- 1Department of Urban Land Development and Management, CUDE, Ethiopian Civil Service University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 2Department of Urban and Regional Planning, EiABC, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Bahir Dar, a city in Ethiopia, is grappling with the challenges of rapid urbanization, which has made affordable housing a critical issue for its growing population. This study specifically focuses on the urban land acquisition process for cooperative housing schemes, which serve as an essential component of Bahir Dar’s affordable housing program. This atudy aimed to examine the current practices, identify the challenges faced by housing cooperatives during land acquisition and construction, and propose strategies for improvement. The primary data for this research were collected through interviews with key informants from the Bahir Dar City administration’s land management, cooperative organizer office, housing development and management office, and housing cooperative committees. Additionally, three focus group discussion (FGD) sessions were conducted, involving 21 participants from cooperative members who had acquired residential land and from those who were waiting for allocation, including both female- and male-headed households. These discussions explored their views on the effectiveness of the cooperative housing scheme, the challenges encountered during cooperation and construction, and their recommendations for enhancement. Secondary data were also gathered through a comprehensive review of policies, regulations, research articles, reports, and relevant legal documents. The study revealed that, out of the 35,512 certified housing cooperative members since 2014, only 31,596 of them had received residential land plots. However, a relatively small fraction, i.e., less than 7,000 cooperative members, managed to partially or fully construct their homes. This indicates that the scheme has not fully achieved its intended goal and remains unaffordable for many members. The main challenges faced by cooperative members include lengthy delays in obtaining serviced land, high construction costs, and unrealistic building standards for cooperative housing units. In light of these findings, it is recommended that the Amhara National Regional State revise its housing cooperative policy to become affordable for cooperative housing members, particularly in terms of land acquisition costs and building standards.

1 Introduction

In developing countries, rapid urbanization, population growth, and inadequate housing supply have led to a large and growing demand for affordable housing (UN-Habitat, 2011). This gap is significantly affecting low-income households who have limited financial resources. Many low-income households live in informal settlements or slums, where living conditions are often poor, and basic services, such as clean water and sanitation, are lacking (Keller and Mukudi-Omwami, 2017; Sengupta et al., 2018; Larsen et al., 2019). Governments in such countries usually lack the resources and institutional capacity to provide affordable housing to their citizens, leading to a reliance on the private sector to meet the demand for housing.

As one of the developing regions of the world, in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, urbanization is a growing trend, with a large number of people moving from rural areas to cities in search of better economic opportunities and access to basic services such as healthcare and education (UN-Habitat, 2011). However, this rapid urbanization has led to a shortage of affordable housing, which is a major challenge in the region (UN-Habitat, 2011; Makinde, 2014; Agyemang and Morrison, 2018; CAHF, 2019). One reason for the shortage of affordable housing in the region is the lack of investment in the construction of low-cost housing units. The studies concluded that most developers focus on building high-end properties that cater to the needs of the middle and upper class, leaving the majority of the population unable to access affordable housing. Moreover, many countries in the region, including Ethiopia, lack comprehensive policies on land acquisition for housing, leading to unclear legal frameworks and a lack of transparency in the land acquisition process (Toulmin, 2009; UN-Habitat, 2011; Arjjumend and Seid, 2018; Lamson-Hall et al., 2019; Larsen et al., 2019). Another significant factor is the high cost of land in urban areas resulting from the alarmingly high demand of serviced land for housing and its limited supply (Berto et al., 2020; Yimam et al., 2022). Hence, land prices have skyrocketed in recent years, making it increasingly difficult for developers to acquire land for affordable housing (UN-Habitat, 2011; Yimam et al., 2022). Additionally, many urban areas in sub-Saharan Africa lack adequate infrastructure, such as roads, energy, water, and sanitation facilities, making land acquisition and development even more challenging (Brown-Luthango, 2010; Makinde, 2014; CAHF, 2019; Liu et al., 2023).

Although the urban housing problem has stayed prevalent, the historical approach to addressing housing problems among low-income urban residents of the world has evolved over time, with multiple modes of housing provision. Anna Kajumulo (2013) identifies four distinct periods in the evolution of low-income housing strategies in urban areas. The first period, spanning from the 1950s to the 1960s, was characterized by a modernization and urban growth approach. During this phase, the primary focus was on shelter production by public agencies, including slum clearance and direct housing construction. However, the housing demand in most developing countries remained unmet, resulting in the second period, spanning from the 1970s to the 1980s, being a growth and distribution phase. Here, the emphasis shifted toward self-help housing, prioritizing upgrades over clearance, and the provision of serviced land. The third period, from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s, was known as the enabling approach phase. This phase focused on empowering self-builders through housing mortgage finance and market facilitation, emphasizing public–private partnerships for housing development. The fourth and current period, beginning in the mid-1990s, signifies a sustainable development phase with a focus on equity and sustainability. Here, housing is considered a means to alleviate poverty, highlighting the importance of addressing housing challenges within the broader context of sustainable development. Except for the initial phase, which primarily emphasized public-led housing provision, the subsequent three phases have placed a strong emphasis on self-help housing strategies as a means to address the housing challenges faced by urban residents.

As one of the dominant options of self-help housing provision, housing cooperatives play a pivotal role in achieving the overarching objective of providing adequate shelter for their members through three fundamental functions (CHF International, 2002; UN-Habitat, 2002; Çelik et al., 2018). These include enabling households to collectively pool their resources for the acquisition and development of land and housing, facilitating access to financial resources, and empowering groups to collaborate, effectively reducing construction costs. It serves as an essential means of housing provision for low- and middle-income groups. Many sub-Saharan countries relied on self-help cooperative housing for affordable housing options for their low- and middle-income families (Ayedun et al., 2017; Paradza and Chirisa, 2017; Cabré and Andrés, 2018). In such schemes, middle- to low-income residents of urban areas come together and make cooperatives by pooling their resources and labor with cooperation with banks and the local government for the land supply and housing finance, respectively. For instance, according to the study of Feather and Meme (2019), the cooperative members in Kenya are responsible for saving 30% of housing development, including the cost of the land, and then, the remaining 70% is covered by the loan with minimal interest for a long period from the bank.

Many studies have been conducted to show the state of affordable housing provision by housing cooperative modality and the way urban land is acquired across Africa (Owoeye and Adedeji, 2015; Agyemang and Morrison, 2018; Kieti et al., 2018; Oyalowo et al., 2018; Adegun and Olusoga, 2019; Kavishe and Chileshe, 2019). The studies expose the idea that there is inefficiency in urban land acquisition for low-income earners, although there are some policies in support of the issue. Cooperative housing is used as a viable option to deliver land for low- and middle-income countries, such as Angola, Nigeria, Kenya, and Zimbabwe, with slightly different approaches to land acquisition (Obodoechi, n.d.; Muchadenyika, 2015; Cain, 2017; Paradza and Chirisa, 2017; Adegun and Olusoga, 2019; Feather and Meme, 2019). According to Cain (2017), in Angola, from 1966 to the present, many public employees and military men have benefitted from the cooperative housing scheme. Under the scheme, the cooperative members’ housing finance is borrowed interest-free from the government and is subjected to contributions from their monthly salary. The government is also responsible for providing free serviced land. On the other hand, Nigeria considered cooperative housing as a poverty reducing option, by which the members get serviced land from the government and housing finance from saving and credit institutions (Obodoechi, n.d.; Ayedun et al., 2017; Adegun and Olusoga, 2019). Moreover, Zimbabwe is one of the African countries that consider cooperative housing as the best and simplistic way of getting urban housing by which the government fulfills its responsibility of organizing for the low and middle income populations home demands in housing cooperatives and of providing serviced land with supervision of the construction material supply and process (Paradza and Chirisa, 2017). According to UN-Habitat (2011), Kieti et al. (2018), and Feather and Meme (2019), the government of Kenya similarly takes cooperative saving for housing as one of the affordable housing options.

Indeed, the Ethiopian government, under the socialist regime known as “Derg,” played a pivotal role in promoting large-scale cooperative housing. According to Abdie (2012), the then-cooperative housing scheme encompassed the provision of land, financing, building materials, organizational expertise, education, and training to cooperatives. The Housing and Savings Bank, which is now the Construction and Business Bank, served as the primary source of financial assistance for housing cooperatives. The cooperative housing supply saw an increase due to controlled material prices, the allocation of land without charges, and low mortgage interest rates set at 4.5%. Although subsidized cooperatives were unable to fully meet the housing needs of a substantial number of low-income households in the country, they managed to produce 40,539 housing units between 1975 and 1992. Hence, the above studies revealed that cooperative housing has been considered a viable option for affordable housing in African countries. The above studies showed cooperative housing as an affordable housing option that involves the cooperative members and the government cooperation mainly in housing finance and serviced land provision.

