- 1Institute of Social Studies, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

- 2School of Education, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

- 3Research Institute for Quality of Life, Romania Academy, Bucharest, Romania

In the last decades, young people not in education or employment have become the focus of policy-makers worldwide, and there are high political expectations for various intervention initiatives. Despite the global focus, there is currently a lack of systemic knowledge of the factors supporting policy-making. Therefore, using scoping review methodology, a systematic literature overview of research findings in 2013–2021 on young people not in education or employment will be provided. The research revealed five categories to consider from a policy-making perspective: “NEET” as a concept, the heterogeneity of the target group, the impact of policies for young people, possible interventions, and factors influencing young people's coping strategies. Based on analysis, the target group requires applying the holistic principle where the young person is a unique person whose involvement in service creation supports the service's compliance with the actual needs of young people. To support young people, it is important to consider differences within a single social group; the interaction between the different site-based policies; young people's sense of self-perception and autonomy in entering support services; possible coping strategies and the need to provide support in a time and place-based flexible and caring environment through multidisciplinary teams. The study's results support the importance of implementation and the identification of existing opportunities of the EU's reinforced Youth Guarantee guidelines and point to possible future research topics related to the target group.

1. Introduction

NEETs are individuals who are Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEETs). In 2010, formal recognition of NEET as a priority target group was agreed upon by the European Commission's Employment Committee as part of the Europe2020 strategy, facilitating the potential for inter-state motoring of this vulnerable group. Shortly after, it was found that there were 14 million NEETs in Europe aged 15–29 (Youth NEETs) representing 33% of the total number of young Europeans (Mascherini et al., 2012). The challenges associated with supporting Youth NEETs are complex. They are compounded by the heterogeneity of this grouping, particularly when interventions at policy or grassroots levels are not sensitive to the bespoke requirements of those they aim to support (Cabasés Piqué et al., 2016; Hutchinson et al., 2016; Sutill, 2017; García-Fuentes, 2019). In other words, there is a disconnection between the homogeneous approach of policy and the heterogeneous focus of implementation with youth NEETs.

Following this, it is clear that youth NEETs are heterogeneous and, as such, have many different reasons for inclusion in this grouping, not consistently negative and sometimes a temporary choice (Simmons and Thompson, 2011; Sutill, 2017). It is imperative, therefore, to understand these young people's experiences and go beyond the homogenous grouping that generates statistics and generalizations so often used to inform policy (Sutill, 2017). Some work has been done in this area with a bespoke, multi-disciplinary, holistic approach considered most effective in supporting youth NEETs (Kolouh-Soderlund, 2013; Gaspani, 2019). Hence, given the complexity of the target group and the need for reflexive engagement between policy makers and grassroots actors, there is a need to consider that policy-making activities should navigate between European, national, regional, and local levels (Hooghe and Marks, 2003; Stanwick et al., 2017; Sergi et al., 2018; Paabort and Beilmann, 2021) to uncover what works with which target group and under what conditions (Hudson et al., 2019; Petrescu et al., 2022).

A decade after the formal recognition of NEET-status, some progress in reducing the youth NEET incidence rate is evident after the introduction of the Youth Guarantee in 2013, which was set up to support young people under the age of 25 (or 29 in more than half of EU countries) within 4 months of leaving school or becoming unemployed by providing quality work, continuing education, apprenticeships, or traineeships (The Reinforced Youth Guarantee, 2021). This has had a positive impact on reducing the number of young Europeans falling into NEET-status. In 2020, the European average proportion of Youth NEETs stood at 16.5%. However, the experience of member states has not been uniform, with the highest rates in Italy (28.9%) and Greece (26.8%) and the lowest in Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Sweden (Eurostat, 2020). Indeed, at a European Commission level, there is clear intent to address this as the previous Youth Guarantee programs have been renewed and reinforced with financial support from the European Commission (2020). The European Commission has issued several guidelines to implement the Youth Guarantee like mapping, awareness-raising about the target group, offering quality services, improving data collection and monitoring systems, therefore taking into account national, regional and local circumstances and paying attention to the differences of the young people in the target group (European Commission, 2020). While this is welcome by those who work in this emergent field, at present, it remains unclear as to what connection policy is making to the real-world challenges that youth NEETs face and whether or not policy and practice are, in fact, reflexively informing each other, cognisant of the heterogeneity of the youth NEET experience.

Despite a growing body of literature relating to NEETs, including several thematic and statistical overviews that have been published (Carcillo and Königs, 2015; Eurostat, 2020), a thorough database search did not yield any previous systematic, scoping, umbrella or integrative literature overviews of work carried out with NEETs. In this scoping review, we provide an overview, across different disciplines, in particular, of the variety in research topics related to the target group and on connections between policy and practice specific to NEET youth in Europe. Using this approach, we aim to go beyond their homogeneous profile and provide a much needed, nuanced characterization of NEETs to enable more informed policy-making for the target group. In this paper, we present a systematic examination in the period of 2013–2021. This work herniated the following research questions:

1. What are the main focus topics for research related to the target group of NEETs at the European level in the period 2013–2021?

2. What are the main findings and policy recommendations related to the target group of NEETs at the European level for the period 2013–2021?

3. What are the primary needs for further research on the policy-making guidelines for the reinforced Youth Guarantee for young people in NEET-status?

2. Methodology

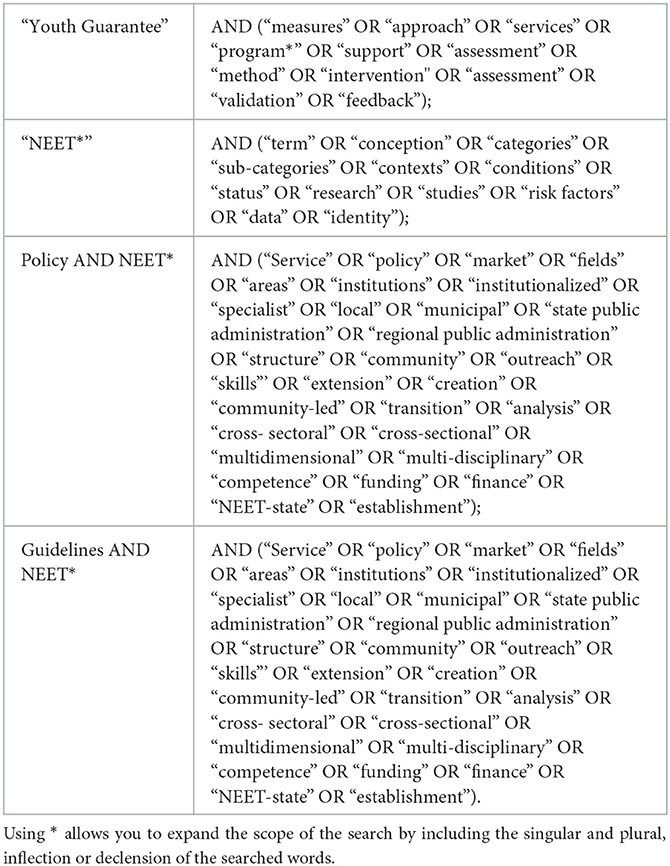

The approach taken, a scoping review methodology (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005; Torraco, 2016), is founded upon systematic literature review methods (Denyer and Tranfield, 2009). The development of the review protocol was carried out in line with the systematic review methodology that informed the review protocol, and the scoping review methodology informed the analysis and synthesis of the search returns. The scoping method selected as the body of work relating to NEETs has experienced rapid growth in recent years (Simões et al., 2022) and is quite broad. This study presents an opportunity to map the key concepts and trends in the extant literature (Colquhoun et al., 2014) to inform new directions for research in this emergent field. While a systemic review may provide a comparison of methods, concepts etc., in an established field, this approach acknowledges the emergent nature of this field and allows the research team to characterize the complexity of the issue at hand (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005). Potential keywords that might be included in the final search string were initially collated. As a trial-and-error process, keywords were tested using shorted, preliminary search strings in the Scopus database to determine the relevance of the results to the study. The final search string is presented in Table 1.

Building on the PCC framework that shaped the research questions, inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) were developed using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) model as an initial framework.

