94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Cities , 27 November 2023

Sec. Social Inclusion in Cities

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2023.1163984

This article is part of the Research Topic Youth Vulnerabilities in European Cities View all 9 articles

This study aims to identify and present mechanisms through which the economic potential of European urban areas is converted into social inequalities among the young population in the field of housing. The role of national and local housing systems in this conversion is analyzed through the examples of Amsterdam, Tallinn, Chemnitz, and Pécs. These four cities represent four major ideal types with different levels of economic power and housing welfare structures. The article, through these case studies, initially delineates the ramifications of increasing housing demand arising from population growth and varied wage structures in cities experiencing economic prosperity. It also delves into the repercussions of population decline and financial constraints in cities with weaker economic foundations. Subsequently, it evaluates the efficacy of local housing policies in addressing housing affordability and spatial segregation, considering the presence of either a unitary or dual public housing sector. The article's conclusion underscores that local housing policies are tightly bound to national housing concepts, legislation, and resources, which constrains their capacity to adapt measures to the changing dynamics of economic development. The primary source of information underpinning this analysis is derived from research conducted in these urban areas as part of the UPLIFT project, funded by the European Commission within the framework of Horizon 2020.

The present study has a dual aim: first, to elucidate the principal structural impacts of the economic strength of European urban areas on their local housing markets, and second, to trace the resulting pathways leading to housing inequalities among the young population. In the context of this study, inequality pertains to accessibility (often referred to as short-term affordability), long-term affordability, and housing security for the younger generation entering the housing market.

While there exists an extensive body of literature on how growth pressure, or its converse, urban shrinkage, can influence the dynamics of housing demand and supply in European cities (e.g., Glaeser and Gyourko, 2005; Nijskens et al., 2019), relatively less emphasis has been placed on the generalization of the significance of local housing systems in shaping the ultimate outcome, specifically the impact on housing inequalities.

In this regard, our hypotheses take a two-fold approach: first, we posit that young individuals encounter difficulties when entering the housing market, irrespective of whether they reside in growing or shrinking cities. However, their prospects differ depending on the interplay between market forces and public housing interventions.

Second, we contend that even though housing policy is formally delegated to the local level in most European countries, the national housing framework still wields dominance by generating the majority of legal and financial incentives for the functioning of the owner-occupied and rental sectors. It leaves limited room for local authorities to mitigate the effects of economic growth (or shrinkage) through the public rental sector.

To substantiate these hypotheses, empirical testing is undertaken, and ideal types are created based on the combination of economic potentials and housing policies. These are illustrated through the analysis of four selected European urban areas that represent these ideal types: Amsterdam, Tallinn, Chemnitz, and Pécs.

This study heavily relies on the outcomes of the UPLIFT project,1 financed by the Horizon 2020 research program of the European Union. Throughout the project, in-depth city analyses were executed, drawing from desk research and interviews with experts, policy implementers, and vulnerable young individuals.

The existing body of literature provides a rich landscape exploring the relationship between housing policy and social inequalities. Concurrently, ongoing discussions scrutinize the interplay between urban social disparities and the economic positioning of cities (like Ranci et al., 2014). In this article, our objective is to establish the foundational framework for bridging these two dynamic discourses. Our aim is to construct a narrative that systematically elucidates the factors determining or diverging the connections between a city's economic standing and the emergence of social inequalities in housing, with local policy responses serving as mediators.

Our focus centers on housing inequalities concerning the younger generation, particularly those individuals embarking on their housing journey for the first time. Within the housing literature, inequality is predominantly gauged by housing affordability. However, the security of housing and the quality of housing, including its location and proximity to the labor market, also define households' housing outcomes. These concepts often intersect and overlap. Some elements of the literature consider housing insecurity as an overarching term encompassing both housing affordability and quality (Leopold et al., 2016). Additionally, quality criteria are recurrently integrated as indicators of affordability (OECD, 2021). Housing insecurity (Linton et al., 2021) is characterized as falling behind on rent or mortgage payments or harboring low confidence in meeting future rent or mortgage obligations.

The geographical location of housing and housing segregation are also pivotal indicators for assessing housing inequality. Termed “geographies of opportunity,” this concept underscores that the availability of diverse, affordable, and high-quality housing options varies across different spaces within a city. This variation frequently contributes to the perpetuation of disparities, influencing access to opportunities and accumulating intergenerational impacts on families and communities (Leopold et al., 2016).

Housing affordability remains an enduring challenge for young adults across numerous European cities, as evidenced by prior research (Forrest and Yip, 2012; Filandri and Bertolini, 2016; Lennartz et al., 2016). Housing costs are on the rise, whereas the economic circumstances of young individuals are marked by volatility, and their incomes fail to keep pace with the escalating rents and housing prices. Typically, housing affordability is assessed through metrics such as the ratio of housing prices to income and the proportion of housing expenditure to housing costs. This aids in comprehending household affordability and the extent of financial burden placed on households, sometimes measured as residual income after housing expenses are met.2 An analysis of the SILC data on housing affordability reveals that the younger age group, aged between 15 and 29, experiences significantly greater housing cost overburden compared to the working-age population.3

The expansion of commodification (the market-driven development of the housing sector) and financialization (the financing of housing through the financial sector), coupled with the challenges in accessing credit due to precarious employment conditions, has compounded the difficulties young people face in attaining homeownership (Arundel and Doling, 2017; Druta and Ronald, 2017). The accessibility of social housing has also become increasingly challenging due to welfare reductions and austerity measures implemented across Europe. Consequently, young people often find themselves compelled to rely on a very expensive and frequently poorly regulated private rental sector, which, in most cases, fails to meet the demand for affordable housing (Coulter et al., 2020).

Cities with prosperous economies are characterized by high-productivity jobs and workplace diversity. Sassen (2007) has observed that contemporary cities possess a dual nature: Certain segments of people and production are integrated into the global networks of the modern technological economy, while others are excluded. The heightened demand for well-paid workers exerts pressure on the housing market, leading to price growth, which ultimately displaces low-income workers from the city. This, in turn, involves nearby municipalities in addressing the housing market imbalance (Nijskens et al., 2019).

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the price-to-income ratio surged in major growing European cities (Hegedüs et al., 2017). The increasing investment in housing as an asset has driven up housing demand, resulting in a housing supply gap that compounds the challenges young people face in accessing housing (Aalbers, 2016). Furthermore, house prices in cities are influenced not only by local factors such as supply constraints, regulations, and zoning but also by global trends, including the growing role of foreign investors. This phenomenon is referred to as “glocalization.” House price fluctuations in capital cities tend to be more volatile and pronounced than in other parts of the country, necessitating more targeted measures at the local level (Nijskens et al., 2019).

Conversely, the proliferation of shrinking cities can be seen as a counterpoint to the increasing importance of agglomeration economies, which concentrate economic growth in a few select locations. While shrinkage is nearly universal, its specific determinants may vary from context to context (Haase et al., 2014). The literature has highlighted several overlapping causes, including demographic shifts (reflecting decreasing birth rates mirroring national trends), geopolitical shifts (especially political instability following the Soviet Union's collapse), and critically, economic restructuring and deindustrialization (Haase et al., 2014; Silverman, 2020). Like agglomeration economies in high-growth areas, the processes of urban decline create self-reinforcing cycles of underinvestment, capital flight, joblessness, and population loss (Fol, 2012). Housing plays a role in deepening inter-regional wealth disparities through increasingly uneven real estate values. Particularly in contexts where owner-occupation is the norm, this erects significant barriers to inter-regional mobility (Moretti, 2013). Additionally, research has emphasized regional disparities in the returns on education, contributing to differing levels of mobility based on educational attainment, as leading regions place a greater premium on skills (Moretti, 2013; Iammarino et al., 2019).

