94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain., 26 June 2024

Sec. Sustainable Consumption

Volume 5 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2024.1416567

Adoption of sufficiency-oriented lifestyles is an important part of curbing overconsumption, yet many individuals who try to reduce their consumption volumes experience social difficulties. Combining the perspectives of care and sufficiency-oriented lifestyle changes, this article aims to contribute to the understanding of why such social obstacles occur, how they might be counteracted and in what ways social relations instead may facilitate consumption reduction. Starting from an interview study with 25 Swedish consumption reducers, this article builds on a processual theory of consumer identity and the perspective of care to explore how care and consumption are (re)negotiated in the different stages of reduction. The results highlight the different aspects of care involved in consumption reduction – from motivations for change to negotiations toward a more holistic understanding of care – and show that consumption reduction in many ways is an ongoing process of both caring and striving. By emphasizing how care is renegotiated in a gradual construction of a caring consumer identity, this article discusses the importance of maintaining a sensitivity to the multi-faceted nature of care, acknowledging it both as a source of difficulties and as a key driver for sufficiency-oriented lifestyle changes.

In the face of climate and ecological crises, many individuals are looking for different ways to reduce their own negative impact on the planet. One way to do so is to reduce one’s consumption in various areas, such as energy, fossil-driven transport, meat, fast fashion or new tech products. This is in line with the idea of sufficiency – to reduce the demand for and total volume of consumption and resource use, aiming to keep humanity within the planetary boundaries while safeguarding well-being for all (Princen, 2005; Schneidewind and Zahrnt, 2014; O’Neill et al., 2018; Callmer, 2019; IPCC, 2022; Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen, 2022). Collective and political action is needed to orient consumerist societies toward sufficiency; however, such a transformation needs to involve people and actors at all levels, from micro- to macro. Attempts to reduce consumption at the individual level may, however, result in difficulties in the social realm. Previous research show that some common obstacles experienced by people who aim to reduce their consumption are frustration with other’s (unsustainable) shopping behaviour, conflicts with friends and family members, difficulties to uphold one’s ambitions due to social inconveniences, and (in the case of parents) worry about one’s children (Isenhour, 2010; Cherrier et al., 2012; Callmer, 2019; Boström, 2021).

Considering the increasingly urgent need to curb overconsumption and move to consumption practices that are compatible with the planetary boundaries [see, e.g., Alfredsson et al. (2018) and Akenji et al. (2021)], it is crucial to understand more about the personal and social obstacles experienced by individuals who try to reduce their consumption, how such obstacles may be avoided or counteracted, and how social support may facilitate consumption reduction. In this paper, we aim to contribute to this understanding by combining the perspective of sufficiency-oriented lifestyle changes (in this case consumption reduction) with a perspective of care, building on the growing interest for care within the field of sufficiency and sustainable consumption (Godin and Langlois, 2021; Karimzadeh and Boström, 2023; Lorek et al., 2023; Wahlen and Stroude, 2023). The multidimensional nature of care is useful to describe the complexities and ambiguities involved in the consumption reduction process and carries explanatory potential when addressing why it can be so difficult to follow through with one’s reduction ambitions. It may also, in some cases, function as a necessary component in the process toward a more sustainability-dedicated lifestyle change. We will look closer at the ways in which care and consumption are intertwined and how the connection between the two may be (re)negotiated during a process of voluntary consumption reduction. In doing so, we depart from the work by Cherrier and Murray (2007) who in their “processual theory of consumer identity” describe the process of dismantling one (normative and unreflective) consumption lifestyle and constructing another (reflective and “downshifted”) as one of identity negotiation that plays out in four stages: sensitization, separation, socialization and striving. This process is deeply entangled with the social relations and contexts within which the individual downshifting processes play out. Adding a care lens to this process, mainly provided by Shaw et al.’s (2017) theory of care in consumption, will contribute to the understanding of the interconnectivity of care and consumption, the different aspects of care involved in a consumption reduction process, and, not the least, the process of negotiating care in the gradual construction of a caring consumer identity. Shaw et al. (2017: 415) describe care in consumption as “a circular and dynamic process involving the combination of awareness, responsibility and action”, and have developed their theory by expanding on (among others) Tronto’s (2013) five “phases of care” – care about, caring for, caregiving, care receiving, and caring with. To combine these perspectives – consumer identity negotiation and care in consumption – in an empirical analysis of consumption reducers will provide a theoretical contribution both to the literature on sustainable lifestyles and to the growing field of care and consumption.

Departing from an interview study with 25 individuals in different stages of their consumption reduction, the analysis focuses on how the interviewees renegotiate various aspects of consumption and care in relation to others – family, friends, colleagues, acquaintances, and distant (human and non-human) others. Guiding the analysis is the question of how care plays out in the different stages of the consumer identity negotiation process. After a presentation of the material and methods of the study, we will present Cherrier and Murray’s (2007) theory of identity negotiation and discuss the interconnections of care and consumption, specifically focusing on the work of Shaw et al. (2017). Following this, we will examine these interconnections and explore the dynamics at play in the process of negotiating and consolidating a caring consumer identity, based on material from our interviews. This is followed by a concluding discussion around the ambiguities of care and its relevance for sufficiency-oriented lifestyle change.

In a research project aiming to gain knowledge about the social (im)possibilities experienced by individuals trying to reduce their consumption, we interviewed 25 individuals in different phases of consumption reduction – “reducers.” The interviewees were between the ages of 22 and 74, 16 women and 9 men, and they all lived in Sweden, in urban, semi-urban and rural areas. We strived for heterogeneity in the sample in terms of geography, age, gender, housing and family situation, and socioeconomic situation, and also in terms of their reduction ambitions. The semi-structured qualitative interviews were performed face-to-face or via Zoom between February and September 2023, and lasted between 45 and 90 min. The interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim, followed by an analysis of the material through qualitative coding of the transcriptions.

Before initiating the interview study, our aim was to recruit one group of individuals who had recently initiated a process of reducing their consumption. This, however, turned out to be difficult to realize. When reaching out to potential informants through different channels – the university’s web page, personal contacts, organizational newsletters, and social media – the great majority of the responses we received were from individuals who were already conscious consumers and whose current active reduction efforts followed a longer period of reflection on their own and/or others’ unsustainable consumption behavior. Those who did claim to be in the beginning of a consumption reduction process were individuals who for example had a New Year’s resolution to only buy second hand or to have a no-buy year, or who had experienced difficulties in making the ends meet during the 2022 energy crisis and therefore found it important to cut their expenses for heating, electricity and/or (fossil) car fuels. When inquiring about their thoughts on consumption, however, many of them indicated having reflected on how to consume more sustainably for years. This suggests that for many individuals, taking the step to reduce their consumption in one or several areas may constitute a threshold, even when one is trying to make conscious choices about one’s consumption (see also Cherrier et al., 2012). It should be mentioned here that the interviews took place following a period of steep increases in energy prices and costs of living in Sweden, which in several cases made financial incentives a strong driver for implementing change. The interviewees aimed at reduction in one or more consumption areas, such as fashion, new products, food waste, meat consumption, electricity and fossil fuels. The more dedicated reducers aimed at a general reduction and consciousness in as many consumption areas as possible, often including not flying and turning into vegan/vegetarian diets. The great majority of the group have a high education level and could socioeconomically and culturally be identified as middle class. The socioeconomic background of the interviewees was not specifically inquired for in the interview guide; however, one interviewee specifically mentioned coming from a working class background and four others talked about having grown up in thrifty households, and/or households with small economic margins. In regard to current living situation, two interviewees were students with very low incomes, one interviewee was living on sickness benefits, and another had, partly due to the choice of working part time, a strained economic situation. 12 out of 25 lived in a household with their partner and children, 7 lived with partners, 4 lived in single households and 2 were single parents living with children. The final selection of participants was made prioritizing interviewees at an early stage of consumption reduction, in order to correct the bias toward already conscious consumers among those who had registered their interest for being interviewed. A few potential informants living outside Sweden were also excluded due to the geographical criteria.

