- Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

This policy brief argues that due to the failure of local municipalities, political instability, and corruption, hazards act synergistically with unequal and complex power relationships to reproduce and disproportionately distribute hazardous landscapes, particularly in the low-income communities of South Africa. It argues that when municipal bureaucrats hide behind a façade of claiming to do something about hazards and the associated challenges they present for low-income communities, but in reality take no action, they reveal their “dangerous mindscapes” which have devastating effects on low-income communities. The author defines “dangerous mindscapes” as the deliberate and consistent insistence that municipal bureaucrats are distributing and will distribute basic services to everyone in South Africa. This consistent insistence is rooted in an ideological mantra that the government is committed to distribute basic services, but in order to justify their failings; they construct basic service provision as dependent on class and citizenship. This study adopted a qualitative research design, grounded on the descriptive phenomenological approach. The study covers the period between 2015 and 2019. Twenty-four (24) in-depth interviews were conducted in the greater Mangaung low-income communities. The brief explores and highlights the climate change-urbanization nexus as politically propelled with devastating spatiality outcomes, where low-income community residents of Mangaung are forced to navigate a hazardous landscape that forces them to “walk at their own risk” because when hailstorms come, the residents are exposed to human excreta from improvised toilets that runs inside their houses and on the streets.

Introduction

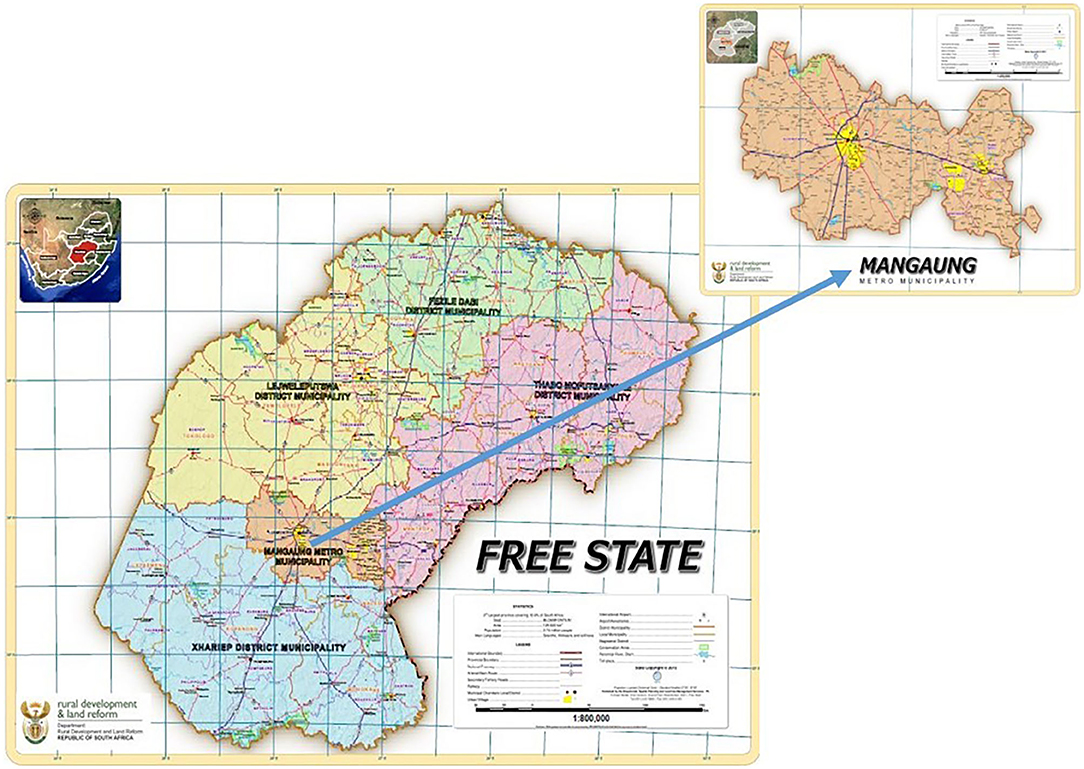

Leading to the collapse of local municipality-provided sanitation infrastructure such as public toilets and Ventilated Improved Pits (VIP) and other facilities, the crisis of inadequate sanitation provision has forced local communities to employ alternative strategies to access sanitation in South Africa. Their struggle to access this basic service is intensified when hailstorms come. The low-income communities of Mangaung (Figure 1) are therefore, exposed to human excreta that comes out of their improvised toilets and runs inside their houses and on the streets (Figure 2). Aware of how hailstorms and inadequately provided sanitation affect low-income communities, the local municipal bureaucrats1 choose to hid behind their ideological mantra that insists and claims “the government is committed to providing basic service to all,” but the reality is quite different. Consequently, the municipal bureaucrats disregard their responsibilities of ensuring safe and healthy environments as mandated by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa.

