- 1Department of Built Environment, Central University of Technology, Bloemfontein, South Africa

- 2Department of Construction Management, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

As an alternative housing approach, self-help housing has been implemented for many years, particularly in developing nations. This study aimed to evaluate the potential of self-help housing as a mitigation strategy for reducing homelessness in South Africa. The focus was on the perception that housing is commonly regarded as a fundamental necessity the government provides, even though beneficiaries ultimately construct their own homes. A qualitative study was conducted using semi-structured interviews with 25 key informants involved in five projects located in the central region of South Africa. The objective was to assess the effectiveness of self-help housing in addressing homelessness, understand beneficiary perceptions, and identify the challenges associated with conventional and non-conventional housing delivery methods. The key findings revealed that while both methods present challenges, beneficiaries preferred self-help housing due to their involvement in the projects, the larger housing units they received, and their overall satisfaction with the outcomes. The study concluded that there is a need to reform self-help housing policies in South Africa to efficiently regulate and support incremental housing initiatives across the country.

1 Introduction

Housing is a basic human necessity and an indicator of a country’s standard of living and a crucial aspect of life, providing shelter, protection, warmth, and a place to sleep (Daly, 2013; Henilane, 2016). In developing countries like South Africa, the government must offer subsidized housing options, specifically public housing, to the marginalized segments of the population (Williams-Bruinders and de Wit, 2020). Public housing is a system that is usually owned by the government and is generally referred to as government-subsidized housing. In South Africa, public housing is provided through multiple programs governed by the National Housing Code of 2009, including the Integrated Residential Development Programme (IRDP), Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP), and Social Rental Housing Programme (SHRP) (Makhaye et al., 2021). This study specifically examined the Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP) for housing, currently referred to as the Breaking New Ground (BNG) housing policy, focusing on the UISP program within this policy.

Since 1994, South Africa has undertaken substantial initiatives to ensure housing for its population, including targeting the consequences of apartheid-induced segregation (Massey and Gunter, 2019). The South African government introduced a strategy that provides accessibility to housing based on income rather than race, employing a capital subsidy approach (Huchzermeyer and Karam, 2016). According to Ndinda et al. (2011), the housing subsidy plan had provided shelter to more than 2.8 million households by 2011. Nevertheless, ongoing obstacles need to be addressed, such as a convoluted and politically influenced procedure, hardships faced by individuals in the “gap market,” and the continued existence of informal settlements (Hoekstra and Marais, 2016). Housing distribution corruption continues to be a substantial problem, negatively impacting the living conditions of the intended recipients (Maluleke et al., 2019). Despite the increase in masonry structures, housing in South Africa continues to be segregated along racial lines, with the majority of informal residents being African and colored (Katumba et al., 2019). Provinces with well-defined plans for dealing with informal settlements have demonstrated greater effectiveness in decreasing their occurrence (Ndinda et al., 2011).

South Africa has enacted various housing laws and programs to tackle its substantial housing difficulties, explicitly targeting low-income communities (Mashwama et al., 2018). The primary objective of the 1994 Housing White Paper was to build residences for urban inhabitants who have faced historical disadvantages (Govender, 2011). Nevertheless, despite the endeavors, the issue of housing persists owing to corruption, substandard buildings, unsuitable locations, and insufficient engagement of stakeholders (Manomano et al., 2016). Integrated Development Planning has been essential for municipalities to improve service delivery. However, the current approach of providing low-income housing is only viable in the short term (Khan and Wallis, 2015). Curiously, certain townships that were established during the Apartheid era have thrived in comparison to projects initiated after the end of Apartheid. The residents of these settlements have utilized their dwellings as valuable resources to enhance their living conditions (Hunter and Posel, 2012). A partnership between the government and the private sector has improved the efficiency of programs. However, the development is impeded by intricate administrative systems and professionalization that restrict chances for low-income people (Fieuw and Mitlin, 2018). Civil society activities have gradually impacted policy, but significant changes remain.

The Breaking New Ground (BNG) program, implemented in 2004, sought to improve South Africa’s housing policy by prioritizing the creation of sustainable human settlements and integrated development (Venter and Marais, 2010a,b; Royston, 2009). BNG aimed to tackle spatial planning, encourage densification, and enhance urban development processes (Royston, 2009). Nevertheless, implementing policies has faced ongoing difficulties, primarily because of a need for more alignment between policy discussions and scholarly research (Venter and Marais, 2010a,b). The intricate nature of the policy has posed challenges in its interpretation, particularly at the municipal level (Swensen, 2020). Detractors contend that a technocratic approach has prioritized the interests of the elite, implying that adopting a political strategy that focuses on alleviating poverty could lead to more favorable outcomes (Pithouse, 2009).

Although BNG aims to include all members of society, participatory methods in housing building frequently marginalize impoverished individuals, particularly in rural regions (Myeni and Mvuyana, 2018). To tackle these problems, academics suggest enhancing community engagement and aiding local organizations to counter the influence of the privileged few and foster creative solutions (Puustinen et al., 2022; Ojo-Aromokudu and Loggia, 2017). Promoting sustainable human settlements through the BNG has faced difficulties due to reconciling policy with practical execution, especially at the municipal tier. This study aimed to assess the viability of self-help housing as a potential solution to alleviate homelessness in South Africa. The objective was to evaluate the efficacy of self-help housing, investigate beneficiaries’ attitudes, and analyze the problems encountered in conventional and non-conventional housing delivery methods. The study’s scope was confined to five self-help housing projects in South Africa’s central region, emphasizing insights from essential informants. The study concluded that while encountering challenges, self-help housing is preferred among beneficiaries because of its participatory characteristics and the provision of bigger-sized housing units. The results underscored the need for nationwide policy reform to enhance regulation and support for self-help housing projects.

1.1 Overview of homelessness in South Africa

According to Sinxadi and Campbell (2020), homelessness in South Africa primarily occurs when individuals aged 55 and over occupy land that is not zoned for residential purposes. Homelessness in South Africa is mainly caused by a severe housing shortage, high unemployment, and urbanization (Centre for Affordable Housing in Africa, 2017). In 2015, there were 200,000 homeless individuals on the streets alone, and tremendous inequality prevailed, with approximately 79% of the population living in poverty in South Africa (Statistics South Africa, 2018a,b). The impact of apartheid regulations on households resulted in the emergence of a previously disadvantaged population in South Africa, mostly of African heritage. Forced removals, uprooting, statutory landlessness, denial of paperwork, and other apartheid government procedures drove this group of people to homelessness at various points in time (Amore et al., 2011; Obioha, 2019). In South Africa, diverse types of migration have significantly influenced the rise of homelessness (Hermans et al, 2020). When family members leave their customary place of residence in a severe situation and relocate to another location, they risk becoming homeless, either temporarily or permanently. Internal movement, primarily from rural to urban areas, is the cause of a large portion of homelessness in South African cities, resulting in urban homelessness (Busch-Geertsema et al., 2016; Smith and Hall, 2018). Low wages have been a serious issue, even in areas where most South African workforce works, leading to family and household insolvency (Tenai and Mbewu, 2020). All the circumstances described above lead to unsustainable living conditions in which households cannot afford “decent” housing (Anita, 2023; Smets and van Lindert, 2016). Like many other countries on the continent and around the world, South Africa is grappling with the issue of social exclusion. This is a situation in which a society is not mutually and equally accommodating to all its members, regardless of their social classification (gender or race). Many South Africans are socially disadvantaged and cannot attain certain advantages (De Beer, 2015). The mentally impaired, for example, are largely excluded from public housing distributions, leaving them homeless indefinitely. Cultural rights to inherit houses and property in some societies restrict specific segments of society, primarily women, widows, and culturally designated “unfit” individuals such as adopted children. In this way, these social groupings are significantly more vulnerable to homelessness than the general population (Baptista and Marlier, 2019; Gouveia, 2020). As a result, this study aimed to suggest that self-help housing can be used as a solution for homelessness and restore the dignity of the homeless in society.

