- Department of Humanities, College of Arts and Sciences, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Qatar has developed a strategy of sustainable tourism and development, which focuses on highlighting the spirit of the Qatari identity and heritage. This strategy goes hand in hand together with the line of the Qatar National Vision 2030. Hence, Msheireb Properties, which is a real estate development company and a subsidiary of Qatar Foundation, focuses in developing a sustainable tourism strategy. Thus, Qatari cultural heritage presented in the heart of the post-modern futuristic city of Msheireb through the project of Msheireb Museums that are hosted in four traditional houses. Msheireb Properties renovated the four houses in a sustainable way that aimed to create a dynamic relationship between tourism and cultural heritage. Msheireb Properties preserved models of traditional architecture through the establishment of Msheireb Museums. This article discusses the development of sustainable tourism in Qatar and the preservation of the Qatari cultural heritage and identity through the story of two museums in Msheireb, the Radwani House Museum and the Company House Museum.

Introduction

The relationship between the past and the present is vital, as the past is an integral tool for building both the present and the future. Attempts to preserve the cultural heritage of nations vary, as some societies try to highlight their cultural uniqueness from others (Al-Saadani, 2017). For example, China sent a few Terracotta soldiers to an exhibition at the Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar, and this loan contributed to promoting the Chinese nation's legacy outside of its borders (Qatar Museums, 2017). China also created a traditional dress for itself in the 1960s, to be unique from its neighbors Japan and Korea (Lau, 2010).

A nation's heritage supports a better appreciation for the history and nobility of the state. Architectural legacies are particularly important. Architectural styles indicate the possibilities of materials and styles that were available locally or imported from the neighborhood through the trade existing at the time and what distinguishes one region from another. Analyzing the architecture, in terms of size, materials, luxury, and the age of its construction, helps illuminate the extent of the state's capabilities and economic factors during different historical periods. More importantly, the preservation of a nation's architectural heritage is a fundamental tool for ensuring sustainable tourism.

The Concept of Sustainable Tourism

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization and United Nations Environment Program, sustainable tourism is an approach that takes full account of its present and future environmental and social impacts and economic influences while addressing the needs of the industry, visitors, and host communities. It implies that sustainable tourism focuses on sustainable practices and impacts in and by the tourism sector. The key stakeholders in the industry acknowledge its impacts, both negative and positive1.

In Qatar, the primary focus of sustainable tourism is to minimize the negative impacts while maximizing the positive ones. Analytically, the negative impacts on tourism to a particular destination include damages to the natural environment, overcrowding, displacement, and economic leakage. For instance, sustainable tourism resulted in massive displacement of the original inhabitants and communities in the Msheireb area before its development. Equally, due to the cost of access, some lower-class communities find it challenging to access the newly developed sites. It implies that sustainable tourism comes with a cost that different stakeholders within the immediate environment have to pay for success to achieve.

However, tourism's positive impacts on its destination include cultural heritage preservation, job creation, wildlife preservation, cultural interpretation, and landscape restoration. In its entirety, sustainable tourism takes a holistic approach that looks at the socio-cultural, environmental, and economic aspects of tourism development. It implies that for excellence to be achieved in sustainable tourism, key stakeholders must strike a balance between the three core dimensions to ensure its long-term sustainability (Trahant, 2018; Waheeb and Zuhair, 2018).

Globally, sustainable tourism has made tourism a significant economic activity in and around protected sites, forests, museums, and other attraction points. Well-planned sustainable tourism programs can create opportunities for the visitors to experience human communities, interact with natural areas, and actively learn about the significance of local culture and conservation needs (Pedersen, 2004). As such, it remains imperative to outline the triple bottom line of sustainable tourism as per the International Ecotourism Society.

Economically: Sustainable tourism works to contribute to the overall economic well-being of the immediate environment. It generates equitable and sustainable income and resources for the local community, stakeholders, and shareholders within the area. The activities involved in sustainable tourism have a direct benefit on neighbors, owners, and employees. However, there are situations where detrimental impacts could be witnessed through the displacement of communities2.

Environmentally: The activities of sustainable tourism have a low impact on natural resources. It strives to minimize the damage to the habitats, flora and fauna, marine resources, water, and energy. In totality, it works to benefit the overall environment and the people interacting with it.

Socially and culturally: As revealed by the International Ecotourism Society, activities involved in sustainable tourism do not harm or interfere with the culture or social structure of the community. Instead, it values and respects the norms, values, traditions, and cultures of local people. It creates a collaborative shareholding of communities, governmental institutions, individuals, tour operators, and communities in planning, developing, evaluating, and monitoring diverse roles in conservation3.

In totality, the conceptual exploration has shown that sustainable tourism strives to meet the needs and preferences of present host regions, tourists, and stakeholders while offering opportunities and protecting the environment and biodiversity for the future. It guarantees that sustainable management of all-natural resources is done in a manner that social, economic, and aesthetic needs are fulfilled while enhancing the vital ecological processes, cultural integrity, life support systems, and biological diversity. In the context of sustainable tourism, Qatar is one country that has focused on tourism as a cultural, economic development strategy.

As a cultural and economic development strategy, sustainable tourism strives to utilize available resources for the social, economic and aesthetic well-being of both locals and foreign tourists. It also protects resources and opportunities for future generations. It stresses safeguarding and protecting the traditions and cultural heritage of communities. It seeks to preserve historical resources for future generations by using tourism to prevent undesirable socio-economic impacts and to promote local communities socially and economically (Vehbi, 2012). Sustainable tourism also encounters the contemporary needs of tourists and host countries by managing a state's resources, while preserving its cultural heritage and promoting essential ecological development (Pedersen, 2004).

Qatar's Socio-Historical Transformation

Heritage plays a critical role in Qatar's socio-historical transformation as it links the people with their culture and history while offering a sense of identity. Qatar's heritage resources have been having a significant impact on tourism. Although Qatar's heritage has been a source of pride, the increased modernization of cities such as Doha has seen historical buildings, districts, and centers become victims. They are brought down and replaced with modern buildings. Even though heritage preservation still thrives in Qatar, the rapid disappearance of the historically developed fabric of the nation has been a concern as it is difficult to retain the real-feel heritage retention. It remains imperative to integrate the concept of heritage, social identity, and history when exploring sustainable tourism in Qatar (Vehbi, 2012).

