95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Cities , 17 March 2025

Sec. Innovation and Governance

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2025.1450933

Ludger Niemann1,2*

Ludger Niemann1,2* Thomas Hoppe1,3

Thomas Hoppe1,3Since 1994, Colombian mayors have been legally held accountable for election promises and goal achievement in office; non-compliance or underperformance may trigger recalls. In several Latin American countries, civil-society coalitions striving for urban sustainability have successfully lobbied for adopting similar rules in more than 60 cities. We conducted a longitudinal, comparative case study, based on documents and 16 interviews, to study the characteristics and effects of the accountability mechanisms emerging in Bogotá, Córdoba, Guadalajara, and São Paulo. Results show that goal-setting and reporting requirements are beneficial to urban governance in terms of increasing programmatic policies, intra-municipal cooperation, civil society involvement, and citizen participation. However, unintended consequences, including a rigid, short-term focus on targets at the expense of long-term objectives, were also observed. This suggests trade-offs concerning accountability and flexibility and dilemmas in the choice of indicators; outcome-based targets foster long-term, holistic policymaking yet output targets align more easily to local government competencies and citizen demands. The engagement of strong local civil society organisations facilitates the effective implementation of mayoral accountability mechanisms. Our findings offer insights to practitioners and researchers of democratic innovations and international policy frameworks including localisation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The design of accountability mechanisms at the city level in diverse contexts and alternatives to the dominant model of voluntary goal-setting require further attention and research.

In international policy discussions, two ideas have become mainstream in recent decades: the world needs sustainable urban governance, and sustainable urban governance needs goals and indicators (Ferreira da Cruz et al., 2019). Since the 1990s, then promoted by the UN’s “Agenda 21,” many cities in Europe, North America, and other world regions have witnessed the emergence of sustainability monitoring initiatives run by municipalities or civil society organisations (Sharifi, 2020; Wray et al., 2017). Initially, a bottom-up approach of selecting indicators based on local priorities was more prevalent; in recent years, the “top-down” variant of referring to standardised frameworks (such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or other indicator sets including ISO’s, 2014) has become more common. In these three decades of goals gaining a central role in urban sustainability governance, one constant in most countries has been the reliance on aspirational goals, non-committal monitoring of progress, and voluntary reviews by interested parties. Some of these voluntary efforts have had positive effects by influencing a city’s and country’s sustainability discourse, data availability, and institutional capacities (Lehtonen et al., 2016; Ortiz-Moya and Reggiani, 2023). This is similar to the SDG framework itself, which is also designed as a non-binding agreement (Aust and du Plessis, 2018; Biermann et al., 2017) that brought discursive benefits (Biermann et al., 2022) but shows bleak prospects in terms of actual goal achievement (Wu et al., 2023; Zeng et al., 2020).

The trend towards voluntary, non-binding goal-setting arrangements in (inter) national sustainability governance contrasts with an alternative development that also originated in the 1990s and gained prominence in Latin America. In 1994, Colombia introduced legal obligations for mayors to be held accountable for election promises and goal achievement in office; non-compliance or under-performance may trigger recalls. As depicted in Figure 1, this accountability mechanism addresses the electoral-administrative cycle by requiring candidates to write explicit manifestos, elected mayors to formalise plans with goals, and mayors to report on goal achievement.

According to its proponents (Bravo, 2019; Programa Cidades Sustentáveis, 2020), these new accountability rules should have two major clusters of benefits: One is increased government performance resulting from more programmatic policymaking, less corruption, and less clientelist politics; the other is better functioning (local) democracy resulting from more citizen participation and trust. The combined effects are expected to lead to a more effective “sustainability governance” at city level. To what extent does this innovation (belonging to “Latin America’s experimentalist vocation” (Pogrebinschi, 2018) yet hardly known in other parts of the world), deliver on these promises?

The extant literature contains few answers. Internationally, there are studies about SDG localisation and urban governance (e.g., Morita et al., 2020; Valencia et al., 2019) and some, mainly US-based findings about the relationship between community indicators and government performance systems (Ammons and Madej, 2017; de Lancer Julnes et al., 2019; Greenwood, 2008). Numerous scholars call for more case studies about urban sustainability governance, particularly concerning reporting (Bexell and Jönsson, 2019), experiences in the Global South (Bell and Morse, 2018; Meuleman and Niestroy, 2015), and longitudinal research (Giles-Corti et al., 2016). In the absence of systematic documentation that would allow a comprehensive mapping or analysis of practices in various Latin American countries, we opted for a comparative, longitudinal case study on the four cities of Bogotá, Córdoba, Guadalajara, and São Paulo. To structure our research and guide the selection of methods, we developed the following two research questions:

1. What are the formal characteristics of novel performance accountability mechanisms that have evolved among pioneering local governments in Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico?

2. What are the positive and negative effects of these mechanisms in relation to different design features and contextual factors according to a multi-year evaluation?

Our study’s purpose is threefold: (i) to produce an empirical understanding of some performance accountability arrangements for city mayors in Latin America, (ii) to help develop a replicable evaluation framework and research agenda, and (iii) to contribute lessons for policymakers in the field of urban sustainability governance (including the SDGs).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Based on insights from the academic literature, we first present an assessment framework designed to study the characteristics and effects of the emerging accountability mechanisms. The second section details the selection of cases and methods. In the results section, we introduce the case study cities and provide evidence on the above research questions. In the discussion, we reflect on study’s academic merit and make suggestion for further research. The conclusion contains succinct answers to the overall research question.

In line with good practice recommendations to be transparent about the analytical choices made in developing one’s assessment tools (Bovens et al., 2008, p. 234) we developed an assessment framework that aligns with our research questions.