In shrinking cities, housing insecurity often arises from decreasing market demand due to population decline, leading to falling housing values. This can result in a surplus of permanently vacant housing stock, which may be of lower quality and contribute to a deteriorating urban environment. Glaeser and Gyourko (2005) have noted that when a population declines, house prices tend to decrease at a faster rate than they rise in response to population growth. This condition, where the value of housing assets depreciates more rapidly than they appreciate in growing cities, accelerates the rate of urban shrinkage. The disparities in housing vacancy rates across different areas contribute to differential declines in the value of housing assets, thereby fostering segregation in shrinking urban areas. Addressing these challenges often requires urban rehabilitation programs aimed at creating mixed neighborhoods and investments to facilitate labor market integration.

As previously emphasized, the economic strength of cities has a direct impact on the housing market's structure and the equilibrium between supply and demand. Conversely, the local housing regime possesses the capacity to influence and mitigate the direct effects of economic drivers.

Local housing regimes can be categorized in various ways. The most commonly used theory, though subject to ongoing debate, is developed by Jim Kemeny, who contextualized housing regimes within the framework of welfare regimes (originally defined by Esping-Andersen, 1989). Kemeny highlighted that the provision of housing has been an integral part of welfare services since World War II, and a country's general welfare regime shapes the nature of its housing policies, classifying them as social-democratic, liberal, or corporatist. In liberal welfare regimes, state intervention is minimal, with market forces largely determining the level of social security, after which the state makes modest redistributions. Conservative or conservative-corporatist welfare regimes, found in countries such as France, Italy, and Germany, provide relatively more generous benefits based on insurance contributions. Social-democratic regimes, as seen in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, involve significant state interventions, guaranteeing universal benefits at generous levels. Within the context of housing, Kemeny also explored the possible connection between forms of corporatism and the rental system. He differentiated between labor-led (e.g., Norway), capital-led (e.g., Germany), and power-balancing (e.g., Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands) cases among corporatist countries. This differentiation explains the variations among countries in the proportions of public and market rental housing providers. Capital-driven corporatism results in a smaller public rental housing market, while power-balancing cases are more evenly distributed between private (profit-oriented) and public (cost-driven) sectors (Kemeny, 1995).

Another commonly used distinction among various housing regimes is based on the role of market structures in the housing market. In cases where market mechanisms predominate, with factors such as mortgage loans, financial institutions, and supply-demand dynamics at the forefront, these are referred to as commodified regimes. Conversely, de-commodified regimes are characterized by the dominance of public approaches. It is important to note that commodification cannot be solely described by tenure structures as access to ownership may also be influenced by public incentives, as observed in countries like Ireland or Norway (Dewilde and De Decker, 2016). Hoekstra (2020, p. 35) defines de-commodification as “the extent to which households can provide their own housing, independent of the income they acquire on the labor market,” highlighting the nature of de-commodified housing regimes aimed at reducing social inequalities in the housing market.

Hoekstra (2020) argues that a city or region's housing system is shaped by the specific local configuration of competencies, tasks, and resources of different actors. The local housing regime establishes a framework in which the distribution of competencies among actors plays a crucial role in understanding the mechanisms behind housing inequality indicators. According to Hoekstra's proposition, urban inequalities are not solely explained by economic power or national welfare systems but also encompass the dimension of power distribution among actors.

The effectiveness of local housing interventions in mitigating the impacts of economic and labor market structures can vary. The most commonly used tool for reducing housing inequalities and providing housing access, including for the younger generation, at the local level is the public rental sector. Kemeny (1981) provides an explanation of the rental structure of the entire housing system by distinguishing between dualist and unitarist (and later integrated) systems through an analysis of the rental sector. In a dualist system, the private for-profit rental market takes precedence, and public interventions are separated, focusing on providing a safety net for those most in need. In a unitary rental system, the public rental sector encompasses a significant portion of the housing stock, accommodating a range of social classes and influencing the profitability of the market rental sector simultaneously.

Some scholars argue that, especially in growing cities, achieving housing affordability can only be realized through robust supply-side measures (Hsieh and Moretti, 2019). Effective tools for addressing this issue include interventions through building regulations, which can modify the intensity of development in urban zoning and land use policies (e.g., stipulating high-rise buildings). Social rented housing, regulation of new building stocks (e.g., 40-40-20 policy in Amsterdam), or the retention of land use rights (e.g., Berlin's 99-year lease) can also be part of the urban property policy toolkit. These measures help create a housing market that maintains diversity in pricing (Rodríguez-Pose and Storper, 2020).

Conversely, in regions with low housing demand coupled with a robust housing welfare regime, access to housing can be favorable. According to Haase and Wolff (2022), in Eastern German shrinking cities, young people experience comparatively good access to affordable housing due to population loss and shrinkage on the demand side, along with strong housing welfare schemes including national and federal regulations on rents and available rent subsidies. However, the challenges include high vacancy rates in the local housing market, including social and affordable housing opportunities, due to population shrinkage. Addressing this requires continuous resources and attention to improve the quality of the local housing stock. Targeted measures to support property acquisition and preferential credit facilities can alleviate the demand shortage, a common issue in shrinking cities. Segregation, which often occurs due to spatial variations in housing vacancy rates, can be addressed through urban rehabilitation programs aimed at creating mixed neighborhoods and income support to enable labor market integration.

Access to housing for the younger generation is a critical issue, both in economically strong cities and in those experiencing economic stagnation. A central concern revolves around the relationship between housing prices/rents and incomes. In economically stronger urban areas, housing costs tend to be higher, but incomes are also elevated. However, the distribution of these incomes becomes a crucial factor, as does the adaptability of the local housing regime to address income disparities. In shrinking cities, the demand for housing is lower, and the labor market offers limited income opportunities, making access to housing for the younger generation contingent on the structure of the local housing market and the underlying housing policy framework.

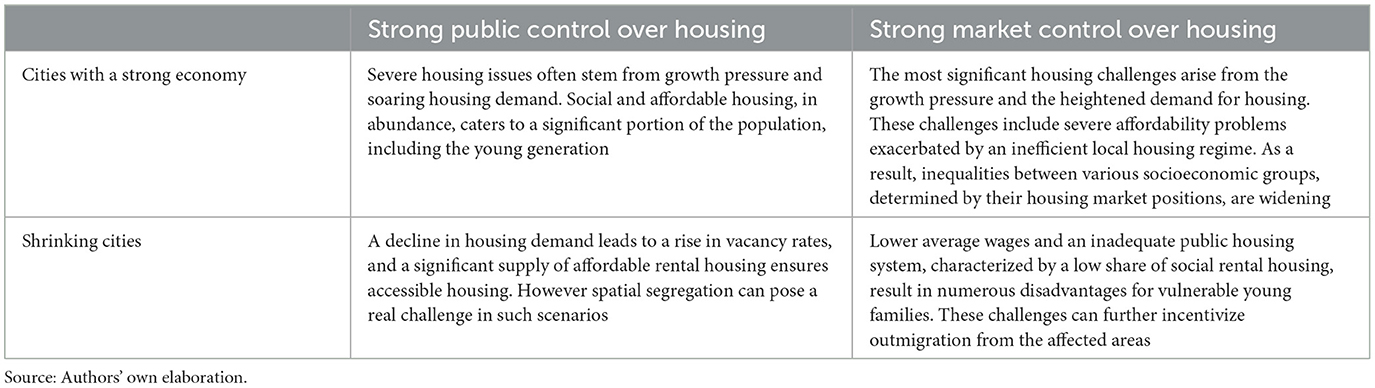

By shedding light on the potential effects of a city's economic condition on housing accessibility for the younger generation and emphasizing that housing policies can be categorized based on their rental structure and degree of commodification, we can define ideal types of European urban areas. Table 1 outlining these ideal types, which represent a combination of economic dynamics and housing interventions.

