- 1Department of Kinesiology, San José State University, San José, CA, United States

- 2Department of Sociology and Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, San José State University, San José, CA, United States

- 3Department of Public Health and Recreation, San José State University, San José, CA, United States

In Summer 2020, persistent public protest about racial injustice and police violence spurred conversations and action across the United States and the world about what community safety means and the various ways it can be achieved–particularly for diverse community members whose lives may be threatened under the status quo. In San José, California, this led in part to a community engaged research study on reimagining community safety–The People's Budget of San José. The project intended to inform justice policy reform in the city according to the perspectives and needs of residents. Through this community-academic partnership, 14 focus group discussions were held by community-based organizations where diverse groups of residents shared what community safety looked like to them, discussed what made them feel unsafe, learned about the city's budget, and identified how that budget reflects or is in opposition to their ideas about how to achieve safety. Utilizing a theoretical matrix that merges Capabilites Approach and Critical Race Theory and data were analyzed focusing on elements of community safety. Three themes came through the data: (1) basic human rights for vulnerable populations; (2) police, safety and sociocultural conditions; (3) space, race, and class within community safety. Findings from the study highlight the ongoing need to examine how communities perceive their own wellbeing and community safety exclusive of governmental authorities. We conclude with policy, practice, and research recommendations for how to deepen understandings of what “public safety” means in the eyes of residents and how it might be achieved in light of current politics.

Introduction

During the summer of 2020, civil unrest gripped cities across the United States (U.S.) and tensions with law enforcement peaked during what would be one of the largest public protest movements in recent history. The tragic death of George Floyd at the hands of Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the brutal killing of Breonna Taylor in her Louisville home catalyzed a reckoning regarding racial justice in America. The resurgent #BlackLivesMatter social movement demanded public attention regarding safety and policing across the country. In diverse public demonstrations across the country, people marched to bring attention to normalized police violence—a burden disproportionately borne by the nation's poor, Black, Latinx, indigenous, and gender non-conforming populations. Though much of the public protest has since subsided, these demonstrations inspired new approaches to achieving community safety, broadly known as non-police alternatives. The present study aimed to understand community perspectives on safety, policing and how city budgets should address complex social problems. While the focus of our research was on the diverse, large city of San José, California, the approach and lessons learned are pertinent to researchers studying urban equity and practitioners aiming to enhance social inclusion across the country.

The need for scholarly attention to public safety and policing is timely and imperative as cities experience urbanization, gentrification, and increasing income inequality (see Austin et al., 2002; Leverentz et al., 2018). Marginalized populations such as the unhoused, individuals facing mental health challenges, and those living in poverty are often subjected to discriminatory practices (Austin et al., 2002). By examining how community members conceptualize public safety, how policing contributes to (or undermines) safety, and how a city's total budget realizes public safety, communities can reimagine how safety can be organized and practiced (Owens and Ba, 2021). The present study illuminates the perspectives and experiences of diverse community residents, attending to their conceptions of what safety could look like within a broader social project to reimagine public safety.

In San José, California, the protests of 2020 led to a community-engaged research study on reimagining community safety and policing in the heart of Silicon Valley. The People's Budget of San José (PBSJ), initiated by the Human Rights Institute at San José State University and Sacred Heart Community Services, is a collaborative research study led by an interdisciplinary academic team and community organizers. The purpose of the PBSJ was to unpack the complex notions of community and policing where there was a deliberate emphasis on community members' agency in defining and applying their own constructions of safety. This paper is a scholarly analysis of the qualitative data from the initial year of this multi-disciplinary study. Through a community-academic partnership, a series of focus group discussions were held by community-based organizations where diverse groups of residents shared what community safety looked like to them, discussed what made them feel unsafe, learned about the city's budget, and identified how that budget reflects or is in opposition to their ideas about how to achieve safety. Among other things, this process yielded a nuanced depiction of the role San José police have in promoting and protecting communal ideals of safety.

Importantly, this study presents findings derived from discussions by community members in San José regarding how they felt about community safety, the police's role in promoting this safety and what other alternatives to community safety are possible. Moreover, findings from this study have the possibility of informing public policy and being presented to elected officials to better utilize city finances in more equitable ways that may divest from the large sums provided to the police. For example, as we will discuss later on, divestment of funds from policing can be used to promote housing, a basic human right, which is an essential component of feeling safe (see Nussbaum, 2011) and this is more pertinent among communities of color. In San José, concerns regarding city budget spending and public safety stem from the rising costs of living where income inequality has grown consistently over 25 years (California Budget Policy Center, 2022) and poverty is geographically clustered (e.g., East San José) resulting in dynamics of race potentially playing a role on safety (Wheelock et al., 2019). San José is considered by many real estate analysts the most difficult place in the country to purchase a home, due to astronomical price and a mere four real estate listings (“for sale”) per 1,000 residents. Median home prices remain among the highest in the nation at $1.08 M (Aug. 2020), nearly twice the median price for California and over 3 times that for the U.S (Redfin, 2022). Considering these facts, the PBSJ was concerned with how people in San José perceived public safety and the role authorities have in promoting such safety. As such, safety is more than a feeling; it connects to having basic wants and needs met and livelihoods promoted. Of central significance to this study is how people from San José both perceived their safety and how they thought safety could be pursued in the future in a manner that is not inclusive of governmental authorities (e.g., police). This is important to understand as there are ongoing discussions around the USA about how to better hold the police accountable and if there are alternative ways to promote safety (Owens and Ba, 2021). Hence, this important research draws from emprical data to discuss how communities in a large metropolitan city perceive safety.

Framing the study on community safety in San José is an intersectional collection of theories that includes Martha Nussbaum's (2011) Capabilities Approach and Critical Race Theory (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991; Matsuda, 1991; Delgado, 1995; Solórzano, 1997, 1998; Yosso, 2005). Together these paradigms form the theoretical framework we used to understand and interpret residents' experiences of and perspectives on community safety. We found that residents' constructions of community safety implicitly and explicitly engaged notions of human rights and that race, gender, and socio-economic status influence one's perspectives on community safety, and affect one's experience (and interpretation of those experiences) with police and the broader criminal justice system. From this framework, and within the specific context of San José, we provide detailed insight into perspectives on community safety and policing across this incredibly diverse city.

Review of literature

Recent literature has examined a myriad of aspects related to community perceptions on public safety, policing and city expenses related to the two (Reisig and Giacomazzi, 1998; Scheider et al., 2003; Shukla et al., 2019). The ways in which communities understand their own safety in relation to police provides insight into how people perceive their own safety and if they are confident in how police interact with communal needs. Nofziger and Williams (2005) conducted a study in the Midwest that examined public perceptions on policing as it relates to community safety. Their study complicated other research because it was conducted in a midwestern setting where there was favorable confidence in policing. It is important to note then that perceptions of policing can and do differ among different geographic and demographic boundaries. And this is often exacerbated when considering intersections of race, gender, age and socioeconomic status. Gonyea et al. (2018) examined neighborhood safety among older minority residents in subsidized housing. The study saw that the participants perceived safety was rooted in their emotions and feelings, such as being depressed and that a positive way to promote positive emotions was to be socially connected and to possess a stronger sense of belonging. The sense of safety according to Gonyea et al. (2018) among elder minority participants was not a physical sense of safety, but an innate sense rooted in connectedness. Hence, it is important to consider how safety manifests differently between different communities that come from different demographic and geographic backgrounds, and more crucial how the built environment enforces ideas of safety.

