- 1Department of Architecture, SALab Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 2School of Architecture and Interior, Lebanese American University, Beirut, Lebanon

- 3Master Planning & Studies Sections, Ras Al Khaimah Municipality, Ras Al-Khaimah, United Arab Emirates

Promoting sustainable communities aims at creating both environmentally and socially responsible living environments. This paper explores the role of affordable housing in promoting the long-term sustainability of a community within healthy living conditions by closely examining the relationship between affordable housing, urban development policies, and sustainability, with the capital of Lebanon, Beirut, serving as a case study. The first part of the paper focuses on the current building laws issued in the official newspaper in 2004 using a content analysis methodology to demonstrate the impact of the changes in the laws on the new morphology and social fabric of the city through the creation of a favorable environment for big developers, wealthy property owners, and real estate agencies and, at the expense of old city residents and low-income families. The second part of the paper uses the qualitative analysis methodology to justify the presence of large unused stock of residential units in Beirut, referring to information from multiple data sources selected based on their applicability to sustainable development, affordable housing, and urban planning in areas related to the case study, Beirut. This part then investigates the potential presented by this stock of residential units in Beirut to increase the supply of affordable housing and foster a sustainable community. This paper argues that the promoted vertical expansion of the city weighs heavily on the environment and fails to provide a diverse mix of housing units, excluding a significant portion of the community from the city. Alternative development models aligning with principles of sustainable development and challenging the current building laws can promote social inclusivity, reduce urban sprawl, and minimize environmental impacts associated with new constructions, thus preserving the city’s physical and social fabric.

1 Introduction

Sustainable communities are characterized by a balance of economic, environmental, and social welfare while being accessible to all people, regardless of their background and income level. One of the main aspects that contribute greatly to reaching a community’s long-term sustainability is promoting affordable housing since it provides housing opportunities for low-and moderate-income individuals and families within healthy living conditions. As per the World Green Building Council (WorldGBC, 2023), there are five key principles to sustainable and affordable housing which are: Habitability and Comfort, Community and Connectivity, Resilience and Adaptation to a changing climate, Economic Accessibility, and Resource Efficiency and Circularity. It is estimated by the European Parliament (European Parliament, 2020) that around 80% of cities worldwide still need affordable housing options for the majority of their population. However, many solutions to the global housing crisis already exist, as per the case of many neighborhoods in Beirut, Lebanon. Beirut, a city of contrasts that has overcome many challenges and instabilities over the decades, consists of a layering of urban developments from different eras. The first part of this study delves into the current building laws in Beirut and their consequences.

By examining the evolution of building laws, we can assess their influence on the city’s physical form, architectural styles, and social cohesion. Building law and regulation is a main driver for development and, thus, a key to understanding the city’s urban fabric. In the second part, the study presents the vacant stock of residential units that results from the lack of incentives to renovate them and the profitability of selling them to large-scale developers due to the incentives of the building laws. In the third part, the paper argues how, historically, the city has faced challenges related to rapid urbanization, lack of proper urban planning, and inadequate regulations. These factors have contributed to the haphazard growth of the city, resulting in an inconsistent urban fabric and unequal distribution of resources. The post-war and the concurrent successive crises left the government unable to cater to affordable and sustainable living solutions. The country’s abandonment in the hands of the private sector or other sporadic initiatives that cannot replace the government’s responsibility towards its population is currently affecting the sustainable growth direction of the country. The findings reveal that changes in building laws have led to the demolition of older structures and the construction of high-rise buildings, often catering to luxury housing and commercial developments. This trend has altered the city’s skyline, erasing its historical identity and exacerbating socioeconomic disparities. As a result, affordable housing options have become increasingly scarce, forcing many residents to live in substandard and overcrowded conditions. This has negatively impacted the community’s overall quality of life and sustainability. Sadly, the capital of Lebanon has lately faced many challenges that changed the course of urban development and real estate in the city, such as the recent economic crisis, which started in 2019, led to the complete stop of housing loans and private loans, thus resulting in a decrease in the demand to buy houses. In addition, the country’s political and economic instability resulted in a tragic decline in foreign investments. Furthermore, the Beirut Port explosion in August 2020 caused widespread damage to buildings and infrastructure, leaving over 300,000 people displaced from their homes and over 150,000 buildings damaged or destroyed. All of which significantly contributed to the segregation between the high- and low-income groups while failing to provide a diverse mix of housing units and thus leaving many vacant buildings throughout the city.

In most cities, vacant buildings are rare and stand out as they are often seen as mysterious and may even be the subject of legends and ghost stories. However, vacant buildings are common in Beirut, especially in some neighborhoods. Some of these vacant buildings have become well-known landmarks due to their history, size, or unique features. However, most of the city’s vacant buildings are ordinary apartment blocks built between the French Mandate period and the start of the Lebanese Civil War (Pedrazzoli, 2018). Before Lebanon achieved its independence, during the French mandate, the country’s first building laws were adopted. Over time, the laws’ structure evolved according to the demands of the construction field. The most recent building laws were enacted into law in 2004 and announced in 2005. After enacting new construction legislation, several implementation decrees were issued and published in the official newspaper. This study covered the implementation of decrees and codes in the construction sector.

The paper examines the structure and roots of Lebanon’s building regulations, which have been established at multiple governmental levels to control building initiatives to safeguard structural integrity, safety, and zoning compliance. The Lebanese Building Code acts as a primary framework for the country. The laws are dynamic, often modified by decrees, regulations, and suggestions to reflect changes in economic policy, new building techniques, and technology advancements. The document’s purpose is to review and suggest changes to the Lebanese building laws, published in the official gazette in December 2004.

2 Literature review

In Lebanon, an ancient country with many community interactions and commercial exchange traditions, massive urbanization has raised the vulnerable risks of poor urban settlements, combined with the effects of climate change on unsustainable urban growth. Part of the city reached its peak as the densest, most populated area in the world; however, the residential conditions are usually poor, and many socioeconomic challenges have also been affected by the effects of unaffordable and not sustainable urban planning strategies, affecting the vulnerable conditions of life of poor residential communities, due to the scarcity of adequate infrastructure and poor quality of residential buildings. Many areas, not only in the suburbs, result from urban, economic, and social complexity that suffered poverty many years ago. Local political speculation and destructive events, combined with the ongoing climate exchange, had reached dangerous residential conditions (see Figures 1, 2).