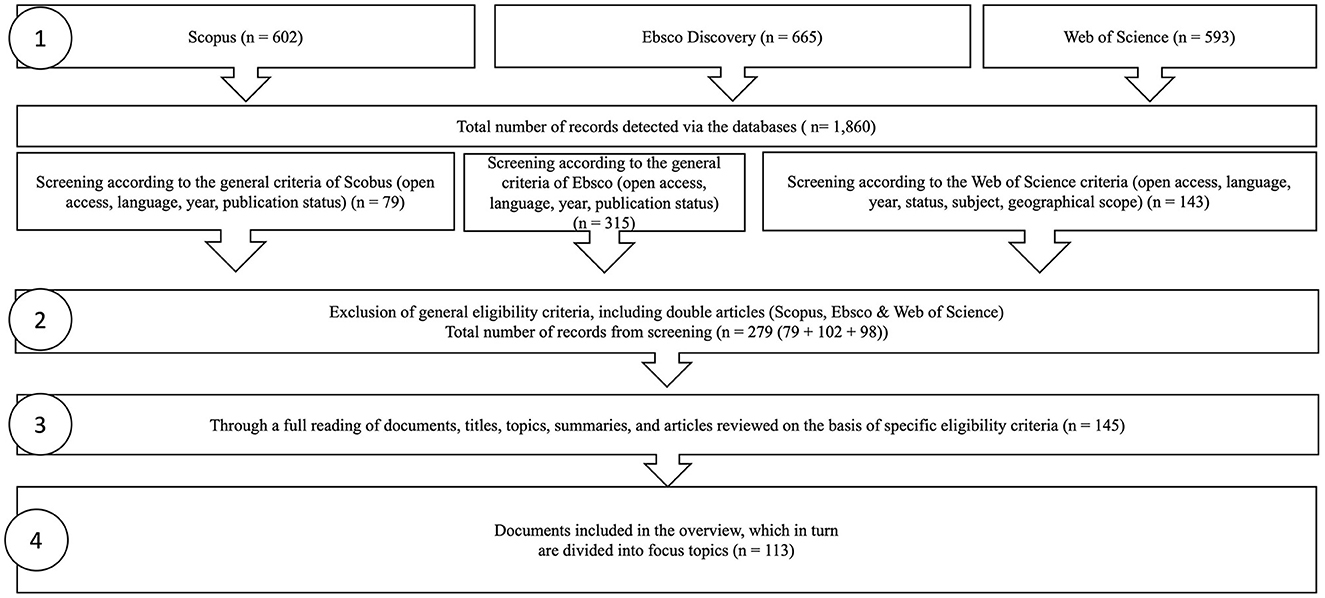

After finalizing the search strings, they were applied to three electronic databases—Scopus, Ebsco and the Web of Science—and returns were restricted to the period 2013–2021. The choice of timeframe stems from the first implementation period of the EU Youth Guarantee in order to take stock of the articles published during this period before the enforcement of the new reinforced Youth Guarantee programme in 2022. Initially, the search was limited to international peer-reviewed articles in social science journals, but due to a lack of returns related to the topic, a broader search of journals was conducted. Using the PRISMA-P flow process (Figure 1), a total of 1,860 papers were identified in the electronic databases (Scopus, n = 602; Ebsco, n = 665; and Web of Science, n = 593).

After removing studies that were non-English, inappropriate due to their geographic scope, or duplicates, 279 papers were progressed for review or relevance to the study resulting in 113 papers progressing to the data extraction stage. Data were extracted independently, in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1), by two research team members. A third member of the team was designated as a dispute resolution rater. For each of the papers, common characteristics were extracted and tabulated: type of paper, methodological approach, participant information and inclusion criteria, study location, and a summary of main study findings. Only titles, abstracts and keywords were considered during the development of the search string. The returns presented five categories of interest: “NEET” as a concept; the heterogeneity of the target group; the impact of structures and policies for young people; possible interventions, and factors influencing young people's coping strategies. As the majority of the studies returned were qualitative or mixed methods, the data extraction and analysis process rested upon a process of thematic analysis (Clarke and Braun, 2014).

The papers included in the study were read three times: the first reading during the screening process, the second reading to determine the relevance of the study design and findings, and finally, to review the studies in relation to the total studies included. Data extracted aligned with the PICO structure of the inclusion and exclusion criteria and was stored in a spreadsheet (Figure 1).

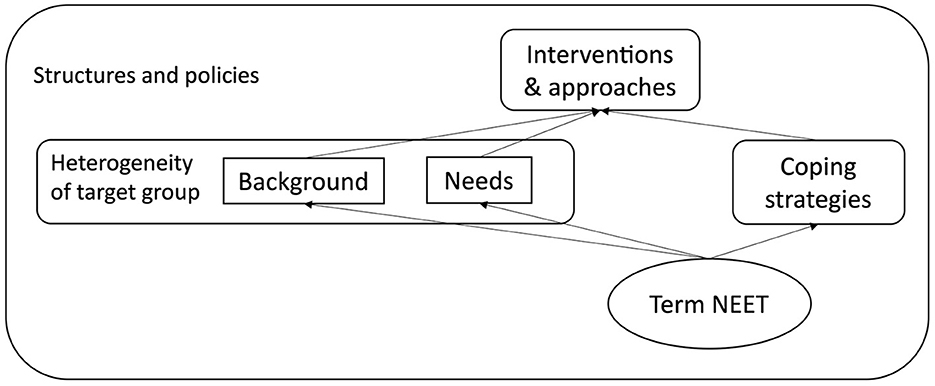

Qualitative content analysis was carried out using an inductive, scientific realist approach (Mayring, 2004). The analysis focused on the different academic findings in the studies that underpin service and policy design for the target group. The first stage of this analysis established an initial coding framework of themes or constructed codes. Secondly, each constructed code was then exploded to capture commonalities under the initial coding framework. Finally, we synthesized the exploded aspects across all the returned studies and presented contextual sensitivities associated with each constructed code, mapped backwards through the commonalities. The constructed codes (further categories) established were (Figure 2):

1. “NEET” as a concept;

2. The heterogeneity of target group and their needs;

3. The impact of structures and policies for young people;

4. Possible interventions and approaches;

5. Factors influencing young people's coping strategies.

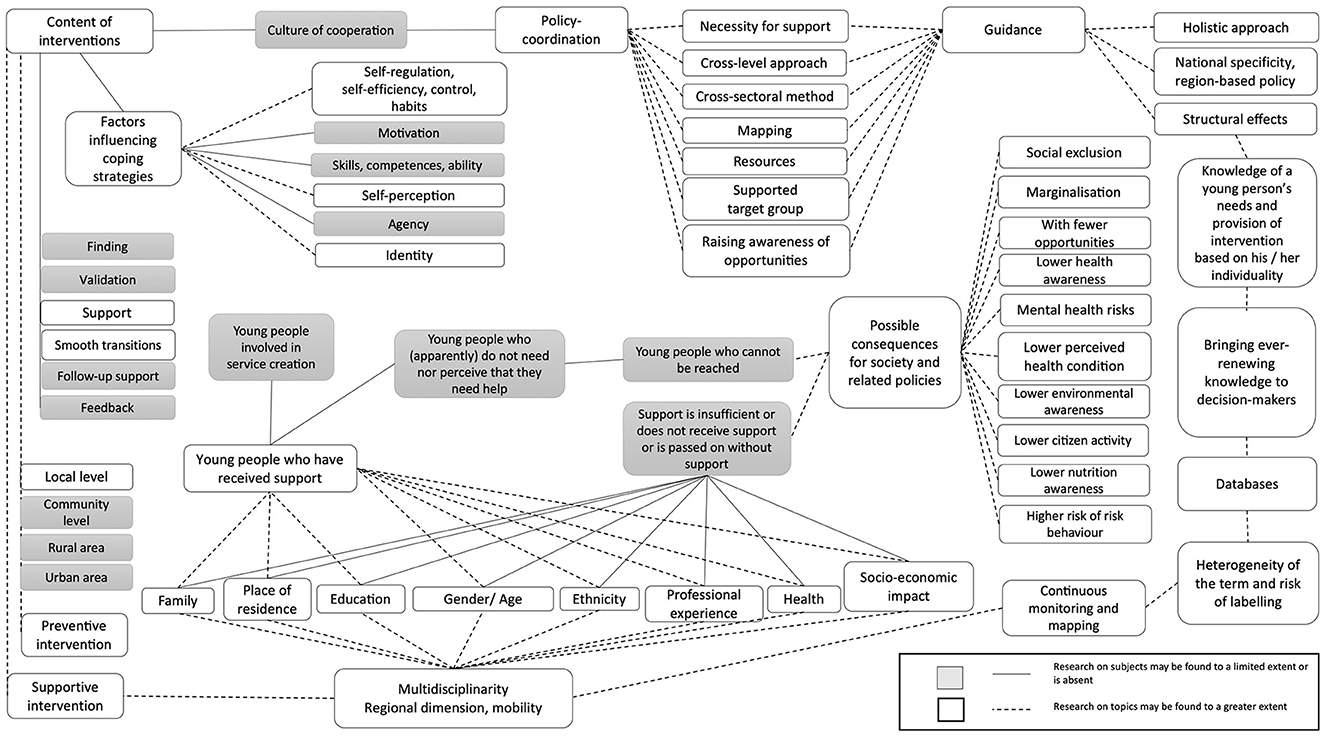

In describing the results, the main focus is an overview of the different academic findings in the categories. In order to describe the findings and to provide thematic context, the authors have prepared and used a visualization, which, based on Aasa (2020), allows us better describe the broad content and the phenomenon. In particular, the graphs provide a quick overview of the variability of the themes identified in the surveys, allowing noticing connections or contradictions between different studies or categories. Topics for which any or only a few studies were found are highlighted as limited in the Section 4.

3. Results

3.1. “NEET” as a concept

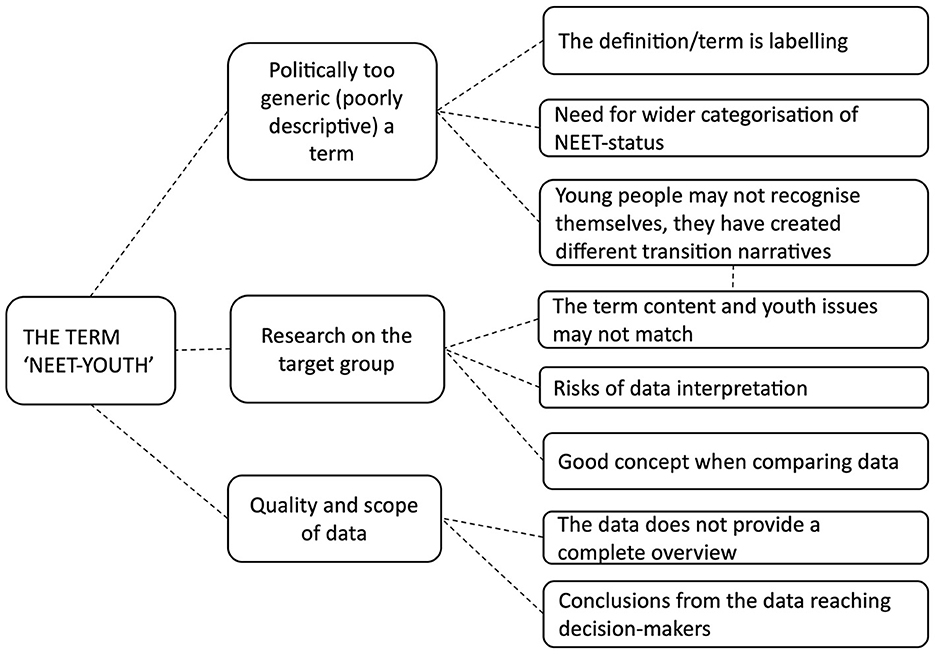

Based on the analysis of the literature overview, it may be concluded that research related to the concept NEET is mainly divided into three categories: research papers that show that the concept used for NEETs (NEET, not in Education, Employment, or Training) is too general and does not allow to see the heterogeneity of the target group (1), research that identifies the limiting and enabling factors based on the concept referring to the target group (2) and research that provides guidance on the use and interpretation of national data related to the target group (3) (Figure 3).

