- Department of Humanities, College of Arts and Sciences, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

The State of Qatar has witnessed rapid urban activity and development in the decades since the discovery of oil, which has led to a large-scale change in the local cultural heritage and behavior of its residents. This uncontrolled rapid urbanization, along with the acceleration of globalization and modernity that has encompassed all areas, especially the city of Doha, has led to the deterioration and destruction of the downtown area of Msheireb. These transformations threaten the identity and local culture of Qatari society, affecting the place's sense of identity. The country's authorities have rushed to implement strategies and development plans aimed at redeveloping the old city center and improving the environment by creating innovative and inspiring living spaces that enable both locals and foreigners to communicate and integrate with one another to restore a sense of community. This study addresses the “Msheireb Downton Doha” project and the consequences of globalization. The study examines the concept of “deterritorialization” as a cultural condition that has pushed Msheireb Downtown Doha from modernity to postmodernism as an element of globalization. In this study, we will analyze the reconstruction of Msheireb, which helped to move the city toward cultural universality while simultaneously reducing regional borders. The study will analyze the extent to which this process succeeded or failed in preserving the spirit of the area's traditional architectural heritage and cultural identity in a manner that reflects the genuine sentiments and values of Qatari society.

Introduction

Recently, the landmarks of many cities in the Middle East have been subjected to change, to the point that they have nearly lost their cultural identity. This loss of identity has resulted from the continuous demolitions and new construction affecting many old neighborhoods, especially in light of the steady acceleration toward modernity and new insights regarding economic, social, and cultural spaces that have resulted from globalization. These changes also result from complex and diverse migration patterns that are reflected in expressions of culture, identity, and affiliation. It is worth mentioning that very few governments have taken the initiative to develop plans to preserve heritage areas, which are under threat (El-Sherbiny, 2020).

The State of Qatar was one of the first countries to develop plans and take practical steps to rebuild its city center and its old neighborhoods, preserving their legacies for future generations. The city was redesigned according to a new architectural landscape, while its foundation was derived from the past. However, it was designed with a modern layout, producing a smart city based on the principles of environmental sustainability (El-Sherbiny, 2020). The architectural design and urban planning of the city addressed several elements of Qatar's traditional architecture in an attempt to preserve the original characteristics of old Msheireb City. The historical and traditional urban planning of the area were analyzed to determine the prevailing features and create architectural designs inspired by traditional Qatari architecture.

This study addresses the following questions: Does the current city of Msheireb represent the history, heritage, and spirit of old Mesheireb? Does Msheireb enhance the image of Qatari cultural heritage? Alternately, does it represent a new image of globalized Qatar, thus deterritorializing Msheireb from its own culture and enabling a different culture to exist?

This study will examine heritage preservation within the “Msheireb Downton Doha” project to determine the extent of the success of globalization in Qatar and its ability to blend the elements of local heritage with global cultures (Al-Jabri, 1991).

The fundamental questions in this study are as follows: Does the current globalization strategy and postmodernism weakened Qatari cultural identity? Or does it render other cultures “less foreign”? Perhaps these trends bring Qatar closer to the cosmopolitan and reduce the gap between contemporary societies and those of past and future generations (Al-Sayed, 2010). When new ideas or features are introduced and incorporated into existing structures, what are their consequences for societies, institutions, and individuals? How does society react to the inevitable transformations that are occurring in the Msheireb neighborhood? Does the new urban planning, which brought new lifestyles into the old neighborhoods, enhance the city's original identity, or does it damage the spirit and origin of the city?

Deterritorilization: an essential feature of globalization

Deterritorialization is a concept first developed by French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Felix Guattari. It was first introduced in their book A Thousand Plateaus in 1980. Later, they encouraged the concept's broad application in other areas of the humanities and within diverse contexts (Glanzner et al., 2012).

Deleuze and Guattari's (1980) conceptual thinking has consistently demonstrated the potential movement of concepts between the humanities and the social sciences. Moreover, it has fostered the development of a common conceptual vocabulary in research. For Deleuze and Guattari, deterritorialization describes the process that pushes a territory away from some preexisting entity, opening borders and enabling a different other. It is a process of liberating oneself from the existing fixed relations and exposing oneself to new forms of transformation. It is not a real escape, but rather a departure from foundations to other areas, which may be violent at times (Deleuze and Guattari, 1980). The concept also refers to the process of detaching social, political, or cultural practices from their places of origin as a result of various factors, such as the development of communications, migration, and commodification that characterize modernity. Deterritorialization is a process that can be understood as the diffusion of local cultural experiences across borders. Thus, this study uses the concept of deterritorialization to analyze and describe the cultural situation under globalization. De-bordering is an essential feature of globalization, which refers to the increasing shapes and forms of communication and social ties that extend beyond the borders of a particular region. This is a type of social relation that leads to closer participation with external entities.

Arjun Appadurai broadly defined deterritorialization in his book Modernity at Large Scale: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (1996) as one of the central powers of the modern world. The terms refers to the fertile land in which money, goods, and individuals are involved in the ceaseless pursuit of one other around the world, in which the media and migrants find their scattered counterparts in the world (Appadurai, 1996).

In her study “The Deterritorialization and Reterritorialization of Artistic Research”, Darla Crispin analyzed the concept of deterritorialization as it relates to movement and the dynamism of change. She stated that it is a constant product of unique actions, which are similar in their mechanism to airplanes that take off from a reliable position. However, they liberate themselves from what they were earlier by following the way of change and innovation facing other cultures, be it in character, idea, space, or individual (Crispin, 2019).

In the context of this study, the concept of deterritorialization transcends the philosophical concept and is reemployed to better describe cultural transformation in Msheireb. Deterritorialization is used here as a lens that enables an analysis of cultural transformations within the framework of the state's eagerness to manage and preserve the city's architectural heritage. This perspective also allows for the construction of a new creative language that accommodates local cultural heritage in a wider environment. Thus, the old town stands along with the new city: non-resistant, open, and exposed to different cultures. This study will demonstrate the extent to which such an experience is successful in either enhancing or isolating the city's cultural heritage, as well as in eliciting new cultural components and elements as opposed to reducing the space of local identity. It also explores the implications of these overlaps on traditional values.

