- 1Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA), Strategy, Research and Policy (SRP) Unit, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 2Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

Urban regeneration in South Africa addresses historical spatial inequalities and the growing demand for affordable housing. This study examines the impact of social housing on urban regeneration, with a particular focus on the role of the Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA). The SHRA’s mandate to create integrated urban environments with well-located, affordable, and quality rental homes is central to efforts aimed at promoting spatial justice, economic integration, and social development. A qualitative analysis was conducted, involving a review of policy documents, case studies of key social housing projects, and an evaluation of stakeholder reports from provinces such as Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Eastern Cape. This multi-method approach facilitated an in-depth understanding of the SHRA’s strategies including regulation, investment, and market transformation and their effectiveness in advancing urban regeneration objectives. The findings indicate that the SHRA has significantly expanded the reach of social housing initiatives by increasing the number of regulated units and delivery agents. Strategic placement of projects in economically vibrant areas has contributed to urban densification and more equitable resource allocation. Moreover, social housing has alleviated financial burdens for low- to medium-income households, improved living conditions, and stimulated economic activity and job creation in the construction and real estate sectors. The study underscores that social housing is a vital instrument for urban regeneration in South Africa. The SHRA’s efforts have disrupted apartheid-era spatial patterns and promoted social mobility by fostering inclusive communities. However, challenges such as construction mafias and rental boycotts persist, highlighting the need for enhanced collaboration among stakeholders to ensure project sustainability. Overall, the integration of social housing initiatives with broader urban regeneration strategies is crucial for achieving spatial integration, economic inclusion, and long-term social development.

1 Introduction

The role of social housing in urban regeneration has been a focal point of urban policy and planning in South African cities. Social housing aims to address spatial inequalities and provide affordable housing for low- and middle-income households, contributing significantly to the revitalization of urban areas. This paper seeks to evaluate the impact of social housing on urban regeneration in South African cities, highlighting both the successes and challenges faced in this endeavor. The implementation of social housing projects is viewed as a strategic intervention to combat urban decay and promote socioeconomic development (Gounden, 2010; Harrison et al., 2014).

Urban regeneration in South Africa involves transforming decayed and neglected urban spaces into vibrant and sustainable communities. Social housing plays a crucial role in this transformation by providing well-located, affordable housing options that attract a diverse population, stimulate local economies, and foster community development (Housing Development Agency (HDA) and National Association of Social Housing Organisations (NASHO), 2013). Recent studies emphasize that effective social housing policies can lead to improved access to economic opportunities, enhanced quality of life, and reduced inequalities (Chetty et al., 2016; Giannino and Orabona, 2014). Moreover, social housing initiatives contribute to the physical upgrading of urban environments, addressing issues such as infrastructure decay and inadequate public services (eThekwini Municipality, 2016).

Despite these positive outcomes, the integration of social housing into urban regeneration strategies is not without challenges. Issues such as funding constraints, political will, and the management of social housing units can hinder the success of these projects. Additionally, there is a need for comprehensive policies that not only provide housing but also ensure the availability of essential services and employment opportunities within these regenerated areas (Grodach and Ehrenfeucht, 2016; Peyroux, 2012).

2 Background

Urban regeneration has become a pressing issue in South African cities, particularly in addressing the spatial inequalities and socio-economic divides inherited from the apartheid era. The introduction of social housing has been seen as a key strategy to mitigate these urban challenges by providing affordable housing and fostering inclusive urban development. Social housing not only offers shelter but also aims to create integrated communities with access to essential services and economic opportunities. This approach is critical in transforming previously neglected urban areas into vibrant, sustainable communities (Tissington, 2010; Charlton and Kihato, 2006).

The positive impact of social housing on urban regeneration is well-documented. Social housing projects in South African cities have been associated with improved living conditions, enhanced access to social amenities, and increased economic activities within local communities. Studies have shown that social housing developments can stimulate local economies by attracting new businesses and investments, thus creating jobs and promoting economic growth (Housing Development Agency (HDA) and National Association of Social Housing Organisations (NASHO), 2013; Wilkinson et al., 2014). Furthermore, social housing initiatives often include infrastructural improvements such as better roads, schools, and healthcare facilities, which contribute to the overall upliftment of urban areas (Royston, 2009).

However, the implementation of social housing as a tool for urban regeneration is fraught with challenges. One of the significant issues is the sustainability of these projects amidst financial and administrative constraints. There is a need for robust policies and consistent funding to ensure that social housing projects can meet the demands of urban populations and contribute effectively to urban regeneration (Huchzermeyer, 2014). Moreover, the success of social housing depends on comprehensive planning and community involvement to ensure that these developments are well-integrated into the urban fabric and address the specific needs of residents (Rebel Group South Africa, Project Shop, and Progressus Research and Development, 2023; Rust et al., 2009).

