- 1Northern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Evanston, IL, United States

- 2Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 3Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

As the world contends with the far-ranging impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing environmental crises have, to some extent, been neglected during the pandemic. One reason behind this shift in priorities is the scarcity mindset triggered by the pandemic. Scarcity is the feeling of having less than what is necessary, and it causes people to prioritize immediate short-term needs over long-term ones. Scarcity experienced in the pandemic can reduce the willingness to engage in pro-environmental behavior, leading to environmental degradation that increases the chance of future pandemics. To protect pro-environmental behavior, we argue that it should not be viewed as value-laden and effortful, but rather reconceptualized as actions that address a multitude of human needs including pragmatic actions that conserve resources especially during scarcity. To bolster environmental protection, systematic changes are needed to make pro-environmental behavior better integrated into people's lives, communities, and cities, such that it is more accessible, less costly, and more resilient to future disturbances.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended lives and laid bare numerous weak spots of modern society. Healthcare systems have failed, supply chains have broken, and poverty and food insecurity are on the rise (Pereira and Oliveira, 2020; Solomon et al., 2020). As such, many forms of scarcity have been exacerbated by the pandemic, leaving millions of people with insufficient resources to maintain a certain standard of living. The most poignant type of scarcity during this pandemic is the scarcity of physical resources, such as food and medical equipment, as well as financial scarcity due to a weakened economy. However, the pandemic has also resulted in a scarcity of cognitive resources, causing a notable neglect of environmental issues such as climate change and plastic pollution, which are relegated to a lower level of concern. In other words, the pandemic has imposed a form of cognitive scarcity on environmental issues that also deserve attention. This change of priorities is illustrated in the precipitous drop of climate-related media coverage at the onset of the pandemic in some countries (Medium., 2021), which had been increasing steadily in the preceding years (Barouki et al., 2021).

Although this attentional shift might seem intuitive given all the pandemic-induced socio-economic disruptions that have taken place, it may be ultimately counterproductive because environmental degradation could lead to future pandemics. Scientists have for years warned of the connection between disease outbreaks and anthropogenic environmental change such as climate change and habitat destruction (Weiss and McMichael, 2004; Barouki et al., 2021), and how ignoring this connection could set the stage for future pandemics and natural disturbances more generally.

The COVID-19 Pandemic's Impact on the Environment

A recent SDGs report shows that the world is off track to meet the goals toward environmental sustainability (United Nations, 2020). Most countries are not meeting their commitments to limit greenhouse gas emissions, to improve urban environments by reducing the number of people living in slums, increasing access to public transport, and reducing air pollution. Efforts toward sustainable and inclusive economic growth, energy provision, and infrastructure development have all been falling short during the COVID-19 pandemic (The Lancet Public Health, 2020).

Perhaps the most significant adverse environmental impact of the pandemic has been the astronomical increases in plastic waste generation (Silva et al., 2021), the effects of which are being observed already on coastlines (Chowdhury et al., 2021), wildlife (Hiemstra et al., 2021), and cities which are reporting increases in littering (Ammendolia et al., 2021; Time, 2021). Years of declines in plastic waste have been reversed during the pandemic due to increases in disposable personal protective equipment (Adyel, 2020; Benson et al., 2021). While it's necessary to use single-use plastics in some healthcare settings, a secondary impact of the pandemic has been an overall increase in plastic waste as restaurants have shifted to a takeout model or grocery stores ban the use of reusable bags (Vanapalli et al., 2021). To clarify, the point made here is not that the policy itself is problematic—communities should act in accordance with local health guidelines—rather, the issue is that our reliance on single-use plastics is a convenient fallback during the pandemic. On the other side of the plastic waste cycle, cities have cut recycling programs as budgets tighten due to pandemic responses (Waste Dive., 2019; PBS, 2021). This is further compounded by an increase in oil companies' investment in the production of virgin plastics, citing the reduced demand for recycled plastic products (Reuters, 2020).