1.2 Conventional housing in South Africa

The fundamental mandate and responsibilities of the Department of Human Settlements (DHS) are derived from Section 26 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996, Section 3 of the Housing Act of 1997, approved policies, and Chapter 8 of the National Development Plan (NDP) (Mabai and Hove, 2020). This empowers the DHS to establish and support a long-lasting national housing construction procedure in collaboration with provinces and municipalities (Mpya, 2020). The 2019 General Household Survey (GHS) conducted by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) revealed that approximately 81.9% of households in South Africa resided in formal houses, while 12.7% lived in informal dwellings and 5.1% in traditional dwellings (Mbandlwa, 2021). The country’s entire housing backlog is a staggering 2.6 million units, underscoring the urgent need for action. In 2019, the United Nations Human Settlements Program (UNHCR) planned to deliver 470,000 dwelling units, 300,000 service sites, 30,000 social housing units and improve 1,500 informal settlements in South Africa (Mdluli and Dunga, 2022). However, it only generated 126 proposals for upgrading informal settlements (Thukwana, 2020).

South Africa’s housing policy has experienced substantial transformations, transitioning from small-scale initiatives to expansive “catalytic projects” and megaprojects (Ballard and Rubin, 2017; Ballard and Rubin, 2017). The objective of this policy change is to enhance the provision of housing and establish cohesive communities. Nevertheless, sceptics contend that it may worsen the problem of urban sprawl and be ineffective in attracting economic development (Ballard and Rubin, 2017). The previous housing subsidy program had a minimal effect on reducing poverty because it primarily focused on constructing houses through contractors. These dwellings were frequently low-quality and in unfavorable areas (Bradlow et al., 2011). The government’s strategy disregarded informal settlements and offered minimal assistance for gradual improvement or self-constructed residences (Turok, 2016). In addition, the issue of corruption in the allocation of houses has resulted in a substantial backlog despite the existence of constitutional and legislative measures (Mhlongo et al., 2022). The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) housing project in South Africa, which aims to tackle the housing shortage and provide shelter to underprivileged communities, encounters substantial obstacles (Leboto-Khetsi, 2022). Despite accommodating millions of people, the initiative has faced criticism for its substandard construction, insufficient services, and low quality (Moolla et al., 2011). Corruption, mismanagement, inadequate housing structures, substandard materials, and unfavorable sites are responsible for the ongoing housing difficulties (Beier, 2023). Urbanization worsens the housing issue and high unemployment rates, and individuals who get benefits choose to rent or sell their homes (Migozzi, 2020). As the government grapples with the efficient execution and administration of housing initiatives (Viljoen, 2024), recipients modify and convert their living areas to overcome constraints (Charlton, 2013). The intricate interplay between inhabitants and their RDP home exposes deficiencies and emotional connections, underscoring the necessity for a comprehensive housing strategy that not only addresses these issues but also prioritizes empowerment and revenue generation, offering a potential for positive change (Amoah et al., 2019; Charlton, 2013).

To tackle these problems, experts recommend promoting development that focuses on the needs of individuals, establishing a system where residents are actively involved, and enhancing the processes for applying and allocating resources (Bradlow et al., 2011; Khowa-Qhoai and Tyali, 2024). Consistent with these guidelines, Human Settlements instructed provincial governments to halt free housing programs promptly and instead implement serviced sites, allowing individuals to construct their own homes (Ntema, 2018). According to Statistics South Africa (2018a,b), in 2018, over 3.9 million (23.3%) South African households lived in RDP/government-subsidized housing, with the Free State, Northern Cape, and Western Cape having the highest number of such households. In the 2016 community survey, one of the questions for households living in RDP houses was to rate the quality of that dwelling (Amoah et al., 2022). The data showed that more than a fifth of households (22%) in the Free State RDP houses considered them poor. It was noted that only 46% of households in RDP/government-subsidized housing assessed them as being of good quality. Only two of the five districts in the Free State classified RDP dwellings as being of good quality based on differences in ratings at the district and municipal levels. The local municipalities of Tokologo and Mantsopa had the highest proportion of households, ranking their homes as poor quality (approximately 23%) (Statistics South Africa, 2018a,b). The primary obstacles faced by RDP buildings are as follows: The issues identified include the limited dimensions of the building, inadequate ventilation within the premises, enhancements made outside the official system due to the small scale, the challenge of affordability for individuals with moderate incomes, insufficient land availability for large-scale housing projects, the misuse of houses by recipients who rent them out, the prevalence of informal landlords who construct makeshift dwellings, and the presence of corruption and disorganization (Roux, 2020; Mbatha, 2019).

1.3 Background on self-help housing in South Africa

Self-help housing became widely used to tackle housing challenges in developing nations in the 1960s–1970s (Venter, 2017). Self-help housing refers to individuals or groups independently building or enhancing their housing, typically in small steps as their financial resources permit (Bredenoord and van Lindert, 2014). Although the approach is commended for its economical nature and ability to empower communities, sceptics raise concerns about whether it genuinely serves all impoverished urban residents and if its appeal is driven by the intention to rationalize decreased government assistance (Turok and Borel-Saladin, 2016). Self-help housing encompasses a range of initiatives, including informal community projects and social companies that offer skills training (Rhodes and Mullins, 2009). In Indonesia, low-income urban villages are frequently linked to legality issues and the possibility of being demolished (Reerink, 2011). Despite its limited size, self-help housing is considered a promising remedy for housing shortages, especially in the context of reduced governmental expenditure (Mullins, 2010). Nevertheless, achieving successful implementation necessitates the acquisition of properties, funds, volunteers, and residents (Rhodes and Mullins, 2009).

The benefits of self-help housing include:

• Community members gain skills through day-to-day building activities while assisting their neighbors in constructing their homes.

• Community members are empowered, and their self-satisfaction with what they have built is boosted.

• The community benefits because members are subcontractors who acquire supplies and insurance.

