- 1School of Sociology, Politics, and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

- 2Department of International Relations, Universitas Hasanuddin, Makassar, Indonesia

One of the lingering environmental issues faced in Southeast Asia is transboundary haze due to peatland fires. The issue is primarily evident in the Southern sub-region of ASEAN but affects the entirety of the Southeast Asian region. Recent spikes in haze since 2023 and ASEAN’s inability to adopt enforcing pronouncements and mediate the political ‘blame game’ between ASEAN member states lays the foundation for alternative approaches to curtail the environmental crisis. This empirical explanatory study utilizes primary and secondary data between 2014 and 2024 relevant to the political dynamics of haze pollution regulation in Southeast Asia. It is recommended that an ASEAN code of conduct be introduced to elevate the importance of transboundary haze regulations in Southeast Asia. A moderate level of its implementation grants ASEAN member states the freedom to determine the time period and form of domestic regulations to be practiced. In ensuring greater stakeholder accountability and participation, it is also recommended that ASEAN member states provide incentives for private entities adopting sustainable management practices of peatlands and sanction stakeholders who display non-compliance.

1 Introduction

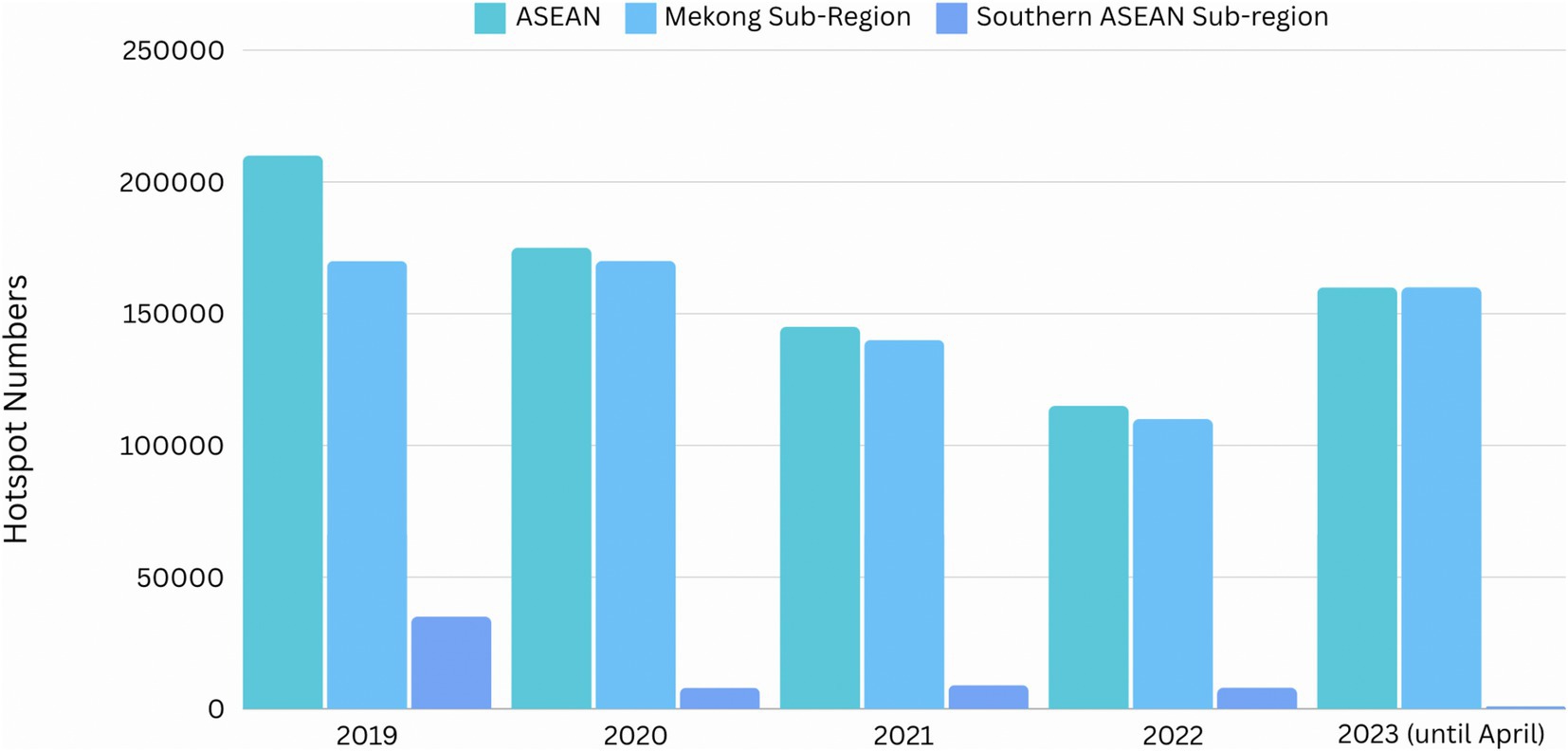

Transboundary haze has been a persistent periodical issue faced by the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The regional issue has primarily been caused by intensifying peatland fires since 1972, with Indonesia and Malaysia contributing most to the haze. Using slash-and-burn techniques in Southeast Asia for industrial plantation purposes has caused haze to spread within the national jurisdiction of ASEAN states, including Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. This is problematic as ASEAN hosts 56% of global tropical peatlands (ASEAN, 2024a). Despite regional efforts and a slowing down of severe transboundary haze due to the COVID-19 precautions, haze spiked again in 2023, reviving the importance of practical solutions to counter the problem (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hotspot numbers based on the Mekong sub-region (Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar) and Southern Sub-region (Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia) of Southeast Asia between 2019 and April 2023. Source: (Wangwongwatana, 2023).

