94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

COMMUNITY CASE STUDY article

Front. Sustain., 25 September 2024

Sec. Resilience

Volume 5 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2024.1461787

This article is part of the Research TopicUN International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Indigenous Peoples and Climate ResilienceView all 8 articles

Sarah Barger1*

Sarah Barger1* Mehana Blaich Vaughan1,2

Mehana Blaich Vaughan1,2 Christina Aiu1

Christina Aiu1 Malia K. H. Akutagawa1,3,4

Malia K. H. Akutagawa1,3,4 Elif C. Beall1

Elif C. Beall1 Jennifer Luck1

Jennifer Luck1 Dominique Cordy1,5

Dominique Cordy1,5 Julie Maldonado6

Julie Maldonado6This community case study explores how Kīpuka Kuleana, a Native Hawaiian women-led community-based land trust, revitalizes relationships between people and ʻāina (lands and waters) to perpetuate cultural practices that build climate resilience in Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi. We demonstrate that ancestral land protection is foundational to climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts on Kauaʻi, an isolated rural island in the Pacific Ocean increasingly vulnerable to flooding and landslides, sea level rise, and other climate-related impacts. Kīpuka Kuleana strives to keep kupa ʻāina ʻohana (long-time families)—the anchors of community who care for, teach from, and maintain balance in their fragile environments—rooted to their homes amidst increasing gentrification, land dispossession, and climate-related disasters. Through our interwoven programs, we return lands to communities and communities to lands, a reciprocal process known as ʻāina hoʻi, to restore access to ʻāina for collective caretaking, place-based education, and spiritual rejuvenation. Our land trust partners with Indigenous and allied groups in Hawaiʻi, Louisiana, California and Borikén (Puerto Rico) to share learnings tied to land protection, disaster resilience, adaptation, and rematriation, or the restoration of relationships between Indigenous people and ancestral lands. We offer some of those lessons to illustrate how Indigenous-led community-based land trusts and stewardship efforts forge new possibilities for adapting in place and cultivating more connected, resilient ecosystems stewarded under Indigenous leadership, in alignment with the “Land Back” movement.

“When we say Land Back, we also mean Relations Back.”—Mike Gouldhawke, âpihtawikosisân (Métis-Cree) writer and community organizer (Gouldhawke, 2020).

In the United States and around the world, Indigenous communities are adapting to intensifying impacts of climate change that threaten their lifeways, sovereignty, and connections to place. Contemporary Indigenous adaptation extends long histories of evolving with ecological changes, guided by reciprocal relationships between people and place, long-term observations of changes in environment, and collective actions to care for and protect lands and waters (Vaughan, 2018; Harangody et al., 2022; Ford et al., 2020). Over centuries of violent settler colonialism and industrialization, Indigenous communities have endured forced removal and dislocation from their homelands (Whyte, 2017) and systemic assimilation efforts to erase their identities, self-determination, and ways of life (Hibbard, 2021). Indigenous peoples in the U.S. have lost 98.9% of their ancestral homelands from colonization, and 42.1% of Tribes lack a federally or state recognized Tribal land base today (Farrell et al., 2021). The same colonial, capitalistic forces that displace Indigenous communities and ravage ecosystems—for example, through massive deforestation and fossil fuel extraction—also drive anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change (Whyte, 2017; Pasternak and King, 2019). Further, “green energy” solutions, such as solar panels and electric batteries, depend on extraction of lithium and other metals, and more than half of these global mining projects occur on or near Indigenous lands (Simon, 2024; Owen et al., 2023). Indigenous peoples are disproportionately affected by climate change as they adapt in marginal environments (Thomas et al., 2019) and face vulnerabilities to their health, food security, well-being, and livelihoods (Farrell et al., 2021), all intricately tied to land.

Yet, Indigenous peoples continue to resist the physical and spiritual separation of their communities from their lands and associated lifeways (Greenwood and Lindsay, 2019). Across generations, Indigenous communities have perpetuated cultural practices—such as fishing, gathering, and cultural burning—along with place-based knowledges that offer solutions for adaptation in our global climate crisis (Maldonado and Middleton, 2022). Their relationships to place reflect long-standing guardianship and stewardship of lands and waters, which cultivate local biodiversity and resilience (Brondizio et al., 2019; Diver et al., 2024; Fernández-Llamazares et al., 2021). Indigenous land defenders and water protectors work tirelessly on the frontlines to combat harmful actions by multinational corporations against their people and the environment (Whyte, 2019; Oishi, 2022). According to a 2021 report, Indigenous campaigns of resistance over the past decade have “stopped or delayed greenhouse gas pollution equivalent to at least one-quarter of annual U.S. and Canadian emissions” (Oil Change International, 2021).

One example of Indigenous-led organizing at the nexus of sovereignty, stewardship, and climate change adaptation is the “Land Back” movement. The Land Back movement “addresses the root pain of colonization—the theft of Indigenous lands, alienation of lands for resource extraction, the violence and genocide committed against Indigenous peoples for statehood and capitalism, and the hundreds of years of devastating aftereffects” (Pieratos et al., 2021). The return of Indigenous lands is a unifying call in the movement, echoed across the U.S. (Racehorse and Hohag, 2023), Canada (Pasternak and King, 2019), Aotearoa (Buchanan, 2022), Costa Rica (Garcia and Pastrana, 2022), Ecuador (Wilkins, 2023), South Africa (McKenzie and Swails, 2018) and beyond. Land Back works simultaneously within and against a system of western, capitalistic property ownership, as articulated by Maskoke leader Marcus Briggs-Cloud:

“The grammar of our Maskoke language literally constrains our ability to articulate ownership of and extractive economic relationships to land. We have to code switch to English to speak of those ways. So if we didn’t own it in the first place, it’s hard to talk about getting land back. I think it’s better to put it in terms of returning land to the traditional stewards to fulfill their inherent covenants to be caretakers of a particular place, per their own canon of stories” (Thompson, 2020).

One way that land is returning to Indigenous hands is through rematriation, which aims to “restore sacred relationships between Indigenous people and our ancestral land” and “[honor] our matrilineal societies…in opposition of patriarchal violence and dynamics” (Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, n.d.). Indigenous communities utilize different strategies to rematriate lands, such as: buying back ancestral lands, accepting land donations, securing rights to access and steward land, enforcing historic treaty agreements through legal action, and co-managing lands with other entities (Sustainable Economies Law Center, 2023). In particular, community-based land trust (CLT) models, which serve a variety of functions from land conservation to provision of housing, offer possibilities in the Land Back movement.

