- Planning Policy Lab, Technion, Faculty of Architecture & Town Planning, Technion Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel

In the age of technological acceleration, new digital shifts and the increased use of ICT have changed the ways we work, live, sleep, and shop. Remarkable transformations have left footprints in the planning world as well, with many urban planners harnessing technology to improve and expedite planning processes. This process accelerated further during the COVID pandemic, which forced many planning committees and local governments to conduct public meetings, hearings, and participatory processes remotely in order to allow the planning machine to continue rolling while abiding by social distancing rules. Developments such as this have been part of a broader shift toward the increasing reliance of planning on video-conferencing and other technological innovations. While this new policy has proved advantageous to many, it has also had regressive impacts and severely affected social inclusion in the planning process. This paper reviews these outcomes by focusing on the Israeli planning system post-COVID, which continues to embrace videoconferencing as a tool in planning. The findings illustrate the vulnerability of certain groups to the accelerated digitalization of urban planning. Despite planners’ awareness of these outcomes and adaptations made to existing means of e-participation, online planning meetings are not geared toward using tools and platforms to improve practice; instead, remote participation remains largely a ‘pro-developers’ process and could marginalize other participants.

1 Introduction

Digital transformations are currently accelerating in all aspects of life. In what Thomas Fridman dubbed “the age of acceleration,” people experience rapid changes that affect the way they live, work, and even sleep (Friedman, 2016). In the age of acceleration, the only constant is rapid change. Public administrators are faced with new technology that changes how government functions and the way it carries out its daily tasks; examples range from blockchain which is employed to manage real estate (Saari et al., 2022), to AI which is increasingly used to help public officials reach strategic decisions about land (Sanchez et al., 2023). Smartphone apps, drones, and big data all help decision-makers gather ever-larger amounts of information and reach greater numbers of constituents (Xiang, 2018).

Where urban planners are concerned, technology has been employed at an accelerated pace to facilitate data-collection, public participation, and resource management (Yigitcanlar et al., 2020). However, these changes are also disrupting the ability of some stakeholders to influence planning initiatives. Inclusion and transparency of planning processes may be reinforced and promoted using technological innovations (Guimarães Pereira et al., 2003), but the digital revolution has also manifested in regressive and non-inclusionary practices in cities (Ash et al., 2018). For example, a US study found that online information provided to future buyers and renters on different technological platforms might not serve as information equalizers, and eventually result in inequalities “by supplying significantly different volumes, quality, and types of information in different communities” (Boeing et al., 2021). While technological platforms can broaden and diversify participatory processes, some do not achieve this goal and instead neglect issues of trust and transparency (Santamaria-Philco et al., 2019).

This paper explores the aforementioned digital transformations in relation to public hearings and meetings held by Israeli planning authorities. We review how these changes have had a longstanding impact on the way in which urban planners carry about their daily activities, and how this has affected certain communities. By looking at post-Covid changes, we explore how participatory processes have been modified to serve the interests of elites and institutional planning, while sidelining marginalized populations. By looking at shifts that occurred in Israeli public hearings before planning tribunals and committees, we highlight emerging ethical questions about the effects of the technological acceleration on inclusionary planning, fairness, and civic participation.

2 Acceleration, technology, and trust during and post COVID

Amidst increased infringements of private rights and interventions by public authorities, the COVID-19 pandemic left many communities and individuals worldwide distrustful of their governments (Dobrić Jambrović, 2022; Lozano-Uvario and Rosales-Ortega, 2022). Public administrators were caught unprepared to deal with the spread of the virus. Many citizens felt abandoned and exposed. Families lost their livelihoods, and the consequences of an economic meltdown were (and still are) looming over many cities around the globe (Matamanda et al., 2022). While cracks in relationships between elected officials and their constituents emerged, governments were called upon to adopt digital instruments that would enable them to provide services and to govern in the shadow of the pandemic’s challenges and constraints. Accelerated adoption of e-participation and ICT technologies by municipalities were seen as an opportunity (Bouregh, 2022) for making governance more accessible and inclusive. However, this added to the already-emerging crisis of trust between governments and citizens. Communities and individuals who were already struggling psychologically and economically were now expected to move their lives online, replacing in-person interactions overnight. In the world of urban planning, this meant communicating with planners and elected officials now had to be done remotely. Fragile trust between governments and citizens was already on shaky ground (Cairney and Wellstead, 2021), and this sudden shift only added to the challenge by creating a digital ‘screen’ between the planners and the ‘planned-for’.

Consequently, the COVID-19 experience provided (and still provides) a glimpse into a new paradigm – one in which planners can devise meaningful inclusionary processes (Potts, 2020) or, alternatively, accentuate existing rifts and practices that fray public trust (Ormerod and Davoudi, 2021). Nowhere is this more pronounced than in the field of online public hearings and remote planning meetings. These hold transformative powers in the way that they encourage more people to participate and allow for the saving of time and resources; at the same time, however, they may also increase distrust and further entrench existing power imbalances by disenfranchising certain communities (Steuteville, 2021). This serves as a reminder that the danger exists that some governments may utilize the shifts brought about by the pandemic as a strategic opportunity to trample those without political, economic or social clout.

3 Participatory processes in planning following the pandemic

Public participation has been a thorny issue from the early days of modern urban planning (Arnstein, 1969; Brooks, 2002). The challenge of including all stakeholders and bringing all those involved to the table (Fung, 2015) has proved to be an almost insurmountable one, with critics noting that public meetings held by planning authorities do not necessarily engage with the public, nor create sufficient representation (Bedford et al., 2002) or desired outcomes (Brown and Chin, 2013). Although there have been successful instances of face-to-face engagements, public participation – even before COVID and the age of digital accelerations – has proven quite difficult to achieve (Marcuse, 2011). In essence, it is an almost idealistic process that is very ambitious and costly to secure (Sandercock, 2003).

Before the advent of the pandemic, critical planning studies pointed out the inherent power imbalances that make public participation serve the powerful elites, in practice encouraging the “haves” rather than the “have-nots” to participate in planning initiatives. These accounts provided ample evidence about participation as nothing more than a sham (Haughton and McManus, 2019). In effect, planning is an instrument intended to blind the masses, making them think they have the ability to actually change the course of planning and the environment around them, but in reality, planning has been co-opted by political interests to contain the dissent of urban denizens (Legacy, 2017, p. 426). In reality, quite a few studies have found that public engagements are crafted to serve the existing socio-economic structures in society (Laskey and Nicholls, 2019), and have become a tool wielded by power-rich and power-hungry individuals and authorities without having meaningful impact on the lives of people, the general public interest, nor the quality of planning. All of these perspectives pre-date the transition to using remote meeting technologies, which strongly suggests that ICT tools are merely reinforcing existing patterns of inequalities rather than causing them.

In search of a panacea, prior to the pandemic, several scholars pointed out the ability of ICT and e-participation to help planners engage with the public, identify relevant communities, or at least aid them in creating new platforms to share and receive information (Saad-Sulonen and Horelli, 2010). For instance, Evans-Cowley and Hollander (2010) provide evidence on the efficacy of online social networks which can aid planners as part of broader participatory processes. Likewise, Conroy and Gordon (2004) find that a group that attended a meeting in a technology-based setting was more satisfied and felt more empowered relative to a group that attended a traditional in-person meeting. The power of ICT has also been acknowledged by planners who successfully employed digital wearables (Wilson et al., 2019) and crowdsourcing to address specific problems and ‘pick the brains’ of the masses (Seltzer and Mahmoudi, 2013). Online forums and other ICT tools were found to be highly effective in informing citizens (Mukhtarov et al., 2018). Where videoconferencing is concerned, even prior to the pandemic planning scholars (Li et al., 2020) and educators (Giesbers et al., 2009) were already giving much thought on how to devise successful remote meetings. Scholarly publications documented cases in which facilitators managed to spur quality discussions through videoconference and chat meetings (Li et al., 2020).