Perhaps it is also useful to examine the concept of heritage for its great importance in the cultural and architectural discourse, as it denotes cultural identity. Although there is no unified term that would define heritage, the term encompasses the natural and cultural environment. Heritage extends to the urban heritage of buildings – their formations and spaces – that have been able to withstand changes during different processes of development. It also encompasses architectural heritage, including the least valuable buildings in the old cities, which are an integral part of the cultural heritage (Abu Leila, 2019).

Heritage is defined in the “World Heritage Convention” as the collection of landmarks, sites, and buildings (UNESCO, 2016). Heritage plays a qualitative role in shaping the features of any region because of the values and dynamics people have experienced and practiced within the region. Such practices and experiences help communities create a strong sense of belonging and connection and thereby contribute to the crystallization of their social identity. Therefore, heritage preservation is a vital matter and a priority in the policies of any society during the process of modernization and globalization.

Without doubt, globalization means opening the community to many different societies in which cultural identities and economic models are diverse, new, and exotic (Saad and Abdel, 2015). Therefore, governments should consider that heritage sites are often endangered due to urban development plans. The conscious management of heritage sites has become an issue of great importance to all countries, especially those who signed the “World Heritage Convention”, as Qatar did in 1985, with the aim of preserving and managing heritage sites (UNESCO, 2016). What is present in Msheireb currently—a Qatari heritage or a new heritage?

Origin and development of Msheireb downtown Doha

Historical background

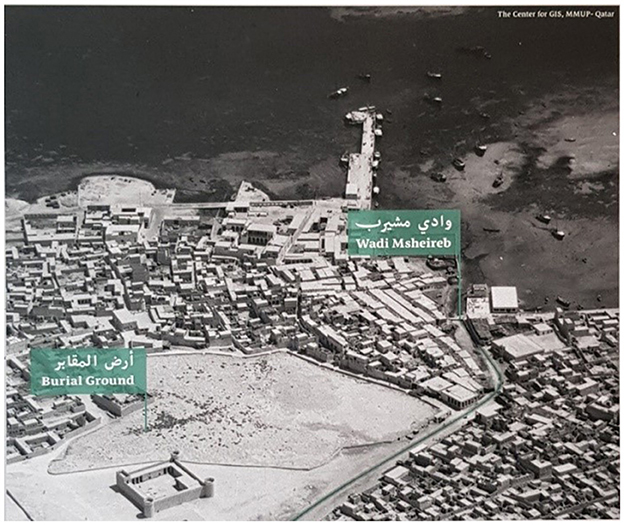

First, it is necessary to briefly examine the emergence and development of Msheireb (Figure 1) to clarify its historical roots. Knowledge of Msheireb's background is beneficial for studying and analyzing the radical transformations it has undergone. The Msheireb area is located west of the city of Doha, and the word Msheireb means “a place of drinking water” in the Qatari language. The area began as a suburb that was built around a generous well, which was large enough to serve its surroundings. Consequently, members of the Qatari community settled there (Msheireb Properties, 2021b; Al-Hammadi, 2022).

Figure 1. An aerial photograph of the city of Doha, 1952, showing the course of Wadi Msheireb passing through the cemetery grounds to the sea (Source: Msheireb Memories Exhibition Archive. Mohammed Bin Jassim Museum).

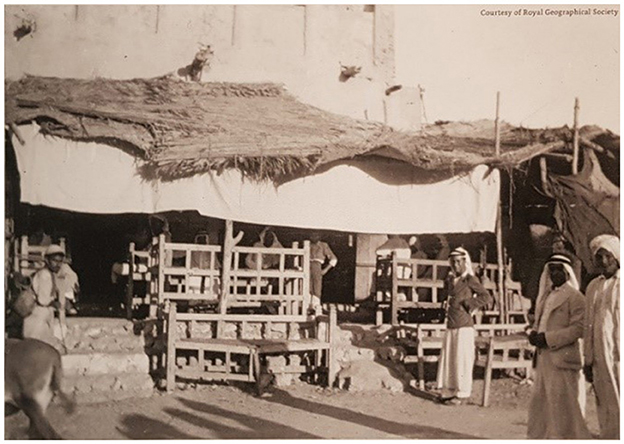

The Msheireb area has undergone numerous changes over the past decades. Its importance has fluctuated since it began as a base for pearl trading, diving, fishing, and retail in the late 1920s (Figure 2). The city experienced decline and the migration of much of its population during the economic downturn that followed the discovery of artificial pearls during the late 30s and beginning of 40s. The area regained its popularity in the 1950s with the discovery of oil, which is considered a turning point in Msheireb's history (Martí, 2006). The city has witnessed rapid growth and radical changes, with the Wadi Msheireb becoming a distinct morphological structure as well as a vital administrative and commercial center. It served as a destination for citizens and newcomers and was distinguished by its diverse communities, cultures, and groups that enjoyed a harmonious coexistence Zetter and Watson (2006).

Figure 2. Photograph of the market in Doha early twentieth century: the first development of Msheireb (Source: Msheireb Memories Gallery archive, Mohammed Bin Jassim Museum).

Within two decades, the area moved from one historical era to another as the country opened to the modern world and its changes. This period was associated with the boom of oil revenues and wealth in the Arabian Gulf region and Qatar. Without doubt, that boom played an active role in the development of lifestyles and consumption patterns. The construction movement flourished with the introduction of modern materials such as bricks and cement. All of these developments led to an influx of labor and the recovery of the market movement in the region (Al-Shalaq et al., 2014).

First phase of change

In the 1970s, the State of Qatar, like many Gulf countries, rushed to accommodate urban development through construction plans and civil engineering. It resorted to demolishing old buildings and adopting modern architecture to stay abreast of international developments. Architecture was regarded as an indication of the state's modernity. It was not surprising that Gulf countries scarified their traditional urbanism and architecture during this time, as it was perceived as an obstacle to the region's development process. Demolition and rebuilding plans were advanced further, especially with the need to develop the city's infrastructure (Al-Hammadi, 2022. The Qatari government prepared comprehensive urban plans for the city of Doha, focusing on the construction of a series of roads and building the necessary infrastructure. Those plans resulted in Qataris moving from traditional towns (such as Msheireb) to new urban areas. Msheireb soon became an overcrowded residential area for foreigners.