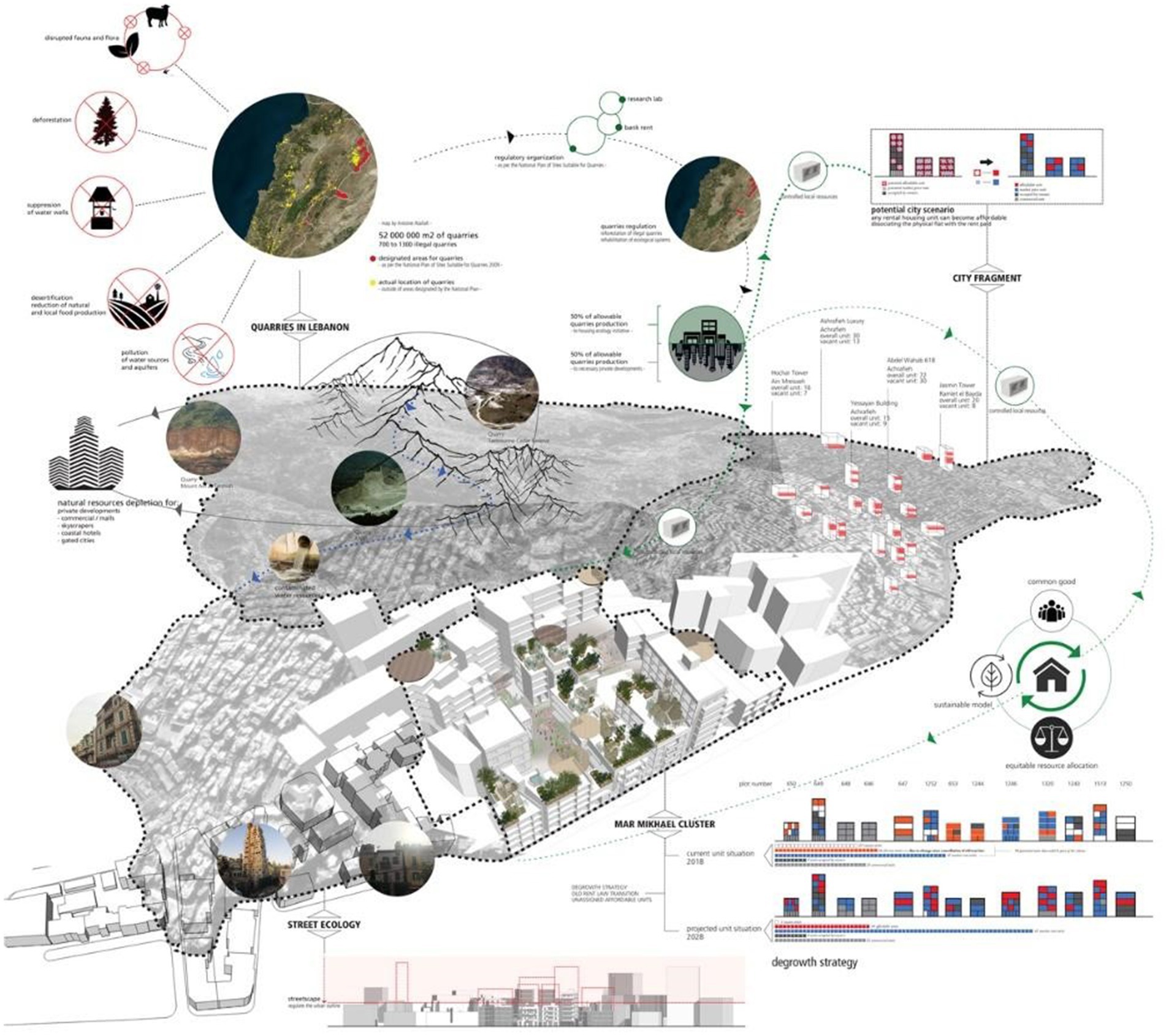

Figure 1. Contemporary view of Beirut: many strategies and project initiatives are nowadays under development for targeting sustainable Beirut growth (Credit: Protective Housing Ecologies project, by Roula El Khoury, Candice Naim, Lea Helou, Fadi Mansour, Ali Assaad, Patrick Abou Kahlil, http://burau.com/project/14/).

Figure 2. Stability derived from affordable housing can produce beneficial impact on community health, level of education and social well-being (Credit: Protective Housing Ecologies project, by Roula El Khoury, Candice Naim, Lea Helou, Fadi Mansour, Ali Assaad, Patrick Abou Kahlil, http://burau.com/project/14/).

2.1 Past models for urban growth

Beirut today is the result of a continuous process of territorial demarcation (El Khoury, 2016) that shaped the new recognizable city skyline. The Beirut urban fabric results from historical complexity where political, social, and economic events merge in a crowded combination of problems, tragedies, and lack of control. In 1960–70, the southern periphery increased with a strong identity of communitarian suburbs with independent spatial, social, and political governance (Harb, 2003). Since the 1990s, the city’s physical and social transformations have been remarkable. The development has been driven by the interaction of economic and political powers that transformed the Lebanese capital from a city of low and mid-rise buildings, with aesthetic influence to international style, to high-rise buildings of a contemporary city by dismissing, unfortunately, the old urban fabric and not protecting and preserving the past. In the last decades, Beirut has been transformed from local traditions and materials to an imported model of a city of alien free-standing ghost structures, claiming its own vertical identity without being connected with the traditional urban context. Many authors (Fawaz, 2008; Harb and Atallah, 2015; Gebara et al., 2016; Mazzetto and El-Khoury, 2020) debate how Beirut has been transformed over the last 150 years from a sparse community settlement to a stratified and dense urban structure. In the 1990s, the political program and the consequent social control generated a solid and strategic configuration of institutional powers that, with a remarkable mobilization capacity, achieved great success in political results and military defiance in 2000. The building regulation at the end of the war supported the idea of building up a resurgent image of Beirut by following Rafik Hariri’s reconstruction of a Mediterranean city with the southern suburb transformed into high-quality residential buildings, industrial areas, and commercial activities together with bank districts and new places for leisure gentrifying southern suburb into an imaginary vision of the reconstructed Beirut capital (Harb and Atallah, 2015) the complex relationship between private owners. Public institutions have frequently affected the residential housing market, favoring the private interests of public and governmental institutions concerning the individual capacity of managing institutions and personal relationships within the public sphere. Personal interest has affected the production of governmental laws and regulations that have enhanced a model of illegal and corrupted housing production and market prices (Saksouk, 2021). Many interconnections were documented between the markets and city-wide parameters, such as the residential housing demand, the price of land, and the directly connected political governance. The post-war political stability generated many relations with the market institutions and contractors responsible for the Beirut capital reconstruction through banks that facilitated the capital accumulation (Fawaz, 2004). Much damage affected the Beirut neighborhoods during Lebanon’s Civil War (1975–1990). For the reconstruction, Rahif Fayad, a Lebanese architect and urban planner, was 2006 in charge of the master plan for the southern Beirut suburbs. He made many comparisons between the Solidere project and the Jihad el Iaamar, concluding that “in Hareit Hreik and the other cities, we reconstructed for the people living there before. Solidere was reconstructed for foreign investors and rich people. Not at all those who were living in the city before.” Fayad, with other architects, tried to reconstruct the pre-war urban fabric based on his personal experience and personal space memories. He had a critical approach to reconstructing historical events, retracing the past, and establishing discussion and strong, motivated arguments in the contemporary context (Fayad, 2014, 2016). Beirut is not an exception in a rapidly changing world, and its urban growth, which started in the early 2000s (Hammoud, 2020), produced fast urban renovation changes extended to both locals and foreign investors. The ambitious and contradictory project of rebuilding Beirut’s city center, which the Lebanese war had destroyed, was promoted by Solidere. Consequently, in the last two decades, many neighborhoods in Beirut have been affected by massive transformations that have radically renowned the housing stock, landscape, and relationship between people and spaces (Gebara et al., 2016).

