94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Cities, 27 April 2023

Sec. Cities in the Global South

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2023.922419

This study investigated how land rights formalization had affected land tenure security among landowners in two informal settlements of Lusaka and Chongwe districts, Zambia. It explored how social norms on land inheritance, decision making over land, marital trust and land related conflicts had been affected by the changed nature of land rights. Data was collected through a questionnaire survey of all the 302 households that had obtained title deeds at the time of the survey, two 3-in-1 focus group discussions and four key informant interviews. Results suggest that land tenure security is now a reality for residents that hitherto lived under constant threat of eviction. Landowners have benefitted from the formalization initiative through land laws and local norms that allow equitable access to land. Land rights formalization has curtailed land rights for secondary claimants such as extended family members, in preference for man, spouse and biological children. A sense of ownership undisputedly increased for men and women in the two study sites. About 50% of the respondents in both study sites indicated that formalization of land rights had not resulted in family conflicts. At least one-third from both sites reported an increase in love and trust between spouses after land rights formalization. About half of the respondents reported that no change in decision-making authority had occurred for men while 42% reported an increase. Formalizing land rights in informal settlements has entailed legalizing illegalities as regulations on plot boundaries are set aside by the state to achieve its aspirations of providing land tenure security to poor urbanites who would not otherwise have recourse to legal or regularized land. We recommend that caution be taken in promoting what is unarguably a pro-poor initiative to ensure that such initiatives should not incentivize future land encroachments.

Informal or unplanned settlements are a worldwide phenomenon and the number of people living in them is increasing (Nixon, 2020). Zambia has many such settlements countrywide which are locally popularly known as shanty compounds. Their population was estimated in 2002 to be increasing at an annual rate of 3 percent (Taylor et al., 2015). The country's capital city, Lusaka, has 45 unplanned settlements with a total of 1,220,085 residents (Central Statistical Office, 2013). These have been occasioned by a plethora of factors including population growth, socioeconomic dynamics, politics, and biophysical pressures (Simwanda et al., 2020).

Although unplanned settlements grew in density and number after Zambia's independence from British colonial rule in 1964, such settlements were a pre-independence phenomenon (Hansen, 1982; Makumba, 2019). Their origins can be traced to colonial urban settlement policies, which forced poor urban settlers to reside in marginal areas of the city that had not been planned as residential areas by city authorities (Nchito, 2007). New residents simply moved into the settlement areas and claimed parcels of land by constructing low-cost housing and other small structures such as shops and bars. The housing structures were relatively cheaper to rent and thus became a pull factor to many rural immigrants into the city looking for low-cost housing. With time, the population of these unplanned settlements expanded and by the early 2,000s accounted for around seventy per cent of the entire population of Lusaka city and comprised 20% of the city's residential land (UN-Habitat, 2007).

Having such a large proportion of the city's inhabitants in unplanned areas has brought about a myriad of socio-economic and environmental challenges. The unplanned settlements occupy and encroach on contested spaces in the city and thus continue to be a source of health, environmental, social and moral problems (Taylor et al., 2015; Msimang, 2017; Muanda et al., 2020). Furthermore, the houses were built without any building authorization by the city municipality as required legally.

Zambia's population stands at 19.6 million people with a population density of 26.1 persons per square kilometer (Zambia Statistics Agency, 2022). Although the country's area covers 752,614 square kilometers, only twenty percent (150,522 km2) of the land, translating to about 200,000 land parcels, was fully registered and 600,000 parcels were at various stages of processing as of 2014. The rest (about 80%) was unregistered (Tembo et al., 2018). This entails the vast majority of plots and houses are unregistered, illegal, and potentially resulting in diminished property rights and tenure insecurity. Tenure security refers to the degree of confidence held by people that they will not be arbitrarily deprived of their land rights or of the benefits derived from their land (Knight, 2010; Government of the Republic of Zambia, 2021a,b). Several scholars have observed that informality induces land tenure insecurity and has negative consequences on investments and land resources management (Chirwa, 2008; Ghebrua and Lambrecht, 2017). De Soto (2000) argued that the poor in developing countries fail to turn their land into capital because they lack formal mechanisms for protecting their property rights. Their tenure insecurity acts as a demotivating factor.

Formalization of property rights involves the provision of legal representation of property in the form of title deeds, licenses, permits and contracts, all of which must receive official sanction and protection from legitimate national authorities (Benjaminsen et al., 2009). Land rights formalization is argued to be especially beneficial for residents of informal settlements, as the illegal status of such settlements presents a level of precariousness not experienced by other residents, be they in customary areas or formal settlements without documentation for their land. Residents of informal settlements can be evicted legally anytime.

Some scholars posit that by formalizing their land rights, residents of informal settlements enhance their land rights claims and tenure security (Sjaastad and Bromley, 1997; Zevenbergen, 2000; Holden and Otsuka, 2014; Wily, 2017). Tenure security is associated with access to credit, stimulating entrepreneurship, provision of services and infrastructure, improved health conditions and the realization of the human right to adequate housing (Jimenez, 1984; de Soto, 1989; De Soto, 2000; Payne, 1997; Smith, 2001; World Bank, 2003; Di Tella et al., 2007; Field, 2007; Durand-Lasserve and Selod, 2009; Reerink and van Gelder, 2010). Furthermore, land rights formalization is theorized to facilitate land market transactions which indirectly leads to higher overall investment in land (Besley, 1995; Place, 2009; Holden et al., 2011; Lemanski, 2011; Ghebru and Holden, 2015).

However, the empirical evidence from several countries in sub–Saharan Africa that have implemented a wide range of land formalization initiatives since 2000 reveals mixed results. Despite the numerous espoused benefits arising from titling programs, a variety of challenges impede implementation on a large scale. For instance, developing countries within and beyond sub-Saharan Africa lack the necessary finances and capacity to execute the land formalization process because of the high costs required for land survey, title registration and issuance of title on a large scale (Sjaastad and Bromley, 1997; Toulmin, 2009; Bezu and Holden, 2014; Kim et al., 2019). Hence aid agencies and international financial institutions such as the World Bank, USAID, DFID, the European Union among others have financed formalization processes in some countries (Durand-Lasserve and Selod, 2007).

Furthermore, land formalization manifests a gender dimension with women at a greater risk of land tenure insecurity despite de jure equality with respect to land access (Ali et al., 2019). The prevalence of unfavorable customary practices and attitudes that restrict women's control over land resources inhibit fair participation in land formalization programs. For example, in Ethiopia, despite the introduction of progressive land reforms that promote rural women's rights to inherit and own land, discriminatory practices such as restrictions on land ownership continue to persist (Tura, 2014). Similarly, in Malawi's matrilineal societies, though women possess inheritance rights to land, men, be it husbands or uncles, exercise leadership in decision making and control over land, thereby disenfranchising women (Andersson Djurfeldt, 2020). Consequently, as men secure their property rights, those of women risk being undermined (Andersson Djurfeldt, 2020). Further, the landless, women, and orphans may not only be unable to take advantage of formal rights to assets but may find avenues of access effectively closed through the price increases that invariably attend formalization (Benjaminsen et al., 2009). Essentially, a danger inherent in formalization is consolidating existing inequalities (Benjaminsen, 2002; Sjaastad and Cousins, 2008).