The issue of care was not explicitly asked about in the interviews. However, in the initial analysis of the material, care appeared as a highly relevant issue and central to understanding people’s experiences of their consumption reduction journeys. In the final phase, the empirical material was therefore analyzed thematically (Braun and Clarke, 2021) based on the theoretical framework explained below. The coding of the material into identified themes was done manually after the elaboration of the framework.

The difficulties experienced by individuals who aim to consume less can partly be explained by the fact that we live in a consumerist society where overconsumption is perceived as the normal way of consuming. In this society, we are taught that consumption plays a central role when we solve problems, when we relate to others, and when we try to find our place in the world (Boström, 2023). Further, consumption provides a way of comparing and positioning us in relation to others, both the people we want to distance ourselves from and the groups we wish to belong to Jackson (2005). It constitutes a foundation of the rituals that establish and maintain social relations: meeting around food and drinks, celebrating achievements or showing affection with gifts and vacation travels (Boström, 2021). In this sense, we consume to show that we care (Miller, 1998; Karimzadeh and Boström, 2023). The active decision to reduce one’s consumption thus comes with consequences for how such “caring rituals” can be performed: perhaps the consumption practices maintaining the rituals need to shift (e.g., from city weekends with flight travel to local “staycations” reached by public transport), or one might have to find other, non-material, ways to show affection.

Cherrier and Murray (2007) illustrate the process of consumer identity negotiation with individuals aiming to gradually dispose of material belongings in an effort to downshift – to reduce their consumption and simplify their lifestyle. They argue that this process plays out in four stages: sensitization, separation, socialization and striving. In its entirety, it is both a process of dispossession and reducing one’s consumption, and a more reflexive process that goes beyond the material and includes inner development. Regarding the first stage, sensitization, the authors describe how the process of downshifting or dispossession is often initiated by a triggering event, sensitizing the individuals to reflect upon, and questioning, the beliefs, structures and “truths” that they have until then taken for granted. Before this sensitization occurs, consumer choices are made in an unreflective manner. A triggering event is described in terms of “before” and “after.” It can be a traumatic experience such as the loss of a loved one or being victim to a crime, but also experiences of a natural life passage (e.g., going to college, children moving out), reading a certain book, going through a divorce, or finding oneself in a negative job situation. The common thread of these events was that they interrupted the informants’ lives and caused them to pause and reflect on their situation and way of life. This “awakening” is needed to start questioning one’s previous ways of understanding the world and how to lead life [see also Osikominu and Bocken (2020)].

The sensitization stage is followed by a stage of separation, where the questioning of one’s normative background leads to distancing, both emotionally and physically, from certain groups, behaviors, and values. This may include separation from family members, partners, or close friends. In this way, the “downshifters” seek independence from their previous ways of being while trying to find new forms of socializing and making sense of the world. The third and following socialization stage is when the downshifters reach out to new social spheres, to seek others who may guide them to new ways of living in the world. This phase, Cherrier and Murray argue, “shows the crucial importance of others in shaping and defining new normative backgrounds” (Cherrier and Murray, 2007: 22).

The process of negotiating a new consumer identity is not one with a clear goal in sight or a finishing line to cross. In the case of downshifting, it is rather a gradual process of shifting – from an existential mode of “having” to one of “being” (Cherrier and Murray, 2007, drawing on Fromm, 1978). The fourth, and final, stage described by Cherrier and Murray, striving, illustrates the ongoing tensions between these two modes: a continuous struggle entailed in being an individual with anti-consumerist ideals living in a consumerist society. It is characterized by continuing negotiation and renegotiation of one’s own identity, desires, relations, needs, and goals.

In the context of the empirical material for this study, far from every consumer who aims to reduce their consumption does so with an ambition to significantly downshift, or to eventually arrive at a radically different lifestyle. Most of our interviewees aim at an overall conscious consumption and reductions in certain areas; the most dedicated at an overall reduction in all or almost all areas. Not all interviewees address the “big points” of food, mobility and housing (cf. Bilharz and Schmitt, 2011; see also Wynes and Nicholas, 2017); however, in specifically aiming at reducing their total consumption, they are aware of the insufficiency of strategies concerned with simply changing which type of new products they buy (like buying more energy-efficient household appliances, or a new t-shirt made of recycled polyester). In this sense, they go beyond the “small matters” (Bilharz and Schmitt, 2011) that have minimal impact on an individual’s ecological footprint and have begun to question the impact of consumption in itself [for recent literature on the need to reduce material consumption, see, e.g., Akenji et al. (2021) and Merz et al. (2023)]. The motives for reducing span from wanting to reduce one’s ecological footprint and not contribute to the socioecological destruction caused by overconsumption, to trying to manage economic constraints, looking for a challenge or simply being tired of one’s own and others’ consumption behavior. Apart from when the reduction takes the shape of a specific challenge, such as for example a “no-buy year” or to completely stop eating animal products, the ambitions to reduce one’s consumption seldom have a set final goal.

Recent years have seen a growing interest for care within the field of sustainable and ethical consumption (Shaw et al., 2017; Godin and Langlois, 2021; Gram-Hanssen, 2021; Godin, 2022; Karimzadeh and Boström, 2023; Wahlen and Stroude, 2023), and, further, calls for placing care at the center of our economies and societies as a necessary step toward the radical transformation that is needed to prevent ecological breakdown and achieve social justice (Lorek et al., 2023). So, how can we understand the many dimensions of care in relation to consumption and to the development of a new consumer identity?

Godin (2022) and Godin and Langlois (2021) have shown how practices of care and consumption are deeply intertwined. Godin and Langlois (2021) argue that care work often acts as a barrier to more sustainable consumption practices, by upholding (often gendered) habits and routines and mobilizing the same resources that are needed for transforming those routines. Wahlen and Stroude (2023: 8) use the concept of resonance from the work of Hartmut Rosa to discuss care and sustainable consumption, suggesting that resonance help to better understand care as “a mode of relating to people, to things and activities, and to collective singulars such as nature and history.” Closely linked to consumption reduction, Karimzadeh and Boström (2023: 7) argue that “caring practices could also integrate pro-environmental concerns and being informed by a sufficiency principle.” Such caring practices, Karimzadeh and Boström argue, include the pre-consumption or acquisition phase (carefully choosing if and what to buy, and buy products that will last longer), the consumption phase (responsibly caring for and maintaining one’s belongings to extend their lifetime), and the post-consumption phase (prioritizing repair and reuse of products over buying new ones). Adding to this, care is also of importance in some practices of divestment and disposal (Evans, 2018) with potential to strengthen sustainable consumption practices, such as donating one’s belongings to second-hand shops (Bohlin, 2019) and decluttering using the KonMari method (Chamberlin and Callmer, 2021).