The Scarcity Mindset Under the Pandemic

In addition to the health impact, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented a sudden perturbation in many aspects of people's lives. According to a recent report from the World Bank, the COVID-19 pandemic is estimated to push as many as 150 million additional people into extreme poverty, defined as living on less than US$1.90 a day, by 2021 (The World Bank, 2020). It is estimated that during the first three quarters of 2020, nearly 500 million full-time jobs were lost worldwide due to workplace closures (International Labour Organization, 2020). In North America, 46% of Canadians reported being stressed financially (Gadermann et al., 2021), 52% of US adults say they have experienced negative financial impacts due to the pandemic (American Psychological Association, 2020), and 51% of US adults reported that the pandemic has made it harder for them to achieve their financial goals (Pew Research Center, 2021). Local COVID cases and deaths present an immediate health threat and lockdowns and travel restrictions present a threat to social relationships. The financial, health, and social threats may trigger an enormous sense of worry and concern, drawing attentional resources to the threats and creating what has been termed a scarcity mindset.

The Scarcity Mindset

Mullainathan and Shafir (2013) define scarcity as “having less than you feel you need” (p. 4). This could apply to many domains, though most commonly to financial scarcity. The idea of a scarcity mindset builds on research within cognitive psychology and behavioral economics, stating that scarcity acts like a cognitive load which affects many fundamental cognitive functions like how people think, reason, and decide. For instance, financial scarcity has been shown to impair cognitive performance on tasks measuring fluid intelligence and executive function (Mani et al., 2013). Financial scarcity also highlights an economic dimension to everyday experiences where thoughts about costs and money are top of mind (Shah et al., 2018) and price information captures visual attention away from opportunities to save (Zhao and Tomm, 2017). Other studies have suggested that perceiving scarcity might impact cognitive self-control where immediate needs become more salient than future ones (Cannon et al., 2019). This may result in several non-normative decisions from an economic or longer-term perspective (Zhao and Tomm, 2018), such as lower saving rates and greater debt accumulation, which may be why much of the work on the scarcity mindset has focused on participants from a lower socioeconomic background. Yet, this increased focus on short-term incentives has also led to better performance on other tasks. For example, people under financial scarcity exhibit greater price sensitivity, and are less likely to be fixated on proportional gains at the expense of absolute quantity (Shah et al., 2015; Frankenhuis and Nettle, 2020). That is, people under scarcity are equally likely to value saving 50% of $100 and saving 5% of $1000.

Despite what the literature may suggest, it is worth pointing out that scarcity is not synonymous with poverty. Rather, as a recent review by de Bruijn and Antonides (2021) notes, “not all low-income individuals experience feelings of having less than they need” and conversely, being objectively well-off is not an inoculation against perceiving the burden of scarcity. In other words, there is a conceptual divergence between being poor and feeling poor—a distinction not always clear in the literature. For most people, regardless of their level of income, scarcity may be a constant hum in the background guiding and constraining their thinking throughout much of their lives.

The Pandemic Increased Scarcity

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned that background hum into a roar for many of us. As a direct consequence of the pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns, scarcity of resources and time has become a hallmark of our lives (Hamilton, 2021). Lockdowns, designed to slow virus transmission, were intended to and were effective at lowering the burden on medical facilities. This led to a scarcity mindset in at least three ways: (1) by highlighting the limited healthcare resources available (i.e., the number of hospital beds available), (2) by inflicting an actual economic cost on people, which reverberated through the society as restaurants, bars, and other non-essential services closed down for weeks or even months in some cities, and 3) by inflicting an emotional cost on people via border closures that prevented families and friends from physical reunions (Solomon et al., 2020; Civai et al., 2021; Echegaray, 2021).

These factors disproportionately impacted lower-income countries, which often were unable or unwilling to monetarily compensate for the economic loss of the lockdowns, and communities of color who have less reliable access to healthcare and may be more affected by the closures of physical business due to systemic inequities in digital access (Mahmood et al., 2020). Further, labor shortages and outbreaks at factories and processing plants had wide-ranging impacts on supply chains leading to empty shelves at previously abundant grocery stores. The characteristic image of people hoarding toilet paper at big box stores is iconic because consumer goods that were taken for granted before the pandemic were suddenly in short supply. Of course, the impact of a dearth of consumer goods vs. a hospital bed or canisters of oxygen is incomparable and unevenly distributed over race, class, and socio-economic status. The psychological impacts of scarcity caused by the pandemic were similarly unevenly felt but still widespread and far-ranging.