Urban population growth presents challenges to large scale titling programs by triggering illegalities by wealthier individuals who include local residents, elites, politicians and local leaders in attempts to acquire property. This, however, is at the expense of the relatively poor and marginalized individuals. This high demand for urban property often leads to land conflicts and in some instances land grabbing which often overwhelm local government authorities (Chitonge and Mfune, 2015; Lombard and Rakodi, 2016).

Other challenges of large-scale titling include increased perceptions of displacements and tenure insecurity among marginalized individuals, lengthy processes, lack of policies to support titling objectives, failure to achieve intended titling goals and high interests in land by commercial entities (Payne et al., 2009; Lawry et al., 2014; Chitonge and Mfune, 2015; Lombard and Rakodi, 2016; Andersson Djurfeldt, 2020). Some scholars have noted that land rights formalization programs result in heightened insecurity due to displacements, especially among the marginalized groups in society, i.e., the poor and widows (Kyalo and Chiuri, 2010; Andersson Djurfeldt, 2020). For example, in Kenya, the process of converting communal pasture into private plots reinforced male dominance in property ownership as titles were issued to the men, hence increasing inequalities. Further, women lost their access to previously available resources such as livestock and other food products which they previously obtained through communal bargaining processes (Kyalo and Chiuri, 2010; Andersson Djurfeldt and Sircar, 2018).

In Zambia, the state embarked on an ambitious National Land Titling Program in 2015. The objectives of the program were to regularize ownership of untitled properties in towns and cities and by so doing, promote security of tenure for property owners on state land, reduce displacements, promote internal security and increase the revenue base and investment in the country and thus contribute to socio-economic development (Government of the Republic of Zambia, 2018; Tembo et al., 2018). During the issuance of the first 92 certificates of title to residents of Madido area in December, 2017, the then minister of the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources explained that the initiative was motivated by the government's resolve to accelerate social and economic development. This was to be accomplished by regularizing ownership of untitled properties in towns and cities, eradicating inequalities in gaining access to land in order to cater for all, and providing citizens with the impetus for access to credit (Government of the Republic of Zambia, 2018; Ministry of Lands Natural Resources., 2021).

The Zambia National Land Titling Program had a target of processing and issuing 300,000 certificates of title to landowners in areas where the program was being piloted by 2018. The Ministry of Land and Natural Resources established a unit specifically to deal with land titling under the National Land Titling Program. This is the National Land Titling Center. Later, it engaged a private company called Medici Land Governance to expand the program. However, reality fell short of aspirations, as program implementers faced challenges characteristic of such initiatives. The challenges included determining land ownership for claimants with incomplete or no documentation, determining property boundaries and upgrading paths to access roads to meet statutory standards. Since private infrastructure had been developed with little or no considerations for building standards, concessions had to be made between demolishing properties that were too close to public roads and those without sufficient space for access roads and providing title security (and its attendant benefits) to poor residents with no other opportunities to own land with secure and enforceable land rights. Arguably, this legalization of illegalities was instrumental to achieving the public good of social-economic development through the provision of legal property rights and all the opportunities this presented. Thus, this study sought to determine how land rights formalization had affected land tenure security among men and women landowners in the pilot areas. Furthermore, it explored how social norms on land inheritance, decision making over land and marital trust had been affected by the changed nature of land rights. Lastly, land conflicts, an indicator of threats to land claims was examined to determine the extent to which the land rights formalization had addressed this threat.

Land rights formalization in the two study sites started as part of the national land titling program, an initiative by the state to document all unregistered land in urban areas. Once the initial skepticism and fear of demolition of illegal structures and forcible evictions was over, landowners in the two study sites agreed to participate in the program, and mobilized the initial mandatory payments. The initial payment was ZMW 1,260 (USD73) for Madido and ZMW 625 (USD36) for Bauleni. This covered the survey fees and enabled the program implementers to survey the sites and draw sitemaps. The rest of the payments were to be made in monthly installments of ZMW 100 (USD6) for up to 36 months, for a total of ZMW 4,990 (USD286) in Madido and ZMW 3,747.93 (USD215) in Bauleni. This is about half what landowners spent to acquire title deeds through the normal process. Residents that managed to secure payments early were among the first to receive the title deeds. Better resourced households thus benefitted early in the process.

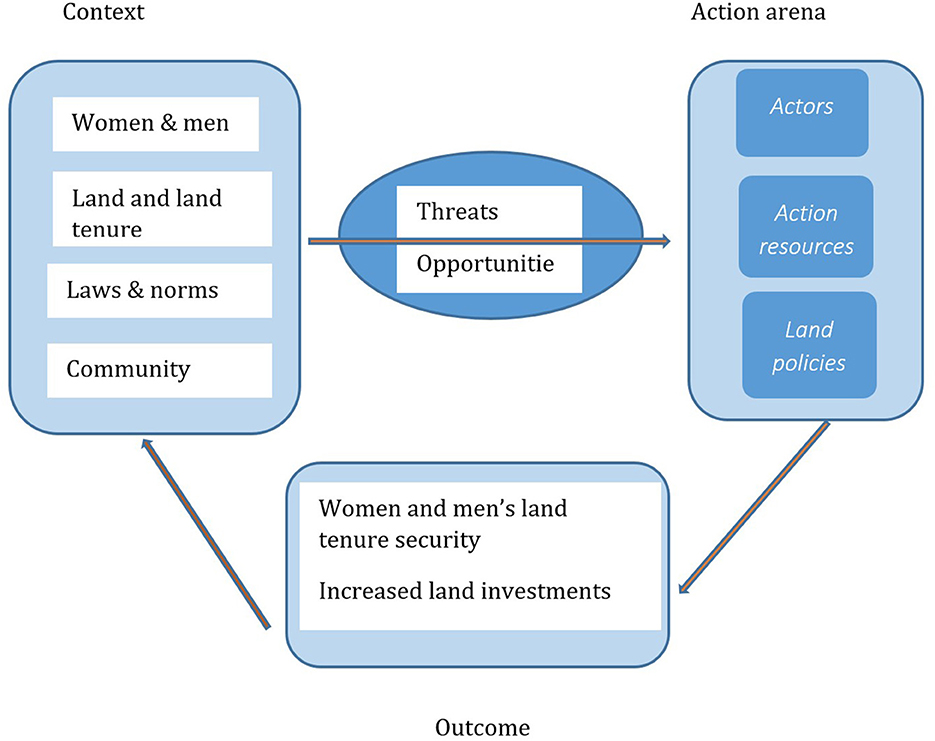

The conceptual framework is adapted from Doss and Meinzen-Dick (2018). The adaptation includes the addition of men to the analysis and its application to an urban setting. The framework incorporates four broad areas: the context, threats and opportunities, action arena, and outcomes (Figure 1). The context includes both formal and informal institutions (laws, practices, and norms), socio-economy and history. The threats and opportunities to land rights include the catalysts of change, both those that strengthen and those that weaken tenure security for men and women.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of factors affecting women and men's land tenure security [adapted from (Doss and Meinzen-Dick, 2018)].