Table 1. Ideal types of European urban areas with a combination of economic dynamics and housing interventions.

The scientific literature examining the housing consequences of a city's economic condition has enabled us to categorize European cities into four major ideal types. This article's objective is to demonstrate how these ideal types manifest at the local level and to explore any potential deviations from the patterns established in the literature. Through this approach, we aim to identify and analyze the mechanisms by which the economic status of urban areas is translated into housing inequalities among young people, primarily influenced by the local housing welfare regime. Our core hypothesis is that young individuals encounter challenges when entering the housing market in European urban areas, regardless of the city's economic backdrop. However, the level of difficulty and the specific sectors and urban areas they can access depend significantly on the ideal type associated with the location.

An additional hypothesis worth considering is that despite economic processes operating at the local (agglomerational) level and the implementation of various housing policy tools happen on the local level, the capacity of local actors to respond to local economic challenges remains limited. This is because housing policy is heavily influenced at the national/regional level, as well as by determinants stemming from historical behaviors and structural factors.

To explore these hypotheses, we have adopted a strategy focused on four distinct cases, each representing one of the four ideal types previously defined. Drawing from Flyvbjerg's (2006) work, we recognize that carefully chosen cases offer substantial potential for gaining context-specific, in-depth insights, hypothesis formulation, validation, and even generalization. Unlike the analysis of large samples, which tends to identify symptoms, case studies allow us to elucidate the underlying causes behind these symptoms. Since the typology was established through a literature review, the role of these case studies is to exemplify how these mechanisms operate at the local level and enhance the typology by providing specific details and refinements to the model.

For this purpose, we have selected four European areas, each representing one of the four categories mentioned earlier: (1) an economically strong city with robust public control over the housing market (Amsterdam, Netherlands), (2) an economically strong city with a neoliberal, market-driven housing regime (Tallinn, Estonia), (3) a shrinking city with robust control over the housing market (Chemnitz, Germany), and (4) a shrinking city with a predominantly market-based housing system (Pécs, Hungary).

These four cities were chosen from a pool of 16 potential urban areas analyzed extensively during the UPLIFT project. The initial selection aimed to encompass diverse geographical locations, economic strengths, and varying degrees of compensatory power within welfare policies. Economic potential was measured using GDP per capita and/or population dynamics (when GDP data at the urban level were unavailable). The compensatory power of the welfare system was evaluated through changes in national income Gini coefficients before and after social transfers. These two main attributes were used to create a matrix, leading to the final selection of these 16 urban areas.4

During the UPLIFT project, a substantial amount of data was collected for the 16 urban locations, leading to a more refined classification. This classification distinguished between strong market cities, weak market cities, and linked cities that functioned as satellites within larger metropolitan areas.5 Additionally, an initial evaluation matrix was developed to assess the performance of local welfare systems in the domains of housing, education, and employment. The data used in the Results section for the four selected cases primarily originate from the Urban Reports and Case Study Reports6 developed on these urban areas in the UPLIFT project. In cases where additional data sources were utilized, clear citations are provided. Generally, the Urban Reports offer a comprehensive overview of the economic and demographic conditions in each urban location, as well as the functioning of national and local welfare systems in areas such as education, employment, housing, health, and social provisions. The information for the Urban Reports was primarily gathered through desk research, supplemented by expert interviews.7 Furthermore, Case Study Reports were conducted in eight of these 16 locations, providing an even deeper understanding through interviews conducted by local UPLIFT research groups. These interviews involved policy implementers in the domains of education, employment, and housing,8 as well as 20 vulnerable young individuals aged 15–29. Additionally, interviews were conducted with 20 individuals who were vulnerable and aged 15–29 during the Great Financial Crisis (now aged 30–43 at the time of the interviews). The analysis in the Case Study Reports applied the capability approach9 to identify the mechanisms trapping young people in a cycle of vulnerability in housing, employment, and education. The four locations (Amsterdam, Tallinn, Chemnitz, and Pécs) were selected from these eight urban areas, allowing the analysis to benefit from both the Urban Reports and Case Study Reports.

The research primarily focuses on analyzing these four case studies while seeking synergies and differences among them. To illuminate the transition from economic potential to housing inequalities among young people, a comprehensive analytical approach is followed in each of the four case studies. This structured methodology enables a thorough exploration of the factors contributing to housing inequalities among the young population in these selected urban areas.

• The initial step involves briefly summarizing the economic characteristics of the urban area, focusing on aspects significantly impacting housing demand. This encompasses the quantity of demand, including population size and other apartment user categories, as well as the quality of demand, specifically wage distribution among residents.

• Next, we describe the primary structural impact of economic potential on the housing market by examining key factors such as housing prices, rental levels, housing quality, and their influence on housing spatial distribution. These factors are pivotal for comprehending housing market dynamics.

• The subsequent stage involves a comprehensive evaluation of the local housing welfare system. Particular emphasis is placed on elements such as the presence and function of social housing, regulations governing the private rental market, the availability and impact of allowances, and the scope for local political actors to effect changes. These components collectively shape the local housing environment.

• In combination with the evaluation of the housing welfare provision, an assessment is made of how the combined effects of structural and welfare factors influence housing inequality outcomes, encompassing the affordability and accessibility of housing for the young generation. Through an analysis of the interplay between economic factors, housing market dynamics, and welfare policies, the research seeks to uncover the mechanisms underpinning the production and perpetuation of housing inequalities.

The presentation of the mechanisms linking economic and housing structures has inherent limitations, primarily stemming from the intricate nature of the subject matter and the dearth of comparable datasets. Both economic potential and the housing market can be approached from diverse perspectives, exceeding the boundaries of this article. Moreover, constraints exist in obtaining commensurate economic and housing datasets, given that data supporting these indicators are frequently lacking at the urban level. Even when such data are available, variations in interpretation and measurement methods may pose challenges, such as in the case of tenure structures, rent levels, and housing prices. As previously noted, this article heavily relies on the Urban Reports and Case Study Reports developed within the framework of the UPLIFT project. While this offers valuable insights, it also introduces limitations. These documents are bound by length restrictions and cover various domains of welfare, potentially restricting the depth of housing-related analysis. However, their methodology, which incorporates a comprehensive review of local literature and interviews with policymakers, implementers, and vulnerable young individuals, serves to focus the research on the most pertinent housing needs and contradictions in housing service provision, as highlighted by interviewees.

The theoretical background has offered valuable insights into the nature of housing inequalities within both expanding and contracting urban environments. These insights have laid the foundation for the identification of four primary ideal types of urban areas. The objective now is to provide a comprehensive illustration and evaluation of these ideal types through the four case studies.

