization frame), this can lead to resistance and hinder negotiation efforts (Mogalakwe, 2019). In contrast, if the government frames acquisition as essential for national development (issue frame) and perceives community concerns as obstacles to progress (characterization frame), this can result in inadequate engagement with affected parties.

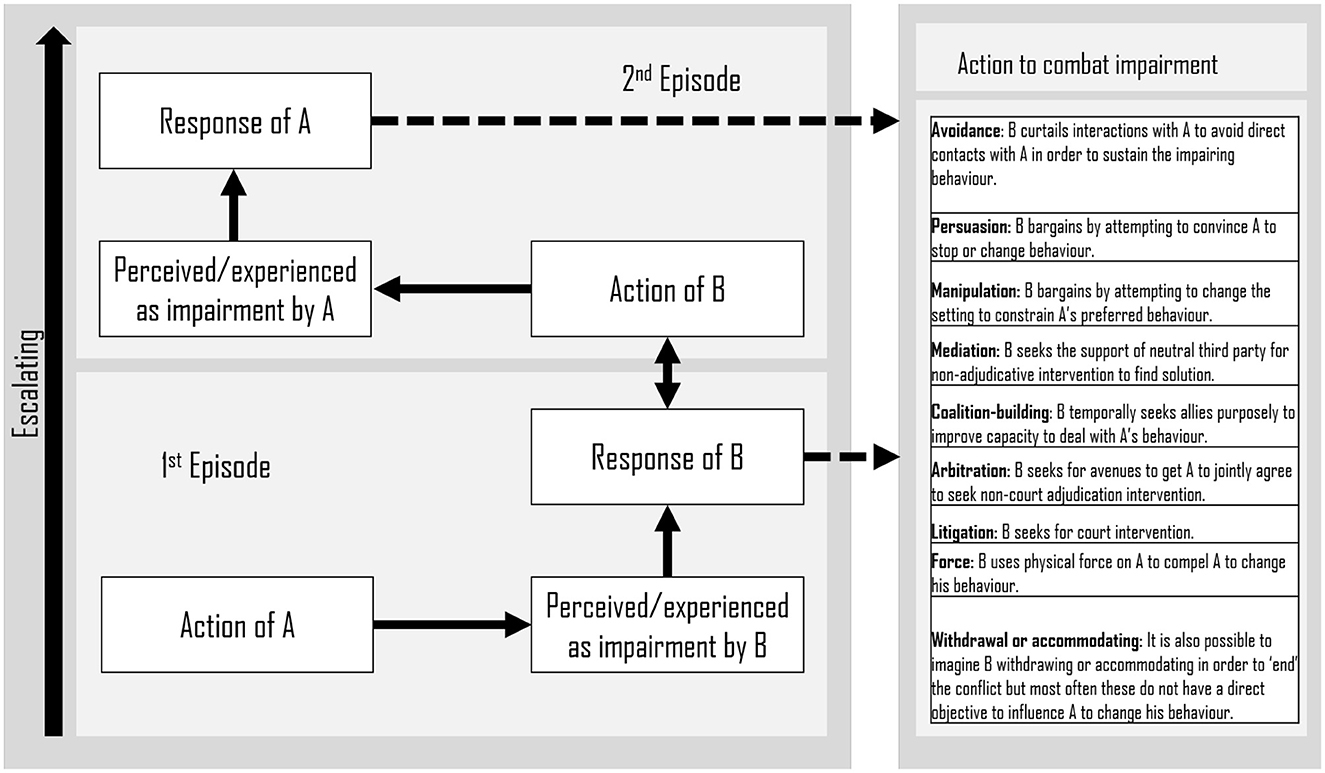

Glasl (1997) emphasizes that conflicts are sustained and escalated when parties have incompatible frames that lead to miscommunication and misunderstanding. Figure 1 shows how initial impairments or interferences with an individual's interests can lead to intentional actions that escalate the situation. The model begins with an initial impairment, where actor B perceives interference with their interests, needs, or values due to actions by actor A. In response, actor B can engage in intentional actions aimed at addressing the impairment, which can end or escalate the conflict.

Figure 1. Model of conflict episodes and potential intentional actions of an impaired actor resulting in escalation (Adapted from Glasl, 1997).

This escalation process highlights the importance of reframing or altering the way a situation is perceived and discussed to open up possibilities for conflict transformation. Marfo (2006) argue that reframing can help parties move beyond incompatible frames and find common ground. Similarly, Gray (2003) advocate for frame analysis as a tool to uncover underlying assumptions and facilitate a more effective dialogue between stakeholders.

Building on these theoretical foundations, we adopt a conceptual framework that integrates the various types of frame identified in the literature, considering:

• Issue frames: How each stakeholder defines the central issues of the conflict, such as legal rights, development needs, or social justice.

• Identity frames: The values, beliefs, and self-perceptions that stakeholders bring to the conflict, including cultural identity and historical connections to the land.

• Characterization frames: Stakeholder perceptions and attributions with respect to others involved in the conflict, which may involve assigning blame or questioning legitimacy.

• Process frames: Preferences and expectations about how the conflict should be addressed, including negotiation, legal action, or advocacy.

By applying this theoretical and conceptual framework to the Barekese conflict, we aim for an in-depth examination of the perspectives of different stakeholders, including government officials, local communities, and nongovernmental organizations. This approach is particularly important given the protracted nature of the dispute and the multitude of actors involved.

