95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Cities , 08 March 2023

Sec. Social Inclusion in Cities

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2023.1098313

This article is part of the Research Topic Youth Vulnerabilities in European Cities View all 9 articles

Usue Lorenz1,2*

Usue Lorenz1,2*This research aims to explore in what extent young people can enhance their individual skills, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors by taking part in urban policymaking co-creation processes. The empirical study conducted within the UPLIFT project is based on two main theoretical influences: co-creation and youth participation in policymaking and the capability approach. The author found that the young participants in the UPLIFT co-creation process in Barakaldo who were encountering vulnerabilities or difficulties in housing, experienced positive individual effects from their participation in the process. Framed in terms of the Capability Approach, the process impacts positively on young people's individual abilities (individual factors) that may influence their opportunities (capabilities) and life strategies (functionings) in the housing domain. In the following lines, I also suggest a set of critical aspects that need to be pursued in a co-creative policymaking process to help increase the vulnerable young participants' knowledge and attitudes toward community planning initiatives in the field of urban policymaking.

Citizen involvement in institutional policymaking has been attracting interest of both among policymakers and academics. Although the first studies of citizen co-production in public services were published in the 1970s by Elinor Ostrom and her team, the topic did not raise much interest in those days as the approach was not relevant to the time (Brandsen et al., 2018, p. 3–8).

Since then, times have changed, and the scale and complexity of the global challenges have become greater. The United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), launched by a UN Summit in New York in 2015, are the global expression of a transformative agenda set to tackle pressing global economic, social and environmental challenges. Nonetheless, responses to global challenges like demographics, the digital transformation, and climate change are complex to understand and resolve. And, thus, given the scale and complexity, solutions will only be reached by engaging with all relevant stakeholders at all levels. Cities will be fundamental to the implementation of all 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as stated by the UN in the resolution adopted by the General Assembly on September 25, 2015 (United Nations, 2016).

The growing importance of cities to ground and work toward finding local responses to global pressing challenges by engaging with stakeholders and citizens is often fostered due to the benefits it provides in terms of improved governance; quality of services, projects and programs delivered; and, better social acceptance.

In this context, the design and delivery of public services, as well as the participation of citizens within these processes, have gain momentum at the urban level. Cities are increasingly vulnerable to major global changes (climate, digitalization, and demographics) (Elmqvist et al., 2019), but are also key when it comes to driving sustainable transition processes in real contexts and through co-creation (Kronsell and Mukhtar-Landgren, 2018; Bulkeley et al., 2019; Hajer and Versteeg, 2019, p. 123). At the heart of this is the proximity to our citizens' day-to-day lives, which facilitates grounding and experimenting with the different challenges faced at the city level (Frantzeskaki and Rok, 2018).

The growing academic attention given to innovative approaches to policy co-creation over the years is based on the design and implementation of innovative participatory processes and approaches to tackle societal challenges (Brandsen et al., 2018). In this respect, living labs have gained importance at an urban level as a new user-centered and open innovation-based approach to policymaking to address such challenges (Hossain et al., 2019). Practitioners are also encouraged to overcome various difficulties and needs by using co-creation processes (Matti et al., 2022), and by citizen-led solutions with greater societal acceptance and effectiveness (Vladimirova et al., 2022).

Thus, as it has been stated above, co-creation can play a prominent role at the urban level in generating effective and innovative solutions to tackle the challenges of a world dominated by complexity and uncertainty. Nevertheless, as it is shown through this study, this kind of processes also contribute to enhance the individual capabilities of, in this case young individuals that are being part of these processes. Based on the UPLIFT co-creation process in Barakaldo, this work aims to explore the connections between institutionalized participatory policy making processes, and particularly co-creation, with the capability approach, a theoretical framework that allows to define how people can enhance their individual capabilities. This way, the discussion of the paper defines three main elements that in the case of the co-creation process in Barakaldo have been key in order to guarantee, not only the development of innovative and effective solutions, but also to foster the generation of knowledge and skills development among the participants.

The discussion in Section 6.1 will be complemented by: the explanation of the capability approach and concepts on youth participation in policy making processes as frameworks of analysis; the methodology used to analyze the results and the presentation of the case study and Section 6.1.

The research conducted departs from the notions, frameworks and methodologies developed within two different theoretical influences: (1) the Capability Approach (CA), and (2) Co-creation and youth participation in policymaking.

The following sections introduce these influences and their relevance for the research conducted, explain how they are integrated and paves the way toward understanding the questions posed by the research team.

The Capability Approach (CA) is a theoretical approach, concentrating on wellbeing, development and justice. It was pioneered by Amartya Sen and further developed and embraced by Martha Nussbaum and other scholars (Robeyns and Byskov, 2021). It is conceived as a flexible and multi-purpose framework that helps interpret notions of poverty, inequality or wellbeing in different fields such as development studies and policymaking, and welfare economics, among others (Robeyns and Byskov, 2021). The following two claims are at the basis of the framework: freedom to achieve wellbeing is of moral importance and must be understood in terms of a person's so-called capabilities.

According to this framework, functionings reflect what people are (being) or do (doing), and can be either good or bad (Kimhur, 2020). Some examples of these include being well-nourished, having children, having proper housing, being employed, and completing secondary school.

Moreover, it links these functioning to what it defines as capabilities. According to Sen (1999, p. 40) capabilities represents the various combinations of functionings (beings and doings) that the person can achieve. Having capabilities means that a person has the freedom, real rights and opportunities to realize valuable functioning as an active agent (Kimhur, 2020). The functioning people actually achieve because of their capabilities depends on individual preferences. In this framework, preferences constitute the link between capabilities and functionings.

Formal freedoms refer to the material aids that a given person can access (income, goods or services) and the formal legal rights people enjoy (e.g., rights recognized by the Constitution) to live the life of their choice. Resources are the formal opportunities a person has to be or do what is important to them. Capabilities are affected by a person's formal freedoms or the resources available for, which depend greatly on the context.