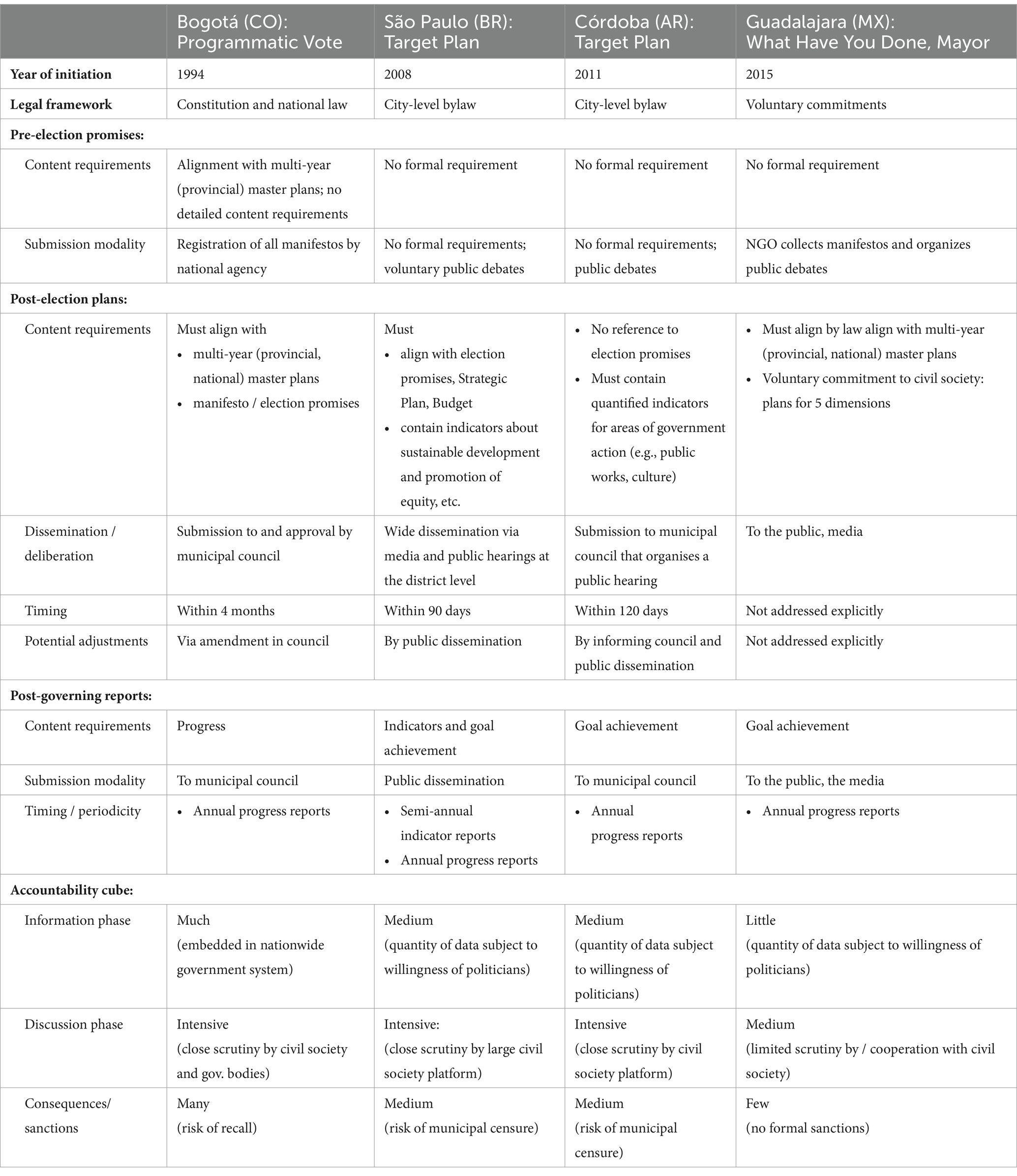

Our first research question—addressing the formal characteristics of the new accountability mechanisms—is mainly descriptive and methodologically straightforward. It can be explored via data found in documents and factual descriptions by local observers who are familiar with the long-term evolution of a city’s system. Since the research object concerns accountability rules, a useful conceptual tool also applied in this study is the “accountability cube” (Brandsma and Schillemans, 2012). This model proposes analysing a given accountability mechanism in terms of three dimensions: How much accountability-relevant information is provided (little vs. much, applicable in the present study to mayoral plans and reports), the level of discussion triggered (intensive vs. non-intensive, applicable in the present study to exchanges between mayors and other stakeholders including the public), and the amount of consequences (few vs. many, applicable, e.g., to the threat of recall).

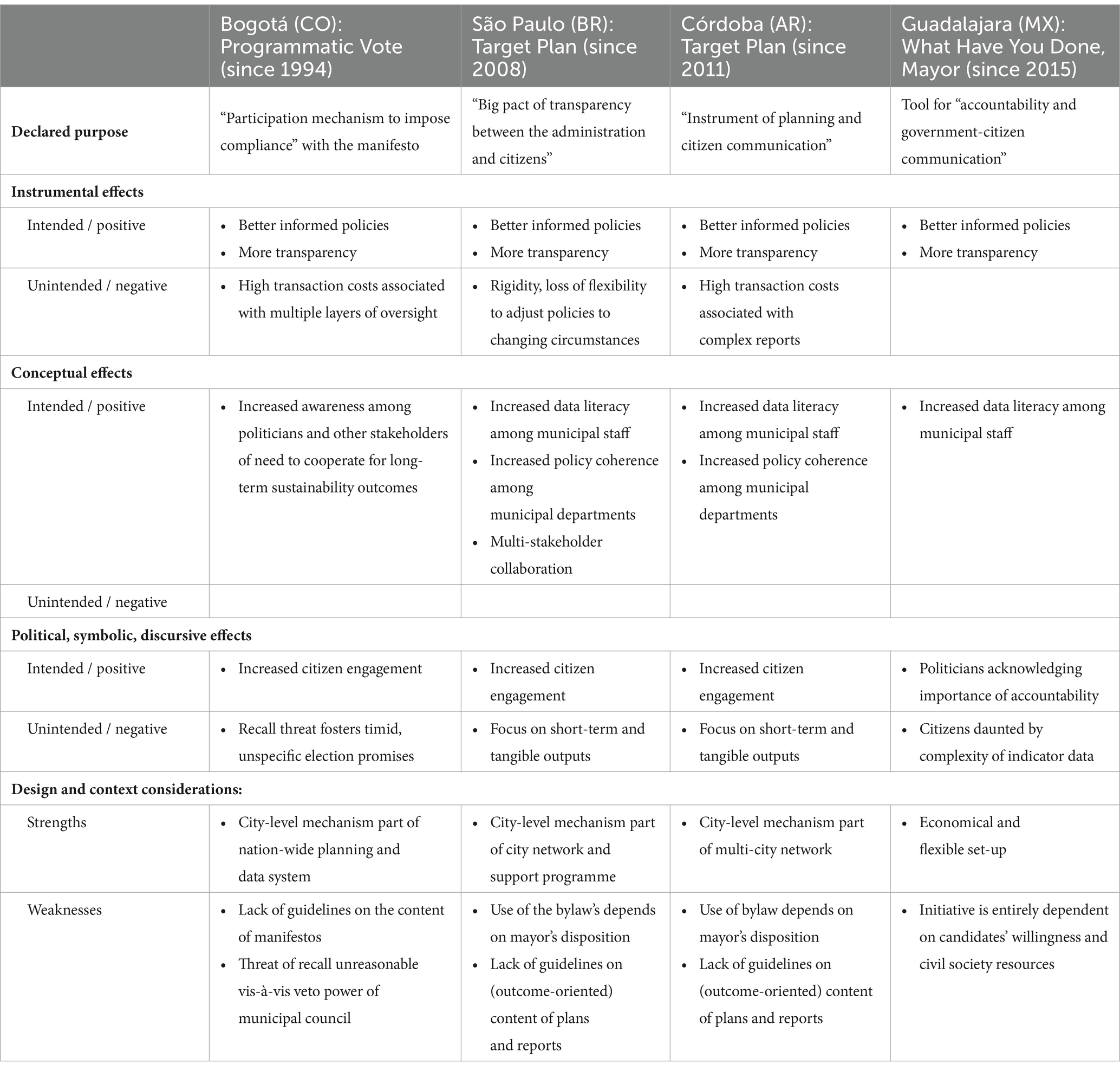

Our second, evaluative research question (on the intended and unintended effects of an accountability mechanism) is both conceptually and methodologically more challenging. In terms of effects, it is legitimate to assess whether the intended benefits such as “less clientelist policymaking” are observed. However, this is conceptually not sufficient as all governance innovations are likely to have intended as well as unintended consequences (Dahler-Larsen, 2013; Lehtonen et al., 2016). Therefore, assessing the relative value of a new mechanism requires probing for diverse effects in various domains. Moreover, research on public accountability and performance management has shown that well-intended innovations can have effects that most observers would classify as negative, e.g., when the publication of performance indicators leads to organisational risk aversion, rigidity, and strategic behaviour known as the “gaming” of targets (Bovens, 2005; De Bruijn, 2002; Pollitt, 2006). To capture this variety of potential effects—positive and negative, intended and unintended—we build on an assessment framework used elsewhere (e.g., Hezri and Dovers, 2006; Lehtonen et al., 2016; Niemann and Hoppe, 2018) that distinguishes three main clusters: instrumental, conceptual, and political-symbolic aspects. Instrumental effects would be evident if the accountability mechanism led to more efficient, evidence-informed governmental action (intended and positive) or the gaming of targets (unintended and negative). Typical stakeholders for this type of “use and influence” of goals and indicators are politicians and senior civil servants. The second cluster concerns conceptual effects as potentially evident from organisational learning and intra-governmental collaboration (positive) or the emergence of a blame culture (negative). Typically affected are staff of government or civil society organisations. The third cluster concerns political, symbolic, and discursive effects such as more attention to sustainability or citizen trust (positive) or the loss of trust and alienation between the government and citizens. The latter, unintended phenomenon has been described as the “tyranny of light” by Tsoukas (1997). Symbolic “greenwashing” (cf., Velte, 2022) also belongs to this category. Table 1 summarises effects and main stakeholders of the accountability mechanisms as expected on the basis of prior research.