Sergi et al. (2018) suggest that institutionalizing NEET-youth as an analytical category may prove problematic since it may not clearly identify specific vulnerable subcategories, leading to ineffective one-size-fits-all policy interventions (Cabasés Piqué et al., 2016) and as broad policy interventions may not meet the needs of many young people (Maguire, 2018; Bonnard et al., 2020). Understanding the lifestyle of young people from their perspective is essential for policy-making (Poštrak et al., 2020). Research papers based on meetings with the NEET-youth can contribute to a body of knowledge gained mainly from official NEET-youth data, but the actual input is broader (Holte, 2018).

Several studies present young people's vision of constructing the meaning of the concept “NEET,” where they do not perceive themselves as the NEET-youth (e.g., Parola and Felaco, 2020). The challenge, therefore, is to deconstruct the NEET label based on research, as it does not reflect the heterogeneity of situations that a young person finds himself/herself during his/her career and, as a result, the creation of an effective social policy may be hampered (García-Fuentes, 2019). There is a need to see behind the big data that the created data systems and the basic values of their creation do not automatically normalize new beliefs and values (Thornham and Gómez Cruz, 2016). However, Holte et al. (2019) mention that databases created based on the concept NEET are a good concept for transnational comparisons. Concerns have been raised that data gaps lead to ambiguity and inconsistent policies (Maguire, 2015), overestimation of the proportion of NEET-youth, especially among men (Saloniemi et al., 2020), and policies that do not work because NEETs are excluded from the public employment services registers, and there is little knowledge about the actual size and structure of the population (Saczyńska-Sokół, 2018). In addition to the data and their interpretation, Batini et al. (2017) stress the need to consider how different empirical research results would reach decision-makers to create interventions. Quintano et al. (2018) specify that in analyzing activities and reducing interventions to diminish the proportion of NEETs, it is necessary to distinguish between the unemployed and the inactive because helping young people out of these statuses is different.

The review shows that the concept is necessary for comparison but there is a need for a better understanding of its nature to ensure that policies support young people's real needs.

3.2. Heterogeneity of NEET youth

It is clear from the literature reviewed (Figure 4) that there is a critical need to address the heterogeneous view of NEETs regarding gender, place of residence, type of intervention, available financial support, disability and timing of interventions.

NEET-youth typically have experience of unemployment, more unemployed friends than other young people, and they come from families with limited financial opportunities (Sadler et al., 2015; Vancea and Utzet, 2018). Indeed, García-Fuentes (2019) emphasizes that a disconnection between family, education and employment policies can limit a young person's opportunities to be socially independent. The findings of NEET-related gender-based studies vary from country to country. For example, Quintano et al. (2018) found that, in Italy, living with a male partner reduces the likelihood of women falling into NEET status and vice versa for men. However, Maguire (2018) points out that in England, primarily regarding NEETs, women are relatively isolated and considered more vulnerable. In addition, individuals whose parents have a low level of education and experience an extreme marginalization are more likely to fall into NEET status (Alfieri et al., 2015; Quintano et al., 2018; Bania et al., 2019; Kevelson et al., 2020). Studies in Finland have found that services provided by the youth labor market services direct young people to lower positions in the labor market; furthermore, gender differences have emerged, resulting in an institutional pattern that restricts young people's labor market transition pathways (Saloniemi et al., 2020; Haikkola, 2021). This can also compound the challenges females face as they often take on the crucial role of carers for family and relatives (Quintano et al., 2018). These risks are heightened in young people with an immigrant background, and unaccompanied and refugee youth have been found to be at a higher risk of becoming NEETs (Manhica et al., 2019).

Some attention has been paid to second-generation immigrants from low-skilled migration waves, who are more likely to find educational and employment trajectories which require lower skills (Laganà et al., 2014). Russell (2016a) identifies similar directions, especially for young unemployed mothers, who were referred to inappropriate educational and training courses based on their young-unemployed-mother status rather than encouraging them to embark on an individual path that meets their specific needs as well as career aspirations. The gender-based limiting factor has also been found in the case of young women with intellectual disabilities (Luthra, 2019). Therefore, understanding and working with the target group requires a holistic approach that considers several factors to increase employment opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities and, thus, full participation in society (Luthra et al., 2018; Saczyńska-Sokół, 2018; Luthra, 2019). It has been found that gender gaps are not sufficiently considered in political debates, contributing to the persistence of inequalities (Rodriguez-Modroño, 2019).

In addition, the need to notice the different needs of young people in foster care is emphasized, noting that several countries have failed to ensure adequate education policies and that the target group later had a high proportion of NEETs (Ruesga-Benito et al., 2018; Berlin et al., 2020). Relationships with economic status, residence and location, parents' level of education, and relationships with parents and childhood risk behaviors have been identified as family factors contributing to falling into NEET status. Russell (2016b) brings out that a young family living in poverty often remains stuck, and while young people may want to get out of this cycle, there is a dearth of opportunities to do so, which provide pathways to suitable employment through interventions (Maguire, 2018). The stability of the familial relationships is also a factor in this, as Selenko and Pils (2019) denote; young people with poor relationships with parents were likelier to drop out of the education system during the 1st year. Therefore, young people, who experience childhood abuse, are associated with poor socio-economic outcomes at a later age (Pinto Pereira et al., 2017).

Research on risk behavior is broadly divided into two categories, showing that the need for a proactive approach among NEETs stems from the risk of falling into NEET status if the young person remains unsupported and the subsequent impact of risk behavior is due to the young person's family background. In the case of young people from privileged families, early risk behaviors (use of stimulants, early sexual initiation) are not associated with acquiring NEET status, but for young people with less privileged backgrounds, particularly males, early introduction to stimulants (smoking; drug abuse; and women in NEET state confirmed more unplanned pregnancies) predict adverse effects later in life (Andrade and Järvinen, 2017; Campbell et al., 2020; Tanton et al., 2021). In contrast, Juberg and Schiøll Skjefstad (2019) highlight that there is little evidence that falling into NEET status is a consequence of drug abuse, but concede that young people's alcohol and drug issues clearly would reduce their ability to work in the long run suggesting that care should be taken about creating myths about NEET youth.

The role of education in ameliorating such challenges is evident, as dropping out from education increases the vulnerability of young people, particularly during times of economic crisis (Salva-Mut et al., 2016), and as the lack of educational qualifications is detrimental to all populations (Bonnard et al., 2020). However, Stuart (2020) stresses that the direct impact of early school leaving is controversial in concept of becoming a NEET and is rather influenced by the lack of family income and the privilege of receiving an education. A similar approach is supported by Pitkänen et al. (2021), who emphasize that the socio-economic resources of NEETs parents are more critical than the unfavorable childhood experiences of young adults in education and employment and, thus, a social policy that supports disadvantaged families on a socio-economic level may help smooth these transitions. To boot, national family policies may help to address this issue (Kevelson et al., 2020).

The location is also a significant factor. Young people living in rural areas have limiting factors (Simões, 2018) in order to ensure more efficient support, institutional arrangements and practices in various fields (social affairs, health, education, and employment) that do not meet the needs of young people can frustrate young people into giving up on employment (Rikala, 2020). Therefore, big city neighborhoods with high school drop-out and high crime can impact the likelihood of young people engaging in educational and employment opportunities, as living in a disadvantaged neighborhood increases the likelihood of becoming a NEET (Karyda, 2020). Cajic-Seigneur and Hodgson (2016) and Agranovich (2020) stress that differences in the quality of provision of education in the district may increase inequalities experienced by young people in education or the labor market. Blinova and Vialshina (2017) found that diversities between rural and urban youth were chiefly in job preferences, work experience and satisfaction with life and path choices. However, in concept of location, the importance of the location of interventions and services is also highlighted. Jonsson and Goicolea (2020) underline that youth services should not be located in or near government buildings, for example, as part of the target group may be disappointed in the institutional agencies and feel incompatible with current structures.

Studies highlighted the need to organize support for NEETs through different areas and levels. The local and community levels were described as the primary levels. The findings of the local level refer in particular to the need to review labor market opportunities (Blinova and Vialshina, 2017), involve different local authorities to reduce fragmented policies (Maguire, 2020), to support young people without qualifications more effectively (Salva-Mut et al., 2016), to understand better links between micro, meso, and macro levels (Arumugam et al., 2019), to analyse education policy from a regional perspective (Ryan and Lórinc, 2015), to study the local view (Karyda and Jenkins, 2018), to enhance the cooperation between local and national authorities (youth physical and virtual mobility; Anne et al., 2020a), to review structural restrictions on local education and employment (Russell, 2016a,b), to include local alternative education providers in support (Cajic-Seigneur and Hodgson, 2016) and for directing information to young people and to use in particular local level institutions (libraries, youth clubs, clinics, etc.; Coates, 2016).