This case study focuses on a Native Hawaiian women-led community-based land trust on the island of Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi named Kīpuka Kuleana. The organization protects ancestral lands, while facilitating community stewardship and connection to place and supporting climate adaptation, through four interwoven programs: ʻohana outreach and support, policy and land protection, research and education, and stewardship. In the discussion section ending this paper, we connect Kīpuka Kuleana’s work to rematriation efforts by Indigenous and allied partners around the U.S. who are also applying land trust frameworks and stewardship practices to restore health and adaptive capacity in their communities.

“If you lose a place, you lose everything associated with that place, the lessons it could teach you.”—Native Hawaiian cultural practitioner, Kauaʻi, HI (Vaughan, 2018).

There is no pono (balanced and just), sustainable future for Hawaiian communities without ʻāina. In ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language), ʻāina translates to “that which feeds,” or lands and waters (Wight, 2005). ʻĀina embodies the reciprocal relationships cultivated with care between people and place across generations. These sustained connections to ʻāina offer physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional nourishment (Andrade, 2008) to kupa ʻāina ʻohana (people descended from and enduring in place), who in turn care for and pass down ʻike (knowledge) about specific ʻāina. Long-time families in Hawaiʻi perpetuate important cultural practices that build climate resilience and pilina (connection) to place—for example, growing and harvesting traditional foods like kalo (taro) and ʻulu (breadfruit) that provide sustenance, sequester carbon (Yang et al., 2022), and shape identity and kinship to place (Bremer et al., 2018). Taro is grown in irrigated terraces, an example of Hawaiian agricultural practice which also provides restoration and maintenance of streams and wetlands, trapping flood waters and filtering sediment, while buffering against salt water intrusion from sea level rise (Winter et al., 2018; Bremer et al., 2018). The ability for ʻohana to access, steward, and make community-based decisions about ʻāina from mauka (mountain) to makai (sea) is fundamental to thriving ahupuaʻa (traditional land division from mountain to sea) in Hawaiʻi, which faces intensifying impacts linked to climate change including hurricanes, tsunamis, floods, seasonal high waves, and sea level rise (Courtney et al., 2019).

Ua mau ke ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono: “The sovereignty of the Kingdom continues because we are righteous”—King Kamehameha III, 1843.

Hawaiian identity is rooted in rights and responsibilities to care for specific ʻāina, our kuleana. Kuleana is the same word for Hawaiian Kingdom lands that were handed down by generations of families because they were kept momona (productive and feeding people) (Pukui and Elbert, 1986). ‘Āina in Hawai’i was entrusted to community as the source of all life and a direct connection to kūpuna (ancestors) and akua (gods), never to be owned or coveted (Kameʻeleihiwa, 1992). However, waves of settler colonialism ushered in western values of capitalistic, extractive relationships with ʻāina across Hawaiʻi, threatening the subsistence-based lifestyles of Hawaiian communities. Between 1820 and 1850, American and European settlers pursuing agricultural ventures in Hawai’i pressured King Kamehameha III to introduce the concept of land title, which was codified during the Great Māhele of 1845 and the Kuleana Act of 1850 (Garovoy, 2005). Makaʻāinana (Native Hawaiian tenants) had to overcome obstacles, such as surveying land and proving historical tenure, to make a land claim and receive a kuleana award of a quarter-acre house lot and cultivated ʻāina, such as loʻi kalo (taro patch) or salt pans (Vaughan, 2018). Only 7,500 makaʻāinana received kuleana awards, a combined 28,600 acres that accounted for less than 1% of the Kingdom lands (Garovoy, 2005). As American business interests infiltrated Hawaiian governance and aided the United States’ illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, non-Hawaiians began acquiring government lands for private profit (Preza, 2010).

However, long-time ʻohana fought to maintain their kuleana to place, perpetuating genealogy, moʻolelo (story, history), cultural practices, and knowledge through protection of and care for ʻāina. For example, in the 1870s, Hawaiian communities came together to form hui kūʻai ʻāina (land-buying associations) to buy back lands not awarded to makaʻāinana (Andrade, 2008). Similar to a community land trust structure, hui members held land “in common” and participated in collective decision-making about resource management to protect and sustain ‘āina (Vaughan, 2018). A hui’s written constitution usually created protections to keep land within the hui, such as requiring members to sell their shares back to the hui if they desired to leave (Roversi, 2012). On Kauaʻi, hui kūʻai ʻāina bought back four ahupuaʻa (Vaughan, 2018). Some hui endured a century after the Great Māhele until largely dissolved through partition lawsuits (Vaughan, 2018; Roversi, 2012). However, for example, much of the ahupuaʻa of Hāʻena still remains in conservation and community management due to collective actions of ʻohana within the hui, past and present.

“We cannot compete with billionaires. We’re just simple people. It’s too much…pretty soon we lose our homes and everything we work for. We cannot give anything to our grandchildren because we have to sell because…we cannot afford to pay the taxes. So what little we save, hopefully for our children, it’ll all be gone.”—Wanini community member, Kauaʻi, HI (Vaughan et al., 2019).

The most recent wave of settler colonialism in Hawaiʻi is driven by increasingly wealthy non-local landowners and investors, whose insatiable appetite for buying land and developing luxury homes in Hawaiʻi prices out and displaces local families (Horton, 2024). Hawaiʻi accommodates over 9 million visitors each year (State of Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism (DBEDT), 2022). Hawaiʻi’s tourism has become tied to real estate, with visitors coming not only for vacation and recreation but also to invest in timeshares and second (third, fourth, or seventh) homes. Hawaiʻi has become “arguably the singular most desirable locale for the wealthy” (Reynolds, 2021). Because anyone can buy real estate in Hawaiʻi, the high global demand for land on Hawaiʻi drives rapidly increasing land values. Thirty seven billionaires own 218,000 acres of land on Hawaiʻi’s six largest islands, constituting 11% of non-government owned land (Liu and Hunter-Hart, 2024). Celebrities and Silicon Valley elite flock to the quiet island of Kauaʻi, building sprawling luxury compounds that insulate them from community and encroach upon natural habitat and local stewardship. During the COVID-19 pandemic, an influx of new landowners and remote workers seeking a safe haven on Kauaʻi drove a 57% increase in median house prices between November 2020 and November 2021 (The Associated Press, 2022). In August 2023, the median price of a single-family residence on Kauaʻi was $1,800,000, an 88% increase from the previous year (Haupt, 2023). One in eight homes on Kauaʻi sits vacant, purchased as a luxury home, vacation rental, or investment (The Associated Press, 2022). According to research by Stanford University students and Kīpuka Kuleana, non-local landowners on Kauaʻi primarily live in northern California (Bay Area), southern California (Los Angeles, San Diego), Honolulu, Seattle, and Denver—all places with direct flights to Kauaʻi (Trepte and Klink, 2021).