3 Literature review

Social housing in South Africa has been instrumental in addressing the housing needs of low- to medium-income households, particularly in urban areas where the demand for affordable housing is high. The Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA) plays a pivotal role in ensuring the provision of quality rental housing, thereby contributing to urban regeneration and economic integration.

3.1 The concept of social housing

Social housing, as defined by Tissington (2010), encompasses government-subsidized housing programs aimed at providing affordable accommodation to low-income households. This concept is vital in addressing housing shortages and improving living conditions for marginalized communities (Adebayo et al., 2022). Recent studies have highlighted the significance of social housing in fostering inclusive urban development (Turok and Visagie, 2018; Ben Haman et al., 2021).

3.2 Urban regeneration

Urban regeneration refers to the process of revitalizing deteriorated urban areas through redevelopment and investment (Giannino and Orabona, 2014). It aims to improve physical infrastructure, boost economic activities, and enhance the quality of life for residents (Roberts et al., 2017). The role of social housing in urban regeneration has been a focal point in contemporary urban studies (Mahlangu, 2022).

3.3 Social housing and urban regeneration: an overview

Social housing is a cornerstone of urban regeneration efforts, particularly in addressing the socio-economic divides and urban decay inherited from apartheid in South Africa. Urban regeneration involves the revitalization of urban areas to improve living conditions, attract investment, and stimulate economic growth. Social housing contributes significantly to this process by integrating low-income households into urban areas and promoting socio-economic inclusivity (Scheba et al., 2021). The Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA) has been instrumental in advancing social housing in South Africa, aiming to provide affordable rental housing while addressing spatial inequalities (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b).

3.4 Impact on economic development

The economic benefits of social housing in urban regeneration are multifaceted. Social housing projects create jobs during construction and through increased demand for local services and businesses. Social housing projects can stimulate local economies by creating jobs during construction and through subsequent economic activities (Social Housing Regulatory Authority and Genesis Analytics, 2018). For example, Vásquez-Vera et al. (2021) found that social housing developments in Barcelona led to increased local economic activities and improved employment rates among residents. In South Africa, the SHRA’s social housing projects have similarly revitalized local economies and attracted investment in urban areas (Housing Development Agency (HDA) and National Association of Social Housing Organisations (NASHO), 2013). A study by Fayomi et al. (2024) and Ludick et al. (2021) demonstrated that social housing developments in Johannesburg led to increased employment opportunities and economic growth in adjacent areas. In the 2022/23 fiscal year, SHRA’s projects generated approximately 7,990 job opportunities, showcasing the significant economic impact of these initiatives (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). Furthermore, improved housing conditions often lead to higher property values and attract private investments (SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd, 2020).

3.5 Social cohesion and community development

Social housing projects play a crucial role in promoting social cohesion and community development. By offering affordable housing in mixed-income developments, social housing reduces social segregation and fosters inclusive communities. Fraser et al. (2011) highlight that social housing enhances social networks, community engagement, and a sense of belonging among residents. In South African cities, these projects have integrated previously marginalized communities into the urban fabric, promoting social cohesion and reducing crime rates (Moolla et al., 2011). The SHRA’s efforts have led to the development of numerous social housing units, with a significant increase in the number of delivery agents managing these units (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). According to Georgiadou and Loggia (2024), residents of social housing projects in Durban reported improved social networks and a sense of community. These developments also enhance access to essential services such as education and healthcare (Visagie et al., 2024).

3.6 Environmental sustainability

Incorporating environmental sustainability into social housing projects is crucial for promoting long-term urban regeneration. The integration of green building practices in social housing projects is crucial for promoting environmental sustainability (Umbro, 2016). Recent initiatives in Cape Town have demonstrated the feasibility of incorporating renewable energy and water-saving technologies in social housing (Gupta et al., 2015). These efforts align with broader urban regeneration goals of creating sustainable and resilient cities (Haqi, 2016). Sustainable housing initiatives reduce environmental impact and enhance the quality of life for residents through energy efficiency, water conservation, and the use of sustainable building materials (du Plessis, 2019). The SHRA has integrated green building practices into its social housing projects, aiming to reduce carbon footprints and promote resource efficiency. For instance, projects such as Belhar Gardens in Cape Town include solar water heating, energy-efficient lighting, and rainwater harvesting systems, which contribute to environmental sustainability and lower utility costs for residents (Madulammoho Housing Association, 2016). These efforts align with global trends in sustainable urban development and underscore the importance of integrating environmental considerations into housing policies (UN-Habitat, 2020).