Conversion factors are the bridge between formal freedoms and the capabilities or the available opportunities to achieve the valued positions. Conversion factors were classified by Robeyns (2005) as personal (including sex, reading skills, intelligence, and disabilities, among others), social (e.g., public policies, social norms, discriminating practices, gender roles, societal hierarchies and power relations), and, environmental (e.g., climate, geographical location). All of this influences people's ability to transform formal resources into valuable opportunities (capabilities) and functionings. Examples of these are individual features like sex, intelligence, social skills, or abilities. Social conditions can be, for instance social norms and practices like gender inequality that might prevent women from transforming formal opportunities into desired positions, such as in the labor market.

The focus of the CA is on wellbeing and at its center are people's capabilities, understood as “what people are effectively able to do and to be” (Robeyns, 2005) or “the real freedoms that people have to live the life they value (or have reason to value)” (Volkert and Schneider, 2011). Thus, the achieved functioning may differ from the capability in that the former are achievements while the later are valuable options to choose from. In this context policies are evaluated in terms of their impact on people's wellbeing, with the CA approach having been applied in different policy analyses such as the Human Development Reports of the United Nations (Kimhur, 2020). For example, it asks whether people have access to high -quality education (capabilities) and whether the means and resources necessary for this capability are available (formal resources). The core concepts of the CA are relevant to understanding the route from formal freedoms to real freedoms which lead to creating individual life-strategies or functionings in the different life domains (labor market, housing, education).

Empirical analysis based on assessing capabilities and functionings in a given policy field is prolific. Volkert and Schneider (2011) provided some of these applications, with examples of how CA is applied in high-income OECD countries, mainly focused on studies related to understanding capabilities and functionings. Robeyns (2006) also explored and described the topics or themes of application addressed by the CA: examining the human development of a country, small-scale development projects, or, policy analysis, among others. Indeed, the most widespread approach in CA empirical analysis appears to be assessing functionings, capabilities, or functioning together with capabilities on different application themes.

However, less attention has been given to conversion factors in the field of policymaking and developmental processes, even though personal and group-specific characteristics are crucial for bridging means and freedoms. Conversion factors can boost or inhibit people when transforming formal opportunities into valuable opportunities or the desired outcomes. Individuals and their social context influence the ability they have to pave that path.

In this sense, to reflect upon capabilities in policy making processes through capability approach, puts the focus on how young people can enhance their individual conversions factors, reflecting not only on the pathways that policies follow toward transformation, but on youngsters' strategies to transform their lives.

Following this premise, Egdell and McQuaid (2016) highlighted the role played by stakeholders and young people in developing job activation initiatives and acknowledged that such participation has affected their own learning and personal development. Learning and personal development happen both at the individual level (increased skills and knowledge) and in a broader socio-economic context (legal framework, etc.). The former could include appropriate information on the labor market, and the skills needed to take opportunities. Other conversion factors are external, such as social and structural factors (e.g., social stratification, labor market segregation, among others). The authors presented three case studies showing how young people involved in developmental processes linked to job activation programs enhance their capabilities in terms of empowerment (that is, their voice is heard in decision making), individual conversion factors (increased skills and knowledge regarding the topic and certain aspects as self-belief and confidence) and external conversion factors (ability to influence external factors).

The following section explores how young people can get involved in policy-making processes with public institutions through co-creation.

Co-creation in policymaking has attracted increasing interest when it comes to delivering public services and thinking up and creating solutions for political and social challenges (Torfing et al., 2019; Itten et al., 2020). It involves a wide range of actors where their experience, knowledge, and ideas are combined to find solutions. The idea is that given that stakeholders and citizens are actively involved, this leads to a better acceptance of the results and makes it possible for more context-based and tailored solutions to be found (Lorenz, 2020).

It has recently gained prominence as an approach to tackle the increasing complexity of the current societal challenges spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, digital transformation, demographic changes, and other pressing global matters, all of which need a swift and targeted policy response.

In the field of public policies, citizens are the main stakeholders with whom to engage in co-creation processes during the various stages of the policy cycle dealing with social issues (Voorberg et al., 2015). Citizens become co-creators because their specific resources and competences are valuable for delivering public service. The co-creative processes are also learning ones where the participants learn not only how to face societal challenges but also from the other participants' competences. Nonetheless, learning in co-creation is an unexplored topic in the literature, especially citizen-related.

Young people are one group of citizens that participate in co-creative processes. Youth participation is understood as “a process of involving youth in the institutions and the decisions that affect their lives” (Checkoway et al., 1995). It is particularly meaningful in fields where young people's knowledge is relevant and valuable as they improve the quality of the decision taken as well as help better understand the topic addressed (Blakeslee and Walker, 2018), usually in areas that influence their own interests or everyday issues (Vromen and Collin, 2010; Head, 2011). Among the fields where young people find their participation is more influential are social action, which involves environmental, neighborhood, and racial issues; community planning, public advocacy; community education, related to actions that strengthen youth confidence to make changes; and local development services (Checkoway et al., 1995). Head (2011) proposed the following three rationales for greater youth involvement: protecting their rights, influencing the policies (services, programs, and alike) that directly impact them; and social participation that leads to developmental benefits for the young people involved in such processes.

Delving deeper into the notion of youth participation, scholars have long studied and categorized the varying degrees of this in public issues. These can be divided into linear and non-linear modes of participation. Among the linear ones, Arnstein (1969), Hart (1992), and the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2, 2022) typologies organized youth participation on a scale from lower to higher levels based on a varied combination of aspects related to participation and the achieved intensity. These aspects include roles played in initiating adult-youth interaction, decision-making, or a specific role such as informing, consulting, involving, or collaborating (Wong et al., 2010). Treseder (1997) argued that youth participation is non-linear, with no ideal type of participation but rather different types based on initiation and decision-making roles each time.

Thus, youth participation in policymaking can be understood as young people collaborating with other stakeholders during the various stages of the policy cycle and with different types of participation to co-create solutions that deal with societal challenges that directly affect their lives.