The main argument of this policy brief is that hazardous landscapes (Figure 3) are a product of unequal and complex power relationships that are disproportionally distributed through the unpreparedness of the municipal bureaucrats to handle hailstorms when they come and inadequate sanitation provision in low-income communities of Mangaung. Furthermore, the inadequate provision of sanitation in low-income communities of Mangaung, is a direct and continuing result of constructed spatialities of race and class, instituted by the colonial-cum-apartheid regimes and now perpetuated by the municipal bureaucrats (Bekker and Leildé, 2003; Atkinson, 2007; Watson, 2009; Neely and Samura, 2011). Often, during and after hailstorms, government interventions are reactive, substandard, and inconclusive, especially affecting low-income communities negatively (Bauer, 2000; Smith, 2004). These inactions reveal the “dangerous mindscapes” and blatant neglect by a retreating government that is controlled and manipulated by these local municipal bureaucrats. The author defines “dangerous mindscapes” as the deliberate and consistent insistence that municipal bureaucrats will distribute basic services to everyone in South Africa. These dangerous mindscapes are rooted in an ideological mantra that the government is committed to distribute basic services equally to all, but in order to justify their failings; they construct basic service provision as dependent on class and citizenship status (Mphambukeli, 2019).

This policy brief is part of a wider research project that advocates for the incorporation of social justice in planning within the context of Global South cities. After this introduction, the methodological considerations are outlined, followed by a brief discussion on the climate change-urbanization nexus in post-apartheid South Africa. Thereafter, a discussion on the politics of basic service delivery in post-apartheid South Africa will be presented. The experiences of how low-income communities of Mangaung navigate the dangerous landscapes during and after hailstorms are outlined and illustrated as a case study. The policy brief further provides actionable recommendations and concludes with the policy brief discussion.

Methodological Considerations

This study adopted a qualitative research design, grounded on the descriptive phenomenological approach. According to Creswell (2013), a phenomenological study describes the common meaning for several individuals of their lived experiences. The study covers the period between 2015 and 2019. Twenty-four (24) in-depth interviews with an average duration of 60 min each were conducted in the greater Mangaung low-income communities. The sample included local residents, ward councilors and officials from the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality. Ethical Clearance, Number UFS-HSD2015/0002, was obtained from the University of the Free State prior to conducting the study.

Climate Change-Urbanization Nexus in Post-Apartheid South Africa

The fact that climate change currently traverses the globe—albeit disproportionately felt at individual, societal and institutional levels and presents urban areas, in particular, with rising occurrences and intensity of water shortages, persistent drought, floods, storms, and increase in temperature—requires policy attention. This policy brief is unique in the discipline of urban and regional planning in that it recognizes, explores, and highlights the climate change-urbanization nexus as politically and economically propelled with devastating spatiality outcomes for low-income communities. It questions the complexities produced by the climate change-urbanization nexus, and situates the argument within the dangerous landscapes and mindscapes that are constructed by the political scape of South Africa. The role of planners, humanitarians, municipal bureaucrats, health professionals, the private sector, and other relevant critical stakeholders in facilitating the policy options that are realistic, context specific and actionable cannot be over emphasized.

The urbanization literature in South Africa articulates a historical angle of policies such as the Natives Land Act (1913) that controlled the movement and settlement of people (Mabin, 1992; Reintges, 1992; Todes et al., 2010). Furthermore, the Population Registration Act (1950) categorized all South Africans into a number of racial identities, and the Group Areas Act (1950) defined where each racial group should live (Mphambukeli, 2019). Even before apartheid, Africans were prohibited from owning private property (Feinberg, 1993; Kihato, 2013). Other discriminatory legislation includes the Immorality Amendment Act (1950) and the Suppression of Communism Act (1950) that built upon a long history of colonial intervention and dispossession of African land as a means of reducing Africans to mere laborers for the colonial-cum-apartheid economies (Mphambukeli, 2019).