Lewis et al. (2016) and Leverentz et al. (2018) conducted studies that explored constructions of community safety across urban neighborhoods in Boston and San Antonio, respectively. Both studies indicate that a sense of community safety is derived from social ties among neighbors and that safety was informed by race, education, employment, and the length a person has lived in a particular location. Community safety and connectivity between members of a community can coalesce if there are similarities among them. It is important to consider in which ways communities foster their own sense of safety that is not supported by city governments or police. Safety can thus be both an objective and subjective process (Austin et al., 2002) especially as neighborhood conditions differ and continually change.

How people feel in their surroundings or how people move within their communities are topics that require critical attention. Oidjarv (2018) compared two different neighborhoods perceptions of the built environment and social capital in relation to perceived safety. Focusing on how the built environment is engineered, the research acknowledges that walkability and how people move through space is fundamental to safety. Moreover, the ability to move freely and safely created opportunities for community members to be sociable which also influenced attitudes pertaining to community safety. Previous research has discussed how infrastructure (Wilcox et al., 2004), the effect of zoning policies on crime (Anderson et al., 2013), and how changes to the built environment impact people's perceptions of safety (Foster et al., 2012). The physical environment that promotes access, street connectivity, and walkability often contributes to objective notions of safety (Leslie et al., 2005). Public spaces, and importantly how people move through them, is essential to their experiences of safety. If people are able to move freely without being threatened (by both other community members and police) in such a way that reinforces positive interactions then a collegial experience could be formulated. Critical attention is needed to how the physical and built environment are implicated in reinforcing or dissuading perceptions of community safety. Further attention will help illustrate how community safety is perceived and can be approached in consideration of communal expectations.

Theoretical framework

Drawing on the interdisciplinary expertise of the academic partners on this collaborative study, we identified two synergistic theories through which we interpreted the qualitative data: Capabilities Approach and Critical Race Theory. Together, these form a theoretical framework to highlight how notions of human rights, equitable economic development, and racialized discourses are reflected in residents' constructions of community safety and policing in San José, California.

Capabilities Approach

Nussbaum's (2011) Capabilities Approach (CA), built on of Sen's (1999) Capability Approach, which focused on the potential of a person's development. Sen defined “capability” as the “alternative combinations of functionings from which a person can choose. Thus, the notion of capability is essentially one of freedom - the range of options a person has in deciding what kind of life to lead” (Sen, 1999, p. 10–11). Both Sen (1999) and Nussbaum (2011) are concerned with social justice as a way to protect people's choices and their ability to enjoy freedom to make decisions for themselves. More important though are the basic needs that people need in order to enjoy their freedoms. For example, Nussbaum (2011) reasons that social justice in the CA is therefore assessed based on whether people are, or are not, afforded freedoms and opportunities from which to dictate their livelihood. That is, people ought to be provided with opportunities to develop and live their own lives. Nussbaum aims to establish criteria through which to create a minimum threshold of capabilities that will enable individuals to live lives of human dignity. The criteria for people are in line with the basic needs of all human beings.

The need and opportunity to pursue basic human rights is predicated within a list of what Nussbaum (2011) calls Central Capabilities. For the purpose of this paper, we align basic human rights with these Central Capabilities. As such, what warrants considerable attention are whether and how the Central Capabilities are being met, and are protected, neglected, or obstructed in relation to ideas of community safety. The list of Central Capabilities includes ten broad yet distinct capabilities. They are:

(1) Life—the ability to live to the end of a natural human life; (2) Bodily Health—the ability to have good health such as adequate nourishment; (3) Bodily Integrity—the ability to move freely and be secure against all forms of violence; (4) Senses, Imagination and Thought—the ability to use the senses to do things that are truly human and to have pleasurable experiences; (5) Emotions—the ability to have attachment to people and things outside ourselves and to not have one's emotions stunted; (6) Practical Reasons—the ability to critically engage and be thoughtful of one's situations; (7) Affiliation—the ability to live with others, engage in various social actions, and to have self-respect and non-humiliation; (8) Other species—the ability to live and have concern for other animals, plants, and nature; (9) Play—the ability to laugh, play, and enjoy recreational activities; and (10) Control over one's environment—the ability to participate in political decisions and the ability to own property and have rights (Nussbaum, 2011, p. 33–34).

While these capabilities are distinct, there are connections and synergies across the capabilities. Further, note the connection to fundamental human rights ratified by the United States, such as the right to life [International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Article 6], liberty and security of person (ICCPR Article 9), freedom of movement (ICCPR Article 12), freedom of thought, conscience, and religion (ICCPR Article 18), freedom of opinion and expression (ICCPR Article 19), and freedom of association (ICCPR Article 22) (UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966). The Capabilities Approach provides insight into how human rights are being promoted, protected, or neglected in how approaches to community safety in San José impact the opportunity structures through which people do or do not enjoy fundamental dignities in daily life.

Critical Race Theory

Following from the Capabilities Approach and conversations around human rights, insights from Critical Race Theory (CRT) (Crenshaw, 1989; Bell, 1992; Russell, 1992) provide a framework that premises race and racism as central and fundamental to how US society functions. CRT emerged from scholars of critical legal studies (CLS) who argued that CLS was not adequately addressing race and racism as an endemic part of the legal structure (Crenshaw, 1989; Delgado, 1995; Ladson-Billings and Tate, 1995). CRT incorporates theoretical underpinnings from Black feminist thought, ethnic studies, sociology, history, abolition theorists, and other theoretical traditions (Collins, 1986; Delgado, 1988, 1995; Crenshaw, 1989, 1991; Bell, 1992; Delgado and Stefancic, 2001; Solórzano and Yosso, 2001; Yosso, 2005; Lorde, 2021). CRT also highlights other forms of structural power and marginalization and can thus also be employed to study interlocking systems of inequity and injustice beyond race including those marked by gender, socioeconomic status, sexuality, and accent (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991; Valdes et al., 2002). CRT thus offers a lens through which to examine how experiences and realization of human rights are affected by social position marked by race, gender, sexuality, ability, and socioeconomic status.

Our theoretical framework for this study was informed by the five themes or core tenets of CRT (Solórzano, 1997, p. 6–7; Solórzano, 1998, p. 122–123; Yosso, 2005, p. 73–74):

(1) Intersectionality of race with other forms of oppression

(2) Challenges the dominant ideology

(3) Commitment to social justice

(4) Centrality of experiential knowledge

(5) The interdisciplinary perspective.

The first CRT tenet centers on the endemic nature of racism within the United States legal system and society at large and the intersectionality of racism with other forms of oppression (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991; Barnes, 1990; Bell, 1992; Russell, 1992). The second tenet challenges dominant ideologies of equal opportunity, color-blindness, gender neutrality, race neutrality, and meritocracy (Bell, 1987; Solórzano, 1997, 1998; Yosso, 2005). CRT is committed to social justice, tenet three, offering a transformative response to racial, gender, class, and other forms of oppression (Freire, 1973; Matsuda, 1991; Solórzano and Bernal, 2001; Freire et al., 2014). Fourth, CRT argues that experiential knowledge of people of color is legitimate, valid, and central to any understanding of racism and other forms of oppression in the United States and highlights the importance of storytelling, family histories, and testimonios (Bell, 1987, 1992; Delgado, 1988; Solórzano and Yosso, 2001; Yosso, 2005). The fifth tenet argues in order to understand racism and other forms of oppression we must do so from a transdisciplinary matrix drawing from ethnic studies, feminist studies, film, sociology, public health, and other fields to analyze race and racism within past and current contexts. As such, applying a CRT framework offers a holistic lens to examine how residents in San José understand public safety through their lived realities, and also allows for ways to unpack how intersections are implicated within human rights.

