- 1Department of Geography, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

- 2Department of Town and Regional Planning, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

This article examines the urban (in) security landscape in a postcolonial emerging human settlement in Africa. Hopley Farm Settlement is used as a case study focusing on the perspectives of this urban (in) security on spatial justice. This study contributes to the emerging scholarship on African cities that focuses on urban security, which is increasingly becoming a critical issue owing to multiple socioeconomic, political, and environmental risks inherent in Africa. We argue that the poor residing in emerging human settlements are victimized mainly and subjected to different forms of violence exposing them to urban (in) securities. This insecurity makes it challenging to achieve the envisaged sustainable development goal that aspires to create safe and resilient cities and settlements by 2030. The study employed an exploratory phenomenological research design where data were collected from 450 questionnaires administered to residents and 20 in-depth interviews with residents from Hopley. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. The study maps Hopley's (in) security terrain, focusing on different parameters that bring insights to the security scape of the settlement. The strategies employed by the community to navigate this complex terrain are explored in light of infrastructural violence theory, which brings insights into spatial justice. The findings reveal that the envisaged mixed used settlement form considers urban security in the design of Hopley. However, the realities of the settlement show complex urban insecurities, including unsafe living environments, political victimization, lack of tenure, crime and violence that manifest even through severe cases such as murder and rape. Marginalization of the poor is thus prevalent in this community and calls for the government to reconsider the planning, development, and management of emerging settlements where the poor reside in the shadow of the state.

Introduction

Urban insecurity is a persisting challenge stifling urban liveability in most African cities (African Policy Circle., 2020). The situation is dire in emerging human settlements characterized by poverty, unemployment, limited infrastructure such as police stations, and street lighting exposes the communities to several risks. Emerging human settlements are identified as “self-developed” settlements “starting” from “scratch” through community self-development initiatives (Green and Handley, 2009). The self-developed settlements are often located on the city's margins, where land values are relatively low, thus accommodating the urban poor (Matamanda, 2020). Therefore, being on the margins of the city, Yiftachel (2009) explained that emerging human settlements exist in the shadow of the formal city. Emerging settlements are thus characterized by “locational discrimination” owing to their positions in undesirable locations that may also be outside the city's developable area (Soja, 2010). This positioning of the emerging settlement in the shadows and “darkness” of the formal city is attributed to the political economy of human settlement development that has seen politicians giving less priority to these settlements (Yiftachel, 2009).

The spatial and governance characteristics of emerging human settlements expose them to multiple challenges, including economic inequality, weak state capacity, and limited opportunities for the urban dwellers who end up resorting to crime and violence to eke a living (Fox and Beall, 2012; Mphambukeli, 2015; African Policy Circle., 2020). In this way, the liveability of cities is compromised, a situation that makes it difficult to achieve the imagined sustainable development goal (SDG) eleven that “envisage to make cities safe, resilient, sustainable and inclusive” by 2030. This SDG confirms other national policies acknowledging that safety is a critical issue to be considered in developing and managing human settlements (Government of Zimbabwe, 2020).

The failure to factor in urban safety and security in human settlement planning and management proves to be disastrous because the impact of crime and insecurity restricts social and economic development, which ultimately compromises opportunities and pro-poor policies (Muggah, 2012; Ceccato and Nalla, 2018). However, achieving such safe human settlements is contingent on urban planning approaches that should address safety and security issues (Matai et al., 2021).

From the preceding paragraph, it is clear that security issues constitute a crucial aspect of human settlements. Urban centers in Zimbabwe are increasingly becoming hubs of violence and crime, affecting the safety of the residents, especially the poor, who cannot invest in security measures such as private security services. The overall crime rate in Zimbabwe increased by 10 to 15 percent across most sectors in 2016. Harare is also becoming an environment where robbers and criminals thrive and prowling innocent citizens (Matai et al., 2021; Whiz, 2021). The most significant safety and security threats in urban centers across Zimbabwe are “crimes of opportunity and include routine thefts, residential burglaries, and smash and grab attacks (especially at dark intersections at night). In Zimbabwe, the perpetrators of criminal activities also engage in violent crimes such as assaults, rape, robbery, and theft, while murder cases are increasing (Tshili, 2021). In their study, Oosterom and Pswaray (2014) found that violent crime characterizes many of the poorer, high-density suburbs in Zimbabwe. The findings of this study confirm the observations made by Muggah (2012: vii) and Tshili (2021) that the more pernicious effects of urban violence appear to be concentrated in marginalized settlements and among low-income families.