Gumbo and Onatu (2015) categorized self-help housing into three primary perspectives: supportive, structuralist, and market-oriented methods. Scientific research confirms that urban residents living in poverty can enhance the quality and size of their dwellings with the support and adaptability offered by relevant stakeholders (Bredenoord and Hurtado, 2022). Incremental housing development enables the urban underprivileged to autonomously determine when and how to extend their homes while giving them control over their finances and the choice of construction methods and materials (Arroyo, 2013). Consequently, compared to government-provided housing, people express higher satisfaction with their housing options (Van Noorloos et al., 2020; Klaufus, 2010). The structural viewpoint examines the dominance and exploitation of people with low incomes by political and economic elites, who aim to maintain their authority by exploiting people with low incomes through self-help housing schemes (Baquero, 2013).

Instead of seeking sustainable solutions to alleviate poverty and break the cycle of dependency, these initiatives are employed as a means of exerting control. From a market-oriented standpoint, the participation of the private sector in providing low-income housing complements the government’s efforts to deliver acceptable housing despite limited resources. Governments help reduce housing prices by facilitating access to land for self-construction by the less privileged and by enabling the private sector to offer additional services (Gumbo and Onatu, 2015). Governments allocate responsibilities to various stakeholders to enhance housing affordability for low-income individuals and prioritize providing sites and services, essential homes, low-cost financing, subsidies, and affordable building technologies (Dhlamini, 2018). However, it is worth mentioning that self-help housing projects, specifically through the Enhanced People’s Housing Program (EPHP), formerly known as the People’s Housing Process (PHP), are significant in the South African setting (Brown-Luthango, 2019). Typically, they adhere to structuralist principles. The EPHP program receives a government-funded subsidy that covers individuals involved in the higher-level organization but does not cover the expenses for internal engineering services at the local level. Additional sources of money are necessary to finance these services (Cirolia et al., 2016).

1.4 Significance of the research on social inclusion in cities

The reported study addresses social inclusion in cities by advocating for self-help housing as a participatory strategy that enables communities, particularly in resource-constrained areas, to meet their housing needs independently. This approach fosters a sense of ownership and fulfillment, critical components of social inclusion, by involving beneficiaries in constructing their own homes. The emphasis on traditional and unconventional housing approaches highlights the importance of policies catering to different communities’ diverse needs, ensuring that marginalized groups are not excluded. This aligns with the broader goal of developing urban infrastructures that are inclusive, resilient, and adaptable.

Furthermore, the study addresses critical issues such as homelessness, limited resources, access, equity, and fairness in pursuing sustainable housing. Its interdisciplinary approach, incorporating insights from innovative building technologies, social inclusivity, and resilience, offers valuable perspectives on how cities can evolve better to serve their inhabitants, particularly the most disadvantaged. The research contributes to the ongoing conversation about creating more sustainable and socially inclusive urban environments by advocating for policy reform and integrating self-help housing into broader urban planning initiatives.

2 Research method

This study employed a qualitative research method, concentrating on the perspectives and experiences of diverse stakeholders engaged in self-help housing projects. The method was designed to explore the effectiveness and challenges of self-help housing as a strategy to mitigate homelessness in the central region of South Africa.

2.1 Research design

A qualitative research design was selected to examine participants’ experiences and perspectives comprehensively. The research employed semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions as the primary data collection techniques. Semi-structured interviews facilitated adaptable responses while concentrating on essential research enquiries, while focus groups encouraged dynamic discussions among participants from diverse cultures.

2.2 Recruitment process

The study’s participants were recruited from professionals in the Housing Development Agency, provincial authorities in the Free State and Northern Cape, and department heads of human settlements in the respective provinces. Furthermore, participants from five self-help housing initiatives were solicited to engage in focus group discussions. The recruitment process employed a deliberate selection strategy, focussing on individuals involved in various housing delivery methods, including government-assisted housing recipients, unregulated self-help housing participants, and those engaged in self-help housing initiatives within larger housing projects.

2.3 Data collection

The primary data collection methods included five focus groups (10 participants in each group) and 25 semi-structured interviews. Focus group discussions were held across five locations: Ladybrand, Jacobsdal, Luckhoff, and Koffiefontein, each consisting of at most 10 participants. This limit was set to avoid overwhelming the discussions and prevent unnecessary idea repetition. Participants in the focus groups were selected from households based on their involvement in housing initiatives. The interviews with professionals and authorities in the housing sector provided diverse perspectives on self-help housing. These interviews were conducted based on data saturation, where no new themes or insights emerged from additional interviews, ensuring sufficient interviews were conducted to explore the research questions thoroughly. The projects examined in the study were delivered through various methods, including the site and services program, subsidization, and upgrade initiatives.

2.4 Ethical consideration

The study received ethical approval from the Nelson Mandela University ethics committee. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the interviews and focus group discussions. The research adhered to ethical guidelines to protect participants’ rights and confidentiality.

2.5 Data analysis

The data collected through the semi-structured interviews and focus groups were transcribed and evaluated by thematic analysis. This method facilitated the recognition of recurring themes and patterns among the various participant groups. The data were encoded and classified to emphasize critical findings concerning the obstacles, advantages, and views of self-help housing. This method guaranteed a thorough comprehension of the diverse elements affecting housing provision and recipient contentment.

3 Results

Researching the potential of self-help housing to lessen homelessness was the driving force for this project. The information presented here is derived from the focus groups discussions (FGDs) and semi-structured in person interviews detailed in section 3. Responses for the bar charts (Figures 1–3) are obtained from semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs). The study comprised 75 respondents, 25 participants from semi-structured interviews and 50 individuals from focus group talks. Focus groups were held at five sites containing 10 members, totaling 50 participants. The aggregate number of participants from the interviews and focus group sessions was 75.