The unplanned openness and rapid development that accompanied the modernization processes in the Mushaireb area, with the aim of keeping pace with global developments, introducing new commercial forms (such as shopping malls and indoor facilities). Such constructions have negatively affected urban and architectural heritage, whether physically, visually, or both (Figure 3) (Scharfenort Nadine, 2013). In addition, the movement of Qatari citizens to new urbanized suburbs due to the severe overcrowding in Msheireb negatively affected the social fabric and led to a change in the social structure. The inhabitants, who came to Msheireb from diverse nationalities and cultures and included mostly labors and members of the working class, contributed to the town's deterioration. There was a clear negative association between the new residents and the surrounding architectural heritage, which resulted in neglect, destruction, and damage to the exterior and interior elements of the buildings (Khalil and Khaled, 2021). Gradually, the old Doha Center in Wadi Musheireb lost the community, its spirit, and its identity in the process of modernization, along with its previous economic and social importance to the bulk of the population. The Msherib area remained a hub for Asian laborers for around two decades, where they resided or shopped. Al-Kahraba Street became famous as a meeting point for single Asian workers, who flocked to it from all over Qatar during the weekends. It worth mentioning here that Al-Kahraba Street “which means electricity street” acquired its name because it was the first street to be illuminated by electricity.

Figure 3. An image of Abdullah Bin Thani Street, one of the main streets in the Msheireb area, showing the deterioration of the visual composition and the dire condition of the buildings (Source: Unknown).

Msheireb's heritage: Deterritorialization

Second phase of change

Over the course of its development plans, the Qatari government recognized what traditional architecture represents for Qatari cultural heritage and its role in enhancing and establishing the necessary cohesion between architectural design and the surrounding environment. Thus, the government developed a plan to transform Msheireb into a postmodern site that met all the requirements of twenty-first century smart city but with a Qatari spirit. The project aimed to extract Msheireb from the state of alienation that it experienced for two decades and return it to the embrace of its Qatari heritage. The intention was to create a clear cultural identity by making elements of Qatari architecture a main inspiration in Msheireb's rebuilding. Without doubt, heritage, culture, and the arts are important components of soft power that provide countries with unique opportunities to globalize and compete in global markets (Scheffler et al., 2009).

The government has played a prominent role in reviving several heritage sites that have deteriorated in previous decades, such as Souq Waqif. Likewise, Msheireb has received special attention and has embarked on a large-scale renovation. The goal was to create a postmodern site rooted in tradition, where worldwide cultures encounter one another but do not dissolve (Scharfenort Nadine, 2013). Regardless of the deteriorating state of the area, it is still a significant site located in the heart of Doha and serves as one of the main east–west arteries in the city. The historical Souq Waqif is located to the east, bordered to the north by the Emiri Diwan and the picturesque Doha Corniche on the waterfront. Msheireb is interspersed with many roads and passageways, as well as the two of Doha's very important streets, Al Kahraba Street and Abdullah bin Thani. In addition, it hosts various buildings with historical meanings and symbolic values due to their association with Qatar's history (Msheireb Properties, 2021a).

The government has presented itself as a responsible actor in addressing the society in the world's map while protecting its identity. His Highness the Amir and the Qatar Foundation have strengthened efforts to protect national architecture. The Msheireb Properties company was established to specialize in real estate development. It is a subsidiary of the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science, and Community Development. In 2008, through Msheireb, the government launched the “Msheireb Downton Doha” project, involving an area of thirty-one hectares. The project aimed to redirect value and attention toward the city center, fostering a new urban identity that is aligned with global progress without breaking with the past (Msheireb Properties, 2021b). The Msheireb Properties Company took over the project involving the rebirth of downtown Doha. It reinterpreted the area's historical legacy as one of the project's main pillars and drew inspiration from its architectural elements to produce a synthesis that evokes standards of quality, safety, and sustainability and which also serves as a reflection of postmodernism in the face of tradition.

The “Msheireb Downton Doha” project was a long-term investment. To achieve its vision and design a comprehensive smart city, the government unified the land's ownership by purchasing the traditional residential neighborhoods in the area (Al-Sharq, 2014). This was followed by the demolition of old houses to clear the place and prepare the land for rebuilding in accordance with the city's new designs and vision (Figure 4). It worth mentioning that the government decided to preserve four old houses that have historical value and meaning because they represent Qatari cultural heritage and history in the post-modernized area (Msheieb Museums, 2023).

Figure 4. Impact of demolit.ions in Historic Msheireb (Source: Reports: Building collapses in Musheireb this morning. Doha News Team, October 2011).

The first task in this project was to conduct an extensive study and analysis over 3 years to develop an innovative architectural language which would allow the spatial bonds between the past, present, and future to disappear. This architectural language took inspiration from Qatari architectural heritage. Those elements and symbols would serve as main components for preserving identity (Msheireb Properties, 2021b). Directed by “strong Islamic and family values”, Msheireb Properties has set out to achieve the strategic goals of Qatar Vision 2030 and contribute to the Qatar Development Program. Moreover, the company aims to preserve cultural traditions, which is a challenge that most countries face during their globalization process (Melhuish et al., 2016).

The project engineers developed an urban blueprint based on an extensive study of the characteristics of traditional buildings. They developed an architectural approach from a sustainable perspective that was inspired by heritage. The approach included the following seven principles: continuity; harmony through a common architectural language; utilization of the spaces between buildings; preservation of privacy; the activation of vibrant roads and streets; environmentally friendly designs that save energy; and a new architectural language that blends modern architectural elements with the past (Msheireb Properties, 2021b). However, this process created two dilemmas for the company because it required new designs for regionalization. New, creative methods have been necessary, which differed from those applied in the rebuilding of other areas, such as Souq Waqif or Souq Al-Wakra. The vision was to create an area that allowed an intermarriage between modernism and the past to create a postmodernized area. In this sense, dismantling borders and deregionalizing the area was necessary in order to develop an appropriate architectural language that combines the past with the future (Crispin, 2019).

The production of a new city: “Msheireb, the heart of Doha”

The need to establish a new urban identity and character for Msheireb was fundamental in creating a new image for the city. This process involved utilizing the elements of local cultural heritage and reformulating them to create a new architectural language, which is dynamic and reflects the spirit of the past rather than directly replicating it (Abdel and Abdel, 2012).