Expanding on Tronto’s (2013) five “phases of care” – care about, caring for, caregiving, care receiving, and caring with – Shaw et al. (2017) develop a theory of care in consumption that conceptualizes care as both systemic and dynamic, involving a multitude both of interdependent stakeholders (e.g., consumers, producers, retailers, NGOs) and “relations of dependency” of one actor on another (Shaw et al., 2017: 428). Their theory further emphasizes that care for others is deeply intertwined with care for oneself, and Shaw et al. highlight that in consumption, different aspects of caring and who we care for and with may interfere with each other. To care for the environment or for the social conditions of workers in distant countries can often conflict with more urgent caring needs in the immediate family. Consumption is also often tied to self-care (Godin, 2022), connected to sustainable consumption through caring for one’s own health by, for example, choosing to buy organic and pesticide-free produce (Shaw et al., 2017). Quite often, however, consumers must weigh care for their loved ones or their own health against care for the environment or human rights. In a neoliberal culture stressing the sovereign individual (Sassatelli, 2007) and a consumerist infrastructure which does not prioritize ethical considerations and care for environment and distant others (but, rather, profits), self-interest becomes a (necessary) question of caring for oneself when managing multiple, and sometimes overwhelming, care needs (Shaw et al., 2017). This infrastructure within which our consumption actions take place further hinders the development of moral qualities that the personalization of responsibility otherwise has the potential to stimulate, according to Shaw et al. In other words, consumers may feel a moral obligation to act in accordance with care values, but the step from aspiration to action is inhibited by a market infrastructure that fails to support their desired care choices. Shaw et al. (2017: 424) choose to describe this as a consumers’ benevolence (i.e., “desire to do good”) that may – if the infrastructure and/or culture does not impede – translate to beneficence (i.e., “the act of doing good in care for self and others”).

The tendency to make individual responsibility the solution to structural problems such as unsustainable overconsumption, has rightfully been criticized (Maniates, 2001; Soneryd and Uggla, 2015; Stoner, 2021). Shaw et al. (2017: 425) however see personalization of responsibility as an important element in their theory of care in consumption and describe how their informants use authorization (referring to science and expert knowledge) to legitimize both their personal responsibility (in solving the environmental crisis) and their care actions. In defining their own responsibility, the informants further identify the responsibility of others, and may distinguish themselves as caring consumers from others who do not care.

With reference to Tronto (2013), Shaw et al. (2017) state that within consumption, the caring with phase is a necessary condition for the other phases of care to be realized. Caring with implies solidarity with others. It is not, however, sufficient – “[w]ithout the qualities of hope, trust and respect, we find it is highly unlikely that consumers would care that unidentified and distant others have caring needs and, hence, feel some sort of a responsibility or obligation to address those needs” (Shaw et al., 2017: 429). These qualities are needed, Shaw et al. claim, in the lack of relationality marking almost all consumption transactions today. When the workers producing the food we eat and the stuff we buy are distant others that “the sovereign” consumers never see or interact with, it is essential that consumers can put their hope and trust in the effectiveness of conscious consumer decisions when it comes to reducing socioecological harm. This means, for example, to trust the effectiveness of the fair-trade system, or hoping that going vegan makes a difference for animal welfare. Hope, trust, and respect are thus needed for consumers to keep acting out of care. This highlights, according to Shaw et al., the potential circularity of the phases of care in consumption – that a consumer does not necessarily progress linearly from one phase to another but rather moves circularly through the phases as one action of care interlinks with, and potentially reinforces, another. The circularity and potential reinforcements of care actions with care awareness and care responsibilities, respectively, does suggest a potential for a positive spiraling effect if a consumer is also moving through a process of identity negotiation (Cherrier and Murray, 2007).

A few things can be said about the different stages in the context of consumption reduction in Sweden in 2023, as compared to the downshifters interviewed in Cherrier and Murray’s (2007) study from (country not specified, but likely Australia or the US). First, all the interviewees in the Swedish study have (at least) general knowledge about the socioecological consequences of consumption since many years, highlighting the growing attention to this topic over time between 2007 and 2023. In some cases, their more dedicated or specific knowledge is due to an “awakening” or a triggering event as described by Cherrier and Murray as the starting point of the sensitization phase; that is, an event that has caused them to reflect upon their life and question their consumption patterns and normative background. A few such “awakenings” mentioned are: reading a certain book, going to university and meeting new people, a period of exhaustion, and moving out of a big house one has lived in for decades and into a small apartment. One interviewee described an unpleasant moment of realization when her children began talking about their birthday wishes the day after Christmas – “I realized that I have taught them when growing up that the finest things you can get are gifts” (IP5, woman, 44 years old). In several cases, however, the “trigger” seems less connected to a particular event and is instead stretched out in time. For instance, the decision to reduce one’s consumption is taken as a result of growing knowledge about the negative climate impact of overconsumption, and a responding urge of “wanting to do something.” In some cases, the decision was prompted by financial incentives.

Second, in the social context where most of the interviewees find themselves, the ambition to lead a more sustainable lifestyle is not seen as very controversial. All but a few can be categorized as culturally belonging to a middle-class segment (ranging from lower to upper middle-class) and have higher education. Several of the interviewees emphasize that they have been encouraged by friends and family who think they are doing something good, and that they have perceived the reduction process so far as smoother than they had thought it would be. This suggests that the separation stage described by Cherrier and Murray (2007), is context-dependent and may be more subtle in certain contexts. For example, a woman describes what factors have facilitated her decision to reduce her consumption:

The high prices. And knowing about the negative climate impact. (…) the more focus we see in media, for example, and in the societal debate, the bigger the consciousness in reality so to say. That means it is not only a theoretical consciousness, but it somehow becomes easier to refrain. (…) For some time, one should travel abroad a lot, now there’s a point in proudly stating that ‘no, I don’t travel abroad anymore, no, I don’t fly’. That has probably become easier, more and more people are travelling by train and so on (IP11, woman, 50 years old).

This quote, typical for several interviewees, indicates that rising prices and living costs not only motivate the individual to consume less, but may also increase social acceptance for consumption reduction. Further, it illustrates how in her social sphere it is not considered odd to stop flying; rather, it is something one can say with pride.

The perceived “absence” of a separation stage could however also be an indication that some of the informants in our study have simply not entered that phase yet, and that doing so implies a deeper reflection on and questioning of their conventional behavior (both in consumption and other areas), and the social norms and beliefs that shape that behavior. For example, this can be said to be the case with several of the interviewees who have not yet included their travel habits in their reduction attempts (see below on flight travels and car use).

Nonetheless, there are cases of perceived separation. One example is a woman who perceived the social context of her first child’s kindergarten to be very distant from her own values:

(…) when my daughter was little, around 5-6 years, and started to have birthday parties, then we didn’t socialize… We socialized with others who had different values, and I remember that the birthday parties made me feel so bad. They just increased, raised the stakes all the time for how the parties could become more magnificent, with more presents. There were so many toys being bought. (…) And now, when we’re surrounded by completely different friends and acquaintances with totally different values, I feel I don’t have to deal with that (IP10, woman, 35 years old).

This context, that did not align with her values (wishing to refrain from overconsumption), was something that caused her stress, and when her child grew up she decided to move back to her hometown. She chose a school for her child that was in line with her values and when she later had two more children they too went to the same school, where both the children and their parents made good friends and found a community of like-minded. Another woman described how she had made the difficult decision to sell her horse, aiming to limit her expenses and reduce her consumption. That decision had a big impact on her social life:

It’s a big community. You have horse[s] together, it’s like a recreation center for grown-ups – you go there after work and hang out for hours, and people socialize and help each other out and so on. That context disappears completely when you don’t have a horse, and… It’s really expensive, but there’s also a very social dimension to it (IP3, woman, 33 years old).

For this woman, the financial incentive was a strong driver for her decision both to sell her horse and to reduce her consumption. This also opened her eyes not only to her own previous unsustainable shopping habits, but also to the shopping and spending habits of her friend group, including quite costly social gatherings which she sometimes had to refrain from.