Other literature on urbanization tends to focus on informal settlements and presents them as a problem resulting from uncontrolled or disorderly urbanization (Kihato and Napier, 2013, p. 92). Yet, little attention has been paid to how the climate change-urbanization nexus contributes to the vulnerability of low-income communities in South Africa. For instance, in 2016 the World Bank released a report on the “Impact of Rapid Urbanization and Climate Change on Durban's Environment” (eThekwini Municipality Newsflash, 2016), and in 2017, another report on “Greening Africa's Cities: Enhancing the relationship between urbanization, environmental assets and ecosystem services” (White et al., 2017). Both reports emphasized the impact of urbanization on the environment and are silent about how hazards, are constructed and produced through lack of planning, bureaucratic mechanisms, and the politics associated with them. The negative impacts of climate change on low-income communities when disasters hit, are not mentioned in these reports. This silence “blinds us to the ways in which ordinary urban dwellers respond to [inadequate and lawless] government frameworks and economic barriers” (Kihato and Napier, 2013, p. 93).

Politics of Basic Service Delivery in Post-Apartheid South Africa

The persistence of apartheid oppressive urban planning tools such as town planning ordinances and schemes 26 years into democracy has not assisted South Africa's transformation (Christopher, 1999, Mariotti and Fourie, 2014; Mphambukeli, 2019). The task of reconstructing, integrating, transforming and restructuring spatially segregated, highly fragmented, and dispersed urban societies has dismally failed (Donaldson, 2001). Politically constructed hazards are emerging where accountability for adequate basic service provision is assigned to negligent local municipal officials (Mufamadi, 2017; Reddy, 2016). These officials mostly lack the necessary skills and understanding of complex systems required for effective basic service delivery in post-apartheid South Africa (Eales, 2008, p. 1; Pithouse, 2018). However, this neglect is not a South African particularism, even in the Global North, municipalities are struggling (Heffer and Willoughby, 2017). Furthermore, since access to adequate basic services such as water, housing, sanitation, electricity and storm water drainage, is generally a complex issue, the politics of basic service delivery, along with violent protests, xenophobic attacks, and corruption, have become customary and continue to reproduce contestations and complexities embedded in power relationships within post-apartheid South Africa (Mphambukeli and Nel, 2018).

The most pressing challenge that requires actionable policy change is the failure of the state to tackle the climate change-urbanization nexus through adequate basic service provision. The state fails because of political instability, corruption, lack of necessary skills and adoptive systems. Indeed, high migration patterns, burgeoning of informal settlements at the periphery of cities, soaring unemployment rates, and poverty are some of the most intractable problems besetting the current South African urban political landscape (Pieterse, 2005, p. 139; Pithouse, 2008). The state failure, consequently, forces low-income communities to employ different local strategies such as digging pits using shovels for sanitation or collecting water from nearby communal taps to access basic services such as water, sanitation, electricity and storm water drainage when disasters hit (Mphambukeli, 2015).

Hailstorm and Human Excreta: Experience and Evidence From Low-Income Communities of Mangaung, South Africa

In October 2016, the greater part of the Mangaung area was inundated by hailstorms and floods, leading to the collapse of the inadequate state-provided basic services, such as public toilets, ventilated improved pit latrines and other facilities. Taken by surprise, many residents ran helter-skelter as toilets, filled and overflowing with water, made its way to homes, shops, restaurants, salons, and crèches. Streets were submerged with water filled with human feces. Caregivers, mothers, fathers, parents and guardians struggled with securing their properties as well as restraining their young ones from playing in the contaminated water. As the smell of the petrifying human feces diffused into the air, homes and streets that suffered the storms became apprehensive of diseases such as cholera and typhoid. Nearby homes not affected by the floods were also thrown into asphyxiating conditions (Aon South Africa, 2016; You, 2016). Thus, within the affected and unaffected areas nearby, there was great fear of impending disasters. During and after the floods, the water was contaminated with human excreta/feces, making it a toxic and hazardous landscape. It produced the potential for public health crises such as cholera, typhoid, diarrhea, malaria, and rashes. How people survived in this landscape is a mystery as this is a land of misery and sorrow, a land of calamities of frogs, toads, mosquitos, flies, fears, and ill-feelings. Instead of rejoicing when the rains come, low-income community residents now pray that it does not rain. On this hazardous landscape, you “walk at your own risk” as the situation forces children to cross dangerous flood areas, risking their lives and health in an environment of poverty that already compromises their immunity. Sometimes when it hails, children are washed off and killed, on their way to school.