Historically, Qatar began being inhabited in the early fourth Century. However, much of the history is traced to the eighteenth Century after the Al-Thani family emerged as the first rulers of the nation. The desert situation of Qatar's environment affected the establishment of human settlement due to the harsh and unbearable hot climate. As a result, many opted to live along the coast with the renowned old settlement known as Al-Bidda. Around the 1800s, the Al-Thani decided to relocate to the coast, where they established Doha as the main settlement next to Al-Bidda. By 1887, it was placed as a British protectorate. To date, Doha, the capital of Qatar, has transformed with high rising physical and economic developments due to the increase in revenue from petroleum resources.

Analytically, the urbanism and architecture of Qatar provide the eminent image of the urban identity and cultural heritage transformation that has occurred in residential architecture and the built environment. Irrespective of the transformation, one concept that has remained the same is the tradition and social identity as expressed through the practices of the Qatar people. The practices are actively shared through the Islamic world and the region as a whole. Qatar's vision 2030 has worked with a core focus of embracing tourism as a critical cultural, economic development strategy. It thrives under Qatar's vision 2030's four pillars: environmental development, economic development, human development, and social development. It works to bridge the gap between the present and the future generation (Qatar, 2019).

Owing to Qatar's massive development, its rich culture and heritage, history, and globally recognized growth, it has captured tourism as a cultural, economic development strategy by offering visitors an opportunity to view the beautiful contrast between the past and the future presented in a single frame. Among the most notable transformations are the rising and modern-designed technology parks, over 1,400 years of Islamic history, and integration of tradition and modernity seated side by side within the majestic desert landscapes. In order to sustain its tourism, Qatar has adopted the concept of sustainable tourism as reflected through the activities of Msheireb museums.

In 2011, Qatar launched the Qatar National Vision 2030 that provides the blueprint and guidance to its sustainable economic diversification and long-term development. The plan harbors tourism as a designated priority industry. It serves the country with opportunities to build and achieve sustainable economic growth while enhancing its natural and cultural gems. Equally, in 2014, the Qatar Tourism Authority developed the Qatar National Tourism Sector Strategy 2030 that designs the pathway through which the country will achieve sustainable development for the tourism sector by 2030. The dedication by the sustainable tourism teams through QNTSS 2030 has seen the country welcome over 9 million new visitors. More importantly, the average annual growth of the tourism sector's arrivals has grown from insignificant numbers in the 1990s to over 6% between 2012 and 2016. Such growth has been reflected with a 4.3% increase impact on total Qatar's GDP. Critically, the advancement in modern Qatar's tourism sector has proved the significant social-historical transformation of the country and the reliance on tourism as an important cultural, economic development strategy4.

The current state of Qatar connects the concept of sustainable tourism with the broader themes of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG Goal 8, 12, and 14 aligns with Qatar's sustainable tourism concept. SDG goal 8 strives to promote inclusive, equitable, decent work and sustainable economic growth. It works to ensure productive employment for all. Goal 12 focuses on guaranteeing responsible consumption and production. Sustainable tourism in Qatar has worked to reduce the increasing trend in toxic waste products through the adoption of technology and innovation. Equally, it has adopted the environment protection and conservation concept to maintain the value held by natural resources. Local authorities are also actively involved in the protection of natural gems to ensure that the heritage of Qatar is well-preserved (Qatar, 2019).

Additionally, the tourism sector in Qatar strives to conserve marine resources in the region. The dedication aligns with SDG goal 14 that works to conserve and sustainably utilize seas, oceans, and marine resources for guaranteed sustainable development. Through the climate change programs and initiatives, Qatar's tourism sector has attained its sustainable tourism milestones that have increased the conservation objectives and visitor footprints to its tourism areas associated with economic and financial income for the country.

As highlighted by Hmood et al. (2018), one of the most important sources for the diversification of a country's financial income is tourism. Over the last century, the tourism industry in the world has grown rapidly. Consequently, cultural heritage tourism has become an important source of income for many nations. Investment in cultural heritage tourism has convinced many states of the importance of the preservation and utilization of their cultural heritage. Such tourism has become trendy and is a significant tool in terms of promoting sustainable development. Accordingly, countries have invested their resources to develop the country's architectural heritage and advertise their unique heritage.

Natural resources have been a game-charge in the tourism and development milestones covered by Qatar. With the discovery of oil, life in Qatar changed and developed rapidly, including the development of various professions and architectural designs, and changes in the social life and traditions of Qatari families. To illustrate such changes, four historical houses were converted into museums at Msheireb heritage downtown, located in the heart of the capital Doha. They include the Company House “bait Alshareekah,” the Radwani House, the Bin Jalmood House, and the Mohammed bin Jassim House.

This article focuses on the Company House Museum and the Radwani House Museum as examples that demonstrate Qatar's use of sustainable tourism. These historical houses present information that illustrates the life of the Qatari family in the twentieth century. This article analyses the importance of museums in bridging the gap between the past and present through their architectural heritage and the presentation of social and economic developments that occurred in Qatar in the twentieth century.

It highlights how Qatar is using sustainable tourism to preserve cultural heritage within the new development of a futuristic downtown Msheireb. It also highlights the role of Qatari museums in narrating these developments that led to the emergence of Qatar today. This article focuses on the efforts of the state to preserve its cultural heritage while modernizing and globalizing as a result of the oil industry boom.

Architectural Heritage as a Tool of Sustainable Tourism

Kabila, Jumaily, and Melnik define sustainable tourism as “a development model which administrates all of the resources for the economic, social and aesthetical needs of locals and visitors, and provides the same conditions for future generations. Most definitions of sustainable tourism emphasize the environmental, social and economic elements of tourism” (Hmood et al., 2018, p. 3). Architecture as a tangible heritage material plays a similar role to pieces that can be sent around the world in exhibitions. However, because architecture remains in its place, visitors can enjoy it as an outdoor gallery. To explain the importance of the contribution of architectural heritage in promoting sustainable tourism and creating income for a country, it is useful to examine the model of Vienna. In 1990, Vienna hosted approximately 3.15 million visitors, of whom ~1.1 million visited museums that reflected the city's architectural legacies. In addition, 487,000 tickets were sold to attend a theater dating back to 1870. In 2001, Vienna submitted a request to include its city center on the UNESCO World Heritage List (Republic of Austria, 2020).