Following the pandemic, some scholars spotted a golden opportunity that emerged to study the real-life experiment that was remote planning meetings taking place under new conditions. Several scholarly contributions began to collect data and found that as a form of participation, online remote hearings and meetings with the public have created new opportunities for meaningful and inclusive processes (Bourdakis and Deffner, 2010; Robinson et al., 2023). Some even achieved impressive results in terms of encouraging deliberations. Indeed, one could expect that a reduction of barriers to participation can help the public engage in decision making (Norris, 2000). Planners as well as others participating in online meetings reported high levels of satisfaction in many jurisdictions around the world (Bouregh, 2022; Mualam et al., 2022). Remote meetings were associated with efficiency and a much-needed evolution of the planning system (Milz and Gervich, 2021).

An American study based on in-depth interviews found that planners were able to adjust relatively quickly to online meetings, while improving dialogue between planners and remote participants, and breaking longer meetings to avoid the physically-taxing aspects of online processes (Milz et al., 2023). Planners promoted successful synchronous and asynchronous meetings and strived to adopt participation-centered processes that made informal interactions possible (Ibid).

Several scholarly contributors suggest a way forward after COVID, facilitating digital acceleration and well-informed public participation (Bartlett, 2020; Kim, 2020). Some scholars find that although online meetings are deficient, in some circumstances they can still become a tool of empowerment. Radtke (2023) observes that it is essential to blend online and offline formats of e-participation in order to maximize engagement (for example, facilitating hybrid video meetings). As well, it has been suggested that IT infrastructures and technological tools should be frequently updated to streamline online participation (Radtke, 2023). An American study based on experts’ interviews gleans some important lessons as well: suggesting ways forward (Iroz-Elardo et al., 2021) note that e-participation can be improved by hiring professional facilitators who are able to manage multi-stakeholder meetings; by providing clear instructions to participants in online meetings; by maintaining public engagement in e-meetings; and by allowing facilitators of discussions to assume an active role. As well, public officials should constantly reach out to those populations who might be under-represented (Iroz-Elardo et al., 2021). The latter can be achieved by supplementing digital participation with traditional means of participation, namely reaching communities outside of online engagement by spending more funds on emailing the informational materials, informing them through local newspapers and media, or by blending online and in-person opportunities to engage with decision-making opportunities (Ibid, p. 28–29). Likewise, Chassin (2022) notes that facilitators of e-planning processes must acknowledge that the choice of a certain participation medium “will exclude some part of the population, therefore, this approach should be completed by other participatory sessions” (Chassin, 2022, p. 224).

Hampton et al. (2017) observe that “modest changes in our behaviors, communication techniques, and use of technology can vastly improve virtual participation and help to create more positive experiences for virtual and in- person participants” (p. 59). This can be achieved by minimizing poor communication and making the online meetings as engaging as possible. Hampton et al. (2017) also advise on how to overcome technological hiccups, creating virtual places for note-taking, allowing pauses to solicit inputs from the public, and establishing trust by engaging with the public in face-to-face meetings before virtual engagements.

Other recommendations include understanding in advance the goals of participation, topics discussed, the scale of the topic, and the ability to identify the most relevant communities (Odendaal, 2010). These contextual matters help planners select the appropriate medium during the design of a participatory approach (Chassin, 2022). This means, for example, that when planners discuss plans that relate to disenfranchised groups, or plans in areas characterized by an elderly demographic, they might wish to reconsider the mode of participation, and not rely solely (if at all) on remote meetings.

At the same time, online meetings handled by public authorities during the pandemic came under fire by policy analysts and experts for creating unequal conditions for participation, which resulted in the stifling of dissent through digital means (Pokharel et al., 2022) and keeping the existing power relations intact (Schwartz-Ziv, 2021). Milz et al. (2023) found that despite notable advantages, planners were also struggling to support group interactions during online meetings; they found it harder to read body-language, and mostly fit their face-to-face practices to online hearings, without making use of technology to craft innovative engagements that utilize technological leaps to make crucial advances in participatory processes (Ibid).

Einstein et al. (2023) reported that instead of seizing the opportunity provided by digital acceleration, many public authorities instead squandered the chance to better represent their constituents so that following COVID-19, online forums remain unrepresentative of their broader communities, and representation has not improved relative to face-to-face meetings (Einstein et al., 2023). Likewise, Radtke observed that digital participation post COVID “has failed to match the quality of real-world procedures” (Radtke, 2023). This is allegedly because face-to-face interactions are more personable, increase trust, and contribute to better discussions (Ibid). Chassin (2022) offers another explanation, noting that technological platforms used following COVID have failed because they “tried to mimic in-person sessions, which by nature cannot work” (p. 230).

These accounts, as well as others (Odendaal, 2010; Mukhtarov et al., 2018), forewarn against the regressive impacts of e-planning and ICT before and following the pandemic. Chassin (2022) observes a notable technological divide that creates numerous obstacles for participation. The most notable obstacle is the inability to bridge the age-gap, as elderly populations struggle more with online planning instruments. This is observable in employing 3D participatory tools (Chassin, 2022), as well as in ‘ordinary’ online hearings, or even when utilizing other tools that incorporate ICT in planning (Li et al., 2020). Other influential factors relate to income and education, both associated with digital literacy and willingness to use technological tools in participatory planning processes (Ibid). In a similar vein, although a comprehensive study of professionals from around the world attested to the importance of online meetings as a viable alternative to face-to-face interactions, 45% of responses described a fear of excluding those with limited digital access or ability, or otherwise a decreased quality of interpersonal interactions. And “although respondents generally perceived virtual meetings to be more accessible, only a small number reported that digital collaboration and engagement activities had resulted in greater rates of participation” (Daniel et al., 2023, p. 13). The challenges do not stop there, as shown by Mualam et al. (2022), who observed that online hearings in planning impair spontaneity and interactions among participants, decreases participants’ ability to express themselves, and empowers dominant groups of individuals at the expense of less dominant ones.

From a radical point of view, these findings run contrary to the often-cited maxim that digitalization will emancipate planning from its inherent failure to increase participation (Daniel et al., 2023). These critical views also tie COVID and the crises it created to opportunistic government practices that use shock (Klein, 2008; McGee, 2023) to create vestiges of privilege while entrenching patterns of exclusion (Odendaal, 2010). By creating selective and partial e-participation platforms, these new transformations led by planners and government officials amount to ‘token participation’ (Evans-Cowley and Hollander, 2010). In essence, the authorities adopted technologies that are quick, simple, and easy to implement, but overlooked their underlying dimensions of exclusion. Consequently, ICT during and post-COVID, and its use without care for citizen’s inclusiveness, might be exploited “as a legitimizing tool for the local self-government” (Pánek et al., 2022). These perceptions are in line with scholarly contributions showing that even before the pandemic, public participation has largely been a mirage, an unachievable ideal designed to blind the masses to the real power imbalances embedded in society (Huxley and Yiftachel, 2000; Bouchard, 2016). These critiques accuse progressive planners of optimism; of singing ‘kumbaya’ around the planning table, while planning prevents people from making significant changes in the urban environs, and participatory processes are crafted to minimize opposition or ignore community feedback (Easton, 2013). In the age of acceleration and ICT, these traits are perhaps magnified by the ability of technology to create a façade of fairness, professionalism, and inclusiveness.