The following stage described by Cherrier and Murray (2007), namely socialization, is characterized by how new social influences and normative backgrounds inspire and guide the informants to drastically change their consumption lifestyles. Cherrier and Murray (2007: 20) explain how a decisive factor in this shaping of new normative backgrounds was “to reach out, listen, and follow certain others, being a friend, a new lover, a leader in a group, or simply knowing a person who lived differently.” Here, a third distinction must be made regarding the time passed between Cherrier and Murray’s study and ours. Whereas Cherrier and Murray emphasize the great importance of physical proximity to the social influences inspiring lifestyle changes, there are strong reasons to believe that this is not essential to the same degree anymore. Social media has drastically changed our ways of interacting and communicating in the past decade, making it possible to find and connect with, and become influenced by, like-minded peers all around the world. At the same time however, Osikominu and Bocken (2020) have shown how partners and new peers can be very important as external enablers when people aim to adopt a voluntary simplicity lifestyle. Our material confirms that these close relations are the most important ones, but also highlights the value of newfound communities such as with neighbors, other parents, or fellow dog-owners. In terms of normalizing new ways of living by showing that they are possible – one central element of the socialization phase – social media can however be claimed to have altered the framing of socialization. Cherrier and Murray (2007: 20) state that what their informants gained by reaching out to others was “access to a social sphere that was open to coaxing and coaching a new identity”. Such access – to find a social sphere of others with similar values and interests – has been facilitated by social media. Several interviewees mention that influencers have inspired them to buy second hand and that “sustainability profiles” (for example Greta Thunberg, politicians, and celebrities with a sustainability and/or gardening profile) have helped them question business-as-usual consumerism and normalize more sustainable consumption habits. Opposing this view, however, one interviewee commented that she experiences posts from “green influencers” as shaming and guilt-tripping people, for example about buying fast fashion, and that she does not believe in those types of methods. When social media was brought up in the interviews, it was never mentioned as the most important inspiration to reduce consumption. More common was to mention it in quite vague terms, like referring to certain profiles or Facebook groups dedicated to sustainable consumption practices as inspiring. Overall, it seems that social media can potentially – for some people – play an important role in normalizing certain sustainable behaviors.

Aside from social media, it is often the close relations that can work as “external enablers” (Osikominu and Bocken, 2020). Such is for example the case with a 32-year-old man who explained his journey from when he met his partner (now wife) as a process of finding new ways to reduce their consumption and become more self-sufficient together. And a man who stopped eating meat when his teenage daughters were upset about the meat industry and became vegetarians. Some interviewees describe how their consumption habits have changed when getting to know new friends (for example in university) for whom conscious consumption choices were normalized. One interviewee also reflects on the great diversity of her social relations as one aspect that facilitates her lifestyle changes:

If you live in a bubble with only one kind of people, or in a social context where there’s a lot of status stuff, or a lot… status and consumption are often connected, and high-income earners and upper class, and fancy… I think that’s more difficult, then there’s a completely different social pressure. (…) I have a circle of acquaintances from a common broad middle-class (…), some are single and others are interested in sports and some are politically active, some live in rural areas and some in the big city and some… well, it’s very different. I think that facilitates whatever kind of lifestyle change one aims for (IP11, woman, 50 years old).

Cherrier and Murray (2007) show that other people are of crucial importance in the shaping of new normative backgrounds and when trying to envision other ways of life. However, they also highlight the impermanence of these changes, considering the continuous difficulties involved in completely disposing oneself of old consumption routines and associations, and in navigating the social life and the consumerist culture. These difficulties are in focus in the fourth and final stage of the processual theory of identity, namely striving.

The striving stage is where one’s new consumer identity is to be tested in a long-term perspective; where one is to live in a new reality with a newly shaped normative background and practice the knowledge and inspiration gained from the previous stages. The striving stage, according to Cherrier and Murray (2007: 22), is highly reflexive, and “incorporates both considering others and answering fundamental existential questions about the self.” Cherrier and Murray emphasize that this is an ongoing struggle to handle not only the tensions produced “between maintaining, resisting, and defending competing identities” (p.23), but also the constant negotiations of objects to buy and reflections of needs versus wants. The ongoing struggle and constant compromises and renegotiations are very apparent in our material. Some days the new consumer identity can feel easy to shoulder, other days it feels like one takes several steps back in the reduction journey – also when one has been striving for years.

To be sure, all interviewees are to some extent and in some sense “striving” and engage in reflexive deliberations about matters that Cherrier and Murray discuss. However, consistent with Cherrier and Murray’s theory, the elements of struggling and negotiation are mentioned more frequently by those who have come further in their reduction processes. Often, these interviewees have “settled” at a lower consumption level and are used to organizing their everyday activities in accordance with these low-consumption ambitions. Nevertheless, some express frustration and struggling with the few areas where they have not managed to reduce. Such seems to be the case with the 35-year-old woman (IP10) who talked about eventually wanting to grow her own tea to avoid the negative ecological impact of drinking coffee, or the 34-year-old woman (IP19) feeling bad about buying bananas for her kids because it is not in line with her ambitions to only buy locally produced fruits and vegetables in season. Further, the occurrence of a new purchase that needs to be made may still initiate a reflexive process, even when one has become more grounded in their altered consumer identity. One interviewee dedicated to hunting explained for example the many advanced accessories one can be tempted to purchase even though they are not necessary: “there is an endless number of “good-to-have”-things for hunting, it really never ends” (IP14, man, 32 years old). Resisting the temptation to “upgrade” one’s equipment thus becomes a matter of perseverance. The struggling among these more dedicated reducers is also recurrent in expressed frustration with business-as-usual, reflecting on how one’s choices could be made easier in a society that prioritized differently (for example reduced worktime).

The “striving element” of reflecting on highly existential questions is also very apparent among the interviewees. These questions are also relatively frequently present among some of those who have only recently began reducing, indicating that they are striving in some areas even though they have not yet passed through all the other stages. One such example is this young man, who very recently had initiated a “low-buy year”:

… one has heard that getting a child is the worst thing you can do for the environment, and I find that very sad. I mean, it’s probably true, it probably is bad for the environment because then there’s one more person consuming. But on the other hand, one wants something to hand over, right? I hardly see any value if I’m like the last person alive, or if we who live now are the last to be alive on the planet. (…) If I do renounce having children, I think it will be for other reasons. But it’s definitely something that I have thought about as a quite difficult issue (IP2, man, 25 years old).

The question of potential future children was also brought up in other interviews, as was the question of the future of already existing children. Other highly existential questions regarded for example what one should fill one’s life with, reevaluation of what it is that really matters after a burnout, and – a very frequent reflection – what one really needs to feel content. Some reducers, it seems, no matter where in the process they find themselves, tend to dive right into the existential questions. Others might feel content just reducing their consumption and not dig too much into deep thoughts. This suggests that the nature and presence of the striving element may differ significantly between individuals, and not only in relation to the amount of time the person has tried to reduce.

Cherrier and Murray (2007) highlight the importance of agency in the stage of striving. Not only does it incorporate asking and answering highly existential questions about oneself and one’s life, it also “fundamentally moves the self from being passive with others to being active with others” (Cherrier and Murray, 2007: 22–23). Several of the informants who can be categorized as being in the striving stage also express the importance of finding others with whom they can act out their new consumer identities, and some also aim to find ways to influence other people and the wider community/society. Examples of this range from finding others in the neighborhood who are interested in urban gardening, starting Fridays for Future manifestations in one’s hometown, joining meetings with an activist network, and moving to the countryside and trying to engage with the neighbors.

In summary, our analysis suggests that we can both confirm and partly problematize the theoretical model presented by Cherrier & Murray. They have identified important steps in the gradual bolstering of an alternative consumer identity; however, the stages are variously distinct among the participants in our study. It is important to emphasize also that the overall societal context has changed since the initial formulation of the theory (changing norms, social media, heterogenous social landscape), which, for example, impact on the processes of separation and socialization to new norms. Still, consumption reducers are clearly striving with regards to practical, personal, social and existential matters. A possibility is to see the stages not necessarily as sequential but (to some extent) parallel and interactive in the gradual bolstering of a new identity. Next step in our analysis will be to see what further insights can be gained by combining this model of identity negotiation with the perspective of care.