Scarcity Impacts Pro-Environmental Behavior

The scarcity mindset can also have profound implications on pro-environmental behavior. Here we define pro-environmental behavior as any action that can potentially mitigate environmental degradation or increase awareness of environmental issues. As described earlier, perceptions of scarcity result in myopic thinking and foregoing future needs in favor of satisfying present constraints (Shah et al., 2012; Zhao and Tomm, 2018). However, environmental damage often occurs over a broad spatio-temporal horizon, which reduces motivation for sustainable choices via scarcity-induced myopia (van der Wal et al., 2018). Further, environmental sustainability also requires collective actions and cooperation within and between communities. Resource scarcity and the perception of scarcity, on the other hand, have been shown to reduce cooperation, increase ingroup preference and outgroup ostracization (Herzenstein and Posavac, 2019). Recent findings suggest that cooperative social norms which have arisen in times of plenty may dissolve when financial resources are scarce, and competition for those resources fierce (Nhim et al., 2019). However, not all types of scarcity have the same impact on cooperation. For example, in one study, farmers acted more cooperatively to conserve water during times of water scarcity (Nie et al., 2020). In another study, scarcity of social interactions during the current pandemic increased people's willingness to cooperate with public health measures (Civai et al., 2021).

Other empirical work suggests that the scarcity mindset may curb willingness to engage in pro-environmental behavior (Sachdeva and Zhao, 2020). In a hypothetical shopping task, participants were given a choice between purchasing sustainably made consumer goods vs. conventionally sourced ones. They were more likely to choose the conventional products when in a scarcity mindset (i.e., not having enough money). Participants in an abundance mindset (i.e., having enough money) preferred the sustainably produced products, even when controlling for price. This work suggests that scarcity deters people from engaging in pro-environmental actions, presumably by devoting attention to the financial problem at hand and diverting attention away from environmental causes. This said, natural resource scarcity (e.g., water scarcity) can promote choices of sustainable products (Sachdeva and Zhao, 2020).

Threat perception, which draws tremendous attentional resources, can explain why people experiencing financial scarcity forgo environmental values and actions during the pandemic. Threats experienced during the pandemic elicit a high level of worry. Since the emotional capacity to worry is thought to be finite (Capstick et al., 2015), being worried about the pandemic can cause less worry about other things, such as the environment and climate change (Sisco et al., 2020; Botzen et al., 2021). To summarize, scarcity caused by the pandemic can be one of the factors that contribute to the environmental degradation during the pandemic.

Pro-Environmental Behavior Reconceptualized

To some extent, these findings on scarcity curbing pro-environmental behavior are counter-intuitive. Some pro-environmental actions inherently conserve financial resources (e.g., those that reduce waste, promote reuse, and minimize reckless consumerism) and in times of economic crisis, this appears, prima facie, to be reason enough to reduce waste and overconsumption (Vox., 2020). Why then, as previous research suggests, are people under scarcity unwilling to engage in pro-environmental behavior?