3.1 Perceptions of self-help housing

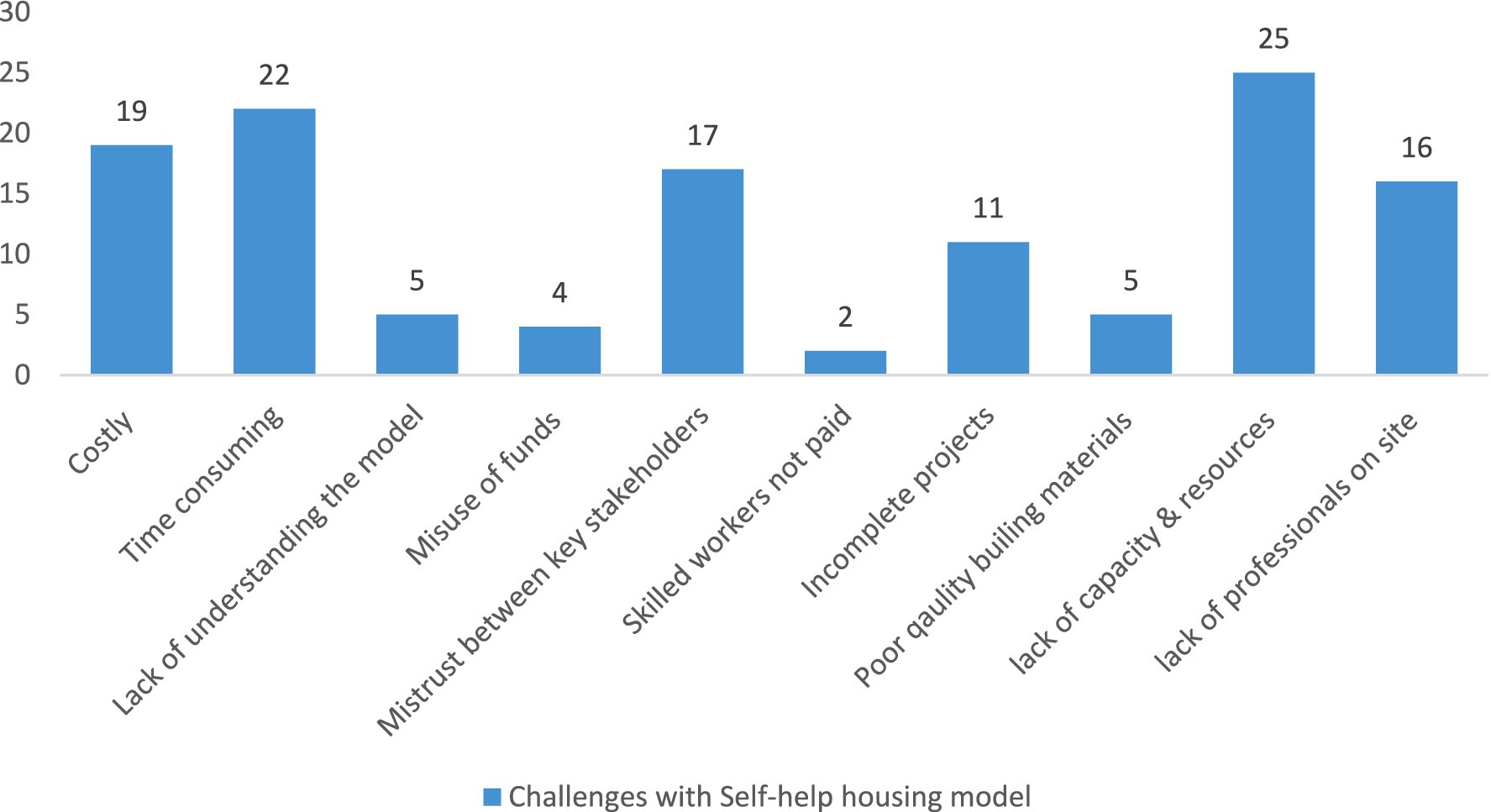

Figure 4 shows that the main problem with the self-help housing model, as stated by every interviewee, is that the government needs the means to carry out self-help housing initiatives, whether supported by community-led programs or the EPHP policy. Also, compared to housing projects driven by contractors, 22 out of 25 participants found that self-help housing takes more time. Respondent DO1 stated that:

“The Free State is faced with a high housing backlog. In 2020 we were still building 2010 housing units.”

The main reason is that training beneficiaries in basic construction skills for self-help housing projects takes much time, and beneficiaries generally need to gain construction skills. Some respondents mentioned that beneficiaries could be elderly or have various disabilities, which could cause project delays due to the difficulty in finding alternative builders to assist them.

Monitoring beneficiaries who provide physical workmanship during self-help housing projects by craftsmen and technologists is essential but time-consuming. Figure 1 displays the various types of self-help housing observed throughout the field survey.

Moreover, survey participants indicated that contractors driven by financial incentives typically demonstrate high levels of efficiency. However, in self-help housing initiatives, beneficiaries can express their preferences. Interviewees from the semi structured interviews stated:

“Government is reluctant to fund self-help projects. Perceptions of people need to change. The expectation that government has to give them a house needs to change. At least 20% of people living in informal settlement could build their own houses if they knew how to save. Beneficiaries of public housing lack education of other housing delivery strategies” (Respondent GM3).

Thirteen out of twenty-five participants concurred that self-help housing projects offer flexibility in house design, allowing recipients to customize their homes according to their tastes. The housing units have increased in size due to reductions in labor and material costs resulting from budget cuts. This is primarily due to using recycled building materials in most self-help housing projects. Figure 2 provides some examples of the advantages of self-help housing.

3.2 How the subsidized housing model is seen by beneficiaries

Most participants still need to receive contractor-driven, subsidized public and government housing. First, those who participated in the survey said the current method of adding names to a waiting list for recipients could have been more efficient. It takes people over a decade to get a house, and even then, once the housing projects are launched, they often need to get their dwellings on time. Therefore, the waiting list was considered to have no value and function. In addition, many felt too many political undertones to the housing waiting list. They referred to the idea that one needs connections to have their name taken into consideration when house allocations are made. A respondent from the FGDs stated:

“Government officials tend to push numbers instead of following the actual procedures as per the policy guidelines” (Respondent TP2).

Beneficiaries are compelled to utilize self-help housing due to this problem. As seen in Figure 3, participants have admitted to constructing makeshift homes in their backyards or shacks while saving for more permanent structures. The high unemployment rates, however, make it such that recipients need almost a year to purchase construction supplies. According to participants in Ladybrand, only young people get accommodation; the elderly, who have been on the waiting list for more than 7 years, do not acquire housing. While waiting for public housing, beneficiaries have said that the government does not assist them when building their homes. Because there is a long wait for BNG housing in Jacobsdal, beneficiaries have resorted to constructing and renting backyard shelters.

3.3 Community participation

Community participation is a crucial element in all housing delivery schemes (Aule et al, 2019). The study participants stated that there are various approaches by which the community participates in housing initiatives. Beneficiaries can contribute to a project by actively participating in physical labor, such as providing materials like bricks and mortar. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that their participation in decision-making processes may be optional or assured. Through collaborative activities with community organizations such as FEDUP, community members can contribute financially using savings programs based on group participation. These savings plans are financial vehicles in which participants contribute funds and save together to fulfil their mutual housing needs. Furthermore, community members might employ these savings to acquire building materials.

Inviting community people to all stakeholder meetings is crucial as it allows them to express their viewpoints on housing needs. Community involvement in improving informal settlements is supported by establishing community forums and gatherings and distributing announcements inviting community members to participate in housing project meetings. However, participants recognized that community gatherings follow a hierarchical framework in numerous projects, where local authorities only share information with project beneficiaries without considering their participation or contributions. In addition, the participants stated that community engagement should be regarded as using community liaison officers, who are specifically assigned to join project teams and advocate for the community’s interests. It is advisable to use social facilitation to encourage engagement with community members in the context of housing projects. The policies are too focused on the technical aspects, and they tend to neglect the social aspects. Respondent CE1 stated:

“In order to improve self-help housing policies, there needs to be more interaction with communities so that beneficiaries can fully understand the various housing programs, thus allowing them to make well-educated decisions based on their housing needs. We need to move away from dictating what beneficiaries need in terms of housing.”

