- The Young Foundation, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: This paper reports the findings of research activity carried out as part of the UPLIFT project in Corby, United Kingdom. The project aimed to understand young people's experiences of education, employment and housing, and determine how young people navigate these domains, make choices and develop strategies within what is available to them. Through understanding the opportunities and strategies that young people employ across these domains, our aim was to consider how young people might engage locally to co-create a reflexive policy agenda.

Methods: We worked with peer researchers in Corby and interviewed local people (n = 40) and policy makers (n = 7) about the local context in Corby, and analyzed data, exploring themes.

Results: Findings highlighted the importance of young people understanding how systems work locally and suggest that young people, and their families, need greater support understanding how they can engage with and change systems.

Discussion: There needs to be better, easily accessible guidance developed around the support and opportunities that are available locally. Our research underlines the need to engage with young people in policy making to develop effective robust policy that works in a real-world context.

Introduction

This research was carried out as part of the UPLIFT project1 in Corby, United Kingdom. It aimed to understand the factors that influence young people's decisions in education, employment and housing, and consider how young people create their own strategies and make choices within the possibilities available in their given locality.

Our research was informed by the capability approach, which was pioneered by the economist and philosopher Amartya Sen in the 1980s (1980, 1984, 1985a, 1985b, 1987, 1990b, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1999a). The capability approach can be seen as a broad normative framework that concentrates on seeing development as an expansion of people's capabilities, the approach evaluates social phenomena such as poverty, inequality or wellbeing and provides a tool and a framework to conceptualize and evaluate these phenomena rather than explaining it.

Sen suggests that individuals ideally choose from real opportunities based on what they value or desire. He outlines the importance of capabilities and functionings. Capabilities are defined as the “real freedoms to lead the kind of life people have reason to value” (Sen, 1999) while functionings can be defined as the “various things a person may value being or doing” (Kimhur, 2020, p. 4). Examples of functionings include: being nourished, being employed, having children, being healthy, being happy, being well-housed, having self-respect and being able to take part in the life of the community (Sen, 1999, p. 75). Capabilities and functionings are closely linked. Functionings show what people actually are (beings) or do (doings), whereas capabilities refer to the ability to achieve these beings or doings. The capabilities that people enjoy are strongly dependent on both individual and contextual (structural) factors.

Within the capability approach the starting point for understanding how people navigate the challenges they might face and the choices they have to make is to define their resource base. The resource base is a complex socio-economic environment around individuals, consisting of all formal rights (e.g., laws and legislations) and possibilities (e.g., subsidy schemes, programmes against social inequalities), this base defines the opportunities that a person can engage with. The routes from this resource base to real and meaningful opportunities are paved by conversion factors. These are the different capabilities to convert public policies and formal rights into valuable opportunities (Kimhur, 2020). Certain conversion factors enable some elements of the opportunity space to be made visible and usable, while other factors have the ability to conceal the real opportunity space, resulting in a gap between the real and perceived opportunity space, and a distorted decision about chosen functionings.

Conversion factors can be viewed at different levels. Individual conversion factors (micro level conversion factors) focus on a person's psycho-social capabilities, such as individual character, things they value and their social network. Family conversion factors (also a micro level conversion factor) focus on an individual's family background, including where they were brought up, their family's educational/employment background, values, believes and attitudes in the family. Institutional conversion factors (meso-level conversion factors) focus on attitudes and behaviors oat an institutional level. Institutional conversion factors impact on people's lives in different ways.

In recent years, the capability approach has been used in several fields of both research and policymaking; in social and health policy for youth and children, with participatory processes and action research (Hart and Brando, 2018; Shearn et al., 2021), in social innovation and management work (Howaldt and Schwarz, 2017; Batista and Correia, 2021) and the field of education (Walker and Unterhalter, 2007).

The research this paper focuses on took place in Corby, which is a town in North Northamptonshire in England. As of mid-2019 Corby had an estimated population size of 72,218, of which 16.8% (12,114 people) were young people aged 15–29 years old. Over the last century, the town has experienced multiple periods of substantial social and economic transition. The opening of its first steel works in 1934 initiated its urbanization. In 1950, Corby was designated for development under the 1946 New Towns Act to help re-construct Britain's communities. Through the 1980s, deindustrialisation led to mass unemployment and economic hardship. Currently, the town's economy centers around manufacturing and distribution. In 2019, 23.5% of Corby's jobs were in wholesale and retail trade, 20.6% in the manufacturing industry and 14.7% in transportation and storage. Over recent years, money has been invested to support Corby's regeneration which included a new train station in 2009 with rail links to London, as well as the £32m “Corby Cube” (a civic center boasting a 450-seat theater, public library, and a new council chamber) and a £20 m Olympic-sized swimming pool which opened in 2010.

With an average Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score of 25.7, Corby ranked among the most deprived quartile of English local authority district areas in 2019 (76 out of 317). Until recently, local governance in Corby were split between two councils: a larger “county council” (Northamptonshire), responsible for strategic services and a smaller “district council” within this (Corby Borough), responsible for more place-related services. On 1st April 2021 Corby Borough Council merged with three other local district councils to form a new “unitary council”: North Northamptonshire Council.

The main research questions we explored in this research were:

1. What are the different factors that support young people to live the life they would like to live or they should be able to live taking into account the possibilities their locality offers for them?

2. What are the factors that could be changed locally through engaging in a Reflexive Policy Agenda?

These two questions served as a guide for the research, as we aimed to explore the factors that related to young people's general experiences of housing, education and employment in Corby.

In this paper we outline the community centered approach that underpinned our research process. We then present our findings as three storylines. These storylines focus on the conversion factors that were identified as supporting people to meet their potential. We explore factors related to the domains of education, employment, and housing. In the discussion section we then consider the challenges identified by young people in their resource base across domains and reflect on the key aspects that impacted across young people's experience. The paper then focuses on the more practical and structural changes that could be made through a reflexive policy agenda.

Materials and methods

Recruitment

We carried out seven interviews with policy experts in Corby between February and March 2022, experts worked in education, employment, and housing in community organizations and for the council. Interviews lasted ~60–90 min and were recorded as operational notes.

We then carried out 40 life course interviews with people aged 15–42 years old; half the participants were aged between 15 and 29 years old and the other half 30–42 years old. The older group were included as we were interested in exploring experiences across an extended period. This older age group were asked to reflect back on their experiences when younger and consider how these experiences had impacted throughout their lives so far. This allowed a slightly longer-term reflexivity from participants and allowed the research team to consider whether experiences were part of a longer-term pattern locally. Other criteria for interviewees included (a) a household income of under £16k currently or at a point in their life when they were a young person (the Office of National Statistics report that the UK median household income is £31,400, a household earning < 60% of this figure is considered a low-income household) and (b) living within Corby itself.