The interviewees’ care for the environment and socioecological consequences of consumption is visible in many ways in the interviews, but perhaps most prominently when they are asked to motivate why they want to reduce their consumption. Some just state matter-of-factly that it is for environmental and/or social reasons, whereas others expand a bit more:

Partly there is the issue of the climate threat and changes – I realize that we consume too much all of us, at least in Sweden. I feel a responsibility to cut down on my quota, even though it doesn’t change everything (IP4, woman, 74 years old).

Lately, perhaps the past three years, we have also started to think about buying secondhand. So that there’s no need to extract new material from nature but instead use what’s already existing. (…) [A] nd then I think about how it’s produced. Social aspects of it. If you buy [something] too cheap, you can think about how it is for the workers and how it is for the environment, and so on (IP9, man, 43 years old).

Other interviewees focus more on the economic reasons behind the reduction, which can be interpreted as caring for oneself and, as in this case, one’s children:

We [IP + daughter] moved to a house in connection with the price increase for food and electricity. (…) Now we must keep within our income, we must make ends meet. Most people want to be on plus, but it’s possible to live within one’s income if you only keep track of what you buy. So that’s how we started to live frugally, and to try and warm the house only with an air heat pump and fire. And take short showers (IP8, man, 50 years old).

Such motivations highlight the interconnectivity between care for oneself and others (cf. Shaw et al., 2017). There are also expressions of self-care, or self-interest, in the sense that informants may want to reduce consumption to safeguard their own well-being:

(…) I have somehow come to realize that I have tried to use shopping and consuming as some sort of comfort, and that doesn’t work … (…) I need a more sustainable relation to consumption overall. Because you can’t, like, shop your way to wellbeing. But since I have overconsumed pretty much, it of course has economic reasons too – financially, I don’t have the opportunity to keep up such a lifestyle (IP22, woman, 44 years old).

These motivations, sprung out of care, create propensity for sensitization. Considering that all interviewees in one way or another highlight caring about the consequences of overconsumption and the climate crisis when explaining their decision to reduce their consumption, caring may even be seen as a trigger, or as a necessary condition for sensitization to occur (cf. Cherrier and Murray, 2007).

Several of the informants feel a personal responsibility to “do something,” which can be seen as part of the sensitization process (Cherrier and Murray, 2007). This responsibility and desire to care – perhaps not always to do good, but at least to do less harm – is sometimes also experienced as guilt for not doing more. In line with Shaw et al.’s personalization and authorization elements, these reducers have interpreted scientific warnings about the need to change our unsustainable lifestyles into an agenda where they assume individual responsibility, aiming for a reduced and more careful consumption. Often, this comes with reflections on other’s consumption and, seemingly, lack of care:

But I’m still like really surprised when friends simply order ten garments of which three don’t fit, and then they don’t even have the energy to send them back, so they just lay somewhere and like… yeah, like that type of mass consumption (IP23, woman, 30 years old).

Identifying oneself as someone who cares, and distancing oneself from others who, in their view, do not care, can be something that spurs the separation process discussed earlier. In this context, it is worth mentioning Kennedy’s (2022) work on different ways of caring for the environment, where she highlights the risk of not acknowledging other ways of caring than one’s own, thus potentially spurring polarization and separation. At the same time, however, this positioning as someone who cares can also be seen as part of the socialization process, opening up for socializing with others who share a similar understanding of care.

That the interviewees assume individual responsibility does not, however, mean that they downplay the importance of political measures. Rather, the need for structural changes that can support and facilitate a caring and responsible consumption (for example investing in railway instead of aviation and making it easier to bike and use public transport than using the car) is repeatedly mentioned in the interviews.

One perhaps surprising result from the interviews with the individuals who had most recently started their attempts at consumption reduction, was that the great majority of them did not find the process too difficult. On the contrary, several emphasized the perceived easiness of actively shifting to buy only secondhand, or to reduce consumption that they had identified as unnecessary.

When asked for more details about their changed consumption behavior, however, the interviewees did identify some aspects that illustrate the difficulties of managing different and conflicting care needs. This is perhaps most prominent in two areas: gift-giving, especially involving children, and flight travels. Regarding gifts, almost all interviewees have decided to exclude presents and gifts to others from their reduction attempts. This is motivated both by framing gifts as an important expression of care and affection, and by the wish to avoid being seen as weird or non-generous:

I have my grandchildren, and that’s a certain amount of consumption with gifts and so on. I count that as unavoidable, gifts and Christmas presents. (…) It doesn’t need to be expensive, but still – that one thinks about the person (IP4, woman, 74 years old).

Because I want to give, it’s somewhat expected at the social event, that one arrives with a gift. (…) And I don’t really know how to do with that, I mean also in the future, because I do want to buy something. And I also understand that if I give money… I mean, that can be appreciated, but then they will buy something [for themselves]. So I have tried, at least for the time being, to forego, that alright, that is acceptable for the time being. (…) That’s the difficult part, gifts (IP2, man, 25 years old).

Universally, gift-giving is an area where one’s care-based motivations for reducing consumption conflict with the need to express care for loved ones. How one chooses to deal with this conflict varies. Several interviewees have found ways to express care through gift-giving that are more in line with their new consumer identity, for example to give away experiences (e.g., tickets to a concert) or giving self-made gifts. A reflection by a woman who quite recently started her reduction attempts illustrates nicely the renegotiating of care in gift-giving:

(…) it’s so easy to feel that if one is to give a gift it must be something pretty, and then it should be something new, and so on. But I have tried to think through that, and recently I gave a pumpkin plant that I had grown myself to a friend, and another friend whose daughter graduated… I found a book in my own bookshelf which I liked a lot that I gave to her, and then it felt fun too, to give something that’s more personal, even though it wasn’t anything I had bought (IP20, woman, 40 years old).

Another woman explains how she has simply insisted that others cannot give her children any new toys or gifts, to the point where “no one dares to buy gifts for my kids anymore, they know how strict I am” (IP19, woman, 34 years). This somewhat confrontative approach suggests that she has not allowed any fear of potential separation to stand in the way for her reduction ambitions. This approach is rare, not the least when it comes to flight travels, which was a difficult topic for several of the interviewees. A few stated that they had completely given up flying for climate reasons, others indicated that they had radically reduced their flight travels, and some had not yet included travel habits in their consumption reduction. Among those interviewees who had not yet stopped flying, everyone mentioned that they were aware of the high climate impact of their travels. Very often, the decision to continue flying – despite this high impact – was motivated by referring to family ties or friendship bonds, suggesting that care considerations and aiming to avoid separation from these relationships are at play in the negotiations (cf. Cherrier and Murray, 2007). A few interviewees had friends or family living abroad, but vacation travels were also motivated by caring for the relations with whom one would travel. One woman explained how her children had not been on a plane since she and her husband stopped flying several years ago (since they were the ones paying for the family vacations), but, she said:

(…) this summer we made an exception. Everyone loves musicals, and all of us wanted to go to London. My husband and I drove in a biogas car, which took forever. Our daughter gets sick in the car so that’s not possible. Our son was working and only had a small window open [possible for travelling]. So, then we said that they could fly.

Interviewer: How did that feel?

Interviewee: I felt very torn. It felt like something really important, the last trip we’ll do together the four of us, and to share something together that we all love. So then one tries to think that it’s worth it (IP24, woman, 55 years old).

A similar case was a woman who said that she and her partner had not wanted to fly for the last years, but now they had decided that half the family would go on a summer holiday together with other relatives:

[M]y 17-year-old daughter is a bit difficult to… she’s part of the reason why we will go on this trip this summer. We felt that she thinks that we destroy her life if she can’t go on any trip (IP10, woman, 35 years old).