4 Note on context, data, and methods

4.1 Context: Israel’s planning system

The following analysis focuses on online planning meetings held by planning committees in Israel post-COVID. As the pandemic spread, legislators decided to introduce new emergency regulations that facilitated a rapid move to online hearings, meetings, and other consultations (Shahak, 2020). It meant that the approval of statutory plans, strategic documents, planning permissions, day-to-day meetings with various stakeholders, and much more, all rapidly moved online. Participatory processes, stakeholder consultations, as well as more litigious and adversary processes (such as planning appeals) were all handled online as the virus spread. The crisis was considered by national planners as a significant opportunity to remodel planning, to introduce technological innovations, and to improve resilience via planning (Planning Administration, 2020). This shift was not unique to Israel, and was apparent across the world (Thomas, 2020; Daniel et al., 2023). As such, the Israeli example is quite illustrative of similar processes happening elsewhere and may be of relevance to planners still struggling with online hearings. Additionally, even as the pandemic wound down, Israeli planners continued to utilize this tool in their daily work, with planning meetings still being held online as of 2024. Although this is now done to a lesser degree, planning commissions can still decide whether to conduct certain meetings online; in some planning authorities, as much as 50% of discussions are still held online (Personal Communication with N.S, planning expert, February 2024).

As in other advanced-economy systems (Presthus, 1951; Yung and Chan, 2011; Fung, 2015), the Israeli public is consulted and actively participates in planning initiatives (Alterman and Carmon, 2011) on a few occasions: as objectors to statutory planning, when lodging appeals and complaints (Mualam, 2014), or when consulted voluntarily by planning officials. In addition, the Israeli public may become involved in strategic planning initiatives promoted by local, regional, or national planning committees.

4.2 Data and methods

Our ensuing insights are predicated on a thorough survey of over 180 participants in planning hearings that took place online following the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey was exploratory in nature, designed to probe participants’ experiences and perceptions of online planning meetings. We used SurveyMonkey software to disseminate the questionnaire from July to October 2020. During this period, the pandemic was still active, making it impossible for planning boards to hold face-to-face meetings. The respondents included practitioners, decision-makers, and other stakeholders who attended planning board meetings. Using a non-probability sample, we circulated the questionnaire through a snowball sampling strategy that included personal contacts as well as random distribution over a variety of social media platforms (LinkedIn and Facebook). This strategy has proven beneficial when it is difficult to access a research population, as it was in the early phases of the COVID pandemic. While policy studies support this form of dissemination, it nevertheless suffers from various disadvantages, including the difficulty of following up with non-responders.

The survey form included the opportunity for respondents to add their insights and comments in open-ended (non-directive) feedback text boxes, allowing survey participants to “vent” their feelings about online planning meetings. The outputs of survey data were summarized and anonymized. Qualitative data (such as personal notes by survey respondents and their non-numerical observations) were ordered in Excel sheets and underwent basic coding to identify emerging themes. This inductive and thematic analysis identified key issues and ideas that were more prevalent in the respondents’ texts. Among other things, we identified a coding frame (Decorte et al., 2019) featuring several major themes: the impact on disadvantaged groups, the type of affected groups/communities, advantages versus drawbacks of Zoom meetings in planning, and the developer’s view vis-à-vis other (more critical) perspectives on online hearings. Additional respondents’ comments touched on several other codified categories, including: recommendations based on personal experiences; comments about the suitability of online meetings to particular types of engagements; and observations offered by respondents on the differences between online and in-person meetings.

The survey results mapped both advantages and disadvantages of using videoconferencing in planning meetings; their key findings have been partially explored elsewhere (Mualam et al., 2022). Overall, survey respondents who participated in online planning hearings, meetings, and other consultations viewed videoconferencing as essential to participation in planning, even more so during COVID. Participants were of the view that online planning is quite essential post-pandemic as well, as it is associated with increased efficiency and effective planning (Ibid). However, respondents flag major caveats including technological hurdles, as well as psychological and physiological barriers to conducting online planning meetings. They also noted the exclusionary impacts of online meetings, which are explored herewith in the ensuing sections. Our survey respondents were also asked to reflect on the videoconferencing from a personal perspective. This allowed us to glean normative and overarching perspectives provided by informants.

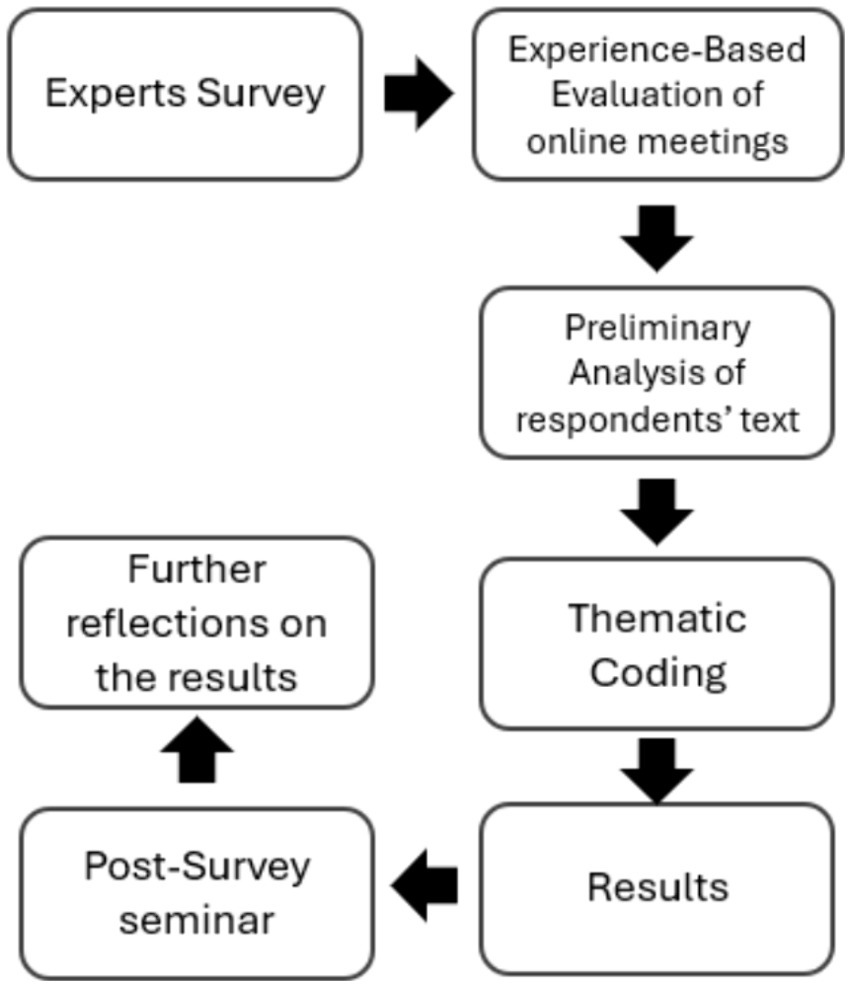

In addition, the survey findings were presented to experts in a follow-up two-hour seminar in July 2021 (see Figure 1). The two-hour seminar was conducted online (via Zoom) and was advertised in planning circles through social networks. Overall, it invited experts from the non-profit, private, and public sectors who are familiar with online video meetings to comment on the findings. The opinions and comments of participants were recorded and summarized by the research team. This procedure, also known as ‘Meta Evaluation’ (Scriven, 2009; Stufflebeam, 2011) is designed to gather additional perspectives from the obtained data, while brainstorming further with experts and those knowledgeable about the planning system and its apparatus considering these technological changes. These accounts – by both survey respondents and experts’ reviews- are presented in the following paragraphs, shedding light on some of the more nuanced and regressive outcomes of participatory planning processes that overtly rely on ICT and online meetings.