3.7 Policy and governance

Effective policy frameworks and governance structures are essential for the successful implementation of social housing projects (DeGood et al., 2024; Marsh, 2018). The National Housing Code of South Africa outlines key strategies for integrating social housing into urban planning (Department of Human Settlements, 2019). However, challenges such as bureaucratic delays and inadequate funding often hinder progress. The Social Housing Act of 2008 and the establishment of the SHRA have provided a robust framework for regulating and supporting social housing projects in South Africa. The SHRA ensures compliance with regulations, provides financial assistance, and promotes the development of a sustainable social housing environment (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). Effective governance involves the collaboration of various stakeholders, including local municipalities, provincial governments, and private sector partners, to ensure the successful implementation and sustainability of social housing projects (Huchzermeyer, 2014).

3.8 SHRA and its contribution

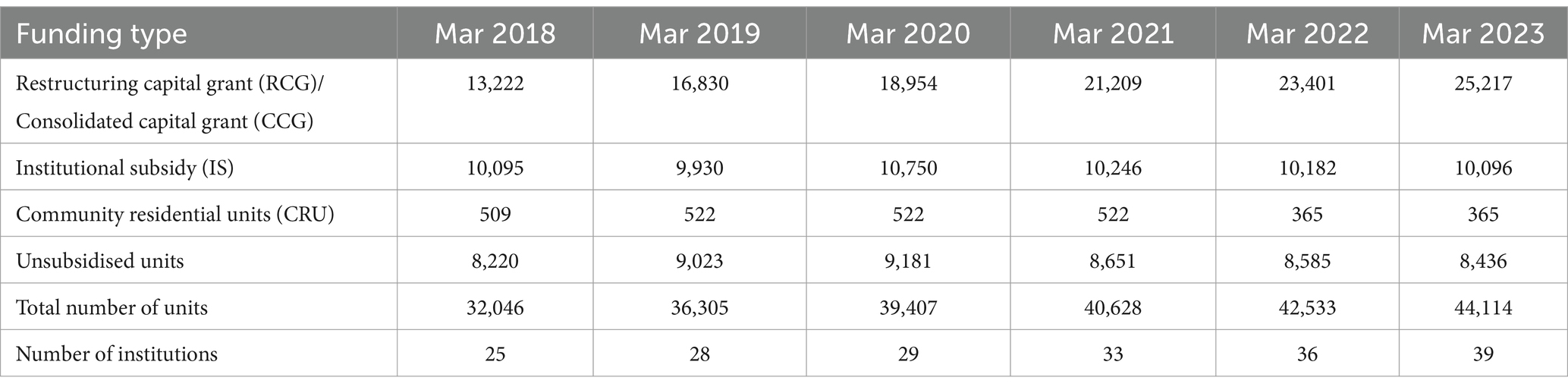

The SHRA plays a vital role in ensuring the provision of quality social housing and supporting urban regeneration. Established under the Social Housing Act of 2008, the SHRA’s mandate includes regulating and investing in social housing institutions to ensure they deliver quality housing and contribute to urban regeneration (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). The SHRA’s initiatives have resulted in a 38% increase in the portfolio of units under regulation from 2018 to 2023, with over 44,114 units managed by 39 institutions by the end of March 2023 (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). These efforts demonstrate the SHRA’s significant contribution to addressing the housing crisis and promoting sustainable urban development.

3.9 Success stories of social housing projects

Several social housing projects in South Africa stand out as success stories. For instance, the Johannesburg Social Housing Company (JOSHCO) has successfully delivered numerous housing projects, transforming dilapidated areas into vibrant communities. The Belhar Gardens development in Cape Town is another example, providing affordable housing integrated with community facilities, promoting social cohesion and economic development (City of Cape Town, 2023). These projects exemplify the potential of social housing to drive urban regeneration and improve the quality of life for residents.

3.10 Progress of social housing delivery

The progress of social housing delivery in South Africa has been commendable, despite various challenges. According to the SHRA’s 2022/23 Annual Report, 3,182 social housing units were completed against a target of 3,000, showcasing the organization’s commitment to meeting housing demands (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). The report also highlights that over 44,114 units are under regulation, managed by 39 institutions, indicating substantial progress in social housing delivery. However, the demand for social housing continues to exceed supply, necessitating ongoing investment and policy support to address the growing needs of urban populations (Department of Human Settlements, 2019).

3.11 Educational opportunities

Access to quality education is a critical component of social housing projects. Social housing developments located near schools and educational facilities provide children with better opportunities for academic success, breaking the cycle of poverty and promoting socio-economic mobility (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b; Johannesburg Housing Company, 2022). By integrating educational opportunities into social housing projects, policymakers can ensure that residents have access to the resources needed for personal and professional development (South African Cities Network, 2011).

3.12 Safety and security

Safety and security are paramount in social housing projects. Well-designed social housing developments incorporate security measures such as controlled access, surveillance systems, and community policing to ensure residents’ safety. For instance, the Social Housing (Regulation) Act 2023 in the UK emphasizes enhancing safety standards in social housing, granting regulators increased authority to enforce compliance and improve living conditions for tenants (UK Government, 2023). Addressing safety concerns not only protects residents but also fosters a sense of community and stability, essential for successful urban regeneration (Fraser et al., 2011).