Yet, existing studies on urban insecurity in Zimbabwe have not considered how urban insecurity is intricately related to spatial injustice. Nyabvedzi and Chirisa (2012) considered the spatial dimensions of security and possible solutions for combating crime, though the focus has been on the affluent suburbs of Harare. Their study highlighted how Marlborough East residents have suffered severe property, life, and valuables losses. Chirisa et al. (2016) examined the policies and strategies that may be used to combat crime and insecurity in selected cities in southern Africa. Similarly, Matai et al. (2021) analyzed the role of urban planning and design as tools for managing crime and security in Harare. This study is situated in this ongoing discussion and scholarship on urban security and infrastructure violence.

The study argues that crime and violence inherent in emerging human settlements perpetuates urban insecurity through physical characteristics of the settlements, such as lack of basic services, limited economic opportunities, and weak policing and governance systems regulating the everyday activities in the settlements. Subsequently, the communities are subjected to infrastructure violence and spatial injustice that manifests through the locational discrimination and urban policies or the lack of to accommodate the needs of these marginal communities. Its focus is on exploring ways in which the spatial characteristics and governance of emerging human settlements. Therefore, this study examines the urban (in) security landscape in Africa's postcolonial emerging human settlement. Hopley Farm Settlement is used as a case study focusing on the perspectives of this urban (in) security on infrastructure violence.

Theoretical and conceptual framing

Safety and security are vital considerations in the establishment of human settlements. Specifically, through sustainable development goal (SDG) eleven, governments espouse to make human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable by 2030. However, insecurity remains a key issue in emerging human settlements in most cities in the Global South. Several studies have focused on the built environment and how urban design contributes to city crime and violence (Jacobs, 1961; Newman, 1973; Chirisa et al., 2016). The safety of a settlement is also a product of the built environment where the ultimate form of the settlement tends to have a bearing on the residents' ability to feel safe and comfortable. Jacobs (1961, p. 35) argued that streets contribute significantly to safety in human settlements. She indicated that three main qualities of streets enhance the safety of settlements. First, streets act as boundaries that help separate public and private space thus impacting on the spatiality of crime and violence (Schnell et al., 2017). These clear boundaries help curb trespassing by defining the urban space where the property owner feels safe. Second, the street must always be an active space where there are eyes that include certain land use activities that help to make the streets lively all the times. Chirisa et al. (2016) affirmed that streets can be designed to become active and interactive spaces. Third, Jacobs (1961) suggested that there must be users who continuously use sidewalks. These users become additional eyes on the streets as crime and violence have been noted to occur in desolated sections of the settlements where no one frequents at certain times of the day. However, Leyden (2003) and Lund (2003) have the opinion that some land use arrangements encourage greater resident street activity that increase passive surveillance while also having the ability to create opportunities for crime if these individuals may be offenders according to Zahnow (2018) may capitalize on the crowds in perpetuating crimes.

According to Newman (1973), safety in settlements could be provided through the conception of the defensible space that focuses on using alienating mechanisms to reduce crime in neighborhoods and make them safer. From his conception, Newman (1973) reasoned that safety in urban spaces is enhanced through four key design elements: territoriality, surveillance, image, and milieu and environment. Territoriality depicts the built form acting as symbolic and actual barriers to perpetuating crime and violence in settlements. Surveillance emerges as a key component that in the modern day has been upscaled to include surveillance cameras (Chirisa et al., 2016) that are mounted even in public spaces and depict the “eyes” on the streets identified by Jacobs (1961). Also, the design and management of the built form greatly help support the settlements' liveability, especially considering safety issues. The environment is the last strand that reveals how the surrounding spaces influence the settlement's security (Silva and Li, 2020). The environment can include open spaces such as wetlands and urban forests that become crime hotspots or fearscapes. Usually, the environmental factors align with the lack of eyes; for example, cemeteries are desolate areas that many shy away from but have proved to be dangerous scapes in urban areas (Adel et al., 2016). This is key considering how most emerging settlements are positioned on the edge of cities. Beyond the design and form of the built environment, the provisioning and servicing of the human settlements also become a critical factor in enabling or disabling urban safety in emerging human settlements.

Infrastructure violence in emerging human settlements and the creation of fear spaces

Infrastructural violence is a concept that manifests from spatial injustice. Infrastructure violence explains the exclusion and marginalization suffered by specific individuals and groups due to the planning, design, and provision of infrastructure and services (Rodgers and O'Neill, 2012). Such infrastructure and services include reticulated water, sanitation, electricity, public transport, and housing. Since these infrastructures are critical in sustaining the liveability of emerging human settlements, their inadequacy or absence, in extreme cases, causes untold suffering to the individuals and groups denied access to these services (Mphambukeli, 2019; Truelov and O'Reilly, 2021).

The exclusion and displacement associated with the infrastructural violence result from human settlements' planning and governance function, increasing the vulnerability of specific individuals and groups, especially the poor. Through this displacement, Yiftachel (2009) has postulated that “gray spaces” emerge where the poor are entrenched in awful spaces in the shadows of the formal city. Being in the shadow of the formal city means these communities are positioned in the “blackness” of the city. This blackness is characterized by evictions/destruction/death, which symbolize unsafe and unliveable spaces that become dangerous and life-threatening for the inhabitants. Informal settlements are a typical example of how the poor are forced into these unsafe spaces.