The action arena includes both actors and action resources. The actors include every-one who influences land tenure security. The action resources are those resources that different actors can use to seek their preferred outcomes, and include money, education, networks and social status. Finally, men's and women's land tenure security is the outcome of interest, and feeds back to shape the context for men and women's land rights in the future. Land tenure security has three components, (i) Completeness of the bundle of rights (ii) Duration, and (iii) Robustness. Completeness of the bundle of rights looks at the extent to which one person or persons hold the various rights. Duration is about whether the rights are held for a short or long-term and /or if the length of time is known. Robustness is an examination of whether the rights are known by the holders, accepted by the community, and are enforceable.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, the paper describes the study sites and the study methodology. Section 3 presents and discusses the empirical results. The last section concludes the paper and draws out policy implications.

Fieldwork was conducted from two study sites, Bauleni and Madido residential areas (Figure 2) between August and October 2020. The two areas were selected as study sites as they were pilot areas for the National Land Titling Program in the Lusaka city region (www.mlnr.gov.zm) and thus were ideal for an examination of program outcomes.

The two study sites are located in Lusaka and Chongwe districts respectively. Of the total area covered by the country (752,614 square kilometers), Bauleni covers an area of about 1.533 square kilometers and Madido about 0.891 square kilometers. The areas experience a humid subtropical climate, and are overlain on uneven depth of folded and faulted schist. Bauleni had a population of 64,000 (Tidwell et al., 2019) while Madido's was at 210, 672 in 2010. Bauleni and Madido have 3,697 and 2,109 households respectively. Bauleni consists of low-income and middle-income households. Most of its residents are in informal employment. The situation is different for Madido with most of its residents in formal employment, and a large majority of them are middle income households. The genesis of the two areas is very different (Sommerville and Tembo, 2019). Bauleni started in the 1970s as a small unauthorized squatter settlement formed by laborers who worked in nearby commercial farms (Cheyeka et al., 2014). With time, its population grew. It was legalized in 1998. Implementation of the National Land Titling Program started in Bauleni in 2018.

Madido—also known as Chelstone Extension to the residents—is located on land that previously belonged to a public agricultural college, the Natural Resource Development College. Around 2006, local party officials of the then ruling political party, the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy encroached on the land, illegally demarcated it into land parcels and sold them to interested persons. The population quickly grew and Madido became an informal settlement. The Ministry of Lands subsequently canceled the college's land ownership rights before offering them to the illegal settlers and has since regularized their ownership through the issuance of title deeds (Personal communication, Key informant, October 2020). Implementation of the National Land Titling Program started in Madido 2017 (Sagashya and Tembo, 2022).

An explanatory sequential mixed methods approach was employed (Bryman, 2012). In order to come up with a sampling frame of households that had obtained title deeds, a mapping exercise was conducted. Every household in the two study sites was visited and a short survey conducted to establish whether it had participated in the land titling program, whether title deeds had been obtained, and if so when. The mapping exercise was conducted with the help of community members that were widely known and well regarded. For Bauleni, it was with the participation of a long-term female resident whose family was the first to settle in the area. The resident was identified with assistance from the local authority officers based at the Lusaka City Council office in the area. The resident had first-hand knowledge of almost all the housing properties and their owners. She was well known in the area as an executive member of several local development initiatives. She was deputized by two females familiar with the area through their part-time work with Lusaka City Council as distributors of water bills in the area. In Madido, the field team was assisted in the mapping exercise by two male residents who had been the central figures as they had been actively involved in the illegal demarcation and subsequent sale of land parcels. Further, When the National Land Titling Program commenced, the two were recruited as resource persons to explain the program to community members and to encourage the community members to participate in the program. The two were thus trusted by the residents, who were otherwise wary of strangers asking about land matters, given the illegal genesis of the residential area.

After the mapping exercise, all the households that had title deeds at the time of the survey were interviewed. These were 54 from Bauleni and 248 from Madido. The survey commenced with a pilot study to test the data collection instrument. During piloting, each of the four research assistants interviewed two respondents each, a male and a female from among the households with title deeds. Thus, a total of eight interviews were conducted during the pilot study. The pilot study was conducted within a day, at the end of which a debriefing session was held. Some questions in the questionnaire were modified, while a few were removed as they were found to be redundant, and some new ones were added after the feedback from the pilot interviews. The eight interviewees from the pilot study were excluded from the survey.

After the questionnaire survey, two 3-in-1 focus group discussions (FGDs) (March et al., 1999; Umar, 2021) were conducted in the two study sites. The discussants were recruited from the pool of respondents, on the basis of having extensive knowledge of the land titling process. Each of the four enumerators recommended two male, and two female discussants from the batch of respondents each had interviewed from the two study sites.

The discussions were held in two phases. In the first phase, discussions were conducted with men and women separately. The men's FGDs were facilitated by a male researcher while the women's FGDs were facilitated by a female researcher. This initial separation into single gender groups was to minimize any influence of unequal gender relations such as the social and cultural superiority of men to women that could otherwise limit participation in the discussions based on gender norms. The men and women's groups were later brought together in a plenary discussion and asked to present summaries of their group deliberations. The plenary phase of the FGDs resulted in co-production of knowledge by men and women discussants through the detailed discussions that ensued from the single gender group presentations. One member of the research team expertly facilitated the discussion while another observed the proceedings and took notes. The facilitator alternated which group shared its results first. Both facilitator and observer paid attention to the verbal reactions and non-verbal communication of the women to the men's answers, and vice versa. These included voice tone, facial expressions and demeanor. These cues were used to guide the facilitator on whether or not there were disagreements between the two groups, and to probe appropriately (Tecau and Tescasiu, 2015). Four (4) key informants were interviewed. These included a representative from the private entity recruited by the state to implement the National Titling Program, and a spatial planner from the Ministry of Local Government and Housing, with extensive experience in planning who had been seconded to the National Land Titling Program. Others were two key informants with extensive knowledge on land related matters in the two study sites. They were both long term residents of their respective informal settlements and their families had been important players in the establishing of the illegal settlements. Both were also involved in the National Land Titling Program as community representatives. This role entailed communicating community concerns to the government, providing information on undocumented land parcels to the state, and updating community members on program activities.

Free, prior and informed consent (Hanna and Vanclay, 2013) was verbally obtained from all respondents and key informants, all of whom were adults aged over 18 years of age. Permission to record the focus group discussions using digital recorders was sought from the discussants and granted for all the sessions. Approval to conduct the research was granted by ERES Converge IRB, a nationally accredited research ethics clearance organization.

The questionnaire survey data was entered into Microsoft Excel sheets. After the data entry was completed, an accuracy check was conducted by randomly selecting ten percent of the completed questionnaires and comparing them to the data entered about them. The data was then copied to Minitab 18 (Minitab Inc, 2017) and analyzed using basic descriptive statistics such as frequencies, means, standard deviation and two sample Independent T-test. The T-test was used to test the hypothesis that male household heads were older than their female counterparts. The recordings of the FGDs and key informant interviews were transcribed and categorized into themes based on research questions. The themes were sense of tenure security; sense of ownership; decision-making; land inheritance, land related family conflicts; love and trust and threats and opportunities presented by land rights formalization.