The city of Vienna could attract tourists because it refused to convert the architectural heritage into static, non-interactive museums. Instead, the city managed and activated these historical sites by housing local businesses in these traditional/historical buildings and obliged the residents to establish entertainment activities and programmes that engaged the public (Republic of Austria, 2020).

Likewise, in Qatar, there is a growing interest in efforts to preserve the Qatari architectural heritage. The policy that the Qatari government is following in preserving the nation's architectural heritage has had a positive socio-culture impact. It offers its population the opportunity to learn about their ancestors' legacies, culture, heritage, and traditions. Meanwhile, it also creates spaces where tourists can experience and encounter the local cultural heritage. Qatar Museums (QM) protects heritage buildings and gives them new energy despite the transformation of the environment around them under the slogan “A new life for old Qatar.” QM is keen to develop sustainable tourism, which ensures that locals maintain their relationship with the past under the current transformations. Therefore, heritage experts try to develop solutions that enable them to integrate the old material heritage with the present, while making some sacrifices. Sustainable tourism is a very important element for a country like Qatar, as the state is considered a leading center in the region due to its strategic location and possession of the best aviation network in the world, Qatar Airways. The cancellation of entry permit visas for 80 countries, prepared Qatar to expect a large crowd of tourists, specifically in the year 2022 for the FIFA World Cup. The state hopes to preserve visitors' access even after the World Cup ends by establishing rules for sustainable tourism investment (Skytrax, 2020). To invest in tourism, it was necessary to highlight the Qatari identity and enable it as one of the factors of tourist attractions after the end of the World Cup. The government has focused on designing buildings that highlight the Qatari architectural style, such as the cultural village of Katara, Msheireb Museums, Souq Waqif, Souq Al-Wakra, Souq Ruwais, and finally the opening of the National Museum of Qatar in 2019. Therefore, the Qatari government aspires to promote its tangible and intangible cultural heritage assets.

QM succeeded in including the historical fort of Al Zubarah on the list of the UNESCO World Heritage Organization. The next step was a plan to revive this historical place by, for example, inaugurating a tourist programme “Window on the Past” at Al Zubarah fort. The programme adopted a mechanism of breaking the deadlock by reviving activities through conducting guided tours, presenting local foods, displaying handicraft workshops, riding camels, and other traditional activities that might interest tourists (Qatar, 2021). In addition, to enhance the engagement of the visitors within museums and cultural sites and to make these areas more active, some Qatari museums, such as the Museum of Islamic Art and the National Museum of Qatar, established parks and bazaars (Museum of Islamic Arts, 2021). Reviving these legacies is one of the pillars of national development. Qatar's National Vision 2030 emphasizes social development, which focuses on the preservation and protection of national cultural heritage and Islamic values and identity (Qatar Planning Statistics Authority, 2021). This emphasis reflects the strenuous efforts by QM to engage the community with museum practices.

Similarly, the Qatar Foundation (QF) seeks to activate and revive historical sites within post-modern Qatar through Msheireb Properties (MP). Msheireb Properties is a real estate development company and a subsidiary of QF. The company establishes ventures to support the goals of Qatar's National Vision 2030. Thus, MP focuses on the national development of innovative and sustainable projects that protect the Qatari cultural heritage. MP preserved models of traditional architecture through the establishment of Msheireb Museums. MP used a mechanism of architectural heritage documentation and sustainable tourism to enhance and enrich civic inheritance and heritage tourism without preventing modernization by renovating four historical buildings and reusing them as museums (Msheireb Properties, 2021a).

MP renovated the four houses in a sustainable way that aimed to create a dynamic relationship between tourism and cultural heritage. MP tried as much as possible to maintain the authenticity of the houses as a Qatari architectural inheritance. Keeping their authenticity as buildings with their collections, narratives, and roles was an essential component of their cultural importance. Heritage tourism enriches both sustainable tourism and cultural tourism, with an emphasis on maintaining natural surroundings and cultural heritage as much as possible in its original form. Heritage tourism rests on the importance of the cultural and natural environment. Such tourists prefer to visit heritage and historical sites, such as old souqs, forts, castles, museums, preserved parks, and nature reserves. They also prefer a minimum amount of environmental damage and impact (Hmood et al., 2018, p. 3). The renovation of those four historical houses created great opportunities for modern people to have a direct experience with the memory and intangible untold heritage and direct contact with the past. It allows the current generation to experience the places, learn about past activities and hear their ancestors' stories with all their ups and downs (Msheireb Properties, 2021a). This analysis of the preservation of the Qatari architectural heritage in Msheireb downtown focuses on two primary aspects. First, this preservation aimed to improve and develop the beauty and artistic features of the architectural heritage. Second, it aimed to introduce the futuristic city of Msheireb with its new architectural language in a manner that did not risk losing or harming the authentic local heritage. This approach leads to the questions, to what extent does the new Msheireb preserve the natural surroundings of the original old Msheireb? and does the current Msheireb reflect the old Msheireb downtown?

Msheireb the Old City

Traditionally, Msheireb means “a place to drink water,” as this town was built around a well that was generous enough to serve the whole area, which attracted the community that settled there (Msheireb Properties, 2021b). Historically, the town was a vibrant neighborhood that centered around Kahraba Street, which means “electricity,” an area that was the first to receive electricity in Doha. In the past, the shops were confined to the traditional souqs, or marketplaces, known to the people in Qatar, such as Souq Waqif, the internal souq and the Qaysariya souq. These souqs opened in the early morning and closed in the afternoon for a lunch break, then reopened in the afternoon until sunset only. At the beginning of the 1960s, with the acceleration of the development that began in Doha, a new market appeared with new stores that differed from the traditional souqs. These stores had glass facades, modern decorations and new imported goods displayed in elegant and attractive ways that Qataris had not previously known. In this area, modern restaurants opened and served foods that were unknown in Qatar, such as shawarma sandwiches, hummus, mutabal, mixed grills, and grilled chicken. Modern groceries and supermarkets also opened in the area. In addition, the shops in this street were open from morning until midnight. Al-Kahraba Street, or “electricity street” at that time was not only a commercial street for buying and selling but also a cultural and tourist landmark that became famous among all the countries of the region for its modernity and vitality.