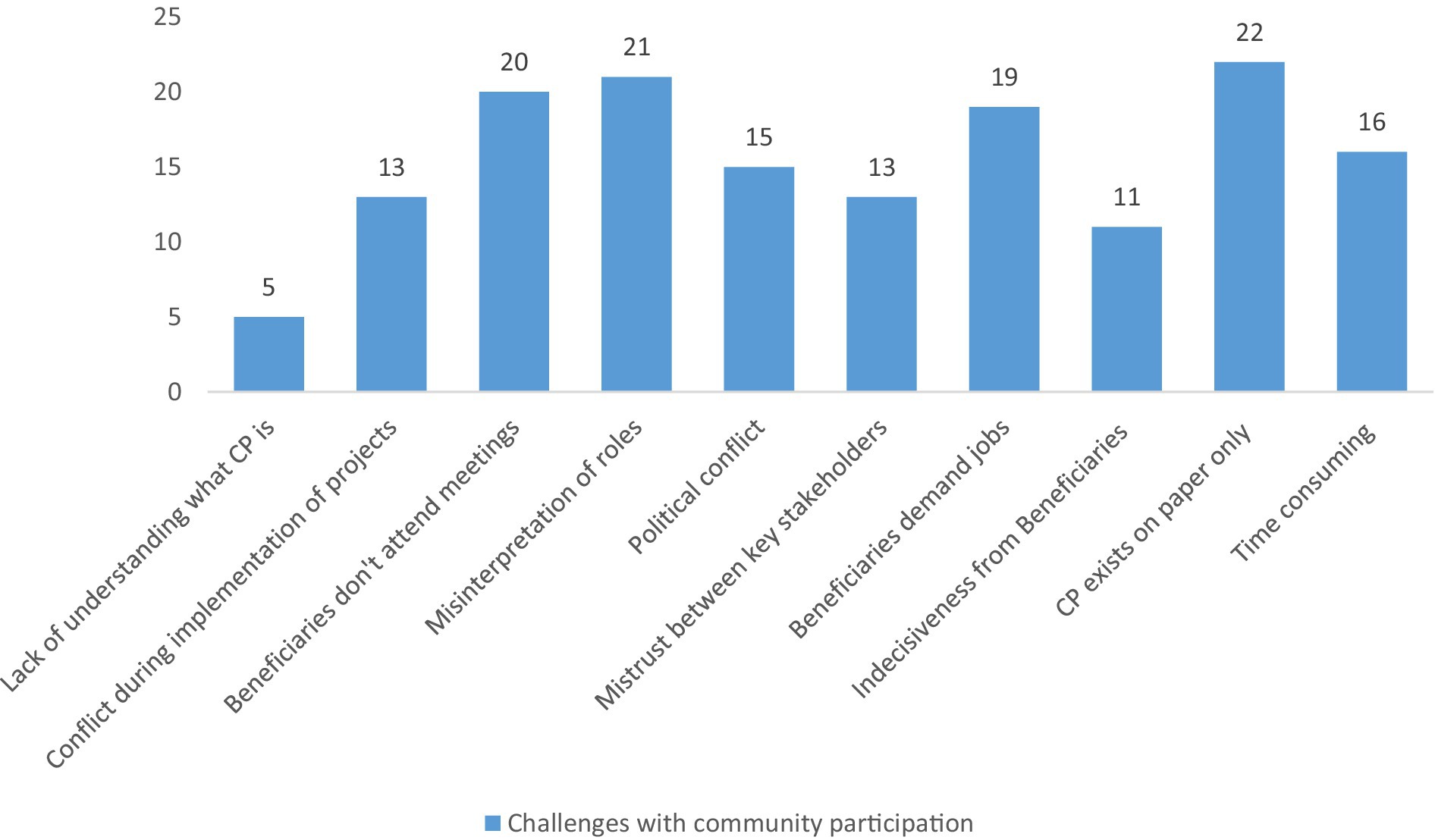

As depicted in Figure 3, the primary issue with community engagement is that it is merely theoretical and needs to be translated into actual practice. In addition, 21 respondents reported that beneficiaries need to learn about their expected role in community participation for housing projects, resulting in their frequent absence from community engagement sessions. Furthermore, based on the accounts of 15 interviewees, community involvement often results in discord among municipal authorities, councilors, and traditional authorities. Non-attendance of beneficiaries at community meetings results in project delays and increased conflicts, as these beneficiaries may protest if they are not consulted. Nineteen interviewers have identified another challenge: people requesting work from the local government despite needing more requisite skills.

Enhancing community engagement is the key to resolving these difficulties. As per the respondents, elected community leaders should encourage community involvement in initiatives by demonstrating transparency. However, the community should select these leaders rather than the municipality.

4 Discussion

This study’s findings offer significant insights into the challenges and benefits of self-help housing to alleviate homelessness in South Africa. Analysis of data obtained from semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions has revealed numerous critical themes that enhance our comprehension of how self-help housing functions within the larger framework of housing delivery in South Africa.

4.1 Challenges of self-help housing

Studies demonstrate that self-help housing has emerged as a crucial approach for delivering cheap housing in developing nations, yet its execution encounters obstacles (Bondinuba et al., 2020; Sithole, 2015). Since the 1970s, international organizations have advocated for self-help strategies (Bredenoord and van Lindert, 2014), although government participation in these initiatives needs to be more adequate and effective. Participants identified the absence of governmental backing for self-help housing programs as a significant issue. The respondents regularly indicated that the government cannot effectively execute these projects, whether community-driven or backed by initiatives like the Enhanced People’s Housing Process (EPHP). This conclusion corroborates previous research indicating that housing regulations in developing nations frequently encounter implementation difficulties, especially at the local level (Venter and Marais, 2010a,b; Swensen, 2020). The intricacy of these policies has led to delays and anomalies in housing provision.

In Indonesia, local government assistance to enhance the quality of self-help housing must be more effective (Vitriana, 2023). Traditional government housing initiatives must be more adequate in addressing the requirements of the urban impoverished (Tunas and Darmoyono, 2014). The findings indicate that self-help housing could address housing shortages. Still, its effectiveness relies on suitable government support and implementation techniques harmonizing governmental involvement with community engagement and private sector participation.

A notable issue that emerged was the time-consuming nature of self-help housing projects. Participants noted that training beneficiaries in basic construction skills slowed the process because many needed prior construction experience. Similar findings have been reported in other contexts, where a lack of technical skills among beneficiaries has been identified as a critical barrier to the success of self-help housing initiatives (Da Mata, 2023; Moore et al., 2013). Moreover, older people and individuals with disabilities were often unable to participate fully, further contributing to delays (Ward, 2022). This highlights the need for more inclusive strategies for vulnerable groups within self-help housing schemes.

4.2 Benefits of self-help housing

Despite the challenges, many respondents expressed a preference for self-help housing due to its empowering nature. Thirteen of the twenty-five interviewees valued the ability to customize their homes according to their preferences. This finding is in line with the research of Soto (2013) and Turner and Fichter (1972), who argue that self-help housing empowers individuals by giving them control over the design and construction of their homes. Additionally, the use of recycled building materials allowed beneficiaries to build larger homes at a reduced cost, which was seen as a significant advantage.

4.3 Perceptions of subsidized housing

In contrast, participants viewed contractor-driven, subsidized housing less favorably. The inefficiency of the waiting list system, political interference, and long delays in housing allocation were significant points of dissatisfaction (Tissington et al., 2013). This is consistent with global critiques of top-down housing delivery models, where bureaucratic inefficiencies and a lack of transparency often result in poor outcomes for beneficiaries (Pithouse, 2009; Kaiser, 2020). Participants in this study described how some had resorted to building informal backyard structures while waiting for formal housing, a phenomenon noted in other studies of housing insecurity in developing nations (Gilbert, 2014).