Similar to many other developing countries, the rapid urbanization and population growth in Ethiopia have resulted in a housing crisis and an acute demand for serviced land (Larsen et al., 2019; Fitawok et al., 2020; Teklemariam and Cochrane, 2021). According to projections made by the World Bank, Ethiopia’s urban population is expected to increase significantly between 2012 and 2032 (World Bank and Government of Ethiopia, 2015, 2019). The urban population of 2012, which was 17.4%, is expected to rise by 30% at an annual growth rate of 5.4% in 2030. This would result in a nearly threefold increase in the population of Ethiopia’s cities, from 16 million to over 42 million people, during the specified time frame (CSA, 2013a; UNDESA, 2015; World Bank and Government of Ethiopia, 2015). To cope with the demand for land of the booming urban population, Ethiopia prepared a housing program of Integrated Housing Development Program (IHDP) in 2012, intending to integrate stakeholders in housing development programs, who were the government, private real estate developers, and self-help housing cooperatives (Debele and Negussie, 2021; Sunikka-Blank et al., 2021). The government was confined to providing condominium housing development in Addis Ababa only. Regional urban areas are more inclined in investing on self-help cooperative housing while the government helps by providing land at the lease benchmark price (FDRE, 2011).

In Bahir Dar, the capital of the Amhara region, the shortage of affordable housing is particularly acute (Abdie, 2012; Adam, 2014a,b; Admasu et al., 2019; Indris, 2022; Yimam et al., 2022). This situation is worsened by the migration of the Amhara region communities from different parts of the country due to ethnic-based conflicts. Hence, the urbanization rate is alarming, which is supposed to be 7% (BDCSPO, 2022). When the new arrivals are added to the existing backlogs who wait for serviced land for housing in the city, the housing value, even for renting, is so high that the majority of the low- and middle-income groups cannot afford, and they are forced to live in slum areas and informal settlements at the edge of the city within the non-serviced situation.

In contrast to cooperative housing models in countries, such as Angola, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, and Kenya, where government support enhances affordability through policies, such as long-term bank loans with minimal or zero interest, Ethiopia’s cooperative housing operates as a self-help model, with members responsible for all costs, including land acquisition and construction. Surprisingly, there has not been any specific study on the affordability of this unique approach, thereby prompting researchers to investigate. This study aimed to explore the policies governing self-help cooperative housing in urban areas of the Amhara Region, using Bahir Dar as a case study. The research is essential for scholars in Ethiopia, globally providing insights into this kind of cooperative housing model with its associated limitations and sayings of improvements and serving as valuable literature for those interested in cooperative housing in the global south.

Hence, the rationale behind this study was to pinpoint barriers that prevented the creation of affordable housing by analyzing the policy and practice of land acquisition under the cooperative housing scheme in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. In addition, this research is to provide recommendations for improving the legal environment for land acquisition for affordable housing in urban Ethiopia, notably in the study area. The study’s conclusions will be useful to decision-makers, builders, financiers, and other parties engaged in the construction of affordable housing in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. The research also adds to the body of knowledge on Ethiopia’s affordable housing and urban land management systems. Other Ethiopian cities with comparable housing needs might benefit from the knowledge of the difficulties and possibilities for the creation of affordable housing in Bahir Dar. Hence, the study examined the policy and practice of land acquisition for cooperative housing projects, and it attempted to give answers to the following major research questions:

(1) What is the current state of land acquisition policy and practice for the Cooperative Housing scheme in Bahir Dar?

(2) What are the bottlenecks that are hampering the cooperative housing scheme in Bahir Dar?

(3) How can the current cooperative housing policy be improved to prove affordable housing?

2 Ethiopian urban land tenure and access policy regimes

Ethiopia has a long and complex history of land tenure systems, with many changes occurring over different regimes. To understand the evolution of Ethiopia’s urban land tenure system and its security, it is useful to examine its history under three distinct political regimes: the Imperial regime, the Derg regime, and the FDRE regime.

In the history of urbanization in Ethiopia, before the second half of the 19th century, urbanization was almost non-existent, except in the seemingly political centers settled by the military men, nobilities, and families of the clergy who had been settling around the palace (Gebremichael, 2017). However, with the emergence of Addis Ababa as the political center by King Menilik II in 1874, societies other than the above-listed ones started living. However, other communities were not eligible to access urban land (Gebremichael, 2017). The first decree in Ethiopia dealing with the private land ownership land tenure system was the 1907 decree of Menilik II, which declared that countrymen and foreigners could buy urban land from the private land owners of members of nobilities, clergy, and military who had been given the right to own land privately (Gebremichael, 2017). At that time, the right to access urban land was given to such community members only. Therefore, during the imperial regime under Emperor Menilik II, the land tenure type was private time, and land access was restricted to the nobilities, clergy, and those who were serving as military men. Those countrymen either bought or rented the urban land since they had no access rights.

Since there was no state land that individuals claimed for housing in urban areas, during that time, private land owners built homes for rental purposes as the countrymen had nothing to buy land; they got urban houses by renting. In general, the land tenure type during the imperial regime was a kind of private tenure system by which the family members from the class of the nobility, clergy, and military men were given the right of access from the state, while other members of citizens were considered as tenants on the lands of private owners (Adam, 2014d; Wubneh, 2018). The system was consolidated by Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia, who even declared the private ownership of urban land and developed property enshrined under Ethiopia’s 1931 and 1955 constitutions (Gebremichael, 2017). It was the merchants next to the above classes of the ruling family who could afford to buy urban land and build houses for rental purposes (Gebremichael, 2017). This system of land tenure by a few classes of society soured the urban tenant settlers and was able to become one reason for the downfall of the imperial regime substituted by the Derg regime in 1974.

The Derg regime in Ethiopia is boldly known for its declarations to abolish the imperial political systems, including the land tenure system. Immediately after it took power through the military overthrow of the imperial regime, over the imperial regime under Emperor Haile Selassie, the first action was converting the land tenure system from private owners by few community classes to the state ownership of all land, rural and urban, and all extra urban houses (Derg, 1975a,b). In the rural land tenure perspective, the tenants over the land of the lord were declared for the use/holding right of the land, while urban house rent holders were continued as the holders of rental houses by paying 80–85% diminished rental price from the previous price. Moreover, every citizen was eligible to get up to 500 m2 of urban land for residential housing purposes. Therefore, the land tenure system was framed by the ownership rights of the state and holding rights by the citizens, and access was not restricted to a few special societal groups as of the imperial regime. The problem with the contemporary land tenure system was that the citizens had no right to sell, buy, and mortgage their land holdings and housing, and inheritance was restricted to people who had blood relationships.

The Derg regime ended with the FDRE regime in 1991, which continued state ownership of all land tenure systems, rural and urban. However, the land administration system for urban land was changed to a leaseholding system; different lease periods for different land uses ranged from 15 years for urban agriculture and 99 years for residential and some special social service purposes (FDRE, 1993, 2002, 2011). In the country, the first urban land leaseholding proclamation was introduced in 1993 as proclamation number 81/1993 (FDRE, 1993). In the introduction of the proclamation, the proclamation stated that the purpose of leaseholding of urban land is to bring sustainable urban development by collecting revenue through leases and involving private investors in urban property development by easing the cost of the transfer of the land. However, the proclamation asserts that when a leaseholder sells or transfers their developed property, any value appreciation beyond their initial lease payment should be retained by the local government and restricts the private investors from engaging in real estate development, as their intention is to make a profit. Hence, the intended urban development with the integration of private urban property investors remained in paper, and this was the main point for the revision of the proclamation in 2002 by proclamation 272/2002.