Tourists from outside Qatar and locals alike toured this street, enjoying its atmosphere by walking, buying imported goods, and enjoying new options of food and drink. The movement in the street did not stop until dawn, as this street was the only outlet for people, young and old, rich and poor (Al-Malki, 2013). Annually, tens of thousands of locals and visitors go to Msheireb Downtown to see and interact with the Qatari architectural aesthetic that integrates the country's sustainable and functional practices commonly known as the “Seven Steps” to protect and nurture Qatar's built and cultural heritage. A key attraction for the visitors is the close-knot pedestrian streets that reflect and foster the strong social ties held by the Qatari people.

The rapid growth of Qatar has produced some challenges, such as transforming the original identities of the state's cities and their ways of living. These transformations created a huge gap between traditional Qatari architecture and lifestyles and those in current Doha with its post-modern architecture and lifestyles. Msheireb became the site of an ambitious plan to regenerate the town (Monocle, 2020). The foundation of the project began with the patronage of Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser Al-Misned, who established Msheireb Properties with an obligation to address the gap between the past and the present and revive a distinctive form of Qatari urban development. It is a redevelopment initiative that bridged the gap between Qatar's heritage and the futuristic city of Doha (Monocle, 2020). Msheireb preserved its atmosphere and role as a tourist destination, where people can enjoy walking and having food and drinks. However, the architectural heritage was completely lost and replaced with new buildings and a new urban layout. Consequently, the preservation of four historical houses and their function as museums came to fill the gap of representing a part of the lifestyle that was once there at the beginning of Qatar's development.

Msheireb Museums: The Past Overlaps With the Present

Museums are of great importance in narrating stories of the social and economic life of any society, as they preserve the material evidence of those societies. Museums are among the most important means of expressing the heritage and history of civilizations and societies, as they document the lives and activities of people and the places in which they lived. They also vary in nature and specialties. Some museums specialize in art, such as the Islamic Museum in Qatar, which includes many monuments of Islamic arts, and other museums specialized in heritage, such as Msheireb Museums, which convey parts of Qatar's past.

Like museums, architectural features also highlight the identity of the state by illustrating multiple factors that relate to the development of the state of Qatar. Architecture can provide a set of facts that contribute to highlighting the state's past and knowledge of its sovereign, economic and social politics. It is from the architectural heritage and legacies of the former inhabitants that we can better understand how this society developed.

QF aims to highlight the spirit of the Qatari identity, presented in the heart of the post-modern futuristic city of Msheireb, with four traditional houses. The location of the Msheireb museums serves as a tool to document the history and architectural heritage while also documenting Qatar's economic development. Each renovated house emphasizes an original architectural feature. The first house, the Bin Jelmood House, was originally a slave house. The house acknowledges the economic, social, and cultural contributions of previously enslaved people to the improvement of human civilizations (Msheireb Museums, 2021a). The second house, the Radwani House, represents an integrated residence for a Qatari house. The house was built in the 1920s on a location separating the oldest districts of Doha, Al Jasra and Msheireb. The house documents the lifestyle of the Qatari family in the early twentieth century. Visiting the museum allows people to learn about everything that characterizes that period (Msheireb Museums, 2021e). The third house, the Company House, was once used as the headquarters for the first oil company in Qatar, the British Oil Company. The museum was developed to narrate the story of the Qatari pioneers in the petroleum industry. They assisted the transformation of Qatar into a modern society, by demonstrating remarkable dedication. The museum exhibit tells their stories in their own simple words and narrations. They describe what they endured and how they labored to provide a better future for the coming generations and the country (Msheireb Museums, 2021b). The fourth house, the House of Mohammed Bin Jassim, focuses on the son of the founder of modern Qatar. He devoted part of his house to serve as a medical facility, leading the state to design the nation's first hospital. The house reveals “Msheireb's traditional values as the foundations for the future development of Doha and introduces the transformation of Msheireb over time through recalling memories of its past, showcasing its present, and engaging visitors in the plans for the future” (Msheireb Museums, 2021d).

All of these buildings, with their various specializations and close proximity, demonstrate the center of gravity of that vital region with its ancient and modern facilities (Msheireb Museums, 2021c). Together, they allow the visitor to become acquainted with the patterns of Qatari architecture in the past. To make the area lively for the locals, the post-modern futuristic city of Msheireb was built, which takes inspiration from the traditional buildings of the four Msheireb museums that are considered the cultural destination of the post-modern city (Qatar Museums, 2020). The challenge that MP undertook with this project was to invent an approach that balanced financial benefits with the protection of local cultural identity and nature. The preservation and presentation of cultural heritage within sustainable tourism have positive social and economic impacts. They strengthen local identity and allow local people to move forward. They also help to introduce tourism positively and raise awareness of the importance of authenticity and values (Hmood et al., 2018, p. 4). This challenge raises the question of how far the reinvention of Msheireb preserves and reflects Qatari social life and heritage. Reaching an answer requires reflecting on the social and economic lives of the Qataris before and after the discovery of oil.

Economic and Social Development

Before the discovery of oil, Qatari society was modest and primarily a tribal society. In addition to the tribes in the area, there were also Qatari families, who cooperated with the tribes, making the primary feature of Qatari society one of collaboration. In its economic development, Qatari society went through different stages, which affected its social life. The first stage was the era of diving, when pearling was the main economic activity for the Qatari. That period corresponded with the beginning of the emergence of Qatari society, which at the beginning of the twentieth century reached about 32,000 people, of whom 4,000 were Bedouins, and the remainder were settled residents (Al-Zaidi, 2010).

The second stage was the transition from diving to the oil era, beginning in the mid-1930s. The signing of an oil concession agreement with the State of Qatar in May 1935 led to the deterioration of the diving industry. The role of tribalism declined under the new oil con concession agreement and the new professions that accompanied it.

Qatar is part of the Arabian Gulf society, culture and economy. Thus, through different eras and under different circumstances, residents of Qatar have sought a safe and stable life, focusing on earning a livelihood from the sea or on land from grazing or the life of the desert. After the discovery of oil, the course of social life changed, and Qatari society became divided into classes after it had been divided into multiple tribes.

The Role of Persian Migration in the Society

With the discovery of oil in the Arabian Gulf countries, Persian families began to immigrate to the region. At that time the region provided golden opportunities for Persian merchant families and Persian individuals seeking new economic opportunities and work. Like other Arabian Gulf countries, Qatar received an influx of Persian migrants, who came to Qatar for economic opportunities and material gain. As they integrated into the Qatari society, they identified with the locals but maintained their original language and an accent that differs from that of the prominent families in Doha (Al-Mokh, 2019).