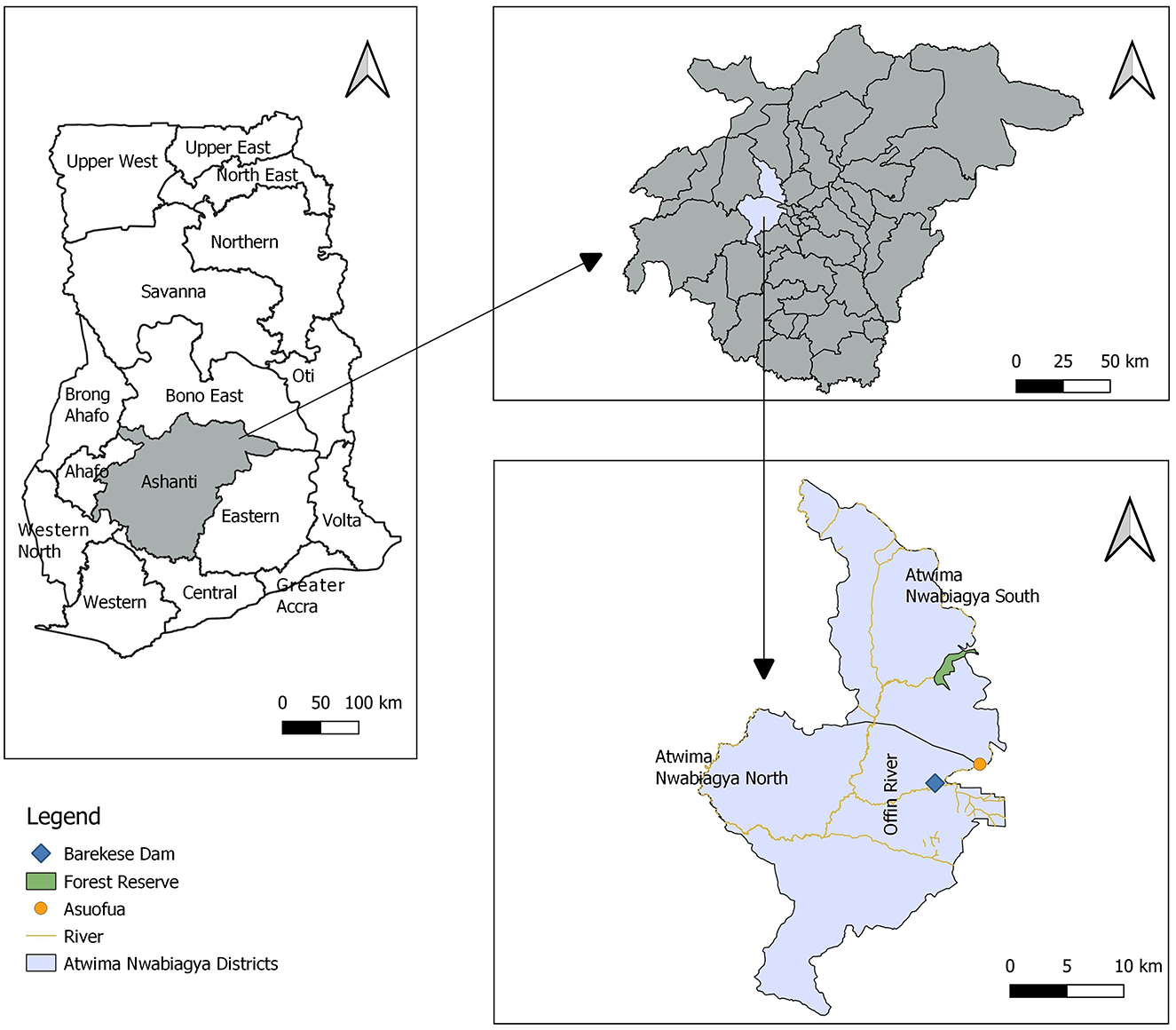

This study was carried out in Asuofua in the Atwima Nwabiagya South District of the Ashanti Region of Ghana (Figure 2). According to the 2010 population and housing census, Asuofua had a population of 5,617 (GSS, 2010). The community serves as the main resettlement site for communities displaced by the construction of the Barekese dam, making it an important location to understand the conflicts associated with state-led land acquisitions. It is also the only resettlement community in the whole Ashanti Region and has a history of past and recent conflicts.

Figure 2. Study area map showing the locations of Asuofua and the Barekese Dam within the Atwima Nwabiagya District, Ashanti Region, Ghana. The figure also shows the administrative boundaries of Ghana.

The displaced populations were specifically relocated to four suburbs in Asuofua: Anwoma, Amisare, Asuminya, and Tonto Kokoben. These suburbs were therefore the focus of our study.

Data for the study were obtained from various sources, including existing literature, 48 key informant interviews, 7 focus group discussions (FGD) with a total of 57 participants (farmer groups, youth groups, and traditional authorities), and field observations (Table 1). Semi-structured questionnaires were used for the interviews (Appendix A1). This method involves a set of predetermined questions that guide the interview, but also allows flexibility to probe deeper into responses, adapting the conversation flow based on the insights of the interviewee (Belina, 2023). The approach is particularly effective in exploring complex issues such as the Barekese conflict, as it accommodates the exploration of individual perspectives while remaining aligned with the core research objectives (Belina, 2023).

Interviews and focus group discussions were conducted from 01/03/2022 to 25/05/2022. Participants were selected using the snowball sampling technique, which is often used in qualitative research to identify individuals with specific knowledge or experience relevant to the research topic (Parker et al., 2019; Naderifar et al., 2017). Key informants were identified based on their roles, experience or involvement in the conflict, including community leaders and local stakeholders familiar with the study context. Subsequently, these individuals recommended other potential participants with relevant knowledge and experience. This approach ensured a comprehensive representation of the various stakeholder groups involved in the conflict, including farmers, youth leaders, traditional authorities, and representatives of relevant agencies.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring that they were fully aware of the purpose of the study, their role, and the voluntary nature of their participation (Bhutta, 2004; Faden et al., 1986). The participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses, all data being stored securely and only used for research purposes (Wiles et al., 2008; Gibson et al., 2013; Hoft, 2021). Sensitive topics were approached with cultural sensitivity and respect, seeking permission from local leaders before initiating discussions, using culturally appropriate language, and ensuring that all interactions were guided by understanding of local customs and values (Foronda, 2008). The research adhered to these ethical guidelines to protect the rights and well-being of all participants involved.

The qualitative data obtained from the facilitated stakeholder dialogue and interviews were analyzed using the NVivo 14 thematic analysis software (Dhakal, 2022). Qualitative data analysis software enables researchers to manage, organize, and analyse large volumes of text data while maintaining a clear audit trail of the coding process and the development of emerging themes systematically and efficiently (Gibbs, 2007). An inductive approach was chosen for the analysis to identify key themes, patterns, and categories directly from the data (Kiger and Varpio, 2020). This approach starts with observations of the raw data and then moves to broader generalizations, allowing the discovery of new insights and understandings that are grounded in the experiences, perspectives, and aspirations of the participants (Edwards-Jones, 2014; Liu, 2016). In contrast, a deductive approach, which is typically more suitable for hypothesis testing or theory-driven research, begins with preexisting theoretical frameworks or assumptions to guide the analysis process (Elo and Kyngas, 2008; Dhakal, 2022). In this instance, the use of a deductive approach could have limited the scope of the analysis and potentially overlooked important nuances and emerging themes that may not have been captured by preexisting frameworks or expectations.