The five tenets of CRT were foundational to our research, yet we found Crenshaw's theory of intersectionality, which is the core of tenet one, particularly helpful in developing our shared analytic framework. Intersectionality infuses complexity into understandings of social positions and power, adding multidimensionality to our efforts to mitigate discrimination. Black feminist scholars developed the theory of intersectionality to explain how inhabiting a position at the nexus of multiple inequities (e.g., race, gender, and class) can compound the negative effects of marginalization (Crenshaw, 1989). The effects are not simply cumulative or additive but result in qualitatively different social experiences. Within the field of public health, intersectional scholars have critiqued the simplistic analytic approaches to documenting health disparities, as well as the flattening of the construct of intersectionality to simply mean multiple identities rather than retain its focus on power, especially with regards to the impacts of policing (Bauer et al., 2021; Bowleg, 2021). Crucially, as Bowleg writes, “Intersectionality is fundamentally a resistance project” and is oriented to praxis (2021).

Research and community context

San José is one of the ten most populous cities in the United States, the third-largest in California. Demographically, it is quite different from other large cities, with over a third of the population identifying as Asian and around a quarter each identifying as Hispanic and White. The population of Black residents, just under 3%, is significantly smaller than in other large cities in California and nationally. Nearly 60% of residents speak a language other than English at home (compared to 22% nationally) and 40% of the residents were born outside of the United States (Datausa.io). Within the Asian population, there are large Vietnamese, Filipinx, and Chinese communities, each with their distinct histories and experiences in the region. While the median household income is $115,000, this figure masks wide income disparities across neighborhood and racial groups (Wolfe, 2022).

The People's Budget of San José Study was co-created by the Human Rights Institute (HRI) at San José State University and Sacred Heart Community Services (SHCS). The HRI is a research and policy institute committed to community-partnered praxis to achieve social change. SHCS is a community-based organization providing essential services, community organizing and advocacy in the region. This collaboration recognized the timely research led by social movements in cities ranging from Los Angeles to Nashville during the summer of 2020 that surveyed residents to capture their perspectives on how cities should fund public safety. These surveys, often done quickly and exclusively online, showed communities supported divesting from police and law enforcement and investing city funding in community-led alternatives (Nashville People's Budget Coalition; People's Budget LA).

In our local context, we felt that such a survey was unlikely to capture the range of perspectives and experiences in the region and would have limited credibility as an advocacy tool. Instead, we envisioned the People's Budget of San José Study as a long-term project to build and strengthen racial justice coalitions across the community, educate the community about the city's current budget and spending practices, better understand the diverse range of experiences people have of community safety and with policing in the city, and ascertain the level of support for alternative strategies to achieve safety, especially for residents who have been most impacted by policing in their communities.

In the first year of the study, we focused on coalition building and qualitative research to better understand community members' perspectives and experiences. This then informed the development of a city-wide survey of residents to assess experiences of and attitudes toward policing and community safety. Both of these community-partnered research initiatives are informing a city-convened advisory board on Reimagining Public Safety, which is engaged in further work to develop recommendations for the city to enhance community safety. The present paper shares the findings from the qualitative research conducted during the first year of the People's Budget of San José Study, making connections to scholarship on social inclusion, human rights, and community safety in the context of sustainable cities.

In naming this study the People's Budget of San José, we pay tribute to decades of scholarship and activism that seeks to build city budgets in a participatory manner in order to reflect the vision and values of the residents who live there (de Sousa Santos, 1998; Souza, 2001; Goncalves, 2014). Participatory budgeting, a form of participatory democratic practice with roots in Brazil, has been used throughout the world to give residents greater voice over how public monies are spent (Su, 2017). This study takes as a given that people have a right to understand the allocation of public funding and have experiential expertise to make recommendations on where to spend more resources and where to spend fewer resources. In addition, stemming from our theoretical framework, this study sought to explicitly engage with marginalized communities and community members whose experiences with policing might be less common, but are critical to understand in order to improve social justice outcomes.

Methods

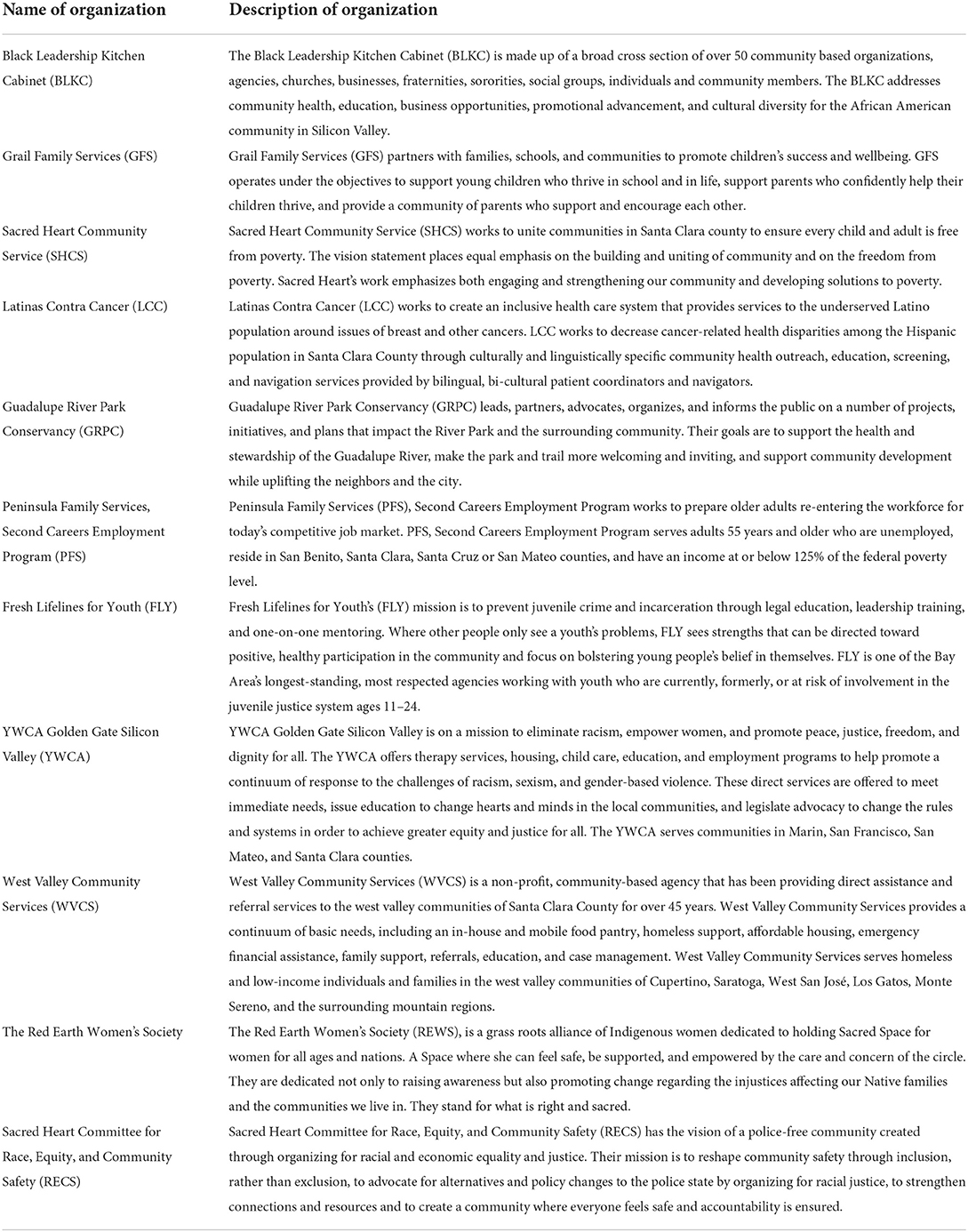

In the first several months of the PBSJ collaboration, academic and community partners collaboratively developed a focus group discussion guide to support local organizations within a broad racial justice collaboration to hold focus groups with their constituents on community safety and policing (see Table 1). Focus group discussions were utilized for the methods ability to gain information about views and experiences from a specific group of individuals (Gibbs, 1997). The opportunity for community groups and members from San José to interact with one another in a way that shared understandings on public safety and community relationships can arise was beneficial for the PBSJ project. Working with community partners allowed for focus groups to be demographically similar, thus potentially creating a space for honest discussion about attitudes, feelings, and experiences with safety, policing and community relationships.