Overall, the average age of household heads was 56.4+ (s = 9.8) and 48.5(s = 9.1) in Bauleni and Madido respectively. When disaggregated by the gender of the household head, the data reveals that around 20% of the interviewed households were headed by females; the average age of male household heads in Madido was lower than for the female heads (p < 0.005) while in Bauleni, there was no statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) in the mean ages of the male and female household heads. Almost half (46%) of the respondents reported the housing property owned by a married male household head while a quarter (25.2%) reported joint ownership by husband and wife. Joint ownership by husband and wife entails that both the couple's names are included on the title. The rest reported ownership by female headed households (16.3%) and by wives (11.4%). Female household heads are unmarried (divorced, widowed or single). There were no unmarried male housing property owners in the sample. When disaggregated by study site, the general trend was the same with a few nuances; About 49% and 40% of the housing property owners were male household heads in Madido and Bauleni respectively. Joint ownership was reported in 36% and 23% of the housing properties in Bauleni and Madido respectively. Housing property owned by the wife comprised about 12% of the cases in both study sites, while about 15% and 10% of the housing properties were owned by female household heads. Family owned housing was the least common with only 2% of the properties in Bauleni and 6% in Madido. The rest of this section presents and discusses the findings based on themes derived from the research questions and those emerging from the data collected.

A large majority of the respondents in both study sites thought that women's sense of tenure security had greatly increased (82% for Bauleni and 91% for Madido), while a small percentage (8% for Bauleni and 2% for Madido) thought the increase was only moderate (Figure 3). If feelings of tenure security increase greatly, it means someone feels that it is highly unlikely that someone can arbitrarily expropriate their land. Similarly, if an owner's sense of security of tenure is moderate, it means they feel that it is not so likely that anyone can dispossess them of their property arbitrarily although they may have some lingering feeling that someone might actually do so.

The women FGDs in Bauleni revealed that title deeds were “witnesses” or testimony to land ownership and that in the future no one would take the land away from them or their children because the title deeds would serve as proof of ownership. Similar views were expressed by the women FGDs from Madido. In the words of one focus group discussant, “before we got title deeds, we were very worried. Now we are safe, after getting the title deeds. Now we can expand our houses. We are very secure now.” These views are shared by women that jointly owned their land with their spouses and those from households where only the male household head is included on the title. Noteworthy is that even married women whose names are not included on the title deeds as joint owners enjoy tenure security because of the provisions of the Intestate Act (Chapter 59 of the Laws of Zambia) of 1989 which protects the rights of surviving spouses and children to inherit property. Enhanced tenure security for women after land rights formalization has been reported elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. Some interventions in Uganda (Cherchi et al., 2019), Ethiopia (Bezabih et al., 2016) and Nepal (Mishra and Sam, 2016) showed a notable increase in women's tenure security than was previously held. Such cases notwithstanding, Viña (2020) urges caution. She posits that a woman having title deeds is not a sufficient condition for tenure security as titling may not necessarily translate to decision making about and deriving benefits from the land.

Over 80% of the respondents in both sites believed that men's sense of tenure security had greatly increased after land titling (Figure 3). During the FGDs with men in Bauleni, a contrast was made between tenure security before and after land titling. The men unanimously agreed that before titling, anyone could lay claims on their land, but after titling, this was not possible. They all felt very secure post-titling. Their counterparts from Madido observed that before titling, they had been afraid that their houses could be demolished. The state did not provide any public services to the area because it was considered an illegal settlement. But after titling, “the government has brought water, sewerage and roads. We are proud now. There is just that sense of pride that this is my property”, one of the discussants narrated. These sentiments suggest that land rights offered by title deeds are known to the rights holders and are enforceable. The rights owners knew that their title deeds, and the rights guaranteed therein, were valid for 99 years. This applies for both men and women land rights holders.

A large majority of the respondents reported increases in the sense of ownership for both men and women in both study sites (Figure 4) while a small minority indicated that there was a moderate increase of sense of ownership. The stronger sense of ownership was premised on landowners in both Bauleni and Madido having exclusive rights and control over the land parcels they owned.

This was in line with the results from the FGDs. The focus group discussants from both Madido and Bauleni (men and women's groups) observed that the title deeds have accorded them ownership rights, which they never had before the issuance of title deeds.

They narrated that prior to land rights formalization; anyone could come at any point and grab the land from them. However, with the title deeds issued to them, all focus group discussants confirmed having full ownership rights. They believed that no entity could grab land from them or demolish their properties without compensation. The focus group discussants further noted that land rights formalization has resulted in their empowerment. That is, they have powers to put up and extend immovable structures, because they have secure land rights to their land parcels. Clearly, landowners are able to enforce their rights when under threat as the rights have been legitimized by the state. A similar study from Tanzania conducted by Parsa et al. (2011) reported that most residents with property licenses felt that the municipality was unlikely to carry out demolitions and if conducted they had a better chance of being compensated by the authority.

Having addressed tenure security, the paper proceeds to explore the context under which men and women have gained tenure security and delve into which land rights claimants are able to assert their claims to the secured land rights, how they assert their claims and the conditions under which they do so.

In this section, the paper presents results on social norms obtaining around property in the context of titling. Social norms are defined as “rules of action shared by people in a given society or group; they define what is considered normal and acceptable behavior for the members of that group” (Cislaghi and Leise, 2020). Social norms change from time to time. It would be interesting to know how titling affects some of the social norms in the study sites.

A large proportion (67% and 73%) of the respondents in Bauleni and Madido respectively, and 74% overall claimed that there was an increase in the inheritance rights to property for daughters due to land rights formalization (Figure 5). A minority of the respondents (<20%) indicated that there was no change in inheritance rights to property for daughters post land rights formalization (Figure 5).

In the FGDs debate on land rights inheritance by daughters and sons, some discussants maintained that it was not the best idea to put daughters' names on title deeds because once they got married, they could let their husband take over the property to the detriment of the daughter's siblings. In the words of one male discussant from Bauleni, “For daughters, they can get married and let the man control the property.” Conversely, another discussant from the same group argued for land rights inheritance by daughters, “It is better for a girl child to get inheritance because as the boy gets married and dies, his widow will inherit the property.” This sentiment was echoed by discussants from Madido. One discussant elaborated the following:

Girl child should be on a title deed. Even when the girl child gets married and it happens that the marriage does not work out, the daughter can go back to the house unlike the boy child because when he marries and dies, his wife will inherit the house [Focus Group Discussion, Madido, Zambia 20th October 2020].

Nancekivell et al. (2013) shared this view when they contended that a girl child should be on title because even if she were to get married, she could still look after the property and in cases where the marriage failed to work out, she could go back to the property. Almost 90% of the respondents perceived rights to inherit housing property to have increased due to land rights formalization (Figure 6).

During focus group discussions, a lot of skepticism was expressed about sons inheriting property rights to land. The discussants averred that sons could sell the land and chase their siblings. This excerpt typifies this sentiment among Bauleni discussants, “It is best not to put [include] sons on a title because they can sell the land and chase their siblings.” A similar view from Madido, “A son may even let the wife control and chase away siblings”. The focus group discussants from Madido and Bauleni residential areas expressed strong preferences for including all the children on the title deeds so that no single child could change the land ownership.

