- 1Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Applied Sciences Erfurt, Erfurt, Germany

- 2Center for Global Urbanism, Ural Federal University, Ekaterinburg, Russia

Since the concept of energy poverty first emerged, studies have combined normative orientations, analytical approaches and policy review to engage with energy deprivation as a problematic feature of contemporary societies. Over the past decade, this scholarship has aimed to conceptualize the normative grounds for critique, empirical work and policy design when engaging with the interplay of social life and energy systems. Scholars now include dynamic and complex concepts such as energy vulnerability and energy deprivation and are shifting toward the incorporation of social-philosophical justice concepts. However, in most of these writings on energy equality or energy justice, material aspects like access to (clean) energy, affordable energy costs, and material deprivation are in the foreground. This resonates with the energy poverty literature's emphasis on energy poverty as a material deprivation (Longhurst and Hargreaves, 2019). The way that energy poverty can result in financial stress, cold homes, poor health and the need to cut other basic expenditures is well-explored, but the less tangible, non-material deprivations stemming from energy poverty are less well-captured. We instead find it beneficial to also focus on the less tangible, non-material deprivations which have not yet been captured conceptually, and argue that the concept of dignity can be a pathway to investigate them. We aim to demonstrate how “dignity” can add to the normative orientations of energy poverty and energy justice research, and complement existing frames. With an empirical position in Europe we will draw from own empirical data and existing literature to illustrate how households living in energy poverty, or being cut off from energy provision, experience dignity violations.

Introduction

Since the concept of energy poverty first emerged, studies have used normative orientations to inform their analytical approaches when investigating energy-related deprivations. Over the past decade, this scholarship has aimed to conceptualize the normative grounds for critique, empirical work, and policy review and design when engaging with the interplay of social life and energy systems. When it comes to the social dimensions of energy distribution, the normative orientations in energy research have evolved from their rather static view of poverty as a social problem. Scholars now include dynamic and complex concepts such as energy vulnerability and energy deprivation (Bouzarovski, 2013; Middlemiss and Gillard, 2015), and are shifting toward the incorporation of social-philosophical justice concepts. Scholars increasingly make ethical or normative statements, that is the ones expressing certain values and proclaiming a certain condition desirable or critical.

In exploring how this literature can be instructive for the transition to a fair, socially and ecologically just future, the energy justice literature stresses three dimensions: distributional justice or equity; recognition or attention to social difference; and procedural justice or democracy (Walker, 2009; Jenkins et al., 2016). These three tenets are sometimes augmented with the idea of restorative justice (Heffron and McCauley, 2018). Further, the concept of capabilities is used to explore the basic needs for a decent life, leaning on Nussbaum's idea that a necessary set of principles must be fulfilled across contexts to achieve a life that can be called livable (Day et al., 2016). Pellegrini-Masini et al. (2020) emphasizes energy equality as a core concept for energy justice and the benchmark by which the achievement of energy justice can be measured. However, in most of these writings, material aspects like access to (clean) energy, affordable energy costs, and material deprivation are in the foreground. This resonates with the energy poverty literature's emphasis on energy poverty as a material deprivation (Longhurst and Hargreaves, 2019). The way that energy poverty can result in financial stress, cold homes, poor health and the need to cut other basic expenditures is well-explored, but the less tangible, non-material deprivations stemming from energy poverty are less well-captured.

Our aim here is to aid in filling this gap by applying a dignity perspective to the lived experiences of energy-poor households. A review of both scholarly writings and policy documents reveals that, while material aspects are in the foreground, dignity as a goal and value only enters the picture indirectly. For example, in their October 14th 2020 recommendation, the European Commission called for “decent housing,” defined by adequate access to energy and energy efficiency in order to avoid high energy usage and costs. After defining energy poverty as “a situation in which households are unable to access essential energy services” (European Commission, 2020), the document recognizes the scope of the problem: “With nearly 34 million Europeans unable to afford to keep their homes adequately warm in 2018, energy poverty is a major challenge for the EU.” In a second point, the document defines “a decent standard of living and health” by noting that “adequate warmth, cooling, lighting, and energy to power appliances are essential services” (European Commission, 2020). This shows a common pattern in how dignity is conceived: it's achieved when a basic or material standard is met. As we will show, an in-depth consideration of dignity would bring rather different aspects into play.

Non-material deprivations present in the literature comprise quantitative studies showing how energy poverty correlates with mental illness and lower levels of subjective well-being (Biermann, 2016; Thomson et al., 2017). More recently, Longhurst and Hargreaves (2019) presented a pioneering study on emotional engagements with energy poverty. This study is part of a recent rise in interest in the lived experience of energy-poor households (e.g., Middlemiss and Gillard, 2015; Butler and Sherriff, 2017; Middlemiss et al., 2018; Willand and Horne, 2018; Yoon and Saurí, 2019). In most of this literature on the lived experience of energy-poor households, the actual material deprivation, and the situations of the household members as well as their coping strategies are again the focus. But from these writings, we also learn about the subjective perceptions, mental states, and how energy poverty impacts social relations. The “cold home,” a situation where a household cannot heat the house or the flat sufficiently (Boardman, 1991), is not just a state of material deprivation causing illness. Qualitative studies show how a cold home causes loneliness and exclusion when people cannot - or feel ashamed to - invite friends and family, and in consequence reduce social contacts at large (Brunner et al., 2017; Middlemiss et al., 2019).

Our premise is that non-material deprivations need more attention to reach a broader picture of the meaning of energy poverty for societies. Scholars justifiably connect energy poverty with well-being (Biermann, 2016; Thomson et al., 2017). However, the ways in which energy-poor households are affected by and cope with the challenges of not being able to afford the necessary level of energy—a widely accepted definition of energy poverty (e.g., Bouzarovski and Petrova, 2015)—should be seen beyond money flows, energy prices and efficiency questions largely addressed in the literature. We believe these struggles must also be seen in light of emotions and affect, stigma, and prejudice. We aim to employ the conceptual framework of dignity and dignity violation in order to understand the non-material deprivation that energy-poor households experience. Fukuyama (2018) for instance, argues that much of what is commonly seen as material deprivation – and thus the economic motivation for resentment, unrest, or protest – would be more accurately described as the violation of dignity, here largely defined as recognition and respect. Hochschild (2016), Gest (2016), and Illouz (2020) demonstrate how dignity violations, such as feelings of neglect or of being left behind, indifferent attitudes from “elites,” feelings of inferiority, and the fear of future loss of status within the respective society, induce resentment and voting for politicians who follow nationalist, discriminating policies. Although the exact composition and typology of such non-material deprivations remain to be explored, recent writings have integrated the idea that dignity-violations are among the causes for such changes in societies, even claiming that dignity-violations are of higher relevance than material deprivation.