The focus groups were carried out with the intention to inform the Re-imagining Public Safety Community Advisory Committee, a community advisory board convened by the City Council and tasked with re-envisioning criminal justice and police reform in San José and reporting back to the city council. In addition, these focus groups would inform the creation of a community survey to quantitatively assess experiences of safety and policing and opinions on the city budget (which is part of the larger PBSJ study). Questions asked during the focus groups were broad and open ended, and mainly focused on thoughts on public safety, the San José city budget, and thoughts on community relationships. For example, questions and statements asked were “What does safety look like?…,” “What makes you feel less safe?” “Do you think the city spends enough money on the things that make you feel safe?” What about spending to prevent or change the things that make you feel unsafe?” From these questions focus group facilitators nurtured conversations among participants. These data inform this specific study. A total of 12 focus group discussions were conducted using the guide. Focus groups were conducted by members of the research team, as well as community partners in San José. Data were gathered by focus group facilitators in the form of hand-written notes which were uploaded onto a confidential shared drive that only the research team had access to.

Additional research was carried out by the SHCS Race, Equity, and Community Safety committee: a group of multi-racial community leaders working together for equity in public decisions about budgeting, program and service delivery, and alternatives to current systems that harm communities of color. This group of volunteer community members adapted the focus group guide to elicit more stories of people's lived experiences, and used this guide to conduct seven listening sessions with community residents. For each focus group and listening session, the academic team received notes stripped of personal identifiers and copies of an interactive “Jamboard,” where conversation participants could write virtual sticky notes contributing their ideas to specific prompting questions.

In addition to these primary sources of data, two members of the research team (Dao and de Bourbon) worked with specific groups that were underrepresented in the focus group discussions and listening session data to gather more information on community safety and policing. In Summer 2021, Dao interviewed and had informal discussions with Vietnamese community members at Vietnamese-owned establishments in San José. Through his conversations, he spoke to 12 people about their perceptions of safety and the police, while also observing how people interact with each other in public spaces. De Bourbon was separately engaged in research in partnership with the Red Earth Women's Society on Native women's experiences of violence and had conducted focus groups covering similar questions to those articulated in the PBSJ focus group guide. She was thus able to bring these data on Native women's perspectives on community safety into the PBSJ study. These two additional data collection activities were approavhed by the SJSU Institutional Review Board. Thus, the full dataset included notes and Jamboard responses from 12 focus groups discussions, seven listening sessions, interviews and observations with Vietnamese community members, and sections of focus group responses from Native women.

Data analysis

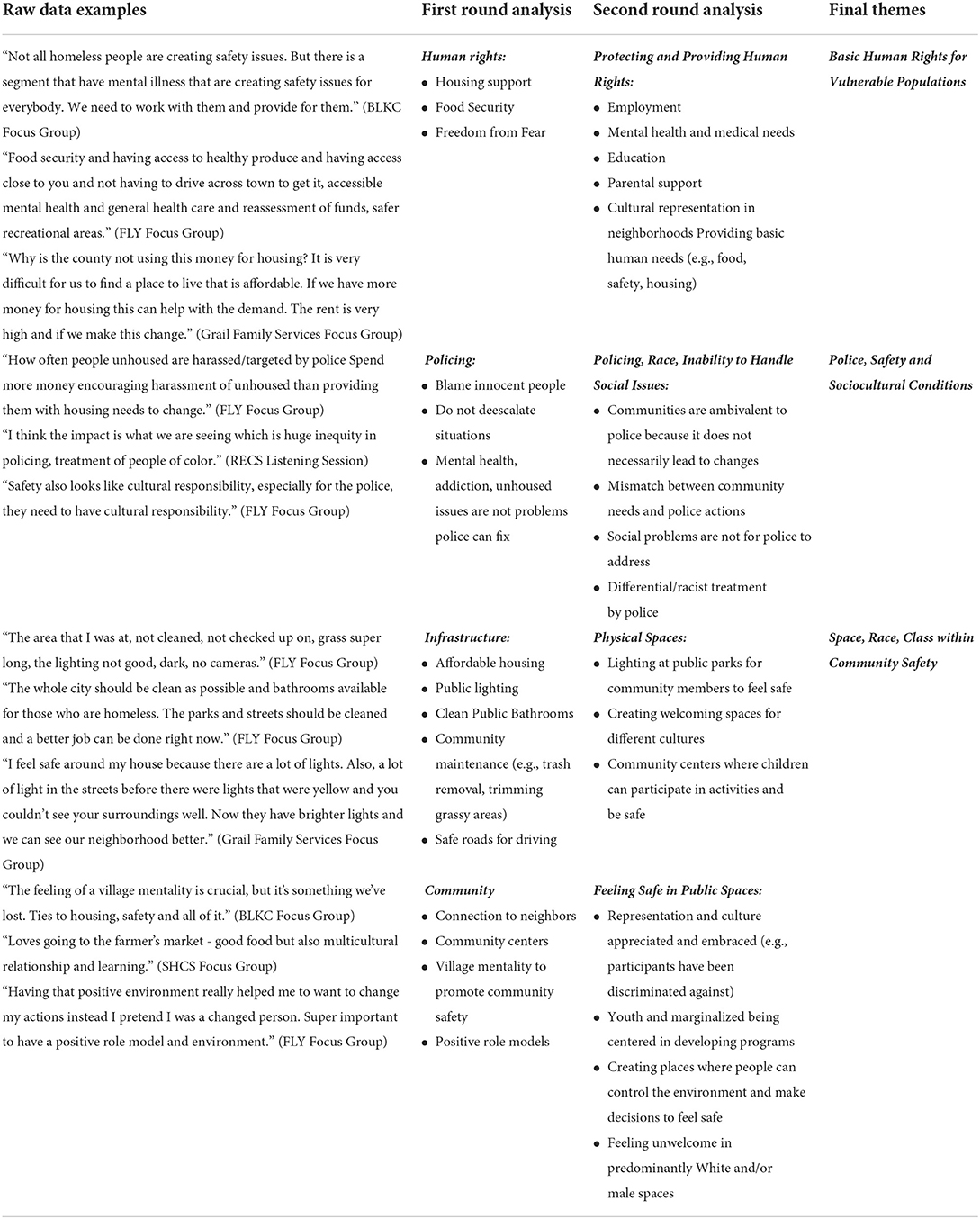

The academic team thematically analyzed the data, using an iterative process (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Each of the academic partners first individually coded the data into a set of themes. After our initial independent analysis, we convened as a team to discuss what each member found and identify similarities and areas of insights that were different from what was perceived by the others. We met several times, with time between meetings for each of us to re-read the data and consider alternative interpretations. Our team discussions were lengthy, lasting roughly 2 h each time we met. Our analytic conversations were informed by the tenets of CRT and we assumed the we each brought different experiential knowledge shaped by our race, class, gender, and ethnic identities. Thus, we made space for differences in interpretation and listened deeply to each other. After the academic team identified a core set of themes, we shared these themes and sub-themes with the community research partners for feedback. After two data analysis meetings that lasted roughly 2 h each, we came to agreement on the themes that came from the data. Through ongoing conversation, we achieved consensus on the essential themes and interpretations of the data supporting these themes. The data coding process is represented in Table 2 which briefly outlines our analysis, inclusive of sample notes and data examples. In the next section we present these findings.