3.13 Urban aesthetics and design

Urban aesthetics and design play a vital role in the success of social housing projects. Attractive, well-designed housing developments enhance the visual appeal of urban areas and contribute to residents’ pride and satisfaction with their living environment (Lees et al., 2016). Incorporating sustainable design principles, such as energy-efficient buildings and green spaces, further enhances the environmental and aesthetic value of social housing projects (du Plessis, 2019).

3.14 Long-term sustainability

Long-term sustainability is a critical goal for social housing projects. This involves not only the environmental sustainability of housing developments but also their economic and social sustainability. Ensuring that social housing projects are financially viable, well-maintained, and able to adapt to changing socio-economic conditions is essential for their long-term success (UN-Habitat, 2020). Policies and practices that support ongoing community engagement, maintenance, and financial management are crucial for achieving sustainable social housing (du Plessis, 2019).

3.15 Challenges in social housing implementation

Despite its benefits, social housing faces numerous challenges, including land availability, funding constraints, and resistance from existing communities (Onatu, 2011; Madisha and Khumalo, 2021; Weje et al., 2018). Studies highlighted the difficulties in acquiring suitable land for housing projects in densely populated urban areas. Additionally, securing consistent funding remains a significant hurdle (SDS Software, 2024; Mazhinduka et al., 2020). Rental boycotts, where tenants withhold rent in protest, pose significant risks to the financial stability of social housing projects (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2024). Additionally, the phenomenon of “construction mafias,” where criminal groups extort money from developers and disrupt construction sites, severely impacts project timelines and budgets (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). These challenges highlight the need for robust security measures, effective conflict resolution strategies, and strong community engagement to ensure the success and sustainability of social housing projects (Akinsulire et al., 2024).

4 Methodology

The methodology employed for this study was primarily a desktop research approach, leveraging academic and policy documents, reports, and statistical data to assess the impact of social housing on urban regeneration in South African cities. This section provides an in-depth explanation of the targeted population, sampling method, data analysis methods, ethical considerations, and the geographical location of the study.

4.1 Targeted population

The targeted population for this study includes:

• Urban Residents: Beneficiaries of social housing projects, particularly those in low- to middle-income groups.

• Policy Makers and Practitioners: Representatives from the Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA), the Department of Human Settlements, and municipal governments.

• Stakeholders in Urban Development: Researchers, private developers, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) involved in urban regeneration and social housing initiatives.

4.2 Sampling method

Given the desktop research design, the study employed a purposive sampling method to select data sources. Documents and reports were included based on the following criteria:

• Relevance to social housing and urban regeneration in South Africa.

• Credibility and authority of the sources, such as government publications, SHRA annual reports, and peer-reviewed articles.

• Temporal proximity, with a focus on documents published in the last decade to ensure current relevance.

• Geographic representation, ensuring data from all major provinces involved in social housing initiatives, such as Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Western Cape, were included.

4.3 Data analysis methods

The study utilized a thematic content analysis approach, focusing on key themes like spatial justice, economic integration, and community involvement. The analysis followed these steps:

• Data Extraction: Relevant information was extracted from selected documents and organized according to predefined themes.

• Trend Analysis: Statistical data, such as SHRA reports, were used to identify patterns in social housing delivery, job creation, and community impacts.

• Synthesis and Interpretation: Findings were synthesized to draw connections between social housing projects and their impact on urban regeneration, supported by visual aids like tables and figures.

4.4 Ethical considerations

Although the study relied on secondary data, ethical considerations were addressed as follows:

• Credibility of Sources: Only publicly available and peer-reviewed data were used to ensure the reliability of findings.

• Acknowledgment of Sources: All data sources were cited appropriately to maintain academic integrity.

• Data Privacy: No personal or sensitive data were accessed, ensuring compliance with ethical guidelines for research.

4.5 Geographical location of the study

The study focused on urban areas within South Africa, with particular emphasis on:

• Gauteng: As the economic hub of South Africa, Gauteng has the highest number of social housing projects.

• KwaZulu-Natal: Known for its growing urban population and ongoing regeneration efforts.

• Western Cape: A region where social housing projects integrate green building practices. The geographical scope allowed for a comprehensive understanding of regional disparities and commonalities in the implementation and impact of social housing initiatives.

4.6 Limitations acknowledgment

Potential limitations of the secondary data, such as inherent biases in government reports or incomplete regional data, were acknowledged and mitigated by:

• Supplementing with broader literature to fill gaps.

• Clearly identifying limitations in the study to provide transparency.

5 Findings and discussion

The findings of this study draw from the SHRA Annual Report 2022/23, highlighting the significant impact of social housing on urban regeneration in South African cities.