The benefits of young individuals taking part in community planning are classified according to the different potential beneficiaries of the community planning results, which are individuals, organizations, and the community (Checkoway et al., 1995; Frank, 2006). Individual benefits are the ones experienced by the participants, while other groups of stakeholders, such as the community or society as a whole, reap the broader benefits. The Table 1 summarizes the benefits of youth participation in policymaking at the individual and broader levels.

At a societal level, youth participation can provide indirect benefits to society, mainly to the community and the organizations participating from the developmental processes. Such aspects include broadening civic participation, experience for active citizen and leadership for the future (Hoekstra and Gentili, 2021); increased knowledge of youth and community concerns and more feasible and targeted solutions or recommendations (Frank, 2006).

YPAR processes are also empowering and affect young people at the individual level (Ozer and Douglas, 2013). By involving them in participatory activities such as analyzing a community's challenges, research activities, and decision-making to influence policies and decisions, young people experience personal positive effects such as motivation to influence their communities, socio-political skills, and participatory behavior.

Frank (2006) observed that taking part in planning processes has a positive effect on young people by increasing their skills and knowledge (regarding the topic, the local community, and how to create change). They were also found to become more confident and assertive as well as wanting to collaborate more in other forms of civic engagement, with increased enthusiasm for planning and community involvement. The author identified frustration as a negative behavioral effect when there is a lack of adult responsiveness to youth insights. According to Checkoway et al. (1995), participation benefits young people by improving their behavior and attitudes in terms of open-mindedness, personal responsibility, and self-esteem, among others. In addition, the author found an increase in the skills and knowledge connected with the topics addressed by the process. Meanwhile, Vromen and Collin (2010) included concepts related to participatory governance, youth participation, and policymaking as key issues to be discussed with young people and other stakeholders when reflecting together on how they perceive youth participation processes.

This section explains how the two literature streams presented, the CA and the policy co-creation with young people, are integrated. As explained above, the CA is a comprehensive, multi-dimensional and normative approach for interpreting inequality as a relationship between structural factors such as formal rights and possibilities provided by the socio-economic context (i.e., Law and policy programs) and individual factors, such as individual conditions, preferences, and life choices (Robeyns and Byskov, 2021). Youth engagement in co-creative policymaking processes is associated with benefits on an individual level (Checkoway et al., 1995; Frank, 2006; Ozer and Douglas, 2013) and for the wider society (Frank, 2006; Head, 2011). Whereas, there are clear linkages between both benefits, this study focuses on the elements of the co-creation process that have allowed the development of the individual benefits of the participants in connection with broader structural factors. Thus, policy co-creation framed within the CA allows understanding of how the process is influencing the young individual's abilities (individual conversion factors) in relation with the resources, their opportunities (capabilities) and their choices (functionings) in the life domain addressed by the process.

The CA also provides a framework in which policy co-creation can be structured as a learning and personal development process to benefit the young participants (Egdell and McQuaid, 2016). Participatory approaches addressing the co-creation of new policy initiatives that intend to diminish urban inequalities are very well supported by the CA approach due to its emphasis on agency (Hoekstra and Gentili, 2021). Agency refers to the relative autonomy of the individuals in their actions under the constraints of the structural factors. Therefore, policy co-creation can adopt a focus on agency by increasing the individual abilities or conversion factors of the young participants (Checkoway et al., 1995; Frank, 2006; Ozer and Douglas, 2013) as crucial aspects that support them in choosing what they really value in life (Robeyns, 2005).

Funded by Lewin (1946), participatory action research (PAR) is as a research methodology that aims not only to create knowledge collaboratively with those affected by the research, but also to become an empowering process for the participants. Due to its emphasis on understanding human experiences and taking action in order to improve difficult situations, this approach is a valuable methodology for the case study on a policy co-creation process that aims not only to improve policy but to become a personal development process. Three main features of this approach are particularly valuable for the case study.

First, researchers work collaboratively with other participants affected by the research (Olshansky et al., 2005) by examining and interpreting their own social world and exploring the relationship between the individual and other social interactions (Kemmis and Wilkinson, 1998, p. 24). Researchers do not approach the process to study it from a distance, they are, together with the other participants, part of the process of change.

Second, PAR is practical and reflexive as it seeks to improve and change the participant's situation by developing, implementing, and reflecting on actions and their own situation as part of the research and knowledge generation process (Kemmis and Wilkinson, 1998, p. 24; Olshansky et al., 2005; Loewenson et al., 2014).

Third, PAR processes are empowering processes in which people are involved in reflective processes to explore the individual and social limitations that limit their self-development and self-determination (Kemmis and Wilkinson, 1998, p. 24).

The co-creation process was structured following the PAR approach. Researchers could work collaboratively with other participants affected by the research in discussion sessions where strategies and actions were designed to address the challenge. In that sense, policy makers, policy implementers and youngsters did not play only the role of “subjects” of study, but also an active role in aspects like designing the process, and deciding on the actions adopted, among others. It was also designed to empower young people and involve them in the process of policy co-creation, thus supporting them in their self-development processes and giving them resources to have their voice heard in local policy making and enhance their abilities.

Moreover, regarding the analysis of the results extracted from the aforementioned participatory process, a quantitative method with a survey of the young participants in the co-creation process of UPLIFT in Barakaldo is used (see the survey in Annex 1). Thus, the questions included in the survey respond to the categories included as determinant to advance the knowledge and skills of the respondents (see Table 2). The fieldwork took place between December 2021 and July 2022, with a pre and post-survey to examine whether the young individuals were increasing their knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors because of collaborating in UPLIFT. The co-creation process included thirteen young people, with the number varying in the different sessions. Nine people responded to the pre- and post-survey at the beginning and end of the process. Five of them had recurring responses as they filled in the survey at the beginning and end of the process, allowing a direct observation of the changes in the items assessed.

UPLIFT is a project funded by Horizon 2020 exploring how young people's voices can be placed at the center of youth policy in areas of housing, education, and employment. Since January 2020, the project has been studying the cases of 16 cities in Europe and the UK, including Barakaldo, to gain a deeper understanding of the inequalities affecting young people. To this end, various data analyses, interviews, and participatory workshops are being carried out with policymakers and implementers. By incorporating these perspectives into the policy design process, UPLIFT aims to find innovative interventions in a bottom-up approach. Specifically, together with communities in four locations (Amsterdam, Tallin, Sfântu Gheorghe, and Barakaldo), policy co-creation processes involving a group of young people from each city have been put forward to address and reduce inequality in different life domains.