Following on from this, regarding the concept of community, there is potential for involving the agricultural sector in supporting young people in realizing the value of higher education as a link between the community (Simões, 2018), between economic prosperity (Kevelson et al., 2020), community potential to reduce youth marginalization (Russell, 2016a,b), community-based organizations and the community as a geographical location (Miller et al., 2015) where young people can be found or supported (Coates, 2016) with family and friends (Bǎlan, 2016).

The chapter shows that, while the concept may imply a universal need for support, the target group does not have similar needs, recourses and backgrounds, so support for young people needs to consider their uniqueness and different stages of their lives.

3.3. The impact of structures and policies for young people

It was evident in the literature that young people's opportunities, in term of education and the labor market, vary across Europe and that the homogeneity of national support systems and structures should not be taken for granted. Although young people have been found to have the highest levels of wellbeing in Nordic countries, there are also differences in basic categories (Jongbloed and Giret, 2021). Therefore, different nationalities living within a country are not homogeneous; there are variances across social groups within the same country (Bacher et al., 2017). It has been found that policy-makers can underestimate the interactions between micro, meso and macro levels (Sergi et al., 2018), with several studies indicating that the NEET category is directly affected by structural changes (Kelly et al., 2015; Holte et al., 2019; Amendola, 2021), notwithstanding changes in the demographic structure (Kelly et al., 2015). In particular, globalization and neoliberalism (Holte et al., 2019), the previous economic downturn (Scandurra et al., 2021), economic policy decisions (Simões, 2018), normalization of flexible labor market opportunities (Nielsen et al., 2017), labor liberalization (Katznelson, 2017), as well as the education system and labor market structure (Kelly et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2015; Ryan and Lórinc, 2015; Novkovska, 2017; Avila and Rose, 2019) are considered such structural changes.

In the younger cohorts, NEET status mainly influences the transition from school to work, while in the older cohort, this status is often due to labor market performance and institutional factors (Bradley et al., 2020; Caroleo et al., 2020). At the same time, it is also clear that when institutional practices and constraints limit a young person's activities, the young person eventually gives up trying to obtain a job, which has a profound effect on him/her from mental health and personal agency perspectives (Serrano Pascual and Martin Martin, 2017; Saczyńska-Sokół, 2018; Rikala, 2020). Csoba and Hermmann (2017) point out this as a significant contributing factor, as it is essential to integrate different areas that allow establishing links between policies and supporting young people's long-term perspectives. Inter-policy coherence policies is considered important in developing transparent and smooth transition paths, and the absence of such dialogue presents an increased risk of entering into NEET status (Ose and Jensen, 2017; Thompson, 2017; Görlich and Katznelson, 2018; Iacobuta and Ifrim, 2020).

A combined and adapted cross-cutting policy is a key factor in reaching and supporting more complex target groups. Thompson (2017) and Saloniemi et al. (2020) have found that the limited opportunities in the labor market for young people with medium and low levels of education may otherwise exacerbate social and educational disadvantages, which is why the marginalization of education and the key center of support for young people should be of concern to policy makers. Policies and interventions, which focus on trusting young people and gaining trust, which has been largely abandoned by many parts of society, can help them restore their wellbeing and, next to it, have the courage to enter again a world that has repeatedly failed them in the past (Jonsson and Goicolea, 2020). The risk factor highlights the rapidly growing propensity to diagnose and offer self-made solutions to young people (Görlich and Katznelson, 2018; Haikkola, 2021). At the same time, research projects highlight the vulnerability of young people with higher levels of education, as their access to the labor market depends on the needs of the labor market, which in turn depends on national education and labor market policies (Scandurra et al., 2021).

The education field is a critical sector in bringing young people aged 16–18 back into the support system (Alegre et al., 2015; Quintano et al., 2018) along with youth policy and non-formal education providers, where holistic, coordinated interventions with young people can encourage them to engage with a range of support services that can prevent social exclusion and marginalization into NEET status (Quintano et al., 2018; Ruesga-Benito et al., 2018; Robert et al., 2019; Haikkola, 2021; Scandurra et al., 2021).

Regarding policy-making and its implementation, some research projects highlight the importance of developing awareness and status perception of professionals working with different young people compared to other professionals in the field, which can also influence their work and decision-making in supporting young people. Beck (2015) points out that practitioners working with NEET-youth perceive that they have a lower status than teachers, which in turn can affect the fact that they might encourage young people to take up low-skilled and low-paid jobs that they themselves have had experiences with. Avila and Rose (2019) highlight that the work of such professionals is both guided and constrained by funding rules and structures. This can increase the risk as seen in terms of increased performance requirements, which focus on the implementation of indicators and may lead young people to become trapped in systems (Görlich and Katznelson, 2018). Influenced by this disconnection between the guidelines and the actual needs of young people, professionals often feel the need to support and raise young people, sometimes behaving in ways they believe are not in perfect alignment with the guidelines provided (Beck, 2015).

In summary, young people's opportunities in education and the labor market vary across Europe, and structural policy decisions have a significant impact on better supporting young people.

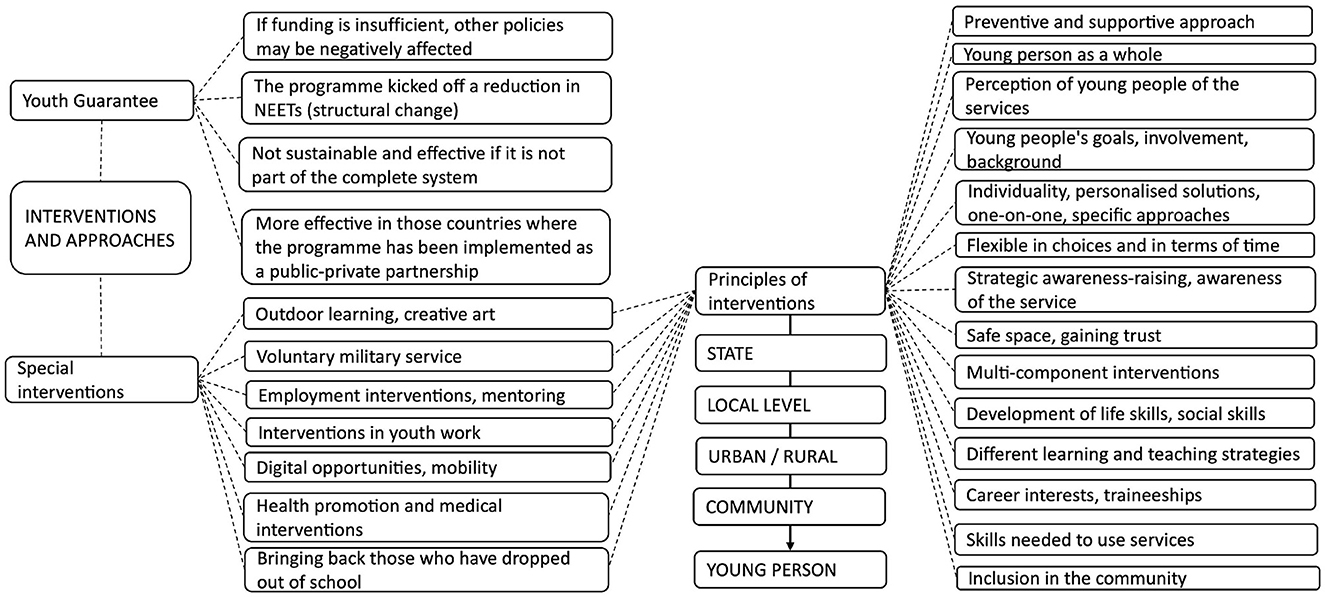

3.4. Intervention and approaches opportunities

Research on approaches for young people having NEET-status may be divided into three types: interventions related to the implementation of the Youth Guarantee in the Member States, interventions for young people who are not studying or working, and general proposals for interventions in work with young people who are not studying or working (see Figure 4).

Research related to the Youth Guarantee was divided into two sub-categories, i.e., the country-specific and pan-European research projects. In general, the fulfillment of the purpose of the Youth Guarantee, the design of interventions and funding have been examined. Poštrak et al. (2020) highlight that the Youth Guarantee measures are generally aimed at the efficiency of human capital and are a diversified investment, with the support of the programme, that there was a significant structural breakthrough among NEETs almost everywhere in 2014, as the number of NEETs began to fall (De Luca et al., 2019).

In general, the programme's design and measures align with the planned principles (Rodriguez-Modroño, 2019; Focacci, 2020), and it has reached the most in countries that have successfully developed public and private partnerships (Stabingis, 2020). The involvement of social undertakings (Hazenberg et al., 2014), the local community and civil society institutions (libraries and youth clubs; Zhartay et al., 2020) is highlighted as a material factor. Also, some other factors like youth's experiences with and perceptions of public employment services (Shore and Tosun, 2019) or governance arrangements and public-private cooperation (Tosun and Schaub, 2021) or evidence used (Petrescu et al., 2022) determine the success of the Youth Guarantee implementation. Therefore, there are several research projects providing general suggestions for creating interventions. In the case of outdoor learning (surfing), it has been emphasized that results showed significant improvement in the level of fitness, satisfaction with personal appearance, and a positive attitude toward school and recommends the use of vulnerable young people struggling with a standard education (Hignett et al., 2018). Also, voluntary military service increases access to employment, especially for young people under 21, in addition to better mobility and compliance with qualifications (Anne et al., 2020a,b). The use of creative art is recommended as a new intervention, which can help reduce barriers to learning (Simmons, 2017).