Causes of Dangerous Landscapes in Mangaung

Institutional Failures

In reality, the government does not seem to deliver the necessary provisions and predictions that will help people to prepare for hailstorms. However, on paper it does. For instance, Section 14.1 of the Mangaung Disaster Management Plan (Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality, 2018) acknowledges, “disaster risk management is a national priority but it is institutionalized at the local sphere of government hence conditional grants must be disbursed to the City.” Thus, the municipal bureaucrats have somehow convinced themselves in their offices that hazards can be minimized. Their ideological positions demand that they sit in meetings and discuss the issues without genuinely joining the communities and building with them. From an interview with one of the top officials responsible for disaster management, it became clear that there is a level of blame casted to the low-income communities.

Lack of Political Will

The politicians' priorities in Mangaung are misplaced or skewed—with the same breath, they can host world-class multimillion festivals but appear powerless and lost when disasters hit local municipal areas, unable to support the low-income communities of Mangaung to deal with tragedies, thereby exposing the inability of government to make the necessary provisions or prevent disasters.

Government as an Accidental Distributor of Hazardous Landscapes

This policy brief tells the eloquent story of ways in which government have failed to properly plan for the climate change-urbanization nexus that is gradually overwhelming the African continent, especially post-apartheid South Africa. From 2015 to 2019, every time there was flooding in Mangaung and I visited the areas to inquire how the Mangaung municipal bureaucrats had assisted the low-income communities, the same answers were provided by the residents “Pula ya re sulafalla le ha re e hloka” meaning “rain brings us miseries even though we need it” in Sesotho.

Actionable Recommendations

Social justice in planning is presented as an arching point in bringing the people out of the dangerous landscapes. I use the example of access to adequate sanitation that has the potential to reduce vulnerability of low-income communities when hailstorms hit.

Recommendation 1: Effecting Attitudinal Change

Both government and ordinary people must be ready for attitudinal change that will influence values, processes, and practices toward access to sanitation. Municipal bureaucrats must be willing to take implementable actions.

Government: The extent of the problems associated with sanitation in urban areas is still huge. In South Africa, water-borne sewerage systems are considered to provide the highest level of sanitation. Yet, it is the most unsustainable system in a water stressed country and a shaky global climate change environment. Hence, they need to admit that they have failed to provide adequate sanitation that prepares and prevent negative impacts of hailstorms that ends up mixing with human excreta, on low-income communities. Only when the municipal bureaucrats' attitudes have changed , can an understanding of how their ideological insistence that they are doing something about hazards when they are not, be improved.

General public: Regrettably, much of the world's population, particularly in developing countries, remain without access to adequate methods to dispose of human excreta. This is the case in low-income communities of Mangaung, where residents are forced to use plastic bags and buckets to dispose of human excreta at open streams near their residential areas. These actions are problematic when hailstorms hit. However, some local residents who are impacted negatively by the inadequate sanitation delivery crisis, in and through formal local government processes, employ alternative strategies to access sanitation. For instance, those residents who can afford, hire tractors to dig deeper holes as they improvise on accessing waterborne free sanitation. If the general public is willing to learn from these improvised access to sanitation strategies, can develop resilience when hailstorms hit.

Recommendation 2: Developing Cultural Capital

There is a need to develop cultural capital. Government must understand and document informal coping strategies employed by the low-income community residents when disasters hit, and this will allow them to accumulate situated or contextualized community-based knowledge. In short, the municipal bureaucrats must leave their offices, join local constituencies, and build together with them. Through dialogue and fair representation, they should link with local residents in low-income communities.

Recommendation 3: Mapping the Shifting Hazardous Landscapes of Mangaung

To make room for people to know where and when a tragedy will strike and not forcing people to be spectators of disasters that affect their lives, the Mangaung municipality should identify flooding hotspots and ask themselves which kinds of technologies can be employed to manage disasters when they strike? In this way, they will not be stuck with non-implementable policies that do not yield performance. In addition, the government should ensure that a supportive system is in place during the construction of houses in low-income communities, especially in informal settlements. Through a piece by piece scaling up process, strategic spatial planning can be a useful tool. For instance, municipalities must provide for everyday needs and uses for water and sanitation. However, this recommendation should be considered along with the mapping of the rate of urbanization taking place in Mangaung. This mapping should be realistic and not just based on data from Statistics South Africa.