Barakaldo is a 100,000-inhabitant river-port town that is part of a larger suburban area of Bilbao, a medium-sized city within the province of Bizkaia, one of the three provinces of the region of the Basque Country (2.2 million inhabitants) in Spain. Lorenz and Icaran (2022) conduct a research based on qualitative methods to explore the structural characteristics of the economy, demography, and social issues and its impact on young people between 18 and 30 years of age in Barakaldo. They are the cohort of the population that experience the strongest effects of the economic downturns in the city in terms of higher unemployment rates, struggles in accessing housing and other related social inequalities, especially after the financial crisis of 2008. In the housing domain, the research found that the desired position of the young people in Barakaldo would be to have their own house, either from the private or public housing market, as renting prices are higher than the mortgage monthly payments. The strategy for evolving from the current position to the desired one, relies in achieving a good economic position (i.e., a good job position, stable and well paid) that enables them to save enough money or to get funding to buy and maintain a house and a mortgage. However, many of them still live in the family house, in a rented house or have not thought to live by their own yet due to the high unemployment rates of young people and a public social housing stock, which, although much more affordable than the private sector, is insufficient to meet their housing demand.

The co-creation process in Barakaldo sought to give young people a real voice in local policy making by setting up a co-creative process to produce a reflexive policy agenda (RPA) for improving local housing policies and by developing a dialogue between young people and local authorities in Barakaldo. The process itself is not only a way to achieve a better reflexive policy agenda that can be put into action more easily, but it is also a way to understand how participatory processes involving youth can give them the chance to transform the formal resources at their disposal into real opportunities through the improvement of their abilities.

The co-creation process in Barakaldo departs from the two different theoretical influences and frameworks described above: the capability approach and co-creation and youth participation in policymaking.

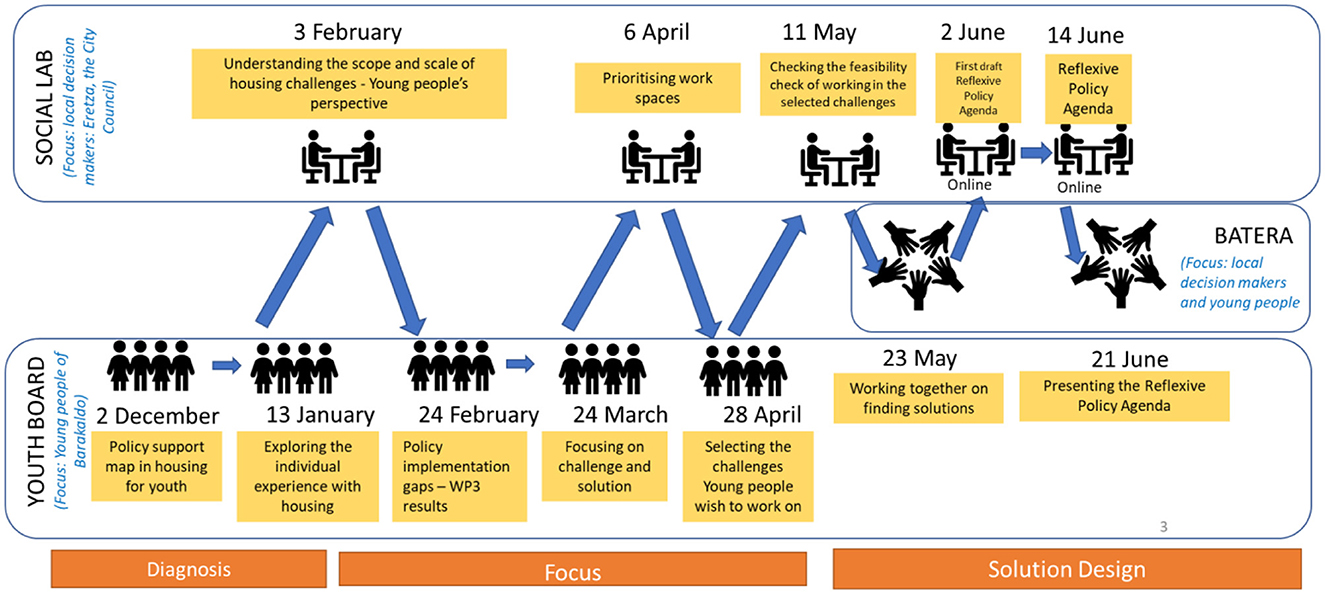

The process entails a collective discussion regarding the issue (housing related inequalities and challenges for the young people in Barakaldo) and designing strategies and actions to tackle it. All of this produced collective knowledge with which to define a Reflexive Policy Agenda (RPA) for improving Barakaldo's housing policy. This collective discussion involved four main types of actors (researchers that act as facilitators decisionmakers and young people). Each bringing different but equally valuable knowledge. As shown in Figure 1, participation took place in the interplay of three spaces: The Youth Board (YB), which focused on the dialogue with young people, Social Lab (SL), which concentrated on the dialogue with decision makers and Batera, which merged the YB and the SL, focusing on the collaboration between the two groups. The process followed a co-generative model based on the cyclical iteration of the YB, the SL and Batera and was built following a traditional policymaking process from problem definition to the analysis of options and development of policy solutions.

Figure 1. The co-creation process for a Reflexive Policy Agenda (RPA) in Barakaldo. Source: Own elaboration.

The result of the co-creation process was a reflexive policy agenda (RPA) targeted at the local housing policy, where the participants co-created an action plan for its improvement. The co-creation process continuously sought to increase the knowledge and skills of the young participants, with the facilitators being responsible for fostering the conditions in which the participants could reflect, decide, and take action. In order to encourage them to take action, the facilitators nourished the process with the theoretical knowledge they generated, together with other researchers of the project when analyzing urban inequalities through the CA (UPLIFT, 2021), as well as the knowledge, insights, and opinions of the young people concerning their experiences and life difficulties.