Given the high cost of living, lack of affordable housing, and limited job opportunities outside of tourism and service industries, many local community members are being forced to leave the island. Long-time families struggle to keep their homes, shouldering the burden of rising property taxes, inflated rents, and mounting pressure to sell their lands (Vaughan, 2018). In 2023, only 20 ʻohana on Kauaʻi received the kuleana tax exemption, a tax relief option for families holding ancestral ʻāina traced to kuleana awards from the Great Māhele. As large area landowners and developers target ancestral lands through quiet title and partition actions, families incur expensive legal costs to protect their lands. The privatization of ʻāina through luxury home development, gated communities, and fenced properties impinges on cultural practices by restricting access to fishing, gathering, and community areas, as well as significant viewpoints and burial grounds. These impacts also erode community connectedness and collective capacity to adapt to more frequent climate-related disasters on Kauaʻi.

“This is our piko. This is where we come to rejuvenate and get away from the hustle and bustle of work. This is the one place you can come and reconnect. My grandmother’s ashes are in this ocean here. Many of our family are here.”—Kalihiwai community member, Kauaʻi, HI (Vaughan, 2018).

From 2014 to 2016, one of Kīpuka Kuleana’s founders Dr. Mehana Blaich Vaughan and her students interviewed 40 elders and community members on the north shore of Kauaʻi to chronicle changes in the island’s physical, cultural, and economic landscapes and the enduring resilience of ʻohana who care for ʻāina. ʻOhana spoke of the abundance from the land and sea (e.g., kalo, vegetables, fish) shared across community, as well as the irrevocable damage to reef and coastal resources from overfishing, overtourism, and visitor industry-related developments such as golf courses and water diversions (Vaughan et al., 2019). Families also shared how difficult it was to keep ancestral lands within their ʻohana due to rising property values, taxes, encroachment, and legal actions. In response, Vaughan and three other women rooted on Kauaʻi (Jennifer Luck, Dominique Cordy, Tina Aiu) organized a workshop in 2016 for 20 community members working to keep their family lands. They invited attorneys, researchers, educators, government agency representatives, and community members to offer manaʻo (insights) and resources for tackling land issues. Although conservation land trusts across Hawaiʻi were protecting and managing lands for public use, none were specifically addressing the protection of ancestral lands and the challenges of fractional ownership across large ʻohana. Listening to the struggles of the families who attended, and finding limited assistance available from existing organizations, led the four women to found Kīpuka Kuleana, which obtained 501(c)(3) nonprofit status in January 2018.

Kīpuka Kuleana is a community-based land trust dedicated to perpetuating kuleana, ahupuaʻa-based natural resource management and connection to place through protection of cultural landscapes and family lands on Kauaʻi (Kīpuka Kuleana, 2024). We are a Native Hawaiian women-led organization guided by a volunteer board of directors, ʻohana advisors, two staff, and a research consultant. Our vision is that kupa ‘āina ‘ohana (long-time families) continue to thrive in, share the history and practices of, and care for every ahupuaʻa on Kauaʻi. The word kīpuka refers to a change of form, such as a calm place in a high sea, or a seed bank that creates vegetation within a lava flow (Pukui and Elbert, 1986). We work to grow kīpuka—places of community caretaking and cultural restoration—grounded in kuleana, within every ahupuaʻa on Kauaʻi. Aligned with the Land Back movement, we strive to return lands to communities and communities to lands, a reciprocal process known as ʻāina hoʻi (land returning). We partner with ʻohana, community members, nonprofit organizations, policymakers, government agencies, and Indigenous and allied groups to seed land return and to hold land in trust, ensuring that communities can collectively care for ʻāina and that families can always return to their piko (center). Our land protection work supports climate adaptation and resilience through four interwoven programs: Kākoʻo (ʻOhana Outreach and Support), Hoʻomalu (Policy and Land Protection), Aʻo (Research and Education), and Mālama (Stewardship).

Through tailored assistance and educational workshops, our nonprofit connects ʻohana with resources to keep and care for ancestral ʻāina that sustains community. To date, our workshops have supported over 300 community members, and our team has provided ongoing assistance to 75 ʻohana. Through moʻokūʻauhau (genealogy) workshops guided by volunteer genealogists, we offer foundational knowledge about ʻohana ancestry and help families research their land title and register iwi kūpuna (burials) to protect their loved ones. We provide trusted referrals for mediation and ho‘oponopono, a traditional Hawaiian practice that can help guide ʻohana through discussions to find pono, heal, and articulate goals and vision for their ʻohana ʻāina. Our legal partners help ʻohana set up estate and trust plans for long-term land protection and navigate quiet title and partition lawsuits aiming to force the sale of land. We work with families to identify conservation strategies that allow ʻohana to share, mālama (care for), and teach from their land, such as cultural conservation easements, partnership with a conservation buyer, and stewardship and access agreements. As ʻohana learn about and apply different land protection tools, they share what they learn and help other community members in similar situations.

Kīpuka Kuleana works to expand ancestral land protection through county and state tax relief policies and mapping of vulnerable lands using foreclosure data and community tips to prevent speculative development. We strive to restore ancestral community-based stewardship models, drawing inspiration from hui kūʻia ʻāina (land buying associations) and community-led efforts, such as the Hāʻena Community Based Subsistence Fishing Area, in which traditional fishing practices guide contemporary coastal use laws (Vaughan, 2018). We raise private and public funds to acquire and hold lands to revive community caretaking of ʻāina, cultural restoration, and ʻohana connections to place. As a land trust, we can implement tools like long-term leases, stewardship agreements, and easements with ʻohana to keep them rooted across generations. Uniquely, we can purchase a partial interest in a property to protect ancestral land from outside sale or development. At the time of writing, Kīpuka Kuleana is in the final stages of purchasing and protecting two kuleana parcels on Kauaʻi, in partnership with descendant ʻohana.