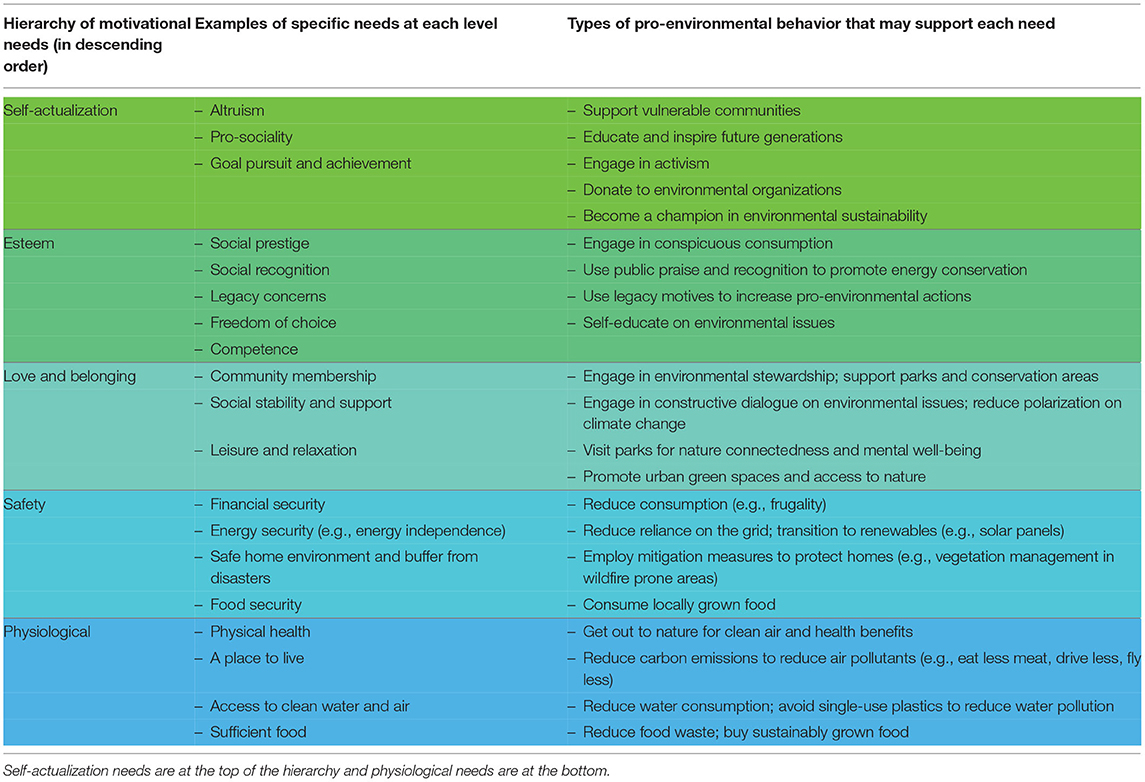

One explanation is that the unwillingness may arise from the traditional conceptualization of pro-environmental behavior in the broader psychological literature. Since at least the mid-1970s, pro-environmental behavior has been conceptualized as driven by higher-level needs, and are often value-laden and effortful (Dunlap, 1975; Stern et al., 1999). Consider Table 1, showing an early version of(Maslow, 1954 theory on the hierarchy of needs. In the original formulation of this hierarchy, the satisfaction of more fundamental needs such as physiological needs for food, water, and shelter, can lead to the pursuit of higher-order needs. At the highest level, self-actualization and transcendence needs are thought to drive pro-environmental behavior that yields benefits beyond the self. Note that we are not suggesting a reliance on (Maslow, 1954 specific rank order of needs, nor are we indicating agreement with his seeming belief in these needs mirroring stages of maturity or human development (Maslow, 1967). Rather, we argue that this is not only an inaccurate depiction of why people engage in pro-environmental behavior, but makes pro-environmental behavior seem out-of-reach and inaccessible for many people. Particularly, in times of scarcity, there are other pathways to sustainability that do not depend on higher-order needs. Emphasizing these distinct pathways, satisfying a multitude of human needs, may help reconceptualize pro-environmental behavior more broadly and bolster environmental protection as the world faces increasingly severe natural disturbances (Table 1).

Table 1. Pro-environmental behaviors that satisfy each level of needs based on Maslow (1954) motivational theory on the hierarchy of needs.

For instance, reducing energy consumption also reduces energy bills and financial stress, in addition to being pro-environment; and reducing vegetation and debris around a house can help protect the house from wildfires and also limit their spread (Olsen et al., 2017). In other words, although most pro-environmental behavior has been value-driven (Corraliza and Berenguer, 2000; Liu and Guo, 2018), there are many pragmatic reasons to be pro-environmental (Sachdeva and Zhao, 2020). Moreover, as experiences and perceptions of scarcity lead to an increased emphasis on the more foundational physiological and safety needs (Yuen et al., 2021), pro-environmental behavior that is better aligned with these lower-level needs may become easier to adopt.

Protecting Pro-Environmental Behavior

The perspective that we have put forward in this piece stems from an observation in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the midst of all the other pain, suffering, and loss experienced by millions across the world, the looming (and present) impacts of climate change were relegated to a lower rank of priorities (Medium., 2021). To some extent, this demotion of environmental concerns may have seemed justifiable—after all, millions of people are suffering right now. Yet, as researchers raising the alarm about the increase in plastic waste have said, if pro-environmental behavior is demoted during these disturbances, we are only creating more dire future scenarios and trading one crisis for another (Vanapalli et al., 2021). Scientists have been sounding the alarm for years that anthropogenic environmental degradation could lead to more frequent and deadly future pandemics (Weiss and McMichael, 2004; Barouki et al., 2021). For example, the destruction of natural habitats tends to drive wildlife out of their original living space and into contact with humans, thus increasing the risk of animal-to-human disease transmission (Roe et al., 2020; McNeely, 2021; Pelley, 2021). Furthermore, anthropogenic climate change could directly lead to deadlier future pandemics, as many diseases spread faster (Carlson et al., 2021) or expand their range and active season under higher temperatures (Curseu et al., 2010).