The concept of dignity may be an entry point for a normatively-framed engagement with non-material deprivations resulting from energy poverty. Dignity has been debated extensively in philosophical writings, where it has enjoyed attention similar to concepts of justice. In other disciplines, it has also been widely used to discuss normative orientations, for example in biology and genetics when reflecting upon the ethical dimension of research on the human embryo. Interestingly, in the wider literature on sustainability transitions, the concept has not yet entered the debate.

We aim to demonstrate how “dignity” can add to the normative orientations of energy research, and can provide a different perspective or complement existing frames. With an empirical position in Europe (and also being aware of the differences among the European and the global debates on energy poverty, see Bouzarovski and Petrova, 2015), we will draw from own empirical data and existing literature to illustrate how households living in energy poverty, or being cut off from energy provision, experience dignity violations. The qualitative data was gathered in various research projects over the past 6 years and underwent a secondary analysis for the purposes of this paper. Altogether, 27 interviews from a pool of 45 were included in the analysis based on their relevance to the topic. Transcripts of these interviews were coded deductively, using the aspects of dignity and dignity violation introduced below, and the relevant passages were interpreted to find patterns of dignity violations. We also included published articles on the lived experience of energy-poor households in this endeavor, including unofficial publications like a master's thesis by Franke (2019). In the interpretation, we apply careful consideration to the contexts of energy poverty experiences. Our judgement and positionality is a European perspective, non-material energy deprivation may differ largely from this in other countries.

This paper is structured as follows: we first provide a brief account of our understanding of dignity, then touch upon notions of dignity in energy poverty and energy justice scholarship before presenting the ways that dignity and dignity violations are reflected in the experiences of households. In the discussion, we establish how a “dignity lens” can stimulate a more nuanced understanding of the non-material aspects of energy justice.

Dignity: Theoretical Considerations

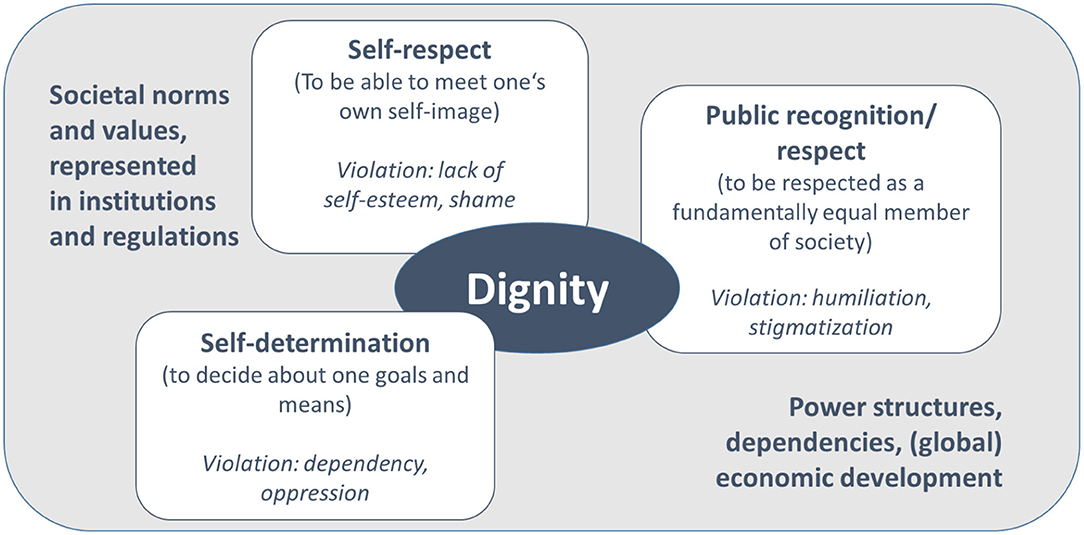

Stemming from the Latin “dignitas” (worthiness), dignity is most often defined as the moral status of a person (Forst, 2011). While equity and distributional justice often focus on the socio-economic status of a person, the concept of dignity we employ addresses how a person is given value and respect in a society. The term “dignity” is widely used in politics and everyday life, and its individual significance and political salience also complicate the ways in which the concept is experienced and understood. What provides the common foundation for all these differences and complexities is the notion of the universal worth of all people without exception, of a universal value which everyone is entitled to and which is strongly linked with autonomy and liberty. Habermas (2010: 466) demonstrates that human dignity “Is the moral “source” from which all of the basic rights derive their meaning.” However, the notion of dignity as a universal value is rather new. Dignity was historically seen as something to be achieved, a status that marks a respected position in society (Debes, 2017). Today, the status-derived form of dignity still lingers in expressions like “the men of honor,” but it has lost significance. The concept of dignity today implies that members of society respect each other as fundamentally equal, which is a first defining aspect of dignity as derived from philosophical literature, see Figure 1.

In academic literature, to be respected by others is then seen as the basis for achieving self-respect. For the purposes of this article, it is important to emphasize that dignity and its “negations” (indignity and humiliation) are considered to be subjectively experienced and thus have an impact on the self-respect of a person. One has dignity when one believes in one's worth, when one is proud of oneself, and when one leads a meaningful life which is worthy of the respect of others. Weber-Guskar (2017) pronounce that self-respect is found when a person is able to meet their own self-image—and it's hard to find when one fails to achieve that very image (Brandhorst and Weber-Guskar, 2017). Thus, humans perpetually struggle to reach self-determined norms. Bloch's famous metaphor of the “upright gait” (der aufrechte Gang) illustrates the outlined meaning of dignity as moral status captured in the balanced interrelation of respect and self-respect (Bloch, 1986: 174).

A third defining aspect in the philosophical literature on dignity is self-determination. Von der Pfordten, a contemporary German philosopher, defines self-determination as the grand human dignity which is an “inner, necessary and unchangeable characteristic of humanity” (Von der Pfordten, 2016: 9f.). Beyond the control over your own body, he suggests to define this grand human dignity as the self-determination of one's own interests. In contrast, the idea of status dignity that elevates individuals above the rest is seen here as the small dignity, and the idea of equality as a medium dignity (Von der Pfordten, 2016). Most convincingly, in our view, Forst (2011: 968) points to the political implication of seeing dignity as self-determination: “the general concept of human dignity is … inextricably bound up with that of self-determination in a creative and simultaneously moral sense that already involves a political component. … At stake is one's status of not being subject to external forces that have not been legitimized to exercise rule – in other words, it is a matter of being respected in one's autonomy as an independent being.”