The regularity of oil wealth and the accompanying transformation process led to an increase in the state's economic activity. One of the Persian families that migrated to Qatar at the beginning of the twentieth century was the Al-Radwani family. They came to play a significant role in the social and economic life of Qatar and represent an example of a Persian family, who chose to settle in Doha during the economic and social development of the country.

Radwani House Museum: Social and Economic Transformation

The Radwani House in the heart of the Msheireb downtown area represents one of its historical landmarks, which summarizes Qatari folklife and its transformations since the 1920s. The traditional architecture used climate-friendly materials and took into account the local culture. It had specific restrictions that met the needs of living and did not contradict Qatari customs and traditions. The construction of the Al-Radwani House dates back to the 1920s and is located on a site that separates the two oldest neighborhoods in Doha, those of Al Jasra and Msheireb. Ali Akbar Radwani bought the house on December 5, 1936, and it remained the property of his family for more than 70 years (Hudayb, 2020).

In the mid-1930s, this building underwent modifications in its design, preserving its old walls, while demolishing other parts and reusing them in new construction, a practice common at that time. The house underwent expansions and redesigns several times, and today it is one of the oldest historic houses in Doha (Hudayb, 2020).

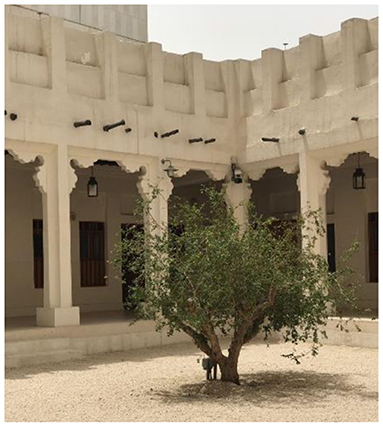

A tour of the Radwani House Museum gives an idea of how it developed over time, as well as how the traditional pattern of family life in Qatar developed. The house had an open courtyard called the “housh,” an important space for family gatherings.

The house displays the life of the Qatari family in the past through its Indian-style bedroom, its modest furniture, the kitchen that uses old clay pots, and household tools that were used in the production of bread and food preparation. In addition to the living room with its simple furniture, a sewing machine embodies the image of the Qatari woman who used to sew clothes for her family members (Hudayb, 2020). Although the Al-Radwani House has undergone many expansions and reconstruction processes throughout its history, it has preserved the traditional pattern of Qatari houses based on the presence of a central courtyard in the middle of the house. In accordance with the prevailing traditions, the external facade of the house is windowless for the privacy of the residents, except for the “majlis” in which the guests were received. To preserve the privacy of the courtyard area, access to the majlis is through a corridor that begins at the main door of the house and proceeds at a 90-degree angle to makes it difficult for the guests to see the courtyard and those in it (Hudayb, 2020).

After the Radwani family moved out in 1971, the house sat deserted. In 2007, restoration work began based on archival research, interviews with people who knew the history of the house and an engineering survey to determine if it could be restored safely. The restoration process used traditional building materials and methods as much as possible, but with the adoption of modern engineering methods when necessary. For example, the stone columns and wooden lintels in the “Liwan” were replaced by concrete columns and steel beams to ensure the integrity of the building (Figure 1) (Al-sheeb, 2020).5

Figure 1. A traditional courtyard was a primary feature in Qatari houses that surrounded the open sitting area Liwan.

Archaeological excavations at the Radwani House were carried out in four stages:

1. Formulate objectives by studying the historical emergence of the city of Doha and how it transformed into a modern city.

2. Study maps and oral documentation of Msheireb City to understand the history of the region.

3. Begin excavations at several sites for their historical value.

4. Evaluate and analyse the data and information from the previous stages (Al-sheeb, 2020).6

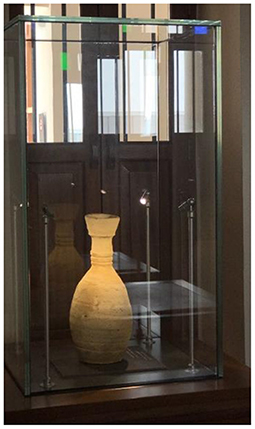

Excavations revealed ancient lighting equipment and the remains of a light bulb and located a “Qudo”7 (Figure 2) used for smoking tobacco with a stove to light coal. The excavations also found many children's toys, small bottles for perfumes, glass balls, a censer for oud and incense made of limestone, indicating that life in the middle of the twentieth century had begun to gain more amenities and entertainment options. Another traditional feature that the house preserved was the idea of distributing the rooms around the perimeter of the yard.

Figure 2. Qudo is an Iranian traditional smoking tool that was brought to Qatar by Iranian immigrants and integrated into Qatari heritage.

The rooms in the house museum represent chronologically how the lifestyle changed according to the circumstances. For example, the first room reflects life in Qatar before the arrival of electricity. The second room shows the nature of daily life for the generation that immediately followed the arrival of electricity (Al-sheeb, 2020). On the right side, there are indications of a bath and a well of water for daily use, as people used to bring pure water from other areas or it was sold through “al-Kandari.” On the other side are cavities that reflect the foundations of the original building of the Radwani House (Al-sheeb, 2020).8

Heritage tourism at the Radwani House Museum embraces the preservation of identity, nostalgia needs, cultural heritage tourism, and conserving the resource from deterioration. Heritage tourism depends mostly on the cultural atmosphere and focuses on the heritage and historical values of the house (Hmood, 2007). Heritage tourism makes visits to museums a pleasurable practice. This kind of tourism is concerned with the preservation and protection of the national identity and heritage and can reflect a green tourism approach. Within the museum exhibitions and collections, visitors travel in time and history. During their leisurely walk through the futuristic city of Msheireb, visitors can enter the house to find themselves suddenly in a very traditional place in old Msheireb, where they can experience Qatari traditional artifacts, activities and places that genuinely represent, and narrate the story of the people (Hmood et al., 2018). The old historical house is not separated from the post-modern architecture by a space. Rather, the historical house preserved its architectural style while the post-modern surrounding spaces were developed around it. Urban protection in historical downtown Msheireb is accomplished by applying urban renewal strategies, which sustain the urban material and construction of the inherited houses and city while meeting contemporary demands (Cohen, 2011). Over the years, over 80,000 visitors have entered the Radwani House Museum to celebrate and understand the Qatari heritage and culture.