5 Findings: problematizing online public meetings in planning

Survey respondents acknowledged the participatory merits of online planning platforms. They mentioned the flexibility of being able to meet online and the ability to save time and money traveling to those meetings as being clear benefits (see Mualam et al., 2022). In addition, respondents highlighted the ability of young families and technologically-savvy stakeholders to lodge objections and to actively participate in hearings which become more accessible when conducted online. The consensus across all those who completed the survey was that Zoom and other video-conferencing tools have been crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic and should be further developed and harnessed by planners to better planning, as well as to make it more efficient and approachable (Mualam et al., 2022). Some informants added that efficiency is imperative to planning, and thus it is crucial post-COVID to develop online tools that can make online meetings better, thereby streamlining the planning process:

“The issue is crucial and its advantages outweigh the disadvantages. Reality has forced us to quickly switch to using familiar technological tools that are successful in other fields of employment. If we can embrace their advantages (documentation, efficiency, order) and understand the difficulties and find solutions, we can achieve great planning efficiency and will be able to generate the necessary trust between the various participants.”

Thus, respondents view efficiency, trust, and technological innovations as being interconnected, and perceive them as imperative for the continuation of planning in times of crisis and beyond. However, this rose-tinted view of online planning meetings was not shared by some respondents. Some insisted that efficiency is not the primary consideration in participatory processes. One planner alleged that “although Zoom meetings save a lot of traveling back and forth, they cannot replace the regular face-to-face meetings.” This view was reinforced by other respondents who highlighted that some members of the public prefer to attend face-to-face hearings rather than virtual ones. Another added that in some planning authorities, public officials insist on conducting face-to-face meetings when the public is involved. Unlike meetings between developers, experts, and officials, communities and members of the public are more likely to appreciate actual in-person meetings:

“We are still quite divided with respect to public hearings of objections. At the moment, when there are opponents [i.e., members of the public who object to statutory plans, N.M] we hold the hearings face-to-face with the understanding that there is no substitute for a meeting between people. In addition, in our estimation, especially in discussions in the local planning committee, many times it is important for people to feel that they have been heard, and this happens in a more pronounced way during an in-person meeting.”

However, the above citation also assumes that face-to-face participation is superior to ICT. The respondent was of the opinion that meeting in person to discuss planning matters is preferable. Indeed, this may be an unwarranted assumption given more critical views on planning which view it as a top-down practice that is rife with biases and manipulations. This opinion can be explained by looking at the very nature of planning, which may lead some to resort to face-to-face meetings in order to counter these inherent flaws instead of relying on ICT which only amplifies them. Specifically, planning can be perceived as being quite alienating as an impersonal and bureaucratic process (Brownill and Inch, 2019). Consistently, scholarly contributions find that bureaucrats tend to mold processes that result in power imbalances and unequal geometries (Ash et al., 2018). Some note that these imbalances are rooted in the planning process itself; as Forester observes in one of his seminal books, “all people may be created equal, but when they walk into the planning department, they are simply not all the same” (Forester, 1989, pp. 86–87). Online participation adds another ‘layer’ of alienation by presenting a virtual barrier to participation for those who are not technologically savvy therefore supporting respondents’ opinion that face-to-face engagements are superior to online meetings. As another informant notes, participation and online meetings are actually contradictory terms: “planning is a procedure, and it is hard to manage without eye contact [and thus] remote meetings are not suitable for public participation.”

These accounts were further echoed using a meta-evaluation of the survey findings. When these results were presented in a follow-up seminar, experts opined that while efficiency is certainly achievable via online planning platforms, and whilst the pandemic has encouraged the use of these technologies in everyday planning, it has also undermined planning in a number of ways. First, planners highlighted the fact that they face extreme difficulties reaching disadvantaged and marginalized groups when over-relying on online hearings. Second, and consequently, planning remains ill-informed about crucial public needs related to planning. Third, some commentators went as far as noting that this practice is not a coincidence nor innocent, but rather is explicitly directed from above, reflecting structural and political forces at work.