The CA provided an analytical tool to grasp better the urban housing inequality the young participants were experiencing and a framework to understand how the process influenced young people's individual abilities. The framework helped to gain insight into the relationship between the formal freedom of choices that young people had in Barakaldo, such as formal policies, plans, programs, and laws regarding housing in Barakaldo, the real choice young people actually had to make use of these formal spaces (capabilities), and the final outcomes they were experiencing in housing (functionings). The young participants showed they were vulnerable in the housing domain as their desired situation in housing did not match their current situation. In other words, although the overall desired functioning was to have their own accommodation, either rented or bought, the achieved outcome was that they were either living in shared accommodation or were not yet emancipated.

Through co-creation techniques, the young people became involved in the first phases of the policy-making process (defining the problem—diagnosis and focus, and formulating the policy—solution design) in the field of urban housing. The subsequent phases were policy implementation and policy evaluation.

As explained in the theoretical framework, youth participation in policymaking can potentially have a positive effect at both an individual level and a broader one. Barakaldo's co-creation process focused on understanding what individual benefits or individual conversion factors framed on CA terms the young people gained by helping co-create a reflexive policy agenda. The Table 2 summarizes the core concepts explored regarding the individual conversion factors and the items applied for measuring them.

All the items shown in the Table 2 can help ascertain whether participation in co-creation processes, such as the one presented in the case study, can benefit young people so that they are able to use the formal resources available in their city to achieve a better position in different life domains. Therefore, framed in terms of the CA, the co-creation process aims to enhance young people's capabilities and real freedoms (life opportunities) by improving their individual conversion factors in terms of greater knowledge and skills.

The survey was designed including questions on the items for assessing the skills and knowledge; and the behaviors and attitudes shown in Table 2. The analysis of the data collected through the survey are summarized in this section.

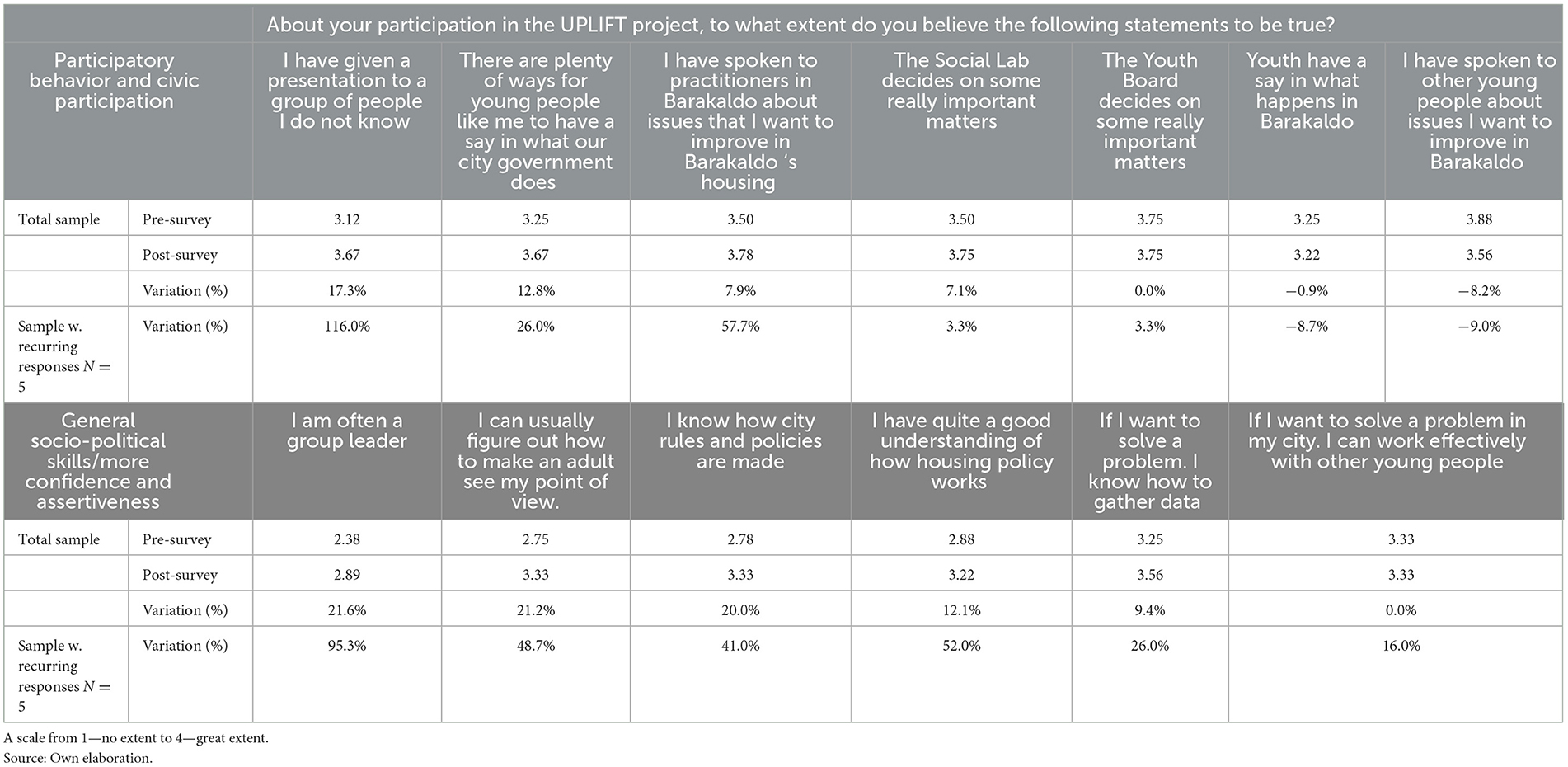

As it can be seen in Table 3, young individuals believe that participating in the UPLIFT co-creation process increases their knowledge and skills on the housing and policymaking topic (average score ranks higher than 3 almost in all the items before and after the participation in the process, on a scale from 1—no extent to 4—great extent). However, their answers change after the participation in the process: the knowledge on some topics increases and others decrease in relation to their initial belief of what the process could bring them in terms of knowledge and skills. The knowledge on topics related to the organizations working on housing in the city, the organizations to be addressed for advice in housing, the housing topic in Barakaldo, the policymaking process and how to widen one's social network increase after having participated in the process. Nevertheless, direct knowledge on how to improve one own's housing situation decreases after having participated in the process: how to find better housing conditions, including affordable opportunities or funding programs for improving access to housing.