Half of the respondents from Bauleni and forty percent from Madido claimed that there was no change in the inheritance rights to property for nephews after land rights formalization (Figure 7). About ten percent of the respondents in both areas thought there had been an increase while the rest viewed the rights to have decreased. Similar sentiments were expressed for nieces (Figure 8). The explanations for these results were provided during the focus group discussions.

The discussants contended that adding nephews and nieces' names on title deeds was problematic because their (the nephews and nieces) parents could later claim the land parcels as theirs. The following verbatim represent this view from a Bauleni discussant, “Putting names of nephews or nieces may result in problems because their parents may come to make claims”

Both respondents and focus group discussants noted that only biological children had inheritance rights and should be the only ones included as land rights claimants on title deeds, besides the parents. This norm was a measure to prevent land claims from extended family members.

Either one name or more can be on a title deed. The key beneficiaries are the children, biological children, and no one can claim the land from them [Focus group discussant, Madido, Zambia, 20th October, 2020].

Gibson and Walrath (1947) in Iowa of the United States of America also made this observation when they noted that the inheritance of property rights by nephews such as inheriting the house, farmland or plot following the death of the owner of the property was perceived negatively. Normally, when nephews inherit property rights, it is very likely that their biological parents may claim it is their property when in the actual sense it is not (Gibson and Walrath, 1947). In Rwanda, the land registration and titling program, implemented alongside the 1999 Law of Succession, and the National Land policy of 2004 resulted in; (i) increased inheritance rights of daughters similar to sons, (ii) permanent land rights for divorced or widowed women, and (iii) increased ability to resist restrictive customary practices, e.g. polygamy, where wives property rights were not recognized by the state (Ansoms and Holvoet, 2008; Daley et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2014; Kagaba, 2015).

Decision-making is an indicator of control. Being able to exercise agency over what happens to land suggests an acceptance as part (owner) with rights and /or interest in the property. Decision making over land is influenced by social norms over who is considered a legitimate decision maker. In both study sites, about 32% of the women respondents noted that the acquisition of land titles had greatly increased the decision-making authority of land owners while 15% noted a moderate increase (Figure 9).

For the men, 22% perceived decision making authority to have greatly increased among titled land owners, while 17% thought the increase was moderate, in both study sites. About 5% of the male respondents in both study sites asserted that decision making had moderately decreased while <1% of the women thought so, in both study sites (Figure 9). Close to half (45 %) of all respondents did not attribute any changes in the decision- making authority to acquisition of title deeds.

Despite few respondents citing increased decision-making authority, FGDs revealed that the acquisition of title deeds facilitates for men and women household heads to acquire financial loans using titles as collateral and enables them to decide who should inherit their property. Further, discussants noted that title deeds provide men and women household heads legal ownership and consequently authority to invest in their properties thereby increasing the monetary worth of the properties. Land formalization programs implemented across sub-Saharan Africa show positive outcomes in securing property rights and upholding equality across both genders. In Rwanda, equal decision-making rights between formally registered spouses to alienate property and rights to earn independent incomes through private property were reported (Kagaba, 2015). Agarwal and Panda (2007) noted that establishing women's property rights empowers them with decision making authority and enhanced control over resources and ensures the welfare of their households. Titling, however, must be supplemented with ancillary empowering interventions for women (see Monterroso et al., 2019). As Viña (2020) avers, focusing on titling alone “without addressing the persistent barriers faced by women, not only misses the mark, but could also end up being counterproductive”

Some scholars have argued that the presence of a title does not guarantee access to financial credit to residents, i.e., men and women especially in low-income areas citing low value of most properties as well as unwillingness by financial institutions to offer loans (Rakodi, 2014). However, these negative outcomes are unlikely to apply to residents of our study sites as they are in the city and title is for individualized housing units unlike the case of rural communal pasture or bargaining.

Focus group discussants from both study sites articulated that tenure insecurity among informal settlement landowners without formalized land rights is high, with evictions and demolitions pervasive threats. They asserted that the land reforms to regularize land ownership presents an opportunity for informal area residents to secure their land rights and make them enforceable and easily transferable. Scholars have observed that land titling is not without threats. Informal settlements expand unexpectedly and ultimately lead to a change in the use of space and structure of activities, in ways not in conformity with land use planning and legal requirements and may cause contradictions and conflicts (Dadashpoor and Ahani, 2019).

Intra-family tensions and contestations are reported over bequest, usage, or sharing of land (see Wong, 1998; Kouamé, 2011; Gyapong, 2021). As Wong notes, disputes among spouses or family members can arise from deteriorating family relations such as a marriage breakdown or from third parties making counterclaims to the property. This study therefore sought to find out, in part, how land tilting had affected internal family relations in terms of conflicts related to land. The conflicts manifested in a number of ways in the two study sites including verbal quarrels and cutting of family ties. Just over half (54%) of the respondents in Bauleni indicated that land rights formalization had not influenced land-related family conflicts. This is compared to below half (43.5%) of Madido respondents. Interestingly, only <10% (9%) of respondents in Bauleni indicated a decrease in land related conflicts among family members while about a third (31%) of Madido said land related family conflicts had decreased.

In both study sites, <10% reported that land related family conflicts had increased following titling; seven and eight per cent for Bauleni and Madido respectively. On whether land related family conflicts had increased moderately only 11% and 10% responded in the affirmative for Bauleni and Madido, respectively. Overall, 18 and 19% of respondents from Bauleni and Madido, respectively, reported a moderate or great increase in land related family conflict following titling of their land. While tenure for agricultural land for women has been associated with women empowerment and reduced gender-based violence in India, the scarcity of land has resulted in tensions between spouses in Kenya over prioritization of consumption crops or commercial crops (Andersson Djurfeldt, 2020).

According to Rukema and Khan (2019), family conflicts in Rwanda relating to land are sparked by polygamy with competing inheritance claims from the various wives and their children. However, in Zambia, polygamy is illegal under statutory law and though legal under customary law, polygamy is rare in urban areas. In both Madido and Bauleni, no polygamous marriage was reported by respondents. The other causes of land-related conflicts Rukema and Khan (2019) cite are illiteracy and ignorance of the law empowering women with land ownership. Our study revealed a case where the husband had deserted the wife and children to go and live with another woman carrying the land title with him. One woman in Bauleni, a teacher by profession, reported contributing toward the land title. However, the husband had been elusive, giving contradictory claims that he had received the title and denying this when contacted by the wife during the interview.

Love and trust between spouses can potentially be affected by titling with land being more marketable or being used as collateral, for instance. Furthermore, titling could mean adding both spouses on the title deed as co-owners. Over half (52%) of the respondents in Bauleni and only 37% in Madido said the love and trust for their spouse had not changed after obtaining title deeds. In both areas very few reported a decrease in their love and trust toward a spouse, that is, <1%. A third of respondents in Bauleni stated that their love and trust for their spouse had increased modestly or greatly while 41% said so in Madido. Overall, the vast majority of respondents in both areas indicated an improvement or no change (Madido 81%; Bauleni 89%) in their trust and love toward the spouse. Interestingly, seventeen respondents in Madido claimed not to know how or whether titling had affected their spousal relationship compared to none being not sure in Bauleni.