Amsterdam, representing this particular ideal type, is currently grappling with an enormous housing challenge, particularly concerning its younger population. The city is renowned for its robust regional and local economy, resulting in substantial population growth and an escalating demand for housing solutions. Even during the financial crisis of 2008, the Amsterdam metropolitan area managed to maintain a GDP growth rate and followed an increase of 4% annually since 2014, thanks in large part to its diversified economy. The rapidly expanding tech sector plays a pivotal role in driving high employment levels in Amsterdam. This growth is facilitated by the favorable ecosystem within the Amsterdam city region, which supports the development, attraction, and retention of tech scale-up companies. Additionally, Amsterdam benefits from a rich pool of experienced tech professionals and is deeply embedded in a dense network of entrepreneurs, events, investors, and incubators, making it an ideal breeding ground for new startups. It is important to note that while tech salaries in Amsterdam may be lower compared to A-class tech hubs such as London or Silicon Valley, the overall quality of life is superior. However, newly recruited talent often grapples with the challenge of finding affordable housing due to the emerging housing shortage (van Winden et al., 2020). Despite these challenges, Amsterdam still secures a commendable 11th place in the Global Cities Talent Competitive Index ranking (INSEAD, 2022).

The population growth in Amsterdam is striking; in 2007, there were 742,884 inhabitants, which surged to 862,964 in 2019 and reached a staggering 921,468 in 2023. In addition to the regular population growth, Amsterdam serves as a hub for universities, offering English language courses to both international students and native Dutch. However, the universities' strategy of admitting an increasing number of foreign students places significant pressure on the city's student accommodation system.

The demand pressure stemming from population growth is compounded by the dynamics of financialization and commodification in the Dutch housing market. These factors have led to a consistent and substantial rise in housing prices. For instance, in 2021, housing prices were expected to increase by 10.9% compared to the previous year. Notably, in Amsterdam, the average selling price was 56% higher than the national average in 2018. These economic trends have significantly exacerbated the housing exclusion experienced by young people, especially 'starters' (individuals aged between 18 and 29) seeking opportunities to independently enter the housing market. Accessibility and affordability have dwindled over the years, driven not only by the worsening housing situation but also by labor market precarity. Another formidable challenge for those entering the local housing market is the competition with individuals looking to move up the housing ladder and with institutional and private investors. The latter group has increasingly focused on buy-to-let schemes, accounting for more than 20% of all flat purchases in 2019. Despite new construction and housing market developments, fewer people can afford homeownership, as evident in the declining ratio of owner-occupied flats, which dropped from 32.5% to 30.8% between 2017 and 2019.

Amsterdam boasts a vibrant international character, with a notably diverse population. While the rate of people with foreign-born parents in the Netherlands stands at 23%, it surges to 54% within the city of Amsterdam. A significant portion of this population, accounting for 66% of individuals with a migration background in Amsterdam, hails from non-Western countries, primarily Morocco, Suriname, and Turkey. This diversity profoundly influences both the local housing market's structure and housing policy. Despite the Netherlands' robust social and housing policies, Amsterdam's rapid growth has spurred increased segregation. Housing market developments tend to occur on a spatial basis, contributing to the suburbanization of poverty. Consequently, central parts of Amsterdam are primarily inhabited by highly educated individuals with higher incomes, while households with fewer resources and skills are pushed to the periphery. This exacerbates inequality as the central areas offer better job market access, while entering the job market in Amsterdam is costlier for those commuting from the periphery (Boterman et al., 2021).

Regarding the rental sector, there exists a national rent regulation system based on a strict point system that considers factors such as dwelling size, quality, and value. This system applies to properties owned by both private landlords and housing associations. Beyond a certain point threshold, rental dwellings are offered on the open market without restrictions. In expensive areas such as Amsterdam, where more flats are falling out of rent restrictions, this further diminishes affordable housing opportunities.

Conversely, there is a relatively large social rental sector in Amsterdam's functional urban area, constituting 41% of the entire housing stock. In theory, this sector should provide accessible and affordable housing solutions for young people. However, several factors hinder this sector from addressing the significant housing crisis in Amsterdam, particularly among the youth. First, the social rental sector is shrinking while the demand for affordable housing is growing. Second, a strict maximum income requirement, set at the national level to comply with EU regulations, excludes middle-class individuals from accessing social rental housing. Third, the substantial demand for municipal housing has resulted in extensive waiting times, averaging 16 years. A new reform addressing social housing is under review for 2023 to address the long waiting lists and housing needs. However, as the point system is determined by the national government in relation to house value, it practically means that most rental units will eventually shift to the free-market sector over time.

In Amsterdam, housing subsidies are exclusively available to those who rent a rent-regulated dwelling, creating a significant challenge for individuals unable to access social housing or a rent-regulated unit due to nationally defined income thresholds.

Another pressing issue, reported not only by local experts but also by vulnerable young people, is the temporality of supported housing. Temporary rental contracts were introduced by the government in 2016 with the intent of providing support until households improved their economic circumstances, enabling them to transition to the liberal, market-based housing sector. However, instead of operating smoothly as intended, this temporality has heightened insecurity regarding affordable housing solutions due to increased demand in the housing market.

One's housing situation is not solely contingent on the nature of the housing market and the opportunities it presents but also on the information available and the individual's social network. Based on interviews with young people aged 15–29 in vulnerable life situations and interviews with individuals aged 30–43 who faced vulnerability during the financial crisis, the challenges related to housing have far-reaching effects on various aspects of young people's lives. The intense competition for affordable housing makes informal networks and information-sharing crucial assets. Additionally, the insecurity caused by the time limitations of rental contracts motivates some young people to prolong their studies as they have more stability while pursuing education. This decision is often driven by the fear of finding another affordable housing solution, the financial burden of moving, and the stress associated with housing instability. These factors collectively contribute to mental health issues among young people and limit their agency in making life decisions as they prioritize affordable housing situations. This can result in individuals being trapped in unhealthy relationships, spending an excessive portion of their income on housing, and struggling to cover basic living expenses or move out of Amsterdam, potentially sacrificing access to job opportunities.

These trends have led to increasing housing challenges, affecting not only the most vulnerable groups such as migrants and refugees but also local individuals with higher education and middle incomes, especially when intergenerational transfers of wealth are unavailable. Consequently, family attitudes and wealth have become increasingly significant factors in determining young people's housing prospects in Amsterdam.

To address these challenges, the local municipality has implemented several tools. For instance, the municipality regulates new developments using the 40-40-20 rule, allocating 40% for social rent, 40% for affordable private rent or affordable homeownership, and 20% for full market-priced housing. Additionally, there is a student and youth housing plan aimed at supporting students and newcomers to the housing market.

The case of Amsterdam highlights the following key points:

• A flourishing economy, incoming investors, and a growing workforce collectively generate substantial housing demand. However, housing welfare provisions struggle to keep pace, resulting in escalating housing prices and rents. This situation adversely affects young individuals starting their housing and professional journeys.

• The rental system in Amsterdam is transitioning from a unitary structure, serving the middle class, to a dual system that primarily caters to the most economically disadvantaged. This shift is not solely driven by economic pressures but is also influenced by EU requirements implemented through national legislation.

• Amsterdam, as a thriving and expanding city, faces significant housing pressure. Unfortunately, national housing policies are not adequately tailored to address the housing challenges experienced at the local level. For example, the rent cap point system lacks sensitivity to the income levels within the city compared to the national average. Consequently, many individuals are excluded from receiving support. This disconnect between housing interventions and the needs of Amsterdam's residents has led to housing insecurity due to the temporary nature of affordable housing solutions and difficulty in accessing affordable housing, primarily due to a relative shortage of social housing and nationally set income thresholds. Despite state interventions aimed at mitigating local housing issues, the housing crisis appears to be escalating.