We support communities in learning and teaching about ʻāina by bringing together area ʻohana and their knowledge of place with Kīpuka Kuleana’s research database, which includes historical place names, maps, nupepa (newspaper), moʻolelo (stories), and research on the cultural and environmental significance of ʻāina. Throughout the year, we lead cultural field trips and education programs in partnership with local schools to teach keiki (children) and ʻōpio (youth) cultural practices, including mele (song) and oli (chant) composition, map reading, moʻolelo and place names, fishing, farming, foraging, lei making, hula, and kanikapila (ʻukelele). From planting native species to harvesting foods, they learn how ʻāina must be cared for and sustained before it may feed community. Through years of participation in our programs, youth become the alakaʻi (helpers) and mentors to younger children, imparting their cultural knowledge and skills to young learners and ultimately growing into the kiaʻi (protectors of place). Since 2021, we have hosted over 500 students on cultural field trips and educational programs. A key component of our work is partnering with private landowners and state agencies to restore access to ʻāina for education and stewardship purposes, which reconnects multigenerational ʻohana to parts of their home that have been made inaccessible due to private gates and walls.

We teach youth how to care for and gather natural resources from their home ahupuaʻa to feed their ʻohana, such as farming kalo (taro), caring for loko iʻa (fishponds), and growing traditional, nutrient-dense foods like ʻuala (sweet potato). Despite Hawaiʻi’s favorable growing climate, 90% of food consumed in Hawaiʻi is imported (Kent, 2016). Through ʻāina education and stewardship workdays, we teach youth how ʻāina is changing due to climate impacts like sea level rise and encroachment from invasive species, development, and gentrification, and how to practice kilo, the long-term observations of seasonal changes such as weather, fish movements, and celestial alignments. All of our stewardship activities, from stripping albizia bark to kill invasive trees that topple and block waterways during storms and flooding, to studying changes in the coral reef and streams, demonstrate how sustained care of ʻāina across generations is critical to healthy, resilient ecosystems.

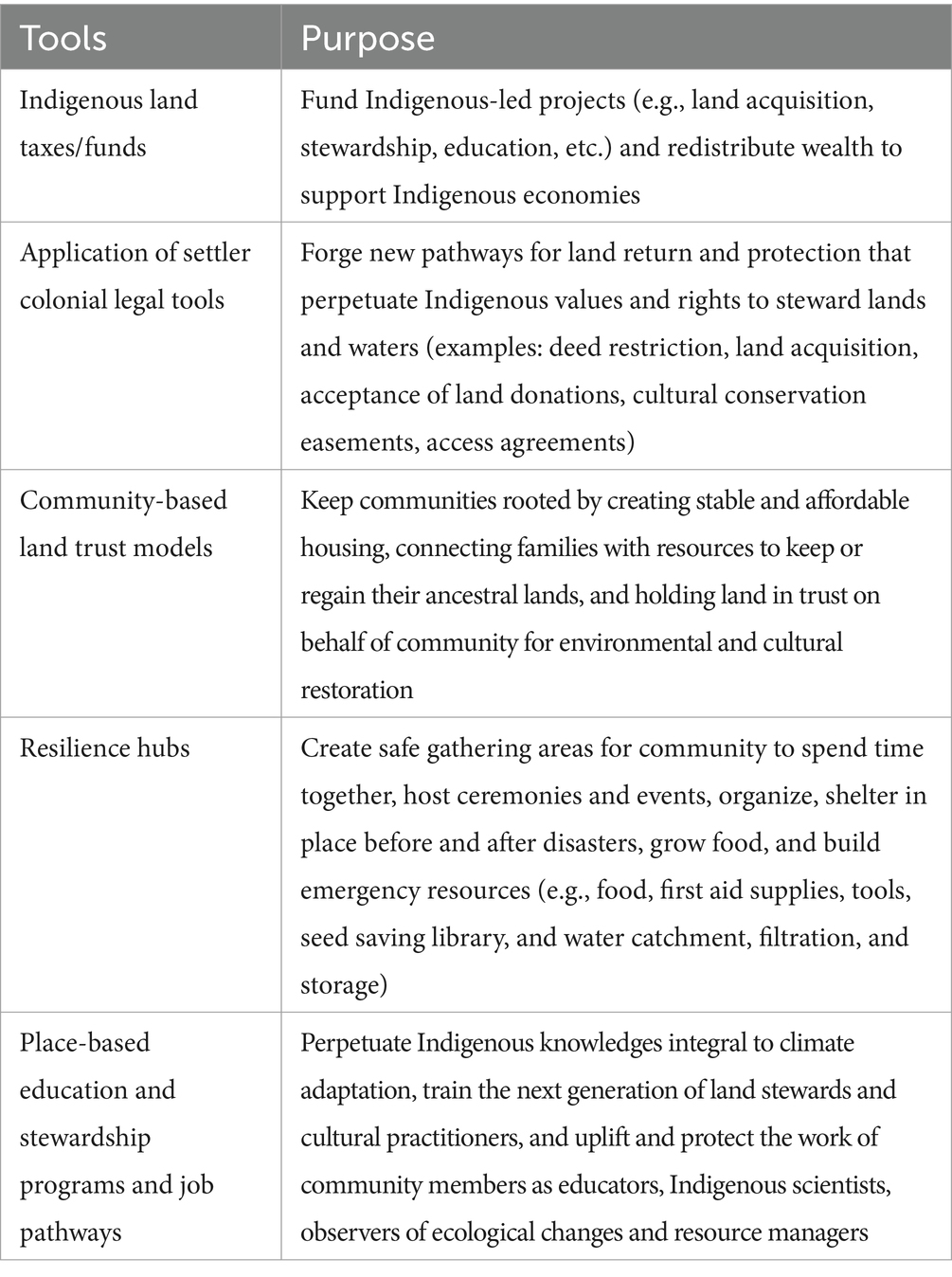

Kīpuka Kuleana’s efforts to protect ancestral lands on Kauaʻi, well as Land Back or ʻĀina Back efforts in Hawaiʻi, are still in their infancy. However, our work is connected to a growing constellation of rematriation efforts across the U.S. Through research networks and thought partnerships, we collaborate with Indigenous and allied groups to share tools and lessons in rematriation and climate adaptation. For example, in 2021 Kīpuka Kuleana and Indigenous and allied partners in Louisiana, California, and Borikén (Puerto Rico) formed the Land to Sea Network, with convening support from the Livelihoods Knowledge Exchange Network (LiKEN) and grant funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Program Office (#NA21OAR4310280). In this section, we weave together rematriation strategies that contribute to climate adaptation and keep land in community (see Table 1), led by our partners. These examples demonstrate how Indigenous groups and CLTs are using tools (e.g., Indigenous land taxes/funds, resilience hubs) and stewardship practices to support disaster recovery and hazard reduction, adapt in place, and root communities.