The three aspects of respect, self-respect, and self-determination are interrelated and together provide a way of operationalizing the concept for applied research on dignity and its violations. This can also be discerned in Forst's statement that “to act with dignity means being able to justify oneself to others; to be treated in accordance with this dignity means being respected as such an equal member; to renounce one's dignity means no longer regarding oneself as such a member but as inferior; and to treat others in ways that violate their dignity means regarding them as lacking any justification authority.” (2011: 968f.).

Dignity violations are commonly described as humiliations (Statman, 2000). The violations and deprivations of dignity are morally reproachable and normatively problematic. Brandhorst and Weber-Guskar (2017) defines humiliation as the experience of being forced into a negative view of yourself in a situation of powerlessness. An external image is forced upon a person that is different from their self-image; people feel ashamed, degraded, inferior (Weber-Guskar, 2017: 222–224). Moral philosopher Margalit (1996: 51) broadens the notion of humiliation to the level of societies when he argues that “violation of moral integrity is sufficient for branding a society as humiliating … A decent society is one whose institutions do not violate the dignity of the person in its orbit,” a claim which raises questions about the moral condition of today's societies, economies and political systems in general. Margalit makes the concept of humiliation the focus of his book on decent society, thus exhibiting a strong commitment to both the normative reasoning (“What is a decent society?”) and the realistic rendering of today's world (“Why is there so much humiliation?”). Important for our further arguments, he shows that ensuring people get what they deserve is not necessarily all that matters, since the distribution of social benefits and the imposition of their preconditions may very well be conducted in a way that is also humiliating (Margalit, 1996: 122).

As signs of the violation of one's self-respect, stigma and shame seem most important. Shame is a primary affect and a powerful emotion (Tomkins, 1963). It can be produced by a number of cultural, economic, political and social factors (Sayer, 2005). Shame can be induced by experiences of poverty, racism, struggles during adolescence, homophobia, and the like. In contrast to guilt, which is mostly experienced internally, shame is relational: there is almost always an individual, group or institution which inflicts shame. Interiorization of repeated experiences of shame results in individuals shaming themselves – the presence of others is not necessary for this emotional process (Tomkins, 1963; Kaufman, 1993).

So, the challenge here is to analytically combine the arguments on structural inequality (because, again, it is societal shame which falls on poor individuals) with our increasing knowledge of the behaviors of neoliberal governments. These governments impose the burden of providing for basic needs onto households themselves, only to then inflict shame on those incapable of doing so due to poverty. “Blaming the poor” is a prominent phrase depicting this ideology and reasoning (Dorey, 2010; Greenbaum, 2015).

Figure 1 also highlights the contingent and relational nature of the concept of human dignity emphasized by most contemporary authors (e.g., Brandhorst and Weber-Guskar, 2017; Clark-Miller, 2017; Zylberman, 2018). The values and norms, economic structures, institutions, and the power relations of a given societal context are significant to the experience of dignity (or the lack thereof) meaning that the same circumstances can be dignifying in one context and humiliating in another (Forst, 2011: 967). On the micro-level, a relational perspective emphasizes that dignity does not exist as a personal property, but rather emerges in interpersonal relations. Dignity—as well as dignity violations—come to the fore in “dignity encounters,” which are often shaped by asymmetrical structures within society, that is, “when one actor has more power, authority, knowledge, wealth, or strength than the other” (Jacobson et al., 2009: 3). What exacerbates asymmetries is that states have withdrawn from the provision of social benefits and reduced their social policy. They now outsource a great deal of these services to private agencies. Yet states remain involved as the main regulators that require “outcomes” and “impact.”

To achieve dignity, what is needed is not cultures of dependency and paternalistically treated citizens but, as Forst (2011: 967) argues, an active conception of dignity. The active conception of dignity here is introduced to problematize a more conventional, “passive” understanding of dignity where dignity only concerns satisfying basic needs equally across the world by way of social improvements. We agree with Forst that more effort needs to be taken to resist the wide-spread tendency of subjecting citizens to being neglected, abandoned, and turned into waste by those who rule for the sake of their legitimacy. On issues concerning human dignity, therefore, the relative deprivation forced by others is decisive: “Thus the central phenomenon of the violation of dignity is not the lack of the necessary means to live a “life fit for a human being,” but the conscious violation of the moral status of being a person who is owed justifications for existing relations or specific actions.” Dignity, in this understanding, is not to think of needs, ends or conditions, “but of social relations, of processes, interactions and structures between persons, and of the status of individuals within them.” (Forst, 2011). Forst exemplifies this claim by referring to forms of poverty relief through charity or social welfare payment. While such poverty relief payments may satisfy material needs, they may “treat the “needy” in a condescending manner” and thus be “no less degrading than poverty itself.” (Forst, 2011).

Drawing from such contributions, this paper explores the three defining aspects of dignity highlighted above as well as their violations: (1) public respect and recognition (rather than humiliation and disrespect); (2) self-respect (rather than shame and loss of self-worth); (3) self-determination (rather than dependence and helplessness). We aim to demonstrate how these can be relevant points of attention for energy justice research and thinking.

Notions of Dignity in Energy Poverty and Energy Justice Scholarship

To explore how dignity is related to energy poverty, we start by summarizing how dignity appears in writings on the subject. While—to the best of our knowledge—dignity has never been addressed as a concept in research on energy poverty, various, most often implicit, notions of dignity do presently exist.

First, dignity is listed among other goods human beings are entitled to, but often deprived of in reality, whether this is a warm house or a good education. The word is mentioned incidentally by authors specializing in the technical and/or regulatory constraints of energy delivery: “Energy is fundamental to economic and social development; to reduce poverty and continue to grow. It supports people as they seek a whole range of development benefits: cleaner and safer homes, lives of greater dignity and less drudgery, to better livelihoods and better quality education and health services” (Bilgiç, 2017: 1). Consequently, dignity offences figure among other negative tendencies marking today's urban social life. For instance, Balachandra (2012: 165) posits with regard to unequal access to modern energy sources: “The implications are typically in the form of income poverty, primitive lifestyles, loss of dignity, physical hardship, health hazards, lack of employment and polluted environment.” By the same token, Chakravarty and Tavoni (2013: 67) claim that “Modern sources of energy like electricity and clean cooking fuels are the prerequisite of a life with a minimal standard of comfort and dignity. There is a tremendous imbalance in the access to and consumption of these energy sources today: the poorest 3 billion people suffer from debilitating energy poverty while the richest 1 billion consume an overwhelming fraction. Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and South East Asia are home to most of the world's energy poor.”