This case is exemplified by Tallinn, the capital of Estonia. The functional urban area of Tallinn encompasses Harju County, with a total population of 605,000 residents (437,615 in the city of Tallinn as of 2020), encompassing nearly half of the country's population. Despite the country experiencing population decline, Tallinn is experiencing substantial growth, with a 10% increase in 13 years. This growth is driven by significant economic power as Tallinn is the fastest-growing region in Estonia, contributing to ~65% of the country's GDP in 2019, employing 52% of the labor force, and having a GDP per capita 43% higher than the national average. The service sector, accounting for 80% of the GDP in the Tallinn region (compared to 72% nationwide in 2019), is the primary source of growth.

Tallinn has been actively striving to position itself as a smart city and has demonstrated notable success in various statistical indices. For instance, it ranks 18th out of 60 cities in the European Digital City Index (Sarv and Soe, 2021). Estonia boasts the highest concentration of knowledge-intensive jobs among Eastern and Central European countries in proportion to its working-age population. However, due to its relatively small size, Tallinn may not reap the same scale of benefits as larger urban centers, yet it has managed to achieve international recognition despite its size (Sanandaji, 2021). In terms of the Global Cities Talent Competitiveness Index, Tallinn is positioned at 78th place with a score of 45.8. This ranking is approximately 20 points lower than Amsterdam's score (INSEAD, 2022).

Young people in Tallinn are predominantly employed in sectors such as wholesale, retail trade, transport, accommodation, food services, manufacturing, scientific and educational activities, as well as information and communications. Tallinn is recognized as one of the most technology-oriented cities, demanding a highly qualified (and highly paid) workforce. However, this requirement has created a gap between those who can meet the demands of the digital age and those who cannot. The most vulnerable groups in Tallinn's labor market include the undereducated, “Russian speakers,” and people with disabilities.

According to Eurostat data, Estonia witnessed the fastest increase in housing prices and rents in the EU between 2010 and 2020, particularly in Tallinn and Tartu. While this increase was partially attributed to GDP and income growth, prices escalated more rapidly than incomes, resulting in worsened affordability. Consequently, overcrowding rates in the Tallinn functional urban area are high, with approximately twice as many inhabitants per flat compared to Western European countries.

Tallinn's population is highly diverse, comprising 52% native Estonians, 38% Russians, and 10% from other nationalities (as of 2018). The category of “Russian speakers” mainly includes those who migrated during the Soviet era. This demographic division has significant spatial consequences as housing stock in the Tallinn functional urban area exhibits high levels of segregation. Russian-speaking inhabitants tend to reside in large housing estates constructed during the Soviet era and in industrial towns within the functional urban area. In contrast, ethnic Estonians live in a more dispersed manner, from suburban family homes to multi-apartment buildings in the downtown areas. Suburbanization around Tallinn is a robust process that exacerbates spatial segregation as moving to newly developed suburban areas is often associated with higher incomes, primarily among ethnic Estonians.

Similar to other former Soviet countries, privatization of state-owned housing stock was offered to sitting tenants, accompanied by restitution of predominantly downtown buildings. This expansion in housing ownership did not follow a path of “commodification” through financial markets but rather resulted from a public intervention that made housing ownership accessible to low-income individuals. Presently, the owner-occupied sector accounts for 75% of housing, private rental for ~23%, and municipally owned housing for ~2% of Tallinn's housing stock as of 2020. The municipally owned sector includes ~4,000 units, of which ~3,200 are habitable, leaving residents largely reliant on the private market, either as homeowners or tenants. The use of social rental units is governed by national regulations, primarily targeting low-income families, orphans, disabled individuals, or those with special needs. The limited share of the social rental sector results from conflicting processes: the gradual sale of existing municipal stock and the construction of new social housing complexes, consisting of 5–15 story buildings, which added nearly 3,000 new units between 2002 and 2010. These new social complexes were built in already segregated housing estates on the outskirts of Tallinn, exacerbating spatial segregation. Young interviewees in Tallinn have expressed concerns about the concentration of social issues, such as addiction or violence, within these social housing complexes.

While privatization offered an opportunity for low-income individuals to attain housing ownership, it has become significantly more challenging over the past decade. With an overwhelmingly high ownership rate, inequalities are most pronounced in terms of access to accumulated wealth (family background) and the ability to make down payments and meet income requirements for loans. Notably, before the Ukrainian war, mortgage interest rates were relatively low, but strict loan-to-income ratios imposed stringent obligations.

Given the formidable barriers to homeownership for young people, private renting has become a more viable option. However, regulations governing tenancy in Estonia are relatively weak. The vast majority of the private rental market operates informally, leading to insecurity for both landlords and tenants, volatile rents, and unregulated eviction processes. This situation is particularly concerning for young people, as more than twice as many individuals aged 20–29 live in the private rental sector than in other age groups. Furthermore, the share of the private rental sector inhabited by young people has significantly increased over the last decade, exacerbating overall housing market insecurity for the young population.

In Estonia, social allowances include housing allowances, without additional supporting structures. In the Tallinn functional urban area, only 0.8% of the population received social allowances in 2018, with 1% among young people aged 15–29. These figures underscore the limited relevance of this benefit in enhancing housing affordability across all tenure types.

Estonia's constitution delegates housing matters to the local level, primarily covering social housing. The largest housing program, Kredex, is centrally organized and funded. Kredex encompasses various interventions, including providing funds (up to 20%−25%) to local municipalities for social housing construction, offering guarantees for young people to secure mortgages and access homeownership (including tax reliefs), granting housing allowances for those falling below the subsistence line after housing costs, and financing the energy modernization of multi-apartment and single-family residential buildings.

While it might seem that local municipalities lack the financial means to address the housing crisis, in reality, nearly 70% of the city's revenues come from taxes,10 primarily personal income tax and partially land tax, closely tied to its economic performance. The Tallinn case is more indicative of a lack of political will or reliance on state co-financing. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that ongoing debates are taking place at both the national and local levels regarding strategies to alleviate the housing crisis in Tallinn.

The case of Tallinn highlights the following key points:

• The metropolitan area's economic potential and financialization have led to significant immigration pressure, resulting in Tallinn experiencing the highest growth in real estate prices in Europe between 2010 and 2020. This growth has also contributed to extremely high overcrowding rates in the city.

• Tallinn's housing market is characterized by a residual public housing system, which, combined with the overall housing pressure, pushes young people toward the insecure private rental sector or encourages them to remain with their families due to limited affordable housing options.

• While housing provision is theoretically a local competence, in practice, major housing legislations are established and funds allocated at the national level. There is also a strong path-dependency in local housing practices, shaped by historical processes like privatization. Despite Tallinn municipality generating a significant portion of its income from its own inhabitants (taxpayers) and experiencing economic and income growth among its residents, it would require political consideration to be more sensitive to the housing needs of vulnerable young people.

The category is represented by Chemnitz, which is the third-largest city in Saxony, Germany, with ~240,000 inhabitants. Chemnitz has historically been a significant industrial hub, holding a prominent role as the major industrial production site in the German Democratic Republic (GDR). However, following a prolonged period of deindustrialization and population decline, the city experienced stagnation. In recent years, it has seen slow growth, and local policymakers have rekindled the city's industrial transition. They have worked to establish Chemnitz as a “modern city.” This try for an economic revival can be attributed to both the agglomeration benefits of being part of a larger urban area and the strategic utilization of local industrial assets. Additionally, Chemnitz benefits from a strong entrepreneurial culture that has persisted from the pre-socialist era (Rosenfeld and Heider, 2023).