Kamete (2017) applied the concept of the “camp,” which he likened to the Nazi's concentration camps where residents were victimized, harassed, and lived in fear of the state agents and several other forces that threatened their peace and security.

According to Rodgers and O'Neill (2012, p. 402), infrastructural violence can be active and arises through the “articulation of infrastructure that are designed to be violent.” Desai (2018, p. 89) explained that infrastructure is designed to be violent when “the ways in which urban planning, policies and governance forge infrastructure that produces […] inadequacies and everyday deprivations, burdens, inequities, tensions, and conflicts in residents' lives.” This type of violence is inherent in most African cities. It becomes the root of most insecurity issues in cities as the inadequacies become viable groups from multiple urban maladies and criminal activities as residents seek alternative services. Moreover, the designs may perpetuate fear scapes where certain areas, by their design or lack of adequate infrastructure provision, become hotspots of criminal activities (England and Simon, 2010). According to Yiftachel (2009), this violence in design is evident in most cities of the South that exhibit signs of “creeping urban apartheid” showing how the “gradations of rights and capabilities commonly based on inscribed classifications” trigger crime and violence. The South African case of the Apartheid planning systems shows how the spatial segregation has also contributed to some insecurity and safety issues in most poor suburbs that were positioned on the city edges and also with limited services such as police stations and integrated transport systems that often places the commuters at risk, especially those navigating the first/last mile in the early hours of the morning before daylight or later in the day after sunset (Breetzke, 2012; Jean-Claude, 2014). The distance from services and economic opportunities, such as schools and work forces the residents to leave homes early and come back late, compromising their safety as they navigate this last mile (Nche, 2020).

The gray spaces articulated by Yiftachel (2009) resonated with infrastructural violence because being in the shadow of the city and positioned in spaces susceptible to destruction and death often means the government fails to provide and cater for the servicing and provisioning of these settlements. Subsequently, residents must reside in communities lacking basic services such as water and sanitation, electricity and public transport, exposing them to several dangers and threats (Mphambukeli, 2015; Ramakrishnan et al., 2021). According to Young (1990), this denial and exclusion make individuals and groups vulnerable to exploitation.

Passive infrastructural violence refers to socially harmful effects derived from infrastructure's limitations and omissions (Rodgers and O'Neill, 2012). For example, when people are deliberately excluded from accessing infrastructure services, they tend to be exposed to multiple insecurities and safety concerns.

Emerging human settlements are marginal spaces. They are usually deprived of basic infrastructure and services that are the bedrock of the functionality of any settlement. For example, street lighting is never present, and water and sanitation facilities are not provided, leaving the communities to improvise. Public transport services are also problematic, especially considering the state of the roads that makes it difficult for taxis to navigate. Consequently, public transport does not serve the communities, making it difficult for commuters to navigate the last mile. The situation is especially dire for those who commute to and from work when it is dark. Owing to these infrastructure deficiencies, the emerging settlements thus become spaces of fear as residents, especially women, become victims of rape when accessing water (Matamanda, 2020). Mugging and robberies also become prevalent for those covering the last mile. This is especially true when the individuals have to walk through open spaces, cemeteries or any space that are dangerous scapes.

Methodology

Description of the study area

Hopley Farm Settlement is located on the edge of Harare, in the southerly parts of the city. The settlement is approximately 15 kilometers from the city center and is disconnected from economic activities. Hopley Farm settlement was established in 2005 after Operation Murambatsvina (OM)1. The government sought to house the victims of the OM through Operation Garikai/Hlalani Kuhle following the visit of a United Nations delegation that had come to assess the magnitude of the human rights violation that the government had executed OM (Tibaijuka, 2005). However, the government justified its decision through legislation such as section 35 of the regional town and country planning act that empowers local authorities to “[…] remove, demolish or alter existing buildings […]” considered to be compromising urban liveability (Government of Zimbabwe, 1976). Through the Ministry of Local Government and Housing Services, the government of Zimbabwe directed the City of Harare to allocate housholds displaced by OM plots in Hopley Farm Settlement (Matamanda, 2020). Before OM, the City of Harare had finalized preparations of a layout plan for Hopley Farm settlement but had not allocated any beneficiaries plots due to the absence of reticulated water and sewer (Bandauko et al., 2022). This complied with the provisions of section 86 of the Public Health Act that mandates local authorities to provide and maintain “[…] a sufficient supply of wholesome water for drinking and domestic purposes …” and section 104 of the same act that considers settlements with such wholesome water supply and reticulated sanitation systems as nuisances and not fit for human habitation.