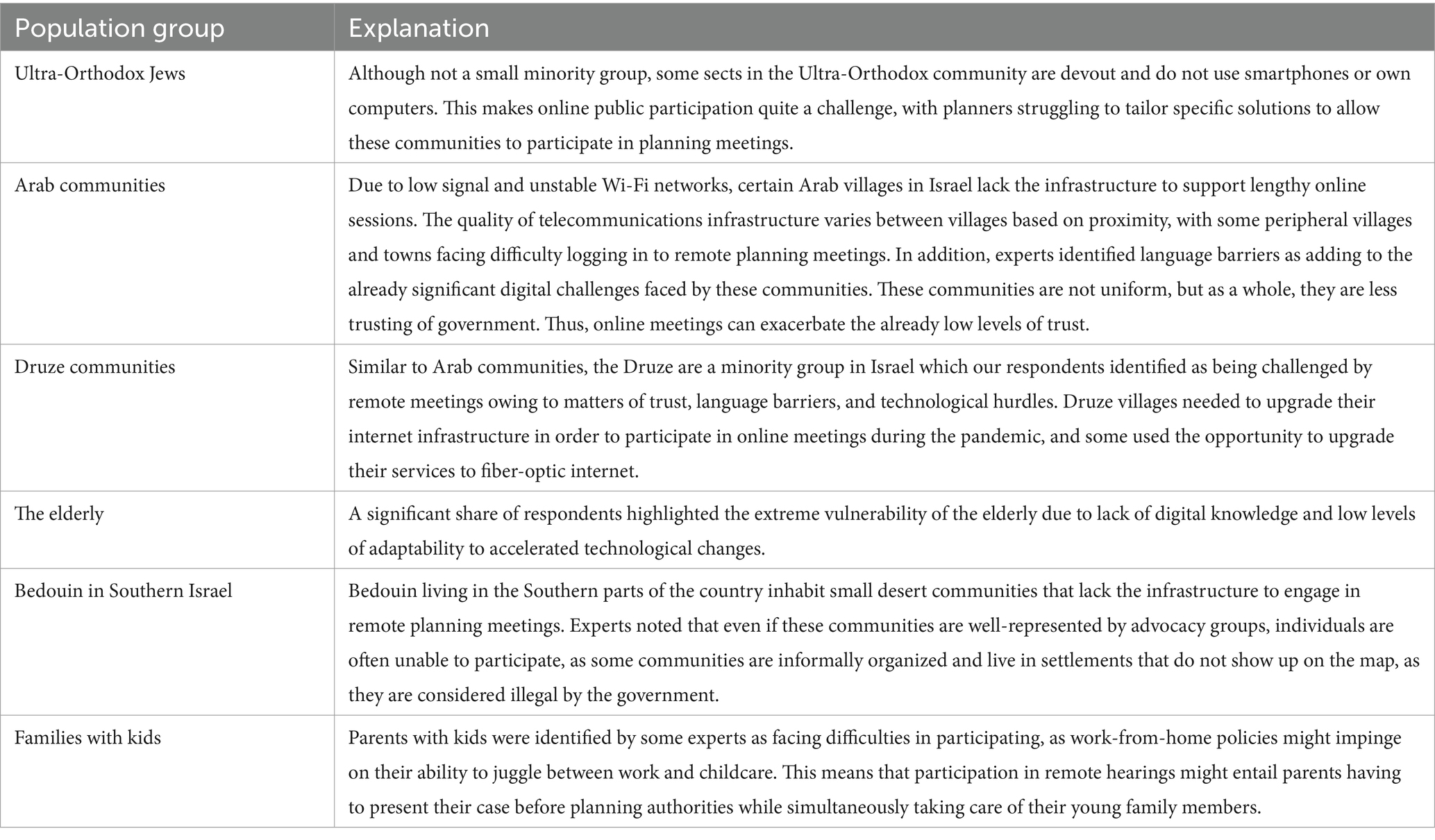

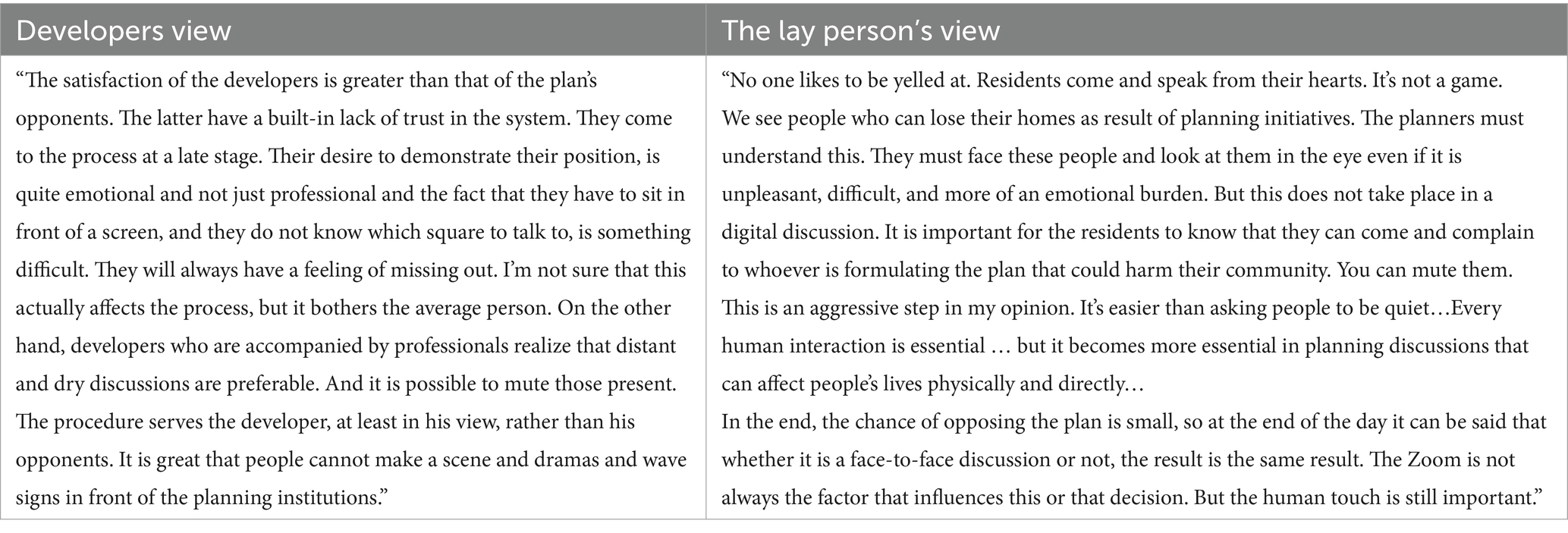

Speaking about power imbalances, experts described the nuanced and disparate experiences of those participating in online meetings (Table 1). It emerged that those who represented real-estate interests and developers tended to praise the functionality of Zoom and other video-conferencing apps, while those who represented the general public highlighted the exclusionary nature of these meetings. Table 1 contrasts these two accounts.

Table 1. Key characteristics of two major groups participating in remote planning meetings. A summary of observations made during an experts’ seminar.

The two opposing views on remote planning hearings can be demonstrated through two very illuminating quotes by experts as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Developers versus general public views on remote participatory processes. Select quotes from experts’ observations.

Both sides in this debate are aware of power imbalances and the likely trajectories of the debate. Although those representing the general public understand the structural forces at work here, they still insist that for the sake of democratization, online planning meetings should not be pursued as the default option, and that attempts should be made to transcend beyond mere tokenism.

Notably, this recurring preference by respondents for face-to-face engagements does not necessarily imply that they believed that these types of meetings can change power imbalances, or the course of planning itself. Respondents were not necessarily naïve or delusional thinking that face-to-face engagements are a panacea for the disenfranchisement that is often rooted in planning practice. As shown in Table 2, some commentators preferred face-to-face engagements in order to simply look decision-makers in the eye. They were not necessarily expecting to change the outcome of planning, but rather to have their day before the planning committee in what they perceived to be a more respectful and familiar setting.