5.1 Social housing delivery and distribution

The SHRA has made notable progress in social housing delivery across South African provinces. The report shows that Gauteng is the largest contributor with 115 projects, accounting for 53% of the total units delivered, followed by KwaZulu-Natal with 25 projects (13%) and the Western Cape with 16 projects (11%). The total number of units under regulation has increased from 32,046 in 2018 to 44,114 in 2023, representing a 38% increase in the portfolio (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). This growth is indicative of the concerted efforts to address the housing deficit in urban areas (see Table 1).

Figure 1 shows the analysis of unit delivery from 2018/19 to 2022/23 which reveals significant trends in the completion and tenancy of social housing units in South Africa.

5.1.1 Units completed

In 2018/19, the number of units completed stood at 2,471, indicating a solid start for the period. This number significantly increased to 4,012 units in 2019/20, reflecting a robust effort to ramp up housing delivery. However, the completion rate drastically decreased to 1,856 units in 2020/21, likely due to the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and related lockdowns. A recovery was noted in 2021/22 with 2,771 units completed, showing resilience and a return to improved delivery capabilities post-pandemic. The positive trend continued in 2022/23 with 3,182 units completed, reaching the highest point since 2019/20.

5.1.2 Units tenanted

Units tenanted in 2018/19 were 2,284, slightly lower than the units completed. The number of tenanted units increased to 3,010 in 2019/20, maintaining a close relationship with the completion rate. However, there was a significant drop to 985 units tenanted in 2020/21, reflecting the impact of the pandemic on not just construction but also occupancy rates. An improvement was seen in 2021/22 with 2,057 units tenanted, showing recovery but still lagging behind the number of completed units. The number of units tenanted further improved to 2,595 in 2022/23, continuing the positive trend toward recovery.

6 Implications and discussion

The data demonstrates the resilience and adaptive capacity of the social housing sector in South Africa, despite significant disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The sharp decline in both completed and tenanted units in 2020/21 underscores the severe impact of the pandemic on the construction and housing sectors. However, the subsequent recovery in 2021/22 and 2022/23 highlights effective strategies and interventions implemented to regain momentum.

6.1 Economic impact

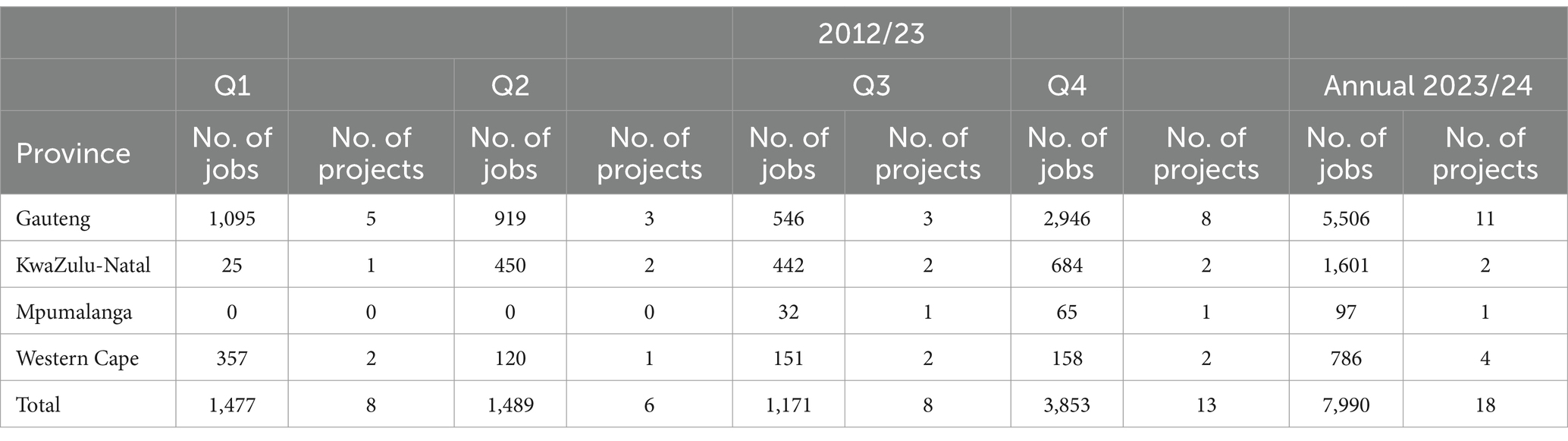

Social housing projects have generated substantial economic benefits, particularly in job creation. In the 2022/23 fiscal year, social housing projects created approximately 7,990 jobs. Gauteng, with its extensive number of projects, created the most jobs (6,505), followed by the Western Cape (1,291) and Eastern Cape (837) (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2023a,b). This job creation is crucial in reducing unemployment and stimulating local economies, thus contributing to overall urban regeneration (refer to Table 2).