These patterns suggest that those that were participating from the beginning to the end got more intense knowledge on the topics that were addressed throughout the process.

Concerning attitudes and behaviors, as seen in Table 4, the young people believed they had gained some positive attitudes toward civic participation, such as feeling more prepared to give a presentation to someone they do not know, to express their views to policymakers, to find out how they could participate in policymaking in Barakaldo and influence decision-making within the scope of the UPLIFT project, Social Lab, and the Youth Board. Nevertheless, the process showed no change in civic participatory behaviors in fields other than housing, like increasing dialogue with other young people on the issues to improve in the city or believing that young people have a say in what happens in the city.

Table 4. How participating in UPLIFT affected the young individuals' attitudes and behaviors (participatory behavior and socio-political skills).

The attitude toward policy has positively changed with respondents demonstrating they were better equipped to understand and participate effectively in co-creative policymaking. They also felt more confident taking on a leading role, communicating their point of view to adults, knowing how to get involved in co-creative policymaking, and have gained insight into the housing policy of Barakaldo.

Recurring responses showed that the participants in the whole process have gained more positive attitudes toward collaborating in policymaking.

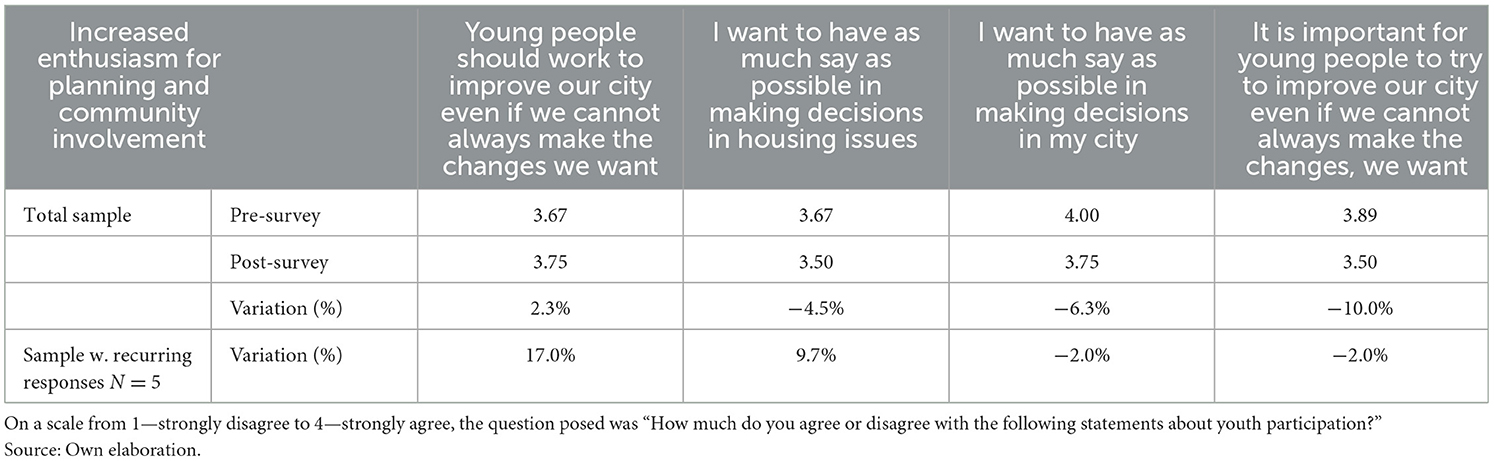

In general, as it is shown in Table 5, the young people's attitudes and behaviors toward influencing one's community presented a negative pattern, meaning that their expectations about influencing Barakaldo's housing policies through the co-creation process were higher in the beginning than after the process. While the young people had overall positive attitudes toward decision-making in housing (the topic tackled by UPLIFT), this was not the case regarding other planning or community planning initiatives that do not lead to changes. Nonetheless, they seemed keen to collaborate in such processes that lead to changes, even the ones they did not necessarily like.

Table 5. How participating in UPLIFT affected the young individuals' attitudes and behaviors (motivation to influence one's community/for planning and community involvement).

Our results support other findings that co-creative processes can be associated with, and possibly a precursor to, positive behavior and attitude changes of the young participants toward participation (Head, 2011; Ozer and Douglas, 2013), increased interest for influencing community (Frank, 2006; Head, 2011) and confidence and assertiveness (Frank, 2006) and increased in socio-political skills (Ozer and Douglas, 2013).

Co-creative processes as empowering and learning processes can be constructed. The following discussion is built around the following question: what elements should the co-creative policymaking processes consider for influencing positively the young individuals?

The author here proposes three elements of the process that can be considered key in order to enable that young people increase their knowledge about the policy problem tackled, as well as their attitudes and behaviors toward policymaking.

First, the author suggests that supporting young people to express their more intimate experiences, insights, and opinions by building spaces where they find free and safe to express themselves has been a core element in the process. To the extent that they feel that their contribution improves both the understanding and the result of the policymaking process (Checkoway et al., 1995; Blakeslee and Walker, 2018); the more meaningful their participation will be for them. To find their participation meaningful is, according to Vromen and Collin (2010) and Head (2011), one of the main reasons for youngsters to engage in policymaking.

The author also found that these spaces must become places to have fun and build trusting relationships with other participants, so that it is easier for them to open up and give insights on their own experiences and concerns, especially when it comes to vulnerable young people. To open up and give insights, it is recommended that resources and means are provided to support them in communicating their insights to other young people and adults involved in the process. This can generate on them the feeling that are influencing the process, which as suggested by Head (2011) and Vromen and Collin (2010) can make the difference in the success of a co-creation process.