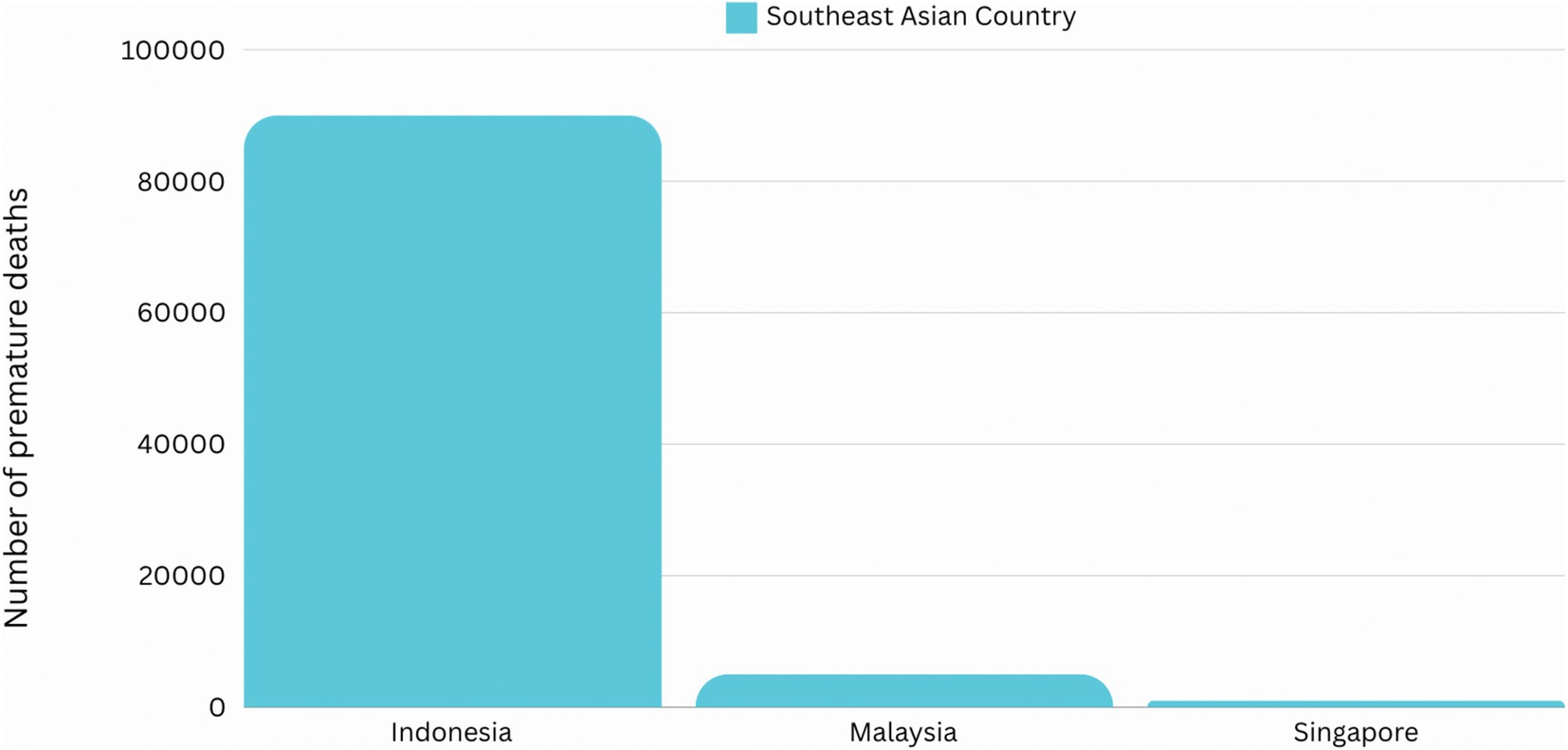

The implications of transboundary haze in Southeast Asia devastate the economy and the health of the civilians affected. Indonesia suffered USD 16 Billion from the haze between 2015 and 2019 (Greenpeace, 2019). During the historic 1997 and 1998 haze pollution, the region sustained USD 9 Billion in losses (ASEAN, 2024b). Transcending that, its impact on the air quality leads to significant health care problems for the Southeast Asian population. The series of recurring hazes have led to respiratory and dermatological issues due to the toxicity of the biomass particles emitted in hazes. In the 2015 haze, as seen in Figure 2, Southeast Asian countries suffered the most with the high number of premature deaths caused by the haze that originated from Indonesian forest fires (Varkkey, 2024).

Figure 2. Estimated number of premature deaths caused by the 2015 haze originating from forest fires in Indonesia. Source: Kiely et al. (2020); Koplitz et al. (2016).

This policy brief identifies that the recent spikes in haze since 2023 require alternative approaches. It delves into existing regional policies taken by ASEAN and outlines the ineffectiveness of existing ASEAN-based pronouncements in countering transboundary haze. Consequently, it will discuss how the policy recommendations of establishing an ASEAN code of conduct that elevates the importance of domestic transboundary haze regulations and providing incentives for the sustainable management of peatlands are commendable in countering the recent haze spikes. Furthermore, the recommended solutions can become a foundation of a practical regional