To ensure interview participants were representative of the transforming demograp hics of Corby, specifically due to recent migration, a knowledge-seeking and partnership approach was adopted to the process of recruitment. The research team took steps to gain a detailed understanding of the neighborhoods that made up Corby and the living spaces and communities within these. A zonal map for recruitment was created, highlighting the postcode region and specific areas and estates within the Corby town. Other social variables to guide recruitment included income, periods of unemployment, experiences of barriers to housing and services and health needs. We took a purposeful approach to sampling to ensure that there was balanced representation across gender, ethnicity and learning needs, as well as a range of education, employment, and health experiences.

During the interview process we employed peer researchers, to support a participatory approach. Peer research involves including people with lived experience of the issues being studied in directing and conducting the research. Three peer researchers from Corby, between the ages of 19 and 24 years old, were recruited to support research process and carry out life course interviews. Peer researchers received training in research methods, ethics and interview skills and were supported throughout the process by The Young Foundation.

Interviewees were recruited with the support of local organizations, including the local Jobcentre (government-funded employment agency). The research team also attended a range of community events including a family fun day and community group sessions including arts and drama clubs, gardening for wellness and music rehearsals. The team based themselves in local community cafes and advertised the research project online, with community groups on Facebook, and talked about the project on the local radio. We adopted a snowball approach and through this were able to reach into communities and talk to people who had never taken part in research before.

Most interviews took place face to face in community centers, the library and community cafes. Around 40% of interviews took place by phone and zoom. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed.

Interviewees

Our final sample consisted of 17 males and 23 females, 65% of whom were born in Corby. Half the cohort were aged in the younger category of 15–29 years, the latter aged between 30 to 42 years old. 12.5% were of migrant backgrounds and 30% reported long term health difficulties. Seventy percent of respondents reported living in rented accommodation or with family, with 45% of these interviewees living in what can be described as “insecure” housing, due to high costs, unstable contracts, and overcrowding. Homeowners made up 30% of our participants.

Participants generally attended their local school at primary and secondary level. Six participants had completed their education to degree level and a further two participants were currently completing a degree as mature students.

Almost 60% of our sample were unemployed, and of those employed, many described their employment as insecure, for example working on zero-hour contracts (casual contracts that offer no guarantee of work) or cash-in-hand, highly insecure employment.

Analysis

Once interviews were complete, the research team reviewed the data and shared initial findings with the community in Corby. In July 2022 we held a Storytelling Workshop in a town center community art space. The aim of the workshop was to share and discuss preliminary findings from the interview process with young people and the community generally. We invited a range of people, including people working across the local community, those involved with interviews, as well as an open invitation to the public through advertising on local radio. We presented initial findings and storylines from the life course interviews and attendees were asked to share their views and experiences anonymously on postcards.

Following this, interview transcripts were reviewed in detail by members of the research team and quotes from the interviews, and notes on their context, were entered into the analytical tool, which was an excel sheet mapped onto the main factors within Sen's Capability Approach. Using this tool enabled us to focus on purposefully analyzing our data in reference to the capability approach by mapping out the data and evaluating the three main factors of Sen's capability approach. We explored each individual's resource space, the choices available (functionings) and opportunities (capabilities) in the area of Education, Housing, and Employment identifying different conversion factors such as family, individual, institution and other complex socio-economic environment around individuals (schemes, social benefits, and other policies designed to tackle social inequalities).

The research team met regularly to review this process and discuss which data to include as well as identifying and examining emerging insights. Once this process was complete, the research team reviewed the data in the analytical tool and started to consider the themes arising from the data. We held an analysis session and as a team we discussed the domains of Housing, Education and Employment and focused on the choices, capability and conversion factors identified in the analytical tool. We explored areas of similarity and difference within and across different age groups and discussed how the interviews with policy experts and individuals living in Corby mapped onto one another.

This process identified five possible themes to explore further in the data. These themes were reviewed carefully, we collaborated using Miro Boards, and each potential theme was described in detail with quotes from the data that illustrated the theme itself, how it impacted on people's experiences and then specifically the resource space identified, and the conversion factors were added to each board.

Through this exercise we merged several of the themes and developed three main storylines. Each storyline identified the resources that interviewees discussed, i.e., that which they could access, then identified the gap between the resources available and their ambition. In each case we asked ourselves “what creates this gap?” and “what is needed to bridge the gap?” discussing the data and our conclusions. This allowed us to identify the conversion factors that could or did close the gap. All storylines were reviewed by four research team members drawing on inter-rater reliability to develop robust qualitative analysis.

Results

Our findings focus on the gap between where people are and where they want to be and identify the conversion factors that supported or would support people to meet their potential. The storylines discussed below focus on the gaps between the current situation and people's desired outcomes. To preserve anonymity interviewees names are not provided, rather the quotes in the following sections are attributed to the interviewees gender identification; M (Male), F (Female), or NB (Non-Binary), and age.

Storyline 1: if individual needs are not met by schools there is a long-lasting impact

The importance of individual educational and health needs being recognized and met in school was mentioned across the interviews by interviewees of all ages. This was discussed in reference to physical and mental health as well as specific additional educational needs. The term additional educational need refers to people who for a variety of reasons may face barriers to education and learning. These barriers make it more difficult for them to reach their full potential. Examples from our participants included young people with a diagnosis of dyslexia, autism and hearing loss.

Most interviewees with additional needs reported that their individual needs were not well met in the local education system, this was a similar experience across different age groups, although a few people in the older group felt that there was probably better understanding and awareness of additional needs now. One interviewee explained that:

“You were left to your own devices a bit really…I've got friends who are teachers and things like that, you can tell children who have potential and you need to hone them and lead them in the right direction but I don't think back then in schools of that sort of quality, that was happening.” (M 37)

Many interviewees felt they were ignored as their needs were seen as minor or manageable. Teachers were seen to be busy supporting those with more extreme behavioral difficulties in the classroom:

“I feel like they just feel like if you're not really, really severe with alarming difficulty, you're just there.” (M 16).