There is a risk that legalizing and formalizing land rights to illegally settled land could provide perverse incentives for new land encroachments. In Bauleni, authorities bypassed regulations about plot size, and distance from public infrastructure such as roads and water pipes in numerous cases (Figure 10) during the surveying and subsequent titling process.

Figure 10. Titled houses situated less than a meter from a public drainage channel and road, Bauleni Lusaka.

Furthermore, the legalization of settlement on land that previously belonged to a public college in the case of Madido could motivate future illegal settlements of public land in the expectation of future regularization. Chitonge and Mfune (2015) cited the illegal allocation of idle and vacant public or private land by political party cadres as important in the creation of informal settlements in Lusaka city.

Landowners are now “visible” to the state, in that they can use their title deeds as proof of residence, a requirement in accessing numerous services provided by both the public and private sector. For example, in order to open a bank account with a formal banking institution, proof of residence is required. Before the acquisition of title deeds, residents had no way of providing this proof. Land rights formalization has spurred increased participation in local development initiatives, such as through ward development committees. This increased participation is positive for local area development as residents are able to articulate issues of interest to them.

Local political players were cardinal in the mobilization of residents. In Madido, the clique of ruling party officials that had appropriated land from the college and sold it were engaged to help the technocrats liaise with the community. Due to the illegal way in which the land had been obtained, residents had lived with the threat of eviction and were very apprehensive about any land related discussions. The land sellers were instrumental in providing confirmation of landowners in the numerous cases where proof of sale was missing. They worked hard to assure the community members that the initiative was genuinely meant to provide title deeds to them and was not an eviction exercise. Local political elites have been influential in illegal land allocations in Zambia (Chitonge and Mfune, 2015). During fieldwork, one of them admitted that, “it is not possible for the state to remove people from illegally occupied land, once the land has been allocated by political cadres. That would not auger well for the ruling party. All the state can do is provide public services such as water, schools, clinics and roads”. Residents tended to publicly align themselves with party officials of the ruling party or those they knew to be influential in local community development structures as a way to protect their interests. This has engendered patron-client relationships between residents and local political party officials on one hand, and local party officials and higher level politicians and technocrats. Local party officials have been known to usurp the authority of local development officials and technocrats in matters of land administration. This usurpation has been demonstrated in the collection by political cadres of tax that should be collected by local authorities as revenue for service delivery (Beardsworth et al., 2022). There is a risk that the national land titling program may be overtaken by political elements if this clientelism is not addressed.

Our research indicates that the issuance of title deeds is faster since Medici Land Governance became involved than was the case with the pilots under the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources. Interviews with key informants revealed that Medici Land Governance is more efficient because it makes use of geographical information systems and uses block chain technology and is able to get title deeds issued in batches, unlike the traditional Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources system which provides approval per parcel. This is an opportunity for streamlined issuance of title deeds with potential to handle the land volumes expected once the program is fully fledged.

This study set out to examine how land rights formalization has affected land tenure security, sense of ownership, decision making, land conflicts, love and trust among men and women landowners in two study areas in Lusaka, Zambia. Our research findings show that the ongoing land rights formalization program in Zambia has provided land tenure security for residents of informal settlements that previously lived under constant threat of eviction from their land. Both men and women have similarly benefitted from the formalization initiative through land laws and local norms that allow equitable access to land and land inheritance. Ownership rights and decision making has also been enhanced among both men and women landowners in the two study sites as they can easily alienate their property. Land rights formalization has in some instances curtailed land rights for secondary claimants such as extended family members, in preference for man, spouse and biological children. This is in line with the majority of the respondents in both study areas who were of the view that only the spouse or biological children's names should be on the title deed and have the right to inherit the property. The process of formalizing land rights in informal settlements has entailed putting aside regulations on plot boundary specifications and plot locations; essentially the legalization of illegalities to achieve the states goals of providing land tenure security to poor urbanites who would not otherwise have recourse to legal or regularized land. The study commends the initiative as a pro-poor initiative that is enabling socially marginalized groups to access legal land documentation and become visible in urban landscapes that have historically not catered for their land and housing needs.

As the National Titling Program is expanded to other districts, implementers should develop robust mechanisms for keeping track of the payments made by program beneficiaries through their community municipality offices such as a short messaging system to send alerts whenever payments are made. The messages should include information on the amount paid and balance remaining. Program implementers should also continue to improve on the time between initial payments and issuance of title deeds. Policy makers are cautioned not to incentivize illegal land allocations by not extending the initiative to areas illegally occupied after the start of the program.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conceptualization, visualization, project administration, funding acquisition, and methodology: BB. Validation: JK, KK, LS, and DM. Formal analysis, investigation, and writing: BB, JK, KK, LS, and DM. Supervision: BB and JK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research (PEER) Program.

The authors thank Garikai Membele for the technical support in making the map and Progress Nyanga for various contributions to the project. BB thanks the Nordic Africa Institute for the Africa Scholars Program fellowship during which the manuscript was drafted.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agarwal, B., and Panda, P. (2007). Toward freedom from domestic violence: the neglected obvious. J. Hum. Develop. Capabil. 8, 359–388. doi: 10.1080/14649880701462171

Ali, D. A., Deininger, K., Hilhorst, T., Kakungu, F., and Yi, Y. (2019). “Making sure land tenure counts for millennium development goals and national policy: evidence from Zambia,” in Policy Research Working Paper 8912 (The World Bank, Washington, DC). doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-8912

Andersson Djurfeldt, A. (2020). Gendered land rights, legal reform and social norms in the context of land fragmentation—a review of the literature for Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. Land Use Policy 90, 104305. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104305

Andersson Djurfeldt, A., and Sircar, S. (2018). Gendered land rights and access to land in countries experiencing declining farm size. AgriFoSe2030 Rep. 6, 2018.

Ansoms, A., and Holvoet, N. (2008). “Women and land arrangements in Rwanda,” in Englert, Daley, eds, Women's Land Rights and Privatization in Eastern Africa (James Currey Fountain Publishers, EAEP, E and D Vision Publishing, Woodbridge, Kampala, Nairobi, Dar es Salaam), p. 138–157. doi: 10.1017/9781846156809.009

Beardsworth, N., Cheelo, C., Hinfelaar, M., Mutuna, K., and Shicilenge, B. (2022). Study on Political Cadres and Financial Sustainability of Local Authorities. Discussion Paper Series No. 6. Southern African Institute for Policy and Research.

Benjaminsen, T. A. (2002). Formalising land tenure in rural Africa. Forum Develop. Stud. 29, 362–366. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2002.9666212

Benjaminsen, T. A., Holden, S., Lund, C., and Sjaastad, E. (2009). Formalisation of land rights: some empirical evidence from Mali, Niger and South Africa. Land Use Policy 26, 28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.07.003

Besley, T. (1995). Property rights and investment incentives: Theory and evidence from Ghana. J. Pplit. Econom. 103, 903–937.