Methodologically, the challenge is that most potential effects are intangible. It is thus difficult to observe them empirically and also hard to attribute them causally to any given intervention. On the matter of citizen trust, for example, population surveys could contain relevant data, yet even if they existed at the city level (which is often not the case), one cannot interpret any changes in trust as evidence of the accountability mechanism being benign or harmful. Ultimately, numerous confounding factors at the national level may have caused the change. One way to deal with these methodological challenges is to combine the analysis of documents with interviews and to select multiple key informants per case to minimise biases and ensure triangulation.

To investigate how the accountability mechanisms play out over time in different contexts, we opted for a longitudinal comparative case analysis using one case from each of four countries (cf., Table 2). Such a research design is appropriate for exploring differences and commonalities in practices and different settings and warrants selecting cases on the basis of “diverse” and ‘influential” sampling criteria (Gerring, 2007). Among the countries screened, Colombia is currently the only one with constitutional performance accountability rules for all subnational governments; in our analysis we included the capital (Bogotá) as case study city in the light of its highly influential citizen observatory “Bogotá Cómo Vamos” (Scrivens and Iasiello, 2010). In Brazil and later Argentina, performance accountability rules were introduced via by-laws at the municipal level. From each country, we selected the city with the longest track record and some academic documentation, namely São Paulo (Cáceres, 2014; Marin, 2016) and Córdoba (Romanutti, 2012b). In Mexico, mayoral performance accountability is not a legal requirement but has been introduced as a voluntary arrangement in two metropolitan areas (Monterrey and Guadalajara) by local civil society organisations (Niemann and Hoppe, 2021). Guadalajara has been subject to prior research (Soto-González, 2020), which justified its selection as a case study. In both Paraguay and Peru, at least one local government has bylaws on plan de metas yet these are hardly mentioned in municipal or local media reports, suggesting little active follow-up and limited research opportunities.

Our sample of four cases was researched through various data sources (Yin, 2018). In the absence of academic literature, this mainly concerned secondary material such as government websites, NGO reports and blogs, academic theses, media items, YouTube recordings and evaluation studies. In addition, we conducted 16 semi-structured interviews (face to face and via videoconference, lasting 45 to 90 min) between 2014 and 2022 with at least two key informants per case from different stakeholders, such as government representatives and civil society activists. In the case of Colombia, we also interviewed researchers familiar with the national law. The topic guides for interviews and the functions of interviewees are listed in Supplementary materials. To avoid biases and the emergence of socially desirable answers, the semi-structured interviews with key informants did not probe for the presence of particular benefits. Instead, key informants were interviewed using open-ended questions (about positive and negative effects in the realm of elected politicians and decision-making, local government staff and organisational learning, and citizen trust and participation. To explore how positive and negative effects relate to design factors as well as the socio-political context of each city, we asked key informants about the suitability of mayoral performance mechanisms in different contexts and recommendations for change and improvement. In addition, we analysed the socio-political setup of each city (making use of certain proxy indicators such as country corruption ratings). For national comparisons in other world regions, one may use governance indicators (Glass and Newig, 2019) yet reliable micro-data are not available at the subnational level for Latin American countries with frequent political upheavals.

For each case, we set up a file containing secondary material and interview transcripts that were translated from the original Spanish and Portuguese into English. The resulting research material was coded and analysed in line with the research framework outlined above. The main characteristics covered were the mechanism’s impact on the electoral cycle (pre-election, planning and reporting) and three dimensions of accountability (information, discussions, consequences). Data and emerging patterns were discussed between the researchers to arrive at an indicative rating on the scale high/medium/low on each of the accountability cube’s three dimensions (information, discussions, and consequences) and to arrive at summary statements about each mechanism’s strengths and weaknesses. The mechanism’s potential effects were researched by listing all declared objectives as found in preambles to municipal by-laws or explicitly mentioned in blogs and policy papers written by advocates. Declared objectives almost exclusively had positive connotations (such as “better informed citizenry,” “more efficient public management”). Negative or “perverse” side-effects (e.g., rigidity, gaming, blame culture) were not mentioned but constitute a possibility according to ample scholarship on performance management. In line with the assessment framework (cf., Table 1), we clustered potential effects in terms of the three main uses and influences of performance information (instrumental, conceptual, and political/symbolic/discursive). Results and emerging patterns per case were subsequently compared and condensed to show commonalities and differences between the cities and to help formulate hypotheses for further research.

To provide essential context information, Table 3 presents a summary data of the four case studies. Bogotá, Córdoba, Guadalajara and São Paulo are metropolises with more than 1 million inhabitants, and democratically elected mayors (holding office for 3–4 years) and city councils. In terms of country rankings, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico occupy average places on the UN’s Human Development Index and Transparency International’s corruption index. According to World Bank assessments, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and to a lesser extent Argentina are relatively advanced in terms of results-based public management and monitoring and evaluation capacities (Feinstein and Moreno, 2015).

In this section, we present each case study city and summarise our findings in an overview (Table 4). For each case, we sketch the country context and how the accountability mechanism affects the electoral-administrative cycle (i.e., election, planning, reporting), followed by a concise description of how the mechanism has been implemented over time. We added an indicative rating of the mechanism in terms of the Accountability Cube’s three dimensions.

• Case 1: Bogotá (Colombia): Evolution of Programmatic Voting since 1994

Table 4. History and main features of performance accountability mechanisms in Bogotá, São Paulo, Córdoba and Guadalajara.

