- UCD School of Philosophy, College of Social Sciences and Law, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

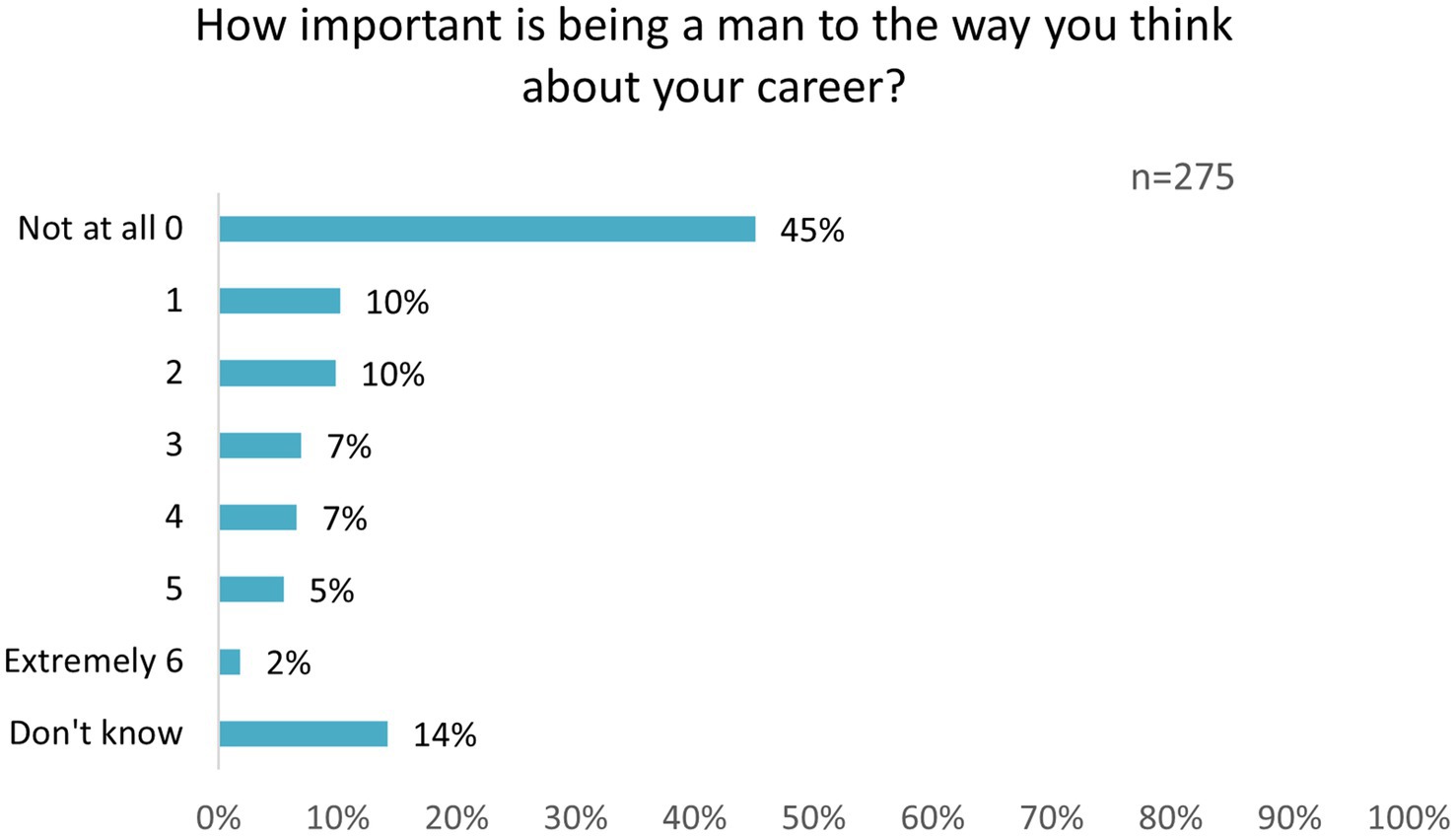

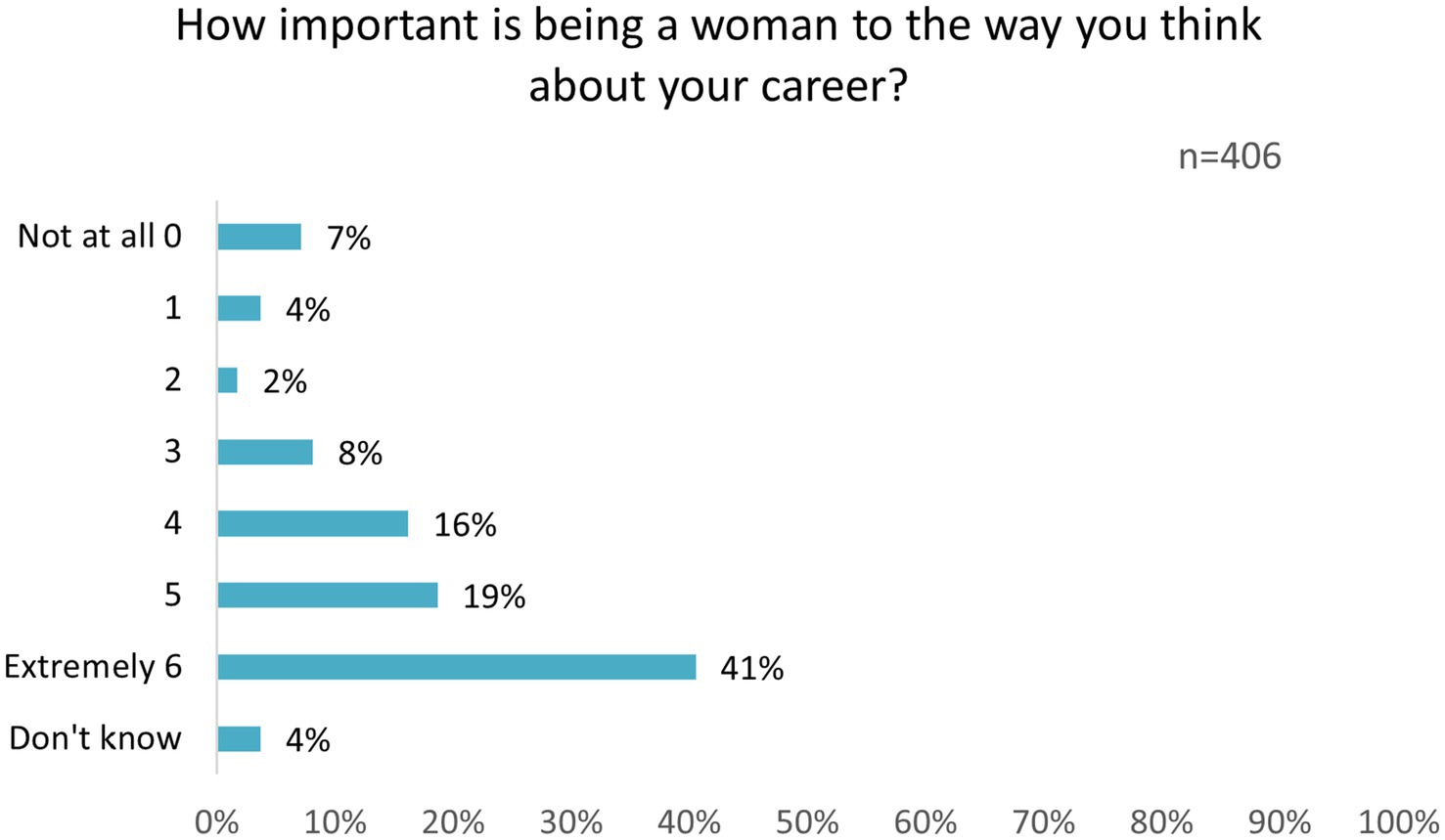

For women architects, the confluence of gender and professional identity has remained unresolved since their admittance to the profession of architecture. The past decade has seen a resurgence in the use of the term ‘women in architecture’ coupled with renewed debate around its use as well as challenges from feminist historians and theorists to recognise other forms of architectural practices and identities. The research presented here examines the interplay between gender and the professional identity of those working within, and outside of, architectural professional practice in Ireland by combining questions on gender and professional identity from a large survey (n = 684) and 23 semi-structured interviews. Launched in March 2023, the Irish Architecture Career Tracker Survey received over 680 completed online questionnaires. The respondents, ranging in age from 20 to 72, were asked, ‘How important is being a woman/man to the way you think about your career?’ Perhaps unsurprisingly, the results for men and women are almost the inverse of one another. Male respondents tended towards ‘being a man is not at all important to the way I think about my career,’ at 45%, whilst female respondents tended towards the opposite, ‘being a woman is extremely important to the way I think about my career,’ at 41%. Another key question asked was whether or not ‘The term ‘woman in architecture’ is an important reflection of who I am professionally?’ Just 40% of female participants agreed with this statement. In the 23 semi-structured interviews which followed the survey, these two topics were explored, providing rich qualitative. Interviewees were both male and female and ranged in age from 32 to 62. When analysed using a reflexive thematic approach, we identified six themes which, when taken together, show a difficult and at times contradictory and paradoxical confluence of gender and professional identity, especially, but not only, for female architects. We suggest that these apparent contradictions and paradoxes are a way to cope with the quintessential sexist dilemma that identifying as a ‘woman in architecture’ continues to present.

1 Introduction

Within the discipline of architecture, the terms ‘woman in architecture,’ ‘female architect,’ and ‘woman architect,’ remain controversial.1 Some embrace these labels, some reject them entirely, and others still, as will be shown in this research, switch between ‘architect’ and ‘woman in architecture’ depending on the context. Some of the (few) high-profile female architects have sought to reject the ‘woman in architecture’ and/or ‘female architect’ designation. In 2017, for example, Danish architect Dorte Mandrup declared, ‘I am not a female architect. I am an architect,’ sparking international debate (Mandrup, 2017; Marsh, 2017; Pérez-Moreno, 2018). Mandrup’s rejection of the label was coupled with a desire to be considered on merit and not as ‘second-class citizens.’ This is nothing new. The desire to be considered based on ability rather than through the prism of gender has been around since women were first admitted into the profession.2 Writing as, she termed it, a ‘dissenting essay’ in the 1989 volume celebrating 100 years of women in the American Institute of Architects, architect Chloethiel Woodard Smith said that “to accept the label ‘woman architect’” is to accept the idea of a handicap, ‘for its implication that women have some physical or mental impediment that they have remarkably overcome in managing to practice architecture’ (Woodard Smith, 1989, p. 222). Woodard Smith is correct to assert that there is nothing essential in being female that might impede women from being architects. Yet she does not dwell in the fact that there are social forces which regard women as less capable of designing homes, work, and public spaces than cleaning them. This social experience of sexism is a handicap that women must overcome. This sexism must be rebutted, and Woodward Smith’s approach is to insist that there is no difference between male and female architects—they are all merely architects. Yet this approach does not regard the way in which architecture—as practice and profession—has been and is dominated by men, their views, values, and concerns. Must women assimilate?

In 2012, architectural historian and theorist Karen Burns invited researchers to take a different approach:

The apparent ‘refusal’ of women interviewees to self-identify as women architects or explain career trajectories primarily through the prism of gender invites us to produce more subtle theories of identity, lived subjectivity and mechanisms of gender identification in feminist architectural research. The term, woman architect, invites us to think about the hyphenated nature of identity (Burns, 2012).

Burns wants us to join in the project of demonstrating that there are insights to be gained from those whose lived experiences of the world do not come from the unmarked norm of being affluent, male, able-bodied, and white. However, Burns wants us to develop this argument that ‘hyphenated’ or intersectional identities might generate richer theories of architectural identities without first paying attention to the sexism pointed to in Woodward Smith’s assertion that we all know that it is commonly assumed that being a woman is a ‘handicap’ to being an architect. In rushing to make the argument that architects from diverse social identities can, by virtue of being positioned outside the parameters of the current dominant cultures of architectural practice, make significant innovations and contributions to design and building practice, we sidestep the uncomfortable knowledge not only that sexism, racism, classism, gender, ableism, and colonisation currently constrict who practices architecture but also how architecture is practised. This research appreciates both what Woodard Smith is telling us and also Burns’ invitation, and what follows is an in-depth examination of the interplay of gender and professional identity in architecture. Through a large survey (n = 684) and qualitative career history interviews, it analyses the perceptions and lived experiences of both male and female architects and participants who have left the professional practice of architecture. We find significant differences between men and women in the perception of the salience of their gender with regard to their career. In line with other studies of male-dominated professions (Faulkner, 2009; Mease and Neal, 2023) we find that the relationship between gender and professional identity in architecture is complex and multifaceted and overall is characterised by the apparent paradox, which is that we must dismantle the notion that there are essential gendered differences between male and female that regard women as inherently less capable architects, whilst also arguing that the social experience of gender difference (and other intersectional identities) within what remains a masculinist profession impacts negatively upon their careers. That the expectation to be the ‘ideal worker’—totally committed, always available, able to work long hours, and whose outside responsibilities do not interfere with their paid work (Acker, 1990)—reinforces glass ceilings and creates the conditions within which it is preferable to leave the profession than to survive it.

This article begins by exploring the literature on the formation of the architect identity, on women in the profession, and on gender and professional identity with regard to architecture. It then briefly outlines the historical context of gender and professional identity for women architects, followed by a brief overview of women in the profession in Ireland. The methods used are then delineated, followed by the results and discussion.

1.1 Architecture, gender, and professional identity: literature

Architects, as members of an archetypal profession, form strong professional identities (Ahuja, 2023). A series of studies in the USA in the eighties and nineties applied sociological and ethnographic methods to architects and their practices, such as Judith Blau’s groundbreaking 1984 study of architectural practices in New York, Gutman’s (1988) study, which observed a gap between the espoused ideal of architectural practice and reality, and Dana Cuff’s influential Architecture: The Story of Practice (Blau, 1984; Gutman, 1988; Cuff, 1991). Cuff’s early study concluded that becoming an architect was a process of ‘learning socially appropriate cues for creativity,’ in other words, a process of assimilation into the culture of architecture (Cuff, 1991, p. 154). More recently, Sumati Ahuja et al. have observed the strategies employed by junior architects to cope with the sense of disillusionment felt when the ‘ideal professional self’ is revealed as a ‘false promise’ (Ahuja et al., 2019). Paradoxical identity responses have been observed with regard to architects and how they adapt to the changing nature of architectural work and other identity threats (Ahuja et al., 2017; Ahuja, 2023; Shahruddin and Husain, 2024).

Paradoxical responses also arise in the confluence of gender and professional identity. Women working within male-dominated professions face challenges both in the formation of their profession identity and the perception of that identity by others. In a Foucauldian analysis of women’s embodied identities at work, Angela Trethewey concludes that the ‘Women’s ability to form their own identities using strategies of ‘gender management’ [or ‘fitting in’], … are undermined, because professional discourse constitutes subjectivity in the corporation’s ‘masculine’ image’ and she observes that ‘women continue to approach the problem of ‘fitting in’ as a personal and individual problem’ (Trethewey, 1999, p. 426).

In the early twenty-first century, a series of UK-based studies began looking at women’s experiences in the architectural profession in particular and/or in contrast to men’s experiences, their reasons for leaving the profession, and the strategies employed by those who stayed to overcome, or more correctly, to adapt themselves or their careers to accommodate or bypass these issues altogether (Fowler and Wilson, 2004; De Graft-Johnson et al., 2005; Caven, 2006). Working with collaborators, Elena Navarro Astor, Marie Diop, and Vita Urbanavičienė, Valerie Caven’s research has produced important cross-national studies which show that women architects experience inequality everywhere, even where there is a supposed ‘equal environment’ (Caven et al., 2012, 2016; Caven and Navarro Astor, 2013; Caven et al., 2022). Inés Sánchez de Madariaga has shown the structural factors limiting women’s professional careers, resulting in a ‘glass ceiling’ for women architects (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2010). Women working in the architectural profession have also been found to be at greater risk of poorer occupational health and wellbeing than their male colleagues (Sang et al., 2007).

Women walk a tightrope between reproduction of masculine norms and identities and transformation and/or resistance to them. The tension between ‘co-opting masculine discourse in ways that risk reinforcing it, with challenging and resisting practices that privilege masculinity,’ is a form of gender paradox (Mease and Neal, 2023). For example, the ‘denial/acknowledge paradox’ wherein ‘women explicitly deny that gender has affected their experience, but also describe the many ways it affected their experience’ (Mease and Neal, 2023). Following Putnam and Ashcroft’s reminder that paradox ‘activates constraint and creativity, as well as ‘impossibility and potential,’ Mease and Neal, identify creativity and potential in paradoxical ‘enthymematic narratives’ employed by women (Putnam and Ashcraft, 2017; Mease and Neal, 2023). Such denials of disadvantage were also found by Agudo Arroyo and Sánchez de Madariaga, in their 2011 study of Spanish women architects. They found that there was an “often unconscious and involuntary concealment of then [gender] differences that, more or less explicitly continue to exist,” and an almost non-existent reflection of gender within the profession of architecture (Agudo Arroyo and Sánchez de Madariaga, 2011). Similar paradoxical denials were also found in the study described here.

Other strategies employed by women architects have also been identified; the alternative career path strategy identified by Caven, the ‘usurpatory’ and ‘resigned accommodation’ identified by Fowler and Wilson in their influential 2004 Bordieu-framed analysis (Caven, 2004; Fowler and Wilson, 2004; Caven et al., 2012). The ‘in/visibility paradox,’ faced by women in male-dominated professions—at once highly visible as a woman, yet professionally invisible’—‘brings contradictory pressures—to be ‘one of the lads’ but at the same time ‘not lose their femininity’ (Faulkner, 2009, p. 169). A study of white women and BME legal professionals in the UK found that of the six career strategies identified—‘assimilation, compromise, playing the game, reforming the system, location/relocation and withdrawal’—only one was likely to transform existing structures, perhaps, as the authors suggest, accounting for the rarity of structural change in the profession (Tomlinson et al., 2013). An analysis of gendered working practices and individuals’ resistance or complicity with gendered norms—long working hours, homosocial behaviour, and creative control—found that certain types of men—white, heterosexual, middle class—were able to transgress gendered norms, to challenge aspects of hegemonic masculinity within architectural practice culture and suggested that women, in adhering to these aforementioned gendered norms of architectural practice, reproduce them (Sang et al., 2014).

The members of the Australian research and advocacy group Parlour, founded by Naomi Stead, Justine Clark on foot of the Equity and Diversity in the Australian Architecture Profession: Women, Work and Leadership, 2011–2014, have been publishing research on this issue for a decade or more (Clark and Matthewson, 2013; Burns et al., 2015; Clark, 2022). Parlour’s work marks a shift towards research as an active agent for change in this sphere. Similarly, A Gendered Profession, an edited volume of essays published in 2016, marked a move towards a more proactive stance, or as the editors put it, ‘towards something more propositional, actionable, and transformative’ (Brown et al., 2016).

1.2 Architecture, gender, and professional identity: historical context

Professional and gender identity have been intertwined for women architects since their earliest admittance to the profession (and before). Ethel Charles, the first woman to be admitted to the RIBA in 1898, presented a nuanced view of gender norms in a 1902 article. On the one hand, she argued that women had a natural instinct for the beautiful, whilst on the other, she rejected the idea that women had a special ability for domestic planning, arguing that it was ‘common sense’ and therefore as obvious to men as to women (Charles, 1902, p. 180). Charles’s nuanced view is somewhat unusual, as the recourse to women’s expertise in the domestic sphere and therefore their assumed natural ability for the design of domestic spaces is a trope which is repeated right into the latter decades of the twentieth century (Walker, 2012). A recourse to domestic expertise was routinely proffered as a way to remain feminine, as women doctors had done with regard to gynaecology (Stratigakos, 2001, p. 97). Another interpretation of the appeal to domestic expertise may be that women architects found within it a stronghold of autonomy wherein they could be the expert on the subject.3

The aforementioned Florence Fulton Hobson also reconciled her position as an architect by referring to the domestic (Poppelreuter, 2017). In 1911, Fulton Hobson anonymously published an article, ‘Architecture as a Profession,’ in The Queen (Florence Fulton Hobson, 1911). Though, as Tanja Poppelreuter notes, the general matter-of-fact upbeat tone of Fulton Hobson’s article is somewhat deflated by her warning against the strain of taking on an identity other than one’s true self, which she delivers by quoting Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis:

Those who undertake something that is not part of themselves will achieve that, but will be nothing more … A man whose desire is to be something separate from himself … invariably succeeds in being what he wants to be. That is his punishment. Those who want a mask have to wear it (Florence Fulton Hobson, 1911).

Wilde warns of a denial of selfhood to fit with a desired identity. This is a theme which is threaded through the confluence of professional and gender identity for women architects. Especially, as will be shown, in the adoption of a persona or mask as a coping strategy in a male-dominated working environment and in the perception of their professional identity by wider society in opposition to their own personal conception. More than 100 years after this article, the easy and straightforward intersection of gender identity and professional identity appears to remain unresolved. The default gender for architects remains male (middle class, white, and able-bodied), and therefore anything which is not the norm is ‘othered.’ There is a cognitive battle going on, the desire to deconstruct the patriarchal default versus the labelling or ‘othering’ of women, thereby—as Simone de Beauvoir conceived it—imprisoning them in their gender (Moi, 2008).

1.3 Women in architecture in Ireland

The RIAI (Royal Institute of Architects Ireland) was established in 1839, 5 years after the foundation of the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects). Today, the RIAI serves as both the professional association and the registration body for architects and architectural technologists. The first woman to be admitted to the RIAI was Kathleen Mary Carroll (1898–1985) in 1927 (Pollard, 2024). However, Florence Fulton Hobson is identified as the first professional woman architect in Ireland, having been granted her licence by the RIBA in 1911 (Irish Architectural Archive, 2023). The early decades of the twentieth century were a hopeful time for Irish women aspiring to break into the male professions. Following the partition of Ireland and a significant break from colonial rule for 26 Irish counties, the 1922 Constitution, most specifically in Article 3, allowed for a weak but somewhat effective protection of women’s rights in that it guaranteed: “Every person, without distinction of sex, … shall within the limits of the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann) enjoy the privileges and be subject to the obligations of such citizens” (Mohr, 2006, p. 36). A series of articles published in The Irish Times during this time actively encouraged women to consider architecture as a profession (Bawn, 1909; Shamus, 1917; Weekly Irish Times (1876–1920), 1918; The Irish Times (1921–), 1921).

In the new Irish Free State, the strong influence of the Catholic Church extended its reach to virtually every aspect of society, especially women’s work outside the home (Valiulis, 2019). The introduction of a new constitution in 1937 was resisted at the time by Irish feminists as it removed Article 3, which enabled women to argue for parity in work and public life, and it further introduced articles which relegated women solely to their “duties” to provide unpaid work in the domestic home4 (Luddy, 2005). In the 1930s, the state formally introduced a ‘marriage bar’—wherein single women were required to resign from their jobs when they got married, and married women were disqualified from applying for jobs (Valiulis, 2019, pp. 83–87). The bar, which lasted for 27 years longer in Ireland than it did in the UK, had far-reaching effects. It permeated the working culture of the private sector and had a chilling effect on women’s participation in work outside the home, especially for middle-class educated women (Foley, 2022, pp. 70, 83). Until the marriage bar was lifted in 1973, the majority of women architects practicing in Ireland were either unmarried or married to architects with whom they practised (Pollard, 2024).

In the twenty-first century, the Marriage Equality Act of 2015—which legalised gay marriage—and the repeal of the eighth amendment—which gave women access to abortion—are significant milestones towards equality. However, as Cullen and Corcoran argue, ‘[in 2020,] the deep-structured gender divisions and forms of gender knowledge that almost imperceptibly frame our institutions, processes and practices remain largely intact’(Russell et al., 2017; Cullen and Corcoran, 2020, p. xvii).

In the broader construction industry, women make up under 10% of the total construction workforce in Ireland (DFHERIS, 2023). There have been various initiatives aimed at attracting women into construction, such as Future Cast, an organisation which is supported by a number of government departments (Construction Innovation Centre for Ireland, 2024). The Construction Industry Federation (CIF, 2018) published a report on women in construction in 2018 as well as various awareness initiatives (CIF, 2018; CIF, 2024). In 2023, the Department of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science (DFHERIS) published a report on careers in construction, noting gender differences in the perception of the construction industry (DFHERIS, 2023). This was followed by a social media campaign ‘Building Heroes’ aimed a ‘dispelling myths about what a career in construction is really like’ (Building Heroes, 2024). However, the challenges which face the construction industry with regard to attracting female entrants are not the same as those within the architecture profession, where the challenge is to retain female architects. There has been near parity in the ratio of male to female students in architecture in Ireland since the 1990s (Russell et al., 2021).

In 2022, only 30% of registered architects5 in Ireland were women. A similar proportion is found in the UK at 31% (ARB, 2023). Both countries are lagging behind the average of 43% of women architects in the 26 EU countries, based on ACE (Architects Council of Europe) data for 2022 (Mirza & Nacey Research Ltd, 2023). In 2021, amongst RIAI-registered practices, women principals accounted for 16% (Pollard, 2021). In recent years, the RIAI has begun to give the issue of gender in the profession greater attention. It holds an annual ‘Women in Architecture’ networking event, which is curated and hosted by former president of the RIAI, Dr. Carole Pollard. The RIAI also played a large part in the ‘Women in Architecture’ taskforce established by ACE in 2018. In 2020, the ACE taskforce published a Gender Policy Statement, and in 2023, the ‘A/B/C: Gender balance, diversity and inclusion in architecture’ in their words, is ‘a call to action, a handbook, a manifesto, a practical tool for change’ (ACE, 2023). The impact of the handbook on the culture of professional practice remains to be seen. It should also be noted that the research described here is part of a larger research project, Gender Equity in Irish Architecture, which is co-funded by the RIAI, reflecting the institution’s desire for more research on the issue of gender in the profession. There are currently no specific women in architecture groups established in the Republic of Ireland, though, through the Gender Equity in Irish Architecture research project, it is planned to establish a broader ‘Women in the Built Environment Professions’ group, building upon the success of an academic and professional conference organised by the authors in February 2024.6

2 Methods

2.1 Theoretical framework

A constructivist approach to gender, identity, and (in)equality underpins this research (Berger and Luckmann, 1966; Butler, 1988). Gender is acknowledged as socially constructed and connected to social, economic, and cultural status and power in society. It is theorised as a social division rather than an innate and essential difference, and when referring to ‘men’ and ‘women’ in this article, persons who identify as men and persons who identify as women are implied and included (Cullen and Corcoran, 2020, p. xx).

2.2 Survey

The ‘Irish Architecture Career Tracker Survey’ was launched on 28 March 2023 and ran for 10 weeks. It was not called the ‘Gender Equity in Irish Architecture Survey,’ so as not to dissuade men from taking part. When we have social privilege, we tend to assume that our dominant social identity is the unmarked norm, and those whose identities are adversely impacted by racism, ableism, classism, and sexism are the ones who are called on when studies seek to explore race, ethnicity, disability, gender, and so on. The survey was conducted online, was anonymous, and asked over 100 questions.

The design of the survey questionnaire combined newly developed questions with adapted questions from other surveys, in particular Eurobarometer gender equality surveys and the European Social Survey (ESS; O’Connell et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2012, 2013; European Commission and European Parliament, 2015, 2017; ESS, 2020; YesWePlan!, 2020). A mix of tick-box, Likert scale, and open questions were used. The survey encompassed basic profile questions, such as age, gender identity, geographic location, occupation(s), and qualifications, before questions on working conditions, attitudes towards, and experiences of, gender equality, and possible solutions to increase the number of women.7

The target population was people (of all genders) who were working on the island of Ireland and either had a degree in architecture (or architectural technology) or who considered themselves to be working in architecture (however, they themselves define architecture). Participants were not required to be registered architects or architectural technologists. This was to get a sense of what our respondents considered to be ‘working in architecture’ beyond the traditional professional practice role and so that responses from those who have left the profession could also be compared and included.8

Non-probability, convenience sampling was used. Participants were recruited through advertising on social media, professional and alumni newsletters, and social media amplification by architecture-related bodies such as the Irish Architecture Foundation and the Architectural Association of Ireland. Participants were given one CPD (Continuing Professional Development) point for taking part in the survey.9

The survey had a strong response rate of 684 completed questionnaires. The respondents ranged in age from 20 to 72. Two-thirds of respondents (66%) were aged between 25 and 44, meaning early-career professionals are well represented, and 88% were aged between 25 and 54. Of the 684 completed questionnaires, 59.6% of respondents were identified as female, 40% as male, and less than 1% preferred not to say or ‘other.’10 Women are therefore overrepresented in the sample. Registered architects accounted for 68% (463) of the respondents, 26% had never joined the register, 3% had left the register, and 2% were registered architectural technologists.

2.3 Interviews

Between September 2023 and January 2024, we carried out 23 semi-structured qualitative interviews with volunteers recruited based on their participation in the survey. Survey respondents were offered an opportunity to volunteer for an interview on completion of the questionnaire.

All interviewees were given a brief questionnaire to fill out before the interview, which allowed for an outline profile of each interviewee to be created. Overall, 14 women and 9 men were interviewed. All of the interviewees were located in urban centres with the majority (14) being located in the greater Dublin area. The age range was from 32 to 62 years old. The mean age was 43.7 years.

A range of types of employment are represented: seven employed in the public sector, nine private sector employees, four self-employed with employees, and one self-employed without employees. The interviewees were primarily ‘architects working in the professional practice of architecture’ (15), with the reminder split as follows: ‘working in the broad field of architecture’ (3), ‘an architect, not working in professional practice’ (3), and finally, one interviewee indicated that they were both ‘an architect working in professional practice,’ and ‘working in the broad field of architecture’ (1).11 The slight muddiness of these definitions is reflective of the fact that not all architects are registered, not all registered architects are working in professional practice, and most importantly, as will be discussed, that the title of architect, once earned, is not relinquished lightly. For the purposes of the analysis presented here, it is sufficient to differentiate between those ‘working in professional practice’ (15) and those who are not (7). None of the interviewees considered that they had left the discipline of architecture entirely. This reflects the difficulty in accessing this cohort and perhaps the limits of the convenience sampling method used in the survey, which also served as the recruitment method for interviewees.

We developed a semi-structured interview protocol using a career history approach (Caven et al., 2016). This approach encouraged participants to talk about their experiences as well as events or influences which had shaped their career trajectory.12 The two particular questions, which are the focus of this article, ‘How important is being a woman/man to the way you think about your career?,’ and ‘What are your thoughts and feelings around the woman in architecture label?’ were asked at the end of each interview so as not to skew their earlier responses. The interviews lasted between 40 and 90 min, and with one exception, all were conducted in person, one being conducted online over Zoom. An audio recording of the interviews was made and subsequently transcribed.

We conducted the analysis using Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis (RTA), as ‘it emphasises the importance of the researcher’s subjectivity as analytic resource, and their reflexive engagement with theory, data and interpretation’ (Braun and Clarke, 2019, 2021). Given my own status as a former architect and as a woman who has left the professional practice of architecture, though not the wider field of architecture, this method is particularly appropriate. Recognising my own ‘insider knowledge’ we were careful whilst conducting the interviews to draw out any tacit knowledge by asking interviewees to explain further.

The interviewees’ responses to the two questions, ‘How important is being a woman/man to how you think about your career?’ and ‘What are your thoughts and feelings around the woman in architecture label?,’ were coded inductively without pre-conceptualised themes in mind. The analysis of these responses was done in the context of the whole career history interview, cognisant of the importance of an individual’s life story and their lived subjectivity.

3 Results

Reflecting the research design, this section will first present the results of the two questions extracted from the survey, followed by a qualitative analysis of the interview data.

3.1 How important is being a woman/man to the way you think about your career?

The survey asked respondents who identified as women to indicate, on a scale from 0 to 6, with ‘0’ being ‘not at all important’ and ‘6’ being ‘extremely important,’ ‘How important is being a woman to the way you think about your career?’ (Respondents who identified as men were asked, ‘How important is being a man to the way you think about your career?’13) Comparing the responses for men and women, we can see that the two charts are the inverse of one another (Figures 1, 2). The male respondents tended towards ‘0, being a man is not at all important to the way I think about my career,’ at 45% (female respondents, 7%), whilst female respondents tended towards the opposite ‘6, being a woman is extremely important to the way I think about my career’ at 41% (male respondents, 2%). This is perhaps unsurprising given that in Ireland, as in many other countries, ‘male’ remains the default gender of architects, and the default does not require consideration. However, the stark contrast between male and female responses to this question was not expected, which prompted the inclusion of this question in the interview protocol.

3.2 The term ‘Woman in architecture’ is an important reflection of who I am professionally

The survey also asked respondents who had identified themselves as women to indicate their level of agreement with the statement: ‘The term ‘woman in architecture’ is an important reflection of who I am professionally,’ with response options; ‘agree strongly,’ ‘agree,’ ‘neither agree nor disagree,’ ‘disagree,’ ‘disagree strongly,’ and ‘do not know.’14 (Respondents who indicated that they are not working in architecture were excluded from this analysis, n = 385.) There is a spread in the range of responses, with no strong majority favouring agreement or disagreement (Figure 3). Overall, 40% of respondents either agreed or agreed strongly that the term ‘woman in architecture’ is an important reflection of their professional identity, whilst 26% either disagreed or disagreed strongly.

A more nuanced picture emerges when we look at these responses by age. In the 25–34 age group, 48% favoured agreement, whilst in the 35–44 and 45–54 age groups, 33 and 36%, respectively, agreed (Figure 3). Based upon these data, younger women, likely to be those starting out in their careers, appear to be more comfortable with the ‘woman in architecture’ label than their older, more experienced colleagues. This is perhaps significant in registering a diminishment of sexist connotations in the term ‘woman’ and a concomitant interest in signalling a distinction that might be a positive difference.

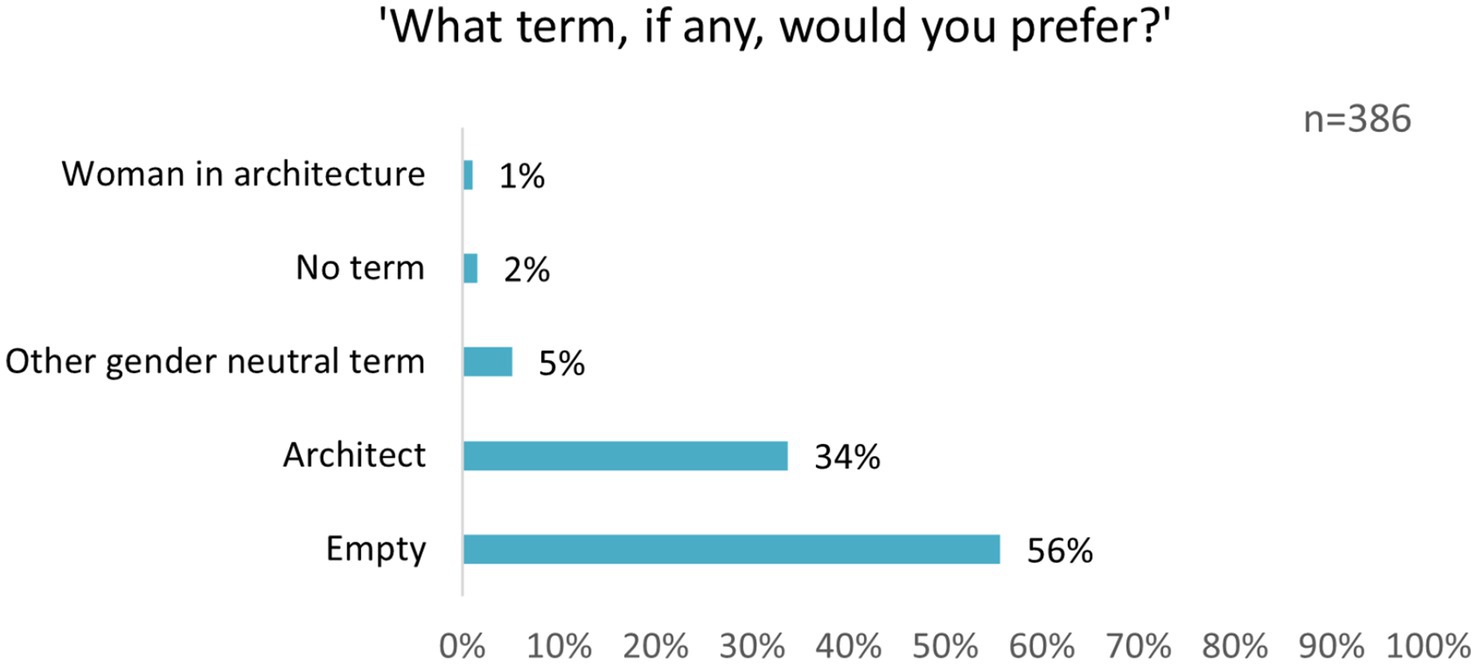

3.3 I am an architect

Whether or not they agreed or disagreed with the ‘woman in architecture’ statement, all women were asked the follow-up open question: ‘What term, if any, would you prefer?’. Overall, a slight majority of respondents, 56%, left this field empty there, possibly indicating tacit approval for the term ‘woman in architecture’ (Figure 4).

Figure 4. What term, if any, would you prefer? Preferred alternate terms. *Other responses of <1% each are not shown.

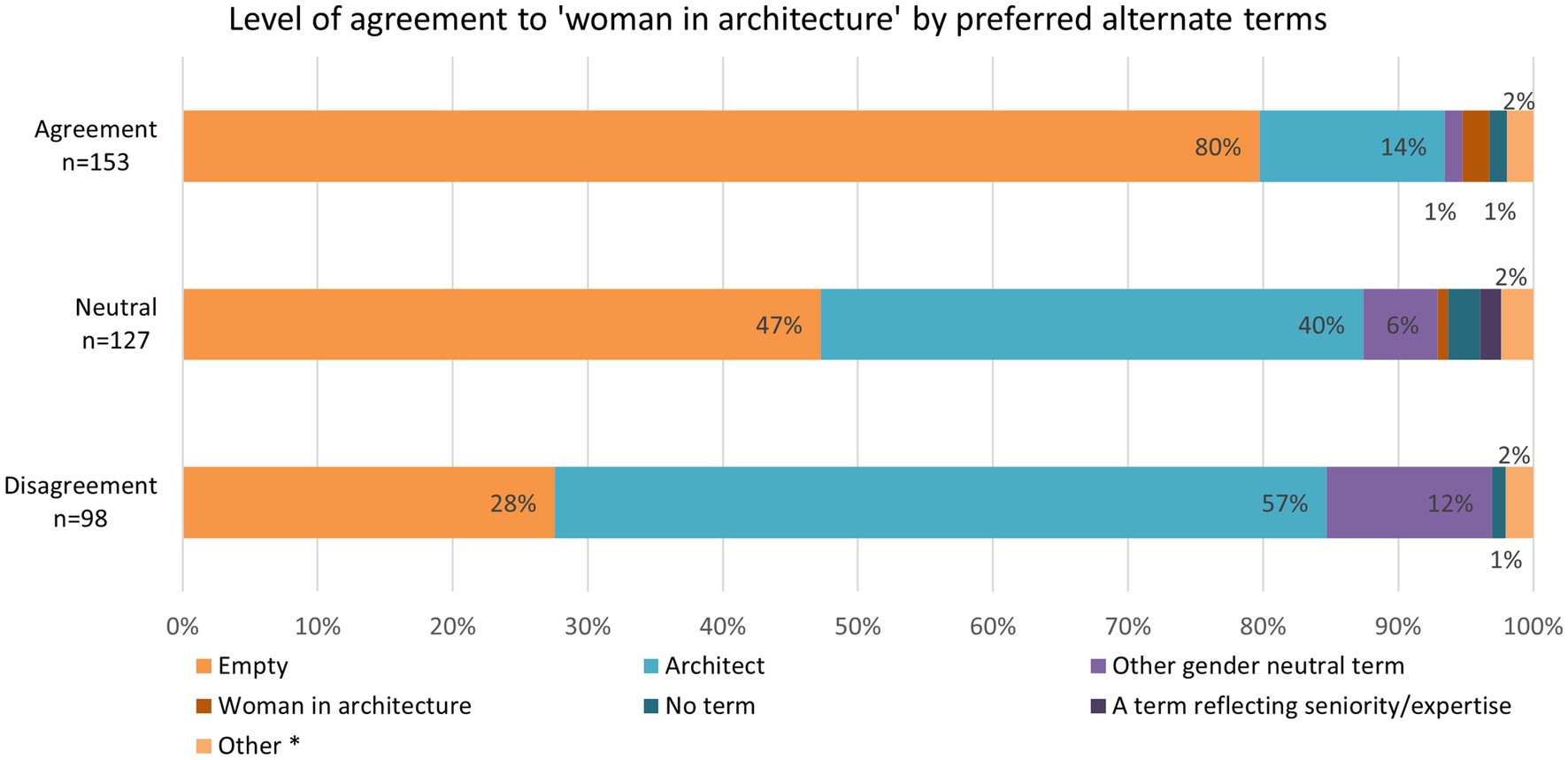

For a more nuanced analysis, we can look at the responses in agreement or disagreement with the ‘woman in architecture’ statement (Figure 5). This tells us that of those who indicated agreement, the majority, 80% (122) left the field empty, which suggests that the ‘empty’ response is indeed a tacit approval of the term ‘woman in architecture.’ However, even amongst this ‘agreement’ group, 14% (21), still indicated a preference for ‘architect.’

As might be expected, 57% of those who disagreed with the term ‘woman in architecture,’ responded that ‘architect’ was their preferred term. Of those who were neutral about the statement, 40% responded that ‘architect’ was their preferred term and 47% left the field empty.

With hindsight, the wording of this question means that it is difficult to interpret ‘empty’ responses definitively. However, the responses we have indicate a strong degree of discordance amongst our respondents to the term ‘woman in architecture.’ Of the 172 who did not leave the response empty, 130 (75%) indicated a preference for ‘architect,’ with 81 of those simply writing ‘architect,’ one respondent doing so in all capital letters, ‘ARCHITECT.’15 Those who took the opportunity to expand upon their answer generally did so in a forthright manner, expressing the intensity of their feeling. Analysing these responses using the same RTA method used for the qualitative interviews, a number of themes were identified. Many expressed annoyance at being ‘othered’ —men do not have to differentiate why should we?

I do not see why I should define my professional role according to my gender. Men never have to do that (Woman aged 45–54).

Architect. Drop any reference to gender, no one speaks of ‘men in architecture’ so why make a point of highlighting your gender, it makes it seem like you are different. I have a huge issue with being referred to [as] a woman in architecture or a female architect (Woman aged 35–44).

Architect. “[W]oman in architecture” implies that the individual is part of a subsection. One never heard of “man in architecture.” (Woman aged 35–44).

Others expressed a desire for a gender-neutral term, such as ‘architect’ or another, coupled with a desire to be considered on merit alone.

No term, if we are looking for equality then there should be no differentiation between architects based on gender or any other criteria other than expertise (Woman aged 45–54).

Architect … Gender should not matter, that’s the point. We are looking for equality, not special treatment (Woman aged 35–44).

Some indicated that they recognised a need for the term ‘women in architecture’ but wished that it was no longer necessary.

Architect. I’d love to live in a utopia where gender does not matter, but we are not there yet so I agree that it’s important that I am a female architect (Woman aged 35–44).

For some ‘architect,’ denotes respect, a title they have earned.

[Architect]. That’s how I was referred to in private practice by clients, contractors, consultants etc. and it was important for me that there was never any distinction between a male architect and a female architect. It showed respect that I was referred to as the architect rather than ‘she.’ (Woman aged 45–54).

Architect. I am an architect because I worked hard to achieve the title not because I am a woman.… (Woman aged 25–34).

At one point it was important to me to be ‘female architect,’ when I was starting out, but through experience in the workplace and on site, I feel the term ‘architect’ is as powerful, to be considered equal (Woman aged 35–44).

This rejection of ‘woman in architecture’ might seem to be at odds with the importance women place upon their gender with regard to their career, which we have seen in response to our earlier question, ‘How important is being a woman to the way you think about your career?’ We might begin to understand this as the difference between a personal and perhaps private acknowledgement that being a woman has been significant in their career and a wariness about adopting a gendered public-facing label. As one of the respondents states:

Being a woman influences my approach to my profession, but this is not how I would like to be defined—I am an architect (Woman aged 45–54).

The label ‘woman in architecture’ is a public-facing statement, and as such, how it is perceived and the positive or negative connotations associated with it are beyond their control. This issue is summarised by one of the respondents:

Architect—a gender-less term with no preconceptions (Woman aged 25–34).

It seems that implicit in many of the rejections of the ‘woman in architecture’ label are strong acknowledgements of sexist contexts and concerns that the label might consolidate rather than dismantle that sexism, as encapsulated by the following respondent:

Singling out Women separate from men now does not strengthen it, it weakens us in that it gives a sense we are delicate and we need support, it gives a sense that we are scared and need other women support to make it through (Woman aged 45–54).

Such sentiments were also expressed by the interviewees, as will be discussed in the following section.

3.4 Women in architecture? Yeah but… No, but…Maybe…

The ‘Yeah but… No but…Maybe,’ theme was identified in the interviewees’ responses when asked for their ‘thoughts and feelings around the ‘woman in architecture’ label.’ It encapsulates the ambivalence of some toward the label, the qualified support of others, and the qualified rejection expressed by others. Only one woman offered unqualified support for the label. Of the remaining women, half expressed negative sentiment towards the label. Aligning with the concerns expressed in the survey around consolidating rather than dismantling sexism, interviewees primarily rejected it because they view it as othering, as setting up a ‘girls club’ and as therefore undermining the perception that they are equally capable as men:

Yeah, I am an architect … It’s a bit like, it’s a bit like other labels being applied to women at the moment and I’m like no I’m a woman. And I will not have any prefix, prefix because it undermines ‘I am a woman.’ Same with ‘I am an architect’ and I think adding something in front of it makes it. I’m the other kind of architect. It like, ‘no, no, I am an architect.’ (Ruth, architect working in professional practice, woman aged 45–54).

The desire to be considered on merit was also mentioned in parallel as a reason to reject the label.

Those women who were positive towards the label (six of the 13 women) qualified that support, stating that it was because it was needed and lamenting its necessity. One interviewee expressed support for the label but at the same time rejected it for herself:

Oh yeah. Women in architecture. Well, I do have thoughts. I think it’s important that we keep saying women in architecture because they are so few of us left and it is hard and it is, you know, it is harder than it is for our male counterparts, for lots of different reasons. I mean, there are different challenges, obviously. I suppose, I struggle a little with bit with the being a “woman architect” or a, you know, a “female architect” that, you know, so I’m an architect. But I have no problem with the shouting about women in architecture and being taught, you know, being really, really clear that there are structural challenges around what we try to do (Patricia, an architect not working in professional practice, woman aged 45–54).

This response exemplifies the dilemma facing women around this label, even though they recognise a need for it to counter the structural barriers that women face or simply to offer support in a male-dominated industry, they are not comfortable with the ‘othering’ they perceive the label brings with it.

Male interviewees, in general, seemed unsure and also qualified their support for the label; yes, because we still need it; yes, but as a protest, not as segregation; yes, but ‘women in construction’ is more necessary. Some also qualified their uncertainty; I do not know, but why differentiate? Women are as capable as men; I do not know, but it signals ‘this is not for men.’ Some were more definitive in their support of the label, citing its necessity, with the most strongly expressed view referencing misogyny:

And so I mean, I think misogyny is rife. It’s there all over the place. We’re, men, are particularly poor at spotting it. But when you spot it, you are kind of tripping over it. Everywhere. So, I think you do have to try and call out the fact that there’s still serious, systemic institutional inequalities there. And if we stop, discussing the, or just stop somehow trying to highlight those issues, then I’m not sure what would happen? I presume that it would get worse I think. Unfortunately, I think you do still have to talk about women in architecture (John, working in the broad field of architecture, man aged 45–54).

3.5 It’s imprinted in my DNA

Threaded through much of the interviewees’ descriptions of their career histories was the issue of the identity of being an architect as something they were or aspired to be, or felt outside of, or resisted. They felt that they were not producing design-led work or architecture with a capital ‘A.’ They had not fulfilled their potential as designers. They had not achieved the ‘pinnacle’ as described by Jill:

The aspiration was to be your own practice lead or to have your own practice. And that was the ultimate goal. And those who were held up as the kind of figureheads or the heroes was somebody who set up their own practice and won a competition and got an AAI16 award. That was the kind of pinnacle (Jill, working in the broad field of architecture, woman aged 35–44).

For one interviewee, not living up to this standard of exhibition-ready-architecture coloured not only her appreciation for her own work—‘Well, we have very low-key work. […] I’m not sure that you’d show it publicly’—but also the ownership she took of her architect title, ‘No, it just is what I am, but I do not, I, I never really use it and a lot of people do not even know, I think, that I’m an architect’ (Sheila, architect working in professional practice, woman aged 54–65). At once, architect is just what she is and, at the same time, something she does not proclaim. At the other end of the spectrum, Paula, who is no longer working in professional practice and who suffered harassment and discrimination within the profession, proclaimed:

Yeah, I’m still registered. Do my CPD. Call myself an architect. I feel like it’s, it’s imprinted in my DNA. When you go through a school of architecture it’s imprinted in you (Paula, working in the broad field of architecture, woman aged 45–54).

For those who have left professional practice, the identity of an architect remains important: ‘I still call myself an architect. […] I cannot imagine a day when I will not call myself an architect’ (Patricia, working in the broad field of architecture, woman aged 45–54). Even those who had left professional practice decades ago expressed affinity for the title, usually in the form of a reluctance to fully commit to another, more accurate, description of their current occupation.

Feeling like an outsider was expressed by a number of male interviewees. Again, this took the form of not living up to the ideal architect—what one interviewee referred to as a ‘trope of the female architect’ which he summed by ‘architecture is life, life is architecture’ (Ben, working in professional practice, man aged 45–54). For other male interviewees, this sense that to be a true architect, all other identities or interests were irrelevant was a model that they felt themselves to be outside:

Look, I there’s some people out there that, you know, kind of live, eat and breathe and sleep architecture that’s not me (Gary, architect working in professional practice, man aged 25–34).

Probably not always feeling like I’m an architect at all, rather than, slightly like. Yeah, just that it’s not fully identifying with it I suppose every now and again. And that, that probably started early where you see people who were immediately identifying very obviously as, as you know, being architects are you know, you are out, you are out with people and you are going like can you just please stop talking about this and just have a conversation about sports or weather or anything else, you know? (Sam, architect working in professional practice, man aged 45–54).

3.6 More gendered than I care to remember

When asked, ‘How important is being a man/woman to how you think about your career?,’ most interviewees hesitated. Some asked to repeat the question or to explain further, which we did by asking if their gender had factored into their decision-making along their career trajectory. Men appeared to hesitate to answer more than women and seemed to be unsure of how to answer in a way that suggests that there may have been a desire to please the interviewer or a degree of social desirability bias present (Bergen and Labonté, 2020). Men also tended to interpret the question as asking whether being a man had been an advantage to them in their careers. They tended to respond initially that, no, being a man was not important to how they think about their career or had not been an advantage, but as they talked, they came either to the realisation that they had likely enjoyed an advantage or, under the influence of social desirability bias, felt that admitting the possibility of an advantage was a more acceptable response. For example:

Ah no. The answer is no. So being a man is what I am so I cannot think of my, anything, anything, this cup of coffee, you, building we are in, only from the perspective of a man cause it what I am, no more that you as a woman can think of, as a man. I mean people who are transgender, do not have the feeling to do that either, they can only think as themselves, so whatever they are at that time is how they think of things. So no I do not think so. So I’m not at all … that does not mean I’m in anyway blind to the fact that I may have gotten a career advantage from being a man, em, but not of my individual doing, certainly not of my doing down of women (James, architect in practice, man aged 45–54).

But, um, I’d struggle to answer that question. Probably not, would be my instinctual response, for a number of reasons. […] So I never, I think, so I like to believe I never experienced quite as much, gendered situation as one might expect. Looking back at was probably more gendered than I care to remember it. Um, but I think, that’s the story I tell myself (Bill, architect not working in professional of architecture, man aged 45–54).

‘More gendered than I care to remember’ also encapsulates the paradoxical responses of some female interviewees to this question, wherein, having just described major career choices they made along their career trajectory for the betterment of their family or because of caregiving responsibilities, they then respond negatively or ambivalently to the ‘how important is being a woman to how you think about your career?’ question. For example, choosing to work in the public service on account of the greater job security, stability, and family-friendly working conditions the public service provides, and simultaneously a reluctance to admit to their gender, being a woman, as being important, either as a factor in their career or to how they think about their career. Jane (whose husband is also an architect) made the decision to get a public sector job for greater job security when they had a child:

Interviewer: Do you think being a woman is important to how you think about your career?

Jane: I do not know because I do not know how a man thinks about this. I can only think of how, I think about my career and it, you know, it’s just trying to balance everything. I mean, you know.

Interviewer: Yeah. Do you think it’s had an impact?

Jane: Not here, but it certainly would have had an impact I think had I have stayed in the private sector, I think it would because, that, that requirement to do over and above late into the evening, you know, you just could not do it. It’s not fair (Jane, architect not working in professional practice, woman aged 55–64).

For some (8), there was an immediate recognition of their gender as an important factor in their career decisions and consequent trajectory as being influenced by their gender, especially those with children. However, amongst the recognition, there were also contradictory responses, for example, Ann:

I think they are so entwined that I definitely think women probably plan their careers around family. […] I do think that I probably take the fall and my, my like salary and my career has obviously been generally lower because I’ve kind of let my husband advance more so that we can support the life that we have set up (Ann, architect in professional practice, woman aged 35–44).

But when asked, ‘do you think being a woman has had an impact on your career overall?,’ Ann responded:

I do not know. It’s hard to tell like whether you, I suppose you really need to talk to kind of people who are employing a lot of people to find out ask them honestly like would you pick a male or female candidate, or does it solely come down to what they can do or their skills or their presentations or.? You know, and I do not think that it’s advanced me in any way, but I do not know that it has held me back either really (Ann, architect in professional practice, woman aged 35–44).

Here, Ann seems to equate the impact of her gender with whether or not she has been subject to discrimination. Or Ruth, who begins by recognising gender as a factor in her career but goes on to say that she ‘has not allowed that to be a factor’:

Ruth: Ah, it has a bit, of course, yeah, yeah. Especially, I remember in […] with that man, that man. I went to site and it was a huge project, and I must have been the only female in a three mile radius and all these lads going ‘woo ooo’ … […] And I think we you start getting into a situation where you might want to have kids, and suddenly it’s question of ‘how do I balance this?’ Because there was no way I was leaving it. […] I do not know, if it’s changed, if it’s factored in any other ways (being a woman). I think maybe I’ve used it a little bit […] if there were a lot of women usually in the meetings, they’d be very aggressive, very hardcore meetings and if somebody had a baby crying, I’d go ‘Jesus,’ I’d use it like ‘uh, like I’d my own like, little one crying this morning going off to school.’ […].

Interviewer: The major decisions along the way in your career, do you think it was … Did it (being a woman) influence, your decisions?

Ruth: No, I could not. Like I kind of ignore it in a way. I have not, em, I have not, I have to say, I have not played up to the stereotypes or like I have not expected to be treated any differently. I have not allowed that to be a factor. I like I’ve ignored it. I have not gone in ‘look it I’m a woman.’ I’ve ignored it, and mostly that has been reciprocated (Ruth, architect in practice, woman aged 45–54).

Others, such as Jill, also recognised the impact of her gender: ‘I think I tend to do what a lot of women do, which make a lot of career decision based on family and care needs and children and what I can do,’ but at the same time to play down that gendered impact by putting some of the blame back on herself and her personal situation, Jill continues:

I think I would have had a different career trajectory, uh, had I not been, you know, having children. But maybe if I was in a relationship with someone, I would have had to make those decisions as well. So I’m not saying it’s purely female decisions, but I felt it was very sharply at times (Jill, working in the broad field of architecture, woman aged 35–44).

Where gender was recognised as an important career factor, it was almost exclusively related to caring for or having children, and/or the perception of others of the impact of having children upon career. Eve, for example, who has experienced a lack of career progression in her view because she is a woman with children:

Is it important? Well. it is well, it is important. Yeah, I would say, yeah, it’s it because it’s it defines you in a way, you know. And I think it’s because you are a woman sometimes it’s it shuts some doors in front of you (Eve, architect in professional practice, woman aged 35–44).

This finding illustrates Mease and Neal’s observation that ‘women explicitly deny that gender has affected their experience, but also describe the many ways it affected their experience’ (Mease and Neal, 2023). A similar reluctance to admit disadvantage was also found by Yolanda Agudo Arroyo and Inés Sánchez de Madariaga in their 2011 study of Spanish women architects (Agudo Arroyo and Sánchez de Madariaga, 2011).

3.7 The need for an on-site persona

The need to adopt a persona, especially whilst ‘on site,’17 was mentioned by female respondents—as something they felt they had to do whilst young—and by male respondents, as something they thought that women architects needed to do in order to be respected on-site.

You have to be a bit more stern. You cannot be as friendly sometimes on site. I think you need to kind of assert your authority or else they just will not really give you any kudos like to that you know what you are talking about (Ann, architect working in professional practice, woman aged 35–44).

[Speaking about women architects] I think it is part of the construction sector, on site, and dare I say it, being treated seriously and that takes either a facade or a deliberate persona that you can turn on and turn off (Ben, working in professional practice, man aged 45–54).

Female interviewees related that being perceived as not knowing about construction was a kind of benefit, as they felt that it enabled them to ask for guidance. Conversely, male architects spoke of a pressure they felt on-site to have an expertise beyond their experience simply by dint of being ‘the architect.’ Some male respondents recalled pretending to know what they were doing, whilst others spoke of developing a relationship with contractors wherein they could benefit from their experience. Not expected to know, female respondents took the latter approach, seeking to develop collaborative working relationships on-site.

On-site is where the female respondents felt their gender difference most acutely. As Sheila recalled, ‘not only as I said, ‘it’s the architect.’ But it’s a young architect, ‘god that is even worse.’ And then ‘oh my god, like even worse. It’s a female’ (Sheila, architect working in professional practice, woman aged 54–65). The building site is where they are mostly likely to be the only women present and where the incidents of sexual harassment reported by some of the female respondents have taken place. In this context, women architects are adopting a persona of ‘toughness’ on the one hand, whilst simultaneously seeking to build collaborative, mutually respectful relationships on-site, where conditions allowed, that is when they felt safe to do so professionally and personally:

I think when you are working with good people and everybody has the end goal in sight, you can just be yourself. But I think if you come across somebody who’s testing you, then it does force you to, just like, you know, you’d have to kind of push back, I suppose (Una, architect in professional practice, woman aged 35–44).

Women in mid-career spoke of becoming more comfortable on-site and advising younger women to ‘take the mask off and just be yourself. Just be straight, say it out and do not be afraid of the site, or the men on site, be human, because they are human’ (Ruth, architect in practice, woman aged 45–54).

This finding aligns with Ridgeway et al.’s (2022) study of architects, who found that those who are not the ‘ideal worker,’ who are not white male architects, ‘must walk a tightrope between authoritativeness and approachability’ (Ridgeway et al., 2022). A similar finding was also made by Sánchez de Madariaga in 2010, pointing to a need for ‘a model that allows a woman to be assertive and ambitious without her being labelled as an evil or hysterical ‘bitch” (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2010).

3.8 Surviving not thriving

Amongst both male and female respondents, there was a sense that a career in architecture was something to survive at rather than something to thrive in. Interviewees referred to the vulnerability of architectural workers in the boom-bust cycle of the Irish economy, where periods of relatively dramatic growth end swiftly in recession. For women, survival was also related to remaining a woman in a male-dominated profession and the wider construction industry; ‘I really want to demonstrate that it can be done.’ (Patricia, architect, not working in professional practice, woman aged 45–54). For both early and mid-career female professionals, survival, and remaining in the industry is an achievement:

To still be in the workforce at an older age is quite a feat because I know, I know from my personal experience, the struggles that you have and to be able to stay in the workforce is a big deal. It’s a bigger deal than for a man because of the pressures (Paula, working in the broad field of architecture, woman aged 45–54).

And

‘Amazing achievement to say you are a woman in architecture, forty years ago and hopefully in forty years’ time we will not need to say that.’ (Amy, architect in professional practice, woman aged 25–34).

3.9 Feeling equal but

Both male and female respondents reported a feeling of equality during their studies or early in their careers, coupled with a feeling of disappointment that this promise of equality had not been fulfilled.

I do not think it felt like that when I was starting out. You know like, like I did not notice that there was only four women in the office when I was doing my Part One, you know. Um, Yeah. That it did not seem important then. […] I think more of the expectation was that you’d be finding the issues on site or something like that, or not being listened to or respected, and that wasn’t happening for me for a long time (Alice, architect in practice, woman aged 25–34).

It’s always been, way back to college, you know, you would arrive in first year and it’d be 50/50. […] And then they [women] find themselves going into practice and it’s no longer an intellectual exercise. It’s a bit of a meat grinder […] I think women have it harder. Women in architecture have a harder role to play, particularly in big practice (Ben, architect in practice, man aged 45–54).

The disappointment with the lack of equality experienced in the workplace also took the form of a wish that they had been forewarned and forearmed:

I always took gender out of the equation, and I was taught in my professional practice course in [non-EU country] to disregard gender entirely. I think they did us a slight disservice. We should have taken all the girls aside and said, ‘yeah, disregard gender but watch out.’ They did not do that (Paula, working in the broad field of architecture, woman aged 45–54).

This was not the case for the older women (over 55) interviewed. For these older women, being one of the only women in the room has been the status quo since their student days.

The ‘feeling equal but…’ theme was also identified in interviews where a feeling of ‘being equal’ was expressed despite evidence to the contrary. For example, Ruth (architect in practice, woman aged 45–54) claimed, ‘I feel equal. I really do.,’ having just described earlier in the interview working in an office early in her career where male employees were watching porn on their computers at lunch time and later in her career, being brought in to ‘clean up a man’s mess,’ and working with a ‘misogynist’ who would ‘pull her down’ with sexist remarks. Other interviewees described feeling equal in (architectural) practice but not on-site or feeling that they themselves had not been subject to bias, though they feel that bias exists.

4 Discussion and conclusion

When taken together, the data presented here show a complex relationship between gender and professional identity, which means that women architects have to negotiate a paradoxical project: they are relatively recent entrants into a male-dominated profession which, in common with many professions, has defined excellence in masculinist terms, and they must resist those discourses whilst articulating a vision that both values their gendered lives, yet can fit in with the profession which routinely designs for general publics.

The mixed feelings revealed in this study which surround the ‘woman in architecture’ label reflect how women architects face a quintessential sexist dilemma of the kind identified by Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex. The crux of the dilemma was elucidated by Toril Moi, who explains that claims that gender (or race) should be irrelevant ‘force women … to ‘eliminate’ their gendered (or raced) subjectivity, or in other words to masquerade as some kind of generic universal human being, in ways that devalue their actual experiences as embodied human beings in the world,’ but ‘to run for office as the ‘black’ or the ‘woman’ candidate, will cut them off from what Beauvoir calls the ‘universal,’ the general category, and hence imprison them in their gender (or race) (Moi, 2008, p. 265). We see this negotiation of paradox in Ruth’s example of her ‘use’ of being a woman to connect with other women, yet at the same time claiming, ‘I have not gone in ‘look it I’m a woman.” We identified a similar tightrope walk between two contradictory approaches on-site, ‘being yourself’ (that is, being approachable and inviting advice) and a stern (authoritative) persona.

We also identified a similar paradoxical response in the ‘More gendered than I care to remember’ theme, wherein women described the influence of being a woman, in particular a mother, on their career trajectories, but were reluctant to frame their career choices through gendered or structural inequalities. This finding aligns well with other studies, such as Mease and Neal’s ‘denial/acknowledge paradox’ for women in male-dominated fields and Fowler and Wilson’s findings from their 2004 study that; ‘the women architects sampled usually found alternative explanations to offset their recognition of persistent gender inequalities,’ as well as the denial of disadvantage identified by Agudo Arroyo and Sánchez de Madariaga (Fowler and Wilson, 2004; Agudo Arroyo and Sánchez de Madariaga, 2011; Mease and Neal, 2023). The disappointment felt by interviewees about the unfulfilled promise of equality in architectural practice also aligns with Fowler and Wilson’s findings. They summarised:

The women architects’ responses were marked by a blend of illusion and anticipatory loss. A sizeable fraction had been lured by educational equality of opportunity to believe that women were only disadvantaged in traditional settings. In some such cases, the veil of equal opportunity had been roughly torn down: pregnancy, especially, revealed the absence of adequate maternity provision (Fowler and Wilson, 2004, p. 115).

It is indicative of the lack of progress about gender equality in the architecture profession that 20 years on from this influential study, this remains a fitting summary of women architects’ feelings on gender equality in the profession.

The findings presented here are limited by the fact that identity itself was not the main focus of the study. It is also limited by the fact that it was not possible to address other gender identities, such as trans and non-binary identities. Neither does it address social identities such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, or disability. Further research would benefit from a deeper intersectional approach incorporating a broader range of social identities.

This study reveals that after their college years, the on-going social experience of sexism is ever-present as a handicap that women in architecture must overcome and that at least some men in the profession also recognise that this sexism exists. There is a potential to overcome this sexism by recruiting these men to resist the practices and discourses that keep its force active. Moreover, there is a further opportunity in the fact that some male respondents also feel that there is a pressure to maintain an identity as “being architects” where no other interests or experiences are allowed to be expressed, yet we all have intersectional identities. Men and women in architecture, together, have the potential to recognise and resist social forces of sexism, classism, racism, and ableism which constrict those who practice the profession. However, this equality of opportunity in who might practice architecture does not necessarily entail that how architecture is practised will automatically change. The status quo of the profession is a masculinist, white, able-bodied, and middle-class version of “being architects” without responsibilities to any other concerns. In 1980, Dolores Hayden invited us to think about what a non-sexist city would be like (Hayden, 1980). We must now think seriously about what a non-sexist, intersectional architectural profession would be like (Hayden, 1980). We know that simply increasing the number of women architects alone will not be enough (Agudo Arroyo and Sánchez de Madariaga, 2011; Caven et al., 2022). The outcome that will be best for all architects is to reject the ‘ideal worker’ model and to value how a diversity of social experiences, perspectives, caring obligations to wider communities, and social reproduction might enrich architectural practice and the profession.

Data availability statement

The raw survey data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. The interview data is not currently available to protect the identities of the interviewees.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), UCD Office of Research Ethics. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization. KO’D: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research presented here was funded by the Irish Research Council with the Royal Institute of Architects of Ireland through an Enterprise Partnership Scheme Postdoctoral Fellowship (grant number EPSD/2022/10).

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank sincerely my mentor, Katherine O’Donnell, for her considered guidance and advice on this project. I also wish to thank Kathryn Megen and the RIAI for supporting this research. I am grateful to Paula Russell, Sara Honarmand Embrahimi, and Miriam Fitzpatrick for sharing their preliminary data collected in ‘Gender Equality in the Built Environment Professions in Ireland,’ an unpublished study. The authors also wish to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This refers primarily to the Anglosphere. In the English language, architect is a gender-neutral term; in gendered languages, however, there are often masculine and feminine forms; in Spanish and Italian, for example, arquitecta/arquitecto, architetta/architetto, respectively. Even where the term is gendered, a similar debate about the use of the feminine or masculine version can be found (see Pérez-Moreno, 2018).

2. ^See, for example, Ethel Charles, ‘A Plea for Women Practising Architecture’ (Charles, 1902).

3. ^We thank Reviewer 1 for their suggestion of this alternative interpretation.

4. ^Article 41.2.I: In particular, the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved. Article 41.2.2: The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.

5. ^Since 2007, ‘architect’ has been a protected title in Ireland, meaning that only architects who are registered with the Competent Authority for Architects, the RIAI, may use the title of ‘architect.’

6. ^In Northern Ireland, the Royal Society of Ulster Architects (RSUA) has a Women in Architecture Group. The Gender Equity in the Built Environment Professions conference was held in Dublin on 16 February 2024.

7. ^For those who had indicated that they had left the professional practice of architecture, a further section asked about the factors which contributed to the decision to leave.

8. ^The analysis of what is considered to be ‘working in architecture’ is not reported in this article but will be published on the Gender Equity in Irish Architecture website, https://genderequityirisharchitecture.ie/, in due course.

9. ^RIAI members, registered architects, must complete 40 CPD points annually in order to remain registered.

10. ^The survey asked, ‘What gender do you identify as?,’ with a choice of ‘male,’ ‘female,’ ‘transgender man,’ ‘transgender woman,’ ‘non-binary,’ and ‘other, please specify.’

11. ^The person who indicated that they are both ‘and architect working in professional practice,’ and ‘working in the broad field of architecture’ was asked during the interview to clarify their position, and on that basis, in the analysis, they are counted as ‘working in the broad field of architecture’ only.

12. ^The interviews began by asking the interviewees ‘how they got into architecture?’ and then about their first job and continued from there. This method encouraged the interviewees to think about the origins of their career, and they then tended to recount their career history chronologically with little further prompting.

13. ^Female-identifying respondents were asked, ‘How important is being a woman to the way you think about your career?,’ and male-identifying respondents were asked, ‘How important is being a man to the way you think about your career?’. Respondents who identified as transgender woman, transgender man, non-binary, or ‘other,’ were asked, ‘How important is your gender to the way you think about your career?’ This question was adapted from a question included in the European Social Survey (ESS), round 11 module on gender. In this survey, respondents who identified as ‘transgender woman,’ ‘transgender man,’ ‘non-binary,’ ‘other,’ or chose ‘prefer not to say,’ were asked, ‘How important is your gender to the way you think about your career?

14. ^‘Woman in architecture’ was preferred over ‘woman architect,’ as ‘women in architecture’ is more often used in the professional literature and professional and representative bodies. There has been resurgence of the use of the term after the MeToo movement around 2018, for example, the advocacy group Women in Architecture and the Women in Architecture Taskforce of the ACE (Architects’ Council of Europe) (ACE, 2023; WiA UK, 2018). ‘Women in Architecture’ tends to be used in context of promotion of highlighting the issues facing women architects, while ‘woman architect’ is a gender signifier added to a gender neutral term and is thereby more towards an identity.

15. ^This response was the inspiration for the title of this article. Of course, the gender neutrality of this phrase depends on the language; for discussion on this (see Pérez-Moreno, 2018).

16. ^Architectural Association of Ireland Awards are given annually.

17. ^Building or construction sites.

References

ACE (2023). ABC: gender balance, diversity & inclusion in architecture. Available at: https://www.ace-cae.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/ABC.pdf (Accessed June 20, 2024).

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: a theory of gendered organizations. Gend. Soc. 4, 139–158. doi: 10.1177/089124390004002002

Agudo Arroyo, Y., and Sánchez de Madariaga, I. (2011). Building a place in architecture: career path of Spanish women architects. Feminismos, 155–181. doi: 10.14198/fem.2011.17.08

Ahuja, S. (2023). Professional identity threats in interprofessional collaborations: a case of architects in professional service firms. J. Manag. Stud. 60, 428–453. doi: 10.1111/joms.12847

Ahuja, S., Heizmann, H., and Clegg, S. (2019). Emotions and identity work: emotions as discursive resources in the constitution of junior professionals’ identities. Hum. Relat. 72, 988–1009. doi: 10.1177/0018726718785719

Ahuja, S., Nikolova, N., and Clegg, S. (2017). Paradoxical identity: the changing nature of architectural work and its relation to architects’ identity. J. Professions Organ. 4, jow013–jow019. doi: 10.1093/jpo/jow013

ARB (2023). Architects today: analysis of the architects’ profession 2022. Available at: https://arb.org.uk/architects-today/ (Accessed August 2, 2023).

Bergen, N., and Labonté, R. (2020). “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 30, 783–792. doi: 10.1177/1049732319889354

Berger, P. L., and Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. New York: Open Road Integrated Media (Book, Whole).

Blau, J. R. (1984). Architects and firms: a sociological perspective on architectural practice. London, Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport, Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Brown, J. B., Harris, H., Morrow, R., and Soane, J. (2016). A gendered profession. London: RIBA Publishing.

Building Heroes (2024). Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/235b4-building-heroes/ (Accessed July 24, 2024).

Burns, K. (2012). The woman/architect distinction. Archit. Theory Rev. 17, 234–244. doi: 10.1080/13264826.2012.730537

Burns, K. L., Clark, J., and Willis, J. (2015). Mapping the (invisible) salaried woman architect: the Australian parlour research project. Foot 9, 143–160. doi: 10.7480/footprint.9.2.872

Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and gender constitution: an essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatr. J. 40, 519–531. doi: 10.2307/3207893

Caven, V. (2004). Constructing a career: women architects at work. Career Dev. Int. 9, 518–531. doi: 10.1108/13620430410550763

Caven, V. (2006). Career building: women and non-standard employment in architecture. Constr. Manag. Econ. 24, 457–464. doi: 10.1080/01446190600601354

Caven, V., and Navarro Astor, E. (2013). The potential for gender equality in architecture: an Anglo-Spanish comparison. Constr. Manag. Econ. 31, 874–882. doi: 10.1080/01446193.2013.766358

Caven, V., Navarro Astor, E., and Diop, M. (2012). A cross-National Study of accommodating and “Usurpatory” practices by women architects in the UK, Spain and France. Archit. Theory Rev. 17, 365–377. doi: 10.1080/13264826.2012.732588