2.2 Vacant residential units

Although the reconstruction process moved in diverse directions, from passionate participants to private and corrupted interests, many residential units were abandoned during the war. Residents moved away, and people experiencing poverty and squatters occupied unused and vacant places (Harb et al., 2019). During the reconstruction, many neighborhoods were affected by a gentrified approach targeting new luxury residential complexes and towers, especially close to the Mediterranean Sea (Fawaz, 2009; Tonkiss, 2018). Many demolitions affected the old urban fabric and promoted the private interests of real estate investors (Khechen, 2018). Nowadays, the vacant stock of residential units results from the lack of incentives to renovate them and the profitability of selling them to large-scale developers due to the incentives of the building laws (Fawaz, 2004). Many buildings are still uninhabited, and while they should address some inhabitants’ needs to be more productive and functional without being considered abstract objects without functions. Beirut has an incomparable quantity of unlet and unsold spaces (Pedrazzoli, 2018) condensed in a single city. However, more impressive is that most of them are old ones that are a consistent portion of the townscape in specific neighborhoods (Fawaz, 2008). Entire vacant skyscrapers and many residences result from a fragile local real estate market. The unlet units are so common, and their history is deeply rooted in the local tradition that they are considered standard routines for the Beirut inhabitants, although their number is extraordinary. Elsewhere, vacant buildings raise questions and curiosity for inhabitants and visitors. In Beirut, they are part of the real estate scenario. Most are disowned heritage, modest apartment units built between the French mandate and the civil Lebanese war. They are examples of modern architecture language located inside a traditional urban fabric structure, adapting to contingent orographic situations and searching for maximum exploitation. In such a way, they produce a dense and functional urban fabric that encourages social cohesion and street life, with a high level of social interaction, in a compact city model that currently lacks public transportation systems and public and green spaces.

The precious presence of unused buildings in Beirut could be an interesting opportunity to instigate the possibility of requalifying and reusing modern heritage within a coherent and aware residential needs framework. If approved, the proposed law by the General Directorate for Antiquities (GDA) could launch a massive approach to renovation works and reuse of abandoned buildings, adopting a sustainable strategy for the city’s future growth and promoting coherent restoration as a good practice. The methodology should also be shared between stakeholders and investors as a guideline for future intervention in unused residential buildings promoted by the Governmental Department of Monument with an incentive by the Real Estate Syndicate of Lebanon (Pedrazzoli, 2018). In this view, a sustainable model should be adopted for deeply divided societies to be integrated into residential neighborhoods by envisioning a programmatic and integrative urban strategy (Salamey and Tabar, 2008; Harb et al., 2019; Mazzetto, 2020a). The current construction law in Lebanon dates back to 2004 (Ashkar, 2014) when it was mentioned as a “Concrete Jungle” that became a representation of Beirut city. The law, which was always under relevant debates in the Lebanese Parliament while initially advocating for the common good and social advantages, totally favored the private real estate industry strictly connected to the private interest of the political elite. However, the law still defines the urban typology and morphology of the city, which is devoted to the vertical growth of the high-rise towers.

2.3 Lack of sustainable strategies, gentrification, disasters, and private sector control

Historical processes and events are strictly connected with people and buildings in 2020, on August 4 (Aouad and Kaloustian, 2021). The Port of Beirut blast damaged around 7,700 residential apartments in around 10.00 buildings, reaching a blast radius of 3 km, affecting the lives of around 300,000 people. The traumatic event impacted the fragile balance of previous years based on unstable urban approaches adopted for the city since the development of the French mandate circa 1921–1943 (El Khoury and Ardizzola, 2021). The blast impact provides an opportunity to investigate fundamental aspects of city planning, including disconnection and discontinuity of masterplans, missing links between city and suburbs, city and waterfront, heritage preservation and the fast city urbanization, need for public spaces, lack of sustainable design and urban planning strategies that negatively affect the quality of city life, highlighting the urgent need to target a better sustainable growth for improving the quality residents life, especially in the area affected by the blast. In literature, we usually hear about disasters in many cities; however, we have yet to hear about the post-disaster and the adopted strategies to recover and rebuild the city. For Beirut, the blast in 2020 (Trad, 2022) has focused attention on the neighborhood of Gemmayzeh, which was the most damaged and affected by the explosion. In history, Beirut was destroyed and rebuilt many times for many natural reasons, such as earthquakes, human wars, and explosions. This is why learning from past mistakes is an important starting point for improvement. Gemmayzeh has various architectural typologies generating a wide variety of non-homogeneous urban fabric related to the historical period, such as the Ottoman Empire, French mandate, independence, and contemporary architecture. Such characteristics are very similar to many other neighborhoods in Beirut. Particularly important are the typologies built up between 1860 and 1920, known as the “Beiruti Architecture,” very sustainable in considering important environmental aspects in the design such as sunlight, wind orientation, water supply, green resources, and the use of traditional and natural construction techniques and materials. After the restoration works, many apartments were refurbished without considering the environmental aspects of Beirut Architecture, and industrial materials were adopted without preserving the architectural identity nor preserving the eco-friendly and sustainable design approach while extending their service life. The port blast and the successive crises that left the government unable to cater to affordable and sustainable living solutions had led the country into the hands of the private sector or other sporadic initiatives that cannot replace the government’s responsibility towards its population. However, in a fast-growing city, urban development has to consider environmental and sustainable strategies to improve healthy and sustainable growth, especially in the residential context (Sabry and Dwidar 2014; Annan et al., 2016; Rahmayati, 2016; Moussa, 2017; Mazzetto, 2020b, 2022) referring to sustainable strategies and architecture that have been provided recently for commercial areas and souks (Youssef and Mefleh, 2019) and to a recent design approach of Mar Mikhael, neighborhood (El Khoury, 2019), that constitutes the basis for the conduces analyses and reflection on future strategies to target a sustainable country growth. Many authors debate possible sustainable design strategies and proposed developments involving the complexity of urban, architectural, and landscape solutions, advocating for comprehensive approaches to reach sustainable guidelines compatible with the investigated context. Many authors (Lorens et al., 2022; Wojtowicz-Jankowska and Bou Kalfouni, 2022) investigate possible sustainable design strategies with a holistic vision to upgrade the vulnerable condition of urban settlements located in the coastal areas with particular attention to the risks and impacts caused by climate change impacts, in the Beirut case study. Sustainable strategies for transforming Lebanese coastal settlement can minimize and neutralize the climate change challenges in urban settings by adopting sustainable design approaches. Planning and adopting regulations and specifications to increase the quality of coastal urban settlements are efficient results that can mitigate future climate impacts.

3 Methodology

The study focuses on two main aspects that can contribute highly to sustainable communities in Lebanon, particularly in its capital, Beirut.

1. Affordable housing supports economic stability by enabling individuals to live closer to their workplaces, reducing commuting distances, and easing transportation-related emissions. It also enhances local economies by attracting and retaining a diverse workforce.