Second, dignity-related notions are also present in claims for “decent housing” in reports that feature people ashamed of the dark and cold homes that result from severe energy poverty. Here, “decent” and “dignifying” are used as adverbs to describe the standard that should be achieved. Ever since the pioneering work of Boardman (1991, 2010), the problems of cold homes, substandard dwellings unable to provide some level of comfort, and income poverty preventing households from heating their homes to an acceptable level have been core concerns of energy poverty writings. Thermal comfort has been at the heart of policies in the UK and Ireland, with the introduction of the Decent Homes Standard in 2000 in England, for example. A decent home is defined here “against four specified criteria: a minimum statutory standard, disrepair, modernization, and thermal comfort” (Hulme, 2012: 98). All social housing had to meet these “standards of decency” by 2010 (Hulme, 2012).

Leaving Europe for a moment, the words “dignified housing” and “dignified living” appear particularly often in work on the non-Western countries where “decent” is often reduced to “fit for survival” or to achieving minimum standards for material well-being. A case in point is the Decent Living Energy Project, aimed to define a “universal, irreducible and essential set of material conditions for achieving basic human well-being” (Rao and Min, 2018). In a similarly universalist, basic approach to a decent living, other scholars acknowledge that a minimum provision of energy cannot be applied without reference to a specific context. When discussing indicators for the measurement of energy poverty, Pachauri and Spreng (2011: 7501) argue that a minimum for cooking and lighting cannot be the benchmark for developed nations. Similarly, Bulkeley et al. (2014: 32) see dignified housing as an improvement within a given context. Looking at Cape Town and São Paulo, they stress “a decent standard housing that moves away from the cheaply built housing in which key costs such as thermal efficiency are transferred from the state to households.”

Third, dignity features in writings—and actions—that employ a human rights-oriented approach to energy poverty. “The detrimental developmental impacts related to energy poverty in Africa constitute a challenge to the full realization of human rights. Furthermore, access to energy should be seen as an economic and/or social right which is indispensable to the notion of human dignity” (Barnard and Scholtz, 2013: 60, see also Sing-hang Ngai, 2012). It is hardly surprising that dignity is part of calls within social movements for combatting energy poverty, as in Bulkeley et al. (2014): “The raising of the quality of housing infrastructures, via low carbon interventions, rationalities and financing, may provide a potential platform for social justice campaigners to coalesce around and further articulate the demand for dignified lives through housing quality as well as quantity.” Within the emerging social movement that advocates for a right to energy, the Right to Energy Coalition claims on their website that “Energy is a basic human right: no one should ever have to choose between eating, lighting or warming one's home. An end to energy poverty is vital for social justice and fighting the climate crisis. Access to energy can be a matter of life and death and it is a condition for living a dignified life.”1 While dignity is taken up prominently and explicitly, it is not used conceptually. The main claim made here is that dignity is the moral source upon which the claim for a right to energy as part of human rights is based. Here, we see a more conceptual understanding of dignity as a valuable contribution to this debate.

Fourth, and finally, dignity appears in the energy justice literature under the tenet of “recognition.” While—at least in our view—the meaning of the other two tenets (distributional and procedural justice) are much more clear, recognition seems to be the least elaborated one. In some definitions, recognition points to the requirement to understand different social groups and their needs, a use that resembles the reading of justice tenets in the “just city” - literature, where Fainstein (2010) argues prominently for equity, democracy and diversity. For Fainstein, recognition requires apprehending the social diversity of society and the different needs to be acknowledged when designing urban development. McCauley et al. (2019: 917) for instance define recognition justice in low carbon transitions as a call to recognize those who are overlooked, the “neglected sections of society,” and to instead “reflect upon [the question] “who exactly should we focus on when we think of energy victims?” This process is referred to as post-distributional, or recognition-based justice. In their review article on energy justice concepts, Pellegrini-Masini et al. (2020) agree with the three tenets of energy justice and locates the importance of dignity in the third tenet, recognition, as “the need to recognize the dignity and rights of all individuals and the need for them to be included and therefore avoid the conditions of deprivation, such as that of fuel poverty.”2 Here again, dignity appears to be something that is achieved through overcoming material deprivation. Jenkins et al. (2018) offer a slightly different account of justice as recognition, which to them “represents a concern for processes of disrespect, stigmatization and othering—questioning who is, or who is not, included [in the transition to low carbon systems].” The emphasis of this article, however, is on more material issues. Elsewhere, Jenkins et al. (2016) provide the most elaborate understanding of recognition justice when they combine a call to recognize those who are overlooked with the combating of disrespect. This is exemplified in the recognition of the specific energy needs of UK households often stereotyped as uninformed or careless about usage (Jenkins et al., 2016: 177). However, they place recognition justice second to distribution and process.

In sum, the concept of dignity—where used in writings on ethical and normative issues in energy poverty and energy transition literature—appears briefly as part of the conventional set of normative “reminders,” or the points to check, rather than in a thoroughly outlined concept. This also holds true for energy poverty literature. Where notions of decent living or housing are present, the need for access to energy services is highlighted as a means to achieve a dignifying life. But what this means exactly remains unclear. Claims for dignity are put forward by social movements and NGOs, and echoed in the writings on civil society actions, but not made analytically accessible. To take this a step further, we now focus on some empirical data showing how the three aspects of dignity derived from the literature, namely respect, self-respect, and self-determination, can be employed to reflect the complexities of energy poverty. In the following, we review the three aspects of dignity derived from the dignity literature - respect, self-respect, and self-determination. - to explore how they feature in experiences of energy-poor people and households.

Disrespected, Ashamed and Dependent: Households in Energy Poverty

In the interviews, participants emphasized emotional burdens rooted in experiences like not being able to heat their homes or cook warm meals, or undergoing a disconnection. In the following, we review the three aspects of dignity derived from the dignity literature to explore how they feature in experiences of energy-poor people and households.

Stigmatization, Humiliation, Feelings of Inferiority

Humiliation, stigmatization and disrespect are described in a number of ways by energy-poor households, and they occur in various forms and arenas. The experience of a disconnection by the supplier is described as being especially humiliating. In Germany, a man in his thirties, who is a single parent of a two-and-a-half-year-old child, remembers the moment of the actual enforcement of a power disconnection: “That was a punch in the face, frankly spoken” (Franke, 2019: 60f.). He describes how he searched for help but had to struggle for several months without electricity in their home. Often, this experience is described as a loss of control, because the most basic things suddenly don't work. Your food goes bad in the fridge while you struggle with debt, you can't even wash your clothes by hand because the water is cold, you come home and want to switch on the light—an automatic move—but realize you will spend the evening in the dark as you search for candles without any light. You cannot comfort yourself or your family with a warm meal, or charge your phone in order to ask for help. People feel overburdened by the situation, and on top of the disconnection they feel incapable of managing. A woman in her fifties recalls “tears, sadness and helplessness” (Franke, 2019: 60f.).