Another woman, recently having started her consumption reduction process, debated with herself what to do about reducing travels:

(…) I’m not sure how it will be possible to reduce. One trip this spring was decided together with others, a group who will travel to Vienna, Austria. That’s decided since way back, so that will happen. Then I will also travel to Berlin and visit my daughter who lives there. And then I will travel within the country and visit children and grandchildren and so on. But it’s also a tradition to travel to Greece each autumn [to meet up with a friend who lives in the Netherlands], so we’ll see if that’s possible to refrain from (IP4, woman, 74 years old).

As the last quote suggests, it is sometimes difficult to draw the line between decisions made out of care for others and those where care for others is used to justify one’s decision to fly. With reference to Shaw et al. (2017) and Cherrier and Murray (2007), it is also possible that such decisions are made from self-care and/or wishing to avoid the risk of separation. This serves to highlight that flight travels stand out as a special case of consumption. The interviewees who continue to fly despite being aware of the high impact of flight travels, also tend to relativize and/or justify those emissions compared to the emissions from other areas of consumption, suggesting that their reduction attempts have not (yet) spilled over to this “big matter” of sustainable consumption (cf. Bilharz and Schmitt, 2011).

Several of the informants express caring for the things that they already have and that they do choose to buy, suggesting a much more reflective approach to material things and belongings than the conventional, “throw-away” approach. Possessing fewer things means that you have the possibility to spend more time on each item you have; thus more possibilities to take care of each item [which for example Schor and Thompson, 2014 discuss in terms of “true materialism”]. The theme is also expressed both in concern for buying things of good quality that will last long, and in repairing clothes and products that break or tear, in line with Karimzadeh and Boström’s (2023) perception of care in the different consumption stages. One informant talks about his knitted sweater, a home-made gift from his sister, that he plans to give a very long life by repairing and caring for. He emphasizes the importance of respecting the time and effort needed to produce that which we consume:

[O]ne important thing that is significant to me is that we… that one in some way has respect for that stuff and things and food are very expensive to produce, both in labour and in time and money and I think it’s unnecessary to waste things (IP14, man, 32 years old).

In this case the informant sees caring for things and caring with those who make them as tightly interwoven, leading him to be both very sparse and conscious with the purchases he does, and to care about his possessions in the sense of prolonging their lifespan. This not only highlights the role that “relations of dependency” between consumers, producers and other stakeholders play when it comes to care in consumption (Shaw et al., 2017: 428). In the context of identity negotiation (Cherrier and Murray, 2007), the adoption of more profound ways of caring for one’s things can also be seen both as a separation from the throw-away mentality and as socialization with new ways of relating to material things and those who produce them.

Regardless of the level of their ambitions or how long they had been dedicated to reducing their consumption, it was common among the interviewees to express frustration with the dominant consumption infrastructure and/or the culture of consumerism. Our material clearly shows that consumers tend to give in to convenience when facing structural obstacles. This is in line with Shaw et al. (2017), who show how many intentions to act out of care are inhibited by infrastructure and the logic of the market because these prioritize profits over care and/or socioecological concerns. Among our interviewees, this was for example apparent in the motivations for keeping one’s car despite the knowledge that it was a driver of one’s emissions, as highlighted by this man:

[W] ith the car, it takes me 40 minutes [to get to work], and with train and bus it takes two hours and ten minutes, so it’s a big difference. It’s not unpleasant to travel with train or bus, but the time disappears. It’s time that I otherwise can spend with people who I want to be with, and it feels difficult to give that time away to be more environmentally conscious (IP6, man, 56 years old).

One interviewee living far north in Sweden also mentioned the difficulties of travelling, not only abroad but also within the country, if one did not want to fly. This interviewee had not stopped flying and argued that it was “something for the politicians to solve” (IP4, woman, 74 years old).

Another area of frustration related to infrastructure was the question of wanting to reduce one’s working hours but not being able to afford living costs (this was especially the case for interviewees with children) and/or not having the possibility because of the “full-time norm.”

it’s more [the fact] that one has to work instead of just growing the garden and doing things on one’s own. (…) If I could just decide for myself, I would probably have wanted to reduce my working time more and have less, I mean get less money, less income to do more things myself. But it feels like I cannot do that for the sake of my daughter (IP10, woman, 35 years old).

These examples all highlight the element of striving, as in struggling to find ways to consume less within a system that is constructed to promote the opposite. Something that several informants mentioned as facilitating their reduction ambitions was well-functioning secondhand platforms that allowed them to buy things with a smaller impact once they had decided that they needed to make a certain purchase. Platforms that allow for easy secondhand purchases, but also for sharing and borrowing, can thus be claimed to work to facilitate rather than inhibit care actions, or – in the words of Shaw et al. (2017) – help the reducers go from benevolence to beneficence.

In the material, we found a typical kind of negotiation between care for oneself and one’s closest family vs. care for others/future generations/non-humans, and for ecosystems/nature. It seems that among the interviewees who are most dedicated to their reduction (also long-term), several are dealing with the element of competing care needs by incorporating the need to care for oneself and the closest family into one’s wish to care with nature/climate/the environment/distant others. This means for example aligning one’s understanding of self-care to one that is more in line with an ecologically sustainable lifestyle, such as working less, biking more, and seeing the benefits with it: “I walk to work everyday even though I could take the car, and I feel that I get exercise, it costs less (…) and I feel that it somehow becomes a lifestyle for me to do so” (IP15, woman, 54 years old). It could also be about reducing work hours to be able to spend more time with one’s children or starting to grow vegetables to eat more organic (and also experiencing well-being). In contrast to many of the interviewees in earlier stages of reduction, this more holistic view of care is repeatedly expressed in the interviews with the most dedicated reducers.

The interviewees who have made these individual choices of aligning one’s consumption practices with a caring with-perspective and thus are making room for more care in their everyday life, often reflect on what would happen if such choices were to be implemented on a larger scale in society. One interviewee, working with acting-out school children, mentions how he notices how tired they are, and how reducing the time in school (similar to reducing work time) might be helpful in several aspects:

Actually, I think that the whole society would feel very good from working like that, and the children at school. The world would be different, really, and we would be able to cope more. (…) really, a lot of our problem is this model we've chosen, that we're supposed to be so tired. Who has the energy, then, to think about saving electricity, or to think about the environment? (IP8, man, 50 years old).

Another theme suggesting a more holistic view of care regards caring for the local ecosystems and the nature in the place where one lives; for example through growing own gardens and spending much time in nature. To some extent, caring about and supporting local businesses in the context of the pandemic – a concern expressed by a few interviewees – may also be categorized as caring for the local.

Many times, this renegotiation of care or, rather, inclusion of care for one’s close relations and oneself into a larger caring with-approach, is related to reflections on the nature of contentment. Returning to the woman above who has incorporated self-care into the decision to walk to work, she also describes how she sees happiness as being about doing good, “for others or for the greater good,” and how that in turn makes oneself feel good:

(…) I mean, one thing leads to another. If you do this little thing, you want to do that thing, and then you want to continue with that thing and then continue like that, so that one thing actually leads to the other (IP 15, woman, 54 years old).

That one thing leads to another is closely linked to Shaw et al.’s (2017) view of care in consumption as circular and dynamic, as one action of care may interlink with, and potentially reinforce, another. The above quote suggests that this circular motion may also be spiraling outwards, in the sense of expanding care to others and, as described earlier, actively engaging in for example climate activism. In this way, they may also form part of other consumers’ sensitization in the future. Here we can see the potential of a more holistic ‘caring consumer’: one who embodies care in consumption practices by (1) incorporating care for those closest to one’s heart with an encompassing care for human and non-human others, and (2) actively expanding care to others, thus spurring more processes of consumer identity negotiation. Whereas smaller changes in consumption behaviour aiming at more sustainable consumption have been argued not to spill over to other areas of greater importance to reduce one’s environmental footprint (Bilharz and Schmitt, 2011), we suggest that the development of a holistic care approach in this way may result in positive, and more long-term, spillover effects – both in regard to one’s own consumption and in motivating others.