Thematic analysis begins with familiarization with the data to understand its nuances (Kiger and Varpio, 2020). The initial codes were then generated, marking key features in the data relevant to the research question. The subsequent stage involved searching for themes by identifying patterns within these codes. The themes were then reviewed and refined, ensuring that they accurately represented the data. This was followed by the definition and naming of each theme, providing a clear and concise description of their content and meaning. Finally, the process culminated in the production of the final analysis, weaving together the thematic insights to form a coherent and comprehensive understanding of the data in relation to the research objectives. Throughout this process, data was constantly re-examined to ensure that the identified themes accurately reflected the perspectives and experiences of stakeholders.

The study identified four primary conflict frames arising from compulsory land acquisition by the state: delayed crop compensation, failed government promises, property destruction, and inaccuracies in documentation (Table 2). These frames represent the different ways in which affected groups perceive and respond to the issues surrounding land acquisition. The following sections provide an in-depth examination of these conflict frames, supported by illustrative quotes from key informants that shed light on the experiences and perspectives of the affected communities.

Delayed payment of crop compensation emerged as the most prominent conflict frames among the participants. They reported that while the first tranche of compensation payments was disbursed, subsequent delays in releasing the second tranche have intensified existing economic hardships. This delay has adversely affected the ability of people to access basic necessities due to financial constraints. Civil society representatives highlighted the situation as follows:

“The delay in compensation has brought hardship on the affected communities, resulting in the inability of some farmers to afford medical treatment. Families have been strained, and the stress of waiting for compensation has led to additional health complications among the elderly. This is not just a financial issue, but one that affects basic wellbeing.”

– Civil Society Representative 1, FGD, 11/03/2022

“Some of the affected farmers have passed away without receiving their compensations. These individuals relied on their land as their primary asset, expecting it to secure their futures. Instead, their families are now facing financial difficulties.”

– Civil Society Representative 2, FGD, 11/03/2022

These accounts indicate that delayed compensation is perceived as more than a financial issue; it is seen as a breach of trust between the government and its citizens. Participants highlighted concerns about the implementation of the compensation policy, suggesting that procedural delays have negatively affected their wellbeing. The absence of prompt and transparent compensation processes appears to contravene legal mandates and may undermine the capacity of these communities to recover economically.

Although Ghana's State Lands Act, 1962 (Act 125) provides prompt, fair, and adequate compensation, participants reported that this has not been the case in Asuofua. Key informants expressed dissatisfaction with the government and the Ghana Water Company (GWC) regarding the long delays. Some community members indicated that if the second tranche of compensation is not disbursed promptly, they might resort to actions such as encroaching on the peripheries of the dam.

Resettled farmers also expressed concerns that, by the time compensation is paid, the value may have depreciated, making it challenging to invest in productive ventures. One farmer alleged that the GWC had invested the funds released by the government in treasury bills for profit.

“The government has transferred the money to GWC, but they have invested it in treasury bills instead of disbursing it to us, the beneficiaries. This is causing us continued hardship.”

– Resettled Farmer 1, Interview, 14/03/2022

This statement reflects perceptions of mismanagement of compensation funds, raising concerns about transparency and ethical practices. The prioritization of institutional interests over community welfare may have negative implications for trust and cooperation between the state and local populations.

Further concerns were raised about the transparency and adequacy of the compensation process, with several participants indicating that the payments in the first tranche did not reflect the actual value of the destroyed crops. They reported that the bureaucratic processes involved have led some individuals to engage in unofficial methods to claim their dues, potentially eroding trust in the authorities.

“The first tranche of the compensation payment was problematic. The amount was less than expected and the process lacked transparency. Some of us felt compelled to offer incentives to officials to receive what was due to us. This situation is unsatisfactory, as we have already lost our lands and crops, and now face challenges to receive fair compensation.”

– Community Youth Leader, Interview, 16/03/2022

These sentiments highlight the unintended consequences of flawed compensation processes. The lack of transparency and perceived inadequacy of compensation may reflect broader governance challenges. Ensuring transparency and accountability is essential for the success of land acquisition projects, particularly in contexts where livelihoods are directly affected.

Another widely reported conflict frame refers to the government's failure to fulfill promises made during the 1975 resettlement process. These promises included the provision of alternative farmland, free access to water, and prompt compensation. Unfulfilled commitments have caused feelings of disappointment and frustration among affected populations. A resettled farmer expressed this perspective:

“I did not pay for water at our previous settlement, but now I have to purchase water, which is financially burdensome. The government promised us free water, but currently I pay for each bucket. This has created additional hardship.”

– Resettled Farmer 2, FGD, 19/03/2022

The account of Resettled Farmer 2 underscores the impact of unfulfilled promises on the daily lives of resettled individuals. The failure to honor commitments has affected not only the present generation, but may also influence future government-community relations.

The younger generation expressed particular concern, feeling affected by the decisions made by their parents, and the subsequent lack of government follow-up:

“Government and GWC have not treated us fairly. Our parents made sacrifices for the dam project, expecting that their actions would benefit future generations. However, we are now facing difficulties and the anticipated improvements have not materialized.”

– Community Youth Leader 1, Interview, 22/03/2022

This frame highlights the generational implications of unmet expectations, which can erode trust and cohesion within the community. Addressing the needs and expectations of younger populations is important in fostering positive government-community interactions.

An elder in the community suggested that unmet promises could contribute to youth-led activities such as unauthorized logging near the dam, indicating a potential link between unaddressed grievances and adverse environmental practices.

Some participants raised the frame of property destruction, highlighting conflicts arising from illegal encroachments on government-acquired land. The government response, which involves the demolition of buildings and the destruction of farmlands, has caused distress among those affected.

“The demolition of my building was unexpected and has caused significant hardship for my family. We invested our savings in building the house and its loss has left us without a residence.”

– Community Member 1, Interview, 23/03/2022

“It is disheartening to cultivate land, only to find that the efforts are negated without adequate explanation. This situation has been challenging, and we feel that the government has not treated us fairly.”

– Resettled Farmer 3, Interview, 23/03/2022

These reflect the ongoing consequences of unresolved compensation issues, which have led to unauthorized activities and heightened tensions within the community. The sale and lease of disputed land by some community members have further complicated the situation.

“The unauthorized sale and lease of government-acquired land are concerning. It appears that some individuals, possibly affected farmers or their relatives, may be engaging in these activities due to unresolved compensation matters.”

– Traditional Leader 1, Interview, 23/03/2022

These developments demonstrate the complex interplay between unaddressed grievances and community dynamics. Addressing compensation and land rights issues may be essential for reducing tensions and preventing further conflicts.