When contacting institutions, be they energy suppliers or welfare authorities, people report experiences of disrespect and open humiliation. Feelings of inferiority are common among energy-poor people. A couple in Greece discuss their experience of an electricity disconnection, and at one point the woman mentions her husband's attempt to find a job and settle the bill: “[Dyonisis went] to the unemployment office to find a job. He told me that the girls there, they laugh! Not they laugh with him, but they laugh that he still hopes he can, that somebody can hire him, ok?” (Franke, 2019: 60f.) A man in Poland who lived through years of deprivation, including homelessness, remembers his contact with institutions like this: “During the interviews I was asked such questions that made me feel like a used toilet paper.” (man, Poland, interview by Malgorzata Dereniowska). A single mother in her thirties reports her experiences with welfare state institutions in Germany: “… this has simply been humiliating. Applications disappear [for social welfare] … it was awful. Then I was asked to go to that training, Women in Profession, or such a bullshit, where I felt like … well I am not stupid. I am getting upset again, sorry. But they do these things there, let's see how we open Word, how to create a document and save it and then we cook together for lunch. I could as well go to prison, there I would probably have a similar daily programme. I don't want to do something like that, but they force you to. … I find this is a bit dictatorship-like. It has nothing to do with free decisions and free life. And if you don't do it, they cut the money.”

Behind the conduct of these street level bureaucrats, there is a political discourse which emphasizes the self-responsibility of those in need, often depicted in the literature as “blaming the poor” for ending up in a state of deprivation (Dorey, 2010: 215; Greenbaum, 2015). This type of stigmatizing discourse can also occur in the field of energy poverty. In Germany, the left-wing party (Die Linke, opposition) keeps pushing in parliament for a ban on disconnections. However, the majority regularly votes against this proposal. Among the arguments is the claim that a policy like this would build a public welfare social security “hammock,” which seduces people to intentionally evade paying their bills. In the records of German parliamentary debate, a 2019 contribution from the Christian Democratic Party (CDU, in government) reads like this: “Studies have also shown that part of energy disconnections—and we have to talk about this as well—are due to an intentional misuse of the state's duties of primary care. Therefore, it is clear to me: a ban of power disconnections is a disincentive at the expense of the energy providers and the general public. Because those who say, “I don't pay my energy bill because I cannot or I don't want to,” they do that because of a disincentive …” (German Parliament, 2019: 15215). This very much reflects the long-term attitude of the UK's “fuel poverty” policy, as reported by Jenkins et al. (2016), where “policy-makers in England, Wales, and Scotland have only recently begun to recognize the specific needs of particular social groups—such as the elderly, the infirm, and the chronically ill—and their reliance on higher-than-average room temperatures… This shift counteracts a long-standing tendency to stereotype the “energy poor” and their “inefficient” use of scarce energy and monetary resources.” (Jenkins et al., 2016: 177). Here, we are looking at well-known clichés of paternalistic and neoliberal welfare state policies that distinguish between the “deserving” and the “non-deserving” poor (Katz, 2013; Bridges, 2016).

Shame, Loss of Self-Respect, Not Living up to One's Own Self-Image

The presence of shame has been documented in research on energy poverty, often describing the feelings of those who cannot afford to pay their bills (Meyer et al., 2018) or those avoiding social contact because of their cold, dark or damp homes. Longhurst and Hargreaves (2019: 7) offer the case of a UK man who lives in social isolation and self-imposed disconnection from other humans: “I don't ever speak, well I don't see no-one … I don't put lights on, no … the only thing what's going on now is the fridge … and the telly, because if I didn't have that I'd go loco.” (Longhurst and Hargreaves, 2019: 7). They also introduce the notion of embarrassment, giving the example of a woman who says, “I don't have anyone come round. I don't have friends over… no-one. I don't think I've had a friend round since about 3 years … I don't like the condensation [water condensing on the windows] and that is a big thing for me. It's embarrassing.” (Longhurst and Hargreaves, 2019) In an article on the living situations of energy-poor people in Austria, Brunner et al. (2017: 139) describe how they refrain from asking for help from institutions, but also from within their own networks because they feel ashamed. One woman cited expresses shame regarding her abilities as a parent: “It is embarrassing, it is disgraceful, if you cannot provide your own child with warm water.” (Brunner et al., 2017: 140). The study also depicts reduced social contacts due to shame, and the complete avoidance of heating and lighting in order to save money. Some who do invite friends over, do so with extra lighting and heating, to bolster the façade of normalcy (Brunner et al., 2017: 148).

In interviews conducted by our research team, we, too, found proof of energy poverty inducing a set of negative emotions like shame, stress, anxiety, and anger. The Greek couple introduced above reported that their relationship suffers from the financial trouble that led to the electricity and gas disconnection: “[if you have] financial problems […] you'll have, you know, fights […] because you're angry. […] And when you're angry, sometimes you find the easiest target is the guy close to you.” (Franke, 2019: 52.) People also point out the uneasy combination of being treated as not-quite-deserving citizens while authorities are reluctant to provide help. For instance, asked about job center experiences, another informant from Germany reports: “Oh, [they're] very bad. Really very bad. You got the feeling you are a second class human being. But help? No, they don't help.” The stigmatization and disrespect go along with a loss of self-respect. People feel ashamed of the situation, and so they try to hide it from friends, family and neighbors. For instance, the young father we interviewed said that he tried to avoid drawing attention to the situation. He opened up only to his parents, not wanting anyone else to know. He also recalls fearing that his child would unintentionally reveal the situation through kindergarten. For his child, this meant that no friends could come over to play.

A woman in her fifties recalls having tried to contact the welfare institutions to resolve an enforced electricity disconnection. In the contact, she experienced feelings of inferiority, gradually losing confidence in herself. She remembers how she started to see her struggle as a personal failure: “You always feel like you want something impossible. So, [you go] into this begging mode somehow. And you feel bad because you maybe think, “Why don't you manage alone? Why do you not get this done?” And, yes, one feels a bit like, actually, a loser.” (Franke, 2019: 52.). The single father also mentions self-doubt. His most troubling shame is being unable to raise his kid “normally,” which to him means cooking warm meals and having lighting. During the energy disconnection, he couldn't make hot cocoa for his child, a routine comfort they used to share, nor could he wash the dirty laundry after his son had played outside. Being able to wash one's clothing is included in the list of secondary capabilities (Day et al., 2016) that households are often deprived of when experiencing energy poverty. One mother in a family of five, who works part-time as a nurse on nightshifts while her husband has a low paid job in a different city, blames their difficulties with paying their bills on high housing and transportation costs. She said she hadn't bought new clothes for herself in 8 years, but what's even worse is not being able to provide a “normal childhood” for her kids, with holidays and the nice things other parents can afford. Thus, the benchmark for self-respect, leading a life according to one's own self-image, is dependent on society's sense of what a “normal” livelihood is. The normative self-image depends on what counts as decent for others, thus, how much energy one needs is a deeply relational issue.