Albeit the absence of the services, some households displaced by OM were allocated plots in Hopley Farm Settlement. The establishment of Hopley Farm Settlement thus depicted the “camp” articulated by Kamete (2017), showing how the poor have been confined in abject space with limited opportunities and services to sustain their livelihoods and well-being.

Research design and methods

The study is qualitative and employs an exploratory phenomenological research design (Smith et al., 2009). The exploratory phenomenological research design was instrumental in exploring the lived experiences of the residents from Hopley regarding urban security challenges.

A survey was initially undertaken with 450 questionnaires administered to household heads in Hopley Farm Settlement to get a general overview and understanding of the residents' safety and security needs and concerns. Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the University of the Free State human research Ethics Committee (UFS-HSD2017/0808). The study was conducted in November – December 2017. At the time, it was estimated that 7,000 households were accommodated in Hopley Farm Settlement. The Yamane formula2 was used to determine the sample size. From the formula, a sample size of 378 was obtained, however, 450 questionnaires were eventually administered after factoring in an attrition level at 19%. The questionnaire survey formed the basis for the in-depth interviews as particular respondents divulged particular issues that needed further discussion. During this stage of the survey, we sought the consent of some respondents willing to provide more in-depth information regarding accessing basic services in Hopley Farm Settlement.

Twenty in-depth interviews conducted with residents from Hopley. These interviews were conducted with individuals who had experienced crime or violence in Hopley or knew someone to provide their lived experiences of the safety scape in Hopley. The focus was on identifying how the settlement form and function relate to crime and violence in the settlement and how the provision or lack of basic services and infrastructure impacts security in Hopley Farm Settlement. Key informant interviews were also conducted with three planning professionals working in the public sector.

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data. The four steps proposed by Erlingsson and Brysiewicz (2017) on data analysis guided the data analysis process for this study. First, we familiarized with the interview and survey data through reading critically the interview notes and transcriptions from the fieldwork. This enabled us to divide the data into meaning units that focused on urban insecurity issues from the infrastructure violence and emerging settlement lens. Third, we condensed these meaning units into codes and lastly developed categories and themes. The themes were broadly focused on the nature of infrastructure or the lack of in the emerging settlement and the realities of safety and security concerns in Hopley Farm Settlement.

Findings from Hopley Farm Settlement

Infrastructure and services violence in Hopley Farm Settlement

As mentioned earlier, it was alluded to by the officials from the City of Harare that Hopley Farm Settlement was a planned settlement with layout designs and proposals set for infrastructure provision. This has been confirmed by Matamanda (2019) and Muchadenyika (2020), highlighting the envisaged infrastructure and service delivery in Hopley. Regarding water, proposals were made by the City of Harare through the Southern Incorporated Plan, which covers Hopley to connect the settlement to existing water mains for Harare (City of Harare., 1999). However, the Harare Combination Master Plan of 1992 lucidly pointed out the need for new public utility infrastructure commensurate with the “continued outward expansion of the City of Harare” (City of Harare., 1992, p. 3). This situation shows the fragility of the existing water infrastructure in Harare, which was apparent from the community member in Hopley Farm Settlement, who then revealed the water woes they have been experiencing since relocating to the settlement.

The same applies to sanitation facilities. According to the town planner, she indicated that “since reticulated sewer is considered a norm in urban settlements in Zimbabwe, it was proposed that Hopley Farm Settlement would be connected through the Mukuvisi outfall to the Firle Sewerage Works.” This reticulated sewer resonated with the Public Health Act, part IX, section 82, which encourages the safe disposal of fecal matter and wastewater in human settlements, thereby sustaining human dignity and public health. Moreover, the plot sizes in Hopley Farm Settlement that ranged between 150 and 350 m2 meant that centralized sanitation system was the most ideal for the settlement as stipulated in Circular 70 of 2004. The circular stipulates that all plot sizes in the high-density suburbs must be connected to a reticulated sewer system. In the same manner, the proximity of Hopley Farm Settlement to existing sewer works meant it would be easier for the settlement to be connected as explained above.

Overall, a mixed land use development was envisaged for Hopley Farm Settlement. This was alluded by a planning consultant interviewed who pointed out that “A mixed land use planning approach was designed for Hopley taking cognisant of the adjacent suburb of Waterfalls. We sought to use the existing and planned infrastructure to make this settlement liveable.” This mixed land use development resonates with the ideals of Newman (1975) and Jacobs (1961), focusing on providing infrastructure and services such as police stations. It was also planned to incorporate different land uses within the settlements to give residents easy access to services, such as schools and employment opportunities. Transport issues were also considered considering the need for an integrated transport planning system that would promote safety in the settlement. This was explained by the official from the City of Harare's transport department that in planning for Hopley, there was a consideration on how best road safety was to be affected so that road accidents would be minimized.