The path to mitigating these disturbances may rely on systemic change, which the COVID-19 pandemic can help catalyze (BBC, 2020; Saiz-Álvarez et al., 2020; Stanford Social Innovation Review., 2021). Nascent research already suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted materialism (Briggs et al., 2020; Mehta et al., 2020) and increased people's desire to engage with nature during the lockdown (Robinson et al., 2021; Johnson and Sachdeva, under review1). The latter in particular has been demonstrated to promote cooperation and act as a gateway to future environmental action (Zelenski et al., 2015). To make nature more accessible to as many people as possible, cities should continue to invest in green infrastructure as many have already done as part of social distancing protocols (Hanzl, 2020; Kleinschroth and Kowarik, 2020). Integration of green spaces into cites can be rethought as a tool to restore and promote mental health (Roe and McCay, 2021), since mental health has been severely impacted by not only the pandemic (Usher et al., 2020) but climate change and environmental crises (Berry et al., 2010; Afifi et al., 2012; Clayton, 2020). Furthermore, evidence suggests that if people are more future-oriented, scarcity can reinforce pro-environmental behavior, such as conserving water (Gu et al., 2020). Early education promoting civic participation and participatory governance may be an important resource in fostering a sustainability and future-oriented culture (Bäckstrand, 2003), which can ultimately transform scarcity into a driver of pro-environmental behavior, as opposed to a stressor.

Other institutional interventions on urban planning can ensure that pro-environmental actions are easier to execute in daily life and do not present an additional cognitive load for people. This includes investing in robust and convenient recycling and composting infrastructure and programs, more convenient public transportation, and subsidies for sustainable products. These measures should make pro-environmental behavior better aligned with scarce conditions so that the decision to behave sustainably is no longer a tradeoff between current needs and future needs. As noted earlier, scarcity, real or subjective, captures our attention often resulting in narrow, present benefits at the expense of future or more abstract gains. As Morton (2017) notes, if a behavior becomes habitual and in the service of current needs, it is more likely to persist even under scarcity. The micro and macro-level interventions suggested by the literature reviewed in this piece require significant investment and are difficult to implement in the best of circumstances. However, the pandemic offers a chance to make these substantial changes so that our societies, mindsets, and the environment itself become more resilient in the face of future disturbances.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SS and JZ conceived the framework of this paper. SS did the majority of the writing. JW wrote portions of Scarcity Impacts Pro-environmental Behavior, Pro-environmental Behavior Reconceptualized, and Protecting Pro-environmental Behavior sections, and made Table 1. JZ did the majority of editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work is funded by a grant from the USDA Forest Service (20-IJ-11242309-037) to SS and JZ.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Johnson, M., and Sachdeva, S. (under review). The multi-faceted impact of COVID-19 on social media users' wellbeing and relationship with urban nature. Front. Sustain. Cities.

References

Adyel, T. M. (2020). Accumulation of plastic waste during COVID-19. Science. 369, 1314–1315. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9925

Afifi, W. A., Felix, E. D., and Afifi, T. D. (2012). The impact of uncertainty and communal coping on mental health following natural disasters. Anxiety Stress Cop. 25, 329–347. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.603048

American Psychological Association (2020). Stress in America™ 2020: A National Mental Health Crisis. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/report-october (accessed July 27, 2021).

Ammendolia, J., Saturno, J., Brooks, A. L., Jacobs, S., and Jambeck, J. R. (2021). An emerging source of plastic pollution: environmental presence of plastic personal protective equipment (PPE) debris related to COVID-19 in a metropolitan city. Environ. Pollut. 269:116160. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116160

Bäckstrand, K. (2003). Civic science for sustainability: reframing the role of experts, policy-makers and citizens in environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Politics 3, 24–41. doi: 10.1162/152638003322757916

Barouki, R., Kogevinas, M., Audouze, K., Belesova, K., Bergman, A., Birnbaum, L., et al. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and global environmental change: emerging research needs. Environ. Int. 146:106272. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106272

BBC (2020). Coronavirus: How the World of Work May Change Forever. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20201023-coronavirus-how-will-the-pandemic-change-the-way-we-work (accessed August 26, 2021).