However, the new version of the urban land lease proclamation came up with a different type of problem, mainly due to its provision of the leasees to capture all land value added to the land when transferring their right to the third body (FDRE, 2002). Additionally, the proclamation states different modes of urban land transfer, including tender, allotment, assignment, award, and negotiation with municipalities. Most of the modes were founded as corrupt ways by which corrupt urban land managers, speculators, and land brokers emerged as dominant actors in the urban land market. The speculators engaged in informal negotiations with corrupt officials to gain access to urban land. Brokers played a pivotal role in facilitating these informal land acquisitions. Subsequently, those who secured the land lease engaged in speculative activities without developing the land, and they later transferred their rights to third parties, effectively capturing the entire increase in public land value. As a result, planned urban land development by private real property investors remained unrealized, and the government suffered revenue losses due to the absence of value-added land taxation. Looking at its adverse effect, after 5 years, the EFDRE government decided the proclamation to stay on hold until a new proclamation is studied and issued. Accordingly, after 5 years of holding proclamation 272/2002, the third version, which is under function until present, as proclamation 721/2011, has come into effect, intending to correct the defects of the previous versions.

Hence, the current proclamation, 721/2011, reads in its introduction that the purpose of the revision is to bring sustainable urban development, and the increased land value is to be distributed between the public and the leaseholders/developers (FDRE, 2011). The leaseholders are eligible to share in the division of the land value increment only if they adhere to the lease agreement, which stipulates that the land must be developed to a minimum of 50% or more. When the leased land is transferred without development or development less than 50%, then the value added should totally be captured by the municipality. In addition, the modalities of land transfer were declared to be tender and allotment, while others, such as award, assignment, and negotiation, were declared to be exposed to corrupt practices.

The proclamation stated that urban land transfer for all housing modes, other than government-constructed condominium housing and government-approved cooperative housing programs, should be transferred through auction. However, urban land acquisition at benchmark prices is designated for cooperative housing programs and government-constructed condominium housing, which are intended as affordable housing options primarily for low- and middle-income urban communities, even though their affordability in practice may be limited.

Generally, the land tenure system of Ethiopia has been changing with the change of political regime since the second half of the 19th century. The land was privately owned by private holders, and access was restricted to the nobilities, clergy, and military men during the imperial regime, while all urban and rural lands, including extra urban houses, were nationalized and owned by the state during the Derg regime of Ethiopia. With the continual of the Derg regime, rural and urban lands have become owned by the state, but the land administration has become leasehold for urban land and perpetual to the rural land. The common feature of urbanization in the regimes is again different: very insignificant during the imperial regime and little improved during the Derg regime but an extremely high rate of urbanization at the present time, leading to a high demand for urban land associated with such a slow supply of it, which is responsible for the acute housing shortage in urban areas of the country, including the case study area, Bahir Dar city.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 The background description of the study area

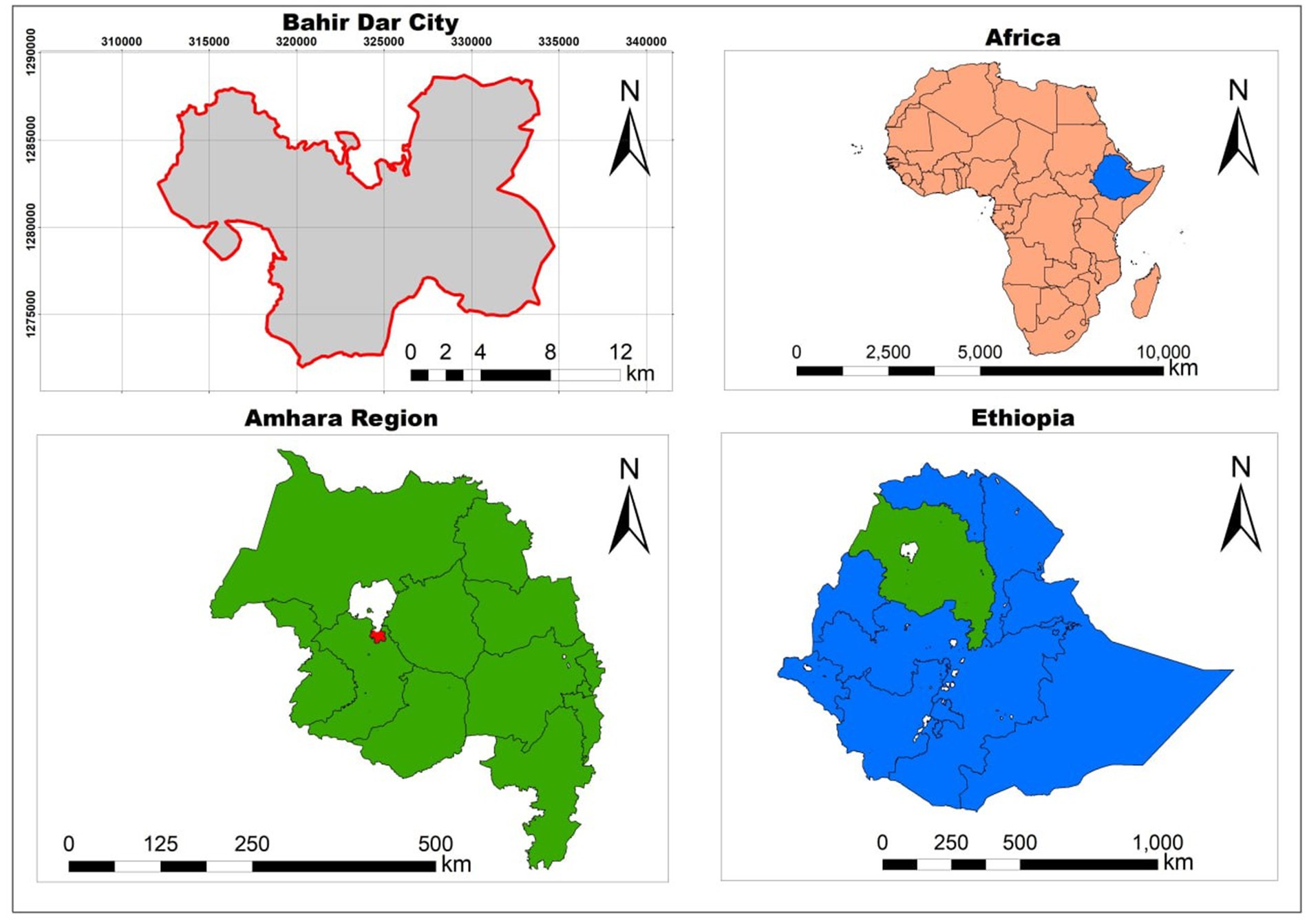

Ethiopia is a country found in the Horn of Africa, sharing a border with Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, Kenya, South Sudan, and Sudan. It is divided into 11 regional states and two chartered cities, one of which is Addis Ababa, the capital city, and the other is Dire Dawa. As shown in Figure 1, the study area, Bahir Dar city, is located in the northwestern part of the country at an average elevation of 1,800 m above sea level and is the capital city of Amhara National Regional State (ANRS), which is the second largest populated region in the country. The city is known for its beautiful landscapes, including the Blue Nile Falls and Lake Tana, which is the source of the Blue Nile River. Bahir Dar city is also home to several historic monasteries and churches, including the famous Ura Kidane Mihret Monastery, Kibran Gabriel Monastery, and Tana Kirkos Monastery. The crossing scenery of the Blue Nile River across the city, sourced from Lake Tana, adds beauty to the natural landscape of the city. Hence, the city is a popular destination for both domestic and international tourists; indeed, tourism is having a significant impact on the economy of the city and the surrounding regions.

The socioeconomic, political, and physiographic advantages of the city pull the population from urban and rural areas of Ethiopia, especially from the Amhara region. The population of the city was 54,766 in 1984 (the first national population and housing census of Ethiopia), and during the second census, which was conducted in 1994, the population grew by 72% and became 94,235 (CSA, 1984, 1994). The third census was conducted in 2007, i.e., after 15 years, and the population was 180,174, double of the population in 1994 and triple of the population in 1984, 20 years after the 1984 census (CSA, 2008). While no recent census data has been gathered since 2007, population projections have been formulated for the period spanning from 2012 to 2037. These projections suggest that the population of Bahir Dar is anticipated to experience rapid growth, with an estimated population of 313,997 in 2017 and projected to reach 455,901 by 2022 (CSA, 2013b; BDCSPO, 2022).

However, the rapidly increasing trend of the city’s population resulted in socioeconomic developments, with some adverse effects. The housing sector was among those highly affected. The report of the 1984 population and housing census reported the availability of 9,206 housing units (HUs) and 10,921 households (HHs), revealing that 89% of the HHs were home owners, and during the second census in 1994, HUs and HHs were 19,808 and 20,857, respectively, in which up to 95% of the HHs had homes (FUPI and Bahir Dar City Administration, 2006). Hence, the proportion revealed that land acquisition for different urban uses before the introduction of the first urban land lease system of Ethiopia in 1993 was via a permit system, which seemed competent enough to access land for housing.