A shared feature of employment (Avila and Rose, 2019) and youth centered work intervention (Miller et al., 2015; Robertson, 2017) is creating a safe space where young people receive “a lot of emotional support” and grow in their self-confidence. Miller et al. (2015) indicate that the practice of youth work acted as a glue between young people and their communities, creating opportunities to bring the two parties together and build relationships. Moreover, the mentoring of entrepreneurs has been identified as intervention, enforcing both parties (mentors increased mentoring competencies such as active listening and orienteering skills, feeling good about themselves and a higher self-esteem, social inclusion, and positive attitude toward aging). Also young people in the target group acquired entrepreneurial and vital social competencies, often not accessible to young people, particularly in rural areas and hard to reach in groups (Irwin, 2020; Santini et al., 2020) to prevent young people from falling into NEET status (Maguire, 2015; Jonsson and Goicolea, 2020). In this way, providing a comprehensive and flexible service can improve young people's wellbeing, self-confidence and competencies (Cornish, 2017; Jonsson and Goicolea, 2020), particularly in rural and remote areas (Stain et al., 2019). This mentoring model may work for target groups which experience marginalization was a combination of approaches based on individual, holistic and structured work, which must consist of several levels (Cajic-Seigneur and Hodgson, 2016; Mawn et al., 2017; Simmons, 2017; Tomczyk et al., 2018; Poštrak et al., 2020). Learning in such contextualized circumstances is not without challenges, as links to past experiences can reproduce former problems in the classroom and create reluctance (Cornish, 2018), resulting in a need for multi-component interventions, which have been found to reduce unemployment and risky behavior among NEET-youth effectively (Mawn et al., 2017; Ose and Jensen, 2017; Maraj et al., 2019; Sveinsdottir et al., 2020). When successfully coordinated with consistent monitoring of childhood health status, this can lead to better academic performance at a later age (Hale and Viner, 2017).

The perception of the young person's service must be considered when creating interventions: young people must be sufficiently aware of the existence of services, perceive the need to use these services, be in a stable situation and have the skills necessary to use the services, and perceive these services as an advantage available (Van Parys and Struyven, 2013). For example, it has been pointed out that young people with NEET-status have important interrelated challenges in digital literacy and self-efficacy (Buchanan and Tuckerman, 2016), with Thornham and Gómez Cruz (2016) pointing out that having a mobile phone does not automatically mean that young people are mobile and want to or know how to use it. Therefore, communication to reach the service requires conscious work by specialists in supporting young people (Van Parys and Struyven, 2013; Buchanan and Tuckerman, 2016).

Based on the scoping review, it can be pointed out that there are many ways to support young people; it is essential to consider the needs arising from the target group, where services in a caring environment must be flexible in terms of time and place with a tailor-made approach and supported through multidisciplinary teams.

3.5. Factors influencing coping strategies

Reiter and Schlimbach (2015) found seven main competing narratives outlined by young people and discovered that while young people are aware of the problematic nature of the NEET-status, they avoid being associated with this status. Researchers are in broad agreement that this phenomenon requires clear identification within the NEET category—perhaps as “hidden NEET,” as young people are normalizing the situation by being one so as not to see themselves as needy and to place themselves in systems. Saloniemi et al. (2020) found 10 transition trajectories, of which 7 for men and 8 for women were called mainstream paths, which are relatively smooth transitions. However, the rest of the trajectories were considered “wandering paths.” Schoon and Lyons-Amos (2016) point out that one in 10 young people is vulnerable due to a lack of socioeconomic and psychosocial resources and are on the long-term trajectory. Regarding addressing transition theories, Crisp and Powell (2017) believes that this concept offers more potential for understanding youth unemployment and creating policies based on it. It is considered that in addition to considering structural constraints, it is also essential to conceptualize the role of the young person himself/herself in order to understand better the differences in transitions (Schoon and Lyons-Amos, 2016; Nielsen et al., 2017; Saloniemi et al., 2020). Contini et al. (2019) have suggested that young Italian females may not perceive themselves as having a NEET-status but are instead perceived as passive, mainly doing the chores around the house. The authors assert that such citizens may be considered “hidden NEETs.”

The transition that young people experience as they move into adulthood is mainly described in the scientific literature as age cohorts and gender gaps (e.g., Maguire, 2010), young people's sense of self-perception on the journey of transitions (e.g., Görlich and Katznelson, 2018), where they hide their status and normalize their situation (e.g., Reiter and Schlimbach, 2015), mainstream and wandering transition paths (e.g., Saloniemi et al., 2020), the differences between less and more privileged young people on the transition journey (e.g., Stuart, 2020), transition patterns (e.g., Ryan and Lórinc, 2015) and the consequences of the term's narrowness on the transition journey (e.g., Bonnard et al., 2020).

Görlich and Katznelson (2018) indicate, from the policy-making perspective, the importance of understanding the differences between young people and their reactions to the systems created. This provides a perspective to understand how young people perceive themselves in order to reduce inconsistencies between young people and established systems (Görlich and Katznelson, 2018) and the coping strategies that they employ (Gaspani, 2019). Moreno-Colom et al. (2020) point out that as the meaning of a young person's leisure time changes, so does his/her identity and leisure get its meaning in a situation where one is a young person engaged in employment. The difficulties of time planning and the lack of autonomy in organizing one's time (e.g., caring for children) can be a barrier to planning the temporal structure, so time-appropriate relationships with institutions may be shifting or be impossible in everyday life (Gaspani, 2019). At the same time, it is considered that leisure time and its use have a significant impact on shaping young people's identity. Young people may perceive that they are mainly carrying out “unproductive” or irrelevant activities, and the mechanism of self-control to find solutions may no longer be a sufficient coping factor in the case of long-term experience (Bäckman and Nilsson, 2016; Ng-Knight and Schoon, 2017). Self-efficacy has been positively influenced by the existence of a previous employment contract and negatively by longer periods of unemployment (>24 months), thus improving job opportunities may be a prerequisite for a young person having a NEET-status to perceive positive self-efficacy (Simões et al., 2017).

The importance of agency, the motivation and skills of the young person have been highlighted as important. It is emphasized that approaches and policies aimed at NEETs must empower young people and make them aware that they are responsible for their coping mechanisms. Iacobuta and Ifrim (2020) point out that the broader objective of national policies is to support the wellbeing of young people but must not create and encourage dependence on the state. At the same time, existing policies may not be interconnected, and the agency of the youth and the desire for independence may be limited. The results show that some young people choose to stay with their parents for a longer period due to poor labor market conditions and high housing costs (Enrica, 2019).

Katznelson (2017) highlights the need for a contextually deeper understanding of motivation, as the existence of motivation no longer ensures the coping of young people, as the liberalization of the workforce is increasingly central to the labor market and education policies of welfare countries. In addition, it is considered that early skills (especially those acquired before the age of 16), such as reading and writing, protect against later social exclusion in adulthood and have an advantage over those acquired later (Barth et al., 2021).

Digital skills are also identified explicitly as skills necessary for coping in contemporary society. Although it has been found that the internet use of NEETs is similar to that of general peers and that information needs similarly included employment, education and training, information search behavior in this target group was more often passive, unintentional and more unfinished because of a higher digital literacy gap (Coates, 2016). Mobility and logistics are also essential factors in young people's operational strategies. Individual or collective support for young people's mobility is a key factor in their integration into or back into education (Anne et al., 2020b).

It should be considered that some young persons enter NEET-status several times or stay longer in this situation, which in turn may affect coping strategies. Bǎlan (2016) argues that factors contributing to the magnitude of adverse effects are the length of the duration of the status, the recurrence of having the status and entry into this category at an early age. For young people who have been in NEET-situation more than once, negative links between status and earning an income have been found where the salary is lower than in other populations (Andersson et al., 2018) and choices regarding health and environmental awareness (Bonanomi and Luppi, 2020). Connected to this, from a health-awareness perspective, the consequences of the impact of the status are highlighted as a disappointment due to their situation, which can lead to mental health risks (Hammarström and Ahlgren, 2019) and poorer perceived health conditions (Stea et al., 2019).

Due to the economic situation, less valuable and healthy dietary choices are made (Davison et al., 2015; Höld et al., 2018), and health advice and services are limited (Stewart et al., 2017), in turn increases the risk of cancer-related health behaviors. Nordenmark et al. (2015) have found that the health risk is higher in divorced NEETs. Concerning the risk behavior, it is pointed out that young people having NEET-status are at greater risk of alcohol consumption disorder (Manhica et al., 2019). In addition to an unhealthy diet, physical activity also decreases, which in turn worsens the state of health of young people (Höld et al., 2018).

In summary, it can be stated that young people are on different journeys in their lives, and in policy making, it is essential to consider the autonomy and rights of young people when entering and choosing support services and their possible different coping strategies.