Dependence on Family, Friends, and Institutions

Finally, can energy-poor people determine their own goals and develop the means to achieve them? From our literature review, we concluded that energy is among the means that help achieve decent living. Further, disconnection from energy causes multiple dependencies, since energy is a fundamental resource for participation and respected membership in society. The single father recalls how he had to turn to his parents for help, and how difficult this was as an adult: “… when the son comes home from kindergarten, soaking wet, dirty, maybe peed in his pants and he could not throw the pants in the washing nor provide a hot bath for the son” (Franke, 2019: 52.). Thus, he needed to visit his mother on weekends for things like laundry, warm meals, and charging his phone. In order to reduce these visits to a minimum, he used an external power bank and kept his phone usage to a minimum so the battery would live through to the next weekend. Dependence on one's parents in adulthood evokes different responses in different countries. In Germany, young people strive for independence at an early age, e.g., by moving out of their parents home and founding own households earlier than for example in Southern or Eastern European countries. Here, going back to your mother for household routines is rather unusual and can easily been seen as a sign of personal failure. We have several cases in Germany where asking family for help after a phase of independence is described as troublesome. A single mother, in school to escape low-paying jobs, reports how she broke off the relationship with her father over borrowing money. Longhurst and Hargreaves provide a similar example of a woman who said, “Even if I go to my Mum … and say, “Mum, can I borrow £20 for some electric?” I find that embarrassing, so I try not to put myself in that situation.” (Franke, 2019: 7).

Turning to institutions for help can lead to a perceived dependence on the good will of officials, or even complete powerlessness. Interviewees described feeling forced to obey what the officials demanded and agreeing to measures they found inappropriate, as in the prior example of the single mother who found herself in professional training she did not need. But she had to agree: “… if you don't do it, they cut the money.” A disabled woman in her fifties, relying on a wheelchair after an accident, and struggling with housing and utility costs after divorce, told us, “I experienced a lot of degradations. You are only worthy if you do something, if you work. Even if it is just a dull job, and you never had a book in your hand … people are judged by work. … It is the same everywhere, if you need something. With the health insurance, with the housing company: “what do you want again, now?”” In another interview, a woman described being unable to state her case for weeks after the disconnection was enforced: “They said they cannot do anything, you have to pay. … And you have no chance to even talk to the officers at all. … If you have no appointment you cannot go in at all, and as for telephone, you cannot call either. They just leave you standing there.” (our interview, 2019). A 40-year-old man told us about a gas disconnection due to his inability to afford the payment for his gas bill. In order to pay the gas bill and get reconnected, he went to the job center to ask for a loan. When asked by the interviewer about the mode of communication, he answered: “Top-down, paternalistic. They consider themselves better, they have a job, they can do with us what they want.” An example from France shows how digitalization complicates things, with bureaucratic procedures becoming even more distanced and insecure, with dependency increasing. In France, a 40-year-old single mother of four, who spends €176 of her €1100 monthly income on gas and electricity, describes her experience of applying for welfare support: “They gave me a code, but the code did not come in. It's too complicated. It's annoying. It does not work. And I am scared about taxes on the Internet. Because if the day [comes when] I can't pay the Internet anymore… how will I do it? Plus, here I am in front of a screen. Who can I say to “I can't do it'? There is no longer a relationship. This is also what is painful” (interview by Ute Dubois, published in Rexel Foundation Occurrence Healthcare, 2018).

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper intended to use a conceptual understanding of dignity to investigate non-material forms of deprivation in the lived experience of energy-poor households. While notions of dignity and decent living are often touched upon in the literature on energy poverty, material deprivation has been the dominant issue in studies on the struggles of households to afford energy services. We showed how a more structured understanding of dignity can systematically help shed light on the subjectively experienced deprivation of one's moral status in society, and one's dignity (Forst, 2011) —as opposed to one's socio-economic status. From philosophical writings, three concepts were chosen to operationalize dignity and interpret cases stemming from interviews within our research teams and those reported in the literature. As shown, violations occur in all three aspects of our concept of dignity, namely, respect, self-respect, and self-determination. We demonstrated that these aspects of dignity are lacking in the way the deprived citizens have been treated. We argued that the negative outcomes of this maltreatment are seen in the form of disrespect, humiliation, shame and stigma as well as dependence. Of course, given the limited data, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the overall scope of these dignity violations, but the analyzed material shows worrisome tendencies.

Energy-poor people depend on others and institutions, which then become the very sources of disrespect and feelings of inferiority. However, in order to regain self-determination with regard to power supply, people cannot turn away from welfare-institutions or energy providers or even from difficult family relations. This forced dependence on people and institutions means that one cannot avoid experiences of disrespect. This very likely causes more anger, anxiety and lower self-respect in countries like Germany, for instance, where there is no politicization of energy poverty. By politicization of energy we mean the current trend of framing the deficiencies of social policies in political terms and making them part of the social movements' agenda. Unlike in Spain, for example, where social movements and solidarity networks formed to provide mutual support and protest against disconnections (Herrero, 2018), energy-poor people in Germany live with the responsibilization of the individual rather than societal structures. People blame themselves for failing to manage well and bring up their kids “normally.” In such a context, an “upright gait” —as in Ernst Bloch's metaphorical description of dignity—is hard to achieve.

We want to emphasize the obvious relational nature of these dignity violations, thus agreeing with the recent emphasis on dignity as a relational issue in philosophical writings (e.g., Forst, 2011; Brandhorst and Weber-Guskar, 2017; Clark-Miller, 2017; Zylberman, 2018). A relational perspective attends to the fact that social phenomena emerge from the interrelation between actors and situations within specific contexts. We can see how subjectively experienced dignity violations relate to the standards of good living in society. The experience of shame described by interviewees over not being able to provide their children with a “normal” childhood illustrates this point accurately. Norms of “the good life” depend on wider norms in a given context, and people cannot simply escape these norms. Thus, analysis of energy poverty and energy deprivation needs to be contextual, from both a material and non-material perspective. It may contradict academic convention to measure and monitor energy poverty across contexts, but as we argue, in order to properly capture the complexities of energy poverty and deprivation, one needs to work with multiple perspectives and take the positionality of judgement into consideration. Borrowing Forst's (2011) notion of active dignity, which goes beyond basic provisions for life (passive dignity), an active understanding of non-material energy deprivations would emphasize that access to energy can be dignifying in one context and humiliating in another. To have active dignity in European societies means being a respected member of society, feeling this respect, and being able to turn it into self-worth. Most importantly, active dignity means the self-determination of one's own goals and the means to achieve them, rather than dependence on others. We already see this idea reflected in some energy poverty writings that use a capability lens, for instance in Day et al. (2016) notion of the secondary capabilities that form a bridge between Nussbaum's list of capabilities and a given societal context. While the list of primary capabilities resembles the notion of passive dignity more closely, the secondary capabilities link it to the energy services needed for respect in a given society. We would be happy to deepen such debate in further work.