approach to countering transboundary haze in Southeast Asia. This study utilizes a combination of primary data from Southeast Asian policymakers and ASEAN and secondary data related to haze pollution in the region in the past decade. It takes an empirical explanatory approach in order to catch the political dynamics of counter-haze pollution policies in Southeast Asia. This approach complements the vast list of methodologies adopted in the field of sustainable development over the years (Felegari et al., 2023; Gan et al., 2021; Marzvan et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023).

2 The problem with ASEAN’s approach

ASEAN has not been muted regarding countering the transboundary haze in Southeast Asia. After the devastating cases in 1997 and 1998, ASEAN has consistently responded through the 1997 Regional Haze Action Plan (RHAP) and the 2002 ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze (AATHP) (ASEAN, 2023a). Actions have focused on monitoring, prevention, and mitigation as decisive regional responses. To better coordinate regional responses, ASEAN established the ‘Roadmap on ASEAN Cooperation towards Transboundary Haze Pollution Control with Means of Implementation’ in 2016 and implemented until 2023 (ASEAN, 2024b). A second roadmap, implemented between 2023 and 2030, focuses on enhancing regional measures to counter transboundary haze, sustainable management practices, securing resources, development of policies, as well as cross-sectional cooperation (ASEAN, 2024a). However, the decades-long Southeast Asian haze has not been able to be curtailed effectively despite the abundance of regional mechanisms.