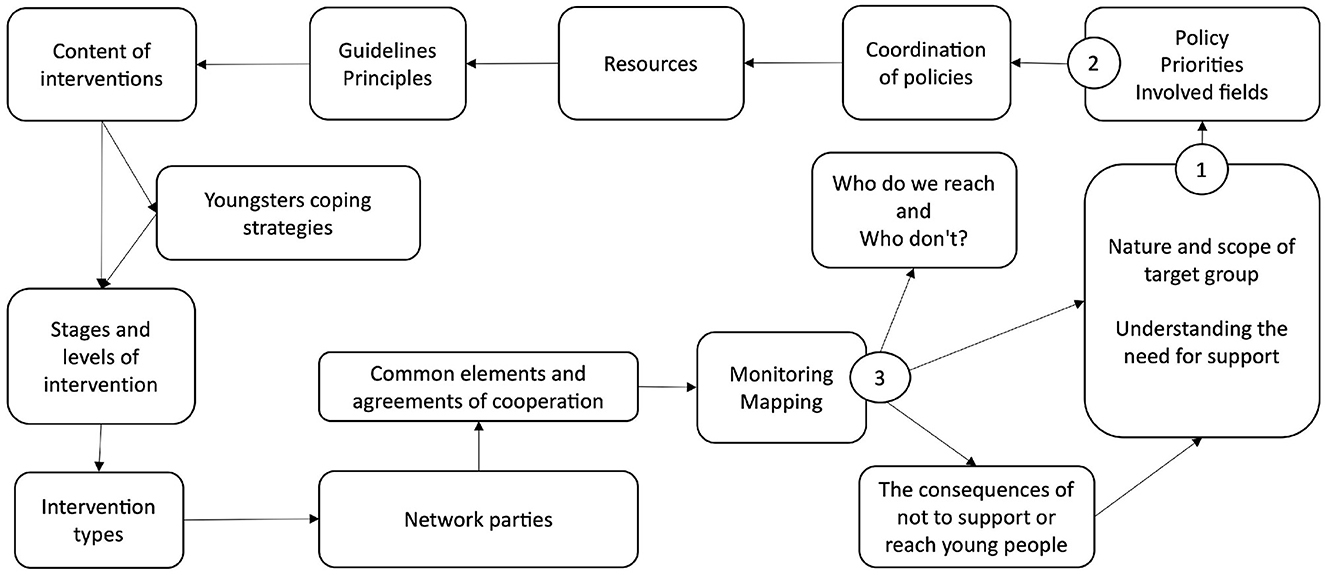

4. Discussion

There is a growing body of literature related to NEETs, and work carried out with NEETs. This study aimed to provide the first systematic overview of literature addressing NEETs and the policy and practice specific to NEET youth. We identified a broad scope of literature on NEET youth that allows going beyond their similar situation and describing the varied situations of NEET youth, nuanced by both individual situations and local and state policies targeted at this group of young people. Our systematic analysis of the literature yielded five overarching codes or focus topics we have discussed in this article: (1) “NEET” as a concept; (2) the heterogeneity of the target group; (3) the impact of structures and policies for young people; (4) possible interventions; and (5) factors influencing young people's coping strategies.

This literature review allows the research results of the categories to be placed in the context of the European Commission's policy guidelines for Member States to support its more systematic development (Figure 5).

First, studies demonstrated that in policy making, there is a need to understand the nature and scope of the target group, one aspect of which is the concept used for the target group and that it is not a homogeneous group. The EU guidelines also highlight the need to understand the target group better.

This study confirmed that the term “NEET” is a contested concept that has provoked much criticism from the researchers because of the attempt to apply a homogeneous label to a very heterogenic target group. However, our literature analyses also demonstrated the fruitfulness of the concept as the possibility to compare target groups across countries and the heterogeneity of the NEET youth. Different interventions targeted at this group of young people were rather well-covered in the literature that came up in our search.

Second, based on the nature of the target group, it is possible to perceive which fields and policies need to be involved in the systemic support of young people and which cross-sectoral coordination agreements and resources need to be concluded on the pathway to adulthood. The study highlighted the understanding that combined and cross-sectoral policies are seen based on scientific literature as one of the key factors in reaching and supporting more difficult target groups. The complex needs of the target group have to allow for the creation of cross-sectoral pathways services that are tailor-made and consider youngsters coping strategies, which assure that the young person returns to education or employment or prevents them from becoming NEET. The study also made clear that young people's opportunities in education and the labor market vary across Europe and that the uniformity of national support systems and structures should not be taken for granted, including that a similar social group in the same country but in different locations may also need different approaches. Tailored measures and services are designed to tackle not only individual needs of NEET youth, but also the specific characteristics of the local contexts.

Third, research results related to the NEET situation allow us to understand the consequences of youth deprivation and which policies will be most effective in the national context. The study leads us to the proven realization that the youth services and policy landscape is in a constant state of development. Therefore, there is a need to continuously map and monitor the existing system, which in turn creates new prerequisites for further development work to identify young people's needs further and support them more effectively. To do this, the study found that there is a need to understand which groups of young people we have reached and which we have not and whether the interventions we have put in place have been effective in supporting young people. There was hardly any research attempting to pinpoint the groups of young people who are out of reach of interventions.

In addition, we also noticed the absence of specific topics that we consider important in light of the European Commission's guidelines and that we expected to find in the literature. There were limited research papers focusing (see Figure 6) on youth co-creation, including community-based service creation, although, for service creation related to more complex target groups, the need for community level and young people as co-producers of the services is proven (Voorberg et al., 2013; Windsor, 2017; Osborne, 2018; Erdogan et al., 2021; Jonsson et al., 2022).

Figure 6. Conclusions and main and less represented thematic focuses on case management for young people having NEET-status in research.

Only a few research papers came across where this topic was the focus, but these were mostly related to countries not in Europe. This will provide further guidance for more informed service and policy-making purposes. Therefore, there is a need to explore the research about outreach, validation, skills needed to prevent or exit from the status of young people with the relevant status, the more precise roles of professionals in case management and the feasibility and potential of community involvement in the creation of services, and the impact of inclusion in the further service and support of young people.

Based on the political categories of NEETs developed by Mascherini (2019; seven different), the analysis pointed out that studies on the subcategories defined in the different categories can be partially found, while there were no studies targeting young people having NEET-status whose current situation (e.g., privileged) may lead to the understanding that they do not need support (e.g., Andrade and Järvinen, 2017; Ng-Knight and Schoon, 2017) or whose support has not been sufficient and they are directed toward the following service providers (e.g., Avila and Rose, 2019). In addition, the analysis highlighted that there is need for research that provide knowledge of the background and needs of target groups not reached through interventions, according to Cabasés Piqué et al. (2016), Hutchinson et al. (2016), and García-Fuentes (2019) is increasingly important.

Such knowledge may imply the need to consider the specificities related to the description of the situation of the young person when designing policies and interventions and to create eight categories where it is not known in which area the young person is vulnerable (risk situation) and where it can be considered that the young person may not perceive him/herself as belonging to these categories. Also, according to Furlong (2006), political debates must not be based solely on the NEETs indicator, as many other groups of young people are also in precarious and vulnerable situations. It is vital to bear in mind that for all young people, moving out of status does not have to be the goal, as it may not be a need but an opportunity to get the support they need.

Consideration of policies based on young people's needs and self-perception has been highlighted by Simmons and Thompson (2011), Cabasés Piqué et al. (2016), Hutchinson et al. (2016), Sutill (2017), Holte (2018), Maguire (2018), García-Fuentes (2019), and Bonnard et al. (2020). In addition, having a NEET-status may not be associated with negative consequences since young people have different reasons for being in this temporary status (Simmons and Thompson, 2011; Sutill, 2017), but may need a little push to move forward.

In sum, the systematic literature analysis demonstrates that further research and support for NEET-youth must be seen as inter- and multidisciplinary, which requires applying the holistic principle upon approaching young people in service and policy-making. This requires that the young person is seen as a unique person whose involvement in service creation supports the service's compliance with the actual needs of young people. As factors contributing to finding and supporting young people, it is important to consider differences within a single social group; the smoothness, stability and interaction between the different site-based policies; young people's sense of self-perception, rights and autonomy in entering and developing support services and possible coping strategies. It is essential to follow that offered services must be time and place-based, flexible and supported through multidisciplinary teams.

The literature review reveals the importance of a better understanding of the concept and characteristics of the NEETs. This better understanding of the concept will help the decision makers to develop tailored measures for various categories of NEETs that cope with the multiple vulnerabilities of these young people.

5. Limitations

The systematic literature analysis entails certain limitations; thus, it cannot be extended to cover all research on NEET-status youth. The first limitation is related to the underlying choices of the research by looking for studies during the relevant period in which conclusions were either associated with the NEET-status youth or were based on a relevant target group. Furthermore, the research is bound to specific databases and does not cover articles not indexed in the databases where we conducted our search. That may have yielded to the exclusion of some significant contributions to the field. Secondly, it is important to point out that the geographical scope of the studies found for the target group was global. However, this analysis considers research of which scope was linked to the European level. Although the results of studies from outside Europe have not been considered in the paper, it is important to note that the focus of the main topics was similar, and the results showed that support for NEET-status youth is due to similar contributing factors. Furthermore, it is also a strength of this paper that it focuses on societies functioning in the relatively similar legislative frame and European-level policy recommendations for implementation of Youth Guarantee programs. However, as Europe is rich in languages and a lot of research on NEET-status youth is done in languages other than English, it is important to acknowledge that this overview fails to pick up relevant research in other European languages. Thirdly, it is important to emphasize that the analysis aimed to get a broad overview of the variability of the conclusions of the scientific literature related to the target group. For this reason, the focus is not on highlighting the most important or priority sub-themes in each sub-topic. Fourthly, it is important to point out that the analysis and the search for connections between research papers could only be carried out based on the performed interventions and thus do not provide an overview of all the opportunities offered to NEET-status youth in Europe today.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HP contributed to conception and design of the study, organized the database, performed the first analyze, wrote first draft of manuscript, and created figures. HP and PF contributed to methodology. HP, PF, MB, and CP contributed to the completion of different parts of the final manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 870898. MB's work on this publication was supported by a grant from the Estonian Research Council (PRG700).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

References

Aasa, A. (2020). “(Suur)andmete visuaalne esitamine. [Visual representation of (big) data.],” in Kuidas mõista and mestunud maailma? Metodoloogiline teejuht, eds A. Masso, K. Tiidenberg, and A. Siibak (Tallinn: Tallinna ülikooli kirjastus).