6.2 Safety and security

Social housing projects have improved safety and security in urban areas. By providing stable housing and fostering community cohesion, these projects help reduce crime rates and create safer neighborhoods. The integration of security measures, such as community policing and secure building designs, further enhances the safety of residents (Figure 2).

6.3 Social cohesion and environmental sustainability

Social housing has played a vital role in enhancing social cohesion by integrating diverse communities and reducing social segregation. The SHRA has integrated green building practices, such as solar water heating, energy-efficient lighting, and rainwater harvesting, into many of its projects (see Figure 3).

The unit delivery statistics from 2018/19 to 2022/23 reveal critical insights into the dynamics of social housing delivery in South Africa. Despite significant challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the sector has shown considerable resilience and capacity for recovery. Continued focus on adaptive strategies, robust policy frameworks, and community involvement will be essential for sustaining and enhancing the impact of social housing on urban regeneration.

7 Conclusion and recommendations

7.1 Conclusion

The analysis of social housing unit delivery from 2018/19 to 2022/23 highlights the significant impact of these initiatives on urban regeneration in South African cities. Despite the severe disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the sector demonstrated resilience and adaptive capacity, evidenced by the substantial recovery in unit completions and tenancies post-pandemic. The variations in delivery statistics across different provinces underscore both the achievements and the challenges faced by the Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA) and other stakeholders. Key successes in provinces like Gauteng and the Western Cape contrast with the underperformance in regions such as the Free State and Northern Cape, indicating the need for tailored strategies to address regional disparities.

Overall, the data underscores the vital role of social housing in fostering economic development, promoting social cohesion, and enhancing environmental sustainability. However, persistent challenges such as funding limitations, bureaucratic delays, and the activities of “construction mafias” continue to hinder the full realization of social housing benefits. Addressing these issues is crucial for achieving the broader goals of urban regeneration and improving the quality of life for low- to medium-income households in South Africa.

7.2 Recommendations

To foster meaningful transformation within the social housing sector in South Africa, this study proposes actionable and specific recommendations. These are structured to align with the key challenges identified in the research and aim to provide a roadmap for stakeholders to drive progress.

7.3 Integrated policy reforms

An immediate priority for the sector is the alignment of housing policies with broader urban regeneration objectives. This involves a comprehensive review of existing frameworks, focusing on promoting spatial justice, sustainability, and economic inclusivity. The Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA), in collaboration with the Department of Human Settlements and provincial governments, should spearhead this effort. The review process should conclude within a year to ensure timely implementation. By engaging urban planners and academic experts, this initiative will ensure policies are not only consistent but also adaptable to regional needs.

7.4 Innovative financing mechanisms

The establishment of sustainable financing solutions is essential to overcome funding constraints in social housing projects. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can provide a practical pathway, encouraging private sector investment through tax incentives, co-financing models, and shared risk frameworks. SHRA must lead these efforts by drafting a PPP framework that attracts private developers and financial institutions. Piloting these partnerships within 18 months would demonstrate feasibility and encourage broader adoption across the sector.

7.5 Community-centered development

A participatory approach to housing development is vital to ensure that projects align with the needs and aspirations of local communities. Municipalities, working alongside non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community-based organizations (CBOs), should establish mechanisms for regular community engagement. This includes soliciting input during project design and providing platforms for ongoing feedback throughout implementation. Piloting this approach in key urban areas within a year will showcase its potential to foster trust, ownership, and long-term sustainability.

7.6 Capacity building and skills development

Equipping municipal officials and housing practitioners with the necessary skills to manage and execute sustainable projects is critical for the sector’s success. Training programs tailored to address financial management, conflict resolution, and green building practices should be developed by SHRA in partnership with academic and professional training institutions. These programs must be implemented within 6 months, ensuring immediate upskilling of key personnel. Continued professional development should be embedded into the sector’s operations to maintain high standards and adaptability to emerging challenges.

7.7 Leveraging digital technology for efficiency

The adoption of technology can significantly enhance the efficiency of housing delivery and management. SHRA should invest in developing a centralized digital platform to streamline application processes, monitor project progress, and facilitate real-time communication among stakeholders. This platform, designed in collaboration with IT service providers, must include features for tracking housing metrics, such as occupancy rates, project timelines, and tenant satisfaction. A phased deployment beginning within the next 12 months will ensure robust testing and smooth integration.

7.8 Enhanced monitoring and evaluation

A robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework is essential to measure the effectiveness of social housing initiatives and guide continuous improvement. This framework should assess not only the financial and operational aspects of projects but also their social and environmental impacts. SHRA, supported by independent auditors and academic institutions, should develop standardized evaluation tools to be implemented across all housing projects within a year. Regular evaluations will ensure accountability, transparency, and alignment with sector goals.