Table 1. Strategies for rematriation as a means of building climate adaptation and resilence shared in this article.

Indigenous land taxes (or “honor taxes”) offer a pathway to sustainably fund Indigenous-led land protection and restoration projects, which require intensive financial resources including administrative and legal support, staffing, infrastructure, and long-term stewardship. Established models include: Sogorea Te′ Land Trust’s Shuumi Land Tax (CA), Real Rent Duwamish (WA), Lahaina Land Fund (HI), Honor Native Land Tax (NM), Manna-Hatta Fund (NY), and Tongva Return the Land Fund (CA). Kīpuka Kuleana drew inspiration from these partners, especially the powerful women leading Sogorea Te′ Land Trust, when developing our Hōʻahu Kauaʻi Land Tax. Hōʻahu is a voluntary contribution that people who visit or call Kauaʻi home can make to return lands to community hands and keep Native Hawaiian and long-time families rooted to their homes. “Hōʻahu” (to set aside for the future) refers to hale hōʻahu, or houses where area residents brought regular offerings of their harvest to care for the needs of the entire community (Kīpuka Kuleana, 2024). This ancestral practice allows for the distribution of abundance and provides collective security for times of unstable weather, drought, or famine, preparing communities for uncertainty. Contemporary Indigenous land funds and taxes, rooted in older values of sharing, also redistribute wealth and support the revival of “Indigenous economies of care” that center Indigenous relationality and stewardship principles (Yellowhead Institute, 2021).

In a time of intensifying climate-related disasters, rooted and connected communities are crucial to adaptation and preparation for climate-induced hazards of the future. Long-time families on Kauaʻi serve as the first responders and community organizers when disasters occur, including through multiple hurricanes in 1959 (Dot), 1982 (Iwa), and 1992 (Iniki). In April 2018, a U.S. record-breaking 49.7 in. of rain over 24 hr triggered extreme flooding and dozens of landslides on Kauaʻi. Knowledge of past flood patterns and strong social networks enabled community mobilization and neighbor-to-neighbor responses that guided recovery from the disaster, which claimed no lives (Harangody et al., 2022). Reinvigorating local community stewardship of streams and waterways, once critical to Indigenous agricultural systems, through removal of invasive species, riparian planting, and regular observation and study using both Indigenous and western scientific tools, is working to reduce future flood risk.

Another example is the First Peoples’ Conservation Council of Louisiana (FPCC), “an Association that was formed to provide a forum for State recognized- and non-federally acknowledged Native American Tribes in coastal Louisiana to identify and solve natural resource issues on their Tribal lands” (FPCC: The First Peoples’ Conservation Council of Louisiana, n.d.). The work of FPCC is critical as “Tribal perseverance in-place has become more tenuous this century as sea level rise accelerated, storm frequency and intensity increased, and with it, the loss of coastal wetlands” (Maldonado et al., 2023). Climate-related hazards are exacerbating the impacts of 10,000 miles of canals cut through Louisiana’s coastal wetlands to create passageways for pipelines and navigation. FPCC tribes work with organizations to strategically place living shorelines (mainly oyster communities) and backfill canals dredged in Louisiana’s wetlands to restore marsh ecosystems, reduce land loss and flood risk, and protect sacred sites. These coastal restoration and adaptation efforts benefit all coastal communities and ecosystems (Lowlander Center, n.d.) and secure inland refuges for people and culturally significant flora relatives, including medicinal plants. These examples share how reclamation of Indigenous environmental stewardship and restoration efforts, often necessitated by climate disaster, build ecosystem resilience and enhance community safety.

The right to shelter in place and live with changing environments is inextricably tied to the self-determination and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples. In coastal Louisiana, the Atakapa Ishak/Chawasha Tribe of Grand Bayou Indian Village is developing strategies to live with more water, such as building floating gardens. Tribal leaders of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw in Louisiana have established a Community Outreach Program Office located on Shrimpers Row to serve as a resilience hub for community residents before and after hurricanes.

In California, urban women-led Sogorea Te′ Land Trust works to reclaim a land base for the Lisjan Nation (Ohlone) and the urban intertribal Indigenous communities who live within Lisjan territory, presently known as the Bay Area (Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, n.d.). Through land purchases, land donations, and implementation of legal tools like cultural conservation easements, Sogorea Te′ is returning lands to community so they may “grow, harvest, and process traditional medicines, vegetables and other Native foods and hold teaching circles to promote health and justice” (Middleton Manning et al., 2023). These spaces for community education, caretaking, and cultural restoration support food sovereignty and strengthen capacity to withstand climate disasters. Their Himmetka (meaning “in one place, together” in Chochenyo, the language of the Lisjan Nation/Ohlone in the East Bay) sites serve as climate resilience hubs that provide culturally relevant emergency supplies, including food, first aid supplies, tools, a seed saving library, and water catchment, filtration, and storage (Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, n.d.). In these examples, Indigenous communities resist resettlement and creatively adapt in place, while also offering spaces to shelter and access needed supplies and resources together.

As Indigenous communities face dual crises of housing and climate change, the community land trust (CLT) model provides a mechanism for the ownership and protection of land “in common,” while establishing inheritable, renewable ground leases with residents who own homes on the land (Land in Common, 2024; Sommer and Kellman, 2024). When a CLT acquires land, that land permanently leaves the real estate market, which helps cap rental or mortgage rates on housing units and guarantee affordability across generations (Goodluck, 2023). One example is the Dishgamu Humboldt Community Land Trust of the Wiyot Tribe, the first federally recognized Tribe to develop a CLT arm that focuses on “affordable housing creation, workforce development, and environmental and cultural restoration” (Wiyot Tribe, 2024). Through a $14 million grant from the state of California, the land trust is converting and restoring empty buildings into transitional housing for Wiyot youth (Goodluck, 2023; Nonko, 2023).