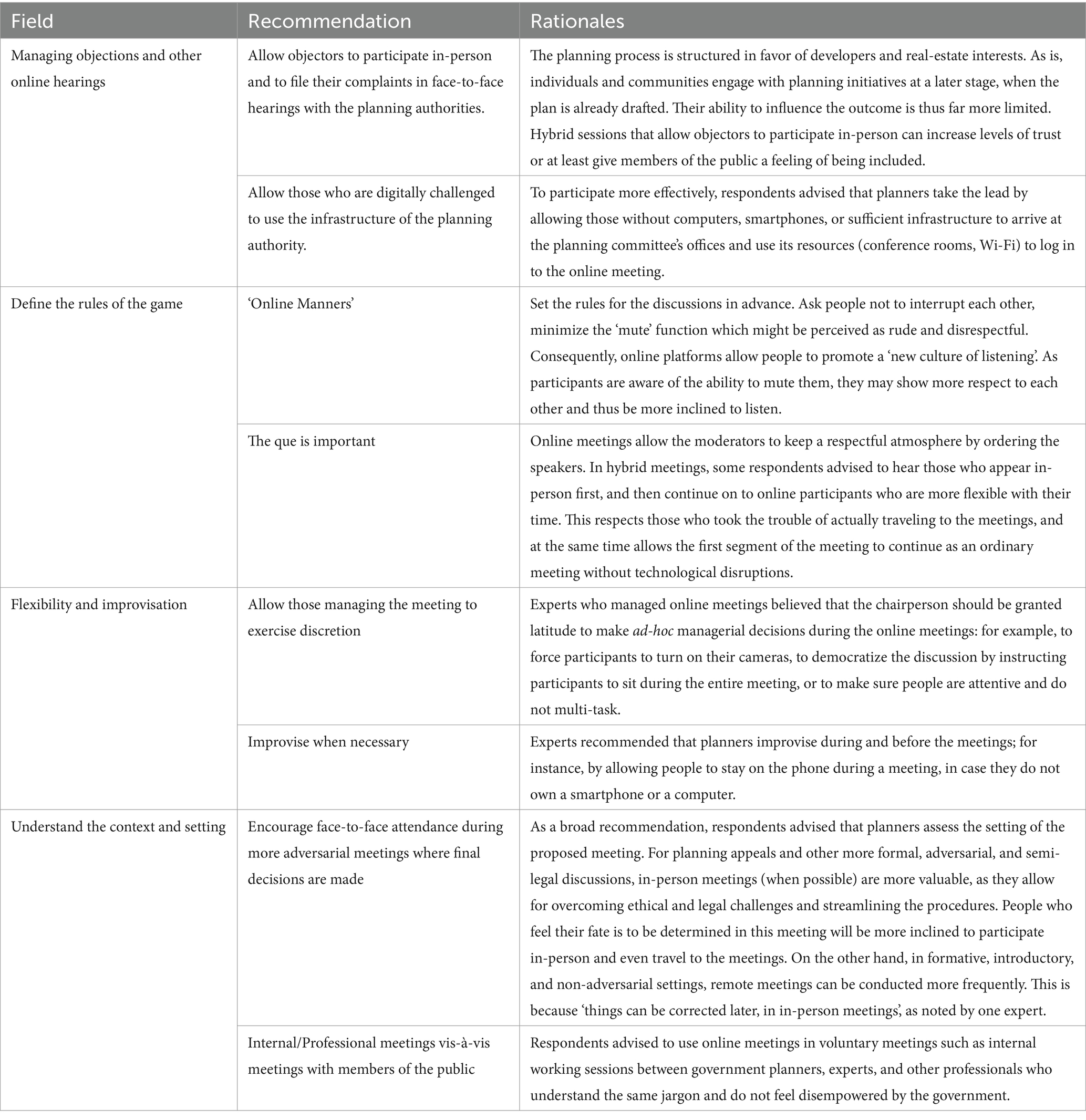

These accounts were reinforced by other respondents reflecting on their experiences with Zoom and other videoconferencing tools. Survey respondents considered a range of exclusionary repercussions brought about by participation in online hearings. This includes the marginalization of populations who find it difficult to use computers and cellular applications (for example, the elderly or disadvantaged groups including the Bedouins in the southern areas of the country), or the impact on families with kids (for a summary, see Table 3).

An expert who attended online meetings added that this regressive impact is further accentuated by planners themselves, who craft online hearings in a manner which deepens social cleavage and disparities. For example, by allowing experts and elected members to attend planning meetings while driving, the planning process itself changes, as multi-tasking noticeably affects the attentiveness and commitment of planners toward the general public participants. Another respondent viewed the whole shift to online hearings as creating “a guild of those who are connected and those who are not.” This is mirrored by the inability of online participants to ‘read the planning table’, that is, to decipher the intricacies and the dynamics of the discussion, and to uncover important details about the planning meeting. According to one expert, members of the public who participate remotely cannot read the full ‘mental map’ of the discussion before them:

“I want to see the dynamics of the discussion. Who is talking to whom, and who is consulting with whom. Who sits next to whom during the discussion. These are things that are no less important to me as someone who participates in a public debate before a planning institution, and this is not the case in a digital meeting.”

Marginalization is thus potentially embedded in the use of ICT in planning processes.

These challenges bring to the fore the crucial role of planners and specifically the chairperson of each remote planning meeting. These professionals need to reflect on the suitability of the platform and their ability to create engaging and meaningful consultations. One expert shed light on this issue by questioning the fairness of e-participation and the duty of planners to self-reflect:

Is this the right form of managing the process? Is it possible to apply rules of integrity and fairness through our computer screens? Is this the high road for public institutions? [When I was chairman] I made a decision to reinstate some face-to-face activities of the planning committee. Public service should be accessible. The public should not be in front of computer screens to be serviced. Additional troubling questions arise:...when a planner presents a plan before the committee, can he do so with a toddler sitting on his lap? Is it fair?

The aforementioned accounts mesh well with progressive scholarship in planning, which prescribes that planning can become better, and by doing so represent the community’s needs (Healey, 1992; Innes, 1996). This aligns with contributions that allege that it is possible to carve out face-to-face interactions of storytelling, communicative engagements, and community empowerment in planning, irrespective of ICT means. And yet, in terms of future lessons for planners, can one expect ICT use in remote meetings to fix patterns of exclusion without simultaneously attending to the ways that face-to-face participatory planning processes already exclude some participants? We return to this question in the concluding remarks.

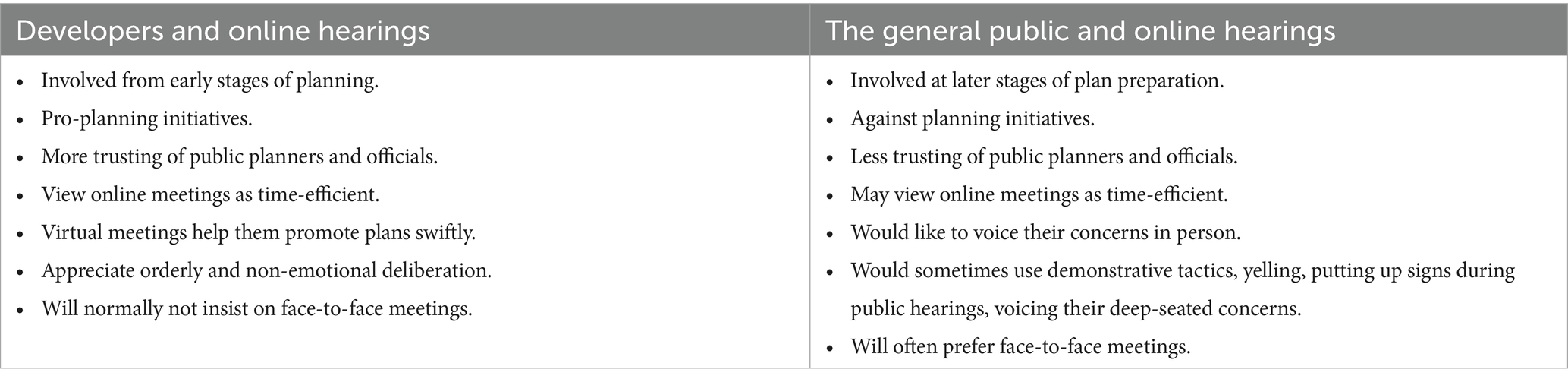

6 Future lessons for planners

Survey respondents and experts who participated in the ensuing follow-up seminar were of the opinion that despite the drawbacks of online meetings, there are certain steps that could be taken to make remote meetings more inclusive. Some of these recommendations echo the ones made in previous studies and in other contexts around the world (Radtke, 2023; Robinson et al., 2023).

Respondents believe that planners should assess the relevant crowd and expand the opportunities of certain groups to participate face-to-face. They also opined that the chairperson of the planning authority presiding over the meeting should take considerable steps to make sure the meetings are open to all, even if that means inviting certain stakeholders to physically arrive at the planning committee’s offices in order to allow them to log in to the online hearings from there with assistance from local planners. Moreover, the issue of mediating technology was highlighted by some, with respondents noting that it is crucial that planners make the use of technology easier and more accessible for participants. Table 4 summarizes other recommendations.

Some of these recommendations can amount to mere tokenism, such as the first, which acknowledges the limited ability of the general public to effectively change the trajectory of planning processes. Some can also be accused of not using technology to alter the balance of power between the planners and the ‘planned-for’, neglecting to carve out new processes and inclusionary practices that build better participatory processes than the ones prior to COVID. In addition, these recommendations do not solve the inherent problem of planning meetings- lack of trust in the government, (let alone post-COVID alienation)- and the need to conduct ‘quality control’ by assessing the level of representation of the participants attending the session (Chassin, 2022). The aforementioned suggestions to increase participation are noteworthy, but they reinforce the fact that in Israel, as in other places around the globe, “community engagement did not feature large in anticipated or desired digital changes” (Daniel et al., 2023, p. 13).