Chemnitz is situated in the southeastern part of the Metropolitan Region of Central Germany, near Leipzig and Dresden. In comparison with these cities, Chemnitz is considered peripheral due to its secondary transportation connections and its predominant role as an economic workbench, lacking significant corporate headquarters. While Chemnitz remains the center of its regional planning system, surrounding cities have larger populations and higher gross domestic product (GDP). In 2020, Chemnitz's GDP was 9 billion euros, constituting 7% of Saxony's GDP. The sectoral composition of Chemnitz's economy mirrors that of a modern Western city: 0.1% in agriculture and forestry, 18.5% in manufacturing (excluding construction), and 7.6% in construction. The remaining 73.8% are in the services sector (2019 data),11 with notable growth attributed to increased automation and digitalization, which provide limited benefits for vulnerable young people. Despite a generally robust labor market in Chemnitz, finding employment remains challenging. However, small companies specializing in low-skilled workers play a role in assisting young people in entering the labor market.

Chemnitz is thus a peripheralized shrinking/stagnating city. Between 1990 and 2010, the city lost nearly a quarter of its residents, primarily due to natural population decline and migration to western parts of the country, despite several villages merging into the city. Since 2010, the population has essentially stagnated. Demographic shifts are evident in an aging population, low regional birth rates, and emigration to economically more favorable western cities, driven by deindustrialization and high unemployment rates. The proportion of young people has continually decreased, standing at ~10% in 2020, equal to the share of the population with a migration background.

Due to the past population decline and current stagnation, there is limited demand pressure on the housing market, resulting in relatively high vacancy rates compared to similar cities. Market observations12 from 2020 indicated a vacancy rate of 8.5% in Chemnitz, significantly higher than the rates observed in the newly revitalized former shrinking cities of Dresden (1.8%) and Leipzig (3.5%).

In Chemnitz, the high proportion of welfare beneficiaries, unemployed individuals, single-parent families, and high population density coincides with the high rate of residents with non-German backgrounds in the inner parts of the city. While these factors, in isolation, may not inherently constitute social problems, their socio-spatial overlap serves as an indicator of “areas in need of policy attention” and forms the basis for urban development planning measures. Since 1999, the city has implemented social rehabilitation programs (known as “Sociale Stadt”), indicating a broad awareness of social-spatial issues.

The ownership landscape of the housing market in Chemnitz is highly diverse: 51.7% is privately owned, 19.7% by housing cooperatives, 18.7% by municipal housing companies, with the remaining 11.1% owned by various public and private entities. Notably, a substantial portion of the housing stock is under municipal ownership, which provides ample social housing options for the most vulnerable young individuals. Less vulnerable young people can also find affordable housing in other segments of the housing market, thanks to state regulations on rent and income-dependent rent subsidies.

Housing in Chemnitz is readily accessible and affordable, even for young people looking to establish independent housing arrangements between the ages of 18 and 22.

National rent regulations, known as the Comparative Rent Law (Vergleichsmieten und Mietendeckel in the civil code), ensure that rents remain affordable at the local level. Housing rent subsidies are available for both lower- and medium-income households, as well as those at risk of poverty based on the Welfare Code. Additionally, the city offers excellent accessibility to information services, both in-person and via phone, which exceeds the digitalization-related gaps seen in other German cities. Moving within the municipal housing sector is relatively straightforward, not only making housing affordable but also secure. Special assistance is provided to young people aged 17 and over to prevent homelessness. In fact, none of the 40 interviewees in the Case Study Report of Chemnitz reported significant housing problems, illustrating the favorable situation of residents compared to other European cities.

Following the GDR period, Saxony's federal state housing policy focused on refurbishment, leading to substantial support for Chemnitz in the form of tax exemptions on investments in rental properties. The introduction of income and access controls, along with public support for rehabilitation, created opportunities for “quasi-social housing.” Specific programs were initiated to support elderly private landlords and youth, fostering collaborations between private and public housing companies and youth welfare providers and activists. These initiatives enhanced the inclusion of vulnerable young and elderly individuals.

Nonetheless, there are unique local mechanisms in Chemnitz, compared to other places, which may contribute to young people leaving the city despite its accessibility and affordability in terms of housing. These mechanisms include the promotion of right-wing narratives, which reinforce perceptions of segregation. Interviewed young people have reported a perceived segregation in housing, despite efforts to counter anti-racist narratives. Simultaneously, an influx of migrants and asylum seekers to the city has increased investments but also exerted some pressure on local property owners to invest in housing. However, due to state rent regulations limiting return on investment, interventions typically require state subsidies. In marginalized segments, owners of run-down, often unrentable properties gain income without providing quality housing, contributing to a cycle of deteriorating housing quality and perpetuating issues for problematic renters. This phenomenon is locally referred to as “junk-real estate” and remains a challenge for local housing and welfare providers.

The case of Chemnitz highlights the following key points:

• In summary, this case represents a housing market characterized by low demand pressure. While this situation has led to public concerns regarding vacancies and declining housing quality, it has had a positive impact on vulnerable young people. They enjoy a high level of housing affordability and security in this context.

• The favorable housing conditions for vulnerable young people in this context can be attributed to various state, regional, and local controls. These include rent regulations and the availability of subsidies and allowances.

• Furthermore, the city leverages its existing housing wealth, including the extensive construction during the GDR era and subsequent waves of federal and state renovation programs in the 1990s (such as Städtebauförderung and Stadtumbau), which significantly enhanced housing quality.

Pécs, located in the southwestern part of Hungary near the Croatian border, is a town with a population of 140,000. The city has experienced a constant population decline of −7.4% over the past decade. This decline can be attributed to Pécs being a post-industrial city that has struggled to restructure its economy in recent years. The public sector plays a significant role in Pécs, accounting for approximately half of all employment positions, with the University of Pécs being the largest employer. The university's presence has a substantial impact on the city's economy, influencing urban development and increasing local consumption. It is estimated that 20% of the local GDP is generated from the spending of foreign students, with every four foreign students creating one job in the city (Gál, 2020).

The distribution of economic sectors has undergone significant changes since the collapse of the socialist industry. Currently, the service sector dominates, representing 82.87% of all enterprises. In contrast, the previously prominent industry and agriculture sectors now account for only 10% and 7.58% of total enterprises, respectively. Pécs is home to only a small number of large companies, primarily in foreign-owned processing industries. Among the 500 largest Hungarian companies, only three are located in Baranya county, where Pécs is situated (see text footnote 13). The city's heavy reliance on the public sector and the absence of major corporations result in slightly lower average wages, a higher proportion of low-paid workers compared to other large Hungarian cities, and a continuous outward migration trend.

Based on our preliminary typology, one would expect a high vacancy rate in a shrinking city due to declining demand caused by outmigration and moderate incomes. However, despite Pécs not being considered economically prosperous and experiencing population decline, its local housing market faces notable pressure. This is primarily attributed to Pécs being a university city with ~20,000 students13 and a significant draw for tourism, leading to relatively high property prices and rents (the private rent level is approximately twice that of larger cities in the same region, and the price per square meter of dwellings is roughly 25% higher). The vacancy rate is around 10%,14 which is comparable to that of larger Hungarian cities.15 Therefore, despite its population decline, Pécs experiences more significant housing market pressure than its overall economic performance would suggest, owing to its unique economic structure.