Results from the focus groups were also presented at an online community forum in November 2021 at the San José State University Transforming Communities conference. This conference is a university and city-wide venture that is designed to catalyze change in the community with a focus on creating a more racially just and equitable San José. As such, the authors presented in a community forum and invited community partners and participants from the focus groups to attend the forum in order to share their thoughts on the data analysis. The opportunity to share the results and have input from the community highlighted the importance of PBSJ and the limitations. Thus, the forum served as a method of triangulation via member checking (Creswell and Miller, 2000) where community members that attended were able to present comments and concerns and the research team made final analytic decisions based on these additional comments.

Results

There were three major themes in the qualitative research on community residents' perspectives on safety, policing, and the city budget. The first theme pertained to basic human rights for vulnerable populations. Many participants identified a glaring gap in the provision and protection of basic human rights for the most vulnerable; this idea resonated in all communities. Second, when examining community safety, people felt that vexing social issues like mental health, homelessness, and community safety cannot be solved or addressed by police or other law enforcement agencies. The third theme examines how peoples' race, gender, and social class informs their experiences of safety in community spaces, and perspectives on law enforcement and community safety more broadly.

Basic human rights for vulnerable populations

There was a shared recognition that the basic human rights of all members of the community were not being met and a yearning for San José to do better at meeting these needs. Specifically, participants who felt that their own basic human needs were met wanted people who are the most vulnerable in their community to have their basic needs met, too. Participants expressed particular concern for community members who were homeless, struggling with mental health issues, and/or addiction. Participants connected community safety directly to the city meeting the needs of homeless community members. In this way, there are two pertinent subthemes that detail the human rights and needs that were not being met in San José: housing and mental health.

Housing

Housing and homelessness were topics that many participants raised. The idea of safety was implicated in the thought that the basic human right to adequate shelter was something that needed to be provided and protected. Participants shared that they felt the City of San José can and should do more to support adequate housing; an issue that is exacerbated by vast inequalities in household income. A participant from a youth services organization said: “They need to spend more on housing and that is a safety net for everyone.” (FLY Focus Group 2). A participant from an adult-serving anti-poverty organization noted when discussing what the city should spend money on: “Money to build homes for the homeless.” (PFS Focus Group).

Importantly, while some groups included participants who had themselves experienced homelessness and others included residents who were well-off and had never themselves experienced homelessness, housing for all residents was connected to experiences of safety across all groups. One participant from a Black leadership organization expressed:

“But at the end of the day, housing is a basic need and I think all these issues, you know, that our community members are facing would be solved...Because you're on the right track, housing for everybody and safety for everybody would cause people to have less behaviors that are quote, unquote dangerous.” (BLKC Focus Group)

Thus, housing was spoken of not just as a basic right itself that should be available to all in the community, but also a pathway to solving some of the other problems that undermine people's sense of safety.

Health

Health, and specific resources to support people with mental health issues, was the next prominent topic when discussing basic human rights. Participants were keenly aware that people living in precarious conditions may be facing mental health challenges without receiving mental health support. Participants were concerned about mental health and wanted the city to spend more funding to addressing this issue, especially as it connected to homelessness, exemplified in the following quotes:

“Not all homeless people are creating safety issues. But there is a segment that have mental illness that are creating safety issues for everybody. We need to work with them and provide for them.” (BLKC Focus Group)

“Put money into helping homeless community members with mental health issues.” (RECS Listening Session 3)

Participants also identified basic human needs like food security and job security as critical to their perspective of what it means to have safety in their community. The connection between physical safety and the safety of having basic human needs met was made explicit by several participants, as captured in the following two quotes:

“Food security and having access to healthy produce and having access close to you and not having to drive across town to get it, accessible mental health and general health care and reassessment of funds, safer recreational areas.” (FLY Focus Group 2)

“Security also is job security. That our community has houses and rents that are affordable and have communities for our children to have higher success and activities.” (GFS Focus Group)

In this manner, participants explicitly linked their sense of safety and security to not just having their own fundamental capabilities met, but knowing that all community members had these needs met as well.

Police, safety, and sociocultural conditions

The second theme that arose from the data was a critical discussion about how complex social problems should not be solved by police or law enforcement. While there was disagreement about the role of the police in San José, there was agreement that the police were not able to solve social problems such as homelessness, mental health crises, addiction, and racism. Almost all groups expressed support for non-police approaches to solving these complex problems. Considering the perceived inability of police and law enforcement to address the aforementioned social issues two particular sub-themes arose in relation to the policing of complex social problems.

Distrust of police tools to create safety

The ways in which police and law enforcement approach social issues were seen as inadequate and improper. Participants expressed their overall dissatisfaction with responses from San José Police Department due to their lack of tools and knowledge to engage with homelessness, mental health, or addiction. The police were in fact causing more distress and harm when called to handle problems.

“[Last year, there was] a homeless man in the neighborhood, people wanted to get indoors due to the fires. I think he and others were squatting, I saw 4 [police] SUVs and brought out the man and arrested him. I felt powerless, no one's living in that house. I don't think he did anything wrong.” (RECS Listening Session 2)

Several participants felt that police were unable to create safety and instead created harm.

“I'm also not happy how they [the police] respond to our houseless neighbors who they harass and humiliate and belittle. I personally don't feel they create safety in our community.” (RECS Listening Session 1)

“Heavy police presence in our neighborhood and both the police actions in this neighborhood and the larger context, make me view police as contributing to danger and risk of harm.” (SHCS Focus Group 2)

As described in the first theme, participants wanted solutions to problems they were seeing in the community regarding homelessness and mental health crises. However, they felt that when police attempted to solve these problems, their “solutions” created more harm, leaving people feeling less safe.

SJPD lack racial and cultural knowledge

Several participants noted an overall lack of racial and cultural knowledge among police. Participants from ethnic enclaves such as East San José voiced how SJPD lacked racial and cultural knowledge of their communities resulting in poor interaction with police in their communities. This was particularly aggravating for participants when police misinterpreted behavior as dangerous or violent, when in reality this behavior was culturally acceptable (e.g., drinking heavily or speaking loudly). Participants were concerned that their community realities were under scrutiny, and, in turn, resulted in police taking unnecessary actions. As two participants expressed:

“I am upset because all of my life I called the police to help and they are assholes.... What are you getting trained on? Customer service? Deescalate situation? Killing people?” (FLY Focus Group 2)

“I'm concerned about walking around with my kids and police addressing problems incorrectly.” (BLKC Focus Group)

One of the Vietnamese men interviewed by Dr. Dao described his negative experiences with the police. The person explained that he is profiled by the police due to the visible tattoos on his body. Describing his experiences, he discussed how police officers will see his tattoos, and, in turn, will create an issue to “try to hurt or kill you.” On the other hand, some Vietnamese community members said they felt that the police did not necessarily view them as possible threats because of societally defined stereotypes and social discourses.

“I have not had a lot of encounters [with police]... Asian people have not had to experience the brutality of the police. They assume that we are nice - have no weapons.” (RECS Listening Session 2)

Participants drew not only from their experiences in San José, but also their experiences with police in other places they have lived to inform their perspectives on policing. For example, a Latina participant noted “I came from a country where you see a lot of gangs and social delinquent groups and the police presence made me feel safer” (LCC Focus Group). But when provided information about the police budget, the same participant felt dismayed: “It is sad to know that there is enough security funded yet it is still unsafe” (LCC Focus Group). The lack of cultural awareness and impacts of stereotyping have created a complex relationship between communities and the police.