7 Conclusion

The digitalization of life during COVID-19 has certainly accelerated procedural change and impacted the planning profession around the world. While the benefits of digital communication are discernible, the pandemic and subsequent policy changes brought with them exclusionary practices. The findings from Israel are in line with similar ones from the US, Canada, Australia, UK, New Zealand, and Germany (Iroz-Elardo et al., 2021; Radtke, 2023). They suggest that alongside the impressive potential and tangible benefits of online meetings, e-participation in planning is jeopardized by multiple challenges.

When asked to reflect on some of these challenges in the age of acceleration, artist Chani Volpo provided the following visual interpretation (Figure 2) of our findings. While planners were quite successful in adopting technological tools and changes into their daily work, accelerated changes in the planning world also meant accelerated exclusion, with risks of a new type of technological gentrification. Broadband internet and other innovations could not hide the grim reality of disenfranchised communities and other populations unable to take part in the new and fast-emerging online meetings arena. Having said that, those participating in remote meetings can help improve this mode of communication, and indeed, several survey participants recommended a range of steps and policies that could make remote planning hearings more inclusive in the future. However, taken as a whole, the case of Israel during and post-COVID also illustrates that online planning meetings have mostly encouraged speedy and fruitful discussions for elites and those already holding power, including developers and real-estate interests. Government planners, whether or not attempting to mitigate the discriminatory implications of online planning, were primarily concerned with keeping the planning machinery operational during times of crisis. This has had significant exclusionary implications, which should be considered when making future technical leaps. Moreover, the focus of practitioners and academics on discussions about ICT in participatory planning during the pandemic, important as they are, cannot leapfrog over the larger picture of planning itself as being too often coopted by power brokers. And when public engagement is often challenged for being iniquitous, one cannot hope to fix patterns of exclusion simply by using innovative ICT tools as during the pandemic, without tending first to the underlying patina of discriminatory practices in planning as a whole.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

NM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to extend his gratitude to the experts and survey respondents whose input was crucial during this study. In addition, he wishes to thank Shvut Lifshitz for her assistance, and David Max for his invaluable comments on an earlier draft.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alterman, R., and Carmon, D. (2011). Will you hear me? The right to file objections to planning committees- according to law and practice. Haifa: The Center of Urban and Regional Studies.

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 35, 216–224. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225

Ash, J., Kitchin, R., and Leszczynski, A. (2018). Digital turn, digital geographies? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 42, 25–43. doi: 10.1177/0309132516664800

Bartlett, G. (2020). 10 tips for improving our online meetings|Consensus Building Institute. Available at: https://www.cbi.org/article/10-tips-for-improving-our-online-meetings/ (Accessed February 20, 2024).

Bedford, T., Clark, J., and Harrison, C. (2002). Limits to new public participation practices in local land use planning. Town Plan. Rev. 73, 311–331. doi: 10.3828/tpr.73.3.5

Boeing, G., Besbris, M., Schachter, A., and Kuk, J. (2021). Housing search in the age of big data: smarter cities or the same old blind spots? Hous. Policy Debate 31, 112–126. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2019.1684336

Bouchard, N. (2016). The dark side of public participation: participative processes that legitimize elected officials’ values. Can. Public Adm. 59, 516–537. doi: 10.1111/capa.12199

Bourdakis, V., and Deffner, A. (2010). “Can urban planning, participation and ICT co-exist? Developing a curriculum and an interactive virtual reality tool for Agia Varvara, Athens, Greece” in Handbook of research on E-planning: ICTs for urban development and monitoring. ed. C. Nunes Silva (Hershey, PA: IGI Global/Information Science Reference), 268–285.

Bouregh, A. S. (2022). Analysis of the perception of professionals in municipalities of Dammam metropolitan area towards introducing E-participation in Saudi urban planning. Int. J. E-Planning Res. 11, 1–20. doi: 10.4018/IJEPR.297516

Brooks, M. P. (2002). Planning theory for practitioners. Chicago, IL: Planners Press, American Planning Association.

Brown, G., and Chin, S. Y. W. (2013). Assessing the effectiveness of public participation in neighbourhood planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 28, 563–588. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2013.820037

Brownill, S., and Inch, A. (2019). Framing people and planning: 50 years of debate. Built Environ. 45, 7–25. doi: 10.2148/benv.45.1.7

Cairney, P., and Wellstead, A. (2021). COVID-19: effective policymaking depends on trust in experts, politicians, and the public. Policy Design Pract. 4, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2020.1837466

Chassin, T. N. (2022). The future of civic Technologies for the Involvement of citizens in urban planning: 3D urban participatory e-planning in the spotlight. Lausanne: Ecole Polytechnique federale de Lausanne.

Conroy, M. M., and Gordon, S. I. (2004). Utility of interactive computer-based materials for enhancing public participation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 47, 19–33. doi: 10.1080/0964056042000189781

Daniel, C., Wentz, E., Hurtado, P., Yang, W., and Pettit, C. (2023). Digital technology use and future expectations: a multinational survey of professional planners. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 90, 405–420. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2023.2253295

Decorte, T., Malm, A., Sznitman, S. R., Hakkarainen, P., Barratt, M. J., Potter, G. R., et al. (2019). The challenges and benefits of analyzing feedback comments in surveys: lessons from a cross-national online survey of small-scale cannabis growers. Method Innov. 12:205979911982560. doi: 10.1177/2059799119825606

Dobrić Jambrović, D. (2022). “COVID-19 crisis Management in Croatia: the contribution of subnational levels of government” in Local government and the COVID-19 pandemic: a global perspective. ed. C. Nunes Silva (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 405–428.

Einstein, K. L., Glick, D., Godinez Puig, L., and Palmer, M. (2023). Still muted: the limited participatory democracy of zoom public meetings. Urban Aff. Rev. 59, 1279–1291. doi: 10.1177/10780874211070494

Evans-Cowley, J., and Hollander, J. (2010). The new generation of public participation: internet-based participation tools. Plan. Pract. Res. 25, 397–408. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2010.503432

Friedman, T. L. (2016). Thank you for being late: An Optimist’s guide to thriving in the age of accelerations. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Fung, A. (2015). Putting the public Back into governance: the challenges of citizen participation and its future. Public Adm. Rev. 75, 513–522. doi: 10.1111/puar.12361

Giesbers, B., Rienties, B., Gijselaers, W. H., Segers, M., and Tempelaar, D. T. (2009). Social presence, web videoconferencing and learning in virtual teams. Ind. High. Educ. 23, 301–309. doi: 10.5367/000000009789346185

Guimarães Pereira, Â., Rinaudo, J., Jeffrey, P., Blasques, J., Corral Quintana, S., Courtois, N., et al. (2003). ICT tools to support public participation in water resources Governance & Planning: experiences from the design and testing of a multi-media platform. JEAPM 5, 395–420. doi: 10.1142/S1464333203001383

Hampton, S. E., Halpern, B. S., Winter, M., Balch, J. K., Parker, J. N., Baron, J. S., et al. (2017). Best practices for virtual participation in meetings: experiences from synthesis centers. Bull. Ecol. Soc. Am. 98, 57–63. doi: 10.1002/bes2.1290

Haughton, G., and McManus, P. (2019). Participation in postpolitical times: protesting WestConnex in Sydney, Australia. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 85, 321–334. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2019.1613922

Healey, P. (1992). A planner’s day knowledge and action in communicative practice. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 58, 9–20. doi: 10.1080/01944369208975531

Huxley, M., and Yiftachel, O. (2000). New paradigm or old myopia? Unsettling the communicative turn in planning theory. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 19, 333–342. doi: 10.1177/0739456X0001900402

Innes, J. E. (1996). Planning through consensus building. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 62, 460–472. doi: 10.1080/01944369608975712

Iroz-Elardo, N., Erickson, H., Howell, A., Olson, M., and Currans, K. M. (2021). Community engagement in a pandemic. AZ: Tucson.