Agranovich, M. (2020). The impact of educational indicators on success in after school life: Regional databased analysis. Sotsiologicheskoe Obozrenie 19, 188–213. doi: 10.17323/1814-9545-2020-3-188-213

Alegre, M. À., Casado, D., Sanz, J., and Todeschini, F. A. (2015). The impact of training-intensive labour market policies on labour and educational prospects of NEETs: Evidence from Catalonia (Spain). Educ. Res. 57, 151–167. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2015.1030852

Alfieri, S., Sironi, E., Marta, E., Rosina, A., and Marzana, D. (2015). Young Italian NEETs (not in employment, education, or training) and the influence of their family background. Europe's J. Psychol. 11, 311–322. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v11i2.901

Amendola, S. (2021). Trends in rates of NEET (not in education, employment, or training) subgroups among youth aged 15 to 24 in Italy, 2004–2019. J. Public Health 2021, 3. doi: 10.1007/s10389-021-01484-3

Andersson, F. W., Gullberg Brännstrom, S., and Mörtvik, R. (2018). Long-term scarring effect of neither working nor studying. Int. J. Manpower 39, 190–204. doi: 10.1108/IJM-12-2015-0226

Andrade, S. B., and Järvinen, M. (2017). More risky for some than others: negative life events among young risk-takers. Health Risk Soc. 19, 387–410. doi: 10.1080/13698575.2017.1413172

Anne, D., Chareyron, S., and L'Horty, Y. (2020b). In the army now … Evaluating an intensive training program for youth. Educ. Econ. 28, 196–210. doi: 10.1080/09645292.2019.1706075

Anne, D., Le Gallo, J., and L'Horty, Y. (2020a). Facilitating NEETs urban mobility: A controlled experiment. Revue d'Economie Politique 130, 519–544. doi: 10.3917/redp.304.0015

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Arumugam, V., Mamilla, R., and Anil, C. (2019). “NEET for medics: a guarantee of quality? An exploratory study”, Quality Assurance in Education. 27, 197–222. doi: 10.1108/QAE-07-2018-0080

Avila, T. B., and Rose, J. (2019). When nurturing is conditional: How NEET practitioners position the support they give to young people who are not in education, employment or training. Res. Post Compul. Educ. 24, 60–82. doi: 10.1080/13596748.2019.1584439

Bacher, J., Koblbauer, C., Leitgob, H., and Tamesberger, D. (2017). Small differences matter: How regional distinctions in educational and labour market policy account for heterogeneity in NEET rates. J. Labour Market Res. 17, 6. doi: 10.1186/s12651-017-0232-6

Bäckman, O., and Nilsson, A. (2016). Long-term consequences of being not in employment, education or training as a young adult. Stability and change in three Swedish birth cohorts. Eur. Societ. 18, 136–157. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2016.1153699

Bǎlan, M. (2016). Economic and social consequences triggered by the NEET youth. Knowl. Horizons-Econ. 8, 80–87.

Bania, E. V., Eckhoff, C., and Kvernmo, S. (2019). Not engaged in education, employment or training (NEET) in an Arctic sociocultural context: The NAAHS cohort study. Br. Med. J. Open 9, 23705. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023705

Barth, E., Keute, A. L., Schone, P., von Simson, K., and Steffensen, K. (2021). NEET status and early versus later skills among young adults: Evidence from linked register-PIAAC data. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 65, 140–152. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2019.1659403

Batini, F., Corallino, V., Toti, G., and Bartulucci, M. (2017). NEET: A phenomenon yet to be explored. Interchange 48, 19–37. doi: 10.1007/s10780-016-9290-x

Beck, V. (2015). Learning providers' work with NEET young people. J. Voc. Educ. Train. 67, 482–496. doi: 10.1080/13636820.2015.1086412

Berlin, M., Kääriälä, A., Lausten, M., Andersson, G., and Brännström, L. (2020). Long-term NEET among young adults with experience of out-of-home care: A comparative study of three Nordic countries. Int. J. Soc. Welfare 2020, 12463. doi: 10.1111/ijsw.12463

Blinova, T. V., and Vialshina, A. A. (2017). Youth not in the educational system and not employed. Sociol. Res. 56, 348–362. doi: 10.1080/10610154.2017.1393208

Bonanomi, A., and Luppi, F. (2020). A European mixed methods comparative study on NEETs and their perceived environmental responsibility. Sustainability 12, 201515. doi: 10.3390/su12020515

Bonnard, C., Giret, J.-F., and Kossi, Y. (2020). Risk of social exclusion and resources of young NEETs. Economie et Statistique 515–517, 133–154. doi: 10.24187/ecostat.2020.514t.2010

Bradley, S., Migali, G., and Navarro Paniagua, M. (2020). Spatial variations and clustering in the rates of youth unemployment and NEET: A comparative analysis of Italy, Spain, and the UK. J. Regional. Sci. 60, 1074–1107. doi: 10.1111/jors.12501

Buchanan, S., and Tuckerman, L. (2016). The information behaviours of disadvantaged and disengaged adolescents. J. Document. 72, 527–548. doi: 10.1108/JD-05-2015-0060

Cabasés Piqué, M. À., Pardell Veà, A., and Strecker, T. (2016). The EU youth guarantee—A critical analysis of its implementation in Spain. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 1098777. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1098777

Cajic-Seigneur, M., and Hodgson, A. (2016). Alternative educational provision in an area of deprivation in London. Lond. Rev. Educ. 14, 25–36. doi: 10.18546/LRE.14.2.03

Campbell, R., Wright, C., Hickman, M., Kipping, R.-R., Smith, M., Pouliou, T., et al. (2020). Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence is associated with substantial adverse health and social outcomes in early adulthood: Findings from a prospective birth cohort study. Prev. Med. 138, 106157. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106157

Carcillo, S., and Königs, S. (2015). NEET Youth in the Aftermath of the Crisis: Challenges and Policies. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, 164. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2573655

Caroleo, F. E., Rocca, A., Mazzocchi, P., and Quintano, C. (2020). Being NEET in Europe before and after the economic crisis: An analysis of the micro and macro determinants. Soc. Indic. Res. 149, 991–1024. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02270-6

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 1–2. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

Coates, H. (2016). Disadvantaged youth in southern Scotland experience greater barriers to information access resulting from poor technology skills, information literacy, and social structures and norms. Evid. Based Libr. Inform. Practice 11, 75–78. doi: 10.18438/B85D1T

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O'Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., et al. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Contini, D., Filandri, M., and Pacelli, L. (2019). Persistency in the NEET state: A longitudinal analysis. J. Youth Stud. 22, 959–980. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2018.1562161

Cornish, C. (2017). Case study: Level 1 Skills to Succeed (S2S) students and the gatekeeping function of GCSEs (General Certificate of Secondary Education) at an FE college. Res. Post Compul. Educ. 22, 7–21. doi: 10.1080/13596748.2016.1272076

Cornish, C. (2018). ‘Keep them students busy': ‘warehoused' or taught skills to achieve? Res. Post Compul. Educ. 23, 100–117. doi: 10.1080/13596748.2018.1420733

Crisp, R., and Powell, R. (2017). Young people and UK labour market policy: A critique of “employability” as a tool for understanding youth unemployment. Urb. Stud. 54, 1784–1807. doi: 10.1177/0042098016637567

Csoba, J., and Hermmann, P. (2017). “Losers, good guys, cool kids” the everyday lives of early school leavers. Monitor. Public Opin. 6, 295–312. doi: 10.14515/monitoring.2017.6.15

Davison, J., Share, M., Hennessy, M., and Knox, B. S. (2015). Caught in a “spiral”. Barriers to healthy eating and dietary health promotion needs from the perspective of unemployed young people and their service providers. Appetite 85, 146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.010

De Luca, G., Mazzocchi, P., Quintano, C., and Rocca, A. (2019). Italian NEETs in 2005–2016: Have the recent labour market reforms produced any effect? CESifo Econ. Stud. 65, 154–176. doi: 10.1093/cesifo/ifz004

Denyer, D., and Tranfield, D. (2009). “Producing a systematic review,” in The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, eds D. A. Buchanan, A. Bryman (Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications Ltd), 671–689.

Enrica, S. (2019). Leaving your mamma: Why so late in Italy? Rev. Econ. Household 17, 323–347. doi: 10.1007/s11150-017-9392-y

Erdogan, E., Flynn, P., Nasya, B., Paabort, H., and Lendzhova, V. (2021). NEET rural-urban ecosystems: The role of urban social innovation diffusion in supporting sustainable rural pathways to education, employment, and training. Sustainability 13, 2112053. doi: 10.3390/su132112053

European Commission (2020). Council Recommendation on a Bridge to Jobs—Reinforcing the Youth Guarantee and Replacing Council Recommendation of 22 April 2013 on Establishing a Youth Guarantee. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.C_.2020.372.01.0001.01.ENG (accessed December 20, 2022).

Eurostat (2020). Young People Neither in Employment Nor in Education and Training by Sex, Age and Labour Status (NEET Rates). Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ (accessed December 20, 2022).