The consultants developed a blueprint for a cohesive urban neighborhood that would provide a balanced and flexible mix of land uses, including public domain and social and cultural infrastructure. The plan needed to account for traditional architectural values and respond to climate considerations in order to reduce the impact of heat, cars, congestion, and water demand. It was also necessary to design smart buildings to reduce the need for cooling and to introduce new, high-quality public spaces to facilitate community interaction and social exchange. Furthermore, a heritage square was created to interact with memory and address Qatari heritage within the new urban formation in Doha's current city center. The master plan was based on references from Qatar's historical urban form and the creation of the traditional concept of “Freej”, which means neighborhood in traditional Qatari, that was used to develop postmodern Msheireb on the basis of Qatari tradition and identity (Khalil and Khaled, 2021). The integrated city center was designed with concepts of sustainability and green architecture in mind that align with the Qatari environment. Situating facilities and amenities within walking distances allows neighborhoods to form a compressed urban pattern rather than consisting of scattered buildings, each in their own plot of land. The compact design offers many advantages in terms of creating shaded streets that encourage residents to walk (Khalil and Khaled, 2021).

Msheireb is surrounded by five main areas that encourage social interaction. The first is Amiri Diwan, with its several sections supporting it. Second is the main square, Al Baraha, which is the main outlet for the entire Msheireb area. This area also includes residential buildings, offices, and other dynamic spaces. The third area is the retail district, which is the largest area and contains the most luxurious spaces in the city of Doha. Fourth is the Business Gate District, which is a commercial area that will be promoted for business opportunities and government commissioners to accelerate future investments in the city (Boussaa, 2017). The fifth area is the only physical witness to the past at the gates of the city of Msheireb. Its main entrance receives local and international visitors from the nearby Souq Waqif. It provides a cultural pathway for visitors to relive the history of Qatar prior to 1950. It is the main gateway to Msheireb, which acts as a catalyst for the creation of a new urban identity for the entire area. This heritage and cultural square consists of four old houses, which were preserved through transforming them into museums. Consequently, the heritage area has become a major tourist attraction in Msheireb (Boussaa, 2017).

Msheireb Properties also recognized the importance of Al-Kahraba street. The street was once a center for social interaction and economic activities (Msheireb Properties, 2021b). It is the area from which the original town of Doha expanded to become the modern city of today. Creating a new image of Doha involved considering the features of the old site to enhance the spatial ties between the past and the present. Therefore, Al-Kahraba and Abdullah bin Thani Streets were included within the streets of the new city. The plan aimed to revive the area and return it to its former state, with the goal of restoring its commercial activities. Another aim was to preserve its historical urban values for the purposes of sustainability and keeping pace with global progress (Boussaa, 2017).

The project prioritized the protection and care of heritage-themed environments and areas, including buildings, public squares, spaces between buildings, and other urban elements (Fadli and AlSaeed, 2019). Many levels of architectural heritage preservation occurred in the Msheireb area, such as the restoration and renovation of the historical fort Al-Kut and its surrounding. It also included the restoration of the Musalla Al-Eid, which means “an open space for Eid prayer”, an area that is still vivid in the memory of the people of Qatar that dates back to the first decade of the last century. Another restoration project involved the house of Sheik Mohammed Bin Jassim, son of the founder of modern Qatar, which is distinguished by its design and the originality of its architectural heritage (Msheieb Museums, 2023). Bin Jelmood House is considered one of the most important historical installations, dating back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The house was preserved to convey the history of slavery in Qatar and the region (Al-Mulla, 2017). The company's house represents a historical period that constituted a dramatic leap and was followed by an economic boom, when the country moved from an economy based on pearl diving and fishing into a major oil and gas exporting country. The house was a headquarters for the first English company that arrived in Doha to work in the oil fields (Al-Hammadi, 2022). Al-Radwani House is distinguished by its preservation of the original architectural features and design. The house represents the lifestyle of Qataris prior to the discovery of oil by displaying a series of tools and a collection of pottery and antiquities that the research team uncovered during their excavation work. Those four houses have been converted into museums, which are located in the Heritage Quarter of Msheireb as a cultural path that connects the visitors to the past and offers them an opportunity to experience Qatari cultural heritage (Al-Hammadi, 2022).

The Msheireb area has been conceptualized through the best modern technology to transform the central zone from a dilapidated immigrant neighborhood into a new, postmodernized neighborhood. This new Qatari urban landscape will promote a global lifestyle rooted in Qatar's collective memory and identity. The design distances itself from Western models through a cross-border architectural design that blends Western and traditional Qatari and Islamic architecture. This blend can be seen in the white stone semiclassical buildings and the residential villas, whose traditional character incorporates Qatari culture and family privacy. The same is true of the commercial area located in the residential neighborhood, which was designed to provide the youth with a lively and vibrant area (Melhuish et al., 2016).