At a time when Colombia was internationally known for internal strife and crime, Colombia’s 1991 constitution ushered in greater levels of decentralisation, a revamped planning system, and various direct democracy mechanisms, including referenda. In 1994, the Programmatic Voting Law came into force, introducing performance accountability to the (sub-national) elections, government plans, and reports. In the election phase, the law requires all candidates for mayor (and governor) to submit their manifestos to a national registry. The National Planning Authority issued guidelines for candidates on how to elaborate such plans (including goals and indicators) but as yet there are no formal content requirements (Muñoz Ocampo and Álvarez Méndez, 2023). After an election, the elected mayor must elaborate a “development plan” aligning to the manifesto as well as multi-year (provincial, national) master plans and submit this within four months to the municipal council, which has the right to revise, request corrections, and approve the plan. A local and national planning council monitors coherence with existing (master) plans and subsequently of goal achievement (Romanutti, 2012a), for which the mayor must elaborate yearly progress reports. Amendments to the development plan are possible through the municipal council. Citizen oversight committees are legally mandated to exercise vigilance over all sorts of public management activities (Pogrebinschi, 2023). In recent decades, Bogotá’s various mayors have all complied with the Programmatic Voting laws planning and reporting requirements. Importantly, the law foresees the possibility of a recall referendum if, after 12 months of tenure, a mayor is accused of falling to achieve stated goals (Uribe Mendoza, 2016). Recalls are rarely successful (as they require support by 40% of voters) but are frequently attempted. Colombia’s capital is home to the highly influential, award-winning civil society initiative Bogotá Cómo Vamos (Scrivens and Iasiello, 2010). In addition to compiling and publishing data on sustainability indicators, it organises thematic discussions with mayoral candidates, issues multiple policy recommendations for the development plan, and runs the initiative “Council, How are we doing” that publicly monitors the voting behaviour (including task fulfilment) of municipal councillors. In terms of the three dimensions of accountability (Brandsma and Schillemans, 2012), the substantial amount of planning and reporting and close scrutiny by civil society and governmental bodies leads to Bogotá’s mechanism being rated as “much” for the information phase and “intensive” for the discussions phase. The constant threat of a recall or destitution, which came into play when Bogotá’s former mayor and later president was temporarily removed from power in 2014, warrants qualifying the sanctions phase as “many.”

• Case 2: São Paulo (Brazil): Evolution of Target Plan since 2008

After the end of the dictatorship and with the introduction of its 1988 constitution, Brazil became “the world’s largest laboratory of democratic innovations” (Pogrebinschi, 2021). Against the backdrop of widespread practices of clientelism and patrimonialism (Gaspardo and Ferreira, 2017), the country obtained an institutional architecture of citizen participation and deliberation and newly empowered municipalities developed instruments such as “participatory budgeting” that spread internationally (Porto de Oliveira, 2017). In São Paulo, a set of business and civil society leaders founded in 2007 the Nossa São Paulo network that, inspired by Bogotá Cómo Vamos, started to conduct educational campaigns, publish sustainability indicators, establish work groups about public policies, and monitor the city council actions. The running costs exceeded $1 million annually (Fiabane et al., 2014). Further, the network drafted and successfully lobbied for the “Target Plan” bylaw approved in 2008. This bylaw does not address the election phase, during which civil society organisations organise debates with candidates willing to participate, but obliges elected mayors to complete a governmental plan within 90 days of assuming power. Content-wise, the plan must contain the main goals presented in the mayor’s electoral campaign, be geared towards “the promotion of environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable development,” and have quantified “performance indicators”; process-wise, the bylaw stipulates: (i) wide dissemination in district-level public hearings; (ii) the possibility of amendments if changes are required; and (iii) semi-annual indicator reports plus yearly progress reports. Non-compliance with these formal rules is punishable by impeachment, yet there are no sanctions for non-achievement of targets. Since the bylaw came into force, all mayors have complied with formal requirements. The first administration (2009–2012) produced a plan with 223 targets, and the next one (2013–2016) built a dedicated website for a plan with 123 targets and links to the budget that was discussed in 35 public hearings, reaching cumulatively more than 10,000 participants (Baliña, 2017). The third administration (2017–2020) received more than 20,000 proposals during the public consultation phase of its plan (Cidade de Sao Paulo, 2022) yet it deactivated the previous website and faced several implementation difficulties due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Following São Paulo’s leadership, similar bylaws with minor adjustments were established in over 60 other Brazilian municipalities (Gaspardo and Ferreira, 2017). Attempts by supporters to turn the Target Plan into a national law were thus far unsuccessful (Programa Cidades Sustentáveis, 2020), just as lawsuits by opponents who had argued that Target Plans interfere with the executive’s constitutional independence (Villela and Souza, 2021). Compared to Bogotá, the “information phase” (Brandsma and Schillemans, 2012) of São Paulo’s accountability mechanisms is considered more limited (rating: medium) yet the “discussion phase” is considered equally intensive. The “consequences” are rated “few” as there are hardly any sanctions—neither legally nor politically—for non-compliance.

• Case 3: Córdoba (Argentina): Evolution of the Target Plan since 2011

In contrast to Brazil, Argentina transitioned to democracy in the 1980s without a substantial constitutional reform. The 1994 amendment increased some elements of citizen participation that have since evolved unevenly across the country, with two-thirds of participatory innovations observed in some large cities (Pogrebinschi, 2021). In Córdoba, Argentina’s second largest city, a coalition of universities, business leaders, media firms, and civil society representatives established the network Nuestra Córdoba (“Our Córdoba”) in 2009. Inspired by its namesake in São Paulo yet institutionally independent, Nuestra Córdoba begun collecting and publishing quality-of-life indicators, mobilising citizens, and lobbying for sustainable development policies. Furthermore, the network managed to gain approval in the municipal council of a Target Plan modelled after São Paulo’s. Córdoba’s 2011 bylaw, too, does not address the election phase, yet Argentina’s national laws mandate the diffusion and public debate of election manifestos (Cruz Pérez, 2024). In Córdoba, the elected mayor must elaborate and submit a Target Plan to the municipal council within 120 days. The municipal council, and not the mayor himself or herself, is also tasked with the plan’s diffusion. Contrary to São Paulo, the bylaw in Córdoba does not explicitly reference election promises or to the promotion of “sustainable development.” Instead, the target plan is required to cover main lines of action (short and long-term) for at least “public works and services, public administration, health, social action, environment, culture, education, tourism, neighbourhood participation and economic development,” in each domain with “quantified indicators.” The plan can be adjusted by informing the council and the public, and the mayor must submit yearly progress reports. A lack of goal achievement is not sanctioned. However, the lack of reporting constitutes a “serious irregularity”. Since the bylaw entered into force, all mayors formally complied with it. The first administration presented a plan with 513 targets (for 214 objectives in 16 thematic areas). According to civil-society observers, 42% of these targets could not be monitored due to the lack of suitable indicators and baseline values (Romanutti and Cáceres, 2020). The next administration produced a plan with 397 targets for 22 objectives and easier access to information thanks to the use of an open data platform. Public hearings were merely of an informational nature and had no deliberative character yet they still achieved higher levels of public interest than other hearings (Romanutti and Cáceres, 2020). The network Nuestra Córdoba computed overall goal achievement levels that were significantly lower than the percentage communicated by the mayor (Baliña, 2017). Following the lead of Córdoba, similar target law bylaws with minor adjustments were established in several other Argentine municipalities (Gaspardo and Ferreira, 2017). In terms of the “accountability cube” dimensions, Córdoba’s mechanism fares the same as São Paulo’s, with “few consequences” yet “medium-level information” and “intensive discussions” due to the continuous engagement by the civil society network that had conceived it.