The process toward a more dedicated and holistic view of care – with most potential for facilitating sufficiency-oriented lifestyle change – can be seen through the perspective of the consumer identity negotiation process; a view and commitment to care which is bolstered through processes of sensitization, separation, socialization, and striving. The development of care can also in turn spur renegotiations of the consumer identity.

Drawing on Cherrier and Murray’s processual theory of consumer identity, we suggest that the process of becoming a “caring consumer” through reducing consumption is a gradual one. It is further, undoubtedly, one of striving – not only in terms of the efforts involved when aiming to combine care for oneself and those in one’s close affinity with care for human and non-human others that bear the socioecological consequences of unsustainable mass consumption, but also when it comes to practicing care in consumption within a consumerist infrastructure emphasizing profit over care (Shaw et al., 2017). Table 1 summarizes the ways in which care is expressed in our empirical material on “reducers,” with references to Cherrier and Murray (2007) and Shaw et al.’s (2017) respective theories.

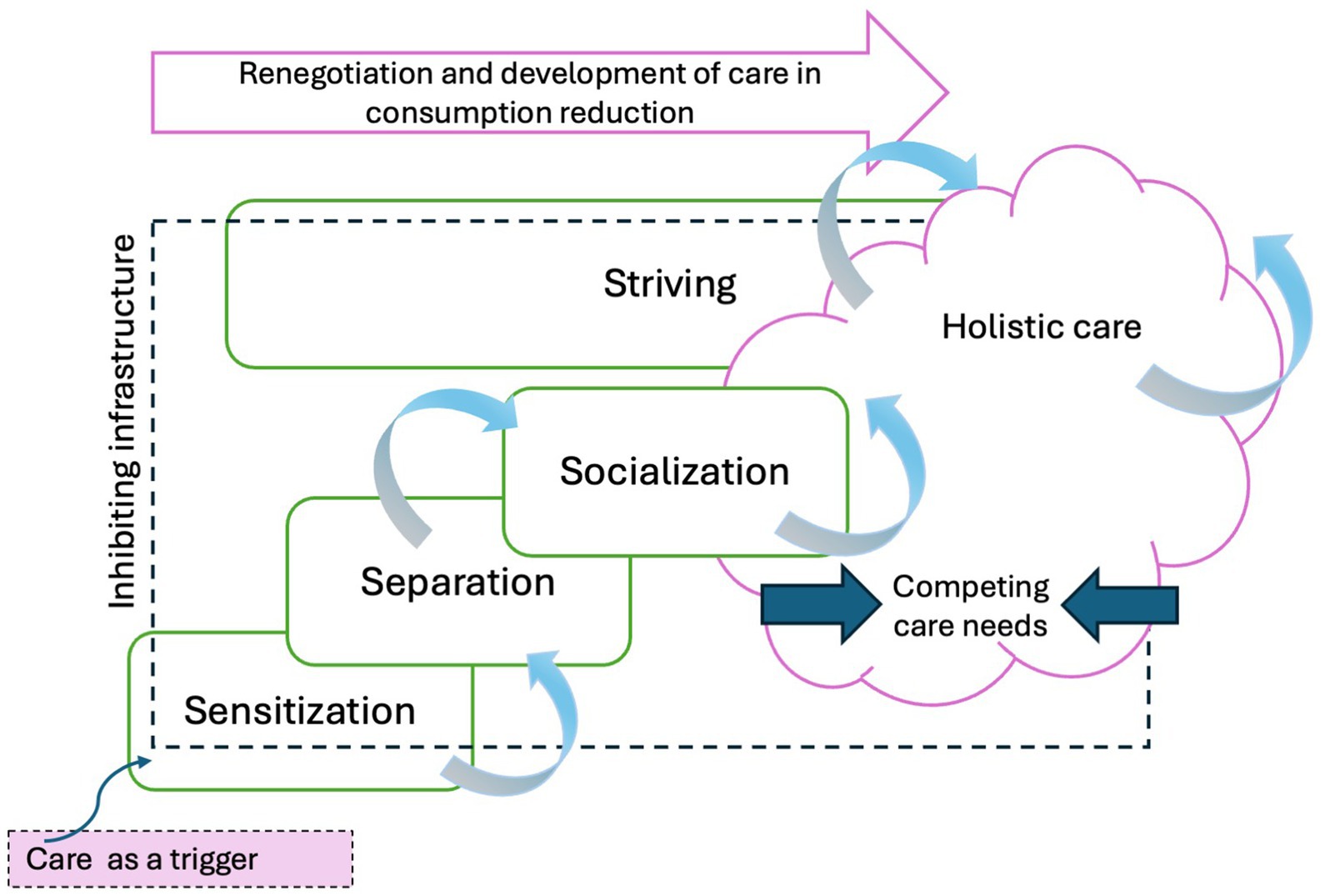

The ongoing struggle and constant compromises and renegotiations connected to consumption reduction are apparent in our material. To manage competing care needs seems to be a never-ending striving, at least if one continues the reduction journey and chooses not to stay at a reduction level that is perceived as personally and socially comfortable (i.e., without too many compromises). Adapted to a care perspective, this striving can be described as a stage of aiming, step-by-step, to consolidate the caring consumer identity and learning to navigate this new identity within a consumption infrastructure based on opposing priorities. The individuals who are strongly motivated to care with may also renegotiate the ways in which they show and practice care for their loved ones, and make these more compatible with caring with nature, distant others and future generations. Sometimes, but not always, this implies more cumbersome consumption practices, which is why this can be a potential distinguisher between the most dedicated reducers and the others. If the caring with-factor is strong enough, it may take lead in the renegotiation of how one practices care in everyday life, but also, in some cases, spiral outwards to sensitize others about care in consumption. This development and renegotiation of care through the different stages of consumer identity negotiation is illustrated in Figure 1, which links the different stages (Cherrier and Murray, 2007) with the circular and dynamic role of care in consumption (Shaw et al., 2017) in the process of consumption reduction. The figure shows how care may be renegotiated through the stages, how actions of care reinforce new ones and how – potentially – a more holistic care perspective can be adopted, one that integrates conflicting care needs and causes care to spiral outwards.

Figure 1. Negotiations toward a more holistic caring consumer identity in the process of consumption reduction. Source: Authors, based on Cherrier and Murray (2007) and Shaw et al. (2017).

These findings have wider implications for the problem known as the value-action gap (or attitude-behaviour gap, knowledge-action gap) within the research field [see, e.g., Boström and Klintman (2019) and Gunderson (2023)], as well as for the debate about whether and how individual action and responsibility can spread and have a larger impact on collective transformation (for instance through dynamic interplay between top-down intervention/facilitation and bottom-up pressure for change). The concept of care, we argue, brings important understandings to these interrelated topics. We see in the material that structural and cultural circumstances – here framed as a consumption infrastructure and consumerist culture – create serious difficulties in translating “values” into impactful “action” (or, in the words of Shaw et al. (2017), in moving from “benevolence” to “beneficence”). A focus on care in consumption contributes to a richer understanding of this gap between values and action, as shown in the discussion about the challenges of competing care needs and ongoing struggles to maintain one’s reduction ambitions in an everyday context constantly encouraging more consumption. In combination with the processual theory of consumer identity, the focus on care in consumption can also contribute to new insights on how to address and eventually reduce this gap. For instance, we have observed the gradual development of a more dedicated and holistic view of care, emphasizing the process of striving and renegotiation of care, and further incorporating qualities such as “caring with” and higher sensitivity to extended relationality. Such a development seems to also include an outward spiraling of care, resulting in positive spillover effects. In addition to closing the gap between values and action, the more holistic approach to care seen in the material also provides a bridge between individual and collective action. That is, it can potentially stimulate the development of a social agency at both the individual and collective level – particularly in the stage of striving – which in turn is a necessary component for a more long-term, collective transformation.