However, after the introduction of the lease system, land access started becoming a merit based on income. It was projected to sustain 95% of home owners (reach 35,556 HUs to the perspective projected 37,344 HHs) in 2015. However, the study by the World Bank and Government of Ethiopia (2015) disclosed that only 40% of the HHs were able to live in their homes, while 60% of the city’s population were dependent on rental housing, which adversely contributed to the proliferation of informal settlings at the edges of the city (Adam, 2014a; Liu et al., 2023).

Generally, Bahir Dar city is known for its beauty of the natural landscape and cultural heritages, which made the city one of the best tourist destinations in the country, experiencing a high rate of urbanization, in terms of both population booming and areal expansion. However, the city is suffering much from residential problems, including the expansion of informal settlements at all expansion dimensions. This is mainly due to the rising demand for urban land value for housing, which is not affordable for the mass urban population.

3.2 Research methods

This study aimed to analyze the land acquisition policy and practice for cooperative housing schemes such as affordable housing solutions in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Indeed, the city launched a cooperative housing scheme to respond to the affordable housing demand specifically for its low- and middle-income residents in 2013 (proclamation 9/2013), which is still functioning.

To attain the research objective, a descriptive research design incorporating a case study strategy and a cross-sectional data collection frame was employed. The case study approach, a qualitative research method, facilitated the investigation of a specific case or phenomenon within its genuine environment, utilizing various sources of evidence, including interviews, documents, and observations (Zainal, 2007; Baxter and Jack, 2008). This type of methodology is well-suited for investigating intricate and diverse occurrences, such as the peri-urban land acquisition, which encompasses numerous stakeholders and carries diverse social, economic, and environmental consequences. Through the case study approach, researchers can collect comprehensive and detailed information regarding the experiences and perspectives of the impacted communities. Furthermore, it enables the identification of the underlying factors and dynamics involved in the land acquisition process, particularly concerning housing under cooperative housing schemes (Creswell, 2014).

As per the data provided by the city’s housing cooperative organizer office, approximately 31,596 land plots were designated for members of the self-help housing cooperative between 2014 and the end of 2021. However, the majority of the plots remain undeveloped, and there is a waiting list of households. These findings, obtained through the case study, are anticipated to have broader applicability, limited not only to the current areas under investigation but also to other urban regions within ANRS and other urban areas that employ a cooperative housing scheme.

To examine the matter at hand, a combination of primary and secondary data sources was employed. Primary sources consisted of key informant interviews (KIIs), focus group discussions (FGDs), and field observations (FOs). These methods allowed for the collection of first-hand information. Additionally, secondary sources included annual reports, housing, and urban land administration-related rules and regulations such as cooperative regulation 9/2013 [66], proclamations including the three versions of the land lease policies, related research articles, and municipality documents such as plans and reports from the municipality offices of urban land management, urban housing and infrastructure development, and cooperative housing expansion office.

When choosing participants for both KII and FGD sessions, careful consideration was given to include individuals who possessed a comprehensive understanding of cooperative housing practices and their strengths, limitations, and a good knowledge of its policy. Hence, in conducting the key informant interviews (KIIs), a purposive sampling method was employed to select individuals with expertise in urban planning, senior officers involved in urban land development and management, and experts from cooperative expansion offices and housing cooperative committees. These key informants were chosen specifically for their comprehensive understanding of the current high demand for urban land driven by urbanization, housing conditions, and the policies and practices surrounding urban land acquisition by housing cooperatives. During the FGD sessions, a stratified random sampling approach was employed to ensure the inclusion of housing cooperative members who obtained land at various time points, those who have already constructed their homes, those who have not yet built their homes, and those who remain on the waiting list without receiving land. Participants were selected with the assistance of friends residing in the city and officers from the city’s cooperative expansion office. Before participation, the purpose and nature of the study were clearly communicated to the participants, and their involvement was entirely voluntary. Additionally, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

For the KIIs, a semi-structured interview guide was used to explore the process of housing cooperative formation, land acquisition processes and practices, urban land demand and supply for housing in general and housing cooperatives scheme in particular, the limitations of the cooperative housing policy, and the challenges that hamper the effectiveness of the cooperative housing program. The KIIs involved a total of 30 participants, including 5 urban planners, 6 senior officers and experts from municipality offices of urban land development and management, cooperative expansion, and urban housing and infrastructure development, and 19 committee members of the housing cooperatives who got land in 2014 (4 KKIs), 2019 (1 KKI), 2020 (6 KIIs), and 2022 (5 KKIs) and who were certified but have not got land yet (in the waiting list) (5 KKIs). In adaption to the KKIs, for the FGDs, a focus group guide was used to obtain the participant’s feelings about the overall land acquisition under the cooperative housing scheme in Bahir Dar. Three FGD sessions were conducted involving a total of 21 housing cooperative members (two FGDs who got land and one FGD who was on the waiting list).

The researcher took note of the contexts of the KIIs and FGDs in a notebook. The interviews and discussions were conducted by the researcher with the help of friends living in the city using the local language, Amharic. Later, the transcripts were translated into English. The participants chose their preferred venues, either their offices or homes/locality. The KIIs and FGDs lasted 60–90 min and were recorded in the notebook. In addition, the researcher conducted an extended direct field visit to observe three sites (Lideta in the south and Diaspora and Zenzelma in the east edge of the city) where residential land plots were provided to housing cooperatives in Bahir Dar city. The data collection took approximately 7 weeks, from mid-January to the first week of March 2022, at different times.

To analyze the urban land acquisition for the cooperative housing scheme of Bahir Dar city, a thematic analysis approach was employed. The process involved transcribing and reviewing the KII and FGD data to gain a basic understanding of the content, followed by breaking down the data into meaningful segments. This method aimed to explore the essence of the data and reveal the fundamental concepts or ideas underlying the content (Creswell, 2014). The data collected through diverse techniques were subjected to thematic analysis, a widely used approach to gain comprehension of the perspectives, sentiments, and encounters of the participants. Next, the data were categorized and grouped based on similarities and differences to form themes. Finally, the themes were scrutinized, refined, and consolidated until a clear and comprehensive understanding was achieved. This allowed for the depiction of the affordable housing provision in the cooperative housing scheme.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 The cooperative housing scenario: land acquisition policy and practice in Bahir Dar

4.1.1 The policy perspective

The land tenure and administration system in Ethiopia follows a state ownership model for both urban and rural lands, while citizens are granted holding or use rights (FDRE, 1995). In such a land tenure system, the government has the right to expropriate private landholdings by paying commensurate compensation only for their developments, but not for the land value (FDRE, 1995, 2019). In the case of urban land, it is administered through a lease system, allowing different land uses for varying periods of time (FDRE, 1993, 2002, 2011). The lease terms range from 15 years for urban agriculture purposes to 99 years for residential housing purposes. The lease proclamations declare that the municipalities hold the ownership of all urban land within their administrative boundaries. These boundaries consist of two significant categories: the administrative boundary, where the authority to administer the land lies, and the planning boundary, which extends beyond the administrative boundary and encompasses the peri-urban areas. The planning boundary serves as a future growth threshold for the urban area. The peri-urban area, located between the administrative and planning boundaries, falls under rural land administration and is primarily used for agricultural purposes. In contrast to urban land, the ownership of rural land is not subject to lease terms or time limits, as seen in urban areas. Instead, farmers maintain perpetual control and usage rights over their agricultural land.

Concerning Ethiopia’s land tenure system, scholars have expressed their dissatisfaction with the two distinct land tenure types and the compensation provided in cases of government expropriation, indicating why the land holders have a negative attitude toward it. For instance, Mohammed (2018) has contended that expropriating peri-urban land from lifelong landholders and compensating them based on a 15-year land crop value when reclassifying it as high-value urban land is unjust. Consequently, such urbanization is seen as unsustainable, as it occurs at the expense of peri-urban farm landholders. From another perspective, scholars such as Adam (2014c) and Wubneh (2018) have contended that the urban land lease policy displays a lack of consideration for the land use rights of low- and middle-income residents’ residential rights. This is because it predominantly emphasizes the auction mode for land acquisition, effectively making it accessible primarily to high-income groups. In summary, it can be observed that Ethiopia’s land tenure policy falls short of upholding the rights of rural landholders as stipulated in the constitution. Additionally, it does not sufficiently address the needs of the broader urban community, particularly those belonging to low- and middle-income households.