2. Stable housing offered by affordable housing initiatives can positively impact health, education, and overall well-being. When individuals have access to affordable homes, they experience reduced stress and can allocate more resources toward other essential needs, such as healthcare and education.

The research paper’s literature review examined several topics essential to sustainable urban development, including public health, social inclusivity, affordable housing, and the impact of changes in legislation on the urban setting. The review adopted keyword searches using a wide range of databases, including Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), JSTOR, Google Scholar, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis Online, SAGE Journals, SpringerLink, and LexisNexis Academic, in order to compile a wide variety of multidisciplinary literature essential for an in-depth narrative review on social policy, sustainability, and urban planning.

The study refers mainly to qualitative data analysis rather than quantitative ones since few documents and data regarding statistics and numerical values on the topic are available. Most research has been based on literature reviews, published articles, and books.

The study covers various topics, from the socioeconomic effects of legislative changes and the history of city growth to the problems caused by abandoned residential units and notable events like the Beirut Port explosion. It is arranged topically. Each topic is examined in a broader story highlighting the intricate relationships between sustainability and urban development in Beirut, offering a wide viewpoint without concentrating too much on particular facts.

This qualitative analysis integrates information from various sources, such as expert opinions, recent research, and historical narratives, to create a coherent story that evaluates the effects of historical and modern urban planning techniques. Instead of quantitative data, the method relies mainly on idea synthesis to comprehensively understand sustainable growth in cities, particularly Beirut.

The documents used data sources selected on their applicability to sustainable development, affordable housing, and urban planning in areas related to the case study, Beirut. The research focused on materials to discuss the Lebanese housing and urban development legislation and their socioeconomic implications. Comparative studies of comparable cities or areas were also considered to offer further perspective. This methodology guaranteed an all-encompassing perspective that integrated historical and modern evaluations, especially appreciating works after major incidents such as the explosion at Beirut Port. These are essential for understanding the present situation and potential developments.

The study presents the notion of community sustainability using a multimodal framework, taking into account the social, economic, and environmental aspects of urban existence. In the context of Beirut, in particular, this paper emphasizes the vital role that low-income housing plays in creating long-term sustainability within communities. It contends that the city’s social cohesiveness has been weakened, and socioeconomic gaps have widened due to the present building regulations, which have biased growth in favor of luxurious and high-rise developments.

The article promotes changing these laws and implementing new development strategies that put environmental sustainability and social inclusion first.

This involves Beirut’s substantial inventory of unoccupied residential buildings to boost the supply of cheap housing, encouraging more equitable urban growth that benefits all socioeconomic groups. The study highlights the significance of sustainability in urban planning by incorporating economic stability, decreased environmental effects, and increased social welfare into the city’s growth strategies. This comprehensive understanding of sustainability goes beyond ecological concerns to consider the community’s general health and the residents’ well-being. It advocates for reorganizing urban development to promote fair distribution of resources, enhance living standards, and preserve Beirut’s urban landscape’s cultural and historical continuity.

4 The changing building laws and the transformation of the image of the city

In Lebanon, the government typically issues building laws, regulations, and codes at various levels, including national, regional, and municipal authorities. These laws govern building construction, renovation, and maintenance to ensure safety, structural integrity, and compliance with zoning regulations.

The main document that outlines building laws in Lebanon is the Lebanese Building Code, which provides guidelines and standards for construction practices. The issuance of building laws in Lebanon can involve a combination of legislation, decrees, regulations, and guidelines. These documents are periodically updated to reflect changes in construction practices, technology, and legal requirements and to align with the country’s evolving economic policy.

The first building laws in Lebanon were issued during the French mandate—before the country’s independence—and their format has evolved over time to address the changing needs of the construction industry. The latest building laws were legislated in 2004 and issued in 2005. Following the issuance of the new building laws, several implementation decrees were issued and published in the official gazette. This paper discussed codes, regulations, and implementation decrees that are issued and currently adopted in the construction industry.

Updates on building laws and any changes or amendments are published on the Ministry of Public Works and Transport website and other relevant municipal authorities’ channels. The Order of Engineers and Architects usually compiles them into a booklet and sells them to the public. The last booklet issued by the Order of Engineers and Architects, including the latest amendments discussed in this paper, was published in 2017.

This paper will examine the current Lebanese Building Laws issued in the official gazette issue 66 in December 2004 and propose some modifications of the previously legislated laws issued in 1983. The document includes four chapters and 29 articles. This paper will only address Chapter 2, tackling the technical conditions of the new building laws that will drastically affect the morphology of the city and its image.

4.1 Article 11: natural light and ventilation requirements

In this article, the building code confirms that all rooms designed for living are required to have an opening to a street or a backyard, allowing natural light in and proper ventilation of the room. In the second paragraph of the same article, the following spaces were exempted from the previous requirements: Bathrooms, corridors or transitional spaces, storage spaces, laundry rooms, maid’s rooms, and kitchens, except if their size is larger than eight sqm. What is surprising in this article is that the “maid’s” room is not considered “a space designed for living,” so it is not required to have any opening and thus allows the developer to allocate any leftover space in the project plan easily. Such text is highly discriminatory and fails to respect basic human rights.

4.2 Article 12: building set back from the street

Article 13 defines the setback of buildings from the street according to a specific classification directly related to the street’s width and the traffic frequency on each. However, this article does not define a maximum setback that could otherwise unify the building height and the alignment of the buildings to the street. Owners of large plots can thus set back as far as they wish and build higher structures, maximizing the apartments’ value and revenues from their sales. This article constitutes a clear incentive for larger plot development and does not enforce any urban design guidelines to protect or preserve the existing morphology of the street.

4.3 Article 14: surface exploitation ratio and total exploitation coefficient

No changes to the surface exploitation ratio or the total exploitation coefficient were dictated in this article. However, other considerations defined in this article will directly affect both the coefficient and the ratio of exploitations.

Balconies defined as outdoor extensions of indoor spaces were previously allocated 20% of every floor area and excluded from the total exploitation coefficient, provided that they do not exceed 25% of the total built-up area and remain open. The new law has legislated closing these areas with glass panels, transforming them into extra sellable indoor spaces. This new practice has gradually eradicated this typology from the city and enforced a glazed envelope around every new building.

The external double wall area has been excluded from both the surface exploitation ratio and total exploitation coefficient because it is said to contribute to the insulation of the building, decrease energy consumption, and thus protect the environment. This new addition amounts to approximately 10% of the built-up area and is also an extra sellable area. Note that the new law does not specify how this new norm is enforced. The developers now automatically claim the extra 10% without necessarily building double external walls.

The staircase and the escalator shaft have also been excluded from the total exploitation coefficient. An area of 20 sqm has been excluded from the coefficient or added to the total built-up area, and six additional sqm in case of the incorporation of an extra elevator. In the case of high rises, every development typically includes 2–3 elevators and thus benefits from 10–15% extra sellable area. The sum of the additional square meters gained by the developer or the owner of a real estate project equals 40–45% of the previously allowed built-up area! These additions have been legislated without changing the so-called exploitation “coefficient” or “ratio.”