Some interviewees reflected that there was more support for learning and educational needs as academic achievement was valued, whereas issues around mental health were “swept under the carpet” and ignored:

“I would say that there was a lot of academic support and teachers that do care about our academic achievement within GCSEs while they have the responsibility over us…but there is somewhat of an ignorance…of mental health issues. Also, they do not have a proper behavioral system in place, it's chaotic. It's quite chaotic.” (M 15)

A lack of recognition and late diagnosis of additional needs and mental health conditions was identified as a particular challenge at school and life beyond for several interviewees. Interviewees felt that there was limited training around additional needs and minimal access to mental health support:

“Obviously, with school, I had absolutely no support or whatsoever with any of that, or with any of the other mental health conditions that I was dealing with…I feel that they didn't have the training. I think it was quite apparent that I was suffering, but I don't think the training was there…I suffered quite a lot of mental health when I was in school, which I didn't know who I could speak to. I wasn't speaking to mum at home, obviously, because she was dealing with so much as well. It wasn't until I was pregnant when I was 28 that a psychologist actually said to me I had ADHD. That was the first time that anyone recognized anything.” (F 30)

Another interviewee explained that his hearing impairment went undiagnosed throughout primary school, into secondary school:

“I wasn't like the best kid, but I'm deaf in one of my ears, and nobody knew that and I didn't know that for some years because everybody wouldn't test it because they thought I was just hyperactive and not listening and stuff. Once they found out and I had helpers with me, that explained stuff to me, because I couldn't hear over other people, I was a lot better.” (M 30)

Others explained that even once they had been diagnosed, their needs were not always acknowledged by teachers, and they experienced little to no differentiation or additional support to access learning. Some felt their needs were poorly understood and this led to a lack of support and understanding of their emotional and behavioral needs:

“The teaching assistants thought that I was just a bad kid when I was having a lot of sensory issues or struggling to emotionally regulate, or a routine threw me off or I was very, very blunt and I just didn't understand what was going on. I used to get punished a lot and I used to get berated…a lot of teachers when they found out that I was autistic would say things like I was never going to amount to anything and that I was useless and I was a waste of space and I'd be living on my parents' sofa for the rest of my life…a lot of these teachers and teaching assistants they used to deny me the accommodations I needed in order to feel safe and be able to work in that environment.” (NB 21)

When asked what support was needed, or would have made a difference, the interviewees prioritized; acknowledgment and acceptance, additional in-class support, differentiation of resources, flexibility within the system and support to access and engage with core lessons:

“Definitely extra support during lessons. One would be having extra English, extra maths lessons. Say I was to drop the GCSE, and that would give me x amount of lessons free during the week to do extra English, extra maths, extra science.” (M 16)

It is important to recognize that a few interviewees were happy with the support they had received throughout school and this high-quality support and provision was highly valued:

“Yes, there like at my junior school, specifically, there was like a DSP {Designated Specialist Provision} unit. I don't know if that's correct term now, but yes…It was never really a disruption on our education or whatever. There was usually an LSA {Learning Support Assistant Teacher} that would sit with them and stuff like that.” (M 27)

Another particularly positive area of support for one interviewee related to English language support. Schools in Corby have been supported by the council to prepare and cater for the needs of Eastern European migration, mainly from Poland, through additional funding. The ambitious 2003 Catalyst Corby plan, set out to address the town's structural problems by increasing the towns' population. Hence, the foreign-born population of the town has grown substantially, more than doubling in size since 2004 and making up approximately one-fifth of Corby's total population. Schools now offer additional “English as a foreign language” lessons for children who may need extra language support.

“It was obviously hard when I first came here because I was struggling with English, but after that, it was really good. I really enjoyed going to school in here…yes, I would, even though we had the Polish teacher, which was a lot of support for us, all the English teacher would still support us. Even in the case that I couldn't speak to her, I could speak with other teachers. There was a lot of support in schoolwork.” (F 23)

Interviewees explained that the way in which their additional needs were met, or often not met, whilst at school had long-term consequences across their lives in terms of capabilities for employment and financial security.

Positive experiences of support at school were linked to having a teacher or educational professional advocate on the individual's behalf, or more often, parents having knowledge of the education system and advocating strongly for their child. Parents' knowledge and awareness of a child's support needs and understanding of how the educational, and sometimes health and social care systems work was essential. Understanding the systems, knowing how to navigate them, and more generally having what might be referred to as “social capital” including social networks and connections to draw on as a resource to help navigate life was clearly a principal factor in experiences of school and life beyond, whether this was further/higher education or employment.

As one interviewee explained:

“{Mum} was really good at finding things that you were entitled to and get in in what you could get because I suppose a lot of people maybe didn't know, you could get a bursary to go there because it was about three or four grand a term and we didn't have to pay any of it. She was just really good at that stuff… I was quite lucky. I got placed at private school for secondary school, which my mum got for me… and I got a bursary for a private school in Northampton…I think my mom just really pushed me to go.” (F 37)

Several interviewees reported similar experiences, noting that they felt they were overlooked (rather than ignored) unless their parents became involved and demanded support:

“They'll help if you really, really have a problem and if your parents are really getting annoyed with the school, they might give you a hand a bit” (M 16)

We found a significant difference between the actual policy landscape in education and the experiences that interviewees reflected on. While there are national and local policies addressing the support of young people with additional needs, and access to mental health support, they are not always met in practice.

In this area, successful conversion factors related to having a mechanism (or often person) to hold people accountable and ensure policy is adhered to. Institutional support was highly variable, often ineffective, without a strong individual who could ensure support was provided. Families needed to have, or in some instances gain, a strong understanding of the system and resource base. This did not seem to link to levels of education or previous experience but rather from an overwhelming need to advocate for one's child.

Storyline 2: perceptions of local employment opportunities differ across ages

Most employment opportunities in Corby were described as low-skilled, including for instance roles in agriculture, manufacturing, and construction, and in service sectors, such as wholesale, retail and restaurants. Many younger interviewees saw these as poor local work opportunities, in terms of money, contracts, and conditions. Zero-hour and precarious contracts, low pay and shift work were discussed as difficult to manage, specifically in relation to the rising cost of living and childcare responsibilities impacting housing and family life.

However, interviewees over 30 had quite different perceptions of local employment opportunities and suggested there was a value in starting out with an employer locally and working your way up within a company, taking advantage of in-work training. This group of interviewees reflected that starting in a company and then being inside the system had provided an opportunity to understand their capabilities and to communicate their needs and ambitions to employers as well as receive structural support, mentoring and training. Younger interviewees did not necessarily see this opportunity within the resource base, and their perception of the job market was highly negative.

When asked what employment opportunities were available, one woman (aged 24) told us that: “Unless you want to work in a warehouse, nothing.”

Another younger interviewee reflected that:

“I think Corby's got not the best variety of jobs. You work in retail, or you work as like a waitress or something like that…there's not many options I don't think for young people. Most of the work in Corby is factory work. If you can't do factory work, then you're stuck doing waiting and retail. It sucks.” (M 17)

This landscape was well+recognized by interviewees of all ages:

“To be honest, it's mostly warehouse and retail work in Corby. There's not much else because the service industry has hit a stalemate, well it's stagnated. There was a point a few years back where we were getting all of these new restaurants and fast-food places and it's kinda stalled really. They've opened up new McDonald's and Pizza Hut but there hasn't been anything new in town in the service industry for a good while.” (M 26).