In the latest version of the lease proclamation, there have been significant updates regarding the transfer of land from municipalities to users in Ethiopia. It is clearly stated that land transfers can occur through two modalities: allotment and tender (FDRE, 2011). Allotment refers to the transfer of land at the lease benchmark price, while tender involves land transfer through auction to the highest bidder from the lease benchmark price. Additionally, the lease proclamation declares that government-approved self-help cooperative housing programs are eligible for land transfer through the allotment modality. The Amhara National Regional State, recognizing the legal provisions of the lease proclamation, has issued regulation 9/2013 (ANRS, 2013).

The main objective of regulation 9/2013 is to promote affordable housing for low- and middle-income urban residents in the region through the cooperative housing scheme. The regional government aims to achieve this by facilitating the provision of serviced land to housing cooperatives. The regulation serves as a practical implementation guide for the transfer of land to cooperative housing programs. It outlines the specific procedures, criteria, and requirements that the housing cooperatives fulfill for acquiring land through the allotment modality. It also set the land plot size and housing standards constructed by the housing cooperatives based on the population size of urban areas.

As per the regulation, there are specific criteria that prospective members must satisfy to establish a housing cooperative under this regulation. First, they must have been formally recognized residents of the town or city for a minimum of 2 years. Second, they should not have previously owned a house or land for housing purposes, either individually or jointly with their spouse. Additionally, they need to demonstrate their financial capability to cover the costs of land compensation if expropriation occurs and their ability to construct the house. It is also specified that a self-help housing cooperative should consist of an even number of members, ranging from 10 to 24 individuals, and the minimum is 14 for metropolitan cities such as Bahir Dar. Additionally, this legal instrument defines the stakeholders in the process of urban land acquisition: the housing cooperative and the members, the municipality cooperative office as organizer and certifier, the municipality urban land administration office to prepare serviced land for housing, the infrastructure development office to provide basic services across on the land to the cooperatives. Moreover, the regulation sets the criteria for eligibility as well as the rights and responsibilities of housing cooperatives and their members.

The organizer’s office meticulously assesses each member’s eligibility in accordance with the criteria outlined in the regulation. Subsequently, they issue a certification to enable the bank or savings and credit association to establish closed savings accounts for the members. Once each member has saved 20% of the specified construction cost, the cooperative organizer office grants certification to the housing cooperative, allowing them to proceed with land acquisition. A formal letter is then sent to the municipality’s land administration and management office, requesting the preparation of serviced land. The regulation explicitly designates the municipality as the responsible entity for providing serviced land. Priority is granted to cooperative members who have received certification and registered first when allocating serviced land. Furthermore, it is essential to note that serviced land allocation should occur within a year after the commencement of the savings process. Nevertheless, in practice, the municipality office has faced criticism for failing to adhere to the specified timeframe for land allocation. During KIIs, experts from the cooperative organizer office and members of the cooperative committee revealed that the municipality took more than 4 years to prepare the serviced land. They noted that housing cooperatives certified in 2018 had to wait until the end of 2022 before obtaining the allocated land.

Additionally, the regulation addresses the issue of land plot sizes and housing standards. It provides specific guidelines for land size allocation based on population thresholds. The regulation acknowledges the urban containment principle, which stipulates that as the urban population increases, the size of land plots decreases. For urban areas with a population of more than a hundred thousand such as the study area Bahir Dar city, the land size allocated to each member is regulated to be between 100 and 150 square meters (m2). For populations between 50,000 and 100,000, the land size is set between 150 m2 and 200 m2. Similarly, for populations between 10,000 and 50,000, the land size is set at 250 m2, and for populations between 2,000 and 10,000, the land size ranges from 300 m2 to 350 m2. The regulation also set the housing standard to be a house constructed of local materials using mud and wood for small urban areas to G + 1 villa house (a building consisting of a ground floor and one additional floor) for urban areas with a population exceeding 100,000. As the study area, Bahir Dar city, falls in a G + 1 category, it means that cooperative housing members in the city are required to construct their homes following this standard, regardless of their individual capabilities or preferences.

The cooperative committee KII participants and FGD discussants raised concerns about the small size of the land plots, which they argued resulted in a lack of space for green area exposure within the house compounds. In response, participants from the municipality office KII suggested that the building standard should allow for structures with G + 1 to make up for the limited horizontal space on the land plot. However, committee members and FGD participants disagreed with this approach, highlighting that the building standard did not take into account the economic status of the cooperative members and its unaffordability at all. Indeed, the land plot size is small compared to the average residential land plot size of sub-Saharan countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, the mean average plot size designated for residential use stands at 591 m2, which is four to five times larger than the Bahir Dar city’s land plot standard for housing cooperatives (UN-Habitat, 2019). Consequently, it can be deduced that the policy lacks rationality in allocating small land plot sizes of 100 m2 and 150 m2, coupled with the requirement for G + 1 building standards. This approach is deemed entirely unaffordable and impractical as an affordable housing scheme for low- and middle-income urban residents.

Generally, the formal way of urban land acquisition for affordable housing development in the study area and other urban areas of ANRS lies on the cooperative housing scheme. This housing program is legally backgrounded to the lease proclamation, and regulation 9/2013 sets the details of procedures, stakeholders, criteria, land plot size, and housing standards. Nonetheless, the policy faces criticism due to its stringent criteria, particularly toward urban settlers who have resided in urban areas for less than 2 years and, hence, are not eligible to participate in the housing cooperative scheme. This paved the way for corrupt officials who tended to provide false certifications to ineligible individuals. Furthermore, the land plot sizes specified in the regulation are considered too small, and the building standards are perceived as excessively costly and beyond the financial capacity of the cooperative members. These factors often compel members to sell their properties in an incomplete state. Therefore, the regulation falls short of achieving its intended objectives, which are to provide affordable housing for middle- and low-income residents of the city. Unfortunately, only a fraction, specifically less than one-third, of the eligible individuals in the designated social categories are able to secure land under these provisions.

4.1.2 Land delivery practice scenario

In Bahir Dar city, the provision of land for housing purposes initially involved the permit modality for private house developers. However, due to malpractices and gaps in the lease-holding version of Proclamation 272/2002 (Gebremichael, 2017), all modes of land transfer were halted in the city from 2006 to 2013. This pause in land transfer was necessary to address the issues and ensure a more transparent and effective process moving forward. However, the situation resulted in a backlog on the existing land demand for housing, while the population growth continued increasing at a 5.4% growth rate (CSA, 2013b; World Bank and Government of Ethiopia, 2015). Proclamation 272/2002 was revised by 721/2011 in 2011, and after 2 years, the ANRS launched a regulation to deliver urban land in allotment for a cooperative housing program in 2013 (ANRS, 2013).