Two issues are identified in this policy brief. First, existing regional mechanisms currently fail to curtail the transboundary haze in Southeast Asia due to ASEAN’s lack of capacity to enforce measures. Furthermore, ASEAN cannot mediate bilateral tensions between considerable ASEAN member states, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, which have been blaming one another for decades (Wangwongwatana, 2023). Existing measures also fail to respond to the lingering intra-ASEAN problem of ASEAN member states’ inability to enforce laws effectively and adopt policies that prosecute those responsible for peatland fires in the region. Of all the ASEAN members, only Singapore has adopted a domestic transboundary haze law. Meanwhile, for Indonesia, known to be the most significant contributor to haze in the region, its 2009 Forestry Law, which imprisons those who intentionally commit fires, has not been enforced effectively (Mai, 2023). Consequently, the following question arises: How can ASEAN overcome the political hurdles of adopting an effective haze-countering solution?

3 Recommendation 1: establish an ASEAN code of conduct that elevates the importance of domestic transboundary haze regulations in Southeast Asia

In the current status quo, having a domestic transboundary haze regulation is merely pronounced by ASEAN, not enforced. This recommendation elevates the urgency of countering transboundary haze in the region by establishing a code of conduct that must be adhered to by member states upon ratification. As for the current status quo, Southeast Asian states adopt diverse forms of domestic regulations to prevent transboundary haze. Considering the unique setting of ASEAN and the importance of respecting sovereignty, a single policy recommendation will not be imposed in the code of conduct. All member states reserve the freedom to adopt a domestic transboundary haze regulation that suits that nation’s political and regulatory landscape. Only Singapore currently criminalizes stakeholders that contribute to the haze. Meanwhile, other ASEAN member states do not have the legal foundations to adopt a similar course of action, such as that adopted in Singapore.

Adopting a code of conduct that enforces the need to implement a domestic transboundary haze regulation allows enough room for ASEAN member states to decide upon a regulation that suits the state and does not impede the state’s development ambitions. As for the current status quo, the vast regional mechanisms within ASEAN have acknowledged the importance of identifying challenges related to both the public and private sectors (ASEAN, 2023b, 2024c). Adopting action plans also helps provide ASEAN member states with the necessary knowledge of how to advance effective measures at the national level. In the past, the intention of states to resolve the South China Sea conflict through the adoption of a code of conduct of parties has immensely increased the agenda of maritime security within the ASEAN Summit and dialogues with its external partners (Buszynski, 2003; Hu, 2021; Mishra, 2017; Odgaard, 2003; Putra, 2023; Shoji, 2012). Elevating the importance of countering haze pollution through a code of conduct would help expose more of ASEAN’s vulnerabilities and inject a sense of urgency to resolve them.

However, an essential implication of a code of conduct is its alignment with the ‘ASEAN Way’ and the current ASEAN roadmap to counter transboundary haze pollution. One issue faced by ASEAN and its pronouncements in countering haze in the region is that it must adhere to the ASEAN values to respect sovereignty, non-interference, and non-intervention. Consequently, it has been difficult for the organization to impose an ideal set of regulations that ASEAN member states must adhere to. By adopting a code of conduct, existing agreements of RHAP and AATHP are elevated in importance by tackling the most critical contributor to passive regional action of countering haze in the region: the lack of relevant national policies. In doing so, it also refrains from ‘pointing the finger’ towards the significant contributor of transboundary haze in Southeast Asia, Indonesia. It emphasizes collective regional efforts to counter the regional problem. Furthermore, it aligns with the ASEAN’s second roadmap on transboundary haze pollution control point 6: strengthening relevant national policies, laws, regulations, and their implementation. Consequently, this provides a more coherent response to the lack of legal frameworks evident within Southeast Asian states.

4 Recommendation 2: incentives for the sustainable management of peatlands

As the primary contributor to transboundary haze in Southeast Asia, adopting measures that allow the clearance of land without burning is essential. With the recent haze spikes in the region, particular focus is needed on the private entities within a state that may be involved in environmentally hazardous land clearance practices (ASEAN, 2024c). This recommendation incentivizes entities that adopt sustainable management of peatlands by refraining from taking environmentally harming alternatives to clearing lands. In conjunction with this, ASEAN must adopt sanctions for companies that do not comply with such measures, which government stakeholders must adopt. In regard to the specific measures that constitute sustainable environmental practices, this right will remain within the hands of each government.