The Company House Museum: Qatar's Development

The Company House is the most important landmark in the Msheireb neighborhood. It was built by Hussain Al-Naama, the director of the Doha Port, as a home for his family. In 1935, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company rented the house was rented to serve as the headquarters of the first oil extraction company in Qatar after it was awarded a contract to explore and extract oil from the Qatari lands in the 1930s. During that time, Qatari laborers gathered outside the company's house to board trucks, which took them on arduous trips to the oil fields in the desert in Dhukhan city, ~85 km outside of Doha.9

Before the discovery of oil, life in Qatar was different, as the professions were divided into two parts with a section for women. One of them was the profession of traditional medicine. Before the construction of modern and professional hospitals in Qatar, people relied on traditional medicine for treatment. Women treated women, helping them to give birth and treating girls and children. They treated illnesses such as sprain, bile, and measles by using medicinal herbs or cauterization with fire. The profession of sewing was called “Darze or Tailor,” and it caused a fundamental change in the life and behavior of women in Qatar. It includes sewing in all its forms (Al-Malki, 2008). The profession of a street vendor, which was not limited to men, involved knocking on doors to sell what they had, including eyeliner, henna, sewing tools, etc. It is worth noting that many who engaged in this profession were immigrant women from Iran (Al-Malki, 2008).

Professions for men also varied and included practitioners of traditional medicine, who used herbs to treat people, especially men, before the hospitals were established; waterers, who watered the neighborhood and brought water from wells; and bakers, who prepared bread. There were marine professions, including fishing, shipbuilding, diving, and pearling (Al-Malki, 2008). Before the discovery of oil, pearling was the primary trading activity upon which Qatar's economy depended. Fishing pearls was a collective effort among the ship's crew, which might number between 10 and 40 men and occasionally more than 70, depending on the size of the ship (Ahmed, 2014).

Since it is formation, Qatar has experienced and passed through different difficult eras. One of these difficulties was the year of drowning in 1925, which witnessed a hurricane that led to great losses in buildings, mud huts and people's lives. A decade later came renewed hope when geologist G. M. Lees revealed the possibility of large reserves of oil in Qatar. A stage of “Qataris' scepticism” about oil followed, during which one Qatari said, “The most he expected from the oil revenues was to build a school or a better standard of living, but it never crossed my mind, and I never expected that the changes would be so important and dramatic.”10 Then came the promising news and celebrations after a brief appearance of oil in one of the test wells located near the city of Zekreet, where drilling and exploration work continued. Unfortunately, a period of economic stagnation and the consequences of the Second World War followed that hope. However, when the war ended, oil exploration operations began again. In 1949, the first shipment of oil was exported from Qatar, which was followed by a steady flow of oil revenues. Consequently, life began to improve gradually, as many old people and young men scrambled to work in the oil industry (Al-Zaidi, 2010). Oil workers moved to work in Dukhan and Mesaieed, the main oil cities in Qatar at that time. Workers came to Doha only once a week, and the day of their return was a memorable day for their families (Al-Othman, 1984).

The Exhibitions of the Company House Museum

The museum narrative showcases the experiences of the Qatari laborers at the beginning of the oil discovery era. It highlights a story of the first Qatari laborers who joined the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, whom curators called alsawaeid alsumer, “the bare hands.” They borrowed this name and narrative from a book by the Qatari writer Nasser Al-Othman, who was the first to document such experiences in his book With Their Bare Hands.

The museum contains seven different galleries. The first gallery is the entrance of the company which displays a saying by His Highness the Father Emir Sheik Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani: “Our human potential represents real wealth, not oil.”11 These words express the value that the state attaches to the Qatari person, as it considers him to be the real and lasting wealth for the stability and progress of the state, not oil.

Following that introduction, the names of the first Qatari laborers were displayed in the gallery. The second gallery is the theater area, where a documentary movie chronicles the arduous journey of the pioneers of the oil industry from Doha to Dukhan and Mesaieed in the South and back on the back of an open truck (Figure 3). One of the Qatari workers recounts his arduous journey while living in Al-Khor a Northern town, saying: “in our off time, we used to ride cars that heading to Doha. The car dropped us off in Umm Salal town around 29.89 km away from Al-Khor; from there, we had to walk our way back home.”12

Figure 3. The truck that was used to transfer Qatari oil laborers from Doha to Dukhan and Mesaieed in the South and back. Displayed in the museum courtyard. Taken by the author in May 2018.

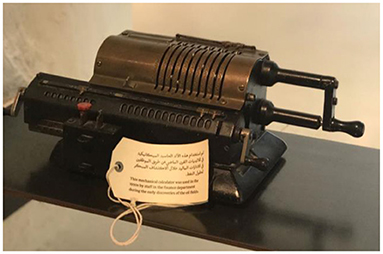

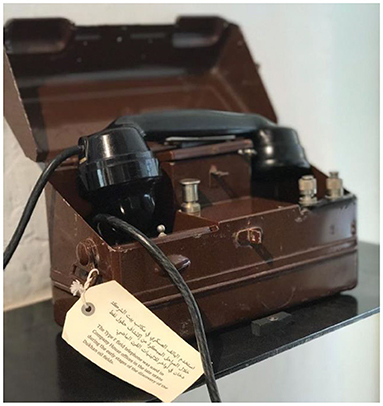

The third gallery explains the discovery of oil chronologically. The exhibition begins in 1920 and moves through the years 1930, 1940, 1950, and 1960, highlighting the stages that the Qatari people went through in the search for oil. One example is the despair stage that Qataris experienced after the depression of the pearl trade when the fishermen sold their boats and their timber. Many of them also went to break stones and sell them to Sheik Muhammad bin Jassim.13 The fourth gallery consists of an open storage area, where curators arranged different exotic products that were introduced to Qatar during the 1930s and 1940s with the arrival of the oil company. These products included a military telephone (Figure 4), a calculator (Figure 5),14 the first electric generator in Qatar, and so on.15

Figure 4. A military phone that was used at the Company House by the British workers at the oil company.