As issues around care are gaining momentum in the sufficiency and sustainability debates, we think it is important to maintain sensitivity to the ambiguities. To close, we argue, based on our analysis, that the scholarship on sufficiency-oriented lifestyle changes have much to gain by recognizing the critical role of care in these change processes, and by paying attention to how care is both a source of serious difficulties and a key driver of transformative change.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ÅC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This article was written within the research project “(Un)sustainable lifestyles: social (im)possibilities to consume less,” funded by the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development, Formas (grant no. 2021-00972).

We are grateful for insightful comments from the environmental sociology group at the conference “Sociologdagarna” in Gothenburg, Sweden, 2024.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Akenji, L., Bengtsson, M., Toivio, V., Lettenmeier, M., Fawcett, T., Parag, Y., et al. (2021). 1.5-degree lifestyles: towards a fair consumption space for all. Berlin: Hot or Cool Institute.

Alfredsson, E., Bengtsson, M., Brown, H. S., Isenhour, C., Lorek, S., Stevis, D., et al. (2018). Why achieving the Paris Agreement requires reduced overall consumption and production. Sustainability: Science, Sustain.: Sci. Pract. Policy., 14, 1–5. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2018.1458815

Bilharz, M., and Schmitt, K. (2011). Going big with big matters. The key points approach to sustainable consumption. Gaia 20, 232–235. doi: 10.14512/gaia.20.4.5

Bohlin, A. (2019). “It will keep circulating”: loving and letting go of things in Swedish second-hand markets. Worldwide Waste 2, 1–11. doi: 10.5334/wwwj.17

Boström, M. (2021). Social relations and challenges to consuming less in a mass consumption society. Sociologisk Forskning 58, 383–406. doi: 10.37062/sf.58.22818

Boström, M., and Klintman, M. (2019). Can we rely on ‘climate-friendly’ consumption? J. Consum. Cult. 19, 359–378. doi: 10.1177/1469540517717782

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360

Callmer, Å. (2019). Making sense of sufficiency: Entries, practices and politics. Doctoral dissertation. Stockholm: KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Chamberlin, L., and Callmer, Å. (2021). Spark Joy and slow consumption: an empirical study of the impact of the KonMari method on acquisition and wellbeing. J. Sustain. Res. 3:e210007. doi: 10.20900/jsr20210007

Cherrier, H., and Murray, J. B. (2007). Reflexive dispossession and the self: constructing a processual theory of identity. Consum. Mark. Cult. 10, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/10253860601116452

Cherrier, H., Szuba, M., and Özçaǧlar-Toulouse, N. (2012). Barriers to downward carbon emission: exploring sustainable consumption in the face of the glass floor. J. Mark. Manag. 28, 397–419. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2012.658835

Evans, D. M. (2018). What is consumption, where has it been going, and does it still matter? Sociol. Rev. 67, 499–517. doi: 10.1177/0038026118764028

Godin, L., and Langlois, J. (2021). Care, gender, and change in the study of sustainable consumption: a critical review of the literature. Front. Sustain. 2:725753. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.725753

Gram-Hanssen, K. (2021). Conceptualising ethical consumption within theories of practice. J. Consum. Cult. 21, 432–449. doi: 10.1177/14695405211013956

Gunderson, R. (2023). Powerless, stupefied, and repressed actors cannot challenge climate change: real helplessness as a barrier between environmental concern and action. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 53, 271–295. doi: 10.1111/jtsb.12366

IPCC (2022). “Summary for policymakers,” in Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of working Group III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. eds. P. R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, and D. McCollum, et al. (Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press).

Isenhour, C. (2010). On conflicted Swedish consumers, the effort to stop shopping and neoliberal environmental governance. J. Consum. Behav. 9, 454–469. doi: 10.1002/cb.336

Jackson, T. (2005). Live better by consuming less? Is there a “double dividend” in sustainable consumption? J. Ind. Ecol. 9, 19–36. doi: 10.1162/1088198054084734

Jungell-Michelsson, J., and Heikkurinen, P. (2022). Sufficiency: a systematic literature review. Ecol. Econ. 195:107380. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107380

Karimzadeh, S., and Boström, M. (2023). Ethical consumption in three stages: a focus on sufficiency and care. Environmental. Sociology 10, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2023.2277971

Kennedy, E. H. (2022). Eco-types: five ways of caring about the environment. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lorek, S., Power, K., and Parker, N. (2023) in Economies that dare to care: Achieving social justice and preventing ecological breakdown by putting care at the heart of our societies. eds. S. Violette and D. Silva (Berlin: Hot or Cool Institute).

Maniates, M. F. (2001). Individualization: plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Glob. Environ. Politics 1, 31–52. doi: 10.1162/152638001316881395

Merz, J. J., Barnard, P., Rees, W. E., Smith, D., Maroni, M., Rhodes, C. J., et al. (2023). World scientists’ warning: the behavioural crisis driving ecological overshoot. Sci. Prog. 106. doi: 10.1177/00368504231201372

O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F., and Steinberger, J. K. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 1, 88–95. doi: 10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4

Osikominu, J., and Bocken, N. (2020). A voluntary simplicity lifestyle: values, adoption, practices and effects. Sustainability 12:1903. doi: 10.3390/su12051903

Schneidewind, U., and Zahrnt, A. (2014). The politics of sufficiency: Making it easier to live the good life. München: Oekom.

Schor, J. B., and Thompson, C. J. (2014). Sustainable lifestyles and the quest for plenitude: Case studies of the new economy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Shaw, D., McMaster, R., Longo, C., and Özçaglar-Toulouse, N. (2017). Ethical qualities in consumption: towards a theory of care. Mark. Theory 17, 415–433. doi: 10.1177/1470593117699662

Soneryd, L., and Uggla, Y. (2015). Green governmentality and responsibilization: new forms of governance and responses to “consumer responsibility”. Environ. Politics 24, 913–931. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2015.1055885

Stoner, A. M. (2021). Things are getting worse on our way to catastrophe: neoliberal environmentalism, repressive Desublimation, and the autonomous Ecoconsumer. Crit. Sociol. 47, 491–506. doi: 10.1177/0896920520958099

Tronto, J. C. (2013). Caring democracy: Markets, equality, and justice. New York: New York University Press.

Wahlen, S., and Stroude, A. (2023). Sustainable consumption, resonance, and care. Front. Sustain. 4:1013810. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1013810

Keywords: care, sufficiency, sustainable lifestyles, downshifting, overconsumption

Citation: Callmer Å and Boström M (2024) Caring and striving: toward a new consumer identity in the process of consumption reduction. Front. Sustain. 5:1416567. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2024.1416567

Received: 12 April 2024; Accepted: 13 June 2024;

Published: 26 June 2024.

Edited by:

Maria Alzira Pimenta Dinis, Fernando Pessoa University, PortugalReviewed by:

Sylvia Lorek, Sustainable Europe Research Institute, GermanyCopyright © 2024 Callmer and Boström. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Åsa Callmer, YXNhLmNhbGxtZXJAb3J1LnNl

†ORCID: Åsa Callmer, orcid.org/0000-0002-3215-6793

Magnus Boström, orcid.org/0000-0002-7215-2623

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.