The impacts can be striking. As for the current status quo, as can be seen in Figure 1, illegal land clearing through burning has contributed immensely to the spike in haze in recent years (ASEAN, 2024b). Unfortunately, this has been a phenomenon that has been occurring for each decade, with a similar instance being noted due to private entities’ lack of good faith in Southeast Asia (Greenpeace, 2019, 2023). This policy allows for the tackling of the problem at its roots, primarily focusing on the main contributor of transboundary haze in Southeast Asia. Through this systematic response, government stakeholders will be made more accountable for providing positive incentives so that private stakeholders will refrain from harmful actions to the environment. The involvement of private entities in ASEAN’s past struggles with transnational crimes such as terrorism, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and human trafficking, were pivotal in ASEAN’s success in curtailing those non-traditional security threats (Darwis and Putra, 2022; Emmers, 2009; Juned et al., 2019; Snitwongse, 2007; Putra, 2020). Acknowledging the impact that private entities can establish and focusing on measures on how they can contribute allows for a more nuanced and collective approach within domestic borders.

Another implication is its alignment with the ASEAN’s second transboundary haze pollution control roadmap. To be adopted and achieved before 2030, the second roadmap outlined the importance of enhancing public awareness and stakeholder participation in resolving transboundary haze in the region. Unfortunately, not much thought is invested in private entities in the decades-long ‘blame game’ in Southeast Asia’s haze problem. The spotlight has primarily been on the lack of national laws or enforcement of such laws within a state’s domestic borders. Meanwhile, large corporations have enjoyed immunity over their destructive actions. This recommendation provides a way out of this dilemma by allowing Southeast Asian governments to decide what measures are included as sustainable management practices, provide incentives for compliance, and sanction instances of non-compliance.

5 Actionable recommendation: a moderate-level solution?

At the normative level, both recommendations are needed. However, consideration must be given to the unique political landscape of ASEAN. ASEAN is not a supranational regional organization that has the capacity to enforce laws and regulations towards its members. Adopting new norms, regulations, and frameworks in ASEAN requires peaceful negotiation, consensus, and dialogue, with the proposed provisions ensuring respect for sovereignty and non-interference. Consequently, the only problem with the recommended solutions is not related to their substantive but to how moderate or severe the new provisions will be.

This policy brief argues that both recommendations can be adopted at a moderate level. First, a new code of conduct is essential to elevate the existing agreements that counter transboundary haze pollution in Southeast Asia. However, the wording must ensure that if the code of conduct pronounces the importance of ASEAN member states adopting domestic transboundary haze regulations, it must grant flexibility to its members. This means that the time period of adopting a new legal framework and forms of domestic law (criminalization, prosecution, fines, etc.) must not be strict towards a single time period of implementation or regulatory form. This allows greater flexibility for ASEAN member states to determine the proper course of action based on their unique political landscape. This also allows the three primary conflicting ASEAN member states, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia, to sideline their past ‘blame game’ and focus on engaging in a regional collective resolution to the crisis. An agreed document in the form of a code of conduct is essential for the first recommendation to succeed to show decisiveness in resolving the decades-long crisis. Second, incentives for the sustainable management of peatlands are also justified to be adopted at a moderate level. This means that the forms and timeline of the incentives given and the definition of sustainable management of peatlands should be reserved for the state policymakers to determine.

6 Conclusion

Recent spikes in haze since 2023 in Southeast Asia require a different approach. As a persistent periodical issue faced by ASEAN member states, existing regional policies have effectively curtailed the issue. Not only is ASEAN lacking the capacity to enforce measures, but it also suffers from the lingering intra-ASEAN issue of members’ inability to enforce laws that prosecute those responsible for conducting fires in peatlands. As the conduct of slash and burn techniques for plantation purposes continues in Southeast Asia, the issue of transboundary haze continues to cause health and dermatological concerns due to the toxicity of the biomass particles in hazes.