The fifth and sixth galleries are called the worker‘s life. In these exhibitions, large screens display the daily routines and activities of the laborers in the company. Visitors learn about the work that the Qatari pioneers practiced when they joined the oil company. Some worked as excavators, others as laborers, and still others as drivers. There are interactive screens that provide an opportunity to watch black and white images that are part of the tales of misery and fatigue that Qataris experienced in the past.16

The seventh gallery is dedicated to the stories of eight “bare hands” or “alsawaeid alsumer” (Figure 6). Their photos, quotations from their interviews and some of their personal belongings show the lives of those pioneers and their life stories. Among the personal items are identity cards, coins, prayer beads, books, a wristwatch, packages of dried foods, a container for preserving food (Figure 7), and other personal tools.

Figure 7. A lunch box of four containers, used by Qatari laborers to preserve their food at their workplace.

The display of the social and economic changes these workers faced and the cultural heritage they left behind has been accomplished by restoring the Company House with its unnarrated story. It is another source for sustainable heritage tourism and the preservation of the Qatari identity. Qatari identity is highlighted in the museum display through the lives of the eight bare hands laborers. Their stories enriched the museum exhibition and gave it a unique local flavor. It maintains a clever balance between post-modernism needs and the existing history and heritage. Such an approach protects the original setting for the local community during the development of the new Msheireb. Thus, the futuristic city and the heritage site of Msheireb are connected for modern purposes. The traditional houses and the story of the Qatari society are utilized in the museums' displays to offer locals and tourists alike a first-class tourism experience. The development maintains the historical function of downtown Msherieb, where people used to walk, eat, drink, gather, and spend their nights along active streets. The town's new structure and street network recreate a similar concept while preserving the four unique historical houses and limiting vehicle traffic in the area. These steps preserve not only the physical appearance of the area but also the town's historical function. Urban development and heritage tourism encourage linking the old with modern planning projects in a way that develops a combined architectural language. Both the old and new features together make up the new futuristic Msheireb, which is a unique mix that distinguishes this Arabian Gulf city. Placing these museums in this vital location creates a dynamic relationship among Qatar's past, present and future, as well as providing an integrated picture for tourists about Qatari culture and heritage. Such a heritage tourism site is sustainable for current and upcoming generations. The Msheireb Museums maintain the authenticity of the places, collections, activities, functions, and heritage sites. They offer tourists an exploration of heritage through physical materials, tangible and intangible traditions, and collected memories. Such cultural tourism experiences increase the appreciation for and understanding of that cultural heritage.

Conclusion

Through museum displays that show social and economic life in Qatar before and after the discovery of oil, Msheireb Museums has attracted the interest of citizens, residents and tourists who are eager to discover more about the culture, heritage, and history of Qatar. These four museums are located in the area renovated by Msheireb Properties as the newest and most forward-looking neighborhood in Doha, where visitors discover an unparalleled dialogue between the nobility of the past and the aspirations of tomorrow (Al-Jazeera, 2019).

“The Msheireb Downtown Doha project is a real estate dream embodied in reality, as the old district of Msheireb has been transformed into an integrated residential and service area in line with the ambition of the Qatar National Vision 2030.” This project hopes “to achieve the conditions of sustainable development, provide current and future generations with high standards of living, and provide a role model” for the development of central cities around the world (Al-Jazeera, 2019).

Although the project is still in its final stages of construction, Msheireb Properties, the owner of the project, planned “to quickly open its four museums before its completion, so that during the past 3 years it would become a typical tourist, cultural, and educational destination in the region” (Al-Jazeera, 2019).

It was important to address the social and economic life and transformations in Qatar at a very important moment in the contemporary history of the country. Transforming the Radwani House, the Company House and others into museums in the city of Doha was necessary to commemorate events, time periods and various social and economic phenomena. Such images appeared in every part of the museum; in the majlis, in the living room, in the kitchen, etc., and all the belongings illustrate the adherence of Qataris to their national identity and heritage. These museums represent the vision and intention of Msheireb Properties in preserving the national heritage.

In totality, the analysis of the two museums and their sustainable tourism activities proves local authorities' agency to promote sustainable tourism development within the cosmopolitan development environment. An increase in traffic in Qatar due to tourism-related activities has strategically placed the nation on the world map, creating more opportunities and recognition worldwide. The tourism sector has created avenues through which innovations such as green building codes, scientific evaluation of coastal development, reliance on solar power into buildings, and technologies to manage scarce water resources have been adopted. Equally, the cosmopolitan status of their developments has created opportunities for cultural diversity and pathways for creating economic opportunities from the natural heritage that Qatar possesses. Therefore, it is no doubt that the maintenance and rehabilitation of the three museums represent the expression and determination of Qatar's strategic vision concerning sustainable tourism.

The article's exploration has shown how Qatar has designed and developed a sustainable tourism and development strategy focused on the Qatari culture, traditions, heritage, and identity. The connection between the Qatar National Vision 2030, the Qatar National Tourism Sector Strategy 2030, and the Sustainable Development Goals have created credibility and success factors. The focus on sustainability has made it possible for Qatar infrastructure and property lifecycle to focus on sustainable development, Qatari heritage preservation, identity safeguard and cultural diversity.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Qatar National Library for their support.

Footnotes

1. ^United Nations World Tourism Organization.

2. ^United Nations World Tourism Organization.

3. ^United Nations World Tourism Organization.

4. ^The Qatar Tourism Authority.

5. ^Liwan is a spacious part of the house surrounded by three walls, a roof carried on columns decorated with drawings and the fourth side open to the outside.

6. ^Liwan is a spacious part of the house surrounded by three walls, a roof carried on columns decorated with drawings and the fourth side open to the outside.

7. ^The Qudo is a long-necked clay jar used for smoking. It was brought from the Persian area to the Gulf region, where it spread quickly and is still used for smoking and has become part of the local heritage.

8. ^An Al-Kandari was someone who transported and sold water by visiting individual homes before oil was discovered. As a profession, it has long been forgotten.

9. ^Curators of the Company House Museum, interview by the author, 13 March 2020.

10. ^Exhibit Label at The Company House Museum, viewed by the author on 4 July 2021.

11. ^Exhibit Label at the Company House Museum, viewed by the author on 10 July 2021.

12. ^Exhibit Label at the Company House Museum, viewed by the author in July 2021.

13. ^Al-Othman, With Their Bare Hands.

14. ^Display at the Company House Museum, viewed by the author in July 2021.

15. ^Curators of the Company House Museum, interview by the author, 13 March 2020.

16. ^Display at the Company House Museum, viewed by the author in July 2021.

References

Ahmed, I. F. (2014). Qatar and its Maritime Heritage, 1st Edn. Doha: Katara Cultural Village Foundation.