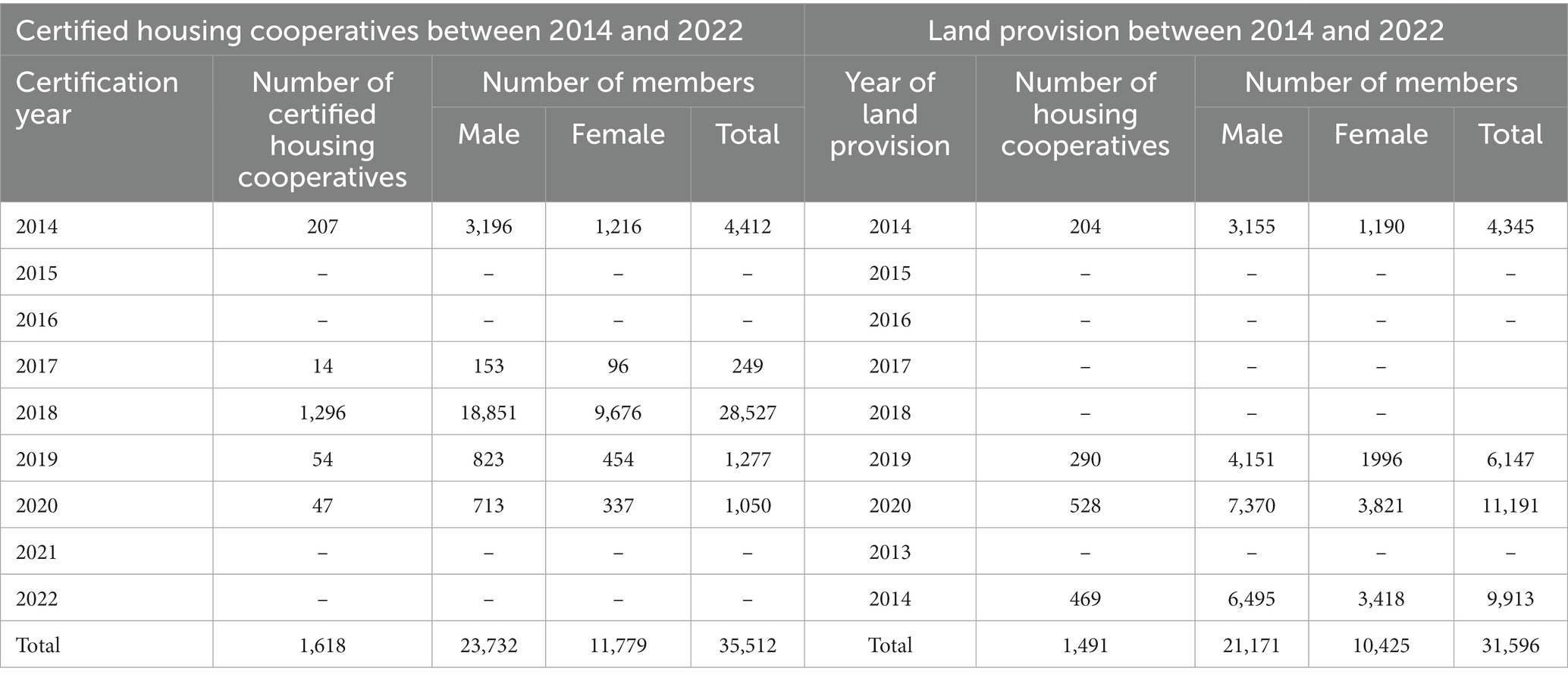

Since the implementation of the regulation, residents in Bahir Dar city and its satellite towns (Meshenti, Zegie, and ChisAbay) have actively formed housing cooperatives and obtained certification to acquire residential land. As shown in Table 1, between 2014 and 2022, the municipality has certified a total of 1,618 housing cooperatives comprising 35,512 members. During the same period, a remarkable number of 31,596 plots of residential land were transferred by the municipality in Bahir Dar city and its satellite towns.

Table 1. Information on housing cooperatives certification and land provision in Bahir Dar City from 2014 to 2022.

Table 1 reveals significant information about the certified housing cooperatives and the allocation of residential land in Bahir Dar City from 2014 to 2022. Among the certified cooperatives, 297 cooperatives comprising 6,320 members were located in the satellite towns, while the remaining 1,321 cooperatives with 25,276 members were certified and allocated residential land within the city. This exemplifies the widespread participation and engagement of residents in the cooperative housing scheme, as numerous individuals have benefitted from the initiative and acquired their own residential plots.

During KIIs with officials and experts from the Bahir Dar municipality’s urban land management office and cooperative office, it was disclosed that the organization and certification of housing cooperatives experienced a 4-year hiatus beginning in 2014. This interruption was primarily attributed to the discovery of corruption in both the cooperative formation and land allocation processes. In response to this matter, the Amhara National Regional State issued a circular letter to municipalities, including Bahir Dar, alerting them to the corruption issues and emphasizing the necessity of implementing corrective measures. The reason for the pause in the land delivery process was to scrutinize and rectify the faulty procedures and activities that had been identified.

The table also indicates that, in 2014, a total of 207 cooperatives with 4,412 members were certified. Out of these 4,412 members, 204 cooperatives (comprising 3,155 male members and 1,190 female members) received land plots for housing within the same year. The remaining three cooperatives, consisting of 67 members, were placed on a waiting list for the following year. In subsequent years, namely 2015, 2016, and 2017, no cooperatives were formed or certified, except for 11 cooperatives in a special case in 2017, which increased the waiting list to 14 housing cooperatives. However, in 2018, there was a significant surge in the formation and certification of self-help housing cooperatives, with a total of 1,296 cooperatives being certified.

Although land acquisition experienced a temporary halt from 2014 to 2019, 54 housing cooperatives were certified under special circumstances. In that period, 290 cooperatives (consisting of 4,151 male members and 1,996 female members) received land plots for housing. The size of the land allotted to each member was reduced from 150 m2 in 2014–100 m2. Moving forward, in 2020, 47 housing cooperatives (comprising 713 male members and 337 female members) were certified, and 528 self-help housing cooperatives (with 7,370 male members and 3,821 female members) received 100 square meter plots of land. However, no cooperatives were formed, and no land was provided in 2021.

According to key informants, in light of the 2014 allocation of 150 m2 land plots, the Amhara National Regional government issued a circular letter to all municipalities in the region, including Bahir Dar city. The objective was to reduce the size of land allocated to cooperatives from 150 m2 to 100 m2. This decision stemmed from the substantial increase in demand for cooperatives, surpassing the government’s capacity to provide serviced land. The adjustment was deemed necessary to manage the overwhelming demand and ensure efficient utilization of available land resources. In 2022, no new cooperatives were formed, but 469 backlogged certified cooperatives (with a total of 6,495 male members and 3,418 female members) were provided land plots, with the land size restored to 150 m2.

Overall, the organization and certification of self-help housing cooperatives in Bahir Dar City primarily occurred in 2014 and 2018, with some certifications taking place in 2017, 2019, and 2020. Land plot provision took place in 2014, 2019, 2020, and 2022, with the land size varying between 100 and 150 m2. It is noteworthy that almost all of the certified cooperatives were able to acquire land plots ranging from 100 to 150 m2. The first 204 cooperatives, consisting of 5,345 members, as well as the cooperatives certified in 2014 (469 cooperatives with 9,913 members), received 150m2 plots of land, while the remaining 17,338 members of housing cooperatives in Bahir Dar were allotted 100 square meter plots for housing. According to UN-Habitat (2019), the land plot size allocated for housing cooperatives in Bahir Dar city is nearly one-fifth of the average residential urban land plot size of sub-Saharan Africa, which is 591 m2. This size does not provide sustainable access to green exposure and open space within residential home compounds.

In conclusion, the cooperative housing scheme’s land delivery system in Bahir Dar has successfully provided land to over 31,000 cooperative members. However, it is worth noting that the potential demand far exceeds this number, with over 80,000 low- and middle-income households in the city, as reported by the city’s cooperative office. Additionally, the small land plot size is another challenge that limits beneficiaries’ access to additional service areas, such as greenery and open space. Moreover, the cost-intensive nature of the land price and the overall process has been reported as unaffordable for the majority of the intended beneficiaries, the cooperative members.

4.2 The bottlenecks hampering the cooperative housing scheme in Bahir Dar

The cooperative housing scheme implemented in Bahir Dar city in 2014 with the aim of providing affordable housing for low- and middle-income residents faced several bottlenecks that hindered its effectiveness. One major bottleneck was the overwhelming demand for housing, surpassing the capacity of urban managers to provide serviced land. This demand was further intensified by the backlog of housing demand from 2006 to 2013, when land plot delivery was halted entirely due to the inefficiency of lease proclamation 272/2002. It was not until the subsequent version, proclamation 721/2011, and the forthcoming cooperative housing regulation that significant changes were introduced, all while urbanization rates driven by migration remained high. KIIs revealed that when the scheme was launched, there was a congestion of individuals in acute need of housing, leading to difficulties in screening member eligibility. Some members in 2014 managed to cheat the system and obtain land plots at the expense of eligible individuals. In support of this, scholars such as Adam (2014a), Sen and Mallik (2017), and Liu et al. (2023) contend that residents tend to resort to informal methods as alternatives when housing demand remains high in urban areas and formal avenues for addressing it are limited. This includes informal land acquisition, often undertaken through unauthorized and fraudulent means.