7.9 Strengthening stakeholder collaboration

The transformation of the social housing sector requires coordinated efforts among diverse stakeholders, including SHRA, government bodies, private developers, and community organizations. Establishing a formalized stakeholder forum will facilitate knowledge-sharing, address conflicts, and ensure alignment on priorities. Quarterly meetings, supported by actionable agendas, will maintain momentum and foster a culture of collaboration.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adebayo, P., Ndinda, C., and Ndhlovu, T. (2022). South African cities, housing precarity and women’s inclusion during COVID-19. Agenda 36, 16–28. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2022.2057027

Akinsulire, A. A., Idemudia, C., Okwandu, A. C., and Iwuanyanwu, O. (2024). Sustainable development in affordable housing: policy innovations and challenges. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 11, 090–104. doi: 10.30574/msarr.2024.11.2.0112

Ben Haman, O., Hulse, K., and Jacobs, K. (2021). Social inclusion and the role of housing: handbook of Social Inclusion. Cham: Springer.

Charlton, S., and Kihato, C. (2006). “Reaching the poor: an analysis of the influences on the evolution of South Africa’s housing programme” in Democracy and delivery: urban policy in South Africa (Pretoria: HSRC Publishers), 252–282.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., and Katz, L. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 106, 855–902. doi: 10.1257/aer.20150572

City of Cape Town (2023). Integrated human settlements sector plan 2022/23–2026/27: 2023/24 review. Cape Town, South Africa: City of Cape Town.

DeGood, K., Weller, C. E., Ballard, D., and Vela, J. (2024). A new vision for social housing in America. Washington, D.C., United States: Center for American Progress.

Department of Human Settlements (2019). Annual performance plan 2019/20. Pretoria: Government Printer.

du Plessis, C. (2019). Sustainability and resilience in the built environment. United Kingdom: Routledge.

eThekwini Municipality. (2016). About eThekwini Municipality. Available at: https://www.durban.gov.za/pages/government/about-ethekwini (Accessed 30 June 2024])

Fayomi, G. U., Onyari, E. K., and Mini, S. E. (2024). Evaluating social housing potential for low-income urban dwellers in Johannesburg. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 9:100737. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2024.100737

Fraser, J., DeFilippis, J., and Bazuin, J. T. (2011). “HOPE VI: calling for modesty in its claims,” In Mixed communities. eds. G. Bridge, T. Butler, and L. Lees (Bristol, United Kingdom: Policy Press), 209–230.

Georgiadou, M. C., and Loggia, C. (2024). Community-led vs. subsidised housing: lessons from informal settlements in Durban. London: Routledge.

Giannino, M. A., and Orabona, F. (2014). Social housing in urban regeneration: regeneration heritage existing building: methods and strategies. TeMA J. Land Use Mob. Environ. Spec. Issue 2014, 477–486. doi: 10.6092/1970-9870/2513

Gounden, K. (2010). Waterfront development as a strategy for urban renewal: a case study of the Durban point waterfront development project. Doctoral dissertation. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Grodach, C., and Ehrenfeucht, R. (2016). Urban revitalization: Remaking cities in a changing world. London: Routledge.

Gupta, R., Gregg, M., Lalande, C., and Herda, G. (2015). Green building interventions for social housing. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

Haqi, F. I. (2016). Sustainable urban development and social sustainability in the urban context. EMARA Indon. J. Archit. 2, 21–26. doi: 10.29080/eija.v2i1.15

Harrison, P., Gotz, G., Todes, A., and Wray, C. (2014). Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Housing Development Agency (HDA) and National Association of Social Housing Organisations (NASHO) (2013). Reviving our inner cities: social housing and urban regeneration in South Africa. Johannesburg: Housing Development Agency.

Huchzermeyer, M. (2014). Housing in South Africa: policy and practice. In J. Bredenoord, P. Lindert van, and P. Smets (Eds.), Affordable housing in the urban global south: Seeking sustainable solutions. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Johannesburg Housing Company. (2022). Why affordable housing positively impacts education in South Africa. Available at: https://www.jhc.co.za/news/why-affordable-housing-positively-impacts-education-south-africa (Accessed July 1, 2024).

Larsen, L., Harlan, S. L., Bolin, B., Hackett, E. J., Hope, D., Kirby, A., et al. (2016). Bonding and bridging: understanding the relationship between social capital and civic action. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 24, 64–77. doi: 10.1177/0739456X04267181

Lees, L., Shin, H. B., and López-Morales, E. (2016). Planetary gentrification. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ludick, A., Dyason, D., and Fourie, A. (2021). A new affordable housing development and the adjacent housing-market response. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 24:a3637. doi: 10.4102/sajems.v24i1.3637

Madisha, M. G., and Khumalo, P. (2021). “Social housing policy implementation challenges in South African local municipalities” in 6th Annual International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives (Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa).

Madulammoho Housing Association. (2016). Belhar Gardens. Available at: https://www.mh.org.za/project/belhar-gardens/ (Accessed July 19, 2024).