4.4 Community participation

Community participation emerged as a critical issue in housing delivery. While respondents acknowledged the potential of community involvement, they also pointed out several challenges, including the hierarchical nature of community meetings and the need for meaningful engagement with beneficiaries. This mirrors findings from previous research, which has shown that community participation is often superficial, with local authorities controlling decision-making processes without genuinely incorporating residents’ views (Puustinen et al., 2022; Venter and Marais, 2010a,b). Enhancing community engagement through social facilitation and empowering community liaison officers were suggested to address these issues.

The study’s findings reinforce the need for policy reforms to better support self-help housing initiatives in South Africa. While self-help housing offers significant flexibility and cost reduction benefits, the challenges related to skills training, government support, and inclusion of vulnerable groups must be addressed to enhance the effectiveness of these projects. Furthermore, improving community participation through more inclusive and transparent processes is essential for overcoming the current barriers to successful housing delivery. By addressing these issues, self-help housing can become a more viable solution for reducing homelessness and improving housing outcomes in South Africa.

4.5 Limitations

The study could not do prolonged follow-up with participants due to time constraints. Longitudinal studies may yield a more profound comprehension of the enduring outcomes and problems associated with self-help housing initiatives, especially regarding sustainability and community engagement. The research was carried out in the central region of South Africa, concentrating on five designated locations. Although this facilitated a comprehensive examination of local dynamics, the results may not apply to other places with varying socio-economic, political, and environmental conditions. Subsequent studies should encompass a more comprehensive geographical range to improve the representativeness of the results.

5 Concluding remarks

The results of this study suggest that while self-help housing presents several challenges, it offers a viable approach to alleviating homelessness, particularly as a temporary solution for individuals awaiting their subsidized housing units. Whether through backyard cottages, informal settlements, or formal dwellings, individuals who transition from homelessness to self-constructed housing, whether with or without government assistance, report a significant sense of pride and empowerment. The findings highlight the need to reevaluate and strengthen the Enhanced People’s Housing Process (EPHP) policy, which supports self-help housing initiatives, better align it with the realities on the ground. These initiatives can become more effective and sustainable by enhancing community engagement and equipping recipients with essential skills.

The study also reveals key constraints that hindered the investigation, including the need to access project sites on the periphery of Bloemfontein and the challenge of finding interpreters. The COVID-19 pandemic further complicated access to critical participants, particularly for focus group discussions, and it took much work to identify volunteers who had taken part in self-help housing due to a limited understanding of the concept. These obstacles point to a critical need to refine the implementation strategies for self-help housing in South Africa, enabling broader and more effective participation in incremental housing projects nationwide.

5.1 Implications for further study

This study opens several avenues for future research. Further studies could explore the long-term outcomes of self-help housing, mainly focusing on how recipients’ living conditions evolve and the sustainability of these housing solutions. Additionally, comparative studies across different regions of South Africa are needed to assess how contextual factors influence the success of self-help housing. Quantitative research could also complement the findings by providing statistical evidence on the effectiveness and scalability of these initiatives.

5.2 Theoretical and practical contributions

Theoretically, this study contributes to the growing body of literature on alternative housing solutions, particularly within the context of developing nations. It adds to the discourse on housing policy, community engagement, and the role of self-help housing in mitigating homelessness. Practically, the study offers critical insights for policymakers and housing practitioners, suggesting the need for a more inclusive, participatory approach to housing delivery. Enhancing community engagement and addressing the identified challenges, such as needing more construction skills among beneficiaries, could lead to more efficient, flexible, and sustainable housing models. Ultimately, the findings advocate revising self-help housing policies to foster greater community involvement and more tailored support for beneficiaries, particularly vulnerable groups.

By addressing these theoretical and practical aspects, the study contributes to the academic discourse on housing. It offers actionable recommendations for improving the effectiveness of self-help housing in South Africa.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The Nelson Mandela University ethics committee reviewed and approved the studies involving human participants. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

NQ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FE: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alowaimer, O. (2018). Causes, effects and issues of homeless people. J. Socialom. 7, 1–4. doi: 10.4172/2167-0358.1000223

Amoah, C., Kajimo-Shakantu, K., and Van Shalkwyk, T. (2019). The level of participation of the end-users in the construction of the RDP houses: the case study of Manguang municipality. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 22, 949–960. doi: 10.1080/15623599.2019.1672011

Amoah, C., Van Schalkwyk, T., and Kajimo-Shakantu, K. (2022). Quality management of RDP housing construction: myth or reality?. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, 20, 1101–1121. doi: 10.1108/JEDT-11-2020-0461

Amore, K., Baker, M., and Howden-Chapman, P. (2011). The ETHOS definition and classification of homelessness: an analysis. Eur. J. Homeless. 5:20.

Anita, V. (2023). Post-implementation review of low-income housing provision policy: a qualitative study with executives’ perspective. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 11, 131–149. doi: 10.14246/irspsd.11.4_131

Arroyo, I. (2013). Organised self-help housing as an enabling shelter and development strategy. Lessons from current practice, institutional approaches and projects in developing countries, [licentiate thesis, housing development and management] : Lund University.

Aule, T. T., Mahmud Bin, M., and Ayoosu, M. I. (2019). Outcomes of community participation in housing development Anan update review. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 6, 208–218. doi: 10.32628/ijsrset196642

Ballard, R., and Rubin, M. (2017). A'MarshallA ‘Marshall Plan'forPlan ‘for human settlements: how megaprojects became South Africa's housing policy. Transformation: critical perspectives on southern. Africa 95, 1–31. doi: 10.1353/trn.2017.0020

Baptista, I., and Marlier, E. (2019). Fighting homelessness and housing exclusion in Europe. A study of National Policies : European Social Policy Network (ESPN).

Baquero, I. A. (2013). Organised self-help housing as an enabling shelter and development strategy. Lessons from current practice, institutional approaches and projects in developing countries. Lund: Lund University.

Beier, R. (2023). Why low-income people leave state housing in South Africa: progress, failure or temporary setback? Environ. Urban. 35, 111–130. doi: 10.1177/09562478221146395

Bondinuba, F. K., Stephens, M., Jones, C., and Buckley, R. (2020). The motivations of microfinance institutions to enter the housing market in a developing country. Int. J. Hous. Policy 20, 534–554. doi: 10.1080/19491247.2020.1721411

Bradlow, B., Bolnick, J., and Shearing, C. (2011). Housing, institutions, money: the failures and promise of human settlements policy and practice in South Africa. Environ. Urban. 23, 267–275. doi: 10.1177/0956247810392272

Bredenoord, J., and Hurtado, L. M. S. (2022). Organized self-help housing in Pachacútec, Peru: training women's groups in earthquake resistant housing construction. World J. Eng. Technol. Res. 2, 018–030. doi: 10.53346/wjetr.2022.2.1.0037

Bredenoord, J., and van Lindert, P. (2014). “Backing the self-builders: assisted self-help housing as a sustainable housing provision strategy” in Affordable housing in the urban global south (Routledge), 55–72.