• Case 4: Guadalajara (Mexico): Evolution of What Have You Done, Mayor since 2016

Although Mexico’s constitution had not undergone major changes since 1917, the country initiated decentralisation reforms in the 1980s and transitioned from a de facto one-party regime to multi-party democracy in 2000. In terms of national-subnational coordination, Mexico has a multi-layered system resembling that of Colombia, with local governments crafting “development programmes” that need to be aligned with higher-level, national plans. In recent decades, Mexico has also seen the emergence of numerous consultative bodies, giving it the most participatory institutions in the region (Pogrebinschi, 2021). Several citizen-run transparency initiatives concern the country’s deteriorating levels of organised crime and impunity. In Guadalajara—the country’s third-largest metropolitan area and capital of Jalisco state—a group of business leaders, nonprofit organizations, and universities took inspiration from the example of Bogotá Cómo Vamos and founded Jalisco Cómo Vamos in 2010. This organisation, primarily a citizen observatory, monitors and disseminates local indicators and public policy proposals through its website and media contacts. In 2015, Jalisco Cómo Vamos started the “What have you done, Mayor” programme as a voluntary arrangement: In the run-up to municipal elections, mayoral candidates were invited to debates, to make explicit manifestos, and to commit to participating in the programme if elected. Once elected, the mayor elaborated—in collaboration with a technical team from Jalisco Cómo Vamos—a plan with goals and indicators (currently in five domains “economy, education, environment, security, urban development, and public services”). During a mayor’s tenure, Jalisco Cómo Vamos tracks goal achievement and disseminates this once or twice per year via a dedicated website and public events. When first run in 2015, the mayors of two municipalities, including Guadalajara City, participated. In subsequent electoral cycles, four other municipalities from the metropolitan area joined. Compared to the other case studies, the “information” phase of this entirely voluntary accountability mechanism is rated as relatively “little” and the consequences as “few”. The discussion component is rated “medium” considering the active deliberations between the citizen observatory and mayors.

In response to the second research question, we present evidence of instrumental, conceptual, and political-discursive use and influence, along with an analysis of strengths and weaknesses of each accountability mechanism. Table 5 presents a comparative summary of the main findings for each case. For each illustrative quote, there is a code pointing to the key informant (cf., List of Interviewees).

• Case 1: Bogotá (Colombia): Effects of Programmatic Voting

Table 5. Summary of effects of mayoral performance accountability mechanisms in Bogotá, São Paulo, Córdoba and Guadalajara.

According to the law’s first article, programmatic voting is “the participation mechanism through which citizens […] impose as a mandate on the elected person in compliance” with their election promises. Key informants agreed that the law generally has the desired effect of contributing to transparency and to programmatic election debates and evidence-informed policies. These benefits are contingent on the law’s integration into a nationwide planning system that is equipped with better quality data (on social, environmental and economic indicators) than that of other Latin-American countries. Local stakeholders consider data availability as a key ingredient that allows the political discourse and monitoring of goal achievement to focus on sustainability outcomes (e.g., air quality) rather than about outputs (e.g., number of trees planted). In Bogotá, the active work of civil society organisations (such as Bogotá Cómo Vamos) in producing quality-of-life data, mobilising stakeholders and proposing public policies was credited as contributing to citizen participation and sustainability-oriented policymaking by successive city governments. Some informants were critical of the set-up: “Bogotá Cómo Vamos has lost some of its legitimacy. It is an oversight association of business origin, not a citizen initiative” (CO3). Furthermore, relative improvement over time can lead to a decrease in consensus. In the words of a senior municipal employee (CO3): “When in the 1990s Bogotá was in a serious crisis it was easy to agree about acute issues we had to resolve together. As we improve, there begins to be a divergence of opinion on the city’s priorities.”

The programmatic voting law’s harsh sanctions are also viewed as problematic. As the interviewee (CO3) commented:

Programmatic voting is theoretically nice but doesn’t work well in practice. That candidates have to guarantee something is good. If they are very committed to an issue, they make it explicit in the manifesto and later in the development plan. However, if they do not want to take risks, they set general goals that no one can charge them for.

To remedy this situation, there are calls for legal guidelines on the content of manifestos (Muñoz Ocampo and Álvarez Méndez, 2023). Other critical design factors concern the limited terms of office without re-election (“when the mayor arrives, the first six months are spent preparing the development plan”; CO4) and the fact that the burden of accountability is placed exclusively on mayors. As put by informant CO3:

People are politically uneducated and don’t realise that the mayor cannot govern without councillors. The citizens’ logic for electing councillors is one and for mayors another. In fact, the elections are on different days! In large cities, part of the council vote is a vote of opinion, but the bulk is a clientelist vote. […]. One would need a political reform guaranteeing that mayors will govern with a majority.

In this context, key informants interviewed saw the civil society project of monitoring the councillors’ work as a positive contribution yet also an expensive undertaking that relies on the continuous investment of resources by Bogotá Cómo Vamos.

• Case 2: São Paulo (Brazil): Effects of the Target Plan

São Paulo’s bylaw does not stipulate objectives, but a recent evaluation compiled by the municipality describes the Target Plan as a “big pact of transparency between the municipal administration and population” designed to “facilitate and foster social control” (Cidade de Sao Paulo, 2022). According to various municipal and civil society informants, the law contributed overall to more transparency and programmatic political debates (during elections) and goal-oriented policymaking during a mayor’s tenure. The bylaw also triggered significant citizen participation (as evident from public hearings and the initiative’s name recognition). Key informants stressed that both types of benefits would not have been achieved without the continuous investment of time and energy on behalf of civil society actors (belonging to the Nossa São Paulo network) who were also responsible for the bylaw’s initial formulation and spread to other cities. Cooperation in a network of cities lends some stability but did not prevent shocks when one administration (2017–2020) deactivated the municipality’s Target Plan dashboard. In the words of a local interviewee (BR1): “It was a big step back when they took down these websites. It was seen as an assault on this idea of the Target Programme and government accountability.” Later administrations rebuilt dashboards (and additional tools for geo-referenced monitoring), yet the incident showed the mechanism’s dependence on politicians’ willingness to engage.

In terms of conceptual effects, the network and its bylaw are also credited with fostering multi-stakeholder partnerships: In São Paulo, “one can observe religious community leaders discussing accountability and transparency, leftist militants discussing indicators and targets, and businessmen demanding opportunities for participation” (Fiabane et al., 2014, p. 834). Similarly, the municipal staff interviewed explained that the drafting of a plan—after the election—led to more intra-departmental coordination, policy coherence, and data literacy among government staff. Negative conceptual effects such as organisational competition or blaming were not observed. However, a study of decision-making practices in the municipality found evidence of three types of negative effects typically associated with performance management: “external gaming, myopia and lock-in” (Marin, 2016). In one instance, São Paulo’s mayor decided to stick to the target of constructing waste collection points (against better judgement available a year after planning) because he feared the political costs of amending the target. As commented by a municipal employee (BR1): “If you have to change your targets, then you are seen as someone who is not a good mayor.” According to some informants, the fact that most targets in the plans of successive administrations concerned tangible municipal outputs can also be interpreted as a negative byproduct of the entire accountability mechanism that puts the focus on short-term goal achievement (expressed in percentages) rather than city-level sustainability outcomes in the long term.

• Case 3: Córdoba (Argentina): Effects of Target Plan

The preamble to Córdoba’s bylaw refers to it as an “instrument of planning and citizen communication.” According to key informants, the implicit objectives of better-planned municipal actions and better-informed citizens are generally achieved. There is evidence of high levels of citizen engagement (also due to the communication work done by civil society working in a network with like-minded groups in other Argentine cities). In terms of instrumental and conceptual effects, municipal employees reported that Córdoba’s bylaw triggered better intra-departmental coordination and capacities:

We had to do trainings on methodological aspects because civil servants were not prepared to formulate indicators. At the beginning it was more of an obligation and now those responsible sit down and plan together. […]. There are many secretaries who really take it as a basis for measurement and update themselves annually, and check whether their goals are being met (AR3).

In Córdoba’s case, the choice of goals was initially the subject of many discussions. One debate concerned the scope of the municipality’s influence and accountability. In the words of another municipal employee (AR4):

We are very focused on product indicators and not outcomes […]. The dilemma comes as to how far you influence. For example, birth or death rates: You don’t know which part was affected by you and which part affected by the province or nation.