Benson, N. U., Bassey, D. E., and Palanisami, T. (2021). COVID pollution: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on global plastic waste footprint. Heliyon 7:e06343. doilink[10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06343]10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06343

Berry, H. L., Bowen, K., and Kjellstrom, T. (2010). Climate change and mental health: a causal pathways framework. Int. J. Public Health. 55, 123–132. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0112-0

Botzen, W., Duijndam, S., and van Beukering, P. (2021). Lessons for climate policy from behavioral biases towards COVID-19 and climate change risks. World Dev. 137:105214. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105214

Briggs, D., Ellis, A., Lloyd, A., and Telford, L. (2020). New hope or old futures in disguise? Neoliberalism, the Covid-19 pandemic and the possibility for social change. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 40, 831–848. doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-07-2020-0268

Cannon, C., Goldsmith, K., and Roux, C. (2019). A self-regulatory model of resource scarcity. J. Consum. Psychol. 29, 104–127. doi: 10.1002/jcpy.1035

Capstick, S., Whitmarsh, L., Poortinga, W., Pidgeon, N., and Upham, P. (2015). International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 6, 35–61. doi: 10.1002/wcc.321

Carlson, C. J., Albery, G. F., Merow, C., Trisos, C. H., Zipfel, C. M., Eskew, E. A., et al. (2021). Climate change will drive novel cross-species viral transmission. BioRxiv [Preprint]. Available online at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.24.918755v3.abstract (accessed July 30, 2021).

Chowdhury, H., Chowdhury, T., and Sait, S. M. (2021). Estimating marine plastic pollution from COVID-19 face masks in coastal regions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 168:112419. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112419

Civai, C., Caserotti, M., Carrus, E., Huijsmans, I., and Rubaltelli, E. (2021). Perceived scarcity and cooperation contextualized to the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv [Pre Print]. Available online at: https://psyarxiv.com/zu2a3/ (accessed November 15, 2021).

Clayton, S. (2020). Climate anxiety: psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 74:102263. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263

Corraliza, J. A., and Berenguer, J. (2000). Environmental values, beliefs, and actions: a situational approach. Environ. Behav. 32, 832–848. doi: 10.1177/00139160021972829

Curseu, D., Popa, M., Sirbu, D., and Stoian, I. (2010). “Potential impact of climate change on pandemic influenza risk,” in Global Warming. Boston, MA: Springer, 643–657.

de Bruijn, E. J., and Antonides, G. (2021). Poverty and economic decision making: a review of scarcity theory. Theory Decis. 2021, 1–33. doi: 10.1007/s11238-021-09802-7

Dunlap, R. E. (1975). The impact of political orientation on environmental attitudes and actions. Environ. Behav. 7, 428–454. doi: 10.1177/001391657500700402

Echegaray, F. (2021). What POST-COVID-19 lifestyles may look like? Identifying scenarios and their implications for sustainability. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 27, 567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2021.01.025

Frankenhuis, W. E., and Nettle, D. (2020). The strengths of people in poverty. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 29, 16–21. doi: 10.1177/0963721419881154

Gadermann, A. C., Thomson, K. C., Richardson, C. G., Gagné, M., McAuliffe, C., Hirani, S., et al. (2021). Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 11:e042871. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042871

Gu, D., Jiang, J., Zhang, Y., Sun, Y., Jiang, W., and Du, X. (2020). Concern for the future and saving the earth: When does ecological resource scarcity promote pro-environmental behavior? J. Environ. Psychol. 72:101501. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101501

Hamilton, R. (2021). Scarcity and coronavirus. J. Public Policy Mark. 40, 99–100. doi: 10.1177/0743915620928110

Hanzl, M. (2020). Urban forms and green infrastructure—the implications for public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cities Health 2020, 1–5. doi: 10.1080/23748834.2020.1791441

Herzenstein, M., and Posavac, S. S. (2019). When charity begins at home: how personal financial scarcity drives preference for donating locally at the expense of global concerns. J. Econ. Psychol. 73, 123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2019.06.002

Hiemstra, A., Rambonnet, L., Gravendeel, B., and Schilthuizen, M. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 litter on animal life. Anim. Biol. 71, 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1163/15707563-bja10052

International Labour Organization (2020). ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Updated Estimates and Analysis. Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-responses/WCMS_755910/lang–en/index.htm (accessed July 27, 2021).