The 2003 urban regeneration plan did generate new development in Corby, such as the redevelopment of the town center, including the £40 million Willow Place and civic spaces including the Corby Cube leading to an increase in retail, leisure, and community venues, such as new restaurants. This, as noted by interviewees, did diversify the job market. However, insecure work and conditions seemingly to prevail. One interviewee told us:

“There's a lot of agency work with just temporary factory work. It's a lot of industry work, like the steel, a lot of retail. Don't really know to be honest around the rest of it. I guess there's few hotels, I guess, hospitality and that sort of thing.” (M 40)

When asked about their current employment situation some interviewees, particularly younger interviewees, talked about the challenges of zero-hour contracts, unstable employment contracts and the difficulty of constantly looking for new work. Interviewees reported that they had concluded that many jobs were simply not long-term career options or permanent, and they would have to find a way to manage.

In addition to compromising on the type of work they wanted to do, many younger interviewees also talked about the challenges of low pay and having to work several different jobs:

“If I was just with this one job, I probably could not, I would be struggling the whole time…It's probably getting the job that I like, basically, because there are a lot of jobs but it's like you can go there and make money but when you want to progress and do something with yourself, it's hard to find somewhere around Corby, if that makes sense, for people with no experience, let's say.” (M 24)

However, while younger interviewees saw the job market and employment practices as problematic those over 30 were more likely to see the problem as the way in which young people approached work:

“I think it's the competitive rates thing. Just literally just people asking for more money and just hop into another job and then vice-versa.” (M 30)

This view was also supported at the story telling workshop in Corby, where one attendee stated, “make people work, there are a lot of jobs in Corby” (M). He talked about the difficulties of work and housing conditions when his father arrived to work in the steelworks in the 1950s and compared these to the diverse opportunities available now.

A few younger interviewees didn't seem to mind the lack of permanence in the labor market and were happy to move jobs as they viewed low skills factory work as a short-term option or an entry point into the world of work:

“To be honest with you, I don't think factory work's too bad if you're not staying in it your whole life. It's really good pay and you've got-something to keep you on your feet.” (M 16)

Indeed, for some, the availability of unskilled or low skilled jobs was attractive and seen as a way of gaining initial employment. Some interviewees who had emigrated to the UK with English as a second language reported that there was a benefit in finding employment opportunities that did not require an initial high level of English:

“Well, first time when I came here, I started working on food factory. I working like warehouse colleagues, just packing on the line. That was easy, simple job. Don't need to speak English, don't need lots of things because the people around always I feel like the people help me. I don't know why, I always feel like everybody supports here.” (F 42)

The interviewee went on to explain that she had the opportunity to develop and build a career:

“I was working like a line operator. I working like a picker packer. There was a lot of experience. After I found my job, now where I am, five years now. Before, I was start from the floor, building the pallet, wrapping the pallet. Step by step, I was start with task leader. After, I was admin on the line and I wish we'll be good position on team leader soon. That means step by step. Here on England, you not have somebody stop you. Even if you not have full education, you can step by step follow the up from the beginning. I think my education has nothing to do here now.” (F 42)

In general, interviewees aged over 30 talked more about having had good opportunities with local employers to start at an entry level and progress within the organization. They described being employed on secure contracts and were supported through career progression, training on the job and general positive “mentoring” from employers/individual managers:

“I started working on that in November, and I was a contractor, so I was paid on day rate, and it was just a stop-gap gig for me. Within a week, I've just adored working for {them} and the people I was working with, and they're fantastic. The opportunity came up with the staff this year to go permanent, so I applied for that and it was obviously successful, which I am ecstatic about. I think it's a fantastic place to work and obviously, it gives me the stability I need to move, which I'm doing now, and to keep a roof over my daughter's head, which is fantastic.” (F 37)

The importance of having key individuals such as an employer, teacher or parent who had the time to understand your needs and advocate and provide guidance was recognized as the key conversion factor to career enhancement by several interviewees. One interviewee described how her boss had been influential across her life:

“Yes, I do feel appreciated. I've known my boss for about 25 years. She used to run the Youth Club that I used to go to, when I was young.” (F 34)

Strong support from employers was discussed by many interviewees. Support included gaining experience, career progression and educational support. Examples were provided by two interviewees as detailed below. Both of these interviewees were given the opportunity to complete education funded by their employers.

“I have a couple of project management qualifications. I did Prince2, which is really standard project management qualification in 2015. I did another one called P30 in 2020 or 2019. My learning and development now will all be practice based in what I do, projects and programs, risk management, that kind of thing. They're a bit part of the course for what I do, every five years you're expected to go off and redo it just to make sure you're still keeping up with knowledge. A lot of it on the application within the current place I worked in. If it's not used where I'm working now and the NHS, obviously funding is a big topic. We do have funding for training and development.” (F 37)

“I always had an interest in advertising and marketing, and so I just set up a route into a good stable company that could provide me with experience that I needed to get where I wanted to be. Then took that year out and then came back and I've dabbled in different industries from electronics, to media publishing, and now in insurance, so really different variety of industries. Luckily, I found the company that I'm in now who are just fantastic at development and really investing in their employees. I would say that I'm happy with where I've got to in my career, whether or not it's something that it will be a lifelong career. If I take a change, I really don't know.” (F 32)

It would obviously be difficult for younger interviewees to reflect on long term support and development opportunities from employers, as most would not yet have received the opportunity to progress and reflect back in this way. However younger interviewees did often identify family support and encouragement as key conversion factors to finding appropriate work, one 24-year-old explained that her mother had helped her find work experience and helped her search for jobs:

“This is my sixth year with the department. I started at 19. I did various retail jobs leading up to that. As I left college, before I finished my levels, my mother was very much, you'll get a job or you'll be down to the job center and we'll force one upon you. {I} basically just kept applying until I found something that was full-time. The job that was full-time that took me on was the Department for Work and Pensions. That's what I do.” (F 24)

Opportunities for higher skilled work were described as limited locally. Interviewees were often employed in positions for which they felt they were overqualified and had accepted lower paid work than they had initially hoped for.

Some interviewees had further and higher educational qualifications, and many of these individuals reported that higher skilled graduate roles were limited in Corby. Younger interviewees talked about moving away for higher education and better employment opportunities and then not returning to Corby.