Space, race, and class within community safety

The final theme focused on intersectional issues of class and race, and how the unsettling reality of white supremacy impacts people's feelings of safety.

Space and infrastructure

Participants discussed how racial dynamics encoded in the physical environment affected their experiences and feelings of safety. There were specific grocery stores, public parks, and neighborhoods that were reported to be unwelcoming or off limits to many participants. While several participants described experiences of being followed by security guards or being stopped by police without justification in spaces like these, other participants did not share specific triggering instances of overt hostility but identified spaces as “white spaces.” One participant shared that being in “fancy grocery stores like Whole Foods or Trader Joes” made them feel unsafe, noting that “police are gate-keepers at Whole Foods” (YWCA Focus Group 1). Another participant shared, “White dominated spaces are where I do not feel safe and do not feel welcomed. If there are no BIPOC people there it makes me feel unsafe and unwelcomed” (FLY Focus Group).

Across several conversations, participants reported that they would feel safer with better lighting, well-maintained streets, and cleaner public spaces. Notably, the most comments about the need for improved physical infrastructure to promote safety came from areas of the city that are predominantly poorer, have fewer resources and are often home to many Latinx and Southeast Asian communities (e.g., South and East San José). Participants described these improvements as simple, straightforward, and needing to be made in an equitable fashion, as exemplified in the following quote:

“50 million [dollars] to spend, super simple but having lights on our streets since some neighborhoods are very dark and can't see anything or lots of trees in the way. We need more proper lighting and open spaces so there are no hidden spots.” (FLY Focus Group 2)

While there are some investments in the built environment like lighting and maintaining streets that will improve safety for all, the physical environment is also influenced by social power. The physical environment is racialized, gendered, and impacted by socioeconomic factors, making some participants unsafe while others are protected in these spaces.

Social cohesion in communities of color

While some participants voiced their uneasiness in predominantly white spaces, there was a common yearning for cohesion and connectedness in their own communities. Many participants expressed that the feeling of safety can be built from within and not provided for by police, by people working together to build authentic relationships among neighbors to protect each other. Safety is thus a relational process produced by the people who make up a community. As one participant stated:

The word trust and tranquility. It is true that in our home origin that our children would feel safe. However, here in East San José they don't feel safe. I would like my child to go to the liquor store at the corner, but they won't feel safe because we don't know our neighbors. There is no communication between our neighbors. (GFS Focus Group)

They [Riverside] had a community center and they had a corner store where everybody gathered. Everyone knew each other's name. You had that village kind of feeling. That everyone was looking out for each other, everyone played sports together, everybody knew each other's grandmother and there was a sense of safety. There was a sense of community because of knowing each other and bonding and being able to connect with each other. We don't necessarily have that here in San José. (BLKC Focus Group)

As the quotations highlight, community safety is a process that people must engage in and be committed to building together. In conversations with Vietnamese men, two people said that the culture within the Vietnamese community is centered around taking care of those around them. In this way, there are cultural elements that promote community safety that may not be inclusive of non-Vietnamese community members. This is consistent with the calls by Native women to have Native spaces to promote community safety. Sociocultural dimensions warrant more attention in conceptualizing community safety.

In some focus groups, specific suggestions for how to build cross-cultural connections were made, such as investing in afterschool programs and community-based parenting classes and building community created spaces like a maker space and tool lending library. As one participant described, connections can be made by:

A street that is blocked off with tables in the street and you can bring food to a common table. You can sit with people you've never met before and start a conversation. Feel a sense of community. You can start to realize they are your neighbors. (SHCS Focus Group 1)

The focus group discussions and interviews highlighted that community safety is underpinned by one's relationship to physical spaces and the dominant, often unnamed, culture of those spaces. Safety is thus not something that can simply be provided but something that is created and maintained by people.

Discussion

The PBSJ project provided insight into how people of San José understand community safety and how they perceive the role of policing in supporting this safety. The analysis highlighted how community safety was tied to the provision and protection of basic human rights and experienced in an embodied way connected to identity and power. Consistent with other literature, we found that depending on the physical environment and city structure (Leverentz et al., 2018), cultural makeup (Gonyea et al., 2018), and overall feelings of safety (Leslie et al., 2005), people have different perceptions and experiences that speak to what they believe safety is or can be. In this paper we draw on these notions from previous literature, and in doing so, further research on how communities contextualize safety. Moreover, research in diverse settings, from Boston to San Antonio, suggest that community residents' sense of safety is connected not just to experiences of policing but to the social ties among neighbors (Austin et al., 2002; Lewis et al., 2016; Leverentz et al., 2018). Research that has examined perceptions and stereotypes associated with crime (Leverentz et al., 2018), how inner-city communities understand their own safety and community connectedness (Lewis et al., 2016) and citizens' reactions to tough policing (Ratcliffe et al., 2015). Our research in San José has highlighted similar perceptions regarding public safety, policing and city budget spending.

Aligned with Nussbaum's (2011) Capabilities Approach, human rights become necessities that help individuals develop throughout their lives. Community members in our study explained that it was through securing basic human rights for all members of the community that a community is experienced as safe. This research highlights the importance of providing and protecting human rights across all San José communities. For example, returning back to housing, Nussbaum (2011) couches it in the Central Capability to maintain bodily health, and as something that must be secured at a minimum threshold for all citizens. Bodily health consists of, “being able to have good health, including reproductive health; to be adequately nourished; to have adequate shelter” (Nussbaum, 2011, p. 33). Housing, thus, is an essential component of one's livelihood and safety. Also aligned with the Central Capability of bodily health, mental and physical health can be seen through the Central Capability of senses, imagination and thought which include, “to do things in a ‘truly human' way...a way informed and cultivated by an adequate education, including, but by no means limited to, literacy and basic mathematical and scientific reasoning” (Nussbaum, 2011, p. 33). San José is not perceived by participants as meeting the bodily health needs community members.

CRT informs the racial and sociocultural findings of the study. It is important to recognize that community safety is an embodied feeling impacted by one's identity and social position. In line with CRT (Crenshaw, 1989; Valdes et al., 2002), participants had divergent experiences in San José that were impacted by factors such as skin color, race, ethnicity, gender, and social class. Framing the analysis of human rights with CRT, particularly intersectionality, highlighted how issues of race, gender, and class are implicated in how community safety is experienced by community members.

Examining policies and city regulations through the lens of CRT and in connection to the health and safety of communities of color is revealing and potentially transformative (Ingram et al., 2020). Focus group participants called for attention and care for those most in need and reported that the police do not have the appropriate knowledge or training to engage with this diverse, multicultural community safely. As a result, communities face hardships when engaging with the police and many have negative perceptions of the police. The police are seen as exacerbating social issues rather than ameliorating these problems.

Using the framework of CRT, we recognized patterning to inequities and injustices described by participants. Community safety is not limited to an experience and a feeling, but more so it involves the provision of appropriate shelter, resources for mental health, and an overall sense of human dignity. The opportunity to reimagine community safety that prioritizes culturally relevant practices that focuses on human rights for the most marginalized may potentially result in a new approach to public safety for diverse large cities like San José.

Our findings of diverse community members' experiences is concordant with studies of community safety from Boston and San Antonio, where researchers found that a sense of community safety is derived from social ties among neighbors and that safety was informed by race, education, employment, and the length of time a person has lived in the community (Lewis et al., 2016; Leverentz et al., 2018). In a context of rapid growth, increasing inequality, gentrification, and displacement, San José residents' experiences have changed over time; a similar process to that described by Austin et al. (2002).