Kleinschroth, F., and Kowarik, I. (2020). COVID-19 crisis demonstrates the urgent need for urban greenspaces. Front. Ecol. Environ. 18:318. doi: 10.1002/fee.2230

Liu, S., and Guo, L. (2018). Based on environmental education to study the correlation between environmental knowledge and environmental value. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. 14, 3311–3319. doi: 10.29333/ejmste/103737

Mahmood, S., Hasan, K., Carras, M. C., and Labrique, A. (2020). Global preparedness against COVID-19: we must leverage the power of digital health. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 6:e18980. doi: 10.2196/18980

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., and Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science. 341, 976–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1238041

Maslow, A. H. (1967). A theory of metamotivation: the biological rooting of the value-life. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 7, 93–127. doi: 10.1177/002216786700700201

McNeely, J. A. (2021). Nature and COVID-19: the pandemic, the environment, and the way ahead. Ambio 2021, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s13280-020-01447-0

Medium. (2021). Media Coverage of Climate Change During COVID-19. Available online at: https://medium.com/the-nature-of-food/media-coverage-of-climate-change-during-covid-19-20082627c82f (accessed August 23, 2021).

Mehta, S., Saxena, T., and Purohit, N. (2020). The new consumer behaviour paradigm amid COVID-19: Permanent or transient?. J. Health Manag. 22, 291–301. doi: 10.1177/0972063420940834

Morton, J. M. (2017). Reasoning under scarcity. Aust. J. Philos. 95, 543–559. doi: 10.1080/00048402.2016.1236139

Mullainathan, S., and Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much. Times Books/Henry Holt and Co.

Nhim, T., Richter, A., and Zhu, X. (2019). The resilience of social norms of cooperation under resource scarcity and inequality—an agent-based model on sharing water over two harvesting seasons. Ecol. Complex. 40:100709. doi: 10.1016/j.ecocom.2018.06.001

Nie, Z., Yang, X., and Tu, Q. (2020). Resource scarcity and cooperation: Evidence from a gravity irrigation system in China. World Dev. 135:105035. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105035

Olsen, C. S., Kline, J. D., Ager, A. A., Olsen, K. A., and Short, K. C. (2017). Examining the influence of biophysical conditions on wildland–urban interface homeowners' wildfire risk mitigation activities in fire-prone landscapes. Ecol. Soc. 22:121. doi: 10.5751/ES-09054-220121

PBS (2021). The Plastic Industry Is Growing During COVID. Recycling? Not So Much. Available online at: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/the-plastic-industry-is-growing-during-covid-recycling-not-so-much (accessed July 30, 2021).

Pelley, J. (2021). Preventing pandemics by protecting tropical forests. Front. Ecol. Environ. 146:2327. doi: 10.1002/fee.2327

Pereira, M., and Oliveira, A. M. (2020). Poverty and food insecurity may increase as the threat of COVID-19 spreads. Public Health Nutr. 23, 3236–3240. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020003493

Pew Research Center (2021). A Year Into the Pandemic, Long-Term Financial Impact Weighs Heavily on Many Americans. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/03/05/a-year-into-the-pandemic-long-term-financial-impact-weighs-heavily-on-many-americans (accessed July 27, 2021).

Reuters (2020). The Plastic Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/health-coronavirus-plastic-recycling (accessed July 30, 2021).

Robinson, J. M., Brindley, P., Cameron, R., MacCarthy, D., and Jorgensen, A. (2021). Nature's role in supporting health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a geospatial and socioecological study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18:2227. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052227

Roe, D., Dickman, A., Kock, R., Milner-Gulland, E. J., and Rihoy, E. (2020). Beyond banning wildlife trade: COVID-19, conservation and development. World Dev. 136:105121. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105121

Roe, J., and McCay, L. (2021). Restorative Cities: Urban Design for Mental Health and Wellbeing. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Sachdeva, S., and Zhao, J. (2020). Distinct impacts of financial scarcity and natural resource scarcity on sustainable choices and motivations. J. Consum. Behav. 20, 203–217. doi: 10.1002/cb.1819

Saiz-Álvarez, J. M., Vega-Muñoz, A., Acevedo-Duque, Á., and Castillo, D. (2020). B corps: a socioeconomic approach for the COVID-19 post-crisis. Front. Psychol. 11:1867. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01867

Shah, A. K., Mullainathan, S., and Shafir, E. (2012). Some consequences of having too little. Science 338, 682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1222426

Shah, A. K., Shafir, E., and Mullainathan, S. (2015). Scarcity frames value. Psychol. Sci. 26, 402–412. doi: 10.1177/0956797614563958