“I think Corby is pretty much low market. There isn't the higher pays job, there isn't the progression that there are in cities and bigger towns, its more factory production roles, which works for some people I think. I think a lot of people I know that have gone on to get their degrees either have moved away from Coby or have worked outside of Corby since they have that better job.” (M 32)

“No, I would not want to stay in Corby. I don't feel like there's enough availabilities in Corby relating to either education and mainly humanities, if I'm being honest. Well, I don't think so. Obviously, in the future, they could work on getting a university in place with hopefully a good educational that could provide us with good academic development et cetera, but in terms of at the moment or in the next, let's say, 10 years, I don't believe that there's anything they could do to make me stay here.” (M 15)

Across the interviews, interviewees discussed the challenges of Corby's geography. Corby is a town in North Northamptonshire, located in the heart of England and its access to good road transport links are strategic assets for its economic development. These have been harnessed by its growing warehousing, distribution, and logistics sectors. Corby can be viewed as a “commuter town.” It has strong transport links to many major cities, with access to a range of jobs, including higher paid and higher skilled opportunities. Many interviewees talked about people from London moving to Corby due to its accessibility and lower housing costs than many other parts of the country. This group are likely to commute out of Corby for work or work from home.

Corby is a rapidly growing town, with a developing economy, the rail service has contributed to its improved connectivity. This has led to more people moving from London due to its attractive lower priced housing. However, the young people we interviewed in Corby did not see the converse, i.e., travel outside of the area for employment, as a possibility, this included those who reflected on the lack of higher skilled jobs locally. There seemed to be a disconnect between the possibilities that connectivity bought and its challenges. For some this was explained by gentrification and changes to the area:

“I found that Corby being slowly but surely gentrified from the working-class town that it was. We have a lot of people moving up from London, buying property and commuting.” (F 24)

“To be honest with you. It's a working-class town. It is what it is, although it's quite good in the sense that, because we've got a main line direct to London, you can get to London in 45 minutes.” (F 37)

Interviewees also talked about how public transportation within Corby does not meet the needs of all residents, particularly those working on the outskirts of the town and people with mobility problems.

“Not everyone can afford taxis or buses all the time. He hasn't got a bus pass, so transport is a big barrier in this town if you ain't got a car.” (F 42)

“I don't agree with what they've just done (the council). They've put the bus fares up, that's ridiculous. People aren't getting the bus.” (M 17)

There appeared to be a gap between the opportunities that exist for employment (both in Corby and through commuting) and the opportunities interviewees were aware of or considered as possibilities. Interviewees did not generally identify traveling for work outside of Corby as an option. Those who were seeking skilled work or employment in sectors that were not represented in Corby, did not see commuting as viable, although clearly people moving to Corby did. This disconnect, and the different expectations regarding travel for employment, may be linked to the relatively recent addition of the strong railway link to London in 2009. While some towns and cities in the UK have strong histories of being commuter areas, and young people see parents and others in their community automatically working, and looking for work, across a large geographical area, this has not been the case in Corby.

New strategies need to be developed to support the changing landscape in Corby. We identified two key successful conversion factors across our data first around guidance and support in navigating employment opportunities and the second related to looking for work across a wider resource base.

First, young people seem to need guidance and support to help them understand and navigate local employment opportunities, including introducing the awareness of the possibility to work one's way up within a company or institution. Very few younger interviewees saw this as part of their resource base, although those who did recognized its value as a conversion factor.

Second, young people looking for skilled work or careers for which they had trained at university could consider the possibility of living in Corby and commuting. The resource base that young people have to draw on is potentially geographically much larger than they realize or envision. While some interviewees noted the financial cost of commuting, higher salaries may compensate for this. Supporting people to widen their resource space is essential.

Storyline 3: the housing sector is complex and hard to navigate

A challenge described across interviews was the complexity of navigating the housing sector, both with regards to finding (and keeping) appropriate accommodation and understanding individual rights as a tenant.

For most interviewees there was a heavy reliance upon family and friends, either for financial support to cover the cost of housing or to simply live with. Several interviewees had experienced homelessness, and many reflected on poor housing conditions and crowded accommodation. Across interviews people were uncertain how they could apply for social housing, where they might access schemes and what their rights were in shared privately rented accommodation. Some of this confusion, particularly people being unaware of their rights, had led to people experiencing homelessness and highly insecure or substandard housing.

Interviewees shared individual experiences and circumstances regarding their own experiences, and where appropriate, experiences of others they knew, becoming homeless due to a breakdown of relationships with family or friends, and not having the financial means to pay a deposit or the weekly or monthly rent payment. In most cases people described having a friend or family member they could stay with in the short term, but some explained that their friends and family lived in small council properties and did not have extra rooms or space for anyone else to live, so were not a suitable long term housing solution.

“I know lots of people that have had to move into the homeless not the homeless shelters, the place where you go in between until you get a house with their families.” (F 30)

Talking about what could happen if he couldn't live with his sister, one interviewee explained that:

“Yes. I'd be homeless, probably I could rent a room or something like that but the thing with renting room is you live with different people and they don't live there permanent, so the people keep changing. It's really hard.” (F 23)

Another interviewee described the precarity of his housing situation and having experienced homelessness:

“Before that, I was kicking about on the streets for a while. Before that, I was with my parents. Well, mum and dad have broke up now, so I lived with my mum for a bit after my gran died, and I lived with my dad for a bit after I lived with my mum. Neither of them particularly worked out very well, so yes, ended up where I was. Then yes, I don't know. The HMO- I'll be honest, it's a bit dead, it's not great. I'm like the only English person there, and the only person under the age of 40 as well.” (M 27)

HMOs (house in multiple occupation) were mentioned across interviews. HMOs are dwellings with (1) at least three tenants forming more than one household and (2) shared toilet, bathroom or kitchen facilities with other tenants. For many interviewees HMOs were seen as the only option to secure independent housing, however they were generally not seen as desirable, as noted above. Interviewees explained that they did not want to live in shared accommodation. There were concerns about who one might live with and the quality of the accommodation.