Second, for the co-creation process to become learning processes for the young participants, it is needed to embed theoretical and practical contents on the issue tackled as: policymaking and the wider socioeconomic context (Egdell and McQuaid, 2016). These learnings, if directed toward enhancing their individual conversion factors, are crucial for bridging between means, freedoms and personal outcomes (Kimhur, 2020).

As stated by Robeyns (2006) personal, social and environmental conversion factors can support young participants on paving their individual life strategies following the logic provided by the CA (Kimhur, 2020). They can support young people on understanding the formal material aids and legal rights they can access (formal resources), and how to transform them in possibilities to choose from (capabilities) and life choices (functionings). As proposed by Egdell and McQuaid (2016), expert knowledge on the topic tackled can raise ability to effectively understand structural factors related to policymaking, the process and the policy challenge. Evidence from the case study show how young participants enhanced their individual and social conversion factors. For this purpose, the author recommends that the process embeds practical and theoretical insights on fields such as community and environment, including government and community organizations; policy planning knowledge and topical knowledge (Frank, 2006); and participatory governance and how it works (Vromen and Collin, 2010). In the case study such concepts were translated into contents that raised the participant's understanding and knowledge of the structural factors that according to the CA influence their capabilities in housing. The contents included presentations about the policy cycle (problem definition, implementation, design, evaluation...), how city government works, urban policy instruments and policy or stakeholder mapping.

Young people in policymaking not only learn from the theoretical and practical knowledge that is embedded in the process, but also from the interaction with other participants. In the light of the case study, it is observed that as suggested by Voorberg et al. (2015) young participants enhance their knowledge on the main topic addressed by the process due to the competences that other participants have on policymaking and housing. By sharing and exchanging the resources and competences of each participant on housing and personal experiences, all the participants have gained valuable insights on the topic and policymaking. From the lenses of the CA, this leads to a knowledge increase to understand the existing resources and possibilities in housing.

Third, young participants can be supported in developing positive attitudes toward participation in policymaking and increasing their enthusiasm for participating in a community initiative, which are key individual benefits associated to young participation in policymaking (Checkoway et al., 1995; Frank, 2006; Ozer and Douglas, 2013). Inspired by the different degrees of youth participation studied in the theoretical framework, the author recommends that young participants are continuously encouraged to climbing up the steps of the ladder of participation. This means working on turning them in process owners by encouraging them to give opinion and to take relevant decisions on how to move forward in the process, exploring in each step of the process how to take a more relevant role on initiating the idea and making them take more relevant decisions (Treseder, 1997). For making them feel more assertive and confident, which is a potential benefit of youth participation raised by Frank (2006) the author advises to develop actions toward making them aware on how their insights are used for policy improvement as it can raise their feeling of being of value added for the process. Moreover, it is recommended that these actions include fruitful discussions and debates that lead them to realize how their insights influence policymaking, protect their rights or have a direct impact on them, being those the rationales identified by Head (2011) to underpin a greater involvement of youth in matters that affect them directly.

This work has its limitations. First, the size and length of the Barakaldo case study on co-creative policymaking presents limitations on the number of vulnerable young people engaged in the process, as well as in the scope of the data analysis it provides. Thus, it shows limitations of direct generalization, but it offers a more detailed analysis based on the case study which can stimulate reflections on how local urban institutions can influence the personal drivers for fighting against urban inequalities.

Second, even though the role of the facilitators is a key aspect to drive these processes as empowering and learning processes, the paper does not study this aspect. Thus, it is not the ambition of this paper to deepen in the role that they can play to build and drive these processes but rather to define the elements that in the light of the results of the empirical study presented in this paper, can be built across the process to consciously work toward an empowering and learning process for the young participants. However, the author acknowledges the role played by the facilitators in many aspects that influence the process, one of them being the element of reflexivity. Systematic reflection in every step of the process allowed to continuously reflect on whether young people were heading toward more knowledge and/or positive attitudes toward the topic; and to adjust the process to include new means and methods to seek its objective.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comité de Ética en Investigación de la Universidad de Deusto. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The research leading to this paper has received funding from the UPLIFT Project (H2020-UPLIFT Grant Agreement No. 870898).

The author is grateful to all the UPLIFT partners, and the local partners from Barakaldo including Eretza, the City Council and the young people from Barakaldo involved in the empirical study. Moreover, the author acknowledges the contribution of Claudia Icaran to the design of the research, the interpretation of results and the critical revision of the work. Their work and results are summarized in this paper.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2023.1098313/full#supplementary-material

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 35, 216–224. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225

Blakeslee, J. E., and Walker, J. S. (2018). Assessing the Meaningful Inclusion of Youth Voice in Policy and Practice: State of the Science. Portland, OR: Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures, Portland State University.

Brandsen, T., Steen, T., and Verschuere, B. (2018). “Co-creation and co-production in public services: urgent issues in practice and research,” in Co-production and Co-creation, eds T. Brandsen, T. Steen, and B. Verschuere (New York, NY: Routledge).

Bulkeley, H., Marvin, S., Palgan, Y. V., McCormick, K., Breitfuss-Loidl, M., Mai, L., et al. (2019). Urban living laboratories: conducting the experimental city? Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 26, 317–335. doi: 10.1177/0969776418787222

Checkoway, B., Pothukuchi, K., and Finn, J. (1995). Youth participation in community planning: what are the benefits? J. Plan. Educ. Res. 14, 134–139. doi: 10.1177/0739456X9501400206

Egdell, V., and McQuaid, R. (2016). Supporting disadvantaged young people into work: Insights from the capability approach. Soc. Policy Admin. 50, 1–18.