Another example is the Lahaina Community Land Trust (LCLT), which emerged in response to the devastating wildfires on Maui in August 2023. The fires were sparked by extreme wind conditions and severe drought driven by climate change and exacerbated by centuries of water diversion by plantations and now hotels, golf courses, and luxury homes (Rust et al., 2023; Drewes, 2024). Before the fires, generational Lahaina residents were being pushed out of their homes by ever-rising property values and the volatile speculator-driven real estate market. The fires claimed 102 lives, destroyed 2,200 homes, and left 12,000 people without housing (McAvoy and Lin, 2024), making it the deadliest U.S. wildfire in over a century (Treisman, 2023). Immediately, ʻohana who had lost their homes, and even family members, faced offers by disaster capitalists and real estate investors to buy their charred lots (Lakhani, 2024). Community leaders, many of whom had lost their homes themselves, urged Lahaina ʻohana not to sell and organized within weeks using a land trust model to secure as much land as possible for the community and prevent future gentrification. LCLT aims to “protect Lahaina lands by offering landowners considering the sale of their land a community based alternative to investor transactions, prioritizing our community’s well-being over profit” (Lahaina Community Land Trust, n.d.). Lahaina families can incorporate a deed restriction on their land to give LCLT the first right of refusal to buy their land, if they ever need to sell. This legal tool creates a layer of protection to keep land in community hands and off the speculative market. In the words of LCLT leader Kapali Keahi, “Everyone wants a piece of Lahaina. We cannot compete with that. Together, though, we stand a chance.” One year after the fires, LCLT has secured a $15 million funding package from the County of Maui, raised additional funds for operations and acquisitions from private funding sources, and protected its first parcel of land, in partnership with The Conservation Fund (Subiono, 2024). These examples highlight how Indigenous community land trusts hold potential to offer housing stability and keep communities together even in the aftermath of disaster.

From the small rural island of Kauaʻi to the sprawling cityscape of the Bay Area to the fragile yet sacred coasts of Louisiana, Indigenous-led land trusts and stewardship efforts make strides in addressing harms of historical and present-day colonization while restoring connections to ancestral lands through rematriation and land return. This community case study offers insights into Hawaiian community-based land trust Kīpuka Kuleana’s work for rematriation, linking our efforts to Land Back and climate change adaptation work of our Indigenous and allied partners across the U.S. The models highlighted in this article offer opportunities for mitigating climate change impacts that disproportionately affect Indigenous communities, including loss of food security, property, health, housing, work, education, self-determination, and sovereignty (Maldonado et al., 2013; Rising Voices, 2014; Moulton et al., 2018). Rematriation is not just beneficial for people and place; it is arguably essential for a just, sustainable future, shifting from a colonial, extractive, profit-driven relationship to lands and waters toward an Indigenous relationality and adaptation for collective health and abundance. When ʻāina guides people in caring for land together, listening well, and collectively determining what is pono for the entire community, we forge a path toward a thriving future for all living beings.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

SB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – review & editing. JM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Mahalo (thank you) to the ʻohana and kūpuna who guide Kīpuka Kuleana’s work to protect cultural landscapes and family lands on Kauaʻi; to our Land to Sea Network which was made possible through a research grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Program Office (#NA21OAR4310280), through convening support from Livelihoods Knowledge Exchange Network, and through deep, trusting relationships and close collaboration across community partners in California (Sogorea Te′ Land Trust, Asian Pacific Environmental Network, Sierra Fund), Louisiana (First People’s Conservation Council of Louisiana, Lowlander Center), Borikén/Puerto Rico (El Puente, DUNAS/Descendants United for Nature, Adaptation, and Sustainability, Para La Naturaleza) and advisors at UC-Davis (Beth Rose Middleton), UC-Berkeley (Louise Fortmann, Alan Di Vittorio), Stanford University (Sibyl Diver, Kajal Khanna); to our thought partners at Real Rent Duwamish (Laurie Bohm), the Wiyot Tribe Dishgamu Humboldt Community Land Trust (Carrie Tully), Lahaina Community Land Trust (Mikey Burke, Carolyn Auweloa, Kapali Keahi, Autumn Ness, Anastasia Arao-Tagauna, Noelle Bali). “It’s a kākou thing”; this rematriation work is collective, requires many hands and hearts, and carves a path of hope for a better future and a healthier planet for us all.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Andrade, C. (2008). Hāʻena through the eyes of the ancestors. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Bremer, L. L., Falinski, K., Ching, C., Wada, C. A., Burnett, K. M., Kukea-Shultz, K., et al. (2018). Biocultural restoration of traditional agriculture: cultural, environmental, and economic outcomes of lo‘i kalo restoration in he‘eia, O‘ahu. Sustainability 10:13. doi: 10.3390/su10124502

Brondizio, E., Diaz, S., Settele, J., Ngo, H. T., Gueze, M., Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y., et al. (2019). “Assessing a planet in transformation: rationale and approach of the IPBES global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services” in IPBES global assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services report. eds. H. Mooney, G. Mace, and M. M. Carneiro Da Cunha (Germany: IPBES), 1–48.

Buchanan, C. (2022). The long road to #LandBack. E-Tangata. Available at: https://e-tangata.co.nz/history/the-long-road-to-landback/ (Accessed August 20, 2024).

Courtney, C. A., Gelino, K., Romine, B. M., Hintzen, K. D., Addonizio-Bianco, C., Owens, T. M., et al. (2019). Guidance for disaster recovery preparedness in Hawai'i. Pasadena: Tetra Tech, Inc. for the University of Hawai'i Sea Grant College Program and State of Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources and Office of Planning, 1–118.

Diver, S., Vaughan, M. B., and Baker-Medard, M. (2024). Collaborative care in environmental governance: restoring reciprocal relations and community self-determination. Ecol. Soc. 29:7. doi: 10.5751/ES-14488-290107

Drewes, P. (2024). West Maui’s water woes: decades-long battle for Lahaina’s lifeline amid fire devastation, future drought concerns. KITV4 island news. Available at: https://www.kitv.com/news/west-mauis-water-woes-decades-long-battle-for-lahainas-lifeline-amid-fire-devastation-future-drought/article_d5eefeb8-5533-11ef-a0a2-2f5b010df88e.html (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Farrell, J., Burow, P. B., McConnnell, K., Bayham, J., Whyte, K., and Koss, G. (2021). Effects of land dispossession and forced migration on indigenous peoples in North America. Science 374:6567. doi: 10.1126/science.abe4943

Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Lepofsky, D., Lertzman, K., Armstrong, C. G., Brondizio, E. S., Gavin, M. C., et al. (2021). Scientists’ warning to humanity on threats to indigenous and local knowledge systems. J. Ethnobiol. 41, 144–169. doi: 10.2993/0278-0771-41.2.144

Ford, J. D., King, N., Galappaththi, E. K., Pearce, T., McDowell, G., and Harper, S. L. (2020). The resilience of indigenous peoples to environmental change. One Earth 2:6. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.05.014

FPCC: The First Peoples’ Conservation Council of Louisiana. (n.d.). Our history. Available at: https://fpcclouisiana.org/about-usour-history/our-history/ (Accessed June 12, 2024).