Using Margalit (1996) ideas of a decent society, we also learn from the material under review that our societies are far from being “decent” given the experiences of energy-poor households. The interviews and material considered show how these households face humiliating experiences within their personal networks and in contact with institutions, experience feelings of inferiority and stigma as well as debilitating dependence, either in their social networks or through the “support” of institutions, where they often rely on the goodwill of frontline bureaucrats. This dependence is all the more humiliating with energy disconnections, where a sudden dependence is perceived as a significant drop in one's material and moral status. This is especially true in societies that haven't seen the politicization of energy poverty, often treating it as evidence of a person's inability to manage their lives. As the German political debate illustrates, politicians accuse people who are not able to pay their bills of cheating those who pay regularly (e.g., German Parliament, 2019: 15215). There's an opening here for research and thinking about persistent ideologies within the welfare state that lead to policies based on paternalistic notions of the deserving and non-deserving poor (Katz, 2013; Bridges, 2016). Additionally, the debate on “blaming the poor” can provide inspiration for the energy poverty and energy justice academic community in their critique of policies that blame the behavior of households and stereotype them as uninformed, careless, unwilling, and even cheating the welfare state.

In conclusion, dignity provides two new perspectives in energy justice research: a new analytic framework in normatively-oriented research (the social-philosophical literature enables the operationalization of dignity violated and dignity achieved), and a novel and complementary normative horizon for the development of energy policies. While concerns about energy justice have long driven researchers and practitioners to explore ways of measuring it, the dignity-based standpoint promises to create a more nuanced approach to the non-material aspects of energy distribution and consumption.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: data are qualitative in nature, comprising both interviews and documents.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

KG and ET elaborated the draft together in close cooperation. While the section Disrespected, Ashamed and Dependent: Households in Energy Poverty is mainly written by KG, all other sections were elaborated collectively, both contributing in equal shares. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The paper stems - among others - from collaborative work within COST ActionEuropean Energy Poverty: Agenda Co-Creation and Knowledge Innovation (ENGAGER, 2017–2021, CA16232) funded by European Cooperation in Science and Technology—www.cost.eu. The authors also wish to acknowledge the help of Leona Sandmann, Robert Franke, and Helene Oettel with empirical work. We thank Ute Dubois and Malgorzata Dereniowska for allowing us to use individual quotes from interviews they conducted.

Footnotes

2. ^We use fuel poverty and energy poverty interchangeably. For an introduction to the distinction between the terms in part of the debate see Bouzarovski and Petrova (2015).

References

Balachandra, P. (2012). Universal and sustainable access to modern energy services in rural India. An overview of policy-programmatic interventions and implications for sustainable development. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 92, 163–182.

Barnard, M., and Scholtz, W. (2013). Fiat lux! Deriving a right to energy from the African charter on human and people's rights. South Afr. Yearb. Int. Law 38, 49–66.

Biermann, P. (2016). How fuel poverty affects subjective well-being: panel evidence from Germany. Oldenburg Discussion Papers in Economics, No. V-395-16, 1-32.

Bilgiç, G. (2017). The measure and definition of access to energy systems by households and social effects of lack of modern energy access. EEE 5, 1–7. doi: 10.13189/eee.2017.050101

Boardman, B. (1991). Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth. London; New York, NY: Belhaven Press.

Bouzarovski, S. (2013). Energy poverty in the European union: landscapes of vulnerability. WENE 3, 276–289. doi: 10.1002/wene.89

Bouzarovski, S., and Petrova, S. (2015). A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: overcoming the energy poverty–fuel poverty binary. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 10, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.06.007

Brandhorst, M., and Weber-Guskar, E. (2017). Menschenwürde. Eine Philosophische Debatteüber Dimensionen ihrer Kontingenz (Human Dignity. A Philosophical Debate on Dimensions of it's Contingency). Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Bridges, K. M. (2016). The deserving poor, the undeserving poor, and class-based affirmative action. Emory Law J. 66:1049. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2824433

Brunner, K.-M., Christanell, A., and Mandl, S. (2017). “Energiearmut in Österreich: Erfahrungen, Umgangsweisen und Folgen (Energy poverty in Austria: Experiences, coping strategies, and consequences),” in Energie und soziale Ungleichheit. Zur Gesellschaftlichen Dimension der Energiewende in Deutschland und Europa (Energy and Social Inequality. On the Societal Dimension of the Energy Transition in Germany and Europe), ed K. Großmann, A. Schaffrin, and C. Smigiel (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 131–155. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-11723-8_5

Bulkeley, H., Luque-Ayala, A., and Silver, J. (2014). Housing and the (re)configuration of energy provision in Cape Town and São Paulo: making space for a progressive urban climate politics? Polit. Geogr. 40, 25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.02.003

Butler, D., and Sherriff, G. (2017). “It's normal to have damp”: using a qualitative psychological approach to analyse the lived experience of energy vulnerability among young adult households. Indoor Built Environ. 26, 964–979. doi: 10.1177/1420326X17708018

Chakravarty, S., and Tavoni, M. (2013). Energy poverty alleviation and climate change mitigation: is there a trade off? Energy Econ. 40, 67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2013.09.022

Clark-Miller, S. (2017). Reconsidering dignity relationally. Ethics Soc. Welfare 11, 108–121. doi: 10.1080/17496535.2017.1318411

Day, R., Walker, G., and Simcock, N. (2016). Conceptualising energy use and energy poverty using a capabilities framework. Energy Policy 93, 255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.019

Debes, R. (Eds.). (2017). Dignity. A History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.001.0001

Dorey, P. (2010). A poverty of imagination: blaming the poor for inequality. Polit. Q 81, 333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-923X.2010.02095.x

European Commission (2020). Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1563 on Energy Poverty. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2020/1563/oj

Fainstein, S. S. (2010). The Just City. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. doi: 10.7591/9780801460487

Forst, R. (2011). The ground of critique: on the concept of human dignity in social orders of justification. Philos. Soc. Criticism 37, 965–976. doi: 10.1177/0191453711416082

Franke, R. (2019). Stromsperren als Folge von Energiearmut in Griechenland und Deutschland. (Electricity disconnections as a consequence of energy poverty in Greece and Germany) (Master Thesis). Erfurt, DE: University of Applied Sciences Erfurt.

Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identity. The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. New York, NY: Farrar Straus and Giroux.