Another obstacle was the lack of an annual plan from the land management office regarding the number of land plots allocated to housing cooperatives each year. The office responsible for organizing the cooperatives would certify a certain number of cooperatives but faced the challenge of insufficient serviced land provided by the land management office, even from the program’s inception in 2014. The peri-urban areas of Bahir Dar, which had potential land for development, were occupied by informal settlers, making it difficult to clear the land and provide basic infrastructure. The problem of informal settlements was further exacerbated during the period when housing land delivery was paused. The World Bank study on urban land and housing markets (World Bank and Government of Ethiopia, 2019) has revealed that Ethiopian towns and cities do not allocate an annual residential land plot and housing each year, which should ideally match the pace of urbanization and the demand for land for housing. In the case of Bahir Dar city, this issue has been identified as the primary reason for the delay in land acquisition by cooperatives, stretching up to 5 years after certification, despite the regulation stipulating that certified housing cooperatives should receive serviced land within 1 year of certification. Respondents in KIIs from the urban land management office mentioned that their strategy does not involve providing serviced land directly from the annual land budget stock. Instead, their approach is to acquire land from third-party holders through expropriation, initiated upon the request of serviced residential land plot provision of the cooperative organizer office for certified housing cooperatives. This land provision strategy mirrors the process applied to public and real estate investors, who also undergo a search, preparation, and provision process after their land requests.

Eligibility criteria set in the cooperative regulation also posed limitations that affected the effectiveness of the scheme. The minimum financial capacity required to become a housing cooperative member was not affordable for the majority of urban residents, contradicting the program’s goal of affordability for the low- and middle-income groups. The cooperative regulation dictates that the certification of housing cooperatives’ eligibility to acquire serviced land plots is contingent upon their ability to save 50% of the construction cost from their personal savings. Scholars argued that residential development is a function of serviced land supply, housing finance, and construction materials (Hu and Qian, 2017; Khan et al., 2022). FGDs with housing cooperative members revealed that they faced significant challenges in saving the required 50% construction cost and covering land compensation expenses without access to government-established housing finance modalities. They are dependent on small inconsiderable loans with frustrating interests from Amhara Credit and Saving Association, their own savings, and informal loans from friends and families. Hence, in the study area, due to the absence of formal housing finance options such as bank loans for housing cooperatives, coupled with the majority of low-income level cooperative members, the scheme’s objective of providing affordable housing remains largely theoretical and distant from reality. Moreover, corruption related to eligibility has further extended the land acquisition process following cooperative certification. Some members have resorted to obtaining false ID cards or presenting fraudulent divorce certificates to secure multiple plots of land. As a result, the municipality has been actively involved in screening certified housing cooperatives before proceeding with land provision.

Additionally, high and unrealistic building standards, specifically the requirement for G + 1 typology, posed a significant hurdle to the effectiveness of the cooperative housing program. While the program aimed to be an affordable option, the beneficiaries, who were primarily low- and middle-income groups, were responsible for covering the construction costs and land compensation payments, which proved to be unrealistic. Participants in focus group discussions revealed that a large portion of cooperative members had not begun building their homes due to financial constraints, as they lacked options until reaching the advanced stages of construction, which would make them eligible for bank loans. Many members, particularly civil servants with limited salaries, struggled to afford construction costs, even with the help of loans from relatives and friends to cover land compensation. Interviews with key informants and focus group discussions disclosed that, out of the approximately 31,000 households that received residential land plots through the cooperative scheme, less than 7,000 were able to partially or fully construct their homes. In this context, the World Bank study (World Bank and Government of Ethiopia, 2015, 2019) has revealed that the housing problem in Ethiopian cities is exacerbated by unrealistic and costly building standards that do not align with the income levels of the majority of urban residents. Hence, in Bahir Dar city, the cooperative members, after getting residential land, either tend to sell or wait for many years until they get the capacity to construct.

4.3 How can the current cooperative housing policy be improved to prove affordable housing?

Improving the current cooperative housing legal background is crucial to providing affordable housing for low- and middle-income residents. The cooperative housing scheme has been implemented to address the pressing issue of affordable housing for low- and middle-income residents of urban areas of Amhara region, including the study area, Bahir Dar city. However, there are several areas where the current policy can be improved to enhance its effectiveness. Some key elements that can contribute to the improvement of the cooperative housing scheme to bring affordable housing development shall focus on housing finance and mortgaging, digitalization of data, ensuring transparency and accountability, avoiding unrealistic building standards, promoting high-rise buildings for cooperatives, and facilitating bulk purchase of building materials.

One of the primary challenges faced by individuals participating in cooperative housing in Bahir Dar city is the financial burden associated with construction costs and land compensation, which totally solder on the cooperative members. To make housing more affordable, the government should establish accessible and affordable housing finance modalities specifically tailored to the needs of cooperative members. The insignificant financial option in Bahir Dar city is the Amhara saving and credit association, which is known to provide small loans with high interest rates that frustrate the members. The FGD discussants and cooperative housing committee key interview respondents underline their argument that the government should arrange housing finance to attain the intended affordable housing by including low-interest loans, subsidized mortgages, and flexible repayment options.

It is possible to take lessons from other African countries, including Angola, Kenya, and Nigeria, which have banks to give a long time with low-interest loans for housing purposes. For instance, according to a study by Cain (2017), Angolan civil servants and military men can get interest-free loans to cover long-term payments from the salary of the employer. On the other hand, according to the studies by Stiftung (2012) and Feather and Meme (2019), the Kenyan government takes a different approach to supporting affordable housing by offering loans to saving cooperatives in proportion to their savings. When these cooperatives have saved up to 30% of the required amount, the development and housing mortgage banks step in to cover the remaining 70% through long-term loans with minimal interest rates. The Nigerian case, by Obodoechi (n.d.), Ayedun et al. (2017), and Adegun and Olusoga (2019), was also found noteworthy, as it allows cooperatives, particularly those comprising government employees, to access direct long-term loans with minimal interest rates. This approach aligns with the objective of facilitating affordable housing solutions for cooperative members. Indeed, during the socialist regime under the Derg government, Ethiopia enthusiastically promoted cooperative housing, resulting in an upsurge in housing supply by cooperatives (Abdie, 2012). This was made possible through controlled construction material prices, free land allocation, and low mortgage interest rates (4.5%) provided by the housing mortgage bank (which is absent nowadays). Consequently, housing cooperatives were able to produce a total of 40,539 housing units between 1975 and 1992. Hence, collaborations with financial institutions and the creation of housing funds can further facilitate affordable housing financing. Furthermore, to reduce construction costs, the cooperative housing policy should facilitate bulk purchases of building materials. By negotiating with suppliers and leveraging the collective purchasing power of housing cooperatives, members can benefit from cost savings. This approach ensures that affordable housing remains a priority, as the overall construction expenses are reduced, making it more accessible for low- and middle-income residents.

In Bahir Dar, residents possess non-digital identification cards (IDs) issued by local governing bodies. When individuals visit the organizing office, they are required to present an ID that confirms their residency in the city for a minimum of 2 years. However, some members, who may not be actual residents of Bahir Dar, unlawfully obtain IDs through corrupt officials responsible for issuing them. These fraudulent practices not only prevent genuine residents from acquiring land but also lead to delays in land delivery due to the need for extensive member screening. To address these challenges and prevent dual registries and other forms of cheating, it is crucial to prioritize the digitalization of data, including residents’ identification cards. Respondents in focus group discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews (KIIs) emphasized the importance of implementing a centralized database that connects various urban areas. This digital infrastructure would facilitate the tracking of individuals attempting to obtain multiple plots of land or manipulate their eligibility.

To enhance the effectiveness of the cooperative housing scheme in Amhara National Regional State’s urban areas, particularly in Bahir Dar, ensuring transparency and accountability is paramount. This involves oversight and accountability measures involving the cooperative office, local administrators responsible for issuing ID cards, the land management office, and cooperative members. To achieve this, regular audits should be conducted to maintain integrity and uphold transparency within the system.

Furthermore, it is crucial to avoid unrealistic building standards and promote the construction of high-rise buildings as another significant element in improving the current cooperative housing policy for affordable housing. The requirement for single residential homes to meet impractical building standards should be reconsidered. These standards often lead to inflated construction costs, making housing less affordable for cooperative members who are mainly in low- and middle-income community sections, as stipulated by the objective of the regulation 9/2013. By allowing for more flexibility in building designs and the tendency to use local construction materials, it is possible to update the cooperative housing scheme and promote affordable housing.