According to the Local Equal Opportunity Plan, eleven neighborhoods in Pécs are identified as either already segregated or at risk of social segregation. These identifications are based on indicators from the 2011 Census and follow a nationally established calculation method. Most of these neighborhoods are situated in the Keleti Városrész (Eastern Pécs), which was a former residential area for miners before the regime's collapse. This core segregated area houses between 1,500 and 2,000 residents, and some surrounding neighborhoods also exhibit low socio-economic status. Four out of these 11 neighborhoods have been subject to comprehensive rehabilitation interventions, primarily funded by EU funds since 2012 (Pécs ITS, 2014). Segregation is determined based on a complex set of indicators such as low educational attainment and unemployment rates, rather than ethnic characteristics. Nevertheless, it is evident that these areas exhibit a concentration of the Roma population.16 According to interviews conducted with experts and young residents, the segregation process appears to be impacting also Pécs' largest housing estates over the past decade, leading to an increase in residential conflicts. This trend underscores the correlation between declining permanent residents, low-income levels, and the growing risk of spatial segregation in Pécs.

In Hungary, the predominant form of housing is private ownership, accounting for 85% of housing in Pécs according to the 2011 census. However, for vulnerable young people leaving their families to establish independent lives, accessing private property poses significant challenges. This includes the requirement of a minimum 20% down payment and the need for a sufficient income to qualify for bank loans. Mortgage loan conditions, including steeply rising interest rates, have also worsened in recent years, while property prices in Pécs have tripled since 2018.

Despite the high barriers to entry into the private property market, local subsidies for renting are rarely available in Hungary, Pécs included. The housing allowance system is decentralized at the local level but remains practically insignificant due to stringent eligibility thresholds and low subsidy amounts per household. Although there were substantial state subsidies for purchasing property, especially for new builds, these subsidies are often unavailable to young individuals or couples without children who lack sufficient income or strong family support. This situation results in a perverse redistribution as national housing subsidies do not introduce enough new housing into the market to alleviate demand pressures. Furthermore, decisions regarding university funding and dormitories are made at the national level, with limited local influence over the student housing market, which significantly impacts the city's housing dynamics.

Pécs has a protected sector in the housing market with municipal units, but after compulsory privatization in 1994, the public housing sector became marginal, constituting only 5.5% of the total housing stock in Pécs (around 3,900 units in 2022, ~10% of which are vacant due to deteriorated physical conditions). Only half of these units are allocated at social rent levels, and there is a moderate difference between the social and other two municipal categories, such as “cost-covering” or “market-based” rent levels, as all remain well below actual market rent rates. The municipal rental sector is characterized by contradictions, including about one-third of tenants lacking official contracts due to overdue debts, subletting of units, and a concentration of long-term residents or those married to residents. New entries into the sector are relatively low, and the eligibility threshold for social units is quite low, ~two times the minimum pension per head, or ~150 euros. Other flats are distributed to individuals with limited incomes who offer lump sums for unit renovations. Most of the municipal rental units are located in socially segregated neighborhoods where the Roma population exceeds the city average. Although several urban rehabilitation programs have been implemented in these areas since 2007, they have been insufficient in addressing the scale of the issue.

The local public rental policy in Pécs is subject to ongoing debate. While there is a clear need for renovating dwellings and expanding the sector, local municipalities in Hungary face resource shortages. In the past decade, they have also lost competencies and funds due to a general centralization process. The COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukrainian war have provided additional reasons for the national government to impose new “solidarity” taxes on local municipalities. Business tax serves as a primary source of financing for local municipalities, and it was also centrally reduced during the pandemic. Economically stronger cities have more opportunities to pursue their own political preferences, which is less feasible in Pécs, where there is a substantial amount of business tax revenue but not as much as economically stronger localities. In light of these circumstances, the local political approach to public housing in Pécs aims to open the sector to middle-income, stable rent-paying residents.

Given the limited share of the public rental sector, entering the private rental market becomes one of the potential solutions. However, it is crucial to note that the private rental sector in Pécs is highly unregulated, with many contracts being illegal to avoid tax payments. Research in Pécs, based on 40 interviews with vulnerable individuals, has demonstrated that private landlords tend to employ discriminatory practices, often excluding families with children or Roma individuals from entering the private rental sector. Consequently, under these conditions, most vulnerable young people either reside in deteriorated public rental units (if they were born or married there) or choose to stay with their families or friends, refraining from moving into independent housing arrangements.

The case of Pécs highlights the following key points:

• The significance of temporary accommodations, particularly those associated with education and tourism, has contributed to rising housing prices and rents in Pécs. This phenomenon persists despite the city's overall low economic performance and a declining population.

• The outcome of the limited presence of the public sector, accounting for only 5.5% of the housing stock, is characterized by underfunding and a lack of transparency in its operation. This situation, combined with the negligible housing allowance and debt management programs, has led to the residualization and the physical as well as social marginalization of the public rental housing stock.

• The result of the underregulation of the private rental sector is twofold: it fosters insecurity within the private market and perpetuates discriminatory practices against families with children and Roma individuals.

The objective of this study was to analyze the mechanisms that create obstacles for young people in accessing affordable and secure housing in cities with varying economic backgrounds, as evidenced by the examination of four urban cases. According to our hypothesis, young people encounter housing challenges in both growing and shrinking cities, but the specific mechanisms behind these difficulties differ based on the local economy's nature and the effectiveness of local housing policies.

As established in the theoretical framework, economic pressures on housing markets result in disparities between supply and demand, influencing housing prices. In growing cities, the presence of a diverse local economy attracts a significant number of high-income residents seeking housing investments. Additionally, favorable conditions for institutional investors exacerbate financialization, further widening housing inequalities in prosperous cities such as Amsterdam and Tallinn. Conversely, shrinking cities experience population decline, leading to housing vacancies that devalue investments in housing, potentially causing deteriorating housing quality, as observed in Chemnitz and Pécs. Theoretically, robust public intervention in housing can counterbalance market pressures in growing cities, while in shrinking cities, it may contribute to reduced housing inequalities but potentially exacerbate issues such as housing devaluation, segregation, and declining population.

The selected case studies, representing four major ideal types of European urban areas concerning economic strength and local housing policies' efficiency, align well with the theoretical framework and exhibit key attributes of these ideal types. However, our analysis uncovered additional factors that could enrich the concept of economic city status's consequences on housing inequalities among young people.

Concerning economic potential, we found that population size alone may not adequately predict housing demand pressure as additional demand arises from temporary factors such as education and tourism. This supplementary demand bolsters strong economies in Amsterdam and Tallinn and increases demand in cities where outmigration dominates, like Pécs.

Structural impacts of economic growth or shrinkage appear to have a neutral effect on the scale of spatial segregation, which remains a prevalent phenomenon in all four case study locations, regardless of their economic strength. However, the sources of segregation differ across areas, but a common underlying factor is ethnic diversity, which exhibits strong path-dependent characteristics. Economic attractiveness, as seen in Amsterdam, contributes to ethnic diversity as households migrate for employment opportunities. In Chemnitz, a lower proportion of residents have a migration background compared to larger German cities, yet they are spatially concentrated in the city's inner areas, necessitating comprehensive social interventions. Tallinn's historical division between Russian speakers and native Estonians has led to social and spatial clustering, while in Pécs, the Roma minority settled during the socialist industrialization, leaving a lasting impact on spatial structure. Notably, public housing policies in Tallinn and Pécs, where public housing stocks are limited, can inadvertently exacerbate spatial segregation by concentrating the stock in already-segregated urban areas.