Kim, J. (2020). 7 Best Practices for COVID-19-Necessitated Online Meetings. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/learning-innovation/7-best-practices-covid-19-necessitated-online-meetings (Accessed February 20, 2024).

Laskey, A. B., and Nicholls, W. (2019). Jumping off the ladder: participation and insurgency in Detroit’s urban planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 85, 348–362. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2019.1618729

Legacy, C. (2017). Is there a crisis of participatory planning? Plan. Theory 16, 425–442. doi: 10.1177/1473095216667433

Li, W., Feng, T., Timmermans, H. J. P., and Zhang, M. (2020). The Public’s acceptance of and intention to use ICTs when participating in urban planning processes. J. Urban Technol. 27, 55–73. doi: 10.1080/10630732.2020.1852816

Lozano-Uvario, K. M., and Rosales-Ortega, R. (2022). “Jalisco versus COVID-19: local governance and the response to health, social, and economic emergency” in Local government and the COVID-19 pandemic: A global perspective. ed. C. Nunes Silva (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 607–630.

Marcuse, P. (2011). “Postscript: beyond the just City to the right to the City” in Searching for the just City: Debates in urban theory and practice. eds. P. Marcuse, J. Connolly, J. Novy, I. Olivo, C. Potter, and J. Steil (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge), 240–254.

Matamanda, A. R., Nel, V., and Chanza, N. (2022). “The political economy of COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from the responses of local government in sub-Saharan Africa” in Local government and the COVID-19 pandemic: A global perspective. ed. C. Nunes Silva (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 103–130.

McGee, R. (2023). The governance shock doctrine: civic space in the pandemic. Develop. Policy Rev. 41:e12678. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12678

Milz, D., and Gervich, C. D. (2021). Participation and the pandemic: how planners are keeping democracy alive, online. Town Plan. Rev. 92, 335–341. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2020.81

Milz, D., Pokharel, A., and Gervich, C. D. (2023). Facilitating online participatory planning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 90, 289–302. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2023.2185658

Mualam, N. (2014). Appeal tribunals in land use planning: look-Alikes or different species? A comparative analysis of Oregon, England and Israel. Urban Lawyer 46, 33–96. doi: 10.1177/0885412214542129

Mualam, N., Israel, E., and Max, D. (2022). Moving to online planning during the COVID-19 pandemic: an assessment of zoom and the impact of ICT on planning boards’ discussions. J. Plan. Educ. Res. :0739456X2211058. doi: 10.1177/0739456X221105811

Mukhtarov, F., Dieperink, C., and Driessen, P. (2018). The influence of information and communication technologies on public participation in urban water governance: a review of place-based research. Environ. Sci. Pol. 89, 430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.08.015

Norris, P. (2000). A virtuous circle: Political communications in postindustrial societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Odendaal, N. (2010). Information and communication technology and urban transformation in south African cities. Johanessburg: University of Witwatersrand.

Ormerod, E., and Davoudi, S. (2021). Governing the pandemic: democracy at the time of emergency. Town Plan. Rev. 92, 323–327. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2020.90

Pánek, J., Falco, E., and Lysek, J. (2022). The COVID-19 crisis and the case for online GeoParticipation in spatial planning. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 11:92. doi: 10.3390/ijgi11020092

Planning Administration (2020). Evaluation of the impact of COVID and the future of the planning system. Jerusalem: The Government of Israel.

Pokharel, A., Milz, D., and Gervich, C. D. (2022). Planning for Dissent. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 88, 127–134. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2021.1920845

Potts, R. (2020). Is a new ‘planning 3.0’ paradigm emerging? Exploring the relationship between digital technologies and planning theory and practice. Plan. Theory Pract. 21, 272–289. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2020.1748699

Presthus, V. (1951). British town and country planning: local participation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 45, 756–769. doi: 10.2307/1951163

Radtke, J. (2023). E-participation in post-pandemic-times: A silver bullet for democracy in the twenty-first century? Potsdam: Research Institute for Sustainability.

Robinson, P., Boyco, M., and Johnson Feature, P. (2023). Digital public participation: the complicated ways that technology platforms both help and challenge planners. Y Magazine 13, 29–32.

Saad-Sulonen, J. C., and Horelli, L. (2010). The value of community informatics to participatory urban planning and design: a case-study in Helsinki. J. Community Inform. 6, 1–22. doi: 10.15353/joci.v6i2.2555

Saari, A., Vimpari, J., and Junnila, S. (2022). Blockchain in real estate: recent developments and empirical applications. Land Use Policy 121:106334. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106334

Sanchez, T. W., Shumway, H., Gordner, T., and Lim, T. (2023). The prospects of artificial intelligence in urban planning. Int. J. Urban Sci. 27, 179–194. doi: 10.1080/12265934.2022.2102538

Sandercock, L. (2003). Out of the closet: the importance of stories and storytelling in planning practice. Plan. Theory Pract. 4, 11–28. doi: 10.1080/1464935032000057209

Santamaria-Philco, A., Canos Cerda, J. H., and Penades Gramaje, M. C. (2019). Advances in e-participation: a perspective of last years. IEEE Access 7, 155894–155916. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2948810

Schwartz-Ziv, M. (2021). How Shifting from In-Person to Virtual-Only Shareholder Meetings Affects Shareholders’ Voice (March 28, 2021). European Corporate Governance Institute – Finance Working Paper No. 748/2021. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3674998

Scriven, M. (2009). Meta-evaluation revisited. Edit. J. MultiDisciplin. Eval. 6, iii–viii. doi: 10.56645/jmde.v6i11.220

Seltzer, E., and Mahmoudi, D. (2013). Citizen participation, open innovation, and crowdsourcing: challenges and opportunities for planning. J. Plan. Lit. 28, 3–18. doi: 10.1177/0885412212469112

Shahak, M. (2020). The activity of planning boards during the COVID outbreak. Jerusalem: The Parliament of Israel.

Steuteville, R. (2021). Urbanists keep planning through crisis. Public Square. Available at: https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2020/04/09/urbanists-keep-planning-through-crisis

Thomas, W. (2020). Virtual planning committees to be given the green light. London. Available at: https://www.shoosmiths.co.uk/insights/articles/virtual-planning-committees-to-be-given-the-green-light#

Wilson, A., Tewdwr-Jones, M., and Comber, R. (2019). Urban planning, public participation and digital technology: app development as a method of generating citizen involvement in local planning processes. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 46, 286–302. doi: 10.1177/2399808317712515

Xiang, Z. (2018). From digitization to the age of acceleration: on information technology and tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 25, 147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.023

Yigitcanlar, T., Kankanamge, N., Regona, M., Maldonado, A. R., Rowan, B., Ryu, A., et al. (2020). Artificial intelligence technologies and related urban planning and development concepts: how are they perceived and utilized in Australia? J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 6, 187–121. doi: 10.3390/joitmc6040187

Keywords: planning, digitalization, inclusion, video-conference, participation, COVID, ICT

Citation: Mualam N (2024) Planning in the age of acceleration: a perspective on digital inclusion in online urban planning meetings. Front. Sustain. Cities. 6:1392953. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1392953

Edited by:

Ruth Potts, Cardiff University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Dan Milz, University of Hawaii at Manoa, United StatesFrancesco Sica, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Mualam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nir Mualam, bmlybUB0ZWNobmlvbi5hYy5pbA==

Nir Mualam

Nir Mualam