The inaccuracy in the document frame focuses on administrative challenges related to compensation payments. Approximately 10 key informants attributed the problem to insufficient scrutiny and auditing of the documents available by valuation officers. A community youth leader described the situation as follows:

“Every four years, politicians promise that documentation issues will be reviewed and our concerns addressed when they assume office. However, after elections, they do not follow up on these promises.”

– Community Youth Leader 3, Interview, 23/03/2022

This perspective suggests that documentation inaccuracies are perceived as being influenced by political factors, potentially undermining trust in the authorities. Traditional authorities also expressed a lack of confidence in the Land Valuation Division (LVD) and the GWC regarding the payment of the owed compensation.

GWC and LVD officials framed the situation as one that involved inadequate documentation and limited funds for payments. They indicated that efforts are underway to obtain the necessary documentation and funding from the government. It was noted that while the government has compensated the “paramount chiefs” for the acquired lands, not all farmers have received compensation for their crops.

The participants expressed a preference to resolve the issues through amicable negotiations with the government rather than confrontational means. This viewpoint is illustrated by a farmer's remark:

“The best way to receive our payments is to negotiate and find a compromise regarding the valuation differences.”

– Resettled Farmer 4, FGD, 10/03/2022

A common request from focus group discussions was that the government settle the outstanding crop compensations. Some key informants also emphasized the importance of addressing the community's need for accessible water supply. They further expressed their willingness to collaborate with the government to prevent unauthorized activities near the dam if their concerns are addressed.

A community youth leader suggested that GWC, in collaboration with LVD, audit existing documents to identify legitimate beneficiaries and proceed with payments to improve community relations. Another respondent proposed that GWC consider employing local residents to reduce unemployment and strengthen community ties.

“GWC should employ some community members as part of their workforce. This would help reduce unemployment among youth in Asuofua and would serve as both compensation and a gesture of solidarity.”

– Community Youth Leader 3, Interview, 10/03/2022

Migrant farmers and settlers who experienced property destruction are requesting compensation for their losses, highlighting the need for comprehensive solutions that address the concerns of all affected groups.

This study aimed to investigate the conflict frames used by various stakeholders in the prolonged Barekese land acquisition conflict in Ghana. It provides insights into how different frames have shaped the progression and persistence of the conflict. The findings reveal that incompatible frames between stakeholders have led to miscommunication, mistrust, and escalation, hindering effective dialogue and resolution efforts.

The four main conflict frames identified—delayed crop compensation, failed government promises, property destruction, and inaccuracies in documentation—reflect the diverse perceptions and grievances of affected stakeholders. These frames align with the types of frames outlined in conflict framing theory: issue frames, identity frames, characterization frames, and process frames (Dewulf et al., 2009).

Delayed payment of crop compensation emerged as one of the most frequently reported conflict frames. It is primarily an issue frame, focusing on the unmet financial obligations of the government to compensate farmers for their lost crops. The prolonged delay has exacerbated hardships, causing severe consequences such as an inability to meet basic needs. This frame also aligns with the identity frame, where farmers perceive themselves as victims of injustice and neglect. Similar findings were reported by Gemeda et al. (2023), who noted that delayed compensation in land acquisition projects in Ethiopia caused significant socioeconomic hardships for affected farmers. The government's inaction is viewed through characterization frame as exploitative and untrustworthy, with allegations that GWC invested compensation funds in Treasury bills for institutional profit. The preferred process frame among affected farmers is negotiation, although there is an undercurrent of potential escalation if their grievances remain unaddressed. This parallels observations by Lankono et al. (2023), who highlighted that lack of trust in government institutions can lead to increased tensions and potential conflict in land-related disputes.

Another frequently mentioned frame concerns the government's failure to fulfill promises made during the 1975 resettlement process, including the provision of alternative farmland and free access to water. This frame blends issue and identity frames, as affected communities feel a sense of betrayal, shaping negative perceptions for future generations. Young people in particular report that their prospects have been undermined by the unfulfilled commitments of the past. The government is characterized as deceptive and unreliable, further entrenching mistrust. Similar sentiments were expressed by Adu-Gyamfi (2012) and Lankono et al. (2023), who noted that broken promises by authorities exacerbate community grievances and undermine social cohesion. The process frame here underscores a desire for accountability and the fulfillment of commitments, emphasizing the need for the government to restore trust through concrete actions.

The frame of property destruction, although less frequently mentioned, represents acute grievances arising from the government's demolition of buildings and destruction of farmlands due to illegal encroachments. The issue frame focuses on the loss of property and livelihood without adequate justification or compensation. Victims employ an identity frame of powerlessness and unjust targeting, while the government is characterized as harsh and unjust. This highlights the cascading effects of unresolved compensation issues, leading to illegal activities and further destabilization of the community. Sabogu et al. (2020) noted that such actions can lead to increased tensions and increase the probability of violent confrontations. The process frame indicates a call for fair treatment and compensation for losses, suggesting that addressing these immediate grievances is essential for de-escalation.

The inaccuracy in the document frame is unique as it originates from governmental perspectives, particularly officials from GWC and LVD. This frame is primarily an issue frame centered on administrative challenges that hinder compensation payments. The characterization frame from the community's perspective portrays officials as incompetent or intentionally obstructive, with accusations of “political gimmickry” to manipulate and mislead the community. This underscores systemic bureaucratic inefficiencies and highlights the need for improved administrative processes. According to Yeboah and Shaw (2013), bureaucratic hurdles and documentation inaccuracies are common issues that hinder effective land administration in Ghana. The process frame involves calls for thorough auditing of documents and immediate action to rectify delays.