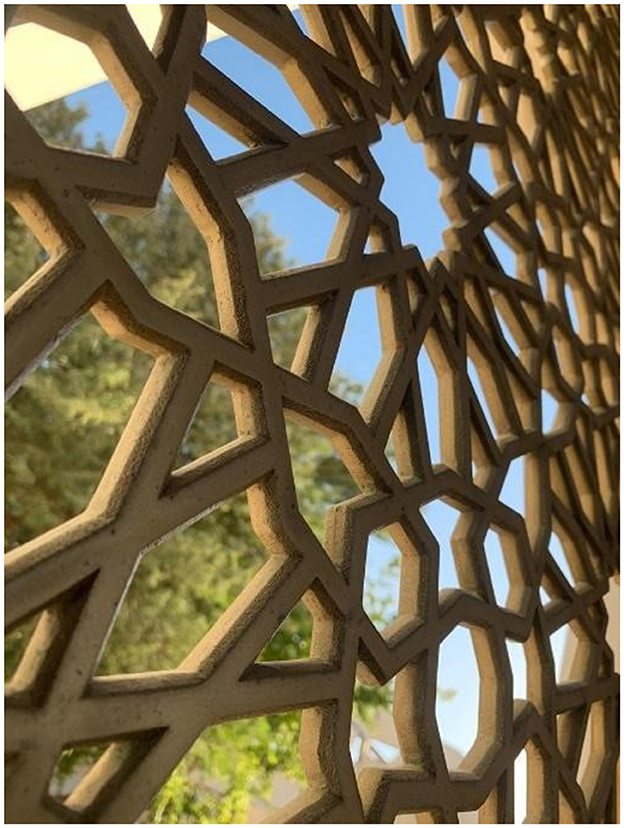

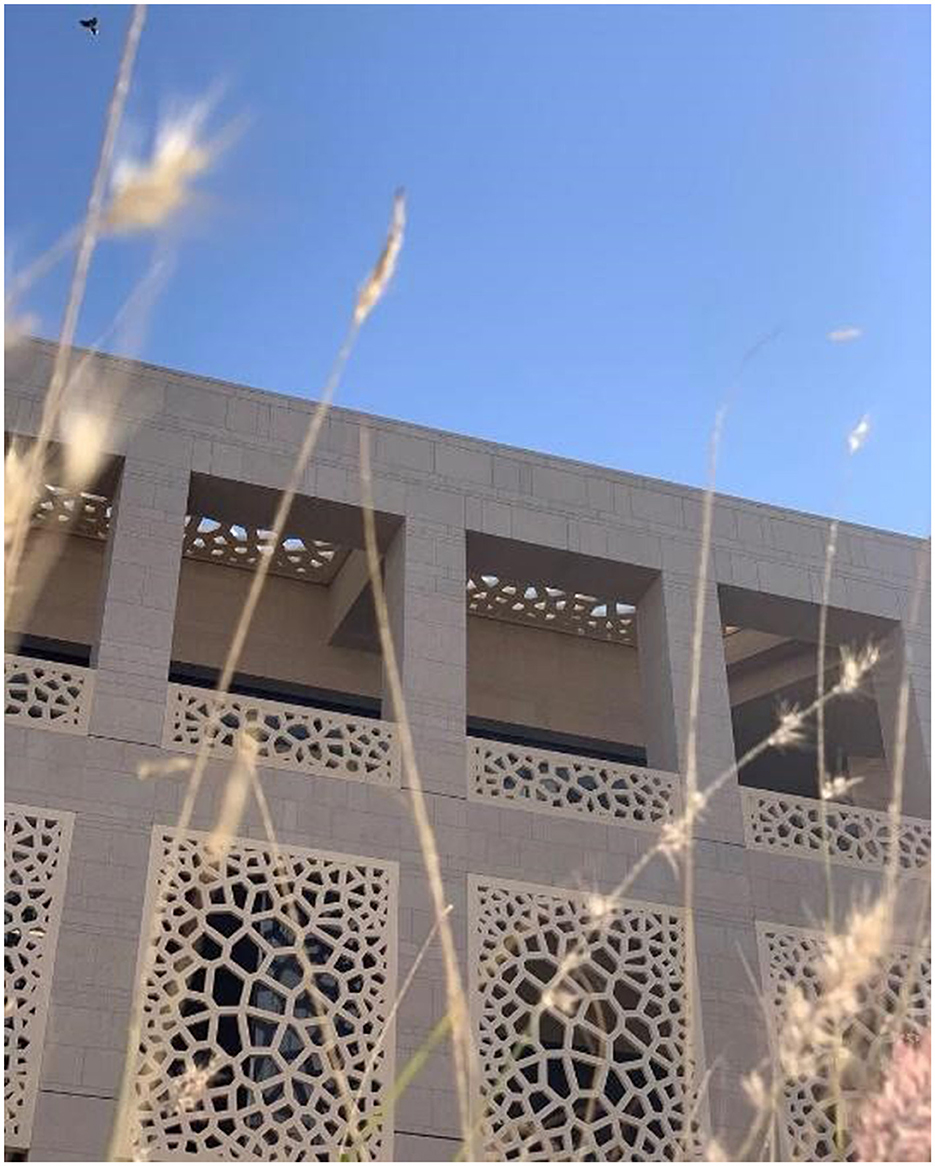

The combination of traditional architectural elements and Western details in Msheireb was intended to reduce the distance between the local and the global (Gharib, 2014). Thus, large decorative touches and inscriptions inspired by Islamic architecture are used in the façades. Historically, these designs, known as mashrabiya or shanasheel, were used in Islamic architecture at the windows to provide privacy, as the insider can enjoy looking from the windows, but outsiders cannot see inside the houses (Al Hawam, 2021) (Figures 5–7).

Figure 6. Adorn the frontage of one of the new buildings in Msheireb (Source: Msheireb Properties website).

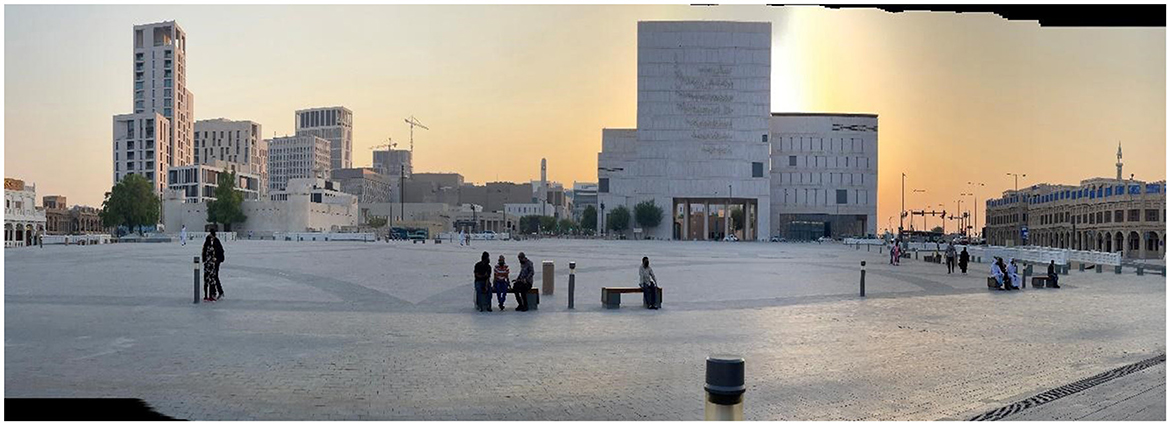

Figure 7. Barahat Al Nooq is the central public square in Msheireb Downtown Doha. (Source: Msheireb Properties website).

To render Msheireb as lively and vibrant as it once was, it was necessary to create public spaces to host social events and programs. Although the idea of public squares is not new (it was an old tradition in Western civilization), the idea did not previously exist in Qatar. To prevent compromising the cultural heritage of Qatari society, the public space of Barahat Al-Nooq (Figure 8) was created by drawing inspiration from the Qatari majlis, where visitors are received in Qatari homes (Melhuish et al., 2016). Al Barahat is considered an urban majlis for residents and visitors and is used for entertainment, especially during the festive period and national events.

Figure 8. A front view of the new city of Msheireb, in which the lack of physical and visual compatibility is clearly seen with its neighborhoods such as Souq Waqif. Note the variation in the lengths and colors of the buildings (Photo by Mahboobeh, on September 25, 2021).