Elmqvist, T., Andersson, E., Frantzeskaki, N., McPhearson, T., Olsson, P., Gaffney, O., et al. (2019). Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2, 267–273. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0250-1

Frank, K. I. (2006). The potential of youth participation in planning. J. Plan. Literature 20, 351–371. doi: 10.1177/0885412205286016

Frantzeskaki, N., and Rok, A. (2018). Co-producing urban sustainability transitions knowledge with community, policy and science. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 29, 47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2018.08.001

Hajer, M., and Versteeg, W. (2019). Imagining the post-fossil city: why is it so difficult to think of new possible worlds? Territory Polit. Govern. 7, 122–134. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2018.1510339

Hart, R. A. (1992). Children's Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship. Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Center.

Head, B. W. (2011). Why not ask them? Mapping and promoting youth participation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 33, 541–547.

Hoekstra, J. S. C. M., and Gentili, M. (2021). Deliverable 4.2: Action Plans on the Co-creation Process: A Theoretical and Methodological Framework. Available online at: https://uplift-youth.eu/sites/default/files/upload/files/D4.2_Updated%20action%20plans.pdf (accessed January 11, 2022).

Hossain, M., Leminen, S., and Westerlund, M. (2019). A systematic review of living lab literature. J. Clean. Prod. 213, 976–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.257

IAP2 (2022). International Association for Public Participation. Available online at: https://www.iap2.org/ (accessed March 15, 2022).

Itten, A. V., Sherry-Brennan, F., Sundaram, A., Hoppe, T., and Devine-Wright, P. (2020). State-of-the-art Report for Co-creation Approaches and Practices With a Special Focus on the Sustainable Heating Transition: Shift Work Package 2 Deliverable 2.1.1. Province Zuid-Holland. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.22835.17440

Kemmis, S., and Wilkinson, M. (1998). Participatory action research and the study of practice, in Action Research in Practice: Partnerships for Social Justice in Education, eds B. Atweh, S. Kemmis, and P. Weeks (London: Routledge).

Kimhur, B. (2020). How to apply the capability approach to housing policy? Concepts, Theor. Challenges Housing Theory Soc. 37, 257–277. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2019.1706630

Kronsell, A., and Mukhtar-Landgren, D. (2018). Experimental governance: the role of municipalities in urban living labs. Eur. Plan. Stud. 26, 988–1007. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2018.1435631

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. J. Soc. Issues 2, 34–46 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x

Loewenson, R., Laurell, A. C., Hogstedt, C., D'Ambruoso, L., and Shroff, Z. (2014). Participatory Action Research in Health Systems: A Methods Reader. Harare: TARSC, AHPSR, WHO, IDRC Canada, EQUINET.

Lorenz, U. (2020). Co-creation of Benchmarking Processes: Urban Policies for Smart Specialization. San Sebastian, Cuadernos Orkestra Report number: ISSN 2340-7638 - 74/2020. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.10481.30568

Lorenz, U., and Icaran, C. (2022). Deliverable 3.2. Case Study Report. Barakaldo: UPLIFT deliverable. Available online at: https://uplift-youth.eu/sites/default/files/upload/files/%20case%20study%20report.pdf (accessed January 15, 2023).

Matti, C., Rissola, G., Martinez, P., Bontoux, L., Joval, J., Spalazzi, A., et al. (2022). Co-creation for policy: participatory methodologies to structure multi-stakeholder policymaking processes, in EUR 31056 EN, eds C. Matti and G. Rissola (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union).

Olshansky, E., Sacco, D., Braxter, B., Dodge, P., Hughes, E., Ondeck, M., et al. (2005). Participatory action research to understand and reduce health disparities. Nurs. Outlook 53, 121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.002

Ozer, E. J., and Douglas, L. (2013). The impact of participatory research on urban teens: an experimental evaluation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 51, 66–75. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9546-2

Robeyns, I. (2005). The capability approach: a theoretical survey. J. Hum. Dev. 6, 93–114. doi: 10.1080/146498805200034266

Robeyns, I. (2006). The capability approach in practice. J. Polit. Philos. 14, 351–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9760.2006.00263.x

Robeyns, I., and Byskov, F. (2021). “The capability approach,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed E. N. Zalta, Winter 2021 (Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University). Available online at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/capability-approach/

Torfing, J., Sørensen, E., and Røiseland, A. (2019). Transforming the public sector into an arena for co-creation: barriers, drivers, benefits, and ways forward. Adm. Soc. 51, 795–825. doi: 10.1177/0095399716680057

Treseder, P. (1997). Empowering Children & Young People: Promoting Involvement in Decision-Making. London: Save the Children.

United Nations (2016). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/11125

UPLIFT (2021). Deliverable 1.2 Inequality Concepts and Theories in the Post-Crisis Europe Summary of the Literature Review. Available online at: https://upliftyouth.eu/sites/default/files/upload/files/D12%20Inequality%20concepts%20revised_october%202021-web.pdf (accessed July 15, 2022).

Vladimirova, I., Lalov, A., and Pavlova, A. (2022). From Research Results to Innovative Solutions: Mapping National and Regional Programmes and Initiatives in R&I Valorization: Report on Dissemination and Exploitation Practices in Member States and Associated Countries. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi: 10.2777/777941

Volkert, J., and Schneider, F. (2011). The Application of the Capability Approach to High-income OECD Countries: A Preliminary Survey. Munich: CESifo, Center for Economic Studies, CES, Ifo Institute.

Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J., and Tummers, L. G. (2015). A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 17, 1333–1357. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2014.930505

Vromen, A., and Collin, P. (2010). Everyday youth participation? Contrasting views from Australian policymakers and young people. Young 18, 97–112. doi: 10.1177/110330880901800107

Keywords: co-creation, urban policymaking, youth, action research, capability approach

Citation: Lorenz U (2023) Enhancing young people's individual skills and knowledge. The case of vulnerable youth participating in co-creative policymaking in housing in the city of Barakaldo. Front. Sustain. Cities 5:1098313. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.1098313

Received: 14 November 2022; Accepted: 10 February 2023;

Published: 08 March 2023.

Edited by:

Tiit Tammaru, University of Tartu, EstoniaReviewed by:

Lorenzo De Vidovich, University of Trieste, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Lorenz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Usue Lorenz, dWxvcmVuekBvcmtlc3RyYS5kZXVzdG8uZXM=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.