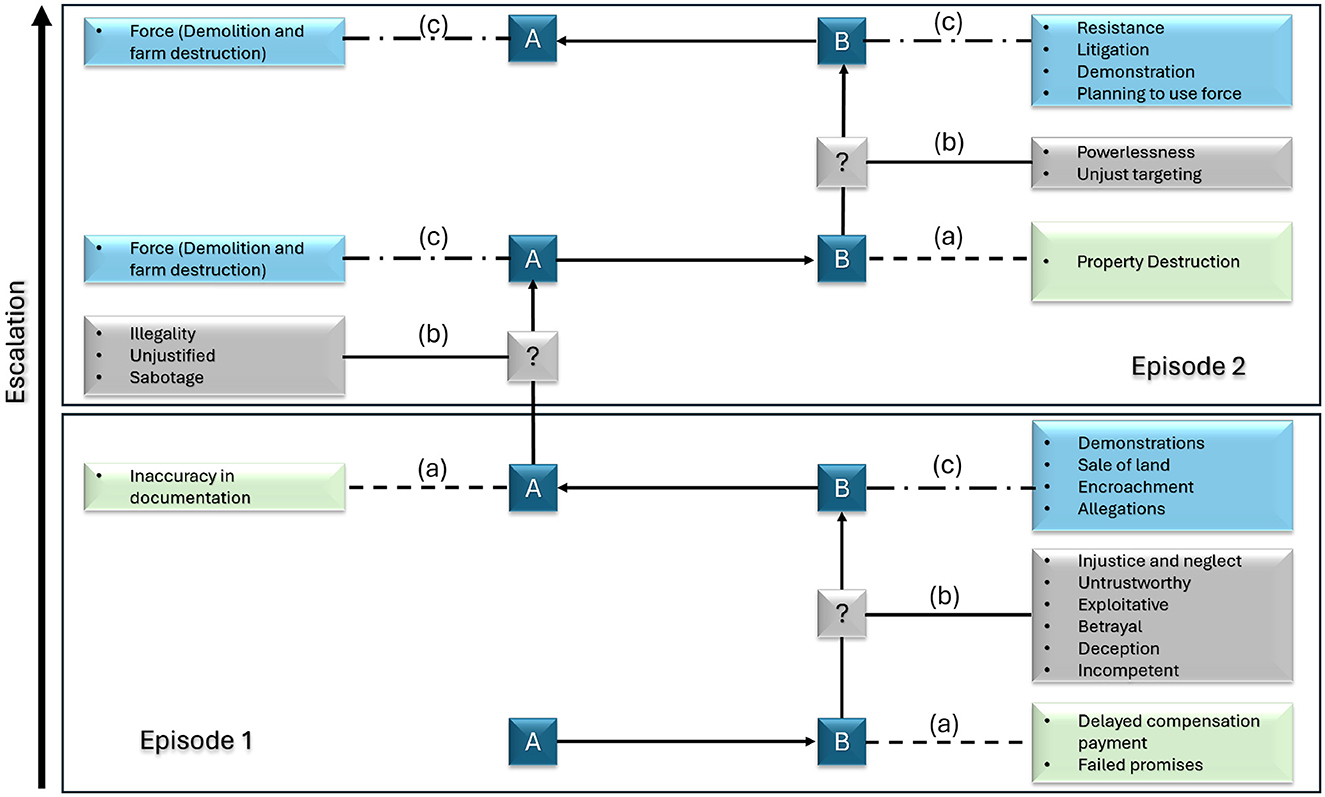

The findings demonstrate how initial impairments, such as loss of land and delayed compensation, act as catalysts for intentional actions by affected stakeholders, potentially escalating the conflict (Figure 3). Glasl (1999) outlines nine stages of conflict escalation, ranging from hardening positions to total confrontation. In the Barekese conflict, incompatible frames between stakeholders contribute significantly to miscommunication and misunderstanding, intensifying tensions, and propelling the conflict through these stages. For example, affected communities frame the government as untrustworthy and neglectful, emphasizing themes of injustice and betrayal. This identity frame fosters resistance and hostility toward government authorities. However, the government's focus on administrative challenges and legal processes, without adequately addressing underlying grievances, exacerbates feelings of neglect among the communities. This misalignment of the frames leads to a lack of empathy and mutual understanding, which Glasl identifies as critical in the early stages of conflict escalation (Glasl, 1999).

Figure 3. Conflict escalation dynamics in Barekese: (a) Current frames–delayed crop compensation, failed government promises, property destruction, and inaccuracies in documentation. (b) Perceptions–Actor B (Affected Communities) perceives injustice, betrayal, or neglect in response to actions by Actor A (Government). (c) Intentional actions–these perceptions drive responses such as illegal encroachments, resistance, demonstrations, or confrontations, escalating the conflict over time. The diagram shows how frames trigger responses, leading to a reinforcing cycle of tension and conflict.

Conflict escalation in Barekese is manifested in actions such as illegal encroachments on the peripheries of the dam, threats of drastic measures by community members, and destructive activities led by youth (Figure 3). Such behaviors reflect the progression from latent conflict to overt confrontation, corresponding to the middle stages of Glasl's model, where parties begin to take aggressive actions to assert their positions (Glasl, 1999). The failure to address incompatible frames and underlying issues perpetuates the cycle of conflict, making resolution increasingly challenging. According to Marfo (2006), unresolved grievances and entrenched frames can lead to long-lasting conflicts, especially when stakeholders are deeply polarized.

The Barekese conflict exhibits characteristics of power asymmetry, where the government holds significant authority over land acquisition processes, while affected communities have limited avenues for redress. This imbalance can accelerate conflict escalation, as marginalized groups may resort to drastic measures to make their voices heard (Brockner and Rubin, 2012). The perceptions of injustice and powerlessness of communities contribute to the intensification of the conflict, aligning with Glasl's stages, where parties begin to see each other as adversaries and may dehumanize the opposition (Glasl, 1999). In Ghana, customary land tenure systems are deeply rooted in social and cultural practices, and their disruption can lead to significant social unrest (Kasanga and Kotey, 2001).

The role of discourse and framing in legitimizing or challenging land acquisitions is evident in the Barekese conflict. According to Van Leeuwen (2010) and Sikor and Lund (2009), frames shape the perceptions and actions of the stakeholders, influencing the trajectory of conflicts. The government's framing of the acquisition as a legal and administrative matter contrasts sharply with the communities' framing of it as a profound social injustice. Without efforts to bridge these frames through dialogue and mutual understanding, the conflict is likely to persist or escalate further (Gray, 2003). Dewulf et al. (2009) emphasize that acknowledging and addressing frame differences is essential for conflict resolution, as it allows stakeholders to reframe the issues in ways that are more conducive to cooperation. Figure 3 summarizes the link between the four key conflict frames and the actions taken by the two main actors, resulting in an escalation of the conflict over time.

Encouraging stakeholders to adopt more compatible frames requires identifying and emphasizing shared interests and common goals (Lewitter et al., 2019). In this study, stakeholders can find common ground in the desire for sustainable community development, improved livelihoods, and environmental conservation. Highlighting these shared objectives can foster a sense of collective responsibility and mutual benefit (Ibrahim et al., 2022; Marfo, 2006). According to Lederach (2015), building peace in protracted conflicts involves engaging in the relational aspects of the conflict, including the perceptions, emotions, and identities of the stakeholders. Processes such as dialogue workshops, participatory conflict analysis, and joint problem solving sessions can allow stakeholders to express their concerns, listen to others, and develop a shared understanding of conflict dynamics (Fisher et al., 2000). In this case, the participation of community leaders, government representatives, and neutral facilitators can help bridge communication gaps and rebuild trust.