Garcia, N., and Pastrana, G. (2022). Reclaiming indigenous lands in Costa Rica: FRENAPI. Cultural survival. Available at: https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/reclaiming-indigenous-lands-costa-rica-frenapi (Accessed August 10, 2024).

Garovoy, J. B. (2005). Ua Koe ke Kuleana o na kanaka (reserving the rights of native tenants): integrating Kuleana rights and land trust priorities in Hawaiʻi. Harvard Environ. Law Rev. 29:2.

Goodluck, K. (2023). The Wiyot Tribe is getting its land back and making California more affordable. ZNetwork. Available at: https://znetwork.org/znetarticle/the-wiyot-tribe-is-getting-its-land-back-and-making-california-more-affordable/ (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Gouldhawke, M. (2020). Land as a social relationship. Briar Patch Magazine. Available at: https://briarpatchmagazine.com/articles/view/land-as-a-social-relationship (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Greenwood, M., and Lindsay, N. M. (2019). A commentary on land, health, and indigenous knowledge(s). Glob. Health Promot. 26, 82–86. doi: 10.1177/1757975919831262

Harangody, M., Vaughan, M. B., Richmond, L. S., and Luebbe, K. K. (2022). Hālana ka manaʻo: place-based connection as a source of long-term resilience. Ecol. Soc. 27:4. doi: 10.5751/ES-13555-270421

Haupt, W. (2023). Median home price hits new high on Kaua‘i. The Garden Island. Available at: https://www.thegardenisland.com/2023/10/10/hawaii-news/median-home-price-hits-new-high-on-kauai/ (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Hibbard, M. (2021). Indigenous planning: from forced assimilation to self-determination. J. Plan. Lit. 37, 17–27. doi: 10.1177/08854122211026641

Horton, A. (2024). John Oliver: ‘Hawaiʻi is being reshaped by wealthy outsiders.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/article/2024/aug/12/john-oliver-hawaii-last-week-tonight-recap (Accessed August 12, 2024).

Kameʻeleihiwa, L. (1992). Native land and foreign desires: How shall we live in harmony? Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press.

Kent, G. (2016). “Food security in Hawaiʻi” in Food and power in Hawaiʻi: visions of food democracy. eds. A. H. Kimura and K. Suryanata (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), 36–53.

Kīpuka Kuleana. (2024). Kīpuka Kuleana | Protection of Cultural Landscapes and Family Lands. Available at: https://www.kipukakuleana.org/ (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Lahaina Community Land Trust. (n.d.). About Lahaina Community Land Trust. Available at: https://lahainacommunitylandtrust.org/about (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Lakhani, N. (2024). First came the Maui wildfires. Now come the land grabs: who owns the land is key to Lahaina’s future. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/mar/15/maui-wildfires-community-land-trust (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Land in Common. (2024). What is a community land trust? Available at: https://www.landincommon.org/what-is-a-community-land-trust/#:~:text=Community%20land%20trusts%20(CLTs)%20are,work%20of%20civil%20rights%20organizers (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Liu, P., and Hunter-Hart, M. (2024). Meet the billionaires buying up Hawaii. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/phoebeliu/2024/02/18/meet-the-billionaires-buying-up-hawaii/?sh=56f3424b50f3 (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Lowlander Center. (n.d.). Restoring Louisiana Marshes: protecting sacred sites, increasing tribal resilience, and reducing flood risk. Available at: https://www.lowlandercenter.org/canal-backfilling (Accessed June 8, 2024).

Maldonado, J., and Middleton, B. R. (2022). “Climate resilience through equity and justice: holistic leadership by tribal nations and indigenous communities in the southwestern United States” in Cooling down: local responses to global climate change. eds. S. M. Hoffman, T. H. Eriksen, and P. Mendes (Brooklyn: Berghahn Books), 269–291.

Maldonado, J., Peterson, K., Turner, R. E., Dardar, T., Parfait-Dardar, S., Philippe, R., et al. (2023). “Climate actions with a lagniappe: coastal restoration, flood risk reduction, sacred site protection, and tribal communities’ resilience” in Anthropology and climate change. eds. S. Crate and M. Nuttall (New York: Routledge), 157–168.

Maldonado, J. K., Shearer, C., Bronen, R., Peterson, K., and Lazrus, H. (2013). The impact of climate change on tribal communities in the US: displacement, relocation, and human rights. Clim. Chang. 120, 601–614. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-0746-z

McAvoy, L., and Lin, M. (2024). Maui remembers the 102 lost in the Lahaina wildfire with a paddle out 1 year after devastating blaze. AP News. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/maui-hawaii-wildfire-anniversary-paddle-out-da5862aceca17fc2ca6f63ad26dddc05 (Accessed August 8, 2024).

McKenzie, D., and Swails, B. (2018). Land was stolen under apartheid. It still hasn’t been given back. CNN. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2018/11/20/africa/south-africa-land-reform-intl/index.html (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Middleton Manning, B., Gould, C., LaRose, J., Nelson, M. K., Barker, J., Houck, D. L., et al. (2023). A place to belong: creating an urban, Indian, women-led land trust in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ecol. Soc. 28:1. doi: 10.5751/ES13707-280108

Moulton, A., Soqo, S., and Ferreira, K. (2018). Community-led, human rights-based solutions to climate-forced displacement: a guide for funders. Cambridge: UUSC.

Nonko, E. (2023). An Indigenous community land trust is creating housing through #LandBack. Available at https://nextcity.org/features/an-indigenous-community-land-trust-is-creating-housing-through-landback (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Oil Change International (2021). Indigenous resistance against carbon. Washington, DC: Oil Change International.

Oishi, N. (2022). Love, memory, and reparations: looking to the bottom to understand Hawai'i's Mauna kea movement. Asian Am. Law J. 29:126. doi: 10.15779/Z38ZG6G79S

Owen, J. R., Kemp, D., Lechner, A. M., Harris, J., Zhang, R., and Lèbre, E. (2023). Energy transition minerals and their intersection with land-connected peoples. Nature Sustainability, 6. doi: 10.1038/s41893-022-00994-6

Pasternak, S., and King, H. (2019). Land back: a Yellowhead Institute red paper. Yellowhead Institute. Available at: https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/ (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Pieratos, N. A., Manning, S. S., and Tilsen, N. (2021). Land back: a meta narrative to help indigenous people show up as movement leaders. Leadership 17:1. doi: 10.1177/1742715020976204

Preza, D. C. (2010). The empirical writes back: re-examining Hawaiian dispossession resulting from the Great Māhele of 1848. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Available at: https://malu-aina.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Preza.Thesis.The-Empirical-Writes-Back-copy.pdf (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Pukui, M. K., and Elbert, S. H. (1986). Hawaiian dictionary: Hawaiian-English, English-Hawaiian. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Racehorse, V., and Hohag, A. (2023). Achieving climate justice through land Back: an overview of tribal dispossession, land return efforts, and practical mechanisms for #LandBack. Colorado Environ. Law J. 175:34.