The cases shed light on the dual and unitary aspects of rental systems under varying growth pressures or their absence. In cities with unitary rental structures, the situation for young people can differ significantly. For example, in Chemnitz, where economic pressures are less relevant, the unitary system can accommodate a wide range of young people, from the most vulnerable to the more affluent. However, this is not the case in Amsterdam, where educated young people with modest incomes may not qualify for the extensive public rental system and must navigate the liberalized private sector. In Pécs and Tallinn, the public rental sector is not even truly dual as it is insufficient even for the most needy, forcing a large proportion of vulnerable young individuals into the insecure private rental sector.

The interplay of structural and welfare factors illustrates that even when local housing policies are de-commodified and the public sector regulates a substantial share of the housing stock, market forces can prevail. This is evident in Amsterdam, one of Europe's most publicly controlled housing markets, which struggles to resist market pressures. Consequently, access to affordable and secure housing for the younger generation worsens over time as can be seen in Table 2, which illustrates the additions of the case study analysis to the original theoretical categorization.

The second hypothesis we sought to investigate through the four case studies concerns the competence and effectiveness of local housing policies in mitigating the impact of economic pressures, or the absence thereof. Our findings suggest the following:

• Despite housing being theoretically a localized issue in most European cities, local governments often have limited maneuverability due to governance from regional, national, or EU levels. The four cases illustrate the paramount significance of housing frameworks established beyond the local level. These frameworks encompass legal aspects such as rent setting, rent capping, contract types, and taxation, along with financial support elements that render local authorities highly dependent.

• The analysis of the four cases revealed that even when economic pressure (or its absence) is a recent development in some areas, housing policy resembles a large ship: altering some components can be straightforward, yet the fundamental concept underlying it is profoundly path-dependent and challenging to reconceptualize. This includes aspects such as the proportion of the ownership sector, the role of the state in funding local investments, rent regulations, and unlimited rental contracts.

Hoekstra (2020) contends that a shift toward the local level in housing policies is imperative in both research and policymaking. Nation states are progressively diminishing in their capacity to shape housing schemes. Our research does not firmly support the erosion of the competence of nation (or regional) states in housing matters; for instance, in Hungary, centralization processes are underway in various welfare service domains, and the legal and financial framework for ownership and tenancy appears to be primarily governed at the state level across all four locations. Nevertheless, we can advocate for a localization approach due to diverse local needs, which necessitate greater autonomy for local public authorities.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://uplift-youth.eu/local-reports/.

ÉG, NK, and SK are jointly responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study and jointly performed the analysis of its results as well as drafting and finalizing its chapters. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The article is based on the research results of the UPLIFT project that has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 870898. The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the European Union. Neither the EASME nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to József Hegedüs from the Metropolitan Research Institute for his valuable contributions to conceptualizing the research framework and the potential typology of urban areas. Additionally, the authors express their gratitude to Anneli Kährik, Thomas Knorr-Siedow, and Christiane Droste for providing valuable additional information on the housing situation in Tallinn and Chemnitz.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

2. ^While housing policy in most European cities is partially administered at the municipal level in terms of responsibilities, the availability of housing indicators is limited at the city level. Typically, housing indicators are at the national level and extend down to NUTS2 regions (as seen in EU-SILC and EQLS). There are exceptions, such as the Eurobarometer global urban house price and affordability indicators. However, these indicators are limited in scope, covering only a select number of cities and housing aspects (Hoekstra, 2020).

3. ^UPLIFT, D1.3 Atlas of Inequalities, 2021.

4. ^For further details on the initial selection process of the 16 urban areas, you can refer to pages 45–46 of Deliverable 1.2 of UPLIFT, which is available at the following link: https://uplift-youth.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/D12-Inequality-concepts-revised_october-2021-web.pdf.

5. ^You can find more information about the classification of the 16 urban areas and an initial evaluation of the local welfare systems in Chapter 6 of Deliverable 2.4. at https://uplift-youth.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/D2.4_Synthesis_Report-of-the-16-urban-reports.pdf.

6. ^The 16 Urban Reports and the eight Case Study Reports can be found at https://uplift-youth.eu/research-policy/.

7. ^The Urban Reports were developed through a comprehensive interview process conducted in each of the four cities. In Amsterdam, eight interviews were held with policymakers and NGO representatives. In Chemnitz, 12 interviews were conducted, primarily in the form of group interviews. Pécs saw 12 interviews with policymakers and NGO members, while in Tallinn, eight interviews were conducted with representatives from the public sector. These interviews provided valuable insights and data for the UPLIFT project's research and analysis.

8. ^As part of the Case Study reports, additional interviews were conducted to gather comprehensive data and insights. Amsterdam saw eight interviews with policy implementers, while Chemnitz had nine interviews. Pécs conducted 22 interviews, and Tallinn conducted eight interviews. These interviews, in addition to the 40 interviews with currently and formerly young people, contributed significantly to the research and analysis carried out within the UPLIFT project.

9. ^The Capability Approach, developed by Nobel laureate economist-philosopher Amartya Sen in the 1980s, is aimed at providing a deeper comprehension and interpretation of contemporary poverty, social disparities, human development, and overall wellbeing. This approach perceives specific life trajectories as outcomes resulting from a multifaceted interplay among diverse elements, including the system's characteristics (e.g., economic, housing, and education), individual perceptions of the system, and various micro-level, individually motivated factors.

10. ^https://www.tallinn.ee/en/news/tallinn-city-budget-2022-exceed-billion-euros

11. ^Die Entwicklung volkswirtschaftlicher Rahmendaten der Stadt Chemnitz, 2022.

12. ^Residential Investment, Market report 2019/2020 in Dresden, Leipzig, Halle (Saale), Chemnitz and Zwickau. https://www.engelvoelkers.com/en-de/commercial/doc/Sachsen_WGH_2019_2020_EN_Web.pdf.

13. ^Approximately one-fifth of the local GDP is believed to originate from the expenditures of both Hungarian and international students (source: Pécs ITS, 2014).

14. ^In 10% of the residential dwellings, there are no registered inhabitants, and as such, they can be considered vacant.

15. ^Source of statistics: https://koltozzbe.hu/ingatlan-statisztikak.

16. ^There are no exact data on the share of the Roma population in Pécs. According to the 2011 Census, 4.6% of the population in the county that includes Pécs (Baranya county) self-reported as Roma.

Aalbers, M. B. (2016). The Financialization of Housing. A Political Economy Approach. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315668666

Arundel, R. J., and Doling, J. (2017). The end of mass homeownership? Changes in labour markets and housing tenure opportunities across Europe. J. Hous. Built Environ. 32, 649–672. doi: 10.1007/s10901-017-9551-8

Boterman, W. R., Musterd, S., and Manting, D. (2021). Multiple dimensions of residential segregation. The case of the metropolitan area of Amsterdam. Urban Geogr. 42, 481–506. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2020.1724439

Coulter, R., Bayrakdar, S., and Berrington, A. (2020). Longitudinal life course perspectives on housing inequality in young adulthood. Geogr. Compass 14, e12488. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12488

Dewilde, C., and De Decker, P. (2016). Changing inequalities in housing outcomes across western europe. Housing, Theory and Society 33, 121–161. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2015.1109545