Barahat Al-Nooq succeeded in mixing modernity and originality and creating an architectural synthesis that reduced the boundaries among Western thought and local specificity (Martí, 2006). Msheireb Property innovated ways to prevent scarifying Qatari cultural heritage within the new city of Msheireb. Instead, the company's efforts in Msheireb endeavored to address Qatari cultural heritage within a wider global context. Consequently, Msheireb was redeveloped based on the notion of building a new city with a genuine Qatari heritage. However, Qataris must exercise caution in considering this heritage. It is necessary to differentiate between a presentation of a genuine Qatari heritage and an interpretation of that heritage.

Does downtown Doha embody a Qatari heritage or a new heritage?

Msheireb Downton Doha is a city built on architecture that derives its pillars from the past while implementing modern planning based on the principles of environmental sustainability. Msheireb Properties has become an agent of change that has sought to revitalize the downtown area of Doha with a new architectural language inspired by Qatari heritage to re-create the local experience and develop transnational ties that blend postmodernism with local culture. The protection of the heritage area was regarded as necessary to express the identity of the place and to increase the sense of belonging, especially in light of the rapid technological growth that the country is experiencing (Crispin, 2019).

One of the main design pillars that must be considered when rebuilding any city accounts for historical characteristics and the prevailing natural, social, and cultural environment of the region (Abdel and Abdel, 2012).

Msheireb has incorporated a new architectural language, but this has caused the old Msheireb to disappear. The spirit of the place and its historical features no longer exist within Msheireb. What is presented there is not the original heritage but a new heritage. The process of reactivating Msheireb reflects the desire and intention to promote deterritorialization and open boundaries to make Msheireb an ideal example of globalized Qatar. Promoting the city's advancement toward globalization contributed to a profound shift in the relationship between the place and its people. This approach replaced the area once frequented by members of all segments of society with an area targeting the affluent. This is evident especially in the residential area of Msheireb, which moved away from serving as a residential suburb for the low-income community to make way for luxury housing inspired by tradition. In addition, adding a luxurious commercial area and high-end hotels has attracted investors and tourists alike (Mahgoub and Reham, 2012).

Moreover, the owners of the traditional shops and small restaurants that were known in the area, such as samosa and Pakistani sweet shops, have been asked to relocate to other parts of Doha. Their small and modest shops were demolished in order to make way for international chains or other businesses, and to foster the image of a globalized city. Furthermore, the owners of these shops were unable to return to the area after its rebuilding due to the type and standard of business required to bring in new visitors and shoppers. Moreover, the rent is currently high compared to what was in the past, thus preventing these shop owners from continuing to trade in the city. The demolishing of those small shops meant the loss of one facet of Qatari custom and heritage. Although those shops served Pakistani and Indian food, they became part of Qatari custom and heritage, especially during Ramadan month, when people would queue for hours to get different types of samosas as a starter. Those shops became part of Ramadan ritual and characterized part of the place's cultural identity.

Usually, the cultural identity of a place lies in the characteristics that make it unforgettable, such as names or symbols that allow individuals to remain connected to the past. In the case of Msheireb, these symbols were lost, however, and only two streets kept their names: Al-Kahraba and Abdullah bin Thani. Those streets changed from being small market areas that attracted mid- and low-income people into a commercial area characterized by the presence of distinctive brands. Thus, the streets lost their original spirit (Boussaa, 2017). The experience created by globalization is complex, and the effects have generated both praise and criticism. Some believe that globalization has led to modernization and universality, while others feel that the old city center has lost its collective memory, charm, spirit, and cultural identity because of such transformation. They compare other nearby areas to Msheireb, such as Souq Waqif, which successfully preserved the essence of its cultural identity with the essence of the past and managed to attract all social classes, reduce regional boundaries, and popularize its local heritage.

It is important to develop historical foundations through conservation strategies that preserve the city's historic characteristics and traditional values for future generations without hampering its current use. Therefore, the revitalization of the city center is a unique experience in reinterpreting the past in a contemporary way so that it maintains the elements and spirit of Qatari traditional architecture. However, the demolitions and removals that occurred at the beginning of the project caused the loss of many historical buildings that would have linked the history of the region to the present (Fadli and AlSaeed, 2019). The link between the past and present in Msheireb only represents between 1 and 2% of the total area, which includes the cultural quarter and the four museums mentioned earlier. However, there was an opportunity to preserve a larger historical area than this small quarter, which could have enhanced the historical spirit and local culture of Msheireb further by placing these aspects at the heart of the process of mixing and fusing local and global culture (Martí, 2006).

The limitations of heritage presentation highlight whose history is represented and which experiences are reflected. Moreover, the use of local architectural elements in the designs reflect that values and ideas are referenced in the creation of a new heritage. In fact, such practice demonstrates the inherent contradiction in Msheireb Properties's claim of preserving Qatari cultural heritage. The company is instead creating and presenting a new and diverse cultural heritage. Thus, the new Msheireb Downton Doha actually reveals a form of new culture and heritage, by making the local global and the global local. This decisive point also reflects the vital role such real estate can play in reshaping the cultural heritage of the country. Msheireb Properties has promoted reform in traditional Qatari architecture and produced from it an inclusive heritage (Edson and David, 1994). There is no doubt that the architectural language of Msheireb Downton Doha strongly reflects a simulacra role in which the new form of architecture combines interpretation, metaphor, and imitation rather than presentation (Baudrillard, 1981; Al-Hammadi, 2017). The Msheireb project situated the notion of Qatari architecture within a wider context, permitting the creation of new heritage concepts that have no origin in Qatari heritage. Such a practice of real estate reflects the power and wealth that allowed for the change. Qatari architecture in Msheireb is no longer itself; it is a simulated architecture that aims to reflect Qatar's modernity and its globalization strategy (Al-Mulla, 2013).

Reconstruction of cultural identity and the public's reaction

“Msheireb, the Heart of Doha” reconstructed the cultural identity of the place. There is a clear contrast between the heritage of neighborhood locations and the other parts of Msheireb. However, the city lacked an appropriate visual and physical profile compared with neighborhoods such as Souq Waqif, Al Asmakh, and Al Najada. The new three- to thirty-story buildings built on the outskirts of Msheireb create a line of obstructions that block any view toward those neighborhoods. This reflected negatively on the four museum buildings in the Heritage Quarter, whose landmarks are now hidden among the high buildings. To understand locals' reaction to the creation of new Msheireb, we interviewed locals who have owned shops in nearby areas of Msherieb for decades and witnessed the history of the area, including its new changes. Ali Muhammad Sadiq, who owns a shop at Souq Waqif, commented on the new development:

The modern buildings of Msheireb lack coordination in terms of visual configuration. It would have been better to consider the coordination between the buildings of Msheireb and the buildings of Souq Waqif so [as] not to cause a break when looking [Interview on October 9, 2021].