In addition, there have been repeated debates about who is mandated to formulate policies when the Target Plan is elaborated after an election. Some municipal administrations have publicly rejected proposals made by civil society actors. As one senior municipal official explained (AR5):

We did have some interference with Nuestra Córdoba where they confused that their goals should be ours. […] We strongly insisted that the social contract is the election manifesto, and from there, the goals must emerge.

At the same time, the official (AR5) acknowledged that “in the manifesto, the choices should be much more explicit. Because manifestos often describe abstract wishes.” Civil society representatives concurred by stating that both manifestos and plans often lack specificity (“They make Target Plans for compliance. Modest ones. And then in the course of their mandate they make strategic decisions,” AR1) yet that the entire accountability mechanism led, nonetheless, to a more programmatic electoral cycle:

These are informal social processes of control and the Target Plans have improved the pre-electoral process in the sense that not just anything is promised any longer. (AR1).

• Case 4: Guadalajara (Mexico): Effects of What Have You Done, Mayor

According to the project’s website, “This accountability and governance tool seeks to evaluate the achievement of government actions and to establish a communication channel between citizens and the government.” Increased uptake of the mechanism by candidates and elected mayors (of multiple municipalities), along with substantial citizen interest in the reports produced, are evidence of the mechanism’s having political and discursive effects. In this case, in particular, the investment and prior standing of the civil society organisation was a prerequisite for this achievement. As representative of Jalisco Cómo Vamos (MX1) explained:

What we were doing in terms of monitoring was already completely mediatized, so to speak. Among academics and authorities, we had a voice that mattered to the media.

The continued willingness by politicians to participate, however, cannot be taken for granted. Reportedly, local mayors stopped cooperating with another, similarly designed initiative in northern Mexico that was overtly critical:

They pressed too much. The thing is that if you press too hard it doesn’t work. It has worked better for us to sit at the table, teach them, and tell them why investing is important (MX1).

In terms of conceptual effects, the mechanism also benefited municipal capacities and attitudes. In the words of one key informant (MX1): “They still have to work a lot and find it very difficult to differentiate between impact and process indicators” yet “at least we see progress in that they have fewer and better indicators”; municipal staff “now give meaning to being accountable and see it as a need to respond.” According to politicians, collaboration with civil-society observatories has also led to better policies as an instrumental effect of this mechanism. A mayor commented publicly (Jalisco Cómo Vamos, 2022):

What you have done, Mayor, is a programme that challenges and confronts governments. But above all, it helps us be better, set better goals, and achieve better results. [...] One great idea of Jalisco Cómo Vamos was to conduct a survey to find out what [the children] think. […] Through this study, what we are doing is making all our policies cross-cutting and centred around girls and boys.

In terms of potentially negative effects at the discursive level, another informant (MX2) mentioned the risk of technical (sustainability) information having adverse effects on civic empowerment:

If we get too much into the technicalities and talk about ‘indicators’ suddenly it is more complex to reach citizens.

This paper set out to investigate the evolution of performance accountability mechanisms in Latin American cities, which have been under-researched yet offer valuable insights for academic debate about effective urban sustainability governance. In the four cities studied, the legal obligations for goal-setting and reporting were associated with an increase in programmatic policies, intra-municipal cooperation, civil society involvement, and citizen participation. An important contingency factor emerging from our research is that in all four case study cities, many benefits were dependent on the investment of civil-society networks (e.g., for data collection, reporting, websites, pro bono consultancies). Approving the legal framework alone may be merely symbolic: In one Brazilian city, the Target Plan bylaw reportedly fell into disuse when the civil society network that had promoted it ceased its operational activity. Overall, the institutional sustainability of the accountability mechanisms was found to be the lowest in Guadalajara and the highest in Bogotá. Our findings support the assertion that the thriving of citizen observatories requires the existence of favourable legislation as well as the presence of a civil society with a critical mass and stable resources (Díaz Jiménez and Natal, 2014). It is also in line with large-scale evaluations from the sub-continent. One recent study of 3,744 democratic innovations across Latin America found almost 500 targeting the evaluation of policies, which likely indicates dissatisfaction with democracy, feeding both civil society and government attempts to increase legitimacy (Pogrebinschi, 2023). However, many civil society monitoring initiatives are short-lived (Niemann and Hoppe, 2021).

Unintended, negative, or “perverse” effects of the accountability mechanisms were not observed on a large scale, but some were identified. One example concerned a municipality rigidly sticking to an outdated output target that was perceived as delivering on promises. This indicates a trade-off between accountability and flexibility, which is well-documented in the public management literature (e.g., De Bruijn, 2002). In light of this, the observation that Bogotá has relatively more outcome-based goals deserves further attention. After all, outcome indicators are essential for sustainability-oriented monitoring and policymaking (Hák et al., 2016) and less amenable to gaming; on the other hand, publicly reporting on shorter-term output data can improve government performance and citizen trust, which may be vital in underprivileged neighbourhoods and jurisdictions with lower levels of state capacities. This suggests further trade-offs concerning the relative benefits and constraints of outcome and output indicators in different policy sectors and local contexts.

This study enriches international debates (e.g., Valencia et al., 2019) about SDG localisation inasmuch as existing policy recommendations tend to be vague on the matter; one UN-affiliated guidance document (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2015, p. 19) states elusively that “as with SDG targets, it is generally preferable […] to track outcomes (or the ends) rather than means. Yet the choice between input and outcome measures must be handled pragmatically.” Too many practitioners are still unaware of the potential downsides (in terms of perverse effects) of performance management. For practitioners, an important recommendation is probing for trade-offs concerning accountability and flexibility and dilemmas in the choice of indicators; outcome-based targets foster long-term, holistic policymaking yet output targets align more easily to local government competencies and citizen demands.

Studying “frontrunners” is a well-established approach (Gerring, 2007) yet has limitations. In this study, selecting the case of Guadalajara implies a survivorship bias because other voluntary arrangements started in other Mexican cities may no longer exist. Furthermore, a city’s targets in terms of policy sector and type was also not assessed systematically in this study. Overall, formal characteristics were relatively easier to code than the effects of each accountability mechanism, which emerge over time and are subject to competing perspectives from different stakeholders (Bovens et al., 2008). We contend that our assessment framework provides a useful starting point for further conceptual work (on additional assessment criteria and context indicators) and more empirical studies.

More research is needed, notably on the relative advantages and disadvantages of directing (city-level, urban) performance accountability and communication towards outcomes or outputs in divergent political contexts. After all, it is known that “good measurement systems and well-functioning performance accountability systems only operate in stable environments with a great deal of standardisation” (Van de Walle and Cornelissen, 2014, p. 453), yet these are not typical characteristics of cities in Latin America (and elsewhere). Further, in terms of citizen communication, it has been argued that to instill trust in institutions, storytelling may be more effective than “scientific evidence” (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011). This too requires further research. We recommend studying a larger sample of cases/cities, with attention to government competencies and resources (cf., Fuhr et al., 2018), cities’ governance settings (Morita et al., 2020), and the role of indicators in different sectors (environment, health, education) since these bring different dynamics in terms of politics and lay understanding (Batley and Mcloughlin, 2015). To facilitate further research, Table 6 lists a set of hypotheses derived from this explorative study and the city from our sample that gave rise to the formulation of each hypothesis.

This study explored the characteristics and effects of novel performance accountability mechanisms that have evolved among pioneering local governments in Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico. In response to our first, descriptive research question on the mechanisms’ characteristics, we can conclude that the comparative analysis of Bogotá, São Paulo, Córdoba and Guadalajara showed three main types of legal approaches: a constitutional obligation in Colombia, city-level bylaws in Brazil and Argentina and, voluntary submission to external scrutiny by Mexican mayors. The mechanisms differ greatly in terms of scope. The Colombian system and Mexican project cover the entire electoral-administrative cycle, from election promises by candidates to a mayor’s reports on goal achievement. By contrast, the Brazilian and Argentine bylaws leave out the election phase. The latter approach pre-empts one difficulty inherent in the Colombian model: the mismatch between candidates making promises as individuals (or parties) and elected mayors needing to govern with competitive, multiparty councils. Another finding—which is not imposed by legal rules—is that many goals and the associated reporting system in Bogotá concern long-term sustainability outcomes (such as quality-of-life). In the other cities, relatively more goals and reports are about the delivery of tangible, short-term outputs such as public works.

Compared with the description of formal features, analysing the effects of an accountability mechanism is highly complex. As such, findings from this comparative case study do not provide comprehensive evidence that would allow us to answer our second, evaluative research question conclusively. However, several noteworthy patterns emerged. In all four cases, the mechanisms showed effectiveness in reaching the attention of citizens and politicians and informing specific (sustainability) policies. Furthermore, there are indications of the mechanisms contributing to transparency and a more programmatic, policy-oriented election cycle with a more participatory process of political deliberation. Positive effects were also reported—at least in the first years after the mechanism’s introduction—in the realm of data and indicator literacy, as well as in institutional cooperation among local governments and civil society actors.

What is the current verdict on the dichotomous question in this paper’s title: Should mayors be made accountable for their electoral promises? In answering this question, there appear to be trade-offs between accountability mechanisms bringing benefits in government performance and citizen participation, yet costs in terms of inflexibility and “perverse effects.” Forced to choose an answer, this research suggests a tentative “yes” for cities with low-performing municipal administrations—some degree of accountability is associated with more programmatic, less clientelist policymaking. In high-performing institutional contexts, rigid performance accountability seems less appropriate. In both types of context, effective sustainability governance requires (i) working towards long-term objectives and outcomes rather than short-term election promises and (ii) exploring alternatives to the currently dominant model of voluntary goal-setting.

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly. Anonymised data will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

LN: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. TH: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

The authors would like to thank the 16 key informants who volunteered their time to be interviewed for this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1450933/full#supplementary-material

Ammons, D. N., and Madej, P. M. (2017). Citizen-assisted performance measurement? Reassessing its viability and impact. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 48, 716–729. doi: 10.1177/0275074017713295

Aust, H. P., and du Plessis, A. (2018). Good urban governance as a global aspiration: on the potential and limits of SDG 11. In D. French and L. Kotzé (Red.), Sustainable development goals. Law, theory and implementation (pp. 201–221). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Baliña, L. M. (2017). Impactos institucionales, reformas organizacionales y nuevas prácticas a partir de la implementación de Programas y Planes de Metas en las ciudades de San Pablo y Córdoba entre 2008 y 2016 [Tesis de Maestría, Universidad Católica de Córdoba]. Available online at: http://pa.bibdigital.ucc.edu.ar/1543/ (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Batley, R., and Mcloughlin, C. (2015). The politics of public services: a service characteristics approach. World Dev. 74, 275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.018

Bell, S., and Morse, S. (2018). Sustainability indicators past and present: what next? Sustainability 10:1688. doi: 10.3390/su10051688

Bexell, M., and Jönsson, K. (2019). Country reporting on the sustainable development goals—the politics of performance review at the global-National Nexus. J. Hum. Dev. Cap. 20, 403–417. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2018.1544544

Biermann, F., Hickmann, T., Sénit, C.-A., Beisheim, M., Bernstein, S., Chasek, P., et al. (2022). Scientific evidence on the political impact of the sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 5, 795–800. doi: 10.1038/s41893-022-00909-5

Biermann, F., Kanie, N., and Kim, R. E. (2017). Global governance by goal-setting: the novel approach of the UN sustainable development goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 26-27, 26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.010

Bovens, M. (2005). Public accountability. In E. Ferlie, L. Lynn, and C. Pollitt (Red.), The Oxford handbook of public management (pp. 182–208). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bovens, M., Schillemans, T., and Hart, P. T. (2008). Does public accountability work? An assessment tool. Public Adm. 86, 225–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00716.x

Brandsma, G. J., and Schillemans, T. (2012). The accountability cube: measuring accountability. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 23, 953–975. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus034

Bravo, N. (2019). Voto Programático: La condición previa a las elecciones territoriales de 2020. In H. BaerVon and N. Bravo (Red.), Desarrollo territorial colaborativo: Descentralizando poder, competencias y recursos (pp. 741–764). Temuco: Ediciones Universidad de La Frontera.

Cáceres, P. (2014). Planes y Programas de Metas como innovaciones en los procesos de rendición de cuentas en el nivel local. Pensamiento Proprio 19, 191–226.

Cruz Pérez, I. E. (2024). Regulación legal sobre programas electorales en 18 países de América Latina. Apuntes Electorales 23, 107–138. doi: 10.53985/ae.v23i70.907

Dahler-Larsen, P. (2013). Constitutive effects of performance indicators: getting beyond unintended consequences. Public Manag. Rev. 16, 969–986. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2013.770058

De Bruijn, H. (2002). Performance measurement in the public sector: strategies to cope with the risks of performance measurement. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 15, 578–594. doi: 10.1108/09513550210448607

de Lancer Julnes, P., Broom, C., and Park, S. (2019). A suggested model for integrating community indicators with performance measurement. Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Community Well-Being 3, 85–106. doi: 10.1007/s42413-019-00046-6

Díaz Jiménez, O., and Natal, A. (2014). Observatorios ciudadanos: Nuevas formas de participación de la sociedad. Ciudad de México: Ediciones Gernika.

Feinstein, O. N., and Moreno, M. G. (2015). Monitoring and evaluation. In J. Kaufmann, M. Sanginés, and M. García Moreno (Red.), Building effective governments: Achievements and challenges for results-based public Administration in Latin America and the Caribbean (pp. 1224–1995). Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank

Ferreira da Cruz, N., Rode, P., and McQuarrie, M. (2019). New urban governance: A review of current themes and future priorities. J. Urban Aff. 41, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2018.1499416

Fiabane, D. F., Alves, M. A., and de Brelàz, G. (2014). Social accountability as an innovative frame in civic action: the case of Rede Nossa São Paulo. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 25:849. doi: 10.1007/s11266-013-9426-x

Fuhr, H., Hickmann, T., and Kern, K. (2018). The role of cities in multi-level climate governance: local climate policies and the 1.5 °C target. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 30, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.10.006

Gaspardo, M., and Ferreira, M. (2017). Inovação institucional e democracia participativa: Mapeamento legislativo da Emenda do Programa de Metas. Rev. Admin. Pública 51, 129–146. doi: 10.1590/0034-7612148181

Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giles-Corti, B., Vernez-Moudon, A., Reis, R., Turrell, G., Dannenberg, A. L., Badland, H., et al. (2016). City planning and population health: a global challenge. Lancet 388, 2912–2924. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30066-6

Glass, L.-M., and Newig, J. (2019). Governance for achieving the sustainable development goals: how important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions? Earth Syst. Gov. 2:100031. doi: 10.1016/j.esg.2019.100031

Greenwood, T. (2008). Bridging the divide between community indicators and government performance measurement. Natl. Civ. Rev. 97, 55–59. doi: 10.1002/ncr.207