Brown-Luthango, M. (2019). 'Sticking to themselves': neighbourliness and safety in two self-help housing projects in Cape Town, South Africa. Transformation 99, 37–60. doi: 10.1353/trn.2019.0010

Busch-Geertsema, V., Culhane, D., and Fitzpatrick, S. (2016). Developing a global framework for conceptualising and measuring homelessness. Habitat Int. 55, 124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.03.004

Centre for Affordable Housing in Africa (2017). Housing finance in Africa: a review of some of Africa's housing finance markets. JohannesburgAfrica: Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa.

Charlton, S. (2013). State ambitions and peoples’ practices: an exploration of RDP housing in Johannesburg Doctoral dissertation: University of Sheffield.

Cirolia, L., Smit, W., and Duminy, J. (2016). “Grappling with housing issues at the city scale: mobilizing the right to the city in South Africa” in From local action to global networks: Housing the urban poor (Routledge), 159–174.

Da Mata, F. V. (2023). A comparative study of assisted self-help and informal self-built housing in Angola to further a discussion about improving government low-income housing programs Doctoral dissertation: Newcastle University.

De Beer, S. (2015). Ubuntu is homeless: an urban theological reflection. Verbum Ecclesia 36, 1–12. doi: 10.4102/ve.v36i2.1471

Dhlamini, S. S. (2018). A critical analysis of self-built housing as a model for peri-urban areas: The case of Mzinyathi, Kwa Zulu. Natal, Durban: University of Kwa Zulu NatalNatal (Master’s dissertation).

Fieuw, W., and Mitlin, D. (2018). What the experiences of South Africa’s mass housing programme teach us about the contribution of civil society to policy and programme reform. Environ. Urban., 30, 215–232. /doi:10.1177/09562478177357, doi: 10.1177/0956247817735768

Gilbert, A. G. (2014). Free housing for the poor: an effective way to address poverty? Habitat Int. 41, 253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.08.009

Gouveia, S. (2020). An analysis of the efficiency of solutions to urban homelessness in South Africa, Economics Honours research paper. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

Govender, G. B. (2011). An evaluation of housing strategy in South Africa for the creation of sustainable human settlements: a case study of the eThekwini region (doctoral dissertation).

Gumbo, T., and Onatu, G. (2015). Interrogating South Africa’s People’s housing process: towards comprehensive collaborative and empowering aided self-help housing approaches. Johannesburg: APNHR.

Henilane, I. (2016). Housing concept and analysis of housing classification. Balti. J. Real Estate Econ. Constr. Manag. 4, 168–179. doi: 10.1515/bjreecm-2016-0013

Hermans, K., Dyb, E., Knutagard, M., Novak-Zezula, S., and Trummer, U. (2020). Migration and homelessness: measuring the intersections. Eur. J. Homeless. 14, 13–34.

Hoekstra, J., and Marais, L. (2016). “Can Western European home ownership products bridge the South African housing gap?” in Urban forum (Netherlands: Springer), 487–502.

Huchzermeyer, M., and Karam, A. (2016). “South African housing policy over two decades: 1994–2014” in Domains of freedom: justice, citizenship and social change in South Africa, 85–104.

Hunter, M., and Posel, D. (2012). Here to work: the socioeconomic characteristics of informal dwellers in post-apartheid South Africa. Environ. Urban. 24, 285–304. doi: 10.1177/0956247811433537

Jenkins, P., Smith, H., and Wang, Y. P. (2006). Planning and housing in the rapidly urbanising world : Routledge.

Kaiser, M. S. (2020). Are bottom-up approaches in development more effective than top-down approaches? J. Asian Soc. Sci. Res. 2, 91–109. doi: 10.15575/jassr.v2i1.20

Katumba, S., Fabris-Rotelli, I., Stein, A., and Coetzee, S. (2019). A spatial analytical approach towards understanding racial residential segregation in Gauteng province (South Africa). Abstr. ICA 1, 1–3. doi: 10.5194/ica-abs-1-164-2019

Khan, S., and Wallis, M. (2015). Planning and sustainable development of low-income human settlements in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 50, 43–58. doi: 10.1080/09709274.2015.11906858

Khowa-Qhoai, T., and Tyali, N. (2024). Breaking new ground: perceptions of RDP house beneficiaries of the Mavuso settlement in Alice, South Africa. Afr. Publ. Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev. 12:8. doi: 10.4102/apsdpr.v12i1.790

Klaufus, C. (2010). The two ABCs of aided self-help housing in Ecuador. Habitat Int. 34, 351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.11.014

Leboto-Khetsi, L. (2022). Exploring opportunities for sustainable local economic development in South Africa through collaborative housing revitalisation. Doctoral dissertation: University of the Free State.

Mabai, Z., and Hove, G. (2020). Factors affecting organisational performance: a case of a human settlement department in South Africa. Open J. Bus. Manag. 8, 2671–2686. doi: 10.4236/ojbm.2020.86165

Makhaye, L., Gumbo, T., Makoni, E., and Pillay, N. (2021). Exploring the approaches and strategies of upgrading informal settlements: learning from policy and practice in the city of Ekurhuleni, Gauteng province. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 2021 (pp. 5770–5782), IEOM Society.

Maluleke, W., Dlamini, S., and Rakololo, W. M. (2019). Betrayal of a post-colonial ideal: the effect of corruption on the provision of low-income houses in South Africa. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 11, 139–176.

Manomano, T. (2022). Inadequate housing and homelessness, with specific reference to South Africa and Australia. Afr. J. Dev. Stud. 13, 93–110. doi: 10.31920/2634-3649/2022/v12n4a5

Manomano, T., Tanga, P. T., and Tanyi, P. (2016). Housing problems and programs in South Africa: a literature review. J. Sociol. Soc. Anthropol. 7, 111–117. doi: 10.1080/09766634.2016.11885707

Mashwama, N., and Thwala, D. T. and Aigbavboa, C. A. (2018). Challenges of reconstruction and development program (RDP) houses in South Africa. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, pp. 1695–1702.

Massey, R., and Gunter, A. (2019). “Housing and shelter in South Africa” in The geography of South Africa: contemporary changes and new directions, 179–185.

Mbandlwa, Z. (2021). Challenges of the low-cost houses in South Africa. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 8, 135–6766. doi: 10.31000/jgcs.v8i1.10976

Mbatha, S. (2019). The acceptability of RDP houses to recipients in the Langa District, cape metropole Doctoral dissertation: Cape Peninsula University of Technology.

Mdluli, P., and Dunga, S. (2022). Determinants of poverty in South Africa using the 2018 general household survey data. J. Poverty 26, 197–213. doi: 10.1080/10875549.2021.1910100

Mhlongo, N. Z. D., Gumbo, T., and Musonda, I. (2022). “Inefficiencies in the delivery of low-income housing in South Africa: is governance the missing link? A review of literature” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (IOP Publishing), 052004.