While research in other cities has similarly highlighted the connection between policing and safety (Reisig and Giacomazzi, 1998; Scheider et al., 2003; Shukla et al., 2019), this study was unique in the way that participants named and grappled with feelings of helplessness around the social exclusion they witness and how it undermines their visceral sense of safety to see the rights of others abrogated. These findings build on the work of Gonyea et al. (2018) who found that a sense of social connectedness buffered against depression among older Black and Latinx adults living in subsidized housing in a large northeastern U.S. city and that their sense of how safe they felt in their community was directly related to social connectedness.

As previously observed by several studies, our research found that the built environment also influences residents' feelings of safety (Wilcox et al., 2004; Foster et al., 2012; Oidjarv, 2018). While the emphasis on these previous studies has been on walkability, zoning policies, and other universal interventions, we present new findings that highlight how social exclusion experienced by members of this community because of their race, class, sexual orientation, or gender expression can occur when spaces take on signification as “White spaces,” continuing to make some members of the community unsafe while crime might diminish. Indeed, safety was fundamentally perceived by residents as not just being about being free from physical harm, but also being welcome as they are. Police were perceived as people who hold coercive and potentially violent power, which can undermine opportunities for strengthening community members' building connections and developing practices of belonging when police lack cultural sensitivity or are perceived as present to uphold white supremacy.

The focus on building a physical environment that promotes access, street connectivity, and walkability is often described as objectively improving safety (Leslie et al., 2005). However, within the context of white supremacy, it is also important to pay attention to how people move through these spaces and are either supported in feeling safer or have their safety undermined. Indeed, Wheelock et al. (2019) have documented how race mediates experiences of policing and thus whether police presence contributes to safety or makes people feel unsafe.

Some limitations to our study are worth noting. While recruitment of organizations to lead focus groups was broad, there were some segments of the population who may not have an opportunity to participate in the study. Focus groups were only conducted in English and Spanish. While we used additional methods to include the perspective of some Vietnamese-speaking residents, participants in this study should not be considered representative of the entire community. There were no focus groups specifically for some community members that we anticipate would have unique perspectives on community safety and policing, such as people who identify as LGBTQ, those who currently or previously experienced homelessness, and disabled community members. Given the known adverse experiences with policing in these communities, future research should seek to proactively engage with these stakeholders. Lastly, conversations that occurred within more mixed groups may not have surfaced the same ideas as conversations within salient segments of the population. The ongoing need to assess community safety and policing in San José leaves open opportunities for addressing these limitations in future research.

Conclusion

This study examines diverse community residents' experiences and perspectives, offering a theoretical lens that sheds light on how community safety is intimately connected to basic human rights and capabilities in the context of experiential differences based on race, gender, socioeconomic status, and ability. This novel approach constructs community safety through a framework that prioritizes realization of community rights. Hence, while there has been an ongoing research line examining relationships between community members, safety conditions, policing, social justice and city budgets, this paper offers a theoretical and empirical analysis of community safety that centers foundational human rights. Safety is not simply an experience that one interacts with but safety is inclusive of emotions and relationships, and residents' sense of how their own and their neighbor's dignity is being protected.

With the analysis in hand there are practical suggestion for outcomes that can occur. First, discussions with San José elected officials can be supported with qualitative data that speaks to how communities from different neighborhoods discern community safety. The study highlights how community members feel about the police and their suggestions to better create a feeling of community safety. Second, in providing and protecting community safety, the results indicate that safety is not merely a feeling, but also rooted in having human rights protected. Housing, food security and relationships are things people want and feel would support their lives. City spending could certainly be redistributed in ways to provide and protect these rights. Third, and aligned with the recent amplified racial tension in the USA is to create and promote spaces for BIPOC communities to engage with each other and to coalesce to form bonds where they work to protect one another. With support from the city there could be more activities for relationships to be built within communities that lead to more communal safety initiatives.

To conclude, our study offers valuable insight to how human rights, public safety, city spending and community initiatives can support one another in the name of a socially just San José. This study adds to the ongoing research on public discourses on safety and policing by situating the study in a metropolitan location impacted by years of gentrification, increased costs of living, and multi-generational immigration. Our analysis specifically yielded a nuanced discussion on safety and policing, recognizing that stark inequalities that permeate San José impact people's sense of safety. The right to housing and health were observed to be unprotected and inequitably provided for, undermining resident's sense of community safety. What we learned from this study is that everyone's experience of community safety is impacted when some members of the community do not have their basic human needs met; even those who have plenty cannot feel fully safe while others are in need. To do nothing may result in an increase in threat, to peoples' livelihoods as housing costs increase, employment is precarious, and the city budget is not directly allocated to addressing social issues. Research should continue examining how a community's sense of safety is connected to its ability to meet everyone's basic human rights.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will not be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by San Jose State University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MD, SD, MW, MM, and WA planned the study, with MW and WA initiating the study from the beginning. MW and WA especially worked to secure the grant and community partnerships. MD and SD collected data from specific demographics while MW and MM assisted with carrying out protocol development and data collection from other groups. MD, SD, MW, and MM contributed to the data analysis. MD wrote up the study and took the lead in writing the manuscript. MW, SD, MM, and WA provided critical feedback, edited, and helped shape the manuscript to be submitted. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding for the project was provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, J. M., MacDonald, J. M., Bluthenthal, R., and Ashwood, J. S. (2013). Reducing Crime by Shaping the Built Environment with Zoning: An Empirical Study of Los Angeles. University of Pennsylvania Law Review. p. 699–756

Austin, D. M., Furr, L. A., and Spine, M. (2002). The effects of neighborhood conditions on perceptions of safety. J. Crim. Justice 30, 417–427. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2352(02)00148-4

Barnes, R. D. (1990). Race consciousness: the thematic content of racial distinctiveness in critical race scholarship. Harv. Law Rev. 103, 1864–1871. doi: 10.2307/1341320

Bauer, G. R., Churchill, S. M., Mahendran, M., Walwyn, C., Lizotte, D., and Villa-Rueda, A. A. (2021). Intersectionality in quantitative research: a systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM Popul. Health 14, 100798–100798. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100798

Bell, D. (1987). And We Are Not Saved: The Elusive Quest for Racial Justice. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bell, D. (1992). Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism. acls humanities e-book New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bowleg, L. (2021). Evolving intersectionality within public health: From analysis to action. Am. J. Public Health 111, 88–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306031

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

California Budget Policy Center (2022). Public Policy Research. Available from: https://calbudgetcenter.org/ (accessed August 23, 2022).

Collins, P. H. (1986). Learning from the outsider within: the sociological significance of black feminist thought. Soc. Probl. 33, 14–32. doi: 10.1525/sp.1986.33.6.03a00020

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Fe. Legal Ther. 139, 139–167.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Creswell, J. W., and Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. 39, 124–130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Datausa.io. San Jose CA Census Place. Available online at: https://datausa.io/profile/geo/san-jose-ca/ (accessed April 9, 2022)..,

de Sousa Santos, B. (1998). Participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre: toward a redistributive democracy. Polit. Soc. 26, 461–510. doi: 10.1177/0032329298026004003

Delgado, R. (1988). Critical legal studies and the realities of race - does the fundamental contradiction have a corollary? Harv. Civ. Rights Civil Lib. Law Rev. 23, 407.