Mediation by neutral parties is instrumental in reframing efforts, particularly when mistrust and power asymmetries are present. Neutral mediators can help stakeholders explore alternative perspectives, acknowledge legitimate needs of each other, and reframing contentious issues in more manageable terms (Moore, 2014). Crook (2008) and Asaaga (2021) emphasize the effectiveness of culturally appropriate alternative dispute resolution mechanisms in the resolution of land conflicts in Ghana. They highlight that mediation processes that respect local customs and involve traditional authorities can enhance legitimacy and acceptance among stakeholders. In this study, such mediation should involve addressing underlying grievances, such as acknowledging past failures, such as delayed compensation, unfulfilled promises, and procedural injustices. According to Burton (2024), unmet basic human needs, including security, identity, and recognition, are the fundamental drivers of conflict. Therefore, addressing these needs through responsive policies and genuine engagement can reduce tensions and foster reconciliation.

According to Rossner and Taylor (2024), reframing can benefit from incorporating the principles of restorative justice, which focus on repairing damage and restoring relationships rather than assigning blame. Restorative dialogues allow stakeholders to express feelings of hurt, share impacts and collaboratively develop solutions. This approach is in line with the customary practices of communal conflict resolution in Ghana, where emphasis is placed on harmony and social cohesion (Tsikata and Seini, 2004). For the reframing to be effective in the Barekese conflict, sustained commitment from all stakeholders is necessary. The government must demonstrate willingness to address past shortcomings, perhaps by reviewing compensation agreements and ensuring timely and fair disbursements. Communities, on their part, can engage constructively by articulating their needs and exploring collaborative solutions. Joint initiatives, such as community development projects co-managed by local residents and government agencies, can build trust and demonstrate shared investment in positive outcomes. Integrating reframing efforts with broader policy reforms can enhance their impact. This includes re-visiting land acquisition laws to ensure more participatory processes, strengthening legal protections for affected communities, and improving institutional accountability mechanisms (Boamah, 2014). Such systemic changes address structural factors that contribute to conflict and support sustainable peacebuilding.

Addressing the identified conflict frames requires transparent compensation processes, robust legal adherence, participatory engagement, institutional reforms, and sustained capacity building. Policymakers must ensure prompt, fair and adequate compensation as required by the Ghana State Lands Act, 1962 (Act 125), with strict enforcement mechanisms to prevent delays observed in this case (Kasanga and Kotey, 2001). Honoring resettlement promises and monitoring their fulfillment is also essential to maintain trust and credibility (Larbi, 1995).

Practitioners should use frame analysis to understand the diverse perspectives of stakeholders, supporting reframing efforts to reduce miscommunication and promote mutual understanding (Gray, 2003). Capacity building, including legal rights training and negotiation skills development, can empower communities to articulate their needs effectively. Transparency in valuation, independent oversight, and accessible grievance mechanisms promote trust and reduce perceptions of exploitation (Ubink, 2008; Cotula et al., 2009; UN, 2007). Strengthening local governance structures and leadership capacities improves advocacy and ensures that community interests are represented effectively (Dewulf et al., 2009).

Collaborative approaches that involve government agencies, communities, civil society, and the private sector can foster more sustainable and equitable project results (Yaro, 2010; Yeboah and Shaw, 2013; World Bank, 2017). Integrating sustainable development principles, such as ensuring social safeguards, conducting thorough environmental and social impact assessments, and promoting long-term community development, into land acquisition processes allows for a balanced consideration of social, economic and environmental factors (Conroy and Wilson, 2024; Sahoo and Goswami, 2024; Cotula et al., 2009). Institutional reforms aimed at improving land administration capabilities, improving inter-agency coordination, and reviewing legal frameworks can help prevent conflicts and align policies with international standards (Zhu and Tong, 2024; Luo, 2024). In addition, continuous monitoring, evaluation, and strategic use of technology can improve efficiency, accountability, and responsiveness, ensuring that policies adapt to evolving contexts and emerging challenges.

This study investigated the conflict frames used by various stakeholders involved in the prolonged Barekese land acquisition conflict in Ghana. By applying conflict framing theory and integrating Glasl's conflict escalation model, the research provided a nuanced understanding of how different frames have shaped the conflict's progression and persistence. The findings revealed that incompatible frames between stakeholders centered on delayed crop compensation, failed government promises, property destruction, and inaccuracies in documentation have led to miscommunication, mistrust, and escalation, thereby hindering effective dialogue and resolution efforts. The most significant conflict frames were the delay in crop compensation and failed government promises, reflecting deep-seated grievances and a profound sense of betrayal among affected communities. These frames not only refer to unmet financial obligations, but also encompass issues of identity, trust, and perceived injustice. The government's framing, focusing on administrative challenges and legal mandates, failed to address the underlying emotional and sociocultural dimensions of the conflict. The findings underscore the importance of recognizing and addressing diverse stakeholder frames in managing and resolving land acquisition conflicts. Policymakers must prioritize transparent and timely compensation processes, fulfill promises made during resettlement, and engage meaningfully with affected communities to rebuild trust. Practitioners should employ frame analysis to identify incompatible frames and facilitate reframing efforts that promote mutual understanding and collaboration. Empowering affected communities through inclusive dialogue and participation in decision-making processes is essential for sustainable transformation of conflicts. In general, the study highlights that effective conflict management requires a holistic approach that considers not only the material and legal aspects but also the cognitive and communicative dimensions that shape the perceptions and interactions of stakeholders. Future research should explore similar conflicts in different contexts, employ longitudinal designs to examine the evolution of frames over time, and investigate additional factors that influence conflict dynamics.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Natural Resources Management, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). All research activities were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and local legislation. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study.