Bezabih, M., Holden, S., and Mannberg, A. (2016). The role of land certification in reducing gaps in productivity between male- and female-owned farms in Rural Ethiopia. J. Develop. Stud. 52, 360–376. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2015.1081175

Bezu, S., and Holden, S. (2014). Are rural youth in Ethiopia abandoning Agriculture? World Dev. 64, 259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013

Central Statistical Office (2013). 2010 Census of Population and Housing: Population and Demographic Projections. Lusaka: CSO.

Cherchi, L., Goldstein, M., Habyarimana, J., Montalvao, J. O'Sulli-van, M., Udry, C., and Gruver, A. (2019). Empowering Women Through Equal Land Rights: Experimental Evidence From Rural Uganda. Gender Innovation Lab Policy Brief; No. 33. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/31513

Cheyeka, A., Hinfelaar, M., and Udelhoven, B. (2014). The changing face of Zambia's Christianity and its implications for the public sphere: a case study of Bauleni township. Lusaka J. Southern Afr. Stud. 40, 1031–1045. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2014.946228

Chirwa, E. W. (2008). Land Tenure, Farm Investments and Food Production in Malawi, Research Programme Consortium on Improving Institutions for Pro-Poor Growth. Department for International Development.

Chitonge, H., and Mfune, O. (2015). The urban land question in Africa: the case of urban land conflicts in the City of Lusaka, 100 years after its founding. Habitat Int. 48, 209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.03.012

Cislaghi, B., and Leise, L. (2020). Gender norms and social norms: differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociol. Health Illness 42, 407–422. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13008

Dadashpoor, H., and Ahani, S. (2019). Land tenure-related conflicts in peri-urban areas: a review. Land Use Policy 85, 218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.03.051

Daley, E., Dore-Weeks, R., and Umuhoza, C. (2010). Ahead of the game: land tenure reform in Rwanda and the process of securing women's land rights. J. Afr. Stud. 4, 131–152. doi: 10.1080/17531050903556691

De Soto, H. (2000). The Mystery of Capital. Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. Basic Books. New York.

Di Tella, R., Galiani, S., and Schargrodsky, E. (2007). The formation of beliefs: Evidence from the allocation of land titles to squatters. Q. J. Econom. 122, 209–241. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25098841

Doss, C., and Meinzen-Dick, R. S. (2018). Women's Land Tenure Security: A Conceptual Framework. Seattle, WA: Research Consortium. Available online at: https://consortium.resourceequity.org/conceptual-framework

Durand-Lasserve, A., and Selod, H. (2007). The Formalisation of Urban Land Tenure in Developing Countries. World Bank's 2007 Urban Research Symposium, May 14–16. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Durand-Lasserve, A., and Selod, H. (2009). “The formalization of urban land tenure in developing countries,” in Urban Land Markets Improving Land Management for Successful Urbanization, eds S. V. Lall, M. Freire, B. Yuen, R. Rajack, and J. Helluin (New York, NY: Springer).

Field, E. (2007). Entitled to work: Urban property rights and labor supply in Peru. Q. J. Econom. 122, 1561–1602. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25098883

Ghebru, H., and Holden, S. T. (2015). Technical efficiency and productivity differential effects of land right certification: A quasi-experimental evidence. Q. J. Int. Agri. 54, 1–31.

Ghebrua, H., and Lambrecht, I. (2017). Drivers of perceived land tenure (in)security: empirical evidence from Ghana. Land Use Policy, 66, 293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.04.042

Gibson, W. L., and Walrath, A. J. (1947). Inheritance of farm property. J. Farm Econ. 29, 938–951. doi: 10.2307/1232630

Government of the Republic of Zambia (2021a). National Land Policy. Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources. Lusaka.

Government of the Republic of Zambia (2021b). National Titling Programme. Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources. Available online at: https://www.mlnr.gov.zm/?page_id=3230 (accessed September 8, 2021).

Government of the Republic of Zambia, (2018). Ministerial statement on the implementation of the national titling programme by the Hon. Minister of Lands and Natural Resources. Lusaka: MLNR. Available online at: https://www.parliament.gov.zm/node/7713

Gyapong, A. Y. (2021). Commodification of family lands and the changing dynamics of access in Ghana. Third World Q., 42, 1233–1251. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2021.1880889

Hanna, P., and Vanclay, F. (2013). Human rights, indigenous peoples and the concept of free, prior and informed consent. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal 31, 146–157. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2013.780373

Hansen, K. (1982). Lusaka's squatters: Past and present. Afr. Stud. Rev. 25, 117–136. doi: 10.2307/524213

Holden, S., Deininger, K., and Ghebru, H. (2011). Tenure insecurity, gender, low-cost land certification and land rental market participation in Ethiopia. J. Develop. Stud. 47, 31–47. doi: 10.1080/00220381003706460

Holden, S. T., and Otsuka, K. (2014). “The roles of land tenure reforms and land rental markets in the context of population growth and land use intensification in Africa.” Food Policy, 48, 88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.03.005

Jimenez, E. (1984). Tenure security and urban squatting. Rev. Econom. Statist. 66, 556–567. doi: 10.2307/1935979

Kagaba, M. (2015). Women's experiences of gender equality laws in rural Rwanda: the case of Kamonyi District. J. Eastern Afr. Stud. 9, 574–592. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2015.1112934

Kim, H-. S., Yong, Y., and Mutinda, M. (2019). Secure land tenure for urban slum-dwellers: a conjoint experiment in Kenya. Habitat. Int. 93, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102048

Knight, R. S. (2010). Statutory Recognition of Customary Land Rights in Africa: An Investigation into Best Practices for Lawmaking and Implementation (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Legislative Study No. 105). Rome, Italy. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/3/i1945e/i1945e00.pdf (accessed September 10, 2021).

Kouamé, G. (2011). Intra-family and socio-political dimensions of land markets and land conflicts: the case of the abure. Côte d'Ivoire. 80, 126–46. doi: 10.3366/E0001972009001296

Kyalo, W. D., and Chiuri, W. (2010). New common ground in pastoral and settled agricultural communities in Kenya: renegotiated institutions and the gender implications. Europ. J. Develop. Res. 22, 733–750. doi: 10.1057/ejdr.2010.43

Lawry, S., Samii, C., Hall, R., Leopold, A., Hornby, D., and Mtero, F. (2014). The impact of land property rights interventions on investment and agricultural productivity in developing countries: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2014:1. doi: 10.4073/csr.2014.1

Lemanski, C. (2011). Moving up the ladder or stuck on the bottom rung? Homeownership as a solution to poverty in urban South Africa. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 35, 57–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00945.x

Lombard, M., and Rakodi, C. (2016). Urban land conflict in the Global South: Towards an analytical framework. Urban Stud. 53, 2683–2699. doi: 10.1177/0042098016659616

Makumba, C. P. (2019). Enabling Approaches to the Upgrading of Informal Settlements: A Case Study of Misisi Compound in Lusaka, Zambia. Master's Thesis. Department of Urban and Regional Planning. University of the Free State, South Africa.

March, C., Smyth, I., and Mukhopadhay, M. (1999). A Guide to Gender Analysis Frameworks. Oxfam: Oxford. doi: 10.3362/9780855987602

Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources. (2021). National Titling Programme (https://mlnr.gov.zm). (accessed June 6, 2021).