German Parliament (2019). Record of the German Parliamentary Debate, 25.10.2019, CDU. Available online at: https://dbtg.tv/fvid/7397557 (accessed March 25, 2021).

Gest, J. (2016). The New Minority. White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Greenbaum, S. D. (2015). Blaming the Poor: The Long Shadow of the Moynihan Report on Cruel Images About Poverty. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. doi: 10.36019/9780813574165

Habermas, J. (2010). The concept of human dignity and the realistic Utopia of human rights. Metaphilosophy 41, 464–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9973.2010.01648.x

Heffron, R. J., and McCauley, D. (2018). What is the “Just transition”? Geoforum 88, 74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.016

Herrero, S. T. (2018). From Subordination to Resistance and Solidarity: Transformative Citizen Action and Energy Vulnerability in Barcelona. IFoU 2018: Reframing Urban Resilience Implementation: Aligning Sustainability and Resilience.

Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in Their Own Land. Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York, NY: The New Press.

Hulme, J. (2012). “England: lessons from delivering decent homes and affordable warmth,” in Energy Efficiency in Housing Management. Policies and Practice in Eleven Countries, ed N. Nieboer, S. Tsenkova, V. Gruis, and A. van Hal (Hoboken: Taylor and Francis), 97–114.

Jacobson, N., Oliver, V., and Koch, A. (2009). An urban geography of dignity. Health Place 15, 695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.11.003

Jenkins, K., McCauley, D., Heffron, R., Stephan, H., and Rehner, R. (2016). Energy justice: a conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 11, 174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.10.004

Jenkins, K., Sovacool, B. K., and McCauley, D. (2018). Humanizing sociotechnical transitions through energy justice: an ethical framework for global transformative change. Energy Policy 117, 66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2018.02.036

Katz, M. B. (2013). The Undeserving Poor. America's Enduring Confrontation With Poverty. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kaufman, G. (1993). The Psychology of Shame: Theory and Treatment of Shame-Based Syndromes. London: Routledge.

Longhurst, N., and Hargreaves, T. (2019). Emotions and fuel poverty: the lived experience of social housing tenants in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 56, 199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.05.017

McCauley, D., Ramasar, V., Heffron, R. J., Sovacool, B. K., Mebratu, D., and Mundaca, L. (2019). Energy justice in the transition to low carbon energy systems: exploring key themes in interdisciplinary research. Appl. Energy 233–234, 916–921. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.005

Meyer, S., Laurence, H., Bart, D., Middlemiss, L., and Maréchal, K. (2018). Capturing the multifaceted nature of energy poverty: lessons from Belgium. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 40, 273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.01.017

Middlemiss, L., Ambrosio-Albalá, P., Emmel, N., Gillard, R., Gilbertson, J., Hargreaves, T., et al. (2019). Energy poverty and social relations: a capabilities approach. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 55, 227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.05.002

Middlemiss, L., and Gillard, R. (2015). Fuel poverty from the bottom-up: characterising household energy vulnerability through the lived experience of the fuel poor. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 6, 146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.02.001

Middlemiss, L., Gillard, R., Pellicer, V., and Straver, K. (2018). “Plugging the gap between energy policy and the lived experience of energy poverty: five principles for a multidisciplinary approach” in Advancing Energy Policy. Lessons on the Integration of Social Sciences and Humanities, ed. C. Foulds, and R. Robison (Basel: Springer International Publishing), 15–29. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-99097-2_2

Pachauri, S., and Spreng, D. (2011). Measuring and monitoring energy poverty. Energy Policy 39, 7497–7504. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2011.07.008

Pellegrini-Masini, G., Pirni, A., and Maran, S. (2020). Energy justice revisited: a critical review on the philosophical and political origins of equality. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 59:101310. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.101310

Rao, N. D., and Min, J. (2018). Decent living standards: material prerequisites for human wellbeing. Soc. Indic. Res. 138, 225–244. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1650-0

Rexel Foundation Occurrence Healthcare (2018). Interviews de Ménages en Précarité Énergétique. Available online at: https://www.rexelfoundation.com/sites/default/files/interviews_de_menages_en_precarite_energetique_occurence_fondation_rexel_mai_2018.pdf (accessed March 25, 2021).

Sayer, A. (2005). Class, moral worth and recognition. Sociology 39, 947–963. doi: 10.1177/0038038505058376

Sing-hang Ngai, J. (2012). Energy as a human right in armed conflict: a question of universal need, survival, and human dignity. Brooklyn J. Int. Law 37, 579–622.

Statman, D. (2000). Humiliation, dignity and self-respect. Philos. Psychol. 13, 523–540. doi: 10.1080/09515080020007643

Thomson, H., Snell, C., and Bouzarovski, S. (2017). Health, well-being and energy poverty in Europe: a comparative study of 32 European countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 1–20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060584

Tomkins, S. (1963). Affect Imagery Consciousness: Volume II: The Negative Affects. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Walker, G. (2009). Beyond distribution and proximity: exploring the multiple spatialities of environmental justice. Antipode 41, 614–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00691.x

Weber-Guskar, E. (2017). Menschenwürde: Kontingente Haltung statt absoluter Wert. (Human Dignity: Contingent Approach instead of Absolut Value) in Menschenwürde. Eine Philosophische Debatte über Dimensionen ihrer Kontingenz (Human Dignity. A Philosophical Debate on Dimensions of it's Contingency), eds M. Brandhorst, and E. Weber-Guskar (Berlin: Suhrkamp), 206–233.

Willand, N., and Horne, R. (2018). “They are grinding us into the ground” – The lived experience of (in)energy justice amongst low-income older households. Appl. Energy 226, 61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.05.079

Yoon, H., and Saurí, D. (2019). ‘No more thirst, cold, or darkness!” – Social movements, households, and the coproduction of knowledge on water and energy vulnerability in Barcelona, Spain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 58:101276. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.101276

Keywords: dignity, normativity, energy justice, energy poverty, respect, disconnections

Citation: Grossmann K and Trubina E (2021) How the Concept of Dignity Is Relevant to the Study of Energy Poverty and Energy Justice. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:644231. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.644231

Received: 20 December 2020; Accepted: 10 March 2021;

Published: 12 April 2021.

Edited by:

Neil Simcock, Liverpool John Moores University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Nathalie Ortar, UMR5593 Laboratoire Aménagement, Économie, Transport (LAET), FranceMarielle Feenstra, University of Twente, Netherlands

Copyright © 2021 Grossmann and Trubina. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katrin Grossmann, a2F0cmluLmdyb3NzbWFubkBmaC1lcmZ1cnQuZGU=

Katrin Grossmann

Katrin Grossmann Elena Trubina

Elena Trubina