Al-Jazeera (2019). Msheireb Museums: Where Past and Future Mingle in the Heart of Doha. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.net/news/cultureandart/2019/3/9/ (accessed July 6, 2021).

Al-Malki, K. A. M. (2008). Professions, Crafts and Popular Industries in Qatar, 1st Edn. Doha: The National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage.

Al-Mokh, Z. (2019). Qatar: A Study in Foreign Policy, 1st Edn. Doha: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies.

Al-Othman, N. (1984). With Their Bare Hands: The Story of the Oil Industry in Qatar. London: Addison-Wesley Longman Ltd.

Al-Saadani, S. (2017). Museums, The Memory of Living Peoples and the Immortal Heritage of Humanity. Egypt State Information Service. Available online at: http://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/139406/Museums..-the-living-people-memory-and-humanity-immortal-legacy?lang=ar (accessed November 11, 2021).

Al-Zaidi, M. (2010). The Contemporary History of Qatar 1913-2008, 1st Edn. Amman: Dar Al-Minahij Publishing, 10.

Cohen, N. (2011). Urban Planning Conservation and Preservation. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill: New York, 17.

Hmood, K. (2007). “Successful experiments in the preservation of heritage,” in Proceedings of the Scientific Symposium: Towards a Comprehensive Strategy for the Development and Maintenance of Historical Cities (Ghadames), 89.

Hmood, K., Jumaily, H., and Melnik, V. (2018). Urban architectural heritage and sustainable tourism', WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 227, 209–220. doi: 10.2495/ST180201

Hudayb, M. (2020). “The Radwani House… traditional architecture and social transformations,” in History of Martyrdom, oral history, interviewed in December 2019. Available online at: https://www.alaraby.co.uk/%22

Lau, J. (2010). History of dress, Chinese style. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/31/fashion/31iht-FDRESS.html (accessed December 30, 2019).

Monocle (2020). Model urban living. Monocle. Available online at: https://monocle.com/magazine/msheireb-properties/2021/2-model-urban-living/ (accessed July 15, 2021).

Msheireb Museums (2021a). Bin Jelmood House. Available online at: https://msheirebmuseums.com/en/about/bin-jelmood-house/ (accessed September 25, 2021).

Msheireb Museums (2021b). Company House. Available online at: https://msheirebmuseums.com/en/about/company-house/ (accessed September 25, 2021).

Msheireb Museums (2021c). Discover Untold Stories of Qatar. Available online at: https://www.msheirebmuseums.com/ar/ (accessed March 18, 2021).

Msheireb Museums (2021d). Mohammed bin Jassim House. Available online at: https://msheirebmuseums.com/en/about/mohammed-bin-jassim-house/ (accessed September 25, 2021).

Msheireb Museums (2021e). Radwani House. Available online at: https://msheirebmuseums.com/ar/about/radwani-house/ (accessed September 25, 2021).

Msheireb Properties (2021a). About Us. Available online at: https://www.msheireb.com/#welcome (accessed July 31, 2021).

Msheireb Properties (2021b). History Downtown Msheireb. Available online at: https://www.msheireb.com/msheireb-downtown-doha/about-msheireb-downtown-doha/history/ (accessed July 15, 2021).

Museum of Islamic Arts (2021). A Modern Version of the Old Souq Tradition. Available online at: https://www.mia.org.qa/en/mia-park/park-bazaar (accessed July 31, 2021).

Pedersen, A. (2004). Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites: A Practical Manual for World Heritage Site Managers. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 24.

Qatar (2019). Qatar National Vision 2030. Government Communications Office. Available online at: https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/about-qatar/national-vision2030/ (accessed Febraury 25, 2021).

Qatar (2021). Heritage Sites. Available online at: https://www.visitqatar.qa/en/things-to-do/art-culture/heritage-sites (accessed July 01, 2021).

Qatar Museums (2017). Treasures from China Exhibition, Museum of Islamic Art, 7 September 2016 until 7 January 2017.- The Exhibition. Available online at: https://www.qm.org.qa/en/treasures-of-china (accessed March 18, 2021).

Qatar Museums (2020). The Urban Fabric of Old Doha. Available online at: https://www.qm.org.qa/en/cultural-heritage-management-urban-fabric-projects (accessed February 10, 2020).

Qatar Planning Statistics Authority (2021). Qatar National Vision 2030'. Available online at: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/qnv1/pages/default.aspx (accessed July 31, 2021).

Republic of Austria (2020). ‘The Historic Centre of Vienna: Nomination for Inscription on the World Heritage List. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Available online at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1033/documents/ (accessed December 30, 2019).

Skytrax (2020). World Airport Awards 2019. Available online at: https://www.worldairportawards.com/ (accessed January 21, 2020).

Trahant, M. (2018). Native American Imagery is all around us, while the people are often forgotten. National Geographic. Available online at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2018/10/indigenous-peoples-day-cultural-appropriation/ (accessed March 27, 2020).

Vehbi, B. O. (2012). “A model for assessing the level of tourism impacts and sustainability of coastal cities,” in Strategies for Tourism Industry – Micro and Macro Perspectives, eds M. Kasimoglu and H. Aydin (London: InTech Europe), 104.

Waheeb, M., and Zuhair, Z. (2018). Reviving the Past into the Future, Amman Nymphaeum Background and Architecture. The Amman Nymphaeum; Department of Antiquities. Available online at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heritage_tourismhttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heritage_tourism (accessed March 28, 2018).

Keywords: Msheireb Museums, Msherieb downtown, sustainable tourism, Qatar National Vision 2030, cultural heritage, post-modernism, sustainable development (in Qatar)

Citation: Al-Hammadi MI (2022) Toward Sustainable Tourism in Qatar: Msheireb Downtown Doha as a Case Study. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:799208. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.799208

Received: 21 October 2021; Accepted: 31 December 2021;

Published: 03 February 2022.

Edited by:

Usamah F. Alfarhan, Sultan Qaboos University, OmanReviewed by:

Lorenzo De Vidovich, University of Trieste, ItalyAsli Ceylan Oner, İzmir University of Economics, Turkey

Copyright © 2022 Al-Hammadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mariam I. Al-Hammadi, bS5hbGhhbWFkaUBxdS5lZHUucWE=

Mariam I. Al-Hammadi

Mariam I. Al-Hammadi