Mahlangu, R. C. (2022). The role of social housing in urban regeneration: The case of Johannesburg. Master’s dissertation,. Pretoria: University of South Africa.

Marsh, A. (2018). Social housing governance: an overview of the issues and evidence. Bristol, United Kingdom: Social Housing Policy Working Group, University of Bristol.

Mazhinduka, T. A., Burger, M., and van Heerden, A. (2020). Financing of social housing investments in South Africa. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

Moolla, R., Kotze, N., and Block, L. (2011). Housing satisfaction and quality of life in RDP houses in Braamfischerville, Soweto: a south African case study. Urbani Izziv 22, 138–143. doi: 10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2011-22-01-005

Onatu, G. (2011). The challenge facing social housing institutions in South Africa: a case study of Johannesburg. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg.

Peyroux, E. (2012). Legitimating business improvement districts in Johannesburg: a discursive perspective on urban regeneration and policy transfer. Eur Urban Reg Stud 19, 181–194. doi: 10.1177/0969776411420034

Rebel Group South Africa, Project Shop, and Progressus Research and Development (2023). Design and implementation evaluation of the integrated residential development programme: summary report. Pretoria: The Presidency Department of Performance Monitoring and Evaluation.

Roberts, P., Sykes, H., and Granger, R. (2017). Urban Regeneration. 2nd Edn. London: SAGE Publications.

Royston, L. (2009). How tenure security can increase access to economic opportunities for poor people. Pretoria: Urban LandMark.

Rust, K., Zack, T., and Napier, M. (2009). How a focus on asset performance might help ‘breaking new ground’ contribute towards poverty reduction and overcome the two-economies divide. Town Reg. Plann. 54, 50–59. doi: 10.38140/trp.v54i0.604

Scheba, A., Turok, I., and Visagie, J. (2021). The role of social housing in reducing inequality in south African cities. Research paper no. 202. Paris: Agence Française de Développement.

SDS Software (2024). What are the challenges in funding social housing? Available at: https://s-d-s.co.uk/what-are-the-challenges-in-funding-social-housing/ (Accessed November 22, 2024).

SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd (2020). Economic impacts of social housing investment: final report prepared for community housing industry association. Melbourne: SGS Economics and Planning.

Social Housing Regulatory Authority. (2023b). The benefits of social housing. Available at: https://www.shra.org.za/the-benefits-of-social-housing/ (Accessed June 22, 2024).

Social Housing Regulatory Authority (2024). Overcoming rental boycotts: a new strategic direction for South Africa's social housing sector. Available at: https://www.shra.org.za/overcoming-rental-boycotts-a-new-strategic-direction-for-south-africas-social-housing-sector (Accessed June 30, 2024).

Social Housing Regulatory Authority and Genesis Analytics (2018). Socio-economic and spatial restructuring impact of social housing. Pretoria: SHRA.

Tissington, K. (2010). A review of housing policy and development in South Africa since 1994. Johannesburg: Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa.

Turok, I., and Visagie, J. (2018). Inclusive urban development in South Africa: what does it mean and how can it be measured? IDS working paper no. 512. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

UK Government. (2023). Social Housing (Regulation) Act 2023. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/36/contents (Accessed 10 July 2024).

Umbro, M. (2016). Social housing: the environmental sustainability on more dimensions. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 223, 251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.359

UN-Habitat (2020). World cities report 2020: the value of sustainable urbanization. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

Vásquez-Vera, H., León-Gómez, B.B., Palència, L., Pérez, K., and Borrell, C. (2021). Health effects of housing insecurity and unaffordability in the general population in Barcelona, Spain. J. Urban Health, 98, pp. 496–504. Springer.

Visagie, J., Turok, I., and Scheba, A. (2024). Social housing and upward mobility in South Africa: an assessment of household outcomes. Urban Forum 35, 377–404. doi: 10.1007/s12132-023-09504-z

Weje, I. I., Obinna, V. C., and Oboh, F. A. (2018). Challenges of social housing implementation and consumer satisfaction in Rivers state, Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 8, 426–430. doi: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.10.2018.p8255

Keywords: social housing, urban regeneration, spatial integration, affordable housing, economic inclusion

Citation: Ngema NN, Bokhari A and Mbanga SL (2025) Assessing the impact of social housing on urban regeneration in South African cities. Front. Sustain. Cities. 7:1468964. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1468964

Edited by:

Silvia Mazzetto, Prince Sultan University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Hasim Altan, Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University, Saudi ArabiaLiudmila Cazacova, American University of Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2025 Ngema, Bokhari and Mbanga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Noxolo N. Ngema, bm94b2xvbkBzaHJhLm9yZy56YQ==

Noxolo N. Ngema

Noxolo N. Ngema Ahmed Bokhari1

Ahmed Bokhari1 Sijekula L. Mbanga

Sijekula L. Mbanga