Shah, A. K., Zhao, J., Mullainathan, S., and Shafir, E. (2018). Money in the mental lives of the poor. Soc. Cogn. 36, 4–19. doi: 10.1521/soco.2018.36.1.4

Silva, A. L. P., Prata, J. C., Walker, T. R., Duarte, A. C., Ouyang, W., Barcelò, D., et al. (2021). Increased plastic pollution due to COVID-19 pandemic: challenges and recommendations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 405:126683. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126683

Sisco, M. R., Constantino, S. M., Gao, Y., Tavoni, M., Cooperman, A. D., Bosetti, V., et al. (2020). A finite pool of worry or a finite pool of attention? Evidence and qualification. Nature Portfolio. Available online at: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-98481/v1 (accessed July 30, 2021).

Solomon, M. Z., Wynia, M., and Gostin, L. O. (2020). Scarcity in the Covid-19 pandemic. Hastings Cent. Rep. 50, 3–3. doi: 10.1002/hast.1093

Stanford Social Innovation Review. (2021). Rethinking Social Change in the Face of Coronavirus. Available online at: https://ssir.org/rethinking_social_change_in_the_face_of_coronavirus (accessed August 26, 2021).

Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., and Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 81–97.

The Lancet Public Health (2020). Will the COVID-19 pandemic threaten the SDGs? Lancet Public Health. 5:e460. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30189-4

The World Bank (2020). COVID-19 to Add as Many as 150 Million Extreme Poor by 2021. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/10/07/covid-19-to-add-as-many-as-150-million-extreme-poor-by-2021 (accessed July 27, 2021).

Time (2021). Garbage Freaking Everywhere' as Americans Venture Outdoors After a Year of Lockdowns. Available online at: https://time.com/5949983/trash-pandemic/ (accessed July 27, 2021).

United Nations (2020). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. Available online at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020 (accessed July 27, 2021).

Usher, K., Durkin, J., and Bhullar, N. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 29:315. doi: 10.1111/inm.12726

van der Wal, A. J., van Horen, F., and Grinstein, A. (2018). Temporal myopia in sustainable behavior under uncertainty. Int. J. Res. Mark. 35, 378–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2018.03.006

Vanapalli, K. R., Sharma, H. B., Ranjan, V. P., Samal, B., Bhattacharya, J., Dubey, B. K., et al. (2021). Challenges and strategies for effective plastic waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 750:141514. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141514

Vox. (2020). The Novel Frugality. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2020/4/30/21241218/frugality-coronavirus-scallions-aluminum-foil-reuse (accessed July 30, 2021).

Waste Dive. (2019). Where Curbside Recycling Programs Have Stopped in the US. Available online at: https://www.wastedive.com/news/curbside-recycling-cancellation-tracker/569250 (accessed July 30, 2021).

Weiss, R. A., and McMichael, A. J. (2004). Social and environmental risk factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Nat. Med. 10(12 Suppl), S70-6. doi: 10.1038/nm1150

Yuen, K. F., Leong, J. Z. E., Wong, Y. D., and Wang, X. (2021). Panic buying during COVID-19: survival psychology and needs perspectives in deprived environments. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 62, 102421. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102421

Zelenski, J. M., Dopko, R. L., and Capaldi, C. A. (2015). Cooperation is in our nature: nature exposure may promote cooperative and environmentally sustainable behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 42, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.01.005

Zhao, J., and Tomm, B. (2017). “Attentional trade-offs under resource scarcity. Augmented cognition: enhancing cognition and behavior in complex human environments, Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence,” in International Conference on Augmented Cognition, 78–97

Keywords: scarcity mindset, pro-environmental behavior (PEB), COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, environmental degradation, sustainability, hierarchy of needs

Citation: Sachdeva S, Wu JS-T and Zhao J (2021) The Impact of Scarcity on Pro-environmental Behavior in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:767501. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.767501

Received: 30 August 2021; Accepted: 23 November 2021;

Published: 14 December 2021.

Edited by:

Elise Louise Amel, University of St. Thomas, United StatesReviewed by:

Gabriella Maselli, University of Salerno, ItalyRemo Santagata, Parthenope University of Naples, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Sachdeva, Wu and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James Shyan-Tau Wu, amFtZXMuc2h5YW50YXUud3VAdWJjLmNh

Sonya Sachdeva

Sonya Sachdeva James Shyan-Tau Wu

James Shyan-Tau Wu Jiaying Zhao

Jiaying Zhao