Recommendation 4: Co-production Mechanism

The emerging communities in low-income communities indicate a strong willingness to employ sanitation technologies that promote water-free sewerage. Therefore, through co-production. a reconceptualization of access to sanitation and storm water drainage systems is urgently needed in Mangaung where all critical stakeholders, including local people and the private sector come together to seek solutions.

Conclusion

What then are the implications of the produced politically constructed hazardous landscapes on the lived experiences of the low-income communities for urban planners, humanitarians, municipality bureaucrats, health professionals and other relevant stakeholders? This policy brief has argued that the government is dismally failing in protecting the low-income communities of Mangaung against hailstorms when they do not adequately provide access to sanitation and prepare in advance for hailstorms. An actionable climate change-urbanization nexus policy is therefore urgently needed in Mangaung South Africa. Through the implementation of this proposed policy, there is potential to build holistic resilience against hazards in South Africa. The policy further suggests that a systematized transdisciplinary lens be adopted when developing the climate change-urbanization nexus policy. This means the involvement of multidisciplinary stakeholders, professionals and low-income communities in the process of developing the policy must be prioritized. In this way, all critical stakeholder voices will inform the policy.

Author Contributions

The author developed and executed the research including data collection, analysis, and write up the policy brief.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation goes to the Volkswagen Foundation and the University of Hanover, Germany for awarding me a travel grant in November 2017, where my work was first presented at the Dangerous Landscapes, Herrenhausen Conference, Hanover, Germany.

Footnote

1. ^Municipal bureaucrats within the context of this policy brief are primarily black and white middleclass elites who now occupy positions of power within the local municipalities of South Africa. They seem to be detached from the social and material world of the poor.

References

Aon South Africa (2016). News Release. Bloemfontein Battered by Hailstorms. Available online at: https://aon.co.za/newsarticle81.aspx

Atkinson, D. (2007). “Taking to the streets: has developmental local government failed in South Africa?,” in State of the Nation: South Africa, eds S. Buhlungi, J. Daniel, R. Southall, and J. Lutchman (Cape Town: HSRC Press), 53–77.

Bauer, C. (2000). “Public sector corruption and its control in South Africa,” in Corruption and Development in Africa, eds K. R. Hope and B. C. Chikulo (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 218–233. doi: 10.1057/9780333982440_12

Bekker, S., and Leildé, A. (2003). Residents' perceptions of developmental local government: exit, voice and loyalty in South African towns. Politeia 22, 144–165.

Christopher, A. J. (1999). Towards the post-apartheid city. L'Espace géographique 28, 300–308. doi: 10.3406/spgeo.1999.1272

Collin, M. M. (2017). An investigation into the prevalence of unethical behaviour in a South African municipality: a case of Vhembe district municipality (Doctoral thesis), University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Donaldson, R. (2001). A model for South African urban development in the 21st century? In ‘Meeting the Transport Challenges in Southern Africa’, 20th South African Transport Conference South Africa, 16–20 July 2001. Conference Planners Conference Papers.

Eales, K. (2008). “Partnerships for sanitation for the urban poor: is it time to shift paradigm?,” in IRC Symposium: Sanitation for the Urban Poor Partnerships and Governance (Delft).

eThekwini Municipality Newsflash (2016). World Bank Releases Report of impact of Rapid Urbanisation and Climate Change on Durban's Environment. Available online at: http://www.durban.gov.za/Resource_Centre/Press_Releases/Pages/World-Bank-Releases-Report-of-

Impact-of-Rapid-Urbanisation-and-Climate-Chane-on-Durban%E2%80%99s-Environment.aspx

Feinberg, H. M. (1993). The 1913 Natives Land Act in South Africa: politics, race, and segregation in the early 20th century. Int. J. Afr. Hist. Stud. 26, 65–109. doi: 10.2307/219187

Heffer, T., and Willoughby, T. (2017). A count of coping strategies: a longitudinal study investigating an alternative method to understanding coping and adjustment. PLoS ONE 12:e0186057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186057

Kihato, C. W., and Napier, M. (2013). “Choices and decisions: locating the poor in urban,” in Trading Places: Accessing Land in African Cities, ed M. Napier, S. Berrisford, C.W. Kihato, R. McGaffin, and L. Royston (Somerset West: African Minds for Urban LandMark), 91–112.

Kihato, C. W. (2013). Beyond bricks and mortar: South Africa's low-cost housing program 18 years after democracy. Poverty Race. 22:1.

Mabin, A. (1992). “Dispossession, exploitation and struggle: an historical overview of South African urbanisation,” in The Apartheid City and Beyond, ed D. M. Smith (London: Routledge), 13–24.

Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality (2018). Disaster Risk Management Plan. MMM Disaster Risk Management Centre, Bloemfontein. Available online at: http://www.mangaung.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/16-Council-59.1-IDP-2019-2020-ANNEXURE-M-Disaster-Management-Plan.pdf

Mariotti, M., and Fourie, J. (2014). The economics of apartheid: an introduction. Econ. Hist. Dev. Reg. 29, 113–125. doi: 10.1080/20780389.2014.958298

Mphambukeli, T. N. (2015). Exploring the strategies employed by the greater Grasland community, Mangaung in accessing basic services (Doctoral thesis), University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Mphambukeli, T. N. (2019). “Apartheid,” The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies. New Jersey, NJ: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118568446.eurs0437

Mphambukeli, T. N., and Nel, V. (2018). “Migration, marginalisation and oppression in Mangaung, South Africa,” in Crisis, Identity and Migration in Post-Colonial Southern Africa: Advances in African Economic, Social and Political Development, eds H. Magidimisha, N. Khalema, L. Chipungu, T. Chirimambowa, and T. Chimedza (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-59235-0_9

Neely, B., and Samura, M. (2011). Social geographies of race: connecting race and space. Ethnic Racial Stud. 34, 1933–1952. doi: 10.80/01419870.2011.559262

Pieterse, E. (2005). “At the limits of possibility: Working notes on a relational model of urban politics,”. In Urban Africa: Changing Contours of Survival in theCcity, eds A. Simone, and A. Abouhani (London: Zed Books), 138–170.

Pithouse, R. (2008). A politics of the poor shack dwellers' struggles in Durban. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 43, 63–94. doi: 10.1177/0021909607085588

Pithouse, R. M. (2018). Forging new political identities in the shanty towns of Durban, South Africa. Hist. Mater. 26, 178–197. doi: 10.1163/1569206X-00001644

Reddy, P. S. (2016). The politics of service delivery in South Africa: the local government sphere in context. J. Transdicipl. Res. S Afr. 12:a337. doi: 10.4102/td.v12i1.337

Reintges, C. (1992). “Urban (mis)management? A case study of the effects of orderly urbanization on Duncan Village,” in The Apartheid City and Beyond: Urbanisation and Social Change in South Africa, ed D. Smith (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press), 99–109.

Smith, D. (2004). Social justice and the (South African) city: retrospect and prospect. South Afr. Geogr. J. 86, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/03736245.2004.9713801

Todes, A., Kok, P., Wentzel, M., van Zyl, J., and Cross, C. (2010). Contemporary South African urbanisation dynamics. Urban Forum 21, 331–348. doi: 10.1007/s12132-010-9094-5

Watson, V. (2009). ‘The planned city sweeps the poor away…': urban planning and 21st century urbanisation. Prog. Plann. 72, 151–193. doi: 10.1016/j.progress.2009.06.002

White, R., Turpie, J., and Letley, G. (2017). Greening Africa's Cities: Enhancing the Relationship between Urbanization, Environmental Assets and Ecosystem Services. Urbanization, the Environment and Green Urban Development in Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/26730/P148662%20Greening%20Africa%27s%20Cities_web.pdf

You (2016). In Pictures: Freak Hailstorm Causes Chaos in Bloem, News24. Available online at: https://www.news24.com/You/Archive/in-pictures-freak-hailstorm-causes-chaos-in-bloem-20170728 (accessed October 21, 2016).

Keywords: human excreta, hazardous landscapes, low-income communities, post-apartheid South Africa, dangerous mindscapes, climate change-urbanization nexus, human settlements, urban planning

Citation: Mphambukeli TN (2020) Hailstorm and Human Excreta: Navigating the Hazardous Landscapes in Low-Income Communities in Mangaung, South Africa. Front. Sustain. Cities 2:523891. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2020.523891

Received: 31 December 2019; Accepted: 16 October 2020;

Published: 10 December 2020.

Edited by:

Drew Michanowicz, Harvard University, United StatesReviewed by:

Terri-Ann Berry, Unitec Institute of Technology, New ZealandDickson Wilson Lwetoijera, Ifakara Health Institute, Tanzania

Copyright © 2020 Mphambukeli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thulisile N. Mphambukeli, TXBoYW1idWtlbGlUQHVmcy5hYy56YQ==

Thulisile N. Mphambukeli

Thulisile N. Mphambukeli