EO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Resources, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

We are grateful to Cherith Moses, Carolina Peña Alonso, and Irene Delgado-Fernández for their valuable reviews and constructive feedback, which significantly improved the quality of this work.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsrma.2025.1543829/full#supplementary-material

ADHOC. (2014). A turning point? Land, housing and natural resource rights in Cambodia. Technical report, Cambodian Human Rights and Development Association (ADHOC), Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Adu-Gyamfi, A. (2012). An overview of compulsory land acquisition in ghana: examining its applicability and effects. Environ. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 1, 187–203. doi: 10.5296/emsd.v1i2.2519

Akrofi, E., and Whittal, J. (2013). Compulsory acquisition and urban land delivery in customary areas in Ghana. South African J. Geomat. 2, 280–295. doi: 10.15396/afres2012_115

Amanor, K. (2008). “The changing face of customary land tenure,” in Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana: State, Chief and the Citizen, eds. J. Ubink and K. Amanor (Netherlands: Leiden University Press), 55–80.

Asaaga, F. A. (2021). Building on “traditional” land dispute resolution mechanisms in rural Ghana: adaptive or anachronistic? Land 10:143. doi: 10.3390/land10020143

Ayesu, S., Agbyenyaga, O., Barnes, V. R., and Asante, R. K. (2024). Community perception to pay for conservation of barekese and owabi watersheds in Ghana. Heliyon 10:e25885. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25885

Belina, A. (2023). Semi-structured interviewing as a tool for understanding informal civil society. Voluntary Sector Rev. 14, 331–347. doi: 10.1332/204080522X16454629995872

Boamah, F. (2014). How and why chiefs formalise land use in recent times: the politics of land dispossession through biofuels investments in Ghana. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 41, 406–423. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2014.901947

Brockner, J., and Rubin, J. Z. (2012). Entrapment in Escalating Conflicts: A Social Psychological Analysis. New York: Springer Science &Business Media.

Burton, J. W. (2024). “The problem stated: forms of conflict (1962),” in John W. Burton: A Pioneer in Conflict Analysis and Resolution, volume 33 of Pioneers in Arts, Humanities, Science, Engineering, Practice, eds. D. J. Dunn, H. G. Brauch, and P. Burton (Springer, Cham), 59–71. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-51258-2

Cobbinah, P. B., Gaisie, E., Oppong-Yeboah, N. Y., and Anim, D. O. (2020). Kumasi: Towards a sustainable and resilient cityscape. Cities 97:102567. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.102567

Conroy, M. M., and Wilson, J. P. (2024). Are we there yet? Revisiting “planning for sustainable development” 20 years later. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 90, 274–288. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2023.2211574

Cotula, L., Vermeulen, S., Leonard, R., and Keeley, J. (2009). Land Grab or Development Opportunity? Agricultural Investment and International Land Deals in Africa. London/Rome: IIED/FAO/IFAD.

Crook, R. C. (2008). “Customary justice institutions and local alternative dispute resolution: what kind of protection can they offer to customary landholders?” in Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana: State, Chief and the Citizen, eds. J. M. Ubink, and K. S. Amanor (Leiden: Leiden University Press), 131–154.

Dewulf, A., Gray, B., Putnam, L., Lewicki, R., Aarts, N., Bouwen, R., et al. (2009). Disentangling approaches to framing in conflict and negotiation research: a meta-paradigmatic perspective. Hum. Relat. 62, 155–193. doi: 10.1177/0018726708100356

Duong, M. T., Samsura, D. A. A., and van der Krabben, E. (2025). Land increment value distribution through land development strategies for tourism in Vietnam. J. Property Res. 2025, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/09599916.2024.2444889

Edwards-Jones, A. (2014). Qualitative data analysis with nvivo. J. Educ. Teach. 40, 193–195. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2013.866724

Elo, S., and Kyngas, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Entman, R. (1993). Framing: towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Ewusie, I., Tannor, O., Ahiadu, A., and Ntim, O. (2024). Exploring the psychological and emotional burden of compulsory acquisition: a case study of new akrade-mpakadan, Ghana. Property Manag. 42, 1–19. doi: 10.1108/PM-10-2023-0105

Faden, R. R., Beauchamp, T. L., and King, N. M. P. (1986). A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fisher, S., Abdi, D. I., Ludin, J., Smith, R., Williams, S., and Williams, S. (2000). Working with Conflict: Skills and Strategies for Action. London: Zed Books.

Forkuo, E. K., Biney, E., Harris, E., and Quaye-Ballard, J. A. (2021). The impact of land use and land cover changes on socioeconomic factors and livelihood in the atwima nwabiagya district of the Ashanti region, Ghana. Environ. Chall. 5:100226. doi: 10.1016/j.envc.2021.100226

Foronda, C. L. (2008). A concept analysis of cultural sensitivity. J. Transc. Nurs. 19, 207–212. doi: 10.1177/1043659608317093

Gemeda, F., Guta, D., Wakjira, F., and Gebresenbet, G. (2023). Land acquisition, compensation, and expropriation practices in the Sabata town, Ethiopia. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 7:em0212. doi: 10.29333/ejosdr/12826

Gibbs, G. (2007). Analyzing Qualitative Data. London, England: SAGE Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781849208574

Gibson, S., Benson, O., and Brand, S. L. (2013). Talking about suicide: confidentiality and anonymity in qualitative research. Nurs. Ethics 20, 18–29. doi: 10.1177/0969733012452684

Glasl, F. (1997). Konfliktmanagement: Ein Handbuch für Führungskräfte, Beraterinnen und Berater. Bern: Verlag Paul Haupt 5 edition.

Glasl, F. (1999). Confronting Conflict: A First-Aid Kit for Handling Conflict. Stroud: Hawthorn Press.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gray, B. (2003). “Framing of environmental disputes, in Making sense of intractable environmental conflicts: Concepts and cases, eds. R. J. Lewicki, B. Gray, and M. Elliott (Washington, DC: Island Press), 11–34.

Hoft, J. (2021). “Anonymity and confidentiality, in The Encyclopedia of Research Methods in Criminology and Criminal Justice, 223–227. doi: 10.1002/9781119111931.ch41

Ibrahim, A.-S., Abubakari, M., Akanbang, B. A., and Kepe, T. (2022). Resolving land conflicts through alternative dispute resolution: exploring the motivations and challenges in Ghana. Land Use Policy 120:106272. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106272

Kasanga, K., and Kotey, N. A. (2001). Land Management in Ghana: Building on Tradition and Modernity. Land Tenure and Resource Access in West Africa. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Kiger, M., and Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: Amee guide no. 131. Med. Teach. 42, 846–854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

Lankono, C. B., Forkuor, D., and Asaaga, F. A. (2023). Examining the impact of customary land secretariats on decentralised land governance in Ghana: evidence from stakeholders in northern Ghana. Land Use Policy 130:106665. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106665

Larbi, W. O. (1995). The Urban Land Development Process and Urban Land Policies in Ghana. London: Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

Leach, M., Mearns, R., and Scoones, I. (1999). Environmental entitlements: Dynamics and institutions in community-based natural resource management. World Dev. 27, 225–247. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00141-7

Lederach, J. P. (2015). The Little Book of Conflict Transformation: Clear Articulation of the Guiding Principles by a Pioneer in the Field. Justice and Peacebuilding. New York, NY: Good Books.