HMOs are regulated but the numbers of such dwellings are rising fast in Corby, thus, impacting local areas and services. Many young people seemed to be unaware of their rights and were worried about raising complaints in case that led to eviction, as such they were living in what they described as precarious and sub-standard accommodation. Others were experiencing a hidden type of homelessness, while not living on the streets or in a shelter, they clearly had no secure accommodation and were unsure how to access support:

“Well, I'll be honest, when I was getting in the process of getting the room, I was actually sleeping in the toilet at work. I was lucky the place I was done nightshift, so I could finish my shift at ten o'clock and then go hide in the toilet. That was essentially what I had to do, and then thankfully I managed to get a room.” (M 27)

In general, high rents, deposits and high house prices were a barrier to long term renting and certainly home ownership for most interviewees:

“Yes, it's house prices. They just seem to have gone up and up and up. It's the situation for being self-employed I guess as well. That's a barrier for us that you need three years books, which he hasn't been doing it again for that long because we weren't here. That's really the barriers.” (F 37)

Interviewees talked about the need for more council housing and affordable private rental housing. There is chronic shortage of available social housing in Corby with over 1,000 households on housing waiting lists and long delays in administration (Whelan, 2019). Many interviewees had grown up in council housing and saw it as a desirable option:

“I just grew up on, I think it's class council estate. I'm not too sure. It was good growing up.” (M 16)

Another interviewee explained that

“I want to get a council house. I don't really want to rent but I'd need a job and then all save up and just hopefully get into a council house at some point.” (F 27)

Some had actively tried to get council housing and described the challenges:

“I tried to apply for a council house once, but was told that I was so far down the way years and years to get me on there. I gave up on that quite quickly. Then I've never gone back to see. When I left my son's dad, I had a brief discussion, but once again, because my mum was able to put me up for that time, they wouldn't have offered me any council housing.” (F 30)

Looking across the interviews, the most common way in which people were able to find secure housing was through family members. Several interviewees rented from family:

“I actually rent my dad's old house off of him. We used to live in their house, and then when I had my second child, we swapped because I needed a bigger house, they wanted to downsize. I rent off of them.” (F 37)

Another interviewee talked about living with family and not paying rent so that she could save for a deposit for a mortgage:

“I'm trying to save to buy a house, but that's quite difficult given the price of houses these days.” (F 31)

Those who were satisfied with their housing identified key conversion factors related to support either from family or through a government scheme. One interviewee explained that:

“Buying was only made possible really…my dad gave me some money for a deposit. He had a house in Corby that he sold that I was actually renting from him for a short time with a friend and then he gave me a lump sum for deposit and then my husband managed to match his. It was just being lucky with parents really.” (F 37)

Another interviewee explained how she had received family and government support:

“My dad was made redundant. Out of his redundancy package, you've been in that job for over 30 years. With that, he gave me part of the deposit for the house, plus the Help to Buy scheme that was present a few years ago when I got the keys to my house.” (F 24)

Several interviewees had bought houses through government help to buy schemes in this way, and people of all ages reflected that there were fewer government schemes and less support to own a house anymore.

“Without the help of buy scheme, because that covered 40% cost of the house. Without that, it would be very difficult. It's a five-bedroom house that I'm in. To find that somewhere else would be quite difficult, I think. For us, it's not really a seller's market at the moment.” (F 24)

“At that point, they were offering 95% mortgages and stuff like that, which was a real help because just getting that 5% together was a lot better than 10% or 15%. We need a lot more initiatives like that.” (M 37)

Securing appropriate, affordable housing was identified as a clear challenge for people of all ages. Interviewees told us that there was limited housing stock generally and that there was specifically very limited access to social housing. To access social housing there are long waits for assessment and during this period many young people explained that they had no alternative accommodation. The local authority received 8,212 housing applications in 2021/22 and made property offers to 1,557 applicants. As of 25 May 2022, there are currently 3,033 active applicants and 2,207 waiting processing.

There are significant challenges in Corby with regards to the housing resource base and it was clear across our data that this was compounded by many young people not understanding how the housing system worked; they were unclear of local schemes and how to access council housing. Many were unclear of their rights, particularly in terms of living in an HMO. Most had not sought advice and were unsure of where advice and guidance around housing could be found.

Conversion factors related to successfully managing the system and finding secure housing, on an individual level this related to family support while on a policy level it was recognized that schemes to support home ownership had been successful in the past but were generally unavailable to those we spoke to. While there are schemes available to support people, they come from a range of different sources and can be difficult to identify and apply for. Young people clearly needed support to understand what support was available and how to access it. Furthermore, it was clear that the most accessible form of housing for young people in Corby were HMOs which were clearly not desirable to young people. In part this is related to poor regulation (or possible illegality) of some HMOs. Understanding individual rights within this and knowing how to complain was confusing and young people were uncertain of how to navigate this. This made HMOs even less desirable.

Those interviewees aged over 30 reflected on how the successful conversion factors they had employed to access schemes were now much more confusing, there are many different actors within the housing sector and navigating the system was recognized as a huge challenge. Those who had seemingly successfully navigated the challenge either had family support (in terms of money and advice) or had spent a significant amount of time and energy in understanding their rights and seeking advice from statutory and third sector organizations.

Discussion

The research presented in this paper highlights the gap between young people's ambitions and desired way of living and their current situation and expectations. This points to a clear need for young people to be more involved in local policy development so that it meets their needs, reflects how they interact with the resource base and supports them in reaching their full potential. In this section we consider the main challenges that young people identified within their resource base, across the domains of education, housing and employment and suggest areas that could be explored further and developed through a participatory reflexive policy agenda.

While this paper focuses on individual resources and capabilities, it is impossible to disentangle individual experience from their surroundings, the history and geography of place matters. As Rosés and Wolf (2018) argue, regional social inequalities follow a very similar trend to individual inequalities. Their work demonstrates how regional inequalities decreased until the 1980s, after which inequalities remained constant or increased slightly. In Corby structural changes to local industry have compounded this. It is well-recognized in the literature that the transformation of industrial structure and spatial relocation of production are factors that can lead to changes in urban populations (Bartholomae et al., 2017). Our findings suggest that these urban changes in Corby have reduced the resource base and have impacted across individuals' experiences.

Our research particularly highlights how employment and housing has generally become more “precarious” in Corby and explains how this impacts across people's lives. While there are many ways of defining and measuring precarity it is probably the subjective experience of insecurity that is most important in understanding how it impacts on individual experience and outcomes (Origo and Pagani, 2009). Precarious work has been shown to be associated with higher levels of poverty and social exclusion, and research has shown that people working in a precarious manner are likely to have higher degrees of in-work poverty than those with permanent contracts in EU countries (e.g., Eurofound, 2017).

However, precarity is not just about employment, it cuts across individuals lives, and their families. As Beer et al. (2016) outline, precarious work and precarious housing can compound one another. Insecurity is key to how people experience precarity, whether in employment or housing. Precarious housing is disruptive and emotionally challenging. Precarity can make people more vulnerable to exploitation because of a lack of security (Banki, 2013; Jørgensen, 2016). With regards to education a precarious system of employment and housing means that those with lower levels of education and skills are likely to face the greatest challenges accessing secure housing and employment. This has been found to be particularly true for minoritized groups minorities (Bell and Blanchflower, 2011). When employment and housing are precarious people with higher levels of education may take on the lower skilled jobs that were previously held by young people. For those young people who have found school challenging, like many of our interviewees, this results in a smaller and more challenging resource base.