4.4 Article 7: building envelope

Another modification to the building envelope was necessary to fit the additional allowable square meters. The previous law set the height of the building at the edge of the plot twice as long as the width of the street, which would define an external building envelope that would not fit the additional areas. The new law increased this coefficient to 2.5, allowing three additional floors to a building sitting on a typical street in Beirut.

4.5 The new building laws and the city’s growth

The significant transformation of the city’s fabric, largely influenced by capital forces and global trends, would only have unfolded so dramatically with the institutional and regulatory frameworks that fueled the construction boom of the 1990s. The alignment of economic and political interests in Lebanon towards a shared vision played a pivotal role in reshaping Beirut into a new urban reality (El Khoury, 2016).

This paper tries to explain the evolving cityscape not just in terms of its physical elements and structures but rather in the context of the underlying changes that have driven their creation. As previously discussed, the city’s morphological transformation has resulted from a systematic process influenced by institutional and regulatory frameworks. The successive building laws, especially the 2004 law, accelerated land development, leading to a significant 40% increase in built-up areas, and have been instrumental in changing the city’s physical and social fabric. It is also worth mentioning that the 1992 amendment facilitated the construction of high-rise buildings by encouraging the consolidation of small parcels to go beyond the typical building envelope set at 50 m. This rapid expansion altered the city’s appearance and has profoundly affected the spatial qualities of streets and the mix of its inhabitants.

During this urban development, developers were granted the right to enclose all balcony spaces, ultimately changing the traditional lifestyle associated with Beirut’s balconies. This shift towards enclosed spaces behind glass panels has marked the end of the social and cultural significance that Beirut’s balconies once held for its inhabitants.

Implementing the new building law also should have considered the importance of regulating street facades and rooftop alignment. The construction of taller buildings set back from the street disrupted the traditional street perspective. It gave rise to new spaces completely disconnected from street life due to their intended uses, as noted by Fayad (2014). Additionally, other laws concerning land acquisitions and subdivisions played a role in facilitating both foreign and local investments in the real estate sector, leading to the gradual disappearance of Beirut’s old urban fabric and the emergence of a somewhat chaotic landscape filled with new structures.

For the past 15 years, Beirut has been growing in population, built-up area, car traffic, daily consumption, and waste production. In the absence of any law or initiative to provide the necessary public amenities and spaces, green areas, and playgrounds for the city’s residents, the new-build laws have been instrumental in destroying the old city fabric, disfiguring the architectural heritage, and displacing the underprivileged and poor communities.

4.6 The new rent law

In Beirut, two different rent systems co-exist. The “old rent agreements” signed before 1992 are protected by the first system, allowing tenants to keep renting housing low despite the significant increase in market rent since the end of the Civil Warl war. The second system covers rents made as of July 23, 1992, which do not subject the new rents to any cap or ceiling. Thus, a high increase was observed. The gap between the different rental systems is further exacerbated through illegal and exceptionalist practices, which are widely seen as a problem, as they strongly protect the tenants at the expense of the property owners. Many scholars have argued that the rent gap in Beirut is the reason behind the susceptibility of land to renewed capital investment (Fawaz and Krijnen, 2010; Krijnen and De Beukelaer, 2015; Fawaz et al., 2018; Krijnen, 2018) and subsequently provoked neighborhood gentrification.

In 2017, a highly controversial law was introduced to address this issue. This law aims to gradually phase out the old rent system over 6 years by incrementally increasing rents until they align with fair market values. However, this approach is disconnected from wage realities and is anticipated to displace a significant portion of the population. Shortly after it was issued, the country witnessed the most acute economic crisis of its history, with a significant devaluation of the local currency implying a significant reduction in income. While tenants argued that the new rents were unaffordable and refused the increase, property owners remained exempted from property taxes, tariffs, and fines. The new rent law has yet to be applied. In the meantime, many residential units remain in extreme deterioration, not meeting healthy living standards and/or being vacant.

5 Discussion: the vacant housing stock and the opportunity for an alternative development model

“If thrown in the sea, Beirut would float.” With these words, Riccardo Pedrazzoli describes Beirut in his paper entitled Unlet, Unused, Unsold Beirut (Pedrazzoli, 2018), which talks about the vacant residential units in the city. In fact, due to the gradual and systematic increase of land exploitation dictated by the consecutive building laws, the existing building typologies of the city needed to be more attractive and more convenient regarding their financial profitability. Property owners were soon persuaded that if tenants were evacuated and a demolition permit for their property was obtained, they could level their existing edifice and build a considerably bigger volume that was up to ten times more profitable. As expected, a massive stock of vacant residential units emerged and expanded its portfolio throughout the last few decades. In Beirut, residential apartments have emerged as the fundamental element in an unregulated and excessively inflated real estate market driven by exchange and speculation (El Khoury, 2019). The market’s mechanisms and the roles of architects, planners, investors, developers, owners, and tenants collectively contribute to the continuous perpetuation and reinforcement of this intense commodification of housing units throughout the city.

A comprehensive and multi-sourced approach that requires an account of several studies, reports, and statistics that reflect a broad spectrum of challenges—economic downturns, political instability, urban decay, and the devastating aftermath of the Beirut port explosion—has been adopted to effectively comprehend and tackle the complex urban and housing dynamics in Beirut, particularly in light of the socioeconomic upheavals that subsequently followed the 2020 port explosion.

The Central Administration of Statistics in Lebanon (Central Administration of Statistics, 2019) is one of the most important data sources on housing, population demographics, and economic factors that impact urban housing trends. News from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) provided an understanding of the state of the economy and the various industries that are affected, such as housing and infrastructure. Rapid assessments by international organizations following the explosion at the port of Beirut drew the scope of the light damage. Critical sectors such as banking, housing, and tourism were severely damaged. The World Bank (World Bank in Lebanon, 2022) and the UN and EU completed a Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA) that evaluated damages between US$3.8 and US$4.6 billion and economic losses between US$2.9 and US$3.5 billion. In response, the Reform, Recovery, and Reconstruction Framework (3RF) was created in December 2020. It is an organized action plan designed to promote a people-centered recovery, address immediate and short-term needs, and start necessary structural reforms to guarantee transparent, inclusive, and accountable rebuilding.

The economic consequences of the explosion have been examined thoroughly in UN documents (United Nations UN, 2024), offering insights into how housing demands and urban planning needs have changed so rapidly. In this regard, the Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) for Beirut emphasizes the reconstruction of buildings damaged in the explosion per current efforts described in ESMPs for other building batches previously publicly announced. These initiatives guarantee adherence to both national laws and the Environmental and Social Framework of the World Bank. Initiated in reaction to the explosion, the UN-Habitat BERYT initiative focuses on supporting the cultural sector and rehabilitating heritage homes while emphasizing an extensive plan for sustainable development and urban rehabilitation.