Focacci, C. N. (2020). “You reap what you sow”: Do active labour market policies always increase job security? Evidence from the Youth Guarantee. Eur. J. Law Econ. 49, 373–429. doi: 10.1007/s10657-020-09654-6

Furlong, A. (2006). Not a very NEET solution: Representing problematic labour market transitions among early school leavers. Work Employ. Soc. 20, 553–569. doi: 10.1177/0950017006067001

García-Fuentes, J. (2019). The visibility of ‘NEET' young people in the Spanish economic context. Psicoperspectivas 18, 1645. doi: 10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol18-Issue3-fulltext-1645

Gaspani, F. (2019). Young adults NEET and everyday life: Time management and temporal subjectivities. Young 27, 69–88. doi: 10.1177/1103308818761424

Görlich, A., and Katznelson, N. (2018). Young people on the margins of the educational system: Following the same path differently. Educ. Res. 60, 47–61. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2017.1414621

Haikkola, L. (2021). Classed and gendered transitions in youth activation: The case of Finnish youth employment services. J. Youth Stud. 24, 250–266. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2020.1715358

Hale, D. R., and Viner, R. M. (2017). How adolescent health influences education and employment: Investigating longitudinal associations and mechanisms. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 465–470. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-209605

Hammarström, A., and Ahlgren, C. (2019). Living in the shadow of unemployment—an unhealthy life situation: A qualitative study of young people from leaving school until early adult life. BMC Public Health 19, 5. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-8005-5

Hazenberg, R., Seddon, F., and Denny, S. (2014). Investigating the outcome performance of work-integration social enterprises (Wises): Do WISEs offer ‘added value' to NEETs? Publ. Manag. Rev. 16, 876–899. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2012.759670

Hignett, A., Pahl, S., White, M. P., Jenkin, R., and Froy, M. L. (2018). Evaluation of a surfing programme designed to increase personal well-being and connectedness to the natural environment among ‘at risk' young people. J. Advent. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 18, 53–69. doi: 10.1080/14729679.2017.1326829

Höld, E., Winkler, C., Kidritsch, A., and Rust, P. (2018). Health related behavior of young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) living in Austria. Ernahrungs Umschau 65, 112–119. doi: 10.4455/eu.2018.027

Holte, B. H. (2018). Counting and meeting NEET young people: Methodology, perspective and meaning in research on marginalized youth. Young 26, 677618. doi: 10.1177/1103308816677618

Holte, B. H., Swart, I., and Hiilamo, H. (2019). The NEET concept in comparative youth research: The Nordic countries and South Africa. J. Youth Stud. 22, 256–272. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2018.1496406

Hooghe, L., and Marks, G. (2003). Unravelling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 97, 233–243. doi: 10.1017/S0003055403000649

Hudson, B., Hunter, D., and Peckham, S. (2019). Policy failure and the policy-implementation gap: Can policy support programs help? Policy Design Practice 2, 1540378. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2018.1540378

Hutchinson, J., Beck, V., and Hooley, T. (2016). Delivering NEET policy packages? A decade of NEET policy in England. J. Educ. Work 29, 707–727. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2015.1051519

Iacobuta, A. O., and Ifrim, M. (2020). Welfare mentality as a challenge to European sustainable development. What role for youth inclusion and institutions? Sustainability 12, 93549. doi: 10.3390/su12093549

Irwin, S. (2020). Young people in the middle: Pathways, prospects, policies and a new agenda for youth research. J. Youth Stud. 2020, 1792864. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2020.1792864

Jongbloed, J., and Giret, J. F. (2021). Quality of life of NEET youth in comparative perspective: Subjective well-being during the transition to adulthood. J. Youth Stud. 2020, 1869196. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2020.1869196

Jonsson, F., and Goicolea, I. (2020). “We believe in you, like really believe in you”: Initiating a realist study of (re)engagement initiatives for youth not in employment, education or training with experiences from northern Sweden. Eval. Progr. Plan. 83, 101851. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2020.101851

Jonsson, F., Gotfredsen, A. C., and Goicolea, I. (2022). How can community-based (re)engagement initiatives meet the needs of ‘NEET' young people? Findings from the theory-gleaning phase of a realist evaluation in Sweden. BMC Res Notes 15, 232. doi: 10.1186/s13104-022-06115-y

Juberg, A., and Schiøll Skjefstad, N. (2019). NEET to work?—Substance use disorder and youth unemployment in Norwegian public documents. Eur. J. Soc. Work 22, 252–263. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2018.1531829

Karyda, M. (2020). The influence of neighbourhood crime on young people becoming not in education, employment or training. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 41, 393–409. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2019.1707064

Karyda, M., and Jenkins, A. (2018). Disadvantaged neighbourhoods and young people not in education, employment or training at the ages of 18 to 19 in England. J. Educ. Work 31, 307–319. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2018.1475725

Katznelson, N. (2017). Rethinking motivational challenges amongst young adults on the margin. J. Youth Stud. 20, 622–639. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2016.1254168

Kelly, E., McGuinness, S., O'Connell, P. J., Haugh, D., and Gonzalez Pandiella, A. (2015). Impact of the Great Recession on unemployed youth and NEET individuals. ESRI Res. Bullet. 6, 4. doi: 10.1016/j.ecosys.2014.06.004

Kevelson, M. J. C., Marconi, G., Millett, C. M., and Zhelyazkova, N. (2020). College educated yet disconnected: Exploring disconnection from education and employment in OECD countries, with a comparative focus on the U.S. ETS Res. Rep. Ser. 2020, 12305. doi: 10.1002/ets2.12305

Kolouh-Soderlund, L. (2013). 10 Reasons for Dropping-Out. Sweden: Nordic Welfare Centre. Nordic Centre for Welfare and Social Issues.

Laganà, F., Chevillard, J., and Gauthier, J. A. (2014). Socio-economic background and early post-compulsory education pathways: A comparison between natives and second-generation immigrants in Switzerland. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 30, 18–34. doi: 10.1093/esr/jct019

Lambert, S., Maylor, U., and Coughlin, A. (2015). Raising of the participation age in the UK: The dichotomy between full participation and institutional accountability. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 9, 359–377. doi: 10.1504/IJMIE.2015.070127

Luthra, R. (2019). Young adults with intellectual disability who are not in employment, education, or daily activities: Family situation and its relation to occupational status. Cogent. Soc. Sci. 5, 1622484. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2019.1622484

Luthra, R., Högdin, S., Westberg, N., and Tideman, M. (2018). After upper secondary school: Young adults with intellectual disability not involved in employment, education or daily activity in Sweden. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 20, 50–61. doi: 10.16993/sjdr.43

Maguire, S. (2010). ‘I just want a job' – what do we really know about young people in jobs without training? J. Youth Stud. 13, 317–333. doi: 10.1080/13676260903447551

Maguire, S. (2015). NEET, unemployed, inactive or unknown—Why does it matter? Educ. Res. 57, 121–132. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2015.1030850

Maguire, S. (2018). Who cares? Exploring economic inactivity among young women in the NEET group across England. J. Educ. Work 31, 660–675. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2019.1572107

Maguire, S. (2020). One step forward and two steps back? The UK's policy response to youth unemployment. J. Educ. Work 33, 515–521. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2020.1852508

Manhica, H., Berg, L., Almquist, Y. B., Rostila, M., and Hjern, A. (2019). Labour market participation among young refugees in Sweden and the potential of education: A national cohort study. J. Youth Studies 22, 533–550. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2018.1521952

Maraj, A., Mustafa, S., Joober, R., Malla, A., Shah, J. L., and Iyer, S. N. (2019). Caught in the “NEET trap”: The intersection between vocational inactivity and disengagement from an early intervention service for psychosis. Psychiatr. Serv. 70, 302–308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800319

Mascherini, M. (2019). Origins and future of the concept of NEETs in the European Policy Agenda. Youth Labor Transit. 17, 503–529. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190864798.003.0017

Mascherini, M., Salvatore, L., Meierkord, A., and Jungblut, J. M. (2012). NEETs, 1st Edn. (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union), 5–32.

Mawn, L., Oliver, E. J., Akhter, N., Bambra, C. L., Torgerson, C., Bridle, C., et al. (2017). Are we failing young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of re-engagement interventions. Systemat. Rev. 6, 2. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0394-2

Mayring, P. (2004). Qualitative Content Analysis. A Companion to Qualitative Research, SAGE Publications Ltd. 159–176.

Miller, J., McAuliffe, L., Riaz, N., and Deuchar, R. (2015). Exploring youths' perceptions of the hidden practice of youth work in increasing social capital with young people considered NEET in Scotland. J. Youth Studes. 18, 468–484. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2014.992311

Moreno-Colom, S., Trinidad, A., Alcaraz, N., and Borras Catala, V. (2020). Neither studying nor working: Free time as a solution? J. Youth Stud. 2020, 1784857. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2020.1784857

Ng-Knight, T., and Schoon, I. (2017). Can locus of control compensate for socioeconomic adversity in the transition from school to work? J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 2114–2128. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0720-6

Nielsen, M. L., Grytnes, R., Gorlich, A., and Dyreborg, J. (2017). Without a safety net: Precarization among young Danish employees. Nordic J. Work. Life Stud. 7, 3–22. doi: 10.18291/njwls.v7i3.97094

Nordenmark, M., Gillander Gådin, K., Selander, J., Sjödin, J., and Sellström, E. (2015). Self-rated health among young Europeans not in employment, education or training—with a focus on the conventionally unemployed and the disengaged. Soc. Health Vulnerabil. 6, 25824. doi: 10.3402/vgi.v6.25824

Novkovska, B. (2017). Severity of the issue of excluded young people in Macedonia from education, trainings and employment: How to cope with? UTMS J. Econ. 8, 295–306.

Osborne, P. S. (2018). From public service-dominant logic to public service logic: Are public service organizations capable of co-production and value co-creation? Publ. Manag. Rev. 20, 225–231. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1350461

Ose, S. O., and Jensen, C. (2017). Youth outside the labour force—Perceived barriers by service providers and service users: A mixed method approach. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 81, 148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.002

Paabort, H., and Beilmann, M. (2021). State level agreed-upon factors contributing more effective policymaking for public sector services for effective local-level work with NEETs. Revista Calitatea Vieţii 32, 398–420. doi: 10.46841/RCV.2021.04.04

Parola, A., and Felaco, C. (2020). A narrative investigation into the meaning and experience of career destabilization in Italian NEET. Mediterranean J. Clin. Psychol. 8. doi: 10.6092/2282-1619/mjcp-2421

Petrescu, C., Elena, A. M., Fernandes-Jesus, M., and Marta, E. (2022). Using evidence in policies addressing rural NEETs: Common patterns and differences in various EU countries. Youth Soc. 54, 69–88. doi: 10.1177/0044118X211056361

Pinto Pereira, S. M., Li, L., and Power, C. (2017). Child maltreatment and adult living standards at 50 years. Pediatrics 139, 1595. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1595

Pitkänen, J., Remes, H., Moustgaard, H., and Martikainen, P. (2021). Parental socioeconomic resources and adverse childhood experiences as predictors of not in education, employment, or training: A Finnish register-based longitudinal study. J. Youth Stud. 24, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2019.1679745