Mishra, K., and Sam, G. A. (2016). Does women's land ownership promote their empowerment? Empirical evidence from Nepal. World Develop. 78, 360–71. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.003

Monterroso, I., Larson, A., Mwangi, E., Liswanti, N., and Cruz-Burga, Z. (2019). Mobilising Change for Women within Collective Tenure Regimes. Available at Mobilizing Change for Women Within Collective Tenure Regimes (resourceequity.org).

Msimang, Z. (2017). A Study of the Negative Impacts of Informal Settlements on the Environment: A Case Study of Jika Joe, Pietermaritzburg. (Master's Dissertation): University of KwaZulu Natal.

Muanda, C., Goldin, J., and Haldewang, R. (2020). Factors and impacts of informal settlements residents' sanitation practices on access and sustainability of sanitation services in the policy context of Free Basic Sanitation. J. Water Sanitat. Hygiene Develo. 10, 238–248. doi: 10.2166/washdev.2020.123

Nancekivell, S. E., Van de Vondervoort, J. W., and Friedman, O. (2013). Young children's understanding of ownership. Child Dev. Perspect. 7, 243–247. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12049

Nchito, W. S. (2007). Flood risk in unplanned settlements in Lusaka. Environ. Urban. 19, 539–551. doi: 10.1177/0956247807082835

Nixon, B. (2020). Assessing the environmental impacts of informal settlements in Vietnam: the case study of the hue citadel UNESCO world heritage. Int. J. Environ. Impacts 3, 189–206. doi: 10.2495/EI-V3-N3-189-206

Parsa, A., Nakendo, F., McCluskey, W. J., and Page, M. W. (2011). Impact of formalization of property rights in informal settlements: evidence from Dar es Salaam city. Land Use Policy 28, 695–705. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.12.005

Payne, G. (1997). Urban Land Tenure and Property Rights in Developing Countries: A Review. London: IT Publications/ODA. p. 1–73.

Payne, G., Durand-Lasserve, A., and Rakodi, C. (2009). The limits of land titling and home ownership. Environ. Urban. 21, 443–462. doi: 10.1177/0956247809344364

Place, F. (2009). Land tenure and agricultural productivity in Africa: A comparative analysis of the economics literature and recent policy strategies and reforms. World Develop. 37, 1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.020

Rakodi, C. (2014). Gender equality and development: expanding women's access to land and housing in urban areas. Women's Voice Agency Res. Ser. 8, 1–56.

Reerink, G., and van Gelder, J. L. (2010). Land titling, perceived tenure security, and housing consolidation in the kampongs of Bandung, Indonesia. Habitat Int. 34, 78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.07.002

Rukema, R. J., and Khan, S. (2019). “Land tenure and family conflict in Rwanda: Case of Musanze District,” in Trajectory of Land Reform in Post-Colonial African States. Advances in African Economic, Social and Political Development, eds A. Akinola and H. Wissink (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78701-5_11

Sagashya, D., and Tembo, E. (2022). Zambia: Private sector investment in security of land tenure—from piloting using technology to National rollout. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospatial Sci. 5, 31–49. doi: 10.48346/IMIST.PRSM/ajlp-gs.v5i1.30440

Santos, F., Fletschner, D., and Daconto, G. (2014). Enhancing inclusiveness of Rwanda's Land Tenure Regularization Program: insights from early stages of its implementation. World Dev. 62, 30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.04.011

Simwanda, M., Murayama, Y., and Ranagalage, M. (2020). Modeling the drivers of urban land use changes in Lusaka, Zambia using multi-criteria evaluation: an analytic network process approach. Land Use Policy 90, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104441

Sjaastad, E., and Bromley, W. D. (1997). “Indigenous land rights in sub-Saharan Africa: appropriation, security and investment demand.” World Develop. 25, 549–62. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(96)00120-9

Sjaastad, E., and Cousins, B. (2008). Formalization of land rights in the South: an overview. Land Use Policy 26, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.05.004

Smith, R. (2001). “Land Tenure, Title Deeds, and Farm Productivity in the Southern Province of Zambia: Preliminary Research Findings (Outline)” in Development Studies Dept. School of Oriental and African Studies, Russell Square (London, UK).

Sommerville, M., and Tembo, E. (2019). Land Tenure Dynamics in Peri Urban Zambia. USAID. Available online at: https://urban-links.org/land-tenure-dynamics-in-peri-urban-zambia/.

Taylor, T. K., Banda-Thole, C., and Mwanangombe, S. (2015). Characteristics of House Ownership and Tenancy Status in Informal Settlements in the City of Kitwe in Zambia. Am. J. Sociol. Res. 5, 30–44. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20150502.02

Tecau, A. S., and Tescasiu, B. (2015). Non-verbal communication in the focus-group. Transilvania Univ. Brasov. 8, 119–24.

Tembo, E., Minango, J., and Sommerville, M. (2018). “Zambia's National Land Titling Programme- challenges and opportunities,” in Paper presented at 2018 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty (Washington, DC). Available online at: https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Session-06-05-Tembo-153_paper.pdf (accessed March 14, 2023).

Tidwell, J. B., Chipungu, J., Chilengi, R., Curtis, V., and Aunger, R. (2019). Theory-driven formative research on on-site, shared sanitation quality improvement among landlords and tenants in periurban Lusaka, Zambia. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 29, 312–325. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2018.1543798

Toulmin, C. (2009). Securing land and property rights in sub-Saharan Africa: the role of local institutions. Land Use Policy 26, 10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.07.006

Tura, H. A. (2014). A woman's right to and control over rural land in Ethiopia. Int. J. Gender Women Stud. 2, 137–165.

Umar, B. B. (2021). Adapting to climate change through conservation agriculture: a gendered analysis of Eastern Zambia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 748300. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.748300

Viña, S. C. (2020). Beyond Title: How to Secure Land Tenure for Women. Available online at: How to Secure Land Tenure for Women | World Resources Institute (wri.org)

Wily, L. A. (2017). “Customary tenure: remaking property for the 21st century,” in Graziadei, M., and Smith, L., Comparative Property Law: Global Perspectives, p. 458–77. doi: 10.4337/9781785369162.00030

Wong, S. (1998). Constructive trusts over the family home: lessons to be learned from other Commonwealth jurisdictions? Legal Stud. 18, 369–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-121X.1998.tb00023.x

Keywords: Bauleni, Madido, national land titling program, title deeds, land rights, land rights formalization

Citation: Bwalya Umar B, Kapembwa J, Kaluma K, Siloka L and Mukwena D (2023) Legalizing illegalities? Land titling and land tenure security in informal settlements. Front. Sustain. Cities 5:922419. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.922419

Received: 17 April 2022; Accepted: 30 March 2023;

Published: 27 April 2023.

Edited by:

Andrew Adewale Alola, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, NorwayReviewed by:

Method Gwaleba, Ardhi University, TanzaniaCopyright © 2023 Bwalya Umar, Kapembwa, Kaluma, Siloka and Mukwena. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bridget Bwalya Umar, YnJpZ3QyMDAxQHlhaG9vLmNvLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.