The realities of safety and security in Hopley Farm Settlement

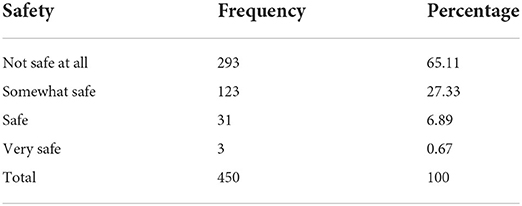

Table 1 shows the survey responses of the residents in Hopley regarding perceptions of safety in the settlement. It emerged that 65.11 per cent of the respondents did not feel safe in Hopley Farm Settlement. Residents interviewed pointed out some experiences that made them feel insecure in Hopley Farm Settlement. One man, a resident in Hopley Farm Settlement who was interviewed, remarked “My tenant was murdered at Chitungwiza Road recently. This incident has made me feel extremely unsafe in Hopley.” Another respondent, a woman, illustrated the gendered dimensions of insecurity in Hopley Farm Settlement. The woman remarked, “the incident when a young girl was murdered at a nearby dam was too much for me to handle as a woman and the experience always makes me feel like I am prey and there are vultures out there watching me.” This incident narrated by the women also shows how the environment can contribute to the perpetuation of certain crimes, as postulated by Newman (1975). The dam area in Hopley Farm Settlement is a desolate and eerie place with a wetland area and is not habited; hence, it becomes a dangerous area at night.

Some 27.33 per cent highlighted that they somewhat felt safe in Hopley. In contrast, a mere 0.67 per cent of 3 respondents mentioned that a low percentage of the survey respondents indicated feeling safe (6.89 per cent) in the settlement. In comparison, a mere 0.67 per cent of 3 respondents said they felt very safe in Hopley Farm Settlement. These survey findings revealed that residents in Hopley live in fear and do not enjoy the comfort of the settlement, which depicts the gray space described by Yiftachel (2009). This also asserts the conceptions of Kamete (2017), likening the settlement to a camp where fear is an intricate part of the everyday lives of the residents.

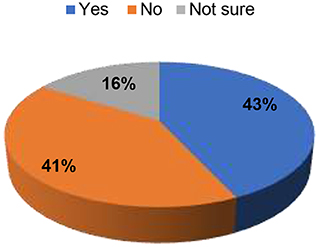

Figure 1 summarizes the experiences of the respondents with safety issues in Hopley. It is shown that 43 per cent of the respondents experienced an incident in which they felt unsafe and threatened in Hopley. A further 41 percent indicated that they never felt or experienced fear, while 16 percent were unsure. These findings illustrate the apparent insecurity and unsafe space characterizing Hopley Farm Settlement. The respondents who mentioned that they had experienced incidences that made them insecure and afraid highlighted their gruesome experiences in Hopley Farm Settlement. These accounts reveal the insecurity of the settlement and bring to attention the depiction of the settlement as a fearscape. The following response from a resident interviewed demonstrates some lived experiences of the residents in Hopley regarding insecurity and safety issues in the settlement. A widow recounted, “When a thief broke into our house, the experience was traumatizing as they exposed the lack of security in the neighborhood and my house.”

Figure 1. Responses to the question on the experiences in which the respondents felt unsafe in the neighborhood.

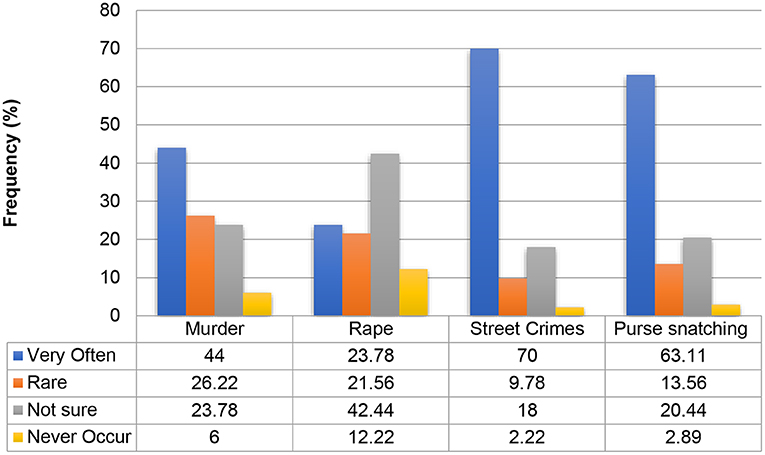

Different types of crimes make Hopley unsafe. Figure 2 highlights the nature of criminal activities that make Hopley Farm Settlement unsafe by compromising the well-being of the residents. First, the respondents confirmed that criminal activities that occurred very often in the settlements are street crimes (70 per cent), purse-snatching (63.33 per cent), murder (44 per cent), and rape (23.78 per cent). The high prevalence of street crimes brings to attention a lot of issues that the residents explained. First, the streets in Hopley Farm Settlement are not well-defined in most areas, including narrow paths that pass through different areas, including the wetland and then the cemeteries on the other side of the settlement. Some women lamented that the streets are unsafe at night, lack lighting, and thus become unsafe. One respondent remarked, “it is not safe to walk in Hopley Farm Settlement at night because you will b robbed.” Another respondent confirmed this statement and lamented that “at night, the whole of Hopley becomes a danger zone, and women are the major victims.”

The absence of reticulated water and sanitation facilities in Hopley Farm Settlement has been largely linked to safety issues in the settlement. It was revealed that 42 per cent of the respondents use pit latrines. These pit latrines are positioned outside the houses and expose the households to different risks, especially when using the toilets at night. Figure 3 shows one pit latrine lacking privacy and exposes the user to some perverts. A woman explained that “using this toilet is risky, even during the day. It is even dangerous at night as one can easily get in there and rape you.” This finding confirms the statistics presented in Figure 2, showing that 23.78 per cent of the respondents confirmed that rapes often occur while 21.56 per cent highlighted that rapes rarely occur. One respondent boldly stated, “there are too many rape cases which go unreported and I always feel I can be raped at any time.”

Figure 2 shows that street crimes and purse snatching top the list in their occurrence. Some areas were singled out as high crime zones, such as Zone 2, because of overcrowding and the high poverty rates that characterize the area. Specifically, this findings points to the spatiality of crime and violence that is concurrent with poverty. This also points to the heterogeneity of crime and violence in an emerging settlements showing how some areas may be considered relatively safer than others. The high unemployment rates in Hopley Farm Settlement have also been identified as a trigger for crime and violence. This is especially true when the poor seek to earn a living through criminal activities.

For some respondents, the prevalence of insecurity in Hopley Farm Settlement has been attributed to the form of the settlement. First, the distance residents have to travel from Chitungwiza Road to access public transport exposes them to thieves and thugs, especially those coming from work at night or going to work early in the morning. The cases of murder that the residents have reported during the interviews were mainly concentrated along Chitungwiza Road, where minibusses drop commuters off at night. Women are usually the targets. One respondent commented that “minibuses do not operate within the settlement due to poor roads. We (commuters) are dropped along Chitungwiza Road, which is not safe, especially at night and early hours of the morning, exposing us to murder and robbery.” This instance demonstrates how safety is associated with commuters covering their last and first mile in the early hours of the day before daybreak and after sunset at night.

Discussion and conclusion

The study interrogates the urban safety and insecurity landscape in Hopley Farm Settlement+, an emerging settlement, through the lens of infrastructural violence. First, it was revealed that Hopley Farm Settlement's level of safety and security is very low. Residents live in fear; thus, the settlement characterizes a fearscape in which they are continuously afraid. This finding is consistent with several studies (Mphambukeli, 2019; Nche, 2020) that have depicted the unsafe nature and conditions prevailing in emerging human settlements.

Second, the built environment's contribution to perpetuating crime and violence in

Hopley Farm Settlement is apparent. This is consistent with the articulation by Lund (2003), that show how the built environment enables safety in human settlements through the design of streets and activities that occur there that make the streets lively. Also, the absence of a police station made the area susceptible to crime as there were no police officers to monitor the neighborhood. This monitoring is critical and indicates the eyes on the street (Jacobs, 1961; Newman, 1975) that can help curb criminal activities.

Third, the role of poverty and unemployment in contributing to urban insecurity is revealed. Such findings confirm how some poor individuals deprived of opportunities resort to criminal activities (Muggah, 2012; Oosterom and Pswaray, 2014). Therefore, we established that poverty is an external factor that is not related to the settlement form but has a bearing on crime and ultimately compromises safety within the neighborhood.

Fourth, the gendered perspectives of insecurity in Hopley Farm Settlement emerge, which confirms several studies that highlight the vulnerability of women in urban settlements (Nyabvedzi and Chirisa, 2012; Matai et al., 2021; Tshili, 2021). Such findings contradict the values and aspirations of the liveable city that seeks to be inclusive and cater to the needs of all urbanites. This situation brings to attention the logic of the camp postulated by Kamete (2017), showing how the emerging settlements experience multiple deprivations that can be life-threatening. Similarly, the notion of gray spaces articulated by Yiftachel (2009) is evident in Hopley Farm Settlement, showing how the positioning of the poor in the shadow of the formal city, as was done for Hopley Farm Settlement (Matamanda, 2020), exposes the residents to death/eviction/destruction as illustrated in the rapes and murders reported by the respondents from Hopley Farm Settlement.

Fifth, the presented findings further support the infrastructural violence theory postulated by Rodgers and O'Neill (2012). The absence of infrastructure and services in Hopley Farm Settlement has produced unsafe conditions that have exposed the residents to unsafe conditions. These include the lack of water and sanitation facilities that place the residents at risk. This situation denotes passive infrastructural violence (Rodgers and O'Neill, 2012), where the absence and omissions of reticulated services have contributed to social and physical harm among some residents in Hopley Farm Settlement. The absence of road infrastructure has been linked to public transport problems and challenges for residents in navigating the last and first mile indicating how residents are exposed to unsafe conditions asserting the findings from a study by Nche (2020).

This study concludes that safety and insecurity issues in emerging settlements are enabled by the marginalization of the poor in settlements lacking basic services. The exclusion increases their vulnerability and places them at a disadvantage calling for concerted efforts that address this exclusion and marginalization of these residents. The plight of women at greater risk needs serious consideration, which calls for gendered perspectives in planning for human settlements that proactively recognize gender dynamics. Further research from this study may undertake a spatial analysis of the unsafe hotspots in the settlements or areas where most crimes and violence have occurred. The findings from such will help policymakers to formulate policies addressing the insecurity and safety issues in the settlement.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of the Free State. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^OM was launched in 2005 where the government of Zimbabwe orchestrated the demolition of ‘informal' housing and activities in the urban areas to curb the growing informal sector in the country. The operation affected at least 700,000 people that were left homeless or lost their livelihoods.

2. ^The Yamane formula: n = N/1+N(e)2. N is the target population which is 7,000 households in this case of Hopley Farm Settlement. n is the sample size while e is the sampling eror or level of precision.

References

Adel, H., Salheen, M., and Mahmoud, R. A. (2016). Crime in relation to urban design. Case study: The Greater Cairo Region. Ain Shams Eng. J. 7, 925938. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2015.08.009

African Policy Circle. (2020). Addressing the challenges of urbanization in Africa: A summary of the 2019 African Policy Circle Discussions.

Bandauko, E., Kutor, S. K., Annan-Aggrey, E., and Arku, G. (2022). ‘They say these are places for criminals but this is our home': internalising and countering discourses of territorial stigmatisation in Harare's informal settlements. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 44, 217–239. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2021.9

Breetzke, G. D. (2012). Understanding the magnitude and extent of crime in postapartheid South Africa. Soc. Iden. 18, 299–315. doi: 10.1080/13504630.2012.661998

Ceccato, V., and Nalla, M. K. (2018). Crime and fear in public places: towards safe, inclusive and sustainable cities. London and New York, NY: Routledge

Chirisa, I., Bobo, T., and Matamanda, A. R. (2016). Policies and strategies to manage urban insecurity: focus on selected African cities. J. Public Policy Africa 3, 93–106.

City of Harare. (1999). Local development plan No. 31: Southern Incorporated Areas. Harare: City of Harare

Desai, R. (2018). Urban planning, water provisioning, and infrastructural violence at public housing resettlement sites in Ahmedabad, India. Water Alternat. 11, 86–105. Available online at: https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol11/v11issue1/421-a11-1-5/file

England, M. R., and Simon, S. (2010). Scary cities: urban geographies of fear, difference and belonging. Soc. Cultural Geogr. 11, 201–207. doi: 10.1080/14649361003650722

Erlingsson, C., and Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 7, 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

Fox, S., and Beall, J. (2012). Mitigating conflict and violence in African cities. Env. Plan. C Govern. Policy 30, 968–981. doi: 10.1068/c11333j

Government of Zimbabwe (1976). Regional, Town and Country Planning Act (Chapter 29:12). Harare: Government of Zimbabwe.

Government of Zimbabwe (2020). Zimbabwe National Human Settlements Policy (ZNHSP). Harare: Government of Zimbabwe.

Green, N., and Handley, J. (2009). “Patterns of settlement compared,” in Davoudi, S., Crawford, J., and Mehmood, A., eds. Planning for Climate Change: Strategies for Mitigation and Adaptation for Spatial Planners. London: Earthscan.

Jean-Claude, M. (2014). Townships as crime ‘Hot-Spot' areas in Cape Town: perceived root causes of crim in site B, Khayelitsha. Mediterranean J. Soc. Sci. 5, 596–596. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n8p596

Kamete, A. Y. (2017). Governing enclaves of informality: unscrambling the logic of the camp in urban Zimbabwe. Geoforum 81, 76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.02.012

Leyden, K. M. (2003). Social capital and the built environment: the importance of walkable neighborhoods. Am. J. Public Health 93, 1546–1551. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1546

Lund, H. (2003). Testing the claims of new urbanism: local access, pedestrian travel, and neighboring behaviors. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 69, 414–429. doi: 10.1080/01944360308976328

Matai, J., Mafuku, S. H., and Zimunya, W. (2021). “Managing urban crime and insecurity in Zimbabwe,” in Matamanda, A.R., Nel, V., Chirisa, I., eds. Urban Geography in Postcolonial Zimbabwe: Paradigms and Perspectives for Sustainable Urban Planning and Governance. (Cham: Springer Nature). 163–179.