Precarity and security were important to those we interviewed in Corby and their concerns were well recognized by those we engaged with in our research findings, as well as local experts. Managing and regulating precarity and changing the rules and policy landscape so that precarity can be challenged needs to be a priority. We suggest there is a need for an engaging and participatory approach to developing new policy with precarity centered and recognized as a challenge across young people's lives. We suggest that those who will be impacted by policy must be involved in developing it. A reflexive policy agenda is a co-creation method in which welfare policies are planned, implemented, and evaluated with the active and intense involvement of those social groups to which policies are targeted to address inequality and reduce socio-economic divisions (Hoppe, 2011).

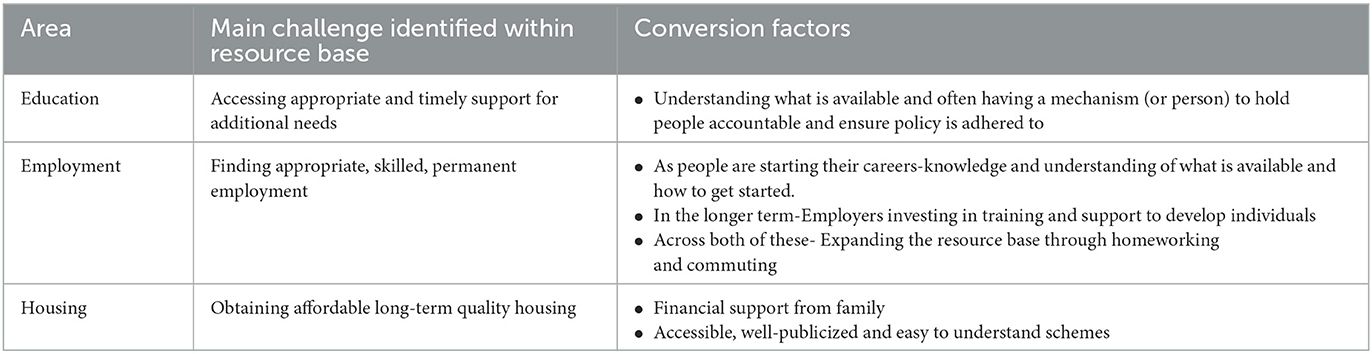

There are clearly challenging systemic issues that need to be addressed at a national level around housing, employment, and education. While we recognize that policy must address these large-scale, systems level issues, in this research we are focusing on the local policy agenda in Corby. In particular, this research has explored how young people in Corby can be supported to achieve better outcomes within the current resource space and how those elements of the resource space that are created locally, can be changed through local policy intervention. The Table 1 notes the main challenges and conversion factors discussed across interviews.

The conversion factors detailed above rely on people having the time and knowledge to research opportunities and navigate their resource base. With this in mind, and reviewing the storylines detailed in our findings, it is clearly important to recognize that navigating the resource base successfully involved fully understanding the landscape and finding appropriate support and guidance. These were the successful conversion factors that provided young people with the means to move forward and change their circumstances.

Public policy

In the sections below we outline what might be explored through a local reflexive policy agenda to develop participatory and reflexive public policy.

Housing

A reflexive policy agenda around housing should work with young people to explore and address two key points. First, advice and guidance. There is a clear need for simple easily accessible guidance regarding what the housing rules are locally, as well as where and how to access guidance and support and who to raise concerns with. Guidance and local pathways to support need to be developed with young people to ensure that advice services and complaints processes are transparent and simple. It is clear that understanding the housing landscape is central to young people's wellbeing and security, poor housing prospects have been linked to lowered wellbeing and poor mental health for young people in the UK. Good quality advice and support is likely to reduce the anxiety and mental health challenges faced by young people.

Second, there is a need to work with young people to develop policy specifically around affordable renting and the regulation of HMOs, which our research suggests need tighter local regulation and enforcement. It is important to note that there are already rules around HMOs in Corby. Any house being converted from a family home to an HMO for more than six people needs planning permission for change of use. However, any house smaller than this does not need planning permission, which is why so many smaller HMOs are able to slip through the net unnoticed (Cronin, 2021). There is existing advice available, for instance Shelter provides online guides. However, local more individualized guidance is essential, and the local authority therefore should develop policies with young people regarding HMOs that reflects the on the ground experience that young people face.

Education

Our research clearly identifies the importance of addressing the support needs of young people and their families and ensuring that parents and young people understand the education system and are aware of how to access additional support. There are two key areas of policy which could be developed with young people.

First, local policy agendas should work with young people and their families to understand the moments of challenge and the support that were successful in their educational experience. The urgency of developing policy that supports better practice of inclusive education is clear (Dell'Anna et al., 2021). Early intervention appears to be key here, as is listening to and treating parents and young people as the experts in their own lives. Local policies should be developed with children and young people as well as parents. This should involve listening to their lived experience to develop policies that explore how support needs can be met in a timely and effective manner (Morley et al., 2021).

Second, understanding the education system, knowing how to navigate it, and more generally having networks and resources to draw on was clearly an important factor in positive experiences of school and further/higher education. This is not a new finding, the importance of social capital in education is well established and long documented (e.g., DiMaggio, 1982; Wilson and Urick, 2021). Parents and young people need support to understand their rights and access support, local policy should be developed to provide transparent and easily accessible advice and support.

Employment

Our research in Corby has highlighted the need to support young people to engage with a wider range of different employment opportunities and see the possibilities of in work training and more informal development in order to expand their resource base. We identified three key areas to explore further in a reflexive policy agenda.

First, there is a need to highlight the opportunities available for young people to work their way up in companies locally. These opportunities need to be genuine long-term possibilities with secure contacts and must be paid fairly. Young people need to be involved in developing policy regarding what “good” employment looks like and the value of in-work mentoring and education. Within this, an exploration of the local value of mentoring and employment generally would be particularly key. While there is conflicting evidence, research findings do provide some support for the efficacy of mentoring interventions.

Second, many of the young people we interviewed reported a lack of adequate careers guidance in schools. In particular, for those individuals who did not receive support and advice from family and friends about the world of work, access to employability skills training and careers advice in school was a key factor in successfully moving into and remaining in the world of work. There appears to be a need for a holistic approach to careers advice and support. In England, there is statutory guidance that requires schools to provide independent personal guidance, however, this does not mean that career guidance is always available or accessible (Hearne and Neary, 2021). Many in our research reported needing support to bridge the worlds of education and the labor market and again networks and connections appeared to be relevant within this. Recent research has underlined the importance of focusing on young people's family context during the transition from school to employment (Broschinski et al., 2022). Working with young people to develop policy regarding careers guidance and employability training is essential to bridge this gap.

Third, young people seeking graduate employment or high skilled work, need to be engaged in developing policy guidance that supports this ambition. This area should be considered in terms of both housing and employment, and should explore how young people can be supported to move back to Corby post university or supported to stay and commute as they develop their careers.