The Msheireb project sought to create a sense of familiarity, homogeneity, and cohesion in the environment through physical designs. The design took the assemblage of houses into consideration to create contemporary spaces and enhance the sense of belonging to the community. The idea succeeded within the city; however, it failed to expand this cohesion between different parts of the city. The lack of continuity with neighboring areas created a visual divergence between Msheireb and its surroundings, thus weakening the city's urban identity.

Therefore, the embrace of the postmodern architectural model has reduced the identity of the place (Boussaa, 2017). Reflecting on that concept, Hassan Salem Al-Mansoori, another shop owner at Souq Waqif, stated:

Previously, the buildings [were] made only one or two stories high, with the use of different construction materials. Now the buildings are between eight and ten stories. We can see that these buildings have borrowed some Qatari architecture features, such as “badgers”. However, they are nothing, none of them actually represent the old days. They lost their original identity. I think the developer must modify the new architecture according to the old style, and give them back their real identity. Those who do not have the past ultimately will not have the future [Interview on September 25, 2021].

Glanzner et al. (2012) define identity as what is “produced, consumed, and regulated within culture-creating meaning through symbolic systems of representation about the identity positions which we might adopt” (2012, 48–49). Identity is therefore a sense of belonging to a specific culture and social group. Cultural identity is not static; it changes over time according to different circumstances. The reconstruction of cultural identity is meant to produce cultural proximity, making the gap between the self and the other narrower. Thus, cultural identities are usually reconstructed under changing cultural conditions in which foreign cultures have an influence. Nonetheless, this process has a positive effect on the individual. As an individual absorbs foreign cultures, they increasingly notice the differences of meaning rather than the similarities. Consequently, this process can lead to the enhancement of the individual's cultural identity (Glanzner et al., 2012). Globalization has led to fundamental changes in landscapes and urban planning, which make it harder for people to identify their cultural identity amid the new developments (Colmore, 2017). Ali Muhammad Sadiq, a Qatari local who gathered daily with his friend at Barahat Al-Jaifiri (a large, open majlis next to Msheireb) commented about the new reconstruction:

The old spirit no longer exists, the area was supposed to allow al-sheeban [the elderly men] to be presented in the area through preparing a large majlis that gathers both the elderly and adults. A consideration of such traditional daily activity would contribute to restoring the cultural identity of the place (Interview on October 9, 2021).

In her article “Rebuilding City Identity through History: The Case of Bethlehem-Palestine”, Jane Handal claims that the cultural identity of a place is a continuous process of constructing and reconstructing. This process is controlled by two forces: (a) an emotional force that is represented in collective memories and forms of cultural heritage, and (b) a rational force, which is represented in the ability to absorb the movements of globalization, production, and economic competition. These two forces form the cultural identity and urban landscape of any place. Their compatibility leads to the structuring of the place's cultural identity, and incompatibility between them leads to the destruction of that identity. These forces are produced and reformed by human agency (Zetter and Watson, 2006).

In the case of Msheireb, the role of this rational force was apparent in reshaping the city's cultural identity. Urban planning and designs were subject to the review and approval of higher authorities, especially following the government acquisition of the area. This process excluded the emotional aspect because the local community was not involved in making decisions about the place. Therefore, their knowledge, cultural values, political memories, and interpretations of the city's cultural identity were not utilized. The emotional aspect has been reduced to four museums that serve the rational forces that are needed to promote the policies of globalization and deterritorialization. The new city moved away from its original essence and values, which inevitably inhibits a natural fluidity between the past and the future. The new urban planning detached the city from its emotional past, which is a component that would have helped maintain the place's sense of belonging (Zetter and Watson, 2006).

Conclusion

Msheireb's old city has been deterritorialized to allow the existence of the new Msheireb Downton Doha project. Therefore, the original Msheireb territory has been distanced in some ways from its preexisting state, and its borders have been opened to enable a different other. In this way, old Msheireb was liberated from its previous existence and exposed to a new reform. The old, dilapidated buildings have been replaced with modern ones, which have integrated local architectural elements with newly imported architectural elements and materials. The result is a postmodern architecture, which has permitted the creation of a new cultural identity (Abu Laila and Al-Barqawi, 2019). The aim was to create a city that attracts both residents and tourists. What distinguishes this approach is the attempt to form a distinct cultural identity and personality for the city that does not depend on reproducing the past but instead draws from it and simulates some of its elements. The project then integrates those elements in a way that suits the needs and requirements of a globalized community (Boussaa, 2021). It is a form of deterritorialization that detaches economic, social, political, and cultural practices from their original sites as a result of several factors, such as the development of new aspects that characterize postmodernism.

There is no doubt that the sustainability practices have been handled exceptionally well in all of Msheireb's buildings. However, the practice would have been more successful through increasing community participation. The identity of the city is a combination of the aspirations and experiences of citizens and visitors (Boussaa, 2021). When people meet their neighbors, gather with friends, and feel comfortable interacting with strangers, they tend to have a stronger sense of place and connection to their community. In the transformation process, the principal task is always to restore balance. Allowing the local communities to participate in the process of change from the outset is beneficial in rethinking the place, designing the future, and supporting the process of change rather than stopping it Zetter and Watson (2006) As Lynch (1972) stated, “if change is inevitable, it must be modified and controlled to prevent violent disintegration and renew maximum continuity with the past” (1972: 33). Thus, it is vital to preserve heritage without undermining intangible values in order to uphold a strong continuity with the past (Lynch, 1972).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by Qatar National Library.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdel, L., and Abdel, R. (2012). Inspiring Urban Heritage – From Reproduction to Rooting and Sustaining Architecture and Local Urbanism. Conference on Hosting Major International Events, Innovation, Creativity, and Impact Assessment. Cairo: The National Center for Housing and Building Research.

Abu Laila, M., and Al-Barqawi, W. (2019). “Methodologies for preserving Urban and architectural heritage in the Arab Countries,” in International Journal of Architecture, Engineering and Technology. p. 128. Available online at: https://bit.ly/3CwadLN (accessed September 27, 2021).