In addition, to address the limited land resources in the city, the affordable housing program within the cooperative housing scheme should actively encourage the construction of high-rise buildings for cooperative housing. According to Adam (2019), high-rise buildings optimize land utilization efficiency by accommodating a larger number of residents within a smaller footprint. This helps the cooperative members allocate their land compensation funds to contribute to the construction cost of shared buildings. This is because the land cost for shared buildings is distributed among all the cooperatives. Meanwhile, in private townhouse designs such as the existing cooperative houses of Bahir Dar, cooperative housing members bear the expensive land costs individually for their private units. This approach allows cooperative members to share the construction costs rather than constructing individual G + 1 villas. The approach further enhances urban land use efficiency by allowing a single plot to accommodate multiple households, contributing to more efficient land utilization of the city’s scarce land and increasing the land supply for cooperative housing. The government can provide incentives and support for the development of high-rise housing projects, including tax breaks and access to infrastructure and amenities.

5 Conclusion

The land tenure system in Ethiopia follows a state ownership model for urban and rural lands. The government has the right to expropriate private landholdings for development purposes by providing compensation for improvements but not for the land value. Urban land is administered through a lease system with varying terms, while rural land is under perpetual control and usage rights of farmers. The latest lease proclamation allows land transfers through allotment and tender, and regulation in the Amhara region promotes affordable housing through cooperative housing programs. Prospective members of housing cooperatives must meet certain criteria, and the size and standards of housing are regulated. In Bahir Dar city, land provision for housing cooperatives experienced a pause from 2006 to 2013 due to issues with the lease-holding version of the proclamation.

Since then, numerous cooperatives have been certified and have received land plots with varying sizes and periods of activity. In Bahir Dar City, land provision for housing initially relied on the permit modality for private developers. However, due to malpractices and gaps in the lease-holding version of Proclamation 272/2002, all modes of land transfer were halted from 2006 to 2013. Following the revision of the proclamation and the issuance of a regulation in 2013, the cooperative housing scheme was implemented in Bahir Dar City and its satellite towns. Between 2014 and 2022, a total of 1,618 housing cooperatives comprising 35,512 members were certified, and 31,596 plots of residential land were transferred by the municipality.

Despite the progress made, the cooperative housing scheme in Bahir Dar faced several bottlenecks. The overwhelming demand for housing, lack of an annual plan for land allocation, presence of informal settlements in peri-urban areas, and corruption in the certification and land provision processes were major challenges. The eligibility criteria and high building standards, such as the requirement for G + 1 typology, also posed limitations, making the scheme less affordable for low- and middle-income groups. As a result, many cooperative members faced difficulties in saving construction costs and covering land compensation expenses, leading to delays in construction and limited progress in housing development. Addressing these bottlenecks will be crucial to ensure the success and sustainability of the cooperative housing program in the city. Many cooperative members struggle with financing construction costs, resulting in a low rate of completed homes.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

DA: conceptualization, data collection, and writing original draft. BA: supervision. DA and BA: review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research manuscript is part of PhD dissertation by the correspondent author under the co-author’s supervision, which is being carried out at Addis Ababa University. The financial support to collect data for this research was provided by Addis Ababa University.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to especially acknowledge the Ethiopian Civil Service University for providing sponsorship and Addis Ababa University for granting PhD education to the corresponding author. Additionally, they would like to express their gratitude to all respondents: urban planners, senior officers and experts of the urban land development and management office, Cooperative Expansion office, and Urban Housing and Infrastructure Development office of Bahir Dar municipality. In addition, the authors would like to extend their gratitude for housing cooperative housing committees and members who participated in KKI and FGD sessions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdie, D. (2012). Self-help cooperative housing potentials and limitations as a housing delivery option: the case of Tana kebele in Bahir Dar. Bahir Dar. Available at: http://etd.aau.edu.et/bitstream/handle/123456789/2929

Adam, A. G. (2014a). Informal settlements in the peri-urban areas of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: an institutional analysis. Habitat Int. 43, 90–97. doi: 10.1016/J.HABITATINT.2014.01.014

Adam, A. G. (2014b). Land tenure in the changing Peri-urban areas of Ethiopia: the case of Bahir Dar City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 38, 1970–1984. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12123

Adam, A. G. (2014c). Peri-urban land rights in the era of urbanisation in Ethiopia: a property rights approach. African Rev. Econ. Financ. 6, 120–138.

Adam, A. G. (2014d). Peri-urban land tenure in Ethiopia; Doctoral dissertation. Available at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:773927/FULLTEXT02.pdf

Adam, A. G. (2019). Thinking outside the box and introducing land readjustment against the conventional urban land acquisition and delivery method in Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 81, 624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.028

Adegun, O. B., and Olusoga, O. O. (2019). Self-help housing: cooperative societies’ contributions and professionals’ views in Akure, Nigeria. Built Environ. 45, 332–345. doi: 10.2148/benv.45.3.332

Admasu, W. F., Van Passel, S., Minale, A. S., Tsegaye, E. A., Azadi, H., and Nyssen, J. (2019). Take out the farmer: an economic assessment of land expropriation for urban expansion in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Land Use Pol. 87:104038. doi: 10.1016/J.LANDUSEPOL.2019.104038

Agyemang, F. S. K., and Morrison, N. (2018). Recognising the barriers to securing affordable housing through the land use planning system in Sub-Saharan Africa: a perspective from Ghana. Urban Stud. 55, 2640–2659. doi: 10.1177/0042098017724092

Anna Kajumulo, T. (2013). Building prosperity: the centrality of housing in economic development. London Routledge

ANRS (2013). Regulation no. 9/2013: determine the supply, delivery and construction of existing and new housing co-operatives for housing construction.

Arjjumend, H., and Seid, M. N. (2018). Challenges of access to land for urban housing in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Glob. Resour 4, 1–11.

Ayedun, C. A., Oloyede, S. A., Ikpefan, O. A., Akinjare, A. O., and Oloke, C. O. (2017). Cooperative societies, housing provision and poverty alleviation in Nigeria. Covenant J. Res. Built Environ. 5, 69–81.

Baxter, P., and Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 13, 544–559. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573

BDCSPO (2022). Bahir Dar Regio-Politan City structure plan: an executive summary of the population study report. BDCSPO Bahir Dar.

Berto, R., Cechet, G., Stival, C. A., and Rosato, P. (2020). Affordable housing vs. urban land rent in widespread settlement areas. Sustainability 12:3129. doi: 10.3390/SU12083129

Brown-Luthango, M. (2010). Access to land for the urban poor-policy proposals for south African cities. Urban Forum 21, 123–138. doi: 10.1007/s12132-010-9081-x

Cabré, E., and Andrés, A. (2018). La Borda: a case study on the implementation of cooperative housing in Catalonia. Int. J. Hous. Policy 18, 412–432. doi: 10.1080/19491247.2017.1331591

Cain, A. (2017). The cooperative housing sector in Angola. Available at: http://dw.angonet.org/sites/default/files/online_lib_files/cain_2017_cooperative_housing_sector_angola_-_cahf.pdf%0Apapers3://publication/uuid/12150ED0-29D0-46F0-8491-30725F990AD2

Çelik, A., Yaman, H., Turan, S., Kara, A., Kara, F., Zhu, B., et al. (2018). Urban land reform in South Africa: pointers for urban policy and planning. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 263, 127252–127258.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approach. 4th Edn. Lincoln, United States: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data.

CSA (1984). Transitional government of Ethiopia the 1984 population and housing census. CSA: Addis Ababa

CSA (2008). Summary and statistical report of the 2007 population and housing census results. Available at: http://journal.um-surabaya.ac.id/index.php/JKM/article/view/2203

CSA (2013a). Federal Demographic Republic of population projection of Ethiopia from 2014–2017: population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Woreda level from 2014–2017. CSA: Addis Ababa

CSA (2013b). Population size by sex, area and density by region, zone and Wereda: July 2022. CSA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Debele, E. T., and Negussie, T. (2021). Growing urban housing consumption and housing policy development trends. Sage. doi: 10.31124/advance.13640627

Derg (1975a). PROCLAMATION No. 31 OF 1975: a proclamation to provide for the public ownership of rural lands. Ethiopia: The Derg Government, Addis Ababa.

Derg (1975b). Proclamation No. 47/1975: a proclamation to provide for government ownership of urban lands and extra urban houses. Ethiopia: The Derg Government, Addis Ababa.

FDRE (1995). The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia constitution. Available at: http://www.ethiopianembassy.be//pdf/Constitution_of_the_FDRE.pdf

FDRE (2002). Proclamation no. 272/2002: re-enactment of urban lands lease holding proclamation. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa.

FDRE (2011). Urban land lease holding proclamation Proclamation No. 721/2011. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa.