- 1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU), Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), School of Architecture + Planning, Program in Art, Culture & Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

The goal of this article is to revive and empirically expand the debate on institutional frameworks within commons scholarship. The paper's guiding question is: what kind of institutional framework allows for sustainable commoning in urban conditions? In order to answer this question, we invoke the case of Savings and Credit Associations, a form of financial commoning whereby participants lend each other money and decide, through deliberative sessions, how the money is to be shared. We mobilize data from three decades of ethnographic research in India and The Netherlands, in order to distill the institutional properties that have contributed to Savings and Credit Associations' sustainable existence. The paper's main claim will be that in Savings and Credit Associations' institutional frameworks, a pivotal precondition for sustainable commoning can be found: the combination of a socio-relational (low-scale, trust-based) approach with a reconsideration of the rules at given intervals. In conclusion, we also argue that it's precisely a socio-relational approach which may save commoning's emancipatory potential.

Introduction

In this article, we assess the role of institutional frameworks within commoning practices. The paper's guiding question is: what kind of institutional framework allows for sustainable commoning in urban conditions?

Let us first of all specify the paper's central concepts. With the notion of an institutional framework, we refer to a set of organizational principles that guides commoners' conduct. Devising a set of organizational principles is a task no commoning endeavor can escape. After all, whatever the content of one's commoning project, commoners will sooner or later have to devise its institutional form. Qua “commoning practices,” more specifically, we investigate the case of Savings and Credit Associations, a form of financial commoning, explained in more detail below. In Savings and Credit Associations, commoners lend each other money and decide, through social and deliberative sessions, how the money is to be distributed among the participants. With “sustainable” commoning, lastly, we refer to commoning practices that continue to exist over time.

The paper's main claim will be that in Savings and Credit Associations' institutional frameworks, a pivotal precondition for sustainable commoning can be found: the combination of a socio-relational (i.e., low-scale and trust-based) approach with a reconsideration of the rules at given intervals.

This research endeavor will be relevant for scholars interested in the sustainability of urban commoning, for two reasons. First of all, it is safe to assert that the sustainability of commoning becomes problematic in urban conditions. In contrast to community-led natural commons (such as meadows, forests, irrigation systems), urban commons have “indirect value” (meaning that participants might have different reasons for engaging in the sharing of a resource), are “contested” (meaning that who is to participate in the sharing is not always clear and must be discussed), and are more “heterogenous” (meaning that they are steered by socio-demographically diverse communities). From this, we may derive that in urban contexts, the development of an adequate institutional framework, which allows furthermore for sustainable commoning, is more difficult. However, this study will lay bare the kind of institutional framework which does allow for sustainable commoning: the aforementioned combination of a socio-relational approach with a reconsideration of the rules at given intervals. As will be discussed extensively in the paper's main body: the absence of such a framework leads to over- or under-institutionalization; the presence of such a framework means that the social relations among commoners become central, and consequently, that commoning becomes more sustainable over time.

The paper's second significance for scholars of urban commoning is its theoretical contribution. As argued in the paper's theoretical exposé, commons scholars (see, e.g., Ostrom, 2008; Stavrides, 2015) continue to this day to quarrel over what kind of institutional framework would be most suitable if one is to organize commoning in a sustainable manner. Those working in the footsteps of Ostrom (which we will call “Ostrom's Approach of Institutional Design”) are interested in the discovery and formulation of specific “design principles” (hence: rules of conduct) for sustainable commoning. Those working from a more emancipatory perspective (which we will call the “Emancipatory Approach of Instituent Commoning,” see, e.g., Hardt and Negri, 2009; Stavrides, 2016; De Angelis, 2017) work in a more normative way, arguing that urban commoning requires rules that are “in flux,” rules that are subject to perpetual change. However, the institutional framework proposed in this paper bridges these two poles, and shows that elements of both approaches are necessary for sustainable commoning to unfold. Hence the title of this contribution: “institutionalizing non-institutionalization.”

Savings and Credit Associations can be divided in two main forms: ROSCAs (Rotating Savings and Credit Associations) and ASCAs (Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations). As informal groups, ROSCA members meet at uniformly-spaced intervals in order to pool financial funds in a central common pot. After each meeting, one member receives the entire common pot, but continues to contribute during future meetings. The mechanism repeats itself until each member has received the pot once, after which a new cycle begins. In ASCAs, by contrast, savings will be continuously put in a common fund from which loans, with or without interest, can be provided (Smets, 1996; Biggart, 2001; Rutherford, 2001; Reito, 2020). Based on the organizational methods of ROSCAs and ASCAs, finally, a social movement of “Savings Groups” has seen the light of day, both in the Global South as in the Global North. Given the current upsurge of interest in the relationship between commoning and social movements (see, e.g., Bailey and Mattei, 2013; Susser, 2016; Villamayor-Tomas and García-López, 2018; Pera, 2020; Varvarousis, 2020) we will also turn, albeit as an excursus, to the Savings Groups movement, once more with a specific focus on institutional frameworks.

The paper will be structured as follows. First, we start by assessing what current commons theories have on offer, when it comes to the question of institutional frameworks. In so doing, we distinguish Ostrom's “institutional design” approach from more recent, emancipatory theories that advocate what we shall call “instituent commoning”—the latter being a form of commoning whereby commoners' organizational principles are in flux, flexible, non-institutionalized. Subsequently, we highlight the institutional workings of ROSCAs, ASCAs, and Savings Groups. In the paper's conclusion, finally, we argue that an adherence to a socio-relational approach constitutes a pivotal precondition for sustainable commoning. Whilst largely overlooked by both aforementioned theoretical paradigms, we argue that it is precisely this socio-relational approach which may save commoning's emancipatory potential.

The Role of Institutions in Commons Theorizing

Ostrom's Approach of “Institutional Design”

A study on the role of institutional frameworks should take Elinor Ostrom's approach of “institutional design” as a point of departure (see, e.g., Ostrom, 1990; Dietz et al., 2003; Hess and Ostrom, 2007). In this tradition, Ostrom and her followers investigated how communities of commoners, in the absence of favorable market conditions or adequate governmental regulations, developed the organizational principles (institutions) needed for the self-organized governance of environmental resources. In her landmark study Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Ostrom (1990) showcased that the chances for sustainable commoning would be highest when commoners' organizational principles adhere to a series of overarching “design principles.” In order to proffer sustainable commoning, Ostrom found, commoners should: clearly define group boundaries; match the rules of resource use to local conditions; ensure that fellow-commoners can participate in modifying the rules; develop a system for monitoring fellow-commoners' behavior; deploy sanctions for rule violators; provide accessible and low-cost means of dispute resolution; and have one's commoning project recognized (“not challenged”) by external governmental authorities.

In so doing, Ostrom countered Hardin (1968, 1244) infamous “tragedy of the commons” thought experiment, in which he presumed that when a group of commoners has a shared interest in a collective resource, this situation shall inevitably result in overuse and depletion. “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all,” Hardin noted (Hardin, 1968, 1244). By contrast, Ostrom argued that during real-life situations, commoners are able to effectively communicate with each other, giving them the possibility to jointly define the most suitable institutional framework. Worldwide, Ostrom (1990, 1) wrote, commoners have been able “to devise institutions resembling neither the state nor the market” to keep their commons sustainably alive.

Whilst Ostrom focused in her earlier work on environmental commons (forests, irrigation systems, water basins), it was her colleague Hess and Ostrom (2007; Hess, 2008) who later broadened the practice of institutional design to “various types of shared resources that have recently evolved (…) without pre-existing rules or clear institutional arrangements,” such as: “cultural commons,” “knowledge commons,” “infrastructure commons,” and “neighborhood commons.” Moreover, Ostrom's work has started to resonate more recently in urban contexts (Parker and Johansson, 2011; Iaione, 2015, 2016; Foster and Iaione, 2016). We currently dispose of a growing literature which highlights a trend in municipal governance, namely: the development of legal frameworks allowing urban citizens to become directly involved in the management of urban commons such as parks, green spaces and deserted factories—the “Bologna Regulation for the Care and Regeneration of Urban Commons” is a case in point.

The Emancipatory Approach of “Instituent Commoning”

Today, however, various authors have pushed the existing commons scholarship into a more emancipatory direction (Hardt and Negri, 2009; Stavrides, 2016; De Angelis, 2017; Dardot and Laval, 2019). Commoning, within this current approach, constitutes not merely the joint governance of shared resources as was seen in Ostrom, but rather, the collective quest for a more just and equitable urban society. As such, commoning becomes indeed a political principle. After all, whilst Ostrom's last design principle advocated that commoning endeavors should be merely “recognized” by external authorities, the overall view within current commons scholarship is that commoning should be aimed at the transformation of external authorities (municipal, state, and market). Now, looking specifically at the issue of institutional frameworks, the here-posited emancipatory approach advocates what we shall call instituent commoning, namely: a form of commoning whereby commoners' organizational principles are continuously in flux.

Within this approach, Hardt and Negri demand that commoners' organizational principles be based on “conflict” and “open-ended.” Taking their cue in cybernetic networks, Hardt and Negri (2009, 357, 358) found how commoners' organizational principles can be “continuously transformed by the singularities that compose them.” Dardot and Laval (2019, 304), on their part, argue that one should not ask “what is an institution?”, but rather: “what is an instituent act?”. This question brings the authors to the idea of “instituent praxis,” being both “the activity that establishes a new system of rules and the activity that tries to permanently revive this inaugural act (…).”

Whilst the aforementioned authors conceive of “institutions” in the sense of broad societal practices (marriage, banking, education, etc.), it was Stavrides (2014, 2015, 2016) who most elaborately transferred their insights to the organizational level. Stavrides (quoted in DŽokić and Neelen, 2015, 25) equally proposes to organize commoning through organizational principles that are continuously subject to change:

“[…] I also stress the fact that commoning includes the process in which you define the uses and rules and forms of regulation where you keep this process alive. You need constantly to be alert in avoiding that this process solidifies and closes itself and therefore reverses its meaning. If commoning tends to close itself in a closed society and community, and it defines its own world, with certain classifications and rules of conduct, then commoning reverses itself and simply becomes the area of a public which reflects a certain authority that is created in order to keep this order going as a strict and circumscribed order. Commoning that is not in flux reverses its meaning” (italics added).

Organizing commoning in a state of flux, according to Stavrides, becomes possible through the active avoidance of taxonomic role divisions. After all, vast role divisions could lead to institutionalized power differentials. “If the power to decide,” Stavrides (2015, 549) noted, “is distributed equally through mechanisms of participation, then this power ceases to give certain people the opportunity (…) to impose their will on others.” Stavrides thinks particularly of a constant comparison and translation of roles, positions and viewpoints among commoners, in order to keep the flow of commoning perpetually in flux. One might think of a rotation of duties, such as collecting garbage after a square occupation, or tidying the room after an assembly, but also of the explicit avoidance of a central language, a central set of terms or a single set of rules during commoning practices.

In fact, the struggle to avoid institutionalized power differentials has deep roots in earlier forms of human sociation: Stavrides (2015, 15) points to the ritualistic destruction of wealth, egalitarian food sharing, role reversions during carnival as well as the symbolic sacrifice of leaders. Against this backdrop, ROSCAs become particularly significant. Largely preceding the current “buzz” of commoning in both activism and academia, ROSCAs have long been known as a form of inter-human financial support based on egalitarian principles (Geertz, 1962).

Scholarly accounts in the slipstream of the emancipatory approach can be found in Bresnihan and Byrne (2015), Huron (2015), and Noterman (2016). Nevertheless, a corresponding critique to the emancipatory approach can be formulated. We hypothesize that instituent commoning runs the risk of “liquefication,” with which we mean: an excess in flexibility, potentially causing the cessation of a commoning project altogether. As seen before, ever-present within the instituent approach is the demand that commoners' organizational principles are perpetually in flux. But here too, there is increasing evidence suggesting that (instituent) commoning might become too variable, too volatile, too ephemeral, eventually leading to the extinction of the commoning project after a first (“charismatic”) phase of (non-institutionalized) activity (see, e.g., Argyropoulou, 2012; Volont, 2019).

Interlude: From Theory to the Field

Before us we thus have two theoretical poles: Ostrom's Approach of Institutional Design and the Emancipatory Approach of Instituent Commoning. In the first approach (urban), commons are seen as physical resources demanding a vast set of governance principles. The second approach adds an emancipatory dimension, but as seen before, it runs the risk of “liquefication:” an excess in flexibility.

Whilst we deliberately presented the two approaches as “opposite poles” for reasons of analytical clarity, it must also be mentioned that between these two poles, more nuanced “middle” positions exist as well. The school of “critical institutionalism,” for instance, focuses on the often-complex composition of institutional arrangements, laying bare how the latter may consist of formal and informal rules, of traditional and modern insights, and may come into being through power differentials (see Cleaver and de Koning, 2015 for an overview of the topic). In this field, a social justice lens is often used in order to explain institutional frameworks among commoners. Harvey (2012), too, takes on a middle-position. He describes urban commoning on the one hand as a vehicle for a more just and equitable urban society, a vehicle which on the other hand requires a form of group closure around a designated resource—indeed, a distinctively Ostromian statement. Lastly, notwithstanding our discussion of this author within the emancipatory approach, Stavrides has also issued a more nuanced middle position, especially concerning the configuration of the commoning community. For Stavrides, commoning communities require a certain threshold, a porous perimeter, a fluid membrane. “Thresholds,” Stavrides (2015, p. 12) writes, “may appear to be mere boundaries that separate an inside from an outside, as in a door's threshold, but this act of separation is always and simultaneously an act of connection. Thresholds create the conditions of entrance and exit.”

This paper is equally committed to taking a middle-position between both approaches, in two ways. First, whilst the vast majority of commons scholarship situates itself explicitly in either the Ostromian or in the instituent tradition, we set out to approach our central case by putting these theories temporarily in suspense. In other words: we leave open the possibility that elements of both the Ostrom approach and the instituent approach might surface whilst describing Savings and Credit Associations. Savings and Credit Associations have continued to exist for centuries (de Swaan and van der Linden, 2006), and in so doing, they managed not to over-institutionalize, nor to under-institutionalize. How is this possible? What can their institutional frameworks teach us about sustainable commoning?

Second, we investigate an often-overlooked commons: money. Especially since the emancipatory turn in commons-scholarship (Hardt and Negri, 2009; Stavrides, 2016; De Angelis, 2017; Dardot and Laval, 2019), the concept of the commons has been explicitly contrasted with that of capital. And rightfully so: it is precisely capital's “parasitical gaze” (Hardt and Negri, 2009) that motivates ever-larger groups of urbanites to collectively govern and protect their means of subsistence. Yet, this does not preclude the possibility that money itself —and by extension urbanites' surplus capital—might become a commons. Therefore, we embed the case of Savings and Credit Associations into the field of commons scholarship, a case whereby commoners self-organize around the pooling and sharing of money.

Methodology

As argued before, this article sheds light on the issue of institutional frameworks within commons scholarship by elucidating ROSCAs, ASCAs and the social movement of Savings Groups. For over 30 years, the first author (Smets, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2006; Smets and Bähre, 2004) has been investigating ROSCAs and ASCAs through ethnographic sociological research. This resulted in an extensive ensemble of data and studies concerning the social aspects of more than 100 ROSCAs and ASCAs in Hyderabad (a metropolitan area in central-India), Sangli (a trading center in agricultural products in Maharashtra, India), and Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Let's go back to the course of the nineteenth century. In the Netherlands—just as happened in Western Europe and the USA—Savings and Credit Associations changed into savings banks, and insurance companies, taken over by commercial insurance companies and governmental social insurance schemes (de Swaan, 2006). Today, Savings and Credit Associations are widespread in the Global South. While looking into the different regions in this paper, contemporary ROSCAs and ASCAs are widespread among all sections of society in India, while in the Netherlands the focus is more on people with a migrant background. Moreover, we see that Indian Savings and Credit Associations are characterized by a diversity of institutional design in comparison to the Dutch context. These ROSCAs/ASCAs have been scrutinized through participant observation, in-depth interviewing and through analyzing and processing operational reports of these associations.

In this contribution, we shall combine (previously unused) empirical data from the first author's aforementioned long-term presence in ROSCAs/ASCAs with a re-assessment of that same author's previously published studies concerning commoning in ROSCAs/ASCAs. The material is reused in such a way that it encompasses a new, specific focus on institutional frameworks. As such, we deployed an “iterative approach,” being a “reflexive process in which the researcher visits and revisits the data, connects empirical materials to emerging insights, and progressively refines his/her focus and understandings” (Tracy, 2013, 210). New in this article is that both sources of information have been read through an institutional lens, by asking: what may these sources add to the issue of institutional frameworks within commons scholarship? Thus, our focus here is not on describing the inner workings of one ROSCA/ASCA in particular (“thick description”), but to decipher the institutional mechanisms that run transversally through the multiple ROSCAs and ASCAs that have been investigated by the first author throughout the past three decades (“thick analysis”). Hence: it is form, rather than content, that we are interested in.

After all, our intent is to shed light on the institutional arrangements that allow ROSCAs and ASCAs not to over- and nor to under-institutionalize. Seeking an answer to such question requires us to “zoom out” and therefore to distill data from ROSCAs and ASCAs in general rather than from one or a few ROSCAs and ASCAs in particular.

After the following, main body of the paper on ROSCAs and ASCAs, we finally add a minor excursus to the social movement of Saving Groups, for which we resort exclusively to a literature review.

Commoning in the Case of ROSCAs, ASCAs, and Savings Groups

Savings and Credit Associations can be distinguished in two informal types: ROSCAs (Rotating Savings and Credit Associations) and ASCAs (Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations). We will now discuss both types separately, as well as the social movement of the Saving Groups, before proceeding to an overall theoretical reflection and conclusion.

ROSCAs

ROSCAs can be found around the globe and are popular among men, women and even children. “ROSCA” is a scientific label that is generally used in the literature, but in different regions around the world they are also known as, e.g., chit fund and bishi in India, pasanuku in Bolivia, stokvel in South Africa, susu in Ghana and iqqub in Ethiopia (de Swaan, 2006). Whilst ROSCAs are widespread in the Global South, it is known that global migration has brought these associations to the Global North as well (Hossein, 2017, 2018; Lehmann, 2021).

Within ROSCAs, commoners collect savings as all participants deposit finances in a central common fund. For example, a group of 12 persons joins hands, after which each participant pays the sum of EUR 50 on a monthly basis. Each month, the pot will contain EUR 600, which is then allocated to one person in particular. Thus, after 12 months, each participant will have received the common fund once. The allocation of the common pot can take place in different ways: lottery, auction, negotiation, consensus, seniority, but cases of bribery are also known (Bouman, 1978; Smets, 1992). The auction system in particular requires an explanation. In this case, the common pot will be allocated to the participant who offers the highest discount. This implies that the discount will be deducted from the common pot while the remaining amount will be allocated to the auctioneer who has obtained the lump sum. The deducted amount will finally be divided among the remaining participants.

In ROSCAs, commoners self-organize their institutional framework, namely, their rules and regulations. This requires an ongoing process in which group members participate from the beginning. Hence, time is needed to develop capabilities for institutional design, operation, maintenance and evaluation of the scheme (Menon, 1993). But, as asked before, why is it that ROSCAs continually manage not to over-, and nor to under-institutionalize? In what follows, we shall point to two issues: (1) ROSCAs' reliance on a socio-relational (hence low-scale and trust-based) approach, and (2) ROSCAs' in-built possibility of changing their institutional framework after the termination of a cycle.

Firstly, ROSCAs rely on a socio-relational approach which is based on a low scale and its corresponding levels of trust. As one social worker in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, argued: “it is not only finance that will be dealt with at such a meeting. Sharing food, dancing, playing games, chatting often take place. These activities build trust among each other.” In ROSCAs, different types of trust are at play. The most basic form of trust is “individual trust,” whereby two individuals trust one another (Svendsen, 2014). Then, in contrast to individual trust stands “social trust.” Social trust emerges within a broader group of people and refers to a “positive perception of the generalized other” (Svendsen, 2014); for example, when larger groups of ROSCA commoners did not know each other beforehand but still trust each other. A third type of trust is “ascribed trust,” emerging from one's caste, status and religious relationships (Knorringa, 1999). Within ROSCAs and other forms of human sociation, there is no guarantee that this kind of trust shall be confirmed by trustful behavior. After all, one deducts from a person's social position that s/he would be trustful, but reality shows that this is not necessarily so. However, what we saw emerging particularly in ROSCAs is yet a fourth form of trust: earned trust (Knorringa, 1999). Earned trust emerges from commoners' financial conduct, for example by showing that they have an income, but also from the reputation of social, familial and religious behavior.

Overall: in the case of ROSCAs, commoners are actively committed to retaining their socio-relational bonds so that trust can arise. As one ROSCA commoner in the Netherlands, being a political refugee from the Congo, argued: “knowing and trusting each other are two sides of the same coin” (quoted in Lehmann and Smets, 2020, 909). Thus, by keeping ROSCAs low-scale and by populating them with people that are tied to the same place of living, trust can emerge. Through face-to-face interaction, people pay attention to building positive relationships and a positive reputation.

Despite the proliferation of trust in ROSCAs, commoners have to deal with the fact that urban social life invariably entails risks of some kind, and that in urban conditions, one can never know all of one's fellow-dwellers: one can never entirely judge the financial circumstances of one's peers. As one of the Ghanaian participants in a ROSCA in the Netherlands asked: “If I do not know you, I cannot give you my money” (Lehmann and Smets, 2020, p. 909).

Thus, joining hands based on blind trust is exceptional (but mere “confidence” is not entirely absent) (Smets and Bähre, 2004). Yet, as trust will not emerge ex nihilo, commoners have devised various mechanisms so that trust can be actively created. Against this backdrop, “guarantors” may be turned to (people held responsible for repaying a loan), for instance when a participant fails to contribute to the common pot but has already received his or her share. Moreover, it was also observed how participants may involve children to draw lots for the allocation of the kitty. Finally, commoners may also actively “check upon” others' trustworthiness through social talk and conversation. In this vein, let us take a look at the following statements:

“[…] when I started the chit funds, I asked the people to join. I started with one chit fund with Rs. 5000 and later on added some of Rs. 10.000. But now I think about stopping, because it is too risky. Since four months, I have paid the contributions of one participant. He has already auctioned the fund and has received Rs. 7000 [out of 10.000] and did not turn up anymore. After auctioning, a guarantor, a person who has not yet received the fund, is needed to obtain the fund. I did not ask for a guarantor” (interview with commoner, Hyderabad, India).

“[…] twelve members pay a contribution of Rs. 15 on a daily basis. All transactions are noted down in a notebook. The contributions will be paid at the house of the organizer. The lucky draw takes place every 20 days. The fund will be allocated by letting a child of less than 7 years taking a chit out of a steel box. The lucky draw will take place in front of the house of the organizer. Besides drawing no other social activities will take place” (note after participant observation, Sangli, India).

“[…] when I will start a new chit fund [ROSCA], I will inform the existing members and explain them their rules and regulations. The rules and regulations will not be written down. New members will be screened by looking if they can pay their contributions regularly (…). People in this slum pay regularly. To know more about the background of new members, I will ask existing members to become a guarantor” (interview with commoner, Hyderabad, India).

Finally, ROSCAs are characterized by the in-built possibility of changing their institutional framework after the termination of a cycle. Should untrustful behavior still occur, ROSCAs will invoke a unique organizational operation: the institutional arrangement of one cycle (which runs until each commoner has received the common fund once), can be entirely redrafted when a new cycle begins. Participants may decide whether they restart a cycle on the same terms as used before, but the rules can also be adapted, for example when the experiences of the previous cycle make an adaptation of the rules necessary. For example, members who did not pay their monthly contributions in time can be excluded from participation during the next cycle or be permitted to participate once they have saved enough. As seen in this statement by a ROSCA commoner from Hyderabad, India:

“[…] the contribution became Rs.15 instead of Rs. 10 in the previous cycle. The rules and regulations were the same. In the first chit fund we had three persons who were not paying their contributions regularly. In the second this problem was solved. The defaulters of the first cycle were not allowed to participate in the second cycle.”

Hence: in ROSCAs, it is not only a matter of finance or financial commoning per se. We learn that rule-making does not only evolve around the commoning of financial resources, but also, and more so, about the generation of trust and the possibility of changing rules autonomously. To get an insight into this matter, we quote at length from an observation report drafted in Sangli, India:

“When some female members arrived, they said hello to the host women, who was busy in the kitchen. Other women quickly went into the living room to meet their friends who were already seated. The host woman and her female family members served snacks. In the meantime, the bishi (ROSCA) participants show each other their new sarees (Indian clothing for women) and ornaments. When the tea was served, the women exchanged news about television programs, new movies in the cinema, functions in the temple and new books. Furthermore, their children were favorite topics to talk about. The women seemed very willing to talk to one another and to give moral support to those women who faced difficulties at home. At the meeting, the hostess wrote the names on pieces of paper. A small child was asked to take one of the lots: the woman whose name was drawn was to be the hostess for the next meeting. She fixed a date and invited all other participants.

The women pointed out different alternatives to me if a woman is not in a position to receive all the women at home. Then, the host can invite all bishi participants for a dinner in a restaurant. In such a situation, the hostess has to bear the costs of the dinner.

One woman proudly said that her husband had just bought a new car. This news encouraged the other women to ask for a party with snacks or a dinner at the house of the couple concerned. One woman added that a visit to the cinema would also be appreciated. The secretary wanted to collect all the contributions of Rs. 100, which was noted down in a notebook. The total fund of Rs. 1,100 was handed over to the hostess. At this moment one woman proudly showed me the ring she had bought from the bishi fund.

Some women had to pay a penalty of Rs. 2 for non-attendance during the last meeting. They said that they had not been able to come because of, for example, unexpected visitors. Penalties would not be charged if a woman was absent at a bishi meeting due to illness or a funeral in the family. The size of the penalty for not appearing at the Hindu festival or Makar Sankranti was as much as Rs. 5. The secretary collected all the penalties and noted them down. At the end of the cycle this money is used for a visit to the cinema. At the end of the meeting, the hostess gave a demonstration of the preparation of the snacks she had prepared.

“In December, the last month of the bishi cycle, the women usually organize a gathering for the participants and their family members, including the men. During the other meetings men are not allowed” (Smets, 2006, 167–168).

ASCAs

In ASCAs1, savings are put in a common fund from which loans, with or without interest, can continuously be provided. Part of the fund can be used for emergency issues, community development and joint investments (Bouman, 1995, 376). Credit can be provided at different intervals, such as on a weekly and a monthly basis. Reminiscent of ROSCAs, the allocation of a loan may be determined by way of first-come-first-served, consensus, negotiation, seniority, bribery, and decision of the organizer. Organizers may decide to consider the repayment capacity of the borrower as participants generally take out one or more loans. Repayments can take place in installments or in lump sum. Finally, participants who do not ask for credit can use ASCAs for saving purposes.

The most important difference with ROSCAs is that the number of participants can be much higher. Smets (1992) traced ASCAs with more than 1,000 members in Sangli, India. However: when scale increases, trust decreases. Accordingly, given the lower level of socio-relational control over the joint funds, management may become increasingly engrained in the hands of a few. Under such circumstances, an authoritarian approach starts to dominate. This also differs from ROSCAs, where a democratic approach is adhered to. For example, a large Indian ASCA in the 1970s consisted of hundreds of members. The ASCA collapsed as the participants did not trust each other anymore. It took years before people started trusting each other again and dared to start a new ASCA (Smets and Bähre, 2004). Let us take a look at the following statement from an ASCA commoner in Hyderabad, India, pointing to the danger of non-circulating money within the ASCA:

“[…] when money is lying unused, the organizer may lend it to one of the members just as the elders did. Non-members can borrow when it is very urgent, for instance for food and medical treatment. The maximum loan size is Rs. 150. If more people apply for a loan, then the amount may be shared among more people. The borrowed money should be repaid before the common fund will be distributed among all participants.”

In order to cope with decreased trust, guarantors may once again be turned to. Such a person is held responsible for the repayment of a loan or payments to the kitty. As the organizer of an Indian ASCA said: “for each loan a guarantor is needed. This guarantor should be a person who is not borrowing from the fund at this moment. This is to ensure repayment of the loan.” Nevertheless, many assume that default is widespread. As an ASCA organizer in Hyderabad noted:

“[…] when there is faith, managing a chit fund is a good business. When you organize a chit fund you have to move along with the people. Running a chit fund is not a joke. If somebody is not paying, he has to visit these people or pay it himself. When some people go to villages for business purposes, I have to go behind them to collect the money from them. There are difficult cases.”

However, when asked whether such cases have effectively happened, the respondent said: “no.” This is remarkable. This organizer sees risks, but in practice it rarely happens. The manager knows that when the social capital declines an authoritarian management approach becomes ingrained in the hands of a few. Still, the organizer keeps an eye on the other board members which restricts default. That is why so far nothing has happened.

Excursus: Savings Groups as a Social Movement

In this excursus, we want to highlight how, inspired on the ROSCA/ASCA model, a social movement of savings groups has seen the light of day. Field workers and the related financial organizations have spread the phenomenon of savings groups in many countries in especially the Global South. As we will show below, the savings groups movement has created an organizational mechanism which places the socio-relational approach central. Savings groups' institutional frameworks are (1) time-bound (as people get their savings back at the end of an annual cycle); (2) democratic (based on transparent procedures, all of which are carried out in front of the members); and (3) self-organized (managed by its member-owners, who keep the profits). In all, by creating simple and transparent institutional frameworks, the focus is on the process of commoning itself rather than on blueprint outcomes.

In the early 1990s, development organization CARE Niger developed Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs), inspired on the ROSCA and ASCA models. As such, the savings component has been copied and the possibility of taking out a one-month loan from a common fund has been added (Allen and Panetta, 2010, 3). The success of these saving groups encouraged other NGOs to develop variations of the VSLA model. Examples include Savings for Change (SfC) by Oxfam/Freedom from Hunger/Strømme Foundation; Saving and Internal Lending Community (SILC) by Catholic Relief Services; and Community Based Savings Groups by the Aga Khan Foundation (Mersland et al., 2019). In 2020, the VSLA model entailed 20 million active participants, spread over 77 countries around the globe2.

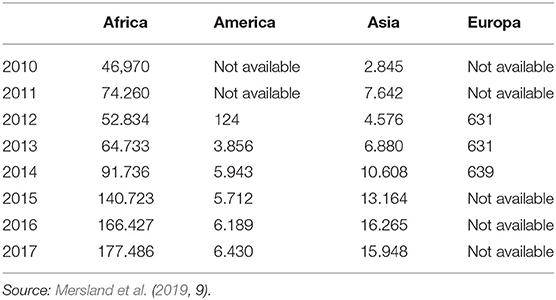

In general, 65% of saving groups are located in rural areas. Only 2% of the projects that report to the SAVIX3 database works in urban areas, and 33% have a combination of a rural and urban orientation (Mersland et al., 2019). Moreover, Table 1 shows that we can witness a growth of saving groups in Africa, America and Asia, while Europe tends to stay behind. One should take into account that the figures in Table 1 show only indications. Not all data are accessible or available. In recent years, more saving groups mushroom in European countries such as Spain, Italy, Germany and the Netherlands (Lehmann and Smets, 2020; Meyenfeldt et al., 2021).

Groups can become independent within ~1 year and the survival rate of the initiated schemes is more than 90% on the long term. Apart from financial benefits, the main benefit is the formation of social capital for group members and leaders/organizers. Allen and Panetta (2010) report that previous research has highlighted “the social cohesion, solidarity, and mutual aid that the savings group engender.” Women say that they feel less vulnerable and isolated and consider the saving groups as being their own. Once their economic situation improves, they are often eager to join hands for collective action to deal with community needs (Allen and Panetta, 2010). Saving groups equally entail additional activities, such as the quest for empowerment, business education, a social fund for emergencies, health programs and development initiatives (Mersland et al., 2019).

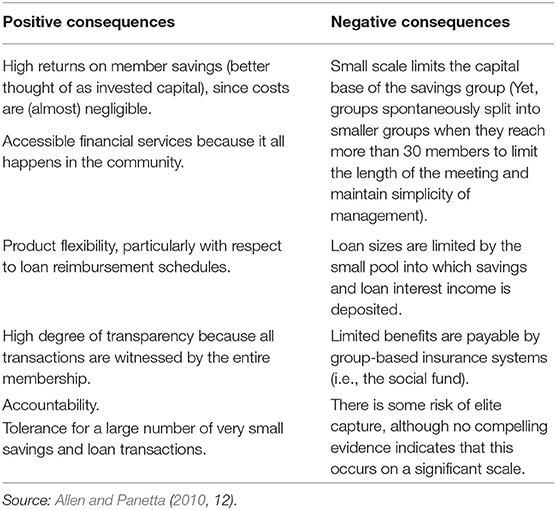

Savings groups have strict management procedures, which may differ among agencies, to simplify financial procedures and to make them transparent for participants. Therefore, agencies made financial bookkeeping forms that participants have to fill in at every meeting. This offers insights in all activities that have taken place. To avoid mismanagement and fraud, the life cycle is set at a maximum of 12 months, which is reminiscent of ROSCAs' operational schemes. As Mersland et al. (2019, 6) argue: “at the beginning of the cycle, groups are constituted, groups leaders are elected and a constitution to govern the group activities is established. The constitution stipulates the contribution by each member, the meeting frequency, penalties for member indiscipline, the procedure to be followed to request for a loan, interest rates on borrowing, etc.” Table 2 gives us some insight into the positive and negative implications of the savings groups model.

However, as was equally seen in the case of ROSCAs and ASCAs, blind trust among commoners is rarely the case. Hence, in the case of Savings Groups too, mechanisms are installed in order to counter default and misuse. Many Savings Groups have lockable cash boxes with three locks and three different keys. Three members, who are a member of the management committee, each have a key. The amount stored in the box depends on the loan demand. These boxes are not only used for security, but also guarantee that transactions can only take place during in-person meetings. This creates an awareness among the members of all savings, of loan transactions, of balances and insurances, which in turn increases and maintains trust and socio-relationality. At the end of the cycle, a great deal of money will be in the box. Under such circumstances the risk for theft is higher, but rare cases are reported about theft in urban areas and areas characterized by civil disorder. Finally, there are a number of initiatives in order to counter the risk of theft: distributing the money equally among the members during each meeting; delaying the repayment of the late-cycle loans to the last meeting; giving the box to a different member at each meeting, so that its storage location is not common knowledge; storing money on mobile phones (still in its infancy, but working successfully in Nairobi slums); and depositing surplus funds in a bank (typically an option in urban areas) (Allen and Panetta, 2010, 20).

Discussion and Conclusion

Our aim has been to elucidate the crossroads between urban commoning and institutional frameworks. The paper's question was: what kind of institutional framework allows for sustainable commoning in urban conditions? Our journey began by analytically contrasting the “Ostrom Approach of Institutional Design” and the “Emancipatory Approach of Instituent Commoning.” ROSCAs, ASCAs, and savings groups helped us to identify the institutional elements for sustainable commoning. It is difficult to identify the differences between urban and rural financial commons due to the hidden nature of these informal phenomena. Nevertheless, our analysis allowed us to provide insights in the operation of commons in specific contexts (ROSCAs, ASCAs, savings groups, which we shall now embed in a two-fold conclusion.

A first conclusion, will be this: a pivotal precondition for sustainable commoning is the combination of a socio-relational approach with a reconsideration of the rules at given intervals. As such, the insights of the Ostrom approach and the instituent approach are not mutually exclusive. Firstly, when considering Savings and Credit Associations longitudinally, we encountered throughout the cycles an “instituent praxis” (Dardot and Laval, 2019) of continuous rule-making and rule-transforming, whilst within the cycles, we encountered a vast institutional design through Ostromian elements. Heavily resembling Ostrom's “design principles for governing the commons,” commoners were seen to define group boundaries (by keeping their endeavors low-scale and local); to develop a system for monitoring fellow-commoners' behavior (for example through guarantors); to deploy sanctions for rule violators (obligatory payback, exclusion, loss of trust and reputation); and to provide accessible and low-cost means of dispute resolution (given their democratic rather than authoritarian approach).

During such cycle, commoners remain personally committed to each other in a “common cause” (in our case: the pooling and allocation of financial means)—which we consider to be a pivotal precondition for commoning that does not over-, nor under-institutionalizes. Hence, a socio-relational approach as seen in Savings and Credit Associations allows commoners to take up the task of defining and maintaining their organizational principles, but also to willingly redefine and reformulate them during future commoning cycles. Relatedly, in the article's main empirical section, we wrote extensively about the issue of trust: in this vein, trust can be seen as the “cause and consequence” of the here-posited socio-relational approach.

A suitable proof of the previous statement can be found in our comparison between ROSCAs and ASCAs. ROSCAs, on the one hand, were seen to keep their institutional arrangements low-scale, local and personal, which adds to the continuous avoidance of institutionalized power differentials. ASCAs, on the other hand, where the number of participants can be much higher, were seen to be plagued by a decline in socio-relational control over the joint funds (to whom they are lent and for what purpose) and thus also by a corresponding decline in trust. Indeed: an increasing number of participants demands a more authoritarian mode of governance through which rules and regulations are set. Against this backdrop, we turned extensively to the social movement of the Savings Groups in order to highlight that it was precisely ROSCAs' socio-relational approach in which this movement found its inspiration. We can thus conclude that socio-relationality on the one hand, and institutionalization on the other, are at odds with one another: two opposite poles on an organizational continuum. A decrease in socio-relationality goes hand in hand with an increase in institutionalization, and vice versa.

Nevertheless, the proponents of what we called the emancipatory school of instituent commoning, would continue to argue: “when focused so much on a socio-relational approach, where can we then find commoning's transformative, emancipatory potential?”. This brings us to a second conclusion. Our response to this rightful remark is that the here-proposed socio-relational approach generates social capital, which is precisely the point where commoning's transformative potential begins. It is no coincidence, after all, that Allen and Panetta (2010) pointed to the generation of social capital and empowerment to explain the success of the savings groups movement. Indeed, by being engaged in a “common cause,” commoners become part of what Wenger (1999) once called communities of practice: communities in which they learn, through mutual relationships of responsibility, to take care of hot money (money seen as “ours,” as opposed to “cold money” which is controlled by external agencies) (Wright, 2000). Looking into the future, we suspect that it's these communities' horizontal replication—a growing in number, rather than in size—that might bring about the social transformation that the emancipatory approach, as well as the authors, deeply desire. Indeed: as more and more urbanites gain skills, social capital, and a commoning mindset at the level of the grassroots, new ways of thinking about and relating to money might be generated at the macro-societal level. It is here where social movement organizing, despite its challenges as mentioned in this contribution, might play a pivotal role.

Finally, whilst this paper was largely based on empirical cases from the Global South, we intend our findings to be useful for commoners and civil society agents in the Global North as well. As seen in the paper's theoretical exposé, during the current “buzz” of commoning in first world cities, the practice continues to be plagued by either the process of institutionalization—rules becoming too vast, too rigid, for example through municipal regulations—or liquefication—rules becoming too loose, too flexible, eventually leading to the extinction of the commoning project after a first (“charismatic”) phase of (non-institutionalized) activity. Commoners, hence, continue to struggle and search for suitable organizational frameworks in order to organize commoning in a sustainable way. With this in mind, it is sincerely hoped that this contribution might have disclosed valuable pathways to support such a struggle.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

The empirical data came from PS, the theoretical framework came from LV. Data analysis was done mainly by PS, even though LV also engaged in assessing at the data. All authors equally engaged in designing the basic outline and premises of the article, writing, and revising. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The term ASCA comes from Rutherford (2000). Earlier, they were named “non-rotating” savings and credit associations and ASCRA—accumulating savings and credit associations (Bouman, 1995).

2. ^Retrieved from homepage of VSL Associates via https://www.vsla.net.

3. ^As read on the SAVIX homepage: “SAVIX is the only reporting system that provides standardized and up-to-date reports on Saving Groups programs worldwide. By collecting, validating and visualizing financial and operational data from about 600.000 saving groups across Africa, APAC and LATAM, covering 13 million members, it enables benchmarking and informed decision-making, critical for ensuring high-quality program results and helps to set national, sub-regional and continental norms” http://thesavix.org/.

References

Allen, H., and Panetta, D. (2010). Savings Groups: What Are They? Washington, DC: Savings-Led Financial Services Working Group.

Argyropoulou, G. (2012). Embros: twelve thoughts on the rise and fall of performance practice on the periphery of Europe. Perform. Res. 17, 56–62. doi: 10.1080/13528165.2013.775763

Bailey, U., and Mattei, U. (2013). Social movements as constituent power: the Italian struggle for the commons. Indiana J. Global Legal Stud. 20, 965–1013. doi: 10.2979/indjglolegstu.20.2.965

Biggart, N. (2001). “Banking on each other: the situational logic of rotating savings and credit associations,” in Advances in Qualitative Organization Research, Vol. 3, eds J. A. Wagner, K. D. Elsbach, and J. M. Bartunek (Stamford, CT: JAI Press), 129–153.

Bouman, F. J. A. (1978). Indigenous savings and credit societies in the third world. Dev. Dig. 26, 36–47.

Bouman, F. J. A. (1995). Rotating and accumulating savings and credit associations: a development perspective. World Dev. 23, 371–384. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(94)00141-K

Bresnihan, P., and Byrne, M. (2015). Escape into the city: everyday practices of commoning and the production of urban space in Dublin. Antipode 47, 36–54. doi: 10.1111/anti.12105

Cleaver, F. D., and de Koning, J. (2015). Furthering critical institutionalism. Int. J. Commons 9, 1–18. doi: 10.18352/ijc.605

Dardot, P., and Laval, C. (2019). Common: On Revolution in the 21st Century. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

De Angelis, M. (2017). Omnia Sunt Communia: On the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism. London: Zed Books Ltd.

de Swaan, A. (2006). “Mutual funds: then and here, now and there. Informal savings and insurance funds in the nineteenth-century west and the present non-western world,” in Mutualist Microfinance: Informal Savings Funds From the Global Periphery to the Core?, eds A. de Swaan and M. van der Linden (Amsterdam: Aksant), 11–30.

de Swaan, A., and van der Linden, M. (2006). Mutualist Microfinance: Informal Savings Funds From the Global Periphery to the Core? Amsterdam: Aksant.

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., and Stern, P. C. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons. Science 302, 1907–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1091015

DŽokić, A., and Neelen, M. (2015). Instituting commoning. Footprint 16, 21–34. doi: 10.7480/footprint.9.1.897

Foster, S., and Iaione, C. (2016). The city as a commons. Yale Law Policy Rev. 34, 281–349. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2653084

Geertz, C. (1962). The rotating credit association: a 'middle rung' in development. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 10, 241–263. doi: 10.1086/449960

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science 162, 1243–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

Hess, C. (2008). “Mapping the new commons [conference presentation],” in 12th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons (Cheltenham: University of Gloucestershire).

Hess, C., and Ostrom, E. (2007). Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Hossein, C. S. (2017). Fringe banking in Canada: a study of rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs) in Toronto's inner suburbs. Can. J. Nonprofit Soc. Econ. Res. 8, 29–43. doi: 10.22230/cjnser.2017v8n1a234

Hossein, C. S. (2018). “Building economic solidarity: Caribbean ROSCAs in Jamaica, Guyana, and Haiti,” in The Black Social Economy in the Americas, ed C. S. Hossein (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 79–95.

Huron, A. (2015). Working with strangers in saturated space: reclaiming and maintaining the urban commons. Antipode 47, 963–979. doi: 10.1111/anti.12141

Iaione, C. (2015). Governing the urban commons. Italian J. Public Law 7, 170–221. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2589640

Iaione, C. (2016). The co-city: sharing, collaborating, cooperating, and commoning in the city. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 75, 415–455. doi: 10.1111/ajes.12145

Knorringa, P. (1999). “Trust and distrust in artisan-trader relations in the agra-footwear industry,” in Trust & Co-operation: Symbolic Exchange and Moral Economies in an Age of Cultural Differentiation, eds P. Smets, H. Wels, and J. van Loon (Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis), 67–80.

Lehmann, J.-M. (2021). Balancing the social and financial side of the coin: an action research on setting up financial self-help groups in the Netherlands (dissertation). Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Lehmann, J.-M., and Smets, P. (2020). An innovative resilience approach: financial self-help groups in contemporary financial landscapes in the Netherlands. Environ. Plann. A Econ. Space 52, 898–915. doi: 10.1177/0308518X19882946

Menon, L. (1993). “Urban credit - UBSP experience [conference presentation],” in Composite Credit Mechanism for the Urban Poor Conference (New Delhi: Habitat Polytech).

Mersland, R., D'Espallier, B., Gonzales, R., and Nakato, L. (2019). What Are Savings Groups? A Description of Savings Groups Based on Information in the SAVIX Database. Agder: University of Agder.

Meyenfeldt, L., von Mateman, H., and van den Bosch, A. (2021). Theoriegestuurde Effectevaluatie Spaarkringen Cash2Grow. Utrecht: Movisie.

Noterman, E. (2016). Beyond tragedy: differential commoning in a manufactured housing cooperative. Antipode 48, 433–452. doi: 10.1111/anti.12182

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2008). Institutions and the environment. Econ. Affairs 28, 24–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0270.2008.00840.x

Parker, P., and Johansson, M. (2011). “The uses and abuses of Elinor Ostrom's concept of commons in urban theorizing [conference presentation],” in Cities Without Limits Conference (Copenhagen).

Pera, M. (2020). Potential benefits and challenges of the relationship between social movements and the commons in the city of Barcelona. Ecol. Econ. 174, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106670

Reito, F. (2020). Roscas without sanctions. Rev. Soc. Econ. 78, 561–579. doi: 10.1080/00346764.2019.1693054

Smets, P. (1992). “My stomach is my Bishi: savings and credit associations in Sangli, India,” in Urban Research Working Papers 30 (Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam).

Smets, P. (1996). Community-based finance systems and their potential for urban self-help in a New South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 13, 173–187. doi: 10.1080/03768359608439887

Smets, P. (2000). ROSCAs as a source of housing finance for the urban poor: an analysis of self-help practices from Hyderabad, India. Commun. Dev. J. 35, 16–30. doi: 10.1093/cdj/35.1.16

Smets, P. (2006). “Changing financial mutuals in urban India,” in Mutual Microfinance: Informal Savings Funds from the Global Periphery to the Core?, eds A. de Swaan and M. van der Linden (Amsterdam: Aksant), 151–182.

Smets, P., and Bähre, E. (2004). “When coercion takes over: the limits of social capital in microfinance schemes,” in Livelihood and Microfinance: Anthropological and Sociological Perspectives on Savings and Debt, eds H. Lont and O. Hospes (Delft: Eburon), 215–236.

Stavrides, S. (2014). Emerging common spaces as a challenge to the city of crisis. City 18, 546–550. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2014.939476

Stavrides, S. (2015). Common space as threshold space: urban commoning in struggles to re-appropriate public space. Footprint 16, 9–20. doi: 10.7480/footprint.9.1.896

Susser, I. (2016). Considering the urban commons: anthropological approaches to social movements. Dialect. Anthropol. 40, 183–198. doi: 10.1007/s10624-016-9430-9

Tracy, S. J. (2013). Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Varvarousis, A. (2020). The rhizomatic expansion of commoning through social movements. Ecol. Econ. 171, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106596

Villamayor-Tomas, S., and García-López, G. (2018). Social movements as key actors in governing the commons: evidence from community-based resource management cases across the world. Global Environ. Change 53, 114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.09.005

Volont, L. (2019). DIY urbanism and the lens of the commons: observations from Spain. City Commun. 18, 257–279. doi: 10.1111/cico.12361

Wenger, E. (1999). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Keywords: commons, commoning, institutions, institutionalization, credit, saving, social movements

Citation: Smets P and Volont L (2022) Institutionalizing Non-institutionalization: Toward Sustainable Commoning. Front. Sustain. Cities 4:742548. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.742548

Received: 16 July 2021; Accepted: 13 March 2022;

Published: 06 April 2022.

Edited by:

Markus Kip, Humboldt University of Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Tischa A. Munoz-Erickson, United States Forest Service (USDA), United StatesHossein Niavand, University of Mysore, India

Copyright © 2022 Smets and Volont. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Louis Volont, bG91aXMudm9sb250QHVhbnR3ZXJwZW4uYmU=

Peer Smets

Peer Smets Louis Volont

Louis Volont