The economic crisis that hit Lebanon presented an opportunity to address some of the real estate sector’s issues and slow down unsustainable developments. The downturn in the economy reflected directly onto the real estate sector and discouraged speculative investments, thus correcting the market. In response to the crisis, many developers were prompted to install energy-efficient systems, perform value engineering, and move towards more sustainable housing options. The crisis also catalyzed increased community involvement and the promotion of community and participatory initiatives to ensure that projects meet the emergent inhabitants’ needs and preferences. Despite favorable conditions to re-evaluate regulatory and policy frameworks, more must be done. In this context, we would like to propose an alternative development model for more sustainable housing solutions in the city.

In order to avoid the commodification of housing units, it is essential to disassociate housing from the real estate market circulation and the fantasy of economic growth. A new model for development needs to be put forward, prioritizing the “maturity”—not the city’s growth. For that purpose, it becomes inevitable not to propose policy improvements that would trigger a shift in the economy and the dominant mechanisms already in place. Below are underlined three major reforms that we believe are essential for this change:

Policy Reform 1: by invoking the state’s responsibility outlined in Housing Law (58/1965) and law (118/1977), measures should be taken to facilitate citizens’ access to housing. This involves recognizing shelter provision as a shared responsibility among municipal authorities.

Policy Reform 2: stricter controls should be enforced on new large-scale developments while imposing more stringent laws regarding plot mergers. The focus should be on promoting well-designed buildings, spaces, and places that value existing residential ecologies and contribute to their long-term well-being. To ensure a balanced housing system that does not solely prioritize the profit of producers and providers, reforms should be made to capital gain tax policies for property sales. Also, heritage assessment laws and land rights for demolition should be revised. These reforms recognize that housing serves economic and political purposes, aiming to maintain system stability.

Policy Reform 3: introducing more rigorous taxing mechanisms for vacant properties, particularly those within buildings already occupied by tenants, will incentivize property owners to participate in the city’s revitalization. Owners can either promote occupancy within existing housing stock or contribute financially to the common good as a form of retribution.

5.1 Proposing an alternative solution

In addition to the policy reforms, an inclusive socio-spacious platform mediating between the property owners and the tenants, led by a governmental entity, could be an alternative to Beirut’s current dominant development model.

The platform would control the speculative ownership of housing. It will aim to enhance housing availability, focusing on expanding the housing stock through public, collective, community, or resident ownership models. These models would be designed to benefit residents and can be subject to resident control. The landlords and property owners will be incentivized to place their properties on the platform through the following measures:

• Owners willing to renovate or refurbish their properties will have access to funds and subsidies with different modes of payment.

• The platform will manage the rental agreements, secure the rent collection, and ensure continuous occupancy through its network.

• Landlords and Property owners will refrain from the newly implemented taxing mechanisms that aim to safeguard individuals’ ownership rights while ensuring the preservation of the common good. These mechanisms are aligned with the objectives outlined in reform policies 2 and 3.

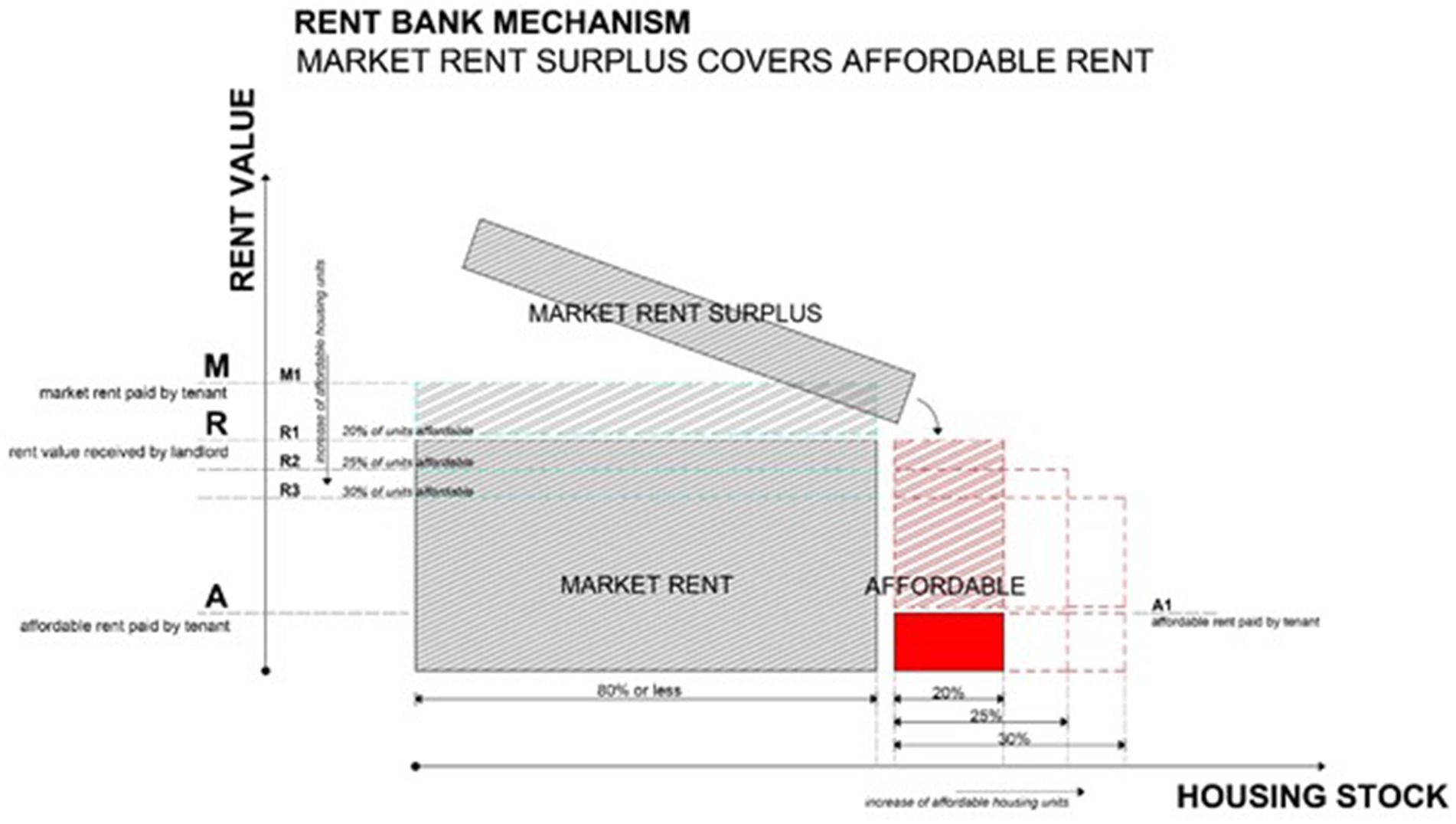

On the other hand, individuals and households, particularly those with low-income backgrounds (including those currently benefiting from old rent law agreements that are crucial for their financial stability), can enroll and determine their eligibility on the platform. Once they meet specific criteria for participation in the program, they are provided with a suitable property and offered a rent price within a range that spans from subsidized affordable rates to a controlled percentage of market prices. Regular tenants registered within the program but do not qualify for affordable rent subsidies are also given access to the pool of available units based on ongoing demand assessment. Landlords and property owners who register their units with the program will receive rental earnings based on a percentage of market values, regardless of whether their tenant pays affordable or market-value rent. The funds generated from properties’ rents priced at market rates (from regular tenants) will be used collectively to finance the price difference for affordable units. The platform will oversee the equilibrium between supply and demand within the program’s economy and the redistribution of surplus value from market-priced units to subsidize affordable rental properties. The platform’s role is to ensure a balance between the two aspects (Refer to Figure 3 for visualization). This model has been developed as a proposal brought forward by a group of professionals, including Candice Naim, Lea Helou, Fadi Mansour, Ali Assaad, Patrick Abou Kahlil, and Roula El Khoury, as an alternative to the current dominant model of development in Beirut. The Protective Housing Ecologies project was presented in response to a call for ideas organized by engineers and architects in Beirut and Public Works Studio, a multipurpose research platform.