Matamanda, A. R. (2019). Exploring Emerging Human Settlement Forms and Urban Dilemmas Nexus: Challenges and Insights From Hopley Farm, Harare, Zimbabwe. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of the Free State

Matamanda, A. R. (2020). Living in an emerging settlement: the story of Hopley Farm Settlement, Harare, Zimbabwe. Urban Forum 31, 473–487. doi: 10.1007/s12132-020-09394-5

Mphambukeli, T. N. (2015). Exploring the Strategies Employed by the Greater Grasland Community, Mangaung in Accessing Basic Services. Doctoral thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Mphambukeli, T. N. (2019). Hailstorms and human excreta: navigating the hazardous landscapes in low-income communities in Mangaung, South Africa. Front Sustain Cities 58, 1–6. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2020.523891

Muchadenyika, D. (2020). Seeking Urban Transformation: Alternative Urban Futures in Zimbabwe. Harare: Weaver Press.

Muggah, R. (2012). Researching the Urban Dilemma: Urbanization, Poverty and Violence. Toronto, IDRC.

Nche, T. N. (2020). Exploring Peripheral Settlements and Public Transport Nexus: Insights From Naledi Trust, Kroonstaad, Free State, South Africa (Masters Dissertation). Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Newman, O. (1973). Defensible Space: People and Design in the Violent City. London: Architectural Press.

Newman, O. (1975). Defensible Space: People and Design in the Violent City. London: Architectural Press.

Nyabvedzi, F., and Chirisa, I. (2012). Spatial security and quest of solutions to crime in neighbourhoods in urban Zimbabwe: case in Marlborough East, Harare. J. Geogr. Reg. Plan. 5, 68–79. doi: 10.5897/JGRP11.047

Oosterom, M. A., and Pswaray, L. (2014). Being a born-free. Violence, youth and agency in Zimbabwe. IDS Research Report 79. London: Institute for Development Studies

Ramakrishnan, K., O'Reilly, K., and Budds, J. (2021). The temporal fragility of infrastructure: theorizing decay, maintenance, and repair. Environ. Plan. E Nature Space 4, 674–695. doi: 10.1177/2514848620979712

Rodgers, D., and O'Neill, B. (2012). Infrastructural violence: introduction to the special issue. Ethnography 13, 401–412. doi: 10.1177/1466138111435738

Schnell, C., Braga, A. A., and Piza, E. L. (2017). The influence of community areas, neighborhood clusters, and street segments on the spatial variability of violent crime in Chicago. J. Q. Criminol. 33, 469–496. doi: 10.1007/s10940-016-9313-x

Silva, P., and Li, L. (2020). Urban crime occurrences in association with built environment characteristics: an African case wth implications for urban design. Sustainability 12, 3056. doi: 10.3390/su12073056

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., and Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Soja, E. (2010). “The city and spatial justice,” in Bret B, Gervais-Lambony P, Hancock C, Landy F, eds. Justices Et Injustices Spatiales (Paris: Presses Univeritaires de Paris Quest), 55–74

Tibaijuka, A. K. (2005). Report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to Assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

Truelov, Y., and O'Reilly, K. (2021). Making India's cleanest city: sanitation, intersectionality, and infrastructural violence. Environ. Plan. E Nature Space 4, 718–735. doi: 10.1177/2514848620941521

Tshili, N. (2021). Burglary Hotspot Suburbs Revealed. Available online at: https://www.chronicle.co.zw/burglary-hotspot-suburbs-revealed/ (accessed March 27, 2022).

Whiz, L. (2021). Pirate Taxi Driver Charged After 21 Women Raped and Robbed in Harare. Available online at: https://www.zimlive.com/2021/08/19/pirate-taxi-mancharged-after-21-women-raped-and-robbed-in-harare/ (accessed March 27, 2022).

Yiftachel, O. (2009). Critical theory and ‘gray spaces': mobilization of the colonized. City 13, 241–256. doi: 10.1080/13604810902982227

Keywords: spatial justice, urban security, emerging human settlement, Hopley, infrastructural violence

Citation: Matamanda AR and Mphambukeli TN (2022) Urban (in) security in an emerging human settlement: Perspectives from Hopley Farm Settlement, Harare, Zimbabwe. Front. Sustain. Cities 4:933869. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.933869

Received: 01 May 2022; Accepted: 20 October 2022;

Published: 17 November 2022.

Edited by:

Shuaib Lwasa, Global Center on Adaptation, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Paul Isolo Mukwaya, Makerere University, UgandaRobert Home, Anglia Ruskin University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Matamanda and Mphambukeli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abraham R. Matamanda, bWF0YW1hbmRhYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Abraham R. Matamanda

Abraham R. Matamanda Thulisile N. Mphambukeli

Thulisile N. Mphambukeli