Migozzi, J. (2020). Selecting spaces, classifying people: the financialization of housing in the South African city. Hous. Policy Debate 30, 640–660. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2019.1684335

Moolla, R., Kotze, N., and Block, L. (2011). Housing satisfaction and quality of life in RDP houses in Braamfischerville, Soweto: a south African case study. Urbaniizziv 22, 138–143. doi: 10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2011-22-01-005

Moore, T., and Mullins, D. (2013). Scaling-up or going viral? Comparing self-help housing and community land trust facilitation. Volun. Sec. Rev. 4, 333–353. doi: 10.1332/204080513X671931

Mpya, M. I. (2020). The implementation of the National Development Plan and its impact on the provision of sustainable human settlements: The case of Gauteng province (doctoral dissertation, master’s dissertation). South Africa: University of South Africa.

Mullins, D. (2010). Housing Associations, Third Sector Research Centre. working paper 16. Available at: https://rsr.tenantservicesauthority.org/

Myeni, S. L., and Mvuyana, B. Y. (2018). Participatory processes in planning for self-help housing provision in South Africa: policies and challenges. Int. J. Public Policy Admin. Res. 5, 24–36. doi: 10.18488/journal.74.2018.51.24.36

Ndinda, C., Uzodike, N. O., and Winaar, L. (2011). From informal settlements to brick structures: housing trends in post-apartheid South Africa. J. Public Adm. 46, 761–784. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-68127-2_306-1

Ntema, L. J. (2018). Self-help housing in South Africa: Paradigms, policy and practice Doctoral dissertation: University of the Free State.

Obioha, E. E. (2019). Addressing homelessness through public works programmes in South Africa. South Afr. Walt. Sisulu Univ. 3, 113–136. doi: 10.46404/panjogov.v3i2.3942

Ojo-Aromokudu, J. T., and Loggia, C. (2017). Self-help consolidation challenges in low-income housing in South Africa. J. Constr. Proj. Manag. Innov. 7, 1954–1967.

Pithouse, R. (2009). A progressive policy without progressive politics: lessons from the failure to implement 'Breaking new Ground'. Town Reg. Plann. 2009, 1–14.

Puustinen, T., Krigsholm, P., and Falkenbach, H. (2022). Land policy conflict profiles for different densification types: a literature-based approach. Land Use Policy 123:106405. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106405

Rhodes, M. L., and Mullins, D. (2009). Market concepts, coordination mechanisms and new actors in social housing. Eur. J. Hous. Policy 9, 107–119. doi: 10.1080/14616710902920199

Royston, L. (2009). A significantly increased role in the housing process: the municipal housing planning implications of BNG. Town Reg. Plan. 2009, 63–73.

Sinxadi, L., and Campbell, M. (2020). “Homelessness by choice and by force” in No poverty: encyclopedia of the UN sustainable development goals. eds. F. W. Leal, A. Azul, L. Brandli, S. A. Lange, P. Özuyar, and T. Wall (Cham: Springer).

Sithole, S.N., (2015). An evaluation of the effectiveness of mutual self-help housing delivery model: case study of habitat for humanity, Piesang River and Sherwood housing projects in Ethekwini municipality, Durban (doctoral dissertation).

Smets, P., and van Lindert, P. (2016). Sustainable housing and the urban poor. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 8, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/19463138.2016.1168825

Smith, R., and Hall, T. (2018). Everyday territories: homelessness, outreach work and city space. Br. J. Sociol. 69, 372–390. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12280

Soto, H. (2013). The mystery of capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the west and fails everywhere else. New York: Basic Books.

Statistics South Africa (2018a). Statistics South Africa- Census. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za

Swensen, G. (2020). Tensions between urban heritage policy and compact city planning–a practice review. Plann. Pract. Res. 35, 555–574. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1804182

Tenai, N. K., and Mbewu, G. N. (2020). Street homelessness in South Africa: a perspective from the Methodist Church of Southern Africa. HTS Teol. Stud. 76. doi: 10.4102/hts.v76i1.5591

Thukwana, N. (2020). Government is ending free housing projects – here is what it will offer instead. Business Insider SA, 3 December:1.

Tissington, K., Munshi, N., Mirugi-Mukundi, G., and Durojaye, E. (2013). Jumping the Queue', waiting lists and other myths: perceptions and practice around housing demand and allocation in South Africa.

Tunas, D., and Darmoyono, L. T. (2014). “Self-help housing in Indonesia” in Affordable housing in the urban global south (Routledge), 166–180.

Turner, J. F., and Fichter, R. (1972). Freedom to build: Dweller control of the housing process. Macmillan.

Turok, I. (2016). South Africa's new urban agenda: transformation or compensation? Local Econ. 31, 9–27. doi: 10.1177/0269094215614259

Turok, I., and Borel-Saladin, J. (2016). Backyard shacks, informality and the urban housing crisis in South Africa: stopgap or prototype solution? Hous. Stud. 31, 384–409. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2015.1091921

Van Noorloos, F., Cirolia, L. R., Friendly, A., Jukur, S., Schramm, S., Steel, G., et al. (2020). Incremental housing as a node for intersecting flows of city-making: rethinking the housing shortage in the global south. Environ. Urban. 32, 37–54. doi: 10.1177/0956247819887679

Venter, A. (2017). Self-help housing and informal settlements: regenerative futures in the Free State Province. Free State Research Colloquium. 18–20 October. Free State Province Treasury: Bloemfontein.

Venter, A., and Marais, L. (2010a). The neo-liberal facade: re-interpreting the south African housing policy from a welfare state perspective. Urban dynamics and housing change–crossing into the 2nd decade of the 3rd Millenium : ENHR, 4–7.

Venter, A., and Marais, L. (2010b). Housing policy in post-apartheid South Africa: a critique of breaking new ground. J. Housing Built Environ. 25, 431–447.

Viljoen, S. M. (2024). Public property in South Africa: a human rights perspective. Afr. Hum. Rights Law J. 24, 77–100. doi: 10.17159/1996-2096/2024/v24n1a4

Vitriana, A. (2023). Post-implementation Review of Low-income Housing Provision Policy: A Qualitative Study with Executives’ Perspective Case study: West Java Metropolitan Areas, Indonesia. Internat. Rev. Spatial Plann. Sustain. Develop. 11, 131–149.

Ward, M., (2022). Self-help housing as an effective delivery mechanism to reduce the backlog: research into self-help housing on state subsidised sites and services projects.

Keywords: beneficiaries, homelessness, public housing, self-help housing, sustainable human settlement

Citation: Qumbisa N, Emuze F and Smallwood J (2025) From perceptions by beneficiaries, can homelessness be reduced through self-help housing in the central region of South Africa? Front. Sustain. Cities. 6:1468668. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1468668

Edited by:

Prudence Khumalo, University of South Africa, South AfricaReviewed by:

Maria Tsvere, Chinhoyi University of Technology, ZimbabweEghosa Noel Ekhaese, Covenant University, Nigeria

Copyright © 2025 Qumbisa, Emuze and Smallwood. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nolwazi Qumbisa, bnF1bWJpc2FAY3V0LmFjLnph

Nolwazi Qumbisa

Nolwazi Qumbisa Fidelis Emuze

Fidelis Emuze John Smallwood

John Smallwood