Reynolds, E. (2021). Is Hawaii the next ʻit’ place to live? Inside its impressive real estate offerings attracting the wealthy. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/emmareynolds/2021/05/20/is-hawaii-the-next-it-place-to-live-inside-its-impressive-real-estate-offerings-attracting-the-wealthy/?sh=5feb5525bb20 (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Rising Voices (2014). Adaptation to climate change and variability: bringing together science and indigenous ways of knowing to create positive solutions. 2nd annual rising voices workshop report. Boulder, CO: National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Roversi, A. (2012). The Hawaiian land hui movement: a post-Māhele counter-revolution in land tenure and community resource management. Univ. Hawaii Law Rev. 34:557.

Rust, S., Smith, H., and Pineda, D. (2023). How a perfect storm of climate and weather led to catastrophic Maui fire. LA Times. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2023-08-11/how-did-climate-change-influence-catastrophic-hawaii-fire (Accessed June 4, 2024).

Simon, J. (2024). Demand for minerals sparks fear of mining abuses on Indigenous peoples’ lands. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2024/01/29/1226125617/demand-for-minerals-sparks-fear-of-mining-abuses-on-indigenous-peoples-lands (Accessed August 15, 2024).

Sogorea Te’ Land Trust (n.d.). Sogorea Te’ Land Trust. https://sogoreate-landtrust.org (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Sommer, L., and Kellman, R. (2024). After the fires, a Maui community tries a novel approach to keep homes in local hands. National Public Radio. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2024/03/14/1237541048/lahaina-maui-community-land-trust-climate-change (Accessed June 11, 2024).

State of Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism (DBEDT). (2022). 2022 annual visitor research report. Available at: https://www.hawaiitourismauthority.org/media/11448/2022-annual-report-final3.pdf (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Subiono, R. (2024). Land trust seeks to keep ‘Lahaina lands in Lahaina hands.’ Hawaiʻi Public Radio. Available at: https://www.hawaiipublicradio.org/the-conversation/2024-08-08/land-trust-shares-effort-to-keep-lahaina-lands-in-lahaina-hands (Accessed August 8, 2024).

Sustainable Economies Law Center (2023). Seeds of land return. https://www.theselc.org/seeds_of_land_return (Accessed June 18, 2024).

The Associated Press (2022). Out-of-state buyers drove up housing prices on Kauai in 2021. Hawaii News Now. Available at: https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2022/01/04/out-of-state-buyers-drove-up-housing-prices-kauai-2021/ (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Thomas, K., Hardy, R. D., Lazrus, H., Mendez, M., Orlove, B., Rivera-Collazo, I., et al. (2019). Explaining differential vulnerability to climate change: a social science review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 10:2. doi: 10.1002/wcc.565

Thompson, C. E. (2020). Returning the land. Grist Fix Solutions Lab. Available at: https://grist.org/fix/indigenous-landback-movement-can-it-help-climate/ (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Trepte, T., and Klink, D. (2021). Visualizing land dispossession on Kauaʻi’s North Shore. Unpublished report: Stanford University.

Treisman, R. (2023). Maui’s wildfires are among the deadliest on record in the U.S. Here are some others. National Public Radio. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2023/08/15/1193710165/maui-wildfires-deadliest-us-history (Accessed June 4, 2024).

Vaughan, M. B., Kinney, W., Fu, J. K., Kagawa-Vivani, A., Koethe, F., Geslani, C., et al. (2019). “Kahaleʻa, Haleleʻa: fragrant, joyful home, a visit to Anini, Kauaʻi” in Detours: a decolonial guide to Hawaiʻi. eds. H. K. Aikua and V. Gonzalez (Durham: Duke University Press), 96–106.

Whyte, K. (2017). Indigenous climate change studies: indigenizing futures, decolonizing the anthropocene. English Lang. Notes 55:1.

Whyte, K. (2019). “The Dakota access pipeline, environmental justice, and US settler colonialism” in The nature of Hope (Denver: University Press of Colorado), 320–337.

Wilkins, B. (2023). Ecuador court orders stolen land returned to Siekopai people. Common Dreams. Available at: https://www.commondreams.org/news/siekopai (Accessed August 10, 2024).

Winter, K. B., Lincoln, N. K., and Berkes, F. (2018). The social-ecological keystone doncept: a quantifiable metaphor for understanding the structure, function, and resilience of a biocultural system. Sustainability 10:9. doi: 10.3390/su10093294

Wiyot Tribe. (2024). Dishgamu Humboldt community land trust. Available at: https://www.wiyot.us/350/Dishgamu-Humboldt-Community-Land-Trust (Accessed June 11, 2024).

Yang, L., Zerega, N., Montgomery, A., and Horton, D. E. (2022). Potential of breadfruit cultivation to contribute to climate-resilient low latitude food systems. PLOS Climate. 1:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000062

Yellowhead Institute. (2021). Cash back: a Yellowhead Institute red paper. Available at: https://cashback.yellowheadinstitute.org/ (Accessed August 22, 2024).

Keywords: Native Hawaiian, community land trust, indigenous resilience, climate change, adaptation, Hawaii, land protection, indigenous stewardship

Citation: Barger S, Vaughan MB, Aiu C, Akutagawa MKH, Beall EC, Luck J, Cordy D and Maldonado J (2024) Kīpuka Kuleana: restoring relationships to place and strengthening climate adaptation through a community-based land trust. Front. Sustain. 5:1461787. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2024.1461787

Received: 09 July 2024; Accepted: 30 August 2024;

Published: 25 September 2024.

Edited by:

April Taylor, Texas A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

Miriam Jorgensen, Harvard Kennedy School, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Barger, Vaughan, Aiu, Akutagawa, Beall, Luck, Cordy and Maldonado. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Barger, c2FyYWhAa2lwdWtha3VsZWFuYS5vcmc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.