Our research has highlighted that it is essential to involve young people in developing policies that support them and future young people to thrive in their education and employment and live in secure appropriate housing. Across these domains we have shared the challenges that young people face and identified ways in which policies could be developed to support young people to expand their resource base.

Conclusion

The research presented in this paper was developed with young people from Corby and presents individuals' perceptions of their resource base in order to consider how young people positively navigate the local resource base, as well as understanding the challenges they face. While there are many individual, local and systemic challenges, it is clear that across the areas explored the precarious nature of the resource base compounds all day to day challenges that young people face.

By exploring the different factors that support young people to do well, taking into account the possibilities their locality offers for them we have been able to highlight positive strategies that could inform the development of support for young people in navigating the areas of education, housing and employment. Understanding the resource base has supported us in identifying factors that could be changed locally through engaging in a Reflexive Policy Agenda and in this paper we have identified concrete actions and areas to develop through a participatory approach which engages with young people.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because, data was provided confidentially. Requests to access the datasets should be directed at: amVubnkuYmFya2VAeW91bmdmb3VuZGF0aW9uLm9yZw==.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

VB and SS contributed to conception and design of the study and wrote sections of the manuscript. JB, VK, SS, and VB reviewed data. VK organized the data. JB and VK carried out analysis. JB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Corby peer researchers; Joshua Taylor, Aimee Telfer and Carla Sambrook.

Conflict of interest

JB, VB, VK, and SS were employed by The Young Foundation.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^More information on the project can be found at: uplift-youth.eu.

References

Banki, S. (2013). “Precarity of place: a complement to the growing precariat literature,” in Power and Justice in the Contemporary World-System Conference, US. doi: 10.1080/23269995.2014.881139

Bartholomae, F., Nam, C. W., and Schoenberg, A. (2017). Urban shrinkage and resurgence in Germany. Urban Stud. 54, 2701–2718. doi: 10.1177/0042098016657780

Batista, L. F., and Correia, S. É. N. (2021). Capabilities approach to social innovation: a systematic review. Int. J. Innov. 9.

Beer, A., Bentley, R., Baker, E., Mason, K., Mallett, S., Kavanagh, A., et al. (2016). Neoliberalism, economic restructuring and policy change: precarious housing and precarious employment in Australia. Urban Stud. 53, 1542–1558. doi: 10.1177/0042098015596922

Bell, D., and Blanchflower, D. (2011). Young people and the great recession. Oxford Rev. Econ. Policy 27, 241–267. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grr011

Broschinski, S., Feldhaus, M., Assmann, M. L., and Heidenreich, M. (2022). The role of family social capital in school-to-work transitions of young adults in Germany. J. Vocat. Behav. 139, 103790. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103790

Cronin, K. (2021). How Corby Became the go-to Destination for HMO Landlords. Northamptonshire Telegraph. Available online at: https://www.northantstelegraph.co.uk/news/people/how-corby-became-the-go-to-destination-for-hmo-landlords-3305192 (accessed May, 2023).

Dell'Anna, S., Pellegrini, M., and Ianes, D. (2021). Experiences and learning outcomes of students without special educational needs in inclusive settings: a systematic review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 944–959. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1592248

DiMaggio, P. (1982). Cultural capital and school success: the impact of status culture participation on the grades of US high school students. Am. Sociol. Rev. 47, 189–201. doi: 10.2307/2094962

Hart, C. S., and Brando, N. (2018). Children's Well-being, agency and participatory rights: a capability approach to education. Eur. J. Educ. 53, 1–17. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12284

Hearne, L., and Neary, S. (2021). Let's talk about career guidance in secondary schools! A consideration of the professional capital of school staff in Ireland and England. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 21, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10775-020-09424-5

Hoppe, R. (2011). The Governance of Problems: Puzzling, Powering and Participation. Bristol: Policy Press. doi: 10.46692/9781847426307

Howaldt, J., and Schwarz, M. (2017). Social innovation and human development—how the capabilities approach and social innovation theory mutually support each other. J. Human Dev. Capabil. 18. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2016.1251401

Jørgensen, M. B. (2016). ‘Precariat – what it is and isn't – towards an understanding of what it does'. Crit. Sociol. 42, 959–974. doi: 10.1177/0896920515608925

Kimhur, B. (2020). How to apply the capability approach to housing policy? concepts, theories and challenges. Hous. Theory. Soc. 37, 257–277. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2019.1706630

Morley, D., Banks, T., Haslingden, C., Kirk, B., Parkinson, S., Van Rossum, T., et al. (2021). Including pupils with special educational needs and/or disabilities in mainstream secondary physical education: a revisit study. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 27, 401–418. doi: 10.1177/1356336X20953872

Origo, F., and Pagani, L. (2009). Flexicurity and job satisfaction in Europe: the importance of perceived and actual job stability for well-being at work. Labour Econ. 16, 547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2009.02.003

Rosés, J. R., and Wolf, N. (2018). Regional Economic Development in Europe, 1900-2010: a Description of the Patterns. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12749. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3180497

Shearn, K., Brook, A., Humphreys, H., and Wardle, C. (2021). Mixed methods participatory action research to inform service design based on the capabilities approach, in the North of England. Child. Soc. e12496. doi: 10.1111/chso.12496 [Epub ahead of print].

Walker, M., and Unterhalter, E. (2007). “The capability approach: its potential for work in education,” in Amartya Sen's Capability Approach and Social Justice in Education (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 1–18. doi: 10.1057/9780230604810_1

Whelan, M. (2019). More than 1,000. Households on Housing Waiting List in Corby. Northamptonshire Telegraph. Available online at: https://www.northantstelegraph.co.uk/news/more-1000-households-housing-waiting-list-corby-130328 (accessed May, 2023).

Keywords: capability approach, housing, employment, education, young people, participatory research

Citation: Barke J, Boelman V, Khairunnisa V and Shah S (2023) Young people's strategies for navigating education, employment, and housing: a case study from Corby UK. Front. Sustain. Cities 5:1149901. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.1149901

Received: 23 January 2023; Accepted: 01 June 2023;

Published: 29 June 2023.

Edited by:

Márton Medgyesi, TÁRKI Social Research Institute, HungaryReviewed by:

Neil Simcock, Liverpool John Moores University, United KingdomNathalie Ortar, UMR5593 Laboratoire Aménagement, Économie, Transport (LAET), France

Copyright © 2023 Barke, Boelman, Khairunnisa and Shah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jenny Barke, amVubnkuYmFya2VAeW91bmdmb3VuZGF0aW9uLm9yZw==

Jenny Barke

Jenny Barke Victoria Boelman

Victoria Boelman Vinkha Khairunnisa

Vinkha Khairunnisa