Hák, T., Janoušková, S., and Moldan, B. (2016). Sustainable development goals: a need for relevant indicators. Ecol. Indic. 60, 565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.08.003

Hezri, A. A., and Dovers, S. R. (2006). Sustainability indicators, policy and governance: issues for ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 60, 86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.11.019

ISO. (2014). Sustainable development of communities—indicators for city services and quality of life (no. ISO 37120). Available online at: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:37120:ed-1:v1:en (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Jalisco Cómo Vamos. (2022). Presentación ¿Qué has hecho, Alcalde? Ciclo 2021 – 2024 [Video recording]. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9iC8tT2MMus (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Lehtonen, M., Sébastien, L., and Bauler, T. (2016). The multiple roles of sustainability indicators in informational governance: between intended use and unanticipated influence. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 18, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.05.009

Marin, P. D. L. (2016). Sistemas de gestão para resultados no setor público: Intersecções entre política, governança e desempenho nas prefeituras de Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo [Doctoral Thesis, Fundação Getulio Vargas]. Available online at: http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/dspace/handle/10438/15961 (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Meuleman, L., and Niestroy, I. (2015). Common but differentiated governance: a metagovernance approach to make the SDGs work. Sustain. For. 7, 12295–12321. doi: 10.3390/su70912295

Morita, K., Okitasari, M., and Masuda, H. (2020). Analysis of national and local governance systems to achieve the sustainable development goals: case studies of Japan and Indonesia. Sustain. Sci. 15, 179–202. doi: 10.1007/s11625-019-00739-z

Muñoz Ocampo, R. J., and Álvarez Méndez, J. F. (2023). Propuesta para modificar la Ley 131 de 1994, estableciendo un marco normativo a los programas de gobierno y su método de control [Master Thesis, Universidad EAFIT]. Available online at: http://repository.eafit.edu.co/handle/10784/32548 (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Niemann, L., and Hoppe, T. (2018). Sustainability reporting by local governments: a magic tool? Lessons on use and usefulness from European pioneers. Public Manag. Rev. 20, 201–223. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1293149

Niemann, L., and Hoppe, T. (2021). How to sustain sustainability monitoring in cities: lessons from 49 community Indicator initiatives across 10 Latin American countries. Sustain. For. 13:5133. doi: 10.3390/su13095133

Ortiz-Moya, F., and Reggiani, M. (2023). Contributions of the voluntary local review process to policy integration: evidence from frontrunner cities. NPJ Urban Sustain. 3, 1–8. doi: 10.1038/s42949-023-00101-4

Pogrebinschi, T. (2018). Deliberative democracy in Latin America. In A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. Warren (Red.), The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy (pp. 829–841). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Pogrebinschi, T. (2021). Thirty years of democratic innovations in Latin America. WZB Berlin Social Science Center. Available online at: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/235143 (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Pogrebinschi, T. (2023). Innovating democracy?: The means and ends of citizen participation in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pollitt, C. (2006). Performance information for democracy: The missing link? Evaluation 12, 38–55. doi: 10.1177/1356389006064191

Pollitt, C., and Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform: A comparative analysis. Third Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Porto de Oliveira, O. (2017). International policy diffusion and participatory budgeting. Cham: Springer International Publishing

Programa Cidades Sustentáveis. (2020). Guia para Elaboração do Plano de Metas. Available online at: https://www.cidadessustentaveis.org.br/arquivos/Publicacoes/Guia_para_Elaboracao_do_Plano_de_Metas.pdf (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Rey Salamanca, F. (2015). Voto programático y programas de gobierno en Colombia: Garantías para su cumplimiento (Primera edición). Bogotá, D.C: Editorial Universidad del Rosario.

Romanutti, V. (2012a). Instrumentos de rendición de cuentas y participación ciudadana. Aprendizajes en América Latina. Red Ciudadana Nuestra Córdoba. Available online at: http://www.nuestracordoba.org.ar/sites/default/files/Plan_Metas_Aprendizajes_en_America_Latina.pdf (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Romanutti, V. (2012b). Plan de Metas en Córdoba. Una experiencia de incidencia colectiva. Red Ciudadana Nuestra Córdoba.

Romanutti, V., and Cáceres, P. (2020). Innovación institucional y transformación democrática. Ocho años de implementación del plan de metas de gobierno en la ciudad de Córdoba. Admin. Pública Soc. 10, 252–264.

Scrivens, K., and Iasiello, B. (2010). Indicators of “societal progress”. Lessons from international experiences. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Sharifi, A. (2020). Urban sustainability assessment: an overview and bibliometric analysis. Ecol. Indic. 121:107102. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107102

Soto-González, E. (2020). Contribución de Jalisco Cómo Vamos a la gobernanza. Aporte público y lecciones aprendidas a partir del trabajo con el Gobierno de Jalisco 2013-2018. [Trabajo de maestria, Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente]. Available online at: http://rei.iteso.mx/handle/11117/6218 (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Sustainable Development Solutions Network. (2015). Indicators and a monitoring framework for the sustainable development goals. Launching a data revolution for the SDGs. Available online at: http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/150612-FINAL-SDSN-Indicator-Report1.pdf (Accessed May 30, 2024).

Tsoukas, H. (1997). The tyranny of light: the temptations and the paradoxes of the information society. Futures 29, 827–843. doi: 10.1016/S0016-3287(97)00035-9

Uribe Mendoza, C. (2016). La activación de la revocatoria de mandato en el ámbito municipal en Colombia. Lecciones del caso de Bogotá. Estudios Políticos 48, 179–200.

Valencia, S. C., Simon, D., Croese, S., Nordqvist, J., Oloko, M., Sharma, T., et al. (2019). Adapting the sustainable development goals and the new urban agenda to the city level: initial reflections from a comparative research project. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 11, 4–23. doi: 10.1080/19463138.2019.1573172

Van de Walle, S., and Cornelissen, F. (2014). Performance reporting. In M. Bovens, R. Goodin, and T. Schillemans (Red.), The Oxford handbook of public accountability (pp. 441–455). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Velte, P. (2022). Meta-analyses on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): A literature review. Manag. Rev. Q., 72, 627–675. doi: 10.1007/s11301-021-00211-2

Villela, M., and Souza, R. (2021). Programas de metas municipais sob olhar do Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo. Rev. Digit. Direito Adm. 8, 205–226. doi: 10.11606/issn.2319-0558.v8i1p205-226

Wray, L., Stevens, C., and Holden, M. (2017). The history, status and future of the community indicators movement. In M. Holden, R. Phillips, and C. Stevens (Red.), Community quality-of-life indicators: Best cases VII (pp. 1–16). Cham: Springer.

Wu, X., Fu, B., Wang, S., Song, S., Lusseau, D., Liu, Y., et al. (2023). Bleak prospects and targeted actions for achieving the sustainable development goals. Sci. Bull. 68, 2838–2848. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2023.09.010

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sixth Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Keywords: performance accountability, urban governance, sustainable development goals, sustainability reporting, Latin America, election promises, local government, democratic innovation

Citation: Niemann L and Hoppe T (2025) Should mayors be accountable for election promises? Effects of compulsory goal setting and reporting requirements on sustainability governance in four Latin American cities. Front. Sustain. Cities. 7:1450933. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1450933

Received: 18 June 2024; Accepted: 27 February 2025;

Published: 17 March 2025.

Edited by:

Tathagata Chatterji, Xavier University, IndiaReviewed by:

Richard Kotter, Northumbria University, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Niemann and Hoppe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ludger Niemann, bC5oLmgubmllbWFubkBoaHMubmw=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.