Lewitter, F., Bourne, P. E., and Attwood, T. K. (2019). Ten simple rules for avoiding and resolving conflicts with your colleagues. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15:e1006708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006708

Liu, L. (2016). Using generic inductive approach in qualitative educational research: a case study analysis. J. Educ. Learn. 5, 129–129. doi: 10.5539/jel.v5n2p129

Luo, K. W. (2024). Redistributing power: land reform, rural cooptation, and grassroots regime institutions in authoritarian Taiwan. Compar. Polit. Stud. 58:104140241237457. doi: 10.1177/00104140241237457

Mabe, F. (2019). The nexus between land acquisition and household livelihoods in the northern region of Ghana. Land Use Policy 85, 357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.03.043

Marfo, E. (2006). Powerful relations: The role of actor-empowerment in the management of natural resource conflict A case of forest conflicts in Ghana. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the Netherlands.

Mogalakwe, M. (2019). The State and Organised Labour in Botswana: Liberal Democracy in Emergent Capitalism. London: Routledge 2 edition. doi: 10.4324/9780429432958

Moore, C. W. (2014). The Mediation Process: Practical Strategies for Resolving Conflict. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Naderifar, M., Goli, H., and Ghaljaie, F. (2017). Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides Dev. Med. Educ. 14:67670. doi: 10.5812/sdme.67670

Okoth-Ogendo, H. (2000). “Legislative approaches to customary tenure and tenure reform in east africa, in Evolving land rights, policy and tenure in Africa, eds. C. Toulmin, and J. Quan (London, UK: International Institute for Environment and Development), 123–134.

Parker, C., Scott, S., and Geddes, A. (2019). Snowball Sampling. London: SAGE research methods foundations.

Rossner, M., and Taylor, H. (2024). The transformative potential of restorative justice: what the mainstream can learn from the margins. Ann. Rev. Criminol. 7, 357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev-criminol-030421-040921

Sabogu, A., Nassé, T. B., and Osumanu, I. K. (2020). Land conflicts and food security in africa: an evidence from dorimon in Ghana. Int. J. Manag. Entrepr. Res. 2, 74–96. doi: 10.51594/ijmer.v2i2.126

Sahoo, S., and Goswami, S. (2024). Theoretical framework for assessing the economic and environmental impact of water pollution: a detailed study on sustainable development of India. J. Future Sustain. 4, 23–34. doi: 10.5267/j.jfs.2024.1.003

Sauer, S., and Pereira Leite, S. (2012). Agrarian structure, foreign investment in land, and land prices in brazil. J. Peasant Stud. 39, 873–898. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.686492

Scartozzi, C. M. (2021). Reframing climate-induced socio-environmental conflicts: a systematic review. Int. Stud. Rev. 23, 696–725. doi: 10.1093/isr/viaa064

Sikor, T., and Lund, C. (2009). Access and property: a question of power and authority. Dev. Change 40, 1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01503.x

Smyth, E., and Vanclay, F. (2024). “Social impacts of land acquisition, resettlement and restrictions on land use, in Handbook of Social Impact Assessment and Management (Edward Elgar Publishing), 355–376. doi: 10.4337/9781802208870.00033

Tran, C. (2024). The current status of compensation, support, and resettlement when the state acquires land for socio-economic development. Int. J. Law Polit. Stud. 6, 27–34. doi: 10.32996/ijlps.2024.6.1.4

Tsikata, D., and Seini, W. (2004). Identities, inequalities and conflicts in Ghana. CRISE Working Paper.

Ubink, J. (2008). In the Land of the Chiefs: Customary Law, Land Conflicts, and the Role of the State in Peri-Urban Ghana. Leiden, Netherlands: University of Leiden. doi: 10.5117/9789087280413

Uisso, A. M., and Tanrıvermiş, H. (2025). Impediments to urban land development and transformation in tanzania: evaluating conventional approaches and proposing innovative solutions. Surv. Rev. 57, 85–96. doi: 10.1080/00396265.2024.2370599

UN (2007). Enhancing Urban Safety and Security: Global Report on Human Settlements 2007. Earthscan: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

Van Leeuwen, M. (2010). Crisis or continuity? Framing land disputes and local conflict resolution in burundi. Land Use Policy 27, 753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.10.006

Wiles, R., Crow, G., Heath, S., and Charles, V. (2008). The management of confidentiality and anonymity in social research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 11, 417–428. doi: 10.1080/13645570701622231

Wolford, W. (2010). This Land is Ours Now: Social Mobilization and the Meanings of Land in Brazil. Durham: Duke University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780822391074

World Bank (2017). Environmental and Social Framework: Setting Environmental and Social Standards for Investment Project Financing. Washington, DC:World Bank Publications.

Yaro, J. A. (2010). Customary tenure systems under siege: contemporary access to land in northern Ghana. GeoJournal 75, 199–214. doi: 10.1007/s10708-009-9301-x

Yeboah, E., and Shaw, D. (2013). Customary land tenure practices in Ghana: examining the relationship with land-use planning delivery. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 35, 21–39. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2013.3

Zhu, J., and Tong, D. (2024). Land reform from below: institutional change driven by confrontation and negotiation. J. Urban Aff. 46, 610–623. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2022.2062373

Keywords: compulsory land acquisition, conflict framing, land governance, stakeholder perceptions, conflict escalation, compensation disputes

Citation: Owusu E and Amoakoh AO (2025) Conflict frames associated with state compulsory acquisition of lands in Barekese, Ghana. Front. Sustain. Resour. Manag. 4:1543829. doi: 10.3389/fsrma.2025.1543829

Received: 11 December 2024; Accepted: 10 March 2025;

Published: 31 March 2025.

Edited by:

Iwan Rudiarto, Diponegoro University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Cynthia M. Caron, Clark University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Owusu and Amoakoh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alex Owusu Amoakoh, QS5PLkFtb2Frb2hAbGptdS5hYy51aw==

†ORCID: Evans Owusu orcid.org/0009-0003-3130-0612

Alex Owusu Amoakoh orcid.org/0000-0001-8394-1241

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.