Delgado, R. (1995). Critical Race Theory: The Cutting Edge. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Delgado, R., and Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. Critical America. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Foster, S., Christian, H., Wood, L., and Giles-Corti, B. (2012). Planning safer suburbs? The influence of change in the built environment on resdients' perceived safety from crime. Inj. Prev. 18, A9–A10. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040580a.28

Freire, P. (1973). Education for Critical Consciousness. A Continuum Book. 1st American Edn. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

Freire, P., Ramos, M. B., and Macedo, D. (2014). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Thirtieth Anniversary Edn. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Goncalves, S. (2014). The effects of participatory budgeting on municipal expenditures and infant mortality in Brazil. World Dev. 53, 94–110. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.009

Gonyea, J. G., Curley, A., Melekis, K., and Lee, Y. (2018). Perceptions of neighborhood safety and depressive symptoms among older minority urban subsidized housing residents: the mediating effect of sense of community belonging. Aging Ment. Health 22, 1564–1569. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1383970

Ingram, M., Leih, R., Adkins, A., Sonmez, E., and Yetman, E. (2020). Health disparities, transportation equity and complete streets: a case study of a policy development process through the lens of critical race theory. J. Urban Health 97, 876–886. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00460-8

Ladson-Billings, G., and Tate, W. F. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 97, 47–68. doi: 10.1177/016146819509700104

Leslie, E., Saelens, B., Frank, L., Owen, N., Bauman, A., Coffee, N., et al. (2005). Residents' perceptions of walkability attributes in objectively different neighbourhoods: a pilot study. Health Place 11, 227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.05.005

Leverentz, A., Pittman, A., and Skinnon, J. (2018). Place and perception: constructions of community and safety across neighborhoods and residents: place and perception. City Commun. 17, 972–995. doi: 10.1111/cico.12350

Lewis, R. J., Ford-Robertson, J., and Dennard, D. (2016). Inner city quality of life: a case study of community consciousness and safety perceptions among neighborhood residents. OAlib 3, 1–11. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1103128

Lorde, A. (2021). “Age, race, class, and sex: Women redefining difference,” in Campus Wars (Routledge), 191–198.

Matsuda, M. J. (1991). Voices of America: accent, antidiscrimination law, and a jurisprudence for the last reconstruction. Yale Law J. 100, 1329–1407. doi: 10.2307/796694

Nashville People's Budget Coalition. (2020). Nashville People's Budget Survey. Available online at: https://nashvillepeoplesbudget.org/peoples-budget-survey/ (accessed April 9, 2022).

Nofziger, S., and Williams, L. S. (2005). Perceptions of police and safety in a small town. Police Q. 8, 248–270. doi: 10.1177/1098611103258959

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating Capabilities the Human Development Approach. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Oidjarv, H. (2018). The tale of two communities: residents' perceptions of the built environment and neighborhood social capital. SAGE Open 8, 215824401876838. doi: 10.1177/2158244018768386

Owens, E., and Ba, B. (2021). The economics of policing and public safety. J. Econ. Perspect. 35, 3–28. doi: 10.1257/jep.35.4.3

People's Budget LA. (2020). People's Budget Coalition of Los Angeles. Available online at: https://peoplesbudgetla.com/ (accessed April 9, 2022).

Ratcliffe, J. H., Groff, E. R., Sorg, E. T., and Haberman, C. P. (2015). Citizens' reactions to hot spots policing: impacts on perceptions of crime, disorder, safety and police. J. Exp. Criminol. 11, 393–417. doi: 10.1007/s11292-015-9230-2

Redfin (2022). San Jose Housing Market: House Prices & Trends. Available online at: https://www.redfin.com/city/17420/CA/San-Jose/housing-market (accessed August 23, 2022).

Reisig, M. D., and Giacomazzi, A. L. (1998). Citizen perceptions of community policing: are attitudes toward police important? Policing 21, 547–561. doi: 10.1108/13639519810228822

Russell, M. M. (1992). Entering great America - reflections on race and the convergence of progressive legal theory and practice. Hastings Law J. 43, 749–767.

Scheider, M. C., Rowell, T., and Bezdikian, V. (2003). The impact of citizen perceptions of community policing on fear of crime: findings from twelve cities. Police Q. 6, 363–386. doi: 10.1177/1098611102250697

Sen, A. D. (1999). The Amartya Sen and Jean Dréze Omnibus: Comprising Poverty and Famines, Hunger and Public Action, India: Economic Development and Social Opportunity. New Delhi; New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Shukla, R. K., Stoneberg, D., Lockwood, K., Copple, P., Dorman, A., and Jones, F. M. (2019). The interaction of crime & place: an exploratory study of crime & policing in non-metropolitan areas. Crime Prev. Commun. Saf. 21, 200–214. doi: 10.1057/s41300-019-00072-8

Solórzano, D. G. (1997). Images and words that wound: critical race theory, racial stereotyping, and teacher education. Teach. Educ. Q. 24, 5–19.

Solórzano, D. G. (1998). Critical race theory, race and gender microaggressions, and the experience of Chicana and Chicano scholars. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 11, 121–136. doi: 10.1080/095183998236926

Solórzano, D. G., and Bernal, D. D. (2001). Examining transformational resistance through a critical race and latcrit theory framework: Chicana and Chicano students in an urban context. Urban Educ. 36, 308–342. doi: 10.1177/0042085901363002

Solórzano, D. G., and Yosso, T. J. (2001). Critical race and LatCrit theory and method: counter-storytelling. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ.14, 471–495. doi: 10.1080/09518390110063365

Souza, C. (2001). Participatory budgeting in Brazilian cities: limits and possibilities in building democratic institutions. Environ. Urban 13, 159–184. doi: 10.1177/095624780101300112

Su, C. (2017). From Porto Alegre to New York City: participatory budgeting and democracy. New Polit. Sci. 39, 67–75. doi: 10.1080/07393148.2017.1278854

UN General Assembly International Covenant on Civil Political Rights.. (1966). United Nations, Treaty Series, Vol. 999. p. 171. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

Valdes, F., Culp, J. M., and Harris, A. P. (2002). Crossroads, Directions, and a New Critical Race Theory. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Wheelock, D., Stroshine, M. S., and O'Hear, M. (2019). Disentangling the relationship between race and attitudes toward the police: police contact, perceptions of safety, and procedural justice. Crime Delinq. 65, 941–968. doi: 10.1177/0011128718811928

Wilcox, P., Quisenberry, N., Cabrera, D. T., and Jones, S. (2004). Busy places and broken windows? Toward defining the role of physical structure and process in community crime models. Sociol. Q. 45, 185–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb00009.x

Wolfe, E. (2022). Report Warns of Worsening Wealth Gap in Silicon Valley. San José Spotlight. Available online at: https://sanjosespotlight.com/joint-venture-report-highlights-silicon-valley-wealth-gaps-and-tech-booms-san-jose-santa-clara-county/ (accessed April 18, 2022).

Keywords: community safety, policing, human rights, sociocultural conditions, Critical Race Theory, capabilities, intersectionality

Citation: Dao M, De Bourbon S, McClure Fuller M, Armaline W and Worthen M (2022) Understanding community safety and policing in San José, California: A qualitative and communal analysis. Front. Sustain. Cities 4:934474. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.934474

Received: 02 May 2022; Accepted: 22 September 2022;

Published: 19 October 2022.

Edited by:

Tiit Tammaru, University of Tartu, EstoniaReviewed by:

Darrell Norman Burrell, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United StatesCalvin Nobles, Illinois Institute of Technology, United States

Copyright © 2022 Dao, De Bourbon, McClure Fuller, Armaline and Worthen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael Dao, bWljaGFlbC5kYW9Ac2pzdS5lZHU=

Michael Dao

Michael Dao Soma De Bourbon

Soma De Bourbon Melissa McClure Fuller

Melissa McClure Fuller William Armaline

William Armaline Miranda Worthen

Miranda Worthen