Figure 3. The circulation of value within the platform mechanism. (Credit: Protective Housing Ecologies project, by Roula El Khoury, Candice Naim, Lea Helou, Fadi Mansour, Ali Assaad, Patrick Abou Kahlil, http://burau.com/project/14/).

Landlords will be entitled to receive a rent value, denoted as R, which is derived by subtracting a capped percentage (M-R) from the market price rent, M. Conversely, any surplus in market rent above the value R will be redistributed to offset the lower value, A, associated with affordable rent.

5.2 Benefits and implications

The proposed model outlined above provides flexibility in the affordable housing unit inventory and the corresponding rent values based on actual and specific demand. Rather than relying solely on new developments, this model allows for a certain percentage of existing housing units to be designated as affordable, thereby increasing the availability of affordable options.

The proposed platform aligns with a degrowth agenda that prioritizes transforming and improving the existing housing stock. These units can meet necessary living conditions standards and adhere to good design principles through renovation and refurbishment. The objective is to introduce more affordable spaces throughout the city and integrate them seamlessly into the existing fabric without requiring explicit zoning or designated buildings. Vacant units are brought into the rental market following funded or subsidized refurbishment offered by the program, increasing the number of affordable units over time while blending harmoniously with the existing surroundings and occupants. The scheme allows individual units to alternate between affordable rent values and market rent values based on the tenant occupying the apartment. As a positive long-term outcome, this approach would reduce or eliminate disparities in living conditions and location between affordable and market-rate units. This proposal seeks to cultivate a culture of active engagement with the environment rather than imposing rigid parameters and frameworks that restrict perceptions of housing. By promoting communal strategies for the city’s degrowth and involving existing governmental forums at the neighborhood level, a sustainable and thriving living ecology can be fostered within the diverse community of Beirut. By expanding affordable housing units throughout the city and integrating them into the existing urban fabric, rather than segregating them in specific zones, we can pave the way for a socially conscious transformation that recognizes city housing ecologies as a shared urban resource.

6 Conclusion

This paper argues that Beirut’s new building and rent laws promote city growth by increasing its built-up area and encouraging its vertical expansion. They must provide a diverse mix of housing units, excluding a significant portion of the community from the city. We call on the government to adopt a different strategy based on degrowth principles, promoting a more inclusive city where the government and its institutions will lead in implementing this new vision. By applying this proposal to a pilot cluster in the city, this paper argues for the possibility of rehabilitating an existing residential stock, putting it again on the market, and protecting its physical and social fabric. As such, this pilot project addresses the pressing needs of the inhabitants of Beirut and its property owners and promotes a more sustainable community in the city. The study researches the development of sustainable communities in Beirut. It emphasizes the urgency of searching for alternative development models that minimize their negative effects on the environment, promote social inclusion, and prevent urban sprawl. Future studies should assess the viability of suggested modifications to the building codes that seek to maintain Beirut’s social and physical landscape while advancing affordable housing. Examining how these regulations affect the socioeconomic gaps in the city is one aspect of the research.

Furthermore, a noteworthy prospect exists to investigate the feasibility of repurposing Beirut’s substantial inventory of unoccupied residential properties to augment the availability of reasonably priced housing. Examining sustainable and alternative urban design approaches that go against the grain might yield important information on promoting a more inclusive and sustainable urban environment. Urban planning techniques and policy decisions for Beirut and other cities experiencing comparable issues could benefit greatly from such research.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://burau.com/project/14/.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RE-K: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Prince Sultan University for paying the article processing charges (APCs) of this publication and their financial support.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of Prince Sultan University, CAD College of Architecture and Design, PSU SALab Sustainable Architecture Laboratory, LAU Lebanese American University, School of Architecture and Design for providing a supportive environment that encourages research and collaboration between institutions. Special thanks to RE-K’s colleagues, Patrick Abou Khalil, Ali Al Assaad, Lea Helou, Fadi Mansour, and Candice Naim, for their valuable contribution to the Protective Housing Ecologies project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Annan, G., Ghaddar, N., and Ghali, K. (2016). Natural ventilation in Beirut residential buildings for extended comfort hours. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 35, 996–1013. doi: 10.1080/14786451.2014.972403

Aouad, D., and Kaloustian, N. (2021). Sustainable Beirut city planning post august 2020 port of Beirut blast: case study of Karantina in Medawar district. Sustain. For. 13:6442. doi: 10.3390/su13116442

Ashkar, H. (2014). Lebanon 2004 construction law: inside the parliamentary debates. Civ. Soc. Knowl. Cent 1:20005. doi: 10.28943/CSKC.002.20005

Central Administration of Statistics , (2019), Housing characteristics, presidency of the Council of Ministers, Available at: http://www.cas.gov.lb/index.php/housing-characteristics-en (Accessed: May 1, 2024)

El Khoury, R. (2016). Reading Beirut: the architecture of banks and Beirut’s urban morphology: "banks street," the central bank and the spread of banks in vital areas of Beirut, The street-forming, re-forming. 2nd city street Conference, Faculty of Architecture, Art and Design (Faad), Notre Dame University Louaize, 3

El Khoury, R. (2019). Challenging dominant urban development models to promote a more sustainable community in Beirut, The way it’s meant to be. S. Arch 2019 Conference on architecture and built environment, Havana, Cuba

El Khoury, R., and Ardizzola, P. (2021). From the Port City of Beirut to Beirut Central District: narratives of destruction and reconstructions. Spool 8, 5–22. doi: 10.1386/ijia_00052_1

European Parliament (2020). REPORT on access to decent and affordable housing for all, Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2020-0247_EN.html

Fawaz, M. M. (2004). Strategizing for housing: An investigation of the production and regulation of low-income housing in the suburbs of Beirut. PhD Thesis. Massachusetts USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Fawaz, M. (2008). An unusual clique of city-makers: social networks in the production of a neighborhood in Beirut (1950–75). Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 32, 565–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00812.x

Fawaz, M. (2009). Neoliberal urbanity and the right to the city: a view from Beirut’s periphery. Dev. Chang. 40, 827–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01585.x

Fawaz and Krijnen (2010). Exception as the rule: high-end developments in neoliberal Beirut. Built Environ. 36, 245–259. doi: 10.3917/gen.051.0070

Fawaz, M., Krijnen, M., and El Samad, D. (2018). A property framework for understanding gentrification: ownership patterns and the transformations of mar Mikhael, Beirut. City, 22, 358–374. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13604813.2018.1484642 (Accessed: May 1, 2024).