Abu Leila, M. M. S. (2019). Methodologies for preserving urban and architectural heritage in Arab countries. Int. Sci. J. Architec. Eng. Technol. 2, 127–144.

Al Hawam, W. (2021). The aesthetics of the roshan singular in hijazi architecture and the use of it in teaching ceramics. AmeSea Int. J. 7, 2185–2208.

Al-Hammadi, M. (2017). Reconstructing Qatari Heritage: simulacra and simulation. J. Lit. Art Studies 7, 679–689. doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2017.06.007

Al-Hammadi, M. (2022). Toward sustainable tourism in qatar: msheireb downtown doha as a case study. Front. Sust. Cities 3, 799208. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.799208

Al-Jabri, M. (1991). Heritage and Modernity, Studies and Discussions. Beirut: Center for Arab Unity Studies.

Al-Mulla, M. (2013). Museums in Qatar: Creating Narratives of History, Economics and Cultural Co-operation. PhD thesis, UK: University of Leeds.

Al-Mulla, M. (2017). History of slaves in qatar: social reality and contemporary political vision. J. History Cult. Art Res. 6, 85–110. doi: 10.7596/taksad.v6i4.1013

Al-Sayed, W. (2010). Heritage, Identity and Globalization – Basic Theoretical Approaches. Second Conference on Arts and Folklore in Palestine: Reality and Challenges.

Al-Shalaq, A., Mustafa, M., and Al-Abdullah, Y. (2014). The Development of Modern and Contemporary Qatar: Chapters of Political, Social, and Economic Development. Doha: Dar Al-Kutoub Al-Qataria.

Al-Sharq. (2014). The Emir Approves the Decision to Expropriate Some Real Estate for the Public Benefit. Available online at: https://al-sharq.com/article/04/02/2014 (accessed February 4, 2014).

Boussaa, D. (2017). Urban regeneration and the search for identity in historic cities. Sustainability 10, 1–16. doi: 10.3390/su10010048

Boussaa, D. (2021). The past as a catalyst for cultural sustainability in historic cities: the case of Doha, Qatar. Int. J. Heritage Stu. 27, 470–486. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2020.1806098

Colmore, L. (2017). Heritage on the move. cross-cultural heritage as a response to globalisation, mobilities and multiple migrations. Int. J. Heritage Stu. 23, 913–927. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2017.1347890

Crispin, D. (2019). The Deterritorialization and Reterritorialization of Artistic Research. ÍMPAR 3, 45–59.

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F. (1980). Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massum. London: The University of Minnesota Press.

El-Sherbiny, M. (2020). Designing strategies of newer buildings built within contexts of historical value. J. Urban Res. 37, 1–25. doi: 10.21608/jur.2020.108643

Fadli, F., and AlSaeed, M. (2019). A holistic overview of Qatar's (Built) cultural heritage; towards an integrated sustainable conservation strategy. Sustainability 11, 2277. doi: 10.3390/su11082277

Gharib, R. (2014). Requalifying the historic centre of doha: from locality to globalization. Conserv. Manage. Archaeol. Sites 16, 105–116. doi: 10.1179/1350503314Z.00000000076

Glanzner, B., Schlütz, D., and Schneider, B. (2012). The Self-Reinforcing Process of Cultural Deterritorialization: Intercultural Capital, Transnational Media Representations and Cultural Vicinity: An Empirical Study. 62nd Annual Conference of the International Communication Association. Phoenix, Arizona, USA.

Khalil, R., and Khaled, S. (2021). Rebuilding old downtowns: the case of Doha, Qatar. Real Corp. 2012, 677–689.

Mahgoub, Y., and Reham, A. Q. (2012). Cultural and economic influences on multicultural cities: the case of Doha, Qatar. Open House Int. 37, 33–41. doi: 10.1108/OHI-02-2012-B0005

Martí, G. M. H. (2006). The deterritorialization of cultural heritage in a globalized modernity. J. Contemp. Culture 7, 92–107.

Melhuish, C., Monica, D., and Gillian, R. (2016). The real modernity that is here: understanding the role of digital visualisations in the production of a new urban imaginary at msheireb downtown, Doha. City Soc. 28, 222–245. doi: 10.1111/ciso.12080

Msheieb Museums. (2023). About us. Available online at: https://msheirebmuseums.com/en/ (accessed July 31, 2021).

Msheireb Properties. (2021a). About Us. Available online at: https://www.msheireb.com/#welcome (accessed July 31, 2021).

Msheireb Properties. (2021b). History Downtown Msheireb. Available online at: https://www.msheireb.com/msheireb-downtown-doha/about-msheireb-downtown-doha/history/ (accessed July 31, 2021).

Saad, R., and Abdel, A. (2015). Cultural areas as reflected in folklore museums: sinai heritage museum in north sinai as a model. J. Sci. Res. Arts 16, 345–382. Available online at: https://bit.ly/3mv3wUq

Scharfenort Nadine. (2013). In focus n 1: large-scale urban regeneration: a new heart for Doha Int. J. Archaeol. Soc. Sci. Arab. Peninsula 2:532. doi: 10.4000/cy.2532

Scheffler, N., Kulikauskas, P., and Barreiro, F. (2009). Managing Urban Identities: Aim or Tool of Urban Regeneration? The URBACT Tribune. New York, NY: Academia Press, 9–13.

UNESCO. (2016). World Heritage Resource Manual: Managing World Cultural Heritage. Translated by Rita Awad and Zaki Aslan.

Keywords: Msheireb downtown Doha, cultural identity, Qatari heritage, Qatari identity, globalization, deterritorialization, architectural heritage, Msheireb city

Citation: Al-Hammadi MI (2023) Deterritorialization in the context of cultural heritage and globalizing Msheireb downtown Doha. Front. Sustain. Cities 5:1186781. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.1186781

Received: 15 March 2023; Accepted: 18 April 2023;

Published: 17 May 2023.

Edited by:

Esmat Zaidan, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, QatarReviewed by:

Asli Ceylan Oner, Izmir University of Economics, TürkiyePhilip Boland, Queen's University Belfast, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Al-Hammadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mariam Ibrahim Al-Hammadi, bS5hbGhhbWFkaUBxdS5lZHUucWE=

†ORCID: Mariam Ibrahim Al-Hammadi orcid.org/0000-0003-1589-0141

Mariam Ibrahim Al-Hammadi

Mariam Ibrahim Al-Hammadi