This policy brief identifies two recommendations to counter this issue. First, there is a need to establish an ASEAN code of conduct that elevates the importance of domestic transboundary haze regulations in Southeast Asia. ASEAN’s past agreements related to haze control, the RHAP and AATHP, both suffer from the inconsistent domestic laws present within the domestic borders of ASEAN member states. Such response inconsistencies require forming a national regulation or law that allows ASEAN member states to determine how they would prosecute or criminalize perpetrators of haze pollution within a state’s boundaries. Adopting a code of conduct allows all member states to determine how severe prosecutions should be, aligning it with ASEAN’s principles of respect over sovereignty and non-interference. Furthermore, tackling the root of the problem requires a solution targeted to the private entities, which often adopt unsustainable peatland management. This policy brief recommends the provision of incentives for entities that showcase sustainable measures, refraining from burning practices to clear lands. It is also advised that sanctions be adopted for those not complying with the provisions to strengthen further the image of ASEAN’s decisiveness in countering Southeast Asia’s transboundary hazes.

The main limitation of this policy brief relates to the evolving national political dynamics of Southeast Asian states. With the evolving political climate and constant changes to governance, it is difficult to measure a state’s adherence towards regional collaboration efforts in countering haze pollution. This, perhaps, can be an essential agenda for future research.

Author contributions

BP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ASEAN. (2023b). Media release twenty-fourth meeting of the sub-regional ministerial steering committee on transboundary haze pollution.

ASEAN. (2024a). Haze. Available at: https://asean.org/our-communities/asean-socio-cultural-community/haze-2/ (Accessed February 12, 2024).

ASEAN. (2024b). Haze – Overview. Available at: https://asean.org/our-communities/asean-socio-cultural-community/haze-2/ (Accessed February 12, 2024).

ASEAN. (2024c). Launch of the second ASEAN haze-free roadmap (2023-2030) and policy dialogue on strategies and actions for achieving a haze-free Southeast Asia. ASEAN Haze Portal. Available at: https://hazeportal.asean.org/2024/02/28/launch-of-the-second-asean-haze-free-roadmap-2023-2030-and-policy-dialogue-on-strategies-and-actions-for-achieving-a-haze-free-southeast-asia/ (Accessed February 12, 2024).

Buszynski, L. (2003). ASEAN, the declaration on conduct, and the South China Sea. Contemp. Southeast Asia 25, 343–362. doi: 10.1355/CS25-3A

DarwisPutra, B. A. (2022). Construing Indonesia’s maritime diplomatic strategies against Vietnam’s illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing in the north Natuna Sea. Asian Aff. Am. Rev. 49, 172–192. doi: 10.1080/00927678.2022.2089524

Emmers, R. (2009). Comprehensive security and resilience in Southeast Asia: ASEAN’s approach to terrorism. Pac. Rev. 22, 159–177. doi: 10.1080/09512740902815300

Felegari, S., Sharifi, A., Khosravi, M., and Sabanov, S. (2023). Using experimental models and multitemporal Landsat-9 images for cadmium concentration mapping. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 20, 1–4. doi: 10.1109/LGRS.2023.3291019

Gan, T., Yang, H., and Liang, W. (2021). How do urban haze pollution and economic development affect each other? Empirical evidence from 287 Chinese cities during 2000–2016. Sustain. Cities Soc. 65:102642. doi: 10.1016/J.SCS.2020.102642

Greenpeace. (2023). Renewed calls for ASEAN to prioritise and protect citizens’ rights to clean air from transboundary haze. Greenpeace Southeast Asia. Available at: https://www.greenpeace.org/southeastasia/press/62845/calls-for-asean-to-prioritise-and-protectcitizens-rights-to-clean-air-from-transboundary-haze/ (Accessed February 16, 2024).

Greenpeace. (2019). ASEAN HAZE 2019: THE BATTLE OF LIABILITY. Greenpeace Southeast Asia. Available at: https://www.greenpeace.org/southeastasia/press/3221/asean-haze-2019-the-battle-of-liability/ (Accessed February 16, 2024).