Fayad, R. (2016). Globalized architecture in writing the neoliberal city. Beirut: Al Safir. Available at: http://assafir.com/Article/1/479008. (Accessed: May 1, 2024)

Gebara, H., Khechen, N.M., and Marot, B. (2016). Mapping new constructions in Beirut (2000–2013), Jadaliyya [preprint]

Hammoud, A. (2020). A review of the housing market in Beirut between 2005 and 2019. PhD Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Harb, M. (2003). La Dâhiye de Beyrouth: parcours d’une stigmatisation urbaine, consolidation d’un territoire politique. Genèses 2, 70–91. doi: 10.3917/gen.051.0070

Harb, M., and Atallah, S. (2015). “Lebanon: a fragmented and incomplete decentralization” in Local governments and public goods: Assessing decentralization in the Arab world, vol. 187.

Harb, M., Kassem, A., and Najdi, W. (2019). Entrepreneurial refugees and the city: brief encounters in Beirut. J. Refug. Stud. 32, 23–41. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fey003

Krijnen, M. (2018). Beirut and the creation of the rent gap. Urban Geogr. 39, 1041–1059. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2018.1433925

Krijnen, M., and De Beukelaer, C. (2015), Capital, state and conflict: the various drivers of diverse Gentrification processes in Beirut, Lebanon, L. Lees, H. Shin, and E Lopez. (Eds.) Global gentrifications: Uneven development and displacement. Bristol: Policy press. ISBN: 9781447313489. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/9508571/Krijnen_M_and_De_Beukelaer_C_2015_Capital_State_and_Conflict_The_Various_Drivers_of_Diverse_Gentrifi_cation_Processes_in_Beirut_Lebanon_in_Lees_L_Shin_H_and_Lopez_E_eds_Global_Gentrifications_Uneven_Development_and_Displacement_Bristol_Policy_Press_ISBN_9781447313489 (Accessed: May 1 2024)

Lorens, P., Wojtowicz-Jankowska, D., and Kalfouni, B. B. (2022). Redesigning informal Beirut: shaping the sustainable transformation strategies. Urban Plan. 7, 169–182. doi: 10.17645/up.v7i1.4776

Mazzetto, S. , (2020a). Envisioning future directions in public resources, conference proceedings of EURO-MED-SEC-03, holistic overview of structural design and construction, Y. Vacanas, C. Danezis, A. Singh, and S Yazdani. (eds.), Limassol, Cyprus, August 3–8, 2020, ISEC Press, ND, USA, 7, Available at: https://www.isec-society.org/ISEC_PRESS/EURO_MED_SEC_03/xml/AAE-10.xml

Mazzetto, S , (2020b). Preserving the Lebanese heritage to enhance the local identity, conference proceedings of ASEA-SEC-05, emerging technologies, and sustainability principles in structural engineering and construction, H. Askarinejad, A. Singh, and S Yazdani. (eds.), Christchurch, New Zealand, November 30–December 3, 2020. ISEC Press, ND, USA, Available at: https://www.isec-society.org/ISEC_PRESS/ASEA_SEC_05/xml/AAE-03.xml, 7

Mazzetto, S. (2022). Public spaces, values, and needs, K Holschemacher, U. Quapp, A. Singh, and S Yazdani, (Eds.), Proceedings of the fourth European and Mediterranean structural engineering and construction conference, EURO_MED_SEC_04 state-of-the-art materials and techniques in structural engineering and construction, ISEC Press California State University, Pomona, U.S., 9

Mazzetto, S., and El-Khoury, R. (2020). Influences and aspirations in the production of national projects in Lebanon and Kuwait: selected iconic projects by Sami Abdul Baki. Archnet-IJAR 14, 599–614. doi: 10.1108/ARCH-06-2019-0159

Moussa, R. (2017). Role of Local Festivals in Promoting Social Interactions and Shaping Urban Spaces. In Proceedings of the International Conference for Sustainable Design of the Built Environment (SDBE), London, UK, 20–21.

Pedrazzoli, R. (2018). Unlet, unsold, unused Beirut. The place that remains. Lebanese American University, Beirut. Available at: https://chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/sardassets.lau.edu.lb/arc_catalogs/the-place-that-remains-proceedings-essay-19.pdf (Accessed: July 12, 2023)

Rahmayati, Y. (2016). Reframing “building back better” for post-disaster housing design: a community perspective. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 7, 344–360.

Sabry, E., and Dwidar, S. (2014). Contemporary Islamic Architecture Towards preserving Islamic heritage. In Proceedings of the ARCHDESIGN’ 14 on Design Methodologies, Istanbul, Turkey, 8–10.

Saksouk, A . (2021). Where is law? Investigations from Beirut. Available at: https://chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/aub.edu.lb/Neighborhood/Documents/AbirNIReport.pdf (Accessed: September 9, 2023).

Salamey, I., and Tabar, P. (2008). Consociational democracy and urban sustainability: transforming the confessional divides in Beirut. Ethnopolitics 7, 239–263. doi: 10.1080/17449050802243350

Trad, C. (2022). Sustainable cities after disaster: Beirut, Lebanon. Master’s Thesis. Barcelona, Spain: Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

United Nations UN (2024). The Beirut housing rehabilitation and cultural and creative industries recovery (P176577) Available at: https://chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2024/04/240402_esmp_re_738_revised_clean.pdf, (Accessed: May 1 2024)

Wojtowicz-Jankowska, D., and Bou Kalfouni, B. (2022). A vision of sustainable design concepts for upgrading vulnerable coastal areas in light of climate change impacts: a case study from Beirut, Lebanon. Sustain. For. 14:3986. doi: 10.3390/su14073986

World Bank in Lebanon (2022), Overview, Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lebanon/overview (Accessed: May 1, 2024)

WorldGBC (2023), Sustainable and affordable housing. Available at: https://chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/worldgbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/C22.9056-WGBC_Affordable-Housing-Report_Master-2.pdf

Keywords: long-term sustainability, sustainable growth, healthy living, sustainable development, building laws

Citation: Mazzetto S, El-Khoury R and Malkoun J (2024) Promoting sustainable communities through affordable housing. A case study of Beirut, Lebanon. Front. Sustain. Cities. 6:1308618. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1308618

Edited by:

Noé Aguilar-Rivera, Universidad Veracruzana, MexicoReviewed by:

Sampa Chisumbe, University of Johannesburg, South AfricaGianluca Dalle Fratte, Università Iuav di Venezia, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Mazzetto, El-Khoury and Malkoun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Silvia Mazzetto, c21henpldHRvQHBzdS5lZHUuc2E=

Silvia Mazzetto

Silvia Mazzetto Roula El-Khoury2

Roula El-Khoury2 Joanna Malkoun

Joanna Malkoun