Hu, L. (2021). Examining ASEAN’s effectiveness in managing South China Sea disputes. Pac. Rev. 36, 119–147. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2021.1934519

Juned, M., Samhudi, G. R., and Lasim, R. A. (2019). The impact Indonesia’s sinking of illegal fishing ships on major Southeast Asia countries. Int. J. Multicult. Multirelig. Underst. 6:62. doi: 10.18415/ijmmu.v6i2.673

Kiely, L., Spracklen, D. V., Wiedinmyer, C., Conibear, L., Reddington, C. L., Arnold, S. R., et al. (2020). Air quality and health impacts of vegetation and peat fires in equatorial Asia during 2004–2015. Environ. Res. Lett. 15:094054. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/AB9A6C

Koplitz, S. N., Mickley, L. J., Marlier, M. E., Buonocore, J. J., Kim, P. S., Liu, T., et al. (2016). Public health impacts of the severe haze in equatorial Asia in September–October 2015: demonstration of a new framework for informing fire management strategies to reduce downwind smoke exposure. Environ. Res. Lett. 11:094023. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/11/9/094023

Mai, L. (2023). Extinguishing a Point of Contention: Examining Transboundary Haze in Southeast Asia. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2023/11/extinguishing-a-point-of-contention-examining-transboundary-haze-in-southeast-asia/ (Accessed February 13, 2024).

Marzvan, S., Moravej, K., Felegari, S., Sharifi, A., and Askari, M. S. (2021). Risk assessment of alien Azolla filiculoides lam in Anzali lagoon using remote sensing imagery. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 49, 1801–1809. doi: 10.1007/s12524-021-01362-1

Mishra, R. (2017). Code of conduct in the South China Sea: more discord than accord. Marit. Aff. 13, 62–75. doi: 10.1080/09733159.2017.1412098

Odgaard, L. (2003). The South China Sea: ASEAN’s security concerns about China. Secur. Dialogue 34, 11–24. doi: 10.1177/09670106030341003

Putra, B. A. (2020). Extending the discourse of environmental securitization: Indonesia’s securitization of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and China’s belligerence at sea. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 575:012242. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/575/1/012242

Putra, B. A. (2023). Deciphering the maritime diplomatic properties of Malaysia’s oil and gas explorations in the South China Sea. Front. Polit. Sci. 5, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1286577

Shoji, T. (2012). Vietnam, ASEAN, and the South China Sea: Unity or diverseness? NIDS J. Def. Secur. 14. Available at: http://faculty.law

Snitwongse, K. (2007). ASEAN’s security cooperation: searching for a regional order. Pac. Rev. 8, 518–530. doi: 10.1080/09512749508719154

Varkkey, H. (2024). Borderless Haze Threatens Southeast Asia. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2024/01/borderless-haze-threatens-southeast-asia/ (Accessed February 13, 2024).

Wang, X., Su, Z., and Mao, J. (2023). How does haze pollution affect green technology innovation? A tale of the government economic and environmental target constraints. J. Environ. Manag. 334:117473. doi: 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2023.117473

Wangwongwatana, S. (2023). Tackling Transboundary Haze Pollution in Southeast Asia. SLOCAT Partnership. Available at: https://slocat.net/tackling-transboundary-haze-pollution-in-southeast-asia/ (Accessed February 13, 2024).

Zhang, M., Tan, S., Pan, Z., Hao, D., Zhang, X., and Chen, Z. (2022). The spatial spillover effect and nonlinear relationship analysis between land resource misallocation and environmental pollution: evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 321:115873. doi: 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2022.115873

Keywords: haze pollution, Southeast Asia, ASEAN, sustainability, environmental policy

Citation: Putra BA (2025) The politics of environmental policy: haze pollution, ASEAN, and the way forward. Front. Sustain. Cities. 6:1417746. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1417746

Edited by:

James Evans, The University of Manchester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Alireza Sharifi, Shahid Beheshti University, IranMaomao Zhang, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Putra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bama Andika Putra, YmFtYS5wdXRyYUBicmlzdG9sLmFjLnVr

Bama Andika Putra

Bama Andika Putra